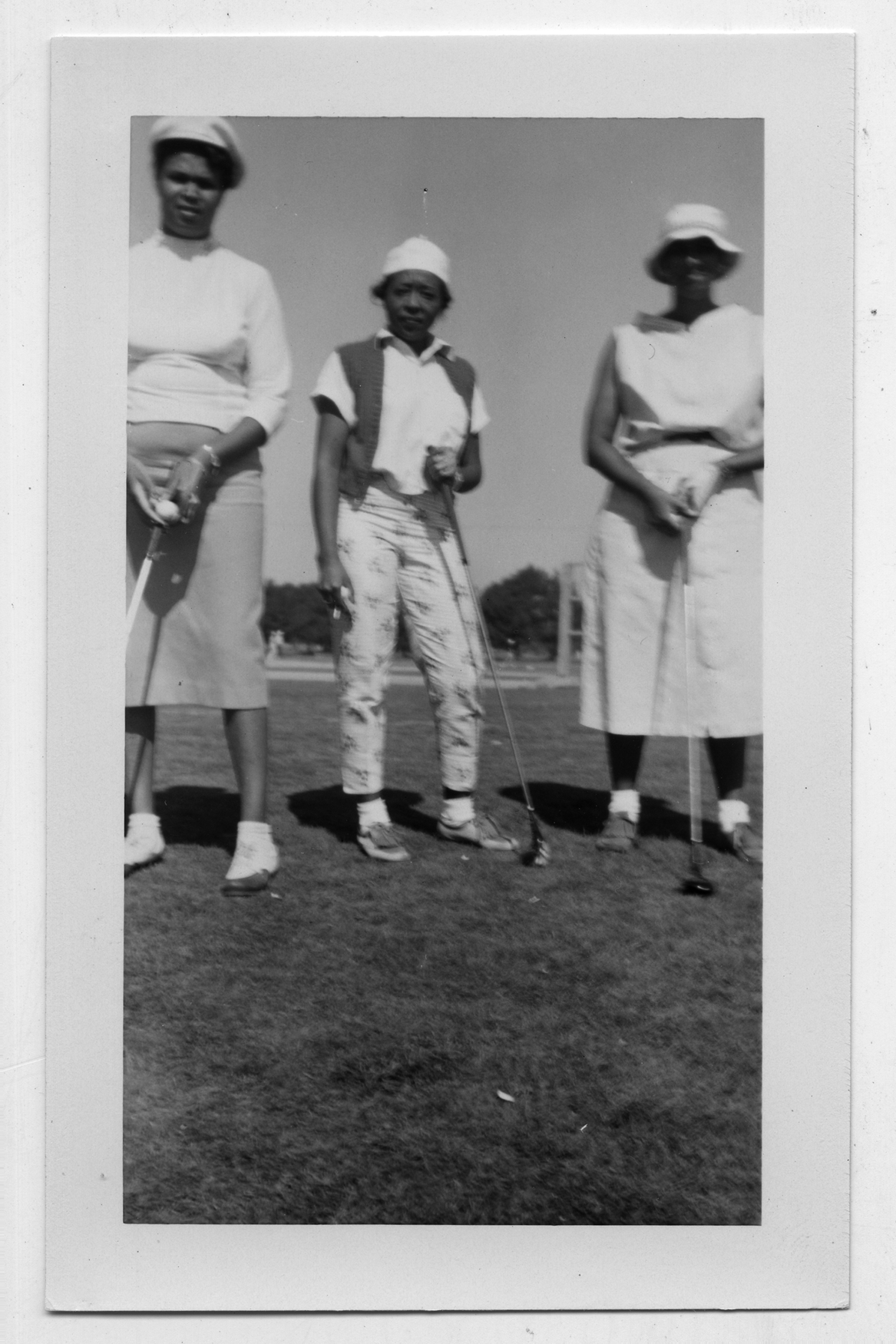

Three Black women pose for a photograph mid play, a golf course stretching out behind them. With slight smiles, they squint in the sun at the camera, taking a break from the meditative intensity of the game. Two women wear skirts, or maybe one is sporting a culotte, bobby socks, and at least one of them seems to be wearing a regulation cleated shoe. A breeze blows fabric against legs. Each holds her club atop a golf ball, their bodies and the flagstick casting shadows on the putting green (see Figure 1). They are members of the Par-Links Black Women's Golf Club, formed in California's East Bay in 1958. Advertising for new members in the Oakland Black newspaper, the California Voice, the club held its first tournament the following year at Tilden Park Golf Course in Berkeley. “… challenge or be challenged,” the group cheered: “Your place on the ladder depends on your win.”Footnote 1

Figure 1. Three Par-Links players on putting green, 1960s, Par-Links Golf Club Scrapbook (MS 214), African American Museum and Library at Oakland, Oakland Public Library, Oakland, CA.

(Esther) Mae Bell joined the “up and coming” club in the spring of 1959, the same year Par-Links, which was so new that they were not yet a member of the Western States Golf Association, co-hosted WSGA's post tournament festivities (see Figure 2).Footnote 2 Bell, named third on the permanent eighteen-hole tournament ladder, must have been a pretty good player even before she joined. Entrusted with keeping some of the group's founding materials, Bell eventually donated them to the Oakland African American Museum and Library. The inclination of Par-Links’ members to document their golf club, with photographs, newspaper clippings, and organizational documents, and Bell's decision to donate them in 2005 at the age of eighty-one, stands as an assertion of the club's significance (see Figure 3). It also serves, in visual studies scholar Tina Campt's words, as a “practice of [both visual and spatial] refusal.” The Black women of Par-Links ensured their club's collection an archival life, which “refuses” and “negates” anti-Black stereotypes and caricatures of Black people in the early sport of golf. Its preservation also makes claims to the right of Black women's individual and communal play and leisure, and to the personal and political significance of Black recreation more broadly.Footnote 3

Figure 2. Western States Golf Association Championships Program, 1959, Par-Links Golf Club Scrapbook (MS 214), African American Museum and Library at Oakland, Oakland Public Library, Oakland, CA.

Figure 3. Margaret Nell Wilson and Doralee Petty standing with rolling stand bag, 1960s, Par-Links Golf Club Scrapbook (MS 214), African American Museum and Library at Oakland, Oakland Public Library, Oakland, CA.

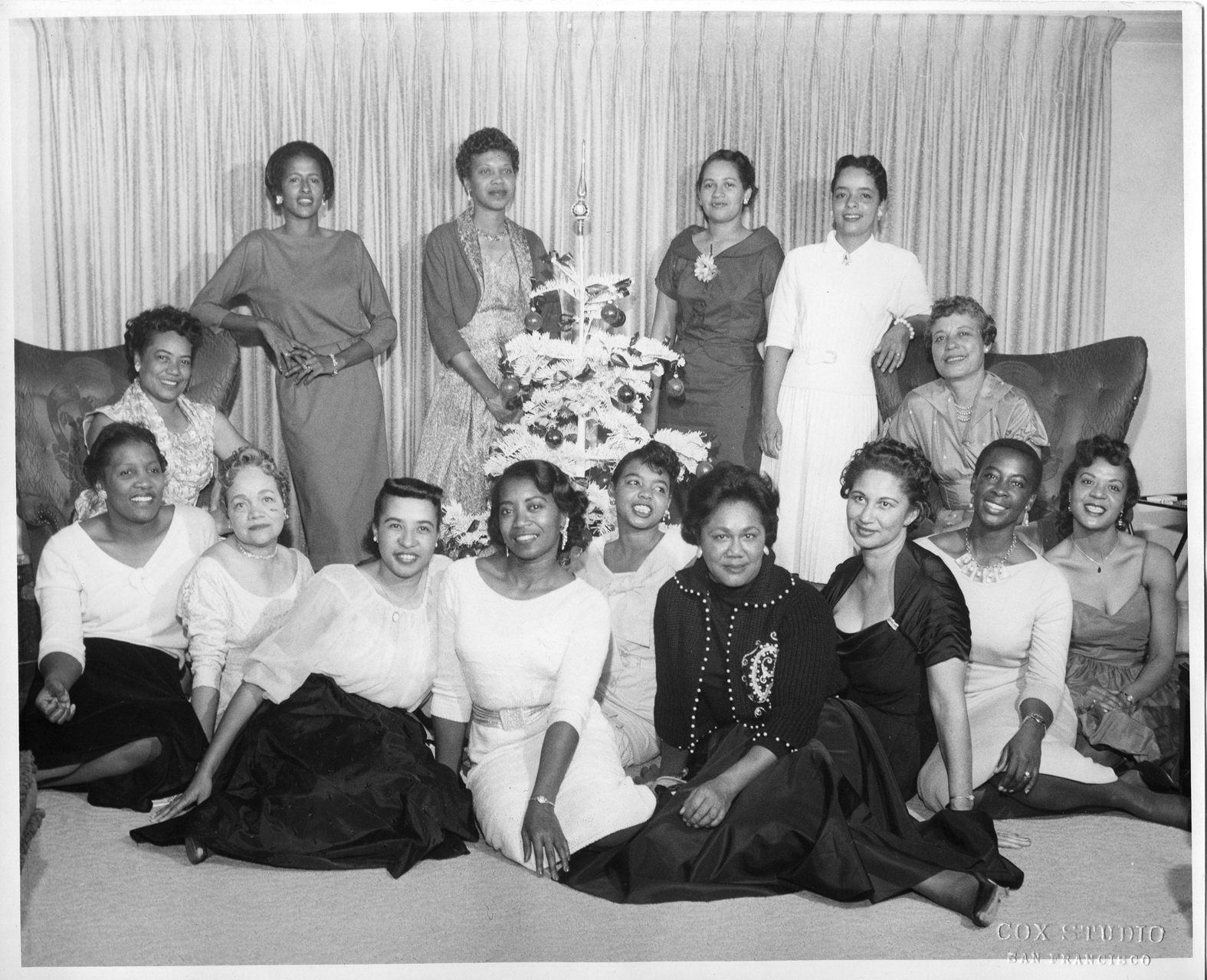

Par-Links’ formation in the late 1950s was part of a larger and longer movement of Black people fighting for access to not only housing, education, and jobs, but to public parks, swimming pools, and other municipal recreational facilities (see Figs 5 & 6).Footnote 4 By the time the Par-Links founders donned fine cocktail attire and sat for their portrait during Christmas 1959 in Figure 4, enjoying each other and celebrating the clubs’ official formation, Black activists in California had already devoted decades of serious and organized attention to mobilizing against Jim Crow, staking claims in all forms of and spaces for Black women's recreation.Footnote 5 Par-Links belongs to this long history of Black interest in golf nationally, and an even longer insistence by Black women that they were entitled to rest and relaxation, and unashamed of their pursuit of recreation and play.

Figure 4. Par-Links Golf Club (left-to-right, seated): Lavanda Scott, Velma Davis, Edna Dotson, Nadeen Willis, Cleo Dell Johnson, Ramona Mabel, Margaret Nell Wilson, Arjere Johnson, Ruth Beckford Chatmon, Jane McIntosh, Eola Paige, (left-to-right, standing) Doralee Petty, May Frances Reid, Juanita Wilson, and Doris Bruce. Par-Links Golf Club Scrapbook (MS 214) African American Museum and Library at Oakland, Oakland Public Library, Oakland, CA.

Figure 5. “Caucasians Organize Protective League,” Los Angeles Times, June 9, 1922, 4.

Figure 6. “Fight Jim Crow Policy in California,” Chicago Defender, Sept 5, 1936, 20.

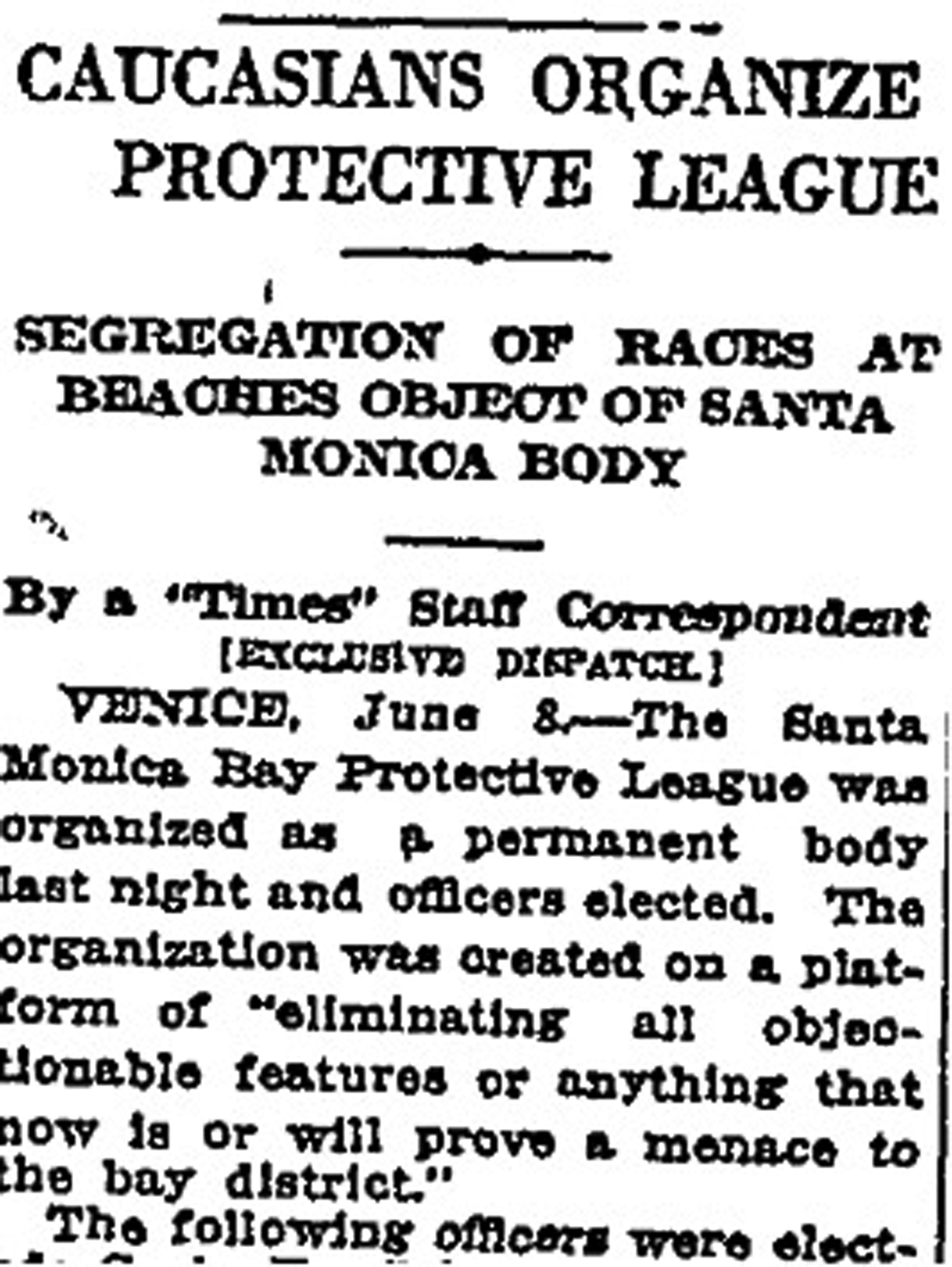

Black golfers faced obstacles along the way, though. While Black people nominally gained legal access to recreational spaces after Reconstruction, in the aftermath of the codification of segregation in the 1890s, these spaces were not only racially segregated but often highly surveilled and policed. During the long Jim Crow era, leisure and recreation spaces, whether North, South, Midwest, or West, could be legally “Whites Only,” “Members Only,” or accessible to Black fun-seekers on “colored days”—one day a week, a month, or in the case of Idora Park in Youngstown, Ohio, two days at the end of the season where the pool and other features were often “closed for repairs.” The impact of Jim Crow on Black recreation in amusement parks, swimming pools, parks, and golf courses ranged from outright exclusion to surveillance, harassment, or violence, where some spaces hired their own police forces to “protect” white patrons.Footnote 6 Black women who wanted to play golf in the South, for example, typically had to travel long distances, sometimes as much as 150 miles, to swing their clubs with friends and rivals.Footnote 7 The United States Golf Association (USGA), formed in 1894 as a national association of golf courses, sponsored national golf tournaments at public links that restricted play to white players only. And the 1916 Professional Golfers Association (PGA) excluded Black men and women's membership from its inception, and then codified it with a “Caucasians only” clause in 1934.Footnote 8

Popular illustrators, like the late-nineteenth-century children's author Edward Kemble, satirized Black leisure and recreation. As they holidayed, swam at the beach, fished, hiked, hunted, crabbed, frolicked in the snow, played polo, rode the water flume at the amusement park, or participated in athletic games, the joke was always on the “Blackberries.”Footnote 9 In the illustration shown in Figure 7, Kemble lampoons “Scotty” and “Billy Millions” on the golf course: Scotty's incompetent swing that sends his ball at Billy's head and their outrageous outfits; even their Black caddies are laughing at them. Only one of the infantilized Black women Kemble pictures is even holding a club.Footnote 10 Such grotesque caricatures of Black leisure and recreation run through over fifty years of popular culture representations of Black people. They were meant to arouse ridicule and laughter, and by the post–Reconstruction era, these kinds of illustrations bolstered pervasive Jim Crow violence.Footnote 11

Figure 7. Edward Kemble, The Blackberries and Their Adventures (London, 1898). Image courtesy of Special Collections, University of Delaware Library.

Despite such hostility, Black people in the U.S. were early participants in the game of golf. In 1899, two decades before white New Jersey dentist William Lowell began selling his popular “Reddy Tee,” it was a Black Bostonian, George Grant, who actually received the first U.S. patent for a wooden peg tee, “obviating the use of conical mounds of sand or similar material formed by [players’] fingers on which the ball [was] supported when teeing off.”Footnote 12 Grant, pictured in Figure 8, was a golf afficionado and the first Black faculty at Harvard Dental School ( also its second Black graduate) He had been chased out of his Arlington Heights neighborhood and was forced to relocate his dental practice to Beacon Hill. But he continued to golf at an “Arlington Heights meadowland” near his old house, where his daughter Frances Grant remembered caddying for her father. And while Grant never monetized his patented tee (see Figure 9), he had many manufactured at “a small shop in Arlington Heights” and gave them away to friends.Footnote 13

Figure 8. George F. Grant. Anthony W. Neal, “Dr. George Franklin Grant: Defying the Odds in 19th Century Boston, Bay State Banner, Feb. 10, 2021.

Figure 9. George F. Grant, Golf Tee, U.S. Patent 638,920, filed July 1, 1899, and issued Dec. 12, 1899.

Black children, too, proved early and innovative players. These Detroit “Golferinos” shown in Figure 10 played in 1905 with makeshift clubs, hitting what looks like a rock on a dusty platform, as a younger child looked on earnestly.

Figure 10. Detroit Publishing Co., “Golferinos,” c.1905, Prints & Photographs Division, Library of Congress [LC-DIG-det-4a12571].

Working-class boys—both Black and white—found readier access than girls to the generally elite game, because at eight or nine years old they could find opportunities to enter and learn the sport by caddying (see Figure 11). At some Southern clubs, Black (male) caddies became ubiquitous, and sometimes even required.Footnote 14 North Carolina's Pinehurst Club, for example, employed some 500 Black caddies who lived together in a community “off the seventeenth hole.”Footnote 15 Out of these groups came some of the early Black men players, like John Shippen, who although technically an “amateur,” when allowed to play against professionals often ranked higher than some of his more well-known white contemporaries.Footnote 16

Figure 11. In 1897, white men and women golfers pose at Winston, North Carolina, Twin City Golf Club with Black (and white) children caddies. Collection of the Wachovia Historical Society, Old Salem Museums and Gardens, Winston-Salem, NC.

Black caddies’ commentary and even jokes showed off Black golf skill and knowledge of the game (see Figure 12). But racist tropes denied this expertise. John D. Rockefeller and Woodrow Wilson both wrote about what they learned from their “magical” Black caddies who gave them sage advice or set a relaxed tone pre-swing.Footnote 17 Both also shared stories of being ridiculed, delivered light-heartedly of course, by their Black caddies for making a bad shot.Footnote 18 Aimed at white audiences, national golf magazines reinforced racist depictions of Black caddies with degrading stories, featuring racist vernacular quotes, and otherwise portraying them as generally “lazy, ignorant, and insolent.”Footnote 19 Such portraits dovetailed with longstanding assumptions about Black people's natural fitness for service, and servile, roles.

Figure 12. Caddies at National Colored Tournament. National Colored Tournament-outtakes, Fox News Story A7928, A7929, A7930, A7931, A7932, July 12, 1925, 35mm black and white silent film, Fox Movietone News Collection, Moving Image Research Collections, University Libraries, University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC.

Yet even while much of white popular culture derided Black leisure and recreation, Black golfing proliferated during the first three decades of the twentieth century. Some twenty years before Par-Links formed in Northern California, the first Black golf organization, United Golfers Association (UGA), formed in 1926, after two national tournaments, emerging from its former iteration “Colored Golfers Association of America.”Footnote 20 UGA not only provided a space for Black golfers to play in tournaments, but it also promoted golf beyond the elite level, albeit without all of the resources to which the national PGA had access.Footnote 21 Some of the new Black-owned and -operated clubs were private, some catered specifically to Black golfers but were public courses open to white golfers, and several of them even found financing in the midst of the Great Depression.Footnote 22

There was certainly white opposition to Black country clubs, like in Corona, California, when Eugene Nelson, Clarence Bailey, and Journee White of Los Angeles bought the white-owned and financially struggling 663-acre Parkridge Club in 1928 (Figure 13). The club was lavish, replete with an eighteen-hole golf course, hotel, clubhouse, tennis courts, a large plunge pool, an indoor spa, and a private air strip that catered to Hollywood celebrities. The Chicago Defender called it “the acquisition of the finest recreational project ever owned and operated anywhere.” White club members and the Ku Klux Klan organized against the sale, burning a cross on the club's front lawn, and terrorizing Nelson, Bailey, and White into withdrawing their bid.Footnote 23

Figure 13. Parkridge Country Club, Lost Architectural Treasures, Corona Historic Preservation Society, https://www.corona-history.org/corona-ca-local-treasures.html.

But other ventures were successful, such as the Mapledale Country Club just outside Boston and New Jersey's Shady Rest Country Club, about fifteen miles outside of New York City, bought from white owners by a Black investment group in 1922 (see Figure 14). Abraham Lincoln Lewis owned the Lincoln Country Club in Jacksonville, Florida, which boasted tennis courts, croquet courses, trap shooting, rifle ranges, boating, and fishing. The club was so successful, Lewis later founded the Black seaside resort American Beach on Amelia Island just north of Jacksonville.Footnote 24 Atlanta's Black country club, which opened in the late 1920s, had a nine-hole course, a swimming pool, tennis courts, a clubhouse, and a dancing pavilion, and was the only local course Black people could play, since the city's municipal course was off-limits to Black golfers, even for segregated use.Footnote 25

Figure 14. Members of Shady Rest Golf and Country Club, 1925. National Colored Tournament-outtakes, Fox News Story A7928, A7929, A7930, A7931, A7932, July 12, 1925, 35mm black and white silent film, Fox Movietone News Collection, Moving Image Research Collections, University Libraries, University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC.

Although UGA did not allow Black women to compete in tournaments until 1930, Black women played and supported the game from much earlier.Footnote 26 While many Black men who became “professional” golfers, at least on the growing Black circuit, came up through caddying for white players, Black women, such as Frances Grant, often found an entrée into the sport by informally caddying for their fathers. Others learned the game so that they could be a partner on the putting green for their spouses, or so they said.Footnote 27 Black women players are featured swinging their clubs, cheering each other on, and sitting for the club membership portrait in footage from UGA's 1925 tournament at Shady Rest in New Jersey (see Figure 14). And Black journalist and sportswriter Nettie George Speedy, co-founder of Chicago's Black women's golf club, wrote a regular golf column for Black national newspaper Chicago Defender, often speaking directly to a Black women audience (see Figure 15).Footnote 28

Figure 15. Nettie George Speedy, “Golf,” Chicago Defender, Apr. 9, 1921, 15.

The Chicago Defender and the Baltimore Afro American ran stories on women's golf, announcing tournaments, offering instructions, and sharing fashions and “golf teas” menus, all evincing Black women's early participation and interest in golfing.Footnote 29 “Woe Confronts Women Golfers with High Heels,” read one early Chicago Defender article, highlighting the tension for some women players between “their love of the game and appearance.” But that love of the game was strong! One weekend at Chicago's Jackson Park, some “six hundred women” showed up to play only to be sent to the local cobbler to have their heels cut down so as not to tear up the turf; many of them opted to have their heels trimmed so that they could play.Footnote 30 “Down the Fairway” ran for a decade, and was mostly written by Black sportswriter Russ Cowan, editor of Detroit's Michigan Chronicle and husband of professional golfer Thelma McTyre Cowans (see Figure 16).Footnote 31

Figure 16. “Down the Fairway,” column header in The Chicago Defender, which the Black sportswriter Russ Cowan—editor of the Michigan Chronicle and husband of professional golfer Thelma McTyre Cowans—wrote for about a decade.

Black women played golf for the social, emotional, and athletic benefits. “Down the Fairway” columns featured women's physical and mental golf skills that allowed for “good firing” and “beautiful pitch shot[s],” which many women attributed to their “strict attention to lessons.”Footnote 32 Black women were known to take their time at the tee, being thoughtful about each shot, what some Black men complained about as “standing and waiting” before and after each hit.Footnote 33 One of DC's Wake-Robin Club members who “loved the game” remembered that she got started “just [to] … get outdoors.” “I loved fresh air,” she said.Footnote 34 But when Black women “took over the course,” it was also about sociality, community, and camaraderie during the long slow game. When Cowans interviewed Hazel Bibb, president of Detroit's Pitch and Putt Club, Bibb was exhausted, just having spent six hours playing with beginners, which she joked was “harder than playing 36 holes in a tournament.”Footnote 35 After one of Chicago Women's Golf Club's tournaments at Gleason Park in Gary, Indiana, the women spent Saturday afternoon with “national women's champion” (and one of the founders of the club) Ann Gregory, who had “power[ed] the ball” during play, and then hosted the club at her home where she “fed us some golden brown fried chicken … and regaled us with stories about her [grandmother and her] childhood days in Mississippi.” Gregory of course also gave her guests a tour of her “trophy room.”Footnote 36 This social aspect was true for the Par-Links club as well, whose skills at hosting successful after tournament parties scaled up for the 5th annual Western States Golf Association Championships in San Francisco. Though they were newly formed (and did not appear as an official member in the program), Par-Links co-hosted the “‘Come as you are’ indoor picnic and barbecue at the Fillmore Auditorium” in San Francisco, where “everything [was] on the house.” Attendees would have to pay however, if they wanted “stronger drinks than beer,” but their hosts cautioned them to stick to beer if they wanted to ensure they could “make it through the final eighteen holes” the next day.Footnote 37

Black women's sociopolitical interest and participation in golf motivated the few Black businesswomen with capital to also invest in leisure and recreation real estate. By World War II, New Jersey Black haircare product entrepreneur Sarah Spencer Washington opened the private Apex Country Club and Golf Course, with its nine-hole course, swimming pool, restaurant and bar, picnic grounds, and hiking trails, after she had experienced discrimination when she tried to play at a local course.Footnote 38 Washington added the country club to her growing empire, Apex Enterprises, which included Apex Beauty Colleges, Apex Publishing Company, and Apex News and Hair Company headquartered in Atlantic City.Footnote 39

By the 1930s, white-owned beauty supply companies were placing advertisements, like Figure 17, in Black newspapers to woo Black women golfers (and tennis players) with “intelligent hosiery selection” and other products “for hard-wear activities such as hiking, golf, [and] country walking.” These products included deodorant, soap, and facial skin creams to protect from or “correct” Black women's skin tone from the “darkening” kiss of the sun during their outdoor play.Footnote 40

Figure 17. Advertisement “Fun Under the Sun,” Baltimore Afro-American, May 28, 1933, 5.

Meanwhile, a surge in urban miniature golf courses also spoke to rising interest in the game even in places lacking the space for full courses, extending access to the sport to young and old, poor, and working-class Black women. Some courses were professionally designed, and others were makeshift, showing up in vacant lots and in alleyways, all with late-night hours. Many of the indoor spaces sported a night club vibe, with jazz musicians performing and playing golf.Footnote 41 “Golf all winter long [to] keep your form good,” one Harlem course located upstairs in the old Apollo Theatre advertised in the New York Amsterdam News, promising a “well heated, well ventilated” space with “18 holes with tricky traps and harassing hazards.” Above the ad's copy in Figure 18, an illustration featured a stylish woman with a good stance readying to send her ball down the miniature course.Footnote 42

Figure 18. “Winter Golf Indoors,” advertisement, New York Amsterdam News, Nov. 19, 1930, 12.

Maria Jones Thompson, who won back-to-back titles in 1930 and 1931 at the first two UGA National Opens that allowed Black women to compete, found such “peewee” courses good places to not only improve your game “almost any night,” but where you could get a glimpse of “sharpshooters and near sharpshooters making matches for the next day or week.”Footnote 43 Lauding golf as a respectable dating activity, the educator Charlotte Hawkins Brown put in a miniature course at Palmer Memorial Institute in North Carolina. Other Black secondary schools and colleges soon followed.Footnote 44

Black women initiated college golf programs, women's auxiliary golf organizations, or stand-alone women's clubs when men's clubs did not allow for an auxiliary. Some of their stated goals, as Washington, DC's Wake Robin Club put it, were to “perpetuate golf among Negro women, to make potential players into champions, and to make a permanent place for Negro women in the world of golf.”Footnote 45 In 1937, when the group formed, DC's Black golfers had few local options for playing—the “colored” Lincoln Memorial Golf Course, which had only 9 holes and would soon be razed to make way for the construction of approaches to the Memorial Bridge and the Jefferson Memorial.Footnote 46 Along with DC's Black men's Royal Golf Club, the Wake Robin Club spent its first two years petitioning the Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes to do something about “the conditions under which golfers are forced to play in [DC].”Footnote 47 The two clubs finally got the nine-hole Langston Golf Course, named for Howard University's first law school dean and first Black Virginia congressional representative, John Mercer Langston, built on an abandoned city dump in Northeast DC, with no grass, “surrounded by disused tires and a sewage ditch.” But these DC golfers also gathered Black investors and founded the private National Capital Country Club on twenty-three acres in Laurel, Maryland (see Figure 19).Footnote 48

Figure 19. National Capital Country Club. William Henry Jones, “Golfers at the Country Club,” 1927, Jean Blackwell Hutson Research and Reference Division, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library, New York, NY, https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47df-2cd7-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99.

A few months after Wake Robin formed, three Black women golfers organized the Chicago Women's Golf Club (CWGC) with objectives that included maintaining interest in the sport during cold Chicago winters, supporting beginners with lessons “necessary to play and enjoy the game,” and in time launching a junior golfers’ program called the Bob-o-Links (see Figure 20). By the end of the 1950s CWGC would become one of the only Black women clubs to have its own clubhouse.Footnote 49 CWGC member, Ann Gregory, while officially an “amateur,” was the first African American woman to play many early tournaments. In 1959 Gregory won the United States Golf Association Women's Amateur, held at the white-members-only Bethesda Congressional Golf Club. After her win, Gregory was denied entry to the player's banquet inside the clubhouse.Footnote 50 Thelma McTyre Cowans, also a CWGC member and an accomplished college athlete (one of three sisters who played golf competitively), also won five UGA National Women's Open titles that decade.Footnote 51

Figure 20. Chicago Women's Golf Club Bob-o-Links junior program 1954. Courtesy of CWGC.

Before Par-Links came together, Black golfing clubs flourished on the West Coast, too.Footnote 52 In 1953, members of LA's Black women's Vernoncrest Golf Club helped to found the Western States Golf Association as a hub for Black golf clubs from Arizona to Washington State. LA's Community Junior Golf Association also launched a program for eight- to eighteen-year-olds under the leadership of two Vernoncrest members, Lillian Fentress and Doris Joyner (see Figure 21). Fentress was also the business manager for the Tee Cup, the official organ of the WSGA. Joyner would be “in charge of physical fitness for the small fries.”Footnote 53 Such junior golf programs helped prepare Black girls and young women for athletic scholarships.Footnote 54

Figure 21. “Junior Golf Makes Deb Sat., Feb. 8,” California Eagle, Jan. 30, 1958, 8.

California UGA tournaments had a joyous and social air that did not always meet with approval from some Black players. One tournament, sponsored by LA's Black men's Cosmopolitan Golf Club, was praised for presenting “trophies and prizes … on the 18th green,” instead of the usual “camp meeting flavor,” which often included “drinking whiskey in the open,” “placing bets on the greens,” and “serving too much food.”Footnote 55

LA's Vernoncrest membership initially included activist Maggie Hathaway, an actor who had faced (and organized against) discrimination in the film industry. Hathaway's 1955 introduction to golf came from a challenge by boxer and “Black golf ambassador” Joe Louis (see Figure 22). Hathaway had sought out Louis in order to chastise him for using his celebrity status to take advantage of playing on courses closed to Black professional players. She found him, she said, on the eighth hole in LA's municipal course at Griffith Park. When he made a good shot, she told him, “anyone can do that,” and he wagered if she could he would buy her “a bag of golf clubs.” On her first try, Hathaway hit the green and Louis bought her first set of clubs.Footnote 56

Figure 22. American heavyweight boxer Joe Louis (1914–1981) dreams of getting out to the golf course, 1949. “Joe Louis Golf Clubs,” 1949. Photo by Afro American Newspapers/Gado/Getty Images.

During Hathaway's Hollywood acting career, she played extras and appeared in films like Cabin in the Sky, where her “statuesque figure” led to a job as Lena Horne's body double. But after being cast as an extra in a Woodrow Wilson biopic where she was asked to wear a handkerchief on her head and sit in a field of cotton, Hathaway patently refused and took a limo off the lot. She then began a cabaret singing and recording career.Footnote 57 An avid golfer, Hathaway became a sports columnist for the California Eagle and the LA Sentinel covering West Coast golf and soon formed the Minority Associated Golfers with a mission to open access to clubs and to desegregate employment in the growing golfing industries.Footnote 58 Hathaway would later be inducted into the National Black Golf Hall of Fame (1994) and have a nine-hole course named for her in L.A.'s Jesse Owens Park.Footnote 59

So by the time Lavanda Scott, Eola Paige, and Arjere Johnson (seated) and Edna Dotson, Maye Reid, Juanita Wilson, and Ruth Chatmon (standing), seven of the founding members and major officers of Par-Links Club, sat for a group portrait (see Figure 23), Black women had been playing golf recreationally, working to institutionalize themselves within its spaces, and fighting to make the sport accessible beyond the elite for over twenty-five years.Footnote 60 With the motto “Good Conduct and Courage Lead to Honor,” membership in the East Bay Par-Links Golf Club was open to any golf-playing woman, “eighteen years or older,” who was in “good amateur standing,” and could pay both the $10 joining fee and the annual $12 dues.Footnote 61

Figure 23. Par-Links Golf Club (left-to-right, seated): Lavanda Scott, Eola Paige, Arjere Johnson, (left-to-right, standing) Edna Dotson, May Frances Reid, Juanita Wilson, Ruth Beckford Chatmon, 1958, Par-Links Golf Club Scrapbook (MS 214), African American Museum and Library at Oakland, Oakland Public Library, Oakland, CA.

That the club hired Harry Cox's studio for its club portraits in the first winter of its existence is worthy of note. Cox was a World War II and Korean War veteran, who upon return trained with the Ansel Adams Photography School and opened his studio in San Francisco.Footnote 62 Cox photographed several Bay Area National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) social events, political protests such as the 1955 picket against the San Francisco Yellow cab company's discriminatory hiring practices, and he shot portraits of prominent Black Californians.Footnote 63 Many Black golf clubs, men's and women's alike, had professional photographs taken as members, and other players posed on fairways or in decorated homes, showcasing their belonging not only to the sport of golf, but to a particular tradition of Black visual representation, one inclusive of the politics inherent in Black recreation and leisure.Footnote 64

Par-Links played courses all over northern California from the Alameda Municipal Course to the Sonoma Golf and Country Club.Footnote 65 The club held monthly evening meetings, hosted guests, and staged social events, where members watched documentary films on golf history or availed themselves of lessons from professional instructors.Footnote 66 The group's organizational structure mirrored that of other clubs: it included elected officers, a Handicap Committee, and a Tournament Chairman, who organized monthly and annual club competitions.Footnote 67 In Figure 24, Arjere Johnson, one of the founders and Par-Links Golf Club secretary, is pictured with Edna Dotson.Footnote 68 Dotson was Tournament Chair and kept meticulous notes on competitions. Only the first two from 1959 survive in the Par-Links collection, but in those reports, Dotson documented participating members, scores, green fees, which seemed suspiciously to fluctuate, the weather conditions (often spring or fall downpours in a pre-drought northern California), and prizes.

Figure 24. Edna Dotson presenting Arjere Johnson tournament trophy, 1960s, Par-Links Golf Club Scrapbook (MS 214), African American Museum and Library at Oakland, Oakland Public Library, Oakland, CA.

Par-Links frequently played with the Black men's Bay Area Golf Club. It also hosted Black women guests from other clubs like San Francisco's Fairway Golf Club, the first Black women's club in northern California, formed by Maud Thomas a few years before Par-Links.Footnote 69 Par-Links tournaments had fun themes, like the Ladder, or the Fewest Putts, or the Throw-Out where DoraLee Petty won with a score of 52 net having “tossed out the 9th, 10th, and 14th holes.” In addition to trophies seen in some of the photographs, players also got a chance to win a golf umbrella, a “Golf Pocket Purse in the club colors,” or a “Caddy Cart Score Case.”Footnote 70

Black women's golf organizations like Par-Links had important political dimensions, facilitating the fight against segregation and discrimination and boosting efforts to expand access, even if merely by their presence en masse at a municipal course. These clubs furnished networks, role models, and instruction for young Black women who were shut out of caddying in most places. They also lent weight to efforts to challenge the PGA's “caucasian only” clause, which finally forced action by California's Attorney General Stanley Mosk in the summer of 1960. Ruling that PGA membership bylaws were “in direct violation to the Federal 14th Amendment and the California Constitution,” Mosk withdrew PGA members’ free play privileges on public courses. His decision also mandated that when PGA tournaments took place at California public courses, “all qualified players must be permitted to compete.”Footnote 71 This had a direct impact on the Northern California courses where the women of Par-Links played, including the one where the 1959 WSGA championship happened, Sharp Park (see Figure 25). In response, though, the PGA pivoted to sponsoring “invitationals” instead of tournaments to avoid allowing Black players to compete.Footnote 72

Figure 25. Award ceremony at 1959 Western States Golf Association Tournament at Sharp Park. Western States Golf Association Championships Program, 1959, Par-Links Golf Club Scrapbook (MS 214), African American Museum and Library at Oakland, Oakland Public Library, Oakland, CA.

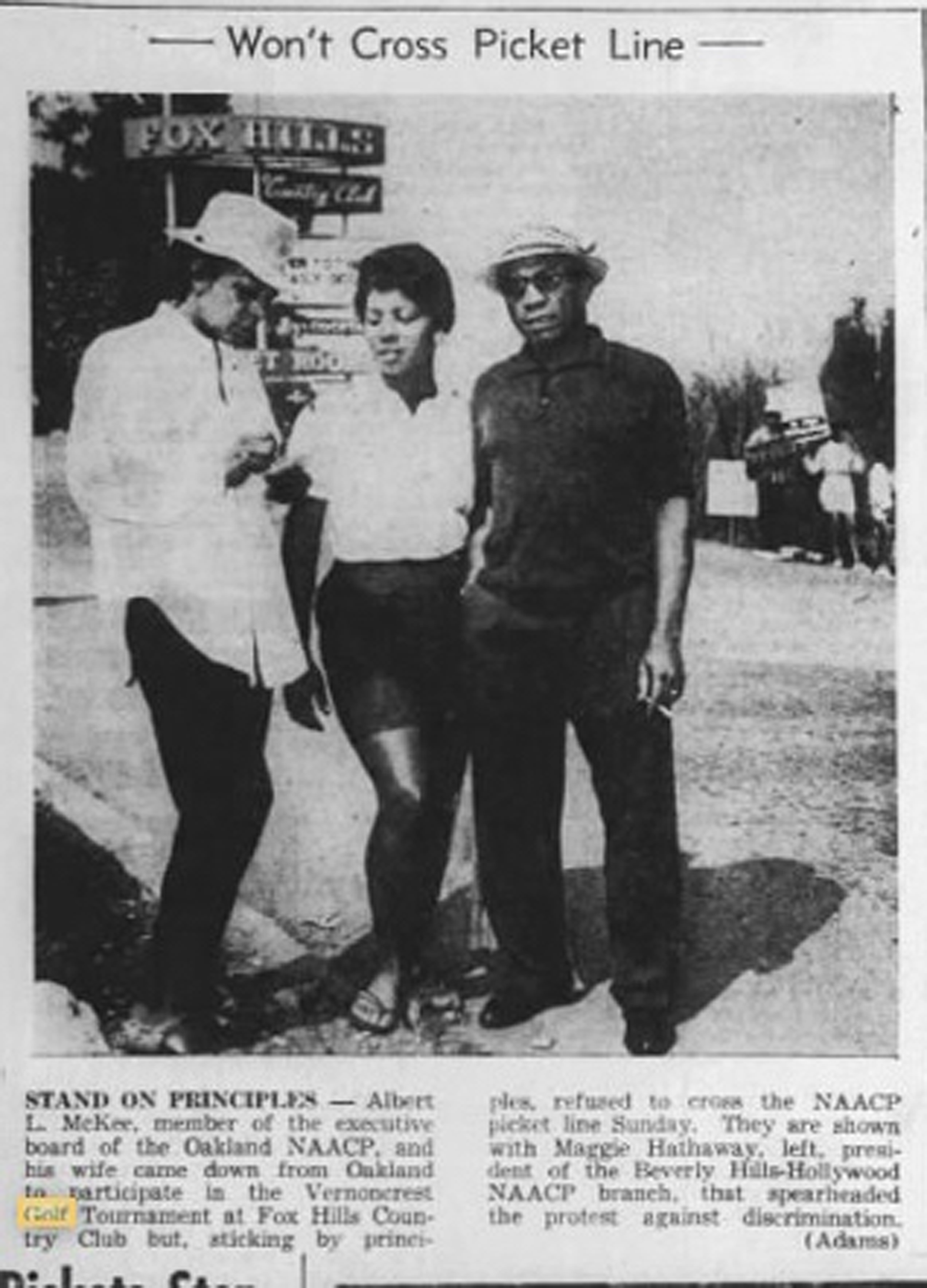

Maggie Hathaway's leadership was pivotal in the fight for access to play in California. In her California Eagle golf column “The Tee,” Hathaway often called for boycotts and pickets of California's “notorious lily white” clubs and courses, where Black women were not allowed membership and where fees were raised on the weekends to discourage Black golfers from playing.Footnote 73 In 1962, Hathaway, who by then had co-founded the NAACP Beverly Hills branch, wrote: “If you are not frightened … and you seek freedom in golf parks and recreation facilities, then come help picket Fox every weekend and sometimes on Mondays and holidays.”Footnote 74 Fox Hills Country Club, the target of Hathaway's protest, had a history of denying membership to Black golfers despite their steady patronage. Days later the California Eagle featured Hathaway; Par-Links member and “Berkeley school teacher,” Ramona Maples; and Maples’ husband Albert Mckee, of the Oakland NAACP chapter, as they posed in front of the Fox Hills sign just ahead of other protesters. “Won't Cross Picket Line” read the picture's headline (see Figure 26).Footnote 75

Figure 26. “Won't Cross Picket Line,” California Eagle, Sept. 6, 1962, 1.

Black women's golf organizations were politically significant in the movement against Jim Crow. They also fulfilled equally important social and personal functions. Clubs like Par-Links highlight Black women's insistence on “vacation and recreation without humiliation,” as the 1952 cover of the Black Travelguide publication exclaimed. The guide featured Urban League Secretary Alice Collum, “noted [Cleveland] sportswoman and civic leader,” standing astride clubs and her convertible, preparing to navigate segregated travel (see Figure 27). Black women golfers who formed clubs—from DC to Detroit to Northern and Southern California—appreciated being out on the links together, encouraging each other, and celebrating each other's wins. Inviting local professionals for lessons and providing advice in Black newspapers reflected their desires to not only improve their personal games, but an appreciation of the focused interiority and mindfulness, and athleticism of standing at the tee, of the meditative pace of play.

Figure 27. 1952 Travelguide cover page with Alice Collum, Cleveland Urban League Secretary. “Travelguide 1952,” Jean Blackwell Hutson Research and Reference Division, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library, New York, NY, https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/62cf40b2-d0fc-346b-e040-e00a18065229.

Black newspaper articles that reported on tournaments often also reported on social events that followed or preceded play, who was visiting from out of town, and to what clubs they belonged, as well as what local members had been absent because they were on vacation or tending to a sick relative elsewhere.Footnote 76 In the political and social context of much of the twentieth century, Black women, whether working or middle and aspiring class, were often in multifaceted service “to the race.” Time to themselves and with each other was both cherished and necessary. As 23-year-old Agricultural Adjustment Administration worker Anne Winston told the meeting of DC's nascent Women's Domestic Union as they organized a boycott of a local discriminatory laundry in 1938, she would not be available to join the picket line that Saturday because it was her day off and she would be “playing golf” instead. (Incidentally, Anne would find time to do both.)Footnote 77

Now, as then, Black women golfing cannot avoid the politics of Black leisure and recreation. One Saturday morning in April 2018, five Black women belonging to “Sisters in the Fairway” showed up to play a round at the semi-private Grandview Golf Club in York, Pennsylvania (see Figure 28).Footnote 78 Their twenty-odd-strong organization was about seven years old, but they did not have a home course yet. After attending an opening party at Grandview the previous month, they decided to become members. They had played holes at the club before, but this Saturday was the first time they would use the course as members. Delayed by frost on the green and then a scramble tournament ahead of them, they eventually got started. They were not stressed about the delay; they were there to relax, for some “respite,” to do something they loved, and spend time together, they said.Footnote 79

Figure 28. Sisters in the Fairway (photo credit: Myneca Ojo, Director of Diversity & Inclusion, Pennsylvania Turnpike Commission).

At the third hole, they were approached by a small group of white men including the owner and his father, who was a former York County commissioner. The men accused them of holding up the course, of “not keeping pace,” despite the fact that the group of white men golfers behind them denied this. When they finished the first nine, they decided to take a break for something to drink, a snack, and to visit the restroom. They offered the group behind them to play through, but the group declined because they too were going to take a break. When the Sisters got back on the course, the owner, his father, and two other men approached again. This time, accusing them of taking too long of a break, they asked the women to leave. When the women protested that they were not playing too slowly, the owner first offered to refund the cost of play for the day, then to refund their membership, and then he called the cops. After the police arrived and determined it had not been appropriate to call them in the first place, the women left the course, confessing that they were too shaken to continue play.Footnote 80

The Sisters did not make a formal complaint, but spurred on by social media attention, the Pennsylvania Human Relations Commission (PHRC) nevertheless convened two hearings, where the owners of the Grandview refused to appear and where at least one of the golfers in the group playing behind the Sisters spoke on their behalf. In press interviews and testimonies to the PHRC, the women made one thing clear: golf had been a space of refuge, where they could “let [their] hair down,” and that had been taken from them that day. Before they were disturbed, they were having a “great drive day … slamming that ball,” one remembered. “I just wanted to play golf,” another woman told the commission. “They tried to ruin what we love,” still another reported, and “what I loved about golf was that it was … nice and refreshing,” but “now after this, that outlet is gone.”Footnote 81

Black women golfers then and now played the slow-paced meditative game (see Figures 29 and 30). Even nine holes could take upwards of four hours: appreciating the time with each other, focusing their minds and bodies, planting their feet in a strong stance at the tee, controlling the hip and leg twist and the power of the swing. For as one contemporary leisure player told me, “The ball will go a far way if you set up right,” as she expressed pride in her swing, which always got her ball across bodies of water on the course.Footnote 82

Figure 29. “Three Par-Links players posing with golf clubs, 1960s.” Par-Links Golf Club Scrapbook (MS 214), African American Museum and Library at Oakland, Oakland Public Library, Oakland, CA.

Black leisure and recreation continue to be important parts of Black life, offering moments for relaxation, refuge, and respite, standing in opposition to the long history of uneven access to and prohibition of these moments and from the spaces in which to enjoy them. The activities of Black women's golf clubs such as Par-Links offer a reminder to take Black women's recreation practices and leisure culture as serious dimensions of both Black interior life and self-care, and of Black sports history. This history reveals the fluidity of Black politics and identity performance in and through leisure and recreational spaces, and the ways that, out of necessity, these activities were and continue to be both personally and politically significant.Footnote 83

Figure 30. Par-Links Members, including Edna Dotson, Lavanda Scott, Nell Wilson, Cleo Johnson, Juanita Wilson. “Edna Dotson and Arjere Johnson with Par-Links Golf Club members,” 1960s, Par-Links Golf Club Scrapbook (MS 214), African American Museum and Library at Oakland, Oakland Public Library. Oakland, CA.