Introduction

WHO stresses the importance of interprofessional collaboration to providing good care based on a holistic perspective (Gilbert et al., Reference Gilbert, Yan and Hoffman2010; World Health Organization WHO, 2002). Interprofessional collaboration, ‘the process by which different health and social care professional groups work together’ (Reeves et al., Reference Reeves, Pelone, Harrison, Goldman and Zwarenstein2017), may be described as a looser form of teamwork that shares some but not all features of teamwork, including accountability to collaborators, some interdependence, and clarity of roles and goals (Reeves et al., Reference Reeves, Xyrichis and Zwarenstein2018). Factors important to effective interprofessional collaboration include sharing information, trust, respect, communication, a learning culture and facilitative leadership (Reeves et al., Reference Reeves, Lewin, Espin and Zwarenstein2010).

It is crucial for health care professionals to have the appropriate knowledge and collaborate when caring for older people and meeting their nutritional care needs, including in the early and late palliative phases of disease (Arvanitakis et al., Reference Arvanitakis, Beck, Coppens, De Man, Elia, Hebuterne, Henry, Kohl, Lesourd, Lochs, Pepersack, Pichard, Planas, Schindler, Schols, Sobotka and Van Gossum2008). The knowledge and perspectives of both nurses and physicians is required, but they do not always collaborate (Neergaard et al., Reference Neergaard, Olesen, Jensen and Sondergaard2010; Johannessen and Steihaug, Reference Johannessen and Steihaug2014; Reeves et al., Reference Reeves, Xyrichis and Zwarenstein2018). Historically, their collaboration was shaped by the hierarchal nature of the relationship between the professions (Stein, Reference Stein1967), but changes have increased nurses’ autonomy (Miller and Kontos, Reference Miller and Kontos2013), influence over medical decision-making (Svensson, Reference Svensson1996; Allen, Reference Allen1997), and role in defining rules for interaction on wards (Svensson, Reference Svensson1996). However, unequal power distribution still affects collaboration (Reeves et al., Reference Reeves, Rice, Conn, Miller, Kenaszchuk and Zwarenstein2009; Tang et al., Reference Tang, Zhou, Chan and Liaw2017), as do workload (Phillips et al., Reference Phillips, Piza and Ingham2012), organizational structure (Tang et al., Reference Tang, Zhou, Chan and Liaw2017) and other factors (Altin et al., Reference Altin, Tebest, Kautz-Freimuth, Redaelli and Stock2014), resulting in a gap between best and actual practice (Miller and Kontos, Reference Miller and Kontos2013).

Continuing and interprofessional education (IPE) for active professionals can contribute to closing this gap (Arvanitakis et al., Reference Arvanitakis, Beck, Coppens, De Man, Elia, Hebuterne, Henry, Kohl, Lesourd, Lochs, Pepersack, Pichard, Planas, Schindler, Schols, Sobotka and Van Gossum2008; Thistlethwaite, Reference Thistlethwaite2012b). The rationale for IPE is that learning together enhances future collaboration (Thistlethwaite, Reference Thistlethwaite2012a). In IPE, two or more professions learn about, from and with each other (Delva et al., Reference Delva, Jamieson and Lemieux2008; Zwarenstein et al., Reference Zwarenstein, Goldman and Reeves2009; World Health Organisation WHO, 2010). Some studies show that IPE can improve patient health care and outcomes (Zwarenstein et al., Reference Zwarenstein, Goldman and Reeves2009; Gilbert et al., Reference Gilbert, Yan and Hoffman2010; Thistlethwaite, Reference Thistlethwaite2012b). Evidence also suggests that IPE in primary health care may lead to shared understanding, improved communication and teamwork (Delva et al., Reference Delva, Jamieson and Lemieux2008; Oandasan et al., Reference Oandasan, Gotlib Conn, Lingard, Karim, Jakubovicz, Whitehead, Miller, Kennie and Reeves2009; Hämel and Vössing, Reference Hämel and Vössing2017), although there is not yet enough evidence to clearly conclude that practice-based interventions improve interprofessional collaboration and interprofessional care (Reeves et al., Reference Reeves, Perrier, Goldman, Freeth and Zwarenstein2013, Reference Reeves, Pelone, Harrison, Goldman and Zwarenstein2017).

In Swedish primary care, the responsibilities of district nurses (DNs) and general practitioners (GPs) include nutritional care for patients cared for at home. It is often difficult for primary health care professionals to participate in continuing education, even when they need to update their skills (Anwar and Batty, Reference Anwar and Batty2007; Baxter et al., Reference Baxter, DiCenso, Donald, Martin-Misener, Opsteen and Chambers2013). Moreover, in contrast to IPE for students, IPE is scarce for clinically active professionals, both in Sweden and elsewhere (Ekebergh, Reference Ekebergh2011; Darlow et al., Reference Darlow, Coleman, McKinlay, Donovan, Beckingsale, Gray, Neser, Perry, Stanley and Pullon2015; Kent and Keating, Reference Kent and Keating2015). Our team therefore developed an IPE intervention for DNs and GPs on nutritional care in the early and late palliative phases of disease (Berggren et al., Reference Berggren, Orrevall, Odlund Olin, Strang, Szulkin and Tornkvist2016a, Reference Berggren, Strang, Orrevall, Ödlund Olin, Sandelowsky and Törnkvist2016b). In previous studies, we have evaluated the design of the intervention (Berggren et al., Reference Berggren, Strang, Orrevall, Ödlund Olin, Sandelowsky and Törnkvist2016b) and its effectiveness in increasing knowledge (Berggren et al., Reference Berggren, Orrevall, Odlund Olin, Strang, Szulkin and Tornkvist2016a, Reference Berggren, Odlund Olin, Orrevall, Strang, Johansson and Tornkvist2017).

In the current study, we took advantage of data from this intervention to deepen the understanding of micro-level interactions between nurses and physicians during continuing IPE. The specific context was a discussion of an authentic case about nutritional care for an older women who was in a palliative phase and lived at home. Participating DNs and GPs came from the same workplace. Nutritional care for patients living at home also involves collaboration with other health care providers, such as dietitians, home help service personnel and social workers. However, they were not the focus of this study.

Interview and observational studies about collaboration may give different results (Allen, Reference Allen1997), so observational studies on the process and results of IPE have been called for (Reeves et al., Reference Reeves, Rice, Conn, Miller, Kenaszchuk and Zwarenstein2009). The current study thus adds much-needed observational data on collaboration in the context of IPE. To better understand micro-level interactions between professions, researchers have also called for the development theory driven by data (Reeves et al., Reference Reeves, Lewin, Espin and Zwarenstein2010; Green, Reference Green2013) rather than applying existing social science theory to empirical data, as is more usual (Kvarnstrom, Reference Kvarnstrom2008; Biggs and Tang, Reference Biggs and Tang2011; Thistlethwaite, Reference Thistlethwaite2012a; Clark, Reference Clark2013; Hean et al., Reference Hean, O’Halloran, Craddock, Hammick and Pitt2013; Reeves and Hean, Reference Reeves and Hean2013). Instead of taking its point of departure in one or several theories, the present study aimed to construct a tentative theoretical model using observational data on interactions between DNs and GPs during IPE. In the discussion section, the resulting model and its conceptual categories are discussed in relation to relevant theories.

Aim

To explore DNs’ and GPs’ interaction in a case seminar when discussing nutritional care for patients in palliative phases cared for at home and to construct a theoretical model illuminating the professionals’ main concern.

Method

The continuing interprofessional educational intervention

The intervention was based on a three-part model (web-based programme, practical exercise and case seminar) adapted to primary health care circumstances (Berggren et al., Reference Berggren, Strang, Orrevall, Ödlund Olin, Sandelowsky and Törnkvist2016b). The factual content in the web-based part was about nutritional care and focused on patients’ differing needs in the early and late palliative phases of disease. In the practical exercise, the DNs visited patients with home care, who were in the early palliative phases of disease, to assess their risk for undernutrition (Vellas et al., Reference Vellas, Guigoz, Garry, Nourhashemi, Bennahum, Lauque and Albarede1999). Each DN then discussed the outcome with a GP, and the professionals undertook any agreed-upon actions. Finally, the professionals took part in a case seminar at their own health care centre. The objective of the case seminar was to enable the professionals to link what they had learned with their previous experience to relate their knowledge to everyday practice. Case methodology was used; participants solved an authentic case via discussion (Mauffette-Leenders et al., Reference Mauffette-Leenders, Erskine and Leenders1997; Nordquist and Johansson, Reference Nordquist and Johansson2009; Biggs and Tang, Reference Biggs and Tang2011; Nordquist et al., Reference Nordquist, Sundberg and Johansson2011).

The case

The case is about a frail 80-year-old woman, who has difficulty eating, is affected by rheumatism and lives alone in an apartment. Prior to the case seminar, the professionals read the version of the case written from the perspective of their own profession. At the seminar, they also read the version written from the perspective of the other profession. Two facilitators (one DN and one GP) led the seminar, stimulating discussion as the professionals tried to solve the case.

Design

Grounded theory method (GTM) informed by the work of Kathy Charmaz (Charmaz, Reference Charmaz2014) was used to analyse the case-seminar discussions between DNs and GPs. This method was chosen because it is suitable for exploring interactions and social processes in professionals’ natural environments and for generating concepts and constructing theories in less-studied fields (Charmaz, Reference Charmaz2014).

Participants and setting

An invitation was sent to the 196 primary health care centres in Stockholm County, Sweden. The study was conducted between 2011 and 2012 and included professionals working with home care at the nine centres that were interested in participating. Eighty-seven of 93 professionals working with home care at these centres (46 DNs and 41 GPs) participated in eight case seminars (6 to 16 professionals per seminar). The seminars were 1.5 h long, took place at the professionals’ workplace and were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim. Because our main interest was interprofessional interaction, comments from and discussions between facilitators and professionals were omitted from this analysis.

Analysis

We chose to deviate from standard theoretical sampling, as we anticipated that we would gather a large data set via the planned case seminars and would have the opportunity to conduct additional seminars if needed to achieve saturation. To compensate for this deviation, we interrogated the transcripts of the seminars using a flexible, stepwise analytical procedure. The analysis started with initial coding: open, line-by-line coding of the full transcript of one case seminar and the last section (discussion summary) of the transcripts of all case seminars. This analysis informed us about the variation in data in the case seminars and gave us 23 tentative categories with 71 subcategories. Based on this list of categories, analyses of the next two transcripts continued. We compared incident to incident and to the developing list of categories. Focused coding started when the list of categories had developed into a more congruent set of significant categories. At this point, new questions were put to the data, and transcripts from seminars of specific interest for developing a certain category were analysed or reanalysed. For example, when ‘blocking an interprofessional dialogue’ became an important category, transcripts from case seminars with few ongoing interprofessional dialogues were analysed, using questions such as ‘How is an issue raised?’ and ‘How is an issue responded to?’ When ‘learning’ emerged as an important category, transcripts from seminars where the dialogue reflected little learning were analysed along with transcripts from seminars where the dialogue reflected more learning. Questions posed to the data became increasingly focused, for example: ‘What do these data say about learning?’ and ‘What is the difference between one type of learning and another type of learning?’ All categories were filled and conceptualised by recoding transcripts that were of substantive importance. Finally, the theoretical codes of ‘blocking’ and ‘facilitating’ were used to integrate several-lower order categories and link the main categories together, thus constructing a theoretical model of the social process. Reflections were noted through memo writing and used throughout the entire analysis. Because the variation in data in the case seminars was sufficient to fill the emergent categories and saturate the conceptual categories, it was not necessary to collect new data from later case seminars. However, as in all grounded theory studies, the substantive grounded theory is a hypothesis, although the hypothesis is well grounded in data.

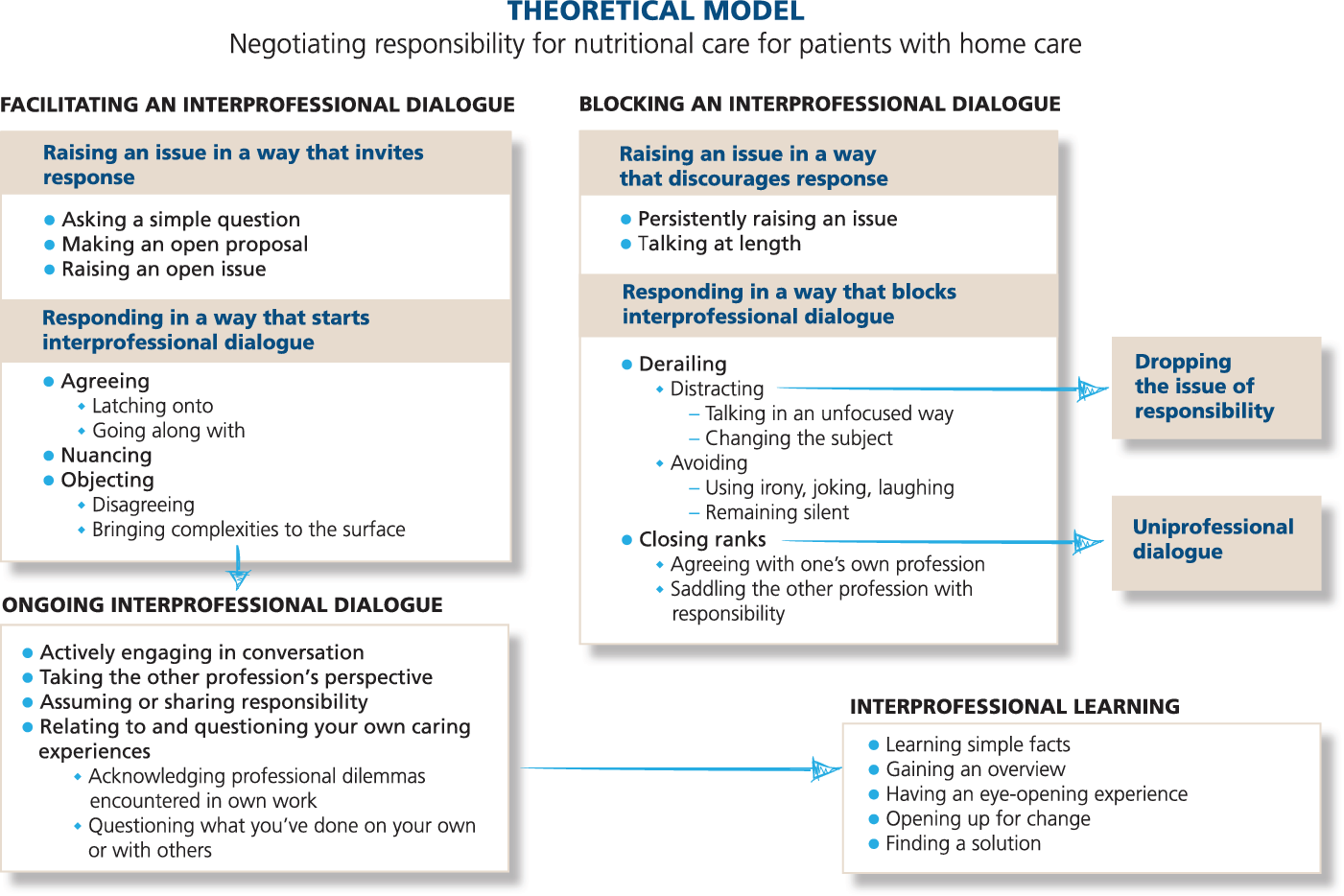

The substantive grounded theory is illustrated in a tentative theoretical model of the social process, ‘Negotiation of responsibility for nutritional care for patients with home care’. The model contains four main categories and their subcategories: ‘Facilitating an interprofessional dialogue about nutritional care’, ‘Blocking an interprofessional dialogue about nutritional care’, ‘Ongoing interprofessional dialogue about nutritional care’ and ‘Interprofessional learning about nutritional care’. In the result section, first- and second-order categories and third-order categories of substantial importance are written in italics. Categories are illustrated with quotes from the transcripts. For clarity, and when no difference in meaning was detected, repetitions and mumbling have been eliminated from the quotes.

Results

Professionals’ main concern about nutritional care for patients in a palliative phase of disease cared for at home was how to share and/or divide responsibility between DNs and GPs. Our substantive grounded theory, described in a theoretical model, illuminates the social process of negotiating responsibility for nutritional care for patients in palliative phases of disease cared for at home (Figure 1). The participants tried to solve their main concern through negotiation of responsibility for nutritional care in an ongoing interprofessional dialogue. The grounded theory delineates factors that facilitate interprofessional dialogue and lead to interprofessional learning or block such dialogue and learning. Our result suggests that IPE may lead to interprofessional learning about nutritional care if physicians and nurses engage in an ongoing interprofessional dialogue about the subject. Such dialogue is characterised by active involvement, taking the other profession’s perspective and assuming or sharing responsibility.

Figure 1. The theoretical model that delineates factors that facilitate interprofessional dialogue and lead to interprofessional learning, or block such dialogue and learning.

One central issue was whether DNs are responsible for providing information about nutritional status to GPs or GPs are responsible for asking DNs for information. Negotiation of responsibility centred on the way DNs and GPs conveyed information to each other about patients’ nutritional status.

DN: It’s clear that the responsibility lies with the physician, too … GP: To inform oneself. DN: Inform oneself about how it really is. And that you do a little follow-up. Instead of ‘If I haven’t heard anything, then it’s probably fine’, ‘How is Kalle doing now?’ or Aina, or whoever it is. How are they doing?

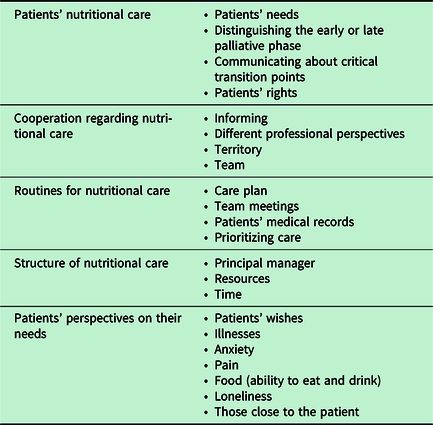

DNs differed in their opinions about how much responsibility they should take for involving GPs in patients’ nutritional care. Some DNs thought they (DNs) carried too heavy a responsibility, whereas others thought it was their job to shoulder heavy responsibility in relation to patients living at home. DNs also differed about whether they should smooth the way for the GPs, for example, by changing the bookings in a GP’s calendar to facilitate home visits. The content of the negotiation, that is, the caring issues DNs and GPs focused on during the case seminars, is provided in Table 1.

Table 1. Caring issues in the case-seminar discussions

The social process and its content and variations are described below. This section first presents the two main conceptual categories, the ongoing interprofessional dialogue about nutritional care and interprofessional learning about nutritional care, including their subcategories. Thereafter, the theoretical codes facilitating an interprofessional dialogue and blocking an interprofessional dialogue are presented with their subcategories.

An ongoing interprofessional dialogue about nutritional care

Early in the coding process, we identified ongoing interprofessional dialogue. We also identified uniprofessional dialogue in which DNs and GPs interacted only with other members of their own profession even though they were supposed to discuss the case interprofessionally. In the ongoing interprofessional dialogue, DNs and GPs negotiated responsibility for nutritional care. Both DNs and GPs were actively engaged in the conversation and could take the other profession’s perspective. In the example below, members of both professions engaged in a discussion about why they sometimes avoided talking about responsibility for a patient’s care.

GP: We believe that sometimes you’re so afraid of stepping on the other’s, afraid that the other person will take it as criticism. [Mumbles of agreement.] GP: That one’s so worried about that. DN: Tiptoeing into the other’s territory. GP: Yes, that it becomes some kind of questioning rather than collaboration.

Taking the other profession’s perspective is an aspect of the ongoing interprofessional dialogue in which the DN and GP listen to and learn from each other’s different perspectives. For example, DNs empathised with how difficult it must be for GPs to rely on second-hand information from DNs or to make decisions alone. One DN said, ‘We have the same patients, but physicians don’t. They’re all alone, left to make their own decisions, and have to rely on the DN.’

Assuming and sharing responsibility. Both professions assumed responsibility by defining their own professional responsibilities for nutritional care. However, they also acknowledged that nutritional care is their joint responsibility and that the lines between professional domains are difficult to draw.

GP: In this case, it was originally a nursing care problem, but it has absolutely led to it becoming a medical problem. There you can’t say that it’s the responsibility of the one or the other.

GPs also said that they could not take their medical responsibility for the patient’s nutritional care without knowing how the DNs carried out their caring responsibilities. Additionally, GPs suggested that exchanging ideas with DNs and providing them with medical explanations for patients’ symptoms might help lift responsibility from the DNs’ shoulders.

Relating to and questioning one’s own caring experience. Relating what was being discussed to one’s own experience and questioning that experience was part of the ongoing interprofessional dialogue. Such relating and questioning could enable a change, as in the case of one DN who reflected about the lack of structured time for meetings with GPs at her health centre.

DN: Our homecare meetings are, like, when we try to drink coffee. Then it’s like we always grab you on the run. It’s not like we have meetings with each other.

Both professions referred to their own patients when they discussed patients’ right to die at home. This in turn led to acknowledging several professional dilemmas, such as uncertainty about patients’ wishes and care needs and balancing the two. For example, it could be difficult to know whether patients were in an early or late palliative phase of disease and to understand reasons for difficulty with eating.

DN: And then this about the patients’ problems, that you really sort it out. Because it’s exactly this practical [concern] that that she might not be able to hold utensils. Is it because she doesn’t have any appetite, that she doesn’t feel the desire to eat, that she doesn’t want to eat, that the food isn’t good, that she doesn’t have any company? There’s so much that influences.

Dilemmas also included how to handle family who wanted the patient to be treated in a hospital when the patient wanted to die at home.

GP: I have some old ladies and they don’t want to take any medicine. Then their children call: ‘Why don’t you do anything? Why don’t you do anything?’ I can’t take their side. I have to listen to the patient, if she’s sane and lucid, that’s why. [Murmurs of agreement.] GP: But then you don’t know how nice little Aina is. Perhaps she doesn’t want to tell her children that she wants to … GP: … wants to die.

The professionals questioned the care procedures at their own workplace, including what they did on their own or with others. For example, some GPs were critical of themselves for forgetting or not prioritising team meetings to discuss nutritional care for patients with home care. GPs could also recognise that patients with home care did not get the same attention from them as patients who came to the health care centre. One GP noted that at the centre where he worked, GPs had to rely on DNs regarding patients in home care, and he felt guilty for not being more active:

GP: We’re so used to the patients coming to us all the time. That’s how we live. That’s how we think. We have a hard time with these patients who are on the periphery, who we’re actually responsible for but where there’s always a go-between.

Learning from the interprofessional dialogue

We identified five types of interprofessional learning about nutritional care following DNs’ and GPs’ interprofessional dialogues: learning simple facts, gaining an overview, having an eye-opening experience, opening up for change and finding a solution, which are illustrated below.

Learning simple facts. Simple questions typically led to simple, factual responses. For instance, one GP asked a DN what responsibility home help service personnel have for patients who are not eating. The DN explained that home help service personnel are responsible for reporting such issues to the DN, such as if a patient ‘throws her lunch in the trash seven days a week’. Learning a simple fact could also be the result of someone objecting to a statement.

DN: We’re supposed to switch to Take Care [electronic patient record system] now, and we have a symbol for home health care patients in our patient records now … GP: Not in Take Care. DN: Yes, it says ‘home health care’, but you can change it to its own little box instead, on the first page, overview, that’s what you can do. GP: Oh.

Gaining an overview. After a long ongoing interprofessional dialogue, one person could offer a summary overview of the issue being discussed, showing that he or she had taken in the dialogue and learned from it. For example, interprofessional learning could be seen when a GP summarised what DNs had said:

GP: I think we, well I’ve thought about my situation, when I’ve like talked with the patient about nutrition, then I think like: I should maybe be a little more detailed, like a little more, question a little more thoroughly. Ask like how the person is eating. ‘Yes, we eat well.’ And like what’s ‘well’? How does the person eat breakfast, do they eat lunch, do they eat three times, do they eat between-meal snacks? It’s really important to find out these things. [But] maybe you don’t do this with all patients.

Having an eye-opening experience. Excerpts were coded as an eye-opening experience when DNs and GPs used wording such as ‘thinking differently’, ‘opened my eyes’, ‘an eye-opener’ and ‘thought provoking’.

DN: I’m thinking in a different way now, have another view of the patient. And how easy it is to forget or not see signs of undernourishment, signs of such things. Opened my eyes to the use of a scale in home care.

Opening up for change means preparedness to change caring actions, typically as a result of relating the issues being discussed to your own caring experience. For example, one GP stated that he would work to change the fact that GPs did not prioritise patients with multiple diseases. Another GP said that they would start having monthly team meetings about patients with home care again and that someone should go through patient records to provide the information needed for the meetings. A DN reflected, ‘Well, I’m thinking that I should write care plans for my patients, or I think that it’s necessary. I feel like we could do so much more than what we …’

Finding a solution. Reflection during the ongoing interprofessional dialogue might lead to a solution worth trying. Such was the case when professionals from one health care centre discussed how to organise meetings about patients with home care, which GPs found too time-consuming.

DN: But, that’s actually something we could discuss – how to solve it. GP: Yes. DN: In a good way. GP: Yes – DN: But we could look at it … and what says we have to have it once a week, if it should be done like all the time. Maybe it can be once a month. It’s something we have to check, what it’s possible to do.

Facilitating an interprofessional dialogue

Interprofessional dialogue could be facilitated or blocked depending on how an issue was raised and how it was responded to.

Raising an issue in a way that invites response. The issue was raised in an open way by asking a simple question, making an open proposal or raising an open issue. Asking a simple question means that the questioner is admitting his or her ignorance and expects a response. The members of the other profession easily responded to some questions, for example, whether or not dieticians conduct home visits. However, simple questions could also have complex answers, such as when a GP brought up a question of responsibility in case of suspected neglect of an undernourished patient. Open proposals and open issues easily led to responses from the other profession.

DN: Morphine … right, it disappeared. GP: I mean, that’s really serious. GP: Exactly, you would think that the GP should know, should be informed.

Responding in a way that starts an interprofessional dialogue means agreeing, nuancing or objecting to the issue of responsibility that was raised. DNs and GPs agreed with one another by going along with or latching onto what other had said:

DN: But we plan health care. DN: Yes. That’s really good. DN: We collaborate too. GP: We do that, too … teamwork.

They nuanced issues by discussing pros and cons or downplaying comments. For example, when a DN emphasised care continuity, another DN responded by seeing pros and cons, and then a GP got involved, starting an interprofessional dialogue. Professionals could also respond by objecting to the issue in a way that led to an ongoing interprofessional dialogue by disagreeing or bringing complexities to the surface. One group discussed what GPs should do when they suspect a patient is undernourished and the DN is not involved. They disagreed with each other in such a way that the discussion about responsibility became more complex.

GP: Well you can’t even send a nurse home to check how they’re eating. GP: So I don’t agree. GP: Wasn’t it like that? GP: Everyone who needs medical and nursing care has to get it, whether it’s home care or it’s individual visits at home. There’s nothing that says that nurses can’t go home and do a nutritional assessment of a patient who isn’t [in] home care. DN: And that’s one thing. But we don’t do any check-up visits. GP: No, but …

The discussion became very intense and continued with reflections about how to draw a line between medical care, nursing care and home help services.

Blocking the interprofessional dialogue

When the interprofessional dialogue was blocked, the issue of responsibility for nutritional care was dropped. The interprofessional dialogue stopped before it started or the dialogue was limited to a uniprofessional dialogue. Several rather long uniprofessional dialogues resulted from such blocking. The issue of responsibility could be vividly discussed in these dialogues, but only by the members of one profession. This is illustrated in the quote below.

DN: Yes, early when it maybe starts, it’s when a person starts to decline, their appetite starts to go down, and they don’t have the energy to sit up and eat for as long … in other words, yeah. DN: Then oral nutritional supplements are useful. DN: Yes, or supplementation. DN: When supplements can be useful, yes by giving them extra cream and all that, and possibly nutritional supplements, but just that … DN: And then that you can see that the dining situation can like be improved. DN: Then the person can make use of it … then the body can make use of the nourishment. But then in the late palliative phase, then it’s like too late. Then the body can’t take care of it. DN: No, maybe they have trouble swallowing already so bad that they can’t manage to eat so much, and they refuse to accept, and now it’s oral health care, and yes … that’s the extreme here. DN: Yes, yeah.

Raising an issue in a way that discourages a response occurred when one profession persistently raised an issue or talked at length, such as when DNs persistently took up the issue of teamwork or meetings about the nutritional needs of patients in home care. Other DNs could latch on and agree, but the GPs tended not to respond, in contrast to when the issue was taken up in an open way. Such was also the case when a member of one profession talked at length. One GP, for example, talked at length and in general terms about planning and taking measures to ensure quality, and no one responded to the long monologue.

Responding in a way that blocks interprofessional dialogue happened via derailing or closing ranks. The interprofessional dialogue derailed when the speaker distracted other participants or avoided the issue of responsibility for nutritional care. A professional could distract others from the discussion by changing the subject or talking in an unfocused way. The professionals could avoid the issue of responsibility by making an ironic comment, joking or laughing. For instance, one DN tried to talk about the lack of collaboration about nutritional care with GPs but was met with a joke, which ended the conversation. Another instance occurred when a DN talked about wanting to save GPs’ time and not disturb them unnecessarily.

DN: You can’t run and bother the GP again and again. That just isn’t possible. The GP has to have peace and quiet to work, otherwise they’ll be stressed and nervous. You can only bring up what the GP can do. DN: So it should be something that the physician can do. And what does the physician do? Prescribes medicine. The rest is the nurse [laughs].

A GP later responded with an ironic comment that temporarily derailed the interprofessional dialogue: ‘It took a long time to learn to prescribe medicine. There were eleven semesters of it [laughs]. Long education for learning to write prescriptions!’

An issue could also be avoided by referring to lack of time: then there was nothing left to say. For example, a GP stated that joint home visits involving both professions were a helpful way to improve nutritional care for patients living at home, but there was no time for such visits.

Another way of blocking the interprofessional dialogue was by closing ranks. When the members of a profession closed ranks, they talked in a way that made it difficult for the other profession to join the discussion. They agreed with the members of their own profession or tried to saddle the other profession with the responsibility. Particularly when professionals agreed with an issue persistently raised by members of their own profession, interprofessional dialogue was blocked. In the excerpt below, DNs persisted in their opinion that their responsibilities for nutritional care are too heavy. The dialogue ended when a GP distracted the group by changing the subject:

DN: No, the GP has completely saddled the DN with the responsibility. DN: And we actually have different competencies. DN: That’s a little wrong. DN: It’s very wrong. DN: We see what we know, but we can’t see what …. GP: We have another problem. We’ve collaborated for so long that we’re blind to flaws.

Sometimes members of one profession tried to saddle the other profession with the responsibility for some aspect of nutritional care. After comments like, ‘The GP should be more involved!’ the discussion often ended, or if it continued, did so in the form of uniprofessional dialogue. This was also the case when a GP tried to saddle DNs with responsibility:

GP: But as a physician I can think that it’s the nurse’s responsibility to tell me about the problem, and then she can convey it to me somehow. It’s not my primary responsibility to discover it, because I’m not there, huh?

Negotiating responsibility for nutritional care as a game

When DNs and GPs were involved in an ongoing interprofessional dialogue, they played as a team and scored (achieved learning goals). The issue they took up was like a ball thrown onto the court in a way that made it easy to grab and pass on to the other players. However, if they threw the ball onto the court in a way that made it difficult to catch, the players could end up in separate teams. They would then close ranks and only toss the ball to the players on their own team, or the ball would roll off the court and play would cease.

Discussion

We set out to explore DNs and GPs’ interaction in a case seminar when they discussed nutritional care for patients in palliative phases cared for at home and to construct a theoretical model illuminating the professionals’ main concern. Their main concern was how DNs and GPs should share and/or divide responsibility for nutritional care. They tried to resolve this concern by negotiating responsibility. When this negotiation took the form of an ongoing interprofessional dialogue, the outcome was interprofessional learning about nutritional care. The ongoing interprofessional dialogue about nutritional care started if someone asked a simple question, made an open proposal or raised an open issue. These openings led to agreeing, nuancing or objecting, and in the end, to interprofessional learning.

Previously, collaboration between nurses and physicians has been described both as a game (Stein, Reference Stein1967) and as negotiation (Strauss, Reference Strauss1978). In Leonard Stein’s doctor–nurse game model, the objective of the game was to enable nurses to make care recommendations to physicians, but in a way that made it seem like the physicians had initiated the recommendations.

Although we used the metaphor of a ball game to describe the discussion between DNs and GPs in our study, our analogy differs in important ways from Stein’s. In Stein’s model, the main rule was that disagreement must be avoided (Stein, Reference Stein1967), whereas we found that disagreement could lead to greater understanding and learning. This was particularly true when groups of DNs or GPs were not in total internal agreement, because members of the other profession could more easily join the discussion. Interaction between groups was thus facilitated by within-group diversity, which is in accord with social identity and self-categorisation theory (Tajfel & Turner, Reference Tajfel and Turner1986).

In further contrast to the doctor–nurse game model, in which manipulation is employed as a strategy, we found that negotiation proceeded smoothly when issues were brought up in an open way. Both DNs and GPs showed mutual professional respect through active involvement, taking the other profession’s perspective and assuming or sharing responsibility.

As a result of modifications in power relationships and ‘growing disillusionment with the traditional rational-bureaucratic model of organisations’ (Allen, Reference Allen1997), Anselm Strauss’s negotiated order approach (Strauss, Reference Strauss1978) gained ascendency over the game model for describing nurse–physician collaboration (Svensson, Reference Svensson1996). Stein himself agreed that the game model was outdated because of radical change in doctor–nurse relationship (Stein et al., Reference Stein, Watts and Howell1990). Strauss proposed that all social orders are negotiated. Actors make decisions about how work should be organised and accomplished by negotiating who does what, when, where and how. Although organisations have structure, there is uncertainty and room for negotiation in every organisation, including primary health care.

DNs and GPs in our study tried to achieve a negotiated order. When an issue was raised and responded to in an open way, they smoothly negotiated the issues of responsibility in an ongoing interprofessional dialogue. This finding echoes the results of an interview study with nurses from 14 Swedish wards (Svensson, Reference Svensson1996). Those nurses described a rule system, permissive about presenting opinions and questioning, even in the medical area, which led the author to conclude that a negotiated order perspective was appropriate for understanding the interaction between nurses and physicians.

In our study, one negotiated issue was how much responsibility GPs had for staying informed about patients’ nutritional status. GPs relied on DNs for information. DNs wanted GPs to take more responsibility for keeping track of patients’ status and preferred to communicate in formal meetings or sitting rounds. When DNs took this issue up in an open way, GPs nuanced, agreed or objected, and negotiation could continue until resolution was reached. A previous Swedish study (Modin et al., Reference Modin, Törnkvist, Furhoff and Hylander2010) also focused on the dilemma GPs faced in relying on DNs for information about patients in home care. In situations when GPs relied on DNs to inform them, but DNs expected them to gather information on their own, care was not good enough. The current study adds information on how DNs and GPs can avoid misunderstandings about role expectations by negotiating responsibility in an ongoing interprofessional dialogue.

Another issue often raised and negotiated in the current study was how and in what forms the professionals should collaborate. Some DNs and GPs seemed more eager to raise the issue of collaboration than others. One possible explanation is different understandings of the concepts of ‘interprofessional’ and ‘collaboration’. Whereas ‘collaboration’ seems to mean closer, team-like interaction to some, others might have a looser form of interaction in mind (Reeves et al., Reference Reeves, Xyrichis and Zwarenstein2018). Additionally, professionals can see the ‘interprofessional’ as a dimension of the professional or as an addition to the professional (Green, Reference Green2013). Those more eager to collaborate might see working interprofessionally as an integrated part of their profession.

Professionals also negotiated the issue of whether DNs should smooth the way for the GPs, for example, by changing the bookings in a GP’s calendar to facilitate home visits. In a combined interview and observation study with a negotiated order perspective, the researcher described a similar phenomenon (Allen, Reference Allen1997). In both studies, nurses felt frustrated but also sympathetic with the time pressures physicians faced.

We also found examples of non-negotiation. Despite the aim of IPE, uniprofessional dialogue still occupied a substantial part of the sessions. If an issue was raised in a way that discouraged response (such as persistently raising an issue or talking at length), interprofessional dialogue was blocked via either derailing or closing ranks. Closing ranks meant that the members of one profession agreed only with each other and/or saddled the members of the other profession with responsibility. In other words, they engaged in in- and out-group thinking (Tajfel & Turner, Reference Tajfel and Turner1986; Thistlethwaite, Reference Thistlethwaite2012a). Other researchers have described a non-negotiated order (Reference AllenAllen, 1997; Reeves et al., Reference Reeves, Rice, Conn, Miller, Kenaszchuk and Zwarenstein2009). In one study, interview data indicated that nurses wanted to collaborate to achieve negotiated order (Allen, Reference Allen1997). Field observations did not confirm this finding but instead showed a non-negotiated informal blurring of professional boundaries in nursing practice that everyone took for granted (Allen, Reference Allen1997). An observational study found that interaction between physicians and other health care professionals consisted of non-negotiation and unidirectional comments, whereas interaction between nurses and other health care professionals consisted of interprofessional negotiations (Reeves et al., Reference Reeves, Rice, Conn, Miller, Kenaszchuk and Zwarenstein2009).

In our study, we observed that the process of negotiation led to learning in situ in the specific field of nutritional care. Observations of collaborative workplace learning in continuing education are relatively rare (Thistlethwaiate, Reference Thistlethwaite2012a). The different aspects of interprofessional learning detectable in the interaction in the present study have similarities to levels of learning in the Structure of the Observed Learning Outcome (SOLO) taxonomy (Biggs and Tang, Reference Biggs and Tang2011), which is recommended for use in continuing education (Biggs & Tang, Reference Biggs and Tang2011; Nordquist et al., Reference Nordquist, Sundberg and Johansson2011). The SOLO taxonomy has a hierarchical structure that progresses from increasing learners’ knowledge (prestructural, unistructural, multistructural) to deepening their understanding (relational, extended abstract) (Hattie, Reference Hattie2011). We identified learning at different levels in this taxonomy, up to and including the extended abstract level. However, two of the subcategories that describe learning, ‘opening up for change’ and ‘having an eye-opening experience’, take place on various cognitive levels and have clear emotional connotations. As such, they are difficult to categorise in accordance with the SOLO taxonomy, which covers the cognitive and action oriented but not emotional components that characterise people’s attitudes (Brown, Reference Brown2006). Still, these concepts are crucial for changing attitudes towards collaboration and mutual caring actions. There is less evidence for attitudinal change than for cognitive improvements following an IPE intervention (Hammick et al., Reference Hammick, Freeth, Koppel, Reeves and Barr2007; Thistlethwaite, Reference Thistlethwaite2012a). This suggests that further explorations of ‘opening up for change’ and ‘having an eye-opening experience’ (specifically, when, where and why they occur) may contribute to our understanding of broad changes related to interprofessional interventions to stimulate collaboration between DNs and GPs.

Methodological considerations

Like all grounded theories, the substantive theory should only be seen as a set of proposals that need to be grounded in wider data. The theory is well grounded in the specific situation of the case seminar and may only be transferrable to similar contexts after it is grounded there. One limitation of the study is that we did not use strict theoretical sampling. However, we conducted a flexible, stepwise analysis of the seminars until we judged saturation was reached.

Conclusions

This study contributes a substantive grounded theory about DNs and GPs’ negotiation of responsibility for nutritional care for patients in palliative phases of disease cared for at home. The theory, described in a theoretical model, delineates factors that facilitate interprofessional dialogue and lead to interprofessional learning or block such dialogue and learning. Thus, our grounded theory is consisted with the negotiated order approach.

Our findings suggest that facilitators should watch for and guide participants away from factors that can turn interprofessional dialogue uniprofessional, such as persistently raising an issue and talking at length. They also suggest aspects of learning that were directly generated from the interaction between DNs and GPs in case seminar discussions, including interactional aspects of learning that have emotional connotations. The theoretical model can be used to improve continuing IPE, teamwork and collaboration in caring, either by teachers who wish to facilitate interprofessional dialog and learning or by group members as a tool to promote reflection.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the district nurses and GPs who participated in the educational intervention, GP Hanna Sandelowsky for her role in facilitating the case seminar discussions and Scientific Editor Kimberly Kane for useful comments on the text.

Financial support

Partly funded by the Regional Agreement on Medical Training and Clinical Research (ALF, 20140347).

Conflict of interest

None.

Ethical standards

The Regional Ethical Review Board in Stockholm, Sweden, approved the study (dnr.2011/1198-31/2). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.