Introduction

Young-onset dementia (YOD) is defined as the onset of dementia symptoms before the age of 65 years.1 In Canada, YOD accounts for 2–8% of dementia cases which equates to an estimated 16,000 Canadians under the age of 65 years currently living with dementia.1

Although Alzheimer’s disease is the most prevalent dementia overall in YOD, Alzheimer’s dementia and dementia with Lewy bodies are proportionally more common in late-onset dementia (LOD), while frontotemporal dementia tends to be more common in YOD.Reference Draper and Withall2 Secondary dementias such as those caused by infection, chronic alcohol abuse, HIV, multiple sclerosis and neoplasms are more common in YOD patients, and some are treatable if interventions are started early.Reference Draper and Withall2

There is significant financial and social burden in families affected by YOD. Patients diagnosed with YOD face unique challenges. The diagnosis of YOD is often unexpected, resulting in a strain on relationships, the questioning of self-identity, social exclusion and feelings of powerlessness.Reference Greenwood and Smith3 Friends and family are less likely to understand the diagnosis of YOD compared to LOD, which can result in social isolation.Reference Greenwood and Smith3 Although all dementia patients are more likely to experience apathyReference Appelhof, Bakker and Van Duinen-van Den IJssela4 and depression, these feelings are more common among YOD patients.Reference Leontjevas, van Hooren, Waterink and Mulders5 YOD may also cause financial impacts, early retirement and a high degree of burden on their caregivers and children.Reference Draper and Withall2,Reference Millenaar, de Vugt and Bakker6,Reference Gelman and Rhames7 In YOD, symptoms are often noticed first in the workplace and when these symptoms interfere with work, YOD patients often experience job loss, which can lead to loss of self-identity, autonomy and purpose.Reference Roach and Drummond8 As a consequence of job loss, YOD patients have unmet needs in daytime activities and social company.Reference Greenwood and Smith3,Reference Bakker, de Vugt and van Vliet9 Patients with YOD often stop driving,Reference Velayudhan, Baillon and Urbaskova10 which further results in the loss of freedom and independence.

Spouses of YOD patients encounter higher levels of burden and feelings of depression as caregivers because of increased loneliness, lack of intimacy, assumed responsibility of children, changes in their marital relationship and family conflict.Reference Millenaar, de Vugt and Bakker6,Reference van Vliet, de Vugt, Bakker, Koopmans and Verhey11,Reference Holdsworth and McCabe12 Some spouses may feel socially isolated and excluded, especially since YOD is relatively uncommon.Reference O’Connell, Crossley and Morgan13 Thus, spouses have a greater need to interact with other people.Reference Wawrziczny, Pasquier, Ducharme, Kergoat and Antoine14 Caregivers often experience grief, loss and denial, and many find it difficult to plan for the future.Reference Durcharme, Kergoat, Antoine, Pasquier and Coulombe15 Spouses often work fewer hours to care for the patient, which can result in financial difficulties and the lack of a meaningful occupation.Reference van Vliet, de Vugt, Bakker, Koopmans and Verhey11 As the severity of dementia increases, the spouse often assumes greater responsibility for any dependent children living at home,Reference Gelman and Rhames7 and many find it difficult to juggle these additional responsibilities.Reference Durcharme, Kergoat, Antoine, Pasquier and Coulombe15 Children of YOD patients may gradually take the role of a caregiver instead of themselves receiving parental care.Reference Millenaar, van Vliet and Bakker16

The province of Saskatchewan in Western Canada has 1.1 million residents and 35.6% of its population resides in rural regions.17 Currently, an estimated 19,000 Saskatchewan residents are living with dementia.18 With the large number of rural residents and the growing number of dementia patients, the Rural and Remote Memory Clinic (RRMC) was created in 2004 to increase the accessibility and availability of specialist diagnosis to patients with complex and atypical dementias in rural Saskatchewan.Reference Morgan, Crossley and Kirk19 The RRMC is a one-stop clinic and consists of an interdisciplinary team including a neurologist, neuropsychology team, physical therapist, dietician, and nurse for the streamlined assessment and management of suspected dementia cases.Reference Morgan, Crossley and Kirk19,Reference Verity, Kirk, O’Connell, Karunanayake and Morgan20 Each new patient receives a standard diagnostic examination that consists of bloodwork, a non-contrast CT scan, multiple neuropsychological tests and additional investigations as indicated.Reference Verity, Kirk, O’Connell, Karunanayake and Morgan20 Using this approach, the time to diagnosis is shortened, with the goal of a diagnosis, treatment recommendation and counselling by the end of the 1-day visit. Each patient with a diagnosis will have a follow-up session with the memory clinic at 6 weeks, 12 weeks and then every 6 months thereafter, and more often as required.Reference Morgan, Crossley and Kirk19 Through the use of telehealth videoconferencing, the time and cost of long-distance travel for patients and caregivers to and from the Memory Clinic for follow-up visits are reduced,Reference Morgan, Crossley and Kirk19 and telehealth has been used for a spousal support group for persons with YOD.Reference O’Connell, Crossley and Morgan13 More information on the RRMC can be found in earlier publications.Reference O’Connell, Crossley and Morgan13,Reference Morgan, Crossley and Kirk19–Reference Hager, Kirk, Morgan, Karunanayake and O’Connell23

Due to the unique challenges that younger patients with dementia face, we aimed to study the differences between young patients (<65 years) and older patients (≥65 years) referred to the RRMC in Saskatchewan. The findings from our study will provide information on how to better understand this younger subset of rural dementia patients for improved care and management.

Methods

Informed consent was obtained from patients and their caregivers before participation and approved by the University of Saskatchewan Behavioural Ethics Research Board.

Participants

A total of 544 consecutive patients were seen at the RRMC between March 2004 and July 2016. All patients and their caregivers were given a questionnaire on clinic day. Patients who did not complete all assessments (n = 36), did not fill out questionnaires/forms (n = 61), who were diagnosed as normal/“worried well” (n = 105), or who did not receive a diagnosis on clinic day (n = 9) were excluded from this study. The total number of patients eligible for this study was 333. Patients who were less than 65 years old at the time of diagnosis were considered YOD patients (n = 61) and patients who were 65 years or older at the time of diagnosis were considered LOD patients (n = 272). As the age of onset of dementia symptoms can be difficult to estimate, we used age at diagnosis to determine the two groups.

Data

At the clinic, each patient was given a standard battery, which encompassed areas in learning and memory, attention and executive function, visuoperceptual and constructional skills, premorbid intellectual ability, and language.Reference Morgan, Crossley and Kirk19 A list of detailed components can be found in earlier publications.Reference Morgan, Crossley and Kirk19 The Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) was obtained on clinic day as part of a more comprehensive neuropsychological assessment (data not reported here due to known differences in neuropsychological profiles based on different dementia aetiologies, some of which are more likely to be YOD) and additional data were obtained by self-report through questionnaires. The questionnaire given to patients included measures of mood, functional ability, symptoms, memory, health, employment, education, behaviours and quality of life. Caregivers were given a questionnaire on measures of caregiver burden, health, and distress and measures of the patient’s functional abilities and behaviours.

A number of validated scales were used in the questionnaires to evaluate the severity and burden of symptoms on the patient and their caregiver. These scales were used based on previous literature and included: Mini-Mental State Examination,Reference Folstein, Folstein and McHugh24,Reference McEachern, Kirk, Morgan, Crossley and Henry25 Depressed Mood Scale,Reference Radloff26 Functional Assessment Questionnaire,Reference Pfeffer, Kurosaki, Harrah, Chance and Filos27 Brief Symptom Inventory,Reference Derogatis and Melisaratos28 Quality of Life Questionnaire,Reference Logsdon, Gibbons, McCurry and Teri29 Bristol Activities of Daily Living Scale,Reference Bucks, Ashworth, Wilcock and Siegfried30 Self-Rating of Memory Scale,Reference Squire and Zouzounis31 Zarit Burden Scale,Reference Zarit, Orr and Zarit32,Reference O’Rourke and Tuokko33 Neuropsychiatric Inventory-Severity ScaleReference Cummings34 and Short-Form Health Survey.Reference Ware, Kosinski, Turner-Bowker and Gandek35–37

Analysis

A descriptive analysis for the variables was conducted on the two groups. Measures of central tendency and variability were used for continuous variables, while frequency was used for categorical variables. Independent sample t-tests were used to compare continuous variables and χ 2 tests were used to compare categorical variables between the groups. Exact p-values were used when the χ 2 test was invalid due to small expected values. Variables with a p-value ≤0.05 were considered significant. The data were analysed using IBM SPSS version 24.38

Results

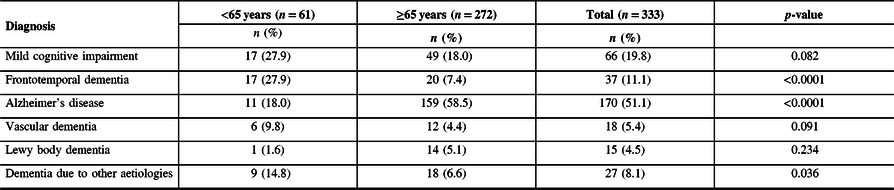

A total of 333 participants were included in this study. The median age of YOD patients (<65 years, n = 61) was 59 years and ranged between 44 and 64 years of age. The median age of LOD patients (≥65 years, n = 272) was 77 years and ranged between 65 and 94 years of age. The diagnoses made at initial assessment are reported in Table 1. Frontotemporal dementia was diagnosed more frequently among YOD, while Alzheimer’s disease was more common in LOD patients (p < 0.001).

Table 1: Diagnosis of older (≥65 years) and younger (<65 years) patients in the Rural and Remote Memory Clinic (n = 333)

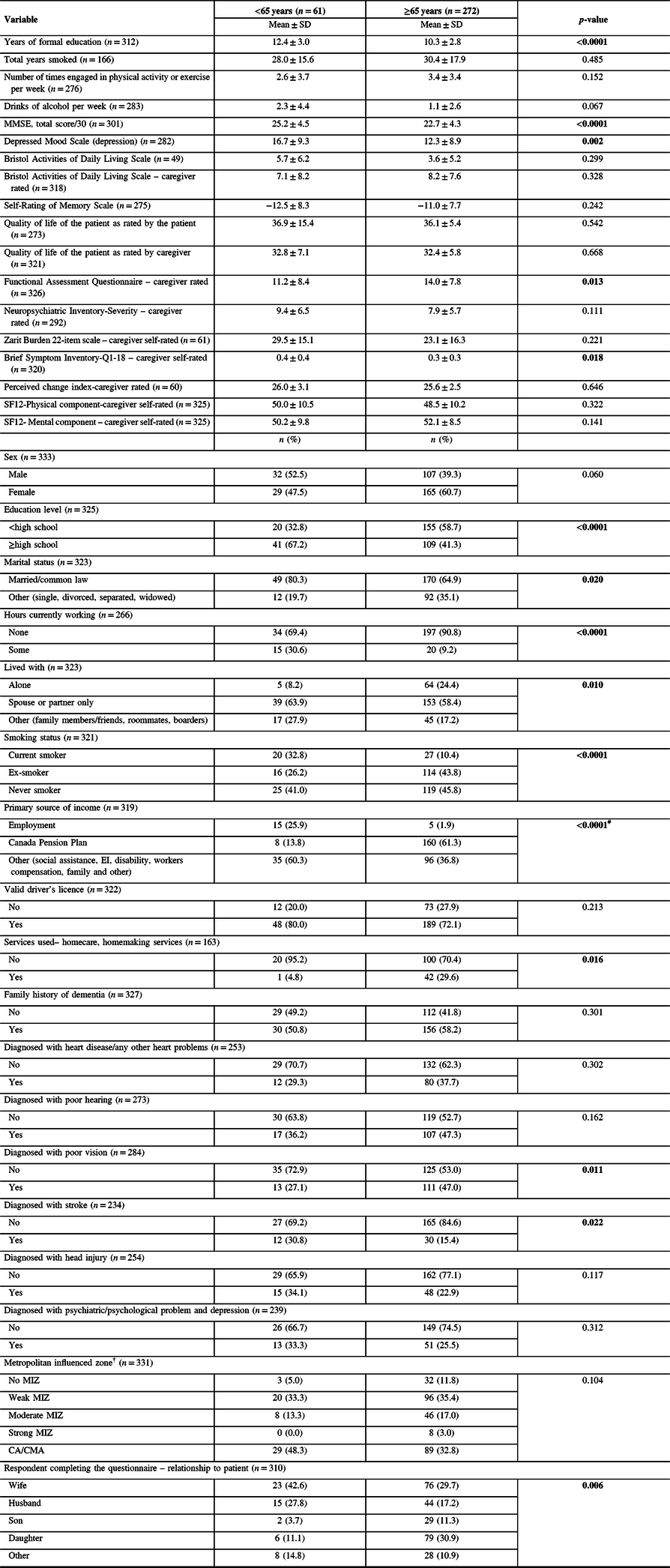

The characteristics of YOD and LOD patients are reported in Table 2. YOD patients were more likely to be currently married or in a common-law relationship (p = 0.020) and have their spouse attend the clinic as a caregiver (p = 0.006). They were also more likely to have a high school diploma (p < 0.0001), have completed more years of formal school (p < 0.0001) and be currently working (p < 0.0001). YOD patients were more likely to have their primary source of income from work (p < 0.0001), while LOD were more likely to receive their primary source of income from a Canadian pension plan (p < 0.0001). LOD patients were more likely to use homecare services (p = 0.016), live alone (p = 0.010) and be diagnosed with poor vision (p = 0.011). YOD patients were more likely to be current smokers (p < 0.0001), while LOD patients were more likely to be ex-smokers (p < 0.0001). YOD patients were more likely to have a previous diagnosis of stroke (p = 0.022), while other diagnoses such as a head injury, poor hearing, heart problems and a psychiatric/psychological problem or depression did not significantly differ between the two groups. Both were equally as likely to have a driver’s licence, and there was no significant difference in metropolitan influenced zone (MIZ), which categorises geographical areas according to the percentage of residents in the area who travel to an urban area for work. However, most of the participants resided in either a CA/CMA or an area with weak MIZ. There was no difference in having a family history of dementia.

Table 2: Characteristics of younger (<65 years) patients and older (≥65 years), n = 333*

Weak MIZ: <5% of the workforce commutes to a CA/CMA. Moderate MIZ: 5–29% of the workforce commutes to a CA/CMA. Strong MIZ: >30% of the workforce commutes to a CA/CMA. CA: population ≥ 10,000. CMA: population ≥ 100,000.39 EI: employment insurance.

Bold values indicate significance (p ≤ 0.05).

* All variables have missing values except age and sex.

# Due to small expected values, exact test p-value was reported.

† No MIZ: none of the workforce commutes to a CA/CMA.

YOD patients had significantly higher scores on the MMSE (p < 0.0001) and the Centre for Epidemiologic Studies - Depressed Mood Scale (p < 0.0001) indicating less cognitive impairment and more depressive symptoms. Caregivers of YOD scored higher on the Brief Symptom Inventory (p = 0.018), indicating higher levels of distress. YOD patients had a lower score on the Functional Assessment Questionnaire (p = 0.013), indicating less dependency as measured by the caregiver. There was no significant difference between YOD patients and LOD patients in the Bristol Activities of Daily Living Scale, Quality of Life scale (both patient and caregiver rated), Neuropsychiatric Inventory-Severity Scale, Self-Rating of Memory Scale, indicating that functionality, quality of life and symptoms experienced were similar between the two groups. Caregiver measures such as the Short-Form Health Survey and the Zarit Burden Scale were also similar between the two groups, indicating similar health and burden among caregivers.

Discussion

Although YOD accounts for only 2–8% of dementia cases in Canada,1 it accounted for 18.3% of cases in our study through the RRMC. This is not surprising as YOD tends to be more complex to diagnose, and the RRMC was created to provide specialist assessment of complex and atypical cases of dementia. Furthermore, the Canadian Consensus Conference on Diagnosis and Treatment of Dementia guidelines recommend that all YOD patients be seen in specialty clinics.Reference Moore, Patterson, Lee, Vedel and Bergman40 This subset of dementia patients is often working, married and have young children, making a diagnosis challenging and distressing. YOD patients and their caregivers have distinctly different characteristics, circumstances and experiences from other dementia patients.

Health, Education and Employment

We found that YOD patients had similar health measures to LOD patients. There were no significant differences in any health-related measures, except that LOD patients were more likely to have poor vision. Both groups were equally likely to have been diagnosed with poor hearing. Hearing loss in adults is quite common. Approximately, 40% of adults aged 40–59 years have some form of hearing loss, while 78% of adults aged 60–79 years have hearing loss.41 It is important that hearing loss is managed appropriately, as it is a modifiable risk factor for dementia.Reference Livingston, Sommerlad and Orgeta42,Reference Kim, Lim, Kong and Choi43 Interestingly, YOD were twice as likely to have been diagnosed with stroke. This was possibly associated with the greater prevalence of vascular dementia and other secondary dementias in YOD patients. YOD patients were three times more likely to be current smokers, while LOD patients were more likely to be past smokers. Some of this difference in smoking can be attributed to age, as smoking is approximately twice as prevalent in younger adults than in those 65 years or older.44

YOD patients were significantly more likely to have a high school diploma and on average completed more years of formal education than LOD patients. YOD patients were more likely to be currently working than LOD patients, which is expected as the standard age of retirement is 65 years.45 Although YOD patients were more likely to be currently working, only one-third were working at the time of diagnosis and about a quarter had employment as a major source of income. This lack of employment in YOD patients may stem from dementia symptoms interfering with work.Reference Roach and Drummond8 In addition to loss of occupation, patients with YOD often cease driving after diagnosis.Reference Velayudhan, Baillon and Urbaskova10 Approximately, 80% of YOD patients had a driver’s licence, which is similar to LOD patients, despite LOD patients being almost twice as likely to have a diagnosis of poor vision. Although there was no difference in MIZ scores between YOD and LOD patients, the majority of participants in both groups resided in either larger centres (population ≥ 10,000) or rural areas with a weak MIZ where a small fraction of workers commute to larger centre. People who benefit from this service may be more likely to live in towns that may not offer such services or more remote areas that are less influenced by larger cities. This suggests a need of more accessible services in smaller and rural areas.

Cognition, Depression and Quality of Life

We found that YOD patients had significantly less cognitive impairment as measured by a screening test, which may be a factor in the higher proportion of YOD patients who could work. Although YOD patients in the current study were less cognitively impaired, there was no difference in severity of caregiver-reported dementia symptoms between YOD and LOD patients as measured by the Neuropsychiatric Inventory-Severity scale.

YOD patients in this study had higher levels of depression than LOD patients. Depression may be more prevalent in YOD patients due to the unexpected nature of YOD, which can cause a questioning of self-identity, and strain on relationships, especially when children are involved.Reference Draper and Withall2,Reference Greenwood and Smith3 Depression is associated with lower quality of life.Reference Sivertsen, Bjorklof, Engedel, Selbaek and Helvik46 We found that although YOD patients were more likely to experience depressive symptoms, the quality of life of patients was not significantly different between YOD patients and LOD patients.

Caregiver Distress and Burden

YOD patients were more likely to be currently married or in a common-law relationship and to have their spouse attend the clinic as a caregiver, due to death of spouses in the LOD group. Caregivers of YOD patients in our study scored significantly higher on the Brief Symptom Inventory scale indicating a higher level of caregiver general psychological distress. Despite increased caregiver psychological distress, caregiver burden did not differ between the two groups. Other studies have found that caregiver burden is higher in YOD patients.Reference van Vliet, de Vugt, Bakker, Koopmans and Verhey11,Reference Lim, Zhang and Lim47 Spouses of YOD patients tend to experience a high level of distress, stress, caregiver burden, depression and coping difficulties.Reference Millenaar, de Vugt and Bakker6,Reference van Vliet, de Vugt, Bakker, Koopmans and Verhey11,Reference Durcharme, Kergoat, Antoine, Pasquier and Coulombe15,Reference Lim, Zhang and Lim47 Increased caregiver psychological distress can be due to a variety of reasons. Spouses of YOD patients often assume additional responsibilities such as caring for children and the patient, becoming the breadwinner, and making important financial and social decisions.Reference Millenaar, de Vugt and Bakker6,Reference Gelman and Rhames7,Reference van Vliet, de Vugt, Bakker, Koopmans and Verhey11 YOD caregivers are more likely to experience greater levels of psychological suffering, especially with patient behavioural symptomsReference van Vliet, de Vugt, Bakker, Koopmans and Verhey11 and may benefit from caregiver support groups.Reference Goy, Kansagara and Freeman48

Our study found that YOD patients were more likely to live with their spouse. Living in the same home as a patient with dementia can cause caregivers to assume additional responsibilities they may not have undertaken if the patient lived alone and may cause distress for the caregiver as they watch their loved one deteriorate. Living with a caregiver may also decrease the perceived need to use homecare services. It has been found that the use of these services is associated with reduced depression in caregivers.Reference Rosness, Mjorud and Engedal49 In our study, YOD patients were six times less likely to access homecare services or homemaking services than LOD patients. YOD patients are less likely to access services for a variety of reasons, including barriers such as unaffordability, ineligibility, insecurity, lack of childcare and a lack of perceived need.Reference Cations, Withall and Horsfall50 Available services are frequently tailored for LOD patients and thus the lack of fit for YOD patients also proves a barrier,Reference Bakker, de Vugt, Vernooij-Dassen, van Vliet, Verhey and Koopmans51 and YOD patients and their caregivers may choose not to access care because of denial and refusal to seek help.Reference van Vliet, de Vugt and Bakker52 Accessing services for YOD may be especially important for YOD patients, as this population has a high mortality from complications due to dementia.Reference Tan, Fox, Kruger, Lynch, Shanagher and Timmons53

Limitations

Although the definition of YOD is the onset of dementia symptoms before the age of 65 years, we were only able to measure YOD as a diagnosis of dementia before the age of 65 years because age of onset is always a retrospective estimate prone to inaccuracy. Compared to national estimates, a much larger proportion of patients referred to the RRMC were YOD patients. The RRMC also serves rural patients who may differ from urban patients. Finally, having multiple comparisons in our data makes spurious findings more likely.

Conclusion

YOD patients are distinctly different from LOD patients. YOD patients are more educated, more likely to be working and are more likely to be married. Because of this, YOD patients experience unique challenges in receiving a diagnosis and are more likely to demonstrate depressive symptoms. Caregivers of YOD patients demonstrate higher levels of general psychological distress. Homecare services should be modified to better assist YOD patients and additional support is needed for their caregivers. More research is needed to better understand how to help YOD patients overcome barriers to services and how we can shape these services to better fit the needs of YOD patients and their families.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the Rural and Remote Memory Clinic at the University of Saskatchewan for support in this research.

Funding

This study was funded by the College of Medicine, University of Saskatchewan.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Statement of authorship

All authors contributed in the preparation and editing of the final manuscript. JFWW wrote the manuscript under the guidance of AK. AK and LP developed the study design and oversaw data collection. CK conducted the statistical analysis. DM managed data collection. MEOC administered and oversaw neuropsychological testing.