In the nineteenth century, after the banning of kindergartens in Germany in 1851 and the death of Friedrich Froebel (1782-1852), many women who had been trained by the education pioneer departed from Germany, sharing his theory across the world as they traveled. These known as Froebelians. As they disseminated Froebel's theory of education from Germany to other countries, Froebelians translated his kindergarten principles into different languages and adapted and altered Froebel's concepts as they developed kindergartens in new cultural contexts.

Scholars have developed several theories to explain such adaptations and alternations. Both Edward W. Said's “traveling theory” and Thomas S. Popkewitz's theory of the “traveling library” assert that all ideas travel from one place and time to another; however, during the process of indigenization and adaption, those ideas weaken or strengthen according to how they are translated in a particular country, society, culture, or period. This is known as “transformation theory”.Footnote 1 In the field of comparative education, Robert Cowen has developed a related theory, known as “transitology theory,” to explain how the metamorphosis or the process of “shape shifting” occurs. He says of the process: “As it moves, it morphs.”Footnote 2 In other words, if an educational theory transfers from one place or country to another, a translation or transformation of that theory is required. The dissemination, or shape-shifting, require both localization and the extinction of translated forms.Footnote 3 Froebel's theory is no exception to this. The education field in the past two decades has undertaken substantial international research on the transfer, translation, and transformation of Froebelian theories and pedagogies. In the process of indigenization that guided the development of kindergartens in Japan, Froebel's theory was transformed not only as a result of local and national pressures and the balance of political control, but also by the country's culture and history. Significantly, the translation and transformation of Froebel's theory were also deeply influenced by the personal beliefs of Froebelians and the values of early childhood education.Footnote 4

In the mid to late nineteenth century, many missionary women from Europe and North America arrived in Japan. They faithfully engaged in educational work and disseminated their faith while contributing to the establishment of the modern nation-state of Japan following the opening of the country to the West, in what is known as the Meiji Restoration of 1868. Missionary women played a large role in the field of education and were responsible for establishing various educational institutions.Footnote 5 They believed education to be one of the most powerful tools and services that they could offer as they disseminated Christianity in Japan. Missionary women pioneered education for young children and girls. In particular, these missionaries had a significant impact not only on the establishment of Christian kindergartens and kindergarten teacher training schools but also on the dissemination of Froebel's theory in Japan.

In the process of modernization during the Meiji period, a modern nation of civilization and enlightenment was constructed in the Japanese cultural and ideological landscape, a dramatic period of Westernization that brought about an almost wholesale rejection of Japanese traditional values. However, Japan never fully welcomed Christianity, and as a result, an inevitable backlash emerged in response to the dramatic social changes of this era. Though many Japanese leaders viewed Westernization as necessary for the formation of a new nation-state, a nationalistic reaction that sought to return Japan back to its traditional values had emerged by the time of the Meiji government. The Meiji government began to oppose the cultural aspects of Westernization and the Christian religion through state interventions to promote national unity and nationalism, which, in turn, influenced the field of education.Footnote 6

The Ministry of Education promoted nationalism by prohibiting the teaching of any religion except Shintoism, thus making it impossible for missionaries to teach students about Christianity in their Christian schools. To achieve this, the Ministry acknowledged that it was necessary not only to reinforce the public education system but also to control private schools, especially with regard to the missionaries’ Christian schools. By placing its emphasis on the sovereignty of the emperor, based on the doctrines of Shintoism, and promoting the traditional values of Confucianism, the government thus laid the foundation for several years of intense attacks on Christianity. During this period of political and religious turmoil, a number of missionary women faced various obstacles as they strove to keep their schools and kindergartens operational.Footnote 7

However, the missionaries’ kindergarten teacher training schools were exempt from this prohibition, because government policies applied only to the schools affected by the nation's the Fundamental Code of Education. The Fundamental Code of Education mandated that all students attend school up through the secondary level, but no such mandate existed for post-secondary education.Footnote 8 As a result, missionary women could continue to train kindergarten teachers and disseminate Christianity through their training schools.

This study explores how one Froebelian missionary woman, Annie L. Howe, translated and transformed Froebel's theory at her teacher training school and how her Christian beliefs and values influenced her pedagogy and practice at the school. This study contributes to previous scholarship. Howe's Glory Kindergarten has been well researched in both Japan and internationally. Two particularly prominent works are Roberta Wollon's article “The Missionary Kindergarten in Japan,” and my article “A Chrysanthemum in the Garden: A Christian Kindergarten in the Empire of Japan.”Footnote 9 Although many studies focus on Howe's Glory Kindergarten and/or her contribution to the dissemination of Froebel's theory and the development of kindergartens in Japan, few have examined Howe's kindergarten training school and her beliefs and values as a missionary Froebelian, which is why this study is significant. This paper, therefore, considers the role of religion in missionary women's implementation of Froebel's theory to understand how Christian beliefs and values influenced pedagogy and practice at their training schools. Through the case of Annie L. Howe and her Glory Kindergarten teacher training school in Japan, this paper illustrates the importance of the individual in the development of Froebelian pedagogy and practices. By highlighting day-to-day training experiences, Froebelian theory, and curriculum at Howe's Froebelian kindergarten teacher training school, this study contributes to the body of knowledge about how teaching, learning, curriculum, and pedagogic discourse were transformed not just by the decisions and actions of the Froebelians but also by Christian values and faith. It examines, in particular, how Froebel's theory was used to disseminate Christianity and to create Froebelians in the spirit of Christian pedagogy. More importantly, it highlights the importance of the individual—and the individual's beliefs and values in the dissemination of Froebel's theory.

The study draws on the wealth of information contained in Howe's personal materials (e.g., her kindergarten journals, articles, books, and photographs and letters to her parents, other family members, and the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions of the Congregational Church in the US), which were mainly collected from the Shoei Junior College Library Archive (Howe's Glory College library) as well as from the Kobe College Library Archive in Japan. These materials, which span a period of forty years, afford an insight into Howe's perceptions as a missionary Froebelian involved in the education of young children, the early childhood profession, and related teacher training.

This paper focuses on the period when Howe ran the school. The study aims to contribute to knowledge about how teaching, learning, the curriculum, and pedagogic discourse were translated and transformed, not only by the professional decisions of the Froebelians, but also by their Christian faith and values.

The Birth of Japanese Kindergartens

Following a period of isolation lasting approximately 215 years under the feudal Tokugawa Shogunate, Japan officially opened its doors to the West in 1868, a historical development known as the Meiji Restoration. The Meiji period (1868-1912) was the most turbulent and revolutionary time in Japan's history, owing to the major political, economic, social, cultural, and educational changes that occurred in those years.Footnote 10 The new government's goals were initially presented in the Oath in Five Articles, which was promulgated by Emperor Meiji in April 1868.Footnote 11 The Oath's fifth article, in particular, encouraged the acquisition of knowledge from the West: “Knowledge shall be sought throughout the world so as to strengthen the foundation of the Imperial Rule.”Footnote 12 The Meiji government leaders enthusiastically sought a wide range of knowledge and skills from a number of Western countries, believing that such sources of knowledge and skills and their industries could be the key to national survival in the face of Western power.Footnote 13 The Meiji government was particularly intent on escaping Western subjugation. Therefore, it perceived rapid modernization, enlightenment, and industrialization without the loss of national identity as being essential to gaining parity with Western nations. Education was regarded as a key instrument in the formation and consolidation of the new nation-state of Japan. The Meiji government created the Ministry of Education in 1871. It also promulgated, in 1872, the Fundamental Code of Education, along with establishing a compulsory education system.Footnote 14 Although kindergarten education was not included in the official public education system, it was introduced as an educational institution for young children between the ages of three and six. The Ministry of Education established kindergartens primarily to increase the elementary school enrollment rate and foster a high level of academic performance, especially in reading, writing, and arithmetic, as well as prepare children for the next school level.Footnote 15 The Meiji government authorities and the Ministry also considered the development of kindergartens to represent the process of modernization.Footnote 16

With the establishment of the first kindergarten, a wide range of literature on kindergarten education was brought from Europe and the US to Japan. These texts and books were translated into Japanese and introduced during the first two decades of the Meiji era. They were useful for the dissemination of ideas regarding the education of young children and the development of Japanese kindergartens. In particular, Shinzo Seki (1843-1880), who later became the first principal of the first Japanese kindergarten, introduced the ideas of kindergarten education to Japan by translating Douai's The Kindergarten: A Manual for the Introduction of Froebel's System of Primary Education into Public Schools; and for the Use of Mothers and Private Teachers.Footnote 17

Fundamentally, Froebel's theory has a religious aspect. Froebel believed that the Christian religion serves to wholly complete the mutual relationship between God and man, and all education that is not founded on Christianity is one-sided, defective, and fruitless.Footnote 18

However, although Seki referred to the concept of God many times in his work, the specific word “God” hardly ever appears in his translation, an expression of the contemporary Japanese social and political milieu. Instead, Seki created an edited translation where God is referred to as Sozobutsu shu (the Creator).Footnote 19 Seki did not introduce Froebel's theological perspectives, as he considered Froebel's ideas to be abstract, metaphysical, and extremely religious and therefore too complex for Japanese people to understand. Moreover, these ideas were unsuitable for the contemporary social and political context, as Japanese people had no idea what kindergarten education was. Johann and Bertha Ronge's Practical Guide to the English Kinder Garten (Children's Garden): For the Use of Mothers, Nursery Governesses, and Infant Teachers; Being an Exposition of Froebel's System Of Infant Training (1858) was also widely used during the initial stages of the establishment of kindergartens in Japan.Footnote 20 This book focused on the methodology of Froebel's Gifts (wooden blocks) and Occupations (a series of hands-on activities such as paper-weaving and paper-folding). However, none of Froebel's works, such as The Education of Man (1826) and Mother-Play and Nursery Songs (1844), were on the list of required literature for the development of kindergartens in Japan. Following Seki's concerns, the Ministry of Education pondered on the notion that Froebel's Christian ideology figured significantly in his kindergarten educational principles, which were not in line with the national religion of Shintoism and its veneration of the emperor of Japan. Under the emperor, children were not to be exposed to Froebel's Christian viewpoints, as they were mystical and metaphysical and rooted in a firm Christian ideology.Footnote 21 In order to properly indigenize and localize kindergarten education as Japanese centers for pre-school learning, the ideas about kindergarten education were translated according to Japan's political, social, cultural, and educational needs.

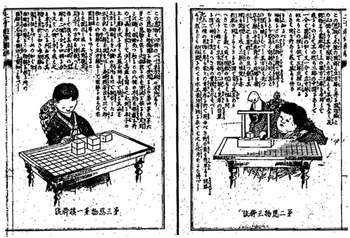

In 1876, the first kindergarten was established as part of the Tokyo Women's Normal School (today known as Ochanomizu University Kindergarten). Its initial intake was seventy-five children aged between three and six who were mainly from upper-class families.Footnote 22 The teachers at the kindergarten included Clara Zitelmann Matsuno,Footnote 23 whose German background exposed her to Froebel's kindergarten principles; Fuyu Toyoda; and Hama Kondo.Footnote 24 The Ministry of Education wanted to incorporate every single practical element of Froebel's kindergarten curriculum into that of the Japanese kindergarten. These elements included songs, games, and Froebel's Gifts and Occupations and other pedagogical materials. Kindergarten teachers provided sets of Gifts and Occupations for children to finish or let them copy from a drawing of Gifts and Occupations on the blackboard.Footnote 25 However, while the use and operation of Gifts and Occupations was highly stressed in the Japanese kindergarten curriculum (see Figure 1), the Froebelian theological views that supported his curriculum were excised.Footnote 26

Figure 1. The instruction of Froebel's Gift 1 and 2. Source: Shinzo Seki, Yochien Ho Nijyuyugi [Kindergarten methods—twenty plays] (Tokyo: Aoyamado, 1879), 10–11. Reproduced by kind permission of National Diet Library Digital Collection, Tokyo, Japan.

Kindergarten Teacher Training Programs in Nineteenth-Century Japan

The Ministry of Education also developed the first kindergarten teacher training course, provided at the Tokyo Women's Normal School in 1879. Clara Zitelmann Matsuno was the main instructor and led the training course. The entrance requirements were limited to women aged between twenty and forty who were in excellent health, were personable, and displayed high numeracy, literacy skills, and intellectual competence. The first graduates were sent to various regional towns, such as Osaka and Kagoshima, and took an active part in the development of kindergartens as central fixtures in these places.Footnote 27 However, the course only lasted a year because there was an insufficient number of students to facilitate its operation; it remained unavailable until 1896. In the nineteenth century, the promotion of elementary education had just begun; Japanese people did not acknowledge the importance of elementary education and in fact, relatively few children attended elementary schools. Therefore, there were very few applications to primary teaching courses at conventional schools. Up until the Tokyo Women's Normal School's reopening of the kindergarten teacher training course in 1896, the course was combined with the school's elementary education teacher training course. The original kindergarten training course offered two terms (23 hours per week) for one year. However, to qualify as kindergarten teachers, students enrolled in the elementary education teaching training course were, for example, only required to complete a couple of extra modules, to gain practice teaching at a kindergarten and develop operational knowledge of Gifts and Occupations. The ministerial authority reasoned that teacher did not necessarily have to be scholars. As long as they were women and could teach elementary school children, they could undoubtedly look after young children.Footnote 28

During the expansion of kindergartens in the 1880s, kindergarten teacher training courses were limited, and the shortage of kindergarten teachers was a constant issue.Footnote 29 In order to meet the immediate needs and demands of kindergarten teachers, the quality of training courses suffered, and the work was fragmentary and inconsistent. The Ministry of Education offered a number of ways for the teachers to receive training, in the form of six pathways to becoming a kindergarten teacher: (1) the kindergarten teacher training course, combined with the elementary teaching training course at the Tokyo Women's Normal School; (2) the intensive training courses run by regional normal schools; (3) the short courses or workshops organized by the Ministry of Education or the Local Department of Education; (4) the apprenticeship system in local kindergartens that allowed young women to serve as kindergarten assistants; (5) evening courses organized by private institutions; and (6) the teacher training schools organized by missionary women.Footnote 30 The alternative training courses offered by the Ministry of Education or the Local Department of Education lasted three to six months. The short duration of the training and the lack of instruction in the theory underpinning Froebel's Gifts and Occupations was detrimental to the effective application of Froebel's methods. Also, importantly, the courses were designed to train kindergarten teachers as rapidly as possible in order to meet the growing demand for them. The quantity of available staff was emphasized over the quality of kindergarten teacher training. The courses led to a new and more provisional model of kindergarten training courses under the apprenticeship model, with a less rigorous commitment to raising professional standards.Footnote 31 There was no regular arrangement or legislation regarding kindergarten education, nor were there any training courses or even a rigid curriculum until the Ministry of Education promulgated the Kindergarten Ordinance in 1926.Footnote 32 Supply and demand, funding and remuneration, and differing expectations for kindergarten teachers were identified as the main issues. The balance between quality and quantity also remained tenuous during the nineteenth century.

A Missionary's Mission: The Dissemination of Christianity and the Establishment of Christian Kindergartens and Teacher Training Schools

Historically, Japan did not have an amiable relationship with Christianity. Following the visit of US naval officer Commodore Matthew Perry to Japan in 1853, missionary boards eventually seized on the opportunity to travel to Japan. Their evangelical efforts were initiated through English private tutors, because, at the time, Christianity was still banned in Japan. Soon after the Meiji government lifted its ban on Christianity in 1873, missionary women from various sects set foot on foreign soil. The Meiji government repealed anti-Christian laws in order for the country to gain Western knowledge but offered no specific protection against religious activity.Footnote 33 This period was marked by Japan's favorable reception and acceptance of Christianity and Western culture, and was succeeded by an era of Westernization.

The first missionary group arrived in Tokyo and Yokohama in 1859. Its members all belonged to various denominations in the US and eventually Canada, Britain, and Europe. Missionary activities continued to proliferate, and a wider range of groups were represented, including Catholics, Baptists, Episcopalians, Methodists, and Presbyterians.Footnote 34 These groups promoted grassroots work in the fields of construction, medicine, social welfare, and education as a missionary tool for evangelization.

Missionary educational activities, in particular, had a significant impact on education in Japan. The purpose of establishing educational institutions was to spread Christianity and Western knowledge throughout the nation. Among missionary women's educational activities, the development of kindergartens and schools for girls was one of the most successful activities commercially and in terms of spreading Christianity in Japan. “Kindergarten is our greatest educational and evangelistic agency in Japan,” they boasted.Footnote 35 American missionary women were especially committed to the belief that the best way to spread Christianity was through the development of kindergartens, as had been done in the US between 1870 and 1900.Footnote 36 This dissemination strategy took advantage of the numerous opportunities the missionary women had to interact with mothers, as they typically were the ones who brought their children to kindergarten each day. Thus, by conversing with the mothers, it was possible to deliver Christian values and faith and to propagate Christianity efficiently.Footnote 37

The majority of the missionary women had completed kindergarten training courses in their own countries and were qualified kindergarten teachers. Importantly, they were also advocates of Froebel. Although Froebel's theory of early childhood education was closely interwoven with Christianity, his pedagogy and practice was not the same as that in Christian education. For Froebel, the fundamental concept of the interconnectedness of all life in this world was related to the rules and laws of God. The undoubtedly religious nature of his theory of education was congruent with Christian values; however, the purpose of his kindergartens was not to create Christians.Footnote 38 Missionary women understood the importance of translating Froebel's theory in the spirit of Christianity, but how to deliver their Christian pedagogy and practice along with his theory in Japan was an enduring question for discussion.Footnote 39

The kindergarten program was unorganized in the days of Froebel. Froebel never left behind any sort of manual with detailed instructions about how to create a successful program. Today's programs are based on the models created by earlier generations of Froebelians, who translated his principles into practice. Since Froebel had left behind no detailed program to constrain them, the missionary women considered his spirit and the principles that underlay his work as they began designing a model Froebelian kindergarten for Japan. What were the principles that gave birth to Froebel's informal program; and how could they best be adapted to contemporary conditions in Meiji-era Japan?Footnote 40 Such questions guided their work.

In the first two decades of the Meiji era, Western theories and knowledge were, indeed, held in particularly high regard in Japan, with people showing great appreciation for virtually any Western theory. Froebel's kindergarten theory was no exception. Many Christian schools, including their kindergartens, were considered to be the best places to learn and gain Western-derived knowledge. Upper-class Japanese people, in particular, appreciated and embraced Christianity and the Froebelian theory emphasized by missionary women. However, at the beginning of the 1880s, there was a political backlash against Westernization and Christian evangelization. A desire to preserve or revive traditional Japanese values emerged.Footnote 41 The Meiji government thought the rapid growth of Westernization was making it more difficult to maintain national and social unity, and thus began promoting traditional Shinto practices, most significantly by deifying Emperor Meiji and making his reign a sacred part of Japanese ideology. As Shinto became Japan's state religion during the Meiji period, the government also resisted the presumption that Christianity was a non-negotiable part of Westernization, and it grew opposed of the religion in all its Western forms.Footnote 42

Historically and culturally, Christianity was depicted as a foreign religion that was naturally alien to, if not subversive of, the Shinto Japanese spirit. This opposition guided the drive during the Meiji era to preserve or revive traditional Japanese values, which supported a nationalistic reaction favorable to Shinto, causing the tide of anti-Christian sentiment to grow ever stronger.Footnote 43

The focus of these anti-Westernization and anti-Christianity reactions gradually moved from political to educational issues. In terms of education policies, the political dogmas of state-based Shinto and the idea of a sovereign family, headed by the emperor, ruling Japan were enshrined as key elements of Japanese national identity that were expected to be promoted through education. The Ministry of Education thus acknowledged that to achieve this, it was necessary to not only reinforce the public education system but also control private schools, especially with regard to the missionaries’ Christian schools. By placing its emphasis on the sovereignty of the emperor, based on Shintoism, and promoting the traditional values of Confucianism, the government thus laid the foundation for several years of intense attacks on Christianity. In this period of political and religious turmoil at the turn of the twentieth century, although missionaries supported the government's efforts to rebuild Japan as a nation-state as they disseminated Christianity, the government did not want Christianity to continue to spread. Christian missionaries thus faced practical difficulties in developing Christian kindergartens.Footnote 44

Two decrees in particular created turmoil for the missionary communities: the Imperial Rescript on Education of 1890 by the Meiji government, and the Private School Order No. 12, promulgated by the Ministry of Education in 1899, which strengthened the foundations of imperial rule. The Imperial Rescript on Education signified the country's moral and civic ethos, accentuating the values and ideas of Confucianism, civic obedience and loyalty, filial piety, love of country, self-sacrifice, the requiting of blessings, and the proper practice of rituals.Footnote 45 The path leading to Japan acquiring modern-nation status would be determined by the strong and autocratic rule of a new imperial system emphasizing the emperor's divinity. The Rescript limited Western education's influence in Japanese schools and emphasized Confucianism as the social norm. It also helped to build a Japanese national ideology and identity that would endure until 1945.Footnote 46

The Ministry of Education's Order No. 12 stated that Christian schools were required to be licensed and authorized by the Ministry of Education. It also forbade religious education in any schools. The Order dealt a great blow to missionaries and was ostensibly an attempt by the Ministry of Education to control and cause ruin for Christian schools; in addition, the Ministry demanded the imperial portraits of the incumbent emperor and empress be hung in all schools, at every level of compulsory education in Japan.Footnote 47 Any formal occasions at a school, such as a graduation ceremony, required that imperial portraits and the national flag be displayed and that students recite the Imperial Rescript on Education.Footnote 48 The imperial couple's birthdays were also celebrated as important occasions during which children and students were expected to draw on their own experience of parental love to reflect on their relationship to the emperor and empress, who, in their roles as father and mother to the nation, cared for all families in Japan.Footnote 49 Christian schools and kindergartens were not exempt from these rules. Although kindergartens were not part of the system of compulsory education, they were still under the control and supervision of the Ministry of Education and its regulations.

Consequently, although missionary women strongly resisted the Order, some ultimately accepted it rules for the sake of preserving their kindergartens. Others gave up their licenses, closed down their institutions, and left Japan.Footnote 50

However, teacher training schools were exempt.Footnote 51 This allowed the missionary women who ran kindergarten teacher training schools to continue their mission of simultaneously training teachers and disseminating Christianity in Japan.

Missionary Froebelians and Their Kindergarten Teacher Training Schools

Despite the growth of kindergartens in Japan in the nineteenth century, which was particularly acute during the 1880s, kindergarten teacher training courses were quite limited, which provided a welcome opportunity for missionary women to meet the demand for kindergartens through teacher training.Footnote 52

Missionary women were eager to improve and expand the training schools because they were apprehensive about the quality of the kindergarten training courses provided by the Ministry of Education and the Local Departments of Education. They were already familiar with the unpleasant conditions they had witnessed in those courses and schools.Footnote 53 Annie Howe observed:

In many kindergartens, there are teachers who suffer from inexperience, others from lack of training and methods and some from want of knowledge of what could and ought to be accomplished. . . Again, even in schools where the proper techniques are in evidence the lack of Froebel's strongest point in his philosophy, Christianity the foundation of everything else, is left out.Footnote 54

Missionary women believed that professionals well trained in Froebel's theory and Christian faith and values were an essential prerequisite for the effective promotion of kindergarten education. They reasoned that although students were not Christian when they entered the kindergarten training schools, some might convert to Christianity and become baptized before they graduated. The long duration of the training schools allowed ample time for evangelization and conversion.Footnote 55

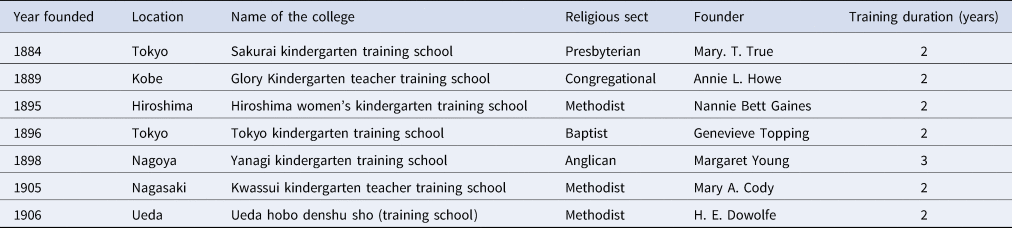

While the kindergarten training courses offered by the Ministry of Education and other Japanese providers were short, with apprenticeships lasting only three to six months, the kindergarten teacher training schools organized by missionary women employed a rigid and advanced teacher training curriculum, with courses extending two or three years (Table 1).Footnote 56

Table 1. The Main Christian Kindergarten Teacher Training Schools in Japan in the early Meiji Era.

Source: Tomoe Shiga, “Meiji, Taishoki Nii Okeru Kirisutokyo Shugi Hoikusha Yosei” [Christian Kindergarten Teacher College During Meiji and Taisho Periods], Bulletin of Cultural Research Institute, Aoyama Gakuin Women's Junior College, no. 4 (Dec. 1996), 68.

The missionary women founded the Japan Kindergarten Union (JKU) in 1906. The purpose of establishing it was to promote kindergarten education, disseminate Froebel's theory along with Christianity, and set professional standards for teacher training schools.Footnote 57 The members represented twelve different denominations including the Presbyterian, Catholic, Congregationalist, Methodist, and Anglican Churches. The JKU held monthly meetings and an annual conference every summer, at which members shared their practices with one another. It also released annual reports, publishing the first report in 1907 and continuing to release subsequent ones for three more decades until 1939, the year the union was merged to form the Japan Christian Federation on Early Childhood Care and Education, which remains in operation today. At the JKU meetings, the sharing of Froebelian practices and curricula was considered a strategy for improving the quality of kindergarten education and teacher training schools. The meetings also covered international trends and research on kindergarten education.Footnote 58 In addition to the goals of maintaining a high quality of kindergarten education and disseminating Froebel's kindergarten theory, the missionaries also highly prioritized evangelization.Footnote 59 Back in the West, in the missionary women's home countries, many Froebelian women, like their counterparts in Japan, established kindergarten teacher training courses along with kindergartens, as teacher training was at the center of the kindergarten movements, tied as it was to the critical issues of “programmatic quality and professionalisation.”Footnote 60

Given the growing appreciation in Japan for Western theories and knowledge and the adoption of Western values, Christian kindergartens were often considered to provide a better quality of education to young Japanese children than the kindergartens that were supported by the Japanese government. Some of the missionary women's practices started to appear in the curricula of those other kindergartens. For example, Miss Fannie Caldwell Macaulay, principal of the Hiroshima Girl's School Kindergarten, introduced hopping and skipping dance to Japanese kindergartens. Annie L. Howe introduced gardening as a pedagogical element into Japanese kindergartens.Footnote 61 The Christian institutions, as a result, became increasingly popular in the 1890s. Their teacher training schools were also acknowledged as institutions that provided virtuous training courses.Footnote 62 Their curriculum emphasized academic subjects, beginning with the study of Froebel's theory and methods and including child development theory and psychology. Eventually, the two-year kindergarten teacher training course and its curriculum became the foundation for kindergarten teacher training and early childhood qualification courses in Japan, and that remains the case today.Footnote 63 With the assistance of missionary women, a good number of qualified kindergarten teachers advanced kindergarten education in the late nineteenth century in Japan. Most of the graduates of missionary women's kindergarten training schools were sent to large cities and various regional towns, where they played an active role in the development of both Christian and non-Christian kindergartens.Footnote 64

An American Missionary Froebelian Woman: Annie L. Howe and Her Kindergarten Teacher Training School

One highly prominent missionary Froebelian woman who had a significant impact on the development of kindergarten education in Japan was Annie L. Howe. She is often acknowledged as a “true” Froebelian and disseminator of Froebel's kindergarten theory of early childhood education.

Annie L. Howe was born into a strict Congregationalist family in Brookline, Massachusetts, in 1852, to Charles Howe (1822-1915) and Mary Howe (1829-1918). She graduated from Rockford Seminary in Chicago, where she studied music, after which she attended the Chicago Froebel Association Training School to pursue a career as a kindergarten teacher. Soon after completing the course, Howe opened a kindergarten in Chicago and worked there as a headteacher for nine years with her younger sister, Mary Deming Howe Rogers (1854-1935). In 1886, Howe learned that the women of the Kobe Congregational Church in Japan were planning to establish a Christian kindergarten and looking to employ a kindergarten teacher. Her application to the position was accepted, and in 1887 she was sent to Japan as a Congregational educational missionary by the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions.Footnote 65 Howe had a twofold mission: establish a Christian kindergarten in Japan and communicate the importance of a kindergarten education founded on Froebel's theory and dedicated to the glory of God.

Upon arriving in Japan, Howe visited many Japanese kindergartens and teacher training schools in preparation for establishing her Christian kindergarten. She was also frequently invited to the Tokyo Women's Normal School and other regional normal schools, as there were few educators available to train kindergarten teachers.Footnote 66 Howe lamented that in implementing Froebel's theory, the Japanese kindergarten training schools lacked a philosophical basis and were too heavily focused on the technical use of the Gifts and Occupations.Footnote 67 But most evident for her in the implementation of the Gifts and Occupations was what she felt was the strongest element of Froebel's theory and that which ought to underline its implementation: Christianity.Footnote 68 In a letter to her sister Mary, she stated:

There is a lack of great world ideals. Japanese normal school education is narrow, and a common school teacher with a truly broad outlook is not rare but is in an unenviable position. . . . Here in Japan, I find beautiful buildings and fine materials (the Gifts and Occupations) manufactured but they have not the foundation principles [Froebel's theory].Footnote 69

Howe acknowledged that the desired standard of excellence in kindergartens in Japan required the training of kindergarten teachers who understood the importance of Froebel's theory.Footnote 70

In 1889, a month before opening a kindergarten, Howe opened a teacher training school named Shoei hobo denshusho. The English translation was “Glory teacher training,” or “Glory,” for short. Footnote 71 It had an enrollment of twelve students.Footnote 72 The entrance requirements for the women enrolling in the Glory Kindergarten training school were that they were between twenty and thirty years old, had a good-natured personality, and possessed a satisfactory high school academic record.Footnote 73

Today, both the Glory Kindergarten and the teacher training school still operate in Kobe, Japan. Since its founding, the Glory Kindergarten teacher training school (today Shoei Junior College) has continued to offer Christian-based character education along with training based in Froebel's theory, and has remained faithful to their original teachings. Traditionally, both the dean of Shoei Junior College and the Glory Kindergarten principal have been Christians. Although the college has lost the evangelical zeal that characterized its early years, Christianity still holds a central place in the structure and operation of the teacher education program, although it is seen more as a moral abstraction than a religious doctrine.

Howe was passionate about training kindergarten teachers, as she believed that there were no kindergartens without them. She acknowledged that the Glory Kindergarten, as a Japanese kindergarten, was under the government and local government's official control; however, she believed that the Glory Kindergarten teacher training school was hers.Footnote 74 For her, a well-trained and qualified kindergarten teacher was not just someone with the skill to operate Froebel's Gifts and Occupations, but rather someone who recognized the importance of education for young children and the dignity of working with young children. She also expected kindergarten teachers to have a sincere and sympathetic nature. In the larger picture, she believed the purpose of training kindergarten teachers was to promote and disseminate kindergarten education in Japan.Footnote 75 And in addition to producing knowledgeable and skillful kindergarten teachers through Froebel's theory and disseminating the principles of kindergarten education, she strongly wished to propagate Christianity in Japan.

On completion of the Glory Kindergarten teacher training course, candidates were expected to have the knowledge of Froebelian theory and skills to deliver the best education for young children. Howe created five principles that served as the foundation of young children's education at the Glory Kindergarten; they also applied to the kindergarten teacher training school and were shared with parents:

1. Wisdom, power, and beauty in the world are God's work, and the education of young children should recognize the importance of awakening respectful love and praise to God;

2. Educate children in an imaginative way. Tell many good stories to them and use the most beautiful materials and sources;

3. Music is the most beautiful and wonderful gift given to us by God; therefore, teaching music to children helps them develop their emotional sensibility;

4. Foster the feeling of peace in the world and teach children the importance of love and empathy;

5. Acknowledge the importance of a good relationship with the children's family and collaborate with them to provide the best education.Footnote 76

Eventually, the Glory Kindergarten teacher training school developed a good reputation and became a model for kindergarten teacher training schools not only for the missionary groups but also for the public sector in Japan. In 1908, Howe's longtime commitment and devoted service to her kindergarten teacher training school and, importantly, the good reputation of the graduates resulted in the government's decision to authorize the Glory Kindergarten teacher training school to award graduates a teaching certificate without a state examination given by the Local Department of Education. At that time, students who completed their teacher training courses at Christian-based institutions were generally required to take an examination to qualify as a kindergarten teacher.Footnote 77 The Glory Kindergarten teacher training school became the first Christian institution to earn this privilege in Japan, owing to its strong reputation.Footnote 78 All graduates Howe taught were highly favored over other graduates, and many government schools in regional Japan frequently hired graduates of the training school as school directors. They all became Christians and played an active role in both Christian and non-Christian kindergartens in Japan.Footnote 79

A Froebelian Practice and Pedagogy in the Spirit of Christianity

The Glory Kindergarten teacher training school began with morning worship at 7 a.m., and from 9 a.m. on, students spent the rest of the morning with children as part of their kindergarten placements (Figure 2). From 1 p.m. to 4 p.m., students intensively studied Froebel's theory, focusing on the methodology of the Gifts and Occupations. The kindergarten teaching course was delivered 38 hours per week over a two year period. Students were also required to spend most of after the school hours complete their homework. The curriculum of Glory Kindergarten teacher training school was based on the curriculum of the Chicago Froebel Association Training School, where Howe completed her kindergarten teacher qualification.Footnote 80

Figure 2. Glory Teacher Training School Students and Children at Glory Kindergarten (date unknown). Courtesy Shoei Junior College Archive, Kobe, Japan.

In contrast to the short length of the Tokyo Women's Normal School course, the Glory Kindergarten teacher training school course was a two-year program that required thirty-eight hours of lessons per week (Table 2). The course comprised the key elements of Froebel's kindergarten curriculum, which included Froebel's kindergarten theory and pedagogy, Gifts and Occupations, arithmetic, geometry, geography, history, children's literature (e.g., stories and poems), gymnastics, music, psychology, physics, zoology, botany, geology, hygiene, and student-teaching practice. As music was a passion of Howe's and part of her educational background, it was one of the most studied topics at the training school. It was, she explained, the most beautiful and important gift from God, and therefore should be an essential aspect of Christian education for young children. The students used songbooks featuring a selection of hymns prepared by Howe herself.Footnote 81 Another course subject, believed by Froebel to be one of the most important elements of a small child's education, was the study of nature, which featured topics such as leaves, seeds, silk work culture, care for newly-hatched chicks, shells, stones, and the resurrection of life as illustrated by the four seasons.Footnote 82

Table 2. A Comparison of Teacher Training Curricula: Tokyo Women's Normal School Kindergarten Teacher Training Course and Glory Kindergarten Teacher Training School.

Source: Japan Ministry of Education, Yochien Kyoiku Hyakunenshi [One-Hundred-Year History of Kindergarten Education in Japan] (Osaka: Hikarinokuni, 1979), 80-90.

The course placed significant emphasis on Bible study, and the students were obliged to study the Bible for at least two hours every day to better understand the Christian-based principles of Froebel's kindergarten theory.Footnote 83 Howe's course covered both the Old and New Testament, as those texts are the heart of the Christian faith. Howe believed it was essential to understand Froebel's kindergarten theory through the lens of the word of God, and to develop a strong spiritual life in daily life. She encouraged students to teach children Christian values by using the Bible, which she believed contained many wonderful stories for young children from both a literary and moral perspective, and could be resources for everyday living and kindergarten programs.Footnote 84

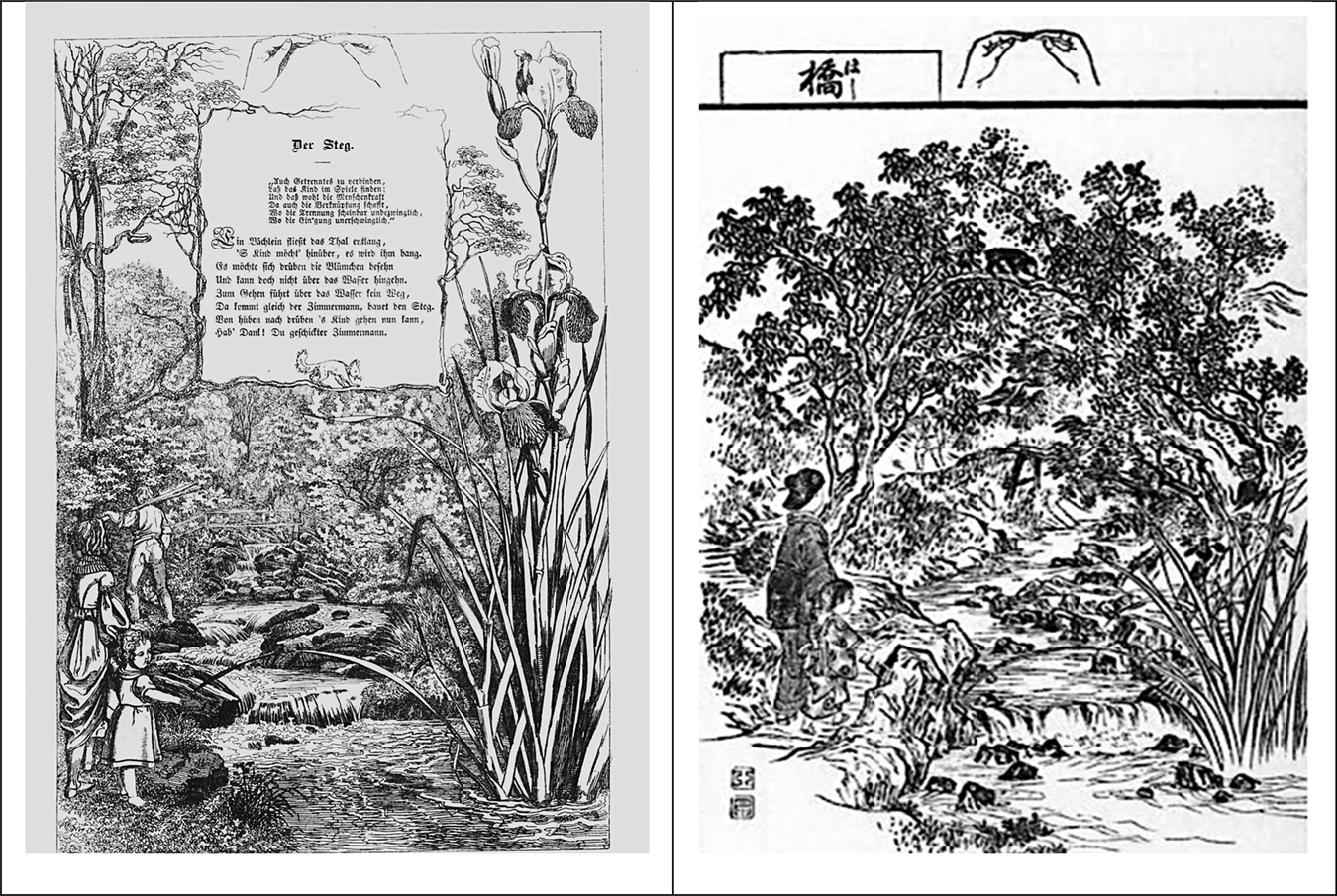

In terms of written teaching materials, Howe carefully selected several books in English, some of which she translated into Japanese. She also translated American children's songs into Japanese, and edited and created songbooks for children and students. Additionally, Howe published an introduction to kindergarten teaching for students in Japanese (Figure 3).Footnote 85 With regard to assisting students in understanding Froebel's theory, she believed the most important texts were Froebel's The Education of Man and Mother-Play and Nursery Songs. Both books were translated by Howe, making her the first person to translate Froebel's work into Japanese. The translations were and still are considered Howe's most remarkable contribution to early childhood education in Japan. For Howe, the books’ explanation of Froebel's principles conveyed to future kindergarten teachers the critical message that children's early introduction to the force that was manifested in all living things ensured that they would respect the spirituality of existence.Footnote 86

Figure 3. Teaching Materials and Textbooks used at Glory Kindergarten Teacher Training School Selected, Translated, Edited, and Written by Annie L. Howe.Footnote 87 Source: Shoei Junior College Archives, https://www.glory-shoei.ac.jp/tandai/library/.

Howe considered, in particular, Froebel's Mother-Play and Nursery Songs to be his most triumphant achievement. It accomplishes its dual intended purpose of revealing how reason continually manifests itself in childhood, and how children can uphold reason's ideals through their imagination and affection.Footnote 88 Her translation of the book into Japanese carefully adapted the content in terms of Japan's cultural context, employing illustrations that depicted real Japanese life and culture. She believed that the explanation of Froebel's philosophy in the Japanese cultural context could improve the Japanese people's understanding of his philosophy.Footnote 89

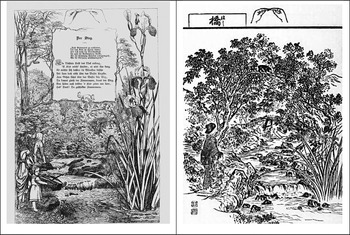

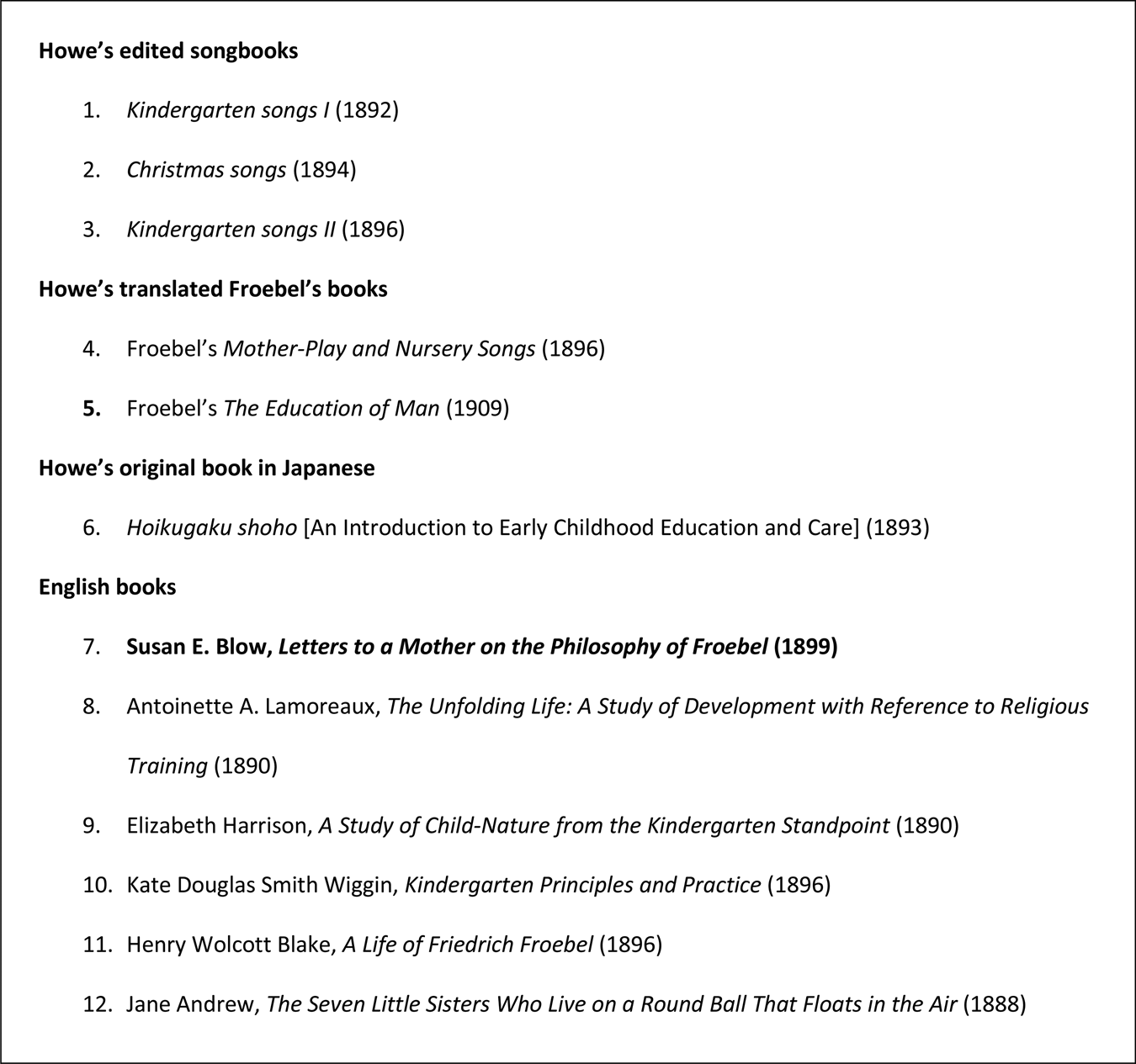

Howe also acknowledged that Froebel's Mother-Play and Nursery Songs presented the fundamental principles of Christian education. She asked students to choose one or two songs from the book and explicate their meaning. Howe then more fully explained the meanings of the songs by linking them to Bible stories and Froebel's theory. She also picked particular songs and interpreted them through literary, historical, and psychological perspectives.Footnote 90 For example, the song “The Bridge” is about a child who longs to cross a stream but is hindered by its depth and width. Suddenly, a carpenter arrives and constructs a little bridge so that the child can cross the stream (Figure 4). The song provides a metaphor of bridging: connecting separated individuals and disconnected people.Footnote 91 Howe's interpretation was inspired by chapter 12 of the First Epistle to the Corinthians, which provides an explanation of God's nature and why God gives spiritual gifts to Christians. She believed the carpenter in the song represented Jesus, who was always there to help people if they believed in his existence.Footnote 92

Figure 4. Left, Illustration from Friedrich Froebel, The Songs and Music of Friedrich Froebel's Mother Play (Mutter und Kose Lieder), ed. Susan E. Blow (New York: D. Appleton and Co., 1895), 10. Right, Annie L. Howe's Japanese translation of Hahano Yugi Oyobi Ikujiuta [Mother Songs and Play] (Kobe: Glory Kindergarten, 1896), 77, National Diet Library Digital Collection, https://dl.ndl.go.jp/info:ndljp/pid/1057343.

Froebel's Mother-Play and Nursery Songs was the principal tool that enabled Howe to transmit Christian values and was linked to Froebel's theory of divine unity. In the early twentieth century, Howe's translation of Mother-Play and Nursery Songs was widely used, not only in Christian-based missionary training schools, but also in many non-Christian teacher training courses in Japan.

In Howe's translation of Mother-Play and Nursery Songs in the Japanese cultural context, one priority she pursued was to authentically reflect Japanese culture. She wanted students to understand Froebel's theory and its manifestation of Christianity through their personal lived experience as Japanese people. In particular, Howe highlighted the Froebelian emphasis on the beauty of nature and the unity of life. To that end, a class on the art of Japanese flower arrangement (ikebana) was included in the training school curriculum. Ikebana is an art form in Japanese culture that reflects views of nature and the universe.Footnote 93 It originated as a ritual flower offering in Buddhism, beginning in the sixth century. After the Meiji period, ikebana became popular and many young Japanese women practiced the art as part of their preparation for marriage.Footnote 94

At the Glory Kindergarten teacher training school, practicing ikebana had a double purpose: the flower arrangements were also expected to represent Froebel's philosophy of unity and the beauty of nature. Howe believed that this practice assisted students in understanding concepts about beauty through their Japanese culture (Figure 5).Footnote 95 Ikebana has strict rules regarding display and composition. The three main components are known as ten (heaven), chi (earth), and jin (human beings). The inseparable components of Ten-Chi-Jin show how all of life's elements are interrelated and connected in a state of harmony and peace. In Howe's Froebelian theory, man is positioned as a conduit between heaven and earth. The components of Ten-Chi-Jin were closely linked to Froebel's educational principle of the law of unity. More importantly, it was received well in the Christian world as it reflected God's creation of heaven and earth and human beings.

Figure 5. Ikebana (arranging flowers) at Glory Kindergarten Teacher Training School (date unknown). Courtesy of Shoei Junior College Archive, Kobe, Japan, https://www.glory-shoei.ac.jp/tandai/library/.

In 1927, Howe completed her mission and returned to the US. During her time in Japan, she trained 270 students, and over half of those students went on to have important roles in the kindergarten field.Footnote 96 Many of her graduates were employed in important positions throughout Japan. As part of the official farewell to Howe, an “Appreciation” written by a missionary woman, Agnes Gordon, appeared in the 1927 JKU annual report:

Full of enthusiasm for her profession, and love and loyalty to Jesus Christ, a kindergarten to her meant a place where little children learned to know their Heavenly Father and his wonderful world. A training school meant a place where young women were inspired by this idea and were taught the best methods of imparting this knowledge.Footnote 97

Howe's forty years of service in Japan were rewarded when the Ministry of Education recognized the importance of kindergarten education by including kindergartens as an official component of the Japanese education system. Importantly, in 1940, she was awarded the Blue Ribbon Medal by the emperor of Japan. It was acknowledgment, finally, of Howe's work and her devotion to kindergarten education and teacher training, which came to be respected in Japan for its high standard and excellence in the field of early childhood education.Footnote 98

Conclusion

In the nineteenth century, the kindergarten theory of Friedrich Froebel spread around the globe, with many Froebelians transferring his ideas about kindergarten to many different countries. The translation and transformation of Froebelian theory and pedagogies were influenced by social, cultural, political, and educational needs and pressures of the host country. However, this study found that the translation and transformation of Froebelians’ pedagogy and practice were also highly influenced by the Froebelians’ personal beliefs and the values embodied in their ideas about early childhood education. At the dawn of the modern age, many missionary women arrived in Japan and engaged in educational work during the embryonic period of Japanese modernization and Westernization. Due to political pressure and the government's promotion of nationalism together with the Shinto religion, Froebel's theological perspectives were controversial, and missionary women were not able to instill Christian beliefs and values into the kindergarten curriculum. However, through their kindergarten teacher training schools, they contributed to the dissemination of kindergarten education rooted in Froebel's theory, and in turn, Froebel's ideology lived in their Christian missions.

Missionary women contributed to the development of kindergarten teacher training schools, at a time in the nineteenth century when kindergarten teacher training courses organized by the Japanese authorities were limited. Their two-year course and curriculum became a tradition in Japan, and they established the foundations of a kindergarten teacher training and early childhood qualification system that exists today. Among the missionary women was Annie L. Howe, whose period of service in Japan spanned forty years and whose contribution to the training of kindergarten teachers is truly remarkable. For Howe, gaining knowledge of Christianity was essential to understanding Froebel's theory and discovering its relevance to kindergarten education. Her Froebelian pedagogy was, therefore, strongly influenced by her Christian faith and values and her loyalty to God. More than 130 years have passed since Howe established the Glory Kindergarten teacher training schools. Even today, her work regarding not only the Glory Kindergarten but also the Glory Kindergarten teacher training school is still strongly evident, as is her Froebelian and Christian spirit in the Glory curriculum. A 2020 book commemorating the 130th anniversary of the Glory Kindergarten, entitled Mother Shoei—Connecting Rainbows, acknowledges Annie's Howe's dedication:

The school remains a testimony to the continuous work Annie L. Howe put in over her forty total years in Japan. This was no easy feat. Systems change with the times. But it is precisely because for the last one hundred and thirty years until now the institution's forerunners and successors have adhered to the credo which cannot and should not be changed—which our founder Annie L. Howe turned into the foundation for our curriculum—that Shoei Kindergarten remains blessed to this day with a solid community of supporters.Footnote 99

Dr. Yukiyo Nishida is a lecturer of early childhood education at the School of Education, University of New England, in Australia. She has been extensively involved in the history of Froebelian pedagogies and is the author of “Something Old, Something New, Something Borrowed, and Something Froebel? The Development of Origami in Early Childhood Education in Japan,” Paedagogica Historica 55, no. 4 (Jan. 2019), 529-47. Her recent projects include the history of childhood in Japan.