On 27 July 2012, in Ansan, South Korea (Korea hereafter), a strike in an automobile parts company, SJM Co., was violently broken up by a group of riot-gear clad personnel, all hired by a security service firm which specializes in labor dispute suppression. One of the 42 injured workers testified at a congressional hearing:

The factory floor was full of the blood of injured unionists. We were beaten and chased by the errand men, running toward the police officers blockading the factory but ignored. […] Some unionists escaped the factory to report the incident to the police but none of the officers showed even the slightest concern (National Assembly, 2012).

The managers of Samsung also conspired to suppress the union by hiring union-busting specialists and bribing police officers and labor inspectors (Kyunghyang Shinmun, 11 August 2020: 9).Footnote 1 Under the progressive Moon Jae-in government, violent labor suppression by private contractors continued in workplaces including GM Korea, KIA Motors, and Hyundai Motor Company (KMWU 2018; Kŭmsok Nodongja, 13 February 2018; KMWU, 2020). ‘As it becomes clear that the police are not coming to drive us [the union] off, the management exercises severe violence through private contractors (sajojik) against us,’ told the representative of the subcontractors' union of the Daewoo Shipbuilding and Marine Engineering recently, under the conservative Yoon Suk-yeol government (Voice of People, 11 July 2022).

Korea used to employ direct state intervention in labor disputes with its own repressive apparatus to suppress labor unrest during the authoritarian-developmental era (1961–1987), which is a common, shared experience among developing countries (Fröbel et al., Reference Fröbel, Heinrichs and Kreye1981; Deyo et al., Reference Deyo, Haggard and Koo1987; Valenzuela, Reference Valenzuela and Regini1998). Private proxies in turn emerged to provide those same services to supplement chronically limited capacity in those countries (Ong, Reference Ong2018).Footnote 3 Korea, however, showcases a different pattern, with the collaboration between state actors and non-state specialists in the market for domestic violence occurring simultaneously with increases in state capacity (Kim and Porteux, Reference Kim and Porteux2019). In other words, the Korean state had, and continues to have, the necessary coercive capacity to act but chooses instead to engage in contracting (direct and otherwise) with private contractors for services that are often more costly (economically and politically), than state-based sources. Furthermore, we are presented with having to explain the persistence of political and physical violence in Korea despite the consolidation of liberal democracy as Figure 1 highlights.Footnote 4

Figure 1. Democracy, government effectiveness, and the changing trend of physical and political violence in Korea, 2000–2019 (normalized).

Source: Modified from V-Dem data set v.11.1 (2021).Footnote 2

Few studies have addressed the causal mechanisms shaping such theoretically ill-explained, yet empirically well-established patterns. Although there is growing work on the role of private security/military companies and related political violence, much of it is focused on cases in developing – i.e., low-capacity, non-democratic polities – which we find less theoretically puzzling (Radziszewski and Akcinaroglu, Reference Radziszewski and Akcinaroglu2012; Avant and Neu, Reference Avant and Neu2019; Eck et al., Reference Eck, Conrad and Crabtree2021).

Our argument specifically highlights democracy as a key independent variable which is conditioning the decision over outsourcing political violence and other socially sensitive tasks. In the wake of democratization, the Korean state developed a dualistic labor control scheme, deliberately ignoring management-conducted violence in the emerging unorganized sector while directly regulating the core organized-labor sector. The persistent, and often unlawful, militancy and politicization of industrial contention in the organized sector along with the fragmentation and isolation of protest in the unorganized sector eventually undermined the political effectiveness of labor despite the growth of civil society in Korea.Footnote 5 This study will shed light on explaining how democracy plays a critical role in changing a state's labor repression strategy, thus necessitating new political orders and complex, interdependent relationships between state and non-state specialists in violence. Such patterns are not predicted by conventional understandings of Weberian conceptions of the state, in which state-building and maintaining strategies revolve around the goal of monopolistic control over the means and use of violence.

In order to establish and test our argument, we rely on a careful theoretical discussion and empirical evaluation of the case of Korea, through a detailed deep description and a process-tracing/analytic-narrative, within-case approach that has multiple observations across multiple sectors,Footnote 6 which, in turn, provides key differences in our dependent variable – i.e., policing strategies including outsourcing violence – and independent variables across space, time, and issue-area. Our empirical evidence stems from government statistics and figures, media accounts, investigative reports by governmental and non-governmental organizations, National Assembly documents, and secondary resources. The empirics were then triangulated to ensure robustness and reliability.

In terms of justification for the use of Korea as our case setting and thus source of empirics, besides the fact that this advanced polity has often been overlooked in western-based analyses, Korea is, as of 2022, the 10th largest economy in the world, and has been in the democratic camp since its transition in 1987, with peaceful transitions of power since, the latter of which is the key aspect constituting our arguments.Footnote 7 We find that Korea is a natural and advantageous case for a better understanding of how violence evolves in advanced industrialized, democratic polities from a comparative context.

After setting up the theoretical puzzle by critically examining the state development literature, which emphasizes the political elite's preference for state-based coercion, and extant explanations for the general trend toward the privatization of public activities, we will provide our alternative hypotheses.

1. Critical review of conventional theories

1.1 Weak state, strong state

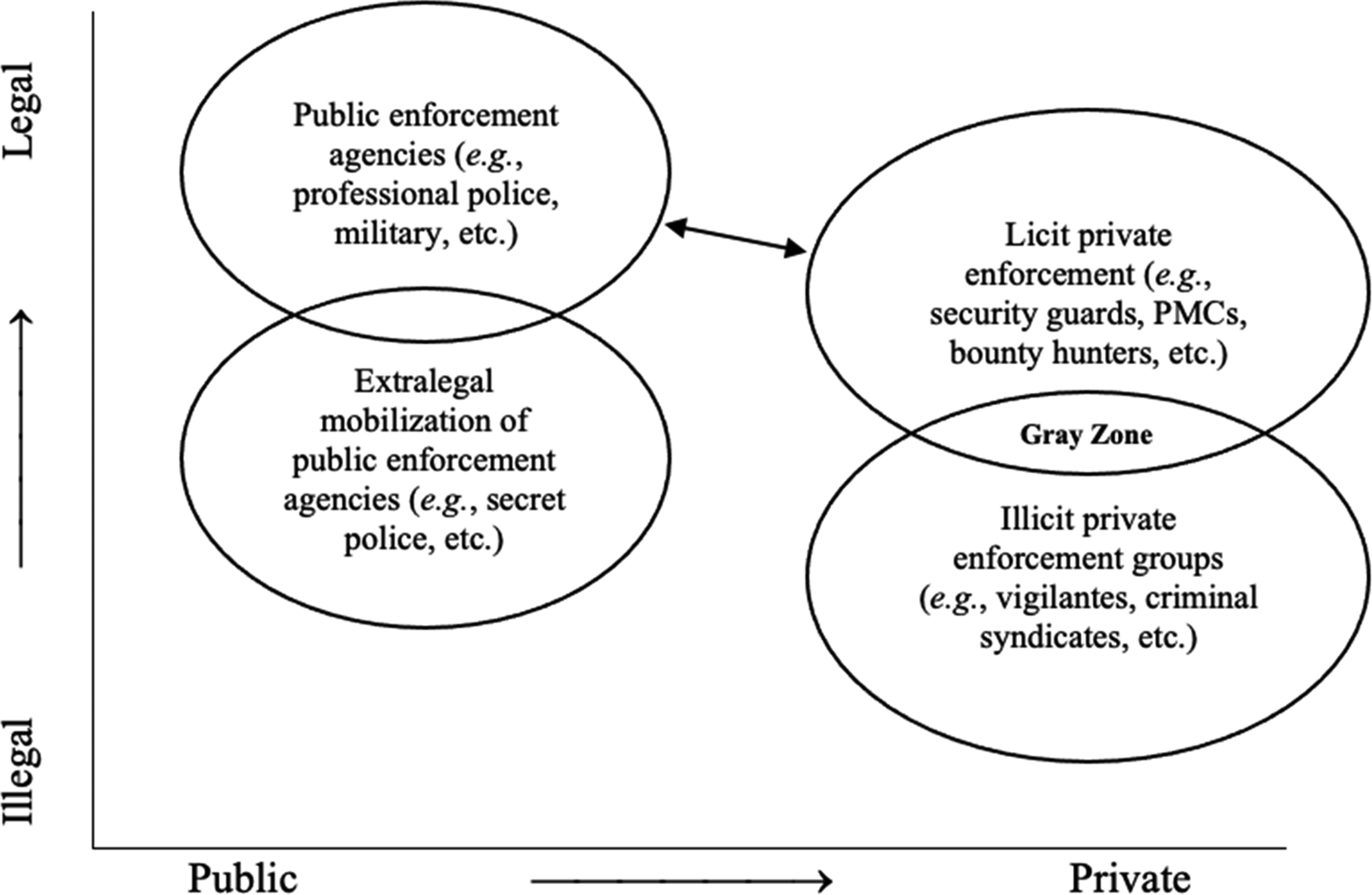

To clarify our puzzle, we seek to explain why political actors in developed, democratic, polities would cooperate with the private market for force, in which the outcome is oftentimes illegal violence against the very citizens the state is promulgated with protecting. Figure 2 visually demonstrates the relationship we are seeking to explain.

Figure 2. Market for public and private force.Footnote 8

On the vertical axis is the legality of the organization, with the horizontal axis consisting of the public–private dimension. In terms of legal legitimacy, public sources of coercion such as the police and military are supreme under conventional understandings of the state. Those public organizations oftentimes are mobilized as an extra-legal force supplementing state power particularly in authoritarian regimes. To the right, are legal, private organizations which operate through legitimacy given by the state, and include groups such as private security and private military companies (PMCs). Below legal private entities, are illegal private organizations, such as mafias, vigilantes, lynch mobs, and so forth, which operate outside, and in many respects, directly in conflict with the state's legal code. Complicating the issue is the frequent interaction between legal and illegal groups and connections with the state. This intersection and state connection is what is referred to as the ‘gray zone of state power’ (Auyero, Reference Auyero2008).

Various conceptualizations of states center on the necessary condition required to create predictable, widespread patterns of compliance and cooperation (Weber, Reference Weber, Gerth and Mills1946; Olson, Reference Olson2000). Those tasks depend upon the state's coercive capacity and superiority vis-à-vis competitors. Further, scholars have utilized low state capacityFootnote 9 as a key variable in explaining why political elites have had a strong tendency toward outsourcing violence, especially in nascent polities (Tilly, Reference Tilly, Evans, Rueschemeyer and Skocpol1985; Thomson, Reference Thomson1994). Tilly in particular notes that state actors employed a range of methods to obtain or expand authority including the buying, subjection, and eventual eradication of private violence once state-based and sourced militaries gained sufficient capacity (Tilly, Reference Tilly, Evans, Rueschemeyer and Skocpol1985: 173–175). In short, once sufficient compliance-inducing capacity was obtained, the reliance on private specialists in violence was posited to decline. The weak-state capacity argument thus can be summarized as follows: states which lack capacity, especially coercive capacity, outsource violence in order to obtain such necessary comparative advantages and/or strengthen capacity where it is either non-existent or otherwise most vague.

The well-documented US experience during its period of industrialization largely fits the general pattern outlined by the weak-state argument, and thus, can be considered as one of the most typical cases. The process of state development in no small part came as a result of industrialization. The rise of organized, violent labor constituted the impetus to strengthen and centralize the USA's coercive institutions which had been largely downsized following the Civil War (Skowronek, Reference Skowronek1982: 85–120). While largely the same antebellum conflict continued, varying levels of political capitulation due to electoral outcomes produced mixed responses to industrial action and violence such as what occurred during and following the Great Labor Strike of 1877 and other industrial disputes in which local militias and regular military were called conjointly to suppress unrest (Taft and Ross, Reference Taft P, Ross, Graham and Gurr1969: 288–289). Although the federal armed forces and supporters sought to capitalize on the increased private sector demands as a key rationale for a larger national public force, such plans were initially blocked in Congress, in favor of the expansion of local to state-level militias, in part the precursor of the modern National Guard, with ties and control more closely aligned to small-government mentalities. This compromise in turn ostensibly fit into the interests of industrialists which often equipped and funded such quasi-private forces for the primary purpose of organized labor suppression. Private firms which specialized in labor suppression emerged and/or expanded their activities, and some firms opted to keep operations in-house and developed their own coercive branches, which operated legally through statute (Archer, Reference Archer2001: 201–203).

Although outsourcing practices were ubiquitous, through the lens of history, we can clearly see that once compliance inducing capacity reached sufficient levels, such collaborative relationships in kind, declined (Thomson, Reference Thomson1994). Said differently, states had a habit of contracting out the services of private forces when their own were deemed insufficient, yet fails to explain instances of outsourcing in high-capacity states – thus making the phenomenon puzzling. The following is our analysis of the existing literature which has emerged in response to this empirical lacuna.

1.2 Captured, colluded, or privatized state supposition

While the weak-state supposition offers substantial insight, low-capacity, as an independent variable, is neither a necessary, nor sufficient explanation, particularly in strong states. This reality has led to several competing conventional explanations of state–labor relations in Korea, which can largely be collapsed into the following categories: (1) Marxian suppositions of state capture; (2) neo-corporatism or bureaucratic authoritarianism; and (3) the neo-liberal perspective.

Marxist scholars detailed how Korean labor disputes were frequently handled by institutions like the police, the Korea Central Intelligence Agency (KCIA), as well as thugs hired by the management to intimidate workers (Launius, Reference Launius1984). Throughout Korea's industrialization period, the state formed a powerful alliance with private capital to serve the interest of the capital-in-general domestically (Kim, Reference Kim1988: 301–314), or the stability of the international division of labor (Long, Reference Long1977), by using its repressive state apparatus for labor control. The capitalist class, as industrialization progressed, gradually vied to utilize their own resources for labor suppression (Pak, Reference Pak and Pak1987; Im, Reference Im1998), which eventually facilitates the decline of the working class through neo-liberal labor reforms (Gray, Reference Gray2008). Since this use of private violence to suppress labor by management is often – as in the Korean case and elsewhere – supported by the state's legal code, they argue that it is a ‘joint action of individual capitalists and the state captured by the capitalist interest’ (Pak, Reference Pak and Pak1987: 305). This image of the captured state is supported by the ‘existence of the state-capital alliance in labor repression as crystallized by the routinized appearance of the state's control agents at the workplace’ (Lee, Reference Lee1988: 155).

One noticeable aspect of the Marxian approach is its understanding of the effect of democratic transition on state–labor relations. Since labor unions became increasingly empowered during democratization, it has become more difficult for the state to control labor movements by solely relying on the repressive state apparatus or using co-optation strategies. ‘As the authoritarian developmental state loses its administrative capability to intervene in the market,’ a commentator describes, ‘so private capital moves in to replace the role of the state in exercising ruthless power over the workers through the state apparatus’ (Shin, Reference Shin, Schmidt and Hersh2000: 156). Although the state could not be ‘brazenly anti-labor and pro-chaebol’ in the post-democratization period, the state-chaebol interdependence favored authoritarian labor repression because the state is ‘fundamentally anti-labor’ (Lie, Reference Lie1991: 507–508).

Scholars of the Marxist tradition thus find little to no substantial difference between the progressive regimes and their authoritarian or conservative counterparts in the use of repressive state power, as signified by the increased number of police interventions and prosecutions against labor activism. They argue that the Korean state has transformed into a ‘neo-liberal police state’ after democratization (Son, Reference Son1999: 173), which was accelerated following the economic crisis in the late 1990s, pointing out that even under the progressive Kim Dae-jung regime, the government's spy networks and wiretapping practices enable it to launch preemptive strikes against workers' organizations – such as when the police conducted a sneak attack against striking workers in the middle of the ‘exploitative capital-restructuring dynamic’ after the economic crisis (Hart-Landsberg and Burkett, Reference Hart-Landsberg and Burkett2010: 421; see also No, Reference No2010; Song, Reference Song2013).

While the Marxist approach has generally been effective in demonstrating the state's proclivity for repression, it however falls short of explaining the general trend from direct intervention to contracting-out despite its emphasis on democratization. Besides, since the state's intervention is viewed as a result of the changing balance between the state and the capitalists in the ‘capitalist collective action,’ the Korean state's ‘ability to act in a completely dictatorial or arbitrary fashion toward the capitalist class’ is not sufficiently described nor explained (Eckert, Reference Eckert and Hagan1993: 104). In other words, the autonomous and discretionary role of the state, which is the most prominent aspect of Korea, is substantially understated, and further, cannot explain the shift of the state's response following democratization.

Next, the corporatist approach underscores the political nature of labor control by the state for economic development (Choi, Reference Choi1989; Deyo, Reference Deyo1989). This account, in line with the developmental state thesis (Johnson, Reference Johnson and Deyo1987), argues that the authoritarian state suppressed labor for the corporatist interest based on the ideological coherence between the political regime and industry while retaining a strong role in economic policy for state bureaucrats (Fields, Reference Fields1995). Rejecting the captured-state thesis, Korea is viewed to have enjoyed relative autonomy from dominant classes, and, the argument goes, the state formed a developmental coalition with the newly rising capitalists to boost economic growth, which would legitimize the authoritarian regime (Wade, Reference Wade1990). Therefore, there is nothing puzzling in the state's negligence of the violence committed by the private capital as it is commissioned for the interest of the developmental coalition. In sum, the autonomy of the state allows it to implicitly sanction private-based suppression of labor, for the sake of the state, in order to sustain its political and economic stability by facilitating the capitalists, which in turn ‘provides an important link with the international community’ (Koo, Reference Koo and Deyo1987: 174).

While the corporatist account maintains significant explanatory power on the private capital's suppression of labor orchestrated by the autonomous state during the developmental-authoritarian era, the source of state autonomy, which is viewed as given either by international contexts or by the relative underdevelopment of civil society vis-à-vis the state (Cumings, Reference Cumings1984; Moon and Rhyu, Reference Moon and Rhyu1999), is problematic as such autonomy once enjoyed, will eventually be undermined by industrialization and democratization (Cotton, Reference Cotton1992). In other words, this account has difficulty explaining why the state, which had been under growing societal pressure, opted for continuing its repressive stance against labor, i.e., the transition or shift of the state's response to labor unrest particularly after globalization and democratization.

The third, and the increasingly dominant – beyond the case of Korea – approach is the neo-liberalist perspective, which frames the privatization of law enforcement as a response to public pressure for more efficient public service provision (Krahmann, Reference Krahmann2010; Lachmann, Reference Lachmann, Swed and Crosbie2019). It views that the state places violence under the control of the market as it will enhance overall efficiency (Mulone, Reference Mulone2011).Footnote 10 Seemingly un-privatizable functions of the state including law enforcement and national security have been extensively contracted out by private service providers (Mandel, Reference Mandel2002; Avant, Reference Avant2005). Some further find that it has been primarily driven by profit-seeking private actors, which would eventually undermine the basis of state authority (Markusen, Reference Markusen2003; Verkuil, Reference Verkuil2007). This view captures the wave of neo-liberal privatization since the 1990s and how it has influenced the transformation of industrial relations (Lee, Reference Lee2021).

It is, however, empirically difficult to confirm that the state saves economic resources by turning to the private market. The state has frequently intervened in labor disputes in late stages, resulting in losses and damages, both in terms of its personnel and revenue. For example, the violent crackdown on Ssangyong Motor's strike in Korea brought up huge social and political repercussions (Goldner, Reference Goldner2009; Kwak and Pak, Reference Kwak and Pak2013). Also, the core functions of public safety have rarely been privatized and the effect of neo-liberalism-based policies on the governance structure has additionally (to date) been limited. The Korean state has maintained its firm grip even on privatized institutions through its political strength (Kim and Han, Reference Kim and Han2015; Lee and Rhyu, Reference Lee and Rhyu2019). Whenever required, the state has directly engaged in the violent repression of workers' resistance to implement neo-liberal labor practices, continuously utilizing its own repressive apparatus in order to subordinate social rights to market logic, branding social conflicts and political dissents as threats to national security (Hart-Landsberg and Burkett, Reference Hart-Landsberg and Burkett2010; Doucette and Koo, Reference Doucette and Koo2016). In short, there is no sign that the state's function of providing public security has weakened or been completely replaced by private contractors in Korea (Kim, Reference Kim2002: 220–221). What has changed however in policing labor is who confronts the militant unionists on the visible front lines. In the following section, we explain the mechanisms behind this shift in tactics.

1.3 Embedded developmentalism: on the logic of state and non-state collaboration in labor suppression

The ability of political elites to achieve their intended policies and substantive goals is not merely a function of the instruments available to policymakers, nor the cohesiveness of the decision-making structure, but importantly, includes the level of insulation from societal pressures, and is what principally distinguishes our approach from that of the other paradigms outlined in the previous section. Although autonomy alone is not a sufficient condition for the optimization of policy outcomes, without it, ‘state elites would find it difficult to pursue politically sensitive policies associated with shifts in overall strategy’ (Haggard, Reference Haggard1990: 44). Holding all else constant, we assume that the more autonomy state elites have from societal forces, the freer they are to design and implement desired policy goals – especially those of a sensitive political nature. In the reverse, the less autonomy state actors enjoy, the more they must calculate the political consequences over policy choice.

Thus, building upon principally the corporatist/developmentalist literature which emphasizes the role of state intervention in its attempts to engineer economic gains for political rationale (or outright survival) – along with the Marxist's emphasis on the role of democratization and the neo-liberalist insight on the alternative/private means of state coercion – we add in the necessary complexity of accounting for the relative levels of societal and corporatist influence on state actors and decisions. As will be demonstrated in the following section, the state's level of embeddedness has greatly varied across Korea's post-colonial and Korean war eras, from that of a stable authoritarian polity to one which is, by all empirical accounts, a fully consolidated democracy.

Because democratization is our key variable, a discussion of how we operationalize it in our theory is necessary. First, referenced in Figure 1, we utilize the Liberal Democracy Index (LDI) from the V-Dem data set which measures not only the ‘supply side’ (i.e., electoral democracy) but also the ‘demand side’ of the democratic equation.Footnote 11 The key point in utilizing a more wholistic conceptualization and measurement of democracy is to encompass the role that society plays in the functioning of the system – the higher is the level of demand for democracy and political participation from ordinary citizens, the more effective is the democracy, in terms of translating the preferences of citizens into actual policy on the ground and holding decision makers accountable when outcomes differ from societal-wide expectations. In short, the process of democratic transition and/or strengthening at its most basic element is as the process of reduced state-based autonomy from relevant, and pluralistic societal forces. And, minimalist conceptualizations and measurements of democracy simply do not adequately account for such necessary complexity.

Bringing the discussion back to the market for coercion, Merom (Reference Merom2003) argues that democracies are at a fundamental disadvantage in fighting small and/or protracted conflicts. The mechanism affecting a state's ability to fight a war then is something termed the ‘normative difference,’ or the distance between the position of the state's preference and that of the society concerning the legitimacy and toleration of violence, in conjunction with the degree of influence societal forces have over policy choices and their outcomes. When the normative gap is significant and societal forces against such conflict are strong, a state's capacity and success in engaging in such conflicts is significantly diminished (Merom, Reference Merom2003: 22–24). While Merom's study focuses principally on political calculations over international conflicts, we see that the same mechanisms at work in the domestic spheres as well. And, while leaders in autocratic polities as well arguably need to consider such domestic-based opposition and related political costs, survival rates of leaders in democracies as a result of unpopular policy lead us to logically conclude that democratic leaders are especially sensitive (see Bueno de Mesquita et al., Reference Bueno de Mesquita, Smith, Siverson and Morrow2003). In Korea, as demonstrated by Kwon (Reference Kwon, Shin and Chang2011), this country's brutal authoritarian experience and extensive use of police-based violence has created a society which is especially sensitive to state-based violence. The Korean police in turn holds a unique status as government incarnate, where instances of visible police-based violence in the post-authoritarian era embodies symbolic valance among society's liberal forces, thus creating a potentially explosive level of politicization and risk for incumbent governments.

With those discussions in addition to the literature that emphasizes the political aspect of the privatization process (Starr, Reference Starr, Kamerman and Kahn1989; Wolfe, Reference Wolfe1996), we posit that the calculus involved in the state's decision to turn toward the market for private force occurs not for reasons of insufficient state capacity, pursuit of economic efficiency, or surmounting societal influence over the state, but as a direct result of the state's response to the changing state–society relations. In short, we argue that state/non-state cooperation in the market for domestic force is a strategic tool utilized by political elites to avoid punishment by society, for actions deemed necessary, but potentially politically costly – in terms of electoral performance, reputation, or other negative outcomes – because outsourcing and/or implicit or explicit tolerance of such non-state activities, provides politically convenient, plausible deniability for the state (Kim and Porteux, Reference Kim and Porteux2019). Further convenient for the state, as depicted in Figure 2, is that while the market for private force is often dominated by legal firms, many of the activities such firms engage in are illegal. By having non-state groups carry out such extra-legal tasks, the state distances itself from potential political backlash due to less clear culpability. Firms may be sanctioned for especially visible or egregious extra-legal violence, yet the state has the option of treating such actions as ‘bad-apple’ cases while allowing the actual, politically convenient practice to continue without actively addressing the systemic nature of such non-state-based coercive activities.Footnote 12 In short, when outsourcing violence works and successfully reduces the level of police-based action and visible conflict, there is little incentive for the state to attempt to eradicate such practices as there are few observable instances for liberal society to mobilize over.

2. Policing labor unrest in Korea

2.1 Authoritarian control of labor: high capacity, high autonomy

Economic development was framed in many respects as the panacea for the peninsula's travails, and the main legitimization for Park Chung Hee's 1961 coup d’état and continued authoritarian policies, which facilitated the thrust toward export-oriented industrialization. In obtaining, and then maintaining its comparative advantage in manufacturing, the state directly utilized and indirectly supported multiple approaches to ensure the compliance of labor and capitalists including a mix of rule by law, monopolizing the control of unions, and their activities (Alemán, Reference Alemán2010: 82–83). Although unionization and collective bargaining was legally permitted, the right to strike was heavily regulated and, more often than not, discouraged (Kim, Reference Kim, Cho and Kim1994: 132–133). The Park regime also reorganized the Federation of Korean Trade Unions (FKTU) and established mechanisms of control, which allowed the government to become an effective supervisor of labor and to root out leftist union formation and activism (Kwon and O'Donnell, Reference Kwon and O'Donnell2001: 30). As a result, labor unionists and participating workers in the labor disputes were more likely to be punished with the application of non-labor-related laws such as the Assembly and Demonstration Act, the Road Traffic Act, the Anti-Communist Act, and the infamous National Security Act (Shim-Han, Reference Shim-Han1986: 118–119).

If the layers of control explained above were not enough, the state's coercive elements played a direct role in the control of labor (Eder, Reference Eder1997: 9). The KCIA, for instance, frequently carried out investigations, intimidation, and torture. The police in turn were not far behind, having offices and administrators in charge of labor issues being embedded in every precinct located in an industrial area. The brutal suppression reached its zenith after Park declared a state of emergency in 1972.

Since the government's intervention in industrial relations was pervasive, labor disputes often had broader political implications as in the case of the clash at the YH Trading Company in 1979 (Koo, Reference Koo2001: 90–92). When the company shut down the factory and brought in the police, in seeking protection as well as enhancing the politicization of the issue, the workers sought the support of the opposition New Democratic Party. Although it ended with a violent crackdown by about 1,000 police officers – killing a female worker and injuring many, including several opposition lawmakers – the incident put the regime under substantial domestic and international pressure, which eventually became a crucial turning point for the development of nation-wide anti-regime protests (Minns, Reference Minns2001: 186).

Following Park's assassination in 1979, labor activism skyrocketed. New unions were organized and deepened, carrying out around 900 labor disputes during the first 5 months of 1980, which were more than the entirety of disputes during Park's explicitly authoritarian Yushin era (1972–1979) (Kim, Reference Kim2000: 66–68). Nevertheless, another military general Chun Doo Hwan seized power and imposed harsh suppression against social activism, including the brutal Gwangju massacre. As a result, labor dispute incidents plummeted to 186 in 1981 and then to only 88 in 1982 (Woo, Reference Woo1991: 181). The regime further mobilized a total of 1.84 million riot police from 1981 to 1985 to suppress dissidents (Ch'oe, Reference Ch'oe1998: 52). However, such leviathan-like control could not completely eradicate labor activism. Radical activists went underground and infiltrated factories to organize workers (Koo, Reference Koo2001: 105–106). As the military junta relaxed control due to political pressures in the mid-1980s, unions and labor disputes resurged. In 1984 the government recorded 113 disputes, in 1985 there were 265, and in 1986, 276, which were previews for the massive upheaval that would culminate into the Great Workers' Struggle of 1987, and subsequent change in protest suppression methods (Gray, Reference Gray2015: 57–58).

2.2 This is what democracy looks like: the Great Workers' Struggle

Following democratization in 1987, there was a massive increase in unions – with the creation of 1,048 more unions than the previous year. Furthermore, in July and August, there were 3,337 recorded labor disputes which ushered in the Great Workers' Struggle during which 1.3 million workers in 3,300 firms engaged in strikes.Footnote 13 It also triggered the explosive unionization of almost 8,000 new unions in the following 2 years, increasing the unionization rate from 15 to 23% (Alemán, Reference Alemán2010: 85–86). The government responded by mobilizing police units from all across the country, including auxiliary police forces composed of mandatory conscripted personnel. Among them were specially trained riot suppression units known as paekkolt'an, literally ‘white-skeleton squad’ (An, Reference An1989: 153).

However, police brutality, which was increasingly covered by the media due to the timely expanded freedom of the press, undermined the legitimacy of the popularly elected President Roh Tae Woo (1988–1993). In a 1988 survey, only 26.3% of the respondents had a favorable view of the police (An, Reference An1989: 155). Around that time was when the state's move toward the private market for force emerged to the forefront.

During the developmental era, especially in the 1960s and 1970s, there were accounts of firms exercising private force for the outright purpose of suppressing labor. However, most of them were usually employees loyal to firm management contingently mobilized to protect the company's interest against strikers when law enforcement force was neither available nor preferred. These groups were referred to as kusadae, or ‘save-the-company group’ literally (Wŏlgan, Reference Wŏlgan1997: 21–22). In the late 1980s, they began to be organized in a quasi-military form and its first account came from the Hyundai conglomerate (Kwon and O'Donnell, Reference Kwon and O'Donnell2001: 162). When the workers began to unionize themselves, Chung Ju Yung, the founder of Hyundai, called upon his employees who had served in the Marine Corps, declaring union riots to be a part of a communist plot, and ordered them to ‘defeat the labor union’ (Ogle, Reference Ogle1990: 120). As success spurs imitation, Hyundai's practice soon spread to other conglomerates. In September 1987, in the face of escalating violence and continued appeals from the conglomerates, the police were finally mobilized, cracked down, and instilled order. The militant 109-day stand-off at the Hyundai complex eventually was ended by kusadae with the help of a 14,000-strong police force to rout the workers inside.

Unlike before, however, the state began to show increasing signs of reluctance in engaging in direct suppression until the point when the economic costs and the labor threat became ‘intolerable,’ marking a turning point in the state's strategy toward the labor sector (Eder, Reference Eder1997: 25–26). The initial inaction by the state despite its capacity to suppress the strikes and the unions' unlawful behaviors prompted management to add another layer of protection in addition to the kusadae squads: recruited thugs to be utilized as needed against unruly labor. The use of kusadae soared as the number of disputes increased, and the violence exercised by official security companies like SECOM, a Samsung subsidiary, against workers in the Samsung Heavy Industry or by hired thugs as in the case of the Knife Terror Incident (sikkal t'erǒ sakǒn) against union leaders at Hyundai Heavy Industries also increased (Kim, Reference Kim2004: 225–236). Now kusadae and hired security, including professional union-busters, became the main coercive elements on the front lines of labor suppression (Asia Watch, 1990: 55; Ogle, Reference Ogle1990: 122–153; Hankyoreh, 19 January 1989: 3). In particular, the rapidly corporatized organizations – many of which were operating outside of, and thus theoretically in competition with, the legal apparatus, estimated to be around 350 groups with 4,300 members (in 1990) nationwide – were proved to be the major source of violence (Dong-A Ilbo, 23 June 1990: 3).

2.3 The growth of civil society and clouding of state violence

Since the late 1980s, the demands of workers went beyond economic concerns and focused more on the right to establish democratic and independent unions, i.e., the ‘democratization of the workplace’ (Kim, Reference Kim2000: 94). The government did not want to tarnish its new image as the progenitor of democracy through the visible mobilization of the police force in the suppression of labor resistance. In other words, the last general-turned-president Rho, as the greatest beneficiary of the past authoritarian regimes, was in fact limited in what he was able to do (Lee, Reference Lee, Diamond and Shin2000: 285). The subsequent Kim Young-sam administration (1993–1998) also had to frequently apologize for the excessive use of violence against labor, particularly when the suppression involved civil society organizations (Dong-A Ilbo, 6 July 1994: 29). Accordingly, the policing protest style changed from authoritarian tactics of mass arrests and total blockage to isolating core and radical actors, since the former became no longer politically feasible (Kim, Reference Kim2017).

Thus, amid the democratizing environment since the late 1980s, the labor sector resorted to illegal and militant protest tactics in order to politicize the issues and trigger the government's intervention (Yi et al., Reference Yi, Cho and Yi2005: 18). The persistence of labor's unlawful repertoires was reinforced by the confrontational legacy of protest against the state during the authoritarian era and the militant unions' strong performance in bargaining particularly after democratization (Yoon, Reference Yoon2005; EAI, 2008), which had the government face challenges both from the militant and politicized labor and from the dissatisfied developmental partner, i.e., the business sector. The labor sector's contentious behavior along with the growth of civil society changed – a phenomenon which Chang and Vitale (Reference Chang and Vitale2013) called – the ‘repressive coverage’ of the state.

Under this circumstance, the state's response was twofold. On the potentially politicizable disputes, the government augmented its force to monitor and pre-emptively suppress them. The Headquarters of National Security dispatched police officers from Anti-Communist and Intelligence bureaus to all companies with more than 200 employees in order to root out outsiders' intervention including college students and radical leftists (Dong-A Ilbo, 11 September 1987: 11). On the purely economic disputes, contrarily, the Minister of Internal Affairs announced that the police would intervene only: (1) when fatalities had incurred; (2) in cases of arson or extreme vandalism; and (3) when the management requests interference for ‘extended illegal’ strikes (Dong-A Ilbo, 30 December 1988: 2). However, it does not mean that the state's repressive capacity was weakened since the size of the mobilized law enforcement force was getting larger, and the state was still autonomous from the business sector's pressure on labor-related issues (Chŏn, Reference Chŏn1994).

Meanwhile, the middle class, which had been supportive of the early labor movement during the authoritarian period, was gradually turning away due to labor's increasing militancy. At the same time, the ruling elite needed to ensure the support of the middle class which had become the new legitimizing force (He, Reference He2019), and in doing so, had to break any cross-class alliance. On-going violent and unlawful clashes following democratic elections began to create a negative image of labor and the perception that the movement had lost its ‘moral authority’ (Ogle, Reference Ogle1990: 129).Footnote 14 Furthermore, there was a visible shift in the middle classes' attitude toward labor in the face of real or perceived threats to economic or political stability – events which could easily be spun by the government-friendly media as being a result of frequent labor disputes (Oh, Reference Oh1999: 114). While the labor sector remained significantly underrepresented and marginalized in party politics even after the consolidation of electoral democracy (Mobrand, Reference Mobrand2019), large-sized advocacy organizations including the Citizen's Coalition for Economic Justice also stated that they would be committed to peaceful social change, showcasing the new wave of civil society associations espousing non-violent means of social movement (Koo, Reference Koo and Armstrong2002: 119).

The observable implications of this political shift can be seen in the changed contour of labor suppression in Korea. While the government took a hands-off approach to the labor unrest, employers did what they could to suppress union activities including bad faith collective bargaining, establishment and registration of ‘yellow’ sweetheart unions, and the use of thugs to break up strikes (Alemán, Reference Alemán2010: 86). Private security service companies (PSSCs, sasŏl kyŭngbi yong'yǒk hoesa) as organized and outsourced kusadae have their start in the same tumultuous period (Asia Watch, 1990: 61–62).

To distance themselves from the authoritarian past, through a series of reforms of Korea's justice system including its coercive element, post-democratization regimes implemented measures to increase civilian oversight, which substantially decreased the autonomy the state once enjoyed. Tactics as well changed, especially so during the first progressive Kim Dae-jung administration (1998–2003). Under Kim, a long-time advocate of democracy, the National Police Agency launched Operation Grand Reform, which included two tactical changes: (1) the use of tear gas was to be significantly limited and then abolished, and; (2) all-female police squadrons were to be established to supervise demonstrations (Moon, Reference Moon2004: 129).Footnote 15 Consequently, while 210,000 canisters of tear gas were shot in 1996, only 4,820 in 1998, and finally zero in 1999 (Hankyoreh, 22 October 1999: 27). However, behind the female police officers are the riot police in place and ready to act if violence spills over pre-determined areas – e.g., into the view of non-protesting civilians (Kwon, Reference Kwon, Shin and Chang2011: 66).

2.4 Labor suppression in the neo-liberal era

The neo-liberal transformation of society rapidly marched on under both progressive and conservative regimes, particularly after the financial crisis in 1997. The state's control over labor was still predominantly repressive as demonstrated by the larger number of imprisoned trade unionists under the Kim Dae-jung administration (722 unionists) than that of the previous Kim Young-sam administration (632 unionists) (Chang and Chae, Reference Chang and Chae2004: 439). However, the state kept the violence perpetrated by kusadae or PSSCs away from the public view – with the police assuming the coordinating role of preventing escalations of conflict.

Under the state's implicit toleration, breaking strikes and union busting were now behind the corporate veil. In the early 2000s, hundreds of PSSCs mushroomed and competed to obtain contracts with companies in labor disputes. Many of them thrived including the Changjo Consultants, established by a former employee of the Korea Employers Federation (KEF) (Hankyoreh, 11 May 2011: 3). While 91.3% of workers and squatters charged with illegal disputes were indicted between 2010 and 2011, only 40.3% of PSSC employees charged with illegal behavior were finally indicted during the same period (Anti-PSSC, 2012: 62; see also Pak and Myŏng, Reference Pak and Myŏng2014).

As the neo-liberal reform of the labor market legalized the dispatching of workers, which resulted in the growth of non-regular employment contracts with poor compensation, unstable tenure and surging industrial tensions (Lee, Reference Lee2015), the PSSCs claimed that they would provide a pro-employer workforce to the companies of prolonged labor disputes to end the strikes, and would ‘free the employers from the burden of managing industrial relations’ (Pressian, 2 August 2012). The labor's militant – mostly illegal – activism and the management's legal but at times extra-legal responses escalated and prolonged the violent confrontation in workplaces (Song and Kim, Reference Song and Kim2014).

In the mid-2000s, ironically during the progressive Roh Moo-hyun administration (2003–2008), such private contractors boomed (Table 1) including the ‘Big Three’ (CJ Security, Marine Cops, and Contactus), established in 2002, 2005, and 2006, respectively (OhmyNews, 8 August 2012). The Marine Cops was mobilized to suppress the 76-day work-in-strike at SsangYong Motor Company in 2009 and the CJ Security interfered with Hanjin Heavy Industries in 2011 – amid the epic 309-day areal protest of workers against lay-offs – to drive off the workers (Hankyoreh, 30 June 2011; Goldner, Reference Goldner2009). The largest was Contactus, a PSSC, which was alleged to have strong ties and connections to both the conservative president Lee Myung-bak (2008–2013) and members of his ruling Saenuri Party (Korea Times, 12 August 2012). Unionists of companies including Valeo Automotive, Yoosung Enterprise, Sangsin Brake, Mando Corporation, and the SJM – which appeared in the article's beginning – fell prey to its hardnosed violence (Ryu, Reference Ryu2019). The Korean Metal Workers Unions (KMWU) publicized the violence by the security companies and non-action by public authorities while an official at Contactus stated that ‘[w]ithout us, business activity will wither and there will be a burden on government authority’ (Kyunghyang Shinmun, 1 August 2012). The reported violence by PSSCs reached its peak during President Lee's term (Kim, Reference Kim2012).

Gradually the state has moved away from active engagement in strike suppression toward managing and containing violence. In place of the riot police, who remain mobilized and present, are PSSCs and kusadae who carry out the suppression. By operating under the façade of de-militarization, they help the state avoid the politicization of social contention. To be underscored again, the government has maintained its police forces to effectively respond to the growing dissidents from civil society throughout the 2000s. Table 2 and Figure 3 demonstrate that the Korean police maintained consistent suppression capability through those years. With this, old tactics of direct suppression have often been revived as occasion necessitates (Shin, Reference Shin2012: 304).

Table 2. Police suppression rates to popular unrests, 1995–2004

Source: Kim (Reference Kim2005: 76).

In short, as one labor activist notes, ‘controlling labor through service companies is good for all, i.e., the police, the employers, and the companies themselves, [because] the police can have their hands clean and the employers can be free from responsibilities, while the service companies earn substantial profits’ (Cho, Reference Cho2006). The annual sales of Contactus leaped from 672 million won (approximately US$600,000) in 2008 to 2 billion won (US$1.8 million) in 2010 (Kyunghyang Shinmun, 4 August 2012). Contactus was ready to mobilize 300–3,000 personnel at a time, armed with riot control vehicles, water cannons, canine units, and surveillance drones (Democratic Unified Party, 2012: 33). Major Korean manufacturing firms signed contracts with various PSSCs to break strikes and disrupt union activities (see Table 3). They even filed civil lawsuits against unions for the cost of PSSC contracts, in addition to damage compensation (Eom, Reference Eom2012).

Table 3. Major strike breaking incidents of manufacturing firms by PSSCs in 2009–2011

Source: APT (2012: 66).

As a result of democratization and the advancement of the rule of law, the labor sector's traditional practices of unlawful and violent protests became less effective, whereas the management and the PSSCs were filing dispossessive litigation and pressed criminal charges against labor. The state's law enforcement, under this circumstance, played a pivotal role and the embedded developmentalist thrust forces the state to take a pro-business stance, while cognizant of societal sensitivities. The progressive Roh government maintained that ‘police intervention in labor disputes should comprehensively consider the aspect of unlawful behaviors, the urgency of the situation, and its impact on the national economy’ (Pak et al., Reference Pak, Hwang, Pak and An2009: 127–128, emphasis added), and the subsequent conservative Lee government also announced the ‘Advancement of Demonstration and Protest Practices’ (chipheosiwi sŏnjinhwa) for ‘the improvement of national image, foreign investment, and job creation’ (National Police Agency, 2008).

Upon the inauguration of President Park Geun-hye (2013–2017), yet another conservative, the employers asked the government to implement rule of law in the workplace, preclude politicization of labor disputes, and, incongruously, avoid excessive interference with industrial relations (KEF, 2013: 4–5). The Park government continued underscoring voluntary industrial relations (nosajayul) and lawful bargaining (chunpŏpgyosŏp) while pushing through a series of neo-liberal labor reform packages including the loosening of lay-off conditions and extending of minimum terms for temporary employment, which made the demands of the workers in disputes illegal (No, Reference No2014).Footnote 16 Although the blatant violence of PSSCs declined due to the revised Security Services Industries Act in 2013Footnote 17 and the political pressure for police intervention (Hankyoreh, 27 September 2016: 12), however, labor disputes, particularly in small-and-medium-sized firms, have been mainly handled by PSSCs contracted with employers who want to avoid direct negotiations with the protesters while responding to them with dispossessive litigation (Lee, Reference Lee2021).Footnote 18 The number of lawsuits employers filed against unionists increased continuously, and 10.3% of them experienced physical violence by the company (Pak et al., Reference Pak, Choi, Kim, Yun and Pak2020).

Along with the prosperity of PSSCs, coincidentally, the unionization rate of Korean workers has continuously dwindled, even under the progressive Moon Jae-in government, as demonstrated in Figure 4. While the organization rates of regular workers have slightly increased, that of non-regular workers dropped to 0.7% in 2019, a historical low. With such dismal organization rates, non-regular sectors have remained fragmented and precarious for higher labor flexibility, resulting in growing potential contention of workers seeking job security and income stability (Shin, Reference Shin2013; Lee, Reference Lee2015).

Figure 4. Unionization status of non-regular workforce in Korea, 2006–2019.

Source: National Statistics Office.

Unionization and employment type have been the major factors determining wage levels in Korea after the neo-liberal transformation (Chŏng and Nam, Reference Chŏng and Nam2019), and employers have thus been incentivized to suppress labor in order to keep the organized workers at bay. The growing discontent among workers has translated into the rising number of labor disputes through the 2010s – both in large-sized and small-and-medium-sized firms but slightly steeper in the latter – as illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Labor disputes in Korea, 2011–2019.

Source: National Statistics Office.

While the state is forced to respond to the large-scale collective actions of the organized labor represented by both the moderate/conservative FKTU and the progressive Korea Confederation of Trade Unions (KCTU), it does not want to be involved with the labor disputes against the desperate prolonged struggle of non-regular – and/or laid-off regular – workers, who tend – and had no choice but – to resort to radical and militant struggles in order to politicize their causes (Cho, Reference Cho2011). Although most irregular workers join the KCTU rather than the FKTU, the large and influential KCTU affiliates are generally reluctant to represent them, leaving the non-regular sector in the gray zone of private violence, where many PSSCs file punitive damage claims, causing protest suicides (Chang, Reference Chang, Lim and Alsford2022: 167–168). The number of long-drawn-out protests has soared through the 2010s and, as of 2019, there were 35 workplaces with 7,000 laborers protesting for protracted time as long as 13 years (Doucette, Reference Doucette and Gall2013: 225–227; KMWU, 2019).

3. Discussion and conclusion

The state, whether being democratic or authoritarian, pursues power and legitimacy while minimizing the use of violence. Korea under authoritarian rule, due to the lack of political legitimacy, had to resort to the exercise of violence to legitimize its rule by fostering economic growth, which in turn, was used to justify the use of violence. This dialectic spiral came to an end due to the democratic pressure by the middle class, ironically built on the success of authoritarian growth, which required the violent suppression of labor. While the state was making effort to co-opt the middle class, meanwhile, the labor sector was expanding its militant protest repertoires, oftentimes unlawful and violent, against the state and the business sector throughout the authoritarian and post-democratization era, necessitating the repressive coverage of the state and the business. The developmental coalition of the state and business in the export-oriented industrial economy thus has evolved into contracting out the labor suppression to the violence specialists amid neo-liberal dualization of the labor market. Thus, going back to Figure 1, public forces of enforcement have not disappeared but increasingly act through private proxy. In turn, such implicitly, and at times explicitly, tolerated and contracted violence is often illegal – in terms of domestic statutes – in nature, further making this outcome puzzling in terms of expected effects of development and democratization.Footnote 19

Conventional accounts of the persistence of labor suppression in Korea have largely focused on state collusion or capture, which have limited explanatory power on the changing features of policing the labor. The neo-liberal approach, which underscores the changes of industrial structure and employment market situation after the financial crisis in the late 1990s and the imposition of neo-liberal policies since then, while it provides an apt explanation of the strengthened power of the capital class vis-à-vis fragmented and weakened labor sector, does not sufficiently factor in the changes in regime characteristics, i.e., democracy, and the state's normative calculus of using repression, i.e., political violence. Thus, while states operating under a developmentalist model in many respects base their legitimacy upon continued or expanded economic growth through heavy-handed government intervention, they must carefully calculate the types of intervention given the regime type – i.e., the quality and extent of democracy or not – they are embedded within. We refer to this, as the embedded developmentalist approach.

With respect to political violence, Davenport (Reference Davenport1995) demonstrates that the state's perception of threats from society varies in many dimensions, and the regime type, particularly democracy, significantly affects the state's repressive behavior. As discussed, the level of political violence has significantly decreased after democratization in Korea but it has persisted in new and varying ways, implying that political violence does not simply negatively correlate to the status of liberal democracy. This strange persistence of violence in Korea is indeed more puzzling considering the regime characteristics of the Moon Jae-in government, which branded itself as an ‘offspring of the People's Candlelight Revolution’ that ousted the corrupt and illiberal Park government. President Moon (Reference Moon2018), in the first Labor Day message since his inauguration, said that ‘the new administration would uphold respect for labor as a key administrative priority’ and pledged to build a country ‘where labor is not neglected and insulted by institutions or by people in power.’ The Moon government installed the Committee for Employment and Labor Administration Reform (CELAR), which did propose reform measures to correct the anti-labor practices including the illegal as well as extra-legal suppression of union activities by employers including the use of PSSCs (CELAR, 2018). However, anti-labor violence has not disappeared and has in fact become more persistent amidst the COVID-19 pandemic along with the continuing government's inaction (KCTU, 2020). Indeed, many political and economic practices established during the authoritarian era have survived the social upheavals including the democratic transition, the financial crisis, and its ensuing neo-liberal transformation (Mobrand, Reference Mobrand2019; Hockmuth, Reference Hockmuth2021). The embedded developmental approach has also survived to exercise non-democratic coercion in a palpable time of popular democracy.

While this study has sought to explain the puzzling case of persistent yet dynamic labor suppression in Korea, we have also sought to utilize Korea as a vehicle for contributing to the generalizable understanding of state-development in the area of policing and political violence, both public and privately sourced, coupled with the effects of democratization. Mainly, political violence ubiquitously evolves according to dynamic socio-political environments and varying tasks of the state. While we may still assume a state-based preference for monopolization over the means and use of violence, such varying political environments at times may force states to engage in complex relationships with non-state specialists in violence. Such relationships and emergence of niche markets for private violence in the wake of democratization have been to date under-theorized.

Finally, our theoretical findings and implications go beyond both the narrow case of state–non-state collaboration in the market for force and labor suppression, as well as beyond the Korean context. An expansion and testing of such cases however, remains beyond the scope of this article, and will be addressed in future research projects.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the participants of the V-Dem Workshop on Contentious Politics in Asia for comments and suggestions, and in particular, Mark Thompson, Hans Tung, Jai-Kwan Jung, and Kenneth McElwain. They also greatly appreciate helpful comments from Allen Hicken, Myung-koo Kang, Charles Crabtree, Gill Steel, and the anonymous reviewers.

Financial support

This study was supported by grant no. KHU-20180850 (Kyung Hee University).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare none.