INTRODUCTION

The questions of how and why early medieval monasteries were organised have been a subject of intense debate amongst archaeologists, historians and theologians. This article seeks to throw new light on these questions through a detailed discussion of the early monastery on Iona, one of the most important ecclesiastical centres of northern Europe, which, despite its apparently remote location, played a leading role in intellectual life during the period after its foundation by the Irish monk Columba (known in Gaelic as Colum Cille, the ‘dove of the Church’) around ad 563.

In early Christianity Jerusalem was of central importance not only as the site of key incidents in the life of Jesus Christ, and as the contemporary site of the holy places and relics associated with his life, but also as a symbol for the ‘New Jerusalem’ of heavenly salvation.Footnote 1 While this concept of a world view that permeates theological and art historical discourse has been widely discussed, it has not previously been applied in an archaeological context. Iona is one of the key places where it is possible to investigate the application of this idea to the physical layout and monumentalisation of a monastery.

The writings of Abbot Adomnán on Jerusalem give us a unique insight into the world view of Insular ecclesiastics at the end of the seventh century, and enable us to compare these ideas with the archaeological evidence for Iona. The nexus of novel practices that we can see developing at this time, embracing ideas of monastic enclosure, pilgrimage, the cult of saintly relics and their enshrinement, the creation of lavishly decorated illustrated manuscripts, new mortuary practices and monumentalisation through sculpture, represent a key shift in religious praxis. Understanding how these practices were embodied on the ground is crucial to our appreciation of other early monasteries, many of which have been investigated by archaeologists in recent years. The large-scale investigations on Iona carried out by Charles Thomas from 1956 to 1963 were central in developing his influential ideas on the evolution of monastic practice, particularly with reference to the monastic vallum or enclosure, but they were never published. This article builds on the data from these excavations, reconstructed from recently recovered excavation archives, supplements them with new radiocarbon dates and integrates the findings with numerous other excavations on the site, totalling around 150 separate trenches. Rather than a conventional excavation report, this article seeks to integrate the main results of the excavations with new ideas on early Insular monasticism put forward by scholars such as Éamonn Ó Carragáin, Tomás Ó Carragáin, Thomas O’Loughlin and David Jenkins.Footnote 2

UNDERSTANDING EARLY MEDIEVAL INSULAR MONASTERIES

The question of how early medieval Insular monasteries were conceived in the minds of early ecclesiastics, and how they were laid out and organised on the ground, has received much attention in recent years from historians, archaeologists and theologians, with the sacred topography of the Columban monastery on Iona playing a key role in many of these discussions. A number of different research questions intersect (and entangle) in these studies, with vigorous debate around issues of regional difference, the origins and trajectories of monastic organisation in a European context, definitions of monasticism and the proposed ‘proto-urban’ functions of some ecclesiastical centres.

With respect to the issue of regionality, there is a long tradition of seeing monasteries in the Celtic-speaking areas as being differently organised from other Insular monasteries, particularly in their characteristically circular enclosures.Footnote 3 This characteristic feature has been entangled with notions of a ‘Celtic Church’ being somehow separate from mainstream Christianity, an idea that has itself been robustly disputed, though the concept of a Celtic Church nevertheless retains a strong non-academic following.Footnote 4 The notion of a uniquely Irish monastic layout pattern consisting of concentric circular enclosures, based on sites such as Nendrum, has explicitly influenced interpretations of Scottish sites such as Whithorn and Dunning, even where there is little archaeological evidence to support the reconstructions.Footnote 5 The concomitant idea that the Irish Church was organised on an abbatial, rather than episcopal, basis has been effectively undermined by historians, though differences of interpretation remain.Footnote 6 Another supposedly distinctive feature of the pre-Norse Irish monastery was its ‘proto-urban’ character, first proposed by Charles Doherty, but the concept has been critiqued for Ireland, and more widely.Footnote 7 However, there is no doubt that Irish monasteries played a significant role in economic development, even in the pre-Norse period, with evidence of large-scale production of both ecclesiastical and secular objects.Footnote 8

The question of how to define early medieval monasticism and how to recognise a monastic, as opposed to other types of ecclesiastical settlement – or, indeed, secular settlement – has exercised archaeologists in particular, and different defining elements have been proposed.Footnote 9 Faced with sites without historical documentation, such as Portmahomack, Flixborough and Brandon, some have been reluctant to characterise these as monastic, though others are less sceptical about the extent of undocumented monasticism.Footnote 10 However, it is increasingly being realised, especially in Ireland, that the indiscriminate use of the term ‘monastic’ for all ecclesiastical settlements is not helpful. Study of the historical sources and the terminology used of their officials has shown that ecclesiastical settlements had a mixture of monastic, episcopal, pastoral and economic functions.Footnote 11 There are also difficulties in distinguishing in the sources what some writers term ‘para-monastic’ dependants from ‘real’ monks, both termed manaig in the sources.Footnote 12 There is a growing acceptance that there was a range of types of site, including monastic possessions with proprietorial, hereditary and parochial churches or burial grounds, as well as hybrid sites such as the recently recognised group of non-ecclesiastical ‘cemetery settlements’.Footnote 13 The theological basis for enclosure has also been much discussed – from Doherty, who proposed the monastery as a Levitical ‘city of refuge’ (civitas refugii), to MacDonald, who applied the concept of increasing holiness of concentric enclosures to Iona, and most fully by theologians O’Loughlin and Jenkins, who centre their work on Iona and the writings of Adomnán.Footnote 14 All these authors suggest that Adomnán, Columba’s biographer and the ninth abbot of Iona, was a key figure in developing the notion of a monastery as a metaphor for Jerusalem, both as it had been in the past (as the site of incidents in the life of Jesus), the present (the layout, shrines, relics and rituals associated with the Church of the Holy Sepulchre) and the future (salvation in the heavenly Jerusalem). Ó Carragáin also sees Iona as the key site in developing and transmitting these ideas to Ireland.Footnote 15

One major problem with much of this discussion is that it has largely been based on literary rather than archaeological evidence, as so few sites had been excavated to a great enough extent to make ground-truthing meaningful. However, in recent years there has been a great expansion in our knowledge of early ecclesiastical sites, especially those in northern Britain, with the full publication of excavations at Portmahomack, Whithorn, Hoddom, Inchmarnock, the Isle of May, St Ninian’s Isle, Monkwearmouth/Jarrow and Glastonbury.Footnote 16 In Ireland, Tomás Ó Carragáin’s magisterial work on early Irish churches provides a comprehensive corpus of comparative material, and can be supplemented by recent work on enclosures in Donegal by the Bernician Research Group and summaries of more recent work.Footnote 17 It is in this context that Charles Thomas’s excavations of 1956–63 on Iona have particular relevance, especially as the detailed documentary evidence leaves no doubt that Iona was indeed a coenobitic monastery rather than another kind of ecclesiastical site. The results of these excavations are interpreted and their significance explained here, with the full details available elsewhere.Footnote 18

IONA: THE BACKGROUND

Although well connected by sea routes that brought goods from as far as the Mediterranean, early medieval monks considered Iona to be as far from Jerusalem, the conceptual centre of their world, as it was possible to be, lying, as they described Iona, ‘at the edge of the Ocean’ and ‘at the limit beyond which no-one dwells’.Footnote 19 This perceived remoteness was important to early ecclesiastics, as their mission to this remote outpost could be presented as signifying the triumph of Christianity over the whole of the known habitable world.Footnote 20 The surviving products of Iona include decorative sculpture, illustrated manuscripts and literary works. Iona has the largest collection of early medieval sculptured stone monuments in Britain and, in the free-standing high crosses of St John and St Martin, some of the outstanding European sculpture of the period. It has been proposed that Iona was the origin of the ringed cross, perhaps the most iconic of ‘Celtic’ artefacts.Footnote 21 Illustrated manuscripts were also produced there: the Cathach is one of the oldest surviving Insular manuscripts, probably written in Columba’s own hand; the magnificently decorated Book of Kells is widely considered to be an Iona product; and it has been argued that the Book of Durrow may also have been made on Iona.Footnote 22 The decoration of the manuscripts and sculpture shows an explosion of creativity here in the period around the eighth century. Unlike in Continental Europe, there was little investment in stone architecture before the Romanesque period, with most church buildings being of organic materials. However, Ó Carragáin has suggested that St Columba’s chapel on Iona could be the proto-type of other stone-built shrine chapels with antae, possibly dating to as early as the mid-eighth century.Footnote 23

While the influence of Iona as an important locus for the development of the Insular art style within Britain and Ireland is generally acknowledged, the island’s wider significance in terms of discussions of European art have tended to be sidelined and characterised as a peripheral dead-end.Footnote 24 However, the intellectual products of Iona were widely known throughout north-western Europe and recent scholarship has emphasised the role of Adomnán, the ninth abbot of Iona, especially in developing ideas of the monastery as an earthly manifestation of the heavenly Jerusalem in his De Locis Sanctis, and in his Vita Columbae, both written on Iona in the late seventh century.Footnote 25 O’Loughlin has argued strongly that De Locis Sanctis had significant influence throughout northern Europe, both in itself and through Bede’s shortened version of the text.Footnote 26 This work was not merely a geographical guide, but a sophisticated discourse on scriptural exegesis that grappled with the problems raised by discrepancies among the Gospels. It also gave detailed descriptions of the various structures around the tomb of Christ, including one of the earliest ground plans of buildings from the medieval period. This article will suggest that this was influential in trying to establish a schematic norm for church layouts. Adomnán’s best known work today, the Vita Columbae, gives a great deal of detail of daily life on Iona in the later seventh century, more than any other contemporary saint’s life.Footnote 27 There have been several previous attempts to relate the elements found in the Vita to the archaeological remains, though these were all undertaken without access to the results of Thomas’s extensive excavations.Footnote 28 A further product that has been attributed by some to Iona is the early eighth-century Collectio Cannonum Hibernensis, which was the first attempt to codify church law into one coherent format and was widely distributed in northern Europe in the eighth and ninth centuries.Footnote 29 Jenkins and others have argued that it was the biblical model of the Temple of Ezekiel at Jerusalem that influenced Irish views on monastic layout. While the authors accept that this model was important in the form of church buildings and theological discourse, it will be argued below that the layout of the structures associated with the Church of the Holy Sepulchre was a more influential model at Iona.Footnote 30 Iona was also one of the earliest monasteries in Europe to produce annals – yearly accounts of major events – with the putative ‘Iona Chronicle’ forming the earliest strand of the ‘Chronicle of Ireland’ contained within the Annals of Ulster and Annals of Tigernach.Footnote 31 These annalistic entries were contemporary from at least the mid-seventh century, and possibly as early as the late sixth, again giving a unique insight into events on and around Iona.Footnote 32 This unusual abundance of historical documentation makes Iona an ideal site to investigate how theoretical concepts of monastic layout were embodied in the actual archaeology of a site, something not possible at any other contemporary site.

Despite its undoubted importance, Iona has been poorly treated by archaeology, with numerous ad hoc excavations of varying quality and degree of publication. In particular, a series of excavations carried out by the late Charles Thomas from 1956 to 1963 remained mainly unpublished, with only brief interim notices and an account of the excavation on Tòrr an Aba giving any indication of what had been found.Footnote 33 Many other interventions have been the result of the restoration of the Benedictine monastic buildings from the late nineteenth to mid-twentieth century, later modifications to these buildings, which are a living and working environment for the Iona Community, and to cater for the large tourist audience. O’Sullivan has rightly criticised this situation, stressing that there has been no research programme associated with the work and that the small-scale nature of these interventions has precluded any understanding of structural development and chronology.Footnote 34 This article is an attempt to rectify part of the situation by analysing the results of Thomas’s excavations for the first time, integrating the results with other monastic excavations, and developing new ideas on monastic organisation.

Charles Thomas (1928–2016) was one of the leading figures in the development of early medieval, and especially early Christian, archaeology, though his interests were exceptionally wide-ranging.Footnote 35 His seminal books include The Early Christian Archaeology of North Britain, Britain and Ireland in Early Christian times ad 400–800 and Christianity in Roman Britain to ad 500.Footnote 36 In these books the Iona excavations can be seen to have influenced his thinking on subjects such as the layout of monasteries, shrines and the cult of relics to an extent that was not apparent until the archives were investigated. Professor Thomas, with typical generosity, enthusiastically supported the authors’ publication of these excavations, providing the authors with finds, plans, diaries and other archive material, but sadly died just as the first phase of publication was completed and so was unable to comment on the authors’ readings of the evidence. The authors have also consulted extensively with the surviving members of Thomas’s team, who were able to contribute verbal and photographic evidence.

THE SETTING OF THE EARLY MONASTERY

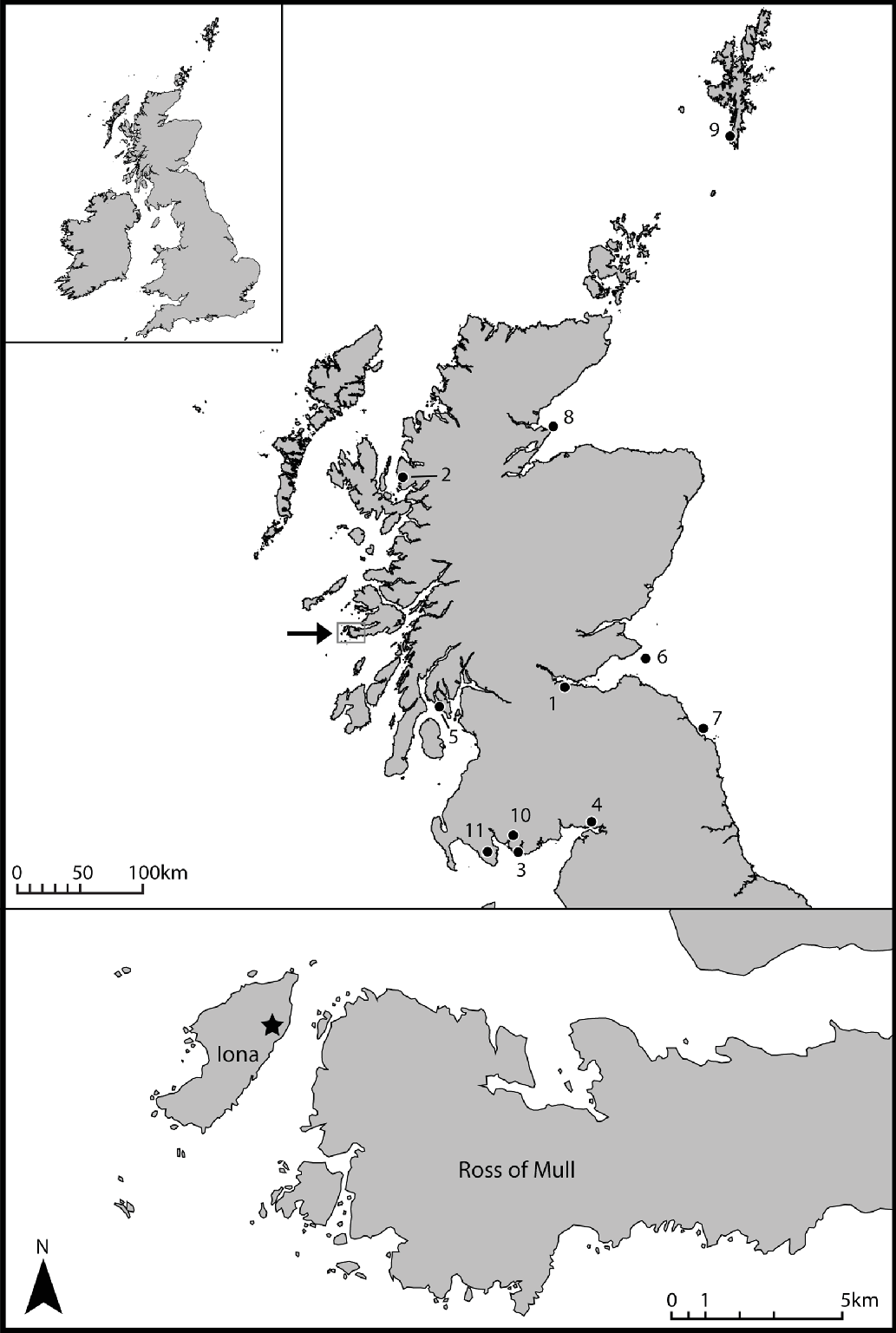

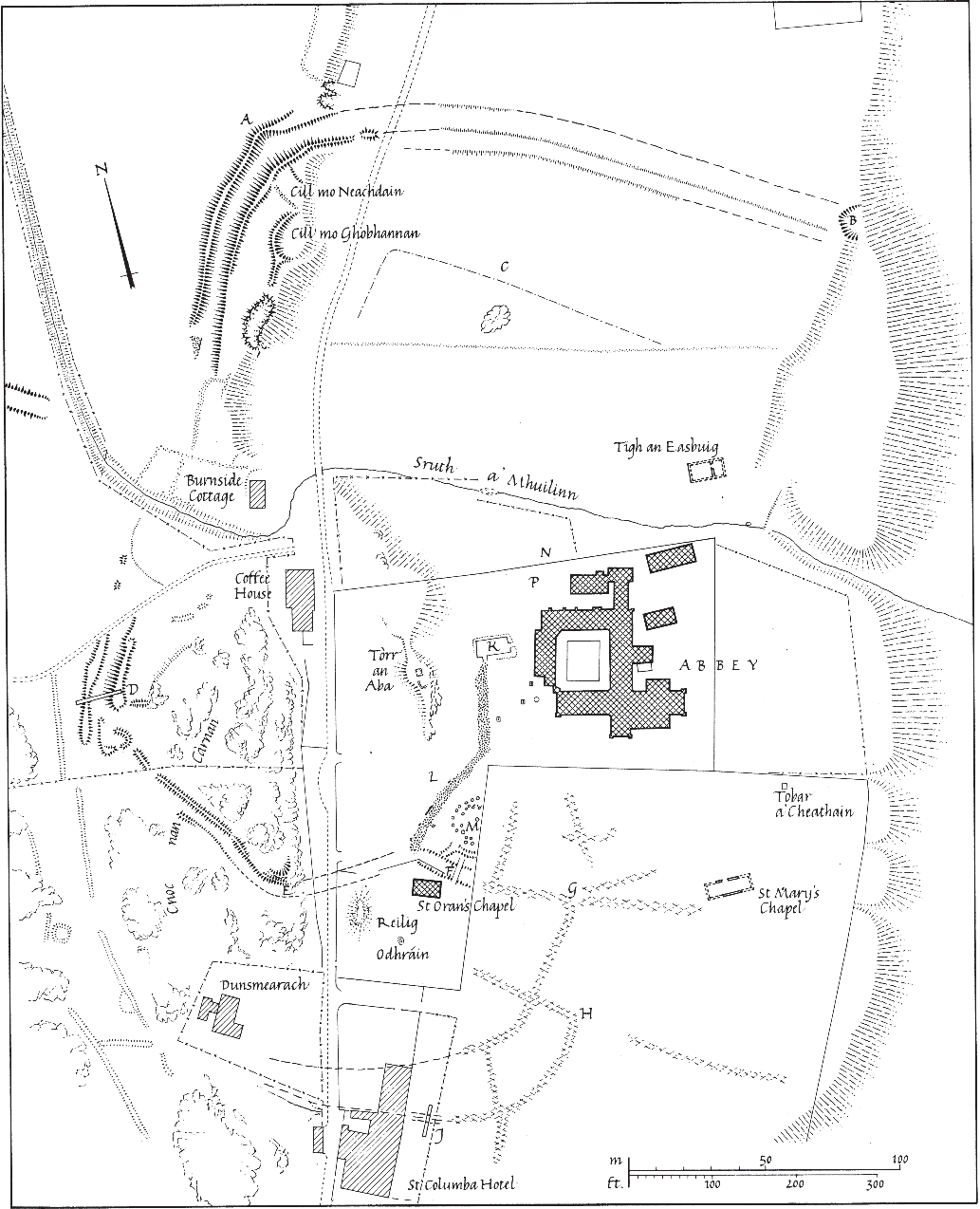

Iona Abbey (NGR NM 2868 2452) is situated on the eastern side of Iona, a small island lying off the western coast of Mull, in the Inner Hebrides of Scotland (fig 1). The abbey lies on raised beach deposits of the Late Devensian period, here at an elevation of around 20m od. The medieval abbey buildings occupy a fairly flat-lying part of the terrace, but the ground rises to the north west and includes a rocky knoll, Tòrr an Aba, a key place in the interpretation that follows that lies just west of the abbey buildings, and another lower rock outcrop in the adjoining Reilig Odhráin graveyard. Towards the west of the site there is a rocky cliff bounding more hilly terrain, Cnoc nan Càrnan; unusually for monastic sites, which are normally located on flat-lying ground, this section of upland lies within the enclosed area (fig 2). These rocks are the easternmost extent of the Lewisian basement gneisses that form most of the bedrock of the island. The natural deposits of the raised beach consist of orange sands and gravels, sometimes with decayed granite boulders, which in places are cemented with iron-panning causing poor drainage. Attempts to control these drainage problems can be seen in many of the excavations. A series of substantial stone-lined drains have been encountered in many parts of the site, usually running north west–south east, which before the recent radiocarbon dates were obtained (see below) were believed to have been associated with the building of the Benedictine abbey that commenced around ad 1200.Footnote 37 The natural deposits have been described in detail elsewhere, as has the general setting, and will not be repeated here.Footnote 38 The abbey, along with the Reilig Odhráin graveyard and the wider area enclosed by the vallum, is a Scheduled Monument (SM no. 12968) in the care of Historic Environment Scotland since 2000, but owned by the Iona Cathedral Trust and occupied by the Iona Community for use as a residential spiritual centre. The surrounding land and most of the island is mainly owned by the National Trust for Scotland.

Fig 1. Location of Iona Abbey (starred) and other sites mentioned. 1) Abercorn, 2) Applecross, 3) Ardwall, 4) Hoddom, 5) Inchmarnock, 6) Isle of May, 7) Lindisfarne, 8) Portmahomack, 9) St Ninian’s Isle, 10) Trusty’s Hill, 11) Whithorn. Source: Heather Christie.

Fig 2. Detailed plan of Iona Abbey. Source: © Crown copyright: Historic Environment Scotland.

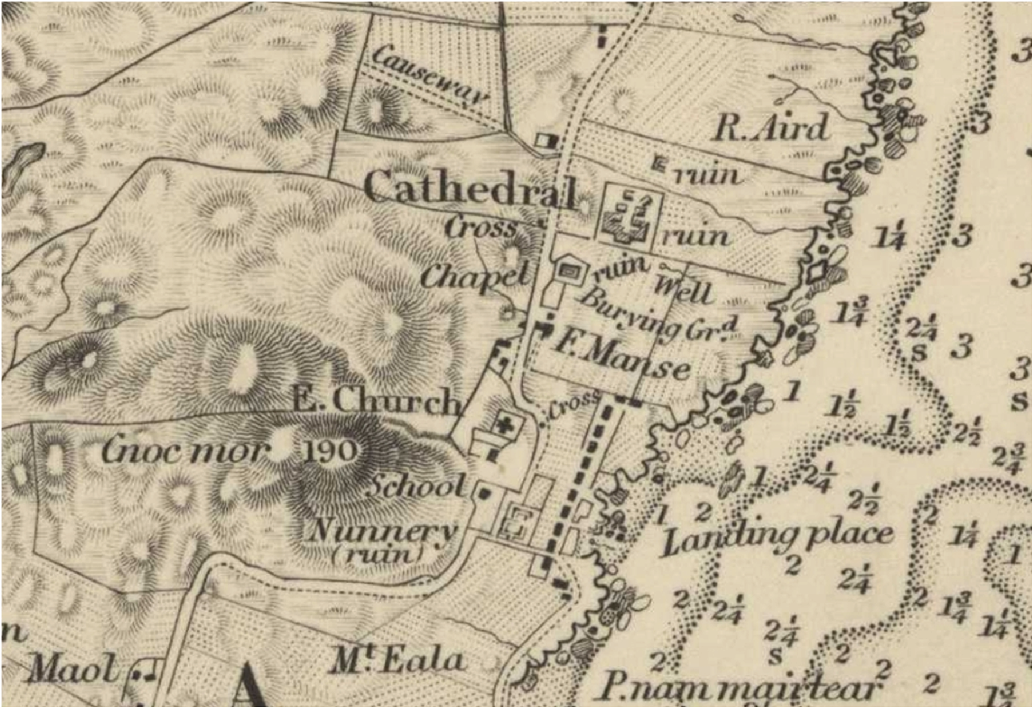

All of the trenches opened by Thomas lay within the area of the early medieval monastery as defined by its vallum or enclosure, which had been previously located by the survey of upstanding earthworks.Footnote 39 The area within these bounds has been affected by significant changes in landholding and agricultural regimes since the Benedictine abbey fell into disuse in the mid-sixteenth century, and the enclosure walls have been repeatedly moved and reconstructed. The earliest mention of enclosures is in Dean Munro’s account of the Western Isles in 1549, where he describes the Religoran (‘the burial ground of Oran’) graveyard as ‘ane fair kirkzaird, well biggit [built] about with stane and lime’.Footnote 40 This is important as the only pre-Reformation account of the medieval monastery, and shows the Reilig Odhráin was already a separate enclosed burial ground at this period. The earliest estate map (1769) shows the rectilinear stone wall that was erected around the core of the ruins in the 1750s by the Duke of Argyll’s tenants (fig 3) following concern by prominent visitors about the pillaging of the ruins.Footnote 41

Fig 3. Estate map of 1769 by William Douglas for the Duke of Argyll, showing rig and furrow cultivation areas around the abbey ruins, the ‘Street of the Dead’ coffin road and the dispersed village houses. Source: © Historic Environment Scotland.

It is not known if this wall was a rebuilding of an earlier Benedictine phase enclosure or an entirely new one, but archive photographs suggest that it was medieval. The 1769 map also shows the ‘Street of the Dead’ surviving as a feature linking St Oran’s chapel and the cathedral, the walls around the Reilig Odhráin with a distinctive kink in the northern wall reflecting the original entrance to the early medieval vallum, and other field boundaries. It also shows that the immediate area around the ruins to the west and south was under cultivation, with rig and furrow clearly represented. Over the next 250 years the site had a complex history of ownership, restoration and curation, and this is reflected in many changes to the layout of the enclosing walls. An Admiralty Chart of 1857, the earliest detailed map of the island, shows the enclosure of the arable land by rectilinear fields and the new road running north–south to the west of the abbey (fig 4).

Fig 4. Admiralty Chart of the Sound of Iona in 1859 showing the re-modelled village layout. Source: Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland.

THE BACKGROUND TO THOMAS’S EXCAVATIONS

In 1956, Charles Thomas was still early in his career but had begun to build his expertise in sub-Roman archaeology and particularly the archaeology of early Christianity, with early excavations at Gwithian, in Cornwall, from 1950, Nendrum, in Co. Down, in 1954, Trusty’s Hill fort, in Dumfries and Galloway, in 1960 and an early chapel at East Porth, Teän, on the Isles of Scilly, in 1956.Footnote 42 Restoration of the abbey and monastic buildings by the Iona Community since 1938 had highlighted the need for archaeological recording of the site, and by 1956 Sir David Russell agreed to fund excavations through the Russell Trust. Professor David Talbot-Rice (Fine Art, University of Edinburgh) was given the grant and obtained permission from the Iona Cathedral Trust and the Ministry of Works to excavate. Talbot-Rice initially asked Stuart Piggot (then the Abercrombie Professor of European Prehistory at Edinburgh) to undertake the excavations, but he declined and Charles Thomas was appointed to lead the excavations. It seems likely that this work on Iona was a factor in his appointment to his first academic post as a lecturer at the University of Edinburgh in 1958. While he was excavating at Iona, Thomas was also engaged in the long-term project of excavation at Gwithian from 1950 to 1969 (partially published recently), at Ardwall Isle from 1960 to 1965, at Abercorn during 1964–5 and a survey of the monastery at Applecross in 1963.Footnote 43 It is clear from personal letters, and his account of the Gwithian excavations, that Thomas was overwhelmed by the scale of the excavations he had undertaken, and he did not excavate at Iona between the 1959 and 1963 seasons.Footnote 44 Thomas’s bibliography shows that he was also producing an astonishing range of publications throughout this period, on matters as diverse as Cornish military history to Pictish art, but it is clear that publishing his excavation reports was not one of his priorities, nor his forte.Footnote 45

The stated aim of Thomas’s campaign of excavation was ‘to recover as much as possible of the material remains of the monastic house founded in ad 563 by Columba’.Footnote 46 In particular, the course of the monastic vallum was cited as the specific aim in locating many of his trenches, and Thomas did publish a proposed plan of the monastery based on his excavation findings.Footnote 47 There was very little archaeological material from Iona available by the time Thomas and his team arrived on Iona in July 1956. Summaries of the medieval textual sources had been produced by Skene in the late nineteenth century, and O G S Crawford had made the first attempt to integrate these with field survey in the 1930s, but these accounts were based on very little excavated evidence.Footnote 48 Excavations around and within the cathedral by P MacGregor Chalmers in 1909 and 1912 had only been published in note form, but produced plans of early foundations which Thomas had available, though it is doubtful if these were reliable.Footnote 49 It was against this background that Thomas undertook his excavations, and it is important to note how much of what we now know about the layout of the early monastery is due to Thomas’s research.

Thomas’s archive

Before presenting the results of this work, it is worth addressing the nature of the surviving archive and the various issues and limitations this has presented. Thomas’s personal archive was divided into at least three main groups after the time of the excavations. The bulk of the finds archive (the original site codes are HY56–HY63) and a limited set of original plans, photographs and correspondence relating to 1956–59, were handed over to the former Historic Scotland by Thomas in Reference Thomas2012. A second group of documentary archival material is now held within the National Monuments Record (MS331). However, much of this is not the original paperwork but rather copies of the original drawings catalogued with the archive of John Barber’s 1979 excavations, which re-opened several of Thomas’s trenches. It appears that these drawings were only loaned to the former RCAHMS for the purpose of making these copies, as some of the original drawings copied and filed here were part of the material handed over by Thomas in Reference Thomas2012, meaning that the remaining drawings were misplaced in the intervening period. As such, many of the available drawings were unfortunately of low quality, being scanned copies of facsimiles.

The core of the paper archive, including the daybooks for each season, photo negatives and correspondence relating to 1960–3, were only lately located by the Cornish Archaeological Trust and handed over to the former RCAHMS in 2015, after the current project had begun. This revealed site visits, watching briefs and minor excavations carried out by Richard Reece on behalf of Thomas in 1961–2, which were only minimally recorded. The absence of key team members during the final season of excavations in 1963 means that in some cases trench locations survive only as hand-drawn maps made in the field or in sketches in daybooks, and have been reconstructed as accurately as possible given these limitations. A further group of finds from the 1957 excavations, initially in the Department of Archaeology in the University of Edinburgh, were later deposited in the National Museum of Scotland.

While the majority of the original paper archive has now been located, much has been lost for various reasons. One is simple attrition over time: several photographs, drawings and even whole notebooks mentioned in the daybooks have not survived in any form. The other issue is that of dispersal: many chunks of original material have either been retained within individual team members’ private archives, or separated out from the main archive for specialist reporting. Missing finds are presumed to have gone out to specialists, and may yet survive unidentified in museum collections. Peter Yeoman, formerly of Historic Scotland, managed to obtain valuable photos of the excavations and team members in 1957–8 from Elizabeth Fowler in 2014, while a 1956 collection of photographs (mainly architectural) by Nicholas Thomas were accessioned by RCAHMS in 2014.Footnote 50 A particular loss is the bulk of the photographs of excavations taken in various seasons by University of Edinburgh photographer Malcolm Murray, which have not been located at the time of writing this article.

The Iona Community

It is clear from the diaries that strong friendships with locals and members of the Iona Community were developed, and several local traditions were recorded. There were problems as well – at this time the Iona Community was male only, and the female members of the excavation team were banished from the heated huts:

A day of unremitting rain. Most of us succeeded in getting soaked through fairly effectively – the rain has a sort of diagonal virulence. The girls still have nowhere to stay and had to spend the night in tents on the foreshore getting soaked.Footnote 51

The Iona Community had been set up in 1938 by Reverend George MacLeod, sometime Moderator of the Church of Scotland (later Lord Fuinary), as an initiative of the Church of Scotland to encourage spiritual employment for Clydeside shipworkers, and continues today as a religious community dedicated to social justice.Footnote 52 MacLeod was an imposing and sometimes divisive figure in Scottish religious life, described by one Church Commissioner as being ‘halfway to Rome and halfway to Moscow’ due to his interests in Eastern Orthodox ritual and in social justice. Thomas describes him in a note:

Like his earliest predecessor [St Columba], he knows both academic life and the world of warfare: like him, too, he may fairly be described as aristocratic, powerful, and controversial. He also shares Columba’s gift for inspiring the deepest affection.Footnote 53

There are hints here and elsewhere in the correspondence of a conflict between Thomas and MacLeod that may have led to Thomas abandoning the excavation programme and Richard Reece taking over as director.

THE EXCAVATIONS

General

The excavations were very much a product of their time, conducted as a series of slit trenches, with no systematic planning or recording of contexts, though finds lists were kept and many sections and some plans were drawn. There was no overall site grid for planning, and locating the position of the trenches for this article was difficult while producing the Data Structure Report. The only previously published plan of the excavations was based on incomplete information and was found to be deficient in many areas, with some trenches missing and others incorrectly located.Footnote 54 Despite the problems, it has been possible through painstaking archival work to reconstruct much of the character of the excavations, and locate the most important finds. Around 100 separate trenches, here termed ‘Cuttings’, were opened by Thomas over five seasons of excavation (fig 5). The scale and nature of the work was very similar to Ralegh Radford’s contemporary excavations at Glastonbury Abbey, including the use of diagonal trenches.Footnote 55 This is not surprising as Thomas looked on Radford as his mentor and undoubtedly visited the Glastonbury excavations, and Radford certainly visited Iona in 1959.Footnote 56 Thomas was a brilliant scholar, and very much an ‘ideas man’, but he seems to have left much of the day-to-day archaeology to his assistants, all undergraduate and postgraduate students, many of whom went on to very distinguished archaeological careers. In the case of Iona, these included Vincent Megaw, Bernard Wailes, Jeffrey May, Peter Fowler, Elizabeth Burley (Fowler) and Richard Reece, who continued the Russell Trust excavations from 1964–74.Footnote 57 Other notable volunteers during some seasons included the Shakespearian actor Eric Porter, the writer Jessica Mann (later Thomas’s wife) and archaeologists Jeremy Knight, Egil Bakka, Derek Simpson, Nicholas Thomas, Graham Ritchie and Mike Walker.

Fig 5. Updated plan of Thomas’s excavation trenches around the abbey, with relevant Cutting numbers. Source: authors.

Most of Thomas’s 100 trenches were dug fairly quickly – some trenches were opened, excavated and backfilled in a few days. If nothing of interest to the excavators was found, or sometimes if the deposits could not be understood, no recording was undertaken. The nature of the archaeology often made it impossible to dig and/or understand the deposits in these restricted trenches. For example, the many slit trenches in the area of the deep vallum ditch were never bottomed or fully understood – this is not surprising as Barber’s excavations later showed there were 2.5m of waterlogged deposits here and that Thomas’s excavations had only extended into the later silting up of the ditch and the later drains.Footnote 58 Similarly, although the excavators recorded postholes and other timber features, these were impossible to interpret given the small scale of the trenches.

What the excavations do give us, however, is a broad picture of the nature of the deposits throughout the site. From this information, combined with data from other excavations, it was possible to draw an isopleth plan of the existing archaeological deposits within the abbey precincts (the boundary of the Property in the Care of the State) (fig 6). The depth of deposits varied markedly over the site. To the west of Tòrr an Aba, ploughing had removed most of the archaeology, with only a few drains being identified. Deposits gradually thickened eastwards, reaching over 2m by the east wall, and over 2.5m within the vallum ditch. Outside the precinct wall there is a marked drop-off to the surrounding fields. Much of this build-up comprised building debris and landscaping of the medieval to modern periods, but substantial stratified earlier deposits were found in many trenches.

Fig 6. Depth of surviving stratified archaeological deposits. Source: authors.

Although the numerous campaigns of building and excavation have caused extensive damage to the archaeological resource, large parts remain intact, amounting to half of the potential early medieval deposits (table 1). In addition, an unknown area of early medieval deposits presumably survives in the surrounding fields, though these were cultivated until recently. Early accounts speak of ‘buckles, brooches, and large pins’ turning up in these fields.Footnote 59 A trial trench in 2017 showed the survival of stratigraphy in at least some areas of this field.Footnote 60

Table 1. Area of early medieval deposits at Iona surviving within the Property in Care boundary.

A general sequence of deposits was recognised by Thomas’s excavators across many of the excavation trenches:

1. Modern deposits and landscaping associated with the rebuilding of the Benedictine monastery, and tumble from the collapse of these buildings in the period after the Dissolution in 1560.

2. Buildings, paving, drains and destruction debris from the Benedictine phase.

3. ‘Columban period’ deposits and ditches, pits, etc.

4. Black peaty soil, often labelled ‘OLS’– the old land surface.

5. Natural sands, gravels and raised beach cobbles.

It should be noted that Thomas’s simple division between what he termed ‘Columban’ occupation and the Benedictine phase (that is, the thirteenth to sixteenth centuries) was governed by the prevailing view at the time that Iona had been abandoned in the ninth century due to Viking attacks. For Thomas, therefore, the ‘Columban’ phase dated from the sixth to eighth centuries. Drawn sections were often labelled with these divisions (fig 7). While there was often no artefactual or scientific basis for assigning specific contexts to these periods, later excavations and radiocarbon dates obtained by Reece and Barber suggest that the general pattern holds even if the precise dating cannot be upheld, and that deposits and features labelled ‘Columban’ by Thomas date more broadly to the pre-Benedictine phase of the site.

Fig 7. Original section drawing of Thomas’s Cutting 41 showing his attribution of ‘Columban’ features. Source: Charles Thomas.

Structural evidence was seen in places, but mainly in the western part, where excavations by Reece and Barber later revealed a complex palimpsest of postholes, pits and other features (fig 8).Footnote 61 These structures are described further below, but in general they seem to occur only in two proscribed clusters: within the cloister and the areas immediately to its north and west; and in the area between the Reilig Odhráin and Tòrr an Aba. The piecemeal nature of Thomas’s excavations precluded any understanding at the time of the nature of these structures or the intensity of settlement activity they represented. In combination with a re-assessment of the finds record and a more holistic understanding of the nature of post-medieval use of the site, including modern excavations, Thomas’s record has proved more valuable than he or successive excavators thought possible.

Fig 8. Distribution of early medieval evidence, showing a strong concentration around the medieval abbey: structural evidence (![]() ); radiocarbon dates (

); radiocarbon dates (![]() ); burials (

); burials (![]() ); finds (

); finds (![]() ). Source: authors.

). Source: authors.

Chronology

Thomas’s excavations took place at the start of the radiocarbon revolution – there was no systematic collection of charcoal and no radiocarbon dates were obtained at the time. A few dates were obtained by later excavators, though some of these are problematic for various reasons, such as large standard deviations.Footnote 62 Detailed analysis of the surviving finds identified a number of charcoal samples that would be suitable for dating, and these were submitted to SUERC at East Kilbride, and are presented along with the older dates in figure 9 and table 2.

Fig 9. All radiocarbon dates from Iona Abbey, previously published dates recalibrated, notice little evidence of Viking disruption. Graph: authors, using OxCal v4.3.2.

Table 2. New and published radiocarbon dates from Iona Abbey, calibrated using OxCal 4.3.2.

Many of the dates confirm Thomas’s suspicion that the lower sequences of deposits belong to the early monastic period. For example, a date from low in Cutting 11c, south of the abbey, centres on the sixth century (SUERC-72339), and a date from Cutting 12 in the cloisters associated with a number of burials is sixth-/seventh-century (SUERC-72332). Most excitingly, the new dates from Tòrr an Aba suggest that the burnt wattle building there dates to the period around Columba’s lifetime (SUERC-74151 and 74512) centring around ad 600. This would appear to confirm the Fowlers’ suggestion that this building was indeed the hut (tegor(io)lum), ‘in a raised up place’, where Columba wrote and oversaw the community, despite doubts expressed by others.Footnote 63 Another surprise is the date of the stone-lined drain in the upper fill of Barber’s Ditch 1, which had been assumed to be later medieval.Footnote 64 In fact, deposits enclosing this drain were dated to between the late eighth and late tenth century (SUERC-72331) and show that significant structural activity – probably an enlarging of the monastic enclosure – was taking place at this enigmatic period in the history of the site (see below). Other dates are discussed in the appropriate sections below. Looking at the date ranges as a whole, there is some evidence for pre-Christian activity on the site from the Bronze Age onwards, and no clear break in occupation in the late first millennium (again, features that had been suspected).

THE ROAD TO SALVATION

One of the key discoveries of Thomas’s excavations was the unexpected uncovering of a substantial paved roadway running from the Reilig Odhráin to the ruined building to the west of the cathedral labelled the Old Guest House by Reece.Footnote 65 Although a path is shown here on the 1769 estate plan (see fig 3), the hollow it lay in had been infilled with debris in the intervening period and its nature was unsuspected. The roadway is in two sections, each with different character of paving, with a sharp kink between the sections, and is clearly of two periods. The section which runs north from the Reilig Odhráin is the earlier, and is paved with very large, water-rounded, tightly packed boulders of red Ross of Mull granite, which have a polished surface due to heavy foot traffic (fig 10).

Fig 10. The surface of the boulder-paved roadway surface exposed in Thomas’s Cutting 20 in 1959, looking north west. Photograph: © Professor Charles Thomas Collection.

The road was a very substantial construction, involving the procurement and transport of a large quantity of stone, at least 250 tonnes of material for the section within the monastic enclosure, representing a major investment of resources in its construction. Its character differs from the later medieval flagging seen around the west end of the abbey church.Footnote 66 Thomas identified this road with the Sràid nam Marbh (‘Street of the Dead’), a coffin road known from antiquarian accounts to have run from the traditional Iona landing place in Martyrs’ Bay towards the cathedral, although this name properly refers to a different, later medieval routeway running towards the centre of the abbey.Footnote 67 However, the name continues to be used in most accounts of this boulder-paved roadway, and will be used here as an identifier. The full extent of the road was revealed by clearance work overseen by Richard Reece in 1962–3, associated with celebrations for the 1,400th anniversary of Columba’s founding of the monastery (fig 11). The later coffin road, marked on the 1769 estate plan and running to the south-east corner of the medieval abbey, was excavated in 2013 and found to be of quite different character as it was surfaced with an insubstantial gravel spread.Footnote 68

Fig 11. The paved roadway leading from the Reilig Odhráin directly towards St Columba’s shrine chapel, with St Martin’s Cross on the left and the base of St Matthew’s Cross on the right. Photograph: © Crown copyright: Historic Environment Scotland.

The early stretch of paved road is between 2m and 3m wide with a kerb at least intermittently on the east side, and was also bounded by a low wall on its west side which may be of later date. Because the roadway is such a unique feature in an early medieval context, it has perhaps not received the attention it deserves. Paved roads in Britain ceased to be built with the collapse of the Roman Empire, and in general do not re-appear until the post-medieval period. Previous accounts of the road have assumed that its construction belongs to the Benedictine phase, apparently a misunderstanding based on a comment by Reece that only applied to the later northern section of paving.Footnote 69 The road passes through an original gap in the large vallum ditch excavated by Barber, which was dated to the seventh/eighth century (table 2: GU-1243, 1365 ± 55; cal ad 580–770), so it must have been created in some form at that time. Barber also assigned the paving of the earlier part of the road, if not the original line, to the later Benedictine period on the basis that some stone-lined drains are attached to its eastern side.Footnote 70 However, the new dates obtained from material surrounding the drain places its construction in the late eighth to late tenth century (table 2: SUERC-72331; 1175 ± 32, cal ad 770–970). Without excavation of the road itself, which has not taken place, it is impossible to be sure of the relationship of the boulder paving to any putative earlier surface, or to the drains. The simplest explanation for the data is that this is an original roadway that ran between the most sacred parts of the island (see below), and that the slightly later drains were built to re-channel older drain lines that lay beneath the road surface. This date from the drain also confirms that the vallum ditch here was mainly infilled by the eighth/ninth century, suggesting that the section of vallum further south, under the St Columba Hotel, represents an expansion of the original enclosure.

The more northerly section of the road has paving of mixed materials, often slabby, and runs outside the line of the Benedictine enclosure wall. It includes some rounded boulders of granite that have clearly been derived from the earlier section of paving. This section represents a re-routing of the main approach to the abbey, taking visitors through a gateway in the western enclosure wall, and probably dates to the later medieval period. Reece reported that it had several phases of paving in places, and sealed grass-marked pottery.Footnote 71

The construction, possibly in the seventh/eighth century, of such an impressively engineered paved roadway in this remote location has to be explained, especially as there seem to be no parallels in other contemporary Insular contexts. The route of the paved road can be reconstructed from antiquarian accounts and recent geophysical study (fig 12). It extends southwards through the Reilig Odhráin, towards a presumed entrance in the outer ditch of the vallum beneath the St Columba Hotel, then runs past the north door of St Ronan’s church towards the traditional landing place at Martyrs’ Bay with its burial mound, An Eala. However, in this area there is no sign of paving seen in geophysical investigations of the surrounding fields or in recent test pitting.Footnote 72 In the other direction, it must have continued its direct line towards St Columba’s shrine chapel, and its line is possibly seen here in recent geophysical work.Footnote 73

Fig 12. The early medieval monastic liturgical landscape of Iona, showing the roadway, the monastic enclosure ditches, early chapels (![]() ), extant crosses (

), extant crosses (![]() ), crosses inferred from bases or documentary sources (

), crosses inferred from bases or documentary sources (![]() ) and burial grounds (

) and burial grounds (![]() ). Source: authors.

). Source: authors.

This paved routeway is best interpreted as marking an early medieval pilgrimage route linking the main devotional and burial sites on the island: the landing place at Martyr’s Bay, and the chapels of St Ronan, St Oran and St Columba (see fig 12). The burial ground at Martyrs’ Bay has stone-lined, long cist burials and at least one early medieval-dated burial.Footnote 74 St Ronan’s medieval church overlies an early medieval clay-bonded stone-built chapel, which itself overlies early burials, unfortunately undated.Footnote 75 This early chapel appears to have antae characteristic of early Irish chapels.Footnote 76 It is very similar in size and construction to the clay-bonded St Columba’s shrine chapel and is possibly of similar early date. The existing structure of St Oran’s chapel is thought to be of twelfth-century date (though this dating derives from a doorway that is inserted into an earlier fabric), but it presumably also had an earlier predecessor.Footnote 77 St Oran’s importance on Iona is attested by the Middle Irish Life of Colum Cille at least by the twelfth century, where Columba reputedly states ‘No-one will be granted his request at my own grave, unless he first seek it of you’, indicating that pilgrims and penitents should follow a set liturgical route through the monastic complex.Footnote 78 St Oran’s chapel was the focus of the Reilig Odhráin, traditionally the burial ground of kings, and in the later medieval period of local lords and clan chiefs. Perhaps significantly, this burial ground lay outside the original monastic enclosure.

The roadway was also flanked by at least seven monumental free-standing crosses (see fig 12). Although the crosses on Iona are perhaps the most intensively studied monuments of early medieval Scotland, almost nothing has been written on their placement within and around the monastic precinct. Three early medieval crosses were standing in their original positions near the west door of the abbey when first recorded by antiquarian travellers (namely the crosses of St John, St Martin and St Matthew), while fragments of several others have also been recorded around the abbey.Footnote 79 Cross-bases show that another two crosses stood by the edge of the Street of the Dead, one in the Reilig Odhráin and one with a mill-stone base closer to the abbey, uncovered in excavations.Footnote 80 In addition, the fragments of a complex box cross-base similar to that of St John’s Cross was first recorded just west of St Oran’s chapel, and may have held St Oran’s Cross, also first recorded here.Footnote 81 Further crosses are known from documentary sources: St Brandon’s near the outer entrance of the enclosure; St Adomnán’s near Port Adomnán; and Na Crossan Mor – two crosses in the north-west of the monastic enclosure. Later medieval crosses include the extant McLean’s Cross; a similar cross recently excavated in the grounds of the primary school; a cross-base in a mill-stone on the summit of Tòrr an Aba; and several others, some of which may have had early medieval predecessors.Footnote 82 There is an account of many crosses being ordered to be destroyed by an act of the Synod of Argyll in 1642, though these could have been cross-incised slabs, if they were actually destroyed.Footnote 83 However, the large number of attested crosses illustrates the importance of Iona, and compares with Irish sites such as Clonmacnoise and the possibly Iona-founded monastery at Portmahomack.

The function of these early medieval high crosses has been much discussed, with their use as boundary markers, sanctuary crosses, teaching aids, preaching crosses, reliquaries, Rogationtide processional markers or weather crosses all being suggested.Footnote 84 However, Adomnán, in our only contemporary account of crosses on Iona, mentions three that were erected to commemorate important incidents in the life of Columba and presumably served as stations for prayer and reflection, both by the monks as they passed them on their way to work in the fields and by pilgrims visiting St Columba’s shrine.Footnote 85

The devotional landscape of Iona can be also be interpreted more generally as representing a journey towards salvation, with the monastery being seen as a metaphor for both earthly and heavenly Jerusalem.Footnote 86 This route mimics the journey of pilgrims to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem, with the objective of reaching the holiest places on the island, St Columba’s shrine and the altar of the church. The unstated but implied parallel between Columba and Christ is one that occurs many times in Adomnán’s Vita (for example, in the story of his turning water into wine).Footnote 87 Throughout his Vita, Adomnán emphasises incidents in the daily life of the monastery that take place on the monks’ journey to and from their fields on the west of the island. These include the story of the weary crane, Columba’s spiritual visit to his monks, Columba’s visitation by angels, the miracle of rain brought about by Columba’s relics and, particularly, in the extended account of Columba’s last days.Footnote 88 In addition there are numerous references to visitors, pilgrims and penitents who would have followed the same routeway to the monastery. Given Iona’s proposed role in the development of the ideal conceptual layout of the early monastic community, the roadway gains added significance. Pilgrims such as Adomnán’s informant, the Gaulish bishop Arculf, would have been familiar with the paved streets of Rome and of Jerusalem itself (the early via dolorosa followed the route of the main east–west Roman road in Jerusalem, the decumanus maximus), and those streets must have been the model for the construction of the Iona road. It is likely that the Iona road itself then became the model for other Insular monasteries, as roads have been found at Portmahomack, the Isle of May, Govan, Whithorn and Hallow Hill, St Andrews.Footnote 89 Most of these are not as substantial as the Iona road, being surfaced with gravel or pebbles. In Ireland there are several paved roads at Clonmacnoise, though the paved phase of these seems to date to the eleventh century, and other paved roads associated with monasteries also seem to be of later medieval date, emphasising the unique nature of the Iona roadway.Footnote 90 At Glastonbury, the early churches may have been aligned on a Roman road, but no trace of this was found in excavation, and a similar situation existed at Canterbury where the churches of Peter and Paul, St Mary, and St Pancras lie along the Roman road.Footnote 91 Elsewhere in England, a walled corridor at Wearmouth, in the north east of England, has been interpreted as a porticus, a covered processional way linking buildings within the early monastic complex, a feature seen as being deliberately modelled on examples from Rome.Footnote 92 A possible predecessor to this is represented by short stretches of cobbled path that are less substantial than the Iona roadway, but it was suggested by the excavator that this may have been a path to the river and so could have had a similar function to Iona’s roadway.Footnote 93 Éamonn Ó Carragáin has shown how the early liturgy known at Wearmouth/Jarrow also reflected the Roman liturgy designed around a processional way that linked stations at churches within Rome.Footnote 94 It can be speculated that Adomnán’s focus on Jerusalem, as well as on Rome, may have served the function of differentiating Iona from both Anglo-Saxon and, especially, Armagh-based monastic practice that primarily referenced Rome.Footnote 95

THE SACRED BOUNDARY

Early monasteries symbolised their separation from the secular world by the use of enclosing walls, hedges, banks or ditches. The enclosed area also had a different legal status, functioning as a place of sanctuary. The form of the monastic enclosure at Iona has long been recognised as a puzzle, as it does not conform to the Irish pattern of circular, often concentric, vallum ditches, but has a generally sub-rectangular shape. In addition, with the advent of aerial photography and then geophysical survey, a more complex pattern of ditches became apparent, and several attempts have been made to give an overview of the layout of the monastery.Footnote 96 Iona is also unique in having two upstanding earthwork banks surviving around part of the circuit. A major new geophysical survey has provided a much more detailed picture of the site, which reveals the ditches in particular (fig 13).Footnote 97

It is clear that the pattern is complex and multiphase, making it difficult to speak of ‘a vallum’. Only a detailed programme of dating can hope to resolve the relative chronology of the many elements that make up these enclosures, but a sequence of gradual enlargements can be postulated. Dates obtained in 2017 show that the north-western section dates from the eighth century (table 2: SUERC-77872, 1268 ± 22; cal ad 680–770), and it may be that these surviving earthworks date to a later period of monumentalisation of the site associated with the enshrinement of Columba’s relics, rather than the primary phase of occupation. The strange route of this western section, which cuts across rocky ground to a cliff-edge, may have been designed to enclose the ‘little hill’ from which Columba blessed the monastery on his final day.Footnote 98

One of Thomas’s main aims was to locate the monastic vallum, and many of his trenches were located with this aim specifically in mind. Work in 1956 formally began when Thomas and Megaw chartered a flight out of Perth on an early June morning to photograph the vallum from the air. They were able to trace the outline of the enclosure to north and south of the abbey, and this provided the basis for much of their survey and excavation in the first season. The 1956 season involved only a limited amount of excavation (six trenches) but a great deal of survey, including an early geophysical survey using a Megger Earth Tester to try to trace the vallum north of the abbey. When he was digging, the only plan of the vallum available was that of Crawford, which assumed a single enclosing ditch.Footnote 99 Thus when Thomas encountered a substantial ditch in Cutting 11a in 1957, he assumed this was ‘the vallum’. Attempts were made to follow the line of this ditch with Cuttings 11f, 19 and 23 to the north east, and Cutting 48 to the south west, where he confused this ditch with the main ditch later excavated by Barber as Ditch 1. There are excellent drawings of these ditch sections showing an infilling with stones, and Thomas published a reconstruction of the vallum as a stone-revetted bank.Footnote 100 Trenches were also dug to the north of the abbey, specifically to look for the continuation of this ditch, in Cuttings 25–8, with little success, though a small feature was seen in Cuttings 25 and 27. There are no details of these features, and they must have been ephemeral, as a plan by Thomas of what he considered to be the monastic enclosure, which was based on the results from these trenches, shows the ditch as speculative there.Footnote 101 The strange sinuous line of Thomas’s enclosure results from his attempts to marry quite different ditches into one coherent system. There is no doubt that the ditch in Cutting 11 is a real boundary of some kind, even though it has been dismissed as a drainage ditch.Footnote 102 It is, however, unlike any of the drainage ditches found elsewhere on the site, which are always stone-lined, and it runs across the slope, making it unsuitable for drainage. It is, however, parallel to the newly discovered stone-built structure excavated in 2017 and 2018.

The complexity of the enclosure and lack of dating precludes the construction of a sequence for the enclosures. Barber suggested that the core of the early monastery lay to the south of Reilig Odhráin and later extended northwards.Footnote 103 This scenario has not gained wide acceptance, and most commentators consider that the core of the early monastery lay around the site of the later abbey church. Thomas’s excavations would seem to confirm that early medieval activity was widespread over this area, with most structural evidence and early radiocarbon dates lying to the west and south of the church (see fig 12), and that the enclosure to the south is a later expansion.

Despite the difficulties in defining the monastic enclosure, its form is basically rectilinear, with rounded corners, and open to the sea to the east. This form raises serious questions, as Irish monastic enclosures are almost invariably sub-circular in form, often with clear concentric zones (fig 14). This ‘Irish model’ has been applied to Scottish monastic sites in the belief that monasticism was spread from Ireland, and therefore Scottish sites should follow an Irish layout.Footnote 104 This model has resulted in attempts to force the Scottish evidence for enclosures into a circular straitjacket. For example, at Whithorn, Inchmarnock and Dunning, a circularity has been imposed on short sections of ditches or ephemeral features.Footnote 105 In fact all the Scottish monastic sites where we can see the form of the enclosure clearly appear to follow the Iona model rather than the Irish model, with C- or D-shaped sub-rectangular enclosures with one side open to the landscape at rivers (Forteviot, Fortingall, Hoddom, Dunning), scarps (St Blane’s) or the sea (Iona, Portmahomack, Kinnedar, Lindisfarne, St Andrews) (fig 15).

Fig 14. Comparative plans of monasteries in Ireland showing concentric enclosures. Source: Heather Christie, after Swan Reference Swan, Fixot and Zadora-Rio1994, fig 3.

Fig 15. Comparative plans of monastic enclosures in northern Britain showing more rectangular forms with one side open to a scarp slope, shore or river. Source: Heather Christie.

As Iona was certainly founded by Irish monks, the question has to be asked: why did they not follow the pattern of their homeland in constructing their monastery? Only two Irish sites appear to have similar non-circular enclosures: Clonmacnoise, open to the River Shannon to the west, and on Lambay Island.Footnote 106 If Lambay was the Rechra of early sources, as seems likely, it was founded by Ségéne, the fifth abbot of Iona, so it is no surprise that it might follow an Iona pattern.Footnote 107 The only historical connection between Iona and Clonmacnoise is Adomnán’s story of Columba’s visit there, which incidentally mentions the vallum, which must have been in existence then.Footnote 108 The excavated ditch at Clonmacnoise was even more impressive than that at Iona, at 5–6m wide and 3.75m deep, though its date of construction is unknown.Footnote 109 It is possible, given Adomnán’s favourable view of Clonmacnoise, that it formed a model for Iona (or viceversa).Footnote 110 The possibility that there was a pre-existing Iron Age enclosure on Iona that was adapted by the new Columban tenants in the sixth century has been suggested. Radiocarbon dates from an old ground surface beneath the inner bank at Iona suggested this section at least was built in the first century bc to the second century ad, but the new dates dismiss this, confirming that the ditch was dug in the seventh/eighth century (table 2: SUERC-77872).Footnote 111 A second possibility is that the sub-square form at Iona is based on English or Continental prototypes, whose monasteries derive their form from Roman forts, town or villa plans. Examples include Glastonbury, the Northumbrian phases at Whithorn, Jarrow/Monkwearmouth and the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem, according to Adomnán’s plan.Footnote 112 This seems a plausible explanation, given the interest in the layout of Jerusalem as a model for monastic life.

Whatever the inspiration for the layout at Iona, it seems that the model was adopted at other monasteries in Scotland, whether associated with the Columban familia or not. Circular enclosures were used around churchyards, cemeteries and smaller religious sites, but there is no certain example around an early monastic site.Footnote 113 Of particular interest is Portmahomack, where both the enclosure and the situation of the monastery overlooking the sea and the distant mountains seems like a reflection of the situation of Iona.Footnote 114 Elsewhere one of the authors has suggested that the open-sided form of these enclosures might reflect an outward-looking predilection to engage with the world (natural or secular), in contrast to the more inward-looking secluded form of the concentric or square monastic enclosures in Ireland and southern England, which encourages a more private contemplation.Footnote 115

COMMEMORATING THE DEAD

Thomas’s excavations might have been assumed to encounter many burials, as is usual when excavating around long-lived church sites. However, only a very few burials were found in his trenches, and a similar pattern was found in other excavations. A cluster of burials were found in Cutting 12 within the cloister. The new radiocarbon dates from charcoal associated with these bones gave an early date (table 2: SUERC-72332; 1477 ± 32; cal ad 540–650). This part of the excavation was poorly recorded with no plans, but was described in print by the excavators as a ‘mass burial’ and ‘possibly associated with a Viking raid’.Footnote 116 However, the excavation daybook speaks of six skeletons as interments, and recently discovered photographs show that these were normal, albeit closely spaced, carefully laid out inhumations.Footnote 117 This cluster of graves would therefore appear to be a normal monastic burial ground, something not encountered in any other excavations on Iona – and if it is co-eval with the charcoal layer, it must belong to the first phase of Christian use of the site. This would suggest that the earliest church lay nearby, presumably beneath the medieval cathedral crossing. Re-excavation of Thomas’s Cutting 11 to the south of the abbey in 2017 enabled dating of three partial skeletons to the tenth to twelfth centuries, definitely pre-dating the Benedictine phase.

In other excavations Reece found what he interpreted as a north–south orientated long cist grave and a possible east–west burial just south of the Old Guest House.Footnote 118 Redknap found late medieval burials clustered alongside St Columba’s chapel, but also two early log coffin burials at a lower level, which have now been dated to the ninth and tenth centuries.Footnote 119 Elsewhere in Scotland log coffins are a sign of early burials.Footnote 120 A series of graveslabs formerly paved the entrance approach to this chapel (fig 16) and at least one has an inscription, possibly to a known abbot of Iona, Flann (d. 891). It would not be surprising if prominent ecclesiastics of the monastery were buried close to the shrine of their founder saint, and other burials seem to cluster around the proposed site of the early monastic church.

Fig 16. Early medieval graveslabs paving the entrance to St Columba’s shrine chapel (walls in purple), as drawn by Henry Dryden in 1874. Note the projecting antae and the two stone-lined long-cists within the chapel. Source: courtesy of Historic Environment Scotland – Society of Antiquaries Scotland Collection.

It is commonly assumed that the Reilig Odhráin was a lay cemetery, given its traditional role as the burial ground of kings and its late-/post-medieval use for burial by local aristocracy.Footnote 121 At least six other burial grounds are known on the island (see fig 12). Concentrations of stone burial monuments are known from all three chapel sites along the roadway, but most are recorded from the Reilig Odhráin.Footnote 122 Recent scholarship in Ireland has suggested that these burial monuments may have been produced solely for ecclesiastics, though inscriptions to royal burials are known.Footnote 123 Ó Carragáin has suggested that in Ireland there was a different concept of sacred space in the early Christian period, with sepulchral and liturgical spaces being kept apart.Footnote 124 This may go some way to explain the relative lack of burial around Columba’s shrine if the whole monastery, or, in the case of Iona, the whole island, was sanctified by the presence of the saint’s relics. The total lack of grave markers at the secular burial site at Martyrs’ Bay might support this idea. Overall there is a dense complex of burial grounds, similar to that seen in many Irish ecclesiastical sites such as Clonmacnoise and Iniscealtra (another ‘Holy Isle’), with differentiation and segregation of different groups such as women and kings.Footnote 125 Apart from the Lapis Echodi stone, which may commemorate a seventh-century king of Dál Riata, almost all the more elaborate and inscribed graveslabs on Iona are late, dating to the ninth to eleventh centuries, and few are inscribed.Footnote 126 This lack of investment in personal memorialisation is in contrast to sites in Anglo-Saxon England (for example, Lindisfarne and Hartlepool) and in Continental Europe, where memorials to named individuals are more common.

The traditional association of the Reilig Odhráin with the burial of ‘many kings of Scotland, Ireland and Scandinavia’ is controversial and mainly a later medieval invention, but there is little doubt that early medieval kings were buried there.Footnote 127 Contemporary Irish annals record the retirement (and presumably deaths) of Niall Frossach, king of Tara (d. 788), and Artgal, king of Connacht (d. 791), and the retirement and death of the Norse king of Dublin, Olaf Sihtricsson, to Iona in 980. The seventh-century Lapis Echodi stone may refer to Eochaid Buide, king of Dál Riata (d. 629). Several probably reliable sources claim that Ecgfrith, king of Northumbria (d. 685), was buried on Iona after the battle of Nechtansmere, and a tenth-century poem about the burial of Bruide mac Bile, king of the Picts (d. 692), in ‘an old hollow oak trunk’ may reflect an older Iona tradition that chimes with the early log burials found beside Columba’s shrine chapel.Footnote 128 The later aggrandised traditions of the burial of medieval kings may have built on these earlier realities. Royal burial at major Irish monasteries is better documented and provides corroboration of Iona as a royal burial site. For example, at Clonmacnoise royal burials associated with the kings of Connacht, and later of Clann Cholmáin, took place from at least 663, and grants of land in return for this favour are recorded in the ninth century.Footnote 129 Other kings were buried at the important monasteries at Clonard and Armagh, where there may be references to a separate burial ground for royalty, as is the case at Glendalough.Footnote 130 It has been suggested that the presence of another ‘Relickoran’ lay burial ground on Inishmurray was a deliberate attempt to mirror the layout of Iona.Footnote 131

The later burials at St Ronan’s church were all of women and children, though unfortunately the early medieval burials were too badly preserved to sex or date.Footnote 132 The site was an Augustinian nunnery from the thirteenth century, and the post-medieval burials were exclusively female, but whether this was always a burial site for women is unknown, though perhaps likely. Separate burial grounds for royalty and women are known from Irish monastic islands such as Inishmurray.Footnote 133 Some of the other burial grounds have names suggesting that they were restricted to particular groups, though when these were current is unknown without excavation. Cladh nan Druineach suggests the burial place of embroideresses, presumably of ecclesiastical garments, while Cill mo Ghobhannan, ‘church of my little smith’, may have similar artisanal associations, though it may merely be a saint’s name.Footnote 134 Several of these early burials sites show a persistence of use indicative of long-standing local traditions: the Reilig Odhráin up to the present day; St Ronan’s up to the eighteenth century; and Martyr’s Bay until at least the fourteenth century.Footnote 135 At least four have associated chapels: St Columba’s; St Oran’s, St Ronan’s; and Cladh an Dìsirt. Of these, St Columba’s and St Ronan’s appear from their form to be early medieval, and St Oran’s presumably had an early medieval predecessor.

RELICS AND RELIQUARIES

An important part of pilgrimage to Iona, and of life in the monastery there, was the reverence shown to relics of Columba and Adomnán. These relics were the key objects of pilgrimage, as they allowed direct intercession with God through the saint’s remains. Adomnán’s bodily remains were enshrined in a reliquary (scrín) by the early eighth century and Columba’s by at least the early ninth century, and reliquaries of both saints were taken backwards and forwards to Ireland during the eighth and ninth centuries.Footnote 136 Relics of vestments and books associated with Columba are known to have been used in rituals from at least the end of the seventh century, and were presumably also enshrined by craftworkers on Iona.Footnote 137 An Old Irish poem, reputed to be by Adomnán, describes a collection of relics, including those of Columba, Donnán of Eigg and other Irish and Continental saints.Footnote 138 The details mentioned – the hair-shirt of Columba, the knee-cap of Donnán – suggests these were real objects, which could have been enshrined at Iona. The only shrine of an Iona relic that certainly survives is the later medieval Irish-made shrine that contained the Cathach, the late sixth-century psalter traditionally believed to have been written by Columba. Despite the evidence from the sculpture and manuscripts that highly skilled craftworkers were present on Iona, until now there has been no physical evidence of the types of high quality ecclesiastical metalwork known from Ireland.Footnote 139 New evidence from Thomas’s excavations can allow us to be sure that there were metalworkers with the necessary skills to make shrines on Iona in the eighth/ninth centuries and later. These copper alloy metalwork artefacts include a lion figurine (fig 17) and a human head (fig 18), which are described in detail elsewhere with other finds.Footnote 140 Fine metalwork was certainly being produced on Iona, as fragments of typically early medieval crucibles and moulds have been found scattered through various excavation trenches, though no centre of production has yet been encountered.

Fig 17. Lion figurine in copper alloy (SF0997) from Thomas’s excavations in Reference Thomas1959. Photograph: © Historic Environment Scotland.

Fig 18. Copper alloy human head (SF 0962) from Thomas’s excavations in Reference Thomas1959. Photograph: © Historic Environment Scotland.

The eighth/ninth-century lion figurine, although unparalleled, resembles finials on some house-shrine reliquaries and may have come from a larger type of reliquary. A contemporary triangular possible shrine fitting from Armagh, itself unparalleled, shows that there were objects of forms unknown as complete examples.Footnote 141 It displays some characteristics of the lions in the Book of Kells, and lions are prominently featured on Iona crosses such as St Martin’s and the Kildalton Cross on Islay, suggesting it was made on Iona. The human head figure, which appears to have been ripped from a larger piece, has close parallels to the figures on the twelfth-century St Manchan’s shrine.Footnote 142 This suggests that relics were being enshrined or re-enshrined around the twelfth century, possibly replacing earlier reliquaries removed or destroyed during the Viking raids. Later in the medieval period there are references to an arm-reliquary of Columba on Iona in the fifteenth century.Footnote 143 This type of reliquary is normally a late form, suggesting there was a process of continuing renewal of enshrinement on Iona, but it has been suggested that an arm-shrine was in existence in the seventh century.Footnote 144 Patrick Geary has discussed many Continental examples of this process whereby ‘enthusiasm tended to wane over time, and the value of the relic had to be renewed periodically’, and one can assume a similar process at work in Iona.Footnote 145 Apart from these portable reliquaries, it is possible that the unusual box-bases of St John’s, and probably St Oran’s, Cross functioned as a sort of reliquary container, as it is difficult to account for their complex construction otherwise. It is possible that one of these crosses was erected to commemorate the martyrdom of Blathmac mac Flainn in 825 – given that a cross is known to have been erected to commemorate an incident on the day Columba died, and that Blathmac’s martyrdom was famous enough to be commemorated in Walafrid Strabo’s poem.Footnote 146 Thus the relics of Iona also formed part of the complex ritual landscape of shrines, chapels, crosses and the intangible memories and stories associated with the saints and martyrs of Iona.

STRUCTURES

Although Thomas’s excavation strategy precluded the identification of most timber structures, one significant stone structure was revealed in Cutting 11d. Here, a substantial wall of drystone construction, with a battered face, ran in an arc towards the abbey buildings (fig 19). This construction is unlike anything else seen on Iona, and re-excavation of Thomas’s trench in 2017 has enabled it to be dated to before the eighth century and show that it had been demolished by the tenth century. Further excavation should reveal its nature, but it looks like the revetment for a level platform to support a building. Chalmers, the architect in charge of the restoration of the cathedral, reported the discovery of ‘a large stone building with rounded gables, running north–south under the nave of the church’, unfortunately with no further details or plans.Footnote 147

Fig 19. Drystone structure exposed by Thomas in Reference Thomas1957 south of the abbey, and re-excavated in 2017, looking north. Photograph: authors.

Other structural evidence in stone was restricted to substantial slab-lined drains, which form an extensive system around and within the abbey, clearly designed to help with drainage problems caused by iron-panning on the raised beach gravels.Footnote 148 These have been assumed to be of later medieval date, but the new date from the drain in the main vallum ditch shows that some at least may be early medieval. A series of drains found in the various trenches of Cutting 60 to the west of Tòrr an Aba were of different character and are almost certainly late field drains, as the estate map of 1769 shows an area of standing water here.

Apart from a 10m-long sill-beam or plank trench with associated postholes found in Cutting 38, which has been compared to the buildings at Yeavering, very few signs of buildings were found in Thomas’s excavations.Footnote 149 The Cutting 38 building is significant, however, as it is the only rectilinear timber building found on the site so far, and has been claimed by Brian Hope-Taylor (who saw photographs taken at the time of excavation, which no longer survive) to be identical to his Yeavering Style iv buildings with plank walls (fig 20). Recent excavations at Rhynie have produced similar plank-built buildings, which date to the sixth century, supporting Hope-Taylor’s contention that this style of building was a British rather than Anglo-Saxon tradition.Footnote 150 The important find of a bronze human head (SF0962) came from near this structure.

Fig 20. Original section drawing of sill-beam slot in Thomas’s Cutting 38. Source: Charles Thomas.

Other structural remains were encountered within the cloister area in Cutting 17. Here the excavations in 1958 were directed by Elizabeth Burley and seem to have been recorded to a better standard than most of the other trenches, though unfortunately most of the drawings have been lost. Burley’s account describes a complex sequence of deposits in the southern part of the area, around Cutting 17f, with stone settings, cobbling, burning layers and spreads of sand and clay interpreted as the remains of ‘huts’. There seems little doubt these deposits represent structural activity in this area, though its nature remains obscure.

However, other excavations on Iona have revealed evidence of a large post-built roundhouse, post-pad rectangular buildings and other possible round post-built structures.Footnote 151 These structures all fall in a linear zone that lies to the west of St Columba’s chapel, and presumably also to the west of the original monastic church (see fig 8). The lack of excavations in the eastern part of the site precludes any definite statements about occupation in this area.

A group of window glass sherds (fig 21) was one of the most unexpected finds from Thomas’s assemblage, and was not recognised by Thomas as being early medieval. This is not surprising as early medieval window glass from Britain was only recognised with the excavations at Jarrow.Footnote 152 The manufacturing features of the glass – a soda-lime-silicate glass, cylinder-blown with fire-rounded straight edges and grozed sides – are matched by the glass from Jarrow and other monastic sites in England and is easily distinguished from later medieval window glass. In Scotland the only other early medieval window glass is from the Northumbrian-period occupation at Whithorn, and in Ireland there is no known window glass of this date.Footnote 153 Especially close in colour and appearance is the seventh-century window glass from Glastonbury Abbey, which was probably manufactured there.Footnote 154 Although the Iona glass cannot be dated precisely, it must fall in the period from introduction of window glass to Britain in the seventh century to the late ninth century, when glass compositions changed to potash-rich unstable types that rarely survive. This, of course, is the period of the first flowering of Iona as an artistic centre. The implication of the window glass is that some building with a glazed window existed on Iona in the early medieval period, possibly St Columba’s shrine chapel. The evidence from Whithorn shows that glazed windows could be associated with clay and timber buildings at this period.Footnote 155

Fig 21. Sherds of early medieval window glass (SF1023), forming rectangular quarries, with rounded and grozed edges. Photograph: © Historic Environment Scotland.

CRAFTS