Non-volant terrestrial mammals are commonly absent from Oceanic islands. Yet each of the two islands of São Tomé and Príncipe, in the Gulf of Guinea off the coast of Central Africa, hosts an endemic shrew (Rainho et al., Reference Rainho, Meyer, Thorsteinsdóttir, Juste and Palmeirim2022): the São Tomé shrew Crocidura thomensis on the 857 km2 São Tomé Island and the Fingui white-toothed shrew Crocidura fingui on the 142 km2 Príncipe Island.

The shrew occurring on Príncipe, first considered conspecific with C. thomensis (Bocage, Reference Bocage1903) and later reclassified as Crocidura poensis, a species native to mainland Africa (Heim de Balsac & Hutterer, Reference Heim de Balsac and Hutterer1982), was recently described as C. fingui based on molecular and morphological evidence (Ceríaco et al., Reference Ceríaco, Marques, Jacquet, Nicolas, Colyn and Denys2015; Nicolas et al., Reference Nicolas, Jacquet, Hutterer, Konečný, Kan Kouassi and Durnez2019). It is the only native non-volant mammal on Príncipe, where it has been described as common and widespread (Ceríaco et al., Reference Ceríaco, Marques, Jacquet, Nicolas, Colyn and Denys2015) despite being known from only four sites, all in the north of the island (Rainho et al., Reference Rainho, Meyer, Thorsteinsdóttir, Juste and Palmeirim2022). Little is known regarding the ecology of and any threats to this endemic insular species, which is categorized as Data Deficient on the IUCN Red List (Ceríaco et al., Reference Ceríaco, Dando and Kennerley2019). Here we reassess this categorization based on > 90 new records of the species and new information regarding potential threats.

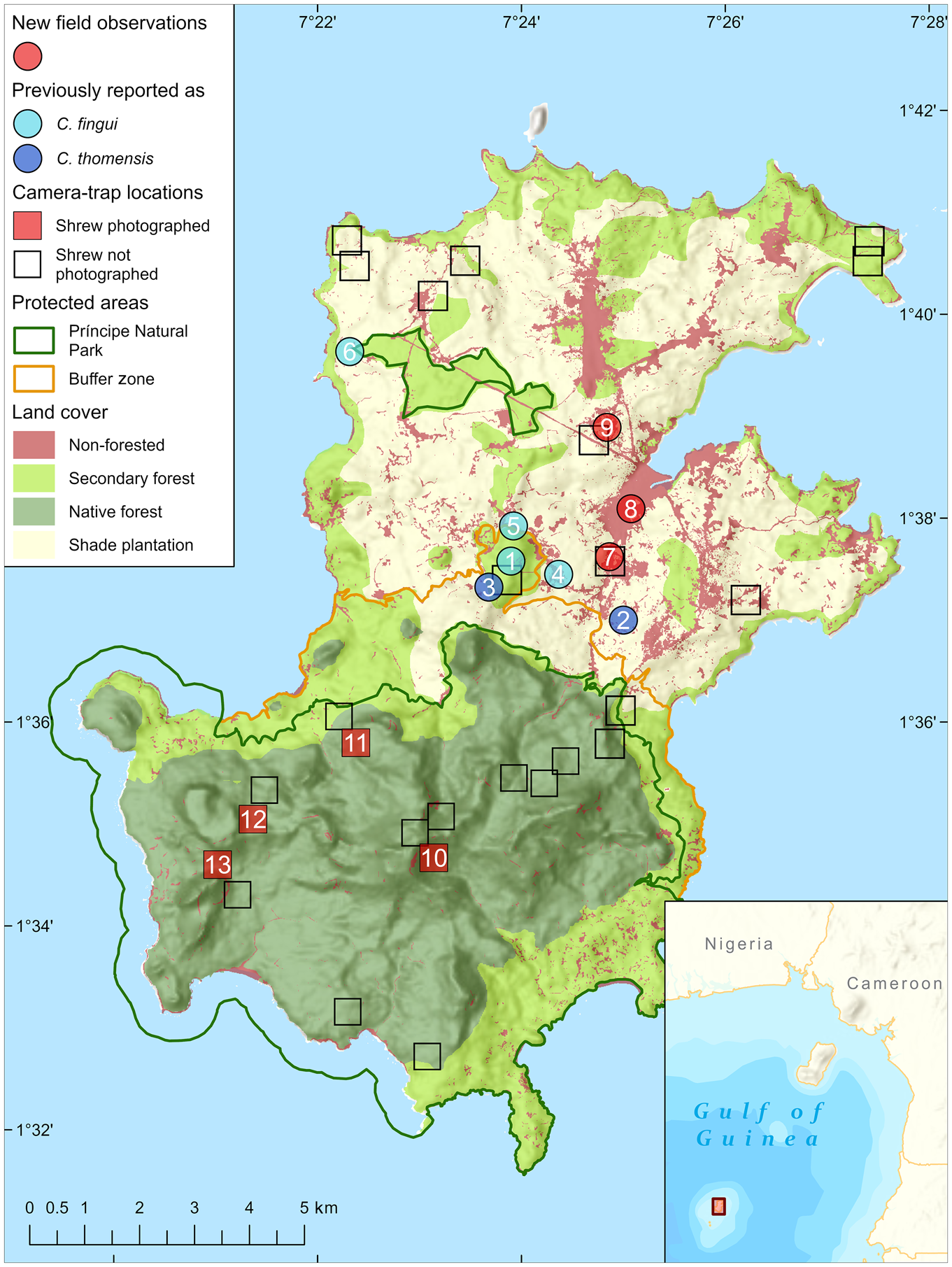

During March 2019–August 2022 we deployed camera traps (Bushnell Essential E3, Bushnell, USA, and Browning PATRIOT, Browning, USA) across various land-cover classes, including native forest in Príncipe Natural Park in the mountainous south of the island where C. fingui had not been previously recorded (Fig. 1). We deployed the cameras at 26 sites for 2–188 days, attached to trees at c. 30 cm above ground and oriented towards structures that could be frequented by animals. The cameras operated continuously, with high sensitivity and a sequence of three captures per activation. Photographs containing animals were considered to be distinct records if captures occurred > 30 min apart. We collected the data in the context of a wider study on introduced mammals and thus we selected this camera-trap method instead of methods more conventionally used for micromammals. We further collated previously published records, four new observations and three records previously misidentified as C. thomensis (CAS Mammalogy, 2022a,b; UMMZ Mammals Data Group, 2022).

Fig. 1 Previous and new records of the endemic Fingui white-toothed shrew Crocidura fingui across the various land-cover classes of Príncipe Island (Freitas, Reference Freitas2019; Soares, Reference Soares2019) in the Gulf of Guinea off the coast of Central Africa. For details of the numbered records, see Table 1. (Readers of the printed journal are referred to the online article for a colour version of this figure.)

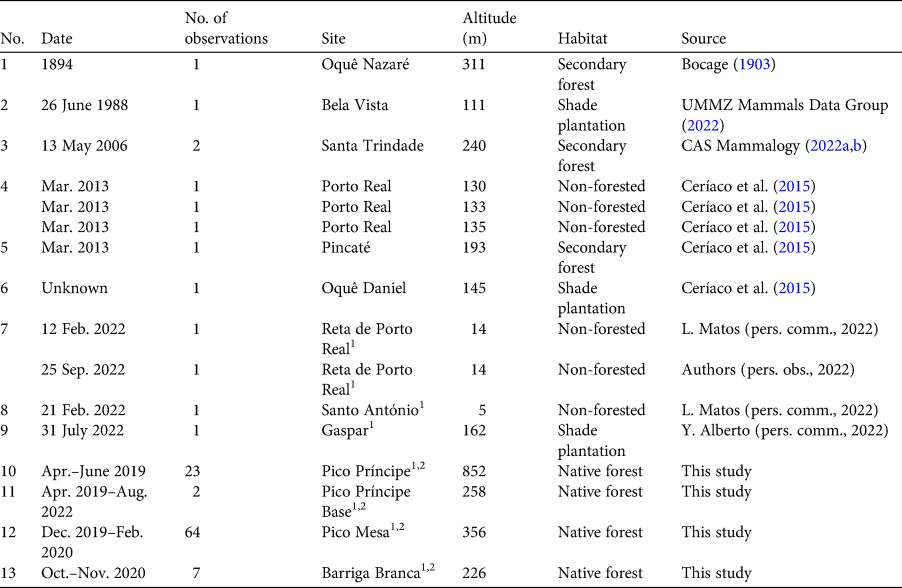

Table 1 Records of the endemic Fingui white-toothed shrew Crocidura fingui on Príncipe Island, with date of observation, number of observations, site, altitude, habitat and source. The numbering of the records corresponds to those in Fig. 1.

1 New field record.

2 Camera-trap record.

During 2,433 camera-trap days we obtained 96 records of shrews across four sites (Fig. 1). Shrews were photographed between 17.32 and 4.55, suggesting a largely nocturnal activity pattern. Rats Rattus spp. were observed at these four sites (55 records), closely matching the circadian rhythm of the shrew, whereas similarly nocturnal African civets Civettictis civetta (three records) and a domestic cat Felis catus (one record) co-occurred with the shrew at only one site each (Plate 1). Mona monkeys Cercopithecus mona (18 records) were detected at three sites, but only during the daytime. These findings extend the previously known maximum altitude of C. fingui by c. 500 m, to 852 m, with > 80% of records above 300 m. Collating the camera-trap data, field observations and previously misclassified records resulted in 103 new records of C. fingui from nine sites across all land-cover classes (Table 1; Fig. 1).

Plate 1 Camera-trap photographs of the Fingui white-toothed shrew Crocidura fingui (a), and the co-occurring rat Rattus sp. (b), domestic cat Felis catus (c) and African civet Civettictis civetta (d). The top two photographs are from Pico Mesa (site 12 in Fig. 1), the bottom two from Barriga Branca (site 13 in Fig. 1).

These records extend the known distribution of C. fingui and support claims that the species is able to use both human-impacted and native habitats (Ceríaco et al., Reference Ceríaco, Marques, Jacquet, Nicolas, Colyn and Denys2015). This habitat flexibility and the extensive forest cover of Príncipe (Fig. 1) suggest that land-use change alone does not pose an immediate threat to the species. Nevertheless, on small islands even widespread taxa can undergo rapid range contractions. The black rat Rattus rattus has been linked to the possible extinction of the Christmas Island shrew Crocidura trichura (Meek, Reference Meek2000) either as a vector for Trypanosoma or because of predation, competition or other indirect effects (Eldridge et al., Reference Eldridge, Meek and Johnson2014). Crocidura trichura was abundant and widespread in 1900 but virtually disappeared following the introduction of black rats (Meek, Reference Meek2000). Similarly, the spatiotemporal coexistence of C. fingui with introduced mammals raises concerns about the potential threats that predation or competition from these introduced species might pose (Dutton, Reference Dutton1994; Rainho et al., Reference Rainho, Meyer, Thorsteinsdóttir, Juste and Palmeirim2022), similar to the situation regarding C. thomensis on São Tomé (Dutton & Haft, Reference Dutton and Haft1996; de Lima et al., Reference de Lima, Maloney, Simison and Drewes2016). One of our records was of a shrew captured by a free-ranging cat, and anecdotal evidence suggests that such captures are frequent.

We recommend that the conservation status of C. fingui should be recategorized to Endangered based on criteria B2ab(v); i.e. area of occupancy < 500 km2 (B2), known to occur in five or fewer locations (a), and evidence, estimation, inference or projection of a continuous decline in the number of mature individuals (b(v)). A ‘location’ is any geographically or ecologically distinct area where a single threatening event could swiftly impact all individuals of the taxon inhabiting it (IUCN, 2022), and in this context we consider Príncipe to be a single location. To support its conservation, we also recommend that further research is conducted on the ecology of this insular endemic species.

Author contributions

Fieldwork: all authors; data analysis: JCA, PG; writing: JCA, PG, RR.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Príncipe Regional Government and Príncipe Natural Park for authorizing the surveys, and Litoney Matos and Yanik Alberto for sharing details of their observations. Fieldwork, data analysis and writing benefitted from funding from the Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund (CEPF-103778), the Fonds Français pour l'Environnement Mondial, UNDP-GEF (project ID 10007) and the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement 854248).

Conflicts of interest

None.

Ethical standards

This research abided by the Oryx guidelines on ethical standards. All fieldwork was conducted with the approval and support of local authorities.

Data availability

Data misreported as Crocidura thomensis supporting this study are available from GBIF.org at doi.org/10.15468/dhbozg and at doi.org/10.15468/dx3rcj. Camera-trap data are available from the corresponding author upon request.