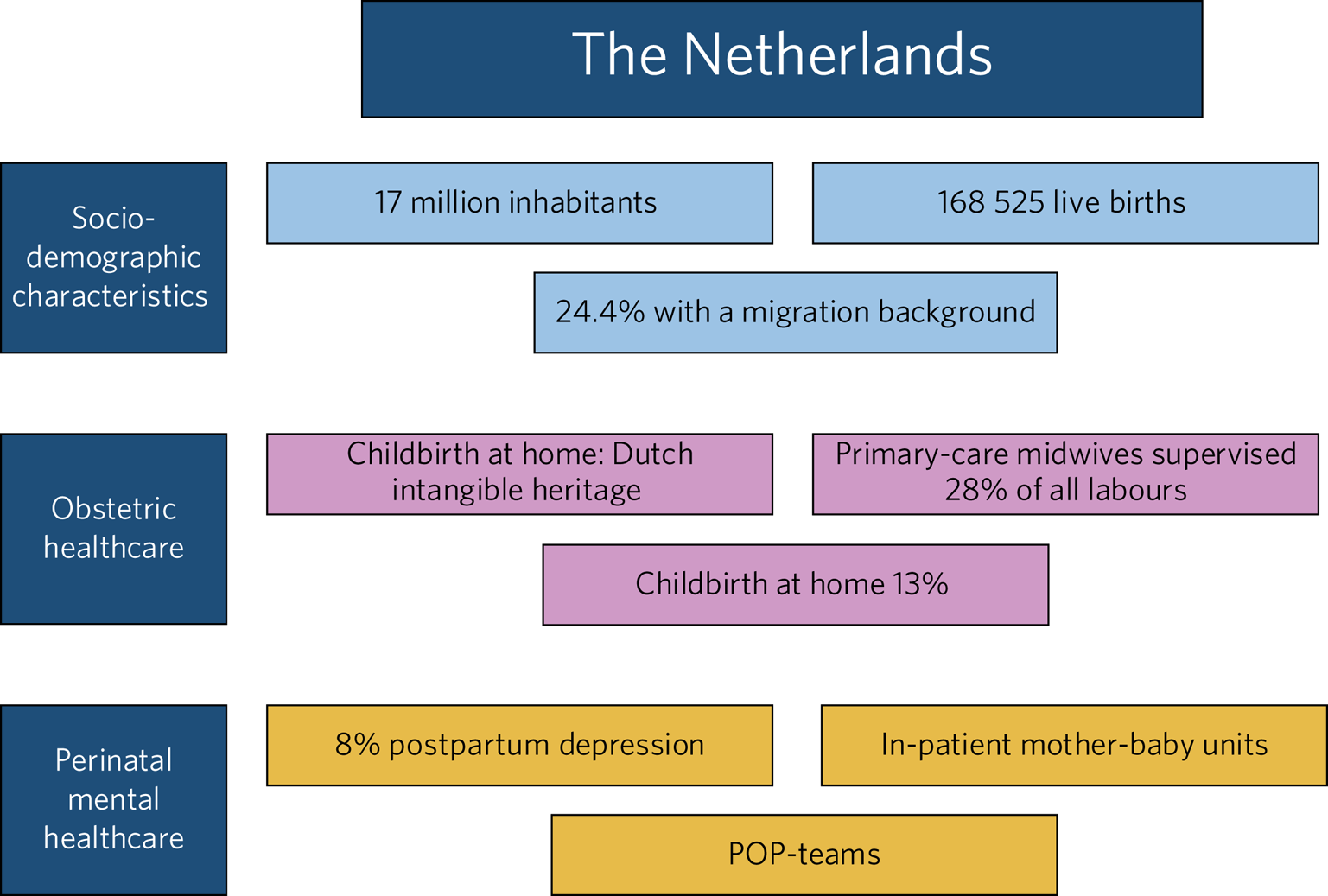

The Netherlands, a densely populated country in Western Europe, has about 17 million inhabitants (416 persons per square kilometre) and had 168 525 live births (relatively 9.8 per 1000 inhabitants) in 2018. The Netherlands is often perceived as a modern and tolerant society, referring to the multicultural composition of its population. In 2020, 24.4% of the total population had a migration background, including first- and second-generation immigrants. Most of them originate from Turkey and Morocco. Within Europe, The Netherlands has been rated the highest 3 years in a row for satisfaction of inhabitants with their healthcare system and the accessibility of healthcare and medications. Within The Netherlands, mental healthcare, however, does differ from one region to the next.Reference Watson1

There has been an increased interest in perinatal mental health during recent decades in The Netherlands. For instance, in 2009 the National Knowledge Centre for Psychiatry and Pregnancy was established to improve mental healthcare in the perinatal period.

The current paper starts by outlining current Dutch clinical practice of perinatal healthcare, followed by a description of the research on perinatal mental healthcare with recommendations for future improvements. Finally, the impact of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic on perinatal mental health services is outlined.

Dutch clinical practice

General organisation of healthcare services

The Dutch government is responsible for the quality and accessibility of the country's healthcare system. The health policy and its implementation are organised at a national level by the Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport. Under the ministry's responsibility, there is a basic health insurance, which is mandatory for all citizens older than 18 years. Government assistance is available for low-income individuals and those unable to afford the basic health-insurance premium, thereby ensuring access to healthcare for all citizens. In our healthcare system the general practitioner (GP) functions as the main gatekeeper to specialised healthcare (e.g. hospital care), with the goal of enhancing the quality of healthcare and preventing excessive costs. Perinatal healthcare is available for all women, at no extra cost.

A decade ago, research suggested that healthcare use varied across different ethnic groups (with first-generation immigrants forming the largest minority).Reference Stronks, Ravelli and Reijneveld2 More recent research indicates that ethnic minorities visit the GP more often than the indigenous population.Reference van der Gaag, van der Heide, Spreeuwenberg, Brabers and Rademakers3 The current expansion of second-generation immigrants might lead to increased equality in healthcare use, as they are more integrated in society.

Perinatal and postpartum care

Integrated obstetric healthcare is provided. Pregnancy care is delivered predominantly by primary care midwives, who monitor pregnant women for physical and mental health problems, and make specific referrals if needed. So midwives function as gatekeepers during pregnancy. In 2016, the Standard for Integrated Birth Care was developed, which outlines the content and organisation of birth care in The Netherlands; if it is not medically necessary to give birth in a hospital, alternative locations are available: at home, in a birthing centre or in an out-patient clinic. In 2018, approximately 28% of all labours were supervised by primary care midwives and 13% of all labours took place at home. The amount of childbirth at home is considerably higher in The Netherlands than in other European countries, where less than 1% of all labours took place at home. Perinatal mortality in The Netherlands is 4.2 per 1000 births (2015), and compared with other European countries The Netherlands holds the middle position. Dutch research showed no difference in the rates of intrapartum and neonatal death up to 28 days after birth between planned hospital births and planned home births among low-risk women.Reference de Jonge, Geerts, Van Der Goes, Mol, Buitendijk and Nijhuis4 Analysis of Euro-PERISTAT data shows that the perinatal mortality rate at term is not significantly different in The Netherlands than in other European countries (in which home births and primary care births are uncommon).Reference De Jonge, Baron, Westerneng, Twisk and Hutton5 As the ‘Dutch home birth culture’ is unique in the world, this culture was added to the list of Dutch intangible heritage in 2020.

As mentioned above, all mothers are entitled to daily healthcare during the first week after delivery. The maternity nurse performs healthcare checks for both mother and neonate, informs and helps parents with common problems during the postpartum period (including mental health problems), is alert to problems in mother–baby interaction and supports the household. After maternity care, preventive healthcare in child health clinics follows, where the child's development is monitored as well as the mother–child relationship and maternal mental health. New mothers can download a mobile app, produced by the Municipal Health Service (GGD), to follow the child's development (growth curves, vaccinations, milestones, etc.).

Throughout pregnancy and the postpartum period, professionals are mandated to report suspicions of domestic violence and/or child abuse, in accordance with the Protocol of Domestic Violence and Child Abuse. Prevalence of intimate partner violence in the perinatal period ranges from 3.9 to 8.3%.Reference Brownridge, Taillieu, Tyler, Tiwari, Chan and Santos6 Domestic violence is known to increase the risk of postpartum depression and suicidal ideation in new mothers, which can lead to problems in mother–child interaction and other threats.Reference Koirala and Chuemchit7 Signalling abuse is of great importance to optimise a healthy and safe environment for both mother and child.

The protocol additionally includes advice on informing the Safe at Home Centre. If the Safe at Home Centre is notified, this facility investigates and, if needed, initiates additional care.

Perinatal and postpartum mental healthcare

As mentioned, a substantial part of perinatal care is delivered by midwives, who are trained to be aware of perinatal mental health. Throughout the country, various hospitals and out-patient clinics offer perinatal mental healthcare. In the past decade, considerable advancement has been achieved in ‘POP care’ (psychiatry, obstetrics and paediatrics). The POP team often includes psychologists, psychiatrists, gynaecologists, midwifes, paediatricians and social workers, which all strive to achieve excellent biopsychosocial healthcare through multidisciplinary collaboration. Referrals to POP teams come from the various collaborating disciplines, as well as from primary healthcare (GPs) and mental healthcare institutions. Psychiatry residents can choose to follow an internship focusing on perinatal mental healthcare during their training. Within POP care various treatment options can be offered, including (but not limited to) pre-conception counselling, psychological treatment (e.g. cognitive–behavioural therapy, eye-movement desensitisation and reprocessing) and/or pharmacological treatment. Postpartum care is also extensive. For instance, mothers with severe psychiatric illness and their infants can be admitted to specialised medical-psychiatric departments in hospitals, e.g. in-patient mother and baby units. These facilities provide psychiatric care for the mother and evaluate mother–baby interaction. More recently, infant mental health specialists – who are trained to evaluate and enhance mother–child interactions and infant mental health development – are increasingly participating in POP care. To support best practice for healthcare workers, evidence-based national guidelines are available concerning the use of psychiatric drugs (such as benzodiazepines and antidepressants) during the pre-conception period, pregnancy, childbirth and in the postpartum period.8

Research on perinatal and postpartum mental healthcare in The Netherlands

Perinatal

Overall lifetime prevalence figures for mood and anxiety disorders in The Netherlands are 20.2% and 19.6% respectively.Reference de Graaf, Ten Have, van Gool and van Dorsselaer9 The prevalence of depressive symptoms during pregnancy increased from 7% in 1988 to 14% in 2014.Reference Pop, Van Son, Wijnen, Spek, Denollet and Bergink10 This is comparable to meta-analysed international rates by trimester: 7.4% (first trimester), 12.8% (second) and 12.0% (third).Reference Bennett, Einarson, Taddio, Koren and Einarson11 Two in five pregnant women with a history of major depression had at least one depressive episode during pregnancy or after delivery. These episodes were more severe than episodes occurring outside the perinatal or postpartum period.Reference Meltzer-Brody, Boschloo, Jones, Sullivan and Penninx12 Furthermore, non-Dutch ethnicity is found to be associated with elevated pregnancy-specific anxiety.Reference Westerneng, Witteveen, Warmelink, Spelten, Honig and de Cock13 An explanation might be that women of non-Dutch ethnicity in general experience higher depression and anxiety levels owing to cultural differences, negative life experiences and lower socioeconomic status.Reference de Wit, Tuinebreijer, Dekker, Beekman, Gorissen and Schrier14

Postpartum

‘Generation-R (and -Next)’ is a Dutch population-based prospective cohort study of mother–child dyads, running from pre-conception through adulthood. Of the 4941 women in this cohort, 8% developed postpartum depression. These women were statistically younger, less educated and more likely to be of non-Western origin than those without postpartum depression. Various pregnancy and delivery complications were predictive of postpartum depression, including pre-eclampsia, hospital admission during pregnancy and emergency Caesarean section.Reference Blom, Jansen, Verhulst, Hofman, Raat and Jaddoe15 The prevalence of postpartum depression in The Netherlands is comparable to that in the USA and Europe.Reference O'Hara and Wisner16,Reference Vesga-Lopez, Blanco, Keyes, Olfson, Grant and Hasin17 The global incidence of postpartum psychosis (not specific to The Netherlands) ranges from 0.89 to 2.6 in 1000 births.Reference VanderKruik, Barreix, Chou, Allen, Say and Cohen18 One Dutch study reports a postpartum relapse rate of 44.4% in patients with a history of psychoses limited to the postpartum period. This rate decreases to 0 for patients receiving lithium prophylaxis immediately postpartum. Women diagnosed with bipolar disorder are required to continue lithium prophylaxis during pregnancy and postpartum, thereby minimising the risk of relapse in those periods.Reference Bergink, Bouvy, Vervoort, Koorengevel, Steegers and Kushner19

Perinatal and postpartum combined

A Dutch population-based study reports a general increase of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) usage throughout pregnancy and postpartum for the past 16 years.Reference Molenaar, Lambregtse-van den Berg and Bonsel20 In 2013–2014, 3.9% of women in The Netherlands used SSRIs before pregnancy, decreasing to 2.1% during pregnancy and increasing to 3.1% postpartum. These rates are comparable to those in Denmark and Italy. In the UK, rates of SSRI use among women during the year before pregnancy were noticeably higher (8.8–9.6%).Reference Charlton, Jordan, Pierini, Garne, Neville and Hansen21 In the USA, prescription rates increased from 2.9% in 1999 to 10.2% in 2003 during pregnancy.Reference Cooper, Willy, Pont and Ray22 The relatively lower prescription rates in The Netherlands imply a prescription threshold for SRRIs reflecting treatment only for more severe psychiatric disorders. One could suggest that low prescription rates imply limited ability of GPs to recognise perinatal mental illness. However, the presumption is that they refer pregnant women with mental health problems to ‘POP care’ for specialised treatment, including medication.

Mental healthcare during and after pregnancy has mainly focused on mothers. However, there is increasing awareness of the perinatal mental health of fathers in research worldwide. A meta-analysis estimated the prevalence of postpartum depression in fathers at 10.4%, with maternal postpartum depression being the strongest predictor.

Nowadays, household structures are changing and this can contribute to psychopathology during the perinatal period. For example, being a single mother or bisexual/lesbian can increase the risk of depression and anxiety in pregnancy.Reference Ross, Steele, Goldfinger and Strike23,Reference Bogaerts, Devlieger, Nuyts, Witters, Gyselaers and Guelinckx24

Service development and priorities

Perinatal mental and infant health are topics of increasing government interest. The efficacy and cost-effectiveness of the national preventive programmes and biopsychosocial interventions that have been implemented to date are in need of evaluation.

Current programmes and interventions

Promising Start (Kansrijke Start: www.kansrijkestartnl.nl) is aimed at improving the mental and physical health of infants, focusing on the first 1000 days. The programme includes prenatal, perinatal and postpartum care and support for vulnerable parents (both current and prospective).

Not Pregnant Now (Nu Niet Zwanger: www.nunietzwanger.nl) provides financial (and other) support to vulnerable men and women helping them in their decision-making about sexuality, contraception and the desire to have children.

A programme from the Trimbos Institute is aimed at preventing perinatal and postpartum depression, including the early recognition of problems and the provision of psychoeducation to parents, in addition to counteracting stigmatisation by normalising problems (www.trimbos.nl/kennis/zwangerschap-en-depressie).

The campaign ‘Hi, it is okay’ (Hey, het is oké: www.heyhetisoke.nl) also focuses on decreasing stigmatisation of mental health problems, including postpartum depression. Results show that people with psychological problems (anxiety and/or depression) felt less stigmatised after this national campaign.

In addition, midwives can use the standardised online Mind2Care questionnaire – provided and validated by LPKZ (the National Knowledge Centre for Psychiatry and Pregnancy) and containing questions about mental health, psychosocial problems and substance use – as a screening instrument to provide personalised recommendations for the provision/improvement of medical and psychosocial care during pregnancy and the postpartum period.Reference Quispel25 This instrument also includes questions from the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale, which is validated in pregnant women in The Netherlands and also used as a separate screening instrument for depressive symptoms.Reference Bergink, Kooistra, Lambregtse-van den Berg, Wijnen, Bunevicius and Van Baar26 The preventive implementation of this questionnaire for all pregnant women, including the measurement of response rates and identification of those not responding, could further optimise the accessibility of mental healthcare.

We think it is of great importance to translate mentioned initiatives into different languages and make those also available for low-literacy women.

Accessibility to help could be enhanced by e-health programmes. For example, the MamaKits Online intervention is aimed at reducing anxiety and depressive symptoms in pregnant women.Reference Heller, Hoogendoorn, Honig, Broekman and van Straten27 The app WellMom is developed to improve welfare and prevent depressive feelings during and after pregnancy, and the app Loss is designed to amplify mental resilience of mothers and fathers who lost their child during or after pregnancy. Both apps are based on evidence-based effective interventions such as cognitive–behavioural therapy. For Turkish and Moroccan pregnant women with depressive symptoms, specifically, an online pilot course was developed and implemented called Positively Pregnant.

Worldwide, maternal and infant health mobile apps are increasingly being developed and used for health education. As mentioned, in The Netherlands, parents can download an app, produced by the Municipal Health Service (GGD), to make a lasting record of their child's development. The Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (USA) designed and launched a comparable app.

Research and development

As described above, both research on perinatal mental health and implemented interventions to improve mental health have mainly focused on mothers. Further research into support systems (especially co-parents) is of great importance. Psychosocial problems in families need a dyadic approach (mother–partner) rather than individual approach (mothers).

Fig. 1 summarises key facts about The Netherlands and its perinatal mental healthcare.

Fig. 1 Key facts about The Netherlands and its perinatal mental healthcare system.

COVID-19 pandemic and the impact on perinatal mental health services

In December 2019, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), which causes COVID-19, manifested in China and the spread of this virus was excessively rapid, resulting in a global pandemic. To prevent further dissemination in The Netherlands, strict measures were implemented in the daily lives of citizens: these included social distancing, working from home (if possible) and restricted travel. For pregnancy-related healthcare, restrictions were applied that included a limited amount of supportive accompanying persons for the pregnant women during consultations, labour and the postpartum period. During the pandemic mental healthcare is mainly provided by video- or phone consultation. However, it is know that the COVID-19 outbreak can trigger mental health problems such as anxiety, stress, anger, depressive symptoms and insomnia.Reference Torales, O'Higgins, Castaldelli-Maia and Ventriglio28 The restrictive measures during pregnancy might cause additional perinatal stress, although we do not know the actual impact. In some countries, a mother with COVID-19 will be separated from her newborn to reduce the chance of transmission. This intervention may delay mother–infant attachment and can increase maternal anxiety. The separation of mother and child because of COVID-19 is not a standard of care in The Netherlands.

Knowledge about the COVID-19 virus and its effects on pregnancy is still growing. In general, pregnant women and the fetus are a vulnerable group concerning infectious diseases, owing to physiological changes in pregnancy.Reference Dashraath, Wong, Lim, Lim, Li and Biswas29 Therefore, pregnant women may have increased concerns about vertical transmission to their fetus, in addition to concerns about the health of their loved ones and their own health.

Research indeed shows an increase in symptoms of anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress during the COVID-19 pandemic in both pregnant women and in new mothers during the postpartum period.Reference Zanardo, Manghina, Giliberti, Vettore, Severino and Straface30–Reference Basu, Kim, Basaldua, Choi, Charron and Kelsall32 Screening for perinatal mental health problems is therefore especially important at the moment, as this pandemic can be an additional stress factor.Reference Chen, Selix and Nosek33

Owing to the COVID-19 pandemic, The Netherlands has been in national lockdown twice. Parents had to work at home if possible, while schools and day care were closed for children whose parents did not have a crucial job. COVID-19 has also caused economic devastation and created distance from community resources and support systems. These circumstances may stimulate domestic violence where it did not exist before, and may have worsened existing abuse in some families. In The Netherlands, no increase in official reports of domestic violence and abuse has been registered by Safe At Home. However, signs detected by childcare professionals indicate that emotional neglect of children increased during the first lockdown.Reference Vermeulen, van Berkel and Alink34

The Dutch government provides reliable online information on COVID-19 and pregnancy. For instance, the website of the Covid Healthcare Support Centre (www.steunpuntcoronazorgen.nl/) focuses on the impact of COVID-19 pandemic (and the restrictions) on psychosocial factors: it provides information about mental stress specific to this pandemic and recommendations for support. Pharos (www.pharos.nl) provides information about COVID-19, related national measures and the impact on pregnancy and the postpartum period specifically for low-literacy citizens and for those whose native language is not Dutch.

Conclusions

Perinatal and postpartum mental health is a high priority for the Dutch government and healthcare professionals. The increasing interest in psychopathology during and after pregnancy has resulted in a well-developed biopsychosocial healthcare system in The Netherlands. One unique feature is the comprehensive collaboration between primary care (GPs and midwives) and hospital care (including POP care). Furthermore, the government organises and funds various healthcare programmes aimed at improving perinatal healthcare. The COVID-19 pandemic increases anxiety and depression during the perinatal period and further highlights the importance of a well-developed perinatal mental healthcare system. Research is needed to evaluate the programmes and forms of care, as well as to identify women who are not receiving appropriate healthcare. In addition, research should focus more on the psychopathology of the family as a whole rather than individuals only.

Data availability

Data availability is not applicable to this article as no new data were created of analysed in this study.

Author contributions

I.L. contributed to the conception of the work, drafted the manuscript and approved the final version to be published, C.P.M.V., D.A.W., H.M. and M.J.T. contributed to the conception of the work, critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content and approved the final version to be published. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of interest

None.

ICMJE forms are in the supplementary material, available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bji.2021.47.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.