Objects bring worlds with them.

——Sara Ahmed, Living a Feminist LifeDespite the passage of three decades since the opening of the Berlin Wall led to the collapse of communism, a robust interest in the memory culture of the German Democratic Republic, or GDR, shows little sign of waning. Films, novels, art, theatrical pieces, and even private museums continue to explore the range of experiences of everyday life under socialism (Cliver Reference Cliver2014; Bach Reference Bach2015; Ehrig, Thomas, and Zell Reference Ehrig, Thomas and Zell2018), broadening our understanding of people’s agency without minimizing the constraints of an oppressive regime. At the center of this now-sizable body of scholarship remains a focus on material culture and the “privileged place” of mundane consumer objects as “historical markers of socialist experience and identity” (Betts Reference Betts2000: 734) that can be traced back to the late 1990s. In the years following German reunification, discussions of materiality and temporality found expression in a discourse of Ostalgie, or nostalgic feelings for certain products or brands once made in the GDR and discontinued. Desire for popular brands, scholars argued, was not a sign of longing for a repressive, bygone state but an articulation of the sense of social dislocation after die Wende (transition)—the loss of self, dignity, values, and history that people attached to, and made claims to, through objects (Berdahl Reference Berdahl1999: 199; Blum Reference Blum2000: 230; Boyer Reference Boyer2006: 366).

As much as the perspectives and actors at the center of analyses of GDR material culture have diversified across time, one constant remains: a focus on German memory that assumes whiteness as the normative cultural experience. The copious literature on the material legacies of East Germany has privileged white German consumer practices at the expense of other, non-white and non-European encounters with GDR commodities. Like the exclusion of the racialized subjects in German Holocaust memorialization (Partridge Reference Partridge2010), GDR memory politics presume a white German subject at the center of history. The silencing of voices and experiences of racialized Others has made it possible to ignore race and represent East Germany as a homogeneous white society that was closed off from outside influences (Piesche Reference Piesche and Lennox2016: 226). That German unification and its memory have reified the exclusion of those who “remain the others” is captured poignantly in May Ayim’s poem “blues in black and white” (blues in schwarz weiss): “a reunited germany / celebrates itself in 1990 / without its immigrants, refugees, jewish and black people / it celebrates in its intimate circle / it celebrates in white” (Reference Ayim and Adams2003: 4; also cited in Lennox Reference Lennox and Lennox2016: 21).

There are cracks in this façade of cultural and ethnic uniformity, however, as more scholars take up the question of race and racism in “raceless” socialist societies that saw themselves aligned politically with oppressed and colonized peoples (Roman Reference Roman2007). Recent years have seen increased attention to racial thinking in the GDR (Slobodian Reference Slobodian and Slobodian2015), and to the place of “minorities” and “foreigners” in East German society (Dennis and LaPorte Reference Dennis and LaPorte2011) and their role in creating a migrant-driven, “ethnicized economy,” not unlike that in West Germany or the FRG (Chin and Fehrenbach Reference Chin, Fehrenbach, Chin, Fehrenbach, Eley and Grossmann2009: 25). It may be a stretch to call the GDR “multicultural”—the almost two hundred thousand foreign nationals constituted only 1.2 percent of the population in 1989 (Dennis and LaPorte Reference Dennis and LaPorte2011: 87), including more than ninety thousand migrant workers.Footnote 1 Even so, iconographies of racial harmony touted the GDR’s internationalist values and policies of anticolonial solidarity that opened its borders to socialist “friends,” particularly those from the revolutionary South. And yet, in this largely archival-based scholarship, we hear little from the subaltern recipients of socialism’s paternal beneficence.

This essay conjoins these lines of inquiry—consumer goods and racialized subjects—to examine migrant material culture and its circulation in and beyond the GDR. In shifting the site of inquiry to the global South, and to the foreign nationals who lived for extended periods in East Germany, I unsettle the implicit whiteness in the study of GDR cultural memory. Rather, popular identification with East German goods extended outside Germany’s national borders to countries targeted for modernization through GDR assistance as a solution to postcolonial underdevelopment. Drawing on ethnographic research with repatriated Vietnamese migrants, I rethink formulations of Ostalgie as a site of German oppositional memory only (Berdahl Reference Berdahl1999: 193) by highlighting Other consumer desires and practices that were once rendered a threat to national stability (Zatlin Reference Zatlin2007).Footnote 2 In calling for attention to racialized subjects and their material practices across time and space, I seek to expand the lens of Ostalgie and its emphasis on unmoored historical artifacts from what remains (Bach Reference Bach2017) to where. My aim is to push the study of Ostalgie in new and more inclusive directions by decentering whiteness to consider other, less studied interactions among time, space, and materiality that informed the consumption, exchange, and meanings of GDR things.

The bodies of literature on material culture and ethnic minorities in the GDR share an intellectual and methodological orientation that this article questions: the nation-state as a bounded unit of analysis and observation (Wimmer and Glick Schiller Reference Wimmer and Schiller2003). Within this framework, migrants and objects appear, ironically, as static—in contrast to the fluidity of the capitalist West. Consumption of objects by white East Germans—objects that circulated but ultimately remained in-country to become part of national memory—or, conversely, migrants passively fixed in place in East German society, preclude discussions of cross-border mobilities. The perception of East Germany as a territorially delimited space is not altogether surprising given the dominant construct of Eastern Bloc countries beyond an “iron curtain” as closed with impenetrable borders. Discourses of isolation and lack of free movement—also within East German societyFootnote 3—have made it easy to neglect agency and the extent to which socialist global processes shaped people’s daily practices, subjectivities, and experiences of everyday socialism. To be sure, national borders were heavily policed and flows of migrants limited and controlled. Yet they were neither wholly controllable nor entirely nonporous, as my analysis here will show.

Scholars have only recently begun to take seriously the critical role that material culture plays in migration processes (e.g., Rosales Reference Rosales2018; De León Reference De León2012), though this perspective remains understudied in research on Germany. Ethnographic studies of GDR consumer goods have tended to overlook encounters between non-German actors and everyday things, while GDR things, if discussed in migration histories, are rendered largely inert to illustrate social anxieties about deprivation (for East Germans) and accumulation (by racial Others), and thus reify ontological distinctions between (active) people and (passive) things (see Latour Reference Latour1999). A more sustained analysis of postcolonial migrant material culture under socialism is essential to understanding its role in transforming consumerism in both East German and Vietnamese societies, and to considering how robust and affectively charged objects may have “consequences for people that are autonomous from human agency” (Miller Reference Miller and Miller2005: 11).Footnote 4 The question of what those “bundled” qualities of materiality are that generate value and meaning through their effects and affects, even after socialism, motivates this essay (Keane Reference Keane2003: 414).

While it is generally known that Vietnamese labor and educational migrantsFootnote 5 in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union sent large quantities of consumer goods back to Vietnam as remittances, often illicitly, little is known about the items themselves and what families did with them once in their possession. In tracing the social lives of socialist objects—from mundane commodities to everyday technologies that traveled across space and time—this essay asks: what did Vietnamese migrants carry or send home, and what can these objects tell us about the lived racial experience of socialist-era mobilities, and, by extension, livelihood struggles in postcolonial and post-reform Vietnam?Footnote 6 How were value, status, and identity produced through socialist commodities across profoundly different cultural and geopolitical contexts where consumption was similarly framed as a collective good to enrich and reimagine society, rather than as an individual self-entitlement (Coderre Reference Coderre2019: 41; Berdahl Reference Berdahl2005a: 241)?

Far from the picture of seclusion and mutually shared poverty, GDR goods brought a considerable degree of modernity, distinction, consumerism, as well as black market activities to post-revolutionary Vietnam. Moreover, as vehicles for creating social and moral difference, these goods offer a counter-perspective on Vietnamese nationals in East Germany that challenges neo-communitarian depictions of migrant populations as bounded, static, and united by ethnic identity (Wimmer and Glick Schiller Reference Wimmer and Schiller2003: 598–99).Footnote 7 In what follows, I analyze the norms, moral hierarchies, and gendered subjectivities that guided the transacting of socialist objects as they moved among overlapping spheres of exchange, as speculative, gifted, and status commodities (Kopytoff Reference Kopytoff and Appadurai1986: 71).

In examining the supercharged goods that journeyed along well-trodden paths to Vietnam—often bypassing regulatory regimes—and their subsequent use and circulation through today, I offer a different take on the relationship between people and things, one that shows alternative scales of valuation at work in Ostalgie. In contrast to reunified Germany where socialist products were swiftly deemed disposable and obsolete (Betts Reference Betts2000; Bach Reference Bach2017)—consigning GDR material culture to the “dustbin of history” (Berdahl Reference Berdahl2005b: 163)—in Vietnam, GDR goods did not lose their symbolic power and meaning. In the cases I discuss below, they retained their fetishized properties as desirable and inalienable foreign commodities, where source and producer—East Germany—functioned as a guarantor of quality and a marker of goodwill (Manning Reference Manning2010: 37). The indexical relationship that formed in Vietnam between source and product shows that the significance of production sites to value and legitimacy cannot be explained by neoliberal logics alone (Vann Reference Vann2005: 484). Rather, a longer history of socialist evaluations of craftsmanship and utility (Fehérváry Reference Fehérváry2009: 445) allowed for GDR material culture to be upheld as “German-made” products of superior design and durability.

Shifting the lens to the postcolonial South thus not only allows for subaltern claims to East German memory through distinctive identifications with Ostprodukte, or East products. It also provincializes the capitalist West as cathartic object of desire and fantasy (Veenis Reference Veenis1999; Berdahl Reference Berdahl2005a; Yurchak Reference Yurchak2006). Readers may recognize the essay’s title as inspired by Tim O’Brien’s acclaimed Reference O’Brien1990 novel on the sentimental objects, including talismans, that U.S. soldiers carried to Vietnam in wartime for emotional and material security; objects that were accomplices in the project of imperial domination. In this essay, I approach the transport of objects to Vietnam from a rival viewpoint: that of the victor, whose actions were intended to mitigate the suffering wrought by American imperialism. To pivot away from the dominance of western consumer society demands a spatial reorientation—after all, Vietnamese migrants headed West (đi Tây) to socialist Europe—as well as a recalibration of abundance and scarcity, notions that scholars have described as relative (Berdahl Reference Berdahl2005a: 241). Only then is it possible to understand the transformative role that GDR consumer culture played in the postcolonial remaking of destroyed material worlds, and how those efficacious objects formed the basis of a narrative of uplift and survival that distinguishes Ostalgie in the global South from that of reunified Germany.

The enchantment of Socialist things

There is much to gain from applying a socialist lens to bear on the “material turn,” which rethinks longstanding assumptions about the nature of matter and the dualistic relationship between subjectivity and materiality, or between people and things. With its emphasis on objects as animated matter that possess a spirit or vitality (Bennett Reference Bennett2009), new materialism scholarship intersects in generative ways with early socialist formulations of objects as active participants in, if not catalysts of radical social change in the material construction of socialism (Kiaer Reference Christina2005: 1). In this essay, I refer to those objects with transformative potential, produced through collective ownership of the means of production and imagined to redraw the lines between people and materiality with the goal to build a new society, as “socialist things.”

Soviet theorists long debated the role and form of mass-produced consumer goods under a dictatorship of the proletariat. Influenced by Marx’s assertion that a commodity was by its very nature not a thing but a concealed social relation (and product of alienated labor), Stalin advocated a form of non-capitalist commodity production to serve individual consumption and socialist construction, a view which gained traction in the People’s Republic of China (Coderre Reference Coderre2019: 31–32). Likewise, under Mao, commodities—though restricted and uncommercial—became a “necessary evil” to avoid scarcity and to meet the needs of the masses while advancing toward communism (ibid.: 45). At the center of these debates about socialist modernity was the question of how to forge a nonalienated relationship between people (the proletariat) and objects (products of their labor), or, as Constructivists framed it several decades earlier: how to transform the passive capitalist commodity into an active socialist thing (Kiaer Reference Christina2005: 30).

Writing in the same time period, Walter Benjamin (Reference Benjamin, Arendt and Zohn1969[1936]) contemplated changes in people’s sensory perception of art objects altered by technology (mass reproduction) that led to a decay of the aura. The phantasmagorical quality of the capitalist commodity, with its illusory pleasures associated with the possession of novelty, he argued in The Arcades Project, offered a false sense of newness and progress in modern life that was “little capable of furnishing … a liberating solution” (Reference Benjamin, Eiland and McLaughlin1999: 15). The task then for communism, according to Susan Buck-Morss’ interpretation of Benjamin, was to “undo the alienation of the corporeal sensorium” that makes it “possible for humanity to view its own destruction with enjoyment” (Reference Buck-Morss1992: 5, 37), thereby exposing the social facts and relations concealed and “congealed in the form of things” (Benjamin Reference Benjamin, Eiland and McLaughlin1999: 14). Unleashing the revolutionary potential of mass-produced objects to liberate the proletariat would then require industrial technologies to “amplify sensory experience, rather than sedate or lull it,” as occurred under conditions of capitalism (Kiaer Reference Christina2005: 37).

Constructivists imagined socialist utilitarian objects as distinct from passive, static, and anaesthetized capitalist commodities that were bought and sold for profit. Rather, affectively charged objects for everyday modern life had emancipatory if not agentic capacities or affordances as “comrades” in revolution and “coworkers” in building socialism (ibid.).Footnote 8 In language strikingly similar to the ideas of much later, post-humanist theorizations of relational assemblages, socialist material culture had the radical potential to eliminate the “rupture between Things and people that characterized bourgeois society,” as Boris Arvatov wrote in “Everyday Life and the Culture of Things” (Reference Arvatov1997[1925]: 121). Arvatov’s desire to understand the collective of individuals and objects as the most fundamental, defining feature of social relations (ibid.: 120) resonates with Latour’s efforts to “abandon the subject-object dichotomy” that precludes an understanding of human-nonhuman collectivities (1999: 180).

This distinction between the “dead” and abstracted capitalist commodity in the West and the liberating and transcendent socialist object in the East suggests a false dichotomy. State-produced goods with “spiritual qualities” (Betts Reference Betts2004: 91) were quickly turned by Vietnamese migrants into speculative commodities that moved between centrally planned economies and market settings, circulating in different regimes of value across space (the GDR and Vietnam) and time (pre- and post-Wende). In their mobility across categories and borders, these ordinary objects were afforded charismatic, almost quasi-magical properties that, like Durkheimian mana, were imagined to possess the capacity to alter the course of events. Unlike the “oppressive” material culture that negatively impacted border-crossing migrants (De León Reference De León2012: 478), here migrant material culture was framed as redemptive and enabling; it did not take life but fatefully ensured it (Durkheim Reference Durkheim2001: 145).

To illustrate, I recount a story about the cunning ways that returning migrants used their bodies as a medium of deception to transport surfeit goods by air, as told to me by a respondent in Hanoi. Overflowing luggage—stuffed with dismantled motorbikes, the parts wrapped in textiles with valuables hidden in fuel tanks—left returnees few options to export goods other than dressing their bodies in layers of clothing—pants over pants, shirts under sweaters under jackets, caps pushed into hats—in an effort to evade detection by custom officials. One male worker who had finished his five-year contract, the story went, was returning from East Germany on an Interflug flight when it was hijacked. The terrorists proceeded to shoot dead several passengers, and in the chaos that ensued, the Vietnamese man was hit by an errant bullet in the chest. Miraculously, he survived, owing to a steel shield of bicycle and motorbike chains that he had wrapped around his body to avoid paying excess baggage fees, which saved his life.

We might turn to Barthes (Reference Barthes and Cape1972) and his idea of myth as a metalanguage to peel back the layers of signification at work in this narrative of chains as an allegorical object that, in a moment of danger, transformed a banal technology draped over bodies into a protective amulet that possessed the vital energy to influence the outcome of human actions (Tambiah Reference Tambiah1984: 199). The mythFootnote 9 of the chain as a supranormal entity that grants both freedom and security functions at two levels of signification. At the primary level of signification, the chain denotes a dynamic object that rescued the individual body at risk—a hapless man in the path of gun-wielding hijackers. But another, deeper layer of meaning, or what Barthes called the “second-order” language where myth “settles” (Reference Barthes and Cape1972: 146), suggests the salvation of the impoverished social body, that of the Vietnamese nation. Therein lies the liberating potential of the socialist thing and its promise of survival and recovery.

Readers should note that bicycle chains figured prominently in stories told to me about the miseries of daily life during the subsidy years (through 1986), as people struggled to overcome acute postwar scarcities (see also Đặng Reference Phong2009). An indispensable, everyday technology in short supply, bicycle chains were a symbol of the indignities of poverty and restricted mobility, but also the ingenuity incumbent of an ethos of “making do.” Rhetorically, they offered an object-oriented view of the power of collective subsistence strategies made possible through material solidarities.Footnote 10 In interviews, people recounted how their work brigades shared the few bicycle chains their units had been allocated, rotating them among workers according to the day of the week. The image of the chainless bicycle—as a frame lacking the essential part that enables it to propel forward—is a powerful symbol of the national order of things in postwar Vietnam at the time. It is not surprising, then, that Vietnamese migrants used the opportunity to work or study abroad to amass easily transportable chains, and other goods, so much that an alarmed East German government issued limits on the number they could purchase and bring home (ten bicycle and one motorbike chain).Footnote 11

I use this story of the bicycle chain—an aspirational object endowed with certain redemptive powers and effects—to suggest a different relationship between people and things than found in scholarship on Ostalgie and the “revival” of impotent East German goods (Cliver Reference Cliver2014: 628). But not just any object was imbued with potent qualities to rescue the self and nation. As Tambiah argued of amulets, source is important (Reference Tambiah1984: 199). For reasons I make clear below, enchanted socialist objects often had their origins in East Germany, a country that many Vietnamese associated with modernity and high-quality goods. To understand how a banal technology, mass produced in East Germany, became a migrant’s good-luck charm of sorts, we first need to ask: what virtues, qualities, and values did these objects possess for their carriers, before examining how those attributes—the object’s identity—changed across space and time.

Cornucopias of Socialism: rethinking Scarcity

An indelible memory I possess of life in eastern Berlin after reunification were the piles of discarded, used furniture in derelict urban spaces that students and artists from “the West” mined for apartment furnishings and décor. Cast off as useless and antiquated relics of a grim and discredited past, the mass devaluation of socialist things came to stand for the devaluation of all things socialist. This image stuck with me as I began my graduate research several years later in another transitional socialist context, that of Vietnam, and started to see and hear about the quality of goods that had been made in the GDR. Unlike my experience in reunified Germany, the GDR things I encountered in northern Vietnam over the following years, like the IFA W50 truck still driven in some provinces today, including in the GDR-rebuilt city of Vinh where I conducted fieldwork (Schwenkel Reference Schwenkel2020), did not signify “difficult heritage” (Macdonald Reference Macdonald2009). Nor did they indicate radical temporal alterity like the devalued Trabant car, whose former status as a “highly prized luxury possession” (Berdahl Reference Berdahl2001: 132) serves as a reminder that shifting regimes of value are context specific and not intrinsic to a thing or technology (Appadurai Reference Appadurai and Appadurai1986). Instead, GDR things in Vietnam were tethered to a spatial imaginary of superior German technology (công nghệ Đức) that undermined the dualism that has come to define, distinguish, and hierarchize the two Germanys. Understanding this system of signification compels us to not only provincialize the West as site of super-modernity but also to rethink the taken-for-granted myth of East German provincialism that has upheld such persistent Cold War binaries (Hosek Reference Hosek2011). My interlocuters thus challenged hegemonic, Western-centric discourse that takes “Germany” to stand in for the FRG, by using it to signify and legitimize the East.

There is a rich body of literature on consumer culture and material practices under state socialism that emphasizes the human agency and creative, income-generating activities that materialized in largely inflexible systems to constitute an unofficial, “second economy” (Verdery Reference Verdery1996: 114–15). While I find this scholarship generative to think with, the lack of attention to race and subaltern perspectives—the non-elite migrants from Asia, Africa, and Latin America—allows for certain axiomatic truths to remain unchallenged. For example, like my critique of Ostalgie, much of this literature assumes an unmarked white Western subject, which inadvertently effaces other understandings of material culture and thus inadvertently imposes its own form of homogeneity on the “homogenized lifestyles” that it describes (Betts Reference Betts2000: 734). Discussions of black-market trade, for instance, rarely includes the experiences of racialized Others, even though, as Raia Apostalova (Reference Apostalova2017) has shown in the case of Bulgaria, migrant workers from Vietnam were conveniently blamed for the collapse of communism owing to the vast underground trade networks they established across Eastern Europe.Footnote 12 In this narrative, socialism did not fail because it could not deliver the goods (Borneman Reference Borneman1992), but because the delivered goods were transported elsewhere, a scapegoat mythology that also held currency in East Germany and justified the increased levels of policing to which Vietnamese migrants were subjected.

Because the conceptual starting point in this literature tends to be that of scarcity—with recurring motifs of long queues and empty shelves that defined “the socialist experience”—scholars have taken great pains to first establish that there was a “genuine consumer culture” (Betts Reference Betts2000: 734). The fallout from this “paradigm of shortage,” Krisztina Fehérváry (Reference Fehérváry2009: 428) argues, has been more attention paid in the literature to “absence and deprivation as objects of analysis” than to the “tangible material worlds produced by the state” (ibid.). Discussion of those material worlds has largely been framed by a triad of intrinsic design deficiencies: state-produced goods lacked quality, style, and diversity (ibid.: 444). Products tasted bad, fell apart, looked plain, lacked novelty, and rarely functioned as planned. We might return to the iconic Trabi—an emblem of technological “inefficiency, backwardness and inferiority” (Berdahl Reference Berdahl1999: 133)—to see how socialist design became a metonym for the socialist system itself.

What if, however, the starting point of materiality was not a condition of lack and want, but one of abundance and opportunity? We might see that this paradigm of shortage assumes a Western subject position, which overlooks postcolonial consumer practices and imaginaries of state socialist production that flip the triad to inscribe onto the socialist object an alternative system of value and meaning. Instead of intrinsic deficiency, the virtuous properties of socialist goods consumed by Others were often valued for their mark of distinction and craftsmanship. Frequent terms used by my interlocuters to describe GDR material culture included “high quality” (chất lượng cao), durable (kiên cố), solid (chắc), well-designed (thiết kế tốt), and aesthetic (đẹp).Footnote 13 When viewed through a Southern lens, the fantasy of socialist modernity and its associated forms of longing displace the “fetishism of western material culture” (Bach Reference Bach2002: 548) from dominant understandings of Ostalgie. A spatial framework that insists on desire and identity in relation to “the West” is less useful for examining postcolonial consumption in “the East” precisely because it overlooks the seduction associated with narratives of socialist modernization that acquired meaning relative to an elsewhere of privation.Footnote 14 For example, Vietnamese students and labor migrants who traveled to the East bloc carried hopeful visions of the socialist good life and, in interviews, they often deployed utopian imagery to describe their time overseas. The words of a respondent from Hanoi who studied in Dresden in the late 1970s captured this dreamworld as an escape from the hardships of poverty: “We used to say that East Germany was a paradise (thiên đường).Footnote 15 It was an industrialized country and everything functioned well. Life was easy. There were cheap trains that we took without problems, and there was always enough to eat. Our housing was modern with indoor plumbing. The quality of life was much higher than in Vietnam.”

Recurrent themes of functioning modern things—technical infrastructure, food security, material plenitude, and urban mobility—peppered interviews and placed East Germany at the top of a hierarchy of socialist modernity, as a land ripe with consumer—and entrepreneurial—possibilities. To be sure, respondents were well aware of the limits of socialism’s material prospects, which shaped how they navigated and circumvented the state-distribution system. But their accounts of GDR material culture afforded them a different temporal sensibility—as contemporary and liberating from postwar backwardness with its promises of long-awaited normalcy.

Accumulation of Socialist things

There is a small but growing literature on socialist globalization during the Cold War (e.g., Mark, Kalinovsky, and Marung Reference Mark, Kalinovsky and Marung2020; Bockman Reference Bockman2015), and an even smaller subset of scholarship on “socialist mobilities” (Schwenkel Reference Schwenkel2015) between the so-called Second and Third Worlds as part of regimes of technical training to rebuild countries destroyed by imperialism. This literature challenges the trope of socialist isolation that denies coevalness by positing a linear advance from premodern, communist stasis to capitalist integration and development. More importantly for this essay, it suggests that socialist societies were not entirely homogeneous owing to their racial solidarity projects that aimed to technologically uplift countries in the throes of decolonization. It should be noted that East German modernization projects in northern Vietnam left a strong material and infrastructural imprint on the landscape, which contributed to the fantasy of its socialist technological modernity, including housing, schools, hospitals, and factories, some of which were branded with the logo “Việt Đức” (Vietnam-Germany, also abbreviated as VĐ), as a distinctive sign of “materialized goodwill” (Foster Reference Foster Robert2008: 79). The repurposed material relics of solidarity—from large-scale machinery, equipment, and vehicles to the less spectacular, more intimate “everyday technologies” (Arnold Reference Arnold2013), like the bicycle chain, have been formative of subjectivities and fostered a positive identification in Vietnam with GDR-produced things.

Educational aid to facilitate skill “transfers” saw a focus on the development of indigenous expertise through overseas training. After the defeat of French colonialism in 1954, support for the economic and technological development of an independent Vietnam coalesced in a series of diplomatic initiatives aimed at producing a skilled and professional labor force that would lay the foundations for the scientific and economic development of state socialism. Between 1955 and 1990, close to three hundred thousand Vietnamese men and women went to study, train, and work in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe. East Germany ranked second in the number of recipients after the Soviet Union with approximately ninety thousand Vietnamese students, apprentices, and low-skilled laborers (Weiss and Dennis Reference Weiss and Dennis2005), the latter of whom formed the majority of migrants in the 1980s when a floundering GDR economy hastened a shift from altruistic forms of skills assistance to agreements that prioritized national self-interest (Alamgir and Schwenkel Reference Alamgir, Schwenkel, Mark, Kalinovsky and Marung2020: 109).

The opportunity to work or study in East Germany for an extended period of time—usually between five to seven years—made it possible for Vietnamese migrants to save their stipends or earnings to support their families back home, much as international migrants do today. However, because value lay in commodities rather than currency, owing to the inconvertibility of the East mark, remittances centered not on financial transfers (unlike current worldwide remittance flows) but on the transfer of goods, which could then be turned into hard currency or Vietnamese đồng. The remittance of material goods, including vehicles (bicycles and motorbikes) and their spare parts, electronics (radios and cameras), textiles and clothing, kitchen items (pots, teakettles, and dishware), household goods (soap and blankets), comestibles (cocoa, sugar, and candy), children’s toys, and domestic technologies like sewing machines and electric kettles subsequently found their way into households and marketplaces across Vietnam.

Because GDR goods were in high demand and had convertible values, they could be used, banked, and transacted as needed. Prestige objects from overseas circulated within entangled economies of exchange (Thomas Reference Thomas1991)—market, gift, and household—that were embedded in social relationships and governed by ethical rules and expectations. They were also governed by legal regulations: according to East German customs law from 1968, migrants were permitted the duty-free export of purchased goods with a value of no more than 50 percent of total earnings for “personal use” only (persönlicher Gebrauch), and decisively not for “speculative profit” (spekulativer Gewinn).Footnote 16

But the lines between non-capitalist and capitalist circulations of goods as outlined by the GDR government—or spheres of intimate and obligatory gift exchange and alienated and impersonal commodity exchange (Carrier Reference Carrier1995)—were often blurry for Vietnamese returning with baggage or crates of goods. As anthropologists have shown, these kinds of distinctions between people and things, and the manner and meaning of their exchange, are always messier on the ground owing to the mutability of objects that shift identities as they move between inalienable and alienable property, or processes of de/commodification (Appadurai Reference Appadurai and Appadurai1986: 29). Accordingly, because of their interchangeability, and in clear defiance of authorities, GDR objects could similarly move among multiple, coexisting paths of exchange as gifts, commodities, or utilitarian possessions (Aswani and Sheppard Reference Aswani and Sheppard2003). For example, research respondents typically differentiated between the types of goods they sent home based on their intention to sell or to use and later transact, in addition to goods intended as gifts or favors and those not meant for circulation at all. This conversion of value was not without ethical dilemmas, however. Moral hierarchies that distinguished forms of exchange placed market activities at the bottom of socialist civilization. Like the famed anthropological example of Tiv commodity spheres, converting “downward” was considered “shameful and only done under extreme duress” (Kopytoff Reference Kopytoff and Appadurai1986: 71). Among my interlocuters, such conversions produced feelings of ambivalence and often embarrassment, and reified social and moral distinctions between social groups and waves of migrants.

In the early years of educational aid, which corresponded to American intervention in Vietnam (1955–1975), Vietnamese students and trainees in the GDR had limited purchasing power owing to low stipends. Like scholars observed of life in the USSR (see Đặng Reference Phong2009), this was a time when Vietnamese nationals could only engage in the small-scale procurement of goods, largely for their own consumption back home, transported in their baggage on the train. Wartime disruptions to transport infrastructure further limited the scale of goods that migrants could carry or send back to Vietnam. Consequently, there was little to no speculative trafficking in GDR goods at this time. In interviews, former students expressed fear of violating German law and being sent home to the battlefield. Owing to the watchful eye of their embassy, students were advised to show their patriotism and gratitude by focusing on their studies and not engaging in public consumption or leisure practices, like going to the movies. They were instructed to lead austere lives away from the public eye. As educated elites, students were especially reticent to discuss their trading activities with me, more than apprentices or workers given the deep antipathy in Vietnam toward traders and profiteering. While my interlocuters refused at times to draw clear lines between commercial goods and possessions for personal use, like the GDR government did, they were well aware of the stigma ascribed to the former and the status attached to the latter in Vietnam.

To give an example of early circulations of migrant material culture: one of my main interlocuters had studied architecture in Weimar between 1966 and 1972. He received a stipend from the GDR government of 270 East marks per month, 100 of which went to food and 30 for dormitory housing. He also put aside money for clothing, school supplies, and other essential goods. The rest he saved, yet occasionally he dipped into his reserves to travel around the country on holidays, which contributed to his cosmopolitan sensibility, but also produced feelings of guilt given his privileged position relative to his peers who had been sent to the front.Footnote 17 He earned extra money in the summertime picking potatoes or strawberries during the harvest season, as Vietnamese students in Poland and the Soviet Union also recounted to me in interviews. At the end of his studies, he used his savings to purchase gifts to take back to Vietnam, including a radio, two bicycles, and fabric, all of which traveled with him on the train via Moscow and Beijing (there were no flights in wartime), and which legally qualified as duty-free goods at the time, he was careful to point out. Most items were kept for use in his family with the exception of a bicycle and some yards of fabric, which his mother sold discreetly from his home to neighbors who heard of his return and inquired about the possibility to acquire quality foreign goods.

Both scale and spatiality framed his actions as a moral imperative on the basis of filial obligation. Modest transactions within the private sphere, not public market space, with minimal profits for survival instead of profiteering, were not considered socially contaminating but justified as a right to subsistence and to care for one’s family (see also Scott Reference Scott1976).Footnote 18 Still, he displayed some discomfort when recounting this story about the “status demotion” of socialist goods, as did several other former students. They, too, sought to distance themselves and their family members from the stigmatized image of traders and their tainted goods, as well as from that of low-skilled Vietnamese workers in the GDR, who in their view had stretched the rules too far.Footnote 19

Low-skilled contract workers had a more unabashed, speculative relationship to socialist commodities. By the 1980s, Vietnamese labor migrants—whose arrivals reached thirty thousand in 1988 aloneFootnote 20—had established vast underground trade networks that spanned Asia and Europe. A number of parallel developments accounted for the unprecedented growth in the scale of economic activity, including logistical changes in maritime and aviation transport opportunities. While freight services enabled increases in the volume of nonperishable goods traveling to Vietnam, aviation connectivity—due to closed rail lines after a border war broke out with China in 1979—increased the speed with which goods reached Vietnam. The illicit circulation of goods was multidirectional: migrants smuggled gold in to sell for East marks, which they then invested in large stocks of goods to ship out of the country. A 1983 report from the Planning and Finance Department of the Socialist Unity Party (SED) described an upward trend in the scale of illegal gold imports by Vietnamese workers. In Leipzig alone, between July 1982 and 1983, more than one million marks were exchanged for gold, which workers then used to purchase “high quality industrial goods” to export back to Vietnam.Footnote 21 At the same time, Vietnamese workers established new entrepreneurial ventures, like dorm-based sewing collectives to sell clothing, especially jeans, to East Germans (see also Dennis and LaPorte Reference Dennis and LaPorte2011: 101). No contract worker I interviewed for my research was not involved in some fashion in the unofficial or shadow economy, which offered numerous opportunities to augment their wages. The candid refrain, “We were there to make money,” contrasted with students’ ethical claims to knowledge acquisition as their primary motivation for migration, even though both groups were invested in the procurement of convertible-value things to lift their families out of poverty.

The accrual of East marks, together with covert arrangements with local shop keepers,Footnote 22 enabled the excessive purchasing and amassing of state-produced goods. The sheer volume of these acquisitions—with storage rooms and basements filled with stockpiled products, some of which never even made it into stores—attracted the attention of state security forces (the Stasi), who subjected groups of migrants to regimes of surveillance and discipline.Footnote 23 Reports about the smuggling of motorbikes described the cunning ways they were dismantled and packed into luggage or hidden in the doubled walls and fake bottoms of shipping containers (up to thirteen were found concealed in the secret compartments of a single container, according to one account). Another case reported to the SED in 1988 found a lone individual with 4,800 bicycle spokes, 340 bicycles chains, 835 ball bearings, 1,023 moped headlamps, and 420 kilograms of sugar, which the person justified as lawful on the basis of “family need” (familiärer Bedarf?>).Footnote 24

Overconsumption by racial Others subverted the SED’s emphasis on socialist production for use value only and created “Störungen” (disruptions) in the supply chain that prevented the adequate provision of goods to East German citizens, the party claimed.Footnote 25 As the trafficking of GDR commodities soared in the late 1980s, hostility towards migrants, the racial scapegoat for scarcity, increased. My Vietnamese interlocuters—especially former students who returned to the GDR as translators and brigade leaders of Vietnamese work units—remembered the acute shift in national sentiment from humanistic empathy and fondness (tình cảm) during the wartime years of anticolonial solidarity to rising resentment, xenophobia, and racial hatred (sự ghét).Footnote 26 In interviews, they recalled with embarrassment the discriminatory treatment they faced when shops began to hang signs that denied sales to Vietnamese (“không bán cho người Việt”) and competition escalated between migrant workers to "clear out store inventories" (tranh nhau để mua hết), leading to intergroup rivalries and conflicts.

In June 1988, the SED responded by instituting a new set of export regulations to limit quantities of the most desirable commodities that Vietnamese migrants sought to export duty free, including the chains they wrapped around their bodies to circumvent new policy.Footnote 27 This addendum to Article 15 of the 1980 labor agreement took its cue from the Soviet Union and Czechoslovakia, where similar measures had been taken with Vietnamese workers to prevent inequitable accumulation. Unlike in the West where “boat people” were emerging as law-abiding, model minorities (Bui Reference Bui2003), in the East, Vietnamese migrants were charged with the unlawful hoarding and conversion of need-based goods into merchandise (Handelswaren) for profiteering. They were the only migrants to do so, one SED document noted reproachfully: workers from Cuba, Angola, and Mozambique did not violate socialist tenets of ethical consumption seemingly. The racial matter of speculative trading was thus explicitly framed as a Vietnamese problem.Footnote 28

That the updated policy did little to impede the robust trade in GDR things exposed the state’s inability to control consumption and the distribution of its goods overseas. Despite objections by the Vietnamese government over the new limitations, migrants found alternative means to circumvent regulatory regimes on both sides of the export/import chain. They did so by mobilizing their social capital and consolidating their connections (quan hệ), while using intermediaries to dodge custom inspections, a reminder of the ways in which entrepreneurial activities are themselves “cultural forms” that draw their efficacy from sociocultural resources (Smart Reference Smart1993: 388). In interviews, former contract workers playfully recalled the cunning ways people “evaded the law” (lách luật), deploying third-person pronouns to maintain their own moral integrity. “I remember a girl who was 1.5 meters tall—only because of the ten fedoras (mũ phơt) she stacked on her head!” one man laughed. “Bribery stories,” or chuyện hối lộ (again, always about someone else), focused on the prestation of gifts, like cigarettes, on both ends to facilitate the movement of undeclared goods. Over time, Vietnamese demands for bribes (đút lót) involving money and material possessions escalated in tandem with the increase in value and volume of goods. One woman reported gifting (biếu) one of three Simson motorbikes she had smuggled, making Vietnamese port authorities in Hải Phòng “vô cùng giàu,” or exceptionally rich. In the GDR, on the other hand, customs agents often mistook bribery for gift exchange. The flexibility (linh hoạt) initially shown toward Vietnamese workers later turned to harsh (?> gắt gao) treatment, one Vietnamese man recalled, with the realization that departure “gifts” were not intended as symbolic tokens of affection but as impersonal payments or bribes, reducing the personal relationship to a corrupt economic transaction (Yang Reference Yang2002: 465; Smart Reference Smart1993: 399).

The Vietnamese government became increasingly dependent on these material remittances to mitigate its chronic “shortage economy” (Kornai Reference Kornai1980), in addition to the 12 percent homeland tax on worker’s salaries it received. Estimating that the average worker in the GDR amassed between 25 and 30 thousand East marks by the end of their five-year contracts, authorities disputed changes to policy that disrupted the steady flow of commodities to Vietnam, including the confiscation (bị tịch thu) of goods in excess of tax-free thresholds.Footnote 29 Not all workers violated customs regulations, however. Many took advantage of provisions that allowed shipments of twenty kilograms of goods, with a value up to 50 percent of their income, duty-free every two months.Footnote 30 And still others, concerned with providing regular, income-generating opportunities for their families, sent additional shipments at their own costs. One worker emphasized the critical role that GDR comestibles—as currency and not for personal consumption—played in combating hunger in his family. Choosing exchangeable goods based on durability (e.g., able to withstand the long journey) and profitability, he explained his logic: “I sent a box of cocoa home each month: ten cans for 69 marks, and 50 marks for customs and shipping.” The cans were then gifted to relatives or “downgraded” to a speculative object, which could be transacted quickly at the market, either sold or bartered for other commodities, like livestock (pigs) or poultry, which generated higher future returns. “The value of the ten cans of cocoa was enough for my family to live for a month,” he assessed. In these accounts of valuation, sacrifice, and survival, socialist goods were framed as liberating objects that rescued an impoverished population, or, in the words of one female professor and former student, as goods that functioned as “savior to the nation” (cứu sống của một dân tộc).

Ambiguity of Socialist things

Aside from their life-saving properties, the transnational trade and circulation of socialist commodities transformed the cultural and economic landscape in subsidy-era Vietnam as imported goods whetted the tastes and fantasies of the wider population. We can see this evolving landscape of imported things in popular love poems that listed the most desirable traits and possessions of prospective male suitors,Footnote 31 and in the rhymes of itinerant junk collectors recorded by the anthropologist Minh T. N. Nguyen (Reference Nguyen2016: 120). In the early 1980s, before the surge in socialist objects from overseas, waste traders called out for simple domestic recyclables, like glass bottles and frayed baskets. By the late-1980s, changes to their verses indexed shifts in the volume and types of household technologies imported from Eastern bloc countries, as the women called out for broken irons, fans, televisions, refrigerators, and radios (ibid.). Many of these items were included on the lists that respondents gave me of what they carried or sent home.

As socialist imports became more available at local markets, stratification between households with and without family members overseas became more evident through conspicuous displays of material wealth once unthinkable. This not only generated envy between neighbors, but also moral anxieties about inequality and realigned social hierarchies as non-elites (mostly workers) began to show signs of personal enrichment through their material practices. For example, after returning from overseas, it was not uncommon for migrant workers to sell their imported motorbikes to invest in small businessesFootnote 32 or to build a standalone house for their families: two Simsons could bring 9 to 10 taels, or up to 375 grams of gold (Schwenkel Reference Schwenkel2014: 250).

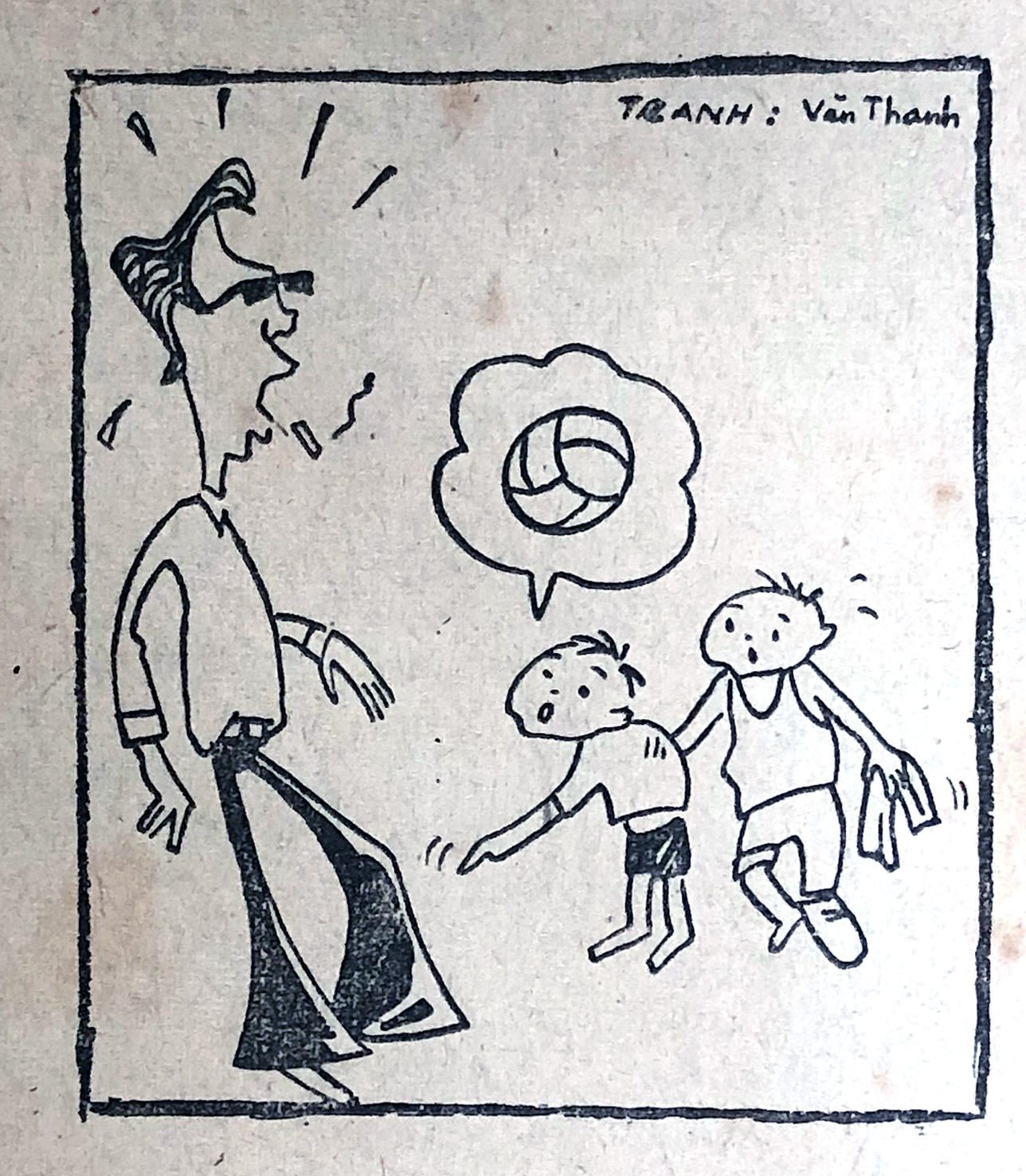

Fashion likewise changed, as did people’s subjectivities as objects reconfigured their social worlds. The relationship between materiality, consumption, and identity became more pronounced with the appearance of a new, undisciplined body and public presentation of self (Goffman Reference Goffman1959), which did not align with proper expressions of socialist personhood. Migrants who returned from overseas often looked and acted differently, which aroused suspicion in a society that frowned at decadent expressions of style, especially those emanating from Western culture. In a display of sovereign power, the Vietnamese state sought to discipline those returnees who displayed too strong an identification with foreign things and for whom consumption became an expression of individuality (cf. Humphrey Reference Humphrey2002: 40). For example, in the 1970s, returning students sometimes wore flared pants (quần loe) or grew their hair long, attracting the attention of the police, who carried scissors as their weapon of cultural enforcement. A woman in Vinh City recalled acts of state violence to maintain homogeneity: forcibly cutting pants and hair that symbolized excess and greed. Acting “like no other” (không giống ai) was deemed rebellious in a country where conformity was the expected norm. One Soviet-trained scientist in Hải Phòng recalled attending school as a young girl in her beloved bell-bottom jeans that an uncle in Moscow had given her; she was promptly sent home and ordered to change. The press scorned these “socialist hippies,” and depicted them in cartoons as morally tainted by hedonistic tendencies and a self-seeking materialism that, in depriving those with less, clashed with the collectivist and egalitarian values of socialism (see figure 1).Footnote 33

Figure 1. Returning students as over-consumers, Lao Động [Labor], 5 March 1975.

And yet these were highly sought-after commodities because of their associations with modernity and a socialist good life that had not yet materialized in Vietnam. Here we see differing perceptions of time in the circulation of socialist things. Contrary to Eastern Europe, where state-produced goods “constrained consumers in their ability to represent to themselves and others their full participation in a modern present” (Fehérváry Reference Fehérváry2009: 452), in Vietnam the possession of these same socialist objects enabled people to make claims to modern subjectivity and to belonging in a modern world long denied them by imperialism. After all, this had been a difficult period of postwar recovery from attempts to bomb the country “back to the Stone Age,” and consumption of foreign goods accelerated people’s ability to “catch up” with modern times. To wear a woolen coat, listen to a music tape, or possess a camera with film was a means to affirm a cosmopolitan sensibility and experience of shared contemporaneity not readily available to others. Hence, an interlocuter’s identification with John Lennon, whose death he mourned with the rest of the world, he told me, while studying in Prague, and whose music he continues to play in a Hanoi neighborhood bar.

This aspiration to coevalness and inclusion in modernity trickled down to the masses—to non-migrants whose desires to possess symbolic markers of distinction shaped their individual action and expression; for example, in the gifted bell bottoms valued for both functionality and fashionability. These affective attachments to socialist things considered distinctive in the global South set them apart from their abjectness in East Germany, best captured in Paul Betts’ reference to GDR goods as “begrudged objects of disaffection” (Reference Betts2000: 762; but see Berdahl Reference Berdahl2001). The yearning for material possessions from the socialist North was met with cynicism and concerns about differing moral sensibilities given the social relation of inequality between the possessor and dispossessed that defined one’s very distinction (Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu and Nice1984: 395). A case in point: one man who worked at the Swedish-built Bãi Bằng paper mill in Phú Thọ province traveled several hundred miles to the port of Hải Phòng to wait for the ship from East Germany carrying containers of migrant-purchased goods to dock. With savings he earned from covertly selling noodles and milk powder gifted from Swedish experts, he purchased a costly Diamant bicycle for his wife, which, now retired, she still occasionally uses and refuses to sell. A decommodified but not devalued socialist thing, the GDR bicycle was unique at the time in their neighborhood where few people had the opportunity to work or study overseas.

The man’s reluctance to share the details of this story—given the stigma attached to black market trade (and to men acting as traders [Leshkowich Reference Leshkowich2011]), but also to the possession that made his family stand out—serves as a reminder of the ambivalence felt toward the convertibility of the socialist thing and the chain of illicit actions it spawned: from an object meant to satisfy the needs of society to a profitable, foreign commodity turned gift and inalienable possession. The wife, on the other hand, saw her husband’s gesture as “honorable” (vinh dự), as an expression of his affection that brought distinction to the family through an icon of European modernity (Arnold and DeWald Reference Arnold and DeWald2011: 973) that also aroused suspicion.

Imported socialist products were thus fraught and morally ambiguous boundary markers that inscribed social hierarchies. They were the stuff of dreams of normalcy and aspirations to modernity, and yet also dangerous and polluting matter linked to unlawful trade and profit among some, and hippy hedonism or conspicuous individualism among others, all of which were morally suspect if not counter-revolutionary. After all, Vietnamese students had been warned not to “betray the revolution” by adopting a bourgeoise lifestyle in East Germany (Grossheim Reference Grossheim2005: 467). Nor were they to bring western cultural practices home. And yet these essential commodities made up for the lack of state production and provision of care by shifting material responsibilities to family and extended kin. The association of consumer goods with socialist futurity proved threatening to governing authorities. The goods that kept the economy precariously afloat risked undermining state and party legitimacy by revealing socialist societies elsewhere that enjoyed material prosperity and modern ways of life that migrants sought to emulate at home.

Afterlives of Socialist things

Up to this point, I have argued that the spatial and temporal relationship between Vietnamese migrants and GDR things offers an alternative perspective on Ostalgie and the ways in which socialism was entwined with the consumption of goods deemed modern, desirable, and transformative rather than backwards and deficient. I have pointed to the potent, and at times almost phantasmic (Baudrillard Reference Baudrillard and Levin2019: 206) capacities of objects as active participants in social change that made it possible to imagine new material worlds and forms of modern selfhood. In contrast to scholarship on reunified Germany, GDR goods in Vietnam did not vanish only to stage a “remarkable comeback,” or rebirth, to enjoy a more en vogue “second life” (Blum Reference Blum2000: 229–30) after the collapse of European communism. Rather, socialist material culture in “foreign” places, like Vietnam, represented a wholly different experience of time and consumption. As the example of the bicycle further shows, such goods were embedded in other cultural systems of meaning that did not unequivocally lose their status to become romanticized or commercialized “neokitsch” (Bach Reference Bach2002: 547), the stuff of nostalgia. With these floating signifiers, it is ironic that when German tourists to Vietnam spot GDR vehicles or other objects still in use, often in rural areas, they often respond with incredulity and record the “anachronisms” on film and social media. Such responses suggest a transported Ostalgie that affirms Vietnam’s temporal Otherness, as “still in the socialist past” rather than its modern present. That said, there are ways in which the afterlives of GDR material culture in Vietnam and its resurrected lives in Germany overlapped through a shared sense of loss and dislocation that strengthened people’s bonds to symbolic socialist things.

To contextualize these nostalgic sentiments: Vietnamese migrants returned from reunified Germany to face new socioeconomic vulnerabilities, including labor precarity as they found no work in the fields in which they had been trained. Economic restructuring had closed factories, leaving repatriated, low-skilled workers to confront unemployment.Footnote 34 Like in East Germany (see Boyer Reference Boyer2001), a new knowledge economy that devalued socialist, domain-specific expertise led to the depreciation of professional skills obtained overseas.Footnote 35 A deep sense of disenchantment emerged among the chosen “nation builders” who were once economically and geographically mobile under socialism, but then found themselves facing downward mobility with market-oriented reforms (Schwenkel Reference Schwenkel2014).

With the inconvertibility of cultural capital, material assets—namely, goods from overseas—afforded the capacity to maintain a social status and worldly subjectivity that diminished after return to Vietnam. Here we see overlap with conventional forms of Ostalgie and its “reclaiming of a devalued self” (Berdahl Reference Berdahl2001: 137), though in the example I provide below of a home visit, there were important gender dimensions at play as men, in particular, grappled with the loss of a masculine identity as globetrotting, paternal providers. Their bonds with East German objects, as emblems of their male expertise, exemplified the ways in which expressions of personhood were constituted in and through the use of everyday things (Zubrzycki Reference Zubrzycki and Zubrzycki2017: 4), onto which they projected an image of the idealized self and family.

Unlike the post-unification purging of consumer goods in East Germany, GDR material culture was not discarded en masse in Vietnam after the dismantling of the “iron curtain.” This is not to argue that value and meaning were static across time. On the contrary, eventually some objects were recycled by junk traders, while other technologies, like Simson motorbikes, became less desirable as competing brands came onto the scene from the Asian East, like Honda Cubs. But even there, consumption of newly imported items was less substitutive than it was accumulative, for instance allowing families to possess a larger number of motorized vehicles from multiple centers of production (see figure 2). Other GDR things took on heightened meaning among my interlocuters as the socialist past—and the materiality associated with it, like architecture—came under threat of elimination. There was a slow chiseling away at socialist memory, including under pressure from the German embassy in Hanoi that resulted, for example, in the renaming of GDR friendship hospitals and technical schools. This had a strong impact on certain social groups owing to the many people, including migrants, who benefitted from the history of “solidarity.” In the following ethnographic account, I will show how the private home became a space for performative enactments of Vietnamese modernity through everyday practices involving ordinary GDR things to counter forgetting and to maintain a sense of dignity as an urbane “cosmopolitan patriot” (Appiah Reference Appiah1997).

Figure 2. Simson motorbike parked in a courtyard in Hanoi, September 2020. Author’s photo.

To set the scene, let me begin at the thirty-fifth anniversary celebration of Việt Đức (Vietnam-Germany) relations in Vinh City in 2010.Footnote 36 There I met three middle-aged men who had studied in the GDR in the 1970s: Khiên had attended the police academy in Magdeburg; Long, a wounded veteran, had trained in optometry in Jena; and Hoàng had studied engineering in Leipzig. Hoàng, like Long, had been selected to study abroad on account of his family’s “priority” (ưu tiên) status: four of his brothers had served on the battlefront, all of whom returned. Hoàng recalled that he had been able to send only a few packages to his family during his studies because of the air war and his low monthly stipend (270 East marks). But, owing to his German language fluency, he was able to return to East Germany in 1987 as the group leader of a brigade of female workers in light industry. During his second tour, he engaged in limited, small-scale trade to augment his monthly salary of one thousand marks, but nothing on the scale of the workers, he said, distancing himself from their larger and more speculative operations. Still, he earned enough to invest in a large container of goods, the contents of which his family sold or traded on the black market. With the returns he built a single-family home in the city center, close to the university, and moved his family out of collective housing after his 1992 repatriation and subsequent unemployment.

With the steep decline of state-sector jobs that followed economic reforms, Hoàng turned to the private sector to market his language skills. Today he works as a freelance translator for legal services to assist Vietnamese in Germany applying for residency. He also teaches German to university students who plan to study overseas. My visit to Hoàng’s spacious home gave me the opportunity to observe the ways he expressed his close affinities with Germany through objects and actions that conveyed his European sensibility and modern lifestyle. “Everything I have I owe to Germany,” he told me proudly as he showed me around the house, including the “German-style” kitchen built for his wife, evoking the narrative of East German salvation through modern socialist things procured by men to provide for their families. He had reluctantly sold his “banked” prized possessions—a fur mantle and a motorbike—when they needed the gold. After introducing me to his son—named Đức after Germany, he laughed—he invited me to sit down while he prepared some tea, a common gesture of Vietnamese hospitality. But the objects he used in the ritual broke with conventional cultural practice. Instead of serving strong green tea in small sipper cups, as I had come to expect, he poured the steaming liquid into elegant porcelain teacups. Underneath the matching floral saucer, the origin stamp he showed me—MADE IN GDR—amplified the value and meaning of his china collection as authentic, “source products” manufactured overseas in Germany (Vann Reference Vann2005: 476).

In his presentation of a stable, modern self in a quickly changing city, Hoàng refused to realign his material life with the new world taking shape around him. Elsewhere (2020), I have documented feelings of skepticism about the “new modern” among residents in East German-built housing who refused to move into “inferior,” domestic-built high rises owing to cultural perceptions of the quality of German engineering. Likewise, the mundane everyday objects in Hoàng’s home were granted a similar “timeless” status, despite their seeming obsolescence. As we drank tea and discussed his time overseas, Hoàng jumped up to grab a map and returned with a Cold War-era Atlas für Jedermann (People’s atlas) printed in East Germany in 1983, with loose pages falling out. He also saw no reason to update the German dictionary that he used for teaching, which he brought back from Leipzig along with novels he displayed on the shelf. Fehérváry has discussed the labor required to adjust one’s material culture to remain “of the present” in a post-socialist context (Reference Fehérváry2009: 451). But for Hoàng, his GDR possessions were that modern present; although cheap and readily available, Vietnam-printed materials did not possess the same symbolic capital and value as “imported” things.

Everyday GDR commodities still in use in households—dishware, books, sewing machines, bicycles, motorbikes, radios, and luggage (with Interflug tags still attached)—gave Hoàng and the other returnees I visited a way to carve out a place in a new socioeconomic order from which they felt excluded. Despite difficulties with family separation, many migrants of Hoàng’s generation experienced an exhilarating sense of inclusion in a larger collectivity under socialism and the ability to participate in postcolonial nation building as “socialist moderns” (Bayly Reference Bayly2007). As expressive symbols of those feelings, the things people carried—draped on bodies and stuffed into baggage or containers—and kept, offset sentiments of national disaffection owing to the loss of social mobility and global connectivity upon their return to Vietnam. The ongoing possession and use of Ostprodukte signified ownership not only of affectively charged objects linked to technology, worldliness, modernity, and a hopeful return to normalcy. Like the collection of Mao badges in present-day China (Hubbert Reference Hubbert2006: 146), the care and curation of socialist commodities made a particular claim to ownership of history and to attending to that history in order to control the narrative, that is, the story that objects told about people’s lives, and the meanings and memories they hold through today, as the narrative about the past continues to change.

Conclusion: the future of Socialist things

This essay has sought to expand the scope of Ostalgie to include postcolonial perspectives on the ways in which materiality and fantasies about modernity were entwined under socialism. I have argued that paying attention to racial Others and to the spatial dimensions of material practices beyond the German nation-state offers novel, more inclusive perspectives on Ostalgie and the legacies of GDR material culture that unsettle white normativity in the study of cultural memory. GDR things in Vietnam, I have shown, embodied a radically different temporal register as they enabled consumers to propel themselves forward in time, rather than tumble backwards, as West Germans commonly described the East (Boyer Reference Boyer2006: 373). Instead, my interlocuters linked East German commodities to technological utility and branded “Germanness” as an intrinsic quality that mediated future possibility (Keane Reference Keane2003: 418), even as new commodities became available on the market.

GDR material culture in Vietnam stored and communicated memory, subjectivity, and value in ways that diverged from the material culture at the center of conventional approaches to Ostalgie. This reminds us that it is impossible to stabilize the meaning and identity of a thing that is itself always in the process of becoming (Thomas Reference Thomas1991: 4). As such, some objects continued to carry economic value and could be transacted fairly quickly, such as a Simson motorbike that sold online for US$700 in 2015. Other objects conveyed people’s cultural capital, such as the European tea ritual. In the space of people’s homes, GDR material culture was highly charged with affect insofar as it evoked formative experiences and connections to the socialist past—a sentimentalized history of belonging and of participating in a broad movement of international solidarity that imagined, and sought to build, a better, more just future.

There are ways in which the cross-border legacies of GDR materiality have intersected with those in present-day Germany. Increasingly, GDR goods in Vietnam have been recognized as having historical value. Some have become nostalgic family objects on display in restaurants or cafes like in Berlin today. Others have been removed from commodity circulation—“singularized” (Koptytoff Reference Kopytoff and Appadurai1986) for protection and collection, not unlike the musealization of everyday objects in eastern German cities. Socialist things held distinctive value and significance for social and cultural life in Vietnam, however, and narrated profoundly different material histories, including savior narratives that afforded mundane objects agency. When I visited the renowned war photographer Mai Nam before his passing, he pointed to his cherished East German Praktica camera that hung on the wall with a lodged bullet in its metal body, which had protected him from death on the battlefield, he told me—yet another example of a socialist object-turned-amulet not unlike the bicycle chain in the hijacking incident.

Other artefacts have been displayed in museums for public viewing. In the 2007 exhibit on the subsidy era at the Museum of Ethnology in Hanoi, socialist commodities were presented for the first time as historical objects worthy of preservation (see also MacLean Reference MacLean2008). In keeping with Vietnamese representational practices, the exhibit on a “difficult past” was made palatable by showing a more optimistic side to this era of suffering through the role that Ostprodukte played in national (and paternal) recovery. One display centered on a trendy winter coat and included a caption that captures the essence of my argument on Ostalgie and the efficacious quality of GDR things beyond Germany: “German fur coats were worth several taels of gold. When my wife went to East Germany, she brought one back. My colleagues persisted in trying to buy it from me, but I wouldn’t sell it, partly because it was valuable property, and partly because it was a family keepsake…. But above all, because a German fur coat was the pride of a man in those days—the most prestigious thing that he could own.”