In a lengthy letter to his father dated 3 December 1777, the young Mozart recounts his continuing difficulties in securing a court appointment in Mannheim. ‘I still can’t write anything definite about my situation here,’ he opines, despite ongoing assistance and advocacy by fellow musicians and court employees in the famed Mannheim Orchestra. Advocating on Mozart’s behalf were the current director of instrumental music and violinist Christian Cannabich, flautist Johann Baptist Wendling, oboist Friedrich Ramm, and Count Savioli, manager of the orchestra.Footnote 1 Discouraged by the elector’s ongoing equivocation, Mozart tells his father that he is thinking of travelling to Paris with Ramm and Wendling, since, based on their two prior visits, they report ‘it’s really the only place where you can make money and a good reputation for yourself’.Footnote 2 And in contrast to the limited opportunities available in Mannheim, which was essentially a one-court town, the possibilities for earning a living as a musician in the flourishing French capital must have appeared boundless. Ramm and Wendling, whom he would encounter a few months later in Paris,Footnote 3 likely also told him about the two musical organizations Mozart cites by name: ‘the Concert spirituell [sic], the academie des anateurs’ [sic].Footnote 4

With this brief reference to two of the main orchestras in Paris – the longstanding Concert spirituel and the more recent Concert des amateurs – Mozart summons up the silent musicians whose creative presence looms large in the next stage of his musical development. Mozart’s interactions with Cannabich’s counterpart at the Concert spiritual are known through the premiere of his ‘Paris’ Symphony in D major, no. 31 (K.297/300a) in June 1778 (discussed later). By comparison, the name of Joseph Bologne, Le Chevalier de Saint-George,Footnote 5 is mainly absent from biographical accounts of Mozart’s Parisian sojourn; if Saint-George is mentioned at all, it is typically in a brief aside or a footnote, or not at all. In this article I foreground this overlooked and underrepresented interracial composer-violinist in historical narratives of Mozart’s time in Paris by shifting traditional perspectives and writing him back into accounts of Mozart’s extended stay in the metropole.

My reasons for wanting to raise the profile of Bologne in musicological historiography are fourfold. First, Bologne was one of the most important musicians working in Paris during Mozart’s sojourn there in the spring and summer of 1778. As the leading virtuoso violinist in the French capital and the dynamic leader of the Concert des amateurs, one of the most enterprising orchestral ensembles in the city dedicated to performing the best modern instrumental music of the day, he was already legendary in the Parisian performing arts community by the time Mozart arrived there. A poem by the well-known French dramatist and playwright Pierre-Louis Moline published in the Mercure de France in 1768 attests to this.Footnote 6 The dazzling orchestra Saint-George led was the closest equal to the highly disciplined, precision ensemble Mozart had praised in Mannheim, and its reputation could not have escaped Mozart’s notice once he was residing in the city. The fact that Mozart never once mentions Bologne is curious, and it is especially puzzling since, at this precise point in time, Mozart was vigorously attempting to cultivate employment opportunities in Paris, including seeking out prominent ensembles to perform his works and bring them before ‘live’ audiences that in turn might garner him further recognition, commissions, and paid employment. Pulling these two composer-performers into relationship with one another holds the potentiality of thinking beyond standard, non-inclusive historical offerings.

Second, Bologne was one of the early pioneers and chief exponents of the symphonie concertante, a genre Mozart turned to shortly after leaving Paris and resettling in his native Salzburg. As one of the earliest composers to introduce the symphonie concertante into the Parisian lexicon and to employ this terminology on the title pages of his musical publications,Footnote 7 Bologne was in many respects synonymous with the genre in the mid- to late 1770s, the period directly coinciding with Mozart’s extended stay in the French capital. As a leading composer and executant of violin concertos and symphonies concertantes for two solo violins, he was pushing the boundaries of performance in ‘concertante’ writing. Among his immediate peers, including Giuseppe Cambini (1746–1825), Jean-Baptiste Bréval (1753–1823), Jean-Baptiste Davaux (1742–1822), and François-Joseph Gossec (1734–1829), the most prolific writer of symphonies concertantes was Cambini, who wrote a total of eighty-two, of which about two dozen date from the 1770s.Footnote 8 In contrast to his peers who wrote in a light galant style, Bologne increasingly made more demands on his ‘concertante’ soloists; indeed, during the years coinciding with his zenith at the helm of the Concert des amateurs, he was taking soloistic string writing in the symphonie concertante to new levels. As one of the most highly accomplished players concertizing in this genre during Mozart’s Parisian residency in spring–summer 1778, Bologne was one of the most visible composer-performers, transfixing audiences with his dizzying virtuosic feats on the violin. Between 1775 and 1779 his output included at least eight violin concertos, and at least six, and possibly as many as eight, symphonies concertantes for two solo violins, all published in pairs: the violin concertos op. 5 (1775) and op. 7 (1777), op. 8 and op. 12 (n.d.); and the symphonies concertantes op. 6 (1775), op. 9 (1777), op. 10 (1778), with op. 13 probably also dating from this period.Footnote 9 The solo concertos are in three movements while the majority of the symphonies concertantes are in two.Footnote 10 The increasing level of technical demands Bologne places on the solo violinists in these compositions are designed to command public attention, and position him as one of the foremost creators and producers of this uniquely French genre during the initial decade of its cultivation.

My third reason for wanting to bring Bologne into dialogue with Mozart is to open an avenue for exploring the intersecting worlds they inhabited. While there is no direct evidence that they met one another, making any comment speculative, it is difficult to imagine that Mozart and Saint-George were not aware of one another. Although they moved in separate social spheres, they both inhabited Parisian musical circles, so how likely is it that they did not meet? And what constitutes meeting anyway? Simply being in the same room with one another, being aware of each other’s presence, encountering one another in a concert setting, or hearing one another’s music? What about being formally introduced to one another? Or passing one another in the street, acknowledging one another yet never engaging in conversation? Is it possible that they did meet, and that it was an awkward encounter, making Mozart unwilling or too embarrassed to mention Saint-George in his letters, or not wanting to admit to his father that he had been overlooked or perhaps even rebuffed?Footnote 11 It is difficult to imagine that Mozart was not impacted by Bologne in some way since the latter was such a recognizable phenomenon in Paris at the time. As composer-performers, they were both mutually committed to and deeply invested in offering instrumental performances of the highest calibre. They shared a desire for Parisian audience approval and employed similar methods for attaining it – methods that were not unique to them alone, but which were prominently on display in the rival orchestras they wrote for. Living and labouring together in space and time while inhabiting tangential worlds, their stories are inevitably entangled.

Furthermore, Mozart’s investment in the symphonie concertante after returning to Salzburg suggests that he was attempting to come to terms with events from his Parisian sojourn.Footnote 12 Although he initially turned to church music and symphonic composition back in Salzburg in spring 1779,Footnote 13 he eventually pivoted to symphonie concertante writing – a move that would enable him to process his Parisian experiences. Since Paris was ‘the concertante centre of Europe’, any composition utilizing the symphonie concertante format tacitly acknowledges its French origins, as Barry Brooks reminds us.Footnote 14 So with this in mind, I offer here a reading of Mozart’s highly virtuosic essay in this genre, K.364 for violin and viola, through a Parisian lens as a way of opening a space for further biographical and musical-performative reflection.

In the process of making these arguments, I probe the historical legacy we have inherited and open it up to further scrutiny and reflection. Grounded in history, my methodology is attentive to an affective historical empathy that is rooted in the performing imaginary – an approach that allows for a richer accounting of musical communication and the possibility of offering a corrective to past historical narratives that have overlooked the presence of a racialized musician in Mozart’s Parisian period and its aftermath. Reading history discursively affords the possibility of querying power relations and methods of knowledge formation; indeed, by questioning the logics of overlooking, and imagining alternative historical narratives through the inventiveness of musical performance, we can shape new ways of understanding the past. Examining Mozart’s Parisian musical experiences and his deeply personal and professional losses endured there in relation to his intense period of frustrated ‘concertante’ writing back in Salzburg opens the possibility of repositioning a peripheral figure more centrally into standard historical narratives, enabling us to tell a more diverse, inclusive, and equitable music history. Intentional erasure may not have been the goal of past scholarship; however, refusal to create a space for Saint-George within the histories we tell today could be characterized as such.

Historians regularly engage in speculation and ‘what ifs’ as a way to re-examine and nuance established narrative frames, expand cultural horizons, challenge past perceptions, grapple with the messiness of history, and push frontiers.Footnote 15 By shifting the historical terrain and examining its gaps and fissures, we open up new creative dimensions that allow for the potentiality of a multiplicity of perspectives to co-exist. As R. G. Collingwood reminds us in his influential study The Idea of History, since the thoughts and motivations of those who lived in the past are unknown to us, it is incumbent upon the historian to try to reconstruct the past via ‘historical imagination’, that is, by re-enacting the thought processes of past agents based on the information and evidentiary record that has come down to us.Footnote 16 By imagining the acts of those who lived in the past to discern their thoughts, ‘the historian can rediscover what has been completely forgotten, in the sense that no statement of it has reached him by an unbroken tradition from eyewitnesses. He can even discover what, until he discovered it, no one ever knew to have happened at all.’Footnote 17 The web of ‘imaginative reconstruction’ I engage in here is my attempt at exploring the thought processes behind past actions to expose new lines of enquiry. While the current project might raise questions about the politics behind the recuperative act, ‘recuperative triumphalism’ is not the agenda here.Footnote 18 Rather, starting from the position that race matters, and by acknowledging the presence of historic racism in Western art music studies perpetuated by white scholars, I am compelled to undertake here a gesture of historical recuperation on behalf of a Black musician who has too often been overlooked or marginalized in music history, especially in Mozartian historiography.

Ultimately, I argue that Mozart’s investment in symphonie concertante composition back in Salzburg – a genre closely associated with Bologne – was the personal, self-motivated attempt of a sensitive and vulnerable young man to work through recent events, stressful experiences, and professional as well as personal losses associated with his travels to Mannheim and Paris. It is possible to imagine scenarios in which self-initiated compositional efforts undertaken back home in spring 1779, especially those that cannot be traced to known commissions, including K.364, might be probed through other interpretive means. Although psychobiography may have lost some of its appeal today, I will defend Maynard Solomon’s humanistic legacy, especially if it affords the opportunity to tell a richer story of Mozart’s musical legacy, which in turn allows for the possibility of inserting a long-neglected musical figure into the histories we tell in 2024. I am not arguing that Bologne was the source of Mozart’s disappointments in Paris, or that he was the direct catalyst for fuelling Mozart’s inspiration in subsequent compositions. But I am suggesting that of all the symphonie concertante composers that Mozart may have heard, studied, or encountered in Mannheim and Paris in the later 1770s, Bologne would have stood out precisely because of the pinnacle position he occupied in the Parisian musical hierarchy that Mozart so desperately wanted to penetrate. While Mozart might have wished to infiltrate the Parisian opera scene, just as Bologne sought to do, his experiences in the metropole were primarily limited to the orchestral arena,Footnote 19 a cultural landscape dominated by the fashionable ‘concertante’ idiom that Mozart turned to after returning to Salzburg. Memories of, if not nostalgia for, the lively Parisian musical scene the impressionable young Mozart experienced in 1778 contributed to his musical development back in his native Salzburg during a period of familial reunification and healing. Many musicians, named and unnamed, deserve elevating in this story, and foremost among them is the charismatic virtuoso composer-violinist Joseph Bologne.

As Michel-Rolph Trouillot acknowledges in his formative text Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History (1995), the production of historical narratives is controlled by those in power. Because I hold some of this power, I feel compelled to peel back the one-sided historicity that has prevailed in Mozart scholarship vis-à-vis the composer’s Parisian sojourn to tell a different story, one absent from the historical archive. Emboldened by Naomi André and Denise Von Glahn, who acknowledge in their introductory remarks to a recent colloquy in the Journal of the American Musicological Society entitled ‘Shadow Culture Narratives’ that musicology is starting to change, I seek to be part of this change. ‘Discussions and concerns around music that privileges whiteness at the expense of nonwhite racial, ethnic, and other wide-ranging identities’ are growing and expanding.Footnote 20 With the questioning and querying of ‘who gets to count’ in our standard textbooks and scholarly methodologies coming under greater scrutiny, we are now examining history anew and exploring new initiatives, perspectives, and performative dimensions to create new knowledge networks. Monolithic, normative listening practices long cultivated in our music schools and theory classes are being challenged by those, including BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, People of Colour) colleagues and students, who are seeking to tell a more empathetic, sensitive, emotionally driven – even romanticized – music history in the academy today, and championing a multiplicity of listening perspectives, modalities, and positionalities to enable this.Footnote 21 With so many advocating for change, and actively seeking to foreground other ways of knowing, it is time to probe the entanglement of history and power in Mozart studies. My attempt at putting into practice an ‘engaged musicological’ agenda,Footnote 22 while still rooted in an ‘elite’ European classical music tradition, is nevertheless attentive to expanding the Eurocentric gaze by situating the racially marked Bologne prominently within the Parisian musical culture Mozart inhabited.

Revising History

The first task of an ‘engaged’ agenda is to rid Bologne of the moniker ‘Le Mozart noir’.Footnote 23 Referring to him in terms of the white musical world is to add insult to injury by robbing him of his identity. As Francophone literature professor Julian Ledford notes, Bologne’s unique talents and his lived experiences – not just his skin colour, but complex notions of the social construct of race – are what ought to define him. While Black Mozart may have been a clever marketing tool employed at the turn of the twenty-first century to draw attention to Bologne’s life and music, ‘the term occludes the critical treatment of the Black subject to the point of erasure’.Footnote 24 Rather than defining his mastery of white instruction and his rise to fame within the constructs of the white experience, which is so essentializing, our focus ought to be on Black achievement. A musician with stature and presence in his own day, Bologne’s musical materiality, bequeathed to us through his scores, has the potential to animate musical history, centring him and his remarkable presence in the Parisian musical scene more prominently within discussions of Mozart’s Parisian sojourn and early maturity facilitates a more open and inclusive discussion.

Details of Bologne’s early years are scarce. He was born in Basse-Terre on the island of Guadeloupe on 25 December 1745 to a wealthy French plantation owner, George Bologne (1711–74), and an enslaved African woman of Senegalese descent named Anne (Nanon) Denneveau (c. 1725–95). At age seven, he travelled to France with his father, arriving in the port city of Bordeaux on 12 August 1753, eventually settling in Paris with both his parents in 1756.Footnote 25 The following year George Bologne paid a large sum of money to buy his way into the lowest ranks of the French nobility, and soon thereafter young Joseph’s gentlemanly education commenced. He studied riding, dancing, music, swimming, skating, running, fencing, and swordsmanship. Joseph excelled in the riding school at the Tuileries, and following six years of study at La Boëssière’s Royal Academy of Arms, he proved to be one of the most celebrated fencing challengers of his day.Footnote 26 In 1761, at the age of 16, he had earned the title Le Chevalier de Saint-George upon securing a position as a gendarme du roi (armed man of the king) in the court of Louis XV.Footnote 27 Had the young ‘chevalier’ heard of the musical prodigy who had dazzled ambassadors, aristocrats, and French royalty during the Mozart family visit to Paris and Versailles in 1763–64 – a visit immortalized in the portrait by Louis Carogis de Carmontelle (1717–1806) depicting the child Mozart at the harpsichord making music with his father and sister?Footnote 28

As a titled, affluent man, Bologne had access to the highest echelons of French society. Yet the aristocratic court circles he moved in were not fully accepting of him. Perceived as exotic, he would forever be marked as the illegitimate child of a Black slave, and although a free man, he had to operate under ‘le code noir’ – laws that codified the lives of Blacks in France and the French colonies from 1685 to 1848. In Parisian society he was often called a ‘mulatto’, while others referred to him more charitably as ‘the American’. Supposedly he self-identified as ‘American’ or ‘Creole’, a term that, in the eighteenth century, implied he was born in the New World (i.e., abroad), yet educated in the Old World.Footnote 29 At this time, the term Creole did not yet imply mixed race, hybridization, or transculturation, but it did mark him as ‘Other’ in the 1770s. Although he was far from the only free Black man living in colonial France, he occupied an unusual position – one aided by class yet constrained by race. And as one whose heritage marked him as both colonizer and colonized, he challenges our notion of what inclusion might mean.

As a young, white, European male, Mozart’s concerns were of a different kind. A gifted and ambitious musician undertaking his second trip to Paris in search of fame and fortune, his fears related to his overbearing father, his desire for female companionship, his lack of regular employment, the fear of falling into debt, and his uncertain situation relating to the death of his mother. Compared to Bologne’s elite patronage networks, Mozart’s Parisian circles were of a lower social stratum. Whereas Bologne had access to royalty and aristocrats, Mozart’s acquaintances were the men of letters who served the French aristocracy. Whereas Bologne was wealthy, Mozart’s financial situation was precarious. Culturally challenged in a foreign city, and with few connections, advocates, or acquaintances to turn to, Mozart probably felt increasingly isolated the longer he stayed there. But the prospect of having to return to Salzburg, a place he detested, also lurked in the background. ‘How I hate Salzburg […] Salzburg is no place for my talent!’ penned Mozart in a letter to Abbé Joseph Bullinger dated 7 August 1778.

Paris: Bologne

During Mozart’s second visit to the French capital, Le Chevalier de Saint-George was already a well-known musician, having benefitted from an excellent musical education in both composition and the violin.Footnote 30 Starting out as a violinist in Gossec’s newly established Concert des amateurs in 1769, Saint-George’s talent was readily apparent. Not only did Gossec nurture the prodigious talent of his new protégé, he also helped him gain acceptance in Parisian musical circles and French society more broadly; indeed, Gossec was a leading proponent of legal changes affecting the status of musicians in French society – advocating for ‘a new kind of musician-patron fueled by respect rather than money’, a system that placed musicians on a social plane alongside wealthy connoisseurs and amateurs.Footnote 31 In 1772, Bologne made his solo debut with the Concert des amateurs performing his two violin concertos op. 2, and after Gossec’s departure from the orchestra in 1773, Bologne took over as director, leading the ensemble from 1774 to 1780 (it disbanded the following year). The decline of private orchestras among the aristocrats in the 1770s had encouraged the rise of a flourishing public orchestra scene patronized by the upper classes, of which the Concert des amateurs was a prime example. Existing outside the realm of the court, these ensembles initiated a new approach to musical institution building. In addition to aristocratic sponsorship, the orchestra was also supported by public subscriptions, furthering its ambitions to be an autonomous organization independent from the court.Footnote 32 A progressive ensemble dedicated to promoting new works by current composers in different styles, including French, German, and Italian, the Concert des amateurs was among the best orchestras in Paris during Mozart’s visit in 1778. As the foremost musician in this ensemble, Bologne, now at the apex of his career, was actively performing his virtuosic violin concertos and symphonie concertante repertory usually featuring two solo violins and orchestra.Footnote 33

Not surprisingly, Bologne’s concertizing repertory from this period is marshalled as evidence of his extraordinary skill on the violin. The exuberant solo parts make extensive use of the highest positions on the instrument, and the possibilities afforded by the new Tourte bow. In the words of biographer Gabriel Banet, Bologne’s solo writing is rife ‘with bold, détaché strokes and intricate batteries and bariolage’ (rapid string-crossing)Footnote 34 – the soloist’s left-hand agility and aggressively pumping right arm adding to the visuality of witnessing such virtuosic display and dexterity, especially when sparring with a full orchestra. The opening Allegro maestoso movement of Bologne’s Violin Concerto in D major, op. 3 no. 1 (1774), ably demonstrates this. An excerpt from this concerto performed by Tafelmusik Baroque Orchestra featuring violinist Linda Melsted captures the player’s emotional range and virtuosic skill in negotiating her instrument (Video Example 1)Footnote 35 – skills essential to delivering convincing performances of concertos by Bologne.

Similar virtuosic feats are demanded in Bologne’s Violin Concerto in A major, op. 5 no. 2 (1775), and not just in the opening Allegro moderato movement. The third movement Rondeau begins gracefully enough, but after an extended passage in the minor mode featuring a static drone, further demands are made on the soloist towards the end of the finale. Following the return of the main theme (b. 180), semiquaver passagework for the soloist beginning in bar 212 eventually leads to a stratospheric three-octave scalar ascent (to e3) ending in a dramatic three-octave plunge (bb. 228–32; Example 1); rather than leading to a cadence, however, the rapid string-crossing continues unabated, the sparse accompaniment leaving the soloist particularly exposed at this late stage in the concerto.

Example 1 Joseph Bologne, Violin Concerto in A major, op. 5 no. 2, ed. by Allan Badley (Artaria Editions, 1999), Rondeau third movement, bb. 224–36, especially bb. 228–32.

What if we were to attribute these and other novelties in Bologne’s scores not to hegemonic instructional modes but to Bologne’s unique skillset and identity? His intelligence, concentration, speed, precision, agility, and endurance as an elite athlete here find a new outlet – his right-hand prowess with an épée (like the virtuoso Giuseppe Tartini) readily transferring to his bow technique.Footnote 36 Skills cultivated in the fencing academy, including speed and dexterity, find a new outlet in a feisty, formidable violin technique. As one of the foremost virtuosi of his day, Bologne was on the cutting edge of contemporary violin technique, pushing the limits of what was doable on the instrument. In addition to an aggressive and competitive playing style, might we further attribute the plaintive and sorrowful writing exhibited in several mournful slow movements – for example, the languorous middle movement in D minor from the same op. 3 concerto (Example 2) – to other formative experiences, that is, experiences not shared by other composers, but rather to painful memories of abuse and harm caused to others on his father’s plantation? Did he ever witness physical violence and corporal punishment inflicted by malicious overseers on the Black bodies of the enslaved? Although he left the Caribbean at the age of eight, early exposure to traumatic events may have left an indelible mark on his psyche.

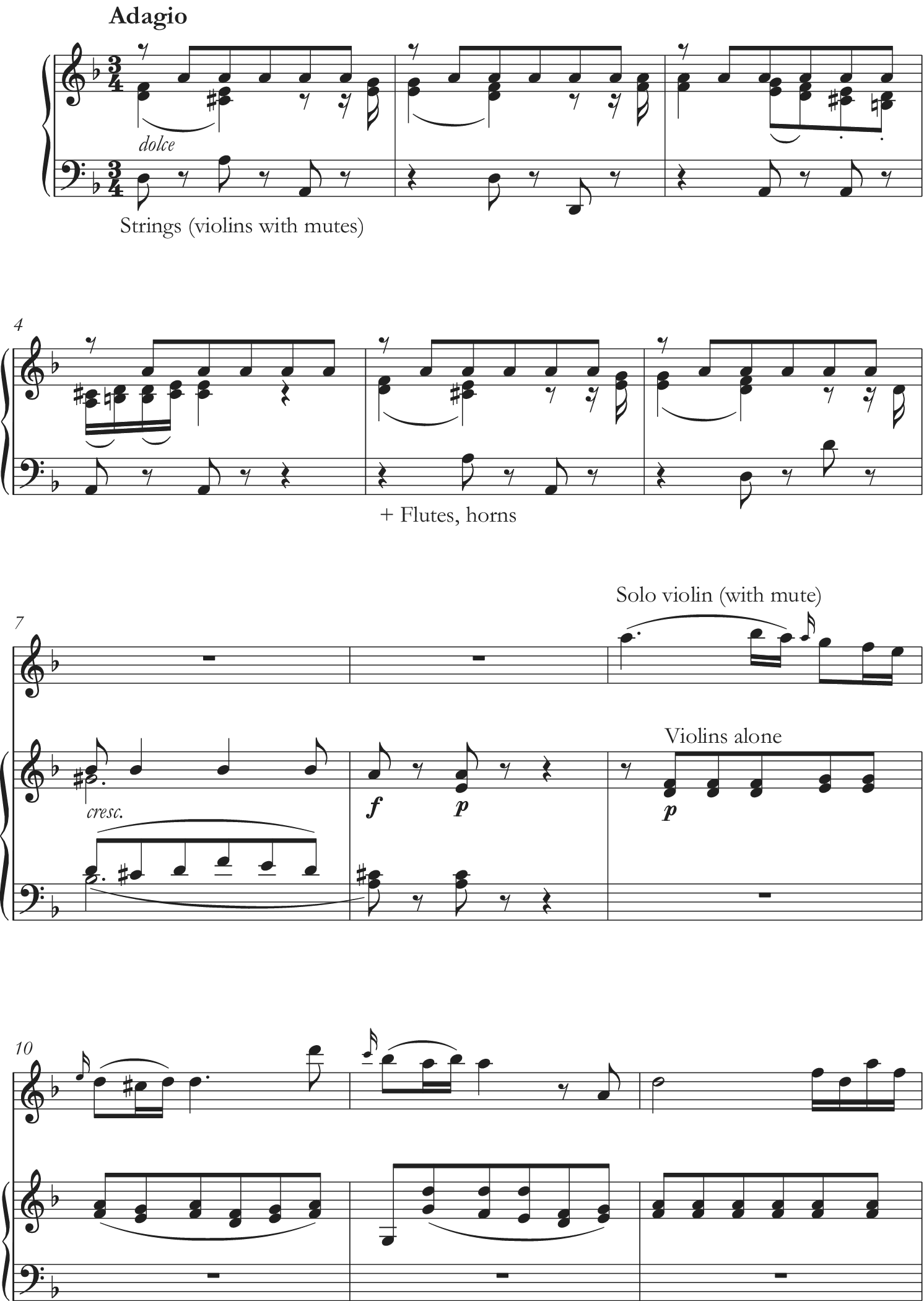

Example 2 Joseph Bologne, Violin Concerto in D Major, op. 3 no. 1, violin-keyboard reduction from the Anthology for Music of the Eighteenth Century, ed. by John Rice (Norton, 2012), 27, Adagio second movement, bb. 1–12. Created from full score, ed. by Allan Badley (Artaria Editions, 2002).

As an adult did Bologne suffer personal anguish while processing his father’s identity as a slave owner and the barbarity of the dehumanizing system he upheld? Was he troubled by the increasingly contentious source of his family’s wealth and accumulation of capital? Did he struggle with his mother’s personal identity as a former slave? When Bologne père returned to Guadeloupe in 1764 to oversee his plantation after the cessation of the Seven Years’ War, Saint-George – and Nanon too – received a sizeable annuity, enabling them both to live together comfortably.Footnote 37 But wealth and social position could not shield Bologne fils from the inequalities and personal indignities he would have experienced during everyday life in the metropole – what we today would refer to as patterns of discrimination, persecution, exclusionary policies, microaggressions, intimidations, gaslighting, and so on, resulting from systemic racism. By the late 1780s, Bologne was on the side of abolitionists who, during the last quarter of the eighteenth-century, were increasingly advocating the end of the Atlantic slave trade. His deep friendship with the young Duke of Orléans, Louis-Philippe, an ardent liberal reformer who subsequently changed his name to Philippe Égalité, led the composer to join the reform movement in support of democracy, equality, and the end of slavery and racial discrimination.

In 1774, having succeeded Gossec as director of the Concert des amateurs, Bologne continued to lead the ensemble from his violin while helping to chart a new path for them.Footnote 38 Already in the late 1760s the orchestra of the Académie Royale de Musique, referred to colloquially as the Opéra, and other ensembles in the French capital were experimenting with the elimination of the batteur de mesure, and instead having the orchestra led by two violinists, one for the firsts and another for the seconds. And by the mid-1770s, the Concert spirituel no longer listed a time-beater and assistant on their roster, replacing them with two violinists who were clearly in charge of leading the ensemble.Footnote 39 Did these violinist co-conductors play a role in popularizing the symphonie concertante featuring two solo string instruments? In other words, did this transitional moment within the social structure of the orchestra, together with the rise of public concert orchestras in the 1770s in general, help set the stage for the cultivation of the symphonie concertante featuring two solo violinists – the preferred medium for Bologne?Footnote 40 Certainly the practices were mutually reinforcing. Bologne composed both symphonies concertantes and solo violin concertos during the precise time these changes in orchestral performance practice were underway. For him, the lighter musical aesthetics and listener ‘approachableness’ associated with the symphonie concertante, a musical medium situated at the intersection of symphony and concerto, could be a site for inhabiting an embodied performative space that accommodated his transnational experiences while also supporting his self-actualization efforts. Sharing the limelight with another talented violinist/soloist was one way for the skilled director to promote acceptance, furthering a sense of dialogue and rapprochement among musicians while also advocating for cultural inclusion. By emphasizing similarities, rather than differences, between peoples and cultures, Bologne could use his music-making as a platform for activism and self-advocacy rooted in equality and inclusion.

Bologne’s Symphonie concertante in C major, op. 6 no. 1, for two solo violins (alternately scored for solo violin and solo violoncello), dating from 1775, provides an interesting developmental perspective. In the opening Allegro moderato, the ‘Principal Violin I’ is demonstrably the dominant player. This instrumentalist is responsible for carrying the majority of the soloistic writing while also displaying the greatest instrumental range and dexterity. Although the entire orchestra contributes to the Parisian sound aesthetic via rapid semiquaver crescendos in the introductory section (e.g., bb. 16–23), the two soloists take on distinctive roles. As expected, they exchange melodic material; however, the lead player initiates and delivers most of the melodic information while the second soloist frequently serves as accompanist (Example 3). The primo player also executes more double and triple stops than the second principal violinist. It is as if Bologne is instructing his counterpart in how to be a ‘concertante’ partner, for the enrichment of all.

Example 3 Joseph Bologne, Symphonie concertante in C major, op. 6 no. 1, ed. by Melanie Braun, The Symphony 1720–1840, editor-in-chief, Barry S. Brook, Series D, Vol. IV, Score 7 (Garland, 1983), first movement, Allegro moderato, bb. 25–31.

Building acceptance on the concert stage, however, did not necessarily translate into broader acceptance. At the same time that Bologne was at the height of his fame – making his mark as a composer and as the leader of the Concert des amateurs – he faced increasing prejudicial treatment as a Black man living in France. As Emil Smidak notes, Bologne’s life in the cosmopolitan Parisian capital was full of ambiguities and ironies; he could direct one of the leading orchestras yet have his proximity to the royal court kept at a distance. He could be lauded on stage yet be the target of oppressive laws aimed at curtailing the activities and personal freedoms of people of African descent living in France. In 1777, Louis XVI banned Afro-diasporic and biracial people from entering the country, meaning that, among other prohibitions, Bologne would have had to carry an identification card to prove he could remain in France. The following year, domestic and colonial racial legislation enacted by royal decree included anti-miscegenation legislation prohibiting interracial sexuality and marriage. It is probably no coincidence that these prohibitions closely followed the professional debacles restricting Bologne’s career at the Opéra, where some members mounted a cabal against him in 1776 to prevent his appointment as musical director of the venerable musical institution.Footnote 41 His daily experiences as a violin virtuoso, ensemble director, and composer differed markedly from other aspects of his life, where he endured racial prejudice and acts of bigotry aimed at degrading and demoralizing him.Footnote 42 Yet despite all these indignities and legal barriers, he seems to have carried the personal burden of knowing that his miraculous life was made possible by the human suffering of countless others.Footnote 43 Continually negotiating his way through an ever-changing musical scene buffeted by increasingly restrictive political and legal decrees founded on racial stigmatization, Bologne appears to have maintained an outward professional demeanour bordering on stoicism. Empowered by his physicality and respected for his swordsmanship, victimhood would not be his fate during the prime of his musical career.

Paris: Mozart

As is well known and documented, Mozart spent a tumultuous six months in Paris, arriving there with his mother on 23 March 1778 and staying to 26 September. In the early months, prior to his mother’s untimely illness and death in early summer, he met with some success. Using contacts provided by his father instead of connecting with his Mannheim colleagues in Paris, Mozart ended up working with the lesser of the two orchestras, the Concert spiritual – not the Concert des amateurs overseen by Le Chevalier de Saint-George. Leopold had reiterated the names of both orchestras in a letter to his son dated 6 April, noting that they were the two most important musical institutions in Paris, and that Wolfgang should approach both ensembles for possible commissions.Footnote 44 Yet as Neal Zaslaw observes:

By common report, the best Parisian orchestra in 1778 was not the well-established Concert spirituel, but rather that of the newer Concert des amateurs […] In order to have the best possible way of presenting his symphonies to the Parisian public, therefore, Mozart should logically have approached the organizers of the Concerts des amateurs. (The musical director in 1778 was the violinist and composer Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges.)Footnote 45

But this appears not to have happened; if Mozart did contact the ‘best Parisian orchestra’ in 1778, led by the enterprising Le Chevalier de Saint-George, it did not result in a commission. Instead, Mozart composed the Symphony in D major, No. 31, nicknamed the ‘Paris’ (K.297/300a) for the Concert spiritual. And it is clear from this composition and reports relayed to his father that he tried to interject some youthful energy and pizzazz into the older, more established ensemble.

Mozart’s ‘Paris’ symphony, a three-movement work, had its premiere on 18 June 1778, Corpus Christi Day (the Thursday following Trinity Sunday), in the Palais des Tuileries. Commissioned by Joseph Legros, who in 1777 assumed financial oversight of the Concert spirituel after leaving his position as the leading haute-contre at the Opéra (where he premiered the role of Orphée in the version Gluck prepared for Paris in 1774), this symphony was Mozart’s entrée into contemporary Parisian musical culture. Baron von Grimm, who the Mozart family met on their European grand tour in the mid-1760s, was likely responsible for facilitating this commission from Legros. As director of Le Concert spiritual, Legros was instrumental in continuing the modernizing traditions of his predecessor Pierre Gaviniès, and ‘within a few years made the Haydn-Mozart symphonic idiom a staple of Paris concert life’.Footnote 46

As Mozart writes to his father, the triumphant first performance of this symphony was preceded by a disastrous rehearsal the day before: ‘You can’t imagine how they bungled and scratched their way through the Sinfonie – twice in a row.’Footnote 47 Mozart built in several crowd-pleasing special effects, including grand unison passages in the Allegro movements where all the instruments play together. An arresting premier coup d’archet launches the symphony on its boisterous journey, with unison statements, gradual crescendos leading to brilliant forte passages, and rapid string tremolos creating an electrifying soundscape and overwhelming sense of excitement (Example 4). He and Leopold Mozart agreed on what constituted Parisian taste: ‘To judge by Stamitz symphonies that have been engraved in Paris, the Parisians must be fond of noisy symphonies. All is noise, the remainder a mishmash, with here and there a good idea awkwardly introduced in the wrong place.’Footnote 48 Indeed, the ‘sight’ of nearly sixty musicians all working together in tandem to produce a driving, direct sound devoid of inner complication or intellectual demands wildly impressed Parisian audiences. And here Mozart calculated well, by giving them a thrilling opening Allegro that would appeal to their desire for immediacy of effect and comprehension, to which they readily responded with vocal responses and applause, even mid movement.Footnote 49

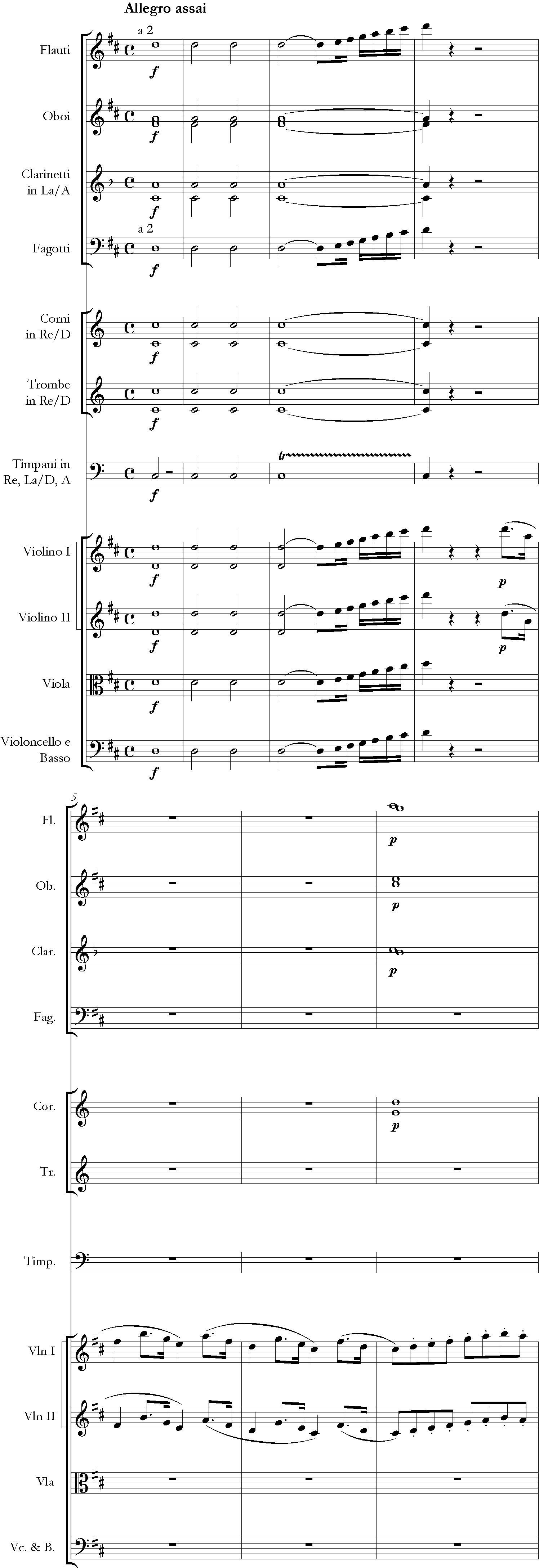

Example 4 Opening of Mozart’s Symphony No. 31 in D major, ‘Paris’, K.297/300a, bb. 1–7. (Neue Mozart-Ausgabe, series 4, workgroup 11, vol. 5, Sinfonien, ed. by Helmut Becker (Bärenreiter, 1957)). NMA Online (<https://dme.mozarteum.at/nma/>), published by the Mozarteum Foundation Salzburg in collaboration with the Packard Humanities Institute, 2006ff. Reproduced with kind permission of the Mozarteum Foundation.

If Mozart had connected with that other Parisian ensemble and cultivated a deep and meaningful relationship with the famed director of the Concert des amateurs, Joseph Bologne, our historical accounts of the period would be very different.Footnote 50 It is possible that Mozart attended performances of the Concert des amateurs and witnessed first-hand Bologne’s violin virtuosity and commanding presence with both his orchestra and audience alike, gaining an even deeper knowledge of Parisian musical taste as well as Bologne’s violin virtuosity. But one can only wonder how Mozart’s Paris sojourn might have played out had he connected with the charismatic Bologne beyond a possible casual encounter or meeting. Might a Black man born in the Caribbean have jolted Mozart into contemplating the horrors of the Middle Passage slave trade, or opened his eyes to the prejudicial treatment racial minorities were increasingly being subjected to within a supposedly ‘enlightened’ French society? Might ‘the American’ have introduced Mozart to a more cosmopolitan and multicultural city, one infused with revolutionary ideas fostered by events unfolding in the thirteen colonies across the Atlantic? With the arrival of Benjamin Franklin in Paris as America’s ambassador in 1776, democratic beliefs were taking root in France. Did some of Mozart’s own liberal ideas and desire for freedom from domination start percolating in this liberating environment? He would not necessarily have needed to follow the reception of Niccolò Piccinni’s opera buffa I napoletani in America (1768) and the intermezzo Gli italiani in America (1769), both on librettos by Francesco Cerlone, to be aware that the far-off place called America was known as the land of liberty, especially for white males like him. If Mozart had connected in a meaningful way with this Italian opera colleague who had recently arrived in Paris – indeed, they might well have connected at the performance of Piccinni’s Le finte gemelli where Mozart’s ballet music for Les petits riens premiered on 11 June 1778Footnote 51 – it is possible that, with further introductions via Piccinni, Mozart would have received other commissions.

An encounter with Bologne could have triggered another rivalry, a querelle or manufactured competition between composers pitting one orchestra and/or performer against another. As with the Querelle des bouffons of the early 1750s, it was not difficult to foment an opera rivalry between warring factions of the musical elite associated with the court against those whose aspirations were aligned with the rising bourgeoise classes. Social changes underway in France readily divided the Parisian public into the two parties, and at this very moment a contest was brewing between operatic partisans of the Gluckistes versus the Piccinnistes (1776–77). Pulled into an unwanted dispute by political players and situations beyond their control, Gluck, the classical dramatist whose French-language setting of Orphée et Eurydice (1774), was pitted against the Italian Piccinni, whose operatic musical language was rooted in naturalness, simplicity, and sentimentalism. Recognizing the merits of each, neither composer was interested in pursuing this manufactured quarrel, so it soon dissipated.Footnote 52 Similar class dynamics were in play between Bologne and Mozart, but a rivalry never materialized. Besides, events in Mozart’s personal life were conspiring against him, and opportunities to distinguish himself as a performer of keyboard concertos were not readily available, derailing his efforts to establish a viable career there (unlike his concertizing possibilities at self-organized Accademien in Vienna in the 1780s).

At the time of the ‘Paris’ symphony’s premiere, Mozart’s mother was already ill, and a few weeks later she passed away, leaving the 22-year-old Mozart all alone in Paris.Footnote 53 After Anna Maria Mozart’s death on 3 July 1778, Wolfgang gave up his small apartment and sought refuge with his father’s old friend, Baron von Grimm. At the invitation of the Baron’s ‘intimate friend’ Madame Louise d’Épinay, Mozart stayed in a room within her quarters rather than with ‘the mean-spirited Grimm’, as he explained in a letter to his father.Footnote 54 Mourning the loss of his mother, low in cash, and grappling to find his footing, Mozart here received lodging and free meals. And this is where it gets very interesting, since at the very same time Saint-George was residing in an adjacent house owned by Madame de Montesson (1738–1806), wife of Louis-Philippe, the Duke of Orléans (1725–85). As the widow of the lieutenant-general of the king’s army who died in 1759, Madame de Montesson was independently wealthy, and as a prominent patron of the arts, she employed Bologne to oversee her private theatre after he was summarily passed over for a position at the Opéra.

Prior to 1770, the Duke of Orléans’s apartments had been in the capacious Palais Royal in the centre of Paris, which is where the baron also lived and worked as the duke’s personal secretary. In 1770, however, both households moved to new quarters in the newly fashionable and desirable residential neighbourhood of Chaussée d’Antin, located northwest of the city centre just outside the city walls (now the 9th arrondissement).Footnote 55 Here, where the elevation was higher and the air fresher, Saint-George and Mozart lived in adjacent mansions for several weeks in the summer of 1778: the Duke of Orléans and Madame de Montesson lived at numbers 1 and 3 rue Chaussée d’Antin, respectively, and Baron Grimm and Madame d’Épinay lived at number 5. Located on comparatively small, diminutive lots, many of the houses in this area were designed for wealthy independent women, their intimate plans expressing the characters of their female clients. Madame de Montesson’s mansion, for instance, was luxurious but not grand; her one-storey home, which contained public reception rooms and private apartments, resembled an urban villa with a grand entrance and an English-style garden.Footnote 56 Given the proximity of their residences, Mozart and Bologne must have seen one another in the rue de Chaussée d’Antin. Generally uncomfortable in aristocratic surroundings, however, the younger, socially insecure musician was unlikely to have had a meaningful encounter with a titled man living nearby.Footnote 57 Nor do their female benefactors, Madame de Montesson and Madame d’Épinay, appear to have orchestrated a salon or social engagement to introduce the two musicians. The most natural milieu for Bologne and Mozart to have engaged with one another would have been the immersive environment of the Parisian concert hall, a place where both were in their element, and where Bologne held a commanding presence.

Mozart’s musical experiences in the metropole lingered with him long after he left Paris. The following summer back in Salzburg, approximately a year after his mother’s death, Mozart turned once more to symphonie concertante composition. Even though ‘Wolfgang’s resistance to the French, the actual people, their language, their singing, and their musical taste was deep-rooted,’Footnote 58 he continued to be haunted by encounters, observations, and tragic events from this formative journey. Once settled back in Salzburg, of his own volition Mozart turned to writing French-style symphonie concertante on multiple occasions. His foremost composition utilizing ‘concertante’ principles is his widely acclaimed symphonie concertante for solo violin and viola.Footnote 59

Paris Meets Salzburg

Mozart’s Sinfonie concertante for violin and viola in E♭ major, K.364 (320d), dates from Salzburg 1779, and was most likely completed that summer.Footnote 60 Many works in this genre are scored for two violins, while those for violin and viola are much less common.Footnote 61 No information has come down to us as to why, or for whom, this particular piece was written. (The same applies to the two-keyboard concerto K.365/316a.) Heartz suggests that, if it was completed in the summer of 1779, then a possible performance venue would have been the court of the Mirabell Palace or Gardens, with the Neapolitan violinist Antonio Brunetti perhaps playing the solo violin and Mozart the viola part.Footnote 62 Stanley Sadie also speculates that Brunetti and Mozart may have played the two solo parts, since Mozart ‘is known to have played the viola, at least in his later years’.Footnote 63 Both Heartz and Sadie seem to believe that the piece was written for the Salzburg court orchestra, overseen by the autocratic Archbishop Hieronymus von Colloredo, whom Mozart despised.

As Cliff Eisen reminds us, however, ‘it would be a mistake to think that Salzburg had but a single orchestra’, or that ‘all the works Mozart wrote in Salzburg were composed for performance at court’. As he explains, ‘the archdiocese supported several private orchestras, and parish churches and monasteries throughout Salzburg province also maintained independent musical establishments’ of different ensemble size and make-up, all of which performed Mozart’s music.Footnote 64 The city also had many professional musicians, who could augment the court, cathedral, and university orchestras as well as other ensembles. Since few if any of Mozart’s orchestral works written between 1779 and 1780 were played at court (a time when Colloredo was finalizing his plans for eliminating purely orchestral music during church services), Eisen concludes that ‘some of Mozart’s finest orchestral and chamber music was written for family friends’, with numerous documents attesting to ‘the private performance of Mozart’s chamber and orchestral works’.Footnote 65

Most likely Mozart had a different ensemble and venue in mind for his three-movement solo violin and viola symphonie concertante aside from the Salzburg court. Indeed, it is difficult to imagine that he conceived this very special piece for an orchestra he held in such low esteem, one he described as ‘slovenly’ and ‘run-down’.Footnote 66 Moreover, he had little regard for the lead violinist, Brunetti, describing him as ‘rude and filthy […] a disgrace to his master, to himself, and to the whole orchestra’.Footnote 67 Why would he want to trust the execution of such exquisite writing for the two soloists to a musician and orchestra he reviled? If Mozart imagined himself playing the viola part alongside the other soloist, then Brunetti and the court orchestra would have been a non-starter.Footnote 68

Of the two multi-solo concertos Mozart wrote in Salzburg in 1779, only the one for solo violin and viola is complete as a self-standing symphonie concertante.Footnote 69 Incomplete attempts in the genre include the concerto for violin and keyboard begun in Mannheim on Mozart’s homeward journey in November 1778,Footnote 70 and the opening Allegro for solo violin, viola, and violoncello in A major (K.320e) that survives only in a 134-bar fragment.Footnote 71 The Serenade in D major, nicknamed ‘Post Horn’ (K.320; dated 3 April 1779) contains two concertante movements for wind quartet (pairs of flutes and oboes) within a seven-movement work; however, the ‘concertante’ Andante and Rondeau movements wedged between two Menuetto movements are Italianate in style, and devoid of virtuosic display.Footnote 72 The ‘Concertone’ in C major for two solo violins and orchestra (K.190) composed in 1774 might have been called a symphonie concertante had it been written in Paris or Mannheim; however, it too is far less grand and virtuosic than works in this genre by Bologne. This early Concertone resembles more the three symphonies concertantes Johann Christian Bach published in Paris between 1772 and 1775 – elegant entertainment music in galant style composed for easy listening, not virtuosic display.Footnote 73 Of the two symphonies concertantes Mozart composed in Paris in 1778, the ‘Concertante’ in C major for flute and harp was for dilettante flautist Adrien-Louis de Bonnières, the Count (later Duke) de Guînes, and his daughter Marie-Louise-Philippine (Concertante a La Harpe e Flauto, K.299),Footnote 74 and the other for solo wind instruments composed in Paris was never performed.Footnote 75 In addition to the symphonie concertante for solo violin and viola, only the fragmentary A major concerto abandoned in 1779 holds out the possibility that Mozart may have imagined himself being one of the soloists. In summary, Mozart’s Sinfonie concertante for solo violin and viola in E♭ major (K.364) is unique in many ways, and could benefit from additional probing about its possible origins and performance ideals.

Many have speculated that Mozart wrote this symphonie concertante for solo violin and viola to introduce Salzburg to a format of public music-making that was all the rage in Paris.Footnote 76 By utilizing high Parisian musical fashion to convey a musical story back in Salzburg, Mozart could reflect on his time in the French capital while relaying another message, not only introducing his local audience to this special format of ‘concertante’ performance but also personalizing the message for them. By extension, in selecting the symphonie concertante medium as his vehicle, it could also be argued that Mozart was alluding to some of the composer-violinists who were the chief exponents of this music that was ‘all the rage in Paris’ – chief among them Bologne, Cambini, Davaux, and Gossec. As head of the Concert des amateurs with a formidable technique to match his position, and as a Black man with an aristocratic title and pedigree, Le Chevalier de Saint-George stood out among his peers. He was centre stage in the Parisian musical milieu, creating and delivering a sensational form of musical performance beloved by the French musical public.

Bologne’s two symphonies concertantes for two solo violins, op. 9 nos 1 and 2, published in 1777 at the height of his career, show subsequent developments in concerto writing for duelling violinists that are apparent in Mozart’s sinfonie. Appearing the year prior to Mozart’s arrival in the French capital, the op. 9 symphonies concertantes feature two solo string virtuosi occupying equal footing within the musical soundscape, their commensurate skills simultaneously on display. Both violin soloists exude confidence, in contrast to their counterparts in the op. 6 symphonies concertantes composed two years earlier (as discussed in Example 3). For instance, in op. 9 no. 1 in C major, during the initial entrance of the soloists, the first violin (Bologne?) carries the main melody (b. 53), only to be superseded by the second violinist that takes the lead in the next entry, even playing in a higher register than the first violin (b. 69; see Examples 5a and 5b). They trade off in this manner throughout, assuming co-equal roles – either instrumentalist able to implement a passage that the other then imitates or echoes. Only when the soloists play in thirds or sixths does the first violinist consistently play the upper part. With greater equanimity between the virtuosic soloists now apparent in Bologne’s mature ‘concertante’ writing, it is clear that he has no difficulty writing for, and sharing the stage with, other gifted members of the orchestra. As Allan Badley observes, ‘the solo writing in the [op. 9] symphonies concertantes is challenging and shows little evidence of Saint-Georges’ concern to accommodate players less skilled than himself’.Footnote 77 For instance, a four-bar, quasi cadenza-like passage near the end of the first movement (bb. 215–18) demands rapid shifting of the primo violinist (a3 down to g1), and is the most taxing passage in the opening movement of op. 9 no. 1. In comparison, the passages in Example 5 are comparatively easy to execute, requiring no awkward left-hand shifts.Footnote 78 Here, Bologne places himself on equal terms with another member of his ensemble, demonstrating a capacity for competitiveness and generosity towards other musicians. Moreover, his duelling display of talent and virtuosity circulated broadly through publication and performance, enabling other ensembles to replicate the ideals of soloistic equivalency.

Example 5a Joseph Bologne, Symphonie concertante in C major, op. 9 no. 1, ed. by Allan Badley (Artaria Editions, 2020), first movement, bb. 50–60.

Example 5b Bologne, Op. 9 no. 1, bb. 68–76.

The French-inspired symphonie concertante featuring two equal string protagonists was a highly unusual genre for Mozart to bring to Salzburg, especially as there are simply no works entitled sinfonie concertante (symphonie concertante) by other composers listed among the orchestral music written for Salzburg in the 1770s.Footnote 79 In other words, K.364 is unique not only in Mozart’s oeuvre, but also in the context of orchestral music-making in Salzburg. Indebted to French style and taste, it is an anomaly, and it is this uniqueness that makes me think this piece, one of Mozart’s most mature to date, is of a more personal nature, not really designed for wide public consumption at all, but rather for a more intimate setting of family friends and acquaintances. Here, Mozart takes a public French genre and subverts its ‘public’ image by crafting instead a composition that is imbued with private feelings and memories of his Parisian sojourn. With the loss within his immediate family uppermost in his mind, Mozart writes a symphonie concertante replete with Parisian virtuosic flair, but one that is also calculated to fulfil individual needs and expectations in his hometown of Salzburg. Experiences and feelings that were difficult to put into words were poured into this special Parisian-inspired piece.

Mozart’s Symphonie (Sinfonie) Concertante in E♭ Major for Solo Violin and Solo Viola, K.364

The K.364 shares many similarities with the composer’s ‘Paris’ Symphony from the preceding year. Scored for solo violin and solo viola plus two oboes, two horns and strings, including violas I and II, it features scordatura tuning in the solo viola, whereby the strings on the instrument are tuned up a semitone, permitting the violist to play in D major but sound in E♭ (Example 6). The higher tuning makes the tone of the instrument brighter, more in line with the violin, while also increasing the resonance of the instrument (with open strings in D major). It also enables the player to get around the instrument more readily.

Example 6 Opening of Mozart’s Sinfonie concertante in E♭ major for solo violin and viola, K.364, bb. 1–4. (Neue Mozart-Ausgabe, series 5, workgroup 14, vol. 2, ed. by Christoph-Hellmut Mahling (Bärenreiter, 1975)). Reproduced with kind permission of the Mozarteum Foundation.

The Sinfonia concertante opens in a similar fashion to the ‘Paris’ symphony, with accented dotted-rhythm ‘hammerstroke’ chords serving to ‘kill the noise’. Although a common-enough device in galant music of the period (e.g., Mozart’s Symphony in D major from 1772, K.133, opens with triple tutti chords that harken back to J. C. Bach’s keyboard sonatas), its use here is associated with the typical Parisian (and Mannheim) music-making arsenal. The long crescendo that gets underway shortly thereafter further recalls the crowd-pleasing passages Mozart built into his ‘Paris’ symphony. A Mannheim-style crescendo in the orchestral tutti section, replete with trills and tremolos, begins its slow ascent (starting in b. 46, Example 7). This well-paced Rossini-like passage avant la lettre is calculated to build a sense of excitement and anticipation over a span of approximately fifteen seconds, heightening listener expectations.Footnote 80

Example 7 Sinfonie concertante in E♭ major for solo violin and viola, K.364, movement one, bb. 44–49 (crescendo passage builds from b. 46 to b. 64). NMA Online (<https://dme.mozarteum.at/nma/>), published by the Mozarteum Foundation Salzburg in collaboration with the Packard Humanities Institute, 2006ff. Reproduced with kind permission of the Mozarteum Foundation.

In all three movements the two soloists interact equally, with a superabundance of thematic material exchanged and echoed throughout. As Konrad Küster observes, ‘the motivic separation of solo and tutti […] allowed Mozart to take a fresh look at the construction of the solo sections’; indeed, ‘the fact that there is always more than one soloist in a symphonie concertante makes it possible to give less prominence to the soloist-orchestra relationship and more to the relationship of the soloists to each other’.Footnote 81 And this is precisely the point I want to focus on. Equality among the two players was a feature of Parisian symphonies concertantes of the later 1770s, as shown in the Bologne example (Example 5a and 5b), and it is also something Mozart exploits to great effect in K.364, especially in the lengthy cadenzas.

Many commentators have speculated that Mozart may have been paying tribute to his mother in this piece, especially in the sorrowful C minor middle movement, and its moments of unsettled harmonic wrestling. Her death in Paris at the age of fifty-seven was a real family tragedy, one that was bound to have long-term repercussions.Footnote 82 To honour her memory with a heartfelt musical tribute would have been a natural response, especially one in which intertwining voices are continually responding to and supporting one another. The affective range of the dialogue between violin and viola is extremely eloquent, with each instrumentalist inciting something richer and more passionate from the other. Others have speculated that Mozart composed the violin part for himself, while Robert Gutman suggests that Mozart may have intended the piece ‘for Leopold and himself’, with Wolfgang playing the viola, an instrument for which ‘he held no resentment (unlike the violin)’.Footnote 83 In a subsequent section, I pick up on this point, but in the meantime, what if we were to imagine Joseph Bologne as the recipient of the solo violin part in K.364?

Personae and Sociability

Individually and together, scholar-performers Tom Beghin and Elisabeth Le Guin continually emphasize the importance of embodiment, gesture, physicality, sociability, and historical imagination in their recreative musical practices. Reflecting on their joint performance project at the Orpheus Institute in 2016, in which they think deeply and write ‘thickly’ about a multiplicity of performance modalities engaged in when encountering Haydn’s string quartets and keyboard trios, they advocate returning ‘again and again to the concrete and the corporeal’, or imaging ‘performing and/or listening personae’ when interpreting music.Footnote 84 Moving beyond a traditional understanding of historical musical performance rooted in an over-reliance on score analysis and an attentiveness to sound only, their laboratory of historically based experimentation foregrounds sociability through the imaginative mode of ‘historical impersonation’. Encapsulating W. Dean Sutcliffe’s notion of ‘the shapes of sociability’ in articulating the various ways musicians interact with one another (especially when playing string quartets),Footnote 85 their experimentation with musical impersonation when making music among friends and colleagues suggests how imagining different scenarios for realizing musical scores promotes new critical engagement with these scripts.

Building on this idea and extrapolating to the symphonie concertante context, it is possible to extend our understanding of sociability to include the kinds of role-playing and turn-taking evidenced in the duets, trios, and quartets of soloists in the symphonie concertante. By rethinking the relationship of these individual solo instruments to one another, we might understand ‘concertante’ soloists as comprising a similar kind of sociality, that is, distinct characters or personae making music together. The major difference is context: the soloists just happen to be surrounded by a much larger community of orchestral players with whom they also interact and take turns. Nevertheless, their soloistic give-and-take, commanding physicality, social interplay, and communicative gesturing aligns with Edward Klorman’s conceptualization of multiple agency, whereby multiple personae engaging in discourse ‘are understood to act autonomously and to possess the consciousness and volition necessary to determine their own statements and action’.Footnote 86 Klorman’s term ‘captures the notion that a chamber music score is, above all, something to be played, an encoded musical exchange in which each player assumes an individual character’.Footnote 87 And a similar agency applies to the musical interactions and social exchanges engaged in by soloists in a symphonie concertante – whether it be two solo violins in a symphonie concertante by Bologne, or violin and viola soloists in Mozart’s sinfonie concertante.

Now what if Mozart had imagined a musical duel between the virtuosic Bologne, his imaginary Parisian protagonist, in his French-inflected sinfonie concertante? Or what if, in the spirit of Beghin and Le Guin, we were to imagine these two protagonists performing K.364 together? Even though the two composer-performers appear never to have performed with one another, it does not mean that we cannot conjure up such an experiment, or that Mozart could not imagine himself playing alongside the virtuosic violinist Bologne in order to tell a different version of events than the ones that actually unfolded. Since Bologne was among the most accomplished violinists in Paris during Mozart’s visit, one could well imagine the younger composer relishing the thought of showing off his talents as composer and instrumentalist with such a famous musical interlocutor. With Bologne on violin and Mozart on the viola, the young composer could introduce the renowned violinist to yet another manifestation of the ‘concertante’ duo, one that paired the violin with a viola using altered tuning to increase the instrument’s brilliance. As a stage performer and consummate musician, Bologne would have readily appreciated the change in sound quality and timbral effect created by this manoeuvre, and the potential for sonic reverberation in a resonant concertizing space. He also would have immediately recognized the formidable talent of his soloistic partner.

Upon their joint entry in the opening movement of K.364, the two soloists double one another at the octave, while in the second statement they echo one another, differentiating themselves. Two string personae emerge, seamlessly working separately and together in harmony to create a kind of conversational-style dialogue – one taking the lead, then retreating into an accompanying role while the other assumes authority. During their mutual engagement and partnership in this dialogic give-and-take, no player dominates the other. The two are continually on an equal footing, demonstrating the shared democratic ideals embedded within the score. A fantasy? Perhaps. But one that unites the ‘concertante’ tradition with innovations in partnership and communal authorship, the very kinds of distinguishing features that would have got Mozart noticed in Paris had this imagined scenario come to pass.

More likely is the scenario suggested by Gutman, where Leopold – accomplished string instructor extraordinaire – is the imagined recipient of the violin solo. With Leopold in this role, might we understand the Sinfonie concertante in E♭ major as a kind of therapeutic peace offering from son to father? If Leopold and Wolfgang are the intended solo recipients – the characters or protagonists interacting in the musical-theatrical drama as it were – we might imagine the sinfonie as a kind of rapprochement between father and son, in memory of a beloved wife and mother. Whatever words were – or were not – exchanged between Wolfgang and Leopold upon their reunification in Salzburg, mere words could never express the heartfelt emotions and sorrows that are so palpable in this piece. In recognition of their joint sorrow, the musical epitaph etched in this symphonie concertante prompts the soloists to sympathize with one another rhetorically through their music-making, performing an act of mutual reconciliation, reciprocity, and healing. There is a kind of familial relationship traced between the intertwining solo violin and viola lines, a mutual interconnection that goes beyond that of the preceding imaginary Mozart/Bologne pairing. In other words, democracy, exchange, and independence are not the primary motivators here; rather, the collaborative, affective interconnectivity articulated here is more intimate and deeply felt, suggesting that the imagined personae are Leopold and Wolfgang. They are the dual interlocutors animating and re-enacting their shared loss – their intertwining cadenzas, in particular, providing the two players with sufficient agency to ‘work through’ their feelings and emotions.

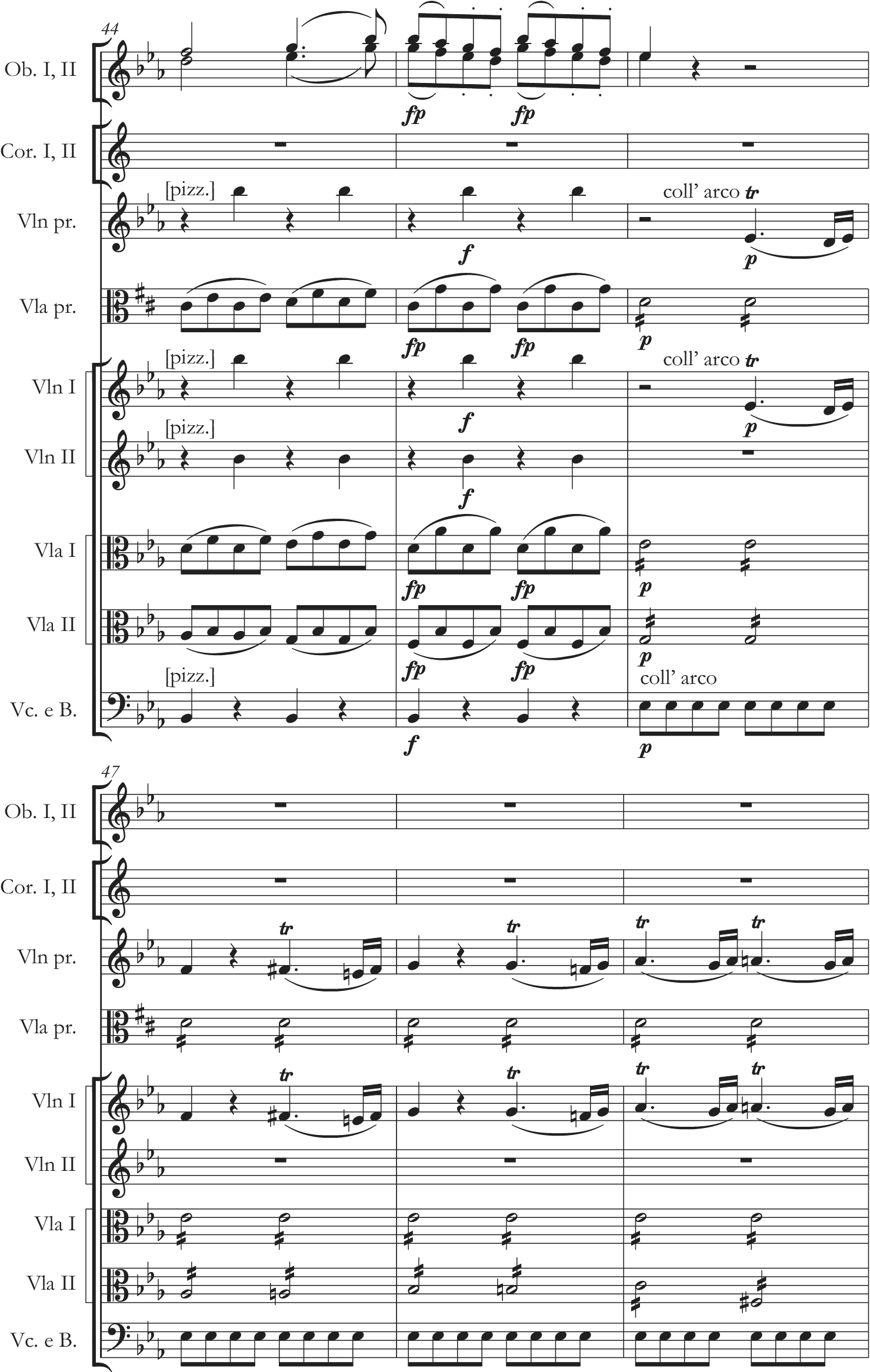

Extemporaneous cadenzas were the norm in solo concertos of this period. Bologne would have improvised the cadenzas in his violin concertos (just as Linda Melsted does in her performance of the first two movements of Violin Concerto in D major, op. 3 no. 1, in Video Example 1). The first movement of the Symphonie concertante in A major for two violin soloists and a single solo viola, op. 10 no. 2 (1779) is an interesting case, since period performance practice would seem to indicate that some form of improvisation occurs at the pause in bar 89 (Example 8). While it is unlikely that improvised cadenzas for two players were a feature of Bologne’s multi-solo ‘concertante’ works, there is a possibility that two players could have rehearsed a cadenza to insert here, implying ‘multiple agency’. More likely only the primo violinist improvised a cadenza at the pause in Example 8 – signalling the tutti return with the lead-in to bar 90.

Example 8 Joseph Bologne, Symphonie concertante in A major for two solo violins and viola, op. 10 no. 2, ed. by Melanie Braun, The Symphony 1720–1840, editor-in-chief, Barry S. Brook, Series D, vol. IV, score 8 (Garland, 1983), first movement, Allegro, bb. 87–91.

Written-out cadenzas, while rare in symphonies concertantes, do appear on occasion. An interesting example is found in the Symphonie concertante in D major for solo oboe and solo bassoon by Carl Philipp Stamitz dating from 1782 to 1784.Footnote 88 A total of ten bars in length, the notated cadenza offers a helpful instructive template for how the soloists might engage in virtuosic display. Did dual ‘concertante’ wind players require more assistance than string players when crafting cadenzas? Or did Stamitz, who worked in Mannheim, Paris, and London during this time, want to ensure that soloists in different geographical locations would understand performance practices (and listener expectations) in other centres? Or was he showing wind instrumentalists what was expected of them, or what he himself expected of soloists? Questions abound, for which multiple answers are possible within a culture of experimentation.

In Mozart’s K.364, the cadenzas for solo violin and solo viola occurring in the first two movements are written out fully, leaving nothing to chance.Footnote 89 The closely intertwined musical interplay between the two performers in these ‘cadenze a due’ demonstrate their mutual investment in listening to and ‘hearing’ one another and responding accordingly. Although this might be understood as the norm for ‘concertante’ duo players, the special or ‘marked’ quality of their particular musical interactions in these cadenzas might also be interpreted as foregrounding acts of remembering, revisiting, untangling, and replaying past events – a mode of musical interaction designed to promote healing and reconciliation between father and son. Together the participants perform a communal act of listening, empathizing, and supporting one another on their familial journey towards recovery. So penetrating and interdependent are their interactions that it is as if the rhetorical gesturing exchanged between the two imagined protagonists – Wolfgang and Leopold – stands in mnemonically for the memories of their mutually lost love. A lonely widower and his bereft son interleave their shared understanding of loss and forgiveness, their performance becoming a collective act of mourning to bring about emotional healing and restore cohesion to the close-knit family constellation, a unit that had been cruelly ripped asunder and in desperate need of reunification (Examples 9a and 9b). Suggesting how specific historical figures may have experienced their own music provides a mode of historical access normally precluded in traditional histories.

Example 9a First movement cadenza for solo violin and viola in Mozart’s Sinfonie concertante in E♭ major, K.364.

Example 9b Second movement cadenza for solo violin and viola in Mozart’s Sinfonie concertante in E♭ major, K.364.

By couching this healing process within the symphonie concertante, Mozart not only recalls Paris, the place where the tragedy occurred, but also builds on the ‘concertante’ principle by creating an opportunity for the two mourning men closest to Anna Maria to put their feelings ‘out there’ for one another to hear. Further enlisted in the recovery process are all the other instrumentalists in the ensemble performing the symphonie concertante alongside them. Fellow orchestral players, musicians from their close-knit circle of friends and acquaintances in Salzburg, listen to and bear witness to the family loss, becoming a supportive and compassionate community to envelop the family and nurture healing from within. In capitalizing on performance as a historical mode of knowing, we are able to access an immersive experience of historical subjectivity.

Partimento Partners

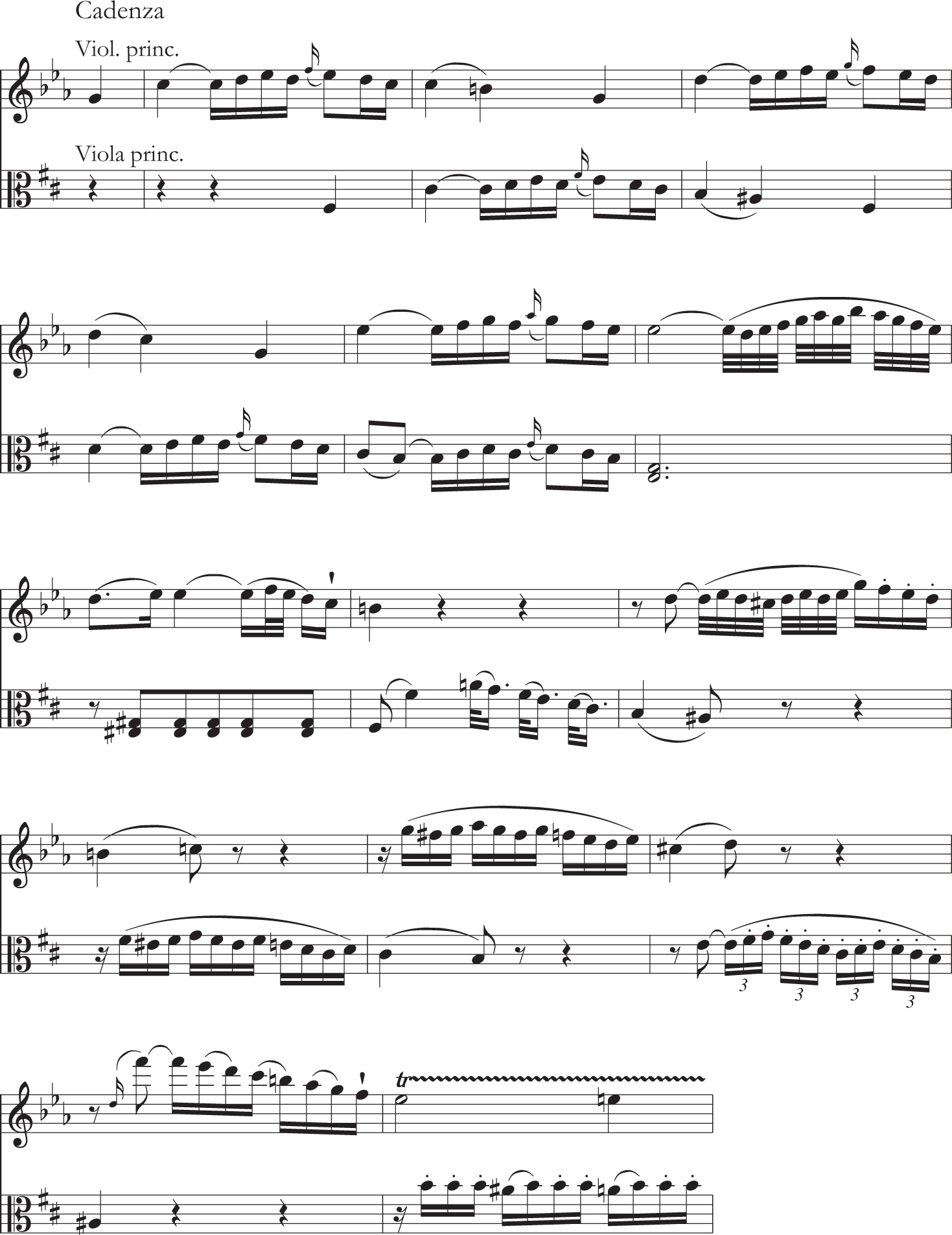

Compared with the early two movements, the Presto finale of K.364 conveys an entirely different ethos and sensibility. Here the two soloists engage in a kind of playful yet purposeful repartee throughout. In the concluding moments of the piece, the players participate in a competitive game of one-upmanship utilizing a virtuosic cadential gesture consisting of a rapidly rising melodic figure, then a dramatic downward plunge followed by a rapid upward shift leading to a cadential trill (Example 10). Schema theorist Robert Gjerdingen labels this gesture ‘Coda’ in Music in the Galant Style, his classic study where he lays out the constituent motives and shared paradigmatic gestures or schema inimical to mid-eighteenth-century galant style and musical storytelling.Footnote 90 When discussing this concluding gesture in K.364, Gabriel Banat posits a direct link between this cadential figure and Bologne’s use of a strikingly similarly gesture in the opening Allegro moderato movement of his Violin Concerto in A major, op. 7 no. 1 (1782). Indeed, these ‘Coda’ schemas are essentially the same in that they both trace a stepwise melodic ascent to the upper reaches of the fingerboard followed by a large downward fall or plunge into the instrument’s lowest register, and a quick reversal up again to the closing cadential figure. In the Mozart example, the gesture functions as a recursive rising figure that rapidly gains energy through a prolonged upward-rising melody that eventually reaches the tonic pitch (e♭3) via a four-note stepwise ascent, only to catapult downward to the fifth scale degree in preparation for the concluding I64–V–I cadential pattern. The violist is the first to execute this virtuosic ascent and leap spanning a range of two-and-a-half octaves, followed by the violinist’s echo of three-and-a-half octaves.

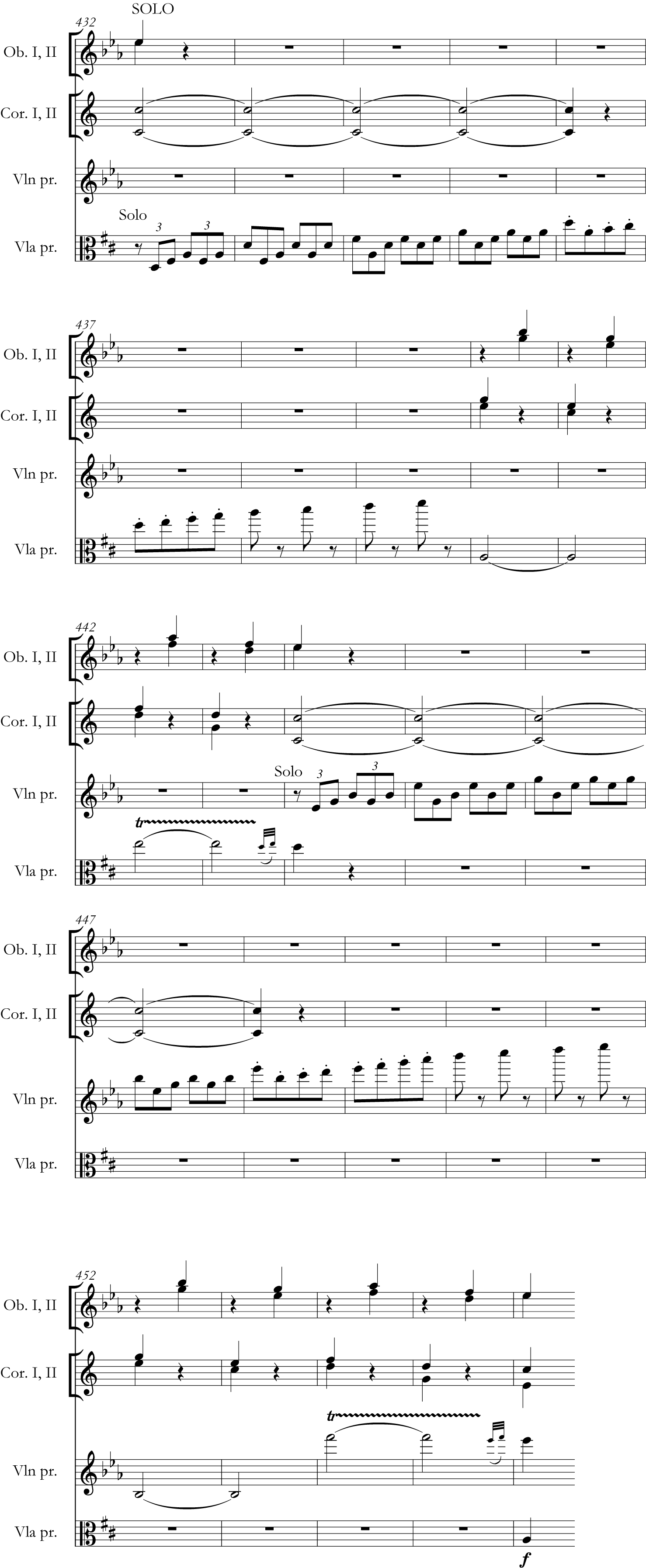

Example 10 Mozart, Sinfonie concertante in E♭ major, K.364, Presto third movement, with bravura closing gesture (in the viola, followed by the violin). Gesture consists of a rapid melodic rise up the fingerboard, then a sudden downward plunge, followed by a rapid upward shift to execute the trill, bb. 432–56. NMA Online (<https://dme.mozarteum.at/nma/>), published by the Mozarteum Foundation Salzburg in collaboration with the Packard Humanities Institute, 2006ff. Reproduced with kind permission of the Mozarteum Foundation.

Despite the similarity between these two schematic gestures described by Banat, it is also important to note their dissimilarities. Notably, Bologne’s occurs within a concerto for solo violin, whereas Mozart’s violin example appears in the context of a ‘concertante’ duet for solo violin and viola. In Bologne’s concerto movement, the solo violinist states the distinctive riff not once but twice within the opening (not final) movement: initially the gesture appears in the secondary key area (E major, as shown in Banat’s example); only at the second occurrence does the gesture become one of closure, leading to the cadence in the home key of A major. In each case, the solo violinist echoes their own phrase up the octave, as if engaging in a battle with oneself. For the listener, the effect of hearing this virtuosic cadential figure played twice within the same movement is electrifying. In contrast, by placing the virtuosic ascent and plunge ‘Coda’ gesture at the end of the finale in a symphonie concertante, as in the case of Mozart’s K.364, it serves as a closing device for the entire piece. By reserving this dramatic gesture/performative feat until the conclusion of the symphonie concertante, listener gratification for radical virtuosity is delayed until the very end. Similarly, in the Rondeau finale of the Violin Concerto in D major op. 4 (1774), Bologne incites the violin soloist (himself?) to reach up into the highest register of the instrument during the final statement of the main theme, captivating listener attention throughout the entire concerto by withholding the most virtuosic element in his musical arsenal until the climactic conclusion.

Floyd Grave identifies extensions and exaggerations of what he calls a ‘Grand Cadence’ prototype (Gjerdingen’s ‘Coda’) in several of Haydn’s string quartets, arguing that these virtuosic cadential gestures appearing in the first violin of selected quartets by Haydn often work to undermine rather than reinforce closure by creating overdrawn, comic, even hyperbolic closing gestures.Footnote 91 In these instances, the commanding gesture frequently signals the soloistic function of the first violinist within the string quartet texture. Just as this ratcheting up of soloistic flight draws attention to the first violin player’s rapid negotiation of the fingerboard and physical exertion, so too does Mozart’s use of the climactic gesture in the final moments of K.364 exploit the excess of the cadential formula to create what Grave describes as ‘performative extravagance’.Footnote 92 And it is this extravagant virtuosic display that signals the very presence of the composer-performer himself. But unlike Haydn whose ‘freakish’ formulae have a comic effect, those of Mozart and Bologne serve a different function. Bologne’s many uses of the ‘rise and plunge’ schema throughout his violin concerti and symphonies concertantes convey a sense of pure delight and revelry in virtuosic display, as if the violin were an instrument to be conquered, demonstrating the soloist’s (his) ability to do so in many different contexts and settings. Where Mozart differs is in using the twice-stated ‘Coda’ gesture in K.364 to foreground the violist and violinist in a form of musical combat, calling attention to the performers engaged in self-referential performativity. He raises the stakes for the soloists by having the violinist follow the violist, setting up a mini competition between the two players at the very end of the musical-theatrical drama. Will one succeed where the other falters? Or will the competition end in a draw?