Introduction

What explains the independence of successful specialized anti-corruption agencies (ACAs)? ACAs are believed to play indispensable roles in safeguarding democracy and are often dubbed the ‘fourth branch’ or the ‘guarantor’ institutions (Khaitan, Reference Khaitan2021; Tushnet, Reference Tushnet2021). They can act as quasi-judicial bodies to provide supplementary oversight mechanisms for dysfunctional and corrupt political systems. ACAs often possess greater expertise, integrity, and accountability than the deficient judicial and executive institutions embedded in the status quo political system.

However, we only have limited understanding of the sources of power and the determinants of independence for ACAs. In particular, ACAs carry out legal functions that are vulnerable to similar undue external influences as those faced by conventional judiciaries. Scholars have demonstrated the critical value of public opinion in judicial empowerment and the implications of favorable citizen attitudes cultivated over time for judicial independence (Strauss, Reference Strauss1984; Yackee, Reference Yackee2006; Staton, Reference Staton2010). In this study, we suggest that public disapproval of the dominant political regime boosts the institutional independence of ACAs against threats of external interference. We show that more favorable public attitudes toward ACAs relative to the favorability of the government empower ACAs and contribute to their operational independence. ACAs demonstrating greater sensitivity to public sentiments than other government bodies can capitalize on the differential public support for institutional protection (Vanberg, Reference Vanberg2004, Reference Vanberg2015).

Empirically, we leverage the unique setting of Hong Kong to examine the experiences of a model ACA, the Independent Commission Against Corruption (ICAC). We show that distinctively favorable public opinion of this legacy institution, due to its perceived effective anti-corruption efforts, has empowered its continued independence after Hong Kong’s return to Chinese rule in 1997. For the descriptive analysis, we construct an original dataset of the enforcement activities of the ICAC, spanning from 1974 to 2019, to compare the response patterns of the ICAC with those of other government agencies, in relation to their relative popularity. The evidence indicates that the ICAC is uniquely responsive to public sentiments. Its investigations are more active than the actual prosecutions and convictions of corruption cases, which are proceedings outside of the ICAC’s jurisdiction. The perceived superior effectiveness of the ICAC and negative appraisals of other government organs contribute to differential institutional trust and support.

Then, we conduct regression analyses to examine how perceived agency effectiveness and government integrity affect public support for the ICAC’s independent operations. We employ rarely used archival data on public opinion toward the ICAC from 1992 to 2019. The individual-level results suggest that the ICAC’s perceived effectiveness in tackling corruption strongly shapes public trust in the agency. Notably, while Hong Kongers may be concerned with the ICAC’s executive overreach, they are willing to tolerate the agency’s abuse of power and lack of oversight if the government is seen as lacking integrity. Such patterns explain the ICAC’s relatively resilient institutional independence.

By studying the case of Hong Kong as a field experiment of institutional change and resilience, this paper contributes to the scholarship on the sources of judicial empowerment in the context of specialized anti-corruption institutions (Woods and Hilbink, Reference Woods and Hilbink2009; Staton, Reference Staton2010). ACAs are often in a politically hazardous position similar to that of courts in terms of how to conduct inter-branch relations carefully so as to avoid confronting powerful actors (Ferejohn et al., Reference Ferejohn, Rosenbluth and Shipan2004; Clark, Reference Clark2010). Our results enrich the judicial politics literature which shows that a major source of judicial power to resist undue interference lies in popular support (Lehne and Reynolds, Reference Lehne and Reynolds1978; Caldeira and Gibson, Reference Caldeira and Gibson1995; Mondak and Smithey, Reference Mondak and Smithey1997). This study also provides lessons for ACAs around the world that try to survive challenging political environments, especially when citizens have become disenchanted by the separation of power and the checks and balances arrangements (Barbabela et al., Reference Barbabela, Pellicer and Wegner2022). ACAs should demonstrate such responsiveness to public opinion that differentiates the agency from the dysfunctional status quo political regime in public perceptions. People disillusioned with the dominant political regime will lend support to ACAs, especially when the latter’s independence is vulnerable to potential interference and threats by other political actors that lack the ACA’s prestige in comparison.

The role of public opinion in empowering anti-corruption institutions

Extant research on the fourth branch institutions, in particular the ACAs, focuses on their technical expertise in given issue areas, professionalism, and high degrees of independence as the institutional features needed to address systematic corruption problems in the status quo political regime (Strauss, Reference Strauss1984; Ackerman, Reference Ackerman2000; Tushnet, Reference Tushnet2021). Studies on the heterogeneity across ACAs’ capacities and effectiveness emphasize how certain structural designs enable them to fulfill their tasks, focusing mostly on organizational features such as the budgetary, staffing, and accountability mechanisms (Quah, Reference Quah2016, Reference Quah2010; Dixit, Reference Dixit2018; Khaitan, Reference Khaitan2021).

Meanwhile, similar to the position held by the judiciary, ACAs are inherently weak institutions that possess ‘neither the purse nor the sword’ (Caldeira, Reference Caldeira1986). Their relatively low political status vis-á-vis other branches of the government necessitates a strategy of carefully navigating the treacherous waters of inter-branch politics (Staton and Vanberg, Reference Staton and Vanberg2008; Staton and Moore, Reference Staton and Moore2011). Scholars have shown that a key source of judicial power is derived from public support (Caldeira and Gibson, Reference Caldeira and Gibson1992; Friedman, Reference Friedman2009). Powerful judicial institutions often succeed in capitalizing on the public’s political preferences to generate a popularity that protects the judiciary from encroachment by other state organs (Clark, Reference Clark2010). Therefore, courts have incentives to engage in public communication and strategic judicial activism that take advantage of favorable popular attitudes toward themselves and public distrust of other government branches (Lehne and Reynolds, Reference Lehne and Reynolds1978; Staton, Reference Staton2010). Importantly, the establishment of strong institutional legitimacy from favorable public perceptions allows the judiciary to enjoy ‘diffuse support’ even from citizens whose interests are harmed by the judicial decisions. This is a stronger indication of judicial independence than when the judiciary only receives ‘specific support’ for its activities that citizens perceive as beneficial (Gibson et al., Reference Gibson, Caldeira and Baird1998).

We argue that, in order to better understand the independence and power of ACAs, it is important to look beyond ACAs’ internal organizational attributes and designs. ACAs under threats of external interference construct their operational independence by responding to a lack of public confidence in the government. When the public hold negative appraisals of the prevailing political regime, ACAs can obtain distinctive reverence and support by being uniquely responsive to such public sentiments and by engaging in propaganda and communication campaigns to accentuate such institutional distinctions in public perceptions. In this way, the public will entrust greater power and discretion onto the ACA’s independent operations to tackle corruption, even acquiescing to potentially undesirable consequences. When there is a lack of top-down respect for institutional independence and integrity and an absence of political will to fight corruption (Peiffer and Alvarez, Reference Peiffer and Alvarez2016; Quah, Reference Quah2016; Peci, Reference Peci2021), ACAs’ independence can be boosted by tapping into unsatisfied public demands.

How the ICAC obtains power and independence

Many governments establish independent ACAs to improve domestic and international actors’ trust in the integrity of the government, as such trust may bring significant economic benefits to the country. International donors, investors, and funding agencies are more likely to engage with countries that have effective and independent ACAs (Doig, Reference Doig1995; Rose-Ackerman, Reference Rose-Ackerman2012; Zhu and Shi, Reference Zhu and Shi2019). For instance, one factor that kept the Lithuanian parliament from tempering with its ACA, the Special Investigation Service (STT), was the mission-dollar grant from the USA that was conditioned upon the STT remaining independent (Kuris, Reference Kuris2012 a). In Slovenia, the 2008 financial crisis alerted the public to the country’s systematic corruption issues, which significantly strengthened and pressured its Commission for the Prevention of Corruption (CPC) to address Slovenia’s economic ruin and mismanagement (Kuris, Reference Kuris2013). Hungary recently established its own anti-corruption agency, the Integrity Authority, to unlock funds from the European Union previously suspended for corruption concerns. Footnote 1

In this regard, the Hong Kong government, the British Colonial government, and the central government in Beijing are all aligned in their attitudes toward the ICAC – they ultimately share the same incentive of maintaining the city’s economic prosperity and its status as a financial and investment hub. However, governments also face a common trade-off in ensuring the independence and effectiveness of their ACAs. The government itself is often both the principal and the target of anti-corruption enforcement (Di Mascio et al., Reference Di Mascio, Maggetti and Natalini2020). When the government lacks public support for its role as the regulatory principal, it needs to delegate more independence and power to the ACA in order to maintain public confidence in governance integrity. When the government enjoys greater public confidence in its regulatory power, such a legitimacy advantage reduces its pressure as a regulatory target and shrinks the spaces of operational autonomy of the ACA.

The ACA’s power: sources and constraints

The Independent Commission Against Corruption was established by the British colonial government in 1974, in response to a high-profile corruption scandal (Quah, Reference Quah2011). The Prevention of Bribery Ordinance and the Basic Law of Hong Kong (Article 57) provide legal guarantees for the de jure independence of the ICAC. Footnote 2 The agency is directly accountable to the top governing official of Hong Kong, i.e., the colonial Governor before 1997 and the Chief Executive ever since. The ICAC Ordinance also stipulates that the Commissioner, i.e., its top executive official, is only subject to the orders, direction, and control of the Governor or the Chief Executive. Footnote 3

One feature that distinguishes the ICAC from similar agencies in other countries, such as the Singapore Corrupt Practices Investigation Bureau, is its heavy emphasis on public relations and education. From the very beginning, the ICAC has been conscientiously cultivating a cordial relationship with the community, and part of its mission is relying on public support to overcome operational resistance (Scott and Gong, Reference Scott and Gong2018). The agency is known for adopting a ‘throng-pronged’ approach focusing on law enforcement, prevention, and community education. The ‘Community Relations Department’ is responsible for the educational function and engages in extensive outreach and anti-corruption propaganda efforts. Crucially, the department makes broad use of media to publicize the work of the ICAC and also integrates media programs with face-to-face contact to enhance the agency’s publicity, aimed at enlisting public support to fight corruption. Footnote 4

The ICAC’s comprehensive strategy to manage community relations differentiates itself from the rest of the Hong Kong government, which has been conventionally and also increasingly perceived as alienated from and unaccountable to the public (Jones, Reference Jones2015). The agency’s strategy to win the hearts and minds of Hong Kongers has changed public attitudes toward corruption and a new consensus emerged in Hong Kong regarding good governance values and proper norms of government conduct (Klitgaard et al., Reference Klitgaard, Abaroa and Parris2000; Manion, Reference Manion2004; Scott and Gong, Reference Scott and Gong2015) As a result, the ICAC enjoys a reputation and political status distinctive from other branches of the government that are more detached from public sentiments (Gong andWang, Reference Gong and Wang2013; Jones and Vagg, Reference Jones and Vagg2017). This feature of their institutional legacy is crucial in the post-1997 era as the government suffers from waves of popularity crises.

Another important feature of the ICAC is that it does not have the formal power to conduct independent prosecutions. It is officially stipulates that ‘[a]fter completion of investigations, the power to prosecute is vested with the Secretary for Justice, and the separation of powers ensures that no case is brought to the courts solely on the judgement of the ICAC.’ Footnote 5 Therefore, the constitutional and procedural guarantees for the agency’s independence are very much limited to its investigative power instead of prosecutorial or adjudicative power. Conventionally, the distinction between anti-corruption investigations and prosecutions has not been an acute issue, given that the Secretary for Justice is a member of the executive office and also answers to the top executive official of Hong Kong. However, such an institutional design has led to more pronounced outcomes when the ultimate source of executive power changed hands with the sovereignty handover in 1997, Footnote 6 which has rendered the executive branch particularly vulnerable to mainland Chinese influences.

Independence empowered by public opinion

We argue that the key to the ICAC’s success has been its attentiveness toward public sentiments against the prevailing political regime. It takes advantage of public disapproval of the government by forging public perceptions of its enforcement effectiveness. The agency demonstrates ostensibly that its enforcement activities are responsive to popular demands and concerns, as a sharp contrast to the insensitivity of the ruling regime. When other government organs are regarded as lacking integrity and resilience, public perceptions of the ICAC’s unique effectiveness are translated into supportive attitudes toward its independence. Therefore, even though the government does not agree with the agency’s enforcement decisions, it has to respect agency independence when the momentum of public opinion is turned against the government.

This mechanism was manifested in the early years of the ICAC when corruption was still widespread and deeply entrenched in Hong Kong (Quah, Reference Quah2011). There was little public trust in the original Anti-Corruption Office, a specialized anti-corruption unit within the police force, to effectively and impartially sanction corruption, because the police force was notoriously corrupt itself (Manion, Reference Manion2004). The ICAC tapped into strong public distrust and disapproval of the corrupt status quo institutions and demonstrated through its comprehensive strategy that the agency can be trusted and relied upon to reduce corruption. Citizens started to shift their expectations about the proper norms of official conduct and the acceptable boundaries of the ICAC’s role in fighting corruption and ensuring government compliance with the law. A gradual build-up of institutional prestige has led to growing independence of the quasi-judicial body (Carrubba, Reference Carrubba2009; Vanberg, Reference Vanberg2015).

This mechanism also explains how the de facto independence of the ICAC has largely survived the transfer of sovereignty. Since the return of Hong Kong to Chinese rule in 1997, the formal, structural guarantees of the agency’s independence have become more politically fragile de facto (Scott and Gong, Reference Scott and Gong2018). The agency has tried to appear keenly responsive to public opinion, as a channel of institutional redress for public grievances against the dominant regime’s inaction. The agency’s public opinion campaigns also aim to uphold values of clean governance and to maintain its reputational prestige as a legacy institution that champions traditional integrity norms, Footnote 7 which offers a sharp contrast to the rest of the Hong Kong government. Therefore, one empirical implication of our theory is that, differential public support toward the ICAC versus the government will affect agency operation.

H YPOTHESIS 1 (H1): ICAC enforcement is more active when public support for the agency is high and public appraisal of the government is low.

Extant research on the expansion of judicial power suggests that the construction of distinctive judicial legitimacy would allow judicial institutions to exercise such independent discretion, that their decisions are still accepted even if citizens’ personal interests are harmed (Ginsburg, 2007; Staton and Vanberg, Reference Staton and Vanberg2008; Carrubba, Reference Carrubba2009). In the case of the ICAC, as public support for the government wanes and waxes, the agency has enjoyed a consistently distinguishable reputation. Therefore, a second implication of our theory is that citizens should only support constraining the ICAC’s enforcement discretion when government integrity is considered intact. Meanwhile, as long as the government is perceived as corrupt, the ICAC’s potential overreach will be tolerated. Given the judicial politics literature, this would provide a strong test for agency independence – the ICAC enjoys support for unfettered discretion even if the public perceive it as abusing its power and lacking oversight.

HYPOTHESIS 2 (H2): Citizens support the ICAC’s operational independence when they hold unfavorable views of the government.

In the empirical analysis, we show evidence supporting the hypothesized relationships between public sentiments and ICAC independence.

The empirical analysis

In this section, we describe our empirical design and the results. We introduce two main data sources: (1) a manually coded dataset of the enforcement activities of the ICAC and (2) annual public opinion surveys of public perceptions of the ICAC and of corruption control efforts. We present descriptive evidence at the city level with yearly variations and conduct a series of regression analyses at the individual level to provide consistent empirical support for our theory.

Descriptive evidence from ICAC data

ICAC Enforcement Patterns

We first investigate the relationship between ICAC enforcement and the anti-corruption sentiments of Hong Kong citizens. The official website of the ICAC publishes annual reports on its work and performance. Footnote 8 We manually compiled a dataset containing information related to the enforcement activities of the ICAC from 1974 to 2019 at the year level. The variables include the total number of corruption complaints received by the ICAC, the total number of cases investigated by the ICAC, the number of persons prosecuted by the ICAC, and the number of persons convicted by the court.

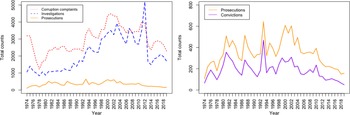

Figure 1 compares the ICAC’s investigation patterns with the functioning of other government organs, which demonstrates the agency’s greater sensitivity and responsiveness toward public demands. On the left, the total number of investigations (the blue line) conducted by the ICAC largely tracts the number of complaints (the red line) received each year. Footnote 9 However, the number of prosecutions (the orange line) does not closely reflect the number of investigations concluded each year, and the divergence quickly increased after 1997. This crucial difference can be attributed to the institutional design: the ICAC does not have the ultimate authority to make prosecutorial decisions, which is vested with the Secretary for Justice. On the right, the number of convictions handed down by Hong Kong courts (the purple line) is highly correlated with prosecution numbers. The closer association between the prosecution and the conviction of corruption cases stands in contrast with the way these regime institutions stay aloof from public sentiments. The ICAC’s demonstrably greater sensitivity to public concerns has contributed to the ability of this fourth branch institution, as part of the executive branch, to differentiate itself from and transcend public evaluations of the overarching regime.

Figure 1. ICAC enforcement activities.

In the following sections, we use public opinion data to show that Hong Kongers have developed highly stable support and trust for the ICAC. Meanwhile, even though perceived corruption is generally in decline, other government bodies do not enjoy similar popularity. Such a structure of differential support will empower the agency to pursue independent actions when the public hold unfavorable views of the regime.

Public Opinion Surveys of the ICAC

The ICAC conducts annual surveys of its own work. Footnote 10 The surveys employ detailed questions to assess a variety of public attitudes toward the ICAC and its work as well as public opinion about corruption-related issues in Hong Kong. Footnote 11 From 1992 to 2019, around 1,500 persons were randomly selected for interviews each year. Footnote 12 The fact that the ICAC has been consistently conducting such meticulous surveys to gauge public perceptions is itself evidence that the institution is keenly aware of and values its public image.

The citizens’ corruption perceptions and different indicators of support for the agency after a decade since its establishment suggest that the ICAC is perceived as highly effective and trustworthy. The percentages of respondents who perceive corruption as common and have personally experienced corruption declined from 56% and 9.0% in 1993 to 26% and 1.6% in 2019, respectively. We use two survey questions to gauge public attitudes toward the agency. The first one asks respondents whether they believe that the ICAC ‘deserves your support’ (ICAC support). The second question asks respondents’ willingness to report corruption to the ICAC if they were aware of it. We compare the variability of these two indicators with support indicators for other government institutions: the Chief Justices of Hong Kong and the Hong Kong government as represented by the Chief Executive in office (Government Appraisal). Footnote 13

The results suggest that the ICAC has enjoyed distinctively greater stability in its public reputation than the institutions of the Chief Justices and the executive branch in general. In Column (1) of Table 1, we conduct two-sample F-tests to compare the variances of the indicators of support for the ICAC and the Chief Justices, arguably the two most revered institutions in Hong Kong. The ratio of two variances shows that the variability of Support for the IAC is significantly smaller than that of Support for the Chief Justices. Footnote 14 The difference remains large and significant even after standardizing the values through dividing them by their means – the standardized variance of ICAC support is only 5% of that of Chief Justice support. The F-tests in Column (2) of Table 1 show that there is also less year-by-year volatility in respondents’ willingness to report to the ICAC than in their appraisals of the government: after standardization, the variance of the former is less than half of that of the latter. Also, during the years of low government appraisals, popular trust in the ICAC remained at very high levels. In 2019, when the GA score was at a historical low level of 74.3, the proportion of respondents willing to report corruption was at a historical high level of 81.14%. Footnote 15 Such patterns offer further evidence that the ICAC is endowed with distinctive popular support to empower its institutional independence against regime influences.

Table 1. Comparing variability in institutional reputation

Note: Results from a two-sided F-test to compare variances between two samples.

The agency’s long tradition of keen attention, responsiveness, and sensitivity to public opinion is also reflected in the remarks of Bertrand de Speville, the former commissioner of the ICAC (Kuris, Reference Kuris2015 a),

‘If a citizen has screwed up his courage to come and tell you something, if you treat him or his complaint as insignificant, he will never come to you again. You’ve lost him, and you’ve probably lost all his friends as well’.

Operational Responsiveness Driven by Public Sentiments

In this section, we leverage the yearly variations in the ICAC’s enforcement activities to further demonstrate the agency’s sensitivity to public sentiments given the relative favorability of different government organs. Because of the limited timeframes of ICAC enforcement actions (1977–2019) and of public opinion surveys (1992–2019), year-level regression analysis on this small sample is not informative. Footnote 16 Therefore, we conduct t-tests to compare between judicial responses under contrasting public sentiment conditions. The empirical patterns highlight the importance of a favorability gap between the ICAC and other government institutions in terms of pushing for more ICAC investigations and even forcing convictions.

In Table 2, we first divide the full sample into two subsets by the median values of ICAC support (Panel A). Then, we further divide the two samples into four scenarios based on the median value of Government appraisal (Panels B and C). To capture the responsiveness of different institutional mechanisms, we use four different indicators: the total number of investigations, investigation rates

![]() $\left({{{\rm{Total}}\,{\rm{number}}\,{\rm{of}}\,{\rm{ICAC}}\,{\rm{investigations}}} \over {{\rm{Total}}\,{\rm{number}}\,{\rm{of}}\,{\rm{corruption}}\,{\rm{complaints}}}}\right)$

, prosecution rates

$\left({{{\rm{Total}}\,{\rm{number}}\,{\rm{of}}\,{\rm{ICAC}}\,{\rm{investigations}}} \over {{\rm{Total}}\,{\rm{number}}\,{\rm{of}}\,{\rm{corruption}}\,{\rm{complaints}}}}\right)$

, prosecution rates

![]() $\left({{{\rm{Total}}\,{\rm{number}}\,{\rm{of}}\,{\rm{prosecuted}}\,{\rm{corruption}}\,{\rm{cases}}} \over {{\rm{Total}}\,{\rm{number}}\,{\rm{of}}\,{\rm{ICAC}}\,{\rm{investigations}}}}\right)$

, and conviction rates

$\left({{{\rm{Total}}\,{\rm{number}}\,{\rm{of}}\,{\rm{prosecuted}}\,{\rm{corruption}}\,{\rm{cases}}} \over {{\rm{Total}}\,{\rm{number}}\,{\rm{of}}\,{\rm{ICAC}}\,{\rm{investigations}}}}\right)$

, and conviction rates

![]() $\left({{{\rm{Total}}\,{\rm{number}}\,{\rm{of}}\,{\rm{convicted}}\,{\rm{corruption}}\,{\rm{cases}}} \over {{\rm{Total}}\,{\rm{number}}\,{\rm{of}}\,{\rm{prosecuted}}\,{\rm{corruption}}\,{\rm{cases}}}}\right)$

.

$\left({{{\rm{Total}}\,{\rm{number}}\,{\rm{of}}\,{\rm{convicted}}\,{\rm{corruption}}\,{\rm{cases}}} \over {{\rm{Total}}\,{\rm{number}}\,{\rm{of}}\,{\rm{prosecuted}}\,{\rm{corruption}}\,{\rm{cases}}}}\right)$

.

Table 2. Institutional responsiveness under different conditions

Note: The table shows results from two sample t-tests comparing the average values of different legal proceeding indicators under two contrasting scenarios, respectively.

Panel A shows that, without considering government popularity, the ICAC is significantly more active in conducting investigations when it enjoys relatively high (above the median level) levels of public support than under low levels of public support (below the median level). It produces a higher average number of investigations (3251 v.s. 2319) as well as a higher investigation rate (0.863 v.s. 0.763), respectively, with statistically significant differences in both measures. ICAC investigations are also more likely to result in eventual convictions when empowered by higher than lower public support, with average conviction rates of 0.508 and 0.463, respectively. However, Panel B indicates that when the government is relatively favorable (above the median level), then the ICAC’s own popularity is much less relevant. High support for the ICAC does not empower the agency to be more active in investigation, and the conviction rate is also not significantly higher than that in the low support scenario. In comparison, Panel C shows that, when public appraisal of the government is low (below the median level), greater ICAC support is associated with significantly greater vigor in investigation and more success in forcing convictions. The ICAC conducts the most investigations on average (3775) and achieves the highest investigation rate (0.906) during times when it enjoys relatively high support from citizens who are dissatisfied with the government. Footnote 17

In summary, Table 2 provides descriptive evidence to suggest that differential public support toward the ICAC vis-à-vis the whole ruling regime may empower the agency’s institutional independence. When regime support is low, it becomes more crucial for the ICAC to tap into a strong support base to engage in more active enforcement. Riding on a wave of government unpopularity also helps the ICAC secure more convictions.

Cases of ICAC Responsiveness

Several major instances in the ICAC’s history demonstrate that the agency’s responsiveness is affected by and corresponds to shifts in citizens’ relative evaluations of different government bodies. There was a notable jump in corruption reports in 1993 and shortly before and after 1997, which has been attributed to increased economic interactions with mainland China which embarked on more market-oriented reforms in 1993 (Chan, Reference Chan2001; Manion, Reference Manion2004; Jones, Reference Jones2015; Lo, Reference Lo2016). There were growing concerns and fears that more economic interactions between Hong Kong and mainland China would create more opportunities for corruption (Johnston, Reference Johnston2022; Li and Lo, Reference Li and Lo2018). The ICAC’s own surveys in 1994, 1995, and 1996 indicated that 72.6%, 71.7%, and 69.7% of respondents, respectively, believed that corruption would rise after 1997. The ICAC responded by enhancing cross-boder cooperation with mainland China, developing more sophisticated technologies, and designing educational and awareness programs for the ‘new immigrants’ from mainland China. The ICAC relied heavily on NGOs in its campaign to provide easily accessible information to new immigrants regarding Hong Kong’s anti-corruption laws. The ICAC compiled various materials, such as CDs and videos, and distributed them to all NGOs dealing with new migrants. The ICAC’s regional offices also organized English courses for new migrants that drew on examples from Hong Kong’s anti-corruption laws and the agency’s experience and practices (Scott, Reference Scott2013; Xiao et al., Reference Xiao, Scott and Gong2022).

Given rising instances of conflict of interests and concerns about a norm shift in Hong Kong, the ICAC strengthened its regulation over misconduct in public office. In 2005, a former senior civil servant, Elaine Chung, was alleged to have engaged in inappropriate lobbying for a private sector company seeking large government contracts. The scandal provoked strong responses in the media that accused the government, which accepted the civil servant’s argument, of neglecting potential conflict of interest implications of post-public employment and of a failure to monitor employment undertaken by former civil servants. As a policy response, the ICAC started the Ethical Leadership Programme in 2006 that appointed Ethics Officers, who are senior government officials, to every bureau and department to provide integrity management. The program aims at maintaining Hong Kong’s traditional rule-based checks on corruption and puts great emphasis on values of integrity in professional behavior (Scott and Leung, Reference Scott and Leung2012; Scott, Reference Scott2013).

More recently, Hong Kong has witnessed increased political turbulence that reflected citizens’ growing distrust of the ruling regime, including the Umbrella Movement in 2014. Meanwhile, the ICAC investigated a series of high-profile corruption cases amidst the political upheavals that impaired public confidence in the government. The former Chief Secretary for Administration, Rafael Hui, was arrested on corruption charges by the ICAC in 2012 and was subsequently convicted and sentenced to 7.5 years in prison. Footnote 18 The former Chief Executive, Donald Tsang Yam-kuen, was also charged with inappropriately accepting advantages provided by a businessman in 2015, although his 12-month prison term conviction was successfully appealed in court. Footnote 19 The ICAC also brought his successor, Leung Chun-ying, under intense public scrutiny for reported failure to declare receiving payments from the sale of a business while serving as the Chief Executive. Footnote 20

While these high-profile cases tarnished the government’s image, they did not affect public trust in the ICAC. The ICAC’s reputation has remained robust throughout various episodes of legitimacy crises. According to a survey conducted by Xiao et al. (Reference Xiao, Scott and Gong2022) in 2020, 47% of the respondents indicated that their view of the Hong Kong government had changed ‘a great deal’ because of its handling of the Anti-Extradition Bill protests in 2019, whereas only 16% said that their view of the ICAC had been so affected. The survey also asked respondents to compare their trust in the ICAC with that of their trust in other institutions, and the majority indicated that they trusted the ICAC more than the other agencies, including the police force, the political parties, the Legislative Council, and government departments. Also, Xiao et al. (Reference Xiao, Scott and Gong2022) find that among those who trust the ICAC, 352 out of 877 (40%) do not trust the government.

In the following section, we conduct regression analyses at the individual level to show further evidence that the ICAC’s institutional responsiveness and independence depend heavily on citizens’ negative views of the regime.

Differential perceptions driving ICAC independence

In this section, we use the individual-level public opinion survey data collected by the ICAC to examine how Hong Kongers’ individual perceptions of the ICAC vis-á-vis the government affect their support for the agency’s independence. The survey results are reported annually from 1992 to 2019, which reflect public sentiments in the previous year, i.e., from 1991 to 2018.

Dependent Variables

We examine the determinants of two dichotomous outcomes: (1) citizens’ willingness to report incidents of corruption to the ICAC and (2) citizens’ concerns about the ICAC’s excessive power. The first dependent variable aims to capture popular trust in the ICAC’s operations. The willingness to report crimes to the law enforcement agency is commonly used as a proxy for public trust in institutional operations (McIntyre, Reference McIntyre1967; Tyler and Huo, Reference Tyler and Huo2002; Miller and Segal, Reference Miller and Segal2019). Citizen engagement and behavioral support for an ACA’s functioning are crucial for its operational independence (Quah, Reference Quah2008). ACAs, like other law enforcement agencies, rely on independent and reliable channels of citizen input for actionable intelligence. Their ability to obtain exclusive and confidential sources of information from frequent contact with citizens helps insulate and empower the agency against external influences (Meagher, Reference Meagher2005; Rengifo et al., Reference Rengifo, Slocum and Chillar2019)

The second variable is coded based on responses to two survey questions: (1) ‘Do you think the ICAC’s powers are too large, too small or appropriate?’ and (2) ‘Do you think the external supervision & control for the ICAC should be increased, decreased or unchanged?’ The dependent variable Constraining ICAC Discretion is coded as 1 if the response to question (1) is ‘Too large’ OR if the response to question (2) is ‘increased.’ Footnote 21 In other words, Constraining ICAC Discretion equals 1 when the respondent believes that the ICAC’s power is too large or there should be more external supervision and control over the ICAC. And a value of 0 would imply that the respondent accepts or supports the discretionary power and independence of the ICAC. These two questions only appear in surveys conducted from 1994 to 2009, which reduces the sample size.

Considering both outcomes together, the ICAC is expected to enjoy greater independence when citizens are willing to (1) support agency functions by reporting corruption incidents and (2) not constrain agency discretion in exercising its power (Smith, Reference Smith2009). We will show the conditions under which both outcomes are realized for the ICAC.

Independent variables

The first explanatory variable is the respondent’s perceived effectiveness of the ICAC. It is measured based on responses to the question ‘Do you think ICAC’s anti corruption work is effective?’ The responses are ordinal values scaled as ‘Very effective’ (5), ‘Effective’ (4), ‘Average’ (3), ‘Ineffective’ (2), and ‘Very ineffective’ (1). This measurement of effectiveness is positively and significantly correlated with the binary indicator of ICAC support as used in Table 1. Footnote 22 Moreover, this ordinal scale variable has greater variation than the binary indicator of public support, Footnote 23 which we leverage to capture the nuanced changes and fluctuations in public attitudes toward the ICAC.

The second explanatory variable is related to government integrity. Govt lacking integrity is measured according to the question ‘How widespread do you think corruption is in government departments?’ The ordinal responses include ‘In most government departments,’ ‘In a number of government departments,’ ‘Only in one of two government departments,’ and ‘No corruption in the government at all.’ Govt lacking integrity is coded as 1 if the respondent believes that corruption is ‘In most government departments’ or ‘In a number of government departments.’ Perceptions of widespread corruption in government departments erode trust in the political regime and sow doubts about the government’s own willingness and ability to fight corruption (Beesley and Hawkins, Reference Beesley and Hawkins2022). Such concerns existed in Hong Kong’s colonial era (Goodstadt, Reference Goodstadt2005) and are also frequently discussed in the modern era media (Bowring, Reference Bowring2014; Chen, Reference Chen2014).

We control for a set of individual-level characteristics that may confound the relationship between the explanatory variables and the outcome variables. The dummy control variables include: the year of survey response, the respondent’s level of education, the respondent’s level of income, and the respondent’s age group (Reinikka and Svensson, Reference Reinikka and Svensson2006; Truex, Reference Truex2011). Footnote 24 In addition, we take into account the respondent’s perceptions of the pervasiveness of corruption in general in Hong Kong. It is a binary indicator of whether the respondent believes that corruption is common in the society. This control tries to capture citizens’ baseline perceptions of corruption levels, so that we are more confident that it is not public (dis)satisfactions with the overall status quo corruption environment that drive the results; but instead it is public attitudes toward the ICAC relative to those toward the government that matter for the agency’s empowerment.

Regression analyses and results

We run logit regressions to examine the individual-level determinants of ICAC empowerment and independence. In addition to analyzing the full sample of years from 1994 to 2009, we break down the sample into three time periods based on two critical junctures, 1997 and 2002. The year 1997 is the year of the sovereignty transfer, as noted above. The year 2002 is a critical juncture in Hong Kong’s political development in the post-transfer era. It is the first time the National Security Bill was introduced by the Hong Kong government, through amending Article 23 of Hong Kong Basic Law. The proposed bill caused considerable controversy and set off mass demonstrations in 2003, which were also the first large-scale mass protests since 1997. The bill was then shelved indefinitely until the newly legislated National Security Law was imposed in 2020. Compared with the year 1997, believed to foreshadow a more hostile environment for the ICAC (Fu et al., Reference Fu, Petersen and Young2005), events in 2003 raised concerns that the ICAC may be used as a national security agency to engage in ‘political policing’ (Fu and Cullen, Reference Fu and Cullen2003). These watershed events heightened Hong Kongers’ sensitivity to politicized governance and institutional incompatibility between the pre-1997 administrative structure and the post-1997 political environment (Cheung, Reference Cheung2005).

“Descriptive evidence from ICAC data section shows evidence that the ICAC enjoys a distinctively unique reputation among citizens that separates itself from the government. Meanwhile, as the ultimate source of power of the HK government changed hands in 1997, citizens faced greater uncertainty about the city’s political climate. Therefore, we expect to see perceptions of government integrity becoming more crucial for public attitudes toward the ICAC after 1997. Given concerns about the ICAC being weaponized for national security purposes, citizens should be more wary of ICAC overreach if they do not perceive the government as corrupt. Also, while citizens should be more likely to report corruption to the ICAC if the agency is perceived as effective and the government as corrupt, they should be less inclined to do so as they grow more concerned about the ICAC’s abuse of discretion.

Table 3 shows the results. In Model (1), we find a positive and significant direct effect of favorable perceptions of the ICAC on support for its functions, as measured by the willingness to report corruption to the agency. In terms of substantive effects, giving a one-point higher score on the ordinal scale of perceived ICAC effectiveness leads to a 3.6% points increase in the likelihood of reporting corruption, on average. The results remain robust after controlling for Govt lacking integrity in Model (2). In Model (3), we interact ICAC effectiveness with Govt lacking integrity to examine how respondents’ relative perceptions of the ICAC versus the government affect their attitudes toward the ICAC. The results show that, for both respondents who consider the government to be corrupt and those who do not, the more effective they deem the ICAC to be, the more likely that they will report corruption to the agency. Furthermore, the positive and significant interactive effect suggests that those who perceive the government as lacking integrity are much more likely than other respondents to resort to the ICAC (6.5 v.s. 2.7 pct points more likely), given a one-point increase in the ordinal effectiveness score.

Table 3. Perceived ICAC effectiveness sustains its functioning under adverse institutional environments

Note: *P < 0.1; **P < 0.05; ***P < 0.01.

Models (7), (8), and (9) show the full sample results for the second outcome of interest: the conditions under which the ICAC enjoys greater discretion. The dependent variable measures whether respondents want to constrain the agency’s discretionary power, which would limit its independence. Ever since the ICAC achieved significant success in the late 1970s and 1980s, there have been concerns that the agency’s authority is too vast and underconstrained, which could be threatening to a society that values a small and limited government, and that the agency’s potential executive overreach may hurt its own legitimacy (Skidmore, Reference Skidmore1996; Choi, Reference Choi2009). Models (7) and (8) show that respondents with better perceptions of ICAC effectiveness are, at the same time, more likely to express concerns about its excessive power. Meanwhile, Model (9) shows that concerns about the ICAC’s excessive discretionary power are mostly reserved by people who do not believe that the government lacks integrity. In other words, citizens who do hold negative views of the government are much less likely to support constraining the ICAC’s discretion.

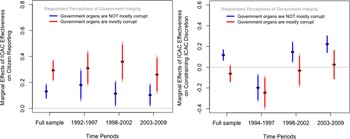

Taken together, the full sample patterns reveal two types of considerations related to ICAC independence: while citizens are willing to report to the ICAC due to trust in its effectiveness, they may also be alerted by the fact that the highly effective agency possesses too much power and thus needs more oversight. Next, we investigate potential subsample heterogeneities across the three time periods divided by the two critical years of 1997 and 2002. In Fig. 2, we visualize the coefficients for the interactive effects regarding the two outcome variables, respectively, for the full sample as well as the three time periods. Fig. 2(a) corresponds to results in Models (3)-(6), and Fig. 2(b) corresponds to results in Models (9)-(12).

Figure 2. Institutional perceptions and ICAC independence.

Note: The blue and red thin lines represent the 95% confidence intervals around the point estimates.

The subsample results show that the positive and significant interactive effects for both dependent variables are mostly driven by the post-1997 period – the public have become increasingly concerned about government integrity and political influences over ICAC operations. During 1994–1997, there are no statistically distinguishable differences between citizens who view a corrupt government and those who view a non-corrupt government when it comes to their reactions to perceived ICAC effectiveness.

Figure 2(a) shows that during 1998–2002, in contrast, perceived ICAC effectiveness drives respondents to report corruption more strongly if the respondents perceive the government as corrupt (the red bar) than otherwise (the blue bar). In other words, those who view the government as corrupt have become much more motivated by positive ICAC evaluations to support the agency’s function, compared with those favorably disposed toward the regime. Meanwhile, protests around the proposed National Security Bill raised people’s alarm about potential misuses of power by the ICAC. As a result, such considerations diminished the encouragement effects of perceived ICAC effectiveness, as citizens started to heed the potential downsides of overzealous anti-corruption enforcement. This is evidenced by the smaller coefficients for the direct and interactive effects of ICAC effectiveness in Model (6) than those in Model (5).

Figure 2(b) shows that, in the years running up to the transfer of sovereignty (1994–1997), government integrity was not a salient issue when it comes to constraining ICAC discretion,. During that time period, citizens were much more worried about potential corruption spillovers due to closer economic ties with mainland China (Cheng, Reference Cheng2007; Li, Reference Li2016) than the incumbent regime’s lack of integrity. Respondents holding both favorable and unfavorable views of the government are less supportive of constraining the ICAC if they appreciate the agency’s effectiveness, with no significant difference in such attitudes between the two groups. This pattern may be driven by their shared concerns about a likely surge in cross-border corruption (Lee, Reference Lee1992) and shared expectations of the value of the ICAC in tackling this problem.

In comparison, after the change in the ultimate source of power for the Hong Kong government in 1997, respondents who consider the government as clean (Govt lacking integrity = 0) have become more likely to express concerns about the ICAC’s unchecked discretion. Respondents will only exhibit greater tolerance for the ICAC’s executive overreach, i.e., not supporting discretionary restraint, when the government is deemed mostly corrupt (Govt lacking integrity = 1). After 2003, citizens have become even more wary of the ICAC’s excessive power behind its effectiveness if they view the government favorably. It is evidenced by the larger coefficient for ICAC effectiveness in Model (12) than that in Model (11). Yet, Fig. 2(b) also shows that those perceiving a corrupt government are still unwilling to limit the ICAC’s power if they find its work effective. The differences in such attitudes point to the competing concerns after 2003 about potential weaponization of the ICAC – whether the public will tolerate the ICAC’s overreach depends on the government’s perceived integrity, or the lack thereof. Also, the political conditions after 1997, especially after 2003, provide a hard test for citizens who still embrace the ICAC’s operational discretion, as they are willing to accept its potential power abuses. Such patterns are evidence of strong diffuse support for, and hence the independence of, the ICAC (Gibson and Caldeira, Reference Gibson and Caldeira1995; Gibson et al., Reference Gibson, Caldeira and Baird1998). The empirical patterns also lend support to the importance of differential support: it is not positive or negative assessment of the ICAC per se that contributes to its empowerment; positive evaluations of ICAC operations only result in more enforcement discretion when the dominant regime has lost its integrity in public eyes.

Overall, the results confirm the expectation that perceived government integrity has become a more important factor for citizen attitudes toward the ICAC after 1997. After 2003, in particular, respondents show signs of competing considerations regarding, on the one hand, the ICAC’s discretionary power to check a discredited government and, on the other hand, the agency’s potentials of misusing its excessive power. Therefore, the key to the ICAC’s independence is a structure of differential support toward the agency vis-á-vis the dominant political regime. For citizens, checking the ICAC’s power and limiting its discretion will be desirable when the government is well regarded; the ICAC’s institutional effectiveness is more valued when the ruling regime is less trustworthy.

When the Public Report to the ICAC

In Table 4, we calculate the predicted probabilities of public reporting to the ICAC under the 20 combinations of the indicators for ICAC effectiveness and government integrity, respectively. It shows that moving up one scale in the Perceived ICAC effectiveness score leads to a 6–7% points increase, on average, in the probability of reporting to the ICAC if the government is perceived as mostly corrupt (Most departments). In comparison, it only leads to a 1–2% points increase, on average, in reporting probability if the government is perceived as clean (No corruption). The higher baseline probabilities of public reporting when the government is perceived as clean should reflect the good governance equilibrium in many countries: citizens actively engage with and support the law enforcement and perceived agency effectiveness does not affect citizen behavior that much. However, the challenge in many corrupt societies, also where the ICAC succeeds, is in encouraging citizens to report to the ACA even when the government is perceived as corrupt. The results suggest that, as long as the agency is considered effective, citizens are about equally likely to report to the ICAC whether the government is considered corrupt or not. It is also noteworthy that the probabilities of public reporting only slightly decreased in 2004, compared with 1997, which showcases the resilience of the ICAC’s reputation.

Table 4. Increased effectiveness boosts reporting when Govt. Viewed as corrupt

Note: The numbers indicate the predicated probabilities of respondents’ reporting corruption to the ICAC for the year of 1997 and 2004 (1997 → 2004), respectively.

Cases beyond the ICAC

Many ACAs around the world attempt to capitalize on differential public trust toward the agency vis-à-vis the government as a whole. Some ACAs adopt strategies similar to the ICAC to increase public trust in the institution, focusing on citizen engagement, propaganda and communication campaigns, and transparency initiatives. Those ACAs with greater success in establishing a distinguishable reputation in public perceptions through such efforts tend to be endowed with greater de facto independence. Even if these ACAs lack similar financial and human resources of the ICAC, operate in countries with a weak rule of law, and face significant hostilities from the government, their independence can be empowered by their unique institutional prestige.

The Indonesian Corruption Eradication Commission (KPK) was established in a low-governance environment and enjoys a much higher degree of public trust and support than other Indonesian law enforcement agencies (Schütte, Reference Schütte2012). The KPK is modeled after the ICAC, with its own modifications in terms of organizational structure and enforcement power. Since the KPK started its operations in 2004, there has been steady perceived improvement in Indonesia’s anti-corruption outcomes. Footnote 25 Local public opinion polls suggest that citizens are much more satisfied with the performance of, and have stronger beliefs in the integrity of, the KPK than other Indonesian law enforcement agencies, including the Attorney General’s Office, the National Police, and the judiciary (Schütte, Reference Schütte2012). Following the ICAC’s style of publicity initiatives, the KPK invested time, attention, and resources into forging partnerships and alliances with the civil society and developing a good reputation with the media. As a result, public support provided strong backup for the KPK to survive attacks from corrupt actors and political interests that want to weaken the agency. Notably, when Indonesia’s anti-corruption commissioners were imprisoned on criminal charges, most charges were dropped after public outcry. Citizen protests also pressured lawmakers to back off from curtailing the commission’s powers and the Indonesian president to protect its function, against an unreliable judiciary that eventually sided with the KPK in lawsuits aimed at crippling the agency (Kuris, Reference Kuris2012 d, Reference Kuris2012c).

ACAs in Latvia and Lithuania are similarly modeled after the ICAC. Their different outcomes in sustaining institutional independence against external interference can be explained in part by their relative success in public engagement (Batory, Reference Batory2012; Butkevičienė et al., Reference Butkevičienė, Vaidelytė, Morkevičius and Graycar2020). In Latvia, the Corruption Prevention and Combating Bureau (KNAB) has been commended for its effective pursuits of public and private actors perpetrating corruption at the highest levels of government (Schöberlein and Jenkins, Reference Schöberlein and Jenkins2020). The third director of KNAB, Aleksejs Loskutovs, emphasized that ‘[t]he main goal for me was to achieve public credibility. Publicity for an anticorruption agency is one of the bases for survival’ (Kuris, Reference Kuris2012a: 11). The KNAB adopted a strategy of active public communication of its achievements as well as corruption problems in Latvia. Its efforts of earning public trust paid off and the agency amassed significant public goodwill – by 2009, KNAB was named as one of the most trusted public institutions in Lativa (Batory, Reference Batory2012; Schöberlein and Jenkins, Reference Schöberlein and Jenkins2020). As a result, when the Prime Minister attempted to remove KNAB’s director and when Latvia’s legislature attempted to interfere with KNAB investigations of political corruption, citizens and independent media sources rallied to KNAB’s defense. The public support insulated the agency from disruptions and protected it from political and legal retaliations by the ruling government (Kuris, Reference Kuris2012b; Schöberlein and Jenkins, Reference Schöberlein and Jenkins2020; Batory, Reference Batory2012). It should be noted that when the government’s support was boosted by years of economic growth leading up to 2007 and other favorable news, the Prime Minister, Aigars Kalvītis, gained an upper hand against the KNAB and initiated a series of aggressive actions against the director. When the 2008 financial crisis hit, the Latvian government’s unpopular austerity measures turned public sentiments against the corrupt oligarchs, which in turn helped the embattled KNAB assume public prominence and lead a wave of anti-corruption reform (Kuris, Reference Kuris2012b).

In the case of Lithuania, its Special Investigative Service (STT) enjoyed access to professional technical, human, and intelligence resources and other organizational support (World Bank, 2020). However, its approach to community engagement is less effective, and its work is undermined by unreliable partners in the police, judiciary, or government. Often perceived as ruthless and secretive, the STT struggled with public relations. Therefore, although it won public acclaim for arresting and charging several high-profile defendants and has accrued impressive performance records, it failed to maintain its credibility and public trust when faced with legal attacks (Kuris, Reference Kuris2015b, Reference Kuris2014). Just before Lithuania’s 2004 elections, the STT launched surprise raids and investigations against powerful ministers, legislators, and political leaders who then pushed back against the law enforcement. Unlike its peers in Indonesia and Latvia, the STT had no strong media and civil society allies to spur public support. The STT’s director, Valentinas Junokas, resigned under pressure, and public cynicism against the agency’s assertive strategies also did not help its cases in court. Realizing the insufficiency in the STT’s approaches, the new director changed course and pivoted toward an approach that emphasized communication, education, and media campaigns to gradually change public mindsets and perceptions of the agency (Kuris, Reference Kuris2012a). The more community-based approach is a step forward in modeling after the ICAC and is expected to boot its institutional trust (Butkevičienė et al., Reference Butkevičienė, Vaidelytė, Morkevičius and Graycar2020).

These cases suggest that political support from the executive branch or the de jure institutional guarantees of independence can be neither necessary nor sufficient for ACAs’ abilities to withstand external influences. Even if the Indonesian KPK enjoyed the support of the Indonesian President, Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, such support did not prevent the agency’s commissioners from being arrested by the police on flimsy charges when the agency took on high-profile politicians. Eventually, it was significant pressures from the resultant public outcry and protests that helped reinstate the commissioners and preserve the integrity of the institution. In comparison, Lithuania’s STT did not invest into building pubic goodwill and had to rely on high-level political support. However, its political partners, whether they be the Ministry of the Interior, the law enforcement, or even the Prime Minister, turned out to be unreliable. After the President Rolandas Paksas, who had been supporting STT’s anti-corruption work, was impeached by the Parliament, the director of STT resigned under pressure shortly afterward.

Conclusion

In this paper, we examine the determinants of institutional independence for anti-corruption agencies, a type of fourth branch institution playing important quasi-judicial roles. We argue that a lack of citizen support for the dominant political regime provides opportunities for ACAs to establish institutional independence against external interference. More favorable public assessment of the ACA, relative to that of the government, will empower the ACA if it can take advantage of such differential public support. Therefore, it is important for ACAs to appear distinctively responsive and sensitive to public sentiments, which differentiates the institution from the ruling regime. Under such conditions, potential threats posed by an unpopular regime to an ACA’s independence may actually contribute to the protection of the ACA’s independence.

Leveraging the case of Hong Kong, we examine the sources of power for a model ACA that has maintained significant popular support and operational independence against external interference. The ICAC, an institutional legacy of the colonial era that inherited a distinguished reputation, has continued to promote an image of responsiveness and effectiveness and enjoyed a highly regarded political status in public perceptions. The ICAC is strategically conscientious of public sentiments and conducts enforcement, communication, and propaganda campaigns to build and maintain citizen perceptions of its effectiveness in building a clean society. Due to such successful public engagement, citizens motivated by the agency’s effectiveness will lend support to its independent functions. When the public hold unfavorable views of the dominant regime, they will be more committed to the continuing independence of ICAC operations. This particular case of ACA empowerment has important analytical value because citizen support as a source of institutional independence is tested against growing threats of adverse external influences, i.e., those from an authoritarian sovereign.

The empirical evidence shows that the public have developed distinctively positive attitudes toward the agency and its anti-corruption efforts. Notably, anti-corruption investigations conducted by the ICAC are more responsive to public sentiments than the prosecutions and convictions of corruption cases, which are legal proceedings outside of the ICAC’s jurisdiction. The descriptive evidence also suggests that differential public support toward the ICAC vis-á-vis the government is a crucial factor: the agency’s enforcement is more active under a relatively less popular ruling regime. Regression analysis using individual-level survey data further demonstrates that the relative popularity of the ICAC versus the dominant political regime shapes the agency’s independence. Citizens balance competing considerations regarding how to maintain a checks and balances system: constraining the ICAC’s discretionary power is desirable only when the government is well regarded; the ICAC’s overreach and abuse of power are more acceptable when the government lacks integrity. Importantly, citizens’ tolerance of the ICAC’s excessive power and discretion suggests a high degree of independence accorded to the institution, considering that Hong Kongers have grown increasingly more sensitive to unrestrained executive power since 1997.

Our study contributes to the growing empirical literature on the determinants of ACAs’ success. While conventional studies emphasize the structural features of ACAs and the personal characteristics of the enforcement officials and political leaders in charge (Li et al., Reference Li, Lien, Wu and Zhao2017; Gans-Morse et al., Reference Gans-Morse, Borges, Makarin, Mannah-Blankson, Nickow and Zhang2018), we suggest that an agency’s sensitivity to and capitalization of public opinion is an overlooked mechanism of sustaining institutional independence. While ACAs are expected to be independent from any outside influence, winning over the hearts and minds of the people and responding to pubic sentiments can be a strategy of institutional self-empowerment in a hostile political environment. Overall, our findings enrich the judicial politics scholarship by reaffirming ‘the centrality of public attitudes’ toward quasi-judicial bodies in explaining their stability and change (Caldeira and Gibson, Reference Caldeira and Gibson1992), specifically regarding the ‘guarantor institutions.’

The case of Hong Kong also entails policy implications for weakly institutionalized countries in general. The ICAC’s experience is not simply a case of success. Its strategy to survive the post-1997 era under authoritarian influence is informative for designing institutional mechanisms resistant to jeopardizing forces. For example, the ICAC and Lithuania’s STT similarly face an authoritarian turn in domestic politics that makes traditional political support unreliable and renders their de jure institutional independence more vulnerable to external interference. What led to the divergent outcomes in the two cases was two ACAs’ different abilities of attracting and capitalizing on differential public support, such as the use of public communications, civil society outreach to build partnerships, and strategic responses to high-publicity corruption incidents, which helps overcome political subversion and pushback against institutional independence.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773923000231.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Communications Department of the Independent Commission for Corruption of Hong Kong for sharing the original public opinion survey data. For valuable feedback on previous versions of the project, we would like to thank Sivaram Cheruvu, Chu Jonathan, Zach Elkins, Ting Gong, Junyan Jiang, Tianguang Meng, Steve Monroe, Steve Oliver, Mao Suzuki, and participants of the Public Law Panel of the Junior Law and Politics Research Community.