The Mental Health National Service Framework (NSF) states that primary care groups (PCGs) should work with primary care teams and specialist services to agree protocols for common mental health problems. The Primary Care Protocols for Common Mental Illnesses developed in Croydon were circulated by the Department of Health to all regional offices, as an example of good practice, and 20 health authorities and primary care organisations have requested final electronic versions to adapt for local use. The protocol dealing with eating disorders has been adapted by the Royal College of Psychiatrists Eating Disorders Special Interest Group and appears on the College's website. This paper describes how all the protocols were developed and how they can be accessed.

Background

The NSF set seven standards of care. Standard 2 states that:

-

“Any service user who contacts their primary care team with a common mental health problem should

-

- have their mental health needs identified and assessed

-

- be offered effective treatments, including referral to

-

While recognising that the majority of mental health care will remain within primary care, the NSF states that PCGs should work with primary care teams and specialist services to agree protocols for the assessment and management of common mental health problems. The target date for implementation was April 2001.

Guidelines and protocols

Guidelines have become very popular over the past 15 years and there are now even guidelines for guidelines (Reference Cluzeau, Little JOHNS and GrimshawCluzeau et al, 1997; Reference FederFeder, 1998). Primary care teams have been inundated with them. Hibble et al (Reference Hibble, Kanka and Pencheon1998) found 855 different guidelines (a pile 68 cm high weighing 38 kg) after visiting just 22 practices in the Cambridge and Huntington Health Authority.

The terms guideline, protocol, standard, algorithm and patient care plan are often used together and sometimes interchangeably (Reference DukeDuke, 1993).

Clinical guidelines have been defined as:

“systematically developed statements to assist practitioners and patients make decisions about appropriate health care for specific clinical circumstances” (Reference Field and LohrField & Lohr, 1992)

The term clinical protocol has been defined as:

“precise and detailed plans for the study of a medical or biomedical problem and/or plans for the regime of therapy” (Reference DukeDuke, 1993)

The most useful definition of a protocol, in the context of the development of the Croydon primary care protocols, proved to be:

“Negotiated agreements amongst providers and agencies about how care for a certain condition, series of conditions or population, might be delivered. They are guidelines adapted to fit local circumstances.” (Reference TomsonTomson, 2001)

The common mental health problems identified in the NSF are depression, postnatal depression, eating disorders, anxiety disorders, schizophrenia, alcohol dependence and drug dependence. A protocol is also required for those who require psychological therapies.

The Croydon situation

Croydon is a London borough with a population of 340 000. Until April 2002, there were three PCGs in Croydon and a single health authority. Relationships between the PCGs and the public health department of the health authority were excellent and it was agreed that the protocol development should be led by a Specialist Registrar in Public Health Medicine with a background in general practice.

The process was aided by the existence of a Mental Health Development Group (where general practitioner mental health leads, chief executives of the PCGs, public health specialists, mental health commissioners and representatives of the Croydon specialist mental health services met regularly), and a multi-agency Joint Planning Team (JPT) that included voluntary sector and user group representations. The majority of specialist provision for adult mental health in Croydon is provided by the South West London and Maudsley NHS Trust (SLAM). Several of the Croydon consultants are recognised national experts and SLAM produces prescribing guidelines that are widely acclaimed (Reference TaylorSouth London and Maudsley NHS Trust, 2001).

Method

Literature and internet searches and networking were undertaken to identify evidence-based guidelines in use elsewhere. Close links were made with the PCG general practitioner mental health leads, PCG pharmacists, the Maudsley medicine information centre, specialist clinicians (one lead psychiatrist/psychologist for each protocol) and managers within SLAM to investigate how current services functioned and what should be included in the protocols. It rapidly became obvious that, even within the National Health Service, there were many different types of clinicians and organisations involved with providing care for people with common mental health problems.

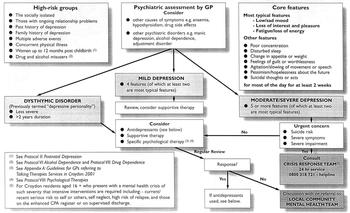

The PCG general practitioner mental health leads firmly believed that, to be useful in primary care, each protocol should be no longer than two sides of A4 and should contain a flowchart (similar to a 1997 depression guideline that had been produced locally). Inclusion of detailed references was felt to be inappropriate.

The protocols were to be introduced as part of the clinical governance programme within each PCG, and drafts and progress were discussed within this structure. For agreement to be reached, consultation was vital. This occurred through personal contact with many individuals and an iterative process of drafting and redrafting, rather than via a steering group. Early drafts were circulated to those who had contributed ideas, and amendments were made. Subsequently there was wider consultation, including a well-attended multi-agency, multi-disciplinary meeting in one PCG that incorporated focus group work - allowing clinicians within primary care the opportunity to influence development. Similar meetings occurred in the other two PCGs at different stages of the development process, so that clinicians in all three PCGs became aware of the protocols during their development and were able to contribute.

Finally, after a further wide consultation, the protocols were submitted to the Pan Croydon Clinical Governance and Education (PCCGE) steering group for endorsement, and discussion concerning implementation. The protocols and supporting material were put on the Croydon Health Authority's intranet site (to which all Croydon general practitioners have access) on 31 March 2001. The project took 10 months to complete.

Implementation

A launch meeting was arranged in each PCG. These took the form of a brief presentation on the development of the protocols, explanation of the supporting material and demonstration of electronic access. The PCG general practitioner mental health leads played a significant role in these launch meetings, which also provided the opportunity for primary care clinicians to hear about new specialist care developments and to meet clinicians from the specialist service. The crisis response service (new 24 h service) and the drug and alcohol service (new primary care liaison worker) gave presentations. Printed copies were widely distributed within primary care, the specialist service and other agencies. In addition, punched copies were produced for inclusion in the Croydon primary care clinical governance folders, which contain agreed standards for other conditions. Acetates and electronic versions were provided for consultant psychiatrists who requested them for training purposes, and copies were distributed at a JPT meeting and a local mental health day attended by voluntary groups and users.

During development, the protocols attracted the attention of the Department of Health and draft copies were circulated to all regional offices as an example of good practice. A grant from the Department of Health has covered the printed costs and enabled sufficient numbers to allow distribution at seven different conferences. To date, 20 Health Authorities/Primary Care Organisations have requested modifiable electronic versions to adapt for local use. Colour pdf versions of the protocols are available via the Croydon Primary Care Trust (PCT) website www.croydon.nhs.uk/reports/primarycareprot_/commonmentalill/commonmentalill.pdf) and a limited number of hard copies are available from The Public Health Directorate, Croydon Primary Care Trust, Knollys House, 17 Addiscombe Rd, Croydon, Surrey CR0 6SR. An example of the protocol for depression is shown in Fig. 1. The eating disorder protocol has been adapted by the Royal College of Psychiatrists Eating Disorders Special Interest Group and appears on the College's website (www.rcpsych.ac.uk/college/sig/eatdis.htm#pcp).

Fig. 1 Protocol 1: depression - identification and referral

Is practice changing?

There was no formal assessment of what practice was like before the protocols were introduced, so evaluation is not straightforward. However, during development some general practitioners found draft versions sufficiently useful themselves to merit copying them for medical students and general practice registrars. The protocols were introduced as part of the clinical governance programme within primary care, so individual practices should be prepared to audit their use. In addition, evaluation has begun within the PCGs (including visits to some practices) and there is enthusiasm for Croydon-wide evaluation and revision as appropriate.

Acknowledgements

Thanks are due to the very many people who contributed in many different ways to the development of the protocols.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.