INTRODUCTION

Radical right populist (RRP) parties are often described as Männerparteien. They are predominantly led by and represented by men (Mudde Reference Mudde2007). Gender gaps are also evident among the RRP parties’ electorate, with women making up a smaller share of party supporters compared with men (e.g., Coffé Reference Coffé and Rydgren2018; Reference Coffé2019; Givens Reference Givens2004; Immerzeel, Coffé, and van der Lippe Reference Immerzeel, Coffé and van der Lippe2015; Spierings and Zaslove Reference Spierings and Zaslove2015). Although male-dominated, RRP parties are increasingly including women as MPs and leaders. For example, the Swiss People’s Party (SVP) sent 11 women (17% of their parliamentary party) to the National Council in 2015, nearly doubling the number of women elected in 2011. High-profile women also lead (or have recently led) RRP parties, including Marine Le Pen in France, Siv Jensen and Sylvi Listhaug in Norway, and Alice Weidel in Germany.

Given that RRP parties have traditionally held very conservative views on the role of women in society, what accounts for this increase in women’s representation? In this paper, we examine the conditions under which RRP parties elect more women MPs. We argue that a driving force behind increasing numbers of women among the party’s parliamentary delegation stems from the RRP parties’ substantial gender imbalance among voters. We advance a new theory of strategic descriptive representation that brings together insights from the fields of gender, voting behavior, and party politics: parties use an increase in women’s descriptive representation (the number of women in office) as a tool to appeal to a broader set of voters, in addition to or as a substitute for standard programmatic tools of party competition. In the case of RRP parties, we argue that electorally struggling parties with a deficit in women’s support seek to elect more women MPs as a way to improve their support among women voters. Increasing the number of female faces becomes a tactic—one that is perhaps less costly than programmatic change—to court an undertapped constituency.

To test this argument, we develop the most comprehensive dataset to date on women as MPs, women as party leaders, and gender differences in voter support across Europe and over time. Our pan-European dataset includes 187 parties in 30 countries from 1985 to 2018. We find that, among RRP parties, the interaction of a male-dominated electorate and electoral threat predicts higher proportions of women MPs. Analyses including all parties across the party system reveal that this interaction is largely unique to RRP parties.

The results of this paper expand our understanding of the RRP party family. Challenging the existing narrative of these parties as male-focused, our findings show that women are seen as a possible resource to an RRP party. But unlike the claim that RRP parties use women’s representation as a “standardization” tactic to better comply with broader norms of gender diversity (Erzeel and Rashkova Reference Erzeel and Rashkova2017; Mayer Reference Mayer2013)—a prediction which is more consistent with electorally successful partiesFootnote 1 —we argue and find that RRP parties are most likely to use the strategy when they are both losing votes and lacking women voters. In making this claim, this paper reconciles the current discussion of RRP parties as Männerparteien with the evidence that women voters can be an important, albeit overlooked, constituency for them, as was the case with the German Nazi Party (NSDAP; Boak Reference Boak1989). Given that RRP parties have become central political actors across Europe and have been included in national governments, their embrace or rejection of women representatives has important ramifications for gender representation at the elite and mass levels.

This paper also advances our knowledge about party competition in general. While the literature is dominated by a discussion of programmatic tactics for vote or seat maximization, our work emphasizes the importance of descriptive representation as a political and electoral tool. Such strategy allows the party to attract new voters without necessarily altering core issue positions and therefore, alienating existing voters. Building on the insights of previous work on women’s representation in parties (e.g., Erzeel and Rashkova Reference Erzeel and Rashkova2017; Kittilson Reference Kittilson2006; Valdini Reference Valdini2012), our paper is the first to identify gender gaps in party support and overall electoral success as key variables in explaining women’s representation. We examine how RRP parties employ the tactic of strategic descriptive representation as a means of gaining women voters, but the paper and its theory have implications for all types of parties facing electoral declines and searching for untapped pockets of future voters.

We start by reviewing the existing literature on why women MPs are elected. We then propose the theory of strategic descriptive representation and spell out its implications for RRP parties’ increase in women representatives. Third, we describe our new comprehensive time-series, cross-sectional dataset on women MPs, party leaders, and voter-base gender gaps. Next, we discuss the results of our analyses for women’s representation across RRP parties, along with robustness checks. Fifth, we introduce two case studies to assess the plausibility of our strategic argument and illustrate its effect on candidate selection decisions. Sixth, we explore to what extent our argument of strategic descriptive representation translates to other party families in Europe. We conclude by discussing the implications of our findings and future extensions of the work.

WHY DO PARTIES ELECT WOMEN? IDEOLOGY, ORGANIZATION, AND WOMEN ACTIVISTS

Women have made substantial gains in descriptive representation over the last few decades. But they are still underrepresented in most countries, and significant cross-national differences in women’s representation exist. Country-level institutional factors, such as proportional representation electoral rules with high district magnitude (Luhiste Reference Luhiste2015; Norris Reference Norris and Rose2000; O’Brien and Rickne Reference O’Brien and Rickne2016; Paxton Reference Paxton1997; Valdini Reference Valdini2012), and gender quotas (Dahlerup and Freidenvall Reference Dahlerup and Freidenvall2005; Krook Reference Krook2009; Murray Reference Murray2004; Paxton and Hughes Reference Paxton and Hughes2015; Tripp and Kang Reference Tripp and Kang2008) facilitate higher shares of women in parliaments. Yet significant variation in women’s descriptive representation exists within countries, across parties, which cannot be explained by these factors.

Figure 1 demonstrates this puzzle of variation in women’s representation across party families in Europe from 1980 to 2018. Green/New Left parties maintain the highest share of women over this span of time. Despite an ebb and flow, both Social Democratic and Conservative parties make gains over time and end up following on the heels of the Green/New Left party family. In contrast, the RRP party family has among the lowest percentage of women MPs of all party families during this period. Yet, since the mid-2000s, women have made strides in the RRP party family. By the end of the 2010s, RRP parties have the same proportion of women MPs as Christian Democratic parties. As we discuss later, there is also variation within the RRP party family, with some parties becoming more gender inclusive over time than others.

Figure 1. Proportion of Women MPs in Different Party Families, Europe 1980–2018, Loess smoothing

To explain the proportion of women among a party’s MPs, party-level analyses have suggested three sets of factors: party ideology, party organizational structures, and women’s activism within the party. First, party decisions on gender equality within party ranks may reflect the party’s larger ideology about the role of women in society. Early research on party-level variation in descriptive representation often found leftist parties to be more likely to adopt voluntary gender quotas and to have more women among their slate of MPs than centrist or rightist parties (Caul Reference Caul1999; Kittilson Reference Kittilson2006; Kunovich and Paxton Reference Kunovich and Paxton2005; Lovenduski and Norris Reference Lovenduski and Norris1993). The emergence of “new left” (Green and radical left) parties radically altered women’s representation on the left, with research finding that these parties in particular promote gender equality as a core part of their ideology (Keith and Verge Reference Keith and Verge2018).

However, in recent years, the relationship between leftist parties and gender inclusion appears more tenuous. Conservative parties have often highlighted “women’s interests” although not necessarily from a feminist perspective (Celis and Childs Reference Celis and Childs2012). O’Brien (Reference O’Brien2018) finds that references to gender are equally salient for Christian Democratic and Social Democratic parties, albeit in different ways. And parties such as the British Conservative and German Christian Democratic parties have promoted women MPs under certain conditions (Childs Reference Childs2008; Childs and Webb Reference Childs and Webb2012; Wiliarty Reference Wiliarty2010). Figure 1 shows that Conservative parties in Europe now boast the third-highest share of women in the party on average, ahead of the more centrist Liberal and Christian Democratic party families.

Second, studies have indicated a relationship between party organizational structures and women’s descriptive representation, but the results are mixed. Some comparative research suggests party centralization enables women’s gains among MPs (Aldrich Reference Aldrich2020; Kittilson Reference Kittilson2006). However, there is also evidence of the opposite relationship. Kenney (Reference Murray2013), for example, finds decentralized structures to be more conducive to women’s election. Similarly, Fortin-Rittenberger and Rittenberger (Reference Fortin-Rittenberger and Rittenberger2015) find that more inclusive selectorates, not centralized processes, lead to more women MEP candidates in European parliamentary elections.

Third, women’s activism within the party is an important force for change. In particular, women among the party leadership and women’s party organizations play a positive role in pressing for more women candidates (Caul Reference Caul1999; Childs and Kittilson Reference Childs and Kittilson2016; Kunovich and Paxton Reference Kunovich and Paxton2005; although see Tremblay and Pelletier Reference Tremblay and Pelletier2001).

Although the existing literature has been successful in accounting for general trends in women’s representation and differences between parties, important puzzles remain. One such puzzle is the underrepresentation of women in the RRP party family. As starkly demonstrated by Figure 1, the RRP party family stands out for its lowest level of women MP representation for much of the 1980–2018 period. Though this could be dismissed as consistent with their ideology and reputation as Männerparteien, the party family has seen a significant increase in their share of women MPs in the 2000s, across plurality and proportional systems alike, and despite maintaining their extremist authoritarian ideology.

A second puzzle is highlighted by Figure 2: there is significant variation within the RRP party family, with some parties—Italy’s Northern League, France’s National Front/National Rally, and the Danish People’s Party, for example—increasing their share of women in the party substantially over time, whereas others do not. This variation also cannot be accounted for by the country- or party-level explanations dominant in the literature. For example, while national gender quotas have become more popular across Europe over time, the systematic opposition of RRP parties to quotas reduces their explanatory force for differences between parties.Footnote 2 Although there is some variety in the ideology of RRP parties, they all share the broad ideological elements of nativism (anti-immigrant and nationalism), authoritarianism, and populism (Mudde Reference Mudde2007) considered anathema to gender equality. Finally, although there has been an increase in the number of women party leaders among the RRP party group, their singular role in explaining an increase in women MPs does not seem straightforward, as RRP parties with women leaders both have a comparatively high proportion of women MPs (e.g., the National Rally in France) and low proportion of women MPs (e.g., Alternative for Germany [AfD] in Germany).Footnote 3

Figure 2. Proportion of Women MPs in Radical Right Populist Parties, Europe 1980–2018, Loess Smoothing

A THEORY OF STRATEGIC DESCRIPTIVE REPRESENTATION

We argue that a fourth party-level factor—the gender composition of vote share—is critical to understanding the trends in women’s political party representation over time and across and within party families. Building on previous research suggesting a role of vote and seat losses for party feminization (Campbell Reference Campbell2016; Childs and Webb Reference Childs and Webb2012; Eagle and Lovenduski Reference Eagle and Lovenduski1998; O’Brien Reference O’Brien2015) and drawing on the insights of previous work on strategic women’s representation (e.g., Erzeel and Rashkova Reference Erzeel and Rashkova2017; Kittilson Reference Kittilson2006; Valdini Reference Valdini2012), we develop and empirically test a new theory of the conditions under which parties engage in strategic descriptive representation.

Putting the factors of electoral loss and the often-overlooked gender differences in voter support at its core, we posit that parties embrace women as MPs when they need to increase their vote share and women are currently underrepresented among their voters. An increase in women’s descriptive representation is thus seen as a tactic for broadening a party’s electorate in order to attract previously untapped women voters and remedy the party’s vote stagnation or decline. As theorized by Pitkin (Reference Pitkin1967), descriptive representation taps one dimension of political representation, calibrating the degree to which a representative body mirrors the composition of the society it serves. Our theory of strategic descriptive representation is less focused on gauging the quality of representation and more aligned with the ways women’s presence can be deployed as a tool in a party’s kit to bolster their electoral trajectory.

Our strategic argument begins with the recognition that political parties are rational actors, seeking to maximize their electoral support. It follows that parties and their elite will engage in tactics to improve upon or solidify their electoral success. Although the party competition literature tends to focus on programmatic movement for maximizing voter support (e.g., Adams et al. Reference Adams, Clark, Ezrow and Glasgow2004; Adams and Somer-Topcu Reference Adams and Somer-Topcu2009; Downs Reference Downs1957; Laver and Hunt Reference Laver and Hunt1992), descriptive representation can also be an effective method for attracting and mobilizing voters. There is evidence of this relationship with respect to race and ethnicity (e.g., Bobo and Gilliam Reference Bobo and Gilliam1990; Dancygier Reference Dancygier2017; Tate Reference Tate2003), and also gender. Women are more likely to support women candidates and to support parties with higher percentages of women representatives (Banducci and Karp Reference Banducci and Karp2000; Box-Steffensmeier et al. Reference Box-Steffensmeier, Kimball, Meinke and Tate2003; Goodyear-Grant Reference Goodyear-Grant, Anderson and Stephenson2010; Penney, Tolley, and Goodyear-Grant Reference Penney, Tolle and Goodyear-Grant2016; Plutzer and Zipp Reference Plutzer and Zipp1996). A recent meta-analysis of candidate choice survey experiments shows that women tend to prefer women candidates more than men do, although both respond to women candidates positively (Schwarz and Coppock Reference Schwarz and Coppock2021). Multiple mechanisms behind this relationship have been identified: some voters might be motivated primarily by the visible similarities between them and party representatives, others might be motivated by the belief that women representatives will bring desirable policy changes to parliament and party organizations, including a greater focus on shared women’s issues and interests (Greene and O’Brien Reference Greene and O’Brien2016; Kittilson Reference Kittilson2008; Reference Kittilson2011; Tremblay Reference Tremblay1998; Xydias Reference Xydias2007). For the sake of our argument, it suffices to recognize that gender affinity is a feasible part of the explanation for voters’ preferences. Even if gender affinity effects are not large, the logic of the argument stands so long as party elites believe that women are more likely to vote for women.

Beyond recognizing this voting pattern of women supporting women, there is evidence that parties employ strategic descriptive representation. For example, in times of heightened electoral uncertainty, parties are also more likely to adopt gender quota laws to increase their support among women voters (Murray, Krook, and Opello Reference Murray, Krook and Katherine2012; Weeks Reference Weeks2018). Party competition for women’s votes also motivated tactical decisions by political elites in the United States in the era of the suffrage movement (Teele Reference Teele2018). Valdini (Reference Valdini2019), specifically, discusses how established (largely men) party gatekeepers strategically calculate that having more women representatives can benefit parties’ less-than-positive images and gain them support from women voters in upcoming elections.

Evidence from case studies reveals some of the dynamics behind decisions to promote more women for office. One strategy is for women in party leadership to use polling data about deficits in support from women to push to elect more women MPs. This tactic was particularly effective in the British Labour Party in the 1990s and has found some effectiveness in elections since then for both the Labour and Conservative Parties (Childs and Webb Reference Childs and Webb2012; Eagle and Lovenduski Reference Eagle and Lovenduski1998). Campbell (Reference Campbell2016, 594) sums up this dynamic stating, “critical actors are important but they are most successful when they are able to claim that they can bring women voters with them.”

Although parties have multiple methods for increasing their electoral support, altering the gender composition of their parliamentary delegations is a relatively low-cost—if not necessarily costless—tactic. Adding more women as MPs is a highly visible and symbolic step, and the information is easily accessible even to uninformed voters. In addition, we suggest that it could be less risky than other constituency-expanding appeals, such as moderating stances on core issues or diversifying their issue offerings. Research suggests that voters in advanced democracies do not discriminate against women candidates—even radical right populist voters. For example, in a recent survey experiment, Saha and Weeks (Reference Saha and Weeks2020) show that United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP) voters are no less likely to support ambitious women than men candidates. Previous research also finds that if right-wing party leadership perceives the issue of diversity in representation as important for electoral support, they may be willing to risk losing some local activist support (Sobolewska Reference Sobolewska2013). Increasing the number of women MPs is a tactic that can be pursued, at least initially, without requiring any coterminous programmatic shifts—dilution of the party message—that may drive away existing voters. To paraphrase Donno and Kreft (Reference Donno and Kreft2019, 726), expanding women’s representation in the party “represents a ‘quieter’ strategy of preemptive cooptation.”

In sum then, we expect parties’ electoral fortunes and gender gap to drive their decision to increase the number of women MPs. Figure 3 presents a visual summary of the main argument, using a table of scenarios and predictions for each situation. The left column considers incentives when the party attracts a low male/female (M/F) voter ratio (the voters are not men-dominated). It shows that parties have little reason to change their level of women’s descriptive representation when they already do well among women voters (whether they face an electoral threat or not). Indeed, those women-dominated parties losing votes might actually have an incentive to increase their percentage of men MPs to attract underrepresented men voters. The right column considers those parties with men-dominated electorates (high M/F voter ratio), and here, opposite hypotheses emerge depending on the party’s electoral vulnerability. In the bottom-right cell, when a men-dominated party faces an electoral threat, the party ought to seek new electorates—specifically, the untapped women’s vote. Strategic inclusion (Hypothesis 1a) is the logical tactic. In the top-right cell, when a men-dominated party is doing well, we predict it will double down on the exclusion of women in the party (“strategic exclusion,” Hypothesis 1b). In this scenario, success may be derived (or perceived to derive) from a party’s men MPs. Women are not needed to gain votes.

Figure 3. Party Incentives for Strategic Descriptive Representation

WOMEN AND MÄNNERPARTEIEN

Although the presented strategy of increasing women’s descriptive representation might be broadly accessible to a variety of individual parties, RRP parties stand out as being particularly well positioned to take advantage of such a strategy. First, there is consistent evidence of the persistence of a gender gap among radical right populist voters. Women are significantly less likely to support RRP parties than men (Coffé Reference Coffé and Rydgren2018; Reference Coffé2019; Gidengil et al. Reference Gidengil, Hennigar, Blais and Nevitte2005; Givens Reference Givens2004; Harteveld et al. Reference Harteveld, Van Der Brug, Dahlberg and Andrej Kokkonen2015; Immerzeel, Coffé, and van der Lippe Reference Immerzeel, Coffé and van der Lippe2015; Mudde Reference Mudde2007; Spierings and Zaslove Reference Spierings and Zaslove2015). Indeed, RRP parties stand out as having the largest overrepresentation of men voters among all party families.

Second, accompanying this voter-base gender gap has been a gender imbalance among party MPs and leaders. RRP parties have typically been led by men, with women traditionally underrepresented as party leaders. The imbalance extends to parliamentary representatives where, as Figure 1 revealed, RRP parties have consistently elected among the lowest percentage of women MPs of any party family in Europe. Although there have recently been some significant developments in women’s roles in these parties, as the current leadership of Sylvi Listhaug of the Norwegian Progress Party, Marine Le Pen of the French National Rally and Alice Weidel of the German AfD show, these women are noticeable because they are exceptions to the male-dominated leadership pattern. An implication of this condition is that strategic descriptive representation would not be an effective tool for those parties that already elect significant shares of women, such as Green parties and many Social Democratic parties. Indeed, Social Democratic parties may have already used this strategy effectively in previous decades. It is likely that there is some threshold of women’s descriptive representation, beyond which parties are less likely to envision additional strategic gains from adding women.Footnote 4

Third, most RRP parties’ organizations tend to be highly centralized. Strategic descriptive representation is only likely to be effective in party organizations where elites can successfully control candidate nomination and placement on lists. This rules out parties with highly decentralized candidate selection procedures and parties that have democratized their procedures in recent years by implementing primaries (Hazan and Rahat Reference Hazan and Rahat2010). Although we lack comprehensive cross-national, time-series data on candidate selection procedures across parties and countries, decentralized candidate selection is widespread across other party families. For example, in Belgium the majority of parties use decentralized candidate procedures with the exception of the Flemish Interest and the French-speaking Greens (Weeks Reference Weeks2018).

The described conditions suggest (a) that RRP party leaders have the ability to increase shares of women candidates in winnable positions, (b) that their parties could benefit electorally from attracting more women voters, and (c) that the expansion of women MPs might prove a useful means to achieve this goal. This latter point is further reinforced by the finding that women voters might be more reluctant than men to vote for extremist parties based on perceived negative social cues (Harteveld et al. Reference Harteveld, Van Der Brug, Dahlberg and Andrej Kokkonen2015). The presence of women representatives in RRP parties may help to reduce such concerns about RRP parties’ outsider status.

Indeed, other strategic options to appeal to women voters on the basis of gender would not prove as effective for RRP parties. Research by Harteveld and Ivarsflaten (Reference Harteveld and Ivarsflaten2018) reveals few gender differences in policy preference over immigration, meaning that the RRP reinforcing their current anti-immigration position is unlikely to yield additional women voters (see also Mayer Reference Mayer2013). Finally, despite the possible claim that an outreach to women voters might not be perceived to be credible by a RRP party given the conservative ideas about gender equality of many RRP parties (De Lange and Mügge Reference De Lange and Mügge2015; Mayer Reference Mayer2015; Mudde Reference Mudde and Kaltwasser2015), various RRP parties have modernized their views on gender equality issues. In particular, efforts have been made by some voices on the radical right to link existing anti-Islam platforms to liberal feminist stances—a trend referred to as femonationalism (Farris Reference Farris2017). Specifically, some northern European RRP parties have cloaked their campaign against Islamic practices toward women (e.g., forced marriage, honor killings, headscarves) as a call for greater gender equality and tolerance of LGBTI rights (Akkerman Reference Akkerman2015; De Lange and Mügge Reference De Lange and Mügge2015; Mayer Reference Mayer2013; Mudde and Kaltwasser Reference Mudde and Kaltwasser2015). This may appeal to more feminist-minded women (and men) voters, although Celis and Childs (Reference Celis and Childs2020) point out that RRP parties are using “gender equality as a weapon against an alleged “Islamization” of Europe” (97).

In summary, given the gender gap in votes and representation, women are an obvious electoral target for RRP parties to broaden their electorate. We expect male-dominated RRP parties that are losing votes or have hit an electoral plateau to have strong incentives to elect more women MPs (H1a). By contrast, electorally successful male-dominated RRP parties have little incentive to alter their vote-getting men-focused approach and should elect fewer women (H1b).

DATA AND METHODS

To test our hypotheses, we created the most comprehensive dataset to date on women as MPs, women as party leaders, and gender differences in voter support across Europe and over time (Weeks et al. Reference Weeks, Meguid, Kittilson and Coffé2022).Footnote 5 The data used in our models include 187 parties in 30 Western and Eastern European countries from 1985 to 2018.Footnote 6 Of these, 22 RRP parties are included from 19 countries.Footnote 7

Dependent Variable

Our dependent variable is the proportion of women MPs at the party level following a given election. The coding of this variable is based on verified information from parliamentary websites and electoral commissions, supplemented with data from the European Journal of Political Research “Political Data Yearbook” and secondary sources, when necessary.Footnote 8 Ideally we would also analyze time-series cross-national candidate data, but this is not available. Examining the percentage of women in the parliamentary party allows us to capture party efforts to get women elected by placing them in winnable seats. Because evidence suggests that parties not committed to equal gender representation often place women candidates in uncompetitive districts or uncompetitive spots on party lists (Jones Reference Jones2004; Tavits Reference Tavits2010), it is likely that we are, if anything, underestimating the full effect of the explanatory factors on women’s representation as candidates and thus, biasing our results against finding support for our theory.

Explanatory Variables

We are interested in the effect of RRP parties’ electoral performance and their ratio of men to women voters (the M/F voter ratio) on the descriptive representation of women MPs. Few studies systematically examine gender differences in support for RRP parties, even fewer investigate how these differences have changed over time, and none examines how these gaps might condition party behavior. We measure overall electoral fortunes as a party’s change in vote share since the last election lagged.Footnote 9

Gender differences in voter support are measured as the ratio of the percentage of men respondents who report voting for a party to the percentage of women respondents who report voting for the same party. These percentages are derived from the Comparative Study of Electoral Systems (CSES), and where or when not available, we rely on the European Election Study (EES) and the European Social Survey (ESS). We prefer CSES data because the survey asks about respondents’ electoral behavior in the then-current national parliamentary election context. Although it is retrospective (“who did you vote for”), it is also the most temporally proximate measure available (and the M/F voter ratio measure we use is then lagged). If data from both EES and ESS are available for the same party, we take the value from the survey conducted closest to the election year. In all surveys, respondents identify the party they voted for (excluding “don’t know,” “don’t remember,” and spoiled ballots) in the last election. For countries with mixed member systems, the results for the party list survey questions are used. For pure proportional representation systems, we use the party list question, while the candidate party question is used for candidate-based elections. We applied poststratification demographic weights for all data.

Figure 4 displays gender differences in voting behavior by party families between 1985 and 2018 across Europe. The figure presents the M/F voter ratio, with 1 indicating an equal proportion of men and women voters, a score higher than 1 revealing a higher proportion of men than women voters, and a score lower than 1 indicating a lower proportion of men than women voters.

Figure 4. Male/Female Ratio in Voting Behavior for Different Party Families, Europe 1985–2018, Loess Smoothing

Note: M/F voter ratio values above 5 (highly male-dominated electorate) are set to 5 for the sake of this plot only to facilitate greater legibility. A plot without this restriction can be found in the Appendix (Figure A1).

Figure 4 reveals the variation in gender gaps in voting across party families and time. The RRP party family stands out with the largest overrepresentation of men among voters of all parties (the RRP party mean is 1.9, or nearly 2 men voters for every woman voter). As a party family, RRP parties have experienced the largest deficit in women’s votes. Since 1980, that gap narrowed before increasing again around 2010. In recent years, the gender gap in RRP parties is again falling, but the party family remains the most male-dominated of any party family. Figure A2 in the Appendix presents the gender gaps in voting for the RRP parties included in our analyses over time.

Based on the existing work on women’s representation, we also include a number of variables as controls. To capture the electoral climate in which women candidates are being elected, we include a measure of the electoral system (Proportional Representation and Modified Proportional Representation, where Majoritarian/SMD is the reference category), a continuous measure for district magnitude, and dichotomous variable measuring whether a country has national-level gender quota laws or not.Footnote 10 We also include the lagged percentage of women MPs in the country’s parliament as an indicator of country-level context for women’s representation and to test for the idea that RRP parties’ behavior is being driven by the pressure to meet the gender diversity norms of “standard” parties (Erzeel and Rashkova Reference Erzeel and Rashkova2017; Mayer Reference Mayer2013). To account for the role of party characteristics in the election of women MPs, we gathered and coded a dichotomous variable capturing whether the RRP party had a woman leader at the time of the last election or not; this data extended Greene and O’Brien’s (Reference Greene and O’Brien2016) data on women party leaders by 10 countries and 77 parties to a total of 30 countries and 187 parties. In light of O’Brien’s (Reference O’Brien2015) idea that a party’s governmental status may modify its incentives to elect more women, we include a dichotomous variable coded 1 if the party was in the governing cabinet following the previous election and 0 if not.

Some previous research suggests that party centralization may benefit women’s election (Aldrich Reference Aldrich2020; Kittilson Reference Kittilson2006). Our research design, focusing on RRP parties, largely controls for this factor because most RRP parties have highly centralized organizations, often built around strong authoritarian and charismatic leaders (Mudde Reference Mudde2007). Similarly, our focus on RRP parties controls for party ideology. Lastly, we also include a time trend and a variable distinguishing Western and Eastern European countries to account for any broad cultural and political disparities across the regions. Table A2 in the Appendix presents summary statistics.

MULTILEVEL ANALYSIS

We estimate multilevel random intercept models (using R version 4.1.2.) to test the effects of electoral success and gender gap on the proportion of women MPs in RRP parties. Unlike ordinary least squares models, these models allow us to account for the nested nature of the data, with parties nested within countries (Gellman and Hill Reference Gellman and Hill2007). Table 1 presents multiple models: Model 1 includes only direct effects of our two focus variables, and Model 2 includes an interaction term between electoral success and M/F voter ratio, to investigate our expectations that the proportion of women MPs will be higher among those RRP parties facing both an electoral loss and a large gender gap. Subsequent models add controls to the interaction: Model 3 includes a time trend, Model 4 adds party-level covariates, and Model 5 adds national-level covariates. The different models allow us to test whether our main findings hold with the inclusion of various party and context-control variables.

Table 1. Determinants of Women’s Representation in Radical Right Populist Parties

Note: Results are based on multilevel analyses with random intercepts for the country and party levels of the data. The dependent variable is the percentage of women among the RRP parties’ MPs in national, lower-chamber legislature. Standard errors in parentheses; *** p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01, *p < 0.05.

As can be seen from Models 2–5 in Table 1, we find that the interaction of lagged gender gap in voter support and vote change is statistically significant and in the expected negative direction across all models: when RRP parties are struggling electorally (negative vote change) and have disproportionately more men voters, they have a higher percentage of women MPs compared with parties not facing both conditions.

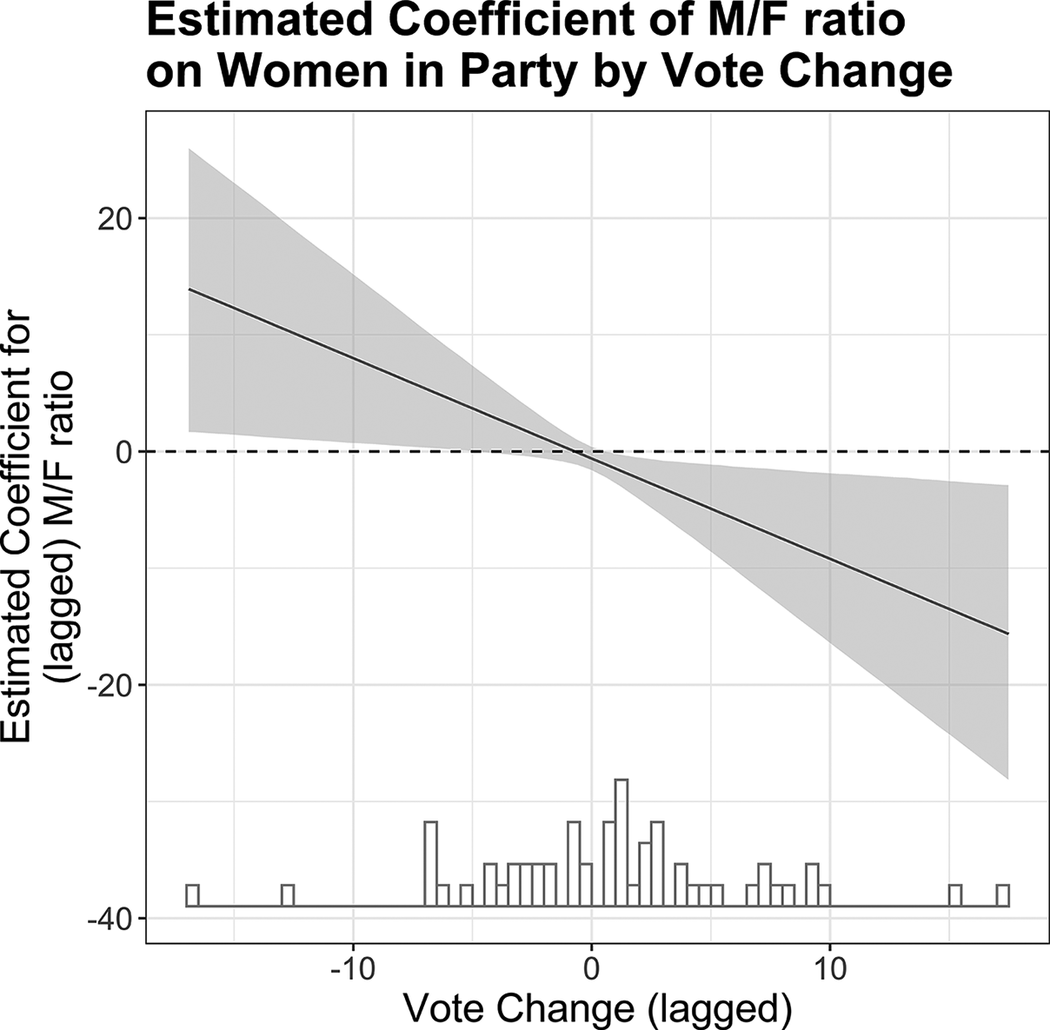

To more easily interpret the findings of this interactive story, we plot the marginal effects of M/F voter ratio on the percentage of women MPs as it varies by level of electoral success in Figure 5.Footnote 11 Following the logic of strategic descriptive representation, we find support for Hypothesis 1a: the effect of the M/F voter ratio on the proportion of women in the party is positive and significant when the party faces electoral losses (vote change is negative). This positive significant effect emerges for levels of vote change of -3 percentage points and lower. At the same time, when RRPs are doing well (vote change is positive and greater than or equal to +1), we see the opposite: the effect of the M/F voter ratio is negative and significant. Consistent with Hypothesis 1b of strategic exclusion, when RRP parties are gaining votes despite having disproportionately more men voters, they have a lower percentage of women MPs.

Figure 5. Marginal Effects of Male/Female Voter Ratio on Share of Women in Radical Right Populist Parties as a Function of Party Vote Change

Note: Estimated coefficients are based on regression results shown in Table 1, Model 5, and 95% confidence intervals are shown, along with a rug plot along the x-axis.

In order to translate our results into meaningful quantities of interest (King, Tomz, and Wittenberg Reference King, Tomz and Wittenberg2000), we calculate the conditional predicted values of the dependent variable—percentage of women MPs—for parties that are gaining versus losing votes, across different M/F voter ratios. For example, when a RRP party has a men-dominated electorate (M/F Voter Ratio of 2), the predicted value of women in the party is 14% if the party is gaining votes (when Vote Change is +5) but 20% if losing votes (when Vote Change is -5). As expected, we see the opposite when a RRP party is women-dominated (M/F Voter Ratio of 0.5): the predicted value of women in the party is 21% if the party is gaining votes (when Vote Change is +5) and 14% if losing votes (when Vote Change is -5).

In summary, the evidence suggests that, for RRP parties, the conditions of electoral change and a men-dominated electorate lead the party to respond with strategic increases in women’s descriptive representation in times of threat and an abandonment of (or at least no increase in) women parliamentarians in times of electoral success. These findings paint the picture of an RRP party family searching for new electoral strategies when old tactics fail, and doubling down on existing tactics when proven effective.

The results from Table 1 also indicate the continued importance of some structural variables identified by past work. We find support for the claim that parties have higher levels of women representatives when there is a national norm for having a large proportion of women in the parliament. We also find that legislated gender quotas are borderline significant (p = 0.06) in the expected positive direction. Consistent with the results of the party-level analyses of O’Brien (Reference O’Brien2018), we do not find that the measures of institutional permissiveness—district magnitude and proportional representation—have a significant effect on women MPs in RRP parties, nor do women leaders increase women in RRP parliamentary parties. Moreover, the addition of these variables does not alter the explanatory strength of the strategic descriptive representation factors.

ROBUSTNESS CHECKS

To ensure that our findings are not the result of model misspecification, we also estimate models that use ordinary least squares. The main findings are robust to these alternative specifications (see Appendix Table A3). The marginal effects plots (Figure 5 and Figure A3) reveal an outlier for M/F voter ratio, which is most likely due to survey sampling issues (niche parties, like RRP parties, often having few supporters to begin with). To check that extreme values in M/F voter ratio due to survey sampling issues are not biasing our results, we rerun the analysis excluding M/F voter ratio values over 10; the results continue to hold (see Appendix Table A4, Model 1). One concern is that the results could be an artifact of good electoral scores, rather than strategic incentives of parties. For example, if a RRP party was doing poorly, it might decide to reach out to the median voter; if this tactic is successful in attracting more votes and gaining more seats, then the election of more women who are placed further down the list could be unintended. We note that if this were the case, we would expect to see more women elected when the RRP party does well overall, but we do not see this. Table 1 Model 1 shows no evidence of an effect of electoral change on the share of women in RRP parties on its own. An additional analysis of the most inclusive model (Table 1 Model 5), but with no interaction term (see Table A5 in the Appendix), finds the same result: being electorally vulnerable alone does not increase levels of women MPs within RRP parties.

Another alternative explanation is that RRP parties might not experience electoral threat, but be motivated to increase gender diversity to combat their outsider reputation. If this is true, we should see RRP parties (perhaps especially those with highly male-dominated electorates, more likely to be seen as extremist) increase women’s representation in the party independently of electoral threat. We find no evidence of this in either Table 1 Model 1 or Table A5 in the Appendix. The gender gap in voting is only significant when combined with electoral change, in line with our theory.

CASE STUDIES: ARE RRP PARTIES STRATEGIC?

The quantitative results are consistent with our strategic descriptive representation theory and run counter to alternative hypotheses. To increase our confidence in the strategic nature of our finding of increased women MPs under conditions of electoral threat and a gender gap in voting, we consider the parties’ motivations. In this section, we turn to illustrative case studies. Although space limitations prevent us from providing the comprehensive qualitative analysis necessary to fully investigate the causal mechanisms driving party strategies, the brief descriptions we present help to assess the plausibility of and strategic logic behind our observed statistical relationships (Lieberman Reference Lieberman2005). These illustrative cases also allow us to highlight different presentations of the candidate selection and placement decisions behind the election of more women.

Following Seawright and Gerring (Reference Seawright and Gerring2008) and Lieberman (Reference Lieberman2005) for regression models yielding results consistent with theory expectations, we examine two “typical” cases that are well-predicted by the statistical models—the SVP in Switzerland in 2015 and the Party of Freedom (PVV) in the Netherlands in 2017.Footnote 12 In both cases, the alternative hypotheses investigated here are not supported; neither country had a nationally legislated gender quota implemented before the election in question (or at all); both parties were lacking women party leaders; and, based on the socialization argument about gender equality norms (e.g., Erzeel and Rashkova Reference Erzeel and Rashkova2017), any increases in women MPs should have followed electoral success. Rather, the key conditions behind the strategic descriptive representation theory—a gender gap in voting and electoral threat—are present, with the PVV facing a more dire situation than its Swiss counterpart. Relying on primary and secondary resources, including news articles and candidate list position data, we see evidence in both cases of RRP party campaigns using women MP candidates—either in greater numbers or higher list positions—as a strategy to explicitly target women voters.

Switzerland 2015: “Swiss Girls Vote SVP”

The SVP has long been considered a Männerpartei, mainly represented and elected by men. And yet, in 2015, following an electoral loss in 2011 and faced with a significant gender gap (M/F ratio of 1.3), the SVP engaged in deliberate tactics to appeal to this undertapped female constituency. Under the centralized party organization led by Toni Brunner (Buhlmann, Zumbach, and Gerber Reference Buhlmann, Zumbach and Gerber2016; Mazzoleni Reference Mazzoleni, Pallaver and Wagemann2012), the SVP ran more women (82 candidates, 10 more than in the previous 2011 election) and built an advertising campaign around these women candidates. As shown in Figure 6, the Party indeed “decorated its campaign with women” (translation, “What do You Guys Have?” 2015). The message behind “Swiss Girls Vote JSVP [the Youth wing of the SVP]” was simple: (young) women should vote for the SVP because its candidates looked like them. As noted in Figure 6, gone was the SVP of “only old, shaggy men.”

Figure 6. Swiss Girls Vote JSVP

In addition to increasing the number of women candidates, the SVP put them in winnable positions (Gilardi Reference Gilardi2015b). In 2015, the share of SVP women candidates (19%) compared with elected women MPs (17%) was nearly 1 to 1 for the first time; it had ranged from 1.7 to 3.5 candidates per elected women MP in the five previous elections.Footnote 13 Like this national campaign, regional SVP campaigns also revealed deliberate strategies to attract women voters. In the canton of Solothurne, for example, the SVP nominated an all-women’s list and founded a women’s section one month before the election. Local party president Silvio Jeker claimed that the SVP had, “a good basis to now gain a foothold with women,” while then local party vice president Christine Rütti said in a speech to party members, “we need more middle-class women.”Footnote 14 As a result, the women’s share of elected SVP MPs rose by six percentage points from the previous election, reaching 17% of the delegation. With this election, the SVP also closed their gender gap in voter support. In fact, analysts credited the SVP’s vote share gains in 2015 explicitly to an increase in women voters (Foppa Reference Foppa2015).

The Netherlands 2017: “Geert’s Angels”

The Dutch PVV Party also exhibited an election strategy targeting women voters with women’s faces in 2017. Geert Wilders has been head of the PVV since he founded the party in 2006 and maintains strong control over candidate selection as leader (De Lange and Art Reference De Lange and Art2011). He has a reputation as being calculating and media-savvy—and one of the “most strategic” politicians out there.Footnote 15 In 2017, the conditions were ripe for the party to pursue an inclusive form of strategic descriptive representation. The PVV had lost votes in the previous 2012 parliamentary elections (10.1% compared with 15.5% in 2010), and they faced a high gender gap (M/F voter ratio of 1.58) in their electoral support. In line with our theory, in 2017, the PVV presented a party list top-heavy with women MP candidates: the prized second and third spots on the list were both occupied by women. Wilders announced the party list with a photo shoot of the top three candidates: himself flanked by the two women, Fleur Agema and Vicky Maijer. The news made the front page of the largest Dutch daily, De Telegraaf, with the headline, “Geert’s Angels” (Figure 7). Wilders himself acknowledged that the placement of the women was part of a tactic to draw a broader electorate to the PVV. In an interview with De Telegraaf, he said, “The supporters of the PVV range from low to highly educated, from man to woman, from native to immigrant.”Footnote 16

Figure 7. Geert’s Angels: Cover of De Telegraaf, January 6, 2017

In contrast to the Swiss SVP’s strategic inclusion tactic, the PVV did not increase the share of women candidates on the list: in 2012, 28% of the candidates were women, compared with 26% in 2017. But more women were placed higher on the list in 2017, and two of the top three candidates were women.Footnote 17 The party’s strategy was also markedly different from that pursued by the PVV five years earlier when the PVV did not emphasize women in their campaign or media coverage.Footnote 18 This de-emphasis is further evidence of their 2012 strategic exclusion tactic consistent with our theory’s predictions for an electorally strong (vote gain = 10% from 2006 to 2010), male-dominated (M/F = 1.25) party. As a result of the greater prioritization of women candidates on the party list in 2017, the share of women MPs increased from 20% in 2012 to 30%. The 2017 inclusive strategy also seems to have worked in terms of attracting women: in 2017, 45% of the party’s voters were women, versus 40% in 2012, and the PVV’s vote share increased by about 3 percentage points.

DO ALL PARTIES EXHIBIT STRATEGIC DESCRIPTIVE REPRESENTATION OF WOMEN?

Having identified strategic descriptive representation as a tool employed by RRP parties, we might ask to what extent RRP parties are unique in employing strategic descriptive representation. To test the bounds of the generalizability of our argument, we replicate our models of women MPs using the full dataset of all European parties. We consider the effect of our key variables both with all parties pooled (Table 2) and within each party family individually (Table 3). The results suggest that the strategy of gender-based descriptive representation is not universally employed by all parties.Footnote 19 As shown in Table 2, the coefficient of the interaction between lagged vote change and M/F voter ratio is in the expected direction but does not reach statistical significance in any model. This insignificant relationship is further confirmed by the marginal effects plot presented in Appendix Figure A4.

Table 2. Determinants of Women’s Representation in All Party Families

Note: Results are based on multilevel analyses with random intercepts for the country and party levels of the data. Dependent variable is the percentage of women among a party’s MPs in the national, lower-chamber legislature. Standard errors in parentheses; *** p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01, *p < 0.05.

Table 3. Determinants of Women’s Representation by Party Family

Note: Dependent variable is the percentage of women among the party’s MPs in the national, lower-chamber legislature. Standard errors in parentheses; *** p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01, *p < 0.05.

However, more nuanced conclusions emerge if we disaggregate the analyses by party family. In Table 3, we replicate the most complete model of women MPs for each party separately. Although the interaction between M/F ratio and vote change is not statistically significant for most families, the interaction has a negative and significant coefficient for the Christian Democratic party family, suggesting a similar conditional effect of electoral success and gender gap in voter support on their percentage of women MPs as among the RRP parties; this conclusion is reinforced by the marginal effect plot Figure A5 in the Appendix. However, further consideration of the values of their M/F ratio variable indicates that their dilemma is not about how to recruit women voters. Because the Christian Democratic parties face no relative paucity in women voters (they have an average M/F ratio below 1, placing them in the left half of Figure 3), the interaction effect means that they take an opposite tack when electorally vulnerable. Consistent with the need to recruit undertapped constituencies, they pursue a higher percentage of men MPs. The Christian Democratic approach may well then be one of the strategic descriptive representation of men.

CONCLUSION

RRP parties have seen increasing success across postindustrial democracies over the past 40 years. While the field now knows much about the characteristics of these parties (e.g., Arzheimer Reference Arzheimer and Rydgren2018; Kitschelt Reference Kitschelt1995; Meguid Reference Meguid2005; Reference Meguid2008; Mudde Reference Mudde2007; Rovny Reference Rovny2013) and causes and consequences of their electoral support and governmental presence (e.g., Abou-Chadi Reference Abou-Chadi2016; Bischof and Wagner Reference Bischof and Wagner2019; Kitschelt Reference Kitschelt1995; Wagner and Meyer Reference Wagner and Meyer2017), much less is known about why there has been an increase in women MPs among some of these traditionally men-dominated parties.

We build on the existing literature on party strategic behavior to answer this question by identifying the conditions under which RRP parties are most likely to use strategic descriptive representation and by testing our argument with novel cross-national data. We argue that electorally weak political parties fundamentally seek out untapped constituencies. For weak parties lacking women voters, bolstering women’s descriptive representation becomes a relatively low-cost tool for broadening their electorate and increasing their vote share. Based on data from 22 European RRP parties in 19 countries from 1985 to 2018 and qualitative evidence of party tactics of the Swiss SVP and Dutch PVV, our analyses find support for this strategic story. In other words, women’s representation in RRP parties increased neither because parties’ decisions reflect broader societal change nor because improving the quality of political representation is a normative good. Instead, parties made a strategic calculation that increasing women is electorally useful.

Our paper makes several empirical and theoretical contributions. First, the paper introduces a new dataset, expanding our knowledge of women’s roles as party leaders, MPs, and voters. These data allow us to understand the changing characteristics of RRP parties, both in contrast to other party families and in relation to their RRP colleagues. As highlighted in this study, we now have time-series data to support the case-based findings of the substantial gender gaps in RRP party votes. With this information, we are able to not only trace gender differences in voter support for RRP parties over time, but we can advance the work on gender gaps by examining how they condition party behavior.

Second, we develop a comprehensive theory of the conditions under which parties engage in strategic descriptive representation. We suggest that RRP parties seeking to tap into a new female constituency are not limited to engaging in costly programmatic shifts along their dominant issue axis or in the addition of a new issue. Of course, the new women MPs may bring their own policy ideas and priorities, eventually diversifying the party platform, but this effect is secondary and delayed in time, and may not be as visible to existing voters as a purely programmatic strategy to attract different voter bases.

Our study has potential implications beyond Männerparteien. First, the utility of strategic descriptive representation is not limited to this party family. In theory, any party that needs to broaden its electoral support, while simultaneously suffering from a deficit in women’s votes could look to promote more women for parliamentary office. Our extension of the analyses to all European parties reveals that Christian Democratic parties similarly see gender as a tool for bolstering their electoral fortunes, in their case, using men to counter their women-dominated electorate. For other party families, many of the key conditions for strategic descriptive representation by gender appear to be absent. For instance, Green and Social Democratic parties have relatively high proportions of women voters and MPs already. In such parties with more gender egalitarian ideology and high representation of women voters and MPs, there is less room to maneuver in attracting more women voters and electing more women. Additional qualitative research, including interviews with party leaders, MPs, and candidates, would help to further confirm the reasons why some party families are more likely to use strategic descriptive representation than others. Second, our findings raise another question for future studies: are the women elected as part of strategic descriptive representation qualitatively different from those elected under other conditions? In a party’s effort to attract women voters while at the same time reducing men’s opposition to such a strategy, perhaps these women candidates are more likely to toe the party line, be members of the party leadership dynasty, or young and attractive, as the SVP campaign materials (Figure 6) suggest (Bernhard Reference Bernhard2018).

While the current study focuses on gender, we might expect to see strategic descriptive representation used to target other untapped groups in the electorate. Parties that struggle to gain support from younger voters may choose to elect more young people as their MPs. Similarly, in line with the rise of homonationalist appeals by RRP parties linking the protection of LGBTI citizens to campaigns against Muslim immigrants (Spierings Reference Spierings2021), we might see parties promote LGBTI candidates to attract similarly identifying voters. While there are some notable examples of LGBTI RRP leaders (e.g., Alice Weidel and Pim Fortuyn), future research should systematically investigate the extent to which strategic descriptive representation is leveraged by RRP and other parties to appeal to a variety of underrepresented groups beyond women.

In addition to broadening the investigation of the limits of a descriptive representation strategy, this paper also raises questions about other dimensions of strategic representation tactics. Future research could add strategic substantive representation (representing the interests or preferences of certain groups) to the study of strategic representation. Just as increasing visible images of gender equality may lead more women to support a party, a similar vote gain to a male-dominated electorally threatened RRP party could result from its shift in emphasis toward issues that are attractive to women. Questions about the relative effectiveness of descriptive versus programmatic gender equality among RRP parties as well as the lasting implications of each for the quality of women’s representation are a subject for future work.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055422000107.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Research documentation and data that support the findings of this study are openly available at the American Political Science Review Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/SG55BJ.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the editors and anonymous reviewers of the APSR, Rachel Bernhard, Louise Davidson-Schmich, Russell Dalton, Fabio Ellger, Gretchen Helmke, Alice Kang, Mona Morgan-Collins, and Soledad Prillaman, as well as participants at the “Causes and Consequences of Party Positions” panel at the 2020 APSA Meeting, the UCL Political Science Seminar, and the “Party Competition in the Electoral Cycle” workshop for their helpful comments on previous versions of this paper. We thank YeonKyung Jeong and Sami Gul for their excellent research assistance.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no ethical issues or conflicts of interest in this research.

ETHICAL STANDARDS

The authors affirm this research did not involve human subjects.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.