1. Introduction

This study focused on the intricate relationship between corporate social responsibility (CSR) and risk management in the context of the fashion industry. The link between CSR and risk management is significant and multifaceted (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Lee and Kang2021). CSR refers to a company's commitment to conducting business in an ethical and socially responsible manner, taking into account its impact on society and the environment. On the contrary, risk management involves identifying, assessing, and mitigating potential risks that could affect a company's operations, reputation, and financial stability (Narasimhan & Talluri, Reference Narasimhan and Talluri2009). CSR and risk management are strongly intertwined because a company's social and environmental performance can have direct implications for its risk profile (Harjoto & Laksmana, Reference Harjoto and Laksmana2018; Landi et al., Reference Landi, Iandolo, Renzi and Rey2022).

By integrating CSR principles into their risk management strategies, companies can effectively address risks related to social (Cunha et al., Reference Cunha, Ceryno and Leiras2019; Lu et al., Reference Lu, Liu and Falkenberg2022) and environmental factors (Martínez & Poveda, Reference Martínez and Poveda2022). Issues such as poor labor practices, supply chain disruptions, or environmental non-compliance can have severe consequences such as reputational damage, legal complications, and operational disruptions (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Lee and Kang2021). Through the incorporation of CSR into risk management, companies gain the ability to proactively identify and manage these risks (Karwowski & Raulinajtys-Grzybek, Reference Karwowski and Raulinajtys-Grzybek2021). By placing importance on responsible practices such as maintaining fair labor conditions, promoting sustainable sourcing, and minimizing environmental impacts, companies can bolster their reputation, foster stronger relationships with stakeholders, and mitigate potential risks (Chakraborty et al., Reference Chakraborty, Gao and Sheikh2019; Haywood, Reference Haywood2022). This comprehensive approach not only aligns ethical responsibilities with business objectives but also positions companies to adapt to evolving regulations, meet consumer expectations, and address societal demands (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Hung and Lee2018). Consequently, companies can reduce the likelihood of incurring costly penalties and maintain a competitive edge in the market (Landi et al, Reference Landi, Iandolo, Renzi and Rey2022).

Companies that demonstrate a commitment to CSR are often better equipped to adapt to changing regulations, consumer expectations, and societal demands, reducing the likelihood of costly penalties or loss of market share (Ouyang et al., Reference Ouyang, Lv and Liu2023). In light of the intricate dynamics shaping sustainability and the inherent uncertainty surrounding future scenarios (Moallemi et al., Reference Moallemi, Gao, Eker and Bryan2022), a negative event that occurs within the supply chain at the social level has implications for business at the operational level, potentially threatening the business continuity of processes, and subsequently generating financial risk (Landi et al., Reference Landi, Iandolo, Renzi and Rey2022). This holds true even when considering an initial negative event that originates at the operational level and impacts the social sphere and then the financial sphere. It is therefore crucial to establish the connection between safeguarding social responsibility principles and the risk management approach, with the primary goal of addressing the need to protect the business and simultaneously safeguarding corporate image and profitability to ensure process continuity (Dhar et al., Reference Dhar, Sarkar and Ayittey2022).

This factor becomes particularly important within the fashion sector because, characterized by highly fragmented supply chains composed of numerous small suppliers, while at the same time, it is necessary to maintain a high brand image communicated to the end customer (Wijaya & Paramita, Reference Wijaya and Paramita2021). In this context, sustainable supply chain management assumes particular importance as it is closely associated with the concept of risk management (Chan et al., Reference Chan, Wei, Guo and Leung2020; Rafi-Ul-Shan et al., Reference Rafi-Ul-Shan, Grant, Perry and Ahmed2018). In particular, current concerns arise from the fact that the outsourcing of activities, while allowing fashion brands to acquire flexibility in order to better adapt to market demands and timelines, can also be risky due to the large number of small companies that make up the production chain and need to be kept under control (Colucci et al., Reference Colucci, Tuan and Visentin2020). Although this outsourcing practice preserves craftsmanship, and the different fragmented production phases along the chain are responsible for representing the value associated with the authenticity of the brands they represent, these elements expose companies to significant risks, both operational and related to business continuity, reputation, and the brand itself (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Lee and Kang2021). Moreover, they require extensive control, mapping, and risk analysis throughout the chain, which entail high costs if individually addressed for each brand (Zioło et al., Reference Zioło, Bąk and Spoz2023).

However, the fashion industry faces challenges in implementing sustainability practices due to the lack of comprehensive legal regulations. Unlike other sectors, there is no overarching legislation specifically addressing sustainability requirements and standards in fashion. This absence of binding regulations leads to inconsistency and varying levels of commitment across the industry (Kazancoglu et al., Reference Kazancoglu, Sagnak, Kumar Mangla and Kazancoglu2021). Collaboration, voluntary standards, and transparency are crucial to driving sustainable practices and ensuring accountability (Jestratijevic et al., Reference Jestratijevic, Uanhoro and Creighton2022). Efforts by industry organizations, non-governmental organizations, and governmental bodies are being made to establish guidelines, but comprehensive legal regulations remain elusive (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Napier, Runfola and Cavusgil2020a, Reference Liu, Ndubisi, Liu and Barrane2020b). Therefore, the fashion industry must find a balance between profitability and ethical and environmental considerations without robust legal requirements (Kimbro, et al., Reference Kimbro, Abraham, Lambe and Jones2018; Zioło et al., Reference Zioło, Bąk and Spoz2023). The lack of legal frameworks in the fashion industry created more discretion in defining and implementing sustainable practices (Sehnem et al., Reference Sehnem, Troiani, Lara, Guerreiro Crizel, Carvalho and Rodrigues2024). Although some brands have voluntarily adopted sustainability initiatives, the absence of binding regulations leaves room for inconsistency and varying levels of commitment across the industry (Nayak et al., Reference Nayak, Akbari and Far2019). As a result, there is a need for increased industry collaboration, voluntary standards, and transparency to drive sustainable practices and ensure accountability (Caldarelli et al., Reference Caldarelli, Zardini and Rossignoli2021).

Research focusing on the interconnections between CSR and risk management provides valuable insights into how organizations can effectively navigate and leverage these interrelated domains (e.g. da Silva et al., Reference da Silva, Ramos, Alexander and Jabbour2020; Kim et al., Reference Kim, Lee and Kang2021; Krysiak, Reference Krysiak2009). By understanding the reciprocal relationship between CSR and risk management, organizations can develop holistic strategies that address both social and financial goals (Cohen, Reference Cohen2015; Landi et al., Reference Landi, Iandolo, Renzi and Rey2022). This study contributes to the knowledge base of best practices, frameworks, and tools that enable organizations to integrate CSR considerations into their risk management processes, fostering more sustainable and resilient business practices (Dornelles et al., Reference Dornelles, Boyd, Nunes, Asquith, Boonstra, Delabre, Denney, Grimm, Jentsch, Nicholas and Schröter2020).

Examining the interconnections between CSR and risk management sheds light on the critical role that social factors play in shaping an organization's risk landscape. By recognizing and proactively managing social risks, organizations can build resilience, protect their reputation, and create shared value. The research in this area advances our understanding of the synergies between CSR and risk management, enabling organizations to navigate societal challenges and contribute to a more sustainable future for the fashion industry. This study contributes to address critical gaps in the existing literature by providing empirical evidence on the effectiveness of sustainability-based strategies in managing supply chain risks and sustaining long-term business success in the fashion sector (Cunha et al., Reference Cunha, Ceryno and Leiras2019). Currently, there is a notable lack of empirical cases exploring multisectoral sustainability transformation (Salomaa & Juhola, Reference Salomaa and Juhola2020), with literature often focusing on describing existing unsustainability rather than articulating transformative processes (Marciniak et al., Reference Marciniak, Urbach, Schneider, Krug, de Bremond, Stafford-Smith, Selomane, Fenn, Chong and Paillard2024). Recent calls for a transformative approach in sustainability science highlight the need for empirical contributions demonstrating the transformation of processes and organizations (Horcea-Milcu et al., Reference Horcea-Milcu, Dorresteijn, Leventon, Stojanovic, Lam, Lang and Zimmermann2024). By filling these gaps, this study will offer practical insights for fashion brands and supply chain practitioners seeking to enhance risk management capabilities while upholding social responsibility principles. Ultimately, it aims to deepen understanding of the complex relationship between social responsibility, risk management, and supply chain management in the fashion sector, advocating for a holistic approach to address contemporary global supply chain challenges (Zioło et al., Reference Zioło, Bąk and Spoz2023).

2. Corporate social responsibility

The field of sustainability science, emerging around the turn of the Millennium (Rockström et al., Reference Rockström, Bai and DeVries2018), sets out to understand the fundamental character of interactions between nature and society (Scown et al., Reference Scown, Craig, Allen, Gunderson, Angeler, Garcia and Garmestani2023; Vogt & Weber, Reference Vogt and Weber2019). Particularly, significant advancements have been made in the literature regarding the multidimensional nature of human well-being and the various ways in which ecosystem services contribute to enhancing different components of human well-being (Masterson et al., Reference Masterson, Vetter, Chaigneau, Daw, Selomane, Hamann, Wong, Mellegård, Cocks and Tengö2019). Moreover, integral to this pursuit is the concept of CSR, defined as the voluntary integration of social concerns by businesses in their commercial operations and their relations with stakeholders (global reporting initiative– ). This definition encompasses the key characteristics that distinguish CSR to a greater extent. A socially responsible company is one that considers not only the economic aspects but also the social impacts that result from its business activities and the formulation of its strategies (Martínez & Poveda, Reference Martínez and Poveda2022; Sodhi & Tang, Reference Sodhi and Tang2018). Specifically, according to the European Commission, there are three key elements of CSR: the voluntary commitment of the company to undertake social responsibility actions, the adoption of the ‘triple bottom line’ approach of Elkington (Reference Elkington1998), which evaluates the company based on economic, environmental, and also social aspects, with a focus on both internal and external stakeholders. Furthermore, the sustainable development goals, adopted by the United Nations in 2015, represent a global commitment to address the most pressing challenges of our time by 2030. These 17 goals encompass a wide range of issues, from eradicating poverty and hunger to promoting health and education, from reducing inequalities to foster justice (Hickmann et al., Reference Hickmann, Biermann, Sénit, Sun, Bexell, Bolton, Bornemann, Censoro, Charles, Coy and Dahlmann2024; Ningrum et al., Reference Ningrum, Malekpour, Raven, Moallemi and Bonar2024). Among these, there are also goals that emphasize social sustainability, such as promoting gender equality, decent work, and inclusive economic growth (Orbons et al., Reference Orbons, van Vuuren, Ambrosio, Kulkarni, Weber, Zapata, Daioglou, Hof and Zimm2024). These goals aim to ensure that no one is left behind in the pursuit of a sustainable future (Randers et al., Reference Randers, Rockström, Stoknes, Goluke, Collste, Cornell and Donges2019). Being socially responsible means not only fully complying with applicable legal obligations but also going beyond them by investing in human capital and stakeholder relationships (Waddock, Reference Waddock2020). The experience gained from investments in responsible technologies (Lahsen, Reference Lahsen2024) and business practices (Merçon et al., Reference Merçon, Vetter, Tengö, Cocks, Balvanera, Rosell and Ayala-Orozco2019) suggests that companies can enhance their competitiveness by surpassing legal requirements. The application of social standards, that go beyond the basic legal obligations (Schulte et al., Reference Schulte, Yowargana, Nielsen, Kraxner and Fuss2024), can have a direct impact on productivity. This opens up a path that allows for managing change and reconciling social development while promoting greater competitiveness (Broccardo et al., Reference Broccardo, Culasso, Dhir and Truant2023).

CSR is becoming the core of strategic management of firms and an essential tool to address the need to consider the economy from a long-term perspective (Carroll, Reference Carroll2021). It becomes an integral part of sustainable development and a fundamental element in pursuing competitiveness goals as a way of doing business (Kuokkanen & Sun, Reference Kuokkanen and Sun2020). CSR practices have undergone a profound evolution because their inception and now go beyond direct benefits, considering social aspects in a broader and multifaceted way during business operations (Ferramosca & Verona, Reference Ferramosca and Verona2020; Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Yang, Wang and Michelson2023). It is worth noting that CSR is becoming fully integrated with strategic management and corporate governance (McManus, Reference McManus2008; Zaman et al., Reference Zaman, Jain, Samara and Jamali2022). This has prompted companies to develop entire organizational and management mechanisms for the control and reporting of socially conscious business policies and practices (Pizzi et al., Reference Pizzi, Rosati and Venturelli2021). In their application, CSR strategies integrate with the overall corporate strategy and largely involve monitoring and ensuring compliance with local and international regulations, and ethical issues; considering the responsibility of their actions’ impacts on all stakeholders, including society, suppliers, representative bodies, employees, governments, and so on, that is, those referred to as stakeholders (Khan & Sukhotu, Reference Khan and Sukhotu2020).

From these contributions, it is understood that CSR must be developed with an ethical and moral component and one linked to business. In today's intense global market competition, it is evident that CSR is sustainable only if it adds value to business success because the ultimate goal of a company remains value creation (Grassmann, Reference Grassmann2021). To achieve this purpose, a company cannot ignore the context in which it operates and the network of relationships that connect it to a large number of individuals, called stakeholders. These relationships influence the way an organization operates, and in turn, they are influenced by its behavior. Therefore, a company's ability to generate sustainable wealth over time, and thus its long-term value, is determined by the relationship it has with critical stakeholders (López-Concepción et al., Reference López-Concepción, Gil-Lacruz and Saz-Gil2022; Perrini, Reference Perrini2006). Consequently, whatever business strategy a company intends to pursue in its long-term development, it must take into account stakeholders, that is, individuals, groups, and suppliers with a legitimate interest in the company's strategy (Pfajfar et al., Reference Pfajfar, Shoham, Małecka and Zalaznik2022). The achievement of an effective sustainability strategy, and in particular social strategy, is strongly linked to the ‘quality of relationships’ that the company establishes with its suppliers, customers, financiers, and institutions, therefore, with what is defined as the ‘external area of the company’, and is not only due to the realization of satisfactory internal processes (Diez & Mele, Reference Diez and Mele2016). In this vision of social integration of companies, CSR must be part of the overall business strategy (Elkington, Reference Elkington1998).

The inclusion of ethical criteria in supply network management and supply chain relationships is the direct result of some phenomena characterizing the current economic environment. Since the late 1970s, there has been a progressive streamlining of corporate structures and an increasing importance of outsourcing to concentrate corporate resources on activities that generate the most value (Miranda & Roldán, Reference Miranda and Roldán2022). This trend has led to a concentration of internal resources on product development and design, logistics and distribution phases of the value chain, marketing, and communication activities. Consequently, low-value-added activities, typically those upstream in the value chain related to production processes, have been outsourced (Luo et al., Reference Luo, Yang, Zhang and Pan2022). In essence, this facilitated the fact that that local events can escalate into global challenges and local contexts are continuously shaped by global dynamics (Rockström et al., Reference Rockström, Bai and DeVries2018). For instance, sustainability regulations in one country can influence corporate policies and practices across the globe (Vogt & Weber, Reference Vogt and Weber2019). Additionally, consumer preferences and cultural trends in one region can rapidly spread and influence markets in other parts of the world, driven by the interconnectedness facilitated by technology and media (Leach et al., Reference Leach, Reyers, Bai, Brondizio, Cook, Díaz, Espindola, Scobie, Stafford-Smith and Subramanian2018; Vithayathil et al., Reference Vithayathil, Dadgar and Osiri2020). This interconnectedness underscores the importance of considering global implications in local decision-making and highlights the need for a comprehensive, ethically informed approach to managing supply chains.

2.1 CSR in the fashion industry

CSR is a critical aspect of the fashion industry, with profound implications for both businesses and society as a whole (e.g. Bubicz et al., Reference Bubicz, Barbosa-Póvoa and Carvalho2021; Govindan et al., Reference Govindan, Shaw and Majumdar2021; Talay et al., Reference Talay, Oxborrow and Brindley2020). In recent years, there has been a growing recognition of the industry's social and ethical responsibilities, prompting a shift toward more sustainable practices (Islam et al., Reference Islam, Perry and Gill2021). The fashion industry, known for its rapid product cycles and trend-driven nature, significantly impacts global economies and cultures. However, it also faces substantial criticism due to its environmental and social implications (Nguyen et al., Reference Nguyen, Le, Ho and Nguyen2021). As one of the largest polluters, the fashion industry contributes to environmental degradation through excessive water usage, chemical pollution, and textile waste. Additionally, the industry's reliance on fast fashion practices often leads to exploitative labor conditions, raising concerns about workers' rights and ethical production standards (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Napier, Runfola and Cavusgil2020a, Reference Liu, Ndubisi, Liu and Barrane2020b).

The importance of CSR in the fashion sector lies in its potential to address issues such as worker exploitation, unsafe working conditions, and social inequality (Zioło et al., Reference Zioło, Bąk and Spoz2023). By prioritizing fair labor practices, ensuring safe and healthy working environments, and promoting diversity and inclusivity, fashion companies can contribute to the well-being and empowerment of their workforce (Essiz & Senyuz, Reference Essiz and Senyuz2024; Kunz et al., Reference Kunz, May and Schmidt2020; Shafqat et al., Reference Shafqat, Ishaq and Ahmed2023; Sinha et al., Reference Sinha, Sharma and Agrawal2022). This, in turn, enhances employee morale, productivity, and loyalty, leading to long-term business success (Han et al., Reference Han, Ariza-Montes, Giorgi and Lee2020). Additionally, CSR helps fashion brands build trust and credibility among consumers who are increasingly conscious of the social and ethical impacts of their purchasing decisions (Kumagai & Nagasawa, Reference Kumagai and Nagasawa2023). By demonstrating a commitment to social responsibility, companies can attract and retain customers who value ethical practices, thereby enhancing brand reputation and fostering customer loyalty (Kong et al., Reference Kong, Witmaier and Ko2021). Moreover, CSR in the fashion industry extends beyond internal practices to encompass supply chain management (Bubicz et al., Reference Bubicz, Barbosa-Póvoa and Carvalho2021). By collaborating with suppliers who adhere to ethical standards, fashion companies can ensure that their entire value chain operates in a socially responsible manner (Alghababsheh & Gallear, Reference Alghababsheh and Gallear2021). This includes responsible sourcing of materials, transparent production processes, and fair treatment of workers throughout the supply chain (Caldarelli et al., Reference Caldarelli, Zardini and Rossignoli2021; Khan et al., Reference Khan, Zkik, Belhadi and Kamble2021). By promoting social sustainability, the fashion industry can contribute to the creation of a more equitable and inclusive society, while also driving positive change in other sectors (Karaosman et al., Reference Karaosman, Perry, Brun and Morales-Alonso2020).

Overall, the importance of social sustainability in the fashion industry cannot be overstated, as it not only aligns with the values and expectations of consumers but also has a profound impact on the well-being of workers, and society as a whole (Ozdamar et al., Reference Ozdamar Ertekin, Atik and Murray2020). The integration of social responsibility into business operations, particularly in relation to exchanges along the entire production chain, improves the performance of the chain as a whole, increasing employee satisfaction, reducing company costs, potentially increasing revenues and economic-financial performance, as well as improving product safety and traceability, resulting in enhanced trust with the final market (Accenture, 2012; Mukendi et al., Reference Mukendi, Davies, Glozer and McDonagh2020; Ye et al., Reference Ye, Kueh, Hou, Liu and Yu2020).

For all these reasons, the CSR of the fashion supply chain is increasingly recognized as a key component of corporate sustainability, both for the benefits and positive outcomes that effective management can bring, and for the problems and risks that can arise (Bubicz et al., Reference Bubicz, Barbosa-Póvoa and Carvalho2021; Cai & Choi, Reference Cai and Choi2020). Managing social impacts and promoting good governance practices throughout the life cycle of goods and services in supply chains are crucial elements for modern business management (Di Vaio et al., Reference Di Vaio, Hassan, D'Amore and Tiscini2022). However, it is important to acknowledge the complexity of this management and the fact that supply chains are subject to constant changes in markets and relationships (International Institute for Sustainable Development, 1992; Zioło et al., Reference Zioło, Bąk and Spoz2023).

Moreover, there has been a significant increase in consumer interest in the social sustainability of fashion products (Vătămănescu et al., Reference Vătămănescu, Dabija, Gazzola, Cegarro-Navarro and Buzzi2021). Today's consumers are increasingly aware of the social and ethical implications of their purchasing decisions, and they seek to align their values with the brands they support (Kong et al., Reference Kong, Witmaier and Ko2021; Sander et al., Reference Sander, Föhl, Walter and Demmer2021). The fashion industry, being one of the most visible and influential sectors, has faced growing scrutiny regarding its social (Elf et al., Reference Elf, Werner and Black2022; Majumdar et al., Reference Majumdar, Garg and Jain2021). Consumers are now demanding greater transparency and accountability from fashion brands, specifically regarding the social conditions under which their products are made (Garcia-Torres et al., Reference Garcia-Torres, Rey-Garcia, Sáenz and Seuring2022; Modi & Zhao, Reference Modi and Zhao2021). They want assurance that workers are treated fairly, with safe working conditions and fair wages (Chan et al., Reference Chan, Wei, Guo and Leung2020). Consumers are also concerned about issues such as child labor, forced labor, and exploitation in the supply chain (Nayak et al., Reference Nayak, Thang, Nguyen, Gaimster, Morris and George2022). As a result, they actively seek out brands that prioritize social sustainability, supporting those that demonstrate a commitment to ethical sourcing, fair trade, and responsible manufacturing practices (Broccardo et al., Reference Broccardo, Culasso, Dhir and Truant2023; Kunz et al., Reference Kunz, May and Schmidt2020). This shift in consumer behavior has prompted fashion companies to reevaluate their strategies and integrate CSR into their core business practices (Karaosman et al., Reference Karaosman, Perry, Brun and Morales-Alonso2020; Osburg et al., Reference Osburg, Davies, Yoganathan and McLeay2021). Brands that successfully address these concerns and communicate their CSR initiatives to consumers are rewarded with increased loyalty, positive brand perception, and a competitive advantage in the market. As consumer demand for socially sustainable fashion continues to grow, companies that embrace and champion these values will be better positioned to thrive in the industry (Kong et al., Reference Kong, Witmaier and Ko2021; Mukendi et al., Reference Mukendi, Davies, Glozer and McDonagh2020).

3. Risk management

The growing emphasis on CSR has paralleled the increasing recognition of the importance of comprehensive risk management in safeguarding organizational success and sustainability (Abdel-Basset & Mohamed, Reference Abdel-Basset and Mohamed2020; Pournader et al., Reference Pournader, Kach and Talluri2020; Settembre-Blundo et al., Reference Settembre-Blundo, González-Sánchez, Medina-Salgado and García-Muiña2021). In particular, risk management is a strategic discipline that involves identifying, assessing, and mitigating potential risks that could impact an organization's objectives (Cunha et al., Reference Cunha, Ceryno and Leiras2019). It is a proactive approach to understanding and addressing uncertainties that may arise in various aspects of business operations (Munir et al., Reference Munir, Jajja, Chatha and Farooq2020). The concept of risk management has evolved over time, driven by the need for organizations to navigate an increasingly complex and unpredictable business environment (Narasimhan & Talluri, Reference Narasimhan and Talluri2009). In the modern era, risk management gained prominence in the 20th century with the emergence of complex financial markets and industrialization. The devastating effects of industrial events, such as the Great Depression and major industrial accidents, highlighted the importance of identifying and mitigating risks to protect the interests of businesses, stakeholders, and society at large (Cohen, Reference Cohen2015; Pournader et al., Reference Pournader, Kach and Talluri2020). Risk management in businesses can be classified into several categories, each addressing different aspects of potential risks. By categorizing risk management into these distinct areas, companies can develop targeted strategies to effectively address and mitigate various types of risks, enhancing their resilience and stability. Operational risk management focuses on identifying and mitigating risks related to the day-to-day operations of a company, such as supply chain disruptions, equipment failures, or human errors (Araz et al., Reference Araz, Choi, Olson and Salman2020). Financial risk management deals with risks associated with financial markets, including currency fluctuations, credit risks, and liquidity issues (So et al., Reference So, Chan and Chu2022). Strategic risk management involves long-term planning and considers risks that could impact the overall direction and objectives of the organization, such as market competition, regulatory changes, and technological advancements (Andersen et al., Reference Andersen, Sax and Giannozzi2022). Compliance risk management ensures that the company adheres to laws, regulations, and internal policies, reducing the risk of legal penalties and reputational damage (Hauser, Reference Hauser2022; Kortana, Reference Kortana2019). In particular, reputational risks pose significant challenges for businesses in today's interconnected and information-driven world. Reputational risk refers to the potential harm or damage to an organization's reputation, brand image, and public perception (Azadegan et al., Reference Azadegan, Syed, Blome and Tajeddini2020; Dhingra & Krishnan, Reference Dhingra and Krishnan2021). It arises from a variety of sources, including unethical behavior, product recalls, sustainability incidents, data breaches, and negative media coverage (Nujen et al., Reference Nujen, Solli-Saether, Mwesiumo and Hammer2021; Stitzlein et al., Reference Stitzlein, Fielke, Waldner and Sanderson2021; Vizcaíno-González et al., Reference Vizcaíno-González, Iglesias-Antelo and Romero-Castro2019). Reputational risks are of vital importance in building a foundation of trust upon which a company's image is shaped and organized (Gaultier-Gaillard & Louisot, Reference Gaultier-Gaillard and Louisot2006; Landi et al., Reference Landi, Iandolo, Renzi and Rey2022). The impact of reputational risks can be far-reaching and long-lasting (Hogarth et al., Reference Hogarth, Hutchinson and Scaife2018). A tarnished reputation can lead to a loss of customer trust, decreased sales, difficulty attracting and retaining talent, strained relationships with stakeholders, and even legal and regulatory consequences (Karwowski & Raulinajtys-Grzybek, Reference Karwowski and Raulinajtys-Grzybek2021; Pérez-Cornejo et al., Reference Pérez-Cornejo, de Quevedo-Puente and Delgado-García2019). In the age of social media and instant communication, news spreads rapidly, amplifying the effects of reputational crises and making reputation management a critical aspect of business strategy (Kong et al., Reference Kong, Witmaier and Ko2021). Companies that fail to proactively manage reputational risks may face severe consequences. Events from exogenous or endogenous sources may occur and negatively influence customers', and more in general stakeholders', perceptions of the company's behavior and performance (Roehrich et al., Reference Roehrich, Grosvold and Hoejmose2014). Organizations need to be vigilant in monitoring their public image, addressing potential issues promptly, and maintaining open lines of communication with stakeholders (Foroudi et al., Reference Foroudi, Nazarian, Ziyadin, Kitchen, Hafeez, Priporas and Pantano2020). Implementing robust risk management practices, such as conducting regular reputation audits, developing crisis management plans, and ensuring transparency and accountability in business operations, can help mitigate reputational risks (Lu et al., Reference Lu, Liang, Zhang, Rong, Guan, Mazeikaite and Streimikis2021; Tang, Reference Tang2006).

4. Interconnections between CSR and risk management in the fashion industry

In the past, academic papers in risk management primarily focused on disruptions, in the supply chain or company processes, impeding the flow of materials, funds, or information among entities (Bode et al., Reference Bode, Wagner, Petersen and Ellram2011). However, it is increasingly crucial to not only understand risks resulting from service interruptions but also to consider all risks associated with sustainability, a critical issue for fashion companies (Cunha et al., Reference Cunha, Ceryno and Leiras2019). In today's socially conscious landscape, companies are increasingly expected to uphold high ethical and sustainability standards. Failing to meet these expectations can result in reputational damage, as consumers and stakeholders demand greater accountability and transparency (Garcia-Torres et al., Reference Garcia-Torres, Rey-Garcia, Sáenz and Seuring2022). Therefore, incorporating social considerations into business strategies and practices is crucial for mitigating reputational risks and maintaining a positive brand image (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Lee and Kang2021; Wang & Sarkis, Reference Wang and Sarkis2013). By understanding the potential sources of reputational risks, continuously monitoring and addressing issues, and aligning business practices with societal expectations, companies can safeguard their reputation, build trust, and secure long-term success in an increasingly competitive and interconnected business environment (Hoejmose et al., Reference Hoejmose, Roehrich and Grosvold2014).

In this context, suppliers play a crucial role, providing goods, services, and raw materials that are essential for an organization's operations. Controlling risk related to suppliers is essential for ensuring ethical standards of the products a company delivers to its customers and at the same time to manage the reputational risk for the brans (Karaosman et al., Reference Karaosman, Perry, Brun and Morales-Alonso2020). By implementing robust supplier management practices, organizations can assess and monitor their suppliers' capabilities, financial stability, adherence to regulations, and commitment to CSR (Bhandari et al., Reference Bhandari, Garza-Reyes, Rocha-Lona, Kumar, Naz and Joshi2022). This enables businesses to identify and address potential risks before they impact operations or tarnish the company's reputation (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Lee and Kang2021). A comprehensive approach to supplier risk management includes properly selecting suppliers, establishing clear contractual agreements that outline expectations and performance standards, and implementing ongoing monitoring and assessment processes (da Silva et al., Reference da Silva, Ramos, Alexander and Jabbour2020). Regular supplier audits, performance evaluations, and transparent communication channels are vital for identifying and addressing issues promptly and effectively (Broccardo et al., Reference Broccardo, Culasso, Dhir and Truant2023; Jaegler & Goessling, Reference Jaegler and Goessling2020). Additionally, fostering collaborative relationships with suppliers can enhance risk management efforts. By working closely with suppliers, organizations can establish open lines of communication, promote transparency, and encourage a shared commitment to risk mitigation (Broccardo et al., Reference Broccardo, Culasso, Dhir and Truant2023; Chan et al., Reference Chan, Wei, Guo and Leung2020; Karaosman et al., Reference Karaosman, Perry, Brun and Morales-Alonso2020). Collaborative approaches, such as supplier development programs or partnerships, can help build resilience in the supply chain and create a culture of continuous improvement (Shin & Park, Reference Shin and Park2021). However, a survey published by the ACE Group in Europe, conducted among a sample of 45 luxury companies (ACE Insured, 2014), reveals that approximately 75% of risk managers consider reputation as the most valuable asset for their company, and 80% agree that reputation risk is the single most difficult risk category to manage. Almost 6 out of 10 respondents reported that globalization has increased the interdependence of the risks they face, citing a lack of tools and procedures as the main barriers to effective reputation risk management.

Proactively managing supplier risk not only protects an organization's operations but also enhances its competitive advantage (Bhandari et al., Reference Bhandari, Garza-Reyes, Rocha-Lona, Kumar, Naz and Joshi2022). By ensuring the reliability and quality of supplier inputs, businesses can deliver consistent and high-quality products or services to their customers; by aligning supplier selection with CSR criteria, companies can also enhance their reputation, meet evolving consumer expectations, and contribute to a more sustainable supply chain (Gurnani et al., Reference Gurnani, Ray and Wang2011; Quintana-García et al., Reference Quintana-García, Benavides-Chicón and Marchante-Lara2021; Tate et al., Reference Tate, Ellram and Kirchoff2010).

The fashion industry has witnessed several scandals that have highlighted the importance of including social issues in supply chain risk management. Notable examples include: the Rana Plaza collapse in 2013 resulted in the death of over 1100 textile workers; child labor exploitation drawing attention to issues surrounding labor ethics and human rights; worker rights violations such as denying fair wages or imposing unsafe working conditions (Hartmann, Reference Hartmann2021). These violations have underscored the imperative for implementing robust social risk management practices within the fashion industry. These scandals vividly illustrate the reputational risks that emerge when social concerns are neglected or disregarded in supply chain management (Chan et al., Reference Chan, Wei, Guo and Leung2020; Rafi-Ul-Shan et al., Reference Rafi-Ul-Shan, Grant, Perry and Ahmed2018). They underscore the importance of implementing effective risk management strategies that encompass CSR considerations. By proactively monitoring and addressing social risks within their supply chains, fashion companies can protect their brand reputation, ensure compliance with labor standards, and foster sustainable relationships with stakeholders. Ultimately, integrating social risk management into fashion supply chains is essential for maintaining ethical practices, safeguarding worker welfare, and upholding industry accountability (Handfield et al., Reference Handfield, Sun and Rothenberg2020). Based on the model of Cuhna et al. (Reference Cunha, Ceryno and Leiras2019), social risks for a fashion encapsulate a wide array of considerations spanning human rights, societal impact, labor practices, and the diverse conditions under which work is conducted. These encompass multifaceted dimensions, including but not limited to ensuring equitable treatment and protection of workers' rights across the supply chain, fostering diversity and inclusion within the workforce, maintaining stringent health and safety standards in work environments, and evaluating the broader societal implications of corporate activities on local communities and stakeholders. Mismanagement or oversight of these risks can trigger a cascade of adverse effects, spanning various facets of the business. First, it can result in severe reputational damage, tarnishing the company's image and eroding stakeholder trust (Colucci et al., Reference Colucci, Tuan and Visentin2020). Financially, mishandling social risks can lead to substantial monetary losses, stemming from decreased consumer trust, legal penalties, or operational inefficiencies (Achabou, Reference Achabou2020; Zeng et al., Reference Zeng, Audrain-Pontevia and Durif2021). Operationally, failure to address social risks may disrupt production processes, supply chain operations, and overall business continuity. Moreover, strained relationships within the supply chain, arising from non-compliance with CSR standards, can compromise strategic partnerships and supplier collaborations, further exacerbating operational challenges (Chan et al., Reference Chan, Wei, Guo and Leung2020; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Napier, Runfola and Cavusgil2020a, Reference Liu, Ndubisi, Liu and Barrane2020b). Beyond financial and operational repercussions, mismanagement of social risks can have profound human and legal implications (Luque & Herrero-García, Reference Luque and Herrero-García2019). Occupational hazards and unsafe working conditions not only endanger employees' well-being but also expose the company to potential litigation and regulatory sanctions (Jackson et al., Reference Jackson, Bartosch, Avetisyan, Kinderman and Knudsen2020). Addressing social risks thus emerges as a critical imperative for fashion businesses, necessitating proactive measures to mitigate adverse impacts and uphold ethical and sustainable business practices throughout their operations.

5. Research aim

In recent years, there has been a growing recognition of the importance of integrating CSR principles and risk management approaches within supply chain management (Karwowski & Raulinajtys-Grzybek, Reference Karwowski and Raulinajtys-Grzybek2021; Kim et al., Reference Kim, Lee and Kang2021; Lu et al., Reference Lu, Liu and Falkenberg2022). This is particularly relevant in industries such as the fashion sector, where maintaining a strong brand image and reputation is crucial for sustained business success (Cunha et al., Reference Cunha, Ceryno and Leiras2019; Kumagai & Nagasawa, Reference Kumagai and Nagasawa2023; Rafi-Ul-Shan et al., Reference Rafi-Ul-Shan, Grant, Perry and Ahmed2018). The fashion sector is characterized by highly fragmented supply chains, comprising numerous small suppliers, while simultaneously upholding a high standard of brand image communicated to the end customer (Sinha et al., Reference Sinha, Sharma and Agrawal2022; Talay et al., Reference Talay, Oxborrow and Brindley2020). As fashion brands increasingly resort to outsourcing activities in the production of goods, it becomes imperative to address cross-cutting issues related to suppliers, encompassing not only operational production stages but also social factors (Bubicz et al., Reference Bubicz, Barbosa-Póvoa and Carvalho2021; Chan et al., Reference Chan, Wei, Guo and Leung2020; Choi et al., Reference Choi, Feng and Li2023). The interplay between CSR and risk management in supply chain presents a complex and multifaceted challenge in the fashion industry (Kumagai & Nagasawa, Reference Kumagai and Nagasawa2023; Raian et al., Reference Raian, Ali, Sarker, Sankaranarayanan, Kabir, Paul and Chakrabortty2022). The potential impact of reputational risks, including scandals or controversies involving strategic suppliers, can significantly damage brand image, resulting in tangible and intangible losses as well as missed business opportunities (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Lee and Kang2021). This underscores the need for a comprehensive approach that protects the business while concurrently safeguarding the company's image, profitability, and continuity of operations (Hogarth et al., Reference Hogarth, Hutchinson and Scaife2018; Landi et al., Reference Landi, Iandolo, Renzi and Rey2022). Consequently, the management of the supply chain extends beyond the traditional concept of procurement, intertwining with risk mitigation strategies anchored in CSR principles (Karwowski & Raulinajtys-Grzybek, Reference Karwowski and Raulinajtys-Grzybek2021).

To address these concerns, the research aims to explore the strong connection between safeguarding social responsibility conditions and the associated risk with supply chains. By investigating the interplay between CSR principles and risk management this study seeks to shed light on the potential benefits and implications of adopting sustainable-based strategies within the fashion sector. Specifically, the study will examine how integrating CSR principles into supply chain management practices can mitigate reputational risks by enhancing at the same time brand resilience and the sustainability of operations. The research question driving this study is:

RQ: How CSR principles and risk management strategies can be integrated in fashion supply chains?

By delving into this research question, the study aims to contribute to the existing body of knowledge by providing empirical evidence on the effectiveness of sustainability-based strategies in managing supply chain risks and sustaining long-term business success in the fashion sector. The current literature notably lacks empirical cases that thoroughly explore the essential multisectoral sustainability transformation: instead, the emphasis tends to be on delineating the existing unsustainability rather than articulating the transformative process needed for improvement (Salomaa & Juhola, Reference Salomaa and Juhola2020). Wide-ranging literature calling for this transformative approach has emerged in recent years (Horcea-Milcu et al., Reference Horcea-Milcu, Dorresteijn, Leventon, Stojanovic, Lam, Lang and Zimmermann2024).

To address increasingly pressing social challenges, the transformative strand of sustainability science seeks to move beyond a descriptive-analytical stance in order to explore and contribute to the implementation of radical alternatives to dominant and unsustainable paradigms, norms, and values. However, in many cases, the academic world is still lacking contributions that can demonstrate with empirical evidence the transformation of processes and organizations (Marciniak et al., Reference Marciniak, Urbach, Schneider, Krug, de Bremond, Stafford-Smith, Selomane, Fenn, Chong and Paillard2024).

The findings of this study will offer insights and practical implications for fashion brands and supply chain practitioners seeking to enhance their risk management capabilities while upholding CSR principles. Ultimately, the study aims to foster a deeper understanding of the intricate relationship between CSR, risk management, and supply chain management in the fashion sector, highlighting the potential benefits of adopting a holistic approach to address the challenges faced by contemporary global supply chains. Embedded within this rationale is the acknowledgment of the critical necessity for empirical evidence to bolster transformative initiatives in sustainability science. By clarifying the implications of the research – specifically, elucidating how CSR-based strategies can effectively manage supply chain risks – this study aims to highlight the importance of bridging the divide between theoretical discussions and real-world application. Through empirical inquiry, this study endeavors to furnish concrete proof of the transformative capacity of CSR-driven strategies in mitigating supply chain risks, thus playing a pivotal role in advancing knowledge and guiding strategic decision-making within the fashion industry.

6. Methodology

6.1 Research design and sample selection

In this study, an in-depth case study was adopted to explore the research objectives and gain a comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon under investigation (Voss et al., Reference Voss, Tsikriktsis and Frohlich2002). By delving deep into the intricacies and complexities of the research topic, this approach enables researchers to gain a comprehensive understanding of the underlying dynamics and provides rich, detailed insights. This in-depth examination facilitates the exploration of complex issues within a specific setting, allowing for a nuanced analysis and the generation of valuable knowledge. An inductive method was employed, involving the examination of empirical cases to identify relevant patterns (Rogerson & Parry, Reference Rogerson and Parry2020). Inductive research starts from a neutral standpoint, allowing generalizable themes to naturally emerge from the data (Abbasi, Reference Abbasi2012). Given the exploratory nature of our research, this method provided the flexibility to uncover insights directly from the data, rather than seeking to confirm pre-existing hypotheses (Meredith, Reference Meredith1993). This approach facilitated a deeper understanding of the subject matter through the identification of patterns and themes that arose organically during the analysis. Given that the research was exploratory, aiming to investigate a relatively unknown area to uncover new insights, the inductive method was particularly suitable (Caniato et al., Reference Caniato, Doran, Sousa and Boer2018). It provided the flexibility to discover new patterns, rather than limiting the analysis to predefined concepts.

The selection of the case was carefully made, considering its strong relevance to the research question and the availability of comprehensive and reliable data. In this study, the unit of analysis chosen is the fashion supply chain to study the interplay between CSR and risk management within this industry. As emphasized by Choi and Wu (Reference Choi and Wu2009), adopting the supply chain as the unit of analysis requires careful consideration of the adequacy of focal entities to capture supply level phenomena. In this study, the fashion supply chain encompasses a diverse range of entities, including manufacturers/suppliers, reflecting the complexity of fashion supply chain (Dubois & Fredriksson, Reference Dubois and Fredriksson2008). Additionally, the study acknowledges that it employs a single case design, focusing on one specific fashion supply chain because, as advocated by Choi and Wu (Reference Choi and Wu2009), this study aims to delve into the intricate dynamics and interactions within a specific supply chain. Specifically, the selected supply chain consists of companies collaborating with a leading international brand in the fashion industry, renowned for its unwavering commitment to CSR practices with a turnover exceeding 1 billion euros. Through the analysis of this supply chain, valuable insights can be gained into how companies effectively integrates CSR principles into its day-to-day operations and the consequential impact on risk management processes.

The study specifically gathered information concerning the brand owner, which controls the dynamics of the supply chain, as well as 11 suppliers constituting the supply chain (Table 1). Suppliers were selected to ensure comprehensive coverage of all phases and product categories involved in the brand's procurement and subcontracting processes. The aim of this selection was to establish a robust and diverse supplier base capable of meeting the brand's demands across various products and activities throughout the entire supply chain effectively. The selection of this case was based on personal connections established between the brand owner and the researcher, facilitating privileged access to the topics under study. The brand owner company subsequently shared contacts within its procurement and supply network. Raw material suppliers and manufacturers with the highest production volumes placed in Italy from the latest collection were chosen with the purpose of being representative of fashion supply chains (Yin, Reference Yin2008). These suppliers were then contacted to request their participation in the study. This direct involvement provided unique opportunities to gather rich and nuanced data, facilitating a comprehensive understanding of the complex dynamics within the research context. Case study interviews, observations, and access to internal documents were conducted to ensure a more holistic and insightful exploration of the case study and triangulation of primary and secondary sources (Yin, Reference Yin2008).

Table 1. Composition of the fashion supply chain

6.2 Data collection

Primary data were gathered through semi-structured interviews during company visits in 2022 with key informants, including top-level executives, CSR managers, and employees involved in managing CSR projects and related risk management. These interviews aimed to capture the perspectives and experiences of individuals directly involved in implementing CSR and managing risks within the company. More specifically, individuals in multiple roles were interviewed to mitigate informant biases, particularly concerning representativeness (Miles & Huberman, Reference Miles and Huberman2003).

The study employed a structured interview protocol to ensure consistency in the data collection process (Yin, Reference Yin2013) which was structured as follows:

• Benefits and challenges of incorporating CSR into supply chain management in fashion supply chains.

• Benefits and challenges associated with integrating CSR principles into risk management strategies in fashion supply chains.

• How the integration of CSR principles and risk management approaches interests fashion supply chains.

Secondary data sources included company documents and reports on CSR and risk management. These sources were analyzed to provide additional context, validate the interview findings, and gain a broader understanding of the research topic (Yin, Reference Yin2008). To further ensure robust data triangulation, interviews were combined with extensive secondary data from a variety of documents and reports (Yin, Reference Yin2013). This data collection process involved obtaining documents from multiple departments and independent sources, such as documents published online from different sources, rather than solely relying on those provided directly by company management. By doing so, the potential for bias that might arise if the company were to selectively provide documents and choose interviewees was minimized. This approach ensured a more comprehensive and accurate representation of the organizational environment. The data came from diverse sources, including internal reports, independent online reports, and publicly available documents, which aids in triangulating observations and conclusions. Follow-up interviews were also conducted to verify the consistency of responses over time. This comprehensive approach assures greater accuracy and reliability through the use of multiple, varied sources (Heim et al., Reference Heim, Peng and Jayanthi2014; Yin, Reference Yin2013). The interview transcripts and relevant documents were coded and organized, allowing for the identification of patterns, relationships, and key findings. To enhance the validity and reliability, the study's confounding factors were also considered, with particular attention given to their relevance within the research context (Fan et al., Reference Fan, Yeung, Yiu and Lo2022; Kim et al., Reference Kim, Jeon, Sohn, Lee and Kim2024; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Jia, Jia and Koufteros2021; Palmon et al., Reference Palmon, Chen and Chen2024). External market conditions can significantly influence organizational behaviors and outcomes; economic fluctuations, industry-specific trends, and competitive pressures are examples of such conditions. To mitigate the impact of these external factors, follow-up interviews to observe changes were conducted. Additionally, secondary data were analyzed such as market reports and economic forecasts, to contextualize the findings within broader market dynamics. Internal policy changes within the organizations, such as changes in leadership, organizational restructuring, and new strategic initiatives are some examples of internal variables, during the study period could also affect the results. To account for these factors, all relevant internal policy changes were reported during the interviews, cross-rereferring this information with internal documents and reports. This approach allowed us to isolate the effects of specific policy changes and consider their potential impact on the study's conclusions.

Furthermore, in the realm of conducting interviews with employees during company visits, ethical considerations hold paramount importance. Central to these considerations is the adherence to principles governing informed consent, ensuring that participants are fully apprised of the nature, purpose of their involvement in the study (Gao et al., Reference Gao, Li and Sun2023). This necessitates transparent communication regarding the voluntary nature of participation, the intended use of gathered data. Furthermore, rigorous measures are employed to safeguard the anonymity and confidentiality of participants, thereby mitigating the risk of unintended disclosure of sensitive information. To this end, stringent protocols are implemented for data collection and storage. Equally critical is the recognition and mitigation of interviewer–interviewee dynamic, which may potentially influence the autonomy of participant responses. Strategies to address such power differentials encompass establishing a supportive and non-coercive interview environment, fostering open dialogue, and actively soliciting feedback to ensure the equitable treatment of all participants.

6.3 Data analysis

In the study, established recommendations for data analysis in case studies were followed, aiming to derive significant research findings from a variety of sources, including interview transcripts, documents, and observations. To manage the inherent challenges posed by the richness of collected data, a mixed-methods approach was employed. Initially, the collected data, encompassing interviews, documents, and observational notes, were transcribed and coded (Yin, Reference Yin2008). An initial process of coding was undertaken to identify and categorize key themes, concepts, and patterns within the data (Miles & Huberman, Reference Miles and Huberman2003).

Subsequently, thematic analysis was conducted to identify prevalent themes and patterns, facilitating the summarization, aggregation, and classification of research constructs pertinent to CSR and risk management practices within the fashion supply chain (Miles & Huberman, Reference Miles and Huberman2003). This involved closely scrutinizing the data and identifying recurring ideas, significant events, and relevant concepts related to the integration of CSR and risk management in the fashion industry.

In ensuring clarity and transparency in data interpretation, integrative measures were adopted, including the incorporation of visual materials to elucidate the interrelationships among various factors influencing CSR and risk management outcomes (Sousa & Voss, Reference Sousa and Voss2001). Furthermore, to bolster the rigor of the analysis, interview citations from raw data to interpretation were integrated, aligning with established best practices in case study methodology (Yin, 2014). A within-case analysis was used to examine each supplier individually to understand their unique approach to CSR and risk management; cross-case analysis was then conducted to compare and contrast the findings across the different suppliers, allowing for a broader understanding of trends and patterns in the fashion industry. Subsequently, the findings were then synthesized to address the research question and provide insights into the integration of CSR and risk management in the fashion industry. Through the in-depth case study approach, a comprehensive and detailed exploration of the relationship between CSR and risk management was undertaken, providing a nuanced understanding of their integration within the selected company. This approach allowed for a thorough examination of the company's CSR practices and risk management strategies, their interplay, and the impact they have on various aspects of the business.

Through the implementation of these strategies, a harmonious balance was sought between presenting interpretations and substantiating findings with concrete data (Ketokivi & Choi, Reference Ketokivi and Choi2014). This methodological approach enabled a comprehensive exploration of the intricate dynamics within the fashion supply chain.

Data analysis of the study focused on several dimensions concerning the integration of CSR principles and risk management strategies in fashion supply chains, directly addressing the research question. Table 2 outlines parameters for data analysis.

Table 2. Data analysis parameters

7. Results

First, this study aims to unveil the interactions of embedding CSR frameworks and risk mitigation practices in the context of fashion industry supply chains. The following section presents the results pertaining to research question RQ1, which explores how CSR principles and risk management strategies can be integrated within the dynamics of fashion supply chains.

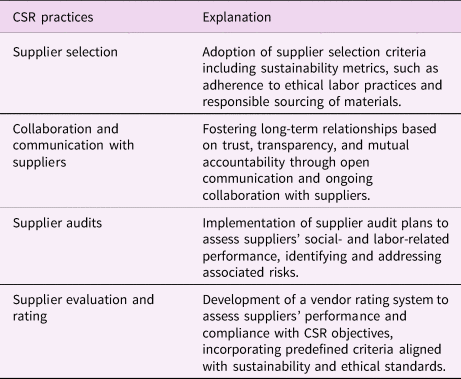

The analysis of the fashion supply chain unveiled compelling evidence regarding the pivotal role of CSR in enabling effective coordination and control of all relevant suppliers within the supply chain. Through the integration of sustainable practices, the selected company successfully mitigated and managed global risks associated with its supply chain. CSR adoption provided enhanced visibility and oversight of suppliers, ensuring adherence to ethical labor practices and responsible sourcing. This encompassed criteria for supplier selection that prioritized sustainability metrics, such as ethical labor practices and responsible sourcing of materials. By meticulously selecting suppliers aligned with these criteria, the company minimized potential risks and negative impacts linked to non-compliant or unethical practices. Additionally, the application of CSR practices fostered ongoing collaboration and communication with suppliers, promoting responsible business practices and fostering long-term partnerships built on trust, transparency, and mutual accountability. Close collaboration with suppliers enabled the brand to address potential vulnerabilities, anticipate and mitigate risks, and implement necessary corrective measures promptly. Furthermore, the integration of sustainability principles into supply chain management not only protected the company's reputation and mitigated operational disruptions but also contributed to broader societal benefits. By ensuring that suppliers adhered to ethical and sustainable practices, the company demonstrated its commitment to CSR and contributed to positive social impact in the communities where its suppliers operated.

To achieve these goals, the company implemented a comprehensive supplier audit plan across its entire supply chain. This plan aimed to assess the social- and labor-related performance of its suppliers, ultimately identifying and addressing any potential risks. The audit process involved conducting on-site visits to supplier facilities, where qualified auditors evaluated various aspects of their operations, including working conditions, labor practices, health and safety measures, management systems, and compliance with applicable laws and regulations. Through these audits, the company identified key risks within its supply chain, such as poor working conditions, insufficient health and safety measures, non-compliance with labor laws, pollution, and inadequate supplier transparency. Based on the audit findings, the company developed tailored strategies and action plans to effectively respond to these risks. This included working closely with suppliers to address non-compliance issues, implementing corrective actions, and providing support and resources for capacity building and improvement. Moreover, the company developed a vendor rating system to further strengthen its supply chain management practices. This system served as a tool for evaluating and assessing the performance and compliance of its suppliers on an ongoing basis. The vendor rating system incorporated a set of predefined criteria and metrics aligned with CSR and risk management objectives, including factors such as labor standards, product quality, delivery performance, and ethical business conduct. One significant challenge was ensuring alignment with the objectives of coordination and supplier monitoring across all business units of the brand. Given the complex and multifaceted nature of the supply chain, it was crucial to engage various stakeholders and departments within the organization to achieve effective implementation. Extensive communication and collaboration between different teams, including procurement, sustainability, risk management, and operations, were essential. Each team had specific goals and responsibilities, but they needed to work together seamlessly to achieve overarching objectives. A clear and comprehensive communication plan was developed to ensure all stakeholders were informed about the purpose, scope, and expected outcomes. Regular meetings, workshops, and training sessions fostered understanding and commitment from all departments.

Furthermore, a cross-functional steering committee was established to oversee progress and facilitate collaboration between departments. This committee served as a platform for sharing insights, addressing concerns, and making decisions collectively, ensuring alignment with the brand's overall strategy. The brand also invested in training programs and capacity-building initiatives to enhance the knowledge and skills of employees involved in supply chain management. These efforts helped create a shared understanding of the importance and role of each department in achieving objectives. Through these concerted efforts, the brand successfully aligned all business units with the objectives of coordination and supplier monitoring. This alignment was crucial for establishing a unified approach to supplier management, ensuring all departments worked toward common goals, ultimately contributing to the overall success of the project and the brand's commitment to CSR and risk management in its supply chain.

To assess supply chain coverage, a comprehensive mapping exercise identified and documented all key suppliers and their associated tiers. This mapping created transparency and visibility into various stages and actors involved in the brand's supply chain. The advancement of activities, particularly the number of audits performed and anomalies discovered, served as crucial indicators of progress and effectiveness. Audits evaluated suppliers' compliance with CSR standards, including labor practices and ethical sourcing. Anomalies detected during these audits provided insights into areas of potential risk and non-compliance that required immediate attention and corrective actions. Collected data from the supply chain mapping exercise and audit activities were stored in a purpose-built database, serving as a centralized repository for information. This database allowed efficient storage, organization, and retrieval of data related to supplier profiles, audit results, and other relevant metrics. A robust reporting platform facilitated the extraction and visualization of key insights and trends from the data, providing a comprehensive understanding of the supply chain's performance in terms of CSR and risk management. Reports and dashboards generated through the reporting platform presented findings clearly and concisely, offering stakeholders valuable information on overall compliance status, areas of improvement, and emerging trends. Data-driven decision-making was enabled, allowing the team to identify patterns, prioritize actions, and track progress over time. The use of a dedicated database and reporting platform ensured efficient data management and analysis, enhancing overall transparency and accountability. Stakeholders could access relevant information and reports in a timely manner, fostering collaboration and informed discussions and decision-making. The company also committed to ensuring responsible and ethical practices throughout its supply chain by adopting the framework for responsible fashion supply chains (OECD, 2023). This model provided a comprehensive framework for managing social risks in the fashion industry, aligning with international guidelines and best practices. By implementing the framework, the company aimed to proactively identify and address potential risks associated with its suppliers and their practices. This included thorough assessments of suppliers' social- and labor-related performance, as well as active engagement in dialogue and collaboration to promote continuous improvement. The framework emphasized the importance of transparency and traceability in supply chains. The company implemented measures to ensure that information about suppliers, including their certifications, audits, and compliance with CSR standards, was readily available and accessible. This enabled informed decision-making and appropriate actions to mitigate risks and ensure compliance throughout the supply chain. The company also recognized the significance of stakeholder engagement in achieving responsible supply chain management. It actively collaborated with relevant stakeholders, including industry associations and local communities, to exchange knowledge, share best practices, and address common challenges. This collaborative approach strengthened the company's risk.

To summarize, Table 3 outlines how CSR principles and risk management strategies can be integrated into fashion supply chains.

Table 3. How of CSR and risk management can be integrated in fashion supply chains (RQ1)

8. Discussion. Supply chain traceability: mitigating risks and ensuring CSR in fashion supply chains

The evidences of this study shed light on the crucial role of supply chain traceability as a tool for ensuring CSR and effective management in the fashion industry. Through an in-depth examination of the integration of traceability practices within the supply chain, several key insights emerged, highlighting the significance and benefits of traceability in promoting CSR and enabling efficient management processes. First and foremost, traceability plays a pivotal role in ensuring CSR throughout the fashion supply chain. By tracking production processes, and monitoring the involvement of different suppliers in the chain, brands can establish transparency and accountability. This transparency allows for the identification of potential ethical issues, such as forced labor, child labor, or hazardous working conditions, and facilitates the implementation of corrective measures. Moreover, traceability empowers brands to ensure that their suppliers adhere to CSR standards, promoting fair labor practices sustainability.

Furthermore, traceability serves as a powerful tool for risk management. The ability to trace products throughout the supply chain enables brands to identify and address potential risks associated with their suppliers and production processes. This includes assessing the reliability and compliance of suppliers, mitigating the risk of counterfeit or unauthorized production. By proactively managing risks, brands can protect their reputation, minimize disruptions, and enhance the overall resilience of their supply chains. The utilization of traceability in mitigating reputational risk is a critical aspect for brands operating in the fashion industry. Reputational risk can arise from various factors, including unethical practices, labor exploitation, or product safety concerns. By implementing robust traceability systems, brands can effectively track and monitor their supply chains, thereby reducing the likelihood of reputational damage and enhancing brand integrity.

Traceability allows brands to have full visibility into their supply chains, from the sourcing of raw materials to the final production stages. This comprehensive understanding enables them to identify any potential risks or non-compliance issues at various stages of the supply chain. By having this information readily available, brands can take prompt action to address any identified issues, ensuring that their products are produced ethically and sustainably. Traceability enables brands to demonstrate transparency and accountability to their stakeholders, including customers, investors, and regulatory bodies. By providing accurate and verifiable information about their supply chains, brands can build trust and credibility. Consumers, in particular, are becoming increasingly conscious of the social and impact of their purchasing decisions. By showcasing their commitment to responsible sourcing and production through traceability, brands can attract and retain socially conscious consumers. In addition to mitigating reputational risks associated with social issues, traceability also plays a crucial role in ensuring product safety and quality. By tracing the origin of raw materials and monitoring the production processes, brands can identify and address any potential risks related to product integrity. This includes the use of hazardous substances, compliance with safety regulations, and adherence to quality standards. By proactively managing these risks, brands can safeguard their reputation

Additionally, traceability facilitates effective management by providing valuable data and insights. Through the collection and analysis of supply chain data, brands can gain a comprehensive understanding of their operations, identify inefficiencies, and make informed decisions. This data-driven approach enables brands to optimize processes, reduce waste, and enhance resource allocation. Moreover, traceability enhances collaboration and communication among different stakeholders within the supply chain, fostering closer relationships and enabling coordinated efforts toward achieving social goals.

The integration of traceability practices, however, presents certain challenges that need to be addressed. One key challenge is the complexity of supply chains in the fashion industry, characterized by multiple tiers of suppliers, subcontractors, and outsourced production. Ensuring traceability across these fragmented networks requires robust data management systems, standardized protocols, and collaborative efforts among all actors involved. Additionally, the cost implications of implementing traceability measures can be significant, particularly for small- and medium-sized enterprises. Therefore, it is essential to develop cost-effective solutions and provide support to enable broader adoption of traceability practices.

Table 4 summarizes the main findings emerged from the study regarding the crucial role of supply chain traceability not only in ensuring CSR but also in risk management for fashion supply chains.

Table 4. Role of supply chain traceability in fashion supply chains

The interconnections between CSR and risk management present a compelling area of exploration with profound implications for both organizations and society at large. CSR encompasses a diverse array of factors, from labor practices to community engagement, human rights, and social equity. Effectively managing CSR risks is paramount for organizations to uphold their social license to operate, safeguard their reputation, and cultivate positive relationships with stakeholders. In the context of the fashion industry, the practice of traceability emerges as a pivotal tool in mitigating various risks. Supply chain traceability serves as a linchpin in addressing compliance risk by ensuring adherence to regulatory standards and ethical practices across the supply chain. It also plays a vital role in managing reputational risk, as brands can track and monitor production processes to mitigate the likelihood of unethical practices, labor exploitation, and product safety concerns. Furthermore, traceability contributes to mitigating strategic risk by enabling informed decision-making to safeguard long-term interests. Financial risk management is enhanced through traceability, as it facilitates better resource allocation and process optimization, thereby minimizing waste and inefficiencies. Additionally, operational risk is mitigated as traceability allows brands to identify and address potential disruptions or vulnerabilities in the supply chain, ensuring smooth and uninterrupted operations. This proactive approach not only helps in mitigating reputational damage but also strengthens brand integrity and fosters consumer trust and loyalty.

9. Conclusions

This study fills significant gaps in current literature by providing tangible evidence regarding the efficacy of CSR-driven strategies in managing supply chain risks and fostering sustained business success within the fashion industry. Currently, there exists a noticeable scarcity of empirical studies delving into cross-sectoral sustainability transformations. Recent appeals for a transformative stance in sustainability science underscore the necessity for empirical contributions that showcase the metamorphosis of both processes and organizational structures. By bridging these gaps, this study offers practical insights valuable to fashion brands and supply chain professionals aiming to bolster their risk management capabilities while adhering to principles of social responsibility. Its overarching objective is to enrich comprehension of the intricate interplay among CSR, risk management, and supply chain dynamics within the fashion realm, advocating for a comprehensive approach to confront modern global supply chain intricacies.

The insights derived contribute not only to a deeper comprehension of the specific company's practices, but also offer broader implications for the fashion industry as a whole. By examining the integration of CSR and risk management within the selected company, valuable lessons and best practices emerge that can be applied by other industry players. The study underscores the importance of aligning CSR principles with risk management approaches, showcasing how they can mutually reinforce each other to enhance overall sustainability and resilience in this industry. The findings serve as a valuable resource for industry practitioners, policymakers, and researchers seeking to navigate the complexities of integrating CSR and risk management in the fashion sector.