This article explores the relationships between archaeological research, preconquest and colonial-period documents, and legal and ethical considerations in Oaxaca, Mexico, with a particular focus on the emic approach of the Teozacoalco Archaeological Project, which uses a sixteenth-century map to contextualize archaeological remains. It begins with overviews of the types and nature of documents, where they are archived, and how they are used in exhibits, publications, and archaeological research, in order to expose a distinctive type of archaeological practice conducted in the region. Then it summarizes relevant laws, treaties, and agreements that have an impact on the ethics and practice of conducting document-oriented archaeology. Next, it explores ways of decolonizing documents and invites reflection on the nature of archaeological practice in relation to the indigenous communities where documents originated or that are referred to in documents. Finally, it ties together the previous topics, discusses best practices for archaeologists, and explores some approaches that both novice and experienced practitioners might use.

The focus is on documents originating in the area of New Spain (Nueva España), the region that today comprises much of the central highlands of the republic of Mexico, but excluding the states in the north and far southeast of the country. Most of the documents were created after the Spanish Conquest of the sixteenth century, but a few are preconquest, and many from the early colonial period refer to places, people, and events from before the Spanish arrived. Thousands reside in archives within Mexico, and a few remain within the communities that created them, but many, including some that are extremely significant to Mesoamerican researchers, are in archives and museums in other countries: the United States and former European colonial powers.

In order to limit this article to a reasonable length, the focus is further restricted to documents from the southern Mexican state of Oaxaca, homeland of the Mixtec, Zapotec, Chontal, Mixe, and other indigenous peoples. Important examples of preconquest and early colonial documents from Oaxaca still exist, whereas many similar documents from other parts of Mesoamerica have been lost.

Oaxacan documents located within communities, in Mexican archives, and in depositories outside of the country have inspired and continue to inspire archaeological surveys and excavations as well as ethnohistorical research that is helping to reconstruct the past. Oaxaca today has one of the highest percentages of indigenous inhabitants of any state in Mexico, requiring that most archaeological work undertaken there involve some sort of negotiation with native communities. Both indigenous and nonnative researchers have begun the process of decolonizing Oaxacan archaeology through various means, including by enabling access to information and by replacing names of documents that are vestiges of the colonial era with indigenous names. Although decolonizing names of documents is laudable, most scholarly publications refer to their “colonial” names, and this article will also do so for the sake of clarity.

DOCUMENTS OF NEW SPAIN

Some preconquest Mesoamerican civilizations were literate and produced screen-fold documents called codices containing religious, cosmological, genealogical, and historical information. The codices were painted on gesso-coated animal skins or bark (amate) paper and generally contained a combination of pictures and glyphs that identified people, places, and calendrical dates. (The Maya, who lived outside the area of New Spain, were fully literate; their hieroglyphic system could express virtually any concept.) Spanish priests destroyed many codices, particularly those of the Maya, during the early colonial period because they considered their content to be demonic (Arbagi Reference Arbagi2011).

Fortunately, some codices survived, particularly ones from New Spain. Mundy (Reference Mundy1996) listed a total of 24 codices from highland Mexico, including Mixtec codices from Oaxaca in preconquest style (but not all dating from before the conquest): Becker I and II, Bodley, Colombino, Egerton, Selden, Vindobonensis, and Zouche-Nuttall. The Bodley and Zouche-Nuttall are preconquest. The Colombino and Becker I are both fragments of a single preconquest codex (Troike Reference Troike1974). The obverse and reverse of the preconquest Vindobonensis are separate texts (Jansen and Pérez Jiménez Reference Jansen and Jiménez2000). The Edgerton and Becker II are fragments of a single colonial-period codex (Doesburg Reference Doesburg2001). Additional colonial-period Mixtec codices are the Baranda, Topográfico Fragmentado, Dehesa (Doesburg Reference Doesburg2001), Muro (López García Reference López García1998), Yanhuitlán (Berlin Reference Berlin1947), and Tulane (Smith and Parmenter Reference Smith and Parmenter1991). The colonial-period Selden (Caso Reference Caso1964) is a palimpsest; recent analysis (Snijders et al. Reference Snijders, Zaman and Howell2016) has begun to reveal long-hidden preconquest images.

Kroefges (Reference Kroefges, Zborover and Kroefges2015) listed types of colonial-period documents pertaining to the eastern Oaxacan coast, which is an excellent summary of the documents of New Spain. Historical-cartographic and genealogical pictorials include maps and large manuscripts drawn on sheets of woven cloth (lienzos). Alphabetic administrative documents are census and taxation reports, synthetic clerical descriptions, geographic reports (Relaciones Geográficas), viceregal grants (licencias, mercedes, títulos), decrees (mandamientos), orders (ordenes), commissions (comisiones), land inspection reports (diligencias), and lawsuit documentation and testimonies (autos). Both Spanish and indigenous artists and authors produced pictorial and alphabetic documents.

Maps (mapas) were produced to accompany diligencias, vice-regal grants, lawsuits, and Relaciones Geográficas (Méndez Martínez Reference Méndez Martínez1999; Mundy Reference Mundy1996; Spores and Saldaña Reference Spores and Saldaña1973). An important subset were those accompanying the 11 series of Relaciones Geográficas between 1523 and 1825 (Gerhard Reference Gerhard1993). The most significant Relación in terms of preserved maps occurred between 1579 and 1582. Responding to a mandate from the King of Spain, Philip II, the Council of the Indies sent a list of 50 questions to local governments in the Americas. Question 10 requested a map of the territory drawn on paper. From this period, 69 maps remain; 45 were drawn by indigenous artists and 20 are from Oaxaca (Mundy Reference Mundy1996).

Lienzos are often combinations of maps, visual histories of communities, and genealogies. In 1975, about 90 were known from the sixteenth to twentieth centuries. Since 1975, 33 more have been discovered in archives and indigenous communities. Of that number, 58 are from Oaxaca (Johnson Reference Johnson and Brownstone2015).

The Mapa de Teozacoalco (Figure 1) is “the largest and most important of the corpus” of maps accompanying Relaciones (Mundy Reference Mundy1996:74) and provides a good example of the content of both indigenous maps and lienzos. The majority of the mapa shows the territory of Mixtec San Pedro Teozacoalco, including the principal town (cabecera) and 13 secondary settlements (sujetos or estancias), geographic features, toponyms representing features defining the border, and Spanish glosses explaining the names of settlements and some of the municipality's history. A smaller section of the document provides portraits of the dynastic rulers of Teozacoalco and neighboring Tilantongo during preconquest and early colonial times. Logographs (Figure 2) below the dynasties are translated as the Mixtec names of Tilantongo and Teozacoalco (Chiyo Cahnu; Jansen and Pérez Jiménez Reference Jansen and Jiménez2005). The Mapa de Teozacoalco, in combination with its associated Relación Geográfica, acted as the equivalent of a Rosetta Stone for Caso's (Reference Caso1949, Reference Caso and Willey1965, Reference Caso1977) interpretation of dynastic histories in Mixtec codices.

FIGURE 1. The Mapa de Teozacoalco. East is at the top. Image used with permission of the Nettie Lee Benson Latin American Collection, University of Texas Libraries, Austin.

FIGURE 2. Logograph for Chiyo Cahnu, the Mixtec name for Teozacoalco. Photograph by the author, used with permission of the Nettie Lee Benson Latin American Collection, University of Texas Libraries, Austin.

The following overview focuses on where documents of New Spain reside, why many are no longer in their communities of origin, and some positive and negative aspects of the situation.

DOCUMENT DEPOSITORIES

In general, the rarer, more spectacular visual documents, such as codices, maps, and lienzos, are likely to be housed in archives and museums outside of their communities of origin, and even outside of Mexico. Many documents were produced or submitted as evidence in legal cases or to respond to mandates by colonial authorities and never returned to their communities of origin. Presumably destitute individuals or communities sold some to collectors. Others may have been given as gifts. Unscrupulous collectors or researchers stole some documents from communities or archives. Jansen (Reference Jansen1990) explained how codices, specifically, became alienated from Oaxaca.

Within Mexico, the Biblioteca Nacional de Antropología e Historia has a large collection of visual documents (Mohar Betancourt Reference Mohar Betancourt2013; Sepulveda y Herrera Reference Sepúlveda y Herrera2012). Complete or fragmentary Mixtec codices are located in Mexico City, Puebla, London, Oxford, Vienna, Hamburg, and New Orleans (Arqueología Mexicana 2009; Berlin Reference Berlin1947; López García Reference López García1998; Mundy Reference Mundy1996; Smith and Parmenter Reference Smith and Parmenter1991; Valle Reference Valle1999). The 69 maps of the 1579–1582 Relaciones Geográficas reside in four depositories outside of Mexico: Archivo General de las Indias in Seville (24), Real Academia de la Historia in Madrid (10), Benson Latin American Collection at the University of Texas in Austin (33), and University of Glasgow (3) (Mundy Reference Mundy1996; Paso y Troncoso Reference Paso y Troncoso1905). Some lienzos are in museums or libraries outside of Mexico, some are in Mexican institutions, and some remain in their communities of origin. Typical are the Mixtec lienzos of the Coixtlahuaca Group. Of the 11 lienzos in the group, 1 is in Berlin, 1 is in New Orleans, 1 is in Toronto, 1 is in Brooklyn, 2 are in Mexico City, and the remainder are still in housed in the communities that created them (Johnson Reference Johnson and Brownstone2015).

Alphabetic administrative documents vastly outnumber pictorial documents and are largely housed in archives outside of the communities to which they pertain. The Archivo General de la Nación in Mexico is home to 1,579 documents from Oaxaca in the Ramo de tierras, as well as 21 boxes in the Colección de documentos de títulos de tierras (Méndez Martínez Reference Méndez Martínez1999). The archive houses many volumes of documents from Oaxaca from 1540 to 1785 in the Ramo de mercedes, Ramo de indios, and Ramo de tributos (Spores and Saldaña Reference Spores and Saldaña1973, Reference Spores and Saldaña1975, Reference Spores and Saldaña1976). An important source of information from the archive about settlements in Oaxaca, their resources in the early colonial period, and how much they paid in taxes is El libro de las tasaciones de pueblos de la Nueva España, siglo XVI (González de Cossío Reference González de Cossío1952).

Other depositories of documents related to Oaxaca are the Archivo General de las Indias in Seville and the Real Academia de la Historia in Madrid. Among the documents housed there are the Suma de visita de pueblos and some of the Relaciones Geográficas (Paso y Troncoso Reference Paso y Troncoso1905).

There are both positive and negative aspects to such documents residing in depositories distant from their original communities. They are generally kept in more stable environmental conditions and security than would be possible in their communities of origin, which leads to better preservation and survival. They are also generally more easily accessible to nonindigenous researchers than would be the case in geographically remote communities with limited amenities, such as good lighting, space devoted to research, and Internet access. However, they are not easily accessible to the descendants of the people who created them or to which they pertain. Wherever they are located, both indigenous and nonindigenous people find ways to use them for research, teaching, and other purposes, which will be discussed in subsequent sections.

USES OF ARCHIVED DOCUMENTS

Preconquest and early colonial documents housed in libraries, museums, and archives in Mexico and other countries do not just lie unseen in storage. They are available to scholars and the public in a variety of ways. The most obvious manner is that they are the basis of hundreds of books and journal articles available for purchase, through libraries, or online through Google Scholar. These publications include photographs of images, drawings of their content, and analysis of their meaning, antiquity, and context. The Bibliografía Mesoamericana (FAMSI 2016) is an online searchable database of 73,871 records of publications on Mesoamerica through 2012. Searching the keyword “codex” brings up more than 1,000 records.

Depositories have been busy digitizing Mesoamerican documents and making them accessible online along with commentaries about their provenance and histories. One example is the Relaciones Geográficas Collection that is part of the Nettie Lee Benson Latin American Collection at the University of Texas Libraries (University of Texas at Austin 2016). Another example is the Mapas Project at the University of Oregon (Wood Reference Wood2015).

Museums sometimes mount exhibitions of documents or their physical reproductions. The Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto displays a full-size reproduction of the Lienzo de Tlapiltepec because the original is too sensitive to light to be on view (Brownstone Reference Brownstone2015). The Lienzo Seler II will be exhibited in the Humboldt-Forum at the Ethnologisches Museum–Staatliche Museen zu Berlin beginning in 2019 (Excellence Cluster Topoi 2016).

Codices, lienzos, and mapas have been used in teaching about Mixtec culture and language at postsecondary educational institutions and workshops. The Mixtec Pictographic Workshop was offered during the late 1990s and early 2000s at the Maya Meetings, held annually at the University of Texas at Austin. The Mixtec Gateway meeting, held annually in Las Vegas during the 2000s, ended with a workshop focused on the intensive study of a document. Such educational uses have resulted in many research projects targeting Oaxaca.

In order to expose a distinctive type of archaeological practice conducted in Oaxaca, the focus will now shift to the Teozacoalco Archaeological Project and its emic approach to contextualizing archaeological remains based on a sixteenth-century map painted by a Mixtec artist.

RESEARCH INSPIRED BY ARCHIVED DOCUMENTS

Documents in museums, libraries, or national archives, whether in Mexico, the United States, or a former colonial power, have in the past inspired, and continue to inspire, much important research in Oaxaca and throughout Mexico. Varieties of research based on the documents include historical, linguistic, art historical, geographic, genealogical, ethnohistorical, and archaeological. Reviewing some relatively recent edited volumes gives a sense of the breadth of research by Mexican and international scholars using documents from Oaxaca (e.g., Blomster Reference Blomster2008; Desacatos 2008; Jansen et al. Reference Jansen, Kröfges and Oudijk1998; Zborover and Kroefges Reference Zborover and Kroefges2015). Since this is not a review article, space cannot be devoted to listing the many examples of each of these types of research that have occurred from the sixteenth century to today. Instead, one project based on a mapa and its associated Relación Geográfica that are housed in the Nettie Lee Benson Latin American Collection, University of Texas Libraries, Austin, will be used as an example.

The Teozacoalco Archaeological Project has undertaken an emic approach to archaeological fieldwork in the Mixteca Alta region of Oaxaca since 2000 (Shoemaker Reference Shoemaker2000; Whittington Reference Whittington2003; Whittington and Gonlin Reference Whittington, Gonlin, Gonlin and French2016; Whittington and Workinger Reference Whittington, Workinger, Zborover and Kroefges2015). Exploring the area shown on the Mapa de Teozacoalco and described in the Relación was the primary inspiration for the project. Previous archaeological work that integrated use of indigenous and early colonial documents by Bruce Byland and John Pohl in the neighboring area of Tilantongo (Byland and Pohl Reference Byland and Pohl1994), as well as earlier groundbreaking work by Ronald Spores (Reference Spores1972) in the Nochixtlán Valley were additional inspirations.

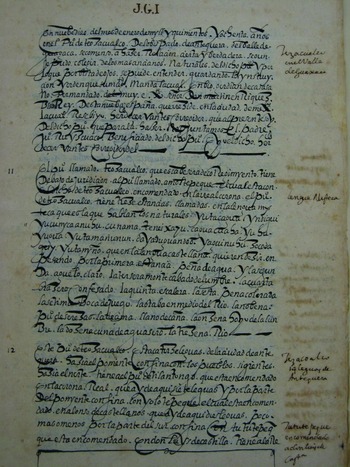

A Mixtec artist drew the Mapa de Teozacoalco in the late 1570s, probably to support a legal case and possibly on the basis of an earlier lienzo (Jansen and Pérez Jiménez Reference Jansen and Jiménez2005). It was submitted in January of 1580 to colonial authorities along with the alphabetic Relación Geográfica de Teozacualco y Amoltepeque (Figure 3; Acuña Reference Acuña1984). Although the documents were well-known before 2000, no archaeological exploration of the area had been undertaken (Anders et al. Reference Anders, Jansen and Pérez Jiménez1992a; Balkansky et al. Reference Balkansky, Kowalewski, Rodríguez, Pluckhahn, Smith, Stiver, Beliaev, Chamblee, Espinosa and Pérez2000).

FIGURE 3. First page of San Pedro Teozacoalco's Relación Geográfica. Photograph by the author, used with permission of the Nettie Lee Benson Latin American Collection, University of Texas Libraries, Austin.

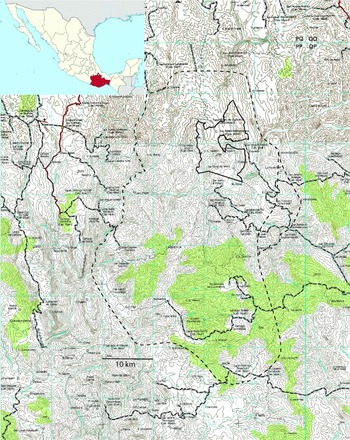

The goals of the project have evolved through time. One of the original, very modest, goals was to visit San Pedro Teozacoalco, the principal town (cabecera), which is still inhabited, and try to locate various secondary settlements (sujetos or estancias), some of which are long abandoned. Another of the original goals was to explore border areas and try to identify landscape features that correspond to toponymic glyphs around the edge of the map in order to confirm Mundy's (Reference Mundy1996) reconstruction of the map's territory (Figure 4). The team recorded the locations of settlements and landscape features with GPS devices and transferred their coordinates to modern topographic maps.

FIGURE 4. Reconstructed border of Teozacoalco in AD 1580 (broken line) and the border of the current municipality of San Pedro Teozacoalco (continuous line). North is at the top. The inset shows the location of the state of Oaxaca. Main map created by Daniel Whittington. Inset map from Wikimedia Commons.

Project goals quickly became more ambitious as the existence of numerous and extensive preconquest sites not shown on the map became known, authorities showed the team a collection of well-preserved artifacts stored in San Pedro Teozacoalco's municipal palace, and the team interacted and negotiated with indigenous and nonindigenous citizens of communities within the territory shown on the map. These new goals included incorporating local people into the project as guides and laborers who could tell the names of sites and landscape features, providing assistance to San Pedro Teozacoalco to help set up a community museum, and providing information about the project and the Mapa de Teozacoalco to municipal authorities and common citizens. The team continued to record site locations, eventually transferring their coordinates and data on their areal extent to maps generated by ArcMap that integrated data from the Mexican Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (Figure 5). Team members drew sketch maps of sites, collected ceramic sherds and obsidian from the ground surface, completed site recording forms required by the Archaeological Council (Consejo de Arqueología) of the Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, and submitted required yearly reports in Spanish.

FIGURE 5. Locations of archaeological sites encountered by the Teozacoalco Archaeological Project. The map shows Teozacoalco's municipal boundary (frontera municipal), locations and areas in m2 of archaeological sites (sitio arqueológico área), locations of archaeological sites with uncertain areal extents (incierto), a dense area of buildings (edificios densos), rivers or streams (río o corriente), and contour lines (curva de nivel). Map created by the author using ArcMap.

Project goals began to focus on culture contact and colonialism as research led to a deeper understanding of the relationship between the Mapa de Teozacoalco, its associated Relación Geográfica, and other preconquest and colonial documents. Analysis of the dynastic sequences of Teozacoalco and Tilantongo drawn on the left side of the map and relating them to the histories recorded in the Codices Bodley (Jansen and Pérez Jiménez Reference Jansen and Jiménez2005), Zouche-Nuttall (Anders et al. Reference Anders, Jansen and Pérez Jiménez1992a), Vindobonensis (Anders et al. Reference Anders, Jansen and Pérez Jiménez1992b), Selden (Caso Reference Caso1964), Tulane (Smith and Parmenter Reference Smith and Parmenter1991), Egerton (König Reference König1979), and Muro (López García Reference López García1998), the Mapa de Macuilsuchil (Mundy Reference Mundy1996), and Spanish colonial records has revealed much. Teozacoalco experienced autochthonous cultural development, arrival of rulers from other Mixtec and Zapotec polities, imposition of an Aztec garrison, and Spanish colonialism during different phases of its long history. Teozacoalco also sent members of its elite to found dynasties in other communities. In pursuit of investigating culture contact and colonialism, the team spent one season test-pitting carefully targeted sites to define the ceramic sequence, learn about obsidian trade networks, and explore the time-depth of human habitation.

More recently, the primary goal has shifted to complete mapping and spatial analysis of Iglesia Gentil, a large site on top of Cerro Amole, using powerful GPS devices and ArcMap software (Figure 6), in order to explore the history, structure, and functions of the largest and most complex site within the territory of the Mapa de Teozacoalco and to define its relationship to the present town of San Pedro Teozacoalco. Unlike other preconquest sites that do not appear on the mapa, this one is identified by a red cross atop a tiered structure on top of a mountain south of the town. While pursuing this latest goal, the project continues to work with the local community in the ways described previously.

FIGURE 6. Map of Iglesia Gentil, a large site atop Cerro Amole, south of the town of San Pedro Teozacoalco. The capital of Chiyo Cahnu was located here between about AD 1085 and AD 1321. The map, based on data collected with GPS devices in 2013, 2015, and 2017, incorporates geographic data obtained from the Mexican Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía. The legend (leyenda) explains symbols used in the map to identify the locations of intermittent streams (corriente intermitente), contour lines (curva de elevación), roads (camino), edges of depressions (depresión), stairs (escalón), structures (estructura), terraces (terraza), areas of depression (depresión), stairways (escalera), mounds (montículo), patios (patio), and platforms (plataforma). Map created by the author using ArcMap.

Based on the integration of data from documents and archaeology, preliminary project results to date include the following. Before the conquest, the territory was inhabited by a large population that had developed in place for at least 2,800 years. Obsidian and ceramic trade networks extended hundreds of kilometers and connected the inhabitants to people living far away and in different environments. Chiyo Cahnu as a named place existed since at least AD 1040, and the first dynasty was founded by a royal couple from Mixtec Tilantongo and “Tiger Town” in AD 1125. They placed their new capital atop Cerro Amole that year or soon afterward. The capital remained in that lofty location until a royal couple from Zapotec Zaachila and Tilantongo arrived to found the third dynasty in AD 1321. They soon moved the capital down from Cerro Amole to the current site of San Pedro Teozacoalco, where the foundation of the rulers’ palace still remains. Teozacoalco sent royal second sons to other communities to found dynasties, and the polity had widespread influence. It controlled a large territory before the conquest, but by 1580 the territory of the municipality of San Pedro Teozacoalco had shrunk to about 30 by 70 km (2,100 km2). Since then, the colonial municipality has been divided into many smaller municipalities, and the extent of San Pedro Teozacoalco today is only about 72 km2.

The focus will now be on relevant laws, treaties, and agreements that have an impact on legal and ethical considerations of conducting document-oriented archaeology. This is something rarely addressed in the archaeological and ethnohistorical literature of the region.

LAWS, TREATIES, AND AGREEMENTSFootnote 1

Precolumbian art is generally protected by laws or regulations within its country of origin that prohibit its export without special permit. In the past, such laws and regulations, which were often hard to interpret and enforce, were notable for the frequency with which they were ignored, both by people leaving these countries and by customs officials there and in the United States and other countries. Many times, people leaving with objects in their luggage or among their shipped belongings apparently were unaware of the laws. However, many objects were illicitly exported by intermediaries, presumably with knowledge of the laws, who arranged for objects to be transferred from the people who looted archaeological and historic sites to collectors in the United States and other developed countries. In the absence of specific import restrictions on such objects, there was little call to return them to their countries of origin.

In July 1970, the United States and Mexico signed the Treaty of Cooperation between the United States of America and the United Mexican States Providing for the Recovery and Return of Stolen Archaeological, Historical, and Cultural Properties. The treaty covers objects defined, in part, as “art objects of the precolumbian cultures of the United States of America and the United Mexican States of outstanding importance to the national patrimony, including stelae and architectural features such as relief and wall art.” As part of the treaty, each country agrees to help recover and return stolen property from its territory. “Stolen” and “art” are nebulous terms in relation to property that was collected in Mexico and sold to other collectors outside of Mexico.

The looting and illicit movement of heritage objects became so widespread that the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) adopted the Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property on November 14, 1970. The purpose of the convention is to stop the flow of cultural property across international borders, thereby reducing the looting of archaeological and heritage sites. The convention defined cultural property as “property which, on religious or secular grounds, is specifically designated by each state as being of importance for archaeology, prehistory, history, literature, art or science,” and goes on to list 11 categories. The convention entered into force on April 24, 1972. The United States Senate ratified the convention in 1972, but federal legislation implementing the convention was not passed until September 2, 1983. Title III of Public Law 97–446, Convention on Cultural Property Implementation Act, entered into force on December 2, 1983. After it accepted the convention, the U.S. government was bound to give great weight to requests by signatory countries for help in interdicting the illegal flow of their cultural property across the borders of the United States. The provisions of the convention are not retroactive.

Of importance in relation to the convention is Section 312 of the Convention on Cultural Property Implementation Act. “Certain Material and Articles Exempt from Title” states that the provisions of this chapter shall not apply to

any designated archaeological or ethnological material or any article of cultural property imported into the United States if such material or article . . . has been within the United States for a period of not less than twenty consecutive years and the claimant establishes that it purchased the material or article for value without knowledge or reason to believe that it was imported in violation of law [Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs 1987].

Mexico responded to the implementation of the convention by the United States:

The Government of the United Mexican States has studied the text of the comments and reservations on the convention on the means of prohibiting and preventing the illicit import, export and transfer of ownership of cultural property made by the United States of America on 20 June 1983. It has reached the conclusion that these comments and reservations are not compatible with the purposes and aims of the Convention, and that their application would have the regrettable result of permitting the import into the United States of America of cultural property and its re-export to other countries, with the possibility that the cultural heritage of Mexico might be affected [UNESCO 1970].

Despite Mexico's negative comments, the United States was one of the earlier countries where documents from Oaxaca are now housed to ratify or accept the convention (UNESCO 1970). Since the provisions of the convention are not retroactive and virtually all important documents outside of Mexico left before the 1970 adoption of the convention, Mexico and, by extension, the indigenous communities where those documents originated, are not likely to succeed in repatriating them from the United States or former colonial nations.

Decolonizing documents can involve their physical repatriation, but there are other options. The next section explores some of them.

DECOLONIZING DOCUMENTS

Mexico has little power under current international laws and agreements to repatriate documents from the United States and former colonial powers. Indigenous communities within Mexico have even less likelihood of repatriating documents from outside the country. They might have more success in returning documents from archives and museums within Mexico to their communities, but that is a matter of internal negotiation and policies.

In lieu of physical repatriation, some indigenous researchers and their nonnative allies have undertaken to decolonize documents and the projects they inspire through various means (Zborover Reference Zborover2014, Reference Zborover, Zborover and Kroefges2015). Leading the way are the University of Leiden's Gabina Aurora Pérez Jiménez, who is Mixtec, and Maarten Jansen. They argue that it is preferable to use names for codices that reflect the original culture, rather than the first foreign owner or the library where they currently reside (Jansen and Pérez Jiménez Reference Jansen and Jiménez2000, Reference Jansen and Jiménez2007). They and others have proposed decolonized names of all of the preconquest and some of the early colonial Mixtec codices (Table 1).

TABLE 1. Decolonized Names of Some Mixtec Codices.

*Colonial-period codices.

Note: Data from Arqueología Mexicana (2009), Hermann Lejarazu (Reference Hermann Lejarazu2008), Jansen and Pérez Jiménez (Reference Jansen and Jiménez2000, Reference Jansen and Jiménez2005, Reference Jansen and Jiménez2007), López García (Reference López García1998), and Valle (Reference Valle2002).

Another approach is for native speakers of Mixtec to use documents to teach and diffuse their language. An example is Ubaldo López García's (Reference López García1998) collaboration with other Mixtec speakers to explain the images of the Codex Muro, while simultaneously demonstrating the similarities and differences in variants of Mixtec spoken in different communities.

Finally, native perspectives can be incorporated into interpretations of documents. Examples include the publications by Jansen and Pérez Jiménez (Reference Jansen and Jiménez2000, Reference Jansen and Jiménez2005, Reference Jansen and Jiménez2007). König (Reference König, Zborover and Kroefges2015) solicited input from members of the community of Santa María Cuquila to interpret the Codex Selden and found that the townspeople had strong opinions about a codex originating in their town being housed in the British Museum in London. The Teozacoalco Archaeological Project also did the same for the Mapa de Teozacoalco (Whittington Reference Whittington2003).

Examples such as these lead to consideration of best practices for archaeologists. The next section ties together the previous topics and explores some approaches for both novice and experienced practitioners.

BEST PRACTICES FOR ARCHAEOLOGISTS

Archaeologists working in Oaxaca have found that they must negotiate and address community needs in order to implement their projects. In a recent review of Mixtec archaeology, Pérez Rodríguez (Reference Pérez Rodríguez2013) ended with a discussion of cultural resource management, community archaeology, and the associated politics in the Mixtec area of Oaxaca. She mentioned the impact that suspicion of archaeologists, internal community dynamics, and intercommunity conflicts have on projects. Given that archaeologists cannot return the documents that inspire their projects to the people whose ancestors created them, what can they do to overcome suspicion and help the people in those communities?

Archaeologists working in Oaxaca have tried a variety of approaches, some more effective than others. Pérez Rodríguez (Reference Pérez Rodríguez2013) noted that, historically, sharing of research results began with written reports being presented to local communities, but they often ended up being filed away in some office. A more effective approach was to create posters of project results and display them on a wall of the municipal palace. While surveying in the central Mixtec area, leaders of one project offered to pay daily wages to community members who accompanied team members to sites and provided reports in Spanish to each community (Kowalewski et al. Reference Kowalewski, Balkansky, Walsh, Pluckhahn, Chamblee, Rodríguez, Espinosa and Smith2009). Archaeologists with the Cerro Jazmín Archaeological Project endeavored to educate the public about archaeology and cultural resource management, develop culturally appropriate and effective plans to protect Cerro Jazmín, and develop strategies to grow food for dense populations in a challenging environment (Pérez Rodríguez Reference Pérez Rodríguez2014). Research centered on Santiago Apoala led investigators to provide the community with recommendations for necessary protective measures related to heritage preservation, including ways to handle tourism and present local views of history (Geurds and Van Broekhoven Reference Geurds and Van Broekhoven2006). The leaders of the Proyecto Arqueológico Nejapa y Tavela provided public talks, participated in local events, and presented posters about archaeological findings to the community (Konwest and King Reference Konwest and King2012). Members of the Teozacoalco Archaeological Project provided the towns surveyed with copies of the Mapa de Teozacoalco and reports and books in Spanish, put up posters identifying project personnel and specifying project goals, hired local laborers to assist in surveys and excavations, gave public presentations to schools and the public, and more (Whittington and Gonlin Reference Whittington, Gonlin, Gonlin and French2016).

Pérez Rodríguez (Reference Pérez Rodríguez2013) reported that an effective and recent approach has been to create museum exhibits or tourist amenities centers. A significant subset of negotiated outcomes in Oaxaca has involved helping to set up community museums, or museos comunitarios (Hoobler Reference Hoobler2006; Morales et al. Reference Morales, Camarena, Arze and Shepard2009; Morales Lersch and Camarena Ocampo Reference Morales Lersch, Ocampo and García2002; Salas Landa Reference Salas Landa2008; Sepúlveda Schwember Reference Sepúlveda Schwember2011; Zborover Reference Zborover2014). Community museums are important to indigenous communities throughout Mexico, both because they help to educate people about their past and, perhaps unrealistically, because they are believed to attract tourists and their money. The Chontalpa Historical Archaeology Project trained “indigenous committees in documentation and management of cultural heritage, the restoration of the historical archive and conservation of several important pictorial and alphabetic documents, and the creation of the first community museum and educational center in the Chontal highlands” (Zborover Reference Zborover, Zborover and Kroefges2015:307). Although the Teozacoalco Archaeological Project has not been successful in helping San Pedro Teozacoalco to open a community museum, it provided necessary infrastructure and assistance by purchasing storage shelves and conservationally correct storage materials and by bringing a conservator from the United States to treat ancient objects in the town's possession and to advise about appropriate storage and conservation techniques (Whittington Reference Whittington2003).

Finally, some archaeological projects in Oaxaca make it a point to integrate oral traditions into their research designs, giving community members voices in the discovery and interpretation of the past. Recent examples include the Chontalpa Historical Archaeology Project (Zborover Reference Zborover, Zborover and Kroefges2015), the Teozacoalco Archaeological Project (Whittington Reference Whittington2003; Whittington and Workinger Reference Whittington, Workinger, Zborover and Kroefges2015), and a project at San Miguel el Grande (Jiménez Osorio and Posselt Santoyo Reference Jiménez Osorio, Santoyo, Zborover and Kroefges2015).

Examples from Oaxaca should encourage archaeologists to adopt decolonizing practices in their projects, when appropriate. Archaeologists can successfully use indigenous and colonial documents to help reveal the past. However, practitioners should think more deeply about the documents they use and what they represent to various audiences. Archaeologists may find themselves expected to arrange the return of colonial documents housed far away from indigenous communities in exchange for access to areas, despite limitations of current laws; they should think creatively about ways to provide access to those documents without physically repatriating them. By becoming sensitized to the needs and desires of indigenous communities while understanding current legal limitations on repatriation, archaeologists can interact respectfully and successfully with those communities and work together with them to reveal the past.

CONCLUSIONS

Documents created before the conquest and during the early colonial period by indigenous people in Mexico, and documents produced during the colonial period by nonindigenous administrators, have for centuries ended up in museums, libraries, and archives distant from where they originated. Some movement resulted from the realities of colonial governance, while some was related to financial transactions involving the sale of legally possessed or stolen property. Whatever the underlying cause of the migrations, many of the documents, as is the case with archaeological objects, are now protected by treaties, laws, and international agreements. It is unlikely, however, that such protection will lead to the repatriation of documents to Mexico, much less to the communities where they originated. Although physical possession of cultural patrimony is a priority of nations and indigenous peoples across the globe, in today's digital environment, it is becoming increasing easy to obtain remote access to documents so that communities can explore and reconnect with their past. Archaeologists working in Oaxaca and other indigenous areas, especially on projects involving preconquest and early colonial documents, have an ethical responsibility to design their projects so that they facilitate local communities in doing so.

Acknowledgments

Fieldwork since 2000 has been supported by the Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies, Inc. (FAMSI); Mudge Foundation; Selz Foundation; Social, Behavioral, and Economic Sciences Research Fund and Pro Humanitate Fund at Wake Forest University; and, particularly, the Patterson Foundation. The late David Shoemaker was the driving force behind the first year of fieldwork, upon which subsequent years have been based. Crew members have been Karla Itandehui Aguilar Vázquez, Nancy Anchors, Jamie Forde, Soren Frykholm, Nancy Gonlin, Jessica Hedgepeth, Ronald Harvey, Laura LePere, Leonardo López Zárate, Kelly Loud, the late Dale Mudge, Taylor Mudge, Kenneth Robinson, Delia Rojas Granados, Ismael Vicente Cruz, Christine Whittington, Daniel Whittington, Quinn Whittington, Andrew Workinger, and Kate Yeske. John M. D. Pohl's inspiration and guidance of David Shoemaker; Nancy Troike's strong encouragement and advice; and help from Jeffrey Blomster, Arthur Joyce, Michael Lind, Robert Markens, Cira Martínez, and Marcus Winter have been vital. Work has been possible only with support and permission of the Consejo de Arqueología of the Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia (archaeological permits P.A. 13/02, 05/04, 27/07, 25/12, 14/14, and 07/17). I am grateful for the hospitality and willingness to collaborate of the authorities and citizens of the present-day municipalities within the territory of colonial Teozacoalco. Many thanks to Katie Kirakosian and Heidi Bauer-Clapp for developing this thematic issue and to the anonymous reviewers who improved this submission.

Data Availability Statement

Artifacts collected by the Teozacoalco Archaeological Project are stored in the Exconvento San Pedro y San Pablo Teposcolula and in the Exconvento de Cuilapan de Guerrero, both in Oaxaca, Mexico. Copies of data collection forms, site recording forms, field notes, and preliminary reports are stored in Oaxaca City at the Centro INAH Oaxaca. Final reports and a “global” report summarizing project activities during the years 2000–2011 are stored at the Centro INAH Oaxaca and in Mexico City at the Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia. Public accessibility to these materials is probably very difficult to arrange. Requests for access to original notes, drawings, forms, reports, photographs, and digital mapping files can be made to Stephen L. Whittington at whittisl@gmail.com, by calling (336) 782–1469, or by writing National Mining Hall of Fame and Museum, PO Box 981, Leadville, CO 80461, USA.