Introduction: Suspicious transactions

In current political debate and counterterrorism policy, we can signal a broad trend whereby security authorities require private companies to monitor transactions, report suspect statements, close accounts, and mine their databases for potential terrorist connections. In November 2014, for example, the report into the killing of UK soldier Lee Rigby suggested that Facebook may have been able to stop the attack, because one of the perpetrators had expressed his intentions to ‘kill a soldier’ in his online communications. The UK Intelligence and Security Committee (ISC) found that if this online exchange had been known to security services, the perpetrators might have been stopped. The report laments that Internet service providers like Facebook do not regard themselves to be under any obligation to report such suspicious expressions to authorities.Footnote 1 In response, Facebook did not question whether such security role would be within its legal competences, but instead revealed that it routinely deletes customer accounts on the basis of potential links to terrorism. In fact, after the Rigby murder, Facebook reported to the British GCHQ that it ‘had disabled seven of [the perpetrator] accounts ahead of the killing, five of which had been flagged for links with terrorism’.Footnote 2 Far-reaching legislation that obliges social media companies to report suspicious exchanges is currently being debated in the UK, as well as other countries including the US.Footnote 3

Ahead of formal legislation, the UK National Counter Terrorism Internet Referral Unit works closely with companies, and has effected the removal of over 160,000 ‘pieces of extremist and terrorist material’ from the Internet.Footnote 4 By comparison, since its establishment in January 2015, Europol’s Internet Referral Unit has removed more than 6,000 pieces of suspect online content, in cooperation with social media companies.Footnote 5 In February 2016, Twitter announced that on its own initiative it has suspended over 125,000 accounts in less than one year, primarily for potential links to IS (Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant). This may be new for Twitter, but it is not so for banks, wire transfer companies and other financial institutions, which have the legal obligation to report suspicious transactions potentially relating to terrorism in a regulatory regime dating back to the mid-1990s. In the UK for example, Suspicious Transactions Reports from the banking sector increased from over 200,000 in 2007 to over 300,000 in 2013.Footnote 6

Transactions analysis forms part of a security chain, whereby commercial data are analysed, collected, reported, shared, moved, and eventually deployed as a basis for intervention by police and prosecution. In this context, private companies – including Facebook and Twitter, airlines and banks – find themselves in the frontline of fighting terrorism and other security threats. Companies identify, select, search, and interpret suspicious transactions. They monitor, regulate, restrict, and expel client groups. Clearly, this is not a new phenomenon: as a growing literature notes, private companies, in many ways, have become security actors in their own right.Footnote 7 Existing literature offers substantial critical analysis of security professionals and their modes of knowledge production, including technical artefacts and calculative practices.Footnote 8 Research on Private Military Companies (PMCs) has focused on the question whether security is ‘outsourced’ to private companies, or whether companies have become ‘deputised’ by law enforcement.Footnote 9 There is increasing recognition that the conceptual divide between public and private is fluid and contested.Footnote 10 Sometimes, then, these security practices are understood as emergent public/private assemblages.Footnote 11

Compared to private military or security companies, however, banks, airlines, and social media companies are extremely reluctant security actors. Policy initiatives in the name of countering terrorism have positioned a diversity of non-security actors into the frontline, including for example teachers and medical staff.Footnote 12 In the case of banks and Twitter, the political and moral pressure that they police their servers and mine their transactions databases is in tension with their profit motive and their obligations of client confidentiality,Footnote 13 even if commercial objectives become sometimes grafted onto new security roles.Footnote 14 Rather than a mode of security ‘outsourcing’, this involves a process of authorisation and appropriation, whereby private companies like banks, money transfers businesses, and Twitter reluctantly learn to see the world through a security lens. These examples challenge the common idea of a military-security nexus, that supposes an alignment between commercial interests and security projects. The public/private relation here is one of friction, tension and contradiction.Footnote 15 This yields a set of questions that is slightly different from those normally posed within the literatures on private security: What happens when non-security private companies – such as banks, but also airlines and social media companies – are effectively authorised to make security judgements in the frontline of fighting terrorism? What are the processes whereby commercial data such as Facebook expressions and financial records become inscribed with suspicion, and reported, shared, or moved from private to public domains? What are the contradictions and tensions between security objectives and commercial interests, and how does security become grafted onto commercial environments?

This article develops the notion of the Chain of Security in order to conceptualise the ways in which security judgements are made across public/private domains and on the basis of commercial transactions. For Bruno Latour, a ‘chain of translation’ is the set of practices whereby objects are identified, collected, registered, transferred, and interpreted in the context of scientific research and the production of scientific facts.Footnote 16 Appropriating Latour’s concept, I argue that we can visualise the path of the suspicious transaction as a chain of translation, whereby commercial transactions are collected, stored, transferred, and analysed in order to arrive at security facts (including for example frozen assets, closed accounts, and court convictions). This conceptualisation shifts focus toward the trajectory of the suspicious transaction itself, to follow its modulations as its moves across public and private domains. In doing so, the article aims to contribute to debates at the intersection between International Relations (IR) and Science-and-Technology Studies (STS). The dialogue between STS and IR is offering productive new ways of theorising and researching the role materialities and ‘things’ in international politics.Footnote 17 These literatures offer rich resources for analysing the ‘material dimensions of knowledge production’.Footnote 18 This article engages more deeply with the analytical instruments offered in the work of Latour and others. It seeks to foster a ‘radically processual understanding of producing security’.Footnote 19 It offers a way to unpack the tempo-spatial distribution of expert practices: by understanding knowledge production not as a nebulous process, but as dependent upon relatively regulated sequences of interpretation and movement.Footnote 20

Before going on to develop this argument, it is important to emphasise that private security judgements such as account closures and asset freezing can have major effects on individual lives and political freedom. Critical questions have been raised concerning the criteria underlying judgements to remove online content and close bank accounts, and the limited possibilities that citizens have to seek redress when wrongly targeted.Footnote 21 Though perhaps we could argue that having a Twitter or Facebook account is not a human right, one US court has now ruled that boarding an airplane is not a luxury but a life’s necessity in contemporary society, which is marked by geographically dispersed families.Footnote 22 Research into suspicious transactions mining in banks, moreover, has shown that these regulations have limited the operational scope and freedom of humanitarian organisations in recent years.Footnote 23 We now also have examples whereby such banking requirements have led to the debanking of entire groups – disproportionally Muslim charities.Footnote 24

More than a conceptual exercise, then, this article seeks to develop what Anna Leander calls a ‘thinking tool’, to empirically analyse and critique the ways in which companies act in the frontline of security practice. Thinking tools help to define ‘what to think about’ (the reluctant security practices of companies) and ‘what to look at’ (the concrete trajectory of the suspicious transaction).Footnote 25 The article starts with a discussion of Latour’s work in order to examine how it is relevant to the study of security knowledge. It then goes on to follow a specific financial transaction, in order to illustrate a chain of security in practice. The final section of the article draws out how the concept of the chain of security seek to contribute to debates at the intersection of International Relations and Science-and-Technology Studies.

The chain of translation

In Pandora’s Hope, Latour discusses and analyses the scientific practices that ‘produce information about a state of affairs’.Footnote 26 In particular, he examines how scientific facts are produced in a research project concerning the question whether the Amazonian forest is advancing or retreating, which has great significance for our knowledge concerning climate change, as well as for possible investment opportunities in the local area. In order to reconstruct how scientists produce knowledge concerning the state of the Amazonian forest, Latour joins a field trip of French and Brazilian scientists, which has the objective to study the boundary between forest and savannah, and to collect soil samples for analysis. Latour offers a thick description of the soil science expedition, narrating how specific samples of soil are identified, collected, made transportable, inscribed in field logs and dossiers, transported to the (Parisian) ‘center of calculation’, analysed, debated and modelled, to produce, eventually, scientific facts as published in an academic journal. The process involves the ‘passage from a clump of earth to a sign’ to a scientific fact.Footnote 27

The production of these pedological facts involves, for Latour, neither a flawless correspondence between the world and the word, nor a profound, unbridgeable gap of representation.Footnote 28 Instead, the translation of the world into words involves the practice of what Latour calls circulating reference. Each sequence in the process refers back to a prior object; each step of selection and inscription form the basis of the next move of the scientists. It involves countless little judgements along the way: selecting locations, collecting the earth, devising durable modes of inscription, coding the samples. This chain of reference, then, does not involve iron-clad scientific discovery but entails a ‘risky, intermediary pathway’ from situated clump of earth to pedological, scientific fact.Footnote 29 Or, as Latour put it in a different formulation, ‘Accurate facts are hard to come by, and the harder they are, the more they entail some costly equipment, a longer set of mediations, more delicate proofs.’Footnote 30 At each link in the chain of soil collection, transportation, sampling and analysis, there are gaps as well as continuities. Rather than a rigid process, Latour understands the chain of translation to be a dynamic process of continuous circulation, referral, and contestation. It entails a movement ‘back and forth’, across many small gaps of understanding, connecting the two extremities of local matter and (scientific) fact.Footnote 31

I argue that it is fruitful to redeploy Latour’s concepts and methods in order to study the passage of a transaction from simple digital registration to a sign of suspicion to (possible) evidence of wrongdoing in the sphere of security. If we liken a transaction to the soil sample in the Latourian schema, we can render visible the practices that transform – for example – a financial record from simple bank registration, to suspicious transaction to (in some cases) court evidence. As in Latour’s chain of soil analysis, translation is key to the movement and sequencing of transactions data across the security chain.Footnote 32 When transactions are reported from one professional domain to another, they are not simply moved but also modified: they acquire new meanings, new combinations with other data, and new capabilities. As Holger Stritzel has put it, ‘translation … does not just “transport” meaning, but also creatively produces it, it rewrites, rearticulates, re-represents something in new terms’.Footnote 33 At each link in this security chain, then, a transaction does not just change in institutional context, but it changes in meaning: the significance it is inscribed with and the work it is able to do.Footnote 34 For example, within banking practice, a financial transaction may function as indicator of suspicion; within a Financial Intelligence Unit (FIU), the same transaction may function to help build typologies of risky financial patterns; whereas within a court of law it will have to function as evidence (of, for example, the pivotal position of the accused within a wider network).

Latour’s approach has been taken up by existing literatures in security studies that have analysed security expertise as a ‘chain of associations’, or a ‘chain of transcriptions’.Footnote 35 As Julien Jeandesboz has shown for example, the validity of the EU ‘smart border’ proposals was politically produced through a chain of associations whereby the smart border was successfully allied to particular technologies, industries, and databases. Mike Bourne and colleagues similarly analyse the development of security technologies as ‘a succession of comings and goings’ whereby laboratory processes ‘reimagined, transposed and improvised’ security aims.Footnote 36

In our case, we face a number of stumbling blocks and challenges when redeploying Latour’s concept of the chain of translation to the realm of security transactions analysis. A digitally recorded transaction (an ATM withdrawal, a Facebook expression, or a Passenger Name Record) is not material in the sense of the Amazonian soil. If Latour was able to follow the soil samples as they made their way, quite literally, from the depths of the Amazonian forest to Western European centres of calculation, the unpredictable trajectory of digital data is markedly less traceable. Digital transactions data can double, merge, and be endlessly copied. Data paths are fundamentally unpredictable. They hardly constitute the relatively static Amazonian soil samples, that remain securely preserved in their plastic bags and boxes as they move from forest to laboratory.

In addition, the production of security knowledge is far less regulated than that of scientific facts. Latour follows the process whereby the Amazonian expedition and soil collection leads to the eventual production of pedological facts in an academic publication. The production of scientific facts is tightly regulated through the professional conventions of soil scientists and related disciplines. Of course, we know from the literature in the history of sciences that such professional conventions are far from universal, and dependent on historical contingencies and the situated histories of scientists and their patrons.Footnote 37 Nevertheless, the contemporary production of scientific objectivity is tightly regulated and institutionally policed. The production of security knowledge, on the other hand, is much more speculative.Footnote 38 Expertise in the domain of terrorism and counterterrorism is profoundly disputed.Footnote 39 Routines for the production of security knowledge are not settled. These challenges are exacerbated by the prevalence of secrecy in the security domain.Footnote 40 In short, then, Latour’s chain of pedological fact production seems relatively structured and certain compared to the messy, unpredictable, and secretive chains of translation underpinning security facts. As William Walters has put it, ‘How do we “follow the actors” when they operate under cover of national security?’Footnote 41

However, I maintain that it is precisely in the context of the unsettled nature of security knowledge that appropriating and developing Latour’s approach makes sense. Digital data are not materially bounded in the ways that drones, tanks, bodies, and boats are.Footnote 42 They are more akin to what Karen Knorr Cetina has called ‘epistemic objects’, which ‘have the capacity to unfold indefinitely’.Footnote 43 Despite their ‘lack of completeness’, Knorr Cetina argues that epistemic objects can be subject to sociology of knowledge approaches, just as more traditional bounded things and tools are. In her argument, the incomplete, ‘transient’, and ‘unfolding’ ontology of epistemic objects, ‘foregrounds the temporal structure’.Footnote 44 Knorr Cetina draws attention to the temporal, processual way through which unstable knowledge objects acquire ‘stable thinghood’.Footnote 45

The concept of the security chain takes up this challenge in relation to the epistemic object of the suspicious transaction, offering a way to unpack the temporal process through which it materialises. As with the Amazonian forest soil, data(sets) need to identified, selected, and cut from the continuous flow of worldly matter.Footnote 46 Data do not simply flow from one domain to another: they need to be rendered transportable, both technically and juridically. They need to be rendered recombinable with other technologies and datasets.Footnote 47 This involves complex juridical issues, concerning access, jurisdiction, and transfer. It also involves technical issues concerning the interoperability of systems and the complexity of technical integration of platforms, which is quite often more difficult than surveillance literatures might imply.Footnote 48 In addition, there is an increasing recognition that legal provisions like privacy and data protection do not strictly restrain data flows, but in fact order dataflows in particular ways and enable their materialisation.Footnote 49 In this sense, then, suspicious transactions data(sets) are akin Knorr Cetina’s epistemic objects. In the chain of security, the suspicious transaction acquires a stabilised thinghood, which is coupled to the capacity to generate valid security action, including asset freezes and court convictions. It has become a security fact, underpinning policing judgements across public and private domains.

A security chain in action

I have argued that it is possible to visualise the trajectory of a suspicious transaction as a chain of translation. This approach attempts to develop thinking tools for a processual approach to analysing security knowledge. As a way of adding empirical depth to the notion of the security chain, this section hones in on the banking sector – before going on, in the next section, to draw out the contribution of the security chain at the intersection between IR and STS. The banking sector is of particular interest, because banks’ obligations to mine their databases, report suspicions, and freeze transactions is well established in law and regulation, and much further advanced than in other commercial sectors. Recent years have seen a substantial strengthening of what has been called ‘financial warfare’ or the ‘weaponisation of finance’.Footnote 50 The broad policy aims within this complex regulatory landscape are to anticipate terrorist activities by analysing financial flows and to preempt suspicious money transfers. In this sense, financial warfare parallels current developments in the revolution in military affairs (RMA), which use risk-based strategies to deliver the (contested) promise of precision attacks.Footnote 51 But financial warfare is a very different type of ‘war’, operating not through bombs and guns, but through bureaucratic and relatively invisible practices of risk analysis.Footnote 52

Substantial policy and regulatory activity has taken place in the domain of Counter-Terrorism Financing (CTF), ranging from the development of transnational compliance mechanisms by the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), to the implementation of financial sanctions list, to the adoption of new legal tools.Footnote 53

If we really want to understand how the broad policy aims in the name of financial warfare act upon the world – for example, how they affect banks’ procedures, impact upon client (groups), and lead to freezing decisions – we need a processual approach. Like Latour’s Amazonian soil sample discussed in the first part of this article, financial transactions data have to be identified, collected, and made transportable. They need to be inscribed in dossiers, analysed, debated and modelled, in order to be rendered intelligible and valid as security facts. At each link in this chain of translation, this involves countless small judgements, and a ‘dialectic of gain and loss’.Footnote 54 In other words, the financial transaction does not stay the same. It is (re)inscribed, (re)combined, modelled, and morphed.

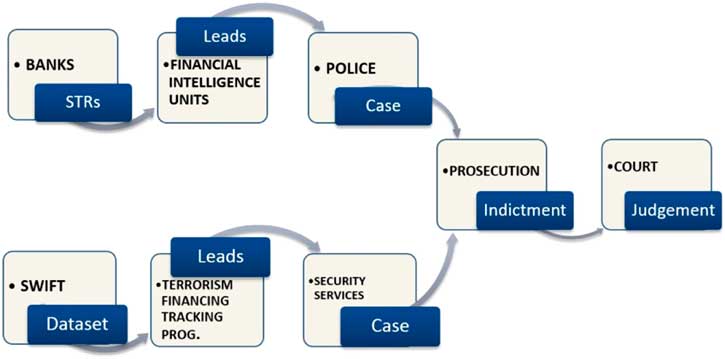

In contrast to the security dream of following the money, I propose to follow the series of translations that render financial transactions into indicators of suspicion, into evidence of wrongdoing in the chain of security. In a schematic rendering, the chain looks roughly as in Figure 1. Banks and other financial institutions are required to deliver Unusual Transactions Reports relating to terrorism to their national Financial Intelligence Units (FIUs). FIUs develop leads for police and prosecution. Subsequently, cases may be referred for further investigation and court deliberation. Alternatively, cases may reach court through the so-called Terrorism Financing Tracking Programme (TFTP), the US-led security programme that analyses transactions data from SWIFT.

Figure 1 The security chain of financial transactions.

Mapping this process of translation, (re)inscription, gain and loss, captures the moments of politics. For example, European banks have started mining their databases for ATM transactions at the Turkish-Syria border.Footnote 55 These practices translate selected mundane transactions from routine ATM withdrawals into indicators of the potential travel of so-called foreign fighters en route to participate in the Syria conflict. In a further translation, such transactions may become indicators of terrorist intent before a court of law, especially now that European courts are increasingly faced with criminal prosecution of cases relating to travel to Syria and terrorist facilitation. In the remainder of this section, we will follow the life of a money transfer of €326 that an unnamed 28-year-old Dutch citizen sent via Western Union on to middle men in Turkey on 29 May 2014, who then handed it to the suspect’s brother, Hatim R., who was known to be fighting for IS.Footnote 56 This transaction materialised as suspicious through the analytical work of Western Union, and it became reported, referred, modified, and recombined, to eventually form part of the court evidence that convicted the sender to a jail sentence for the financing of terrorism.

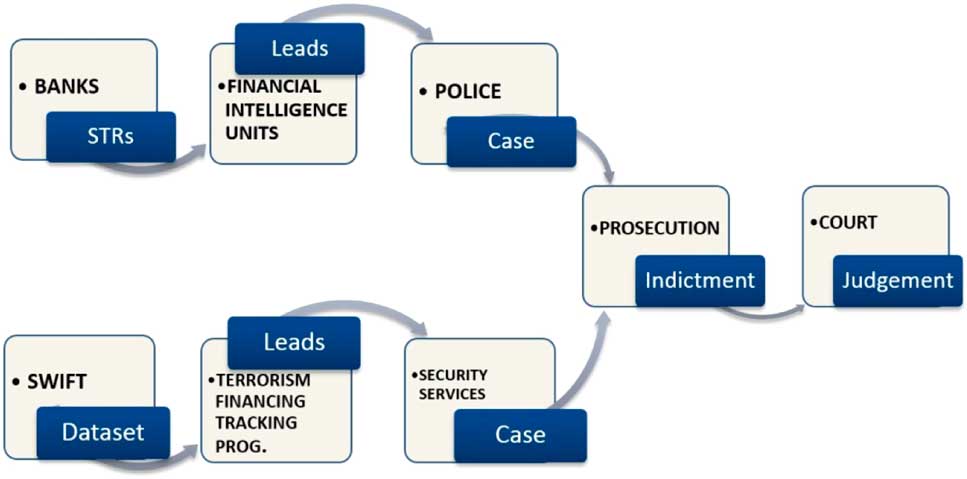

A first link in the chain (Figure 2) concerns banks and other financial institutions such as money transfer businesses. Banks are required by EU Directive freeze transactions relating to sanctions lists, and to report suspicious transactions to national Financial Intelligence Units. Suspicious Transactions Reports (STRs) have increased in number in recent years. In the UK for example, STRs increased from over 200,000 in 2007 to over 300,000 in 2013.Footnote 57 Banks face considerable challenges and uncertainties when implementing counterterrorism financing policies, including an uncertain and fragmented regulatory environment. They deploy a number of strategies to generate suspicious transactions, including in-house risk assessments, externally purchased software tools, and professional deliberation. Banks work with fine-grained client profiles and lifestyle analyses to identify abnormal and suspicious transactions.Footnote 58 Implications of bank profiling remain poorly understood. Client profiles can influence customer service and the cost of credit. In extreme cases, banks can terminate their business relationships with groups that are considered to be risky.Footnote 59 Another major challenge for banks is how to safeguard and practice privacy and client confidentiality, while meeting the substantial demands from regulators. Data protection directly affects the material architectures of data processing within the security chain.Footnote 60 In this sense, data protection does not simply restrain data flows, but enables them in specific ways. It regulates how data are concretely stored, handled, and shared.

Figure 2 From bank to FIU.

Let us follow the €326 Western Union money transfer to Turkey, as it was translated from routine transfer to abnormal transaction. Western European financial institutions now scrutinise cash transfers, ATM transactions, and card spending within specific Turkish regions in order to identify potentially ‘suspect travel’ of persons en route to IS-held territories, as well as financial support to IS combatants. However, it is recognised that there are many legitimate reasons for bank transactions in this region, for example by military personnel stationed there and by diasporas’ visiting family. Thus, compliance departments mine their transactions databases to filter on countries and regions, and combine the results with other information on bank accounts, loans, financial patterns, and social networks. The €326 sent by suspect X to unnamed persons in Turkey, resulted in one or more Unusual Transaction Reports filed by Western Union to the Dutch Financial Intelligence Unit, for a possible connection to terrorism financing. In other words, Western Union translated the €326 transaction from regular digital record of a money transfer, to an ‘unusual’ transaction in the sense defined by Dutch money laundering law (Wwft). The law prescribes that the identification of unusual transactions should depend upon subjective indicators to be determined by the financial institution, instead of criteria prescribed by the regulator. Money transfers constitute the largest proportion of reports received by the Dutch Financial Intelligence Unit in recent years.Footnote 61

A second link (Figure 3) in the financial security chain concerns Financial Intelligence Units (FIUs), which are compulsory in all EU member states. FIUs receive Unusual Transactions Reports from banks, and in their turn pass on information to police and prosecutors (in the form of ‘leads’). Very little is known about how FIUs handle, share, and analyse unusual transaction reports submitted by financial institutions. How do FIUs analyse and interpret banks’ reports in order to develop police and prosecution leads? What types of in-house deliberation take place surrounding the prioritisation of investigations? Is the wire transfer to Somalia a legitimate support of family, or intended to aid al-Shahaab?\

Figure 3 From FIU to police / prosecution.

In order to start addressing these questions, let us further follow the life of the €326 wire transaction to Turkey in 2014. The Dutch FIU processed the unusual transaction report as one of 237,431 wire transfer transactions reported in 2014 of which an estimated 6 per cent was thought to be related to terrorism.Footnote 62 Within FIUs, the unusual transaction is made recombinable with other datasets as well as open source information, with a dual purpose. First, the FIU produces policing leads to be shared with national and regional police forces for follow-up investigations. Secondly, FIUs build their own databases of unusual transactions, which are used for secondary analysis to produce generalised suspicious data patterns and typologies. Such typologies and trends reports are important because they help define what comes to count as suspicious in the context of terrorism financing, and they can be used in criminal proceedings.

Our €326 abnormal transaction was subjected to further analysis by the Dutch FIU, which may typically involve a (re)combination of transaction information with information already on the national and international FIU databases. In further analytical steps, the abnormal transaction record will be combined with details from company registers, tax authorities, and – increasingly – publicly available information for example from social media sites like Facebook and Twitter. After analysis, our €326 was declared to be suspicious – which happened to an estimated 11 per cent of unusual transactions in 2014.Footnote 63 This translation from abnormal to suspicious fundamentally changes the nature of the transaction: it now falls within a different data protection regime and can be shared with police forces, tax authorities, and fraud offices. It also gains significance in the context of terrorism financing typologies and social network analyses, as conducted by police and intelligence services. Information on this €326 transfer was shared with Dutch police and prosecution, who eventually arrested the sender.

A final link (Figure 4) in the chain of financial security concerns prosecution and courts. Clearly, most suspicious transactions reports generated in the financial security chain never lead to court cases. While limited in number however, terrorism financing court cases are interesting because they are at the forefront of the preventive turn in criminal law. They involve the criminalisation of facilitation and terrorist intent.Footnote 64 They bring potential violent futures into the present by criminalising ancillary acts of facilitation and financing. Financial transaction information may be brought before the court as evidence of terrorism facilitation and support. This was the case with our €326, which came to function as evidence before the court in the case of suspect X, accused of the financing of terrorism. In its sentence delivered in March 2016, the Rotterdam court mentions this specific transaction as evidence, alongside eight other money transfers made by the suspect, totaling €17,000. The court judgement asserts that the suspect intended the money to reach his brother Hatim, who is placed on the Dutch national terrorism list and who was convicted by the court of The Hague for participation in a terrorist organisation. The suspect was found guilty of multiple counts of the financing of terrorism, and of ‘contributing to (increasing) destabilization and insecurity in (this region of) Syria’.Footnote 65 He was sentenced to 24 months imprisonment.

In a further and final translation, our €326 transaction is incorporated into a public narrative of a Dutch FIU ‘success story’. It has become part of a sanitised narrative case example presented on the website of the Dutch FIU, serving to illustrate the ‘life-pattern’ of IS combatants.Footnote 66 In a position paper to Dutch Parliament in February 2017, this narrative was presented by the FIU as evidence of its successful combating of terrorism financing.Footnote 67

Figure 4 Court judgement.

Having followed, as example, the €326 transfer to Turkey, my suggestion is that we could similarly follow the life of a Passenger Name Record as it makes is way from commercial flight booking, to Advanced Passenger Information (API) security system, to deployment in front-line border policing, airport questioning, and possibly a denial of entry.Footnote 68 Alternatively, we could follow the life of a Twitter utterance, as it is flagged for violent content and reported to the new shared industry database designed to ‘help identify potential terrorist content on social media and prevent its reappearance on other platforms’.Footnote 69 In a further translation, Twitter utterances may be recombined with other social media records to provide leads for police investigations, and to eventually constitute court evidence.Footnote 70 When we do, we will see that PNR data move quite differently across public and private spheres than financial or social media data do. Airline companies are required to share entire PNR datasets with security authorities – most notably the US Transport Security Agency (TSA) – in a system that ‘pushes’ data to other jurisdictions in advance of flight take-off.Footnote 71 Social media companies like Twitter, on the other hand, do not (yet) have the legal obligation to report suspicious accounts or utterances. However, they are increasingly cooperating with police, such as Europol’s Internet Referral Unit, to identify and remove online content potentially related to terrorism.

In all these cases, the precise circulation of data between private companies and security authorities is slightly different, as is the mode of judgement concerning abnormalities and security risks. Nevertheless, the examples yield shared concerns about the locus of security judgements, the responsibilities of private companies, and the infrastructure of data-exchange. The notion of the chain of security can help address these concerns by mapping quite precisely how suspicious transactions materialise and enable security judgements. The purpose is not to suggest that this concept should replace other important analytical notions, like security expertise. Instead, the purpose is to add a possible thinking tool to the toolbox of materialist engagements with security studies.

At the intersection between STS and IR

Following the trajectory of a suspicious transaction as it materialises across the chain of security, I argue, offers a helpful thinking tool to analyse security expertise across public and private domains. I have illustrated this by following the life of a €326 transaction as it was translated from routine wire transfer to court evidence. This final section draws out how the notion of the chain of security aims to contribute to academic debates at the intersection between STS and IR. Specifically, it builds upon, and hopes to push forward, three strands of debate.

First, the approach focuses analytical attention on practice across public and private domains, but moves beyond the emphasis on background knowledge and routines in the literature that brings notions of practice to IR.Footnote 72 In this literature, practice is often understood as a ‘routinised type of behavior’ through which actors ‘create and maintain social orderliness’.Footnote 73 Routinisation depends on unspoken ‘background knowledge’.Footnote 74 However, in contemporary security practice, background knowledge is often not settled. Regulation is relatively new and designed to remain flexible. Professionals are required by law to remain proactive, in order to anticipate the changing methods of potential terrorists. Companies like Twitter and banks have substantial discretion to make independent decisions on what they deem to be suspicious, and when to close accounts. They are encouraged by the regulator to deploy continually modulating and forward-looking strategies to identify suspicious transactions, accounts, or statements.Footnote 75 In this sense, security knowledge is often not settled, in the background, routine, and unspoken. Instead, it is formed in a situated and subjective manner, across public and private spheres.

Indeed, it is at the point of practice that regulation is given meaning and made to act upon the world.Footnote 76 As Annemarie Mol has argued in relation to health care, there is a difference between ‘effective treatments’ and ‘treatment effects’.Footnote 77 The same may be said for policies: goals change and shift as the broad policy ambitions of counter terrorism are put into practice, generating unexpected interpretations, extensive professional efforts, and societal (side-)effects. This approach steers away from notions of habitus or hierarchies, whereby bureaucratic implementations become considered as driven by preconditioned professional outlooks or agendas.Footnote 78 Instead, it foregrounds the processual nature of knowledge formation, that – in the security realm – is understood as ‘creative and constructive’, rather than routine and ‘habitual’.Footnote 79 It is not simply the case that (policy) ends are elusive, broadly formulated and malleable, it is also the case that ends do not necessarily ‘drive action’. Instead, power is exercised when actors ‘search for grip on situations’.Footnote 80 This is illustrated by our example of the €326, which materialises as suspicious when security actors search for grip on the complex political problem of so-called foreign fighters.

Second – and consequently – it is useful to distinguish between knowledge and judgement in order to grasp situated security decision-making beyond the routine. Security practices involve difficult, disputed, and deliberative judgements.Footnote 81 Decisions to report a transaction or freeze a money transfer are never fully automated, but generated through (re)iterative processes of datamining and deliberation. This involves an understanding of security judgements as dispersed and dependent on ‘distributed agency’.Footnote 82 In a public statement for example, Twitter emphasised the complexity of judgements concerning identifying and closing terrorism-related accounts, and said: ‘there is no “magic algorithm” for identifying terrorist content on the internet, so global online platforms are forced to make challenging judgement calls based on very limited information and guidance’.Footnote 83 As Anne Loeber has shown, professional policy implementation is best understood as a mode of practical knowledge where there is ‘neither pre-set goal … nor … fixed and stable criteria by which to assess the correctness of a judgement’.Footnote 84 This is also the case with financial transactions reporting which, as we have seen in the previous section, encourages the deployment of flexible and subjective indicators.Footnote 85

The concept of situated judgement as developed by Luc Boltanski and Laurent Thévenot is fruitful to capture and analyse the operations professionals perform and the moral claims they make when rendering judgement.Footnote 86 How do professionals classify a novel case within existing policy templates and orders of worth? What arguments of moral justification do they use when deciding to (not) report a transaction or (not) pursue a case? Boltanski and Thévenot have suggested that putting policy into practice is never a mechanistic following of a rule, but a subjective and situated process, with outcomes that vary. ‘When one pays attention’ to this moment, one sees much more than ‘the application of a rule’. Instead, one sees an unchartered field of what they call ‘situated judgement’, understood as ‘the confrontation between different forms of judgement expressed by the different actors implicated in the policy’.Footnote 87 The notion of situated judgement is a promising avenue to theorise the ways in which professionals classify concrete cases, appeal to rules and norms and enact the practical meaning of an overarching policy or principle. How do professionals analyse, deliberate, and decide on the normal, the abnormal and suspicious? How do they inscribe transactions with meaning, and how do they doubt, deliberate, and judge borderline cases?

An important element in this context is the interface between professionals and algorithmically-driven software systems that help them spot abnormalities.Footnote 88 It has been well documented that software technologies play an important role in suspect transactions analysis.Footnote 89 Algorithms have the capacity to analyse large digital datasets and identify abnormalities and deviant patterns. They increasingly ‘create the conditions of possibility’ for security knowledge.Footnote 90 However – and in contrast to the more sensational claims in the literature – algorithms do not deliver fully automated security judgements. They need instructions concerning risk appetites, patterns, and thresholds. Furthermore, software systems are integrated into wider professional environments, leading to processes of appropriation that are situated and to some extent unpredictable.Footnote 91 Professional deliberations (often) take place about the significance and interpretation of algorithmically-generated ‘red flags’, and the right follow-up actions in terms of reporting or freezing. The production of security knowledge, in this sense, can be seen as an interplay between human and machine reading.Footnote 92 This approach steers away from grand claims concerning the independent agency of algorithms, in order to focus on what Louise Amoore and Volha Piotukh have called the ‘little analytics’.Footnote 93

Finally, the notion of the chain of security embraces Isabelle Stengers’s search for a mode of critique that does not seek to ‘denounce’, but that, instead, seeks to ‘think with’ the processual way in which orders, identities, and facts become established.Footnote 94 Stengers invites us to ‘follow’ the contingent process that bring (scientific) orders into being, ‘without either ratifying or denouncing them’.Footnote 95 She seeks to proceed with a certain reverence for the object she follows: so as to ‘try to open’ its ‘established identity’ for critical thinking.Footnote 96 In this vein, the thinking tool of the chain of security seeks to follow the sequenced process of referral and (re)iteration underpinning security facts (such as closed accounts, frozen transactions, and court sentences). In doing so, it seeks to think with professionals, using their own doubts, challenges, and hesitations as anchors of (public) critique.

Conclusion

This article has developed the notion of the chain of security as a thinking tool to analyse and critique the formation of security knowledge and judgement across public and private domains. The article followed the life of a €326 wire transfer to Turkey, in order to analyse the professional processes and dilemmas at each link in this chain. Clearly, a security chain is not always linear: chains may be recursive, bungled, even circular. However, with this example I have started to unpack the ways in which financial data(sets) are carved off, reported, shared, and combined, to enable security interventions. As I have argued, the promises of the concept of the security chain are conceptual, empirical, and normative. Conceptually, it moves the study of security knowledge beyond notions of the routine, in order to understand the creative and sequenced mode of security judgements across public and private spheres. Here, we come to understand security as a mode of practical knowledge that is not purely or primarily driven by ostensible policy ends, but which exercises power at the point of practice. Empirically, the approach fosters long-term, ethnographic engagement with security professionals, which is often missing from current practice-based approaches to international studies.Footnote 97 Normatively, the approach takes seriously the modes of professional judgement at each link of the security chain: it seeks to critique without judging. It entails an agenda of critique that follows rather than denounces established categories.Footnote 98

In The Making of Law, Latour reflects on the different ways in which scientific and legal knowledges are generated. Legal facts are generated through prolonged processes of ‘hesitation and doubt’, ‘so as not to rush to blindingly obvious truths’. Scientific facts, on the other hand, require formulation and judgement through the strict procedures of a discipline. ‘Impassioned scientists, having promoted their object as much as possible in their articles, leave it to history, … and thus to future scientists, to judge whether they were right or wrong in making a particular assumption.’Footnote 99 Different from law and science, security entails its own kind of knowledge, of a specific, unchartered kind. Security knowledge resonates with science, law, and finance. Yet security has a specific temporality oriented toward urgency and preemptive action.Footnote 100 This means that the practices of knowledge through which security claims are produced are less routine, and more speculative. In the field of security, perhaps even more than other practical fields, policies are controversy-driven and knowledge claims are continually contested. Following the life of the suspicious transaction across a chain of security translation promises to help analyse how security knowledge is claimed, generated, and (un)settled in practice.

Acknowledgements

Three anonymous readers for Review of International Studies are thanked for their critical comments, which helped strengthen this piece. The article greatly benefited from discussions with colleagues, including Louse Amoore, Rocco Bellanova, Luc Fransen, Marlies Glasius, John Grin, Beste Işleyen, Francisco Klauser, Polly Pallister-Wilkins, Sven Opitz, Darshan Vigneswaran, and colleagues of the Transnational Configurations, Conflict and Governance Research group. Special thanks to Annemarie Mol for her support of this project. Pieter Lagerwaard provided research assistance. This article is part of the European Research Council project: FOLLOW: Following the Money from Transaction to Trial (ERC-2015-CoG 682317).