INTRODUCTION

West Africa has now been widely documented as a trans-shipment point for illegal drugs, most notably cocaine from Latin America (Ellis Reference Ellis2009; UNODC 2011b; WACD 2014) at one point it was claimed that up to one quarter of all of Europe's cocaine was transiting the region, the total value of which exceeded the budgets of many West African countries (UNODC 2011a). No country received more attention than Guinea-Bissau, dubbed a ‘narco-state’ by journalists, analysts and senior United Nations officials alike (O'Regan & Thompson Reference O'Regan and Thompson2013). This article seeks to trace the evolution of drug trafficking in and through Guinea-Bissau, and by doing so, demonstrate that while the ‘narco-state’ label may provide a broad descriptive tool, it is neither analytically useful nor necessarily accurate.

In addition, while a growing body of academic literature has argued that drug trafficking is playing an increasingly important part in politics in West Africa (Ellis Reference Ellis2009; Alemika Reference Alemika2013; Aning & Pokoo Reference Aning and Pokoo2014; Felbab-Brown Reference Felbab-Brown2015), there is a surprising lack of concrete evidence. The discussion has proceeded in generalities, rather than in a more detailed understanding of how the current position evolved or how to conceptually understand it. This paper, which provides a more granular analysis of the trafficking economy of Guinea-Bissau, reveals it as an elite network with mafia-like attributes.

Comparative studies of mafia groups describe them as ‘an industry which produces, promotes, and sells private protection’ (Gambetta Reference Gambetta1996: 1; see also Varese Reference Varese2001). In every transaction in which one party does not trust the other, and in which the state is not available to enforce broken contracts – either because it does not exist, is not strong enough, or because the transaction is illegal – protection becomes a commodity in its own right (Skaperdas Reference Skaperdas2001). This protection thesis has also been used in a number of recent cases of illicit activity in Africa and is a potentially powerful tool to analyse the use and application of violence to protect illicit resource flows (Shaw & Mangan Reference Shaw and Mangan2014; Shortland & Varese Reference Shortland and Varese2014; Tinti et al. Reference Tinti, Shaw and Reitano2014). Past work on shadow, felonious or predatory states, ‘warlords', ‘big men’, or what Reno has dubbed ‘violent entrepreneurs' (Reno Reference Reno, Cockayne and Lupel2011), sought to understand the application of violence (or the threat thereof) in order to protect and/or enhance access to resources by those acting for private as opposed to collective interests (Reno Reference Reno1998; Bayart et al. Reference Bayart, Ellis and Hibou1999; Bayart Reference Bayart2009; Utas et al. Reference Utas, Vlassenroot, Perrot, Mynster Christensen and Arnaut2012; Ellis & Shaw Reference Ellis and Shaw2015). Given the illicit nature of the cocaine trade and the absence of other economic avenues, this description is particularly apt in Guinea-Bissau.

In Guinea-Bissau, protection has been supplied by a small network within the country's elite. That protection, however, is not related to the enforcement of a contract engaged in by others, but the exchange of a ‘fee’ to protect the movement of illicit goods through the country. The ability of the elite network to offer protection derives precisely from the fact that the key institutions of the state, including notably the justice system, matter little, and are unable to mount a response. This is not because of the corrupting influence of narcotics, but because of the badly eroded nature of the institutions (ICG 2008). This is not, then, a ‘narco-state’, if that definition includes the subversion of the state institutions by drug barons at multiple levels,Footnote 1 as drug trafficking in Guinea-Bissau has seen few, if any, resources flow to lower levels of the state, or to the more cohesive military. This is mainly because state institutions, while bearing the requisite descriptive labels (police, customs, magistrates, etc.), do not perform these functions in a systematic, organised or effective way. Rather, it is the actions of a relatively small elite network that has aimed to control an illicit resource flow from which they have profited; the profits from trafficking have been largely confined to that small group and their immediate supporters. Conflict within the elite has centred around access to the resources that this has generated. By contrast, there has been little conflict over, or involvement in, drug trafficking by the broader populace.

In Guinea-Bissau then, what could be termed the ‘political economy of protection’ – managed by an elite protection network – can be described as the set of transactions entered into over time by an elite group of often competing individuals for the purpose of ensuring the facilitation, sustainability and safety of a set of illicit activities.

Much has been made of the role of the military as an institution in Guinea-Bissau in controlling drug trafficking. In fact, the evidence suggests that the military was only one actor – the others being politicians (although with strong connections to the military), and also a group of entrepreneurs who played an important role in linking traffickers and political and military actors. It was one of the country's most significant (and most destructive) Presidents, Nino Vieira, who made the first connections with drug traffickers. The military may have evolved into the ultimate protectors, but it was the civilians who made the initial contacts. This was never a static set of relationships: it was a network of protection that evolved over time, depending on need and the unfolding politics of Bissau.

Significantly, the evolution of protection networks for illicit activities within and/or connected to states has been little studied elsewhere in Africa, and so this analysis has a wider set of implications. Consistent with studies of mafia groups in other contexts, what this analysis of Guinea-Bissau appears to show is that those who are able to protect a criminal market with violence will ultimately seek to control that market; to become the first point of contact controlling the transactions themselves rather than just receiving a protection (or transit) fee. As the military in Guinea-Bissau was neither experienced nor well placed to adopt this role, this ultimately led to the unravelling of the network.

The work presented here is the result of numerous visits to Guinea-Bissau since 2003, with the last in June 2014, in the days after the election of a new government. Over this period over one hundred interviews with a range of individuals, including military officers, civil society representatives, law enforcement officials, judges, politicians, religious leaders, community workers, journalists and international officials were conducted, most of them in 2005, 2007, 2012 and 2014.Footnote 2 The methodological approach follows that of other studies of illicit activity and organised crime; a combination of reviewing secondary and primary source material, combined with extensive discussions with individuals close to or involved in illicit activities (see Reno Reference Reno1998; UN Centre for International Crime Prevention 2000; Varese Reference Varese2001). Information has been cross-referenced between these sources, with the general requirement that key elements of the story be corroborated by several sources. The core elements of the unfolding narrative have however also drawn on key sources within Guinea-Bissau and externally, including local and foreign investigators with access to a wider range of data. Of course, given the sensitive nature of the topic, conflicting accounts remain and where this is the case, an indication is given to the reader.

POLITICAL FRAGILITY AND CHANGING ELITE INTERESTS

Guinea-Bissau is located on the West Africa coast, sandwiched between Senegal and Guinea with a population estimated at just over one million. The independence of the country from Portugal in 1974 was a defining event in the anti-colonial struggle in Africa (Chabal Reference Chabal, Chabal, Birmingham, Forrest and Newitt2002). The foundations of the new state were fragile from the beginning. The destruction wrought by the liberation war meant there was no organised state on which to build. The victorious Partido Africano da Independência da Guiné e Cabo Verde (PAIGC) was the dominant political force, and internal party patronage networks quickly began to dominate those economic resources that were available (Forrest Reference Forrest, Chabal, Birmingham, Forrest and Newitt2002). In a context of relative resource scarcity, and the failure to establish a working state, infighting within the ruling elite was intense; since independence no elected President has been able to complete his term in office. All but one were deposed by the military, and the exception, Nino Vieira, was assassinated by soldiers (O'Regan & Thompson Reference O'Regan and Thompson2013). The defining feature of politics in Guinea-Bissau has been conflict and chronic instability (Roque Reference Roque2009; Vigh Reference Vigh2009).

Understanding what has driven that instability must centre on the coalescence of elite networks around economic interests. Since independence, the Bissau-Guinean elite has been constituted by a tight web of political, military and business figures who have reconstituted themselves ‘in fluctuating and ambiguous alliances' (Embaló Reference Embaló2012: 253). Their interests have centred around securing economic opportunity for themselves, as opposed to the state.

That economic opportunity has been, by definition, externally focused with little, if any, linkage into the interior of the country. The colonial state in Guinea-Bissau, as Joshua Forrest has pointed out, lagged significantly behind other colonies in the ‘routinisation of social subordination’, particularly in rural areas (Forrest Reference Forrest2003: 10). Additionally, while the PAIGC had maintained significant networks across the country, these had linked with local forms of organisation and have eroded after independence (Independent radio journalist 2012; Church leader and human rights activist 2014). The long war for independence began a process of ‘deagrarianisation’ and ‘depeasantisation’ that accelerated after 1974 (Temudo & Abrantes Reference Temudo and Abrantes2013). Attempts at state control over agricultural production failed, and imports to the small urban elite led to growing external debt.

What the liberation war did do, however, was to place the military and the war veterans at the heart of a system of externally focused economic accumulation. The new military, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of the People (FARP), exerted considerable influence, becoming a refuge for an ageing cadre of fighters, many of senior rank, who had participated in the liberation war and who were located in or close to the capital, Bissau. While having a relatively strong institutional structure in the two decades after the ending of the war, this was badly eroded after successive funding crises, resulting in a much looser militia type organisation.

From the founding of the independent state, and as political crisis followed political crisis, the government's control over the territory shrank inwards towards the capital. In the process, the leadership became increasingly reliant on external sources of funding, while ordinary people, particularly in the countryside, saw less and less evidence of government. In ‘a state organized around strategies of material survival and personal gain’ (Interpeace 2010: 13), the two trends of state contraction and reliance on external resources were mutually reinforcing. As a recent analysis concludes: ‘In this context, as the patrimonial state strengthened, the modern state vanished, and authority [within the elite network] became the best way for personal enrichment’ (Pureza et al. Reference Pureza, Roque, Rafael and Cravo2007: 17).

Post-war economic policy then foundered quickly on individual interests and personal accumulation. There were few incentives to bolster the linkages between state and citizenry, when institutions barely existed and positioning within the elite network served a gatekeeping function and thereby a source of resources for a small group of connected individuals (Kohl Reference Kohl2010). By the early 1980s, high levels of external debt and external pressure forced a period of structural adjustment. But the way in which this was managed in rural areas, reinforced patterns of elite accumulation and, ironically, led to an even greater divide between the ‘powerholders' in Bissau and the countryside (see for example the results of focus group discussions in Reitano & Shaw Reference Reitano and Shaw2014).

DRUG TRAFFICKING: ROLES AND RESPONSIBILITIES

Structural adjustment orientated the politico-military elite even further towards a reliance on non-domestic resource flows. These resources began to dry up by the late 1990s, which introduced a new fragility into Guinea-Bissau politics as, over time, a series of competing protection networks coalesced around a new and illicit flow: cocaine from Latin America. ‘The search for easy money and reliance on external financial resources outside the country contributed to the gradual criminalization of state institutions and members of the power elite’ (Kohnert Reference Kohnert2010: 3).

Interviews with serving military officers in Guinea-Bissau suggest that since the civil war, from 1998–1999, tensions within and between the military and political elite grew; these conflicts were not a clear-cut standoff between soldiers and civilians. Tensions were overlaid by a network of contacts between civilian and military officials, with ‘politicians keeping strong links to the military and vice versa’ (Independent radio journalist 2012; Serving military officers 2014). Consequentially, despite the fact that Article 20 and 21 of the 1993 Constitution stated clearly that the military should be apolitical, politicians reached out to their own networks within the military and ‘these gathered around illicit trafficking, regardless of who wore the uniform and who did not’ (Serving military officers 2014). The elite group is a network of associates – some in the military and some in the political establishment. This elite network, however, has been riven by internal conflict, based on competing and often changing sets of interests (Serving Minister 2007; Independent Journalists 2012).

Three sets of actors were key in the development of the trafficking economy in Guinea-Bissau. The first was the Latin American traffickers themselves. While the traffickers were decisive actors in the sourcing of illicit cocaine, they did not and could not create the trafficking economy in Guinea-Bissau on their own. They relied on a second small group of interlocutors; entrepreneurs who had had previous contacts with illicit drug traffickers in Europe and Latin America, and at the same time were close to political power.

The third group is, of course, the Guinea-Bissau politico-military elite. Desperate to find new sources of resources to replace external flows that were drying up in the late 1990s, the Bissau elite were open to approaches that would bring new money. At the centre was President João Bernardo ‘Nino’ Vieira, the larger than life, three-times President of the country, who ruled in total for a period of nineteen years.

The evolution of drug trafficking in Guinea-Bissau is based on the connections and inter-linkages between these three actors. This analysis shows that while the impact of drug trafficking in the country has been extensive, in fact the defining role was played by a nexus between relatively few competing individuals, and the vast profits to be earned by the cocaine trade exacerbated already fractious relationships and pre-existing organisational divisions (Staniland Reference Staniland2014).

It is important to note that before the advent of the drug trafficking economy, a series of actions aimed at acquiring profit tore the politico-military elite in Bissau apart and resulted in a short-lived, but brutal civil war. The roots of the civil war lay in the trafficking of weapons for profit to separatist fighters in the region of Casamance over the border with Senegal. While the causes of the region's struggle for independence need not detain us here (and can be found in Foucher Reference Foucher2011), what is important is that the elite in Bissau used the opportunity at a time when they had become desperately short of independent sources of funding (Independent journalists 2005). Two military officers interviewed in Bissau stated it simply: ‘People in the military and politicians were economically vulnerable. They needed money. That was to pay themselves and supporters and engage in political [campaigns]. It is that easy to explain’ (Serving Military Officers 2014). As a result, arms were sold to the separatists for profit.

The engagements of elements of the political and military elite were to have a decisive impact on the country. When reports that Guinea-Bissau had been supplying arms to the separatist movement became public, President Vieira was forced to concede a parliamentary inquiry. In response to the emerging scandal he dismissed the armed forces Chief of Staff, General Asumane Mané. It would later emerge that Vieira had himself been deeply involved in the trafficking of arms. Mané did not accept his dismissal, and, relying on simmering tensions within the politico-military elite, he mobilised the army and much of the populace behind him (Rudebeck Reference Rudebeck1998).

Ironically, given that he himself had been involved in the trafficking of arms, Vieira was forced to rely on Senegalese and then Guinean intervention. Mané emerged victorious after a brutal civil war that left important scars within the elite. Vieira fled to Portugal, his political career apparently over.

ORIGINS AND ENTANGLEMENT

In Portugal, Vieira renewed his contacts with then President Lansana Conté of neighbouring Guinea. Guinean armed forces had been instrumental in providing Vieira military muscle during the civil war, and relations between the two men went back some way. Conté had been based in then Portuguese Guiné during the liberation war and cooperated closely with Vieira, at the time a powerful PAIGC military commander in the south-east. Conté later sent troops to Guinea-Bissau to fight on the side of Vieira's ailing government (Arieff Reference Arieff2009). Political connections forged between Conte and Vieira appear to have been decisive in introducing the cocaine economy to Guinea-Bissau.

While the exact nature of the engagements with Conté around drugs remains unclear, what does seem to be the case is that in his circle were at least two figures, a prominent local businessman (whose name is withheld for legal reasons) and Francisco Barros, a Cape Verdean. The two had, respectively, lived for several years in Spain and Portugal where they appear to have been involved in drug trafficking, and had contacts with both Latin Americans and European crime figures (Guinea-Bissau civil society leaders 2012; Guinea-Bissau civil society leaders 2014; Judicial Police officials 2014). Little is known of the first businessman, although he is said to have remained a consistent figure in drug trafficking in Guinea-Bissau until today. Several sources indicate that he made the initial connection between Nino Vieira and Colombian traffickers, then present in Conakry (Civil society and human rights activist 2014; Independent journalists 2014; Portuguese diplomats and security officials 2012). Barros (widely known as ‘Chico’) is said to have a violent history and to be more of a ‘bagman’ than a major crime operator, but was on the US Department of Treasuries' top ten list of criminals in June 2014 (Guinea-Bissau law enforcement officials 2014; Senior US law enforcement officials 2014). Both men are alleged to have some connection to the son of Conté, who appears to have been involved in a wider set of illicit activities, using the patronage and protection provided by his father's position.

The role of the entrepreneurs in making the ‘connection’ is critical. It is these figures who, ironically, appear to have survived the longest, where violent assassinations have affected almost every military and political leader who has become involved in the trafficking business. There is evidence that a series of other ‘entrepreneurs' have also been implicated in approaching and facilitating the introduction and maintenance of drug trafficking in the country. This includes a shadowy French national who maintains a hotel in Bissau, a prominent Lebanese businessman who runs a garage, and a Senegalese businessman with strong connections to Bissau (Ex-UNODC official 2014; Local journalists 2014). The key point about the entrepreneurial group is that through their external connections to traffickers and their links to the fractious Bissau elite they acted as intermediaries between those who sourced the drugs and the local protection economy (UNODC officials 2012; Guinea-Bissau law enforcement 2012 and 2014).

Why was Vieira himself interested in involvement in drug trafficking? There is some suggestion that Latin American traffickers had already made contact, through a similar set of entrepreneurial figures, with President Conté in Guinea; indeed, the fact that drugs have transited Guinea with what appears to be high-level protection suggests this is likely (International law enforcement officials 2005). What Vieira sought was resources with which to engage in a political comeback. He made that connection in an environment ‘that was already conducive to drug trafficking’ (Civil society leader and human rights activist 2014).

What the introductions around drug trafficking also brought were the resources to buy the allegiance of a key figure in the military: Vice Chief of Staff General Batista Tagme Na Waie. There is evidence that Tagme Na Waie made several trips to Conakry, paving the way for Vieira's return. If true, this must have been, at best, a tenuous association; Tagme had fought against Vieira's regime during the civil war. In the increasingly factional and fragile politics of Guinea-Bissau, however, what appears to have emerged was an ‘alliance of convenience’ (Civil society leader 2014). Vieira could provide access to resources, while Tagme would pave the way for the return of the former President (Guinea-Bissau law enforcement officials 2014). Removed of a prevailing ideology or political principle, this was a cold-hearted marriage, calculated to achieve power.

THE RISE AND FALL OF AN ELITE CRIME GROUP

Vieira's rise to President is closely aligned with trafficking of cocaine through the country.Footnote 3 A revolt by soldiers over pay led to the killing in October 2004 of the then chief of staff Correia Seabra, who had been appointed by President Kumba Ialá. Kumba Ialá was overthrown by Seabra, paving the way for elections in March 2004. Those elections brought Carlos Gomes Jr. to power as Prime Minister, and presidential elections were held the following year. Whether or not Tagme assisted behind the scenes is unclear, but in a dramatic political comeback Nino Vieira won presidential elections in July 2005 in a well-funded campaign (Independent journalists 2012). In the meantime, Seabra had been replaced by Tagme, allowing for an alliance of the military and the new political order to traffic narcotics (Civil society leader 2014; Guinea-Bissau law enforcement officials 2014).

In the months after Vieira assumed power, several observers noticed an influx of Latin Americans into Bissau. This was combined with a parallel influx of high-range vehicles, including several Hummers, noticeable in the small town's rutted streets and driven by prominent military and some civilian officials. Vieira himself acquired a Hummer. These were the ‘first signs' that funds appeared to be flowing to certain people within the elite.Footnote 4

More concrete evidence that the source of the sudden increase in elite wealth stemmed from drugs occurred in late 2005. Near the village of Quinhamel, some 30 kilometres west of Bissau, a local fisherman scooped up a large number of packages of white powder from the sea. Initially, the fisherman used the powder as food seasoning and then as fertiliser until, in what became known as the ‘fishing incident’, a plane arrived in Bissau, dispatching three men, who with a military escort, tried to buy it back. The ‘powder’ appeared to have come from a ship that had sunk in the area in October 2005. The three individuals were subsequently arrested by the Judicial Police, who also seized €700,000. They were released without explanation a few days later after an apparent intervention by the Presidency (UNOCHA 2007; Civil society leaders 2007).

In 2006, as trafficking increased, the hard-pressed Judicial Police made a large seizure of 674 kilogrammes of cocaine in Bissau, following a shoot-out. Two men were arrested, both with Venezuelan passports, as well as laptops, firearms and radios. The drugs, worth an estimated $39 million, were placed in a safe at the Ministry of Finance and then disappeared. ‘Some soldiers came, demanding that they be able to count the drugs and we never saw them again’, a treasury official reported to the UN humanitarian news agency, IRIN, shortly afterwards (UNOCHA 2007). Government officials later claimed that the drugs were destroyed, but there is no evidence that this did in fact take place (UNODC Officials 2012; Guinea-Bissau law enforcement officials 2014).

The small contingent of poorly resourced Judicial Police – there were never more than 10–15 officers and they seldom had money for basics such as fuel – continued to investigate despite threats and intimidation. On 21 August 2007, based on information that had been received, they raided a warehouse, arresting two Colombian nationals: Luis Fernando Aranco Mejia and Juan Publo Camacho. The warehouse had been rented by a local businessman in Bissau, the first of the ‘entrepreneurs' mentioned above.

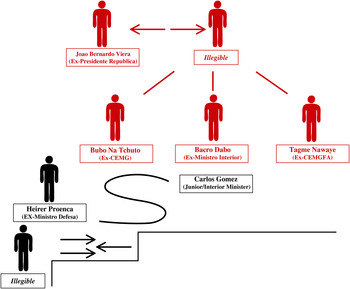

What is perhaps most remarkable about the incident is a white-board found in the office of the warehouse. On it had been mapped out key figures within the government of Guinea-Bissau, including deputies in the National Assembly, the Chief of the Army, the President of the Supreme Court and special advisors to the President, the connections between them, and what appears to be a rough record of payments made. In the bottom corner of the board, in red and partially erased, is a set of stick figures, connected by arrows. These figures appeared to be key to controlling the drug trade.Footnote 5 A sketch of this drawing is reproduced in Figure 1.

Figure 1 A representative sketch of part of the white board seized from a warehouse where Latin American traffickers were arrested in Bissau.Footnote 6

The arrest of the Colombians took a bizarre twist when the public prosecutor released them on bail, using money (€95,000) that was seized during the arrest. ‘They used evidence as bail money, it was a crazy thing’, a member of the Judicial Police recalls (Judicial Police 2012). To their credit, the Judicial Police who had made the arrest, refused to release the suspects. The Prime Minister, Aristides Gomes, intervened, arguing that the men should be released and the ‘bail’ money, as well as 1·5 million CFAs also confiscated in the warehouse being forfeited to the state. The Colombians were released and departed Bissau immediately (Guinea-Bissau law enforcement officials 2012 and 2014; Independent journalists 2012).

One year later, on 20 July 2008, the Judicial Police again made three arrests,Footnote 7 this time at the airport. Information had been received that a small executive jet had carried drugs into the country. The Judicial Police and Customs were prevented from inspecting the aircraft, and military personnel, it is alleged, unloaded some 500 kilogrammes of cocaine. The plane, however, encountered technical difficulties and was forced to stay at the airport, where it was still parked in June 2014 (O'Regan Reference O'Regan2014).

It has been shown that the plane was registered with Africa Air Assistance, the same Senegalese-based company, with offices also in Bissau, that was linked to the notorious November 2009 crash of a Boeing 727 near the northern Malian city of Gao (O'Regan Reference O'Regan2014). The plane was alleged to have carried a large consignment of drugs. African Air Assistance is linked to a Senegalese businessman, Ibrahima Gueye, apparently a regular visitor to Bissau. In the classic mould of the ‘entrepreneur’, he appeared to be making links between Latin American traffickers and the Bissau elite, and paying them for their ‘protection’ (Guinea-Bissau law enforcement official 2012).

The stick figures detailed in the corner of the board in the warehouse, detailed above, outlined what was, in effect, a criminal conspiracy at the core of the Bissau elite. This consisted of four key members, as well as a fifth figure. The four stick figures on the board were: President Vieira himself; the Minister of Defence, Helder Proença; the military Chief of Staff, General Tagwe Na Waie; and the Minister of Interior, Baciro Dabo. Not one of the four would survive. Connected to this group was Admiral Bubo Na Tchuto who, perhaps more than any other figure in Guinea-Bissau, would achieve international prominence for drug trafficking.

The connection between these five men was key to managing what was a burgeoning transit trade of cocaine in Guinea-Bissau. The day-to-day management and protection of drug convoys was provided for by soldiers. The President and the two Ministers provided the high-level ‘protection’, and money from trafficking was distributed to a limited number of other individuals within the state, both civilian and military. What appears remarkable, in retrospect, is how open trafficking and the knowledge that the elite were involved was at the time. There was a building spree in Bissau and top-of-the-range cars became ubiquitous on the streets (Civil society leaders 2007; Independent journalists 2007).

How much money was made at the time is hard to estimate. At least at the beginning, the amounts were not excessive, but these grew over time as the elite group began to understand the trade more effectively (International law enforcement official 2007; UN officials 2007).

A PROTECTION RACKET RECONSTITUTED

Greater understanding of how the system worked brought greater instability, as individuals positioned themselves to access protection money. The tensions within the Bissau-Guinean elite were the result of several historical factors; most prominent was how individuals had aligned with or against Vieira during the civil war period. The alliance of convenience between Vieira and his military chief of staff, Batista Tagme Na Waie, was, as pointed out earlier, fragile. Na Waie for one had been a participant in the military seizure of power from Vieira in the 1990s and had been appointed Chief of Staff after the October 2004 murder of his predecessor, Verissimo Correia Seabra (Independent journalists 2012).

In January 2009 Na Waie himself survived an assassination attempt when a military unit that had been assigned to the presidential palace fired on his car. Less than two months later, Na Waie was killed by a bomb blast in the main headquarters of the Guinea-Bissau military (Civil society leader and human rights activist 2014; Serving members of the Guinea-Bissau Military 2014). While assassinations of senior figures had, of course, occurred in the past – the previous chief of staff, Correia Seabra, being just one example – these had generally been in shoot-outs or during open conflict.

In the case of Na Waie, the means of assassination was a bomb placed strategically under the stairs of the military headquarters. This indicated a degree of sophistication that had not previously been used, and that the Guinea-Bissau military itself lacked (Foreign law enforcement official 2012; Independent journalists 2012). It is almost impossible to corroborate the details of who may have been responsible here. Nobody has ever been held to account. What may be a plausible story, which was related in different forms, was that Na Waie was killed by Latin American drug traffickers because ‘he was protecting Nino too much’ (Civil society leader and human rights activist 2014) and that the two, despite their fraught past relations, ‘were becoming conscious that the drug dealers were getting too much power’ (Independent journalists 2012). There also seemed to be an indication that both Vieira and Na Waie may have sought a greater control of the trade, rather than simply receiving a fee for protecting the drugs in transit (Foreign law enforcement official 2012; UNODC officials 2012).

Harder to prove is the assertion that the drug traffickers read the complex internal politics of the Bissau elite and targeted Na Waie, knowing that the ultimate victim would be Vieira. It is true that Na Waie and Vieira were more ‘allies in profit’ than long-term strategic partners. Given their histories, there could not have been much trust between them. Killing Na Waie automatically led fingers to be pointed at the President himself and tension escalated quickly in the capital. Military officers close to Na Waie, who were quick to remind others that it had been Na Waie himself who had facilitated the return of Vieira, acted quickly (Serving military officers 2014).

A group of soldiers, loyal to the assassinated Chief of Staff, attacked the President's house shortly afterwards. The army's official spokesman announced that Vieira had been implicated in the killing of Na Waie. What is clear from all accounts is that Vieira was brutally beaten before being killed. A video of the corpse shows a badly injured body that appears to be Vieira lying on the autopsy table surrounded by soldiers.Footnote 8

The killing of two prominent members of the country's drug trafficking protection racket was, for a period, enormously destabilising. The diagram that the Latin American traffickers had drawn in their warehouse had included four key figures. Now, two of the most prominent were gone. The remaining two were dead in four months.

After the killing of Vieira, the military had emphasised that this had not been a threat to the constitutional order and that elections for a new President would be duly held on 9 June 2009. Dabó, who had been a close ally of Vieira, resigned from the PAIGC and put himself up for election as an independent candidate. The day before electioneering was to begin a group of soldiers shot their way into his house and killed him. Proença met a similar fate, reportedly being murdered on a road outside of Bissau.

The motives for the killings appear to lie either in an attempt to remove two players who apparently might have been in a position to shed light on who Vieira's killers were, or they were a complicated bid by senior elements within the military to acquire full control over the trafficking protection enterprise.Footnote 9 Or, the reason for their murders may have been a combination of these factors. In the murky world of the politico-military elite, several key military figures had positioned themselves to take control of the drug trade. Whatever the truth, it was in this period that elements within the military assumed much tighter control over drug trafficking.

A COUP AND A HALF COUP

The end of Vieira's criminal quartet introduced a period of profound instability, even by the standards of Guinea-Bissau. The period after the 2009 elections saw the military assume a dominant position – by mid-2010 civilian politicians were often only playing the role of figureheads (Civil society leaders and journalists 2012).Footnote 10 The rise of the military in this way, and the fragility associated with its rule was closely associated with drug trafficking.

The degree to which control shifted more clearly to the military is perhaps most clearly demonstrated during the tenure of Carlos Gomes Jr. as Prime Minister, from late 2008 to end 2011. Several interviewees insisted that anyone in a position of political power in that period must have been implicated in some way in drug trafficking. Indeed, rumours persist of Gomes Jr. himself having had some involvement (he was also listed on the Latin American whiteboard, although not as part of the core group), or, at the very least benefiting from the trade. At the centre of that discussion stood the relationship between Gomes and the military. A classified State Department cable put it succinctly at the time: ‘There is an active debate among local observers … is the Prime Minister a hostage or an accomplice? The truth seems to be that he is a bit of both’ (Public Library of US Diplomacy 2009).

If Vieira had been a driving force in establishing the drug economy, after his death in 2009 the politics of Bissau was characterised by a series of weak civilian leaders, presided over by a fragmented and internally contested military. This fragmentation amongst the military high command is illustrated by an almost comic set of events from 2009. A key player in these is none other than Admiral Bubo Na Tchuto, the fifth figure on the Latin American whiteboard.

Na Tchuto had been linked to the original Vieira drug trafficking quartet. In 2008 he had been involved in a failed coup d'etat that has remained shrouded in mystery. Whether it was a similar attempt to undercut the control of Vieira and Na Waie of the drug protection racket is unclear, but he was forced to flee and found refuge in Gambia.

In December 2009, as factions within the military vied for control, and as drug trafficking through Guinea-Bissau appeared to worsen, Rear Admiral Na Tchuto arrived back in Guinea-Bissau disguised as a fisherman. He sought refuge at the United Nations building in Bissau and was accommodated on the basis that no guarantees could be provided that he would receive a safe and fair trial. Several UN staff reported that he spent hours on his mobile phone negotiating directly with a senior military figure, presumed to be then deputy chief of staff, General António Indjai (UN officials 2012, 2014).Footnote 11 UN staff debated internally how to justify the apparent protection of a man widely suspected of being deeply involved in the narco-economy.Footnote 12

The UN, in the end, did not resolve the situation – a faction in the military did. After five months of self-imposed exile in the UN building, on 1 April 2010, a military convoy arrived to ‘rescue’ him – though he was not detained. At the same time, Prime Minister Carlos Gomes Jr. was placed under house arrest. A strange pantomime unfolded at the UN building, as drunken soldiers paraded in front while Bubo (as he was widely called) bade a series of happy farewells, including taking pictures with some staff, before departing (UN officials 2012, 2014).Footnote 13

This military intervention did not remove the civilian government, but greatly weakened it by shifting the balance of power within the military itself; replacing one chief of staff, José Zamora Induta, with another, António Indjai. Bubo, his negotiations having borne fruit, was reintegrated into the (shipless) navy. The ‘half coup’ did not become a full coup by virtue of the fact that the public took to the streets in Bissau, demanding the release and re-instatement of the Prime Minister. Gomes was subsequently released and travelled to Portugal, from which he returned in June to once again take up his position.

The ‘half coup’ was, however, to have important implications for drug trafficking. With civilian control weakened further, the military assumed full control of trafficking operations, using the entrepreneurs initially as an interface with the Latin Americans. Importantly, too, the ‘half-coup’ led to disengagement by international actors, most notably by a European Union Security Sector Reform mission, which had been attempting to professionalise and downscale the country's security forces. The withdrawal was a mistake, as it further reduced foreign oversight over the actions of the military. As in the days of Vieira, Bissau became once more a place of open engagement with drug traffickers and ostentatious displays of wealth (Civil society leaders 2012; Independent journalists 2012; Former politician 2012; UN officials 2012).

By 2011, money from drug trafficking appeared to have seeped across much of the Bissau elite, with increasingly the military, and Indjai at the apex, controlling the tap.Footnote 14 Several developments, however, suggested that reform was in the air. Growing pressure, including a series of UNODC reports and the implementation of a wider programme of assistance to aid local law enforcement, saw the civilian government take (at least publicly) a stronger line against drug trafficking. The UN Secretary General's report of the middle of that year noted in its opening sentence: ‘The period was marked by positive developments contributing to overall political stability in the country’ (UNSC 2011: 1). In June 2011, Gomes Jr. went as far as to sign a Declaration to fight drug trafficking and organised crime (RGB 2011), although there remained scepticism as to the government's intentions and capacity to implement it.Footnote 15

In December this apparent forward momentum resulted in a list of 200 military officers to be retired. Significantly, earlier in the year, agreement was reached between the Community of Portuguese-speaking Countries (CPLP) and the Community of West African States (ECOWAS) on a roadmap for security sector reform. A bilateral CLCP initiative saw the deployment of a 270 strong force of Angolan military advisors to facilitate the process. In March 2012, in presidential elections, which a UK parliamentary delegation labelled as ‘fair and credible’, Gomes Jr. received just under 50% of the presidential vote (Kemp et al. Reference Kemp, Shaw and Boutellis2013). A run-off was scheduled to be held, but with the other candidate, Kumba Ialá, withdrawing at the last moment with the intention of blocking the electoral process.

In April 2012, on the eve of the election, the military seized power, citing the dangers posed by the Angolan troops. A civilian President, Serifo Nhamajo, who had stood as a candidate and was seen as close to the military, was installed. There is evidence that drug trafficking increased substantially in the wake of the coup. Reports from both people on the ground and several observers indicated that a tarred road running to Bissau was used as an airstrip and that a military landing strip controlled by General Indjai himself was used as drug shipments were brought in (UNODC officials 2012; Portuguese diplomatic and security officials 2012).Footnote 16

ENDGAME

The literature on protection economies makes a distinction between those engaged in the resource-generating criminal activity itself, such as drug trafficking, and those who receive resources for protecting them (Shortland & Varese Reference Shortland and Varese2012). In the case of Guinea-Bissau, as has been argued, a small group of entrepreneurs with political connections were the first to engage in drug trafficking. They bought political and later, military support; conflict within the politico-military elite was related to who received the funds to provide such support.

Protection economies are never static, however, and what seems to occur is that those who provide the protection often move into a position to control the whole market (Skaperdas Reference Skaperdas2001). This is for two reasons. The first is that the provision of protection over time generates resources that provide the wherewithal to do just this, including by ensuring a system of patronage. The second is that economic incentives for including the transaction side of the business (that is, engaging with the traffickers directly) are strong; if profits from protection are good, profits from controlling trafficking are better.

The half coup and coup constituted that process in Guinea-Bissau. Control over trafficking, both the negotiation of transactions and the protection of the movement of drugs, was in the hands of the senior military leadership. The key figures were Rear Admiral Bubo Na Tchuto and Major General António Indjai, and comparing them is a study in contrasts.

Na Tchuto's behaviour, several knowledgeable observers in Bissau suggest, almost always followed the same pattern. He sought to ingratiate himself with those in power: ‘he always manoeuvres to be close to those in power, his strategy is that simple’ is how a prominent civil society leader described his actions (UN official 2014). Indeed, his long-term survival at the centre of the drug trafficking economy, beginning first with Vieira, then exile in Gambia, a return to UN headquarters and, finally, ‘rescue’, tends to bears this out. Speaking to many observers about Bubo almost always draws the same sets of responses: ‘a very stupid man’; ‘he is ignorant about the world’; ‘clumsy but nice’; ‘he is always extremely friendly when I see him’; ‘he often offers to buys us lunch’; ‘he is hardly your typical drug kingpin’ (UN official 2014; Foreign law enforcement official May 2014; Foreign diplomat 2014; UN officials 2014). Indeed, Bubo is described in this period as becoming something of a man about town, dispensing largesse, and, as reported by several people who had contact with him, openly admitting to being involved in drug trafficking; he once publicly stated that the government had asked him to pay public security officials with drug money (Civil society leader 2014).

In contrast, General Indjai is viewed as being much more calculating, ruthless and paranoid about his own security. UN officials reported that, for example, he moved strategically to put his own Balanta men into all military units. He created a large bodyguard battalion that was used only for his personal protection. He was often unapproachable by external parties and dealt through intermediaries, fearing his own security (UN Security sector reform specialists 2012, 2014). Reinforced by the resources garnered from drug trafficking, Indjai became the all-powerful figure in Guinea-Bissau: by 2013 he stood at the centre of a web that controlled the drug trade and its protection.

The changes that had been brought about in the system are subtle but important. This is well illustrated by the details of two other arrests made in April 2013 by US drug enforcement authorities. In this sting operation, two individuals, Manuel Mamadi Mane and Saliu Sissue, travelled to Colombia to meet with traffickers who were, in fact, informants for the US Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA). The two agreed to buy cocaine for €14,000 a kilogramme. They also negotiated on behalf of Indjai, indicating that a cash payment was not required, but instead that 13% of the shipment could be taken as a ‘transit fee’. Those drugs would be sold by the Guinea-Bissau network itself. As a gesture of goodwill, Mane provided a phone number of an individual in Amsterdam to whom €20,000 should be sent (O'Regan Reference O'Regan2014).

What is significant is that the military network in charge had grown from one simply providing ‘transit security’ to one that, by 2012 and 2013, appeared able to negotiate and market drugs itself, including through established contacts in Europe. This apparent sophistication, however, belies the fact that while they may have been competent at the brutal game of ensuring protection at home, the military group under Indjai were comparative amateurs at negotiating international drug deals.

In the past, the messy political arrangement under Vieira, including the fact that local law enforcement still tried to make arrests of traffickers, masked the complex political and resource game being played. External interventions were difficult and considerable doubt remained as to the extent to which the state was involved in drug trafficking. After the 2012 coup, the political pretences were largely stripped away, leaving only a clumsy but violent military network in charge. Greedy, inexperienced and, importantly, increasingly politically vulnerable, Indjai and Bubo were easy prey for international law enforcement efforts.

In the wake of the coup and in the months before Bubo's arrest, there is now also significant evidence that the protection network at the heart of the military had diversified into a range of other illicit activities: most notably the smuggling of people and the illegal exploitation of the country's timber resources. Syrian refugees on false Turkish passports were brazenly marched through the airport in Bissau onto a flight to Europe, leading to the later cancellation of the regular Air Portugal connection to Lisbon (European security and migration official 2014). And, while there had been previous cases, the military appeared to be firmly in charge this time. And, Chinese loggers with permits issued by senior military officers moved with remarkable rapidity across the interior to exploit timber.Footnote 17

Against this background, and whatever its drawbacks, the American operation to arrest and indict both Bubo and Ndjai was a significant event in damaging and exposing the nature of the illicit trafficking economy in Guinea-Bissau. It aimed to entrap Indjai and Bubo through a scheme where DEA agents posing as representatives of the FARC made a request for Indjai to provide arms in exchange for cocaine, which would be stored and trans-shipped through Guinea-Bissau (USDC 2012a). Ever the friendly front man, according to prosecutors, Bubo suggested to the DEA agents that the timing to engage in such activity was very good in the period after the 2012 coup, given who was in charge of the country (USDC 2012b).

The operation was only partially successful. Bubo was lured out to international waters to receive a payment for the transfer and was arrested and extradited to the US.Footnote 18 Some mystery surrounds the reason why Indjai did not also go himself to meet what he believed to be FARC contacts. The most plausible explanation, confirmed by several sources, is that he pulled out at the last minute, suspicious of the transaction – or as a military officer pointed out, ‘his gut was not comfortable’ with it (Serving military officers 2014). It is said that some officers close to him persuaded him that he was too senior to go out to sea to receive a payment. Whatever the truth, the result was that Bubo found himself alone in New York, facing charges – although he subsequently appears to have entered into a plea-bargain, presumably providing additional evidence to bolster the case against Indjai.

In Bissau, the indictment and partially successful operation sent a seismic wave through the elite. Drug trafficking operations were curtailed immediately or confined to storage and there appeared to have been no movement of contraband for a period. The UN and many foreign missions were caught off-guard, as they had no prior knowledge of the operation. Significantly too, the operation also placed more pressure on Indjai to allow the political process to move forward to an election, with the threat of possible arrest hanging over him greatly increasing his own vulnerability.

The DEA operation was also received with a degree of shock within United Nations Integrated Peacebuilding Office in Guinea-Bissau (UNIOGBIS). The new Special Representative of the Secretary General (SRSG), José Ramos-Horta, had been actively downplaying the issue of drug trafficking. This was partly because he believed that its impact had been overstated, and partly because he wished to engage the local elite and could not do that ‘while calling them criminals' (Senior UN official 2014). The operation though, with the clear evidence that Indjai, Na Tchuto and others were willing and able to engage in illegal activities, was a defining moment. Ramos-Horta's statements that drug trafficking was not an issue of concern to Guinea-Bissau softened (Senior UN official 2014). To his credit, the SRSG was central in pushing forward a process of elections and the election of a new reformist government, headed by President Jose Mario Vaz and the reformist Prime Minister, Domingos Simões Pereira.

The fate of Indjai hung in the balance for several months.Footnote 19 The US Ambassador had to be brought in, at the request of the UN SRSG, to say that Indjai would not be arrested, provided that he remained in Guinea-Bissau (Senior UN official 2014). Ramos-Horta, for his part, appeared to believe that keeping Indjai on was better than dispensing with his services in the interests of stability. Several powerful external partners of the new government, however, most notably the European Union, remain adamant that Indjai should be sacked (European diplomats 2014). In September 2014, the new government, under great pressure to reform the security services, followed through and dispensed with the services of the General.

CONCLUSION

The growth of Guinea-Bissau as a hub for the drug transit trade on the West African coast has been widely noted, but seldom effectively explained. The use of the term ‘narco-state’ has been regularly used, although seldom defined, implying that the state itself engaged in the trafficking economy. The reality is much more complex. Guinea-Bissau did not possess a coherent state and it is more accurate to describe control over trafficking as a result of a protection network that evolved within a small elite, increasingly starved of external resources in the wake of the end of the Cold War and structural adjustment policies.

Elements of that elite needed resources to ensure political survival; little attention was paid to whether those resources were licit or illicit. The primary and initial contacts that were made by drug traffickers were by politicians, with a group of entrepreneurs acting as the interface with traffickers. A central figure was the prominent civilian politician, Vieira, who was himself involved in conflict with the majority of the military.

While much has been made of the key role of the military, this role evolved over time. Trafficking began with contacts between elements of the political elite and a group of entrepreneurs. This developed into a protection economy where the individuals within the military elite placed themselves at the centre of trafficking activities, acting as the core of an armed network that protected the movement of contraband. All opposition to this, both political and within the weak justice system, were cowed into silence. At least one of the reasons for the 2012 coup was to ensure effective control over the drug trafficking economy. Drug trafficking was, by then, a significant resource stream, without which the patronage networks within the military elite could not be effectively maintained.

The protection network evolved then – from a wider cross military-civilian network, to a more exclusively military one – and in the end, this was its downfall. The military muscled out any other forms of opposition or partnership, becoming both protectors and traffickers. While Indjai was reluctant to go out to sea to meet the ostensible representatives of FARC, it should not be forgotten that the evidence suggests that he still wanted to pursue the transaction, sending emissaries instead. The result was greater control but also greater vulnerability; by placing themselves as the interlocutors with the traffickers and assuming control over the trafficking business (a task for which they had little skill), they were vulnerable to external law enforcement efforts in a context in which they had little political legitimacy following the 2012 coup.

What, then, are the prospects for a stabilisation of the situation in Guinea-Bissau and the ending or reduction of drug trafficking that has had such a destabilising influence? The new government has acted with both speed and courage to remove Indjai from his position at the head of the military. But the entrepreneurial presence and military networks that rely on illicit trafficking remain. While the leadership of the military-based protection network that held control by 2012 has been decisively weakened, the entrepreneurial network that made the first contact is still very much in place. Those in it seek out new forms of protection, be it from the new political elite or their old contacts within the military.