Teele and Thelen’s (2017) recent study on the gender gap in publication joins a vibrant and growing discussion about gender-based inequalities in political science and academe more generally. Reviewing 15 years of publication data for 10 major journals in the discipline, they found that women (1) are underrepresented relative to their numbers in the discipline; (2) are not benefiting equally from trends toward coauthorship; and (3) may be disadvantaged by the dominance of quantitative work.

Teele and Thelen (2017, 442) posed two potential explanations for the documented gaps: (1) rejection rates may be higher for women than for men, or (2) women may submit work at lower rates than men. They noted that they cannot adjudicate between these possibilities with their data. However, citing published analyses of submission data (e.g., Breuning and Sanders Reference Breuning and Sanders2007; Østby et al. 2013Footnote 1), they speculated that the gap cannot be explained by higher rejection rates for women (Teele and Thelen Reference Teele and Thelen2017, 442–3).

An October 2018 special report in this journal further advanced this conversation. Audits of submissions and editorial decisions at five leading journals—American Political Science Review (APSR), World Politics, Comparative Political Studies (CPS), International Studies Quarterly (ISQ), and Political Behavior—seem to largely corroborate Teele and Thelen’s suspicions. As the report organizers noted, “[t]he results across journals were remarkably similar. Even though the journals differ in terms of substantive focus, management/ownership, as well editorial structure and process, none found evidence of systematic gender bias in editorial decisions” (Brown and Samuels Reference Brown and Samuels2018, 2). To summarize, it appears that work by female scholars is underrepresented at the submission stage but that, conditional on submission, male and female scholars have similar acceptance rates (König and Ropers Reference König and Guido2018; Nedal and Nexon Reference Nedal and Nexon2018; Peterson Reference Peterson2018; Samuels Reference Samuels2018; Tudor and Yashar Reference Tudor and Yashar2018).

This article continues these important analyses. We draw on data from an original, individual-level survey of political scientists conducted in the spring of 2017 to understand what drives gender differences in submission practices. As in previous studies, our survey data reveals gender differences in submission rates at the journals that Teele and Thelen (Reference Teele and Thelen2017) studied. The pattern is particularly pronounced for the “top three” journals in the discipline (i.e., APSR, American Journal of Political Science [AJPS], and Journal of Politics [JOP]). What explains these results? Our analysis points to methodological specialization (namely, quantitative–statistical scholarship) and to different publication strategies as explanations for the gender gap in submissions.

Critically, we also find that men and women receive differential returns on their investments in coauthorship. That is, male and female respondents report similar numbers of collaborators, but coauthorship appears to boost submission more strongly for men than for women.

Critically, we also find that men and women receive differential returns on their investments in coauthorship. That is, male and female respondents report similar numbers of collaborators, but coauthorship appears to boost submission more strongly for men than for women. This is potentially an important source of gender disparities because the previously mentioned journal audits show that coauthored work has a higher success rate than single-authored work in several—although not all—journals studied (König and Ropers Reference König and Guido2018; Nedal and Nexon Reference Nedal and Nexon2018; Peterson Reference Peterson2018; Samuels Reference Samuels2018). The differential impact of collaboration on the number of submissions also speaks to a pattern that Sarsons (Reference Sarsons2017) documented in the field of economics: coauthorship (as opposed to single-authorship) hurts female—but not male—economists’ prospects for tenure. Our data indicate that female political scientists get fewer submissions and publications per collaborator; Sarsons’ research indicated that even when female economists do have coauthored publications, they receive less benefit from that work than their male counterparts.

The following sections briefly describe the parameters of the original study. Turning to the data, we then begin by contextualizing Teele and Thelen’s (Reference Teele and Thelen2017) analysis of articles; we consider various submission types and activities, including books and grants. Finding that gender gaps in submission practices appear to be largely concentrated in articles, we focus on submissions to the journals highlighted by Teele and Thelen (Reference Teele and Thelen2017), looking for distinctions by gender and rank. The penultimate section leverages our original survey items to evaluate potential explanations for gendered submission dynamics, including methodological differences, publication strategy and orientations toward risk, and coauthorship. The final section discusses implications of our findings for ongoing conversations about inequality in political science as well as the steps, policies, and practices for addressing these problems.

DATA: THE PROFESSIONAL ACTIVITY IN THE SOCIAL SCIENCES STUDY

Our data are from the Professional Activity in the Social Sciences (PASS) study, a survey conducted by the authors in March 2017. In early 2017, we sampled half of the American Political Science Association (APSA) member departments (N=308)Footnote 2 and then generated a list of faculty in those departments (N=5,084).Footnote 3 A solicitation with a survey link was emailed to all faculty members in the sampled departments. After three reminders, 900 political scientists completed the Internet survey for a final response rate of slightly less than 18%.

Demographic comparisons between the PASS study, two recent surveys of political scientists, and numbers reported by the APSA are in appendix table A1. It is worth noting that the sample is about 10% more female than other datasets (e.g., Mitchell and Hesli’s Reference Mitchell and Hesli2013 study) but is otherwise comparable in terms of rank, race, subfields, and percentages from PhD-granting institutions.

We asked respondents a variety of questions about their professional behavior over the past year. In addition to collecting self-reported information on submissions and publications, we also asked about advice networks, work–life balance, reviewing behavior, and attitudes toward the publication process more generally.

GENDER, SUBMISSIONS, AND PUBLICATIONS: A FIRST LOOK

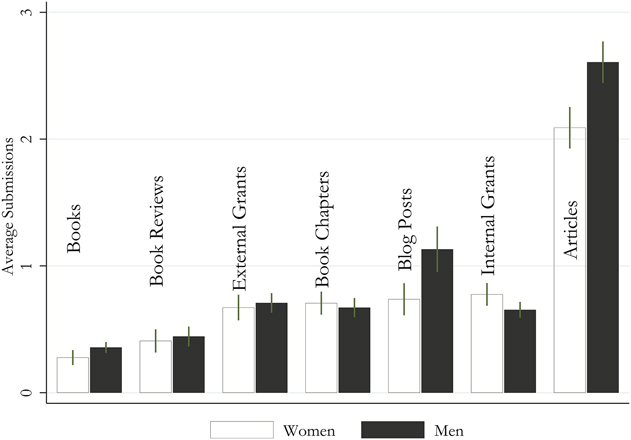

Our PASS survey queried respondents for submission and publication information not only about articles; we also asked about activity related to books, book reviews, internal and external grants, and blogging. Figure 1 presents respondents’ reports on the number of submissions in the past year categorized by gender and type of work. As might be expected, book manuscripts had the lowest number of submissions and articles the highest, with other types of works falling somewhere in between. Although there is a slightly higher mean number of submissions for men when we sum responses across the categories, the gender differences emerge as statistically significant only for blog posts and articles. The latter gender gap in journal-article submissions is, of course, especially important for our purposes.

Figure 1 Submissions in the Past Year, by Gender

Source: PASS Survey.

Note: Comparing confidence intervals shown is the equivalent of a 90% (two-tailed) difference-of-means test.

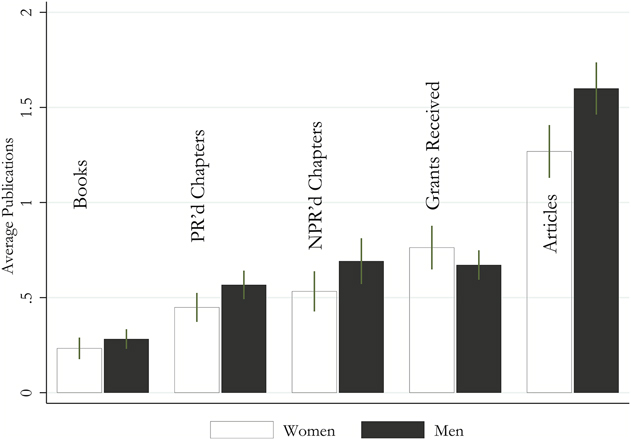

Figure 2 shifts the focus to publication rates, once again considering whether there is something unique about journal activity relative to other types of professional output. The figure suggests that there is: whereas male respondents again recorded higher numbers across several publication types, differences between men and women are statistically significant only in the case of journals. Indeed, although there are hints of a broad gendered pattern of publication, the gap in submissions and publications appears to be concentrated in what is arguably the dominant currency of the discipline: journal articles.

Figure 2 Average Publications in the Past Year, by Gender

Source: PASS Survey.

Note: Comparing confidence intervals shown is the equivalent of a 90% (two-tailed) difference-of-means test.

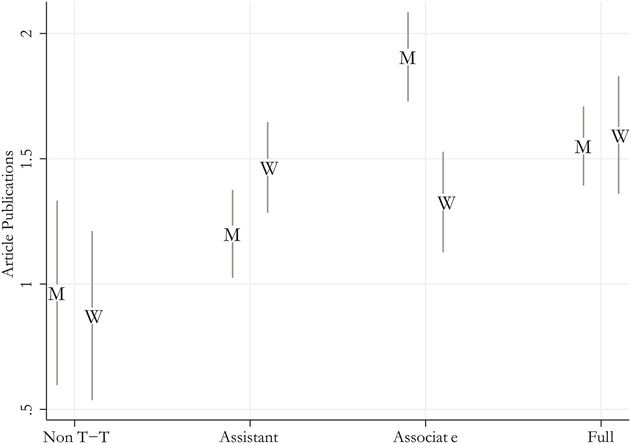

Figure 3 previews analyses to come by categorizing differences in journal articles by rank and gender. We immediately observe that rank should be considered in any subsequent examination of gendered publication dynamics because the gap in article production in our data appears to be driven by male associate professors (i.e., 1.9 articles a year compared to 1.3 for women in this rank). The ways in which gender and rank are linked to journal-submission practices are discussed next.

Figure 3 Articles Published in the Last Year by Gender and Rank

Source: PASS Survey.

Note: Comparing confidence intervals shown is the equivalent of a 90% (two-tailed) difference-of-means test.

SUBMISSIONS TO JOURNALS INCLUDED IN TEELE AND THELEN’S (2017) ANALYSIS

The first cut at our data confirmed previous accounts of gender gaps and also provided an additional perspective that narrowed our focus: journal articles seem uniquely affected. Teele and Thelen (Reference Teele and Thelen2017) identified publication disparities in an analysis of 10 major journals during a 15-year period.Footnote 4 For six journals—including all top-three outlets (i.e., APSR, AJPS, and JOP)—women were underrepresented relative to their numbers in the top 20 PhD departments or their share of APSA membership (Teele and Thelen Reference Teele and Thelen2017, 436). Are there similar disparities in submission practices for these same journals?

Figure 4 graphs the female percentage among respondents who reported submitting to the same 10 journals analyzed by Teele and Thelen (Reference Teele and Thelen2017). For comparison, we report Teele and Thelen’s percentages of published authors who are women (i.e., blue bars) next to our numbers. We also place markers for the share of women in the discipline (i.e., horizontal lines; see figure notes).

Figure 4 Percentage of Submissions and Publications by Women in Journals Analyzed by Teele and Thelen (Reference Teele and Thelen2017)

Source: PASS Survey.

Notes: The horizontal lines mark the share of women in the discipline, as reported by Teele and Thelen (2017, 436). The solid line marks the share of women in tenure-track positions in the top 20 PhD-granting departments (27%); the short-dashed line is the portion of women among APSA members (31%); and the long-dashed line is the share of women among new PhDs (40%), according to the National Science Foundation’s survey of earned doctorates.

The bars in the figure reveal that within each journal, submission rates of women scholars correspond closely to their publication rates. In a few cases, the percentage that reported submitting to a journal outpaced the percentage of published authors who are female (e.g., World Politics); in a few cases, this pattern is reversed (e.g., Political Theory and Perspectives on Politics). However, for the most part, the two bars track closely together. This suggests that when women submit journal articles, they publish at rates comparable to those of men. That is, there is no evidence that women’s work is rejected more frequently than men’s.Footnote 5

All three of the discipline’s top “general-interest” journals fall in the bottom half of the ranking of these 10 journals using our numbers on submissions: that is, fewer than 25% of our respondents who reported submitting to the APSR, AJPS, or JOP were female.

In most cases, the percentage of those reporting ever submitting to each journal who are female falls below the share of women in the discipline (regardless of the measure of that percentage). All three of the discipline’s top “general-interest” journals fall in the bottom half of the ranking of these 10 journals using our numbers on submissions: that is, fewer than 25% of our respondents who reported submitting to the APSR, AJPS, or JOP were female. This seems to confirm Teele and Thelen’s (Reference Teele and Thelen2017) speculation that the publication gap is driven by a submission gap.

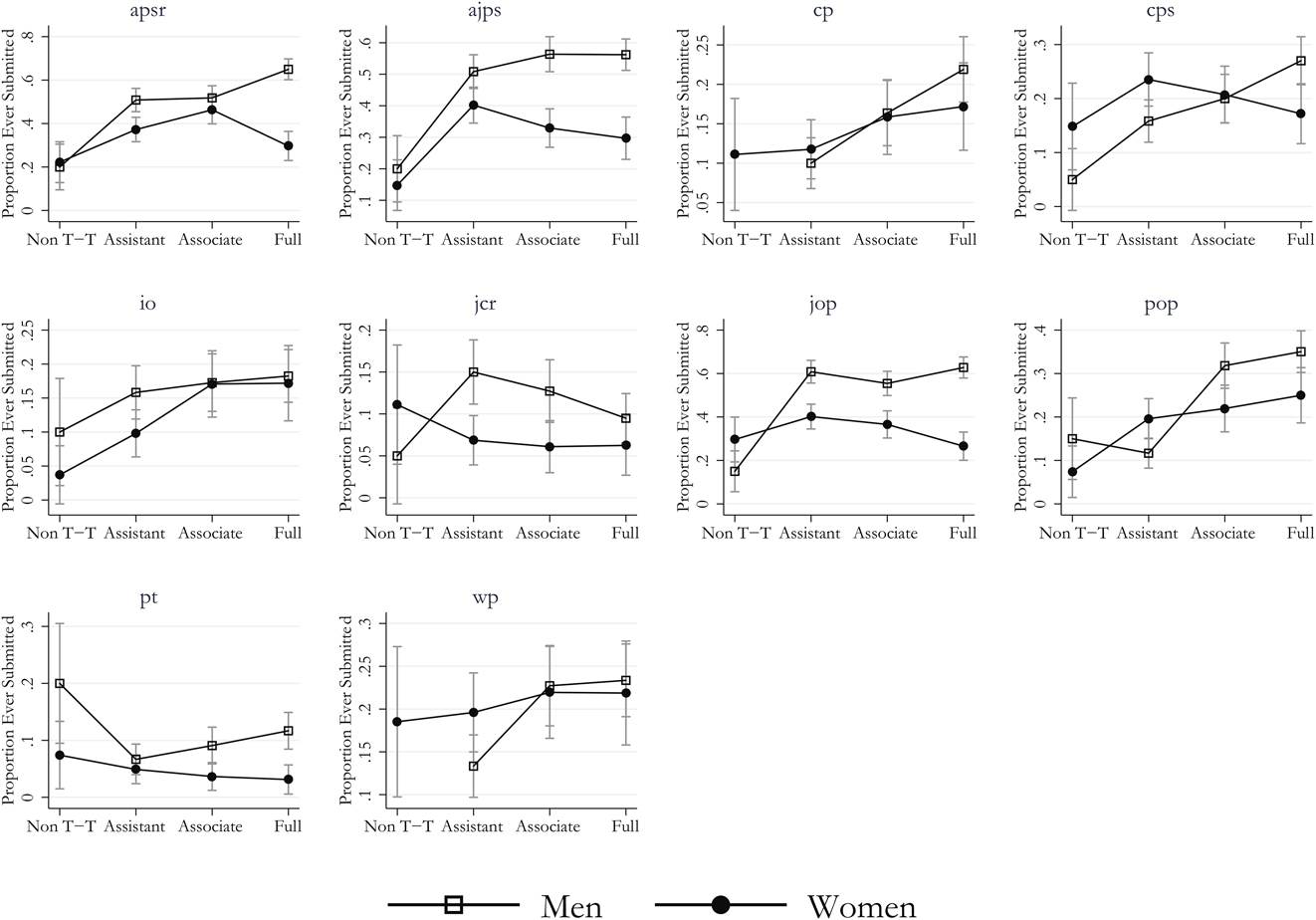

Figure 5 further scrutinizes submission patterns for these journals, plotting the proportion of respondents who reported ever submitting by gender and rank. Several noteworthy patterns emerge. First—as might be expected—submission rates are generally lower for non-tenure-track than tenure-track faculty. Second, for most of these journals, the rates of submission are higher across most ranks for men (squares) than for women (circles). To be clear, these differences are not always statistically significant, but men’s reported rates generally track higher than women’s. Third, for the discipline’s consensus top-tier journals (i.e., APSR, AJPS, and JOP), this gendered pattern obtains and is statistically significant across most ranks.

Figure 5 Percentage of Male and Female Political Scientists Who Submitted to Journals Analyzed in Teele and Thelen (Reference Teele and Thelen2017) by Rank

Source: PASS Survey.

Note: Comparing confidence intervals shown is the equivalent of a 90% (two-tailed) difference-of-means test.

Are women aiming for lower-tiered journals as a strategy, expecting a greater chance of success at such journals? The survey asked respondents a Likert-style battery of questions about their approach to the publication process. Two statements—“I try to send my work to the journal that is most likely to accept it” and “I submit my work to the discipline’s top journals first”—capture two sides of the same coin. Women expressed significantly higher agreement than men that they send their work to journals most likely to accept it (3.6 versus 3.3 on a 1–5 scale). Conversely, women were significantly less likely than men to report sending their work to the top-tier journals first (3.3 versus 3.5 on a 1–5 scale).

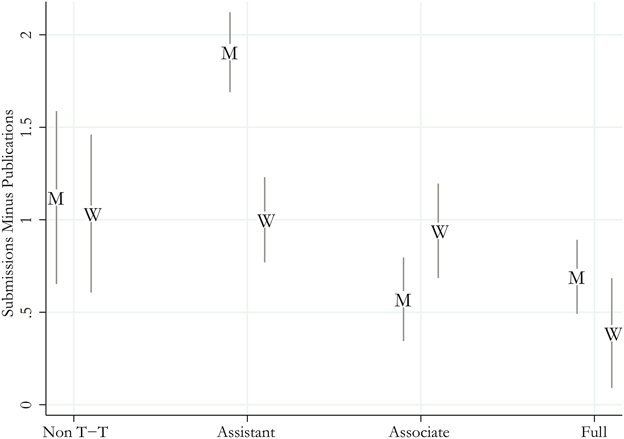

What picture emerges when we reconcile these gendered submission patterns with the pattern of publication rates? In figure 6 we graph the difference between submissions and publications by rank and gender; higher positive numbers signal more submissions per publication—that is, a higher rejection rate. The plot unambiguously shows male assistant professors “flooding” the review process with submissions and receiving higher numbers of rejections relative to their female counterparts. Note also that the rejection rate declines across rank; however, that rate is more stable across rank among women.

Figure 6 Journal Submissions Minus Acceptances (the Rejection Rate) by Gender and Rank

Source: PASS Survey.

Note: Comparing confidence intervals shown is the equivalent of a 90% difference-of-means test.

ARE METHODS DRIVING THESE PATTERNS?

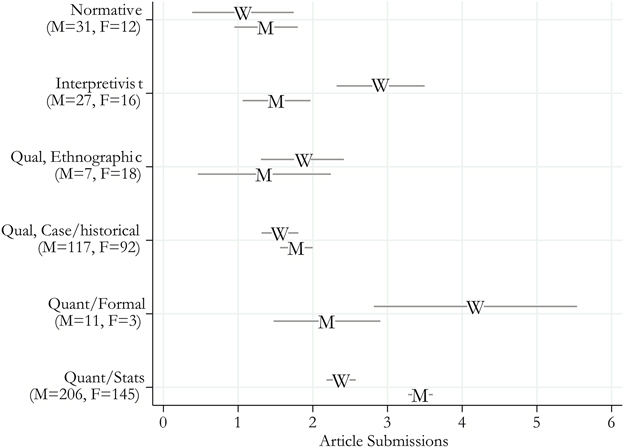

Can gender differences in submissions and publications be traced to the types of work women and men do, as Teele and Thelen (Reference Teele and Thelen2017) suggested? Figure 7, which plots submission rates by respondents’ self-described methodological specializations, suggests that methods are certainly part of the story. Men’s and women’s article-submission rates are comparable in most methodological camps: between one and two articles a year. Only a couple of significant gender differences emerge within categories. Most critically, among scholars reporting that their work is primarily quantitative–statistical, the difference is about one submission per year. Although there are significant gender gaps in the other direction among interpretivists (and a near-significant difference for formal modelers), the size of the quantitative–statistical category—which contains the plurality (40%) of respondents—dwarfs all other specializations (respondent numbers are reported under the labels in the table).

As the discipline of political science has become more accepting of collaborative work, do we see differences by gender? Do women political scientists report coauthoring at rates similar to men, and do these projects help them produce additional submissions and publications that might close the gaps?

Figure 7 Submissions by Gender and Methodological Specialization

Source: PASS Survey.

Note: Comparing confidence intervals shown is the equivalent of a 90% (two-tailed) difference-of-means test.

DOES COAUTHORSHIP HELP?

We also consider the effects of coauthorship. As the discipline of political science has become more accepting of collaborative work, do we see differences by gender? Do women political scientists report coauthoring at rates similar to men, and do these projects help them produce additional submissions and publications that might close the gaps?

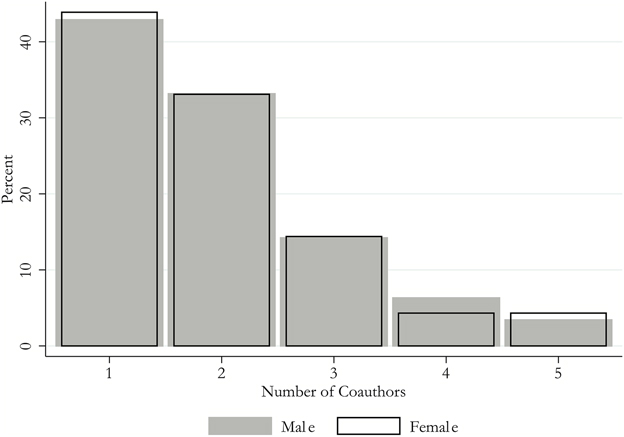

Figure 8 presents the percentage of respondents who reported a varying number of coauthors on their most recent journal-article submission. Gray-shaded bars represent male respondents and unshaded bars represent female respondents. Two observations emerge as noteworthy: (1) coauthorship is common in our sample, in-line with other reports of disciplinary trends; and (2) the close overlap in the bars suggests that men and women coauthor at rates that are indistinguishable (i.e., 57% of men and 56% of women coauthored their most recent paper; p=0.80).

Figure 8 Number of Coauthors on Most Recent Journal Submission, by Gender

Source: PASS Survey.

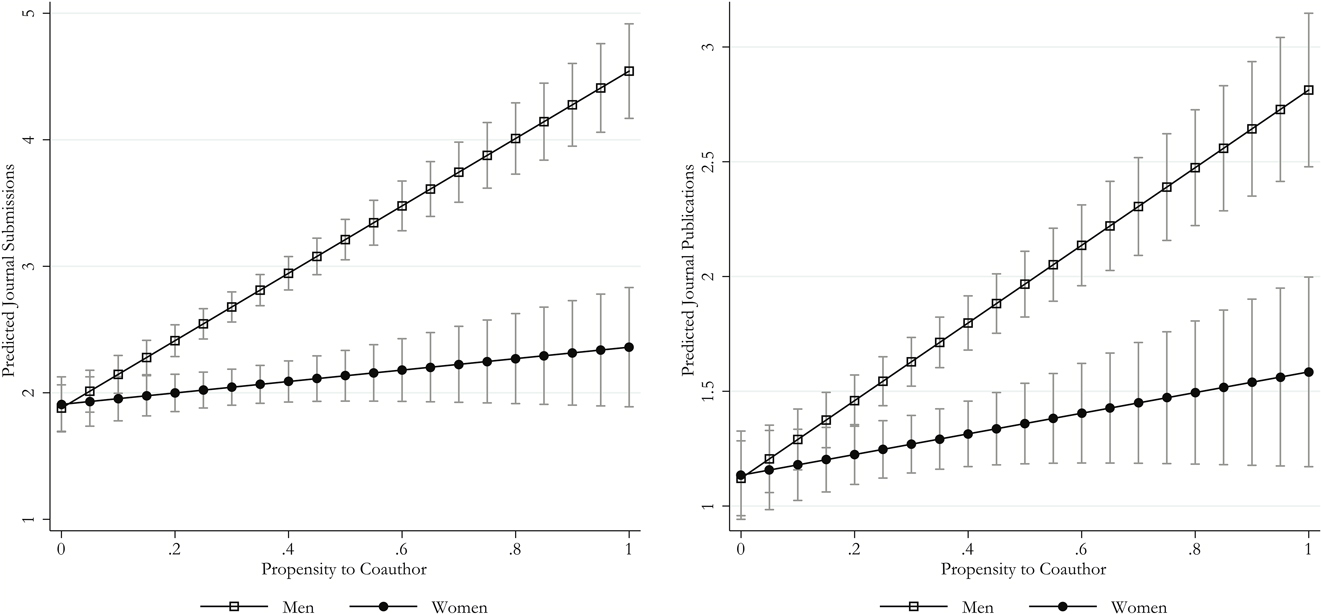

If men and women coauthor at similar rates, do they benefit equally? Figure 9 visualizes the results of regression models predicting submissions (panel A) and publications (panel B) as a function of gender and the propensity to coauthor. Propensity to coauthor is created by combining answers to Likert items on collaboration and information that respondents reported about their professional networks.

Figure 9 Effects of Gender and Coauthorship on Submissions and Publications

Source: PASS Survey.

While coauthorship boosts submissions and publications for all respondents, men benefit considerably more than do women from working with others. Across the range of the coauthorship item, the predicted number of submissions remains stagnant for women; it slopes slightly upward for publications. For men, the increase in submissions and publications is dramatic: male political scientists most predisposed to coauthor are predicted to acquire roughly two more submissions and two more publications versus those least likely to do so. In follow-up analyses, we discover that the effect of coauthorship is particularly strong for men at the assistant-professor level. Among untenured men, across the range of coauthorship, the number of submissions increases from about two to nearly seven; among tenured men, coauthorship doubles the number of submissions from two to four. By contrast, the impact of coauthorship on publications is similar for men at all ranks: it increases the annual number of publications from about one to about three.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

Teele and Thelen’s (Reference Teele and Thelen2017) analysis of publication gaps in journals represents an important piece of self-study for political scientists. We build on their effort in several ways. First, we not only confirmed the patterns they found in assembling journal-publication data, we also provided context for those differences, noting that they appear to be largely limited to journal-article submissions versus other types of work in the discipline (e.g., books). Second, we addressed the call to examine what might be driving such publication differences, finding considerable evidence pointing toward a submission gap. Third, we evaluated several factors that may be driving these submission patterns, finding that quantitative/qualitative differences likely play a role, along with risk orientation toward the review process. Importantly, coauthorship appears to amplify rather than mitigate gender differences.

What are we to make of this constellation of results? Fully understanding the findings we outlined requires further examination of the work processes of women and men. For instance, how do women and men decide when a solo-authored publication is ready for submission? How do women and men choose coauthors? How is labor distributed within mixed-gender collaborative arrangements? In further examining these arrangements, care must be taken not to assume that female political scientists should simply imitate the behavior of male political scientists.

Nonetheless, tentative recommendations are in order. If the publication gap is a function of submission differences (and not the peer-review process), then closing it should be as “easy” as facilitating more journal submissions by women. Of course—and as our analyses demonstrated—there are several impediments blocking such a course of action. To the extent that men and women who do quantitative–statistical work submit that work at different rates, hope seems to lie in the continuing efforts to bring more women into methodological conversations in the discipline (e.g., Visions in Methodology). To the extent that women seem to be “aiming low” with their work, encouraging them to submit their manuscripts to top journals—particularly following tenure—makes sense. Such encouragement to “give it a shot” also should be paired with (continued) editorial efforts to produce faster review cycles, thereby making submission to top journals a less costly decision, and with efforts to address perceived or real barriers at those journals to the kinds of work in which women specialize. Finally, to the extent that women do not receive the same return on their investments in coauthorship, it seems that in addition to working to ensure that women are rewarded equally for shared work, providing guidance on effective collaborative strategies might be a useful investment for graduate programs and other professional-development initiatives.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S104909651800104X.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Sara Mitchell for sharing data, and panelists and colleagues at the 2017 meetings of the Midwest Political Science Association and the APSA as well as the 2018 meeting of Visions in Methodology for helpful conversations and feedback.