Aquaculture is the fastest-growing animal production sector accounting, at present, for more than 50 % of worldwide fish consumption( 1 ), but one major issue concerning such development is the over-dependence of fish feeds on capture fishery-derived raw materials such as fishmeal (FM) and fish oil (FO)( Reference Kaushik and Troell 2 ). The established beneficial roles of FO on human health( Reference Wang, Harris and Chung 3 ) and the use of FO, albeit in small proportions, in other animal production systems, have led to an increase in the demand for this raw material, consequently, raising the prices. Despite great achievements in the reduction of FM in diets of marine fish species( Reference Benedito-Palos, Saera-Vila and Calduch-Giner 4 – Reference Shepherd and Bachis 8 ), complete replacement of FO still remains a major challenge. Moreover, complete substitution of FO negatively affects the immune system and stress and disease resistance( Reference Montero and Izquierdo 9 ) as well as reduces the fillet content of long-chain n-3 PUFA (n-3 LC-PUFA, includes twenty or more carbon atoms), such as EPA and DHA, negatively affecting the nutritional value of fish flesh for humans( Reference Eroldoğan, Yılmaz and Turchini 10 – Reference Yılmaz, Corraze and Panserat 13 ).

FO is rich in n-3 LC-PUFA, whereas vegetable oil (VO) sources, except in some cases( Reference Betancor, Sprague and Usher 14 ), lack the essential fatty acids (EFA) for marine fish such as EPA and DHA but can have significant amounts of α-linolenic acid (ALA), 18 : 3n-3, and linoleic acid (LA), 18 : 2n-6, which are biological precursors of EFA. Yet, the bioconversion of 18-carbon PUFA to EPA and DHA depends on the elongation and desaturation capacity of the fish species( Reference Sargent, Tocher and Bell 15 , Reference Castro, Tocher and Monroig 16 ). Generally speaking, whereas freshwater fish possess the ability to convert ALA and LA into LC-PUFA( Reference Leaver, Villeneuve and Obach 17 , Reference Sargent, Bell and McEvoy 18 ), marine fish do not possess the sufficient enzyme activity( Reference Tocher 19 ). Nonetheless, LC-PUFA synthesis capacity also appears to differ among marine species( Reference Monroig, Tocher and Navarro 20 – Reference Xu, Dong and Ai 23 ). The higher LC-PUFA biosynthesis capacity in freshwater fish in comparison with that of marine fish could be related to differences in the feeding habits and nutrient intake, with marine fish having a continuous access to LC-PUFA-rich sources throughout their lives( Reference Sargent, Bell and Bell 24 , Reference Tocher 25 ). Besides, these differences among fish species have been related to the diverse evolution of certain genes involved in lipid biosynthesis( Reference Castro, Tocher and Monroig 16 ).

Recent evidence suggests that environmental factors experienced by the parents can have long-lasting effects in the offspring or in the later generations( Reference Burton and Metcalfe 26 , Reference Burdge, Hanson and Slater-Jefferies 27 ). Thus, early environmental signs, such as available nutrients during reproduction, can modulate metabolic routes and offspring phenotype( Reference Burdge, Hanson and Slater-Jefferies 27 – Reference Gluckman and Hanson 29 ). This type of metabolic regulation, known as ‘nutritional programming’, has been principally derived from mammalian models, because of their potential effects on development of metabolic disorders in humans in later life( Reference Langley-Evans 30 ). Therefore, better understanding of the outcomes of parental nutrition and the underlying mechanisms can contribute to the prevention of consequences in the offspring. Besides, nutritional programming may also have potential applications in animal production( Reference Gotoh 31 ). In aquaculture, one of the potential beneficial applications of nutritional programming may be the production of individuals better prepared to use some feedstuffs supplying or lacking in specific nutrients, such as VO and plant-protein sources. For instance, specific fat and dietary fatty acid supply during embryonic and offspring development may adjust fish metabolism for better utilisation of 18-carbon fatty acids later in life. Thus, parental nutritional interventions can modulate epigenetic mechanisms that control ‘metabolic decisions’ that are meiostatically and mitotically stable through life in humans( Reference Öst and Pospisilik 32 ), rodents( Reference Lillycrop, Phillips and Jackson 33 , Reference Morgan, Sutherland and Martin 34 ) and cattle( Reference Mossa, Walsh and Ireland 35 ). In fish, nutritional programming studies have mostly focused on early feeding( Reference Clarkson, Migaud and Metochis 36 – Reference Vagner, Robin and Zambonino-Infante 43 ), whereas parental nutritional interventions are scarcer( Reference Morais, Mendes and Castanheira 44 – Reference Otero-Ferrer, Izquierdo and Fazeli 46 ).

The gilthead sea bream (Sparus aurata), is a multi-batch spawner whose oligolecitic eggs largely depend on their continuous intake of nutrients during reproduction( Reference Fernández-Palacios, Norberg and Izquierdo 47 ). For this reason, egg nutrient content of the gilthead sea bream can be markedly affected by the parental diet even during the spawning season, in turn, affecting early embryonic development( Reference Izquierdo, Fernandez-Palacios and Tacon 48 ). Our previous studies have demonstrated that feeding gilthead sea bream broodstock with high-linseed oil (LO) diets markedly affects fecundity, spawn quality and growth of 45-d-after-hatch larvae and 4-month-old juveniles( Reference Izquierdo, Turkmen and Montero 45 ). Interestingly, when 4-month-old juveniles were challenged with a low-FM and low-FO diet, offspring from parents fed a replacement of 60 %-FO with LO showed a faster growth and better feed utilisation than those whose parents had been fed with FO( Reference Izquierdo, Turkmen and Montero 45 ). However, the potential persistence of the effects of broodstock nutritional history on the offspring later in life is still unknown.

Further, little is known on the physiological or molecular mechanisms involved in the effect of parental diets on the metabolic performance of the offspring. When n-3 LC-PUFA are limited and the 18-C atom fatty acids are available in gilthead sea bream diet, the gene for fatty acid desaturase 2 (fads2), the key-limiting enzyme for LC-PUFA synthesis, is up-regulated( Reference Izquierdo, Robaina and Juárez-Carrillo 49 ). Long-chain fatty acid synthesis also involves chain-elongation catalysed by elongases (Elovl) with different substrate preferences( Reference Monroig, Navarro and Tocher 50 ). Among them, Elovl6 is a key lipogenic enzyme that elongates long-chain SFA and MUFA of 12, 14 and 16 carbon atoms, which has received much attention because of its importance in metabolic disorders( Reference Matsuzaka and Shimano 51 ). Besides, LC-PUFA may have a direct effect on the expression of other genes related to lipid or carbohydrate metabolism( Reference Clarke 52 ). Lipoprotein lipase (lpl) facilitates the tissue uptake of circulating fatty acids( Reference Bell and Koppe 53 ) from lipoproteins and its expression in the liver can be regulated by n-3 LC-PUFA( Reference Raclot, Groscolas and Langin 54 ). The provision of energy is accomplished by β-oxidation of free fatty acids transported into the mitochondria in the form of fatty acyl-carnitine esters by carnitine acyltransferases, such as carnitine palmitoyltransferases( Reference Sargent, Tocher and Bell 15 ). Replacement of FO with VO changes the fatty acid composition of liver and muscle, affecting the β-oxidation capacity and regulating the expression of cptI and cptII genes( Reference Leaver, Villeneuve and Obach 17 , Reference Kjaer, Todorcevic and Torstensen 55 – Reference Xue, Hixson and Hori 57 ). β-Oxidation also takes place in the peroxisome and is modulated by PPAR. A total of three different PPAR isoforms (α, β, γ) have been characterised in gilthead sea bream, pparα being the major form expressed in the liver( Reference Leaver, Bautista and Bjornsson 58 ). PPAR are nuclear receptors that regulate differentiation, growth and metabolism and, in mammals, epigenetic mechanisms have been described to regulate these processes involving all the PPAR isoforms( Reference Corbin 59 ). For instance, feeding pregnant rats a protein-restricted diet reduces methylation of the pparα promoter in the offspring and the hypomethylation persists into adulthood( Reference Lillycrop, Phillips and Torrens 60 ). Finally, another gene potentially regulated by LC-PUFA is cyclo-oxygenase-2 (cox2), a key enzyme in prostanoid biosynthesis( Reference Ishikawa and Herschman 61 ).

The objective of the present study was to explore the potential persistence of nutritional programming through parental feeding in offspring later in life and to analyse the physiological or molecular mechanisms implied. For this purpose, the offspring of gilthead sea bream broodstock fed diets with different FO/LO levels were followed up for 18 months until the beginning of first gonad development and nutritionally challenged at 4 and 16 months with low FM and FO diets. The effects of both broodstock feeding and nutritional challenge on growth, chemical and fatty acid composition of muscle and liver as well as on the expression of selected genes in the liver were investigated.

Methods

Experimental animals

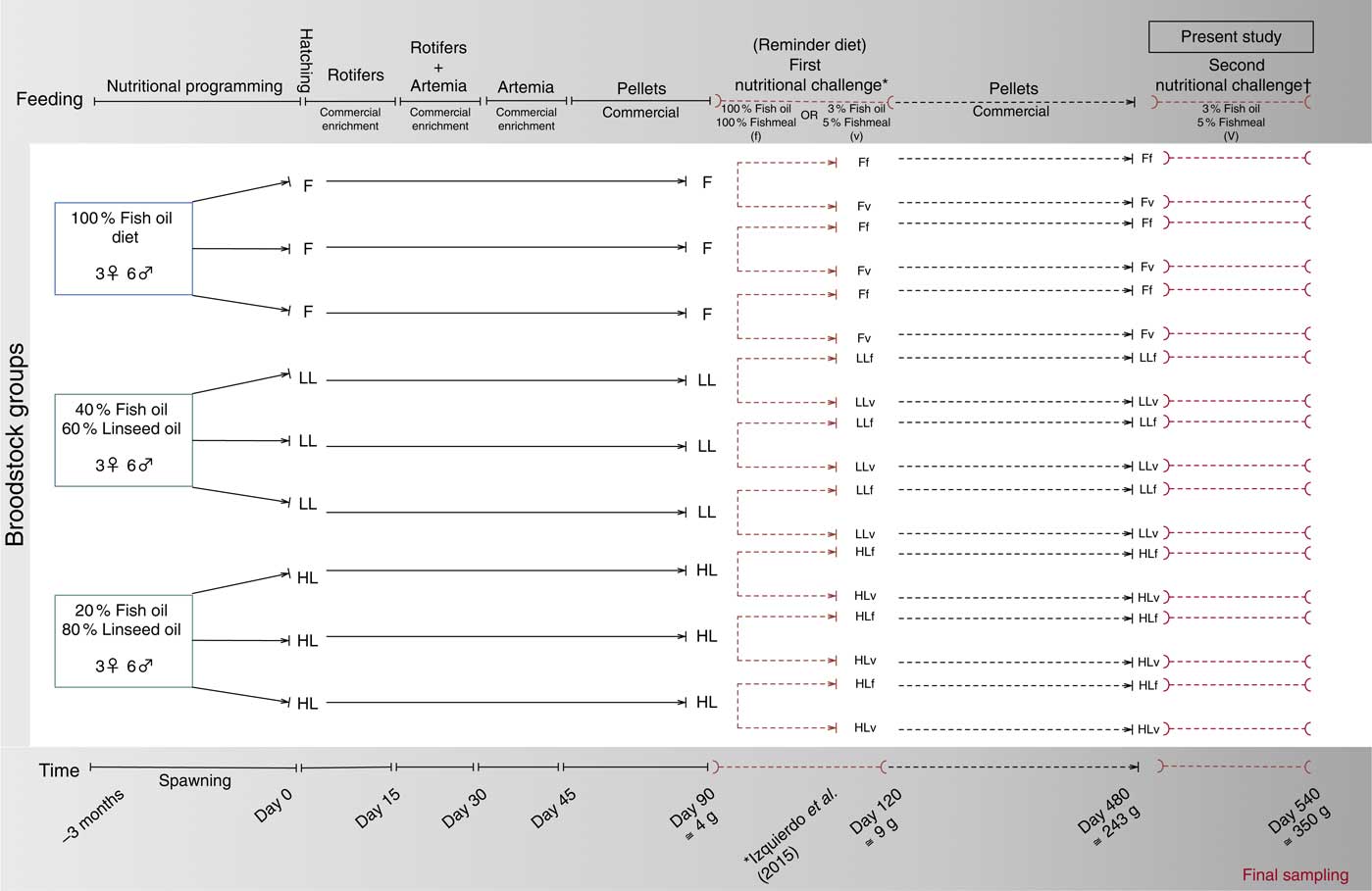

All fish were obtained from spontaneous spawns of gilthead sea bream broodstock fed three diets with three levels of FO substitution with LO: 100 % FO, 40 % FO–60 % LO (LL) and 20 %FO–80 % LO (HL)( Reference Izquierdo, Turkmen and Montero 45 ). Offspring from all groups were fed the same commercial diet during larval rearing, weaning and during the growing period until they reached 4 months of age (120 d)( Reference Izquierdo, Turkmen and Montero 45 ). At this stage, triplicate groups of juveniles were nutritionally challenged for 1 month with either a high-FM/FO diet (f) or with a high-VM/LO diet (v) named as ‘reminder diet’ in the present study. Details of the broodstock feeding, juvenile nutritional challenge (reminder) at 4 months and feed formulation have been reported earlier( Reference Izquierdo, Turkmen and Montero 45 ). After this first nutritional challenge (reminder), fish were maintained separately in 1000 litre tanks and fed the same commercial diet until they were 16 months old for use in the present study. A schematic view of this nutritional programming history is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1 Schematic view of the nutritional programming history of gilthead sea bream. F, 100 % fish oil; LL, 40 % fish oil–60 % linseed oil; and HL, 20 % fish oil–80 % linseed oil; f, fish oil-based diet; v, reminder diet. * Previous publication, Izquierdo et al. (2015)( Reference Izquierdo, Turkmen and Montero 45 ). † Time of the present study.

In the present study, 16-month-old offspring sea breams of homogeneous weight were selected and distributed into 18 500- litre light-grey fibreglass cylinder tanks (2·8 kg/m3). Each tank contained thirty fish with mean initial body weight of 243·2 (sd12·7) g. Tanks were supplied with filtered seawater (37 parts per million (ppm) salinity), which entered from the tank surface and drained from the bottom at a rate of 250 litre/h to maintain a high water quality, which was tested daily and no deterioration was observed. O2 level, water temperature and pH were monitored in real-time using Miranda aquaculture water quality monitoring system (Innovaqua). Water was continuously aerated (125 ml/min), attaining an average of 6·8 (sd 0·8) ppm dissolved O2 during the experimental period. The average water temperature and pH for the duration of the trial were 24·6±0·6°C and 7·89, respectively. Natural photoperiod was maintained during the whole experimental period (10- h light).

Experimental diet

The experimental diet was formulated and produced by Biomar to be low in FO (3 %) and FM (5 %). Thus, the diet was high in oleic acid (18 : 1n-9), LA (18 : 2n-6) and ALA (18 : 3n-3) (Table 1). Juveniles from each group were fed daily until apparent satiation for 60 d, three times a day at 09.00, 13.00 and 17.00 hours. The feed was supplied in small portions (<5–6 pellets at a time) to ensure that all feed was eaten. After each feeding, uneaten feed was collected, kept in aluminium oven trays, dried overnight at 105°C and weighted to calculate feed intake.

Table 1 Main ingredientsFootnote *, energy, protein and % total fatty acids contents of diet for the nutritional challenge of gilthead sea bream juveniles obtained from broodstock fed diets 100 % fish oil (FO), 40 % FO–60 % linseed oil (LO) and 20 % FO–80 % LO during spawning

* Please see Torrecillas et al. ( Reference Torrecillas, Robaina and Caballero 62 ) for the complete list of feed ingredients.

† South American, Superprime (Feed Service).

‡ Blood meal spray (Daka), soya protein concentrates 60 % (Svane Shipping), maize gluten 60 (Cargill), wheat gluten (Cargill).

§ Linseed (2·6 %) (Ch. Daudruy), rapeseed (5·2 %) (Emmelev) and palm oils (5·2 %) (Cargill).

Biochemical analyses

Moisture, protein( 63 ) and crude lipid( Reference Folch, Lees and Sloane-Stanley 64 ) contents of the tissue samples and diets were analysed. Fatty acid methyl esters were obtained by trans-methylation of crude lipids as previously described( Reference Christie 65 ). Fatty acid methyl esters were separated using GLC (GC-14A; Shimadzu) following the conditions described previously( Reference Izquierdo, Watanabe and Takeuchi 66 ) and identified by comparison with previously characterised standards and GLC-MS (Polaris QTRACETM Ultra; Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Molecular studies

Liver samples from three fish per each tank (nine per group) were collected at the beginning (480-d-old fish) and at the end of the feeding challenge (540-d-old fish). Samples were collected on ice from fish kept unfed for 24 h, each tissue sample from one individual was assigned to a corresponding 1·5-ml Eppendorf tube and was snap frozen in liquid N2 immediately after sampling. The samples were then stored at –80°C until RNA extraction and analyses. RNA was extracted using Qiagen RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen). Before real-time PCR analysis two different potential housekeeping genes, β-actin (β-act) and ribosomal protein L27 (rpl27), were tested. Data from duplicate samples (n 18) using the two candidate housekeeping genes were compared using an online program (http://leonxie.esy.es/RefFinder/?type=reference) (RefFinder)( Reference Xie, Xiao and Chen 67 ) and β-act was selected as the most suitable housekeeping gene for the present study (β-act, threshold cycle (C t ) values: min=18·9, max=20·6, mean=19·64, sd=0·5; rpl27: min=17·0 max=21·2, mean=19·1, sd=1·01).

Real-time quantitative PCR were performed in an iQ5 Multicolor Real-Time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad) using β-act as the housekeeping gene in a final volume of 15 µl/reaction well and with 100 ng of total RNA reverse-transcribed to complementary DNA (cDNA). Samples, housekeeping gene, cDNA template and reaction blanks were analysed in duplicates (Table 2). Primer efficiency was tested with serial dilutions of a cDNA pool (1:5, 1:10, 1:100 and 1:1000). A single ninety-six-well PCR plate was used to analyse each gene, primer efficiency and blank samples (Multiplate; Bio-Rad). Melting-curve analysis was performed and amplification of a single product was confirmed after each run. Fold expression of each gene was determined by delta–delta C

T

method (

![]() $$2^{{{\minus}\Delta \Delta C_{T} }} $$

)(

Reference Izquierdo, Watanabe and Takeuchi

66

). PCR efficiencies were similar and no efficiency correction was required(

Reference Livak and Schmittgen

71

,

Reference Schmittgen and Livak

72

) (Table 2). Fold expression was related to that of offspring obtained from FO diet-fed broodstock and fed commercial diets throughout their life (Ff group).

$$2^{{{\minus}\Delta \Delta C_{T} }} $$

)(

Reference Izquierdo, Watanabe and Takeuchi

66

). PCR efficiencies were similar and no efficiency correction was required(

Reference Livak and Schmittgen

71

,

Reference Schmittgen and Livak

72

) (Table 2). Fold expression was related to that of offspring obtained from FO diet-fed broodstock and fed commercial diets throughout their life (Ff group).

Table 2 Primers, RT-PCR reaction efficiencies, and GeneBank accession numbers and reference articles for sequences of target and housekeeping genes

lpl, lipoprotein lipase; elovl6, elongation of very long-chain fatty acids protein 6; fads2, fatty acid desaturase 2; cox2, cyclo-oxygenase-2; cpt1, carnitine palmitoyltransferase I; β-act, β-actin.

* The average efficiency of housekeeping gene from six RT-PCR runs.

Statistical analysis

Data on growth and biochemical composition were statistically analysed using two-way ANOVA, using broodstock diet and reminder diet as fixed factors in IBM SPSS version 23.0.0.2 for Mac (IBM SPSS Inc.). Data were split into groups based on each fixed factor (broodstock and reminder diet) and compared with one-way ANOVA. Scheffe’s post hoc multiple comparisons for broodstock and reminder diet, separately, assessed differences between groups. Before the analysis of data, equality of variances was tested using Levene’s test and distribution of data using Shapiro–Wilk tests. All data except cox2 gene expression showed normal distribution and equality of variances.

Gene expression data (except for cox2) were analysed by means of two-way ANOVA using broodstock and reminder diet as fixed factors. Expression data were next analysed using Welch’s ANOVA and subsequently compared with the Games–Howell test for identification of differences between groups. The fixed factor for Welch’s ANOVA was experimental groups in gene expression data analysis. Pearson’s correlation test was performed using R (R Foundation for Statistical Computing). Gene expression figures were created using lattice package (version 0.20–33)( Reference Sarkar 73 ) downloaded from the comprehensive R Archive Network library. The sample size for all analysed data was nine and data were expressed as means and standard deviations.

Results

Growth performance

The low-FM/FO diet was well accepted and there were no significant differences in feed intake among fish groups (mean, 3·95 (sd 0·39) kg, P>0·05). At the beginning of the trial, there were no significant differences in fish body weight (mean, 243·2(sd 12·7) g) among experimental groups (P>0·05) (Table 3). However, after 60 d of feeding the low-FM/FO diet, LLv fish (obtained from broodstock fed low LO and fed at 4 months with the v, high in VM and VO) showed the highest body weight, being significantly (P<0·05) higher than that of fish LLf, from the same broodstock but fed the diet f at 4 months (high in FM and FO) (Table 3). Besides, the growth of LLv fish was also significantly higher than that of fish from Fv or HLv that had been fed the same v, but came from broodstock fed FO or high LO. Thus, the two-way ANOVA analysis of final body weight showed a significant effect of the broodstock diet (P<0·05) and the interaction between broodstock and reminder diet (P<0·01). The specific growth rate of LLv fish was significantly higher than that of LLf, denoting the significant effect of the v, as well as higher than Fv and HLv (P<0·05). Thus, the two-way ANOVA showed the significant effect of the reminder diet at 4 months as well as the interaction between broodstock and reminder diet (P<0·05). Regarding feed conversion, the best values were also obtained for fish in the LLv, Fv or HLv group. For fish coming from broodstock fed FO, the feed conversion ratio (FCR) was better when fish had been fed FO at 4 months (Ff) than when fed diet v (Fv). The two-way ANOVA showed a strong interaction between broodstock and reminder diets (P<0·01).

Table 3 Growth performance parameters after 2 months’ feeding of very low-fishmeal (5 %) and very low-fish oil (FO) (3 %) diet in 16-month-old gilthead sea bream (Sparus aurata) originated from broodstock fed linseed oil (LO) as a replacement for FO – 0 % (100 % FO (F)), 60 % (40 % FO–60 % LO (LL)), 80 % (20 % FO–80 % LO (HL)) – and fed either a fishmeal- and FO-based diet (f) or a very low-fishmeal (5 %) and very low-FO (3 %) ‘reminder’ diet (v) for 1 month at 4 months of age (Mean values and standard deviations; n 3)

SGR, specific growth rate; FCR, feed conversion ratio; ND, no difference.

A,B Mean values with unlike superscript letters were significantly different between fish fed f or v diets during the first nutritional challenge (reminder) coming from the same parental feeding. a,b Mean values with unlike superscript letters were significantly different between fish coming from different parental feeding and fed the same diet during the first nutritional challenge (reminder) (P<0·05).

* SGR (%/d)=(Ln (final weight (g))−Ln (initial weight (g)))/(number of days)×100.

† FCR=(total weight of consumed feed (g))/(weight gain (g)).

Biochemical composition

At the end of the study, protein, lipid and ash contents of liver or muscle were similar (P>0·05) (Table 4). However, liver fatty acid composition was significantly affected by broodstock or reminder diets as well as by their interaction (Table 5). For instance, LO increase in broodstock diet significantly reduced liver contents on 16 : 4n-3, a product of EPA β-oxidation, and increased 16 : 3n-1 or 18 : 0, whereas the interaction of broodstock and reminder diets affected the ratios 18 : 0:16 : 0 and 18 : 1:16 : 1, indicators of elovl6 activity, and the related ratio 16 : 1:16 : 0 (Table 5). The fads2 products 20 : 3n-6 and 20 : 4n-3 were significantly reduced by the reminder diet (P=0·018) and its interaction with the broodstock diet (P=0·015), respectively, whereas 20 : 4n-6, 20 : 5n-3 and 22 : 6n-3 tended to be higher in offspring fed the reminder diet, but were not significantly different (P=0·17) (Table 5). Muscle fatty acid composition did not differ significantly among the different experimental groups (P>0·05) (Table 6).

Table 4 Biochemical composition of liver and muscle tissue after 2 months’ feeding with a very low-fishmeal (5 %) and very low-fish oil (FO) (3 %) diet in 16-month-old gilthead sea bream (Sparus aurata) originated from broodstock fed linseed oil (LO) as a replacement for FO – 0 % (100 % FO (F)), 60 % (40 % FO–60 % LO (LL)), 80 % (20 % FO–80 % LO (HL)) – and fed either a fishmeal- and FO-based diet (f) or a very low-fishmeal (5 %) and very low-FO (3 %) ‘reminder’ diet (v) for 1 month at 4 months of age (Mean values and standard deviations; n 3)

* No significant differences were found for broodstock diet (P>0·05), reminder diet (P>0·05) and interaction of these two factors (P>0·05) using the two-way ANOVA analysis.

Table 5 % Total fatty acids (FA) of livers after 2 months’ feeding a very low-fishmeal (5 %) and very low-fish oil (FO) (3 %) diet in 16-month-old gilthead sea bream (Sparus aurata) originated from broodstock fed linseed oil (LO) as a replacement for FO – 0 % (100 % FO (F)), 60 % (40 % FO–60 % LO (LL)), 80 % (20 % FO–80 % LO (HL)) – and fed either a fishmeal- and FO-based diet (f) or a very low-fishmeal (5 %) and very low-FO (3 %) ‘reminder’ diet (v) for 1 month at 4 months of age (Mean values and standard deviations; n 3)

B, broodstock; R, reminder; B×R, interaction of broodstock and reminder.

* P values under 0·05.

† ∑SFA include 14 : 0, 15 : 0, 16 : 0, 17 : 0, 18 : 0 and 20 : 0.

‡ ∑MUFA include 14 : 1n-7, 14 : 1n-5, 15 : 1n-5, 16 : 1n-5, 18 : 1n-9, 18 : 1n-7, 18 : 1n-5, 20 : 1n-9, 20 : 1n-7, 20 : 1n-5, 22 : 1n-11 and 22 : 1n-9.

§ ∑n-6: n-6 series PUFA include 16 : 2n-6, 18 : 2n-6, 18 : 3n-6, 20 : 2n-6, 20 : 3n-6, 20 : 4n-6, 22 : 4n-6, 22 : 5n-6.

‖ ∑n-3:n-3 series PUFA include 16 : 3n-3, 16 : 4n-3, 18 : 3n-3, 18 : 4n-3, 20 : 3n-3, 20 : 4n-3, 20 : 5n-3, 22 : 5n-3, 22 : 6n-3.

Table 6 % Total fatty acids of muscle after 2 months’ feeding of a very low-fishmeal (5 %) and very low-fish oil (FO) (3 %) diet in 16-month-old gilthead sea bream (Sparus aurata) originated from broodstock fed linseed oil (LO) as a replacement for fish oil – 0 % (100 % FO (F)), 60 % (40 % FO–60 % LO (LL)), 80 % (20 % FO–80 % LO (HL)) – and fed either a fishmeal- and FO-based diet (f) or a very low-fishmeal (5 %) and very low-FO (3 %) ‘reminder’ diet (v) for 1 month at 4 months of age (Mean values and standard deviations; n 3)

* No significant differences were found for broodstock diet (P>0·05), reminder diet (P>0·05) and interaction of these two factors (P>0·05) using the two-way ANOVA analysis.

Gene expression

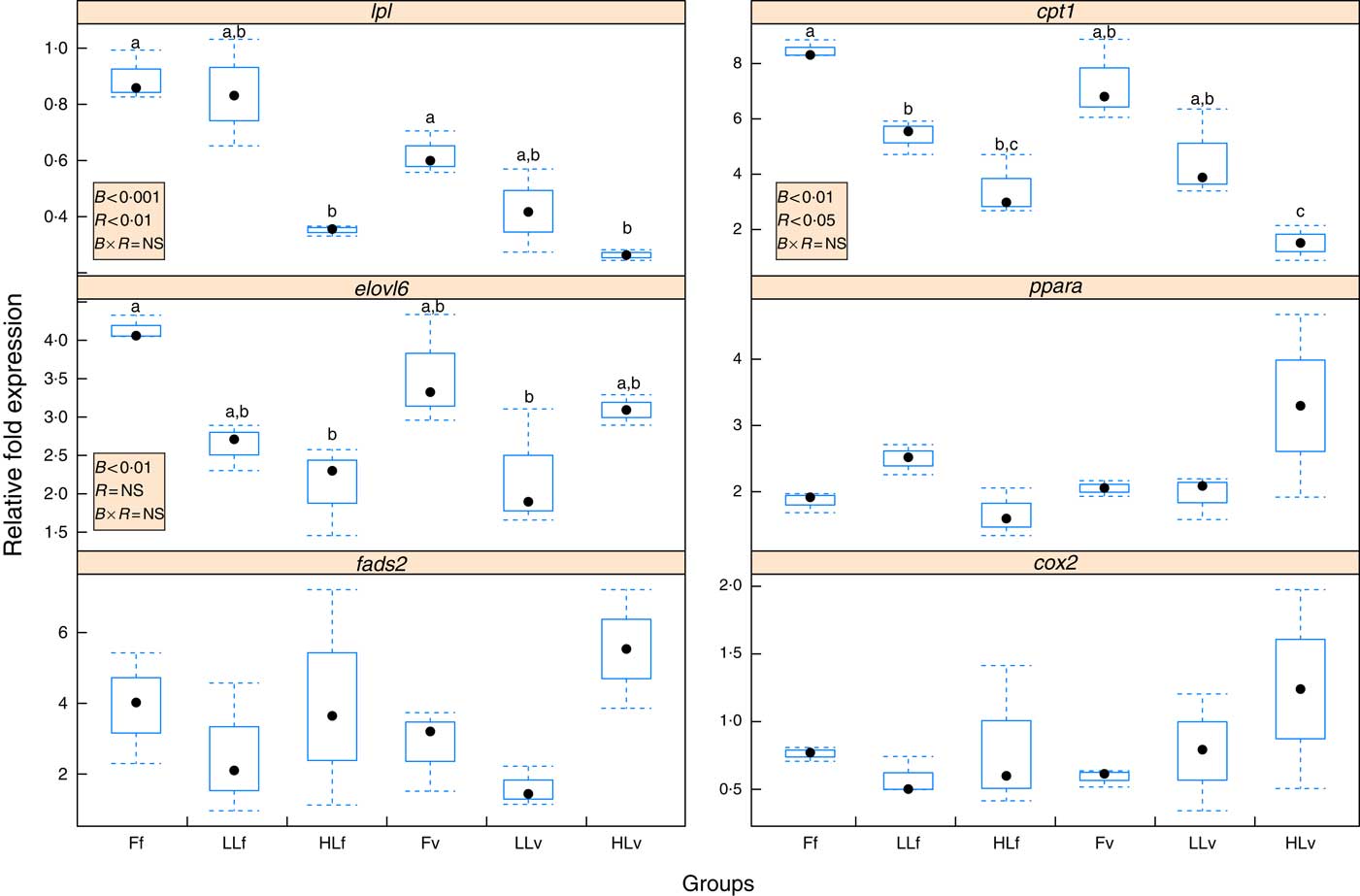

Reduction of LC-PUFA and increase in ALA and LA in broodstock diets lead to a significant (P<0·001) down-regulation of hepatic lpl (Fig. 2), which was significantly (P<0·01) emphasised by feeding the 4-month-old juveniles the v diet, based on plant ingredients and with low LC-PUFA and high ALA and LA contents. Thus, the lowest relative expression of lpl was found in HLv and HLf fish. Similarly, the origin of the fish based on different broodstock diets significantly (P<0·01) down-regulated hepatic elovl6 (Fig. 2), with the lowest relative expression of elovl6 found in LLv and HLf fish. Besides, elovl6 expression was significantly correlated to liver contents of 18 : 1:16 : 1 (r 0·89) and 18 : 0:16 : 0 (r 0·89), ratios of product:substrate of elovl6 activity. There was no significant effect of either the broodstock or the reminder diet on hepatic expression of fads2 (Fig. 2), but their values were positively correlated to hepatic levels of 18 : 4n-3 (r 0·86) and 18 : 3n-6 (r 0·8), products of the fads2 activity, as well as to the end desaturation products 20 : 5n-3 (r 0·98), 22 : 6n-3 (r 0·95) and 22 : 5n-6 (r 0·95). Besides, fads2 expression values were negatively correlated (r −0·52) to elovl6. Regarding fatty acid catabolism biomarkers, reduction of LC-PUFA and increase in ALA and LA acids in broodstock diets lead to a significant (P<0·001) down-regulation of hepatic cpt1b (Fig. 2), which was significantly (P<0·05) emphasised by the reminder diet. Moreover, the relative expression of cpt1b was highly correlated to 18 : 1n-9 (r 0·82) and negatively correlated to 20 : 5n-3 (r –0·62). No significant differences were found in the relative expression of ppara or cox2, which were negatively correlated (r –0·57 and r –0·73, respectively) to cpt1b expression.

Fig. 2 Box and whisker plots of relative fold expression (groups v. control sample) of six different genes after challenging 16-month-old gilthead sea bream individuals with high-vegetable oil and high-meal feeds for 2 months. lpl, lipoprotein lipase; elovl6, elongation of very long-chain fatty acids protein 6; fads2, fatty acid desaturase 2; cox2, cyclo-oxygenase-2; cpt1, carnitine palmitoyltransferase I; ![]() , maximum and minimum fold expression;

, maximum and minimum fold expression; ![]() , upper and lower quartiles;

, upper and lower quartiles; ![]() , median;

, median; ![]() , P values of two-way ANOVA; B, broodstock diet; R, reminder diet; B×R, interaction of these two parameters, ns, P>0·05; F, 100 % fish oil; LL, 40 % fish oil–60 % linseed oil; and HL, 20 % fish oil–80 % linseed oil; f, fish oil-based diet; v, reminder diet. n 3 for all the groups and genes. a,b,c Mean values with unlike letters were significantly different between each group, no indications mean no significant difference (P>0·05).

, P values of two-way ANOVA; B, broodstock diet; R, reminder diet; B×R, interaction of these two parameters, ns, P>0·05; F, 100 % fish oil; LL, 40 % fish oil–60 % linseed oil; and HL, 20 % fish oil–80 % linseed oil; f, fish oil-based diet; v, reminder diet. n 3 for all the groups and genes. a,b,c Mean values with unlike letters were significantly different between each group, no indications mean no significant difference (P>0·05).

The overall response showed similar trends for lpl, cpt1b and elovl6 expressions, whose values showed a high correlation in their relative gene expression between lpl and elovl6 (r 0·52), cpt1b and elovl6 (r 0·72) and lpl and cpt1b (r 0·74).

Discussion

In animal production, nutritional programming can be useful to improve offspring adaptation to farm conditions( Reference Mathers 74 , Reference Monaghan 75 ). As the limited availability of FM and FO is the main constraint in fish production, modulation of offspring phenotype through parental feeding for an improved utilisation of low-FM and low-FO diets can have important advantages( Reference Gotoh 31 ). Previous studies in gilthead sea bream have demonstrated that it is possible to improve low-FM and low-FO feed utilisation in the offspring coming from broodstock fed with increased substitution of FO with LO( Reference Izquierdo, Turkmen and Montero 45 ). This adaptation included the regulation of expression of genes for key metabolic enzymes in the liver such as fads2 ( Reference Izquierdo, Turkmen and Montero 45 ) or glucocorticoid receptor (gr) (S Turkmen et al., unpublished results). However, the persistence of these phenotypic or metabolic changes later in life had not been studied yet. The present study shows that replacement of parental feeding with moderate-FO with LO combined with juvenile feeding with low-FM and low-FO diets improves offspring growth and feed utilisation of low-FM/FO diets even when they are 16 months old: that is, when they are on the verge of their first reproductive season. Thus, among fish fed the low-FM/FO diet during the juvenile stages, those obtained from parents fed moderate LO levels showed the highest growth, denoting the persistent effect of parental nutrition. However, higher LO levels (80 % replacement of FO) in broodstock diets did not improve the growth of 16-month-old offspring, in agreement with previous studies( Reference Izquierdo, Turkmen and Montero 45 ). Thus, feeding broodstock with this high-LO diet markedly reduced spawning quality, larval survival and larval and juvenile growth( Reference Izquierdo, Turkmen and Montero 45 ), as a consequence of the deleterious effects of very low n-3 HUFA levels in broodstock diets( Reference Fernández-Palacios, Norberg and Izquierdo 47 ). The present study demonstrated the persistence of these negative effects of early EFA deficiencies during offspring life. On the contrary, 60 %-FO substitution with LO in sea bream broodstock diets did not negatively affect spawning quality or larval growth and produced 4-month-old juveniles with a better ability to utilise low-FM/FO diets( Reference Izquierdo, Turkmen and Montero 45 ), in agreement with the present study.

The above-mentioned growth improvement in 16-month-old fish obtained from broodstock fed moderate LO levels and the reminder low-FM/FO diet at 4 months of age was also accompanied by an enhanced utilisation of the low-FM/FO diet, as denoted by the better FCR, which could be related to the modulation of lipid and carbohydrate metabolism. There were no large differences in the proximate composition and fatty acid profiles of sea bream liver and muscle, reflecting the profound effect of the diet, regardless of the nutritional history of the different fish groups. Nevertheless, both broodstock diet and reminder diet had a significant effect on some major fatty acids in the liver such as 18 : 0, a terminal product of lipogenesis, and in the ratios 18 : 0:16 : 0 and, particularly, 18 : 1:16 : 1. Both 16 : 0 and 16 : 1 are substrates for elovl6, a key rate-limiting enzyme in the long-chain fatty acid elongation cycle and, therefore, the ratios 18 : 0:16 : 0 and 18 : 1:16 : 1, are indicators of the activity of this enzyme. These results are in agreement with the hepatic elovl6 expression, which was down-regulated by the increase in LO in the broodstock diets and was correlated inversely to the 16 : 0 contents in the liver and directly to the 18 : 0:16 : 0 and 18 : 1:16 : 1, denoting a significant post-transcriptional effect. Besides, LO increase in broodstock diets also increased the hepatic 18 : 0:18 : 1 ratios in the 16-month-old offspring.

These results are in agreement with the 16 : 0 reduction and 18 : 0:18 : 1 increase in mice models with Elovl6 disruption, which showed protection against a high-SFA diet-induced insulin resistance that lead to hepatosteatosis similar to that of wild-type mice( Reference Matsuzaka and Shimano 51 ). This protection was related to the restoration of hepatic insulin receptor substrate-2, suppression of hepatic protein kinase-C ɛ and restoration of Akt phosphorylation( Reference Matsuzaka and Shimano 51 ), overall, indicating a better utilisation of dietary carbohydrates under conditions of high-fat diet-induced insulin resistance. Indeed, insulin stimulates acetyl-CoA carboxylase that produces malonyl-CoA, which inhibits CPTI activity and affects utilisation of fatty acids and glucose as substrates( Reference Zammit 76 ). Thus, genes related to fatty acid oxidation, such as CptI, are down-regulated in mice with Elovl6 disruption( Reference Matsuzaka and Shimano 51 ), whereas up-regulation of CptI expression caused by intra-uterine growth restriction increases the risk of type 2 diabetes in adulthood( Reference Corbin 59 ). In agreement, in the present study, down-regulation of elovl6 was correlated to down-regulation of cptI, a rate-limiting enzyme for fatty acid oxidation in mitochondria( Reference Kolditz, Borthaire and Richard 77 ). Moreover, increased LO in broodstock diet and increased plant-protein and lipid sources in the 4-month-old reminder diet induced the down-regulation of cptI in the gilthead sea bream offspring, evidencing a long-term nutritional programming effect. A down-regulation of cptIb gene expression was also found in the liver of juvenile rainbow trout by vitamin supplementation at first feeding showing that nutritional interventions during developmental plasticity (larval period) may provoke longer-term effects later in life( Reference Panserat, Marandel and Geurden 78 ). CptI expression in the liver of fish is down-regulated by the reduction of dietary PUFA, particularly, LC-PUFA( Reference Xue, Hixson and Hori 57 , Reference Morash, Bureau and McClelland 79 ). Accordingly, cptII expression is also down-regulated in Atlantic salmon when dietary FO is substituted with VO( Reference Jordal, Torstensen and Tsoi 80 , Reference Torstensen, Ng and Tocher 81 ). In vitro studies in rainbow trout hepatocytes showed that pparα and cptI are up-regulated by MUFA and down-regulated by EPA, among other fatty acids( Reference Jordal, Torstensen and Tsoi 80 , Reference Torstensen, Ng and Tocher 81 ). In the present study cpt1b expression was highly correlated to 18 : 1n-9 and negatively correlated to 20 : 5n-3 in the liver. Besides, LO increase in broodstock diets significantly reduced the liver contents of 16 : 4n-3, an intermediate product of β-oxidation of EPA. In gilthead sea bream offspring, cptI expression in the liver is negatively correlated to ppara, suggesting that nutritional programing by LO reduces β-oxidation in the mitochondria but not in the peroxisomes. In mammals, parental feeding with a high-lipid diet lead to hypomethylation of four specific CpG dinucleotides in PPARa and the modification of the mRNA transcript in juvenile offspring( Reference Lillycrop, Phillips and Torrens 60 ). In gilthead sea bream fed a low-FM/FO diet, hepatic ppara is reportedly down-regulated, in association with retarded growth( Reference Benedito-Palos, Ballester-Lozano and Simó 82 ). In the present study, ppara in the offspring of HLv fed a low-FM/FO diet was not down-regulated and growth was even increased instead of being reduced upon parental feeding with LO.

In previous studies, parental feeding of gilthead sea bream with increased substitution of FO with LO significantly up-regulated fads2 in 1-month-old offspring (S. Turkmen et al., unpublished results). Similarly, in Senegalese sole, parental nutritional history affects growth performance and the expression of Δ4fad and elovl5 in the 2-month-old progeny( Reference Morais, Mendes and Castanheira 44 ). However, in the present study, fads2 of the 16-month-old fish did not show significant differences, which could be related to the strong influence of the very low-FM/FO diets fed to the 16-month-old sea bream. Indeed, fads2 relative expression was high in all fish and up to 5·5 times higher than the values in gilthead sea bream juveniles fed commercial diets containing high levels of FM and FO (data not shown). This is in agreement with the up-regulation of fads2 expression in fish fed reduced n-3 LC-PUFA diets rich in linolenic acid or LA( Reference Vagner and Santigosa 83 ). Dietary changes did not affect fads2 gene expression in Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua) either( Reference Tocher, Zheng and Schlechtriem 84 ), reportedly, related to the low dietary FO levels causing an up-regulation of this gene( Reference Izquierdo, Robaina and Juárez-Carrillo 49 ) or to a post-transcriptional regulation( Reference Izquierdo, Robaina and Juárez-Carrillo 49 ) as observed in other marine fish species( Reference Geay, Santigosa and Corporeau 85 ). Despite a slightly higher fads2 expression in offspring of broodstock fed LO and the reminder diet, individual differences among fish belonging to the same treatment lead to large variations with no significant differences among groups. Nevertheless, fads2 expression in the liver was correlated with hepatic contents in 18 : 4n-3, 18 : 3n-6, 20 : 5n-3, 22 : 6n-3 and 22 : 5n-6, intermediate and end products of desaturation activity by this enzyme( Reference Tocher 25 ).

The down-regulation of lpl expression in the liver of offspring from broodstock fed feeds with high LO levels, especially in those fish that received a low-FO/FM diet during juvenile stages, was correlated with reduced liver lipid contents, in agreement with the reduced lipid deposition associated with the down-regulation of lpl expression in the liver of the gilthead sea bream in previous studies( Reference Saera-Vila, Calduch-Giner and Gómez-Requeni 86 ). LPL is a determinant of lipid deposition or catabolism fate( Reference Leaver, Bautista and Bjornsson 58 ). Thus, nutritional programing through regulation of different genes within the pathway of lipid metabolism including lpl, elovl6 and cptI may prepare the offspring for a better utilisation of low-FM and low-FO diets, improving VO and VM utilisation and reducing the risk for hepatosteatosis described in gilthead sea bream fed these type of diets( Reference Montero, Tort and Izquierdo 87 ). As occurs in mammals, nutritional signals through parental feeding may improve offspring fitness at later stages, triggering a ‘predictive adaptive response’( Reference Gluckman, Hanson and Spencer 88 ). Thus, in gilthead sea bream, offspring of broodstock fed moderate LO levels and fed the low-FM/FO diet during juvenile stages showed improved final body weight and feed utilisation.

To our knowledge, this is the first study that demonstrates the profound effects of n-3 LC-PUFA profiles in parental diets on long-term effects in fish offspring even later in life: that is, in those on the verge of their first sexual maturation. In mammals, n-3 LC-PUFA supplementation in maternal diets reduces premature births( Reference Cetin and Koletzko 89 ) and enhances immune health( Reference Calder, Dangour and Diekman 90 , Reference Uauy, Corvalan and Dangour 91 ), growth, development and pancreatic tissue morphometry in the offspring( Reference Siemelink, Verhoef and Dormans 92 ). Besides, the nutritional programing effect of LC-PUFA on parental diet and the epigenetic regulation of gene expression has been also demonstrated in mammals( Reference Jaenisch and Bird 93 ), implying different epigenetic and physiological mechanisms including cell differentiation, neuro-hormonal regulation, etc.( Reference Hyatt, Gopalakrishnan and Bispham 94 ), which have not yet been demonstrated in fish. The present study has also pointed out that nutritional programing through parental feeding interacts with the feeding history during juveniles stages, as feeding a low-FM/FO diet for only one month when fish were 4-months-old affected gene expression and fish performance later when fish were on the verge of reproduction, in agreement with studies in other vertebrates( Reference Duque-Guimaraes and Ozanne 95 ). In summary, partial replacement of FO with LO in parental diets during gilthead sea bream reproduction induced long-term persistent effects on transcription of selected genes in the offspring, which regulate energy metabolism in the liver for a better utilisation of diets high in VO and VM. Moreover, these long-term effects on gene transcription are further enhanced by feeding the offspring juveniles with diets high in VO and VM, which improved growth and feed utilisation. Studies are underway to better understand the potential epigenetic, metabolic and molecular mechanisms involved in the metabolic conditioning of offspring through parental nutrition in gilthead sea bream.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Dr Sadasivam Kaushik for his suggestions on the final version of the manuscript. Acknowledgement is also owed to an anonymous referee who gave very valuable suggestions.

This work has been (partly) funded under the EU seventh Framework Programme by the Advanced Research Initiatives for Nutrition & Aquaculture (ARRAINA), project no. 288925.

S. T. conducted all experiments, analysed and evaluated all biological, biochemical and molecular analyses. Molecular biology samples were analysed by S. T. with the supervision of M. J. Z. All trials were designed by S. T., D. M. and C. M. H.-C., and M. I. supervised the entire work. L. R. was involved in the formulation and the preparation of the diets. The paper was written by S. T. and M. I.

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest. The views expressed in this work are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Commission.