Introduction

Kathryn Kish Sklar

We conducted our roundtable discussions of After the Vote by Elisabeth Israels Perry (EIP) during the COVID-19 pandemic and insurrection winter of 2021. In a series of Zoom calls that evolved into what one of us called “an advanced seminar on the Long Progressive Era,” we were glad to be historians, teaching and learning together, as American democracy weathered challenges not seen since the mid-nineteenth century and a global pandemic reminded us of our place on a shrinking planet. As witnesses to all that, we found special meaning in our work of interpreting change over time. A spirit of solidarity warmed our conversations.

Our areas of expertise reflect the combination of women’s history and political history found in After the Vote. Some of us are historians of women and public activism. Some specialize in aspects of citizenship and governance. Gradually, our discussions brought these fields together in a big tent around a center pole of democracy. Exploring the book’s detailed account of women in the administration of New York City’s municipal government in the 1920s and 1930s, we stayed close to the author’s evidence. When we discussed the relationships between micro and macro interpretations of Perry’s pages, we sometimes wished that she herself had offered more of the latter, but we remained impressed with the virtues of her micro analysis.

Methodologically, we came to consider Perry’s focus on women who held public office in New York City during Fiorello La Guardia’s mayoral years (1933–39) an effective means by which she embraced the diversity of those women. Rather than focusing on organizations or political parties, she included any and all women who held public responsibility—official or unofficial, paid or voluntary. In this way the book offers a fresh and unfiltered view of the capillaries of governance in an American metropolis during a turbulent and challenging decade. Through microbiographies of the women she discovered in the corridors of city governance, Perry charted their connections with institutions and expertise that illuminated their paths into public service. Highlighting these connections, Perry argued that after 1920, women in city government promoted social agendas that women’s organizations had long embraced. This continuity from 1880 to 1940 prompted her to advocate the chronological extension of the Progressive Era to 1940, which we are calling the “Long Progressive Era.”

Our mandate from the Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era tasked us to consider the legacy of Elisabeth Israels Perry as a historian as well as to evaluate After the Vote, which she completed just before cancer claimed her life in November 2018. During her tenure as SHGAPE president (1998–2000) and for years afterward, Perry welcomed new members personally, adding substantially to the society’s diversity and vitality. In her presidential address, she pointed to the inadequacies of the usual chronological limits of the Progressive Era. Drawing on her 1987 biography of her paternal grandmother, Belle Moskowitz, she declared that “taking women’s efforts at reform seriously requires widening the chronological boundaries of the Progressive Era.”Footnote 1 After the Vote consolidated that view.

This introduction comments on the chronological value of the “Long Progressive Era” and introduces essays by our roundtable participants. We try to reproduce some of our lively interactions with comments on one another’s essays, below. To keep the book present, each essay begins with a quote from the book. All the illustrations in this roundtable can be found in After the Vote, except the portrait of Belle Moskowitz, which appears in EIP’s biography.

Our discussions drew on and melded our respective areas of expertise in the decades from 1880 to 1940—including women and social movements, women’s political activism, racial formation, ethnic radicalism, citizenship, and state formation. Our weekly conversations over three months were exciting and productive; we were sorry to see them end. Anchored in the specificities of After the Vote, we drew new conclusions about issues that mattered greatly to us. Most notably, we became convinced of the value of the “Long Progressive Era” as an effective lens through which to analyze American political history as well as women’s political activism.

Perry’s excavation of “municipal administration” during La Guardia’s mayoral years illuminates the historic opening that he created for women’s participation in city governance. Yet women’s expertise for this work was nothing new. In case after case, Perry’s evidence in After the Vote demonstrates that the women who joined La Guardia’s administration brought talents developed decades earlier—in the admission of women to the city’s law schools, in work on labor-related commissions, and in the prominence of women’s activism in defense of African American civil rights.

Most historians of American politics and society draw a line at 1920 that separates the pre- and post-1920 eras. What might the “Long Progressive Era” mean for that line? Our discussions acknowledged the abundant discontinuities that mark the 1920 divide, including “the closing of the gates” to immigrants in 1924, the political hegemony of capitalism over socialism symbolized in the return to “normalcy” with Warren Harding’s 1920 election, and the waning of Victorian values about sex and morality as expressed by the flapper generation. But Perry’s book helped us understand the extent to which the basic framework of democracy was renewed and extended in the 1930s from institutions, activism, and values that emerged around 1900. And her work shows that coalitions of women of diverse race, class, and ethnic backgrounds did much to create those institutions, values, and activism.

Seen from this perspective, the continuities in the fight over the Progressive Era’s unfinished business in the 1920s and 1930s are at least as significant as the discontinuities. And our views of “normalcy” and flappers might broaden by considering how those post-1920 cultural statements originated in changes during the first decades of the twentieth century. This long-term perspective of women’s activism seemed emphatically more useful to us than the “wave” metaphor often used to describe women’s entry into public life. Ebbs and flows do occur, but the context resembles a barn raising more than an ocean beach. Lasting change happens and becomes the basis for future innovation.

Historians’ turn to the history of capitalism also struck us as relevant. In these pages in 2020, Gabriel Winant argued for the value of viewing the Gilded Age and Progressive Era within the larger chronology of capitalism—as stages in a longer arc of inequalities that extend from the early nineteenth century to the present day.Footnote 2 He emphasized the importance of seeing the New Deal within that longer arc. Our conversations added to that insight. Insofar as the sea change called “progressivism” remains an important source of our democracy’s contested but enduring vitality, what we mean by “progressive” invites new approaches that expand our chronological understanding of its reach back into nineteenth-century rights campaigns and forward into current views of inequality, including what constitutes a “fair wage.”

Our discussions intersected with my current work on Florence Kelley and the social origins of minimum wage legislation in the United States between 1835 and 1941. As head of the National Consumers League (NCL) and its scores of robust local leagues from 1899 to 1932, Kelley exemplified the Long Progressive Era, establishing minimum wage legislation for women in a dozen states by 1923, when the Supreme Court declared the Washington, D.C. law unconstitutional.Footnote 3 Kelley died in 1932, but her protégé Frances Perkins carried the wage campaign forward (fig. 1).

Figure 1. Frances Perkins by a fire escape during her work for the Factory Investigation Commission, circa 1911. Frances Perkins Papers, Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University.

After the Vote charts the rise of Frances Perkins in New York’s reform activism (41–48). Perkins was already working closely with Kelley as executive secretary of the New York Consumers League in 1911, when she witnessed the death of more than a hundred garment workers, most of whom were young women, in the Triangle Shirtwaist factory fire. “People had just begun to jump when we got there,” she later remembered.Footnote 4 Standing in the crowd for hours, she observed the grisly scene in which wage earners leapt from ninth-floor windows, prevented from escaping the flames that engulfed their workshop by exit doors locked to prevent them from stealing the goods they were sewing. Firemen watched helplessly from the ground. The tragedy led to the creation of the New York Factory Investigating Commission, on which Frances Perkins served. In 1919, the state legislature created an industrial commission to administer and enforce safety rules, and Governor Al Smith appointed her as one of three commissioners, her responsibility being to supervise the bureau of statistics and information and the bureau of mediation and arbitration. A few months into her work, fellow commissioner James Lynch declared, “From the work that Miss Perkins has accomplished I am convinced that more women ought to be placed in high positions throughout the state departments.”Footnote 5 In 1929, Governor Franklin Roosevelt appointed Perkins head of the state industrial commission. And as president in 1933, Roosevelt appointed her secretary of labor, expecting her to supervise the drafting and successful enactment of what became the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938. In that capacity, Perkins included minimum wage provisions for men and women, drawing on the proven popularity and effectiveness of state minimum wage statutes for women and overseeing the act’s approval by the Supreme Court in 1941.Footnote 6

The NCL’s minimum wage campaign appears in After the Vote in Elinore Herrick’s story, which took her from factory work to the New York Consumers League to La Guardia’s administration and, finally, through Perkins, into FDR’s national government (205–8). Scores of stories about other social and political agendas populate Perry’s pages with examples of the long-term transformative effects of women’s public activism. The book’s excellent index is a guide to this process, including, for example, the struggles that created institutions like the city’s public libraries and the City University of New York. Although Perry does not mention it, her focus on municipal administration amplifies an argument begun by the Progressive Era icon Jane Addams (1860–1935). In an article published in the American Journal of Sociology in 1905, Addams called for what La Guardia’s appointees often achieved—a shift in modes of governance “from those which repress” to those that release “the power of the people.”Footnote 7

Our roundtable conversations noted the ongoingness of similar struggles today and the ongoing relevance of historians’ work in clarifying the working parts of democratic politics and government, including municipal administration. We even agreed that such work by historians might be seen as “care work for democracy,” resembling Perry’s care work of rescuing post-1920 women political activists from historical oblivion.

***

Mason Williams helped us keep our eyes on La Guardia’s efforts to stabilize the city during the social, economic, and political crises of the Great Depression. His roundtable remarks offer riveting examples of how women’s civic engagement kept progressive reform ideas alive in the 1920s and even more vital in the 1930s. Although women’s political expertise did not always (or even usually) lead to visible power in partisan politics, women did exercise leadership and gain access to power, finding routes that EIP charted and that one of our roundtable conversations described as “water over and around rocks that did not move.” Williams’s essay suggests what a new world might look like if political history embraced all the layers of political activism where women were engaged, and did not stop with the white men at the top.

In her roundtable essay, Liette Gidlow explores the personal dimensions of EIP’s career as well as the important history that she uncovered. One of our early conversations speculated on ways that Perry’s own story sustained her originality. Trained as a historian of seventeenth-century France, with a PhD from UCLA in 1967, Elisabeth Israels married Lewis Perry, a historian of antebellum social reform, in 1970. Her dissertation on the Edict of Nantes was published in 1973, and she and Lew sought jobs where both could be employed as they raised their two children, plus a son from his earlier marriage. In that process, she retooled as a historian of American women. Learning that no one could write a proper history of the importance of her paternal grandmother, Belle Moskowitz, because she left hardly any personal papers, EIP plunged into the relevant archives, interviewed key sources, and authored her pathbreaking book Belle Moskowitz: Feminine Politics and the Exercise of Power in the Age of Alfred E. Smith (1987).Footnote 8 This archival work laid the foundation for After the Vote.

Melanie Gustafson takes us into the partisan political context of women’s political activism in New York City in the 1920s and 1930s. She notes the frequent rebuffs with which party bosses (not just in Tammany Hall) rejected women’s inclusion in their ranks and highlights how frequently women exercised power in ways that deflected attention from themselves. Historians have treated this as a cultural expression of gendered behavior, but Gustafson asks a series of penetrating questions about the structural barriers to women’s engagement in partisan party politics.

Perry’s evidence depicts opponents as well as proponents of women’s activism and their social justice agendas. Our discussions included my own view that opponents gained power from the gendered construction of American political culture, which since the 1830s has periodically honored white manhood as a way of obscuring urgently problematic social divisions and inequalities. First in Andrew Jackson’s Democratic party during the expansion of racial slavery between 1830 and 1860, then in Theodore Roosevelt’s Republican party during the expansion of industrial capitalism between 1880 and 1920, and recently in the Trump era, political leadership has sought to forge masculinist loyalties that deflect pressing race and class injustice.

Nevertheless, as Perry emphasized, women gained access to public life through local groups that embodied their difference from men, initially advancing social issues connected with local communities—Black women by advancing the rights of African Americans, white middle-class women through the “social work” of social settlements. Women became as good as men at the business of democracy, but it was not easy for genderless norms to emerge in the twentieth century, especially at the national level. Perry did not live to see Kamala Harris’s election as vice president, but she would have been quick to understand Harris’s expertise as anchored in California and sustained by the national emergence of other locally powerful women of color.

Perry emphasized the importance of class, race, and ethnic differences among women in an earlier essay titled “The Difference That Difference Makes.”Footnote 9 Essentialist notions about gender were not part of her toolbox. Rather, she showed how gender functioned as an important ingredient in the “feminist politics” of her protagonists. Shaped by the public activism of the suffrage movement, then drawing on the enfranchisement of New York women in 1917 and the adoption of the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920, women expanded their citizenship to include access to public office. And this new “supply” of women’s activism matched the city’s need for their expertise during the 1920s and 30s, decades of political, social, and economic instability. The vibrant tradition of women’s organizations gave rise to groups that continued to develop and promote women’s political skills, such as the League of Women Voters in 1921 and the National Council of Negro Women in 1935. And individuals reached across generations to teach one another. As Perry noted, “In the 1920s, Belle Moskowitz taught Eleanor Roosevelt the basics of running a partisan women’s political campaign” (45).

Although “the difference that difference makes” was important to Perry’s theory and practice as a historian, she did not organize After the Vote’s chapters by women’s differences. Race, class, and ethnic differences appear incidentally in the stories about women who achieved public office. Readers encounter the public activism of individual African American women such as Eunice Hunton Carter, the daughter of Addie Hunton and a graduate of Smith College and Fordham University Law School, who became a deputy assistant district attorney (198–201), but Perry did not depict the larger landscapes of African American women’s public activism. We learn that Black women were politically active in New York City since at least the founding of the National Association of Colored Women in 1896; that La Guardia, known as “a friend of the Negro,” was endorsed by W. E. B. Du Bois in The Crisis in 1933; and that as mayor, La Guardia appointed the city’s first Black woman magistrate, Jane Bolin, in 1939. Readers are likely to want to know more about the repressive social inequalities that led to violence in Harlem in 1935, which Perry described as leaving three Black citizens dead and nearly sixty injured. La Guardia appointed Eunice Carter to a commission to investigate the causes of the violence. Finding out more about that commission might be a rewarding teaching strategy. Another might be to construct a unified account of the separate stories of the politically active Black women depicted in After the Vote.

Kim Warren led our thinking about these and other matters related to Black women. Her roundtable contribution offers many astute points of entry into Perry’s treatment of Black women in After the Vote, beginning with her call for “new methods and questions … if we want to tell a more complete story about the past.” Warren also reminds us of the value of local history as a way to understand “intersectional identities” as a force in women’s political activism.

Annelise Orleck comments on the enduring prominence of ethnicity and religion among women political activists in the city. Just as Perry did not organize a chapter about Black women, she also downplayed ethnicity among the city’s politically active women, referring only occasionally to Jewish and other ethnic identities. We learn that La Guardia’s mother was Jewish, born in Trieste, and that he challenged an opponent to a debate in Yiddish (177). But Perry often did not bother to identify as Jewish many women whose prominence in the city’s politics drew on their Jewish identity—including Lillian Wald, head of Lower Manhattan’s Henry Street Settlement, which she launched in 1893 for eastern European Jewish immigrants with funding from German Jews. Wald strongly supported La Guardia, representing the continuity between generations of Jewish women actively engaged in the city’s politics.

In the concluding portion of our roundtable, Chris Capozzola highlights the importance of citizenship as a social activity. This theme pervaded our conversations, sparking a steady flow of ideas about the collective enterprise of democracy and the organizations that nurtured women’s political activism. The social dimensions of citizenship inform every page of After the Vote, often implicitly rather than explicitly, presented in evidence rather than theorized. In this regard as in so many others, the book opens doors for future research and writing.

Mason Williams

Great Scott … you women put me on the spot/You did it as well as I. … Girls, raise your right hands. I’m going to swear you all in as commissioners.

— Mayor Fiorello La Guardia, represented in the Women of the La Guardia Administration’s performance of Fifty Women and One Man (1937)Footnote 10

State-building, administrative modernization, and the expansion of government’s functions and capacities have long been major themes in the political history of interwar New York. Historians and political scientists have focused on a number of sometimes-interrelated developments: Fiorello La Guardia’s war against the Democratic patronage machine and his implementation of civil service reform, his greater emphasis on expertise, and the idea of “merit” rather than political preferment as a basis for hiring municipal workers; the development of new institutions with new capacities, such as Robert Moses’s Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority, the Port Authority, and the New York City Housing Authority; and the expansion of the state’s role in everyday life (namely, by providing public health clinics, recreational spaces, public arts and education programs, and more.)Footnote 11 New York’s experience, though distinctive in some respects, in many ways mirrored broader developments during the New Deal era.

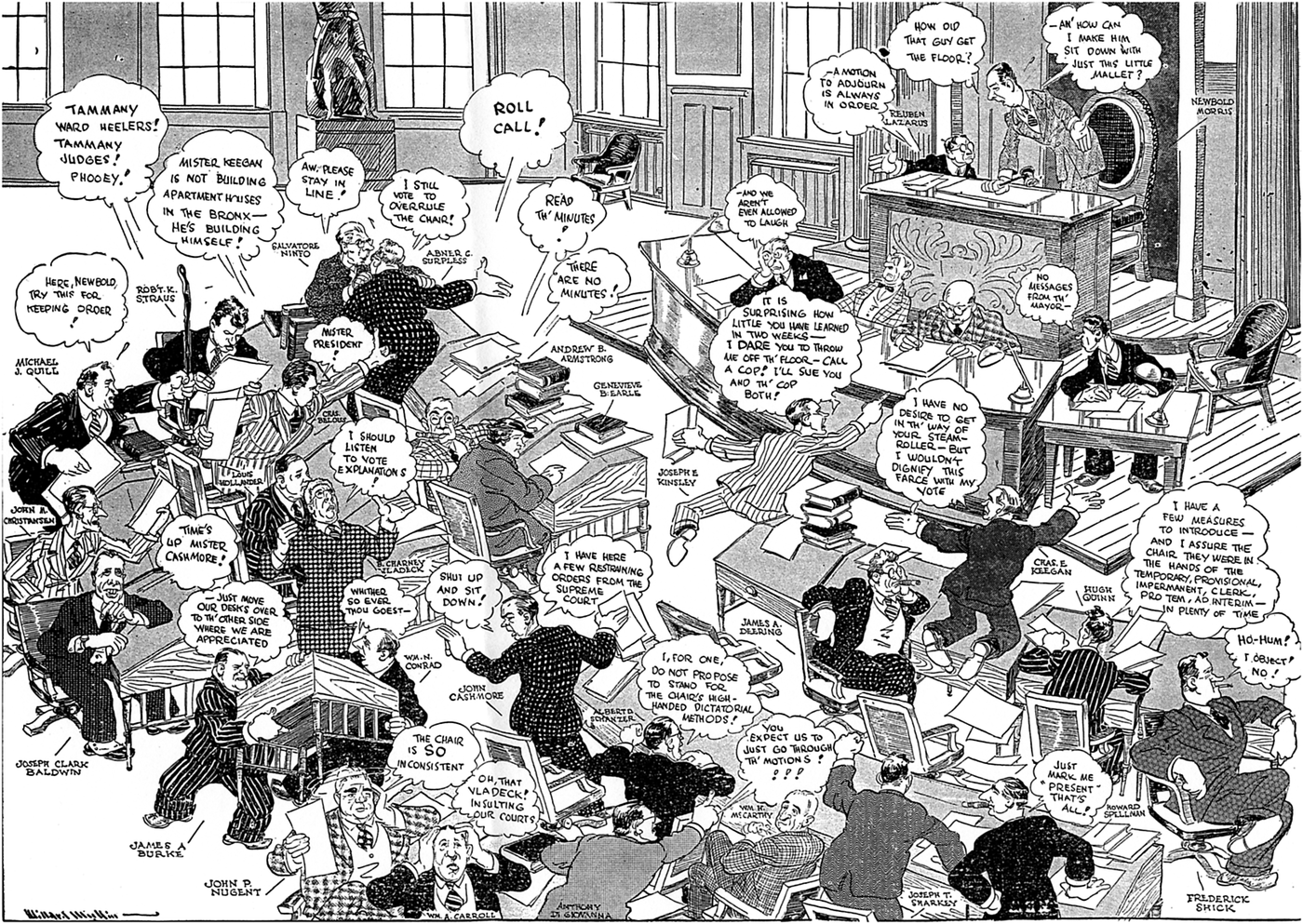

One of Elisabeth Perry’s great contributions in After the Vote is to shine a light on the people who carried out the day-to-day work of building and reforming New York’s municipal government. Everyone knows about Fiorello La Guardia, Robert Moses, Franklin Roosevelt, and Herbert Lehman, but aside from a few scattered references to the “Depression geniuses” who made New York’s government work from the New Deal into the 1960s, relatively little scholarship has focused on the everyday work of rebuilding the state. EIP highlighted that work—and the central role of women in performing it. Though the extent of women’s work was often obscured by gendered structures of power, many New Yorkers were well aware of it: depictions like the Fifty Women and One Man sketch and the cartoon from the New York World-Telegram depicting City Council member Genevieve Earle hard at work as the rest of the chamber descends into chaos garnered laughs because their audiences recognized that they contained more than a grain of truth (fig. 2).

Figure 2. New York World Telegram, January 24, 1938. Genevieve Earle is depicted as quietly seated in the center, trying to work.

Perry’s narrative begins with a profile of Pearl Bernstein, a daughter of Jewish immigrants who grew up in early twentieth-century Harlem before attending Barnard College, where she met future FDR brain truster Raymond Moley. Moley and his colleague Joseph McGoldrick (later city comptroller during the La Guardia years) helped her get a three-month job at the Citizens Union, which led to a position at the League of Women Voters, in which capacity she became an expert on the city budget. Her detailed knowledge and her nonpartisan credentials made her a natural fit with La Guardia’s brand of reform politics. (Both the Citizens Union and the League of Women Voters operated on a nonpartisan basis, and La Guardia, having won on an anti-machine message in 1933, was eager to minimize partisan appointments.) Shortly before his inauguration, La Guardia asked Bernstein to accept the newly created position of secretary of the Board of Estimate, hoping to bring expert knowledge into the deliberations of the city’s most powerful lawmaking body. Over the next three decades, Bernstein would serve in a variety of posts, including as a “critical guiding force in the creation of the City University of New York” (13). Public servants like Bernstein, After the Vote makes clear, helped build the machinery that translated reform into substance.

The book also helps scholars to better understand the chronology of reformist state-rebuilding. It shows—as Perry also did in her previous work on Belle Moskowitz—that women were able to carve out spaces for reform in the era of Democratic hegemony. In addition to the many figures who came into city government through La Guardia’s campaign for reform, Perry related the stories of women like Anna Moscowitz Kross, who began her long career in public service as assistant corporation counsel under New York City Mayor John F. Hylan and won appointment to the magistrate’s bench by the last of the old-time Tammany mayors, John O’Brien. More important, After the Vote documents the role of feminist reformers in carrying Progressive Era reform ideas into the New Deal. As La Guardia himself was fond of noting, much of what his administration accomplished—be it administrative modernization, public works projects, or new social programs—drew on ideas that had been circulating for decades. But who carried those ideas forward into the 1930s, when La Guardia’s ascent and the infusion of resources from Roosevelt’s New Deal allowed them to be put into operation? Scholars have long known that women played crucial roles in the development of social-scientific knowledge in the United States as well as in the transatlantic exchange of social policy ideas on which the New Deal drew.Footnote 12 By showing how women’s civic engagement kept progressive reform ideas alive in the 1920s, Perry gave us a better sense of the specific networks by which reform ideas were transported across the era of Tammany hegemony—indeed, how organizations such as the League of Women Voters continued to build expertise in the Progressive Era fashion through the 1920s.

Finally, while many important works examine feminized aspects of the state in the New Deal era, as a general statement, I think it is safe to say that work on urban state-building during this period has tended to focus on masculinized functions of government. The focus on Robert Moses in the literature on New York is one obvious example, but the tendency is also evident in more recent work that stresses the role of businessmen and civic boosters in interwar state development. By putting women at the center of the story, Perry demonstrated how central consumer politics, labor relations, the politics of vice, the domestic relations courts, and even the building of the Municipal Reference Library were to New York’s local New Deal: the New Deal painted on a far broader canvas, and feminist reform visions were integral to the New Deal state.

This, in turn, gives us a more textured and ambiguous view of liberal reform in Depression-era New York. For example, La Guardia is often (and rightly) viewed as a champion of organized labor—and Perry showed how women like Anna Rosenberg contributed to the empowerment of unionized workers in the 1930s. But Perry also demonstrated how La Guardia clashed with women such as Anna Kross and Dorothy Kenyon on how to approach the governance of sex work. When Kenyon, whom La Guardia appointed deputy commissioner of licenses, suggested that sex workers should be decriminalized and licensed, EIP wrote, “La Guardia made it quite clear that he would never condone such an approach” (188). Kenyon and La Guardia also squared off over burlesque theaters: Kenyon opposed giving the commissioner of licenses censorship powers over the theaters; La Guardia, in the name of a “cleaner city,” refused to renew their licenses, throwing thousands of people out of work. By focusing on forms of work that are often overlooked in broad stroke narratives of the New Deal era, After the Vote suggests how the uplift of certain forms of labor was intertwined with practices of exclusion and punishment.

Melanie Gustafson: Reply to Mason Williams

One reason I agreed to join this roundtable was because I feared that Elisabeth Perry’s After the Vote would be ignored in conversations emanating from the centennial celebration of the Nineteenth Amendment. So, thank you to this journal and to Kitty Sklar for bringing notice to this important work at a time when so many of us are thinking about the progressive legacies of the woman suffrage movement.

Another reason I joined this roundtable—our “advanced seminar on the Long Progressive Era”—was for the opportunity it afforded me to read books by my roundtable colleagues. It was a joy to read Mason Williams’s City of Ambition alongside Perry’s After the Vote. Williams’s analysis of how La Guardia’s access to federal funds enabled his administration “to accomplish feats that seemed to many New Yorkers to be beyond the reach of city government” sits nicely beside EIP’s investigations into how women acted as important “gatekeepers, planners, litigators, and policymakers” and how the women, as Williams writes here, “helped build the machinery which translated reform into substance” (185). La Guardia chose these women, as he chose men like Robert Moses, because they “demonstrated a level of competence no one could question” (213). I can now see Rebecca Rankin, an important person in Perry’s book, carefully organizing and preserving the paperwork created by Robert Moses, an important figure in Williams’s study. Rankin was not building bridges or city parks, but she did convince La Guardia to finance a building for the municipal archive, and La Guardia’s successor, Mayor William O’Dwyer, carried through on that project and placed Rankin in charge. As After the Vote shows us, the municipal archive was part of the city’s larger modernizing effort, which, because it saved time and money, enhanced women’s administrative success. Williams argues in his book that these men and women were fashioning “an infrastructure which would permit commerce in the city to flourish and develop, but also to provide goods and services that would increase the common wealth of the city and the happiness and freedom of opportunity of its citizens, families, and communities.” That “but also” is important. As Perry showed, feminist progressives like Rankin kept alive progressive reform ideas that made the city a better place for all its citizens.

In one of my final discussions with Mason about his work and Perry’s book, he said that the Municipal Archives of the City of New York has “shaped the production of historical knowledge about the La Guardia years.” This got me thinking about how EIP’s research, which already contributes so much to the histories of women and politics and New York City politics in particular, might advance the work of historians involved in the “archival turn,” a methodology that considers how political, social, and economic conditions influence the processes of archival preservation. I wish Elisabeth were here to join in on such conversations.

Liette Gidlow

Though the woman’s vote may not have immediately transformed national politics, winning it was nothing short of transformative … for women especially (and at first) at local levels.

—Elisabeth Israels PerryFootnote 13

Even in broad-minded New York, woman suffrage had its limits. In the 1920s, the city teemed with women who possessed valuable job skills as a result of their work in the state’s protracted struggle for suffrage or in one of the city’s many movements for progressive reform. Their passion for politics and public service did not disappear when they gained the vote. A few, such as Rebecca Rankin, New York’s municipal reference librarian from 1920 to 1952 and the founder of the city’s first professional municipal archives, forged satisfying careers in the service of the causes they cared about. Many more, however, struggled to find steady, meaningful work, jobs that offered a path for advancement and paid a proper paycheck. Access to the voting booth allowed women to join the mass of male citizens who selected public officials and considered ballot issues, but it rarely gained them access to the corridors of power where political decisions and public policies were made and laws were enforced. Elective office, party leadership, judgeships, leadership positions in city, state, and federal agencies—in the aftermath of suffrage, jobs such as these remained almost totally out of reach for women, no matter how qualified.

Again and again, in her labors and in her life, Elisabeth Israels Perry addressed the problems that women have faced finding suitable work. Belle Moskowitz, her grandmother and the subject of her second book, would have understood. Moskowitz became Al Smith’s most trusted strategist and aide and guided all four of his successful campaigns for New York governor as well as his unsuccessful 1928 presidential bid. The New York Times declared that Moskowitz had wielded “more political power than any other woman in the United States” when it reported her 1933 death on the front page, above the fold. Her clout, however, came at a price: the girl who had sparkled in her teens as a dramatic reader, whose trained voice “could ‘fill a room,’” gained her extraordinary influence in politics by purposely deflecting attention from herself. During high-powered meetings in the governor’s office, Moskowitz sat in the corner and knitted rather than participating in discussions, and yet her influence was so great that Perry named her “the author of many of Smith’s social programs.” It’s hard to imagine a man adopting self-erasure as a strategy for career advancement (fig. 3).

Figure 3. Photo image of Belle Moskowitz by Lewis Hine, circa 1931. Belle Moskowitz Papers, Linda Lear Center for Special Collections and Archives, Charles E. Shain Library, Connecticut College.

After the Vote explores the careers—or the careers that might have been—of a generation of activist, feminist women in post-suffrage New York. Through painstaking archival work conducted incrementally over many years, Perry recovered the accomplishments and strivings of talented women whose public lives, like her grandmother’s, had been all but erased. Many of the success stories spotlight women of means who functioned as full-time professionals for reform organizations though they were not paid staff. Harriet Burton Laidlaw, for example, was married to a Wall Street broker and became the only female member of the board of directors of Standard and Poor’s after his death in 1932. As a suffragist, Laidlaw wrote the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) blueprint for local activists, “Organizing to Win by the Political District Plan,” a program that laid out the tactics local suffragists should use to put pressure on public officials. After the vote was won, Laidlaw advocated election law reform, prohibition, and U.S. entry into the League of Nations. Free of the need to earn a living, women like Laidlaw treated reform work as if it were a job.

Perry also identified a number of self-supporting women who established distinguished careers. Take Pearl Bernstein, whose efforts to standardize administrative procedures across New York’s four municipal colleges paved a path for the creation of CUNY. After she graduated from Barnard in 1925, Bernstein endured economic precarity for years and pieced together short-term jobs in and out of her field while volunteering at the New York League of Women Voters. Eventually the League hired her to keep an eye on the Board of Estimate, where she became an authority on the city budget. Soon she was hired into leadership posts with the Board of Estimate and then the Board of Higher Education. After helping to launch CUNY, Bernstein served for three years as the institution’s “de facto chancellor”—until, that is, “the board appointed a man to the post” in 1960 (13).

But persistence and pluck will only take a girl so far. EIP was supremely sensitive to the careers cut short, the talent untapped, the city’s needs left unmet when skilled women with a commitment to solving public problems could not find or keep suitable work. In 1919, Mayor John Hylan took the step of appointing Jean Hortense Noonan Norris, a former suffragist and the president of the National Association of Women Lawyers, to the bench of the city’s Women’s Court as the city’s first female magistrate. The courthouse crowd and the broader public scrutinized her performance closely, a common situation when a “first” breaks a barrier. So when Norris made some political missteps—mistakes that paled in comparison to the rampant corruption that prevailed in other judges’ courtrooms—she was removed and replaced by a man and the whole experiment was deemed a failure. One of the investigating attorneys who brought Norris down summed up his attitude in a 1929 speech to a Brooklyn Jewish women’s group: women “are not fitted to lead in what we call the professions. A woman lawyer, for instance, is a misfit in a courtroom” (121). Apparently, so too was a woman judge. Chiefly because of discrimination, Perry concluded, talented women “rarely climbed as high” or stayed as long “as they wanted to” (3).

Whether inventing unofficial jobs or drawing a paycheck, and whether they enjoyed long career paths or worked only for a short time, the contributions of this generation of women were substantial. Attorney Caroline Klein Simon’s 1928 investigation of abuses in the municipal courts helped shape the eventual overhaul of that system. Elinore Herrick’s contributions to New York’s minimum wage law were so significant that, after Governor Herbert Lehman quickly signed the bill, he called her to apologize; in his haste, he had failed to invite her to the signing ceremony for what he called “her bill” (207). Child welfare measures, school improvements, anti-corruption initiatives—on these issues and others, women’s expert work advanced essential reforms. They rarely got the credit they deserved, but their accomplishments were real. Perry brought the receipts for her central claim: “Even if all the names on office doors and enacted bills are male, the women were there too” (6).

The women were there, but this book does more than recover the stories of women who worked to advance public causes after suffrage was won. It also refutes the conclusion of contemporary critics—and a number of suffrage historians since—that the Nineteenth Amendment failed to accomplish much of note. If enfranchisement failed to catapult women into high office or quickly deliver splashy policy changes, Perry’s deep research makes clear that the blame lies not with female voters but on the formidable resistance that women continued to face when they tried to contribute to public life. Confronted with such obstacles, their remarkable achievements in local and state government are evidence not of failure, but of success. Perry’s findings that women shaped New York politics and policies in important ways adds to a growing body of scholarship that shows that women’s political effectiveness, success in winning office, and voter turnout after 1920 varied widely by locality, state, or region. In light of such evidence, the generalization that woman suffrage failed to make much difference is hard to sustain.

The workplace discrimination that accomplished women faced after the vote is something that Perry knew well. She earned her PhD in 1967, before the women’s liberation movement had opened the doors to the academy a bit wider. She spoke openly about how her efforts to find a position that could support her research and also accommodate her husband’s well-regarded career as a historian and their shared responsibilities for raising their children took her to Buffalo, Nashville, Bronxville, Boulder, Bloomington, Iowa City, Cincinnati, and back to Brooklyn before she and Lew job-shared an endowed chair at St. Louis University. Perry never knew her grandmother; Belle passed before Elisabeth was born. But surely it was not lost on her that grandmother and granddaughter, almost a hundred years apart, shared the experience of navigating sexism in the workplace.

Kim Cary Warren: Reply to Liette Gidlow

Liette Gidlow reminds us how important Elisabeth Perry’s book is within the larger context of suffrage historiography. After the Vote provides a sound voice that explains that the Nineteenth Amendment provided a catalyst for many types of women’s work and influence, even if it did not propel women to vote in high percentages or as a united bloc. As Gidlow tells us, Perry’s deep dives into archival material leave us with a history of female influence in New York City that came from organizational leaders, librarians, and assistants. Although EIP tells us about stalled careers, Gidlow reminds us that women voters were not to blame. In fact, their limited work—“the careers that might have been”—should be celebrated in spite of the structural barriers that women faced in the professional and political worlds of New York City. With such a pervasive and discriminatory culture as that which surrounded women in New York, it is a wonder that any of them could move forward with their work, let alone become a lawyer, judge, or “de facto chancellor” of CUNY.

Gidlow points to After the Vote’s detailed narratives to help us understand how measures of voter turnout after 1920 reveal a limited view of women’s political activism. Gidlow’s own important research in The Big Vote: Gender, Consumer Culture, and the Politics of Exclusion, 1890s–1920s is also essential to that activist historiography, explaining that being a citizen did include improving access to the ballot box. However, being a citizen also relied on get-out-the-vote and other campaigns along with civic education that lent power to middle-class women. Like Gidlow’s work, Perry’s scholarship is vital to our understanding that women’s political effectiveness is both broadly defined and ever-changing across the decades of the twentieth century. To find the ways that women shaped New York politics and policies, Gidlow reminds us, we have to respect Perry’s method of looking at a longer trajectory of women’s activism. We cannot simply look at voting patterns, even though voting has always mattered as a civic duty. The ways in which women enacted civic duties through their education, their job positions and their voluntarism had a lasting effect on their communities—and still does.

Melanie Gustafson

It’s as good as a theatre!

— Radcliffe student at conclusion of New York City debate between Republican Rosalie Loew Whitney and Democrat Anna Moscowitz Kross, October 1921Footnote 14

Much of the narrative outline of Perry’s After the Vote will be familiar to those with scholarly knowledge of late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century women’s political activism. For those who need an introduction, this is what we know: women organized massive coalitions to win the right to vote during the decades from 1870 to 1920, and they generated national and local reform agendas that were shaped by women’s civic and social organizations. After 1920, women carried these reform agendas into partisan and nonpartisan politics. Many worked on behalf of political candidates and supported sitting politicians whom they knew would advance their policy goals. No woman’s voting bloc emerged, despite such fears or hopes and regardless of efforts by some to remain nonpartisan. Republican and Democratic women formed a variety of political clubs to advance their chosen parties and struggled to find places on the inside of party organizations run by men. Some women sought political offices for themselves, at times women voters crossed party lines in support of these women candidates, and inevitably both women candidates and women voters faced questions about “sex in politics” (57).

Yet by digging deeper into New York City’s political landscape, After the Vote changes the narrative of women’s entry into politics as voters. Women’s presence was “transformative,” Perry wrote (5), and “despite persistent barriers” in the decades that followed the Nineteenth Amendment, women “were able to win policy victories that permanently changed the way our society works, plays, and thinks” (258).

After the Vote is both a major achievement and a path opening further study. Perry’s discussion of New York women’s first voting efforts uncovers connections between the closed primary system and debates over women’s political independence and nonpartisanship. EIP emphasized the complexity of women’s nonpartisan organizations and their crucial mobilization of women’s political activism and initiatives, often in alliances with like-minded male reformers. New questions abound: How did election laws, women’s partisan affiliations, and nonpartisan cultures influence political work in other cities and states? How might research into municipal and state political activism help us rethink our current understandings of women’s political interventions and their achievements nationally and regionally? And how might these investigations allow us to answer not only questions such as “what was women’s impact on modernizing governments?” but also “how did women’s political work reshape the commitments and contours of civil society?”

Women’s nonpartisan organizations were places where women celebrated their accomplishments and found support in difficult times. After the Vote recounts numerous occasions when women honored their achievements, though disregarded by men. These stories connect with a question in Perry’s preface: why, despite clear evidence that some women had positions of political influence in the 1920s and 1930s, has women’s political power continued to be, or to be seen as, “negligible”? A variation on this question, posed frequently by political scientists, is “why have so few women emerged as visible political leaders?” Perry’s answer is twofold: “men kept women out” and “women kept themselves out” (2).

Others in this roundtable have mentioned Rebecca Browning Rankin, director of the Municipal Reference Library of the City of New York. Rankin created New York Advancing: A Scientific Approach to Municipal Government, which promoted La Guardia’s modernization plans and aided in his 1937 reelection. Perry wrote that Rankin, like other expert and accomplished women of her day, “did not make the story about herself” (197). Consider also Henrietta Additon, who “never received credit for her contributions to crime prevention … including her invention of the Police Athletic League.” When Additon’s male colleagues wrote their memoirs, they “erased” her from the history (142–43). Many men (though not all) resented these political women, dismissed them as “curiosities” (21), or regarded their bids for offices as “quixotic” (6). The women, on the other hand, adhered “to traditional norms of appropriate behavior for women with political interests” and did not lay claim to their work (3). They disappeared from history. Yet because their work changed public life, we need to recover women’s inclusion in public life to understand better the ability of our political institutions to incorporate new voices.

After the Vote looks closely at the ways that women negotiated partisan political power at various points in time. One point, signifying the early days of their transformation from second-class citizens to voters, is the 1921 all-woman town hall debate between Republican Rosalie Loew Whitney and Democrat Anna Moscowitz Kross. The debate “gave the press a field day” (55), demonstrating that “women could wield political arguments as well (or as poorly) as men,” and, as one college-trained woman put it, felt “as good as a theatre” (56) (fig. 4).

Figure 4. Evening World (New York), October 28, 1921. Cartoonist Ferdinand G. Long’s depiction of the city’s first all-female partisan political debate, prompted by the 1921 city election, the first mayoral contest in which women could vote. The cartoon assumed participations were well-known to Evening World readers.

The debate also showed that women’s public activism before 1920 prepared many women well for partisan politics after 1920. Both Whitney and Kross were graduates of New York University Law School. Both were active suffragists. Both were rising members of their parties. Whitney was a delegate at Republican state conventions and gave speeches on behalf of Republican candidates. Kross’s work running Tammany’s Women Speakers Bureau earned her a position as assistant corporation counsel, a first for a woman in the city, and later a seat on the bench. In a later recollection, Kross downplayed the qualifications she brought to her positions and said she was “appointed in the ordinary run of the mill way—I knew the right politicians at the right time” (145).

Perry opened up the subject of political patronage, showing how women and men negotiated power and patronage differently. Why did women sometimes deny their interest in party and coalition efforts? Because patronage was often connected to corruption in New York City in the 1920s, that subject became an important part of Perry’s narrative of women’s influence and advancement. This significant thread in her book moves into the Seabury investigations into corruption in the city’s courts and police force. By 1932, those investigations “deeply wounded” the “proverbial phoenix” of the Tammany machine and brought to power the reform administration of Fiorello La Guardia (125).

Many “historians, political scientists, politicians, journalists, and novelists” have analyzed the Seabury investigations into city corruption, EIP wrote, but because no one has examined this history “from the perspective of the city’s women voters” (99), they have missed the fact that women pushed for the initial investigations, campaigned for their expansion, and helped bring about “permanent legal and political change” in the city (114). After the Seabury investigations, according to Anna Moscowitz Kross, “women lawyers were no longer curiosities” and women became judges “not merely by the sufferance of men, but because of the vote of both men and women” (155). For Rosalie Whitney, women’s leadership in the investigations led to large numbers of women appointed to positions in the La Guardia administration, and “the opportunity to improve municipal government” (185). Perry showed, as historians of women often do, that by refocusing our historical lens, by tracing people and activities that have traditionally been marginalized, even through their own erasure, we can ask new questions and find new answers.

And yet, as Perry noted, while the women in the La Guardia administration were encouraged by their unprecedented numbers, they could not ignore that the “top posts all went to men” (185). This brings us to After the Vote’s appendix. On the book’s dustjacket (and reprinted inside) is a photograph of a dinner held by the “Women of the La Guardia Administration, Hotel Brevoort, Dec. 6, 1937,” given in honor of La Guardia’s reelection (fig. 5). The appendix reprints the witty play that these women presented at that dinner. The play revolves around women’s “fantasied empowerment” during a day when the mayor and his commissioners are absent from work (176). With the men gone, they were able to realize the “feminist and social justice ideals” they had been advocating since the suffrage era—“an end to sex discrimination, an expansion of measures to benefit human welfare, and the achievement of pay equity and more career opportunities for women” (176). They were also well on their way to achieving La Guardia’s “modernizing agendas” and, in the process, proving that they can do the work “as well as, if not better than, the men” appointed by La Guardia (176). Colleagues interested in teaching students about how progressivism continues into the 1930s take note: the photograph and the play could work as a brilliant teaching tool for introducing students to the concept of the “Long Progressive Era.”

Figure 5. Reception for the Women of the La Guardia Administration, Hotel Brevoort, Manhattan, December 6, 1937. LaGuardia Photograph Collection, LaGuardia and Wagner Archives, LaGuardia Community College/City University of New York.

One final point, recalling that moment in the 2012 presidential debate between Barack Obama and Mitt Romney when Romney responded to a question about gender pay equity by saying: “I went to a number of women’s groups and said, ‘Can you help us find folks?’ And they brought us whole binders full of women.” I thought of Romney’s comment when reading Perry’s assessment of what happened in the aftermath of Jean Norris’s removal from office in 1931 during the Seabury investigations. Norris had been appointed as New York’s first woman magistrate in 1919, having won support from the city’s new women voters and from Tammany Hall. She saw her success as an “entering wedge” (106) for women seeking judicial appointments, and shared the city’s progressive community’s commitment to women’s political equality and feminist reforms. After the Seabury investigations raised questions about her handling of cases and other ethical issues, Norris lost her position (as did three male magistrates, who resigned “claiming illness”) (119). In the wake of Norris’s removal, progressive women presented the mayor with the names of women who could take up her seat. They recommended more than 190 “qualified and distinguished members of the county bar association” to Mayor Walker (122). More than twenty women openly competed for the position. In the end, the mayor chose to appoint a “highly qualified” man (122). The women took notice. And they populated La Guardia’s administration in unprecedented numbers.

Liette Gidlow: Reply to Melanie Gustafson

Melanie’s analysis here thoughtfully considers similarities, differences, connections, and tensions between two paths for women’s political advancement after women won the vote. Partisan women such as Anna Moscowitz Kross accepted political appointments and ran for elected office. Nonpartisan women such as Pearl Bernstein typically gained experience in reform organizations before moving into apolitical jobs in city administration. Inside or outside of parties, over the course of their careers, these women engineered major improvements in the city’s criminal justice system, schools and universities, and more. But though many such women tallied a long list of accomplishments, few emerged in the first decades after the vote as “visible political leaders.”

As Melanie indicates, Perry suggested two explanations for this invisibility: “men kept women out” of the spotlight, and “women kept themselves out” (2). But perhaps Perry’s research evinces a third explanation as well: erasure. Even when women did occupy important positions and accomplish valuable work, their achievements were frequently downplayed, appropriated, or otherwise obscured—say, shelved away in some binder.

To scale up this argument: perhaps the Nineteenth Amendment itself has been the victim of erasure. Even before the first few electoral cycles after ratification had been completed, politicians and the press dismissed women voters as frivolous and unengaged and called woman suffrage inconsequential. When Perry opened up her “binders full of women,” however, she documented something very different—a rich world of serious, expert, deeply engaged, and accomplished political women. After the Vote thus performs an essential act of recovery by surfacing a forgotten moment when activist women succeeded in undermining patriarchy. When we as readers and writers engage the book, we participate in that recovery work, and we too open up moments of political possibility.

Kim Cary Warren

There is a great deal to be said for role model influence. I thought you [Judge Jane Bolin] would like to know that you provided a role model for me at the time when there were very few, if any, black women in the law. I also recall hearing nothing but praise with respect to your legal ability when I first came to New York in 1941. When I thereafter met you, I then knew how a lady judge should deport herself. I want to thank you for that.

— Constance Baker Motley, first African American federal judgeFootnote 15

I am struck by the significance of honoring a scholar’s work through this roundtable during a time when so many communities around the world are faced with the hardest medical, economic, and discriminatory challenges of a generation. With countless groups facing so many layers of overlapping crises, those of us who have chosen to uncover and amplify histories of disenfranchised or disregarded people have had daily reminders that maladies hit different groups in disproportionate ways. Crises do not necessarily cause inequality, but they certainly amplify existing inequalities. In the same way that we cannot use old medical methods to dissipate the strain of this virus and its variants, or outdated approaches to end systemic racism, we also cannot use worn-out historical methods if we want to tell a more complete story about the past. New methods and questions will sustain our lives and our histories. That is one of the first important lessons that Elisabeth Perry’s After the Vote teaches us.

Although EIP’s death preceded the global disruptions in the year 2020, After the Vote reflects so many of the new strategies for survival that have become vividly apparent during this time of worldwide heightened tensions. With a focus on women and their various methods to enfranchise themselves and empower their communities in New York City, After the Vote reminds us of the importance of giving voice to those who have been ignored, silenced, or dismissed—specifically because they were women. The book also demonstrates the many ways that women saw their political work as an extension of their voluntary roles and their professional jobs, as well as any official appointments or elections they could win.

Giving voice to ordinary individuals and broadening definitions of political work is particularly important in telling the stories of Black women in New York after 1920—partly because very few Black women ran and succeeded in their bids for office in New York in the 1920s and 1930s (63). Actually, Perry pointed out, not that many white women won elected seats either. More significantly, however, Black women built political influence through their organizing, campaigning, and other political involvement. Some also saw their work—the paid labor that they performed to economically sustain their families—as a path toward enfranchisement. Although their efforts did not lead to a surge in the number of Black women in elected positions, they did help them utilize the legal rights that their communities had previously acquired through the Fourteenth, Fifteenth, and Nineteenth Amendments.

African American women are not the focal point of Elisabeth Perry’s research, but in a book that deliberately aims to include women of different racial and ethnic backgrounds, they are integral to the history of women’s political activism. As Annelise Orleck reminds us below, Jewish women’s social justice activism had an important and lasting impact on reform politics in New York. So, too, did Black women’s activism, as shown through Perry’s attention to the diversity of women’s experiences throughout the book. Examples about African American women make us think more deeply about how even though women gained rights in the 1910s and 1920s—most notably the vote—they did not necessarily have a guaranteed way to exercise those rights or the freedoms that came with the forms of citizenship that Mason Williams describes in his essay.

In order to understand which legal rights have been extended to specific groups of citizens and how those rights could or could not be utilized, Black women are central to the story. Perry shows that the increasing numbers of African Americans who occupied New York City neighborhoods during the decades before and after 1920 were as concerned about their rights as white women were. The book tells us early on that Black women historically prioritized over woman suffrage an end to lynching and racial discrimination in employment, but in the late 1880s, Black women in New York City also organized for the vote (22). This helps us see that Black women had long seen their political enfranchisement as a mechanism to help reduce racial disparity and violence in their communities. The evidence is in the founding of Black women’s clubs, including the National Association of Colored Women (NACW) in 1896, and their deep dive into educational improvement efforts.

Throughout the book, EIP focuses on women’s local efforts, regardless of their ethnic or racial backgrounds. This focus on local affiliates rather than national organizations is particularly useful in revealing how Black women developed changemaking strategies in the early twentieth century. They gathered signatures, campaigned for candidates, set up assistance for newcomers to the city, and occasionally ran for school board—just as white women did. However, they recognized that their efforts were part of a broad agenda to gain full citizenship rights that had otherwise been denied to them because of their race and their sex. Voting was important to Black women.

While After the Vote helps us understand that Black women “would be in the suffrage fight to stay” (31), the book also paints a complicated picture of the relationship between white suffrage leaders and Black suffragists, the latter of whose concerns always included race as well as sex discrimination. This part of women’s history is important to highlight, even if it might be unsettling to learn more about conflict than unity among women New Yorkers. When historians like Elisabeth Israels Perry guide us into a specific and localized story rather than a general one, we understand so much better how women with intersectional identities could not separate their sex and race in their individual and group political actions. EIP helped us understand that discrimination presented a complicated mix of challenges, requiring Black women to sometimes work very closely with white women and sometimes very separately from them.

Perry’s biographical methods highlight how race complicated women’s experiences. She brings us the voice of Black Harlem businesswoman Mabelle McAdoo, who explained the vital importance of registering to vote because “as a woman—and as a colored woman, I felt that I would not only be doing myself an injustice by neglecting to vote, but that I would be doing my race a wrong” (61). After the Vote also explains that Black women’s experience of discrimination and their fight for enfranchisement occurred in a different social context from the experiences of white women. Some colleges, including Vassar, did not accept Black students. Many Black women who did gain admission to law schools could not find jobs as attorneys. Some African American women felt compelled to support white women candidates instead of running for office themselves as a way of increasing the odds for female representation. Others, like the nation’s first African American female judge, Jane Bolin, might have found great professional achievement in becoming trailblazers but were socially isolated in their college or law school classes, and then in their professions. The photograph of Judge Bolin taking her oath of office with her husband Ralph Mizelle by her side and with Fiorello La Guardia reading the oath, was taken on the same day that Mayor La Guardia summoned her to his office and announced, “I’m going to make you a judge on the Court of Domestic Relations” (202). Through such examples, After the Vote helps us to wrestle with discrimination in the difficult ways that Black women did (fig. 6).

Figure 6. Jane Bolin, African American judge, being sworn in by New York City Mayor Fiorello La Guardia, July 1939. New York Daily News via Getty Images.

If one of the common themes among women in After the Vote is their tireless efforts to expand political rights for women, Black women are, again, important to the story. For example, Perry noted that Sarah J. Smith Tompkins Garnet founded an Equal Suffrage League, but it is her position as the first African American female school principal in the New York City public school system that helps us understand that Garnet promoted Black political advancement through professional and organizational angles (22). Perry viewed such women, including Maria Lawton, as “indefatigable” because they entrenched themselves in the world of politics by working registration campaigns, collecting signatures, holding bridge parties, calling on voters in-person and on the phone, and hosting candidate appearances on behalf of Fiorello La Guardia’s and others’ candidacies (183). La Guardia may have seen this work in support of his specific campaign, but Black women saw these efforts as a way to expand their political work and their legal rights.

What we learn from After the Vote is that if we continue to look in the old, traditionally defined political places for Black women, we will not likely find them. But if we continue to embrace Elisabeth Perry’s historical priorities that center individual voices, local communities, and community work as political action, we will not only find African American women but also understand their sustained efforts to utilize their rights across generations.

Annelise Orleck: Reply to Kim Warren

Kim Warren’s essay begins with an eloquent reminder that crises have disproportionate impacts on the poor and disfranchised. It poignantly reflects on the horrors of 2020 to remind us that crises do not create inequalities, but they certainly amplify them. Summoning the urgency of our current crisis, Warren rightly applauds Perry’s deployment of new historical questions about women’s politics—after the vote—to reshape our understanding of New York City history.

There was not necessarily unity among women in the history that Perry uncovered, Warren notes. The story of Black women New Yorkers and their contribution to city politics remains a history of interaction with white women and Black men but also one of isolation and particular resourcefulness. Black women’s presence in New York increased in the years after women gained the right to vote, as waves of migration from the Southeast arrived. Perry might also have noted waves from the Caribbean, which began landing on New York shores during that very era in which After the Vote is set—and that profoundly impacted the city’s political futures.

Warren points out that the content of Black women’s suffrage and post-suffrage activism, and the substance of their work in the women’s organizations that play such a central role in EIP’s account, focused not just on building political careers but on using the vote to address racial injustices. Often, Black women’s entry into New York City politics came through their fights to bring municipal services to their communities, which were, well into and after the La Guardia era, too often ignored by the city that they had helped to build and run.

Conflicts, Warren writes, played as crucial a role in shaping Black women’s politics in New York as convergences. It is vital to an accurate historical understanding, even if it disrupts our notions of rosy suffrage movement sisterhood, to record these conflicts as well as convergences among women activists—over race, religion, and class.

As Warren’s essay argues, as Perry’s groundbreaking book demonstrated, Black women’s political culture in New York City after the vote had roots in the pre-suffrage era—in communal/racial aspirations and in local politics. As with Jewish women activists, pre-suffrage African American political tactics and cultures, along with interracial conflicts as well as intraracial conflicts over gender, continued to shape New York City politics long after the vote.

Reading Warren’s gloss on the work of Black women political activists as portrayed by EIP, I could not help but think of Shirley Chisholm—who appears both in Perry’s book and in the work of Brooklyn historians Barbara Winslow and Brian Purnell. Chisholm arose from a rich Afro-Caribbean women’s politics that would prove absolutely core to the emergence of a Brooklyn Black political class. Warren comments here on the neighborhood feel of so much of Black women’s politics in New York City. I think of Purnell’s analysis of how galvanizing an issue the lack of garbage collection was for Black women activists in Brooklyn’s civil rights movement. How tied that was to racial segregation in the city. How Black women activists did actually come in to clean up. How city politics is about things like garbage and potholes and schools and housing as often as it is about power and money.Footnote 16

Warren’s essay evokes the insightful exposition in her 2010 book, The Quest for Citizenship, of campaigns by African American and Native American educators in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries that rejected assimilation to whiteness as the ultimate goal of citizenship.Footnote 17 Rather, as Warren does here, they centered and honored indigenous and community cultures and traditions. That kind of education became the foundation in the twentieth century for alternative multicultural framings of American citizenship no longer deformed by monolithic whiteness. Pluralistic political visions, these educators taught, were the real strength of American democratic citizenship. As Warren suggests here, it is such complex concepts of citizenship in conflict that have long been the core of what makes New York City what it is—a powerfully human, messy, conflictual, frustrating (and often inspiring) attempt to make grassroots urban democracy real.

Annelise Orleck

Growing pains continue. Still women who persist might take some lessons, if not inspiration, from the example of the New York City women of the early postsuffrage era.

— Elisabeth Israels PerryFootnote 18

Elisabeth Israels Perry’s After the Vote examines the way that politics in the nation’s largest city were shaped by women’s activism leading up to and following New York women winning the right to vote in 1917. The book argues for and illustrates the existence of a “Long Progressive Era” that extended into the 1930s and 1940s and cast sparks that helped drive the upheavals of the 1960s and 1970s—a significant rethinking of the currents of twentieth-century politics. And it does so with a light use of prosopography (collective biography), tracing the lives of several generations of women’s activist networks, detailing ways that intergenerational teaching, mentoring, and political torch-passing created continuities of ideology and policy goals that belie neat historical periodizations. The Progressive Era, the Roaring Twenties, the New Deal era, World War II, and the turbulent 1960s become linked in Perry’s telling—as successive moments in individual and organizational lifespans.

In New York City, After the Vote shows in fine detail, individual women reformers and the organizations they created—the Women’s City Club, the League of Women Voters, the Women’s Trade Union League, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), the National Association of Colored Women, and more—lived through all of these eras and in many ways unified them. After reading Perry, one can clearly discern the impact of a “Long Progressive Era” on New York politics but also—looking backward as well as forward—of a long New Deal era, a long World War II era, and even a 1960s and 1970s women’s movement that springs from roots that predate the Nineteenth Amendment. Given the city’s outsize influence on national culture and politics, the trends that Perry described in a local study also bear on the larger history of the United States. This is especially true for the transformative years when New Yorkers Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt brought policies first experimented on in New York City and state—and the networks of women reformers with whom they had worked on those issues—to the national stage to shape federal policy.

Where do Jewish women fit into all of this? Many Jewish women’s lives and careers are examined in After the Vote. Some play significant roles while others make only cameo appearances. (That is the style and structure of Perry’s volume and is equally true of every kind of woman who appears there.) Most of the Jewish women whom Perry touched on in her study were born of and shaped by the deep, immigrant Jewish cultures of social justice and subsistence activism that permeated early twentieth-century New York. But, though Perry identified them as Jews—descendants of late nineteenth-century immigrants from Russia, Poland, and Belarus, or from earlier waves of central European or German immigration—she does not use their stories to make explicit an argument that is implicit in her narrative: that Jewish women’s social justice activism of the pre-suffrage era had a lasting, multigenerational impact on reform politics in the city. In particular, Perry showed how those currents helped drive the remarkable career of Fiorello La Guardia and, as well, the work of successive generations of Jewish women activists whose careers in New York City politics the book traces. In addition to passing mentions of various officials, Perry discussed noted Jewish women activists from her grandmother—political kingmaker Belle Moskowitz—to Polish cap maker and Women’s Trade Union League officer Rose Schneiderman (born in the 1880s), and Anna Rosenberg, who, like Schneiderman, was a National Recovery Administration labor official and close confidante of FDR. Rosenberg was also, Perry showed, a guiding force behind the framing of the post–World War II GI Bill.

After the Vote argues that these earlier generations laid the groundwork for a powerful efflorescence of Jewish women’s activism in New York in the 1960s and 1970s, many of these women shaping and emerging from the women’s movements of earlier eras. In her conclusion, Perry traced a direct line from the women who were active in government after the vote, through the 1950s when New York state had the highest number of women attorneys serving in public posts, into the 1970s where she assessed the impact of women’s activism in the post-suffrage era on future Supreme Court Justice and twenty-first-century feminist icon Ruth Bader Ginsburg; Bella Abzug, the first Jewish woman elected to Congress; prosecutor and Congresswoman Elizabeth Holtzman, who would make a national name for herself during the Watergate hearings; and Ruth Messinger, New York City Council president and later head of American Jewish World Service.

It is not surprising that Perry did not comment on their Jewishness except to note it, for this is a book drawn on organizational records, and one that in many ways tells the stories of women’s political impact on New York City through the organizations they created. Perry studied lives and individual careers as well but did not examine the role played by religious cultures in shaping any woman’s politics. The index has no entries for the words Jewish, Catholic, or any Protestant denomination. This is a lapse that later scholars will perhaps address, since religious networks and ideologies were as important to women’s political rise in New York City (and elsewhere) as those forged in the social/political associations that women formed. Indeed, one of the central arguments in the book is that, while women played a fundamental role in shaping the reformist politics of New York City—in every area from education to prisons to labor to budget—women struggled to win elective office and even to be appointed to the top jobs in government agencies. Rather, Perry argued, they kind of ran things under La Guardia and under Governor Herbert Lehman while serving in secondary posts—assistant commissioner, deputy manager, etc. That women were relegated to “behind the scenes” functional power while, more often than not, failing to win electoral races may be seen, at least in part, as a result of the powerful political influence of New York’s male religious leaders—archbishops, rabbis, Protestant ministers—who established a political culture that was (and to some extent still is) fundamentally conservative on matters of gender.

That this was true only makes Perry’s book all the more important, a groundbreaking reminder of how many spheres women influenced (or outright ran) in the twentieth-century history of New York City and New York state. And it also highlights how difficult it has been, up to the time Perry released After the Vote, for us to see the roles that women played, precisely because the political culture of those famously “progressive” jurisdictions was so masculinist and so hidebound on matters of gender and race. (Witness the 2021 scandal that has forever tarnished and may end the political career of New York’s second Governor Cuomo, and before that, the sexual procurement and sexual violence scandals that brought down another twenty-first-century New York governor, Eliot Spitzer, and an attorney general, Eric Schneiderman.)

Back to the twentieth century: Perry’s conclusions are necessarily both expansive and narrow, as was, she argued, women’s political influence in “La Guardia’s New York” and since the era of the Little Flower.Footnote 19 Out of the social justice culture of Jewish immigrant women’s New York, and the multiethnic but heavily Jewish (and large majority female) garment union movement, came the foundations for old age and unemployment insurance, workmen’s compensation and the GI Bill, and liberal as well as radical feminism in the 1960s and 70s. Out of that world came Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Bernie Sanders. At the same time, Perry looked decades beyond women’s attainment of the vote to illuminate how difficult it still was (and is) for women to win political power outright. After the Vote describes electoral campaigns run well into the twentieth century when women still advertised themselves as the “cleaning woman”—ready and willing to clean up the kind of machine politics that has not yet died out. There has still not been a woman elected mayor of New York, nor governor of New York state. And yet, as Perry’s prodigious research makes clear, women have actually been running both in some very real ways for a very long time—in fact, since right after the vote.

Mason Williams: Reply to Annelise Orleck