Introduction

As discussed previously in Nazir Can’s article in this issue, Lusophone African literature sets itself apart from African literary traditions in other languages. In line with that observation, but focusing now on circulation and reception rather than production, this article aims to highlight a further dimension of Lusophone singularity. In this regard we should note, first, that it is not a former colonial metropolis (Portugal), but a former colony (Brazil) that has become the main legitimizing center of Lusophone African literatures. Secondly, moving beyond the Lusophone circle, Brazil is the country that produces the largest number of studies on African literature written in other languages.

We start, therefore, from the hypothesis that Brazil has now established a position as one of the main world centers of African literature. To validate this hypothesis, we will first show how the work of Alain Mabanckou, a Congolese French-speaking writer, penetrates the literary market and the Brazilian academy. After contextualizing the historical institutional dependence that characterizes French-speaking African literature in relation to the old “center” (Paris) and placing Mabanckou in this dynamic, we will see how his work arrived in Brazil, the growing interest that it has awakened, and the type of studies conducted there. In the second part of the article, we will offer some data that confirm our broader hypothesis about Brazil as a republic of African letters: due to the flow of translations and academic studies on works from different linguistic contexts, Brazil helps to unsettle the linguistic self-centeredness that characterizes African literary studies (“Lusophone,” “Francophone,” “Hispanophone,” “Anglophone,” etc.) and to reduce the distances between “center” and “periphery” or between “North” and “South” that tend to shape the world literary game.

Alain Mabanckou, from Pointe-Noire to the World

Known for his approaches that depict the experience of contemporary Africa and the African diaspora in Europe, especially in France, the Congolese author Alain Mabanckou is among the most prolific contemporary African writers. In addition to articles, he has published dozens of books, including novels, poems, books for children and young adults, and nonfiction. As the first African-born novelist to occupy a position at the Collège de France since its creation in 1530, the writer taught the discipline of artistic creation, between 2015 and 2016, with the course entitled Lettres noires: des tenèbres à la lumière,Footnote 1 transformed into a book. In his inaugural class, he claimed “to belong to a generation that questions itself, because despite being the heir of the colonial division, it brings the marks of a frontal opposition of cultures whose glass shards dot the spaces between words, because this past continues to boil.”Footnote 2

For N’Goran,Footnote 3 French-speaking African literature, before establishing itself within the field, was first subjected to a series of successive empowerments. Since its emergence, it has taken shape against an otherness, that is, to place itself as an instance of speech that can favor a self-designation through an invention of the “Other.” However, this empowerment is slower regarding institutional relationships. Recent history shows us that most renowned names in French-speaking African literature are initially recognized in Paris. At the same time, most French-speaking authors do not live on the African continent.Footnote 4 The articulation that French-speaking authors make between a literary experience designed for the South (Africa) and a vital experience located in the North (Europe or the United States) should not be seen as a defect, but as a productive problem for comparative analysis, as it puts into question situations less explored in other literary spaces. The most immediate effect of this condition, in the lives of writers, is the inevitable negotiation with the market and Western readers.Footnote 5

According to Casanova, the consecration of a Francophone African writer in the “World Republic of Letters” necessarily depends on two main factors.Footnote 6 The first is associated with the publication of these works by French publishers in France, more specifically Paris, established itself in a lasting manner as the capital of that republic, becoming a “universal homeland,” a transnational (and unequal) space whose only imperatives are those of art and literature.Footnote 7 The second factor, equally important and paradoxical, concerns the relations that emerge from French colonization in Africa. The writers of African countries that formerly were French or Belgian colonies find in Paris the necessary and established conditions to publish their books, as has been also demonstrated by Claire Ducournau.Footnote 8

However, currently other geographies and networks contribute to the consecration of writers such as Mabanckou, and this is where we begin to discern the emergence of Brazil as a consecrating center. The Congolese author is part of the so-called generation of migritude, a neologism coined separately by Jacques Chevrier and Shailja Patel that mixes “migration” and “Negritude,” are those African writers who have chosen, for various reasons, to migrate, study, or teach and produce their literary works outside the African continent. For Mabanckou, the spaces of belonging and the spaces of transit play different roles in his work and in his life:

Congo is the place of the umbilical cord, France the adoptive homeland of my dreams, and America a nook from which I observe the footprints of my wanderings. These three geographic spaces are so close together that I sometimes forget which continent I sleep in and in which I write my books.Footnote 9

The assertion verifies the configuration of contemporary intellectual and literary production, which transits between continents in a short period of time, even creating the illusion of overcoming the linguistic barrier. The assertion “Literature is measured, first of all, by our ability to cross our universes, to integrate other distant, diasporic Africa, without, however, exchanging our origins”Footnote 10 synthesizes the literary perspective of Alain Mabanckou.

The scope of Mabanckou’s work thus stretches across three continents: Africa, Europe, and America. Addressing issues such as colonialism, Black identity, immigration, cultural identity, and Africa’s role in the contemporary world, all this mediated by humor and irony (possibly the great trope of world postcolonial literature) and the praise of nomadism (possibly the most celebrated theme among scholars of African literature), ingredients he uses to shake essentialist discourses produced in different spaces and times, the Mabanckou’s work has been translated and read in more than twenty countries around the world,Footnote 11 including Brazil and Portugal.

Alain Mabanckou in Brazil

If we focus now on the Lusophone dimension of Mabanckou’s reception, two points are worth emphasizing. The first is that only a limited number of titles have, after all, been translated into Portuguese; the second is that almost all translations have been produced in Brazil, not Portugal.

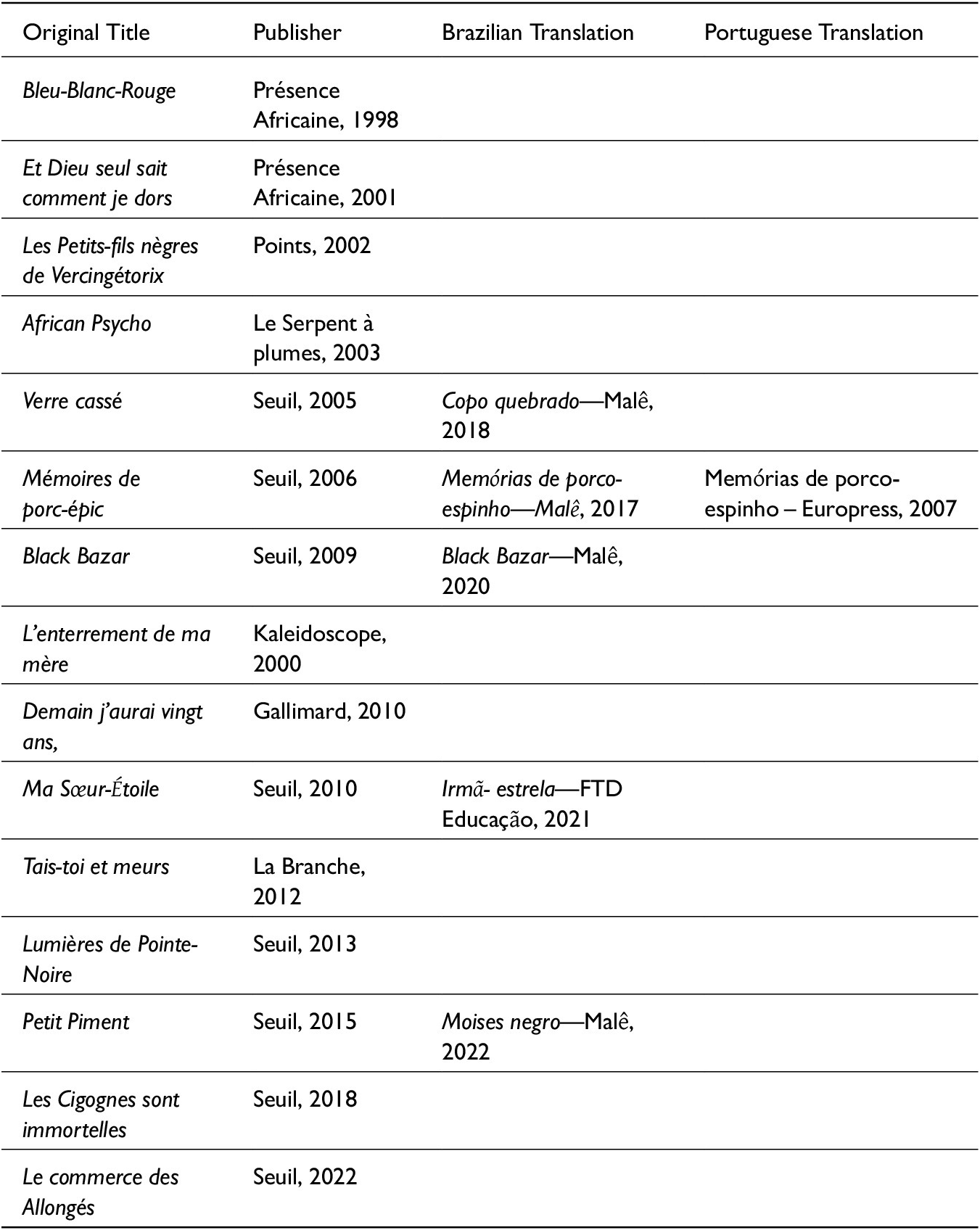

The lack of translations in Portugal, as can be seen in table 1, reflects a corresponding dearth in academic interest. In a brief survey conducted at the Scientific Archives of Open Access of Portugal (RCAAP, acronym in Portuguese), the largest platform that gathers research from Portuguese—but also European and Brazilian—universities, less than ten research articles were found that focused on French-speaking African literatures. In another search conducted on the RCAAP using the keywords “Alain Mabanckou,” only one doctoral thesis produced at the University of Madeira was found.Footnote 12 However, the theme of Leonor Martins Coelho’s research was not specifically about Alain Mabanckou. Other searches were carried out directly in the catalogs of the libraries of the universities of Porto, Coimbra, Lisbon, Nova de Lisboa, Aveiro, and Católica Portuguesa, and no thesis or dissertation produced about the author was found. Comparing Mabanckou’s reception in Brazil and Portugal, we can observe a discrepancy in the number of academic papers. Although some master’s dissertations were produced in Brazilian universities, in Portugal there is still no research om Mabanckou produced in universities.

Table 1. Novels Published by Alain Mabanckou, Translations in Brazil and Portugal and Publishers

Source: Our authorship. Data collected from the websites of the publishers Présence Africaine, Points, Le serpente à plumes, Seuil, Kaleidoscope, Gallimard, La Branche, Malê, Europress, and FTD Educação.

There are several factors that can explain the reduced circulation of Francophone African texts in Portugal: first, compared to Brazil, Portugal is a small country with few universities. African literature transits with difficulty through the universities, despite the historical contact between Portugal and Africa. Only at the University of São Paulo or the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, both in Brazil, there are as many full professors of African literature as in the entire Portuguese territory. In the small Portuguese circuit, Lusophone authors are privileged. Second, publishers in Portugal are very important for the consecration of some Portuguese-speaking African authors, as shown in the article by Marco Bucaioni in this special issue. However, this publication field is not very decentralized (Editorial Caminho occupies a large part of the editorial space dedicated to African literature). It favors a certain author profile and is therefore more restricted. Contrary to what happens in Brazil, the diversity of publishers and authors is reduced. Third, the French language has been in decline for decades in the university systems of non-French-speaking countries. The Portuguese academic space is no exception. This further reduces the likelihood for Francophone African writers to be read, studied, and translated in Portugal.

In Brazil, after Editora FTD (Sao Paulo) published Irmã-Estrela (Ma Sœur-Étoile) in 2013, Editora Malê, in Rio de Janeiro, edited some of Alain Mabanckou’s main novels: in 2017, was published as Memórias de porco-espinho (Mémoires de porc-épic, 2006); soon after, in 2018, Copo Quebrado (Verre Cassé, 2005); two years later, in 2020, Black Bazar (Black Bazar, 2009) and Moisés Negro (Petit Piment, 2015) were published. All these novels were translated by Paula Souza Dias Nogueira, who also dedicated some critical studies to the work of the Congolese author, as we will see. It is noted, on the one hand, that the temporal distance between the publication of the original and its translation in Brazil reduces over the years; on the other hand, we observe that, currently, there are more works published by Alain Mabanckou than by the Mozambican writer João Paulo Borges Coelho—who only reaches the Brazilian market in 2019, despite being one of the most studied authors in the country’s universities.Footnote 13 These data show that, although it has an impact, language does not constitute an insurmountable barrier to the consolidation of non-Lusophone African authors in Brazil.

It is important to mention that Alain Mabanckou was one of the invited authors of Flip 2018 (Paraty International Literary Festival), where he discussed his novel Mémoires de porc-épic, alongside issues such as identity, Africanity, race, and orality. This appearance boosted the sales of his works by 36 percent, confirming an old hypothesis: participation in festivals and fairs is one of the ingredients that guarantees the recognition and expansion of the writer to the public.Footnote 14 Like many African writers, Alain Mabanckou has been well received by the Brazilian public. With the translation and publication of his novels in the last six years, the tendency is for more research to emerge, as well as to increase his readership.

To confirm the growing importance of Alain Mabanckou in Brazilian academic works, according to Google Academic, the author is analyzed or mentioned seventy-five times in scholarly articles. In several of them, the novels Mémoires de porc-épic and Verre cassé are discussed directly, the others are quotations in texts whose themes are “African literatures,” “postcolonialism,” “immigration,” “identity,” and “oral tradition.” The keywords suggest that the author and his literary production are referenced to discuss issues related especially to these themes. Regarding monographic studies carried out in Brazilian universities in recent years, we can highlight three dissertations.

The first, “Espinhos da tradução: uma leitura de Mémoires de porc-épic” (“Spines of Translation: A Reading of Mémoires de porc-épic”), was produced at the University of São Paulo by Paula Souza Dias Nogueira in 2016.Footnote 15 The thesis looked at central elements of the poetics and narrative structure of the novel, its translation, as well as the author’s life and work trajectory. There is in this analysis a strong focus on orality in scholarship on African literature in Brazil. However, Mabanckou’s novel enables a deepening of theoretical-methodological studies on this topic precisely because they are set in historical and linguistic contexts that are less known to the Brazilian reader. In other words, the author contributes new perspectives in the critical debates. Paula Souza Dias Nogueira, as we saw, was responsible for the translation of the four novels published by Malê. In this case, the publisher received funding from the French embassy in Brazil, through the Publication Support Program, for the translations Mémoires de porc-épic and Black Bazar. As for the novel Petit Piment (Moisés Negro), translation and publication were possible through a partnership with TAG Livros, which is a book signature club. Only the novel Verre cassé was fully funded by the publishing house Malê.

Five years later, Kasonga Nkota completed his master’s thesis at the Federal University of Juiz de Fora. Entitled “As vozes que fazem o texto: análise da oralidade e da intertextualidade na obra Verre cassé, de Alain Mabanckou” (“The Voices that Make the Text: Analysis of Orality and Intertextuality in the Work Verre Cassé, by Alain Mabanckou”),Footnote 16 the research was published in 2021. Kasonga Nkota is a Congolese, the same origin as Alain Mabanckou, and based in Brazil. In Kasonga Nkota’s writing style, there is a certain sentimentality and a strong concern to present the Democratic Republic of Congo to the reading audience. The fact is that, among the dissertations synthesized here, he is the only one who has written an entire chapter on the history of his country. Like Paula Souza Dias Nogueira, Nkota privileged the study of orality, although he intertwined this aspect with the phenomenon of intertextuality. Mabanckou’s work, by the way, is one of the richest in terms both of its internal polyphony and it intertextual dialogue. The impact of orality must do primarily with two factors: the inscription, in African texts, of elements that also point to orally transmitted traditions that are in permanent movement, and the absence, in classical literary theory, of a reflection that situates orality as a full intertext. African literatures, in this sense, contribute also to the decolonization of Brazilian literary theory, which historically inherited European precepts.

The difference in the third large study, “Literatura e pós-colonialismo em Black Bazar e Verre Cassé, de Alain Mabanckou” (“Literature and Postcolonialism in Black Bazar and Verre Cassé, by Alain Mabanckou”), is its postcolonial approach. Although Kasonga Nkota is discussed en passant, it was Rayza Giardini Fonseca who deepened the perspective, analyzing the author’s two novels based on studies by theorists such as Homi Bhabha, Frantz Fanon, Stuart Hall, and Edward Said. Published at the Universidade Estadual Paulista “Júlio de Mesquisa Filho,” in 2022, the researcher’s proposal engages with one of the key topics in the Brazilian academy today: the condition of the Black subject in postcolonial society.

As we can see, the three studies had in common the objective of presenting Alain Mabanckou and his work to the reading public. The first two analyzed orality, and the second and third, the relations between inheritance and exclusion from the postcolonial theory. The three researchers worked with the French versions of the novels. In the cases of Paula Souza Dias Nogueira and Rayza Giardini Fonseca, contact with the French language took place in the degree course in letters with qualification in Portuguese and French. As for Kasonga Nkota, he was part of his educational training in the Democratic Republic of Congo, that is, he was literate in the French educational system and is currently a French teacher at Alliance Française in Juiz de Fora, Minas Gerais. The three surveys were conducted in universities in southeastern Brazil, where, precisely, in the 1970s, African literary studies began in Brazil, as we will see in the following.

We could assume that Mabanckou’s success in Brazil is due to two reasons: his previous consecration in Paris and the subsequent globalization of his work. In this equation, by belatedly celebrating a few years late an artist awarded in Paris, London, or New York, Brazil would only confirm his peripheral condition. But if we integrate other data into the analysis, we will see that the author’s penetration in the publishing market and the growing interest in his work in universities have to do with a dynamic that began decades ago. Observing the process, as we will do in the following, we confirm the leading role occupied by Brazil in the field of African literature.

Brazil, Republic of African Letters?

One of the main marks of the imperial structures of our times is the linguistically structured hierarchy of the field of knowledge. If the theoretical and critical contributions of other linguistic traditions are only very shyly inserted in the bibliographies of the Anglo-Saxon and Parisian axesFootnote 17—just to cite the example of the main imperial powers of the last centuries—what to say about the literary texts? In the universities and bookshops of the old empires, the concentration of studies in the African literatures that share the same languages is indisputable. Also, in Brazil the prevalence of literature in the Portuguese language is evident. Angola is the main reference for Africanist research in Brazil until the end of the twentieth century, followed by Cape Verde. The phenomenon is understandable if we consider the relationship between these countries and Brazil in the South Atlantic routes. Scholarship on Mozambique has, however, grown quickly in the twenty-first century thanks to the previous consolidation of the “Afro-Atlantic” literatures. But, contrary to what might be expected, Brazil is today the country that is most engaged with the African texts in different languages, as we will see.

Several factors put the country in a privileged position in this field: first, set up by African and Afro-descendant hands and without a colonial past in the continent, Brazil offered different artistic models to the African literary contexts; second, in one of its saddest moments, the military dictatorship (1964–1984), the literatures of the African continent played a major role in progressive fronts in the country; third, the country hosts today some of the most important Latin American universities; fourth, literary studies about Africa in Brazil preceded work in related disciplines such as history and anthropology. Moreover, these disciplines drew on the literary scholarship for their own purposes. Despite the accumulated desegregation resulting from social inequality, its peripheral language and the inequalities that affect the academic field, it is not difficult to understand that Brazil is one of the big world scenarios for the systematic studies of African literatures.

The editorial interest in these literatures dates back to the 1950s and 1960s, when some works were translated and published. But it was in the 1970s that a more dedicated focus began to emerge: first, with the emergence of the cultural and literary magazine Sul, a decisive milestone for bringing Brazilian and African intellectuals closer together, especially Portuguese-speaking ones, and secondly, with the appearance of the “Romances da África” collection, by Editora Nova Fronteira. Among the published novels, we can highlight the translations of Un fusil dans la main, un poème dans la poche (1973): by the Congolese Emmanuel Dongala, Le Soleil des indépendances (1968); by the Ivorian Ahmadou Kourouma, Le Vieux nègre et la médaille (1956;, by Cameroonian Ferdinand Oyono, The Palm-Wine Drinkard; by Nigerian Amos Tutuola, and Lemon (1969); and by Moroccan Mohammed Mrabet (originally published in Arabic).

The “African Authors” collection, hosted by the publisher Ática and coordinated by Fernando Albuquerque de Mourão, was a particularly important initiative. It is important to mention that Mourão (1934–2017) and other Brazilian scholars, professors of the Faculty of Philosophy, Letters and Human Sciences of the University of São Paulo (FFLCH-USP), had direct contact with African writers and intellectuals—Léopold Sédar Senghor (1906–2001) and Amílcar Cabral (1924–1973), for example—at congresses held in Portugal, Paris, and some African countries (Senegal and Angola, mainly). Therefore, the initiatives to discuss issues related to the African continent in Brazil are also the result of these relations. Launched in 1979, a few years after the independence of Portuguese-speaking African countries but in the midst of a military dictatorship in Brazil, the project introduced twenty-seven works by African writers from various countries to the Brazilian public. The collection comprised, in addition to works by writers from Portuguese-speaking and English-speaking countries, works by French-speaking writers, such as Aventura Ambígua (L’Aventure ambiguë)Footnote 18, by the Senegalese writer Cheikh Hamidou Kane and Climbê,Footnote 19 the Ivorian Bernard Binlin Dadié (1916–2019), the Congolese Valentin-Yves Mudimbe, the Guinean Djibril Tamsir Niane, the Senegalese Ousmane Sembène, and the Tunisian Chams Nadir (pseudonym of Mohamed Aziza), are among many French-speaking authors translated and published in this collection.

In the academic field, we can identify a first step for the expansion of these studies also in the late seventies. Thanks to the pioneer gesture of Maria Aparecida Santilli, still in the beginning of the seventies, at the University of São Paulo, and to the work of Benjamin Abdala Júnior, Rita Chaves, Simone Caputo Gomes, and Tania Macêdo, the African literatures became the center of attention of several researchers at Brazilian universities. These professors were joined by Laura Padilha, at Federal University Fluminense. In the middle of the 1990 decade, at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, after the crucial support of Jorge Fernandes da Silveira, the African literatures area was inaugurated by Carmen Tindó Ribeiro Secco. Also in the same period, Maria Nazareth Soares Fonseca started the African journey in Minas Gerais. Aware of the challenging task of making this literature available while at the same time teaching and researching it, these scholars formulated the first critical texts and equipped the universities’ libraries with books acquired during their travels to Africa.

After a struggle that had been initiated in the previous decades by the antiracist activists of the Black movement,Footnote 20 President Luís Inácio Lula da Silva issued, in 2003 and 2007, respectively, the laws 10.639/03 and 11.645/08, which stipulated the inclusion in all levels of education a syllabus dealing with African, Afro-Brazilian, and indigenous history and cultures. In France, in 2005, with article 4 of the law on returnees, Sarkozy took education in the opposite direction: “The school programs should recognize above all the positive role of the French presence in the Outremer, particularly in North Africa.”Footnote 21 In 2007, in Portugal, the dictator António de Oliveira Salazar won a popular poll to elect the “best Portuguese in history.” The election was promoted by the public Portuguese TV channel RTP. Thereby, in stark contrast to what was proposed in some of the old imperial metropolises, the Brazilian law favored the amplification and the decentralization of these studies. The effects are still felt today.Footnote 22

In his postdoctoral research, recently concluded at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro under our supervision, Ricardo Pedrosa Alves examines the presence of African literatures—irrespective of the language—in the Brazilian post-graduation. In his final report, not published yet, the researcher raises a set of claims that emphasize the size of the difference: in the Brazilian universities, more than seventy-four African authors (mostly in English, French. and Spanish), distributed across nineteen countries, were already the subject of dissertations for masters or PhDs. The researcher presents information that gives the dimension of difference: between 1979 and 2018, in Brazilian universities, 848 (84.8 percent in total) works on African literature originally written in Portuguese were the subject of masters’ dissertations and doctoral theses, in contrast to 152 (15.2 percent) of literatures originally published in other languages. It should also be noted that comparative studies (which analyzed Lusophone authors and authors from other linguistic traditions) are, in these statistics, placed in the “Lusophone” field.Footnote 23 We could interpret these numbers as the confirmation of an inequality due to the quantitative difference between Portuguese language writers analyzed and authors of other linguistic traditions. However, we believe that this data should be read from another perspective. We only need to observe comparatively what happens in the European, Asian, US, and even African universities. That is, if we compare with other critical traditions, we will not find in the academy of the United States, England, Portugal, or France, for example, a similar volume (15.2 percent) of theses or dissertations carried out on authors published in other languages.

At the same time, theses and dissertations are just one element of a broader picture. If we add to this number articles, book chapters, reviews, and collective volumes,Footnote 24 data not treated in the study by Ricardo Pedrosa Alves, but which make up the most significant sample of academic reception, the importance of the Brazilian academy to the critical reception of African literature produced in other languages is confirmed. With regard to Mabanckou, as we saw, there are several articles, papers, or book chapters that analyze his work in an exclusive or comparative way. In this sense, understanding the reception and dynamics of research productions aimed at African writers from French-speaking countries requires a cautious approach. The amplification of the corpora in Brazilian academia has been possible because the study of African literatures as well as the development of other subjects such as history and anthropology has reached a consolidation phase. The translation and the circulation of these works signal that the interest goes beyond the university walls.

For all this, and because of a long and tragic history that Africans and Afro-descendants to some extent share, it is not surprising that some French-speaking authors identify Brazilian readers as the primary interlocutors for their works. This is what the Brazilian scholar Mirella do Carmo Botaro shows us, in a doctoral thesis, recently defended at the Sorbonne University, in Paris, which dealt precisely with the relations between the works of Mabanckou and Tierno Monénembo, and the Brazilian market:

This political dimension that the literatures of black Africa acquire in post-slavery Brazil must be taken into account in our discussion, because it helps to envisage a certain “horizon of expectation” … Not by chance, African writers who were interested in these interlocutions come from the territories that once housed slave ports, to the west of the continent. This is the case of Togolese Kangni Alem with his novels Slaves (2009) and Children of Brazil (2017); Beninese Florent Couao-Zotti, with Ghosts of Brazil (2006) and, finally, Guinean Tierno Monénembo with Pelourinho (1995).Footnote 25

Thereby, Brazil remains “excessive” (desmedida), to use Ruy Duarte de Carvalho’s term (2010). It seems to be the “last producer of the unprecedented” as the watchful eye of the Angolan writer perceived in the book dedicated to the country.Footnote 26 Under both definitions, it is possible to recognize the two ends that coexist in the biggest country of South America. The resistance from the Brazilian elites and media to integrate the idea of Africa in day-to-day life is well known. But at the same, in the opposite direction, we find Brazil to be one of the main disseminators of texts from and knowledge about Africa. It has, through a process that has been ongoing for decades, become a vibrant environment for the study and propagation of African literature.

Conclusion

The openness to the world is one of the main characteristics of the African literary texts. But what is the openness of the world to these same texts? We have in this article attempted to sketch out some answers to that question. A set of factors places Brazil, a former colony, as the great receiver and producer of contents about the African literatures of the Portuguese language. At the same time, as we have seen in more detail, Brazil has become the country that has produced the largest amount of studies of works from different linguistic traditions of African literature. Thus, after the consolidation of Lusophone literary studies in the main universities, the creation of new universities in peripheral regions (such as the Northeast), the emergence of laws that favor contact with African literary production at all levels of education, the emergence of public debate about the historical exclusion of Afro-diasporic populations, and the emergence of publishers interested in literary goods from other linguistic latitudes, Brazil has today achieved the position of one of the world capitals of African letters.

The volume of academic studies conducted at Brazilian universities on authors who originally write in other languages hardly finds a parallel in other countries. The growth of critical mass is not, however, without irregularities or contradictions. This is inevitable in a country of continental dimensions and characterized by inequality. This same unevenness is evident, naturally, in the academic field: the universities of the Brazilian Southeast (São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, and Minas Gerais), precisely where African literary studies began, are endowed with much more favorable conditions than the universities from the North and Northeast, which only recently inaugurated the road toward African letters. At the same time, as happens all over the world, the African continent continues to be a paradoxical object of fascination and abjection. Combating the heritage that places Africa in the field of essences is a permanent challenge for Brazilian universities. As an example, on the one hand, we observe how some scholars have been striving for decades to consolidate the area amid the conservatism that characterizes the local university institution and many of its peers. On the other hand, in similar circumstances, many researchers, especially in the last twenty years, integrate African literature into a broader framework of productions whose primary function would be the fight against racial exclusion. Moved by good intentions, because linked to a legitimate and necessary cause that denounces the forms of discrimination that populations of African origin in Brazil have been victims of throughout history, this type of approach contains risks. And this is because the problem of exclusion of Afro-diasporic communities in the world is different from that which affects, today, the populations of African countries, holders of an extraordinary plurality of positions and social capital. The already classic essays on the formation of the Brazilian population, if contrasted with the African/Africanist scientific production that observes its own paradoxes and conquests,Footnote 27 would demonstrate that the difference in historical, political, social, and identity itineraries is one of the marks of contemporaneity that cannot be disregarded. The recognition of socio-cultural differences between Brazil and Africa in this long historical process of contacts is, therefore, fundamental. The other major challenge involves the production of knowledge in a worldwide academic context that invites reproduction. The reiteration of study themes, especially in recent years, contrasts with the multiplicity of works that have been called for debate. Linked to the aforementioned, a complementary challenge arises: the combination of attention to the literary text, work in the historical archive and field research—which is less common among the new generations of scholars—will certainly contribute to bringing the qualitative levels of academic works closer to quantitative records. To face all these challenges, the contribution of voices from other linguistic traditions, such as that of Alain Mabanckou, whose Brazilian trajectory we have attempted to synthesize here, will certainly be decisive.

Indeed, all these challenges are somewhat shared by the world academic community. To a greater or lesser extent, they result more from the dynamics of our time than from the characteristics of a given space. Therefore, Brazil is in a privileged position to solve them. After all, as we have seen, it is the country that has exercised the greatest hospitality to the voice of the African “Other.”

Competing interest

None.