One of the most controversial campaigns following the attacks of 9/11 has been the global war on terrorist finance. Initiated under President George W. Bush, US authorities established a wide range of legal mechanisms allegedly targeting the financial sources of supposed militant organizations. The USA Patriot Act1 and the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA)2 provided Federal officials with the authority to freeze assets of entities and individuals identified as financing terrorist organizations. Launched on October 25, 2001, Operation Green Quest froze more than $34 million in global assets linked to alleged terrorist organizations and individuals. At the time about 142 nations came on board and blocked $70 million worth of assets within their borders and most continue to express open “support” for the American led effort to “choke off” terrorist funding.

This campaign has targeted Islamic welfare associations and a host of informal social institutions in the Muslim world. Included in the Treasury Department’s list of entities supporting terrorism are the largely unregulated money transfer agencies known in Somalia as sharikat hawwalat or money “transfer agencies.” In November 2001, the US government ordered the closure of the US and international offices of what was then Somalia’s largest money transfer agency, al-Barakaat, and seized all of its assets, totaling $34 million. They also closed the Somali International Relief Organization and Bank al-Taqwa in the Bahamas.3

Despite protests to the contrary from Somali nationals and United Nations (UN) officials, the US administration insisted that there was a clear connection between these Somalia-owned hawwalat and the al-Qaida network. Eventually, however, American and European officials acknowledged that evidence of al-Barakaat’s financial backing for terrorism had not materialized. In the years since, only four criminal prosecutions of al-Barakaat officials have been filed but none involved charges of aiding terrorists.4 US Embassy officials in Nairobi, who had been investigating these linkages since the terrorist bombings in Kenya and Tanzania in 1996, also stated that they “know of no evidence” that al-Qaeda is linked to militant groups in Somalia.5 Moreover, the FBI agent who led the US delegation, which raided the offices of al-Barakaat, stated that diligent investigation revealed no “smoking gun” evidence – either testimonial or documentary – showing that al-Barakaat was funding al-Qaeda or any other terrorist organization.6 In August 2006, more than five years after al-Barakaat was designated as a likely financier of terrorism, US authorities finally removed the hawwalat from its terror list.7 Nevertheless, as late as 2016, the World Bank report acknowledged, that “many banks in the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada and Australia have closed the bank accounts of Somali remittance companies purportedly due to the perceived high risks of money laundering and potential links to terrorism.”8

In its attempts to set “global standards” for preventing money laundering and counterterrorist financing regimes, US policy makers have also targeted Islamic charities and businesses as part of Operation Green Quest. In 2008, the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) warned: “[T]he misuse of nonprofit organizations for the financing terrorism … is a crucial weak point in the global struggle to stop such funding at its source.”9 The global nature of the campaign has had significant impact in Muslim countries and in Somalia in particular. One of the major problems has been that not only have governments worldwide regulated the sharikat hawwalat and Islamic charities and designated many as “financing terrorism,” states have also used the “war against terrorism” strategically with the result that the campaign has undermined the livelihoods of those most in need of social protection.10 In countries such as Egypt, Islamic “charities” do not only serve the religious obligations of Muslims, they provide essential goods and services for Islamists and non-Islamists alike.11 They have filled the social welfare gap in important ways at the very time that states have reduced their role in the provision of social welfare.12

It is important to note that there is definitely a connection between the “hidden” economy of remittance inflows and the ascendancy of Islamist groups in the labor-exporting countries of Sudan and Egypt. Since the 1970s, institutions such as the Faisal Islamic Bank, based in Saudi Arabia but with branches in many parts of the Muslim world, have been instrumental in promoting the financial profile of Islamists throughout the Islamic world. Osama bin Laden opened several accounts in these banks, including a number of Sudanese banks while he was residing in that country. Branches of the Faisal Islamic Bank, Baraka, Tadamun Islamic Bank, and the Omdurman Islamic Bank have been an important source of financing for Islamists in Sudan for four decades.13 In Egypt, Islamic Management Companies, which attracted large deposits from Egyptian workers abroad in the 1980s, helped raise the political profile of a middle-class network of moderate, albeit conservative and nonviolent, Islamic groups by funding a host of commercial enterprises and Islamic welfare associations. These developments coincided with the oil price hikes and the boom in labor migration to the Gulf. Doubtless this connection is part of the reason why US officials have focused their attention on the hawwalat system, with some analysts going so far as to refer to informal transfers as part of an “Islamic banking war.”14

However, in Somalia, the hawwalat have assumed a quite different role. My own survey research on the hawwalat in Somalia shows that, rather than facilitating the rise of an Islamist coalition encouraged by state elites during the oil boom period, as in Sudan and Egypt, remittance flows have played a large part in the civil conflict in Somalia and reinforced clan divisions rather than reinforcing Islamic ties. Indeed, the unintentional consequence of the war on terrorist finance has been to target the victims of state collapse rather than Islamist militants of the type that engage in transnational terrorism. In reality, informal banking systems (i.e., hawwalat) in Somalia that are commonly used by Somalis to send monies back home to family and kin relations operate largely on the basis of clan networks and do not promote or finance militant Islamist groups. This chapter analyzes how specific types of informal markets in foreign currency (fueled by labor remittances) influenced the development of clan conflict and helped lay the context for state disintegration in Somalia during the remittance boom.

Targeting Weak and Failed States: Blaming the Victims?

Since the 9/11 attacks a key focus of the war against terrorist finance (i.e., Operation Green Quest) appears to be societies like Somalia that have suffered state disintegration, rather than the formal financial banks and wealthy citizens in the Gulf who have a long history of supporting Islamist groups.15 As one British parliamentarian put it, “the focus of the campaign should be on states that have very little control within their borders, and where a degree of an invasive military response may be appropriate.”16 In reality, however, the wholesale closure of these informal banks proved counterproductive to the long-term US objective of putting an end to global terrorism. Indeed, rather than “interrupt[ing] the murderers’ work,”17 as George W. Bush put it at the time, shutting down money transfer agencies led to further impoverishment and possible radicalization of average Somalis who rely on these services for their daily survival.

The US campaign against the hawwalat and those who operate them proved overly broad as to defy justification. In addition to shutting down al-Barakaat, the administration froze the US assets of 189 individuals and organizations suspected of supporting terror groups.18 AT&T and British Telecom’s joint venture cut off international services to Somalia’s principal telecommunication provider, a subsidiary of al-Barakaat, after the United States claimed that it too was suspected of “financing terror.” One of the most vital communication links between Somalia and the outside world – making it possible for millions of Somalis to receive remittances from relatives’ abroad – was effectively shut down. Since al-Barakaat was also the largest telecommunications provider, its closure affected all the other hawwalat companies including Dahabshil and Amal, concentrated in northwest and northeast Somalia, respectively. Thus, in addition to exacerbating the humanitarian crisis, the closure of the hawwalat adversely affected all sectors of Somalia’s larger economy, which has been heavily dependent on the inflow of remittances for over four decades. Moreover, it is also threatening to upset the fragile state-building efforts that brought peace and stability to the northern parts of Somalia after decades of internecine clan warfare.

Following the attacks of September 11, the most troubling misconception about the hawwalat is that “such operations exist as a sideline within unrelated businesses, such as a grocery store or a jewelry store.”19 In reality, as in other labor-exporting countries, in the case of Somalia, the hawwalat are anything but a sideshow. Not only have these agencies and the cash they send secured countless livelihoods, they have played a major role in political and economic developments for decades. Labor has long been Somalia’s principal export, and remittances from Somalis working abroad are the most important source of foreign exchange. As early as 1981, national account figures showed that remittances, most of which escaped state control, equaled almost two-fifths of the country’s gross national product.20 More recent estimates of the total volume of remittances received in Somalia range from a low of $1 billion to $1.6 billion annually. In 2000, for example, more than 40 percent of households in northern Somalia relied on remittances as a supplementary source of income (see Figure 3.1). A more recent study found that remittances to families averaged US$200 per month, compared to the average annual income of US$491 per annum. In other words, the average monthly remittance transfer was more than sufficient to lift people out of poverty in the context of Somali’s economic and social crisis.21

Figure 3.1 Remittance inflows in Northern Somalia.

The benefit of these remittance flows accrues to the vast majority, albeit not all, of Somalia’s subclans. Among the Isaaq, the clan, which has historically supplied the majority of migrant workers, none of the four subclans has less than 18 percent of its households receiving remittances from abroad. Thirty one percent of the Haber Awal subclan’s families, for example, count on transfers (see Figure 3.2). Remittances are usually a supplementary source of income. Typically, in addition to receiving assistance from relatives, Somali families have more than one member involved in informal economic activities. Nevertheless, Somalis rely heavily on support from overseas relatives sent through the hawwalat system, far more than their Egyptian and Sudanese counterparts.22

Figure 3.2 Labor remittance recipients by Isaaq subclan, Northwest Somalia.

Clearly, family networks are the principal reason why Somalis have been able to secure their livelihoods under harsh economic conditions. Moreover, following the collapse of the Somali state every “family” unit has come to encompass three or more interdependent households.23 In addition to assisting poorer urban relatives, a large proportion of urban residents support rural kin on a regular basis. While only 2 to 5 percent of rural Somalis receive remittances directly from overseas, Somalia’s nomadic population still depends on these capital flows. In northern Somalia, for example, 46 percent of urban households support relations in pastoralist areas with monthly contributions in the range of $10 to $100 a month; of these 46 percent, as many as 40 percent are households which depend on remittances from relatives living abroad (see Figure 3.1). Consequently, even more than Egypt and Sudan, the link between labor migration, urban households, and the larger rural population is a crucial and distinctive element in Somalia’s economy.

Most hawwalat transfers represent meager amounts. More than 80 percent of all transfers sent through the largest three of these agencies were no more than an average of $100 a month per household. There is clearly no connection between the vast majority of these transfers and the larger funds associated with terrorist operations.

In this respect, the criminalization of these transfers following the attacks of 9/11 kept more than a billion dollars out of Somalia’s economy. Moreover, according to the UN, the closures came at a time when Somalia’s second income earner, the livestock sector, was losing an estimated $300 million to $400 million as a result of a ban by its major importer, Saudi Arabia. Coupled with intermittent droughts, the decision to freeze funds in Somalia’s network of remittances led to a wide-scale humanitarian disaster. The UN representative for humanitarian affairs for Somalia warned at the time that “Somalia [was] on the precipice of total collapse.”24

What is noteworthy, however, is that in recent years a number of remittance companies have filled the vacuum left open by the closure of al-Barakaat. Despite compliance with an array of new regulations, Somalia’s remittance companies have continued to multiply providing an array of financial services: regular monthly transfers to families to meet livelihood needs; larger-scale transfers for investment in property and commercial enterprises; and remittances linked to international trade.25 The question remains, however: Do these unregulated remittance inflows finance Islamist militancy and terrorism or do they promote clan over religious identity?

Clan or Islamist Networks? Solving the Problem of Trust

The hawwalat system in Somalia is neither a “pre-capitalist” artifact, nor a peculiarly Islamic phenomenon. Indeed, the hawwalat owes very little to the legal or normative principles of zakat or riba. It is, above all, a modern institution resulting from the disintegration of state and formal institutions and the impact of globalization on Somalia’s economy. Nor is the hawwalat system synonymous with money laundering, as the US legislation implies. Informal transfers are legitimate financial transfers similar to other international capital flows generally accepted as an inherent part of globalization. Indeed, as a number of scholars have noted, market liberalization has substantially loosened state controls on legal economic flows in recent decades. Indeed, much of this scholarship has tended to assume all “unregulated” cross-border flows as necessarily part of “market criminalization,” or “transnational organized crime,” including terrorist financial markets.26 In Somalia, informal transfers are legitimate, and not “illicit,” capital flows. The hawwalat system finances the bulk of imports into the country, provides legitimate profits for those engaged in transferring these funds, and makes resources available for investments throughout Somalia.

The first Somali agency, Dahabshil, was formed in the late 1970s prior to the civil war. It developed first in the refugee camps of Ethiopia and was quickly extended to the interior of Northwest Somalia. At the time, Dahabshil was established to meet the demand of Somalia laborers who, like Sudanese and Egyptians, migrated to the Gulf and sought to circumvent foreign exchange controls. But with the onset of the civil war in the late 1980s, the hawwalat system expanded and has come to represent the only avenue for Somali expatriates to send money to support their families.

The poor education of many Somali migrants means that they are often living on the margins in those host societies and it can take time for families to settle, find incomes, and begin to remit significant amounts of money. Somaliland’s past, its proximity to the Gulf, the flight from war and repression in the 1980s, and easier immigrant conditions have all been factors that helped to promote the Isaaq clan, in the Northwest in political terms. Isaaq families benefited from remittances before other clans and contributed to interclan divisions.27 A large proportion of these remittances went to supply arms not to Islamist militants but clan-based guerillas that helped overthrow the Barre regime. In fact, delegates of the Isaaq-led Somalia National Movement (SNM) received between $14 to $25 million in the late 1980s.28 As with other insurgent groups worldwide, the remittance funded factions in Somalia harbored no specific ideology and depended on the control of domestic territory and local civilian populations to mobilize political support. In this respect Somalia’s rebel groups differed markedly from Islamist militants or the al-Ittihad organization, which rarely rely on domestic support alone, justify their acts of political violence with religious rhetoric, and advocate and implement terrorist operations across the borders of Somalia.29

While hawwalat transfers are not regulated by formal institutions or legal oversight; they are regulated by locally specific norms of reciprocity embedded in clan loyalties and not Islamist extremist ideology. The Islamist al-Ittihad organization and the militants of al-Shabbaab, the main targets of the global anti-terrorist policy in Somalia, have not been able to monopolize these financial transfers precisely because of the manner in which Somalia’s clan networks regulate their distribution in ways that defy discursive and legalistic attributions that have labeled these flows as illicit and clandestine and primarily designed to recruit Jihadist militants.

The hawwalat operate very simply. A customer brings money (cash or cashier’s check) to an agent and asks that it be sent to a certain person in Somalia. The remittance agent charges a fee, typically from 5 to 10 percent depending on the destination. Costs may go up to 12 or 15 percent for larger amounts. The remittance agent then contacts a local agent in Mogadishu – via radio, satellite phone, or fax – and instructs him to give the appropriate amount to the person in question. The remittance agent in the United States or elsewhere does not send any money. Instead, both dealers record the transaction and the relative in Somalia receives the money in two or three days.30 Thus the hawwalat are not as “hidden” or “secret” as US officials have suggested. Remittance companies must maintain detailed, digitized accounting records. One of the factors that makes the Somali hawwalat system different from similar operations elsewhere is that the “address” of the recipient is usually determined by his/her clan or subclan affiliation.

The hawwalat company must be able to pay cash, usually in hard currency, and make sure to resupply the appropriate bank account in due time. For this reason the brokers involved must trust each other absolutely. As a result, recruitment for decisive positions follows clan lines with few exceptions. In Somalia, clan networks, far more than Islamic ties serve the purpose of “privileged trust.” That is, in conventional economic terms, informal clan-based networks reduce the costs of contract enforcement in the absence of formal regulatory institutions and engender both trust and cooperation. The customer too must have confidence that the broker, charged with sending the funds, does not disappear with the cash. Not surprisingly, the customer’s choice of transfer agency is largely dependent on which clan operates the company.

In the Isaaq-dominated northwest, the Isaaq-run Dahabshil Company enjoys 60 percent of the market. As one competitor from the Amal hawwalat, which is also dominated by the Darod clan, put it: “Dahabshil is a family-owned company.”31 Al-Barakaat, which was primarily operated by the Darod clan, possessed only 15 percent of the market in northwest Somalia (see Figure 3.3), but it did control the lion’s share of the business, an estimated 90 percent, in southern and central Somalia.32 Moreover, following the closure of Al-Barakaat, the latter’s market share has been filled by yet another Darod-dominated remittance company, the Amal hawwalat.33

Figure 3.3 Clan networks and remittance transfers in Northern Somalia.

Clearly, Somali Islamists are not the prime beneficiaries of this informal currency trade. Many hawwalat agents can be described as religious34 and are sympathetic to conservative Islamist groups such al-Ittihad, but in political terms this “Islamist” influence is more apparent in the northeast and south where for historical reasons solidarity along clan lines is comparatively weak. Moreover, while the managers of some remittance companies share a conservative Islamic agenda similar to Islamist capitalists throughout the Muslim world, they perceive any form of extremism such as that promoted by the al-Shabbaab organization as not only “un-Islamic” but “bad for business.”35 In the northwest, al-Ittihad and al-Shabbaab militants generally do not enjoy the support of the local population. Since the onset of the civil war, al-Ittihad has chosen to finance the movement, not through the hawwalat, but by attempting to control the port economies of Bossaso and Merka.

In the early 1990s, al-Ittihad did not manage to monopolize the lucrative important-export trade of Bossaso despite a number of military incursions to take over the port by force. Consequently, al-Ittihad (which draws members across clan lines) attempted to impose a new form of “Islamic” rule, but this was short-lived. In the early 1990s, after a bitter armed conflict, the Darod-/Majerteen-backed Somali Salvation Democratic Front (SSDF) wrenched political control from al-Ittihad forces and has administered the port of Bossaso ever since. Since this defeat, al-Ittihad abandoned the few towns and rural outposts it once controlled, and its activists have since integrated into local communities as teachers, health workers, and businessmen. Some members have close links with Islamists in Sudan, primarily in the form of Sudanese-funded educational scholarships. They now represent a mainstream form of conservative Islamist activism, and in recent years they have been primarily interested in expanding their commercial enterprises, providing social services, operating local newspapers, and attaining employment – not global Jihad. This divergence in Somalia’s political developments is due to its own particular historical legacy, which played an important role in determining the eventual disintegration of the state and the very nature of clan conflict.

State Capacity and Social Structure in a Weak State: The Historical Legacy

Somalia is, arguably, the most homogenous country in Africa and the Arab world. All Somalis belong to the same ethnic group (Somali), adhere to Islam, speak the same language, and with minor exceptions trace their ancestry through a single lineage. Moreover, as David Laitin has observed Somalis “have historically harbored a fervent sense of belonging to a distinct national community.”36 Nevertheless, the cultural cleavages in Somalia are equally stark but of a distinct variety. In historical terms clan and regional differences in Somalia marked a highly variable social structure that was belied by Somalia’s ethnic and religious homogeneity. The Somali population is divided into economic categories and regions subsumed under a complex of clan networks. The clan system is one that anthropologists’ term “acephalous,” a segmentary lineage system in which social order is maintained by balancing opposing segments on the same social level, clans and subclans against each other and lineages, families, and individuals against other lineages, families, and individuals. Although members of a family, lineage, or clan may unite against an external threat, the unity is often undermined by internal rivalry precipitated by exogenous developments. The major branches of the Somali lineage system are based on the pastoral clans of the Dir (in the northwest along the Djibouti border), Darod (in the south along the Kenyan border, and the northeast), Isaaq (in the northwest), Hawiye (in the central region around Mogadishu), and the sedentary agricultural clans of the Digil and Rahanwayn in the more fertile regions in southern Somalia (see Clan Chart in Appendix).

In the precolonial period, the delicate balance of power among clan families in Somalia had long been maintained by the traditional authority of Somali elders (Isimo) and the institution of the Xeer. The Xeer functioned as a type of social contract, which transcended blood and lineage ties and, informed by Islamic teachings, laid a foundation upon which social conflicts ranging from property disputes to a variety of social transactions could be resolved. Thus, interclan conflict was far from inevitable, for in addition to establishing a delicate and complex web of negotiated agreements, the Xeer stipulated that the leader (Sultan) of the ad hoc deliberative assemblies (Shirs) that formed the functional basis of the Xeer had to be chosen from one of the outside clans to balance the power of the more dominant clan families.37 In addition, the decisions of the deliberative assemblies were enforced through a process called the guddoon. The guddoon essentially refers to the ratification and sanctioning of consensus decisions reached by elders of the community organized around the deliberative councils. Like other traditional dispute resolution institutions, the guddoon emphasized consensus decision-making. Enforcement of the Isimo’s rulings was based on moral authority and the Islamic concept of ‘Ijima’ or consent of the people.

During the colonial era in the nineteenth century what Somali nationalists’ term “Greater Somalia” became a focus of intense colonial competition that partitioned the territory among British Somaliland in the north, Italian Somaliland in the south, and French Somaliland (present-day Djibouti) in the northwest. The territory of the Ogaden in the west was occupied by imperial Ethiopia. The hitherto resilient Xeer system was disrupted, and the traditional authority of the Isimo gradually eroded, as arbitrary force came to determine the relationship between increasingly centralized colonial states and increasingly fragmented Somali communities. Somali scholar, Abdi Samatar, has argued that it was this development “rather than Somali society or traditions which represents the genesis of contemporary Somali warlordism.”38 To this observation one can add the disruptive development of distinct clan-based economies induced by local and international developments that replaced the institution of the Xeer with new forms of authority based on informal social networks coalescing around clan ties.39

The British and Italian colonial traditions left distinctly different imprints in northern and southern Somalia. Considerable variations in education, legal systems, tariffs, customs dues, and patterns of trade distinguished the British administration from that established by the Italians.40 The Italians, hoping to garner some economic benefit from their colony, introduced large-scale banana plantations in the inter-riverine areas of the south and established more advanced educational and health services, which largely explains the domination of jobs and other privileges by southern bureaucrats in the postindependence era. In the north, the British administration introduced the expansion and commoditization of livestock trade, promoting the fortunes of a handful of northern merchants and state bureaucrats who broke out of precapitalist moral economic ties and began to grow livestock for purposes of trade only. However, most of the surplus (rent) captured by the merchant and the state elite was not invested in productive enterprise; in other words “the state and merchant capital were not progressive forces in terms of laying the foundation for a new and regenerative regime of accumulation.”41 Of great importance in the Somali case is that Somalia’s acephalous social structure provided no “native” leadership on which the colonial administration could build state institutions. In neither region of the country was the colonial administration able to incorporate peasant and pastoral production into the capitalist economy.

As a result, the Somali petit bourgeoisie that assumed control of the postcolonial state in 1960 inherited a “weaker” state, which in contrast to Sudan in the same period possessed “weak” extractive capabilities. The fiscal basis of postcolonial Somalia was marked from the beginning by the absence of any form of direct taxation on production as the vast majority of households in the rural areas (the bulk of the Somali population) retained a productive base through their full control of land. Nor did the colonial state establish a marketing board as in Sudan and other parts of Africa to oversee Somalia’s most significant source of revenue, livestock trade. In the case of the Italian colony indirect taxes, primarily in the form of custom duties, constituted 73 percent of the state’s locally generally revenues by the late 1950s and 80 percent in the British protectorate to the north.42 These weak regulatory mechanisms would continue throughout modern Somali history with the Siad Barre regime (1969–1990) pursuing similarly indirect avenues of extraction. In political terms, state-society relations would continue to be marked by the exigencies of clientelism, and in economic terms by tributary extractive relations (often imposed by force) focused on consumption rather than productive development.43 Of course, the Barre regime pursued far more “predatory” policies designed exclusively to maximize revenue for his own clan (Darod) family and eventually his Marehan subclan through unprecedented violence.

Another weakness directly related to the first is Somalia’s heavy dependence on foreign assistance for its fiscal health. Both the Italian and the British administration critically depended on the treasury in the home countries and in both cases expenditures consistently outstripped locally generated revenue. The colonial legacy thus set a pattern in which foreign aid would continue to be more significant than domestic production and consequently, the state became the prime focus of not only political authority but accumulation until the critical expansion of the parallel economy in the 1970s. Even at this early date, and owing to the predominance of pastoralism, Somalia showed the beginnings of what a prominent scholar of Africa has termed a “society without a state … the latter [sitting] suspended in mid-air over society.”44 Moreover, in Somalia, associational life in the rural areas was governed by clan loyalties, based on informal networks of mutual obligations. These reciprocal relations, however, were drastically eroded leading to the rise of the politics of ascription and violence. This resulted not because of increasing state penetration as many scholars have argued, but rather due to the manner in which this intervention occurred.45 The legacy of a weak financial extractive base and dependence on foreign aid would in the context of the international economy result in the gradual disintegration of the Somali state.

Origins of State Disintegration: Labor Remittances and “Clan Economies”

As in Egypt and Sudan, in Somalia remittances from expatriate labor in the Arab Gulf states were also the primary source of foreign currency for fueling the expansion of the parallel market and signaled a boom for domestic importers and private entrepreneurs. Here too the weight of these capital inflows where not reflected in the few aggregate national income figures available for those years: the importance of repatriated monies in creating and expanding the parallel economy during the boom, and the predominance of Somalia’s pastoral economy wherein a great part of internal trade is in livestock escaped official control. Indeed, the greater part of the national income derived not from domestic activities as such, but from remittances of Somali workers abroad, sent through informal channels; the majority of exports and imports were transacted in the parallel economy at free-market exchange rates. Still, national account figures as early as 1981 estimated that remittances equaled almost two-fifths of Somalia’s GNP.46

The important variant in the Somali case is that unlike in the more urbanized labor exporters, there are no clear-cut divisions along occupation lines such as, for example, wage earners and traders. That is, whereas Egypt and Sudan possess a politically influential “modern commercial sector” and more resilient horizontal social formations along the civil society divide, Somalia’s most distinctive characteristic is that over half of its population is dependent on nomadic pastoralism for its livelihood, a proportion not exceeded in any other country in the world.47 It is within this context that one can speak of the development of two intertwined fragmented markets.

Thus, it is crucial to avoid reification of the “parallel market.” Somalia’s distinctive socioeconomic structures necessitate highlighting two parallel markets: one centered around foreign currency exchanges (the parallel market) and the other related to livestock trade which played an important role in fueling the expansion of informal financial networks as we shall see later. Moreover, what is equally significant is the fact that operating together these parallel markets fragmented further resulting in the expansion of a thriving urban informal sector. Operating strictly on the basis of familial relations this sector included a host of enterprises ranging from food processing, construction, and carpentry to tailoring and retail trade (commerce).48

Predictably, the growth of the parallel market coincided with the increasingly diminishing economic role of the state. As one Somali economist has observed, “while throughout the 1970s wages had stagnated particularly in the public sector [which accounted for the bulk of employment]; inflation had doubled in eight years, 1970–78.” Moreover, despite the “shrinkage” of the state’s extractive and distributive capacity in this period “no poverty was in evidence and shops were full of imported goods.”49

Under the Siad Barre regime the Somali state made a special effort during the 1970s to attract Arab capital. In 1974 it joined the Arab league in recognition that the explosion of oil prices meant hefty payoffs for those identifying themselves as Arabs. As Somalia became more dependent on Arab finance, more Somalis engaged in trade with Arab middleman, worked for aid projects funded by Arab funding institutions, and an increasing number spent a great part of their working lives in the Arab states. But while the private sector prospered as a quarter of a million Somali merchants took advantage of the massive oil profits of the Arab oil exporters, the state continued to be hampered by debt and regression. Somalia’s debt, which stood at 230 million US dollars in 1975, rose to more than 1 billion by the end of the decade.50 By 1981, Somalia, now more closely allied with the West, reached an agreement with the IMF and was compelled to decrease the state’s role in the hitherto excessively regulated economy and devaluate the Somali shilling in exchange for much-needed hard currency.51

The parallel economy was flourishing, as it had been in Sudan over the same period, and its size and relative efficacy in capital accumulation, particularly in relation to the declining extractive capabilities of the state, forced a response from the latter. One can note with great interest that Siad Barre felt compelled to intervene in the parallel sector for the same reasons that drove Nimeiri to encourage Islamic banks in Sudan which themselves were aided by the Gulf countries’ “breadbasket” development plans that were later aborted. In Somalia too the formal economy was in shambles as a result of the external capital inflows in the form of labor remittances, a costly war with Ethiopia over the Ogaden in 1977–1978, and the decline of assistance from the Gulf. As a consequence, Barre was left with a narrow political base centered by the late 1980s around his own Marehan subclan. He thus sought to attract revenue from the private sector, which was of course inextricably linked to the parallel market. Whereas Nimeiri’s shrinking political and economic base led him to promote Islamic financial institutions and indirectly tap into the lucrative parallel market, no such option was available to Barre. Instead, Barre simply “legalized” the black-market economy by introducing what is known as the franco valuta (f.v.) system in the late 1970s. Barre did this in the hope of generating more indirect taxes (i.e., custom duties) from the booming import-export trade that resulted from the boom in remittance inflow to the domestic economy.

Under this system the government allowed traders virtual freedom to import goods with their own sources of foreign exchange – that is, through parallel market transactions.52 For their part, the money dealers (the Somali version of Tujjar al-Shanta) remitted the proceeds of the foreign exchange purchased from Somali workers abroad to their relatives back home. These proceeds were remitted at the free-market rate. In essence then, the f.v. system fully circumvented the state in procuring imported goods for Somali consumers – brought by Somali dealers, from money earned by Somali workers abroad and purchased by the workers’ relatives at home.

The effect these developments had in displacing old state sectors and strengthening an autonomous private sector organized around clan families was enormous. It was estimated in 1980 that 150,000 to 175,000 Somalis worked in the Gulf countries, mostly in Saudi Arabia, earning five to six times the average Somali wage. A great part of this was repatriated to the mother country, especially after the late 1970s, because of the attractive exchange rates offered by the hawwalat currency dealers. This repatriated money, which continued to evade official bureaucratic institutions, nearly equaled two-thirds of the GNP in the urban areas.53

Labor, however, was not the only export: of equal importance is the effect the burgeoning parallel market had on livestock exports, traditionally Somalia’s foremost foreign exchange earner. Remitted earnings were invested in livestock production and trade with the result that the livestock sector boomed. Like banana production, centered in the south, livestock production remained in private hands. But unlike banana exports, which as a share of total export value declined from 26 percent in 1972 to just 8 percent in 1978, the livestock trade rose from 40 percent of total export value in 1972 to 70 percent by the end of the decade.54 The livestock traders prospered greatly, taking advantage of the difference between the officially set producer price and the market price in Saudi Arabia, which was under constant inflationary pressure.

The Barre government allowed the livestock traders to import goods from their own personal earnings without tariff restrictions. The state took its share by charging a livestock export tax of 10 percent.55 In 1978, livestock exports amounted to 589 million shillings. The traders based in Saudi Arabia earned a windfall profit of $93.5 million most of which was recycled back into the parallel market in Somalia.56 As one study noted “efforts by the [state] to mobilize resources [were] met by increased reliance on parallel markets, thereby further eroding the economic base of government and making coercion appear the only viable means of maintaining control.”57 As a result Somalia’s industrial base, always relatively small both in terms of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and in relation to the overwhelming contribution of the livestock sector and remittances from abroad, deteriorated further after the late 1970s. By the mid-1980s it accounted for only 5 percent of GDP.58

Remitted earnings from the large-scale movement of Somalis for wage employment in the Gulf were invested in the livestock sector, the part of the economy perceived to have the best comparative advantage. This had a dramatic effect on socioeconomic structures, particularly in northwest Somalia where the Isaaq clan monopolizes the trade in livestock. The expansion of the livestock market, the investment in wells and water tanks (birkets) caused the beginning of interclan strife. Due to their close proximity to Saudi Arabia and its intimate links with the Gulf Arabs, the Isaaq clan benefited the most from this livestock trade and came to dominate this sector in the boom period. In particular, the Isaaq made inroads into the Haud, a rich grazing plateau stretching from the heart of Isaaq territory in the north to the Ogaden region along the Ethiopian border. Thus, not only did the Isaaq come into economic conflict with the Ogaden clan but through them with the state. The Ogadenis (a subclan of Siad Barre’s Darod clan) comprised the overwhelming majority in the military. The aggravation of these ascriptive cleavages by linkages with the Gulf and the doomed war with Ethiopia over the Ogaden (1977–1978) precipitated increased competition over scarcities in the recession.

What the f.v. system meant in terms of the state’s extractive capacity is the virtual cessation of the government’s attempt to control incomes in the country. Up to 1977 the government still retained a semblance of regulatory institutions based on nationalization of banking and plantations, nationalization and control of wholesale trade, and control over the importation and pricing of foodstuffs, rents, and wages. The state hoped to capture revenue from the parallel market via the f.v. system by maintaining control over wholesale trade and pricing policies of essential commodities, but this ensured only partial control over the income of traders. The f.v. system beginning in 1978 meant traders could import anything so long as they did so with their own foreign exchange leading to the rise of wealthy traders or commercial entrepreneurs at the expense of wage earners employed by the shrinking state bureaucracy. These increasingly wealthy traders were well placed to finance the various rebel organizations and “warlords” that would dominate Somali politics following the collapse of the state.

In contrast to Egypt and Sudan, where new middle classes arose aided by labor migration and the income-generating opportunity this provided, in Somalia the diminution of the formal economy and labor remittances determined a new pattern of clan conflict. This was because as the formal economy diminished giving way to a veritable boom in the parallel sector, two overwhelming factors emerged. First, many urbanites were members of trading firms (both in livestock and commodities) that were increasingly organized around clans, but most often subclans. Second, most families relied on monies received from family members residing abroad for their livelihood.

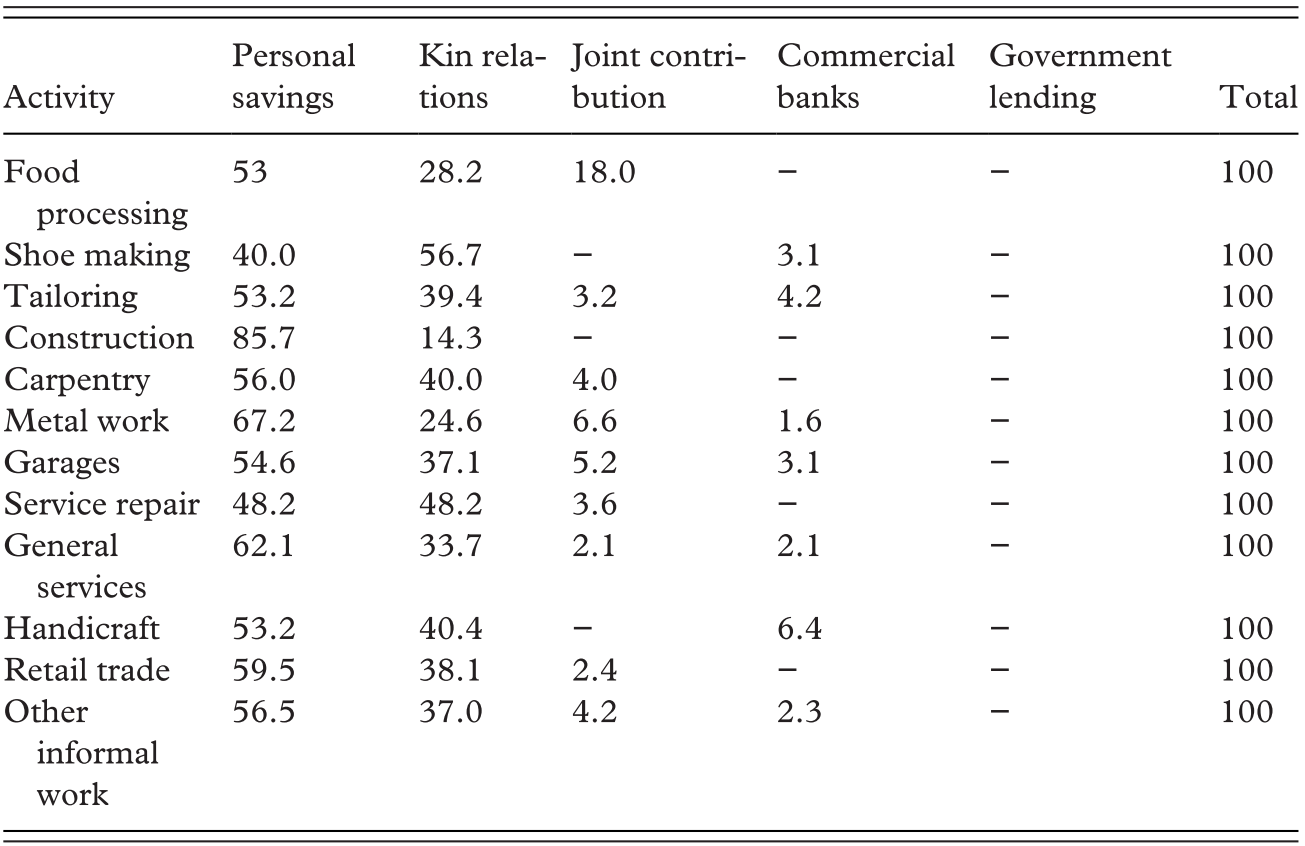

By the mid-1980s, 93 percent of all capital investment in informal enterprises in Mogadishu was personal savings (derived mainly from remittance) and loans from relatives and friends. Formal lending from commercial banks was no more than 2.3 percent of the total and credit allocation from governmental sources was nonexistent (see Table 3.1). In addition, as a study by the International Labor Organization discovered there were “no specific structures to meet the needs of the informal sector and to mediate between the artisans and informal financial institutions so as to facilitate the former’s access to credit.”59

Table 3.1 Sources of finance for various informal microenterprises in Mogadishu, Somalia: 1987 (in percent)

| Activity | Personal savings | Kin relations | Joint contribution | Commercial banks | Government lending | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Food processing | 53 | 28.2 | 18.0 | − | − | 100 |

| Shoe making | 40.0 | 56.7 | − | 3.1 | − | 100 |

| Tailoring | 53.2 | 39.4 | 3.2 | 4.2 | − | 100 |

| Construction | 85.7 | 14.3 | − | − | − | 100 |

| Carpentry | 56.0 | 40.0 | 4.0 | − | − | 100 |

| Metal work | 67.2 | 24.6 | 6.6 | 1.6 | − | 100 |

| Garages | 54.6 | 37.1 | 5.2 | 3.1 | − | 100 |

| Service repair | 48.2 | 48.2 | 3.6 | − | − | 100 |

| General services | 62.1 | 33.7 | 2.1 | 2.1 | − | 100 |

| Handicraft | 53.2 | 40.4 | − | 6.4 | − | 100 |

| Retail trade | 59.5 | 38.1 | 2.4 | − | − | 100 |

| Other informal work | 56.5 | 37.0 | 4.2 | 2.3 | − | 100 |

Consequently, the scramble over control of foreign exchange led to widening schisms between clan, subclan, and family households. It is with the rise of these clan-centered economies that one can trace the development of clanism, which was reinforced during the recession period and solidified to the greatest degree in what one notable Somali scholar termed “Dad Cunkii,” the era of cannibalism.60 While in Egypt and Sudan a distinct formation of an Islamist business coalition was “reproduced” organized around privileged financial institutions operating more or less privately, albeit with state patronage, the development of distinct class formation within Somalia’s large parallel sector did not occur. This key difference was due to two factors: first, the very dearth of private, formally organized institutions (i.e., official banks and publicly registered enterprises) necessitated the reliance on household economies; second, Barre not only pitted one clan against another in his elusive search for legitimacy as has been widely noted, but once he ran out of external funds he intervened in the economy in order to finance the important patronage system that kept key social constituencies (clans and individuals) wedded to participation in the government. However, with the expansion of the parallel economy, the prebendalist system quickly became irrelevant in Somali politics. The typical wage earner was more likely than not to belong to a trading household and while the incomes of some members of an extended family fell, those of others increased. In other words, few Somalis of any clan could afford to rely on state patronage for their well-being. As Jamal writes:

The overwhelming fact during this boom period is that apart from government employees whose salaries [were] regulated, everybody else in the urban economy operated in the parallel economy, which unlike the formal economy, is essentially a free-market economy. This economy is, moreover, characterized by the vast network of inter-familial relationships that exist in Somali society.61

However, despite the liberal orientation of the Somalia economy engendered by its informalization this did not lead to a pattern of equalization in terms of income distribution as some scholars have maintained.62 In fact, while the income of families increased dramatically in this period this in itself depended on the proximity and connections the various clans had in terms of access to informal financial networks and livestock trade. For example, while the Isaaq clan of the northwest managed to accumulate capital in a manner that allowed them to carve out an independent financial base for themselves, at the other end of the scale the Rahenwein, Digil, and the “Bantus” of the south emerged the losers in the battle over foreign exchange. The Bantus in particular suffered as a result of declining productivity in the agricultural sector. Under Italian colonial rule they had become dependent on wages earned from the planting and harvesting of export crops (especially bananas) along the Shebelle river.63 Moreover, since along with the Digil and Rahenwein the Bantus did not share the lineage systems of the major nomadic clan families, they had little financial resources they could mobilize to exercise their “exit” option in the informal realm. In 1992 and 1993 these three clans, located in what came to be known as the “triangle of death,” were disproportionately affected by the war-driven famine in the area.

By the early 1980s, at the height of the boom period, the parallel market, while clearly encouraged by the state via the f.v. system, had so weakened formal regulatory mechanisms that the IMF found itself in the ironic position of arguing against the sector of Somalia’s economy that was functioning on a free-market basis:

[The franco voluta system has] generated distortions and contributed to inflationary pressures, deprived the authorities of the foreign exchange that would otherwise have been channeled through the banking system and of control over consumption-investment mix of imports.64

The economic crises in the 1970s and 1980s were significantly compounded by decades of poor financial management and high levels of corruption wherein, as one Somali economist observed, the banking system was largely a financial tool for Siad Barre and a small group of elites with political influence.65 Indeed, by the end of the decade there was little question that Somalia’s formal economy was in shambles. In 1987 and 1989, the public sector deficit stood at 34 percent and 37 percent of GDP; foreign-debt service over exports and total foreign debt in relation to the gross domestic product (GDP) reached 240 percent and 277 percent in 1988 and 1990, respectively, and state expenditure on social services, including health and education, declined steeply to less than 1 percent of GDP by 1989.66 Figure 3.2 illustrates the ways in which the parallel market altered state-society relations and thereby ethnic politics during the remittance boom.

Explaining Somali’s Divergent Path

In Somalia, during the boom, institutional links between state and society were destroyed and replaced with regional and clan affiliations that due to the type of parallel economy and Somalia’s social structure were adept at capital accumulation. This same general process occurred in Egypt and Sudan. But whereas, in Somalia clan-centered economies operating as a form of embryonic trade unionism dominated the parallel market in that the household was best suited to capture remittance inflows, in Egypt and Sudan by contrast, historical, structural, and cultural conjectures led to the emergence of strong private sectors affiliated with Islamic financial institutions that served as mediators between the state and those segments of civil society engaged in “black market” activities.

In Egypt and Sudan, an Islamist-commercial class based in the urban areas was, through the bridging of the official-parallel market divide and the cooperation of the state, not only able to ‘reproduce’ itself but also to consolidate its political base. This development accompanied a major weakening of the state’s extractive institutions as result of decreasing sources of official assistance, the decline in general productivity, and, in the case of Sudan, the resurgence of civil war in 1983. Utilizing the parallel market as their springboard and their privileged relationship to the Sadat and al-Nimeiri regimes, respectively, Egyptian and Sudanese Islamists were well positioned to expand their recruitment drives and popularize their movements.

Figure 3.4 Informal transfers and ethnic politics in the remittance boom in Somalia

Sadat and Nimeiri’s strategies in Egypt and Sudan, respectively, confirm Tilly’s observation that even the strongest formal state administration relies on its relationship with people and their networks (including informal economic networks) to channel and control resources and to benefit from the legitimacy of these relationships.67 But while in Egypt the stability of the state persisted despite the strong emergence of Islamists in civil society, in Sudan the new partners in this reconfigured hegemonic group ended up swallowing their original state patrons and succeeded in forming their own hegemonic alliance. This alliance, between political and commercial networks is what ushered in the onset and consolidation of the Islamist authoritarian regime of Omer Bashir.

By contrast, in Somalia, the expansion of the parallel economy facilitated the rise of violent, centrifugal tendencies. Unlike Egypt and Sudan, in Somalia no single coalition in civil society emerged as dominant precisely because of a lack of strong horizontal cleavages, and distinct class formations. Moreover, the informal channels utilized to transfer remittances played an important role in the construction of new identity-based politics in that they reinforced the importance of clan, even more than “Islam,” as the most important social and political institution in Somali life. That is, with the expansion of the parallel economy, the politics of ethnicity and clan-based commercial networks eclipsed the power of the state. This is because ties of kinship remained crucial to the risky commercial transactions associated with the burgeoning parallel economy. Indeed, far from dissolving previously existing social ties in the Weberian sense, in Somalia market expansion crucially depended on the creation and recreation of far more extensive interpersonal relations of trust embedded in clan networks.

Thus, in contrast to Egypt and Sudan, in Somalia, informal economic activities in the context of far weaker state capacity coalesced around clan cleavages setting the stage for the complete disintegration of the state. As noted earlier, in the early 1980s, the IMF cautioned Barre against his continued promotion of the parallel market in Somalia, but this warning came too late and went unheeded. The recession of the 1980s would not only lead to increasing predatory and violent state behavior, but it would also galvanize an opposition organized around clan families that had enjoyed relative growth and economic autonomy in the boom. Not surprisingly, as discussed in Chapter 6, the unraveling of the Somali state would begin with the insurrection of the Isaaq, the most important beneficiaries of the fading era of abundance.