Introduction

In the first part of this book (Chapters 3–7) I outlined a personal perspective and approach to the dynamics of human long-term coevolution with the environment, grounded in the evolution of human cognition. In Chapter 8 I have presented a narrative indicating the perspective on the history of human–environmental coevolution that this approach leads to, and in Chapter 9 I presented an outline conception of the interaction between society and its environment in terms of dissipative flow structures. Chapter 10 presented a more detailed case study of the dynamics of long-term evolution in a socioenvironmental system. In Chapter 11 I added a theoretical underpinning to that perspective and Chapters 12 and 13 presented my approach to the process of invention that is at the core of social and technological change. In Chapter 14, I showed how modeling dynamical systems can help us understand the emergence of urbanization.

These chapters have tried to pave the way for a focus on another central theme of the book: the present and its relationship to the future. In this part of the book, I will move our focus from the distant past toward the more recent past, the present, and the future. Chapters 16–18 argue that the information and communications technology revolution is an underestimated accelerator of the sustainability conundrum in which we find ourselves. Chapters 19–21 are dedicated to a discussion of potential futures.

The Rise of Western Europe 600–1900

To prepare the way, I will first present the last 1,500 years or so of western European history from the dissipative flow structure perspective. During that millennium and a half, we see a gradual strengthening of the urban (aggregated) mode of life, but this millennial tendency has its ups and downs and manifests itself in different ways. A second long-term dynamic is that of European expansion and retraction. Both reflect different ways in which the European socioeconomic system strengthened itself vis-à-vis the external dynamics that it confronted. To quantify these attributes, we will emphasize changes in the following proxies, where available:

The demography of the area concerned: relative population increases and decreases;

The spatial extent of European territorial units, as a measure of the area that a system can coherently organize;

The spatial extent and nature of trade flows as a measure of the information-processing potential between the center and the periphery, and thus of the area from which raw resources are brought to the system – its material footprint;

The density and extent of transport (road, rail, water) and communication (telephone, etc.) systems as a proxy for the density of information flows;

The degree and gradient of wealth accumulation in the system, as an indicator of innovation and the value gradients between the center and its periphery;

The innovativeness of particular towns, regions, and periods.

Many of these proxies cannot comparably be measured for each and every historical period and region. Moreover, they operate at different rates of change. But proxies are for the moment all we have if we want to cover the whole period. For subsets of it, interesting datasets are found in Piketty (Reference Piketty, Saez and Stantcheva2013) but also in Le Roy-Ladurie (Reference Le Roy Ladurie1966 [1974], Reference Le Roy Ladurie1967 [1988]), Slicher van Bath (Reference Slicher van Bath1963), and many others involved in agrarian history, particularly represented in the French journal Annales: Économies, Sociétés, Civilisations.

The Dark Ages

After the end of the Roman Empire we observe across Europe a weakening of society’s structure and coherence (e.g., Lopez Reference Lopez1967). Between 600 and 1000 CE, the fabric of society reached a high level of entropy (both in the sense of growing disorder and in the sense of reduced dissipation of the flow structure governing the dynamic) in western Europe, where the traditions of Greco-Roman urban culture were only conserved to a minimal extent. In South-Eastern Europe, under the Byzantine emperors, appropriate decentralization ensured that more of the culture developed for another millennium.

We will in this chapter mainly focus on western Europe. In this period, there was an enormous loss of knowledge, in crafts and trades for example, as well as an abandonment of infrastructure. The flow structures exchanging organization for energy and matter were limited to the immediate environment. Trade and long-distance contact virtually disappeared, towns saw their population dwindle (the city of Arles was for some time reduced to the perimeter of its Roman arena), and most villages were abandoned. Society fell back on local survival strategies and much of Roman culture was lost. Only the Church maintained some of the information-processing skills it had inherited, especially writing and bookkeeping, and a semblance of long-distance interaction.

The First Stirrings: 1000–1200

This was a period of oscillation between different small systems, in which cohesion alternated with entropy even at the lowest levels. In Northern Europe, trade connections forged in the (Viking) period before 1000 CE led to the transformation of certain towns into commercial centers, later loosely federated into the Hanseatic League. But these towns remained essentially isolated islands in the rural countryside, linked by coastal maritime traffic.

Duby’s classic study (Reference Duby1953) shows how, from about 1000 CE, society in Southern France began to rebuild itself from the bottom up. Although the urban backbone of the Roman Empire survived the darkest period, a completely new rural spatial structure emerged, even relatively close to the Mediterranean. There, in a couple of centuries of local competition over access to resources, various minor lords climbed the social ladder by conquering neighboring resources and positions of potential power, leading to the emergence of a new (feudal) social hierarchical structure.

The local leaders with the best (information-processing and military) skills were able to attract followers by providing protection for peasants who bought into the feudal system. The peasants in turn provided surplus matter and energy to support a small army and court. In the process, more wealth accrued to the favored, and we see the resurgence of a (very small and localized) upper class with a courtly culture in the so-called “Renaissance of the twelfth century that included tournaments, troubadours, and other (mostly religious)” artistic expressions in Southern France and adjacent areas. A similar process occurred in the Rhineland, where a separate cultural sphere (Lotharingia, named after Charlemagne’s son Lotharius who inherited this part of his father’s empire) developed on both banks of the river. Further east, in Germany, this period saw the decay of whatever central authority the Holy Roman Empire had and the rural colonization of Eastern Europe. At this time parts of Europe began to look outward: it was the time of the crusades against Islam (1095–1272) that culminated in 1204 in the (short-lived) conquest of Constantinople, which brought large amounts of information to western Europe in a – for the times – very efficient manner.

The Renaissance: 1200–1400

Three major phenomena characterized the next period: (1) the establishment of a durable link between the southern and the northern cultural and economic spheres, (2) the major demographic setback of the Black Death in the fourteenth century, and (3) the beginnings of the Italian Renaissance. The link between south and north was established in the eleventh and twelfth centuries, overland from Italy to the Low Countries via Champagne, and then connecting with the maritime British and Hanseatic trade systems. In the thirteenth century this connection became the main axis of a continent-wide trading and wealth creation network, enabling urban and rural population growth (Spufford Reference Spufford2002) and eventually driving rural exploitation in many areas to the limits of its carrying capacity, as well as pushing farming out toward more distant and less fertile or less convenient areas.

The impact of the bubonic plague was very uneven. Where it hit badly, it profoundly affected both cities and the surrounding countryside, bringing people from the periphery into the traditionally more populous urban areas (where the plague had hit hardest), thus increasing both the degree of aggregation of the population and its average per capita wealth (see Abel Reference Abel1966). Other profound changes occurred in the cultural domain, including a reevaluation of the role of religion, life and death, society and the individual, together shaking society out of its traditional ideas and patterns of behavior. (Some of these are mentioned in Chapter 3.)

These phenomena contributed to a localized era of opportunity in Northern Italian cities, where the interaction of cultural, institutional, technical, and economic inventions led to a uniquely rapid increase in the information-processing gradient between the urban centers and the rest of the continent. In this Renaissance, architecture and the arts flourished, while the foundations were laid for modern trade and banking systems. Padgett (Reference Padgett, Arthur, Durlauf and Lane1997), for example, describes brilliantly how financial and social innovations went hand in hand to transform the Florentine banking system, drawing in more and more resources and investing them in an ever–widening range of commercial and industrial undertakings that, in turn, transformed practices in these domains. Long-distance trade reemerged as a major force in development, for example between Venice and the Levant; the travels of William of Rubruck, John of Montecorvino, and Giovanni ed’ Magnolia are examples of these contacts, from the mid-thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries.

Many of the ideas developed in northern Italy were relatively quickly adopted in the trading centers in the Low Counties, such as Ghent and Bruges, which became rich and powerful based on the wool and cloth trade with England.

The emergence of a bourgeoisie in these places set the scene for systemic change: from this time onward, reaching the top of the heap was limited to geographic areas where urbanization led to concentrations of more – and more diverse – resources, as well as more effective information processing because towns were linked in Europe-wide information flows.

The Birth of the Modern World System: 1400–1600

This period marks the central phase in the continent-wide transition from a rural, often autarchic, barter economy to a monetized economy driven by towns, in which craft specialization and trade set the trend (Wallerstein Reference Wallerstein1974–1989). The transition introduced fundamentally different system dynamics. The dominant cities are increasingly market- and trade-based heterarchical structures, as opposed to the egalitarian and hierarchical ones in the rural landscape. Simon (Reference Simon1969) defines such structures as those emerging, in the absence of hierarchy and overall control, from the interaction of individual and generally independent elements, each involved in the pursuit of separate goals, and with equal access to (incomplete) information; competition for resources characterizes such organizations. As we saw in Chapter 11, contrary to hierarchical systems, heterarchical ones do not strive to optimize behavior; they can link much larger numbers of people, especially if they are organized as networks with nodes, and they are more flexible.

In this first phase of urban dominance, the world of commerce and banking expanded across different political entities, cultures and continents. Much of both southern and northern Europe, including Britain, Scandinavia, and the Baltic, were now integrated into the European world system. Rural areas saw their interaction with towns increase. Cities began to look attractive to farmers in an overpopulated countryside continually disturbed by armies acting out others’ political conflicts, and this led to a wave of rural emigration to towns, relieving the population pressure in the countryside and keeping the urban labor force cheap. That in turn enabled industrial expansion.

This period is the heyday of city power. Urban centers were not controlled by political overlords; rather, they controlled these overlords’ purse strings, as in England (London) and the Netherlands (Amsterdam). Urban elites put to work the enormous gains in information-processing capacity made during the Renaissance. Through relatively unregulated commerce and industry, commercial houses (e.g., the Fuggers) amassed enormous wealth, used it to bankroll the political conflicts and wars that disrupted the continent, and thus extended their economic and political control over much of the continent. To this effect, they created extensive information-gathering networks linking every important commercial, financial, and political center.1

This is also the period of the first voyages to other continents. By investing in these distant parts, European traders added new areas along the information-processing gradient, in which the commonest European product (such as glass beads) had immense value in faraway territories, while the products from those regions (such as spices) had a high value in the traders’ homelands. The huge and immediate profits made up for the risks, and this long-distance trade initiated for the trading houses centuries of control over an increasingly important resource-rich part of the world. As a result, this period has the steepest information gradient from the center of the European World System to its periphery, and the steepest value gradient in the reverse direction. But toward the end of the period that gradient began to level off in the European core, as cities in the hinterland, and eventually territorial overlords, began to seriously play the same game.

The Territorial States and the Trading Empires: 1600–1800

The rulers of Europe had inherited legitimacy, or something approaching it, from the Roman Empire, but that did not pay the bills. Their need to keep up a certain status was a financial handicap until they could leverage their legitimacy against financial support by exchanging loans for taxes as their principal source of income. A degree of territorial integration and unity was achieved in many areas by 1600,2 transforming the heterarchical urban systems into hybrid heterarchical-hierarchical ones including both towns and their hinterlands.

The regions that first achieved this (Holland, England, and Spain) had the most extensive long-distance trade networks providing the steady income necessary to maintain rulers’ armies and bureaucracies. As a result, the city-based economic system was transformed into one that involved the whole of the emerging states’ territory. Inevitably, the value gradient leveled out as the Europeans in the colonies assimilated indigenous knowledge and shared their own knowledge with the local populations, but this was for some time counterbalanced by the discovery of new territories, the introduction of new products in Europe, the improvement of trade and transport, and the extension of the reach of the trading empires. But ultimately the leveling of the information gradient led toward independence, as in the case of the USA, or, as in the East Indies or Africa, to the transformation of the trading networks into colonies under military control. These saw the local production of a wide range of necessities for the colony as well as western-controlled production systems for products needed in Europe, and a degree of immigration from Europe. As a result, the European core and the colonies became economically more dependent upon one another.

The same leveling off occurred in Europe as more people began to share in the production of wealth and its benefits. The profits from long-distance trade enabled an increase in the industrial base of the main European nations, achieved by involving more and more (poor) people in production and transformation of goods. The tentacles of commerce and industry spread into the rural hinterlands, aided by the improvement of the road systems. As a result of both these systemic changes, the flow structure that had driven European expansion became vulnerable to oscillations between rich and poor, separated by a growing wealth gap.

An important milestone in this process, which I consider in Chapter 18, is the Treaty of Westphalia (1648), which established the structure of European international relations for several centuries, until very recently. It was based on the principle that rulers of nations would not interfere in other rulers’ territories, and was thus a way to help stability in “interesting times.”

Using the term that I introduced in Chapter 7, one could say that with this event the European nations solidified themselves as Bénard cells, independent, coterminous units that were each driven by dissipative flows of energy and information.

The Industrial Revolution and its Aftermath: 1750–2000

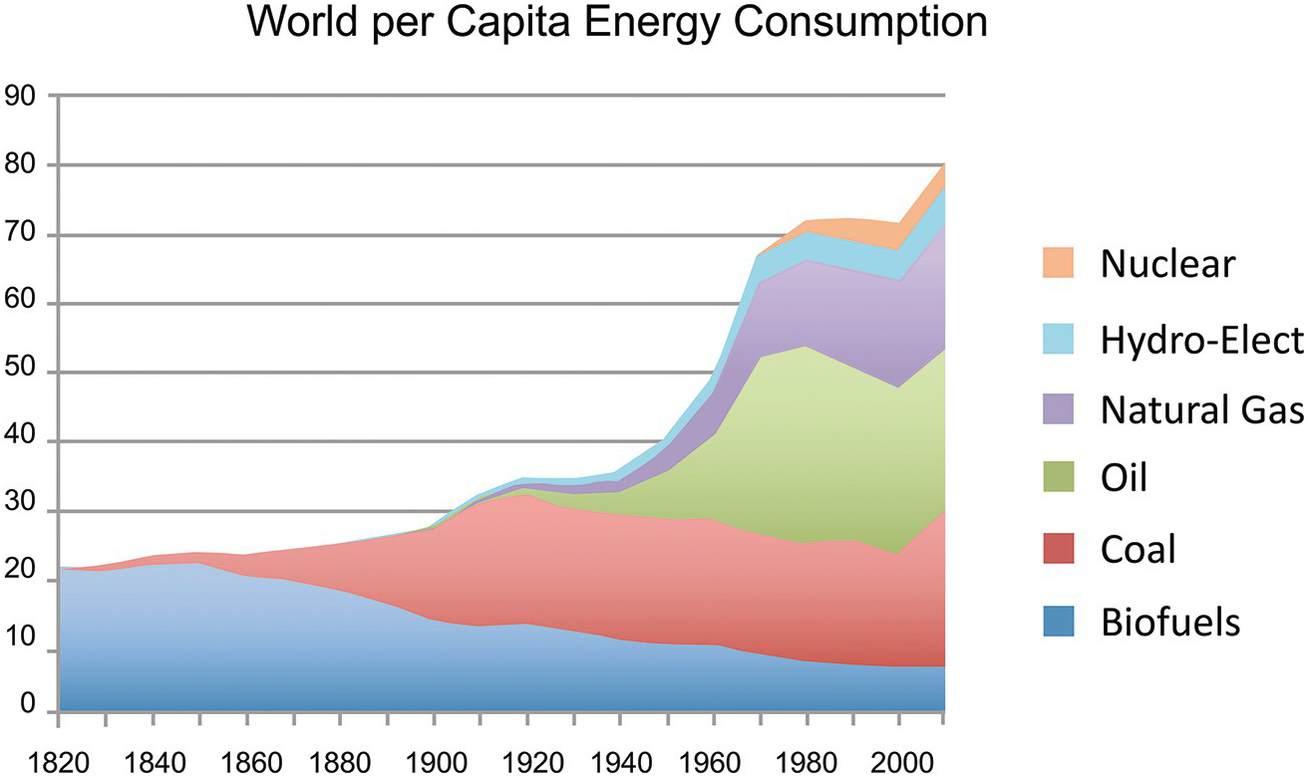

But as the overall structure of the European system began to fray at the edges, the massive introduction of fossil energy as a resource and the concomitant Industrial Revolution reestablished the information gradient across the European empires and the value gradient between the colonies and the heartland. The resulting shift was profound (Figure 15.1). It gave European dominance a new lease of life, but at the expense of major changes. From a zone in which internal consumption of high-value goods imported from elsewhere generated most of the wealth, Europe became the mass-producer of a wide range of goods for export to the rest of the world.

Figure 15.1 With the discovery and use of fossil energy and the Industrial Revolution that followed, our global energy consumption exploded. At present, whereas humans need about 100 Wh for their biological functioning, US per capita energy use is around 11,000 Wh. At present, per capita, an average North American uses 1.5 times the energy of an average Frenchman, 2.2 times the per capita energy of Japan or Britain, 2.6 times the energy of a German, 5 times the energy of a South African, 10 times the energy of a Chinese person.

To maintain this system, it had to create wealth in the periphery that would allow the local populations to acquire European goods. It did so by creating in the colonies large-scale production systems for raw materials that were transformed in Europe into products sold to the same colonies. Thus, the status of these colonies changed – from producers of goods that had relatively little value locally but high value in Europe, to areas mass-producing low value goods for export to Europe and serving as markets for low-value European products. Maintaining this system required improved political control over the colonies concerned, as it brought large numbers of local people into the system as low-paid labor.

In Europe, the invention of new technologies in both the core and the periphery created much wealth, but ultimately undermined the flow structure by disenfranchising large groups of people. Industrialization tied a large working class into (mechanized) production in low-paid, often dangerous, jobs that gave little satisfaction.3 Social movements were quick to emerge in the core (from 1848), and up to World War II. Countries that had not been part of the early flow structure aspired to create similar dynamics. The French thus occupied areas of Africa and Southeast Asia. Italy, Germany, Japan, and Belgium – born as nations in the late nineteenth century – had to satisfy themselves with the leftovers of the colonial banquet. This contributed to the causes of the two world wars: these countries sought expansion in Europe (and in Japan’s case in Asia) because it was denied them elsewhere.

Finally, between 1940 and 2019, the control over large parts of the world that Europe had thus far enjoyed spread to North America, Australia, Japan, South Africa, and more recently to Southeast Asia, China, and India. Europe and the United States are no longer in sole control of the information gradient responsible for the continued wealth creation, innovation, and aggregation of the World System, but have to compete with these other regions. The world has become multipolar.

Summary

I argue here that the European system has undergone three major transformations to date, dividing its history into four phases. In the first phase, after a predominantly flat, entropic, period (c. 800–1000 CE), in which whatever flow structures there were occurred essentially at the scale of individuals’, families’, or villages’ subsistence strategies, we see (roughly between 1000 and 1300) structures that involve information processing by larger (though still small) local units; most of these small rural principalities emerging in Southern Europe, but in northern Europe a few urban ones (the Hanseatic towns) emerged as well. Later in the period, several such rural flow structures were often subsumed under a larger one, leading to feudal hierarchies. But the hierarchical structure of the information networks structurally limited their opportunities of expansion (see van der Leeuw & McGlade Reference van der Leeuw, McGlade, van der Leeuw and McGlade1997).

The second phase (c. 1200–1400), was dominated by the death and later a new aggregation of the population in both old and new towns as a result of the Black Death, which caused innovation to take off. It drove a rapid expansion of the urban interactive sphere through long-distance trade and communication. The resulting urban networks that emerged from c. 1400 were independent of the rural lords and probably had a novel, heterarchical information processing structure (see van der Leeuw & McGlade Reference van der Leeuw, McGlade, van der Leeuw and McGlade1997), facilitating the growth of interactive groups and the systems’ adaptability. In the next two centuries, these cities drove the establishment of colonial trading networks.

But in the sixteenth century that dynamic led to a second tipping point inaugurating a third phase: the beginnings of the European World System, initiated by the discoveries of other continents by European seafarers. New resources were identified in faraway places and fed the accumulation of wealth that was going on. Between c. 1600 and c. 1800, urban and rural systems were forced to merge by rural rulers who needed to acquire in the towns the funds to increase control over their territories. This led to the formation of (systemically hybrid) states and the transformation of the urban trading networks into colonial exploitation systems. Toward the end of this period (c. 1800), these flow structures seemed to reach their limits: innovation stalled in the cities, and the energy and matter flows from the colonies were limited by the structure of their exploitation systems. Europe had reached a third tipping point.

At that point (c. 1800) a new technology inaugurated a fourth phase – the use of fossil fuel to drive steam engines, lifting the energy constraint that had limited the potential of all western societies thus far. The innumerable innovations that followed enabled transformation of the European production system at all levels, rapidly increasing the information-processing and value gradients across the European empires again. Girard (Reference Girard1990) outlines how in that process, the term “innovation” changed its value, from something to be ignored or even despised, to the ultimate goal of our societies. As part of this process, our societies became so dependent on innovation that one may currently speak of an addiction that resembles a Ponzi scheme in that innovation has to happen faster and faster to keep the flow structure intact.

I insist on emphasizing two lessons learned from this history. First, wealth discrepancy may well be a societal counterpart to the environmental planetary boundaries that were highlighted in the paper by Rockström et al. (2009), as it seems that wealth discrepancies were at their widest just before the three major transitions in European history: the Black Death, the discovery of the rest of the world, and the Industrial Revolution.

Secondly, in hindsight the progression from the agricultural societies of the Middle Ages to the trading empires of the early modern world, and ultimately to the industrial and post-industrial economies of the last century or so may seem inevitable, but like any story, or history, it is in effect a post-facto narrative that reduces the dimensionality and complexity of what really happened.

From the ex-ante perspective that we are introducing here, at each of the three transition moments mentioned European societies could potentially have engaged in different trajectories, and this continues to be true for the present. Rome could for example theoretically have followed a different trajectory in the second century CE. History is not inevitable. There are times when processes dominated by strong drivers make change very unlikely, and there are moments when unexpected events or people can indeed change the course of history. It is the thrust of this book that we seem currently to be living a moment in history that opens a window of opportunity for the world to change. Hence there are choices to be made. Making those choices requires that as individuals and as a society we retake responsibility for our collective future, instead of leaving that responsibility to a small group of people who are currently, knowingly or not, misusing it.

Another important thing to conclude from all this is that globalization is not new at all, but has been going on since the sixteenth century. We need to take this fact into account when we think and act in the present. In effect, all that has happened is that we have entered a new stage of globalization; a stage that has interesting parallels with the sixteenth- to eighteenth- century colonization of large parts of the world – in that trade was enabled to expand as the political structure of Europe was very fragmented, allowing nascent trade organizations such as the Dutch and English West and East Indies companies to drive the spread of European ideas worldwide. In some ways, states latched onto these trade organizations to bring wealth into their coffers, for example by issuing permits to pirate vessels of enemy nations.

The Changing Roles of Government and Business

I would like to use this section to look more closely (but still in general terms) at the current phase of globalization from a historical perspective, with an emphasis on the respective roles of government and business. As we have seen, beginning in around 1800, the introduction of ways to massively use fossil energy, and the Industrial Revolution it enabled, changed both the economy of European countries and of their colonies. In a nutshell, as the European countries developed industrial mechanization, they also changed their interaction with their colonies, developing governance, plantations, and markets for European products.

Thus, until around 1800 there was an enterprise-driven low-volume but high value flow from the colonies to Europe, with very little in the way of organizational and information processing capacity flowing toward the colonies. After that date, the flow structure involved national administrations, which triggered a much more important flow of organization and information-processing toward the colonies, transforming the latter into western-administered and -run territories owing to an influx of western-educated men and women.

This system essentially continued and expanded during all of the nineteenth and the first half of the twentieth century, facilitated by the discovery of oil, the spread of electricity, and the invention of new modes of transportation (railroads, steam- and later oil-powered shipping, aviation, etc.) and communication (mail, telegraph, telephone, telex), facilitating larger and larger, faster and faster flows of information between the European countries and their colonies, and thus slowly integrating those colonies into the overall information-processing apparatus of their home countries. It is important to be aware that during the nineteenth century and up to World War II, in the colonies business and government worked together and kept each other in balance.

Decolonization began in the late nineteenth century and the first half of the twentieth century in Latin America, and followed in the forty years after World War II in very large parts of Southeast Asia and Africa. It severed the political link between European countries and their colonies, and cut the ex-colonies off from the information flow that had until then “organized” them. But it did not stop the trade flows between the European countries and their ex-colonies. It merely separated (once more) the governmental and the commercial domains, allowing business a freer hand in the new overseas nations after their independence, while governance was still in its infancy.

At the same time, the USA had achieved military and political dominance over much of the world, and because of its liberal philosophy facilitated, if not encouraged, the concentration of economic power in private hands. The so-called Pax Americana of the second half of the twentieth century enabled corporations – which equaled the economies of many countries in size – to dominate industrial production, trade, and communication, slowly leading to a situation in which they became as powerful, or more so, than most countries. In the process, some countries managed to organize themselves to achieve a rapid rise in wealth and economic power (Germany, Japan, Korea, later China and other countries in the BRICS grouping – Brazil, Russia, India, South Africa), often initiated by government-sponsored, large industrial and business clusters that captured markets owing to the initially much lower salaries than those paid in Europe and the USA. The world thus evolved into a multipolar communication and information flow structure.

For the moment, the main lesson to take away from this brief and superficial history is that we have not only seen balance of power shifts between countries, but also a recurring shift in the balance of power between governments and business, since the Reagan and Thatcher era (the early 1980s) to the advantage of business and finance. That development has also hugely increased the value and wealth differentials between the core and the periphery of the system (the haves and the have-nots), as recently brought to everyone’s attention by Piketty (Reference Piketty, Saez and Stantcheva2013), and thereby reduced the chances that outsiders could become insiders, creating an extraction-to-waste economy (in terms of raw materials, but also human capital) that is close to reaching (or has reached) its limits in the sense that our planet can no longer deal with it.

Because of the territorial limitations of governance, this system’s spread around the globe has enabled, but has also been driven by, the growth of large multinational corporations. The impact of these corporations outside the core of the western world has, slowly but surely, over the last century or so, incorporated regions that were culturally and socially fundamentally different into that extraction-to-waste economy and made that economy truly global – driving individuals, groups, and countries to gradually adopt mindsets, activities, and institutions that are compatible with its underpinning an urban and wealth-driven logic. In the last thirty years, this process has accelerated, and is now reaching the conurbations of China, Indonesia, India, and other countries.

Crises of the Twentieth Century

As part of this process, a number of fields of tension were generated that ultimately caused major crises. The first such to hit western society in the twentieth century was World War I. As we all know by now, it was triggered by a seemingly minor event, the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand, which occurred after a spate of similar assassinations of princes and high nobility. It sparked a release of the tensions that had built up between four major societal configurations in Europe, the Austro-Hungarian, French, German, and British Empires, and inside these empires between rich and poor. The huge destruction it wrought in human and material capital reduced these tensions for a while. The next crisis, however, began not long thereafter in the financial domain, in 1929, being caused by the control of the financial markets by very few people, particularly in the USA. It triggered a major destruction of wealth, increased social tensions in the countries involved, and also coincided, in the USA, with major environmental destruction (the so-called dust bowl). The financial capital lost was not really reconstituted until the run-up to World War II, which was driven (in a revanchist way) by some of the same social tensions that had caused World War I, particularly in Germany.

After the war, a major restructuring of the western world was set in motion, entailing a new financial structure (Bretton Woods, the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank), a new attempt at a global political structure (the United Nations), a new military structure (the North Atlantic Treaty Organization and the Warsaw Pact, the Alliance of South-East Asian Nations, etc.), the opening up of trade flows worldwide (leading to the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade and the World Trade Organization, and more recently to regional customs unions such as the North American Free Trade Agreement, the European Union, and similar but less integrated regional pacts). Importantly but less visibly, this also caused a shift toward a material wealth model that exported the core of societal tensions from the western world to the rest of the Earth by using human and resource capital in the periphery to accumulate wealth in the western core of the system, thereby minimizing tensions in the western democracies. A large part of this development was driven by the technological innovations facilitated by the plentiful availability of fossil (and later to a limited extent nuclear) energy. These developments ultimately led to the current consumer society and helped create a period of relative social peace in the developed nations.

After about twenty years of rebuilding the parts of the world that had been destroyed by war, in the 1970s and 1980s unintended consequences of the new order, including the dismantling of the colonial empires, began to surface again in the west as well as elsewhere. In the financial domain, dealing with rapid growth in the financial system led to the abolition of the gold standard (1976), which was followed by the “big bang” (1986) that removed (national) policy constraints that had thus far kept the financial markets within bounds, in particular in the USA and Britain. The Reagan and Thatcher regimes contributed to the collapse and the change of regimes in Russia (1989) and in some of the western periphery of the Russian Empire, in countries that had been weakened by the unintended consequences of their communist philosophy of management. In a number of ex-colonies, a revolution of rising expectations led to profound regime changes (e.g., in Indonesia, India, Pakistan, Zimbabwe, and many others; much later South Africa) to the advantage of (small groups among) the original inhabitants.

Underneath all of this, and surfacing particularly from the 1980s onwards, globalization was a major driver of the process, on the one hand increasing trade and the wealth of the core as well as reducing regional risks by subsuming them under global ones, but on the other hand leading to more dependencies between different parts of the world, and thus increasing the chances that minor events in one place could have major consequences for the world system as a whole (the ‘butterfly’ effect).

Conclusion

From our information-processing dissipative flow perspective, globalization is the latest stage in a process driven by an imbalance between our global societies’ capacities to process energetic and material resources on the one hand and information on the other. Information-processing needs over time brought more and more people together, and this required more and more resources. In this process, the information-processing capacity of growing communities increased sublinearly with the number of people owing to the limitations of human short-term working memory and inefficiencies in alignment and communication. But the material and energetic flows increased at first linearly with the number of people, and later maybe even geometrically when the growth of group sizes required increasing investment in infrastructure. As a result, the resource needs of western society drove it to expand its extraction networks across the globe, but without concomitantly expanding the dimensionality of its information processing toolkit. Over an ever-widening area, the globe was exploited in the western way, disregarding the many dimensions of local information processing that were related to local customs, environments, challenges, solutions, and values. Integrating these was beyond the capacity of western societies’ information processing, and thus globalization proceeded on an increasingly narrow dimensional basis, around wealth, ever since the discovery and harnessing of fossil energy in the nineteenth century (coal) and twentieth century (oil and later gas) facilitated innovation and an expansion of the western value space. This expansion was based on an elaboration of the same set of core dimensions that had governed the west’s information processing earlier.

The forcible geographical expansion of western information processing was not able to integrate the very high number of different dimensions inherent in the different ways in which non-western populations processed their information. The western flow structure therefore spread across the world, maintaining its own ways of processing information, facilitated by a few shared languages worldwide: English, Spanish, and French. This rapidly widened the gap, worldwide, between the dominant (western) information processing system and the cultures and environments it confronted, and thus generated a rapidly growing tension between the available information processing and the kind of information processing that would have optimized local (natural and human) resource use, leading to an explosion of unintended and unanticipated consequences that ultimately caused a series of crises (which in my opinion will continue to occur with increasing frequency and amplitude).

Of course, this tension will impact differentially on the vulnerability, resilience, and adaptability of different scales of the system (Young et al. 2006). But the expansion of the western information-processing system will increasingly undermine societal diversity and the diversity in thought and action that has until now characterized the different cultures on Earth and acted as a buffer against their hyper-connectedness. And finally, I think it will limit, if not render impossible, the expansion of the value space that I discuss in Chapter 16.

It is my contention that these dynamics have not sufficiently been explored, in part because they have been looked at from a national or corporate perspective, in which expansion was viewed as an advantage because it increased financial and economic flows and values.4 In order to explore them properly, it is essential to take a global and holistic perspective, to develop a “Global Systems Science” that looks at the causes and effects of globalization at the scale at which the phenomenon happens, rather than only looking at the advantages of globalization for individual countries and companies in competition.

As I outline in Chapter 18, in the current age of big data gathering, the information needed for such an approach is fundamental to the continued existence of our societies, and its importance exceeds that of any national interests. We are beginning to see such collection, but it is essentially in private hands (of Google, Facebook, Tencent, and others like them), while governments do not really seem able to compete on the same scale because (apart from the superpowers who are mainly collecting it for defensive and military purposes) they still maintain a national perspective.