The study of the natural history of major depressive episodes and its determinants is essential to understanding the nature of the illness and may guide the development of more effective treatment strategies (Reference JuddJudd, 1997). Duration of major depressive episodes has been found to vary widely, with median durations between 3 months and 12 months and rates of chronicity (duration 24 months or more) between 10% and 30% (Keller et al, Reference Keller, Shapire and Lavori1982, Reference Keller, Lavori and Mueller1992; Reference Angst, Helgason and DalyAngst, 1988; Reference Coryell, Akiskal and LeonCoryell et al, 1994; Reference Angst and PreisigAngst & Preisig, 1995; Reference Mueller, Keller and LeonMueller et al, 1996; Reference Solomon, Keller and LeonSolomon et al, 1997; Reference Furukawa, Kiturama and TakahashiFurukawa et al, 2000). The variation may be explained by different definitions of recovery. Moreover, the previous studies were subject to two kinds of bias. Lead-time bias arises because participants with depression were not recruited at a similar point in time in the course of the disorder; mostly, prevalent cases were included. Referral filter bias arises because selected populations of in- or out-patients with depression were studied. It is expected that both kinds of bias lead to an overrepresentation of chronic cases (Reference Cohen and CohenCohen & Cohen, 1984). To avoid these sources of bias, the duration of newly originated major derpessive episodes should be studied in people with depression selected from the general population. In a 13- to 15-year follow-up of the Baltimore site of the Epidemiologic Catchment Area study, a median duration of major depressive episodes of 8-12 weeks was found (Reference Eaton, Anthony and GalloEaton et al, 1997). The Life Chart Interview (LCI) (Reference Lyketsos, Nestadt and CwiLyketsos et al, 1994) was used to determine the onset and duration of major depressive episodes. Owing to the long follow-up period, dating of episodes was global and limited to 1 year. With regard to determinants of episode duration, living without a partner (Reference Mueller, Keller and LeonMueller et al, 1996), comorbid dysthymia (Reference Keller, Shapire and LavoriKeller et al, 1982) and severity of depression (Reference Keller, Lavori and MuellerKeller et al, 1992; Reference Mueller, Keller and LeonMueller et al, 1996; Reference Furukawa, Kiturama and TakahashiFurukawa et al, 2000) have been found to predict longer duration of episode.

The primary aims of our study were (a) to investigate duration of major depressive episodes in detail over a period of 2 years in a cohort with newly originated episodes (first or recurrent) from the general population, and (b) to study potential socio-demographic and clinical determinants of episode duration. A secondary aim was to assess the effect of referral filter bias (by comparing episode duration across levels of care).

METHOD

Sampling

Data were derived from The Netherlands Mental Health Survey and Incidence Study (NEMESIS). Methods are described elsewhere (Reference Bijl, Van Zessen and RavelliBijl et al, 1998; Reference Vollebergh, Iedema and BijlVollebergh et al, 2001). Briefly, NEMESIS is a prospective psychiatric epidemiological survey in the Dutch adult general population (aged 18-64 years) with three waves, in 1996 (T0), 1997 (T1) and 1999 (T2). It is based on a multi-stage, stratified, random sampling procedure. One respondent was randomly chosen in each selected household. Interviewers made up to 10 telephone calls or visits to an address at different times of the day and days of the week to make contact. To optimise response and offset any seasonal influences, the initial fieldwork extended from February to December 1996. In the first wave, sufficient data were gathered on 7076 persons, a response rate of 69.7%. At T1, the second wave, 1458 respondents (20.6%) were lost to attrition, and at T2 a further 822 (14.6%) were lost. Altogether, 4796 respondents were interviewed at all three waves.

Psychopathology over the preceding 12-month period did not have a strong impact on attrition: at T1 agoraphobia (odds ratio 1.96) and social phobia (OR 1.37), and at T2 major depression (OR 1.37), dysthymia (OR 1.80) and alcohol dependence (OR 1.83), adjusted for demographic factors, were associated with attrition (de Graaf et al, Reference de Graaf, Bijl and Smit2000a , Reference de Graaf, Bijl and Vollebergh b ).

Diagnostic instrument

Diagnoses of psychiatric disorders according to DSM—III—R (American Psychiatric Association, 1987) were based on the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI), version 1.1 (computerised version; Reference Smeets and DingemansSmeets & Dingemans, 1993). The CIDI is a structured interview developed by the World Health Organization (1990) and has been found to have acceptable interrater reliability and test—retest reliability for most diagnoses, including major depression (Reference WittchenWittchen, 1994). The following DSM—III—R diagnoses are recorded in the NEMESIS data-set: schizophrenia and other non-affective psychotic disorders; mood disorders (bipolar disorder, major depression, dysthymia); anxiety disorders (panic disorder, agoraphobia, simple phobia, social phobia, generalised anxiety disorder, obsessive—compulsive disorder); eating disorders; and psychoactive substance use disorders (alcohol or drug misuse and dependence, including use of sedatives, hypnotics and anxiolytics).

Study cohort

In order to include only newly originated episodes of major depression (first or recurrent cases), respondents with a diagnosis of 2-year prevalence of major depression at T2 but no diagnosis of 1-month prevalence at T1 were identified (n=273). Those diagnosed with bipolar disorder or a primary psychotic disorder were excluded.

Characteristics of participants with depression

Socio-demographic variables

Variables recorded at T0 were gender, age, educational attainment, cohabitation status and employment status.

Clinical factors

Based on the CIDI, the following information on the index episode of DSM—III—R major depression was obtained:

-

(a) severity of depression, categorised as mild—moderate v. severe with or without psychotic features according to DSM—III—R;

-

(b) first or recurrent episode according to the DSM—III—R;

-

(c) comorbidity with other DSM—III—R Axis I disorders. The comorbid disorders included were dysthymia, anxiety disorders and substance misuse or dependence. Psychiatric comorbidity was assessed without applying the hierarchical DSM rules.

Care utilisation

At T2 respondents were asked whether they had received help for mental problems within the past 24 months. We distinguished three levels of care:

-

(a) no care or exclusively informal care (e.g. from an alternative care provider, traditional healer, self-help group, telephone helpline or physiotherapist);

-

(b) primary care (general practitioner);

-

(d) mental health system care, including ambulatory mental health care (crisis care, or treatment given by a community mental health care institute, psychiatric out-patient clinic at a psychiatric or general hospital, alcohol and drugs counselling centre, psychiatrist, psychologist or psychotherapist in private practice, or psychiatric day care centre) and residential mental health care (in a psychiatric hospital, in-patient addiction clinic, psychiatric division of a general hospital, or sheltered accommodation).

Duration of major depressive episode

The duration of major depressive episodes was assessed retrospectively at T2, using the LCI (Reference Lyketsos, Nestadt and CwiLyketsos et al, 1994). To improve recall, we used memory cues such as personal events, birthdays or holidays in the past 2 years. Psychopathology was assessed over periods of 3 months, and for each period we recorded:

-

(a) duration of depressive symptoms — less than half, half, most, or whole of the 3-month period (for the analyses this was dichotomised as ‘6 weeks or less’ v. ‘more than 6 weeks’);

-

(b) severity of depressive symptoms — no or minimal severity, mild, moderate, severe, or very severe (dichotomised as ‘no or minimal severity’ v. ‘at least mild severity’).

Using this information on duration and severity, each 3-month period was scored as follows: i, no or minimal depressive symptoms; ii, at least mild severity with brief duration (≤ 6 weeks); iii, at least mild severity with longer duration (> 6 weeks). Recovery was defined as no or minimal depressive symptoms in a 3-month period, thereby extending the US National Institute for Mental Health (NIMH) definition of recovery (Reference Keller, Lavori and MuellerKeller et al, 1992) by 1 month. No distinction was made between remission and recovery (Reference Frank, Prien and JarretFrank et al, 1991) because the data did not allow for such precision. The duration of major depressive episodes was calculated by summing the 3-month periods until recovery. A single period ii or a period ii at the beginning or at the end of a major depressive episode was counted as 1.5 months; all other periods were counted as 3 months.

Because administration of the LCI was time-consuming and not relevant for the entire NEMESIS sample, and because interviewers were not aware of DSM—III—R diagnoses derived from the CIDI, the use of the LCI was made dependent on a probe question about whether the respondent had felt depressed for any period of more than 2 weeks since T0. In the study cohort, 23 (8.4%) of the 273 respondents did not respond affirmatively to the probe question. No significant differences were found between probe-question-positive responders and probe-question-negative responders on socio-demographic and clinical variables. The duration of major depressive episodes was determined for the first depressive episode recorded in the LCI. Ten respondents responded affirmatively to the probe question but reported no 3-month period of depressive symptoms; they were classified as having had a major depressive episode of brief duration, set arbitrarily at 0.5 month.

Analyses

Duration of major depressive episodes was calculated using survival analysis. The cumulative probability of recovery was estimated with the Kaplan—Meier product limit (Reference Hosmer and LemeshowHosmer & Lemeshow, 1999). This technique describes all respondents over time, either to the event of interest (in this case, recovery) or until they are lost to further follow-up (censoring). The effect of censored data is minimised by including all respondents who began the observation period, regardless of whether they finished it. Median survival time is the first recovery at which cumulative survival reaches 0.5 (50%) or less. Mean survival time is not the arithmetic mean but is equal to the area under the survival curve for the uncensored cases. We used the statistical package SPSS for Windows, version 8.0 (SPSS, 1998). Survival curves for cohorts selected from different levels of care were compared using the log rank test.

A stepwise Cox proportional hazards model was used to test the association between socio-demographic and clinical variables and duration of major depressive episodes. The hazard ratio is the increase (or decrease) in risk of the event of interest, incurred by the presence or absence of a variable.

RESULTS

Duration of major depressive episode

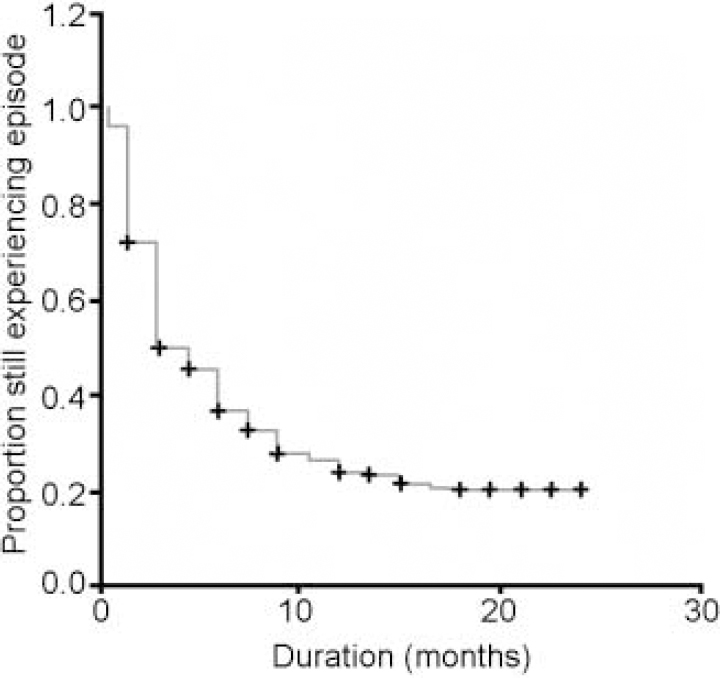

In 64 cases (25.6%) the follow-up period ended before recovery (censored cases). The survival curve is presented in Fig. 1. The median time to recovery was 3.0 months (95% CI 2.2-3.8) and the mean time to recovery with the upper limit of 24 months was 8.4 months (95% CI 7.3-9.5). Of the respondents, 50% (95% CI 44-56) recovered within 3 months; 63% (95% CI 57-69) within 6 months; 76% (95% CI 70-82) within 12 months, and 80% (95% CI 74-86) within 21 months. All cases with a duration greater than 21 months were censored cases, so cumulative survival at 24 months could not be calculated but was near 80%.

Fig. 1 Survival curve of a cohort (n=250) with newly originated (first or recurrent) major depressive episodes in the general population; +, censored cases.

Determinants of episode duration

More than two-thirds of the respondents were female. In 43.2% the index major depressive episode was a recurrent episode and comorbid dysthymia was infrequent (Table 1).

Table 1 Socio-demographic and clinical characteristics and care utilisation of a cohort (n=250) with newly originated major depressive episodes (first or recurrent) in the general population

| Variable | % |

|---|---|

| Socio-demographic variables | |

| Gender (female) | 66.8 |

| Age (years) | |

| 18-24 | 6.4 |

| 25-34 | 36.4 |

| 35-44 | 26.8 |

| 45-54 | 21.1 |

| 55-64 | 9.2 |

| Education | |

| Low | 3.6 |

| Medium | 37.6 |

| High | 31.2 |

| University | 27.6 |

| Living with partner (yes) | 63.6 |

| Paid employment (yes) | 70.0 |

| Clinical variables | |

| Severe depression | 30.4 |

| Recurrent depression | 43.2 |

| Comorbid dysthymia | 10.0 |

| Comorbid anxiety disorder | 34.0 |

| Comorbid substance misuse/dependence | 10.4 |

| Care utilisation | |

| No professional care | 32.8 |

| Primary care | 38.8 |

| MHS care | 28.4 |

None of the socio-demographic variables predicted the outcome. Of the clinical variables, the presence of comorbid dysthymia and severity of the index episode predicted longer episode duration, and the index episode being a recurrent episode predicted shorter episode duration (Table 2). Entering these three variables into a multivariate Cox regression model (method backwards) did not alter the hazard ratios substantially but the presence of comorbid dysthymia was only just statistically significant.

Table 2 Hazard ratios of determinants of episode duration (bivariate and multivariate models)

| Determinant | Bivariate model | Multivariate model | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard ratio | 95% CI | P | Hazard ratio | 95% CI | P | |

| Severe depression | 0.67 | 0.49-0.92 | 0.02 | 0.70 | 0.51-0.97 | 0.03 |

| Recurrent depression | 1.67 | 1.25-2.22 | <0.01 | 1.62 | 1.21-2.16 | <0.01 |

| Comorbid dysthymia | 0.47 | 0.26-0.84 | 0.01 | 0.55 | 0.30-1.00 | 0.05 |

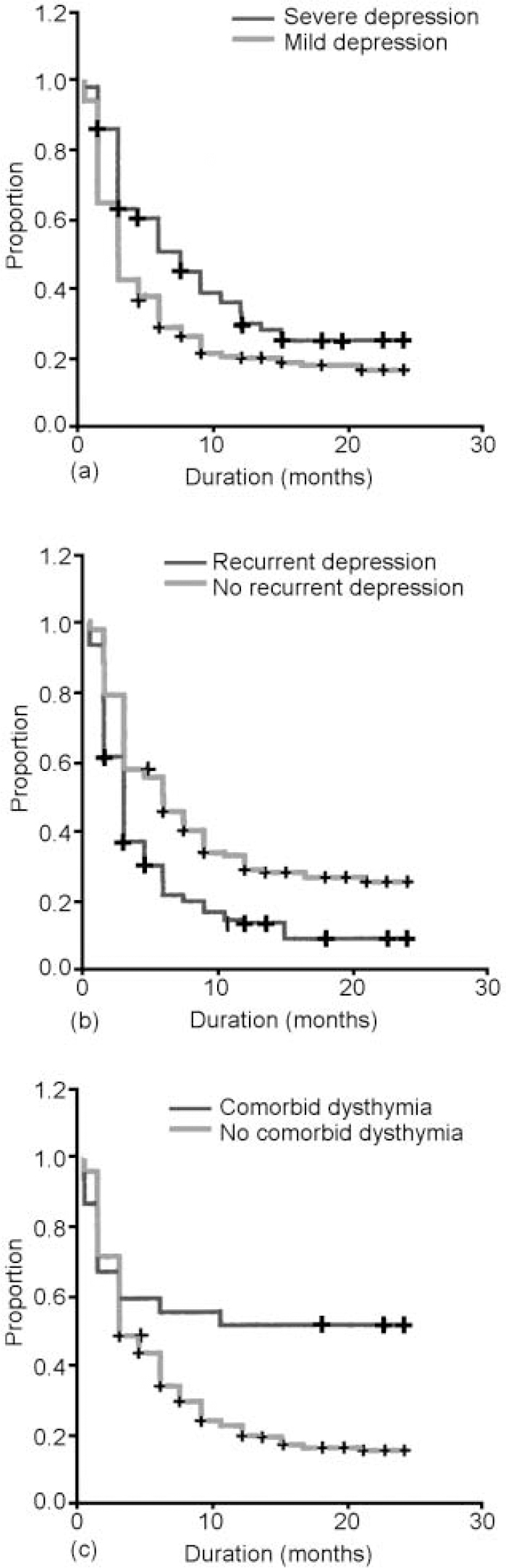

We also performed survival analyses for these three clinical variables (Fig. 2). Severe depression lengthens the median duration from 3.0 months (95% CI 2.5-3.5) to 7.5 months (95% CI 5.1-10.0) and the mean duration from 7.5 months (95% CI 6.2-8.8) to 10.5 months (95% CI 8.5-12.5). The presence of comorbid dysthymia lengthens the mean duration from 7.7 months (95% CI 6.6-8.8) to 13.7 months (95% CI 9.5-18.0). No median duration with comorbid dysthymia was determined, as cumulative survival did not reach 0.5 (50%). A recurrent episode shortens the median duration from 6.0 months (95% CI 4.3-7.7) to 3.0 months (95% CI 2.4-3.6) and the mean duration from 10.2 months (95% CI 8.6-11.8) to 6.1 months (95% CI 4.7-7.5).

Fig. 2 Survival curves of a cohort (n=250) with newly originated (first or recurrent) major depressive episodes in the general population influenced by clinical variables: (a) severity of depression; (b) recurrence of depression; (c) comorbid dysthymia; +, censored cases.

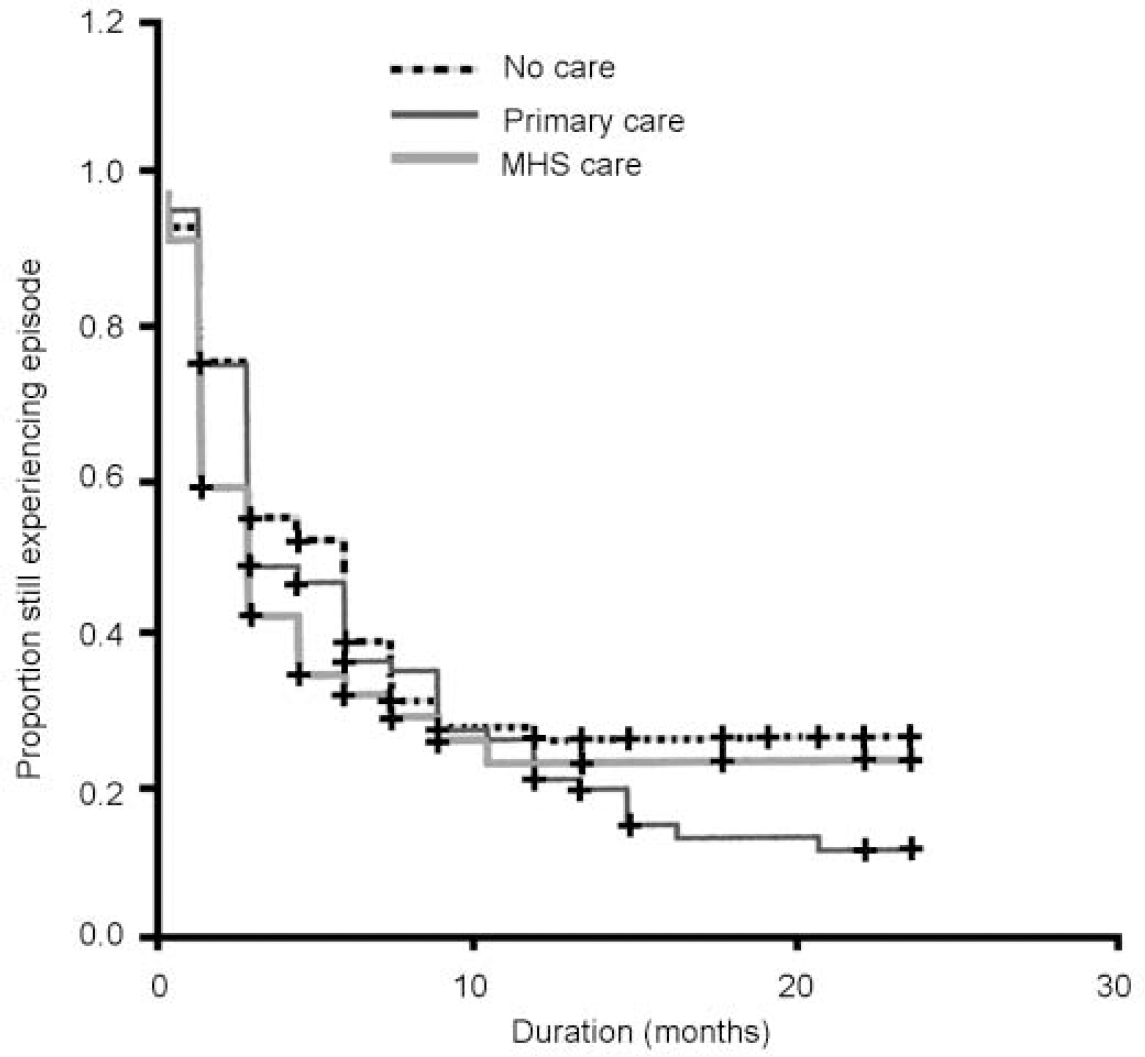

Duration of episode across different levels of care

Of all the respondents, 67.2% had received professional help for their mental problems within the past 24 months (Table 1). The survival curves for respondents stratified for different levels of care are shown in Fig. 3. In those without professional care the median duration of major depressive episodes was 3.0 months (95% CI 2.1-3.9) and the mean duration (with the upper limit of 24 months) was 8.1 months (95% CI 6.0-10.1). In respondents with only primary care the median duration of major depressive episodes was 4.5 months (95% CI 3.4-5.6) and the mean duration (with the upper limit of 24 months) was 7.8 months (95% CI 6.3-9.4). In those with mental health system care the median duration of major depressive episodes was 6.0 months (95% CI 3.9-8.1) and the mean duration (with the upper limit of 24 months) was 9.5 months (95% CI 3.9-8.1). Statistically, the differences in time to recovery in the different modalities of care were not significant (log rank 1.79, d.f.=2, P=0.41).

Fig. 3. Survival curves of a cohort (n=250) with newly originated (first or recurrent) major depressive episodes in the general population, according to whether they received mental health system (MHS) care, primary care or no professional care; +, censored cases.

DISCUSSION

This is the first detailed estimation of duration of major depressive episodes in the general population. We found a median duration of episodes of 3.0 months, which is in the lower range of duration found in clinical populations (Reference Keller, Shapire and LavoriKeller et al, 1982; Reference Angst, Helgason and DalyAngst, 1988; Reference Keller, Lavori and MuellerKeller et al, 1992; Reference Coryell, Akiskal and LeonCoryell et al, 1994; Reference Angst and PreisigAngst & Preisig, 1995; Reference Solomon, Keller and LeonSolomon et al, 1997; Reference Furukawa, Kiturama and TakahashiFurukawa et al, 2000) but in line with findings from the general population (Reference Eaton, Anthony and GalloEaton et al, 1997). Around 20% of those with depression had a chronic course (duration 24 months or more), which is similar to findings in clinical populations (Reference Keller, Shapire and LavoriKeller et al, 1982; Reference Angst, Helgason and DalyAngst, 1988; Reference Keller, Lavori and MuellerKeller et al, 1992; Reference Coryell, Akiskal and LeonCoryell et al, 1994; Reference Angst and PreisigAngst & Preisig, 1995; Reference Solomon, Keller and LeonSolomon et al, 1997; Reference Furukawa, Kiturama and TakahashiFurukawa et al, 2000). Determinants for persistence were similar to those in clinical populations. Clinical characteristics such as the severity of the index episode and the presence of comorbid dysthymia were predictors of a longer duration. Moreover, we found a shorter duration for recurrent episodes. This differs from the clinical population of the NIMH Collaborative Depression Study (Reference Solomon, Keller and LeonSolomon et al, 1997), in whom a similar duration of subsequent episodes was found. Shortening of duration with subsequent episodes might be a characteristic of the general population, as Eaton et al (Reference Eaton, Anthony and Gallo1997) also found.

The high rate of chronicity in the general population is the most conspicuous and unexpected finding of our study. In both treated and untreated people with depression the risk of a chronic course (duration 24 months or more) was considerable. Referral filter bias could not be demonstrated, as no association was found between level of care and episode duration. This is remarkable since we found level of care to be associated with more severe depression earlier (Reference Spijker, Bijl and De GraafSpijker et al, 2001). An explanation for the lack of association between episode duration and level of care could be that hospitalised patients with the most severe forms of psychopathology were probably underrepresented in NEMESIS.

The strength of our design is that it enabled us to study the duration of major depressive episodes in a cohort with newly originated episodes from the general population, avoiding lead time and referral filter bias. A limitation of the method employed is that duration of episodes was retrospectively assessed using the LCI. We believe, however, that this method of assessment of duration, with a combination of prospectively (CIDI) and retrospectively (LCI) obtained data, is the best in practice for general population surveys. The LCI proved practicable and useful (Reference Eaton, Anthony and GalloEaton et al, 1997) and the test—retest and interrater reliability of a similar life chart instrument was satisfactory (Reference Hunt and AndrewsHunt & Andrews, 1995). We recognise that the reliability of retrospectively assessed psychopathological data is questionable owing to recall problems, but this improves with shorter time intervals (Reference Lyketsos, Nestadt and CwiLyketsos et al, 1994), as in our design.

It was not possible using the LCI to determine whether a period with depressive complaints continuously met the DSM-III-R criteria for a major depressive episode. Therefore, in our analyses of duration we included both the major depressive episode and its preceding and succeeding sub-threshold depressive syndromes. Also, cases of comorbid dysthymia were included (10% of the respondents), somewhat increasing the chronicity rate. However, the inclusion of sub-threshold depressive syndromes and dysthymia reflects the naturalistic course of major depressive episodes better and may have more clinical relevance (Reference Judd, Akiskal and MaserJudd et al, 1998).

In conclusion, the natural course of major depressive episodes in the general population has remarkable characteristics: although half of those affected recovered rapidly (within 3 months), the rate of recovery slowed towards 12 months, virtually coming to a standstill after 12 months. Almost 20% of the participants with depression had not recovered at 24 months. These findings have important implications for prevention and treatment. Both in treated and in non- treated participants the risk of persistence was considerable. For untreated individuals it is essential that the depressive condition is detected and that treatment is offered. For treated individuals it is essential to identify lack of treatment response and adjust the therapy accordingly. The clinical characteristics of the index episode seem to be the best clue to identifying people at risk of non-recovery; but a more detailed risk profile is certainly needed.

CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS

-

▪ Half of those affected with major depressive episodes recovered within 3 months.

-

▪ The risk of chronicity (duration 24 months or more) was considerable and underlines the necessity of diagnosing and treating those at risk.

-

▪ Treated and untreated people affected with major depressive episodes share the same risk of chronicity.

LIMITATIONS

-

▪ In this study sample homeless people and long-term residents of care institutions were not represented, so the most serious and incapacitating forms of psychopathology were underrepresented, probably decreasing the reported chronicity rate.

-

▪ The course of major depressive episodes was not strictly assessed following DSM criteria, limiting the comparability of our results with other research.

-

▪ The follow-up period in this study was only 2 years and we have no data on the longer course of major depressive episodes in the general population.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.