In 1980, 2.4% of political science faculty members in the United States were African Americans. By 2010, this share had increased to a mere 5% (Fraga, Givens, and Pinderhughes Reference Fraga, Givens and Pinderhughes2011). Job-placement data from the American Political Science Association (APSA) indicate that only 4.2% of candidates in the job market in 2016–2017 identified as African American (Fraga, Givens, and Pinderhughes Reference Fraga, Givens and Pinderhughes2011). In 2017–2018, this percentage dropped to 3% (Jackson and Super Reference Jackson and Super2018). In other words, in the past four decades, the profession has made no significant progress in increasing the number of African American political science faculty in the American academy.

One reason for this outcome is well documented: a set of structural factors—from poor campus climate to inadequate mentoring—creates challenges for the recruitment and retention of faculty of color (Fraga, Givens, and Pinderhughes Reference Fraga, Givens and Pinderhughes2011, 39; Tormos-Aponte and Velez-Serrano Reference Tormos-Aponte and Velez-Serrano2020). Another less well-documented and studied challenge, however, consists of broadening the pipeline into the profession. In STEM disciplines, several programs have emerged in the past 40 years to address and rectify these obstacles. Their evaluation can be informative for understanding how we might broaden the pipeline into political science academia. In an analysis of the Meyerhoff Scholarship Program at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County—a program aimed at increasing the number of underrepresented minority students in STEM graduate education—scholars found that students who reported benefiting from mentors and university administrators were significantly more likely to subsequently enter a STEM PhD program. Similarly, in a mixed-methods analysis of the Summer Research Opportunities Program (SROP)—designed to offer underrepresented minorities a research experience with faculty members—scholars found that academic engagement, the opportunity to work with faculty, mentoring, and exposure to research were significant determinants of students subsequently entering a STEM field (DePass and Chubin Reference DePass and Chubin2008).

It is likely that similar factors would matter in political science: in an insightful interview with two Black political scientists—Professor Wendy Smooth and Professor Nadia Brown—Alexander-Floyd (Reference Alexander-Floyd2017) echoed the critical role that mentorship and community support have played. Both Brown and Smooth discovered the academic path almost fortuitously. Their initial interest in politics did not translate naturally into academia; instead, they both imagined going to law school in order to enter politics. They credit their pivot toward academia to conversations and experiences they had with mentors encountered in college. For Brown, one mentor suggested that she apply for the Ralph Bunche Summer Institute sponsored by APSA. In her own words, “That literally changed my life. I felt like I fit in. I felt like there was a word for people like me….It gave me the support system and a network of people who analyze race and politics, and gender and politics” (Alexander-Floyd Reference Alexander-Floyd2017, 100).

These personal experiences suggest that the same factors that predict minority access and retention in STEM fields might apply for political science. Indeed, students of color tend to experience fewer opportunities to discover and apply to political science PhD programs (Dickinson, Jackson, and Williams Reference Dickinson, Jackson and Williams2020). At Spelman College and Morehouse College—two of the country’s most highly ranked Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs)—an overwhelming majority of students in political science plan to attend law school or business school. Since 2011, Morehouse and Spelman have been the top two American Bar Association–compliant per-capita feeder schools for law school. Furthermore, between 2011 and 2016—when applications to law school decreased nationwide—Morehouse and Spelman experienced a much smaller percentage decrease compared to schools with lower proportions of Black and Hispanic bachelor’s-degree recipients (AccessLex Institute 2018).

This article describes one attempt to broaden the political science PhD pipeline: the UC San Diego–Spelman–Morehouse Summer Research Program (SRP). Now in its fifth year, this SRP invites six promising undergraduate students from two HBCUs to a summer research experience on the host campus. During the seven-week program, students are integrated into the host campus’s Summer Training Academy for Research Success (STARS)Footnote 1 and paired with a faculty mentor in the host university’s political science department to hone, expand, and deepen their academic research skills. This article outlines a possible model for broadening the pipeline in political science. We discuss the reasons why this model cannot be “scaled up” at our—or likely any—university. Rather, we hope that other institutions will develop similar programs.Footnote 2 In what follows, we describe the program, its challenges, the ways in which it has been successful, and our lessons learned in the past five years. Our goal is to offer one template that can be adopted easily by political science departments interested in either expanding the PhD pipeline or improving their own applicant and cohort diversity.

…in the past four decades, the profession has made no significant progress in increasing the number of African American political science faculty in the American academy.

This article describes one attempt to broaden the political science PhD pipeline: the UC San Diego–Spelman–Morehouse Summer Research Program (SRP). Now in its fifth year, this SRP invites six promising undergraduate students from two HBCUs to a summer research experience on the host campus.

THE UC SAN DIEGO–SPELMAN–MOREHOUSE SUMMER RESEARCH PROGRAM

Our program is a seven-week, research-intensive experience designed to introduce students to original research and a career for which a PhD is an appropriate degree. There are four major components to the program.

First, students are paired with faculty mentors who are on campus during the summer to participate in a research project, acquire “ownership” of some dimension of the project, and present their findings at the end of the seven weeks to an open house of faculty and graduate students at the host university. Student–faculty pairings are made on the basis of a student’s self-identified interests and the mentor’s summer availability and research-assistant needs. Students may not always work on the topics in which they are most interested; however, in all cases, we pair students with an appropriate mentor and projects in their general area of interest.

Students are expected to take ownership of some part of the faculty mentor’s research and to develop this in ways parallel to but not necessarily in the direction the mentors might otherwise undertake. For instance, students have used surveys already fielded by the faculty mentor to examine a new set of relationships or to delve deeper into particular questions that are outside of the mentor’s primary focus. It is essential to the experience, in our view, that students take responsibility for an identifiable piece of the research project through which they can develop their “own” research.

Students are expected to meet at least once weekly with their faculty mentor. Faculty mentors are responsible for supervising their student’s research and, when necessary, providing tutorials on the subject matter, explaining how the student’s research fits into the larger research project and the discipline in general, and guiding them through the research project. This type of mentorship is immensely valuable to students and, if the initial match is successful, does not represent an unreasonable time commitment on the part of faculty mentors. Almost all of our mentors reported spending approximately 1.5 to 3 hours a week advising their student. Mentors were divided as to whether the time commitment was the same as or more than mentoring an undergraduate research assistant. The success of the program requires mentors who believe in the larger objective of diversifying the academy and are willing to invest the time necessary to contribute meaningfully to the goal.

On the last day of the program, students present their research projects—in the form of an APSA-style panel—to the available faculty and graduate students in the department. These presentations are the only “product” of the summer program; however, we have found that students gain confidence and inspiration when their achievements are recognized by faculty mentors and experts.

In the most successful cases, students maintain their relationship with their host-university mentor throughout their academic experience. Some use their research as the foundation for their senior theses. Although these theses then are written under the supervision of faculty at the students’ home institution, host-university advisors often remain involved: five of the seven reporting faculty mentors stated that they have maintained contact with their student after the program concluded. In one case, the relationship continued and even included a faculty member not originally involved as a mentor, resulting in a student–faculty coauthored paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Society for Political Methodology.

Second, the host department offers students a research “bootcamp” during the first weeks of the program to strengthen their research skills in general and to ensure that they have the more-specific tools needed to successfully pursue their research project. We ask host-university faculty to lead sessions on scientific inquiry, research design, and statistical reasoning. Students often have some background in research methods from prior coursework at their HBCU, and not everyone engages in research that requires statistical methods. However, the bootcamp offers a second way to reinforce critical research skills that benefit students regardless of what course they pursue.

Third, each subfield within the department hosts a lunch workshop for the students, during which graduate students in the subfield present their work. The purpose of these workshops is to excite the students’ interests in the subfield and, in turn, introduce them to what PhD-level research entails. In exit interviews, students have reported these workshops as one of their favorite aspects of the program.

Fourth, the students participate in a campus-wide STARS program that prepares those from underrepresented communities to apply to graduate school. Most STARS students are in the STEM fields; however, the Office of Graduate Affairs at the host university has expressed interest in expanding the program to the social sciences. The SRP is consistent with this priority and, with a similar effort in sociology, represents one of the few social science options available to STARS participants. The STARS schedule includes a GRE preparation course, seminars on academic careers, and workshops on applying for graduate school and funding.

Importantly for us, STARS provides the logistics and financial support that make the SRP feasible. STARS houses students in on-campus dormitories, arranges and pays for roundtrip transportation to the host city, and provides a $4,000 summer stipend. Additionally, STARS hires graduate-student advocates, who are part-time program assistants that provide critical mentorship and support to the students. In our experience, the STARS advocate role is so critical to the success of the program that we supplement this position through department funds to make it a part-time (50%) position for two summer months. Doing so has paid off tremendously; not only do our graduate students enthusiastically want to participate and apply to be the STARS advocate for the SRP, this position also has provided critical support throughout the summer. The STARS advocate, for example, welcomes the students when they arrive and ensures that they understand the demands of the STARS and SRP schedules. The STARS advocate also complements the methods bootcamp with additional sessions on the use of Stata, R, and the basics of data entry and manipulation. On a weekly basis, the STARS advocate holds office hours with each student to check in with them on professional and personal levels. In the final week of the program, the STARS advocate works closely with them to help prepare their final presentation. In other words, the STARS advocate provides much-needed hands-on mentorship that we know to be critical for student success, allowing the faculty mentor–student relationship to focus on overall advising.

LESSONS LEARNED

In the hope that other institutions may learn from our experience, we share several lessons distilled from five years of running the SRP. The need to broaden the pipeline remains acute. We feel no need to “patent” our program; neither do we believe we are in competition with other institutions. This is an effort in which we believe all should engage to the fullest extent possible.

Lesson #1

Engagement is important at all levels. To succeed, leadership support and faculty engagement at home colleges are essential. Faculty must engage the program, encourage their students to apply, and build on that experience when the students return to their home campus. In the SRP, faculty partners at the home universities schedule a host-university faculty visit in February to introduce the program and ignite student interest. It also is the responsibility of these faculty partners to select the successful student applicants. For their part, participating faculty at the host university must commit to being available during the summer, and program directors must be engaged year-round in developing the program and raising the necessary funds. University leadership also must be engaged. Although STARS was created independently of our political science initiative, its support has been essential to its success; in turn, our success has justified the larger initiative.

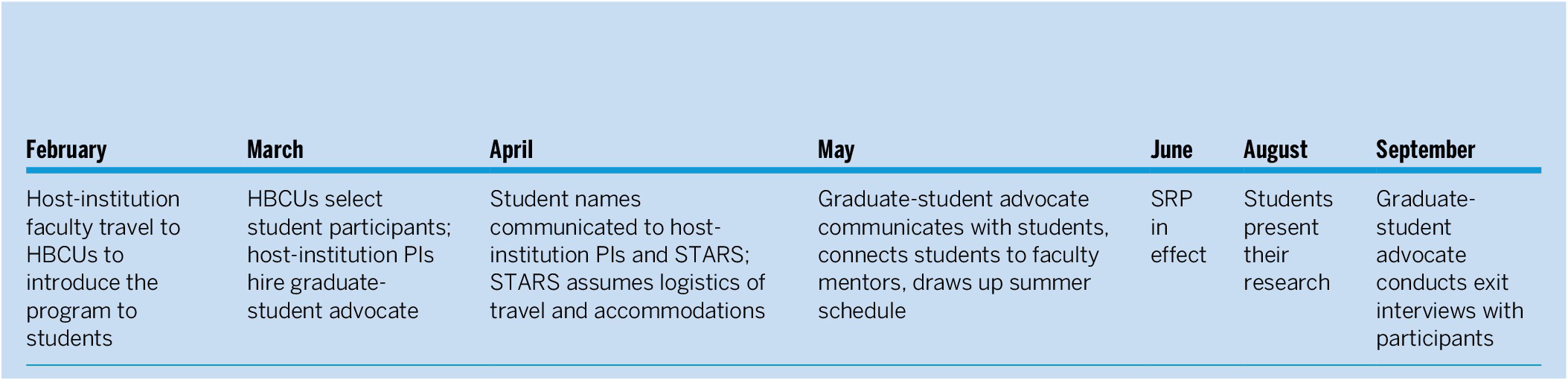

In addition, this institutional relationship requires continuing investment. From the beginning, the principal investigators (PIs) at the host institution have visited the HBCU home institutions every February to present the program in several different class sessions; to meet with students, faculty, and administrators; and to address issues in the program as they arise (table 1). These visits are essential not only for introducing the program to students and for cultivating interest but also for addressing the larger issues of possible career paths through and beyond the PhD. In turn, HBCU home institution PIs come to the host university on the last day of the summer program to attend student presentations and meet with host-university leadership. In particular, HBCU faculty and administrators want to ensure that any program they recommend to their students is appropriate and that the host university is committed to their success. “Being there” at all levels is essential to building the trust relationship between our institutions.

Table 1 Sample Timeline

These relationships were not preexisting: the PIs at the host institution reached out to the home-institution department chairs, and a collaborative relationship was built over time. The program easily could expand to include other HBCUs or even non-HBCUs. However, the constraint, as discussed in Lesson #2, lies in the availability of faculty mentors at host institutions rather than the availability of interested and willing collaborators at home institutions.

Lesson #2

Faculty commitment during the summer is necessary and limits the size of the program. Summer often is when faculty travel for research and pleasure, focus on writing, and generally recharge after teaching during the academic year. For the program to work, however, faculty mentors must be willing to meet frequently with students during the seven weeks and sometimes beyond. The mentoring relationship is sustainable if faculty are absent for a week or even two during the program; however, beyond that, the quality of the interaction is seriously degraded. Although host-university faculty are highly supportive of the program, not everyone can make this type of commitment. The host department presently has 44 core faculty members. In our experience, we easily can recruit about six faculty to mentor students during the summer, but we face constraints when we reach out to additional colleagues. We do not rely on the same colleagues every summer: this is not six committed faculty members who do all the work. Rather, faculty are eager to participate when it suits their summer schedule, and we have taken advantage of their willingness each year. At any institution, therefore, there are limits to the scale of a program. Likewise, we note that the constraints are with the host institution. Although Morehouse has struggled to find three applicants each summer, Spelman has always had a surfeit of students interested in the program. The limit comes from available faculty on the host-university side of the partnership. Thus, to scale up programs like ours to significantly broaden the pipeline entails encouraging additional institutions to adopt this template.

Lesson #3

Again, the research experience works best through the equivalent of research assistantships and with faculty mentors who are already running research programs that engage multiple graduate students, undergraduates, and even postdocs (provided those faculty mentors also remain personally engaged). Graduate students are eager to work with our STARS students to engage them in their dissertation research. Day-to-day involvement with graduate students working intensively on campus during the summer often has been more productive than working under the supervision of a faculty member who meets with a student on a weekly basis. “Labs” that already have developed the ability to break down large research undertakings into individual and manageable parts also are well suited to creating an engaging research experience for students who are on campus for only seven weeks. Individual mentoring is equally successful but typically requires more commitment from faculty supervisors. However, both models have constraints: a PI whose lab is operating during the summer but who is absent will have less to offer a student participant than a faculty member who is present to provide personal mentorship.

Conversely, in our first summer, we expected students to develop an idea for an original research project with their mentor’s advice and to conduct the research while in residence. We quickly realized that most students were not prepared for this type of opportunity and that seven weeks was clearly insufficient for this endeavor. Senior honor theses typically take at least a semester if not all year to mature; to expect something similar in seven weeks was clearly inappropriate. We retooled for subsequent years with more realistic expectations and successful experiences.

Lesson #4

The logistical support provided by the campus-wide STARS program is integral to the success of the summer research experience. Although we could arrange housing, transportation, and financing for the program, this burden is alleviated when professional staff handle these logistics within the larger program at the host university. The STARS graduate-student advocate hired through the campus program and supplemented by department funds also is an essential component of our success. In addition to consulting with students, the STARS advocate schedules the bootcamp sessions and field lunches—reserving rooms and ordering food, which relieves program directors of these responsibilities—and organize social opportunities. In the end-of-summer student surveys, the graduate-student advocate received consistently high praise as “incredibly friendly and helpful,” “dependable,” and showing “near-constant availability for answering questions, providing resources, or giving advice.” Infrastructure is costly but important. Any similar program could not be organized as easily by one or two faculty members; institutional and staff support is critical.

Lesson #5

Social interactions are important for informing students about graduate study and a potential life in the academy. We are clear in representing the purposes of the SRP. Participants know that we are “selling” the PhD and, in turn, the host university. At the same time, in our view, the most compelling conversations and introductions to research occur during informal social events. The STARS program organizes a few “outings” for all of the students in their program, including our students. Graduate students organize and host one or two parties during the summer for the students. The host PIs invite them to their homes for dinner with their faculty mentors and other guests. These informal interactions also act as another form of mentorship, giving the students a more concrete and comprehensive idea of what life as an academic is like.

Lesson #6

The host institution must undergird its commitment to diversity, equity, and inclusion with financial resources. Most universities claim to share the goals of diversity and inclusion. Programs such as the SRP require funds and institutional support. In the first four years, our program benefited from financial support from the office of graduate affairs (which donated six STARS spots and one graduate-student advocate spot to our department each year), the dean of social sciences, and the political science department (which augmented the graduate-student advocate role). Most recently, the host PIs successfully applied for a grant from the UC Office of the President to continue supporting the program. Without this financial support, the program could not exist. More precisely, we estimate the cost of the program to range from $8,000 to $14,000 per student. The lower-bound cost includes student stipend, room and board, student travel to and from the host institution, a faculty mentor research allocation of $500, and participation in the STARS summer program workshops (e.g., GRE preparation courses, orientation, and activities). The upper-bound cost expands to include one month of summer salary for one PI, support for a graduate-student coordinator, a recruiting trip by the host institution PIs to the home institutions to present the program, and an invitation to the home-institution PIs to attend the end-of-summer conference presentations.

MEASURING SUCCESS

We propose two measures for evaluating the UC San Diego–Spelman–Morehouse SRP. First, we followed up with all 22 participants in our program and tracked their current career choices. Of the 14 participants who have graduated, three are now enrolled in our PhD program and six are pursuing or have completed a masters or law degree. A significant number—eight students—have not yet graduated; this is because our program is only five years old and has accommodated students at varying levels of progress in their program, from rising sophomores to rising seniors. Therefore, although the numbers remain small, our ability to attract and enroll Black students is a significant accomplishment. Program enrollment at the host institution increased from zero to three Black graduate students—a significant increase for a program with an average cohort size of 13.

Second, we ask our STARS graduate-student advocate to survey student participants at the end of the summer. The surveys allow us to anonymously collect feedback on the most and least successful parts of the program. We collected responses for all 14 participants from 2016 to 2018, drawing three additional lessons from the results. First, communication and coordination between our program and the larger STARS program has had to improve over time. Specifically, the STARS program was created for students in STEM disciplines; however, after the first summer, feedback indicated that some STARS meetings were irrelevant or inappropriate for our students. We have since communicated with the STARS organizers to better align their requirements with our students’ needs. Second, our subfield workshops are popular with participating students, who enjoy learning about graduate-student and faculty research projects. As one student wrote in the survey, “I thought the field lunches were a really interesting part of the program because the talks gave insight into how research is really performed at the graduate level.” At the same time, the format has been more successful as an informal discussion and Q&A rather than as a presentation. Our understanding is that students want more mentoring in the form of dialogue.

Third, by all observable measures, our program is a success. Participants learn what it means to be a graduate student in a PhD program: all responded affirmatively to the question, “Do you feel that you have a good idea of what a PhD in political science entails?” Many expressed interest in pursuing a PhD in political science. When asked “How likely are you to apply for a PhD in political science?,” nine participants answered “Likely,” three answered “Somewhat likely,” and two answered “Unlikely.”Footnote 3 Our primary objective was to expand the pipeline; it seems we have made a good start.

Third, by all observable measures, our program is a success. Participants learn what it means to be a graduate student in a PhD program: all responded affirmatively to the question, “Do you feel that you have a good idea of what a PhD in political science entails?” Many expressed interest in pursuing a PhD in political science.

CONCLUSION

The US academy today is overwhelmingly white, with only 8% to 9% of full-time science and engineering faculty as underrepresented minorities (DePass and Chubin Reference DePass and Chubin2008, 6). A significant number of programs and scholarships have been developed in the past 40 years to rectify this imbalance, but these initiatives are focused predominantly on STEM fields. This article introduces an effort to do the same in political science and presents from our experience a template for adoption at other institutions. Our lessons draw from existing research that evaluates similar programs in STEM disciplines as well as from our five years of implementation. Nevertheless, it is worth noting that structural factors beyond the scope of this initiative contribute to the persistence of underrepresentation of minorities in academia. Our effort endeavors to improve equity, diversity, and inclusion in the political science academe within the scope of what individual departments and universities can achieve. By doing so, we hope to empower other academic actors to do the same.