Small towns on the research agenda: Vera Bácskai's contribution

In order to understand Vera Bácskai's oeuvre as an urban historian, we should remember that she started out as a medievalist. She earned a degree in History at the University of Leningrad under the direction of Professor Alexandra D. Lublinskaya, with a strong orientation towards social and economic history, and with a thorough training in palaeography and the use of archival materials. She wrote her first major work, a dissertation for the so-called Candidate of Sciences degree, on the market towns of medieval Hungary, publishing it in 1965 in a deceptively modest-looking slim monograph, long before small towns attracted the serious attention of urban historians.Footnote 1 The medieval part of her lucid synthesis of pre-modern Hungarian urbanization published in 2002 also strongly benefits from first-hand research experience in her early career.Footnote 2

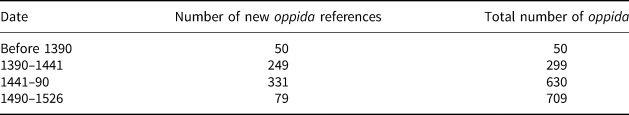

The strong presence of market towns in the urban network of medieval Hungary had been noticed by historical scholarship as early as the late nineteenth century. At that time, the main distinctive criterion was to find the term oppidum in the sources that was used to distinguish these settlements from cities and towns (civitas) on the one hand, and villages (villa, possessio) on the other. A cadastre compiled to reconstruct the settlement network in c. 1490 identified some 850 such entities,Footnote 3 an alarmingly high number, making it problematic to consider them a uniform group and leaving the question of their contribution to urbanization entirely open (see Table 1). Attempts at answering this question in the inter-war period and the 1950s tended to emphasize the tenant peasant status of their inhabitants and the limited presence of craft-based production, considering them as dead-end roads diverting resources from the development of ‘real’ cities.Footnote 4 Vera Bácskai's in-depth research in the early 1960s, revealing the presence of inter-related branches of market-oriented production and commodity exchange, brought a fresh approach and an emphasis on functional criteria over the legal-constitutional aspects in the assessment of the oppida. Her strongest contribution was pointing out the significance of specialized agrarian production, particularly winegrowing and cattle-breeding, that tied many of the oppida into networks of regional and even long-distance trade. Furthermore, markets and merchants in the oppida efficiently channelled the surplus produced in the villages of their catchment area into broader commercial networks, thus fulfilling central functions and expanding the limits of commodity production.Footnote 5 These innovative conclusions are still valid and often cited in modern scholarship.

Table 1. Number of localities referred to as oppidum in the Kingdom of Hungary up to 1526

Source: Bácskai, Városok Magyarországon, 31, originally presented as a graph in Bácskai, Magyar mezővárosok, 16.

Vera Bácskai's monograph was soon followed by increased attention to social and topographical aspects by Erik Fügedi, the first scholar to point out the importance of oppida as estate centres, as well as their inevitable emergence as secondary or tertiary centres in the settlement hierarchy for the distribution of commercial goods. He also argued that the term oppidum changed its meaning around the middle of the fifteenth century, from denoting town-like although unfortified settlements to meaning privileged settlements under seigneurial jurisdiction, moving from a morphological to a constitutional sense.Footnote 6 The other contribution in the early 1970s was András Kubinyi's inspiring attempt at network analysis avant la lettre to investigate the potential of market towns to send students to universities outside Hungary. He used the number of students hailing from a settlement as a proxy for defining the level of its centrality.Footnote 7 Almost two decades later, Kubinyi expanded his set of criteria to nine further indicators of centrality that reflect the roles performed by these settlements as manorial, judiciary, ecclesiastic, financial, commercial or administrative centres, quantifying each on a scale of 1 to 6. Kubinyi then added up the scores and ranked the oppida into seven categories.Footnote 8 This classification enabled him to distinguish at one end the upper echelon of settlements that fulfilled central functions, and were part of the country's urban network from biggish villages at the other. Kubinyi's work, halted by his death in 2007, has recently been completed by one of his disciples, Bálint Lakatos. Many of the criteria established by Kubinyi, such as the number of craft and merchant guilds, the frequency of weekly markets and annual fairs and the position of the settlement in the road network, are closely related to the social and economic aspects Vera Bácskai analysed. Thus, it is more than a coincidence that the 150 oppida that according to Kubinyi fulfilled significant urban functions accurately fit the estimate that Vera Bácskai offered in her 2002 overview.Footnote 9

Besides economic criteria, the urbanity of oppida was defined by the level of their municipal administration and civic autonomy. This research direction was also pioneered by Vera Bácskai in her 1971 study where she explicitly stated that in this respect as well oppida represented a transitional settlement type between villages and towns. Their bodies and methods of self-governance were modelled on those of cities, but their authority, particularly in judiciary matters, was limited by their landowners’ ambitions. The limits, however, were negotiable and context-dependent, and the documents resulting from these negotiations or conflicts offer valuable insight into power-relations and the dynamics of internal mobility.Footnote 10 More recent studies take into consideration the administration of property transactions, the overall level of administrative literacy and the constitution of the municipal council, as well as other representatives and officials. These all build on and expand Bácskai's results.Footnote 11

Meanwhile, from the 1980s, comparative urban history also discovered small towns as a worthy research agenda. Peter Clark's estimate convincingly justifies this: ‘In the high Middle Ages small towns with fewer than 2,000 inhabitants may have comprised over 90 per cent of all urban communities in Northern Europe, housing more than half of the urban population.’Footnote 12 These proportions were probably even higher in East Central Europe, given the very small number of large cities. The terminology of different local vernaculars reflects the variety of functions and perceptions of these settlements, including aspects such as their small size: mestečko, varošica or shtetl (in diminutive); their main economic function: Markt, Marktflecken, trgovište or târg, emphasizing the marketplace; or morphological character: palanka, a town lacking stone walls, and mezőváros (‘field town’), one without fortifications.Footnote 13 Vera Bácskai's familiarity with East Central Europe, enriched by her study on market centres and urban networks in Austria-Hungary in the early nineteenth century, made her a most appropriate contributor to Peter Clark's collected volume on Small Towns in Early Modern Europe. Her conclusion boldly points out the variation within the category of small towns, as well as their performance of certain roles that bigger cities played in the more urbanized parts of the continent. In her own words: ‘population level and urban functions were less interrelated in an underdeveloped urban context’.Footnote 14

One aspect of Hungarian oppida not directly reflected in the terminology is their privately owned character, i.e. that they were under the overlordship of noblemen, the church or members of the royal family as private landowners. My contribution to this collection of essays in Vera Bácskai's memory revisits certain aspects of the emergence of oppida from the perspective of their owners. This approach matches the current ‘seigneurial turn’ in urban studies, contending, as Peter Johanek states with regard to the Holy Roman Empire, that ‘seigneurial power…was the driving force in the development of urban life and town foundation’.Footnote 15 Indirectly, this approach also pays tribute to the later decades of Vera's career when she turned from large-scale structural overviews to the impact of personal choices and the history of families and individuals.Footnote 16

These seigneurial efforts were present from the beginning of the emergence of oppida. In my contribution, I will concentrate on three issues in particular. First, what it meant for the overlords to obtain privileges for a settlement and why this was desirable. Secondly, with reference to the ‘market town’ denomination of oppida, I will look at the market functions they performed, and trace out when, how and why the phenomenon of annual fairs first reached the market towns. Thirdly, I will briefly discuss how the overlords practised ecclesiastical patronage, particularly towards the mendicant orders. My time frame will cover the formative period of oppida, the Angevin period, i.e. from 1301 to 1387, which is almost identical with the take-off period of market towns defined by Vera Bácskai.

Market towns: a new upswing from the fourteenth century

The early centuries of urbanization in Hungary – similarly to the rest of Western and Central Europe – were dominated by the church and royal power. Royal seats, bishoprics and regional administrative centres (county seats) were the typical forms of early urban centres up to the mid-thirteenth century.Footnote 17 In addition to these major early centres, there was a fourth type of smaller centre which also contained elements of trade, specialized craft production and lay/ecclesiastical establishments, although not in a unified structure but within a radius of a few kilometres. The lay/ecclesiastical administrative components of these smaller centres were naturally also on a smaller scale: a priory or monastery instead of a bishopric, or a private stronghold instead of a county fortress. The marketplaces serving these clusters of specialized settlements were often named after the day of the week when the market was held, or the settlements were simply called vásárhely, i.e. marketplace. The presence of such ‘territorially segregated centres’, as they were called by the geographer Jenő Major, the first to research them in the 1960s, can be demonstrated all over the Kingdom of Hungary. This shows that they fulfilled the general needs of spatial organization and distribution of commodities of their time.Footnote 18

The thirteenth century brought about fundamental changes in the social and spatial organization of the Kingdom of Hungary, replacing the above-described groups of ‘old centres’ with an emerging network of ‘new towns’. Most of the old royal residences and several bishops’ seats lost their former importance, and so did the more numerous county seats, with the exception of a few situated by the border, along important commercial routes.Footnote 19 The old centres were gradually replaced by new hubs of trade and mining, populated by settlers from within and outside the country, initially also mainly on royal, and to a smaller extent, on ecclesiastical grounds. The most prominent and successful new town was Buda (part of modern-day Budapest), which later became the capital of the kingdom.Footnote 20

The fourth type of proto-urban settlements, the ‘territorially segregated’ centres, experienced a similar fate as the county seats, although for different reasons. Since they consisted of several smaller units, the depopulation or devastation of one of them could easily lead to an imbalance and loss of central functions. This could happen through the dissolution of the monastic or secular centres, the disappearance of the trading or money-lending population that was partly of oriental origin (Armenians or Muslims), or the relocation of specialized craftsmen's communities. Only those centres could survive as market towns that had a concentration of different commercial, administrative and industrial functions; alternatively, if they had just one function, it had to be strong enough to attract further development. For instance, in Szombathely, the successor of antique Savaria, the Saturday market indicated in its place-name (Szombathely meaning ‘Saturday Place’) exerted the dominant influence, attracting craftsmen as well as a mendicant friary, thus becoming a market town under the ownership of the bishop of Győr.Footnote 21 There are a few similar examples in other parts of the country: Marosvásárhely (Târgu Mureş, i.e. ‘marketplace by the Maros/Mureş River’), Kézdivásárhely (Târgu Secuiesc, ‘marketplace of the Kézdi administrative territory of the Széklers’) and Csíkszereda (Mercurea Ciuc, ‘the Wednesday market of the Csík administrative territory of the Széklers’) in Transylvania, Rimaszombat (Rimavská Sobota, ‘the Saturday market by the Rima/Rimava River’) and Dunaszerdahely (Dunajská Streda, ‘the Wednesday market by the Danube’) in northern Hungary (modern-day Slovakia), and Muraszombat (Murska Sobota, ‘the Saturday market by the Mura River’) in southern Hungary (modern-day Slovenia). However, most such early centres played no role in later urban development.

As Vera Bácskai demonstrated, the late thirteenth and the fourteenth century was a period of the slow take-off of oppida: up to 1390, there were altogether 50 localities referred to under this term as opposed to the almost 600 new references in the following century.Footnote 22 The numbers in Table 1 comprise settlements of very diverse levels of urbanity, and of diverse origins. Some originally belonged to the group of royal seats (such as Óbuda, another part of modern-day Budapest); some were bishops’ seats under the overlordship of the respective bishops and cathedral chapters (with further segments eventually owned by the cathedral chapters or aristocratic families); some were county seats that also ended up under the ownership of ecclesiastical bodies and noble families, and some represented the above-discussed ‘marketplace-type’ territorially segregated centres. Even many of the chartered commercial or mining centres of the thirteenth century ended up as market towns. Most of the oppida, however, emerged from the rank of villages, and their development was largely due to the ambitions of their lords: nobles, ecclesiastical landowners or even the king and the queen. As Erik Fügedi pointed out, the new system of estate management prevailing from the thirteenth century was intended to concentrate properties in coherent blocks and required the development of a dedicated estate centre.Footnote 23 Indeed, the most important late medieval magnate families – the Kanizsais, Garais, Újlakis and others – excelled in promoting and embellishing, sometimes even fortifying these towns that also served as their personal residence and manorial centres.Footnote 24

Privileges concerning seigneurial towns

Awarding charters of privilege as a means of settling the status of towns and giving them prerogatives in legal, economic and ecclesiastic matters was a practice of Hungarian kings from the reign of King Emeric (1196–1204) onwards. This policy resulted in about 50 settlements receiving their charters (and some additional confirmations or extensions) by 1301, the dissolution of the Árpád dynasty.Footnote 25 After a protracted fight for succession, Charles I (1301–42) from the Neapolitan branch of the Angevins secured the throne for himself.Footnote 26 Part of his strategy in consolidating his rule was to win over towns by renewing and expanding their privileges or awarding them new ones. During his reign, private landowners gradually started to do the same.

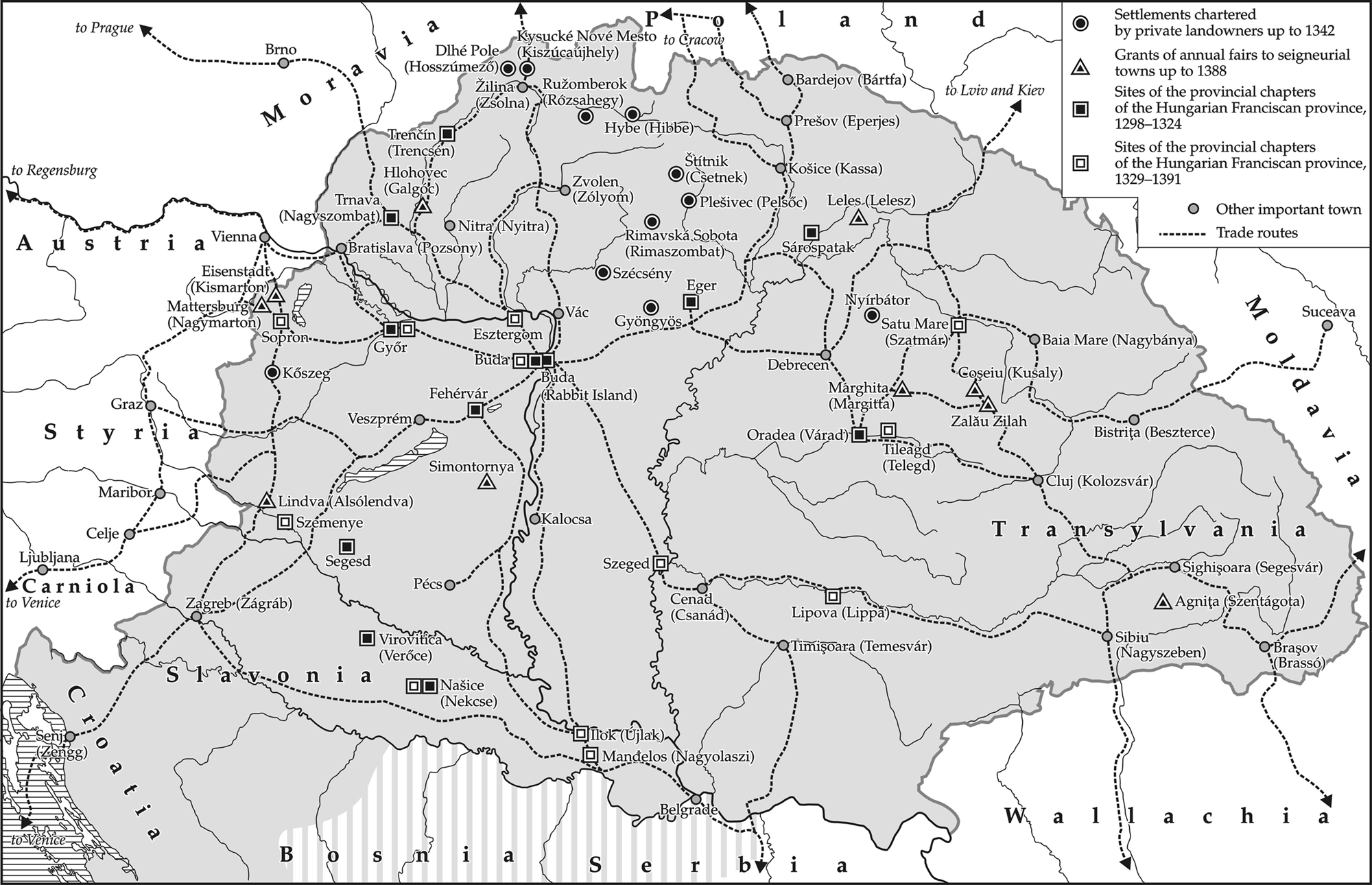

The earliest settlement that received a charter of privilege from a private landowner in medieval Hungary was Kőszeg, a small town closely attached to the residence of the landowning family, who took their name Kőszegi from the same site (see Figure 1).Footnote 27 From the last decades of the thirteenth century, the family became one of the great oligarchs who took the private towns in the Austrian provinces as a model for their foundation rather than the Hungarian royal towns. Although according to the most recent reconstructions as a town Kőszeg was even smaller than previously surmised,Footnote 28 the fact that the Kőszegis took the liberty of issuing privileges for their eponymous seat shows their level of ambitions. They strongly opposed Charles’ endeavour to unify the country, therefore it was no wonder that after he defeated them in western Hungary, Charles took over Kőszeg and reissued its privileges as a royal charter. A new measure was to order Sopron, the closest royal town whose fidelity to the king was already secured, as Kőszeg's court of appeal. This reconfiguration of relationships had a strong impact on the correspondence between Sopron and the neighbouring market towns, ensuring the spread of urban norms and patterns in administrative literacy and self-governance.Footnote 29 Remarkably, and perhaps due to the royal takeover, Kőszeg was termed civitas and not oppidum in the 1328 charter.Footnote 30 It should also be noted in general that the terminology of settlements throughout the fourteenth century was rather inconsistent: settlements that are regularly called oppidum in the fifteenth century and are thus given below as examples may just as well appear as civitas or possessio in the charters.

Figure 1. Oppida in the fourteenth-century Kingdom of Hungary discussed in the article, and their relation to the main trade routes. Designed by the author, drawn by Béla Nagy.

Kőszeg, as a privately founded and chartered town in the late thirteenth century, however, was the exception rather than the rule. In other parts of the country, particularly the sparsely inhabited, mountainous northern region (modern-day Slovakia), local landowners granting privileges started a few decades later, and took the form of settlement charters, whereby the main aim was to attract settlers (hospites, i.e. guests) to clear the forests and colonize the land. The urban or rural character of the new settlements was not decided from the outset; how well the new sites fared rather depended on the location and on later events. These settlement charters offered the tax-free use of the land for a grace period that could last from 3 to as much as 16 years (the latter applied to really severe conditions), and the right for the new community to appoint their own priest.Footnote 31

Judiciary rights were given in minor cases to the settling agent (advocatus, Vogt), who also had the privilege to operate certain services such as mills, and invite craftsmen for a few basic crafts, most frequently bakers, brewers, cobblers and smiths. An important new phenomenon during Charles’ reign was the increased participation of private landlords in the conscious development of their settlements through granting privileges. Such settlement charters were issued by the dozen throughout the fourteenth century by the king, ecclesiastic landowners such as bishops, abbots, priors, chapters (for instance that of the Szepes/Spiš chapter or the chapter of ZagrebFootnote 32) and also by members of aristocratic and noble families.Footnote 33

Some of the early settlement charters followed the examples of previous charters of privilege granted to royal towns. For instance, charters to Pelsőc (Plešivec) and Csetnek (Štítnik), owned by Dominic of the Ákos kindred, took the charter of nearby Korpona (Krupina) as their model. In these cases, the royal consent to charter the towns rewarded the loyalty of the landowner, and not the settlers. The two sites received the right to hold weekly markets, and even the right to administer justice in capital cases, a measure that was far from being justified by the level of their social development.Footnote 34 A notable instance was the charter issued in 1320 by Matthew Csák, another grand oligarch who stood up against Charles I, for his new settlement called Longus Campus (Trencsénhosszúmező, Dlhé Pole) – a morphologically indicative name implying land clearance in a Waldhufendorf-style.Footnote 35 This document commissioned an advocatus called Sidelmanus (another evocative name, meaning ‘settling man or agent’) to create a settlement on Matthew's estate modelled on the custom of nearby Zsolna (Žilina), including its exceptional right to use Zsolna's mother-town, Teschen (Cieszyn) as its court of appeal.Footnote 36 After defeating Matthew, the king took over his incipient towns, just as he did with the Kőszegi family.

From the 1320s, it was not the arrogant oligarchs, but the loyal new aristocracy elevated by the king that took the opportunity to develop their estate centres into towns with the king's consent. In 1325, Judge Royal Alexander Köcski, a loyal supporter of Charles, also decided to use the right of Zsolna to develop his estate. He named the new settlement Königsberg (Congesberch), in honour of the king, although it was later known as Kiszucaújhely (Kysucké Nové Mesto).Footnote 37 Foundations following German law were otherwise an anomaly in the Hungarian legal system; Louis I in 1369 issued a royal mandate to stop this practice and ordered the towns or their overlords to choose a mother-settlement within the boundaries of his kingdom.Footnote 38

Other members of the new aristocracy that Charles I created were also among the founders of seigneurial towns. Master Doncs, comes of Zólyom (Zvolen), first asked for the confirmation of the old (1265) royal privileges for settlers living on his estate at Hibbe (Hybe), then issued himself a charter to his new town named Rózsahegy (Ružomberok) modelled on the liberties of the royal town of Zólyomlipcse (Slovenská Ľupča) that had been chartered by the king.Footnote 39 Thomas Szécsényi, voivode of Transylvania, was even more ambitious in developing his properties and the large estates that he acquired from the fallen oligarch Matthew Csák in northern and north-eastern Hungary. He also exchanged some lands in southern Hungary for the above-mentioned Rimaszombat (Rimavská Sobota) with the archbishop of Kalocsa to make his estate more compact. After all these transactions, in 1334 Szécsényi acquired royal privileges from Charles I for all three of his estate centres: the eponymous Szécsény plus Rimaszombat and Gyöngyös.Footnote 40 These charters granted the towns prerogatives similar to those of Buda, as well as the right to fortify them with stone walls. According to archaeological research, none of the towns was fortified with any walls in the fourteenth century. It is quite telling, however, that the royal charters offer a detailed account of voivode Szécsényi's merits, but do not say a single word about the self-government of these settlements’ communities.Footnote 41 In this respect, the diplomas issued to Thomas Szécsényi closely resemble Charles’ charter to Andrew Bátori, bishop of Várad (Oradea), and his three brothers, in which the king exempted the inhabitants of their eponymous estate centre Bátor (today Nyírbátor) from the jurisdiction of any dignitaries of the realm and exempted them from the payment of certain duties to the royal treasury, in return for the Bátori brothers’ incessant support in Charles’ fights with the oligarchs.Footnote 42 Although the charters issued to these towns were not sufficient in themselves to bolster urban growth, they rewarded the loyalty of Charles’ most favoured retainers. And it also reveals the prevailing trend of the time that royal appreciation and the aristocrats’ ambitions were aimed at developing promising sites into estate centres. We observe that the promotion of seigneurial towns was even more pronounced during Louis I's reign (1342–82). The road in this direction led through the fostering of trade.

Seigneurial towns and annual fairs

Charles I, advised by one of his royal retainers from north-eastern Hungary, Kakas son of Rikalf, the forebear of the Tarkői family, fully appreciated the importance of mining precious metals for the economy of the kingdom. Granting the right of prospecting to private landowners or to towns on the estates of secular and ecclesiastical lords featured in his charters besides developing his own mining towns, first and foremost Körmöcbánya (Kremnica).Footnote 43 The increased output of the mines served as the basis of Charles’ monetary reform and the 1325 introduction of the famous Hungarian golden florin, a favourite means of exchange for merchants in Central Europe throughout the late Middle Ages. Promoting trade, particularly long-distance commercial activities by further measures, however, was not yet high on his agenda. The reign of his son, Louis I, who used the instrument of granting annual fairs to boost commerce, differed significantly from that of his father. Up to the early fourteenth century, the exchange of commodities was chiefly served by weekly markets, complemented by a few noted sites of daily commerce plus three annual fairs that emerged at Székesfehérvár by customary right, and were granted to Zagreb and Buda by royal charters.Footnote 44

Granting fairs was a royal prerogative in Hungary throughout the Middle Ages. The monarch thus ensured the most important precondition of safe trade: royal protection, including the ban on arrestatio (the custom of arresting for a business partner's debts one of his compatriots from the same community). He gave the right of market jurisdiction to the judge of the place where the fair was held. Traders were also free from paying tolls on their way to the market for the period proclaimed in the charter. All these were elements of the market privileges of Buda, which almost all the charters explicitly named as a model.Footnote 45

Charles I does not seem to have issued any new grants of this type. From the reign of Louis I, his mother Elisabeth Piast, his widow Elisabeth Kotromanić and their daughter Mary, however, i.e. from 1342 to 1387, altogether 23 grants of annual fairs have come down to us. Of these grants, 12 were issued to royal towns, and 11 to towns owned by private landowners.Footnote 46 It is the latter group that is of interest to us here (see Figure 1). These grants show a different way in which private landowners contributed to developing their estate centres. At the outset, the sites of these fairs hardly exceeded the level of villages and were most often termed villa or possessio at the time of the grant. It was their owner that made these places worthy of the royal favour. Exceptionally, the grant could be obtained by ecclesiastical overlords, such as the Premonstratensian priory of Lelesz (Leles) in north-eastern Hungary in 1350, modelled on a similar grant to the nearby royal town of Kassa (Košice) three years earlier. However, even there the pivotal point was that Peter, the provost of Lelesz, also served as royal chaplain.Footnote 47

Further grants for holding annual fairs were given to Nagymarton (Mattersburg) owned by Niklinus, nephew of former judge royal Paul of Nagymarton, in 1354. The date of the fair on St James’ Day (25 July) allowed for moving conveniently between the fairs of Sopron (13 July) and Wiener Neustadt (15 August), just as Nagymarton itself is situated between those two towns. The grantee enjoyed the benefits of the grant for decades; he appears as a member of the royal aula as late as 1380.Footnote 48 In 1362, an even more important aristocrat, Palatine Nicholas Kont, was allowed to hold annual fairs at Galgóc (Hlohovec), the principal seat of his estate.Footnote 49 In fact, Galgóc, donated to Palatine Kont as part of a large property, consisted of two main parts. The first was Antiqua Galgoc, the site of a county castle from the early twelfth century, later resettled, for which Kont issued detailed regulations in 1365. The second was a new settlement named Freistadt with reference to its German-speaking settlers and newly awarded liberties, that the palatine promoted by all possible means, including the foundation of a hospital and the acquisition of the grant of a fair.Footnote 50

In parallel to Galgóc, in the eastern part of the country, Debrecen rose to prominence as an estate centre and received privileges in 1361. The town developed as an agglomeration of three villages on a site that provided a dry passage across the swampy flatland of the Hungarian Plain. All three villages were owned by branches of the Debreceni family that took sides with Charles I early on. The royal charter acquired from Louis by the grandson of Dózsa Debreceni, Charles’ legendary warlord, granted immunity to Debrecen from the above-described custom of arrestatio. Even if grants to hold annual fairs were only given to Debrecen after 1405, this privilege clearly shows the inhabitants’ engagement in trade and the landowning family's interest in its undisturbed flow.Footnote 51

In 1366, two members of the aristocratic family Bánfi of Alsólendva (Lindva), later bans (governors) of Slavonia, received a grant to hold fairs on their eponymous estate by an important crossroads en route to Zagreb.Footnote 52 The fairs of Simontornya, the other venue in southern Transdanubia, benefited the Lackfis, another most trusted aristocratic family in Louis’ court: the two petitioners named in the charter were voivode of Transylvania and master of the horse, respectively.Footnote 53 Furthermore, four annual fairs of private landowners were connected to Transylvania and its northern border area: one at Szentágota (Agnita) granted in 1376 to a royal judge of the Saxon area,Footnote 54 one in 1384 at Kusaly (Coșeiu) to the Jakcs family whose most prominent member was royal thesaurarius (treasurer) at that time.Footnote 55 Two places in the northern border area of Transylvania are only known indirectly from a court case arbitrated in 1370: the fair at Margitta (Marghita) was owned by another branch of the Lackfi family, and the one at Zilah (Zalău) lay on the property of the bishop of Transylvania, also a frequent visitor to the royal court. The issue evolved around the competition between these fairs, both of which fell on St Margaret's Day (13 July), and were only two or three days’ walk apart.Footnote 56

The last example presented here, that of Kismarton (Eisenstadt), sums up what clever and industrious owners of market towns could achieve in a couple of decades. Kismarton was also an old centre and, as its German name (‘iron-place’) implies, an early hub of iron production and distribution. The Kanizsai family, shortly after receiving the estate of Szarvkő (Hornstein) as a royal donation in 1364, acquired a murage permission for villa seu oppidum Zabamortun and made it into their new estate centre in 1371. This time, they were indeed able to have the walls built together with a residential urban castle. In 1373, the Kanizsai issued a seigneurial charter to Kismarton's inhabitants, and finally in 1388 John Kanizsai, royal chancellor and archbishop of Esztergom, successfully appealed to the king, at that time already Sigismund (1387–1437), for two annual fairs. In this document, Kismarton appears as libera sua civitas, emphasizing both its seigneurial and fortified character. The foundation of a Franciscan friary in 1386 fits well into the measures for development.Footnote 57

The fair grants covered a period of two to four weeks in royal towns, while in seigneurial towns this period was usually shorter, which points to their relatively more limited scope. The timing of the fairs followed two possible patterns: it was either adjusted to the dates of other fairs arranged on the same route, so that merchants could move from one to the other, or they were held to coincide with the feast of the local parish church's patron saint. In the case of fairs in free royal towns, the former timing was dominant, while in private towns, the two patterns were equally prevalent, which may mean that private towns relied relatively more on the attraction of church feasts.

The choice of which of their villages or incipient towns they proposed to the ruler depended entirely on the grantees. In most cases, the site they chose was the eponymous estate centre of the family, or a branch of it. Furthermore, the sites were situated by major trade routes, road or river crossings (bridges, ferries or fords). To generalize, the combination of family prestige embodied in the name of the given settlement and their favourable location offered the landowning family an added advantage. The centres of landed estates had a better chance of starting on a path leading to urban development, and annual fairs offered a further pillar in consolidating this process.

An important difference between the annual fairs granted to free royal towns and seigneurial towns is in the justification of the royal favour, directly connected to the fact that in case of the former, the right belonged to the community of burghers, whereas in the latter group it was the landowner's personal property. Consequently, in grants to royal towns the most frequently given reason was strengthening their economic capacity, including their ability to construct and maintain their defensive walls. In the case of the privately owned sites of annual fairs, the owner as a person comes to the fore. The rhetoric of these charters corresponds to title deeds granting properties, and especially to the grants of arms, a genre that gained increasing popularity from the early fifteenth century onwards. We find the same ‘catalogues of virtues’ praising the grantee in both cases: unconditional loyalty to the ruler, services rendered to him in times of war and peace, diligence and self-sacrifice. A further common element in the two types of grants to noblemen is that royal grace could be manifest without the need to offer real estate or any direct revenues. Later on, it depended on the economic potential of the site and the agility of its owner how well they joined the developing trade networks, and how much profit the grant yielded.Footnote 58

Seigneurial towns and the patronage of mendicant orders

The third aspect that may add a new facet to the relationship of noble landowners and their towns is ecclesiastical patronage. Besides being the chief patrons of all parish churches on their properties and sponsoring the upkeep and enlargement of their buildings,Footnote 59 the wealthiest landowners also founded other church institutions, particularly hospitals and monastic houses. Among the latter, the fourteenth century started a new trend with the private patronage of the mendicants, whereas during their first century in Hungary, mendicants were mainly settled by royal and, to a smaller extent, by episcopal foundations.Footnote 60

In the absence of foundation charters, it is often difficult to determine the foundation date and the actual founder of monasteries, but it is notable that Franciscan friaries increasingly appeared in private landowners’ estate centres, in the fourteenth century particularly in those of the aristocracy. From the fifteenth century onwards, the middling nobility also made an effort to settle Franciscans on their estates, a trend that favourably coincided with the friars’ willingness to settle in small towns or even villages. The location of the friaries within the settlement, especially its closeness to the lord's residence, was a clear indicator of the tight contact between the friars and their patron. Some of the examples of the patronage of the persons or families discussed in other contexts above are the Franciscan friaries at Szécsény and Gyöngyös founded by Thomas Szécsényi in 1332, the friars of the same order the Lackfis settled at Keszthely in 1368, and at Csáktornya (Čakovec) in 1376, and the Pauline monastery at Csatka founded by Nicholas Kont in the 1350s.Footnote 61

A special aspect of patronage that reached beyond the level of individual friaries was to offer one's seigneurial town as a venue for the provincial chapters of the Hungarian Franciscan province. These meetings were one-off events that did not require a continuous commitment, but through the presence of guests from all over the country they offered excellent publicity opportunities both for the host friary and its patron. Art historians take good advantage of these events and tie the date of rebuilding or redecorating the friaries (especially their chapter halls) to such gatherings. The logistics of the meetings also presupposed a well-developed infrastructure on the host settlement. A survey of these sites – the last example in my overview – highlights how the aristocracy cooperated with the Franciscan Order in bringing these assemblies home.

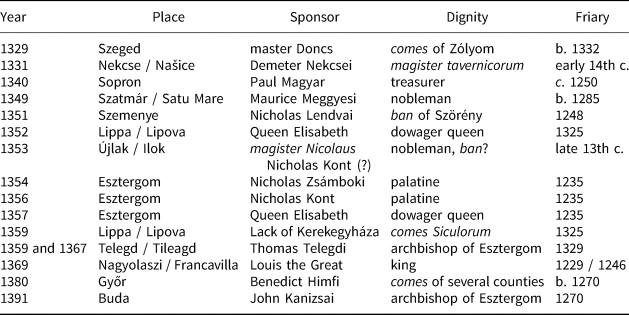

In the fourteenth century, the provincial chapters had no fixed venues, but the location had to be negotiated from one chapter to another, which left ample room for adjusting to political considerations.Footnote 62 The list of the provincial chapters in Hungary has been preserved in a unique source, the Speculum vitae beati Francisci et sociorum eius, printed in Venice in 1504. The very last pages of this voluminous compilation include Capitula fratrum in Hungaria ab initio universis temporibus facta. Footnote 63 The list goes in the order of places and adding the year to them, but patterns are better revealed when we reorder the venues in a chronological sequence. Even if it were reassuring to ascertain the details by further research, the list shows a conscious selection of sites where each year the provincial chapter was held, as well as a clear pattern over time (see Tables 2a and 2b).

Table 2a. Sites of the provincial chapters of the Hungarian Franciscan province, 1298–1324

Table 2b. Sponsors of provincial chapters of the Hungarian Franciscan province, 1329–91

In the years of contested dynastic succession after the dissolution of the Árpád dynasty, chapters were held mainly at bishops’ seats or in towns that received royal charters early on. Várad, Eger and Győr represent the former group, while Nagyszombat (Trnava), Segesd, Verőce (Virovitica), Sárospatak and others the latter, which were all in royal ownership, with the single exception of Trencsén (Trenčín).Footnote 64 The spatial distribution of these sites, mainly in the central part of the kingdom, accurately reflects the regions where steady support for Charles could be expected.

The pattern changed considerably from the 1320s onwards, when Charles’ reign was stabilized. The favoured members of the new aristocracy came to the fore, partly as sponsors of chapters held in royal towns and archiepiscopal seats (Sopron, Esztergom), partly as hosts on their own estates and in their market towns. Not surprisingly, many of the names or sites coincide with the ones discussed previously, with the addition of magister tavernicorum Demeter Nekcsei and treasurer Paul Magyar, palatine Nicholas Zsámboki and comes Benedict Himfi. The distribution of the venues also shows a new pattern, with stronger reliance on southern and south-eastern territories, suggesting that the kingdom's unity and stability had been restored (see Figure 1). This reunited kingdom also provided a strong background for the development of seigneurial towns.

Conclusions

This study pays tribute to Vera Bácskai's work by highlighting the personal incentives of the landowning aristocracy in the emergence of small towns in the Kingdom of Hungary from the 1300s onwards, particularly during the reigns of Charles I and Louis I. The fourteenth-century emergence and steady development of small towns on the estates of private landowners resulted from the coincidence of several factors: the increasing importance of market-oriented commodity production and the needs for its efficient redistribution; the growing number and concentration of the population including a continuous influx of settlers; new patterns of estate management creating more coherent conglomerates of properties; and a stronger integration of the Carpathian Basin in the trading networks of Central Europe. These factors have been highlighted in studies by Vera Bácskai and her colleagues and disciples.

The present article adds a personal angle to this research, namely the intersection of royal and private interests. The aristocrats’ concern to endow their estate centres with privileges or attract new settlers to their lands was dependent on royal approval; likewise, the right to hold annual fairs were granted exclusively by the kings, and one had to be a loyal retainer to be worthy of these grants. Thus, when landowners intended to develop towns on their own estates, it was not enough to support the promising sites directly, within their own means. The good relations of the owners to the newly established Angevin rule played an equally important role, just as did the monarchs’ recognition that their grants to secure their retainers’ loyalty and foster urbanization could kill more birds with one stone. Following the royal model of supporting the upcoming mendicant orders added a further dimension to the overlords’ activity in their incipient urban settlements. All this shows that royal influence, directly or indirectly, had a major impact even on the development of towns on private lands in the Angevin period.

This strong interdependence of central power and the emergence of seigneurial towns may add a new facet to the specificities of regional development in East Central Europe, its Sonderwege or interconnectedness with the rest of Europe. Vera Bácskai closes her 1995 study with an intriguing sentence: ‘Despite several similarities, the small towns of the European periphery belonged to a rather different world than the small towns of the European centre.’Footnote 65 Integrating the conclusions of this research with comparative studies on a regional level, posing similar questions on the emergence of seigneurial towns in Bohemia, Moravia, Silesia, Poland and Austria – or indeed, in other polities on the fringes of Europe – will open new chapters towards a more informed understanding of this intricate issue of regional specificities.