Introduction

Right before the Ghost Festival in 2022, the Vietnamese community in Taiwan launched a petition demanding the removal of a TV ad by Carrefour, a multinational supermarket chain. This ad depicted a Vietnamese woman and her Taiwanese mother-in-law grocery shopping for the festival. The Vietnamese woman instructed her elderly mother-in-law to fetch a snack from a high shelf in the store without any assistance. This representation of bossy behavior on the part of the Vietnamese woman was perceived as demeaning to the image of Southeast Asian migrant spouses and, consequently, Carrefour faced accusations of zhǒngzú qíshì ‘racial discrimination’ from the Vietnamese Club Taiwan (VCT). VCT's leader posted on her Facebook page (Trần Thị Reference Trần Thị2022): ‘Does such a prominent European and Taiwanese joint venture not realize that making racist jokes is akin to committing a crime?’Footnote 1 She condemned the ad for violating the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD). Indeed, central to this racial controversy was the fact that the Vietnamese woman was portrayed by a Taiwanese man, A-Han, an influencer with a significant online following (e.g. 1.1 million Facebook followers), known for mimicking Mandarin accents. His depiction of the Vietnamese woman, Ruan Yuejiao, has gained substantial popularity since 2017. Ruan Yuejiao speaks primarily Mandarin with a ‘Vietnamese accent’, rarely using Vietnamese. That is, this character's intended audience is the Taiwanese majority.Footnote 2

Drawing attention to the ICERD and the European ownership of the supermarket, the VCT's charges of discrimination utilized global anti-racist discourse to frame the relationship between the Taiwanese majority and Vietnamese spouses, akin to white-majority oppression of the racial minority (cf. Pak & Hiramoto Reference Pak and Hiramoto2023). The VCT's protest needs to be understood within the entrenched racialization of Vietnamese spouses and other Southeast Asian spouses in Taiwanese racial discourse. Accounting for 90% of migrant settlement in Taiwan, marriage migrants constitute 2.3% of the population. The Chinese population from PRC and Southeast Asians constitute 91% of marriage migrants, most of whom are women. Among the Southeast Asian spouses, Vietnamese migrants are the majority, followed by Indonesians. Southeast Asian migrants, despite their internal diversity, are often lumped together (cf. Park Reference Park and Lee2022) and considered racially different from the Taiwanese majority.

The political representation of Southeast Asian migrants has changed significantly since the 1990s in Taiwan, when transnational marriages brokered by commercial firms were prevalent. In the 2000s, the peak in marriage migration incited racist sentiments in political discourse, with eugenic concerns about these migrants ‘threatening’ the quality of the population and suggestions that they should limit their offspring (Lan Reference Lan2019). In the following decade, particularly after 2016, Taiwan's approach started to shift towards embracing a multicultural paradigm. With geopolitical aims to diverge from PRC (also see Wan Reference Wan2022), Taiwan's New South-Bound Policy envisions Southeast Asian migrants and their languages as key players in a globalized future (Kasai Reference Kasai2022), strengthening ties with Southeast Asia as a countermeasure to China's influence and positioning them as integral to the nation's economic progress (Lan Reference Lan2019). However, the multicultural paradigm has been selective, primarily recognizing the role of marriage migrants while often overlooking other groups of Southeast Asian migrants, like migrant workers. For example, during the Covid pandemic, in legislative discussions, migrant spouses were acknowledged as rights holders and citizens, while migrant workers were depicted as potential health risks (Liu & Wan Reference Liu and Wan2024). That is, racism against Southeast Asians still haunts Taiwan.

Amidst the shifting discourse, A-Han created the character Ruan Yuejiao in 2017. According to him, this portrayal sought to subvert the traditional stereotypes linked to Southeast Asian spouses and to showcase Taiwan's multicultural landscape. I specifically examine how linguistic features and indexical meanings contributed to the construction of a racialized spouse persona of Vietnamese women, and within the broader raciolinguistic context, highlight the problematic nature of such constructions. Located within the growing field of digital enregisterment (Chau Reference Chau2021; Ilbury Reference Ilbury2022, Reference Ilbury2024) and raciolinguistics (Rosa & Flores Reference Rosa and Flores2017; King Reference King2020; Pak Reference Pak2023), this study is particularly interested in analyzing the ‘uptake’ (Agha Reference Agha2011) of the character by different actors. Uptake is ‘a kind of perception or awareness of a fragment of semiotic behavior that can lead to the recycling or reinterpretation of the fragment’ (Cole & Pellicer Reference Cole and Pellicer2012:451). By inspecting the uptake of the Ruan Yuejiao character, I demonstrate how linguistic features are mediatized together with a particular set of social meanings and recognized as the Vietnamese accent. Such mediatization, in turn, provokes an anti-racist reaction from the Vietnamese community, and I show how this reaction is further re-interpreted by the Taiwanese majority as internalized racism.

The structure of the paper is as follows: first, I identify the paper's contribution to the growing body of raciolinguistic work, providing context for the racialization of the Vietnamese spouse community in Taiwan. After presenting this background, I outline the methodology. The research presented here employs digital ethnography to document the trajectory of the character Ruan Yuejiao from 2017 onward, using different types of data to illustrate ‘raciolinguistic enregisterment’, a process ‘whereby linguistic and racial forms are jointly constructed as sets and rendered mutually recognizable as named languages/varieties and racial categories’ (Rosa & Flores Reference Rosa and Flores2017:631). Finally, I detail the chain reactions that this character incited.

Positioning the study in raciolinguistics

Raciolinguistics pays attention to how the link between race and language is naturalized via ideological processes (Rosa & Flores Reference Rosa and Flores2017). Flores & Rosa (Reference Flores and Rosa2023:424) have cautioned against a static view of race, to critique how raciolinguistics has been misapplied in some studies that ‘perpetuate the tendency toward (socio)linguistic essentializations not only of racial identity but also of “real”, “authentic”, and “distinctive” language’. Race should be understood as a dynamic process that is constructed within various geopolitical contexts.

Central to this approach is the concept of enregisterment, the process through which a set of linguistic practices becomes established as a distinct, socially recognizable linguistic register (Agha Reference Agha2003). A related concept is Inoue's (Reference Inoue2006) idea of the ‘listening subject’, which emphasizes the role of the listener in shaping how the link between social groups and language use is interpreted. For instance, Lee & Su (Reference Lee and Su2019) analyzed how Taiwanese netizens attacked a Taiwanese American man, labeling him as both an inauthentic Taiwanese and an inauthentic American due to his presumed competence in English and Mandarin. That is, the listener plays an active role in naturalizing the perceived relationship between race and language use. According to what Inoue calls ‘indexical inversion’, language ideologies may even create the very linguistic forms they claim to record. Indexical inversion in a raciolinguistic context is evident in Jane Hill's (Reference Hill1998) work where white listeners might ‘hear’ accents in the English speech of Spanish speakers in the US, even when no such accent is present.

The notion of the listening subject not only concerns sociolinguistic perception, but also contributes to understanding how dominant groups may use linguistic features they believe are associated with a certain race for a variety of purposes. For example, white people in the US use Mock Spanish not to claim any cultural affiliation with the Spanish-speaking population, but instead to invoke second-order indexicalities (Silverstein Reference Silverstein2003) built upon the indexical link between Spanish words and a Spanish-speaking population, signalling cosmopolitanism, association with the US Southwest, or a sense of humour (Hill Reference Hill1998).

Moving away from the concept of the listening subject, raciolinguistic theory has also gained traction within third wave variationist sociolinguistics, where linguistic variation can serve as social semiotics for constructing identity (Eckert Reference Eckert2012). Racial minority groups may also employ certain linguistic features either to assert or to challenge their racialized identities (King Reference King2020, Reference King2021). For instance, Malaysian comedian Nigel Ng, known for his Uncle Roger character, self-racializes a pan-Asian identity by adopting stereotypical linguistic features of Englishes associated with distinct varieties in East and Southeast Asia, in order to target the global online content market (Wu Reference Wu2023).

In sum, while minority groups might resist or utilize first-order racial associations, dominant groups may adopt racialized linguistic features for second-order indexical purposes without claiming a first-order indexical affinity with the racialized minority group (Hill Reference Hill1998; Bucholtz Reference Bucholtz2010; Bucholtz & Lopez Reference Bucholtz and Lopez2011). The outcome then is often perceived as a cultural appropriation where the racialized body associated with these linguistic features is ‘bleached’ (e.g. Roth-Gordon, Harris, & Zamora Reference Roth-Gordon, Harris and Zamora2020). Hill (Reference Hill2008:58) conceptualizes the process of ‘linguistic appropriation’, whereby a particular group ‘adopt[s] resources from the donor language, and then tr[ies] to deny these to members of the donor language community … reshaping the meaning of the borrowed material into forms that advance their own interest, making it useless or irrelevant, or even antithetical, to the interests of the donor community’. In this article, I demonstrate a form of raciolinguistic listening that I term indexical hijack, where one group exerts violent control over the indexicalization of linguistic resources associated with another group.

Indexical hijack

Unlike Hill's concept of linguistic appropriation, in indexical hijack, the hijacking group prioritizes the ‘indexical field’ (the plane's destination) (Eckert Reference Eckert2008) of semiotic/linguistic features rather than the features themselves (the carrier), disregards how the hijacked group indexicalizes their own features (the passengers’ intended destination) and imposes their own indexical interpretation (the hijacker's demanded direction of the carrier) upon the hijacked group. Furthermore, in this article, I demonstrate how an ideology of post-racial multiculturalism can enable the violent nature of indexical hijack. Post-racialism promotes the belief that society has transcended racism and has shifted towards embracing a diverse range of racial and cultural identities (e.g. Meghji & Saini Reference Meghji and Saini2018; Babcock Reference Babcock2022). In the context examined here, the dominant group first racializes certain linguistic features, then employs these features to claim affiliation with the racialized minority in what is ostensibly a positive discourse, rather than for reasons of mockery as in blackface or of meta-parody as in linguistic minstrelsy (Bucholtz & Lopez Reference Bucholtz and Lopez2011). However, the racialized minority interprets the dominant group's linguistic practice as racist, while the dominant group denies this indexical interpretation, instead insisting that the racialized group has internalized racism.

Indexical hijack can be understood as a combination of indexical bleaching and indexical inoculation in a context of power asymmetry. Indexical bleaching is a term akin to semantic bleaching, where a linguistic feature loses its original social meanings through processes of decontextualization and recontextualization (Squires Reference Squires2014). For example, Bucholtz (Reference Bucholtz, Samy Alim, Rickford and Ball2016) describes how white speakers Anglicize the pronunciation of names from racial minorities, deracializing the names. Indexical inoculation, in Silverstein's (Reference Silverstein2023) lecture notes, is described as a process through which metapragmatic awareness is given to a particular linguistic variety and re-enregisters the variety so its associations are with a brand-new indexical meaning; for example, labelling the third-person plural pronoun they as the gender neutral and progressive register instead of a vernacular one. In this article, the hijacker group enforces indexical bleaching and indexical inoculation on linguistic features of which the first-order indexicality is demographically linked to the minority group. This enforced indexical bleaching and indexical inoculation compels the minority to erase the negative stigma associated with the racialized variety and to recast it as a positive identity marker.

Taiwanese racialization of Vietnamese migrants

Race is understood differently across cultures (Wong, Su, & Hiramoto Reference Wong, Su; and Hiramoto2021). In Taiwan, Vietnamese people are often grouped with other Southeast Asian nationalities and treated as an inferior racial group compared to the Taiwanese majority (Wang & Bélanger Reference Wang and Bélanger2008). As racialized migrant spouses, Vietnamese women's oppression is intersectional in nature: they are oppressed due to the interlocking forces of race and gender (Hoang & Yeoh Reference Hoang and Yeoh2015). Vietnamese migrant spouses have been racialized with biological qualities different from that of the Taiwanese majority. Their biological fitness as mothers has been challenged, with concerns about their fertility stemming from exposure to toxic chemicals during the Vietnam War (Tsai Reference Tsai2011) as well as the risk of developmental delay in their children (Hsia Reference Hsia2007). Furthermore, Vietnamese women have been portrayed homogeneously by marriage brokers as docile, obedient, and easily satisfied, making them ‘ideal wives in the traditional sense’, especially in working-class families, where women need to handle housework and work at the same time to maintain economic survival (Tseng Reference Tseng2016:210). Vietnamese women have also been represented as ‘virgin brides’ by the brokers in order to attract their male clients (Wang Reference Wang2010). On one hand, Vietnamese women have been viewed as virtuous and submissive; on the other hand, they have been sexualized. In addition, the migration of Vietnamese spouses has been perceived by the Taiwanese majority to be motivated by financial gain, with a prevalent view that their marriages are absent of genuine affection (Hoang & Yeoh Reference Hoang and Yeoh2015). This has led to the stigmatization of Vietnamese spouses as potential ‘runaway brides’ and as involved in illegal activities, including sex work (Lan Reference Lan2008; M.-C. Lin Reference Lin2019). This stigma has extended into the private sphere, where Vietnamese women have been either prohibited from using their native language at home (Cheng Reference Cheng2013) or have avoided transmitting their mother tongue out of fear of being recognized and ridiculed as foreign (M.-C. Lin Reference Lin2019). Mandarin has become a resource for these women to integrate into Taiwanese society and to assert independence and an image of good motherhood (S. Lin Reference Lin2018; M.-C. Lin Reference Lin2019).

Data and methodology

This article includes online observations made between the first Ruan Yuejiao video in 2017 and an apology by A-Han published on 8 August 2022. Using digital ethnography as a method (Hsiao Reference Hsiao2022), I closely followed the development of the character and its uptakes. Four important moments were included in the article—the creation of Ruan Yuejiao by A-Han, the transformation of Ruan Yuejiao by A-Han, the meme genre on TikTok of Ruan Yuejiao's cucumber dance, and the casting of Ruan Yuejiao in the ad of Carrefour. These moments coincided with Google Trends peaks in online popularity for the term Ruan Yuejiao. From the very beginning, my observations were motivated by a sociolinguistic hunch that this character might spark future racial controversies. The observations encompassed watching Ruan Yuejiao's performances, monitoring journalistic interviews with A-Han, archiving racially related viewer comments, and tracking the character's propagation across various social platforms like Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, and TikTok. Additionally, I delved into perspectives within the Vietnamese community by collecting articles authored by Vietnamese migrants from the media site, Independent Opinion, which regularly featured articles on migrant issues.

In terms of my positionality, I am a Taiwanese millennial immersed in digital culture, and I am not of Southeast Asian descent. The observations involved in this article were made when I was an international student in the UK, during which I was often racially harassed. My positionality as both the target audience of A-Han's performance and a racial minority in the UK is important for the application of a raciolinguistic lens to the character.

This study employed a variety of methods to document the creation of Ruan Yuejiao by A-Han and to understand reactions to the character. Content and sociophonetic analyses were conducted to delineate the persona performed through Ruan Yuejiao and the linguistic features linked to this persona, as well as their function in discourse. This methodology was then applied to analyze the character's recreation by other online content producers. The Vietnamese community's views were collected from public protest letters and columns. A thematic analysis was performed to identify the predominant themes in the majority Taiwanese audience's online discussions regarding the Vietnamese community's protests. Early in the research process, some linguists suggested that I empirically assess the authenticity of A-Han's portrayal of Vietnamese-accented Mandarin in order to address the racial controversy. However, this article posits that the controversy's core does not revolve around the ‘authenticity’ (if any) of A-Han's representation of the accent. In fact, the protests from the Vietnamese community did not mention the empirical validity of the accent portrayal at all. From a raciolinguistic perspective, the issue lies in the listening subject, that is, the Taiwanese majority. Regardless of whether A-Han bases his accent on an actual Vietnamese woman's accent, we need to problematize how the accent has been re-enregistered with specific social traits through mediatization. This work aligns with Rosa & Flores (Reference Rosa and Flores2017), who advocate for examining the interpretive and categorizing practices of listening subjects who are racially hegemonic in their perception.

The construction of a Vietnamese spouse persona

Ruan, the surname of the Vietnamese spouse, is the Mandarin equivalent of the common Vietnamese surname Nguyễn. In the early videos, Ruan Yuejiao always opened the video with “Hi, everyone, I am Ruan Yuejiao, from Ho Chi Minh City of Vietnam”—a background shared by many Vietnamese spouses in Taiwan. Contrary to the stereotype of a diligent daughter-in-law proficient in household chores, Ruan Yuejiao was portrayed as a lazy individual who shirked housework, leaving most tasks to her mother-in-law. Rather than being virtuous, she loved adult jokes. A-Han's early portrayals of Ruan Yuejiao were all presented as a cisgender man without any visual resources to embody normative femininity (Figure 1), only performing the woman character through verbal language including the narrative and acoustic resources. Her inclination for risqué humor, often involved her own or her husband's body, juxtaposed with her male-presented character to produce comedy. These characteristics starkly contrasted with traditional stereotypes of Vietnamese women. Additionally, Ruan Yuejiao was depicted without children, another deviation from the stereotyped reproductive role of a Vietnamese wife. Adding another layer to her complex portrayal, she attended a Mandarin class and criticized her mother-in-law's Mandarin for having a Taiwanese Hokkien accent (i.e. Taiwan Guoyu), implying her superior proficiency in the language, which is also reflected in how she was good at wordplay.

Figure 1. The first video; the line reads ‘because I have a bootylicious figure’ (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ogeJlkZtQVU).

In the first six videos featuring Ruan Yuejiao, various phonological features were employed to construct her accent. A prominent and persistent suprasegmental feature in A-Han's portrayal was the nasality in Ruan Yuejiao's voice. This nasal quality garnered metalinguistic attention among viewers of Ruan Yuejiao's performances. Notably, when A-Han underwent surgery to correct a deviated nasal septum, media reports highlighted fans’ concerns about the potential impact on the Ruan Yuejiao character, specifically the alteration of her nasal voice quality. Figure 2 provides a visual illustration of how Ruan Yuejiao elongated the nasal coda in her speech, taken from the first video (see extract (1)). This contributes to the heightened perception of nasality in her voice.

(1) Ruan Yuejiao's integration into Taiwanese society (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ogeJlkZtQVU)

我嫁來台灣八年

Wǒ jià lái táiwān bā nián

T1→T4 /j/-dropping

‘I have been married to Taiwan for eight years.’

很喜歡台灣

hěn xǐhuān táiwān

/ɕ/→[s]

‘I like Taiwan very much.’

之前大家都叫我越南新娘

zhīqián dàjiā dōu jiào wǒ yuènán xīnniáng

/j/-dropping

‘In the past, everyone called me a Vietnamese bride.’

現在都叫我台灣媳婦

xiànzài dōu jiào wǒ táiwān xí fù

/ɕ/→[tɕ] /f/→[h]

‘Now they call me a Taiwanese daughter-in-law.’

為什麼台灣男生看到我會微笑,因為我前凸後翹

wèishéme táiwān nánshēng kàn dào wǒ huì wéixiào, yīnwèi wǒ qián tú hòu qiào

/ɕ/→[s] /j/-dropping

‘Why do Taiwanese boys smile when they see me? It's because I am bootylicious.’

Figure 2. Ruan Yuejiao's utterance of xǐhuān táiwān ‘like Taiwan’.

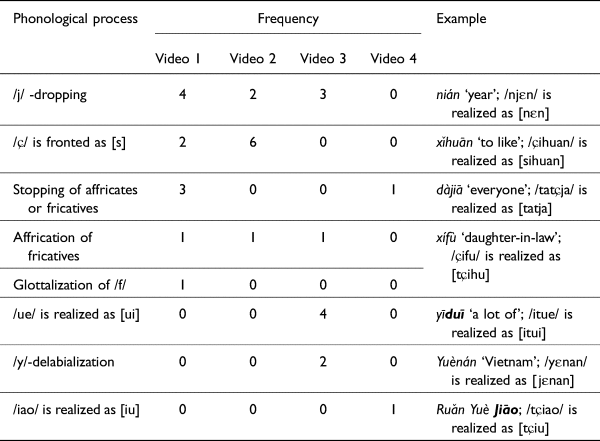

In the first video (extract (1)), Ruan Yuejiao's monologue was consistently presented with marked segmentals. These marked segmentals, however, varied considerably (see Table 1); each video presented slightly different accents. Monophthong quality shifted as well, without a clear pattern. Among the marked segmentals in the first video, only a few reoccurred in subsequent videos, with each adding new phonological elements. In the fourth video, only two marked phonological processes were observed, differing from those in the third. This pattern suggests that analyzing each video for individual segmental features might miss the larger picture; instead, the key lies in recognizing that the segmental phonological processes appeared irregular and somewhat random.

Table 1. Phonological processes involving segmentals in the first four videos.

These ‘chaotic’ segmental features may simply be used to index Ruan Yuejiao's L2 learner identity. However, phonologically, many of the features cannot be supported by an account of L1 transfer from Vietnamese (L.-Y. Lin Reference Lin2005). Thus, it is not the specific features that are central to the character's construction, but rather how these features, indexing ‘speech errors’, collectively contribute to the perception of Ruan Yuejiao's L2 accent.

In the first video, these marked segmental features were present in words that carried important information. For instance, in the term daughter-in-law, the word-initial palatal fricative was affricated and /f/ was glottalized. This is where she referenced the shift of the term referring to Southeast Asian spouses. Another example is the use of a temporal frame in the past, where she invoked /j/-dropping. This serves to emphasize how the stigma surrounding Southeast Asian spouses was overcome. The term foreign brides used to be the predominant way to refer to these spouses (Hsia Reference Hsia2007). Indeed, in 2003, a feminist organization called for a change in this identity term after consulting the spouses, for the spouses considered foreign brides to carry social bias. Ruan Yuejiao's mention of foreign brides thus served as a contextualization cue (Gumperz Reference Gumperz1982), signaling her awareness of the stigma associated with Vietnamese spouses. Subsequently, she used the term Taiwanese daughters-in-law as a replacement, suggesting a shift toward the spouses’ integration into Taiwanese society. The mention of the term not only suggested a post-racial ideology, but also challenged the notion that Vietnamese spouses were distant from familial closeness.

In her debut video, Ruan Yuejiao portrayed herself positively engaging with Taiwanese society, challenging the stereotype that Vietnamese women were motivated by financial gain through marriage. Ruan Yuejiao's humor emerged through wordplay such as rhyming, particularly noticeable when the second syllable in smile and the last in bootylicious both rhymed with the triphthong /iau/. Notably, presenting herself with a ‘bootylicious’ figure, comedically incongruent with her non-female presentation, subverted the typical sexualized gaze directed at Vietnamese women, with Ruan Yuejiao taking an active role in reinterpreting her body's representation.

Another marked feature is the merging of Tone 1 (T1; high-level tone) and Tone 4 (T4; high-falling tone) in the first line in extract (1). As Mandarin is a tone language, F0 contour and height can distinguish lexical meanings, making the merger perceptually salient. This tone merger was persistent throughout Ruan Yuejiao's videos. The distinction between the two tones lies on a continuum. T4 can sound like a T1 when it flattens to a certain extent. Figure 3 illustrates that T1 and T4 exhibit contour similarities in these videos. I extracted the F0 from all instances of T1 and T4 in the first six videos, except the fifth, where A-Han frequently alternated between himself and Ruan Yuejiao, complicating character identification. In the third video, T1's slope was even steeper than T4's. A general upward shift in F0 from the first to the third video was also observed, performing a feminine voice, stabilizing from the third video onward.

Figure 3. Ruan Yuejiao's shift in quality of Tone 1 and Tone 4.

Tone quality was also utilized by Ruan Yuejiao to produce comedy. In the third video (extract (2)), the most-viewed, Ruan Yuejiao shared a story in which she misunderstood her mother-in-law's utterance of sleep as dumplings. These two Mandarin words only differ in lexical tones.

(2) A good mother-in-law (https://www.youtube.com/shorts/_PXO_cLiEXw)

我昨天看電視看到很晚

Wǒ zuótiān kàn diànshì kàn dào hěn wǎn

‘I watched TV very late yesterday.’

我婆婆直接衝進來對我好兇

Wǒ pópo zhíjiē chōng jìnlái duì wǒ hǎo xiōng

‘My mother-in-law came charging in and was so fierce to me.’

他對我說 叫我煮水餃

Tā duì wǒ shuō jiào wǒ zhŭ shuǐjiǎo

‘She told me to cook dumplings.’

我跑去廚房煮一堆水餃

Wǒ pǎo qù chúfáng zhŭ yī duī shuǐjiǎo

/ue/→[ui]

‘I ran to the kitchen and cooked a bunch of dumplings.’

一直煮 我煮一堆 一堆水餃 煮到天亮

Yīzhí zhŭ wǒ zhŭ yī duī yī duī shuǐjiǎo zhŭ dào tiānliàng

/ue/→[ui] /ue/→[ui]

‘Keep cooking. I cooked a bunch- a bunch of dumplings until dawn.’

我婆婆結果醒來跟我說

Wǒ pópo jiéguǒ xǐng lái gēn wǒ shuō

‘My mother-in-law woke up and told me.’

我沒有叫你煮水餃 我叫你去睡覺

Wǒ méiyǒu jiào nǐ zhŭ shuǐjiǎo wǒ jiào nǐ qù shuìjiào

‘I didn't ask you to cook dumplings, I told you to go to sleep.’

我搞錯 很好笑

Wǒ gǎo cuò hěn hǎoxiào

‘I misunderstood. It's funny.’

我現在吃不完 我水餃我吃不完

Wǒ xiànzài chī bù wán wǒ shuǐjiǎo wǒ chī bù wán

‘I can't finish now. I can't finish the dumplings.’

The third video introduced a surprising twist to the dynamic between the Taiwanese mother-in-law and Ruan Yuejiao, overturning the stereotyped portrayal of bossy mothers-in-law towards their Southeast Asian daughters-in-law. Contrary to expectations, the mother-in-law's late-night request was not for Ruan Yuejiao to cook but rather to rest, signifying care. This moment subverted the common narrative of emotional distance within these families, a theme that recurs as an element of subversion throughout the series.

(3) Ruan Yuejiao as a lazy and zany person (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bdXGuyvxmcg)

我今天我早上我婆婆問我說

Wǒ jīntiān wǒ zǎoshang wǒ pópo wèn wǒ shuō

‘My mother-in-law asked me this morning’

為什麼我睡到下午三點

Wèishéme wǒ shuì dào xiàwŭ sān diǎn

/j/-dropping

‘Why do I sleep until three o'clock in the afternoon?’

我跟他說

wǒ gēn tā shuō

‘I told her’

我是阮月嬌

wǒ shì ruǎnyuèjiāo

‘I am Ruan Yuejiao.’

喜歡睡覺

xǐhuān shuìjiào

/ɕ/→[s]

‘I like to sleep.’

喜歡包水餃

xǐhuān bāo shuǐjiǎo

/ɕ/→[s]

‘I like to make dumplings.’

不喜歡跋筊

bù xǐhuān pua̍h-kiáu

/ɕ/→[s]

‘I don't like gambling.’

Ruan Yuejiao's zany personality was performed in the second video (extract (3)). She was depicted as somewhat lazy, shown by her disengagement with the family business and her late rise at 3pm, defying the hardworking stereotype. When she justified her sleeping habits by stating her fondness for sleep, she challenged the stereotype of the submissive and industrious Vietnamese spouse. Furthermore, Ruan Yuejiao's wit was revealed in her playful remarks about enjoying dumpling preparation and her aversion to gambling (where she switched to Taiwanese Hokkien—pua̍h-kiáu), showcasing her zany nature because the responses to her mother-in-law's question seemed infelicitous. Later it became clear these words were used for their rhyming effect of /iau/ across languages, adding a layer of humor to her persona and demonstrating her multilingual identity (S. Lin Reference Lin2018). Importantly, by expressing her dislike for gambling, she separated herself from negative perceptions of Vietnamese spouses being involved in illicit activities.

This study cannot analyze each video in detail due to word constraints; however, from what has been observed, Ruan Yuejiao was constructed as a zany, humorous figure, defying conventions and engaging in wordplay, steering clear of traditional gender expectations. Her accent, with its distinct features such as nasality, high pitch, and particular tonal mergers, alongside occasional ‘speech errors’, assisted in crafting this racialized persona.

The uptake of Ruan Yuejiao

In this section, the discussion focuses on how various audiences have engaged with the character of Ruan Yuejiao. This engagement, or uptake, goes beyond simple imitation. The term uptake is used here to denote the range of reactions to a style—be it through close emulation of the style or the incorporation of additional elements into it in ways that are only partially aligned (Agha Reference Agha2011). Uptake involves both repetition and interpretation, serving not just to replicate but to reinterpret the sameness or difference between repeated forms within different ideological frameworks (Gal Reference Gal2019). A-Han himself exemplifies this concept of uptake with Ruan Yuejiao, as evidenced by the reformation of Ruan Yuejiao over a one-year interval.

A-Han's remaking: Ruan Yuejiao as a zany, bossy spouse

Since 2020, Ruan Yuejiao's character has been outfitted with a signature look: a T-shirt marked by red stripes, form-fitting skinny jeans, and a more feminized appearance using breast forms. The new appearance of the character has been featured in various commercial partnerships, including products for skin whitening, food processors, and even invitations to a variety show which features a regular cast who are all actual immigrants. This also includes the controversial Carrefour advertisement mentioned at the beginning of the article, indicating that the character has become, to a significant extent, highly enregistered.

The debut of the new Ruan Yuejiao was in a collaborative project in July 2020, where she was featured in a government initiative to promote Covid stimulus vouchers to the Southeast Asian spouses (Figure 4). In this campaign video, Ruan Yuejiao humorously failed to recognize the Premier of Taiwan, mistaking him for a celebrity, which reinforced her zany persona. In this video, the marked segmentals diminished. The speech instead relied solely on suprasegmentals such as nasality, a high pitch, and the merger of T1 and T4 for the performance of a Vietnamese woman. With Ruan's more feminized appearance referred to above, Ruan Yuejiao's speech was no longer the sole semiotic resource performing the Vietnamese character, revealing how language is an embodied resource that produces the body (Bucholtz & Hall Reference Bucholtz and Hall2016; Wan, Hall-Lew, & Cowie Reference Wan, Hall-Lew; and Cowie2024), much like other semiotic practices such as clothing.

Figure 4. Ruan Yuejiao's new appearance and the Premier Tseng-Chang Su (https://youtu.be/_KVl1TjpL_M?t=244).

As mentioned, the key audience for Ruan Yuejiao was primarily the Taiwanese majority. When the government partnered with the character to publicize Covid stimulus measures, it was about employing a friendly, approachable strategy commonly favored by the Taiwanese government for engaging its citizens (Lien & Wu Reference Lien and Wu2021), rather than a direct outreach to the Southeast Asian community. A-Han's intention to use Ruan Yuejiao to dismantle prevalent stereotypes among the Taiwanese majority mirrored this approach; the Vietnamese community's perspective was not the focus in the character's portrayal.

In 2022, the video series ‘Yuejiao is a good daughter-in-law’ (月嬌好媳婦) was released. Despite the title, Ruan Yuejiao remained characterized by her laziness and a newly introduced bossiness towards her mother-in-law, as seen in a scene where she quipped about not needing a robot vacuum like other Vietnamese spouses, comparing her mother-in-law with a cleaning robot. This ironic twist on the title served as comedic relief, drawing viewers to the series. The newly introduced dominant role over her mother-in-law persisted in the Carrefour TV ad where Ruan instructed her mother-in-law to retrieve items from a high shelf. While this departure from the traditional gender roles associated with Vietnamese spouses had comedic appeal, the amplified humor led to further backlash from the Vietnamese community, who viewed Ruan Yuejiao as impolite or even disrespectful.

Online creators: Ruan Yuejiao as an entertaining ribald

In April 2022, A-Han posted an Instagram story (fifteen seconds) where Ruan Yuejiao wore a scooter helmet, held two cucumbers (one is bigger than the other) (see Figure 5), and rapped a cucumber song (extract (4)).

(4) The cucumber song (https://www.instagram.com/hanhanpovideo/reel/CcqKbeAvjOD/)

不粗的好吃,粗的不好吃

Bù cū de hào chī, cū de bù hào chī

[u][u]

‘The small one tastes good; the big one doesn't taste good.’

不粗的比粗的還好吃

bù cū de bǐ cū de hái hào chī

[u]

‘The small one tastes better than the big one.’

不粗的好吃,粗的不好吃

bù cū de hào chī, cū de bù hào chī

[u] [u]

‘The small one tastes good; the big one doesn't taste good.’

不粗的好吃才是好吃

bù cū de hào chī cái shì hào chī

[u][u]

‘The small one tasting good is the real good taste.’

Figure 5. Ruan Yuejiao's cucumber dance was uploaded to TikTok.

In this performance, Ruan Yuejiao used a big cucumber and a small cucumber, drawing attention to the size difference while mentioning ‘the big one’ and ‘the small one’. Additionally, Ruan Yuejiao emphasized her breast by pushing it out. These elements, along with the sexual connotations inherent in cucumbers, contributed to the sexualized nature of this video. Due to the highly sexualized nature of this performance, the cucumber song quickly became a popular meme on TikTok. TikTok, a video-sharing platform launched in 2016, has become the fifth most frequently used social media platform in Taiwan, with 26.9% of the population using it (OOSGA 2023). TikTok users either lip-synced the original sound of A-Han or verbally imitated the lines. Most of the videos employed the hashtag #不粗的好粗 bùcū de hǎocū, which literally translates to ‘the small one tastes good’. I identified fourteen original sounds that were mostly popular, with 1,979 TikTok videos using one of them. One of the earliest TikTok videos garnered 4.4 million views. The creator was Lin JJ. She imitated the lines of Ruan Yuejiao with a Vietnamese accent and also the gesture of emphasizing the breast (Figure 6). Other female creators who used Lin JJ's original sound also replicated the breast-emphasizing action.

Figure 6. Female TikTok creators emphasize the breast in their remade Ruan Yuejiao performances.

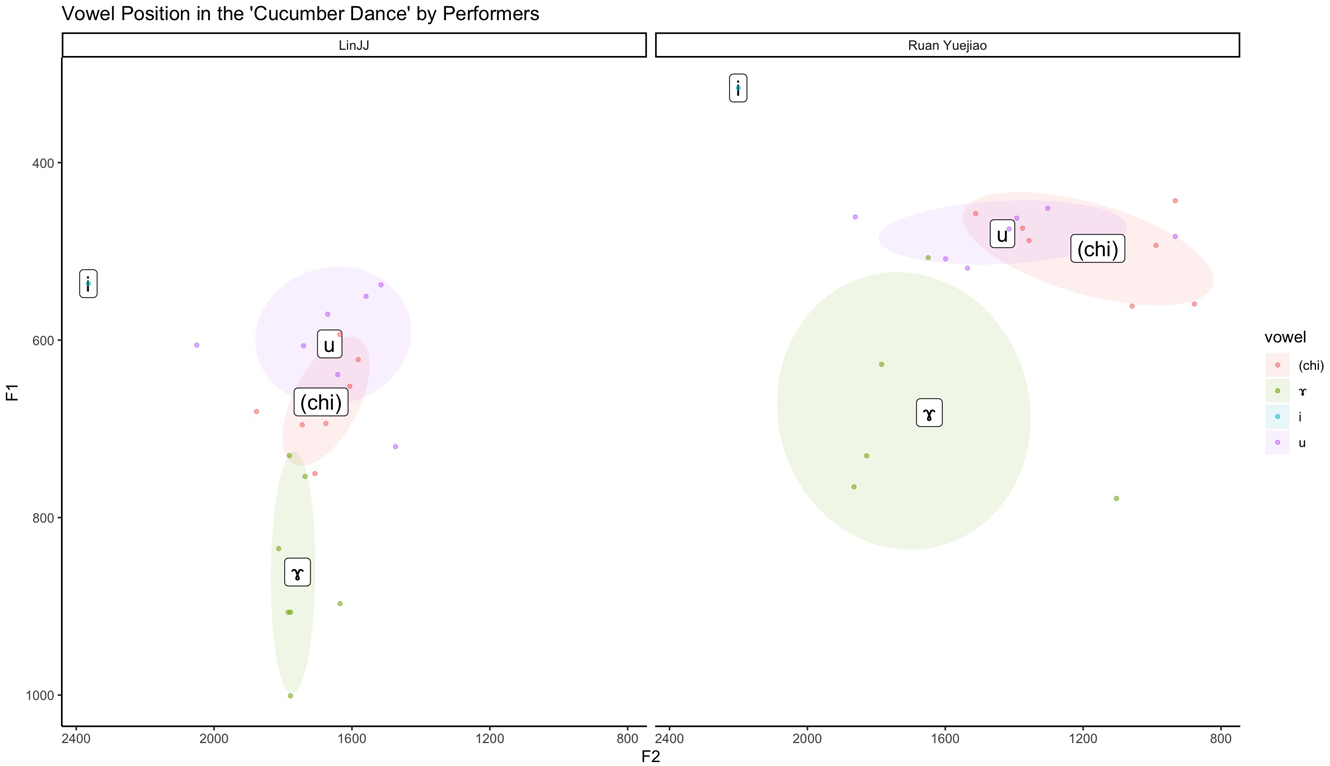

The hashtag used in relation to Ruan Yuejiao's performance reflected not only the repeated phrase but also the performed accent in that line. In A-Han's cucumber dance, all of the sentence-final T1 tokens were realized as T4, continuing the T1–T4 merger in portrayal of a Vietnamese accent. What is more important here is the vowel quality associated with the hashtag. The word cū means ‘large’ or ‘big’ in terms of circumference length, while bùcū means ‘not big’. The word hǎocū is an eye dialect of a socially recognizable way of saying hǎochī, which translates to ‘tastes good’. This socially recognizable /ɻ/–/u/ merger, where /ɻ/ is merged into /u/, is a linguistic stereotype (Labov Reference Labov1973) of Taiwan Guoyu, a Mandarin variety strongly influenced by Taiwanese Hokkien phonology, spoken by the elder generation, and associated with low education and lack of ideal femininity (Su Reference Su2018). Here I refer to the nucleus of the second syllable in hǎochī as the (chi) variable, using variationist denotation. During the performance, Ruan Yuejiao's (chi) was extremely backed, while her /u/ was centralized (Figure 7). As a result, the (chi) variable in hǎochī sounded like the [u] vowel in cū, creating a pun between big and eat. Wordplay, a signature of Ruan Yueijao, contributed to the highly sexualized nature of this performance.

Figure 7. Vowel positions of the two creators in performing the cucumber dance.

To locate how the vowel quality of the cucumber dance aligns with Ruan Yuejiao's usual performances, I extracted mid-point F1 and F2 values from /i/, /u/, and the (chi) tokens in all of the Ruan Yuejiao performances where the formant tracking was clear in Praat. These tokens were only examined when Ruan Yuejiao talked to the camera rather than her mother-in-law. /ɤ/ was extracted from the first line of each video, serving as a reference point for the high vowels. In A-Han's usual performances (Figure 8), there was no clear evidence of the /ɻ/–/u/ merger being used. In fact, the cucumber dance was derived from a specific context where Ruan Yuejiao accommodated towards her mother-in-law's Taiwan Guoyu when asking her to buy cucumbers. That is, the merger emerged in Ruan Yuejiao's linguistic practice of speaking Taiwan Guoyu.

Figure 8. Ruan Yuejiao's vowel positions in non-cucumber performances.

TikTok creators engaging with the cucumber dance decontextualized the accent depicted in the dance from its original context of creation. Ruan Yuejiao's Taiwan Guoyu speech was recontextualized as her Vietnamese accent. Social media is a site where linguistic styles can be rapidly reproduced, reorganized, and reperformed via internet memes. The style initiated by a certain content producer will inevitably be re-contextualized into new forms via a ‘collaborative enterprise’ (Chau Reference Chau2021), even associated with new social meanings in a very short time (Ilbury Reference Ilbury2022, Reference Ilbury2024). The positive social persona, intended by A-Han, was also absent in such collaborative enterprises, making Ruan Yuejiao a character that performed a highly sexually arousing dance with a silly helmet and sexually suggestive cucumbers.

Looking at details of Lin JJ's heavily used TikTok rendition reveals a raciolinguistic case of indexical inversion. While Lin JJ employed a T1–T4 merger, the /ɻ/–/u/ merger she performs was /u/ merged into the central high vowel. That said, the merger was recontextualized as an abstract phonological feature of the Vietnamese accent through TikTok imitation, with individuals realizing it in various ways. This is in line with indexical inversion (Inoue Reference Inoue2006), in that raciolinguistic ideologies produce ‘racialized language practices that are perceived as emanating from racialized subjects’ (Rosa & Flores Reference Rosa and Flores2017:628).

Vietnamese migrants: Ruan Yuejiao as a rude, lazy, and silly ribald

In 2022, Carrefour sparked controversy by featuring Ruan Yuejiao in their TV ad. This collaboration was published when Ruan Yuejiao had become an enregistered figure and after all of the online memetic recontextualization happened. The Vietnamese Club Taiwan (VCT), led by Trần Thị Hoàng Phượng, wrote a complaint letter to Carrefour. The opening of the letter is shown in extract (5).

(5) Bullying, under the guise of performance, is spreading unchecked. Every second of mimicking an accent is like a craft knife repeatedly slicing through the hearts of new residents and their children. All the efforts to assimilate and adapt are futile against the discriminating stigma of accent labeling!

VCT emphasized that accent imitation is a form of racism that diminishes the migrants’ efforts to assimilate. That is, accent imitation is a process of racialization which strengthens the divide between Vietnamese spouses and the Taiwanese majority through a racialized linguistic variety. For VCT, the accent mimicking is de facto Mock Vietnamese Mandarin, treating Vietnamese accents as an object of ridicule, and undermining the image of its indexed racialized group.

The debate over Ruan Yuejiao's character spilled over into personal reflections from the Vietnamese spouse community. Trần Ngọc Thủy, a radio host, critiqued the ad for its demeaning representation of Southeast Asian migrants, arguing that it is not just the accent that was problematic, but the entire portrayal of Ruan Yuejiao as idle, naive, and slovenly dressed. Social worker Yu-Fang Feng shared that Ruan Yuejiao's accent revived her past struggles with accentism, literacy, and assimilation in Taiwan. She also noted a growing unease with the character's risqué humor and apparent scorn for Vietnamese cultural norms, like the respect for elders.

Whether VCT and these columnists were cognizant of the TikTok memes is unclear, but it is evident they viewed the portrayal in the Carrefour ad as disrespectful. The Vietnamese accented Mandarin was not treated as any identity marker for them; instead, they wished the majority to see the effort they put into achieving their high Mandarin proficiency (cf. S. Lin Reference Lin2018). This highlights a discrepancy: while A-Han asserted he used the mediatized Vietnamese accent to affiliate with the Vietnamese community (first-order indexicality) and to overturn the obedient and industrious spouse persona, VCT contended that A-Han appropriated what can be understood as n + 1st indexicalities stemming from the negative associations of the accent, treating the Vietnamese accent as a jocular register (cf. Wong Reference Wong2024).

Taiwanese netizens: Vietnamese spouses as racists

Despite being a well-liked figure, one acknowledged by both the government and multinational corporations, neither the government nor Carrefour issued any public response to VCT's complaint. While Carrefour removed the ad, they did not apologize. In fact, the character's broad acceptance among the Taiwanese majority led to an outcry after the ad was removed, particularly targeting the leader of VCT. Her Facebook page became a battleground, amassing 885 comments.

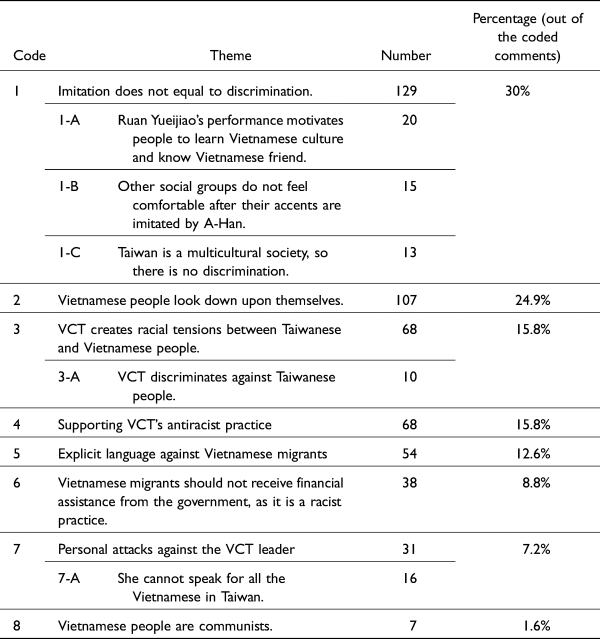

To portray the uptake of Ruan Yuejiao, it is essential to understand why these netizens were so frustrated with the action taken by VCT. A bottom-up thematic analysisFootnote 3 was conducted on these comments without imposing pre-existing categories. The analysis shows how the antiracist practice of Vietnamese immigrants was further racialized in the ear of the Taiwanese (Pak Reference Pak2023).

As shown in Table 2, the second most common theme is about how Vietnamese spouses belittle themselves. Under this theme, netizens argued that the only reason why Vietnamese migrants were angry about hearing a Taiwanese person imitate the Vietnamese accent was because they had internalized the racial hierarchy and thus had developed negative attitudes toward the Vietnamese accent. For example, the comment below reveals how this interpretation is possible.

(6) Code 1-C and 2

It is normal for Vietnamese people, who are not native Mandarin speakers, to have their own accents when speaking Mandarin. It is perfectly normal. … you are the one looking down on Vietnam by being so insecure about the Vietnamese accent in Mandarin. The people of Taiwan have made significant progress in terms of our cultural understanding. When I was in junior high school, there was a TV drama called ‘Don't Call Me a Foreign Bride Anymore’, and subsequent variety shows used the term ‘new residents’ to address everyone, aiming to promote greater ethnic inclusivity among the Taiwanese people. I believe Carrefour and A-Han are also on this journey, but it seems you are not! You are the one discriminating against yourself and those Vietnamese brides and workers who belittle themselves so much!

Table 2. Summary of the thematic analysis.

Comments like this hold a post-racial ideology, believing there is no racism in Taiwan. For example, in extract (6), post-racialism is manifested by an explicit mention of the shifting discourse about Southeast Asian spouses—from foreign brides to new residents, in line with the narrative of Ruan Yuejiao as well as the government campaign of multiculturalism (Lan Reference Lan2019). From this perspective, accent imitation is not seen as mockery but as a celebration of multiculturalism (code 1), suggesting that objections to the accent imitation are a form of anti-multiculturalism. Further analysis of the discourse (extract (7)) suggests that when Vietnamese spouses labeled the accent imitation as racist, the accusation inversely cast them as internalizing racism against Vietnamese people and discriminating against the broader Taiwanese majority. This narrative effectively shifts the onus of racism from the dominant group to the individuals who express discomfort with their cultural representation.

(7) Code 3

We can also say that you are discriminating against Taiwanese because ‘no matter what you do, you are discriminating against Vietnamese’.

This situation resonates with the case study by Pak (Reference Pak2023) on the ‘state listening subject’ in Singapore. Indian Singaporean rappers criticized a TV ad, due to the portrayal of a Chinese actor in brownface as an Indian character. The criticism was seen by the government as racially offensive towards the Chinese majority. The government's stance was that these rappers, by adopting American anti-racist rhetoric, were exacerbating racial tensions in Singapore. In Taiwan, however, the government did not appear to engage directly with the VCT protest, despite its previous collaboration with Ruan Yuejiao. Instead, it was the Taiwanese public that assumed the role of defending against the VCT's claims of racism, seeing A-Han as representing the Taiwanese majority. These viewers exhibited raciolinguistic listening and reinterpreted VCT's actions as an attack on Taiwanese people. This self-appointed role of ‘checkpoint guards’, as described by Milani & Levon (Reference Milani and Levon2019), positioned these netizens as arbiters who scrutinized and potentially silenced the expressions of migrants that were deemed as threats to national harmony or even security, which is evidenced in subsequent comments within the discourse.

(8) Code 8

Are you the

Vietnamese version of the Chinese Communist Party? Too controlling.

Vietnamese version of the Chinese Communist Party? Too controlling.(9) Code 7-A and 8

Taiwan is a democratic country! Not a communist country like Vietnam! The opinion of a few does not represent all! Have you consulted other Vietnamese people?

In extracts (8) and (9), anti-racist efforts are seen through a lens of political suspicion, associated with external ideological threats like communism, which has historically been considered a challenge to Taiwan's security and democratic framework. The use of the Vietnamese national flag (extract (8)) reinforces the perceived foreignness of Vietnamese migrants in Taiwan, suggesting a clear distinction between Vietnamese and Taiwanese people. This mode of raciolinguistic listening preserves a social hierarchy by preventing the integration of racial minorities into the national narrative in a way that could challenge the existing racial dominance.

Discussion

The discussion of how Ruan Yuejiao's character was perceived can be dissected on two levels: at the micro-indexical level, the focus is on the linguistic features used in the character's portrayal and how these features undergo a chain reaction of reinterpretation and recreation among different stakeholders. Then, at the macro-indexical level, the focus is on the broader implications of the raciolinguistic enregisterment and how the pushback against the mediatized and racialized personas contributes to a broader understanding of raciolinguistics and indexicality.

Micro-level indexicalization

This study examined A-Han's portrayal of Ruan Yuejiao, which utilized linguistic features to perform membership within the Vietnamese community. The discursive strategies served as contextualization cues (Gumperz Reference Gumperz1982), highlighting Ruan Yuejiao's alignment with the stigmatized ‘past’ of Vietnamese spouses in Taiwan. In the construction of the character, phonological features employed are not necessarily features of L2 Vietnamese speech. What was extracted from the indexical field of those features was a general concept of ‘speech errors’. The uptake of L2 speech errors in mediatizing a Vietnamese accent is powered by the metonymic nature of indexicalities (Kristiansen Reference Kristiansen, Dirven, Frank and Pütz2003), enabling a chain recreation to earlier indexicality. Unlike semantic metonymy, which can directly invoke a specific referent—as ‘White House’ can refer to ‘US president’—indexical metonymy operates on contingency and lacks exclusivity in reference (Kristiansen Reference Kristiansen, Dirven, Frank and Pütz2003). This concept underpins Eckert's (Reference Eckert2008) notion of the indexical field, suggesting that linguistic variants can signify a variety of social traits, some of which may be in conflict. Likewise, a linguistic feature is also just one of many attributes cognitively associated with a social group. When the feature is cognitively activated due to the social group being activated, other indexicalities (e.g. Wan Reference Wan2023) or linguistic features may also be activated.

The enactment of a Vietnamese accent relied on the metonymic link between Vietnamese spouses and L2 speech patterns (Figure 9). L2 Mandarin features, regardless of their socially realistic associations, were all candidates that could cognitively foster the mediatization of a Vietnamese identity as a L2 Mandarin speaker. It was the composite of L2 speech variants, rather than individual ones, that shaped the racial otherness of a Vietnamese spouse. In addition, suprasegmental features, particularly the T1–T4 merger, emerged as a prominent linguistic stereotype of Vietnamese identity in Ruan Yuejiao's character portrayals across various media, signaling to listeners that the L2 Mandarin speaker is Vietnamese rather than any other racialized identity.

Figure 9. The cognitive model of Ruan Yuejiao's racialized accent.

In the uptake among online creators on TikTok, the performance was built on an activation of an abstract concept of social or linguistic traits. One example was the abstract indexical of L2 learners, with any L2 speech feature embodying this indexical. The other example was the abstract phonological merger. In the original video where Ruan Yuejiao talked about the size of cucumbers, she merged /ɻ/ into /u/ to converge towards her mother-in-law's Taiwan Guoyu. In the Instagram story, the merger was decontextualized from the dialogue and became only co-present with Ruan Yuejiao, a Vietnamese spouse character. From a cognitive viewpoint, Ruan Yuejiao, as an enregistered figure, functioned as a sign and created a social perception of Vietnamese identity; in the meanwhile, her /u/–/ɻ/ merger functioned as a sign as well and evoked a social perception. The merger did not exclusively evoke an indexical of Taiwan Guoyu speakers. Instead, within the fifteen seconds of the Instagram story, it evoked an indexical of L2 speakers via the abstract concept of speech errors. The two indexicals—Vietnamese spouse and L2 speakers—blended in cognition and formed a third indexicality (Kristiansen Reference Kristiansen, Dirven, Frank and Pütz2003): the merger became perceived as a linguistic stereotype of Vietnamese accent (Figure 9). As a linguistic stereotype, in the uptake, the merger was circulated as an abstract phonological process, rather than specific phonetic properties, leading to the /u/ merging into /ɻ/ in other online creators’ adaptions of the Vietnamese accent.

Macro-level indexical hijack

These cognitive associations did not occur in a social vacuum. The above micro-level indexicalization was embedded within the racial context of Taiwan, where the Taiwanese majority has unilaterally shifted the discourse surrounding Southeast Asian spouses. Previously characterized by negative racial stereotypes, this discourse has abruptly transformed into one that extols multiculturalism and celebrates racial diversity, a shift that appears to align with the geopolitical needs of the state.

Ruan Yuejiao's character construction and its reception by content creators involved linguistic features that might be heard as L2 speech errors. Initially, these occurred in A-Han's portrayal without visual context. Later, the indexicality of speech errors re-emerged in different phonological forms through the rapid digital enregisterment of Vietnamese migrants on TikTok, underscoring a persistent perception of Vietnamese spouses as the racialized other. Indexicality varies, depending on who performs the perception/listening (Calder & King Reference Calder and King2022). For the Vietnamese community, mimicking a Vietnamese accent was seen not as a benign cultural reference but as a form of racism. The migrants also perceived L2 speaker identity to be indexed by those features. Yet, the L2 speaker identity did not index a marker of Vietnamese identity, as was proposed by the Taiwanese majority, as much as it evoked a history of racial otherization and the concomitant efforts by the Vietnamese community to overcome it and claim autonomy through Mandarin language classes (S. Lin Reference Lin2018; M.-C. Lin Reference Lin2019).

In the case of Ruan Yuejiao, the accent or the persona that was activated by A-Han and other online creators was not deracialized; instead, they were re-racialized. That is, through Ruan Yuejiao's performances, the racial stereotypes associated with Vietnamese spouses underwent indexical bleaching (Squires Reference Squires2014) in the ear of the Taiwanese majority. However, instead of simply stripping the accent of those racial stereotypes, the process involved reassigning a set of new, ostensibly positive indexical meanings to it, that is, through the process of indexical inoculation (Silverstein Reference Silverstein2023). Even though interpreted as positive by the Taiwanese majority, that is, the listening subject, these indexical meanings reinscribed racial stereotypes. Indeed, the interpretations of the Taiwanese majority were supported by a belief in post-racial multiculturalism, which framed the mimicking of accents as a celebration of diversity, rather than an act of racism.

In a similar context, Go (Reference Go2024) examined how Michelle Chong, a Singaporean actress, represented Filipino domestic workers through racialized English accents and grammatical features. Go noted that while Chong's portrayals might be well-intentioned and could help the audience understand the various responsibilities and challenges faced by migrant workers in Singapore, the use of racialized English accents in the performance perpetuates the continued subordination of Filipino English. Moreover, the ‘social and political structures’ that limited how Filipino workers could represent themselves in the Singaporean public sphere remained unacknowledged, rendering ‘her use of mock language ambivalent’ (2024:47).

In this article, I developed the concept of indexical hijack to further explore how an ‘ambivalent’ parodic representation of racialized linguistic varieties can be inherently problematic from the outset due to power asymmetry, even when ‘well-intentioned’. I showed additionally how post-racialism is one type of ‘social and political structure’ that obstructs the recognition of the violent nature of indexical hijack. This situation of indexical hijack differs from other forms of indexical bleaching one finds in linguistic or cultural appropriation where appropriators typically do not intend to preserve the original association with the group that owns the language or culture, but instead repurpose it for their own sociosemiotic goals, such as when white youths adopt elements of black youth slang without an association to black youth culture (Bucholtz Reference Bucholtz2010) or white speakers use Mock Spanish while lacking affiliation with a Spanish-speaking population (Hill Reference Hill1998). Here, the character Ruan Yuejiao was crafted to claim an affiliative identity with the Vietnamese spouse community, and the creator aimed to challenge racial stereotypes on the behalf of this community. In other words, indexical hijackers do not target the linguistic variety itself, but rather the authority to interpret the indexicality of the variety being seized, given that the indexical interpretation made by the minority group is overlooked or even suppressed. While the racialized group—Vietnamese migrants—perceived the repurposed racialized accent as a continuation of negative stereotypes, this interpretation was not ‘authorized’ by the dominant listening subject, which instead manipulated the racialized group as to question their own sanity. The term authorize is used here to indicate control over the indexical field associated with the Vietnamese accent by the Taiwanese majority.

The dominant group asserted paternalistic knowledge about what was beneficial for the racialized minority, denying them agency over their own sociolinguistic representation and interpretation. Even though the Vietnamese community could interpret their accent's indexicality within their group (for example, among the Vietnamese migrant columnists), they were denied the authority over indexical interpretation in the broader semiotic landscape. Moreover, post-racialism obscured the violent nature of racism underlying indexical hijack in this case, preventing it from being recognized. That is, the racialized migrants experienced racial gaslighting (Abu-Laban & Bakan Reference Abu-Laban and Bakan2022), where any negative indexicality perceived by the Vietnamese community in the portrayal of their accent was dismissed as a self-inflicted form of racial bias. In the discourse of post-racial multiculturalism, racism is reinterpreted not as a structural socio-economic disparity but as an individual psychological issue. Rather than avoiding discussions of race, this ideology emerges within neoliberal multiculturalism (Lan Reference Lan2019), which recognizes, acknowledges, and accepts racialized individuals as multicultural subjects, ‘based on an ethos of self-reliance, individualism, and competition, while simultaneously (and conveniently) undermining discourses and social practices that call for collective social action and fundamental structural change’ (Darder Reference Darder2012:417). As a result, collective actions, like those initiated by Vietnamese Club Taiwan, were diminished through raciolinguistic listening and instead labeled as a collection of individual racist minds.

Conclusion

This article examined a specific case of raciolinguistic enregisterment within the dynamics of Vietnamese spouse representation in Taiwanese social media, where the Taiwanese majority's racialized discourse reflected state-led geopolitical propaganda. I developed the concept of indexical hijack to anchor the process in which the majority imposes new indexical meanings upon assembled linguistic features that construct a racialized minority accent, de-authorizing the perspectives of the minority group. In this study, this process was made possible within a post-racial framework, where the majority claimed positive affiliation with the minority and framed the mediatization of the racialized variety as being in the minority's best interests. The majority then denied the minority's accusations of racism and further reinterpreted any backlash from the minority as internalized racism. This study contributes to the developing field of raciolinguistic research in Asia (Park Reference Park and Lee2022; Pak Reference Pak2023; Go Reference Go2024), offering insights from an East Asian context where racial considerations manifest in ways that are absent of explicit whiteness (Wong et al. Reference Wong, Su; and Hiramoto2021).