Bullying has pernicious effects on individuals and society at large. The empirical evidence has associated bullying with negative mental health outcomes bidirectionally for both victims and perpetrators.Reference Gaffney, Farrington and Ttofi1-3 In the year 2017, a of around 20% of students in 12 to18 age group reported an incident of being bullied and contrary to earlier beliefs it more prevalent in lower grades as compared to the higher grade levels.Reference McLain4 There are many high risk groups which includes lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) students.Reference Gaffney, Farrington and Ttofi1

In the year 1999, there were two critical events the Columbine High School shooting and a landmark US Supreme court order ruled that schools can be held accountable for not intervening and preventing abuse against children in the schools.Reference Fein, Vossekuil, Pollack, Borum, Modzeleski and Reddy5, Reference Fein, Vossekuil, Pollack, Borum, Modzeleski and Reddy6 These events initiated statewide legislative actions. To date, almost all the states have passed laws on curbing school bullying with the state of Montana being the last one to join this list in the year 2015.7 However, the impact of these laws is unclear.

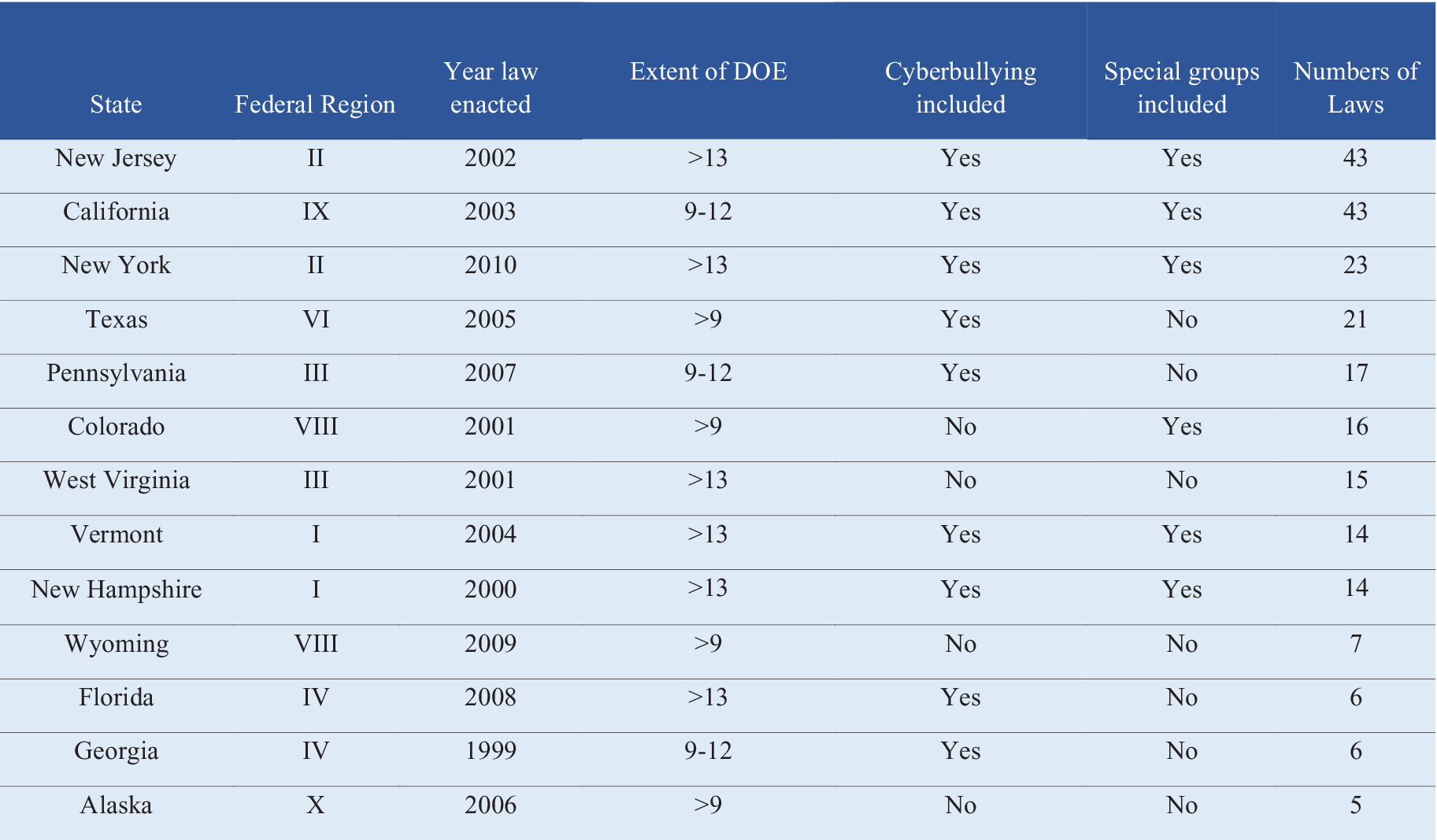

The Department of Education (DOE) in 2010 provided a comprehensive list of 16 recommended components to be a part of robust antibullying state laws (Figure 1). Some of these laws are quite expansive and some provide quite a lot of autonomy to the states to adapt and update their respective laws. Reports suggested that on average all the US states complied with 12.68 recommendations out of the total 16. The DOE has suggested including a list of 10 components to govern the definition of bullying through the state antibullying laws. However, only seven states have included these 10 components in their respective definitions. The DOE suggests that the scope of bullying covered by the antibullying laws should encompass the student’s behavior at school and school events irrespective of the site, on transportation provided by the school, and through technology pertaining to the school. Clear inclusion of the scope has been a part of only 25 state laws.

Figure 1. The States by Federal regions and initial year of enactment of antibullying laws. The extend of compliance with the Department of Education (DOE) 16 recommendations for antibullying laws. The variance among states regarding the inclusion of cyberbullying and special groups with 10 features such as ethnicity, color, religion, ancestry, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, socioeconomic status, physical appearance, and disability. And finally, state-wise current number of laws covering bullying.

Although many US states does not distinguish between bullying and harassment; but nine states have separate laws for them. The cyberbullying has been prohibited through provisions in education related laws in 36 states across the country. In North Carolina, bullying under 18 years of age is punishable by law as a misdemeanor. In New York, The Dignity Act (2012) requires school districts to include a policy to prevent discrimination, bullying, and harassment from kindergarten to grade 12.8 The criminal code of Idaho very explicitly defines and prohibits both physical and cyberbullying. The Golden Rule Act of Kentucky amended both the education code as well as the criminal code to incorporate provisions pertaining to bullying and harassment. In Virginia, bullying is liable for up to a $2,500 fine or a year in jail. In Massachusetts, in an unprecedented lawsuit and trial, five students were held liable for bullying and for the subsequent suicide of a fellow student. These students were charged with criminal and civil rights violations including harassment and assault. They were given probation and mandatory community service.Reference Smith, Mahdavi, Carvalho, Fisher, Russell and Tippett9

There are 13 states that provide schools with the authority to monitor and intervene on and off campus acts of bullying that lead to disruptive school environment.Reference Nishioka, Coe, Burke, Hanita and Sprague10 There are no clear instructions available through DOE on the implementation of state bullying laws in private schools or the development of these laws by the private schools themselves. Only six states, including Illinois, Iowa, Maryland, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Vermont forbid bullying both in public and private schools. The DOE also recommends formulations of antibullying laws to consider the 10 features such as ethnicity, color, religion, ancestry, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, socioeconomic status, physical appearance, and disability. These have been suggested as most bullying crimes are perpetrated against marginalized communities. Four states including Louisiana, Maine, New York, and West Virginia, did not have a clear definition for bullying and considered it comparable to aggression. The state laws in three states, Georgia, Kansas, and Washington have limited their definitions of bullying to activity associated with physical injury or damage to someone’s private property. Some states use terms such as threatening, intimidating, hostile, or offensive to describe acts associated with bullying in the school environment.Reference Sabia and Bass11

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2012) initiated portal Stopbullying.gov as recognition of a serious public health problem. The “It Gets Better” Project (2010) provided tools to at risk youth and those being bullied; specifically LGBTQ community.Reference Wang, Iannotti and Nansel12 The Olweus Bullying Prevention Program (OBPP) focuses on both short and long-run modifications that will enable a safer school environment. The aims of the OBPP are to decrease current bullying issues among students, avert novel bullying and attain healthier peer relations.Reference Glew, Rivara and Feudtner13

A cross-sectional observational study that evaluated the effectiveness of antibullying legislation in 25 states, but despite the variations, they concluded that the policies were effective in reducing students’ risk of bullying in schools. There was a 24% reduced odds of reported bullying, and a 20% reduced odds of cyberbullying for children in states with at least one DOE legislative component in their antibullying laws and policies.Reference Hatzenbuehler, Schwab-Reese, Ranapurwala, Hertz and Ramirez14 Similarly, Sabia and Bass assessed the impact of antibullying laws using data from the Youth Risk Behavior Surveys (YRBS) from 1993 to 2013, along with the Uniform Crime Reports.Reference Sabia and Bass15 State laws that mandate school districts adopt stringent, inclusive antibullying strategies are related to a 7% to 13% decline in school violence and 8% to 12% decline in bullying. Additionally, the stringent policies led to a substantial decline in shootings and violent crimes in school. However, there is little to no evidence on the positive impact of these laws on the likelihood of missing school due to the unwelcoming and hazardous school environment or weapons connected to threats. These findings are supported by statistical results that archetypal antibullying laws are associated with only a 3% to 5% decrease in the odds of being bullied at the school campus and strictly enforced laws are required.Reference Nansel, Overpeck, Pilla, Ruan, Simons-Morton and Scheidt16

A study using the 2015 YRBS survey assessed the leading feature connected with lesser rates of bullying, cyberbullying, and suicidal tendencies among the LGBTQ community. The State Equality Index (SEI) which is a comprehensive state-by-state analysis of several policies and legislations for LGBTQ+ people were also considered. It was found that among other strict policies in the states, the overall pledge to LGBTQ equality had a substantial effect in creating a positive impact. Based on the statistical analysis, it was seen that suicidal thoughts amongst LGBTQ youth reduced significantly by around 7 points, and cyberbullying decline by almost 6 points for each increase in the state’s SEI ratings (P < .05). Overall, it was observed that states with laws favoring equality amongst LGBTQ youth-led to lower bullying rates in school districts and campuses.Reference Nishioka, Coe, Burke, Hanita and Sprague10 The anticyberbullying laws led to 7% decline in the likelihood of being victimized by cyberbullying, through any medium (ie, emails and chatrooms). Through another method the authors used the instrumental variables approach the study established that cyberbullying is related to considerable upsurges in suicides and suicidal tendencies.Reference Fox, Elliott, Kerlikowske, Newman and Christeson17

A study using YRBS 2015 data found that these state antibullying laws were associated with reductions in bullying, depressive episodes and completed suicides, these reductions were greatest amongst female youths and the LGBTQ community. These laws were also associated with a 13% to 16% decline in suicides among adolescent females in 14 to 18 years age group. Proper implementation of these state laws led to around 0.017 decline in the likelihood of bullying of female teenagers. This translated to an average 8% decrease in relation to the mean. Amongst the male population, this led to a 0.021 decline in possibility of bullying translating into a 12% decrease relative to the mean.Reference Wang, Iannotti and Nansel12

Another study included 6th, 8th, and 11th-grade children who had completed the 2005, 2008, and 2010 Iowa Youth Survey. These students were provided a code based on their exposure to the antibullying laws: pre-law for survey data before 2005, 1-year post-law for 2008 data, and 3 years’ post-law for 2010 data. A generalized linear mixed model was formed with random effects. It was observed that the likelihood of being bullied rose from pre-law to 1-year post-law periods, and then decline from 1 year to 3 years post-law. This decline however was not lower than 2005 pre-law. It is likely that the rise in bullying immediately after the passage of the law was due to increased reporting.Reference Ragatz, Anderson, Fremouw and Schwartz18 In a study conducted to assess the effectiveness of antibullying programs, the response from students was recorded to highlight the weakness and strengths of these programs as viewed by the students. It was observed that students did not find general repetitive presentations, direct negative message and posters promoted by teachers on antibullying very effective in tackling the problem at hand.Reference Cunningham, Mapp and Rimas19

Given the serious nature of problem and limited evidence, it is imperative that the verdict is still out if antibullying measures are truly effective. The bullying menace, which affects one in every five children, has hidden costs with its long-term effects on mental health and burden on healthcare.

Disclosure

The authors do not have anything to disclose.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: M.G., N.G.; Data curation: M.G.; Funding acquisition: M.G.; Methodology: N.G.; Writing—original draft: M.G.; Writing—review and editing: N.G., V.D.