Claude Pepper had a long career in the US Congress, serving as a Florida senator from 1936 to 1951 and as a representative of Miami from 1963 until his death in 1989. The very first line of his obituary in the New York Times referred to him as a “former United States Senator from Florida who became a champion of the elderly in a career that spanned 60 years.” These sorts of characterizations continued throughout, both in memorializing quotes from others as well as in descriptions of his work within the legislature:

“Claude Pepper gave definition and meaning to the concept of public service,” the President [George H.W. Bush] said. “He fought for the poor and the elderly in his own determined way.”

Horace B. Deets, the executive director of the American Association of Retired Persons, said it would be difficult to find an advocate for the rights of older Americans who could replace Mr. Pepper. “There really isn’t anyone on the American political landscape who could step into Claude Pepper’s shoes,” he said. [ … ]

From 1929, when he first entered politics, until his death, Mr. Pepper fought for the rights of the elderly. One of his first acts in the Florida House of Representatives was to sponsor a bill that allowed older residents to fish without a license. And as he grew older Mr. Pepper continued to wage war against those he considered willing to take advantage of the elderly. At the age of 78 he voted for a law that raised the mandatory retirement age to 70 from 65. [ … ]

In 1977 Mr. Pepper was named chairman of the House Select Committee on Aging, soon becoming known as ‘Mr. Social Security’ for his ardent defense of Social Security and Medicare. He built a national reputation as the primary Congressional advocate for the elderly, introducing legislation to fight crime in housing projects for the elderly, to cut Amtrak fares for senior citizens and to provide meals to invalids. [ … ]

Mr. Pepper’s stands on behalf of the elderly did not hurt him in his own district, where 30 percent of adults are at least 65 years old. Over the last decade, he consistently won re-election with more than 70 percent of the vote.

In the special election following his death, the 18th District of Florida elected Ileana Ros-Lehtinen to be the first Latina to serve in Congress. She subsequently won all of her reelection battles, and in the spring of 2017 announced her intent to retire at the end of the term. A piece in the Miami Herald describing her tenure in Congress discussed her consistent emphasis on foreign affairs, particularly in regards to Cuba, as well as her longtime advocacy for the LGBTQ community. The author writes:

“For years, Ros-Lehtinen represented the Florida Keys, including gay-friendly Key West, and advocated for LGBTQ rights – far ahead of much of the GOP. Eventually, her transgender son, Rodrigo Heng-Lehtinen, made his way into the public spotlight; last year, he and his parents recorded a bilingual public-service TV campaign to urge Hispanics to support transgender youth.”

In both cases, these individuals are described in terms of their legislative reputation. In particular, their work in Congress is defined by their broad efforts on behalf of specific disadvantaged groups. Describing a member’s reputation is used as a way of summarizing a member’s work within the legislature in a way that is easily understandable. Notably, member reputation is used as a concept that is distinct from any one particular action such as bill sponsorship, and distinct from group presence within a district. When specific actions are mentioned, such as Sen. Pepper’s efforts to allow seniors to fish without licenses or to address crime in housing for the elderly, they are included to give examples of the work that went into building this reputation, rather than the critical factors in and of themselves. Additionally, while the importance of district composition is made clear by emphasizing the relatively high level of senior citizens and the presence of the Key West’s large LGBTQ population within the district, sizeable district presence alone is not synonymous with legislative reputation. If it were, one would expect both members to have formed very similar reputations, as Reps. Pepper and Ros-Lehtinen represented roughly the same district, but this is not the case.

This book seeks to deepen our understanding of the representation that disadvantaged groups actually receive in the US Congress. Specifically, it pursues an understudied conduit of representation by exploring when and why members of Congress seek to build legislative reputations on behalf of disadvantaged groups. But before the when and the why can be explored, one must first focus on the what. Chiefly, what exactly is a legislative reputation? In this chapter, I lay out a specific definition for what a legislative reputation is, along with its requisite characteristics. I then make a case for why legislative reputations are so important for representation, and why members seek to craft them. Finally, I describe the source material and coding scheme for my original measure of member reputation, and present descriptive statistics on the members that do cultivate reputations as advocates of disadvantaged groups.

3.1 What Is a Legislative Reputation?

The concept of a reputation is one that is familiar and frequently used in common parlance, but the precise elements that make up a reputation can be hard to pin down. Despite this, scholars and journalists alike tend to treat a member’s reputation as an important way of understanding their behavior within the legislature. Much like the terms “maverick” or “political capital,” member reputations are commonly referenced but rarely thoroughly defined.

There are a few exceptions that make notable contributions to a holistic understanding of what a legislative reputation really is. Reference SwersSwers (2007) highlights the benefits conferred upon members with a reputation as an expert in national security in the post-9/11 world and explores the gender-based differences in where members focus their reputation-building efforts. Reference FiorinaFenno (1991) explains that to establish reputations as effective legislators, senators must work both within the legislature to pass bills and on the campaign trail to bring it to constituents’ attention. Schiller (2000a) argues that “the requirements for successful reputation building … [are] media attention and constituent recognition.”

Each of these authors offers important pieces to the broader puzzle of what makes a legislative reputation. Fenno emphasizes that reputations come from intentional efforts on the part of members that depend upon their communication to constituents, while Schiller develops this further by conceptualizing member reputation as part of a two-way communication with media as an essential arbiter. Swers highlights the nuanced differences in how members craft their reputations, even within the same issue area. She also offers insight into the linkage between a member’s descriptive characteristics and attempting to build credible reputations.

At its simplest, a member’s legislative reputation is what they are known for prioritizing and spending their time working on while in Congress. This is a definition that leaves a great deal of latitude, both in terms of the subject matter and the means of acquisition. For example, in considering the applicable subject matter for this project, I am particularly interested in reputations that are crafted around advocating for particular constituent groups. However, reputations can also be built around other aspects of legislative work, such as being a deficit hawk or attending to foreign affairs in Eastern Asia. Similarly, there are a vast number of different ways that members can “work on” issues they consider to be important. So, if legislative reputations are not just set lists of topics or behaviors, what are they?

I contend that a reputation has three essential components. First, reputations must be greater than the sum of the individual actions that contribute to them. Second, there is no single action that is required for a reputation to be formed. And third, reputations are the result of the observation and interpretation of others.

3.1.1 Emergent Properties

When biologists seek to define some of the principal characteristics of living organisms, one of the most important of these is that it possesses what are referred to as emergent properties. Emergent properties are present at all levels of biological structure and are responsible for important characteristics of life such as responsiveness to stimuli, reproduction, and evolutionary adaptation. Biological organisms are made up of an enormous number of different components that have various functions, but these elements then interact to fulfill something more than just their individual roles – the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. So too when thinking about what makes a legislative reputation. It is not simply votes cast, bills proposed, or speeches given. It is the distillation of what this individual is about and what is most important to them.

A reputation cannot simply be taking specific actions or saying specific words. Rather, it is the culmination of a number of different actions that then interact to form a broader picture. One can step outside of the political realm to get an intuitive sense of how this works. You do not have to know where Mother Teresa practiced her ministry or be able to name any of her works of mercy to know of her reputation for working to serve the poor and the sick. To give an example familiar to children and parents of children from the 1990s, one need not remember any specific storylines or plot twists to feel confident in stating that Captain Planet’s top priority was protecting the environment. These reputations are built from a consistent series of actions that signal dedication to a particular cause or service to a particular group, that then take on a life of their own. They are connected to specific behaviors, but can also be broadly understood apart from them.

Member reputations take on a life of their own and stand for something more than just individual actions in and of themselves. They hold symbolic value as well, and can serve as a mark of trust and understanding that goes beyond that of other members. In the mid-2000s, Republicans created a commission to explore ways to reform Medicare and ensure its fiscal solvency. When they went to sell their proposed reforms, one of the most important things that they relied on was not a detailed recounting of their policy proposals, but rather the support of Michael Bilirakis (R-FL9).Footnote 1 Bilirakis was known as someone who looked out for the best interests of seniors, and Republicans argued that if he believed that their proposed Medicare changes would benefit older Americans, they could believe it too. His reputation as an advocate for seniors had value in and of itself, above and beyond any individual act.

3.1.2 Reputation Is Not Synonymous with Any Specific Action

This second property is related to the first – in the same way that a reputation is more than the specific actions and signals that go into its crafting, it also does not directly imply that any particular action on behalf of a group has been taken. There are a variety of ways that a member can represent the groups within their district, and all of them feed into a member’s reputation. But no one specific action – be it sponsoring a bill, speaking on the floor, or cosponsoring a number of bills to benefit the group – guarantees that a member has a reputation for advocating for the group more broadly. Similarly, knowing that a member has a reputation as a group advocate does not mean that you can predict with absolute certainty what legislative actions they will have taken.

This is a critical definitional element of a reputation for two main reasons. First, it takes into account the amount of discretion members have in terms of what they do, and how they do it. Reputations build over time as the result of a conglomerate of actions. But depending upon the member’s seniority, committee membership, position in the chamber, and their other group and issue priorities, they enact their group advocacy in different ways. For example, some members of Congress sponsor hundreds of bills in a given Congress, while others may introduce less than five. By not assuming that reputation means any one specific action, it takes into account this variation in the preferred means of representation. Second, it highlights the fact that members can take some of the same actions, with no guarantee that it will impact their respective reputations in exactly the same way. Just because members have similar cosponsorship records, for instance, does not mean that each will have the same reputation for group advocacy.

A member’s reputation goes beyond a set list of specific, predetermined actions. Reputation does not have inherent transitive properties. Members who engage in bill sponsorship or cosponsorship benefiting a particular group, or who serve on a committee with the potential to address their needs may have a reputation as a group advocate, but group advocates do not have to serve on particular committees or introduce some particular set of measures. While it may be true, for example, that someone who sponsors several bills pertaining to women’s health has built a broader reputation as an advocate for women, this does not mean that having a reputation for women’s advocacy is synonymous with just sponsoring a bunch of bills intended to help women.

In over three decades of time spent serving in Congress, first in the House and then in the Senate, Barbara Boxer cultivated a reputation as a formidable advocate of women, with a particular focus on women’s health. The vast majority of the bills she sponsored, however, came in other arenas, including national security, international affairs, public lands, environmental protection, and government operations.Footnote 2 Of the forty-one measures signed into law over the course of her career for which she was the primary sponsor (an impressive total), only five were directly related to women. Four of these were joint resolutions from the mid-to-late 1980s designating Women’s History Week and then Women’s History Month, and the last came in the 114th Congress, in the form of a bill designed to enhance suicide prevention efforts for women veterans. But this rather narrow record of formal legislation sponsored and enacted to benefit women does not mean that her reputation was unfairly bestowed, or that this reputation for advocacy had limited substantive effect. Instead, her impact came in ways that could be missed if one only looks to routine measures like bill sponsorship alone. She fought against any efforts to restrict women’s access to preventative medical care and abortion access, offering amendment after amendment to this effect during her tenure. Boxer also engaged in less traditional or easily counted forms of representation, including frequently speaking out in defense of Planned Parenthood, publishing op-eds on women’s healthcare with other female lawmakers, pushing for the resignation of members credibly accused of harassment against women, and, most famously, leading a group of women Representatives from the House in a march over to the Senate side of the Capital in protest of the treatment of Anita Hill during the Clarence Thomas hearings.

Members of Congress can be creative in the ways that they choose to represent their constituents. This is particularly true when considering the representation of disadvantaged groups, especially those who are less well regarded by the public as a whole. Majority coalitions can be difficult to build for measures seen as benefiting less popular groups. Thus, representation for these groups may be less likely to take the form of trying to pass immediate, big ticket legislation and more focused on the overtime work of coalition building and elevating disadvantaged-group members’ real lives and concerns. Rep. Shirley Chisholm, whose words opened the first chapter of this book, saw her role in this way. In discussing her time in Congress in her book, Unbossed and Unbought, she argued that her job was to help disadvantaged and marginalized people to “arouse the conscience of the nation and thus create a conscience in the Congress” whether by traditional legislative means or by any other avenue her platform and the resources available to her could provide.

3.1.3 The Eye of the Beholder

Finally, one of the primary characteristics of a reputation is that it inherently must be interpreted by others. There are a variety of things that can be done to shape a reputation, but ultimately, it is in the eye of the beholder. In the political world, that beholder most commonly is the media. Even the most politically engaged tend not to spend copious amounts of their time scouring the Congressional Record for every action their member took on the floor that day, or tuning in to endless hours of committee hearings on C-SPAN. Instead, individuals depend upon a variety of media sources to keep them updated on what their member is up to, with only occasional specifics. This can take a number of different forms: who the media quotes on a particular topic, pieces that do a deep dive into actions that have been taken on a salient policy topic, reports on a member’s town hall, or candidate biographies and descriptions that are published to prepare voters for an upcoming election. These are distilled down from a huge quantity of member actions and positions, and once a reputation is established, it tends to be reinforced by other members of the media as well.

In the lead-up to the 2012 election, Mitt Romney declared that he had been a “severely conservative governor” of Massachusetts. The former presidential candidate was widely mocked for this statement, as it did not comport with the narrative surrounding his time in office, where he was generally described as compiling a moderate record. He did take a number of what could be considered “conservative” actions while serving as governor, but that was not the interpretation that had been drawn by the media and others who had examined his history. Conversely, in the Democratic primary campaign of 2015 and 2016, Bernie Sanders routinely described himself as the candidate of the working class, with very little pushback. This self-assessment was congruent with how the Senator tended to be described by the news media, and thus served to reinforce the reputation that had already been developed.

These examples illustrate the fact that one’s reputation cannot simply be declared to be whatever one would like it to be – it must be drawn by the consensus of others who observe that person’s behavior over time. Obviously, this is not to say that a person has no control at all over their own reputation, because they most certainly do. Individuals can take any number of actions in an attempt to craft and shape their own reputation. Many of the behaviors that a member of Congress engages in are designed to send important signals about their priorities and the work they are doing. But these behaviors must be interpreted by others – primarily the media – rather than simply claimed by the member themselves.

Because reputations rely upon outside determinations, they are also self-reinforcing. This can happen in two ways. First, if some members of the media repeatedly reference a member of Congress in particular ways, this can get picked up by other reporters and other news outlets as well, until there is a broad understanding of what the big pieces of a member’s reputation generally are. Second, when reporters are seeking comment on particular issues, they generally want to ask a member who has experience and expertise on the topic. If a member gives an interview in which they spend a good deal of time discussing the challenges facing immigrants in this country or how pending immigration legislation might affect that group, they will get to be known as someone who can speak with authority on the issue, prompting other journalists to seek them out as well. This then has the effect of further bolstering a member’s reputation as an advocate for immigrants.

Because the reputation that is communicated to constituents is dependent upon this outside party assessment, it ensures that it will have at least a base level of face validity. Members of the media and other outside observers will only coalesce around a particular understanding of a member’s reputation if it is seen to be reasonably credible. Credibility generally requires that a member be considered to have a relatively high level of expertise, that they have taken at least some actions related to an issue, and that they have not taken actions considered to stand in opposition to an issue or group.

Strom Thurmond was one of the longest-serving politicians in American history, representing South Carolina in the US Senate for forty-eight years. Some of what he is best known for is his run for president in 1948 under the banner of the anti-civil rights States Rights Democratic Party, staging the longest filibuster in history against the 1957 Civil Rights Act, opposing all civil rights legislation over the next two decades, and changing parties in 1964 to protest the Democratic Party’s embrace of civil rights. In his later years in the Senate, he did make some overtures to his Black constituents, who by that time made up a sizable portion of the electorate in South Carolina. These small actions had little to no effect on his general reputation as someone who was certainly not an advocate for Black Americans and other communities of color, as they did not comport with the decades of strong evidence to the contrary.

A member’s credibility is most frequently considered to come from the study of issues under a committee’s jurisdiction, but it also goes beyond this. Some members also take reputation-building actions on issues that are not specific to their committee assignments. This is particularly common in the Senate, where senators are expected to be generalists, but can be true in the House as well. These instances also speak to the differences between legislative effectiveness and a legislative reputation. Working on issues relevant to the jurisdiction of the committees a member is on doubtless increases their chances of moving legislation through the process. But reputation formation does not rely upon success alone. Legislators can gain reputations as “squeaky-wheel” advocates, even if their proposed changes are rarely enacted.

A person’s personal, descriptive characteristics can also serve as a shortcut to credibility even without a committee-specific tie. For example, being a female member of Congress lends additional credence to their status as an advocate for women and women’s issues. This then makes it more likely that members of the media will approach them on these issues, thereby serving to amplify this component of their reputation. However, there are some instances, as demonstrated by Reference SwersSwers (2007), in which personal characteristics or demographics can make it a tougher climb to reach credibility. Jay Rockefeller, for instance, spent three decades representing West Virginia in the United States Senate. But, as a member of a famously wealthy family, Rockefeller had to put great effort into demonstrating his understanding of and compassion for the challenges facing the poor and elderly in West Virginia.

In summary, a legislative reputation is defined by three important characteristics. First, a reputation is essentially an emergent property – it is more than the sum of individual actions. Second, a reputation cannot guarantee that a member will have engaged in any one particular behavior. And third, reputations are translated through third-party observers. Next, I turn to why legislative reputations are important, and what drives members to attempt to craft them.

3.2 Why Do Members of Congress Seek To Build Legislative Reputations?

Members of Congress attempt to cultivate legislative reputations for a number of reasons, rooted in both their electoral concerns about communicating their priorities and achievements back to their constituents as well as the advantages that are conferred within the legislature itself. First, members want their constituents to know what they have been doing to represent them, but recognize that the vast majority of their constituents have extremely limited political knowledge about a member’s specific actions day to day. Working to craft a clear legislative reputation is a way to demonstrate a broad picture of their efforts, without counting on the transference of specific facts. Second, much of politics is rooted in group-based understandings, making reputations for group advocacy a common denominator of communication between members and constituents. Finally, to be effective in Congress, members know they have to play the long game. By cultivating reputations, members make it easier to claim legislative turf and build coalitions over time.

3.2.1 Limited Political Knowledge

At its most basic, the idealized representational relationship consists of an elected representative diligently working within the legislature to promote actions in the best interests of their constituents. These constituents then take careful note of the member’s behavior over the course of their term, and, if they feel that they have done a good job of working on behalf of the constituency, reward them with another term in office. In practice, this relationship is considerably more complicated. Despite an increase in transparency since the reforms of the 1970s, constituents do not have full information about what their representative is doing available to them. Even only considering the (still considerable) information that individuals can access, most nonetheless have extremely limited knowledge.

A member’s constituents tend to have no idea what their member is doing from day to day. This is not inherently a criticism – they cannot be expected to follow everything that a member does. Most citizens have lives and priorities that leave little time for in-depth explorations of what their member of Congress has been up to each day. Given the high cost of this information gathering and the limited personal incentives for any one person to engage in this process, it ought not to be surprising that levels of political knowledge and information are fairly low. Thus, in a political reality in which fewer than one-third of Americans can name one of their state’s senators (Reference BreitmanBreitman, 2015), it is unlikely that any given constituent will be aware of a specific action that a member of Congress takes. That said, even if a member cannot count on a sizable portion of their constituency to be up-to-date on the most recent amendment they proposed in mark-up or the bill they signed on to as one of the first cosponsors, it is reasonable to expect that those individuals paying at least some amount of attention to what’s going on in Congress and the political world will pick up on some of the broader trends about what their member is doing.

It is this general picture of themselves that members of Congress seek to control. As described in the previous section discussing reputation as inherently in the eye of the beholder, members of Congress do not have absolute control over their reputations. That said, they are very far from helpless. Members of Congress are exceedingly conscious of how their actions are perceived by others, and work to create a cohesive pattern of behavior. Members seek to build these reputations because of their simplicity and power to penetrate down to the constituent level. The likelihood of any one vote, hearing, speech, or bill introduced becoming widely known is extremely slim, but members are able to cultivate a broader reputation by repeatedly taking actions that contribute to the larger picture of advocacy for a specific group or toward achieving particular goals.

This is then reinforced by the media, both in the way that a member is described and in who the media seeks out for comment on particular issues. Given that member reputation is filtered down to constituents through the media, this reinforcement is particularly important. Once a member begins to develop a reputation with some sources within the media as an advocate for a particular group, this understanding will be repeated. This is true at the national level and at the local level. Members of Congress place a great deal of value on local news outlets, as they are frequently the sources that constituents pay the most attention to. But given that few local media outlets are able to send staff to Washington, there is a considerable amount of member action for which local media look to previous national reporting to shape their stories. Additionally, reporters and broadcasters sometimes actively seek out members to comment and speak to specific issues. Those who have a reputation as group advocates and experts on those issues are likely to be those who are sought out. This in turn further emphasizes that reputation, as media appearances are an important piece of the narrative.

3.2.2 Group-Based Understandings

While politics at the elite level are frequently talked about in terms of political ideology, at the individual level, people are far more likely to see politics as rooted in group identities (Reference Converse and ApterConverse, 1964). This means that a large percentage of people think about politics as coalitions of different groups, and their issue positions or partisan identification is directly related to what groups they support or feel connected to, and which groups they oppose or see as undeserving (Reference Griffin and NewmanGreen, Palmquist, and Schickler, 2002). Members of Congress also frequently see their districts as composed of groups and factions (Reference FennoFenno, 1978). They pay close attention to district demographics and other subgroup divisions when conceptualizing their districts and deciding what actions to take.

Member reputation as a group advocate, then, is a particularly helpful way of thinking about representation. It acknowledges the emphasis on group-based understandings that many constituents use when evaluating their representatives but also reflects one of the principal ways that members make decisions and take action within the legislature. This is not to say that all of politics is rooted in group affinity, or that group considerations are the only means by which members of Congress make decisions. But, it is one of the most common means that constituents and members alike use to think about the political world and political decisions, creating a place of overlap in how both representatives and the represented conceptualize representation.

3.2.3 Playing the Long Game

Member reputations also provide a boost to members over the long term when it comes to getting things done within the legislature. It is extremely rare that issues are raised, problems are understood, and solutions are proposed and adopted in the two years of a single Congress. Issues can take years to enter into the public consciousness, and some never will. Single pieces of legislation are introduced over and over, some with various tweaks but the legislative intent remaining the same. Members will give speeches addressing the same issues year after year. Hearings on issues left unaddressed in the prior Congress will be revamped for the next. In the overwhelming majority of cases, if members want to actually accomplish anything in Congress, they have to be prepared to play the long game. Working to establish legislative reputations assists members in that goal in two ways: aiding coalition building and establishing legislative “turf.”

Coalitions can be thought about in two ways. The first is of a majority coalition within the legislature. This involves bringing on board half of the members of the House or the Senate to legislation that is favored by a group or is meant to serve a group. These coalitions can be established either by getting other members to agree to act on behalf of a given group’s cause or by adding in provisions that would serve other groups or favored issues as well.

The second way of thinking about a coalition is one of affected parties and stakeholders outside of the legislature itself, either nationally or within a district. Coalitions of this sort are necessary both to determine what sorts of services or actions groups want and require, and also to gain buy-in from important entities that can communicate to other constituent group members. Building coalitions with groups in the district that work to end hunger, provide housing for the homeless, raise awareness of the EITC, or provide job training opportunities for struggling communities helps a member stay in touch with issues that are most important to low-income individuals, but also bolsters their own reputation as an advocate for the poor. In turn, having a strong reputation on these issues can serve as a signal to other potential community partners that a member can be trusted to work diligently on their behalf.

Members also seek to establish their own legislative “turf” as a means of communicating expertise and gaining prestige within the legislature. Specializing in particular issue areas has been a long-standing tactic in both the House and the Senate to increase a member’s influence within the legislature, and to reflect constituency needs (Reference Green, Palmquist and SchicklerGrant, 1973; Reference GambleGaddie and Kuzenski, 1996). Establishing a reputation as an expert and important operator on a specific issue increases the likelihood that a member will be able to play a major role in important legislation and gain higher visibility in the media on that issue. This then reinforces that reputation and boosts the likelihood that their efforts will be recognized by their constituents.

Having now defined legislative reputation as a concept, made a case for why reputation is an important means of understanding representation, and explained why members seek to cultivate a legislative reputation, I next turn to a discussion of how reputation can be measured.

3.3 Measuring Reputation

For this project, I have developed an original variable of reputation that quantifies which members cultivate a legislative reputation as an advocate for disadvantaged groups. As previously indicated, the disadvantaged groups under consideration are the poor, women, racial/ethnic minorities, the LGBTQ population, veterans, seniors, immigrants, and Native Americans. I created this legislative reputation variable by systematically coding the written member profiles found in Congressional Quarterly’s Politics in America for the 103rd, 105th, 108th, 110th, and 113th Congresses, all of which lie between the period from 1993–2014.Footnote 3 Utilizing these member profiles allows me to construct a reputation variable that takes into account the critical characteristics discussed earlier in the chapter – namely, that reputation is more than just a set of specific actions, and that it relies upon the interpretation of an outside observer. In the remainder of this section, I provide a description of Politics in America and its member profiles, make a case for using an “inside the beltway” resource like Politics in America to develop an innovative new measure for reputation, and give a precise detailing of how this reputation metric is operationalized.

3.3.1 CQ’s Politics in America

Congressional Quarterly’s Politics in America is a compendium of profiles of all members of Congress and their districts, published every two years with each new incoming Congress, starting in the 1970s. Each profile contains approximately two pages of text in addition to a sidebar listing biographical information such as place and date of birth, military service, education, and previous political office. The profile sidebar also contains several of the member’s interest group scores and record on key votes.Footnote 4 The heart of these profiles, however, comes in the two page narrative description of who a member is, and what a member has done. These narrative profiles are a combination of biographical information, descriptions of legislative priorities, highlights of past work within the legislature, and a short concluding section covering their electoral histories. The primary emphasis in these profiles is to give a robust sense of a member’s identity in Congress.

The relatively short length of these profiles is important, because it ensures that they are not simply a listing of all of the actions a member has taken on each and every issue position. Rather, they are a concise distillation of the most important elements of what a member has done, said, or intends to do. Though each profile does devote one or two paragraphs to narrating some biographical backstory or electoral intrigue, the vast majority of the profile is spent discussing what the member is known for within the legislature. Any additional biographical information that is included serves the purpose of explaining why advocating for particular groups or issues is so important to a member. This can range from highlighting how (now former) Rep. Mike Ross’ (D-AR04) career as a pharmacist drove him to push for controls on prescription drug prices for seniors to describing Rep. Ruben Hinojosa’s (D-TX15) experiences in segregated schools as a Spanish-speaking child as the catalyst for his work to promote educational equality for minority students.

It is common for members of Congress to serve for a number of terms. An important element of these profiles is that they account for the ways that a member’s reputation can change over the course of their career. While there is clear overlap in some of the content that is discussed in a member’s profile from Congress to Congress (as would be expected), the profiles are revisited and written anew for each term. This is important for three reasons. First, this is essential for ensuring that the information presented is up-to-date as of the contemporaneous Congress. Reputation building frequently takes time and is developed over a number of years, and this allows for new actions to be taken into account. Second, member profiles tend to be more heavily weighted toward recent actions, allowing for reputations to evolve over time. While members frequently exhibit a high level of consistency in the groups they advocate for, as discussed above, there are also instances in which members can shift their priorities or take up new causes. By updating for each new Congress, these changes can be incorporated. Finally, this also allows for the continuity for an individual member across sessions of Congress to be more organically derived. While each new writer undoubtedly references what has been written in the past, they are also at liberty to select new information to include or old information to drop based upon their interpretation of how best to describe a particular member. This process in and of itself also mirrors the process by which a member’s reputation is built, evolved, and reinforced through the eyes of the media.

In the introduction to the 13th Edition of Politics in America (detailing the members of the 109th Congress, which was in session from January 2005 to 2007), Editor and Senior Vice President David Rapp describes the process of compiling these profiles in the following way:

Congressional Quarterly, which has been the “bible” on Congress since 1945, sets out every two years to compile the definitive insider’s guide to the people who constitute the world’s greatest democratic institution. The book is organized so that each member’s “chapter” provides a full political profile, statistical information on votes and positions and a demographic description of the state or district a member represents.

We evaluate every member by his or her own standards. We do not try to decide where a politician ought to stand on a controversial issue; our interest has been to assess how they go about expressing their views and how effective they are at achieving their self-proclaimed goals.

The 125 reporters, editors and researchers at CQ cover Congress and its members on a weekly, daily, and even hourly basis, through the pages of CQ Weekly and CQ Today, and our online news service, CQ.com.

Under the direction of editors Jackie Koszczuk and H. Amy Stern, they have produced the most objective, authoritative and interesting volume of political analysis available on this fascinating collection of people.

In constructing these profiles, CQ writers draw upon prior reporting on the day-to-day actions in the House and the Senate, member interviews, campaign materials, and media appearances, among other sources.

3.3.2 Advantages of an “Inside the Beltway” Measure

Building a reputation measure based on the efforts of expert congressional journalists offers clear benefits on the grounds of realism, consistency, and objectivity. As discussed in greater detail in Chapter 2, very few Americans actually keep tabs on specific bills their member introduces or cosponsors, or particular votes their member takes. And the few legislative actions that do trickle down to constituents tend not come via diligent C-SPAN viewing or personal investigation, but rather from the media. By using a media-derived measure of reputation, I am able to approximate the representational relationship as it actually exists. The vast majority of information that people have about the representation they are receiving comes from media reports, so it is reasonable to operationalize reputation as it is filtered through a media lens.

Using a national media-derived measure is also beneficial when seeking to evaluate senators and members of the House from all states and all districts. Not all members of Congress have clear, single media markets in which they operate. Some members represent areas with an array of competing local stations and newspapers, while others may only have one, or sometimes none at all. Similarly, not all media outlets are created equal. While some outlets may have a correspondent in Washington, DC to monitor the behavior of their representative, many must rely on national coverage from the Associated Press and others, particularly as budgets for smaller newsrooms have declined over the past few decades. Given this, a national media source is useful as a broad-based measure, because it provides relatively consistent coverage across states and districts.

A national, “inside the beltway” media resource like Politics in America thus offers tremendous benefits when it comes to realism and consistency, but it also has clear advantages when it comes to objectivity and expertise. Politics in America is written by professional journalists, trained in the norms of objectivity and balance, who are on Capitol Hill day in and day out. These individuals specialize in understanding what is happening in the legislature, building relationships with members and their staff, and then synthesizing and communicating their findings in clear and objective ways. Reference Hero and TolbertHaynie (2002), for example, in his study of legislative effectiveness in the North Carolina state legislature, found that while lobbyists and other legislators offered evaluations of the effectiveness of Black lawmakers that were tainted by bias, the journalists did not.

3.3.3 Operationalizing Reputation

For each group of interest, reputation is measured on an ordinal scale that ranges across four levels: no advocacy, superficial advocacy, secondary advocacy, and primary advocacy. Primary advocates are either those members who are most known for their reputation as a disadvantaged-group advocate or those who are equally well-known for their work on behalf of one disadvantaged group as they are an additional issue or group, with neither clearly predominating.Footnote 5 Secondary advocates are those who do invest time and energy building a reputation as a disadvantaged-group advocate, but it is not clearly their top priority. Superficial advocates are those who are known to take at least some occasional actions on behalf of a particular disadvantaged group, while non-advocates do not include working to benefit a disadvantaged group as any part of their legislative reputation. These classifications are made on the basis of both the specific and implied legislative actions on behalf of the group that are enumerated in the profile as well as the representational statements that are used to characterize the member.

3.3.3.1 Legislative Actions and Reputational Statements

Legislative actions are any member-initiated steps that a member of Congress takes – within their purview as a legislator – to advocate on behalf of a particular disadvantaged group. To allow members that creativity and flexibility discussed in the sections above, this project was not started with a finite, a priori list of legislative actions. Instead, legislative actions are any behaviors detailed in a member profile that meet two conditions: actions must be specifically instigated by the member themselves and thus inside the realm of their control, and actions must pertain to their work in the legislature rather than being purely electoral. Next, I consider a key element to understanding what constitutes a legislative action – clearly distinguishing what it is not.

Roll call voting, for example, is not included as a legislative action because it does not require any initiative on the part of the member. Reaching a roll call vote requires collective action within the chamber and/or a decision by party leadership to bring the measure to the floor. As this project is focused on consciously constructed legislative reputation, only actions that are firmly within a member’s control and require a member-initiated choice to actively advocate on behalf of a group are included. Likewise, simple statements that a member “supports” or “opposes” a relevant issue are also not included (unless there is additional, more specific description) because it is unclear what action – if any – the member has actually taken.

Similarly, actions taken earlier in a member’s life, before they made it to Congress, are not included, nor are actions taken in the purely electoral arena, as these do not meet the legislative threshold required for a legislative action. Prior experience as an immigration attorney or running a veterans’ nonprofit is likely correlated with the decisions that a member will make when they go about forming their reputation, but it does not constitute a specific action taken within the legislature as a part of the conscious, intentional reputation formation process. Additionally, because this project is focused on the legislative reputations that a member builds within the institution of Congress, purely electoral actions, like running campaign advertisements or selecting a campaign debate strategy are not included. Again, these electoral choices are likely to be related to a member’s work within the legislature, but they are themselves distinct concepts. For example, a member may make promises while on the campaign trail about how they are going to serve particular communities, but then not actually take action to make good on that pledge.

Legislative actions can be specific and explicit, or they can be implied. For instance, a profile may specifically mention that a member offered an amendment to increase the minimum wage or sponsored a bill to protect women entering abortion clinics from being blocked by protesters, either of which would be examples of explicit legislative actions. These specific legislative actions can range from holding a hearing on a topic relevant to a disadvantaged group to cosponsoring a relevant measure to shepherding a bill through committee to staging a public demonstration (such as a talking filibuster or the 1991 march over to the Senate by women in the House during the Clarence Thomas hearings). Table 3.1 provides a thorough accounting of the variety of specific legislative actions attributed to members of Congress throughout all of the profiles evaluated.Footnote 6

Table 3.1 Legislative actions in the 103rd, 105th, 108th, 110th, and 113th Congresses

|

|

|

Legislative actions employed on behalf of disadvantaged groups by members of Congress.

Implied legislative actions are instances in which a member is described as being a “stalwart defender of veteran benefit programs,”Footnote 7 or a “longtime proponent of social programs that confront issues facing the poor,”Footnote 8 or having “promoted legislation to help his district’s substantial population of American Indians.”Footnote 9 Statements such as these clearly demonstrate that the member is recognized as having taken noticeable legislative actions on behalf of a group, even if those actions are not specifically laid out. Profiles can also contain broader reputational statements about members. These are more expansive than the implied legislative actions, and come in the form of a claim that a member advocates on behalf of a particular group, without tying it to any specific policy measure. Representational statements give a sense of the member’s legislative priorities, such as “Conyers has championed the causes of civil rights, minorities, and the poor,”Footnote 10 or “Green often works on behalf of people on the poorer end of the economic spectrum.”Footnote 11 These statements most commonly refer to a member as “serving,” “working on behalf of,” “prioritizing,” “advocating,” or “championing” the needs of a particular disadvantaged group.

3.3.3.2 Differentiating the Levels of Reputation for Group Advocacy

As described above, reputations for disadvantaged-group advocacy can take on one of four levels: primary advocates, secondary advocates, superficial advocates, and non-advocates. After reading each member profile, members were coded into the appropriate categories based upon three criteria.Footnote 12 The first of these criteria were the number of relevant legislative actions or reputational statements attributed to the member. The second consideration was the amount of space within the profile devoted to reputational statements or legislative actions advocating for disadvantaged groups. Third, members were placed according to the degree of attention paid to disadvantaged-group advocacy relative to other issues described in the profile. These coding decisions were made independently for each disadvantaged group under consideration. In the remainder of this section, I will discuss the application of these criteria for each of the potential levels of reputation for group advocacy in turn, beginning with the lowest level, non-advocates, and working up to the highest level, primary advocates.

A member rated on the lowest end of this ordinal scale, a non-advocate, is someone with a legislative reputation entirely unrelated to serving a given disadvantaged group. Either these members are never mentioned in conjunction with a disadvantaged group or the group’s legislative concerns or they are noted to be someone who has actively worked against a group or its interests. Non-advocates have zero reputational statements or legislative actions on behalf of a particular disadvantaged group attributed to them. This non-advocacy can take several different forms. For example, a member whose profile focuses primarily on their efforts to reduce climate change, with no mention of any disadvantaged groups or their relevant issues, would be coded as a non-advocate for all of the disadvantaged groups under consideration. Similarly, a member whose profile devotes considerable space to their work to address the needs of women, but references no advocacy behavior on behalf of other groups, would be coded as having a reputation for women’s advocacy, and as a non-advocate for each of the other groups. Likewise, a member who is noted as having fought against the reauthorization of the Voting Rights Act would be coded as having a reputation for non-advocacy when it comes to racial/ethnic minorities, but they could still be considered an advocate for veterans as a result of their efforts on behalf of that group.

The next step up, superficial advocacy, is the category for members whose reputations are largely based on other issues or groups, but whose profile does contain one sentence discussing a single instance of their work on behalf of a disadvantaged group. This sentence can include a reputational statement or a brief mention of a single legislative action taken on behalf of the disadvantaged group of interest. Most commonly, superficial advocates are noted to have taken one legislative action, like offering an amendment providing tax credits to businesses that hire unemployed veterans or cosponsoring a bill to repeal Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell. It is less common that profiles of superficial advocates contain a reputational statement, but it does occur. In these instances, a profile might state that a member is a defender of protections for senior citizens, but not include any further details beyond that single sentence about what the member has done to gain that reputation.

The next two categories, secondary and primary advocacy, represent the band of members for whom advocating on behalf of a disadvantaged group forms a considerable portion of their legislative reputation.Footnote 13 A member is coded as having a reputation as a secondary advocate if two conditions are met: first, if the profile includes two or more legislative actions and/or reputational statements pertaining to a disadvantaged group (totaling at least two sentences) or if the profile describes a single legislative action in great detail (occupying up to one paragraph); and, second, there are other groups or issues that receive a greater relative share of attention in the narrative. In the 113th Congress, Sen. Jack Reed of Rhode Island would be an example of a secondary advocate. Over the course of his long career, he has worked on a number of bills and provisions specifically intended to assist poor Americans, including measures to help low-income renters and provide assistance to people experiencing homelessness. His overall legislative reputation, however, is much more focused on foreign affairs and military conflicts in the Middle East.

Primary advocates are members who are profiled as having demonstrated strong reputational connections to a group by taking multiple legislative actions on that group’s behalf. It is not a requirement that these profiles must contain a specific reputational statement, but nearly all do – they tend to be explicitly mentioned as being an advocate with a strong focus on this group, usually within the first few paragraphs. The profiles of primary advocates devote at least one to two paragraphs worth of content to their efforts on behalf of the group, and there is no other issue with which they are more strongly associated (though, as highlighted earlier, another group or issue may receive equal billing, as would be the case for members focusing on the needs of women veterans). Rep. Frederica Wilson, of Florida’s 24th District, is a primary advocate for the poor. From the very top, her profile describes her as one who “prioritizes the needs of the underprivileged,” and cites her own words as further proof. She says “I’ve always advocated for children, for seniors, and for poor people. Not the middle class. Poor people. And I call it just like that. I don’t say that I’m trying to strengthen the middle class. I am trying to help people who are poor.” The profile goes on to describe her further actions in service to this goal, noting that Wilson has been a strong supporter of federal spending for unemployment and economic hardship, and advocated for the creation of a program to improve worker training efforts.

3.4 Reputation for Disadvantaged-Group Advocacy in Congress, 1993–2014

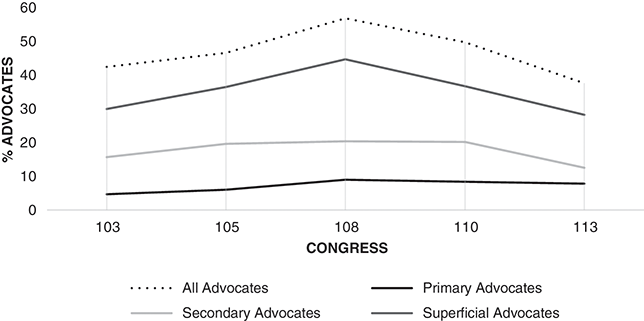

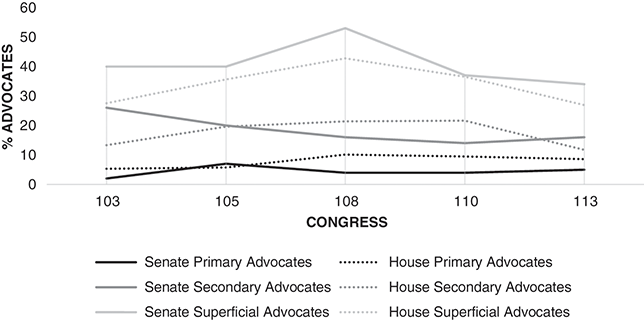

In each Congress evaluated between 1993 and 2014, a sizeable number of legislators formulated at least some portion of their reputation around representing disadvantaged groups. As seen in Figure 3.1, between 37 and 57 percent of members of Congress have a reputation as a primary, secondary, or superficial advocate for a disadvantaged group in any given term. The highest percentage of members with a reputation for disadvantaged-group advocacy was in the 108th Congress, with the lowest coming in the 113th Congress.

Figure 3.1 Disadvantaged-group advocacy in Congress.

Consistently, across all Congresses, there were higher percentages of superficial advocates than primary or secondary advocates, with the smallest percentage of members having a reputation for primary advocacy. The percentage of members with a reputation for superficial group advocacy largely follows the trajectory seen across all advocates, peaking in the 108th Congress and then declining over time. The rates of primary and secondary advocacy remained largely constant across the sample of Congresses studied. This demonstrates that while there is a small but consistent block of members who root a considerable portion of their reputation in serving disadvantaged groups, bigger changes over time are driven by those who exhibit superficial advocacy.

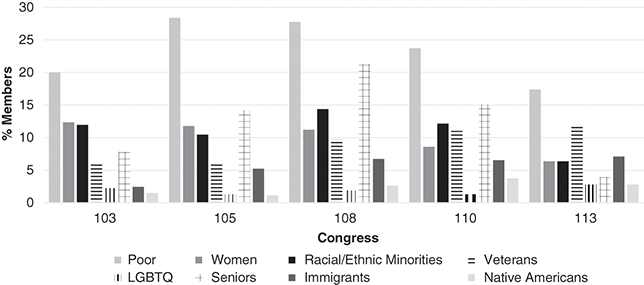

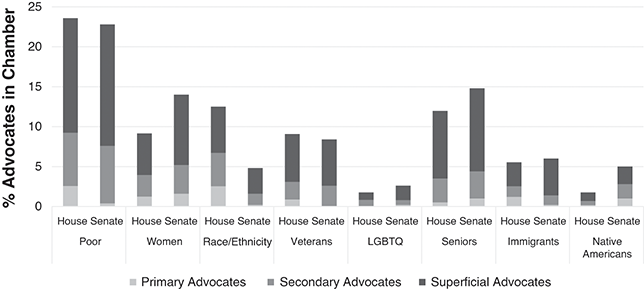

3.4.1 Variation in Reputations for Advocacy across Groups

There has also been variation over time in the percentage of members with a reputation for advocacy on behalf of any given disadvantaged group. Figure 3.2 shows the group-specific breakdown in advocacy in each of the sampled Congresses. In each Congress, more members incorporate advocacy on behalf of the poor into their legislative reputations than that of any other group, but there have been large swings in how many members have taken on this advocacy role. Given the centrality of economic concerns to the work within Congress, it makes sense that advocacy on behalf of the poor would be consistently at the top among other disadvantaged groups. Additionally, for much of the last century, there has been a broad consensus in Congress that the federal government should play at least some role in assisting those who are economically disadvantaged (even if the scope and means of that assistance has been fiercely debated).

Figure 3.2 Members of Congress with reputation as disadvantaged-group advocate.

Behind the poor, veterans and seniors tend to be the groups that members of Congress are the next most likely to cultivate a reputation around serving.Footnote 14 Veterans, seniors, and the poor are largely viewed sympathetically by the American public at large, so it is in line with theoretical predictions that higher percentages of members would choose to base at least some part of their legislative reputations around serving these groups. Native Americans and the LGBTQ community have tended to see the lowest percentages of group advocates within Congress.

Despite this consistency in which groups have the highest and the lowest percentages of members of Congress with reputations advocating on their behalf, there is considerable jostling among the middle ranks. This variability, in conjunction with the changes in magnitude across Congresses, demonstrates that there is considerably more to be understood about when members of Congress choose to cultivate a reputation around working on behalf of disadvantaged groups. It also highlights the importance of determining which groups are most likely to be the beneficiaries of these advocacy efforts, and what other factors can affect this over time.

It is also important to note that advocacy on behalf of these disadvantaged groups does not always exist in isolation. Rather, there are a number of members with reputations rooted in the advocacy of a number of different disadvantaged groups, sometimes with equal intensity and sometimes not. Twenty percent of sampled members who have fostered reputations for serving one disadvantaged group also have a reputation for advocating for another. Table 3.2 displays the correlations between member reputations as advocates on behalf of different groups.

Table 3.2 Correlations between reputations for advocacy of disadvantaged groups

| Poor | Women | Racial/Ethnic Minorities | Veterans | LGBTQ | Seniors | Immigrants | Native Americans | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poor | 1.00 | 0.12 | 0.22 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.18 | 0.06 | <0.00 |

| Women | 0.12 | 1.00 | 0.13 | <0.00 | 0.12 | 0.09 | 0.06 | <0.00 |

| Racial/Ethnic Minorities | 0.22 | 0.13 | 1.00 | −0.01 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.14 | <0.00 |

| Veterans | 0.05 | <0.00 | <0.00 | 1.00 | 0.01 | 0.03 | <0.01 | 0.06 |

| LGBTQ | 0.05 | 0.12 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 1.00 | 0.02 | 0.07 | −0.02 |

| Seniors | 0.18 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 1.00 | −0.02 | −0.01 |

| Immigrants | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.14 | <0.01 | 0.07 | −0.02 | 1.00 | <0.01 |

| Native Americans | <0.00 | <0.00 | <0.00 | 0.06 | −0.02 | −0.01 | <0.01 | 1.00 |

Pairwise Pearson correlation coefficients showing the relationship between holding reputations for advocacy across different disadvantaged groups. Statistically significant correlations (alpha=0.05) are in bold face. N=2,675.

This table shows the linkages between reputations for advocacy across groups. The strongest significant relationship exists between advocates for the poor and advocates for racial and ethnic minorities, implying that it is not uncommon for members with a reputation as an advocate for one to also have a reputation as an advocate for the other. This is in line with Reference Miller and StokesMiler’s (2018) findings that champions of the poor tend to be those who also focus on the intersections of poverty with gender and race. There are also notable ties between reputations for advocating for the poor and reputations for advocating for women and seniors. A reputation for advocating for women is also linked to reputations for LGBTQ advocacy. Additionally, there is a statistically significant relationship between reputations for advocating for racial and ethnic minorities and those for advocating on behalf of immigrants.

3.4.2 Party Affiliation and Reputation for Group Advocacy

Given the bonds between many of these disadvantaged groups and the general Democratic Party coalition, it is tempting to dismiss the formation of a reputation as a group advocate as a purely Democratic phenomenon. But in fact, these reputations are held by both Democratic and Republican members of Congress. While Democrats are considerably more likely to formulate such a reputation, with 59 percent of the Democrats sampled holding reputations at least partially based on advocating for disadvantaged groups, a non-negligible percentage of Republicans do as well. About a third of the Republicans sampled (33%) had primary, secondary, or superficial reputations for working on behalf of the disadvantaged. Figures 3.3 and 3.4 show the breakdown by group of the reputations for advocacy among Democrats and Republicans.

Figure 3.3 Disadvantaged-group advocacy among Democrats, 1993–2014.

Figure 3.4 Disadvantaged-group advocacy among Republicans, 1993–2014.

These figures are interesting for revealing both the variation between the parties as to which groups members seek to incorporate as a part of their legislative reputation, as well as the similarities. Again, Democrats in the sample are nearly twice as likely to have advocated for at least one disadvantaged group as a part of their reputation than Republicans. But among just those instances in which some portion of a member’s legislative reputation is devoted to advocating for the disadvantaged, there are a surprising number of similarities. Roughly the same percentage of Democratic and Republican advocates focus their efforts on behalf of women, the poor, and seniors, with Democrats slightly more likely to have reputations around advocating for the poor, and Republicans slightly more likely to advocate for seniors. There is also almost no difference in the percentage of Democrats and Republicans with reputations for advocating for Native Americans, immigrants, and the LGBTQ community.

Given the large differences between the Republican and Democratic coalitions and their corresponding policy agendas, this level of agreement is somewhat surprising. Among those who advocate for disadvantaged groups, there is a considerable amount of cross-party agreement in terms of which groups are incorporated into some portion of a member’s reputation. This demonstrates some of the advantages of using a method of operationalization that focuses on intent, rather than means. Democrats and Republicans may have very different approaches to how best to advocate on behalf of these disadvantaged groups, but the efforts of each are still recognized.

There are also some noteworthy points of departure between the two parties. The biggest difference in reputation formation comes in the advocacy on behalf of racial and ethnic minorities. While for Democrats serving as an advocate for racial and ethnic minorities is the second most common reputation to hold, among Republicans it is one of the least common. When it comes to Republicans, however, a considerably higher portion of Republicans who choose to build a reputation as a disadvantaged-group advocate incorporate advocacy on behalf of veterans into their legislative reputations than is true of Democrats.

Finally, there are additional differences in the levels of advocacy that Republicans and Democrats tend to engage in. Nearly 21 percent of Democrats with a reputation for disadvantaged-group advocacy are primary advocates, while this is true for only 6 percent of Republicans. Democrats are also more likely to be secondary advocates, with 45 percent of Democrats with reputations for advocacy meeting this criteria, compared to only 26 percent of Republicans. Republicans are slightly more likely than Democrats to have reputations for superficial advocacy alone, by a margin of 80 percent to 73 percent.

3.4.3 Reputations for Advocacy in the Senate and the House

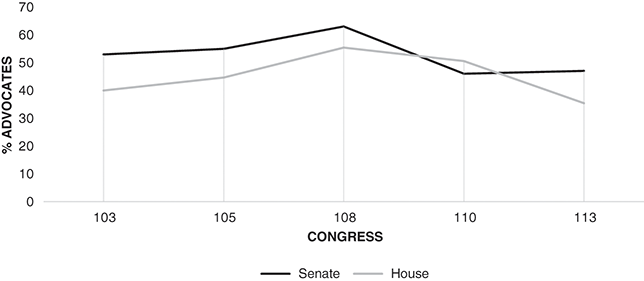

Distinctions in the number of members with reputations for group advocacy exist not only between members with different party affiliations, but also between members serving in the House of Representatives and the Senate. Figure 3.5 shows the percentage of members in each chamber with reputations for disadvantaged-group advocacy for each of the five Congresses in the sample. Generally speaking, there are a higher percentage of senators possessing these reputations in any given Congress than members of the House of Representatives. On average, 53 percent of senators form some portion of their legislative reputation around serving the disadvantaged, while the same is true for only 45 percent of members of the House. This general difference in the percentage of members in each chamber with reputations as disadvantaged-group advocates matches with the general understanding of senators as generalists, while House members tend to specialize. But how does this break down across levels of advocacy?

Figure 3.5 All disadvantaged-group advocates across chambers.

Figure 3.6 shows the percentage of members in the House and the Senate with a reputation as primary, secondary, and superficial advocates for disadvantaged groups. Here, too, the general divergences between the two chambers tend to comport with expectations around the percentage of their reputations that senators devote to a single group or issue relative to members of the House. A higher percentage of senators have a reputation of superficial advocacy than House members, with their profiles making note of only a single action or general representational statement on behalf the group. This matches with the picture of senators as more likely to weigh in on a broad array of issues, and less likely to devote high proportions of their representational energy to a single group. Reputations for secondary advocacy are roughly the same across the two chambers, while a higher percentage of House members hold reputations as primary advocates for disadvantaged groups.

Figure 3.6 Types of advocates across chambers.

To this point, differences between the House and the Senate largely align with what would be expected just given broad tendencies toward specialization or generalization respectively within those chambers. But this story changes somewhat when considering reputations for advocacy broken down by group, as seen in Figure 3.7. Across a number of these groups, the same general patterns hold, with the Senate tending to have more members with reputations for advocacy in total, but most of that boost coming from superficial and secondary advocates. Similarly, for most disadvantaged groups, higher percentages of members with primary reputations for advocacy are found in the House.

Figure 3.7 Reputations for advocacy in each chamber across groups.

It is the deviations, however, that stand out the most. The most glaring of these is the difference between the House and the Senate in the percentage of members with reputations for advocating on behalf of racial and ethnic minorities. There are considerably more members with a reputation for primary advocacy in the House, but the discrepancy goes well beyond this. Members of the House also outstrip senators in terms of reputations for secondary and superficial advocacy as well. In addition to this, there are also more members of the House with reputations for advocating on behalf of veterans, immigrants, and the poor, but the bulk of the differences are accounted for by higher numbers of primary advocates in the House. However, there are a few groups with a higher percentage of advocates in the Senate than in the House. Women, Native Americans, and seniors have had a larger percentage of senators with a reputation for working for them than House members.

3.4.4 Unpacking Reputation

This chapter opened by describing the three central characteristics of a legislative reputation: it is something more than just the sum of its parts, it is not reliant on any one particular type of action, and it must be perceived by an outside observer. The third characteristic of reputation is clearly achieved in the construction of this reputation variable, because it relies upon the perspectives of the journalists authoring the Politics in America member profiles. But what of the first two? To what extent does this construction of reputation exist as a stand-alone concept that can be separated from singular actions?

I evaluate how well my measure of reputation achieves these requisite criteria by considering the correlation between the measure of reputation introduced in this chapter and the most common legislative proxies used in past research, bill sponsorship and cosponsorship. If member reputation does not constitute an emergent property in and of itself, and instead is simply a reflection of a journalist’s dutiful accounting of the bills that a member introduces, there should be an extremely high and consistent correlation between these metrics and this new reputation variable. On the other hand, if reputation is a unique, separable concept wherein bill sponsorship or cosponsorship are just two examples of the many tools and tactics a member can use to build a reputation, correlations between a member’s reputation and the sponsorship and cosponsorship measures should not be consistently high, and instead exhibit a considerable level of variation.

Table 3.3 shows the correlations between a member’s reputation for advocacy of a particular group and the number of relevant bills on behalf of that group that the member sponsored or cosponsored in a given Congress.Footnote 15 The relationship between a member’s reputation and their bill sponsorship and cosponsorship activity varies widely when advocates for different groups are considered. This ranges from a fairly strong correlation between these particular legislative actions and those with reputations as advocates for Native Americans in both chambers to an entirely insignificant relationship between bill sponsorship and cosponsorship and building a reputation for the advocacy of racial/ethnic minorities in the Senate. For advocates of other disadvantaged groups, the extent to which their reputations are tied to their sponsorship and cosponsorship activity falls somewhere between these two poles.

Table 3.3 Correlation between reputations for advocacy of disadvantaged groups and sponsorship and cosponsorship activity in the US House and Senate

| Poor | Women | Racial/Ethnic Minorities | Veterans | Seniors | Immigrants | Native Americans | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| House of Representatives | |||||||

| Sponsorship | 0.25 | 0.38 | 0.30 | 0.26 | 0.12 | 0.21 | 0.38 |

| Cosponsorship | 0.43 | 0.31 | 0.39 | 0.15 | 0.12 | 0.26 | 0.47 |

| Senate | |||||||

| Sponsorship | 0.27 | 0.23 | −0.01 | 0.24 | 0.21 | 0.25 | 0.36 |

| Cosponsorship | 0.30 | 0.26 | −0.03 | 0.18 | 0.12 | 0.22 | 0.49 |

Pairwise Pearson correlation coefficients showing the relationship between holding a reputation for advocacy for a given disadvantaged group and the percentage of member sponsorship and cosponsorship activity devoted to that group (measured using the issue codes from the Policy Agenda Project.) Statistically significant correlations (α = 0.05) are in bold face.

These results clearly demonstrate that a member’s legislative reputation is not simply synonymous with their sponsorship and cosponsorship activity. Reputation is related to these actions, as would be expected, given that introducing and cosponsoring legislative proposals are important tools in a member’s arsenal when seeking to build a reputation as a disadvantaged-group advocate, but they are neither all-inclusive nor equally applied on behalf of different groups. Chapter 6 evaluates which members are likely to select bill sponsorship and cosponsorship as the key tactics for their reputation building efforts and develops new theories regarding the circumstances under which this is more or less likely to occur for particular groups. The preliminary analysis is presented here, however, to emphasize the validity of this original and innovative measure of reputation, and to further demonstrate its success in meeting the three criteria laid out above.

3.5 Wielding Influence as a Disadvantaged-Group Advocate

Representing the disadvantaged through building a reputation as someone who advocates on their behalf offers important symbolic benefits to these groups, but it also has real substantive effects. Frequently, these effects do not immediately take the shape of monumental legislation, but rather the steady, over-time work to create persistent incremental change, protect progress that has already been won, and continue to push the conversation and build coalitions to be ready to take advantage of moments when big change is possible. Each advocate works to provide for their group in different ways, and they may vary in their success (just as all legislators do). But they can have an important, substantive impact on Congress and the lawmaking process, even if that impact is not always measurable over the lifetime of a single Congress. In the sections that follow, I trace two short examples of how different members of Congress with reputations for advocacy have played an important role in creating substantive change for two different disadvantaged groups.

3.5.1 Rosa DeLauro and the Fight for Pay Equity for Women

In 2009, Congress passed the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act. This measure, the first signed into law by President Barack Obama, amended the Civil Rights Act of 1964 to say that pay discrimination occurs not just the first time that an individual is unfairly compensated, but rather reoccurs for every subsequent paycheck. This law was a response to the 2006 Supreme Court case, Ledbetter v. Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company. In this case, the Court ruled that under the existing law, salary discrimination cases could not take into account prior discriminatory behavior outside of the 180-day statute of limitations, even if past discrimination impacted current salary. The 110th Congress (elected in 2006) first attempted to pass a corrective bill, but the bill stalled out in the Senate.

The law that finally passed in 2009 came out of the Education and Labor Committee in the US House, and was sponsored by that committee’s chair, California Rep. George Miller. There was, however, another member’s fingerprints all over the bill – Connecticut Rep. Rosa DeLauro.Footnote 16 Over the course of her career, Rep. DeLauro had been known as a relentless advocate for women, with a tireless focus on pay equity. Since 1997, DeLauro has pushed for and proposed a pay equity bill in every Congress. In the original 2007 hearings to consider what became the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act, Rep. DeLauro was called as an expert to testify on the bill (despite not being a formal member of the committee), as well as an additional paycheck fairness measure that she had introduced. In her speech celebrating the passage of the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act, Speaker Nancy Pelosi spoke about the important contributions of Rep. DeLauro, saying, “I want to salute Congresswoman Rosa DeLauro for being a relentless advocate. Ten years ago, she introduced the Paycheck Fairness Act and has been working on it for a long time. Over the years, our ranks have grown with those who recognize the importance of this legislation.”Footnote 17

Even in the wake of the successful passage of this bill, Rep. DeLauro felt that there was more to be done, and has continued to push on the issue and to advocate for the needs of women. In the 111th Congress, her Paycheck Fairness Act (which put the onus on employers to prove that gender-based pay discrepancies were not a result of unlawful gender discrimination) was originally a part of the Lilly Ledbetter Act that passed the House, but it was stripped out of the Senate version. Despite this setback, she has continued to work in every subsequent Congress to get this further advancement passed into law. Her efforts have been recognized by Lilly Ledbetter herself, who stated in 2019 on the tenth anniversary of the passage of the eponymous law that “it was never intended for [the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act] to be passed as the only fix for the ongoing pay disparity between men and women. Women across the country still need the tools in the Paycheck Fairness Act to ensure they get equal pay for equal work. I applaud Congresswoman DeLauro for her leadership in this fight since 1997[.] … Now is the time to get this done.”Footnote 18