I. Overview 13

II. Analysis 18

1. Preliminary Observations 18

2. Defence Arguments Operating at the Level of the Primary Norm 19

2.1. General Scope of and Reliance on the Applicable Treaty 19

2.1.1. Introduction 19

2.1.2. Defence Arguments Concerning the Perimeter of the Treaty 20

Exclusion of Taxation Measures 21

Non-Precluded Measures Protecting Essential Security Interests 26

Illegality of the Investment 30

2.1.3. Defence Arguments Concerning the Entitlement to Rely on the Treaty 34

International Public Policy 35

Estoppel 37

Acquiescence 39

Extinctive Prescription 40

Abuse of Right 42

Corruption 46

Wilful Blindness 49

2.2. Specific Scope of the Primary Norm 51

Scope of the Prohibition of Performance Requirements (Article 1106(5) of the NAFTA) 52

Reservation of Specifically Identified Measures (Article 1108(1) of the NAFTA) 53

Public Procurement Carve-Outs (Article 1108(7)(a) of the NAFTA) 55

Annexes Carving Out Measures for Certain Purposes 57

2.3. Assessment of Breach of the Primary Norm 59

Exercise of Police Powers 59

Margin of Appreciation 69

Public Interest Counterclaims 72

3. Defence Arguments Operating at the Level of Secondary Norms 77

3.1. Specific Excuses 77

Exceptions 78

Emergency Clauses (War and Extended War Clauses) 78

3.2. Generally Available Excuses 81

Necessity 82

Countermeasures 87

Théorie de l’imprévision (Unforeseeability or Hardship) 89

Force Majeure 92

3.3. Quantum Reduction 94

Clean Hands Doctrine 95

Contributory Fault 96

Duty to Mitigate Damages 98

III. Concluding Observations 99

Appendix: List of Cases Covered in this Study 100

1. This volume of the ICSID Reports is organised around a category which has neither clear contours nor, in earnest, any technical existence, as such, in international law.Footnote 1 Whereas the term “defence”, or some subcategories of this genus, such as “affirmative defences” or even very specific types of defences such as “duress”, may be familiar to lawyers in the common law tradition, its use in international law can only be by analogy. The term encompasses, under a single convenient expression, a wide variety of legal concepts that can be mobilised not only by the respondent but also by the claimant in arbitration proceedings. This initial observation is subject to two qualifications. First, despite the absence of a technical category of “defences” or “affirmative defences” in international law, concepts such as “estoppel” or “force majeure”, which are defences in domestic law, also operate in international law. Such concepts are indeed recognised by international law but they do not carry all the implications that domestic legal orders may attach to them by virtue of their domestic characterisation as [Page 11] “defences” or “affirmative defences”.Footnote 2 The second is that defences from domestic law may be applicable in investment arbitration and commercial arbitration proceedings as such, typically when the case raises contractual matters and the domestic law applicable to the contract or otherwise applicable in the proceedings recognises specific defences. To mark these two qualifications, this study uses the expression “defence arguments”, which emphasises the analytical – as opposed to the technical – nature of the category.

2. The broad and diverse category of defence arguments can be approached from a range of perspectives. Some commentators have discussed one specific defence argument (e.g. the police powers doctrine,Footnote 3 pleas of illegality,Footnote 4 countermeasures,Footnote 5 force majeure Footnote 6 or necessityFootnote 7) or a subset of them (e.g. clauses reserving non-precluded measuresFootnote 8 or circumstances precluding wrongfulnessFootnote 9). Some others have focused on the interests protected, such as the fight against corruption,Footnote 10 the protection of human rightsFootnote 11 or the preservation of the environment.Footnote 12 Yet some others have [Page 12] organised their analysis by reference to the effects on the proceedings or the “stage” at which certain defence arguments intervene.Footnote 13 There is no single manner to organise such a discussion and, indeed, there cannot be one recognised manner given the wide variety of heterogeneous concepts brought together under the broad heading of “defence arguments”.

3. For this reason, the analytical organisation must follow the specific purpose of the context in which it unfolds. In the context of this volume, the purpose is threefold: (i) to provide an integrated study of the legal concepts discussed in the decisions selected for this volume of the ICSID Reports; (ii) to place such concepts and decisions in the wider context of the growing body of international decisions from investment arbitration tribunals and other adjudicatory bodies, and (iii) to analyse the operation of these concepts in a manner which is relevant both for the practice of international investment law and for the wider conceptual understanding of the field.

4. On this basis, the study consists of three main sections. The first focuses on the “wood” and provides an overview of the defence arguments covered by the investment and commercial arbitration decisions reported in this volume. The second discusses the “trees”, namely each one of the defence arguments covered in the reported cases as well as some related arguments. These are not the only defences that have been relied on in investment arbitration. Others include distress,Footnote 14 duress,Footnote 15 coercion,Footnote 16 the exceptio inadimplenti non est adimplendum Footnote 17 [Page 13] or the rebus sic stantibus clause.Footnote 18 But given the context and purpose of this study, such arguments are not analysed here. The material covered in this study includes many concepts examined in some of my previous work,Footnote 19 on which I rely in this study in an effort to provide a more general and integrative treatment of the subject. The third and final section offers brief concluding observations.

I. Overview

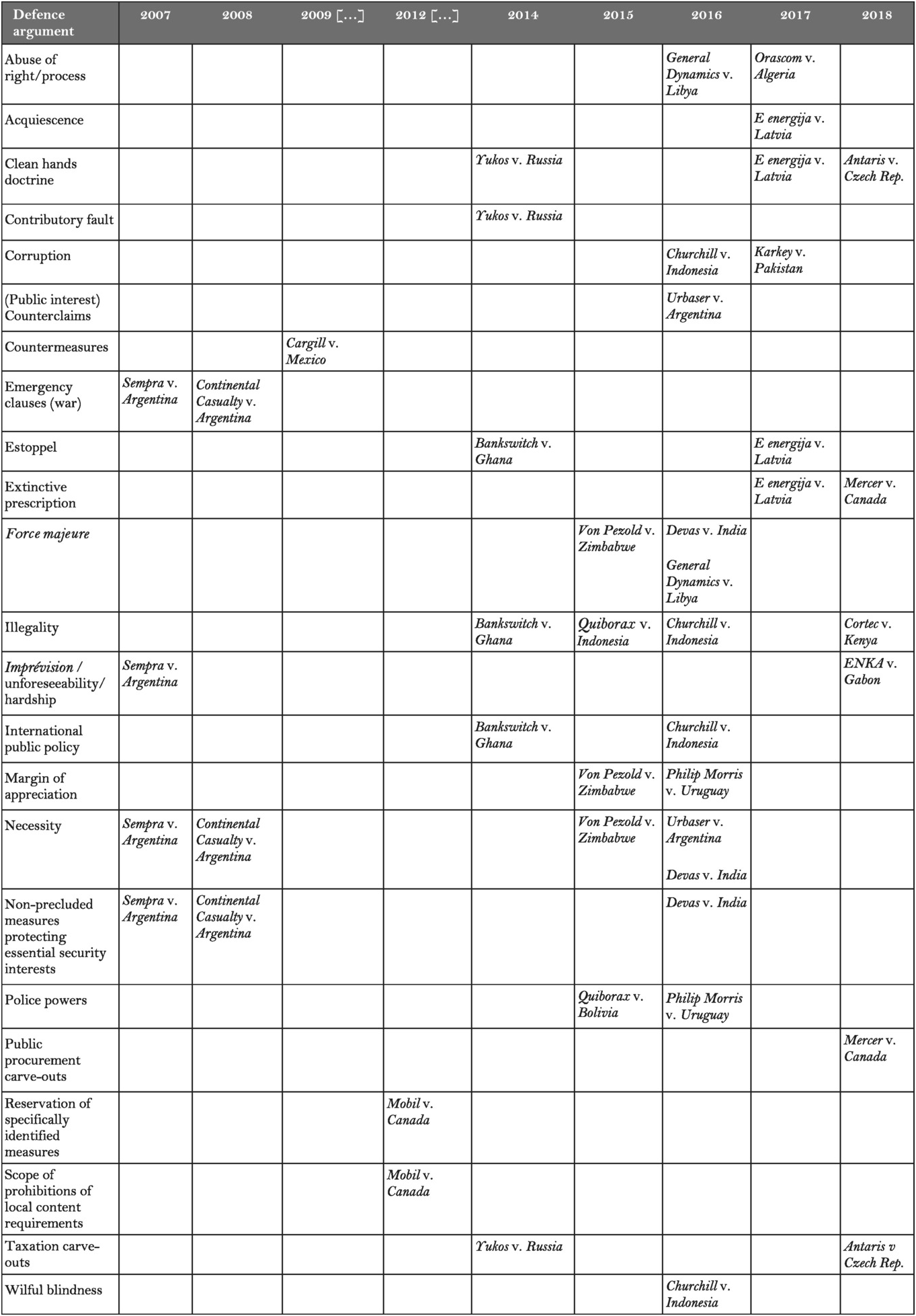

5. Following the content selected for the present volume, this study covers twenty-three defence arguments, which are discussed in detail in one or more of the reported decisions, as well as three other related defence arguments. Figure 1 summarises the material reported by connecting each one of the twenty-three defence arguments to the relevant reported decisions, organised by year of publication. Some important decisions have not been included in this volume because they were reported in previous volumes.Footnote 20 Examples include the award in Saluka v. Czech Republic (a major precedent for the police powers doctrine),Footnote 21 the decision on liability in LG&E v. Argentina Footnote 22 or that of the Ad Hoc Committee in CMS v. Argentina Footnote 23 (both important precedents for the operation of non-precluded measures and the customary necessity defence).[Page 14]

Figure 1 Defence arguments in reported cases

[Page 15] 6. While some of the decisions reported in this volume are more than a decade old,Footnote 24 the bulk of the volume focuses on more recent decisions, which often provide a summary of the previous body of case law relating to a given defence. For these decisions, the objective is not that of reporting a leading case but that of identifying a “juncture” between a relatively mature body of case law on a given defence and subsequent developments. Two illustrations are Cargill v. Mexico on the issue of countermeasuresFootnote 25 and Cortec v. Kenya on the operation of the plea of illegality.Footnote 26 Other reported decisions are, at least in part, foundational or important precedents. Such is the case, for example, of the discussion, in Yukos v. Russia, of the operation of the tax carve-out (Article 21) in the Energy Charter TreatyFootnote 27 and the doctrine of clean hands in international law,Footnote 28 that of the margin of appreciation doctrine in Philip Morris v. Uruguay,Footnote 29 that of public interest State counterclaims in Urbaser v. Argentina Footnote 30 or, still, that of abuse of right in a context of multiple arbitration claims in Orascom v. Algeria.Footnote 31 However, the selection of reported decisions is not an endorsement of their conclusions. Such conclusions are, in some cases, controversial and possibly unrepresentative of the state of international law, as discussed in Part II of this preliminary study.

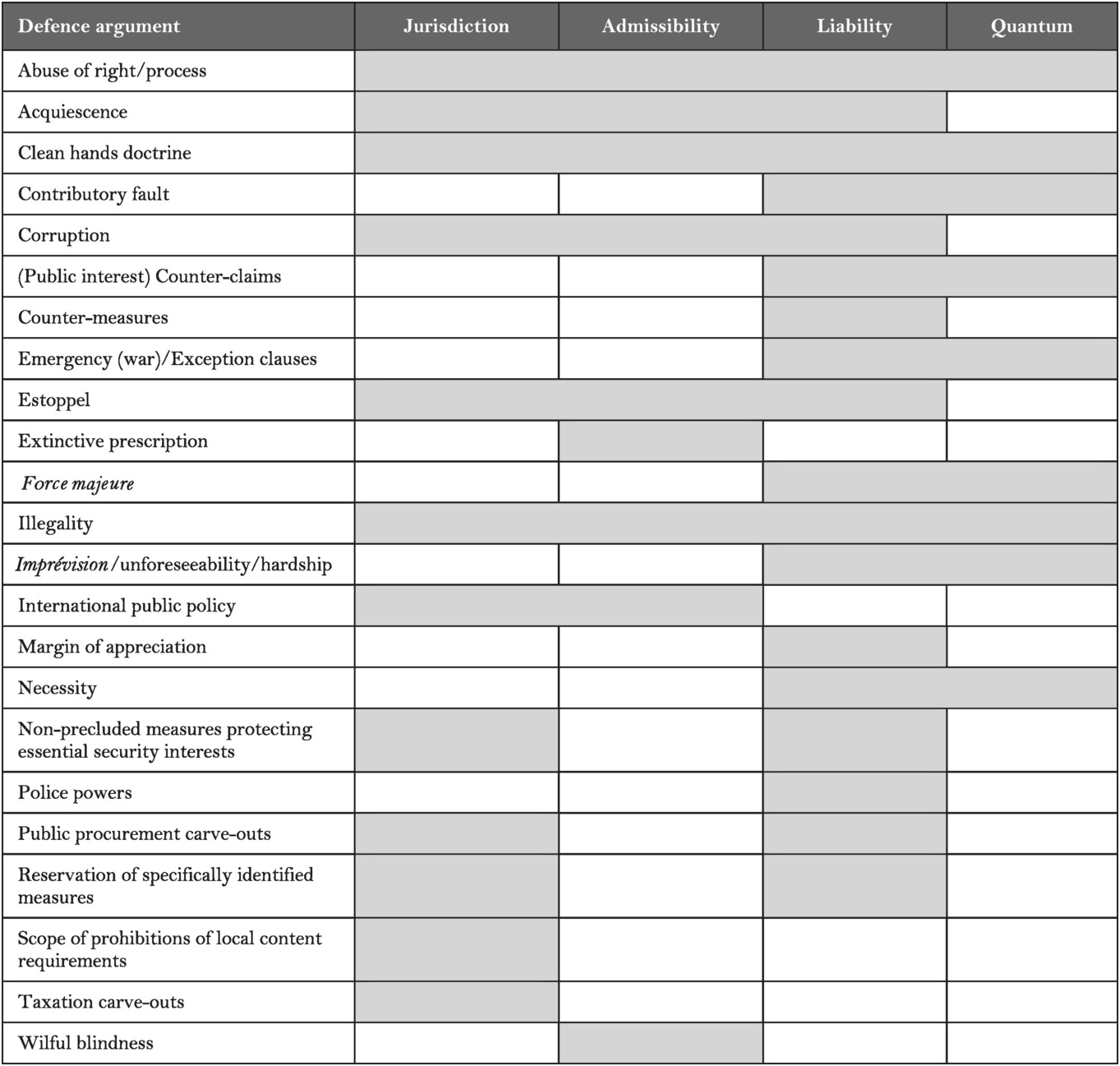

7. A second dimension relevant for the analysis of defence arguments is their stage of intervention. Some defence arguments, e.g. the illegality of an investment, have a broad span stretching from jurisdiction, over admissibility, to the merits and even quantum. The assessment of such span must be conducted in concreto, i.e. by reference to cases in which a defence argument has been actually used to challenge jurisdiction or admissibility or to defeat an argument on the merits or reduce or exclude damages. Even when such arguments are unsuccessful, recognition by a tribunal that they can operate at a given stage is deemed sufficient to establish their span. Yet, as before, recognition of their span in this manner is, for present purposes, a purely descriptive exercise, and it is not an endorsement of the legal positions followed in the reported decisions. Subject to this caveat, Figure 2 summarises the span of the twenty-three defence arguments covered in the reported decisions.[Page 16]

Figure 2 Stage of operation of the defence arguments covered

8. A third dimension relevant for this overview concerns the broad dividing line between what can be called “exemptions” (whether the specific term retained in a given treaty or case is that of “carve-out”, “safeguard”, “derogation” or “non-precluded measure”) and “exceptions” (whether “exception” or other terms, such as “emergency” or “war clauses” or “circumstances precluding wrongfulness” or, still, “excuses”). From a technical perspective, the key consideration is whether the defence argument operates at the level of the primary norm of conduct or at that of the secondary norms of State responsibility. This distinction, famously introduced by Roberto Ago to modernise the codification effort of the UN International Law Commission on the complex topic of State responsibility,Footnote 32 is sufficiently established to be relied upon as a legally meaningful dividing line. Exemptions [Page 17] generally operate at the level of the primary norm. If a given measure falls under the scope of an exemption (irrespective of the terminology retained), it is not covered by the primary norm and hence the latter cannot be breached. If, instead, a given measure falls under the scope of an exception (again, irrespective of the terminology retained), it both falls under the scope of the primary norm and this norm would be technically breached, with all the resulting consequences, but for the operation of the exception (whether the latter excuses the breach or removes its wrongfulness altogether). In CMS v. Argentina, a distinguished Ad Hoc Committee emphasised this difference, noting that an exemption (in casu Article XI of the Argentina–US BIT) could not operate at the same time as the customary necessity defence precisely because if Article XI applied, there could be no breach capable of being excused by the necessity defence.Footnote 33 A dividing line formulated in terms of “exemptions” and “exceptions” leaves out, however, a range of important defence arguments, such as the police powers and the margin of appreciation doctrines, which cannot easily find a meaningful place in this analytical cartography. Thus, to make the distinction better adapted to a wider range of defence arguments, it is useful to rely on the distinction between arguments that operate at the level of primary and secondary norms, respectively. Figure 3 summarises this vantage point for the full set of defence arguments covered in this study. The location of different defence arguments in Figure 3 reflects their operation in the decisions reported in this volume or discussed in this preliminary study.

Figure 3 Angle of incidence of the defence arguments covered

[Page 18] 9. The implications of formulating – as counsel – or appraising – as arbitrator – a defence argument from one or the other side of the dividing line are potentially significant, whether technically or practically. By way of illustration, much is conceded if the police powers doctrine, which is a corollary of State sovereignty, is argued as an “exception” rather than as the “rule”. The burden of proof, the stated or implicit level of restrictiveness of interpretation, the scope of scrutiny (or the degree of deference) or the sequence of application may indeed be significantly affected,Footnote 34 as I shall observe in the discussion of specific defence arguments in Part II.

10. Two additional caveats regarding Figure 3 concern its interactions with the vantage point adopted in Figure 2 and the observation, made in the introduction, that in international law the category of “defences” or “affirmative defences” has no technical existence. Regarding the first caveat, the tables are consistent, but they cannot be reduced to one another. For example, whereas the plea of illegality may operate at the stages of jurisdiction, admissibility, merits and quantum, Figure 3 describes it by reference to its operation in the relevant decision reported in this volume, Cortec v. Kenya. This decision illustrates the primary function of the illegality defence, which is to reserve the benefits of a treaty only for lawful investments. Subsequent practice has stretched the operation of this clause well beyond this initial function or, at least, elaborated on how such function is performed for different types of illegality. But, unlike Figure 2, Figure 3 is not intended to depict such developments. As regards the second caveat, the distinction between operation at the level of primary and secondary norms, respectively, does not reintroduce or acknowledge the existence of a technical category of “defences” or “affirmative defences” in international law. The implications of arguing or appraising a defence argument stem from the specific conditions attached to it in international law. Often, such implications, however important, will be of a practical nature. For example, a tribunal may reject the application of a specific standard of proof to establish corruption and, yet, in practice, refuse to be satisfied unless the corruption allegation is very clearly established. Similarly, a tribunal may refuse to recognise that a given clause must be interpreted restrictively and, yet, in practice, conduct a very restrictive interpretation. Practitioners are well aware of such differences, but conceptually it is difficult to chart them in a more general manner. Figure 3 attempts to do so, but it should not be read without keeping in mind this important caveat.

II. Analysis

1. Preliminary Observations

11. The categories identified in Figure 3 above serve to organise the discussion of the twenty-six defence arguments surveyed in this volume. This survey must be [Page 19] conducted in the light of both the reported decisions and the wider body of case law, mostly from investment tribunals but also, in some cases, from other international courts and tribunals.

12. In the following paragraphs, I focus on the “trees” but, in order not to lose sight of the “wood”, the discussion follows the broad headings of Figure 3, distinguishing between operation at the level of primary and secondary norms, and under each of these headings, between the different subheadings of Figure 3. The latter define a spectrum of defence arguments the operation of which is increasingly circumscribed, from a wider exclusion from the protection of the treaty, over the exclusion from the application of a given clause, to the assessment of breach of an otherwise applicable primary norm, to a specific excuse for an otherwise acknowledged breach, to generally available excuses for breach, to a reduction of the damage awarded.

13. As noted earlier, the location of each defence argument in this spectrum follows their operation in the decisions reported in this volume or discussed in this preliminary study. For each defence argument, particular attention is paid to issues such as (i) the operation of the relevant defence argument in the reported decision(s) as well as in the wider body of relevant case law, (ii) their principal “stage” of operation (jurisdiction, admissibility, merits, quantum) and/or (iii) their technical and/or practical implications (burden and standard of proof, interpretation, deference, and/or application sequence).

2. Defence Arguments Operating at the Level of the Primary Norm

2.1. General Scope of and Reliance on the Applicable Treaty

2.1.1. Introduction

14. The defence arguments organised under this subheading present some common features. One is that they all concern the general question whether a given treaty, specifically a bilateral investment treaty or the investment chapter of a free trade agreement, covers and can be relied upon to protect the investment of a foreign investor against action/inaction from the host State. What is at stake is the scope of and/or reliance on the entire treaty (or the investment chapter thereof) rather than on a specific investment discipline. Such scope/reliance may be excluded either because the action/inaction of the host State is excluded from the overall ambit of application of the treaty, i.e. they are outside the perimeter of the treaty, or because the circumstances are such that granting the protection of the treaty would be inappropriate.

15. Two significant implications can be derived from this basic feature. First, these defence arguments are capable of operating already in relation to the assessment of a tribunal’s “jurisdiction” or of the “admissibility” of a claim (or a set of claims). Some of them can also operate at a later stage of the proceedings. Secondly, from a technical and practical perspective, some of these arguments concern the perimeter of the applicable treaty (or instrument), with ensuing consequences for the allocation of the burden of proof and possibly for other aspects such as the approach to interpretation. Conversely, other defence arguments concern the possibility to rely on a treaty (or another legal basis) the perimeter of which normally covers the [Page 20] situation at hand. The latter focus has consequences for the allocation of the burden of proof and the setting of the standard of proof.

16. This principled position provides the background against which significant variations in the case law can be analysed. The volatility of the investment case law may at times blur this underlying principle and, in the absence of a clear explanation in the relevant cases, it is necessary to consider more coherent bodies of case law, such as that of the International Court of Justice (ICJ).

2.1.2. Defence Arguments Concerning the Perimeter of the Treaty

17. Two main defence arguments concerning the perimeter of the treaty are addressed in the reported decisions. The first relates to the operation of clauses that expressly exclude certain types of measures from the ambit of the treaty. The two main examples from the reported awards are the exclusion of “taxation measures” from the ambit of the Energy Charter Treaty (ECT)Footnote 35 pursuant to its Article 21 and the exclusion of certain measures protecting “essential security interests” under Articles XI of the Argentina–US BIT and 11(3) of the India–Mauritius BIT.Footnote 36

18. The proper role of broad exclusions must not be misunderstood. They are akin to other, more general, ways of defining the ambit of application of an instrument, typically by reference to four dimensions: subject-matter (ratione materiae), personal (ratione personae), temporal (ratione temporis) and spatial (ratione loci).Footnote 37 The norms defining – expressly or implicitly – the perimeter of a treaty thus state the rule, not an exception. One way to recognise them and distinguish them from “excuses” (which operate as exceptions, as discussed later) is their focus on “measures” rather than on “situations”. The object excluded from the perimeter of the treaty is a certain type of measure, however it is characterised (including by reference to situations), whereas clauses focusing on “situations” are intended to excuse certain conduct. An investor bringing a claim or a State bringing a counterclaim must establish that the measure it complains about is covered by the treaty. As a matter of principle, raising one of the many defence arguments that can be derived from the definition of the perimeter amounts to emphasising that the treaty is simply not applicable. Provisions such as Articles 21 ECT, XI of the Argentina–US BIT or 11(3) of the India–Mauritius BIT are part of this wider body of norms defining the perimeter of a treaty, and they concern specifically the scope ratione materiae of the relevant treaty. This observation also applies to the second type of defence arguments analysed here, namely, the illegality of the investment whose protection is sought. Yet, given that such illegality can take several forms, with different implications, it must be dealt with separately.

[Page 21] Exclusion of Taxation Measures

19. The operation of the exclusion of “taxation measures” under Article 21 ECT is addressed in detail in two decisions reported in this volume, Yukos v. Russia Footnote 38 and Antaris v. Czech Republic.Footnote 39 In Antaris, the tribunal observed at the outset that the focus of Article 21 ECT is on “measures” and that when the relevant measure is covered by the scope of the “carve-out”, the tribunal has no jurisdiction to hear a claim arising from such measures.Footnote 40 Subsequently, it set out a “two-step analysis” to “ascertain whether a putative tax measure qualifies under Article 21 of the ECT”, involving: (i) a characterisation of the measure, and (ii) an application of Article 21’s “inherent limits”.Footnote 41 The question of the burden and standard of proof arises for each prong of this test separately, and it will be addressed after analysing each of them.

20. On the first prong of the test, the Antaris tribunal focused on the characterisation of the measure as a “taxation measure” under domestic law. It began by noting that Article 21(7) ECT, which defines “Taxation Measures” for the purpose of Article 21, does not contain a “self-standing definition” of such measures but only a reference to either domestic law or applicable international instruments (e.g. double taxation treaties).Footnote 42 It then reviewed the evidence on the record and concluded that the solar levy imposed on renewable energy generators was not a “Taxation Measure” under domestic law. Aside from its fact-specific conclusions, the decision provides guidance for the assessment of the first prong of the test: substance (the nature of the measure) overrides pure form (the designation of the measure as a “tax”);Footnote 43 a tax is normally characterised by its focus, which is to raise revenue for governmental activities,Footnote 44 its non-equivalence, i.e. the fact that the amounts paid are not directly in exchange for a service or some other consideration,Footnote 45 and the general applicability of the measure, rather than the targeting of a specific company or group;Footnote 46 the importance of the characterisation of the measure by domestic courts and the context of such characterisation;Footnote 47 and some additional elements, such as the legislative history of the measure and the purposes stated by the government.Footnote 48

21. Further clarification of the meaning of “taxation measures” can be derived from cases relating to analogous tax carve-outs in other treaties. In EnCana v. Ecuador, the tribunal observed that a taxation measure (for purposes of Article XII(1) of the applicable treaty) is one “imposed by law”, and that such is the case if the measure is “sufficiently clearly connected to a taxation law or regulation”, [Page 22] irrespective of its legality under domestic law.Footnote 49 A taxation law was defined as “one which imposes a liability on classes of persons to pay money to the State for public purposes”.Footnote 50 The tribunal further noted that there is no reason to limit the concept to a certain type of tax or to the provisions of the tax law as such (rather than encompassing related regulations and decisions) and, importantly, that what is determinative is the “legal operation” of the measure, not its “economic effects … which may be unclear and debatable”.Footnote 51 Another relevant decision is Burlington v. Ecuador.Footnote 52 In this case, the tribunal relied on EnCana as well as on Duke v. Ecuador Footnote 53 to characterise a tax as involving four elements: “(i) there is a law (ii) that imposes a liability on classes of persons (iii) to pay money to the State (iv) for public purposes”.Footnote 54 These decisions all suggest that taxation measures can be characterised by reference to an objective core content.

22. The Antaris tribunal reached a similar conclusion – albeit following a different path – when characterising the second prong of the test. It noted that, although Article 21 ECT did not provide an “express international definition of tax measures to which the provision applies”,Footnote 55 the tribunal was “persuaded that Article 21 was not intended to encompass measures which had principal objectives other than the raising of revenue, but rather to exempt measures which formed part of a Contracting Party’s general tax regime, aimed principally at raising revenue”.Footnote 56 Thus, the tribunal introduced some objective meaning into the definition of taxation measures in Article 21, which constitutes an “inherent limit” to the ability of States to rely on the referral to domestic law made in Article 21(7)(a)(i) ECT. However, the second prong of the test also encompasses another type of limitation on the use of Article 21 ECT, which concerns not its scope but its invocation. The possibility of relying on Article 21 for measures adopted “under the guise” of taxation powers played a decisive role in a stream of decisions concerning the actions of Russia against Yukos and its shareholders.

23. The analysis of Article 21 ECT in Yukos v. Russia sheds light on the limits of both the perimeter and the invocation of this provision. Regarding the perimeter, the tribunal discussed the so-called “claw-back” of Article 21(5)(a) according to which “Article 13 [expropriation] shall apply to taxes.” This provision carves out claims for expropriation from the scope of the carve-out relating to taxation measures. Thus, Article 21(5)(a) is to Article 21 what Article 21 is to the ECT. The main issue in dispute was the wording used in Article 21(5)(a), which refers to “taxes” and not to “Taxation Measures” (as Article 21(1)). The tribunal rejected the interpretation proposed by the respondent, which considered taxes as a narrow subcategory of taxation measures, and sided with the claimant noting that “[i]n the [Page 23] view of the Tribunal, the ordinary meaning of ‘tax’ used in Article 21(5) cannot be narrower than the meaning of ‘Taxation Measure’ used in Article 21(1)”.Footnote 57 This interpretation is reasonable, and it seems consistent with Article 21(5)(b), which assumes that Article 13 remains fully operative in connection with taxes, but it does not explain why two different words were used in the same provision. Of note is the fact that the other claw-backs in Article 21 (i.e. paragraphs (2), (3) and (4)), all use the term “Taxation Measures”. The use of an undefined term such as “taxes” rather than a defined term, “Taxation Measures”, must therefore have an effet utile. The respondent’s understanding of “taxes” may have been too narrow, but it does capture that “taxes”, however narrowly or broadly understood, are a subcategory of taxation measures. As for the relations between Article 13 and Article 21, paragraph (5)(b) of the latter subjects claims against allegedly expropriatory and/or discriminatory taxes to a preliminary procedure (a referral to tax authorities) akin to the exhaustion of local remedies. The relations between this procedure and investment arbitration tribunals under Article 26 ECT are explicitly addressed in letters (i), (iii) and (iv) of Article 21(5)(b). The Yukos tribunal emphasised that, much like in other contexts where the exhaustion of local remedies is required, such procedures do not affect the admissibility of a claim when they are futile.Footnote 58 This conclusion makes clear that the referral is not a matter of perimeter (jurisdiction) but of invocation of Article 21 (admissibility).

24. The Yukos decision also sheds light on the operation of Article 21 ECT with respect to taxation measures adopted in bad faith. After recalling the factual conclusions that it had reached through a review of the entire record,Footnote 59 the tribunal reasoned that the “Article 21 carve-out does not apply to the Russian Federation’s measures because they are not … on the whole, a bona fide exercise of the Russian Federation’s tax powers.”Footnote 60 Instead, the tribunal saw the measures at stake as measures “under the guise of taxation, but in reality aim[ed] to achieve an entirely unrelated purpose”.Footnote 61 While this conclusion may fit the specific circumstances of the case, it conflates two distinct levels, namely that of good/bad faith in adopting the measures and that of good/bad faith in relying on Article 21. The analysis moves directly from one level to the other. The explanation provided to deprive Russia of the possibility of relying on Article 21 is reasonable, i.e. the risk that the mere “labelling” of a measure as “taxation” may place it outside the scope of the ECT. But such a risk could be addressed through other means: for example, a focus on substance rather than form, as in the approach followed by the Antaris tribunal, or an assessment based on a core characterisation of taxation measures, as in EnCana v. Ecuador. By contrast, limiting the scope of Article 21 only to bona fide taxation measures brings into the definition of taxation a subjective and fact-intensive dimension (measures may have more than one motivation and such motivation may be difficult to establish). The issue raised some controversy in an analogous context, namely the definition of investment. Some decisions brought good faith as part of the very definition of [Page 24] investment,Footnote 62 with the implication that only investments made in good faith would be protected. The alternative is that the definition of investment does not require an element of good faith, but bad faith or an abuse of right may, under certain circumstances (e.g. a restructuring after the dispute becomes foreseeable) preclude reliance on the treaty.Footnote 63 In the specific context of Article 21 ECT, the approach followed in the Yukos case may have the effect, at a minimum, of turning a technical legal question into a much more fact-intensive and volatile one, and possibly to extend the legal application of a treaty such as the ECT to measures which are excluded from it.Footnote 64 Thus, whereas the end result of the Yukos decision may be reasonable, the path selected is not without problems.

25. A further issue that must be addressed concerns the burden and the standard of proof. As a general matter, the tribunal has the competence to examine its own jurisdiction, if necessary ex officio, and the scope of Article 21 is not a factual matter but a legal one. The tribunal is therefore tasked with conducting this legal inquiry and reaching a conclusion. However, this apparently legal question can be deeply affected by factual considerations, such as the determination of whether the respondent abused its taxation powers to pursue motives unrelated to genuine taxation. These factual elements require an allocation of the burden of proving the relevant facts and the identification of the applicable standard of proof. Two main inquiries must be distinguished. First, on the allocation of the burden of proving the facts underlying the taxation carve-out, the two prongs of the test raise different issues. The decisions reviewed lack clarity on the allocation of the burden of establishing whether a measure is a taxation measure.Footnote 65 As a matter of principle, the burden of proving that the treaty is applicable to the measure challenged is on [Page 25] the party making such allegation, i.e. the claimant,Footnote 66 or exceptionally the respondent in the context of a counterclaim. The ambiguity comes from different possible readings of the maxim onus probandi incumbit actori. If the allegation to be proved is that the treaty is applicable, the onus would fall on the claimant. If the allegation to be proved is that the treaty is not applicable, the onus would fall on the respondent. When both allegations are made, as in virtually all cases, the solution will result from two main considerations. On the one hand, there is no presumption of/constructive applicability of a treaty, so any failure in establishing such applicability will eventually be borne by the party relying on the treaty.Footnote 67 On the other hand, for clauses excluding specific types of “measures”, the respondent can be expected to establish prima facie that the measure in question qualifies as an excluded measure, and then the burden will shift to the claimant to establish that such is not the case. This was the approach followed in Eiser v. Spain in connection with Article 21 ECT, where the tribunal noted that the respondent had established the “characteristics typically associated with a legitimate tax” and then shifted, implicitly, the burden to the claimant to establish that this preliminary showing should be disregarded.Footnote 68 The same logic applies to establishing the availability of a claw-back: the claimant would have to establish prima facie that the measure falls under this “exclusion from the exclusion” and then the burden will shift to the respondent.Footnote 69 By contrast, the burden of proving the “futility” of the tax referral procedure and, above all, bad faith in either the adoption of the measure or the reliance on the carve-out is clearly on the claimant.Footnote 70 With respect to the standard of proof applicable to “bad faith”, as in other similar allegations, it must be higher than the ordinary standard, however defined, although tribunals rarely specify it.Footnote 71

[Page 26] Non-precluded Measures Protecting Essential Security Interests

26. Regarding non-precluded measures adopted, inter alia, for the protection of “essential security interests”, the reported decisions address two main examples, namely Article XI of the Argentina–US BIT, which is discussed in Sempra v. Argentina Footnote 72 and Continental Casualty v. Argentina,Footnote 73 and Article 11(3) of the India–Mauritius BIT, discussed in Devas v. India.Footnote 74 These three cases illustrate the wide range of sometimes inconsistent views, which investment tribunals more generally have expressed regarding the operation of such clauses.

27. Sempra and Continental Casualty offer two contrasting views of the operation of Article XI of the Argentina–US BIT. In Sempra, the tribunal followed the steps of the tribunals in CMS v. Argentina Footnote 75 and Enron v. Argentina,Footnote 76 to treat Article XI as an emergency clause operating alongside – and subject to the same conditions as – the customary necessity defence.Footnote 77 As noted in Part I of this study, this conflation of two concepts which operate at separate stages was severely criticised by the Ad Hoc Committee in CMS v. Argentina, and the misapplication of Article XI led to the annulment of the Sempra and Enron awards on this specific point.Footnote 78 The award in Continental Casualty, which followed the decision of the Ad Hoc Committee in CMS, was also subject to an application for annulment. The claimant argued that the tribunal, in applying Article XI had disregarded an alternative claim, namely that even if Article XI applied to the measures in question, the respondent “must still compensate the Investor and cease its actions in breach of the Treaty because any threat to Argentina’s essential security interests or public order has passed”.Footnote 79 The Committee rejected the application for annulment in its entirety, but this allegation is a useful entry point to clarify the operation of clauses such as Article XI of the Argentina–US BIT.

28. The starting point of the analysis is that such clauses generally focus on “measures” and not on “situations”. A focus on the “situation” may render the above allegation of the investor before the Ad Hoc Committee in Continental Casualty relevant. As discussed later in this study, if a clause “excuses” certain conduct in the light of the situation, then the excuse can only last as long as the situation lasts. Yet, Article XI focuses on “measures”. It states that:

The Ad Hoc Committee in CMS had emphasised that Article XI was a “threshold requirement: if it applies, the substantive obligations under the Treaty do not apply”.Footnote 80 The tribunal in Continental Casualty followed this understanding when noting that: “[t]he consequence would be that, under Art. XI, such measures would lie outside the scope of the Treaty so that the party taking it would not be in breach of the relevant BIT provision”.Footnote 81[Page 27] This Treaty shall not preclude the application by either Party of measures necessary for the maintenance of public order, the fulfillment of its obligations with respect to the maintenance or restoration of international peace or security, or the Protection of its own essential security interests. (Emphasis added.)

29. This conclusion would normally entail, as discussed in the context of Article 21 ECT, that the tribunal has no jurisdiction over any claims resulting from the adoption of such non-precluded measures. The Continental Casualty tribunal gave, however, a different effect to such clauses, namely to exclude responsibility for breach of the investment disciplines invoked by the claimant. This is a counterintuitive conclusion, which may be explained by a combination of relative novelty (of the arguments relating to such clauses), inadvertence (in the way the respondent pleaded its case both at the jurisdictional level – omitting Article XI – and on the merits), and possibly a peculiar interpretation of the effects of the clause, which according to the tribunal “restricts or derogates from the substantial obligations undertaken by the parties to the BIT”Footnote 82 and revolves around the seriousness of the crisis addressed through the relevant measures.Footnote 83 Another tribunal, applying a different type of “non-precluded measures” clause (Article 10.10 of the Oman–US FTA),Footnote 84 reached an analogous conclusion, namely that such clause was to be relied upon at the merits stage for the interpretation of the fair and equitable treatment clause.Footnote 85 This is likely due to the specific formulation of the clause (“[n]othing in this Chapter shall be construed to prevent”) which emphasises matters of interpretation. Figure 2 above records these conclusions by signalling that clauses carving out non-precluded measures operate at the merits level according to some tribunals. Yet, as a matter of principle, the proper operation of non-precluded measures clauses should be at the jurisdictional level because the clause is a general exclusion from the perimeter of the entire treaty (“[t]his Treaty shall not preclude …”). What matters is whether the measures in question fall under the scope of the clause, in which case they are simply outside the treaty and any claim resulting from their adoption is beyond the jurisdiction of the tribunal.

30. An important question that has arisen in practice is whether the qualification of the measures is unilateral, i.e. “self-judging”. The question is analogous to that [Page 28] regarding the qualification of measures as “taxation” for the purpose of a tax carve-out. If the discretion of the State is unfettered, that may pave the way for abuse. In Continental Casualty, the tribunal relied on the case law of the ICJFootnote 86 to conclude that the determination by a State can be subsequently reviewed by a tribunal, although the State will “naturally” benefit from a “margin of appreciation”.Footnote 87 This conclusion is sound and reflects a settled position in the case law.Footnote 88

31. It is possible that out of the set of measures challenged, some may fall under the clause and some others may not. In Continental Casualty, the tribunal concluded that the restructuring of certain treasury bills did not fall under Article XI because its specific timing and terms did not make them necessary to protect essential security interests.Footnote 89 The conformity of such measure with the applicable treaty (specifically the fair and equitable treatment clause) was subsequently assessed and the measure found in breach of this standard.Footnote 90 It is also possible that the same measure may be in part sufficiently related to the protection of essential security interests and in part not. This situation arose in Devas v. India. The main issue was whether a measure (the reservation of a certain frequency of the electro-magnetic spectrum, the S-band, previously allocated to the claimants) was covered by Article 11(3) of the India–Mauritius BIT, according to which:

On the evidence, a majority of the tribunal concluded that, to the extent that the reservation of the spectrum served the needs of the defence and military forces, it fell under the clause. But the measure was also aimed to reserve the spectrum for “railways and other public utility services as well as for other societal needs” and, to this extent, it was not “directed to the protection of [the respondent’s] essential security interests”.Footnote 91 The part of the spectrum reserved for such other uses (which the majority of the tribunal estimated at 40 per cent) was not excluded from the perimeter of the treaty by the operation of Article 11(3), and it therefore fell under the relevant investment disciplines (in casu Article 6 on expropriation).Footnote 92 Importantly, for the 60 per cent part that fell under Article 11(3), the majority of the tribunal concluded that it lacked jurisdiction.Footnote 93The provisions of this Agreement shall not in any way limit the right of either Contracting Party to apply prohibitions or restrictions of any kind or take any other action which is directed to the protection of its essential security interests, or to the protection of public health or the prevention of diseases in pests or animals or plants.

[Page 29] 32. In addition to the applicable requirements and the effects, the proper framing of clauses on non-precluded measures is also relevant for the allocation of the burden of proof and the approach to interpretation. On the first issue, the observations made earlier in connection with taxation carve-outs apply generally. There is an important nuance, however, arising from the specific wording of each clause. Whereas establishing that a given measure is a “taxation measure” may be straightforward at a prima facie level, thus shifting the burden to the claimant, the same may not be true of measures which are defined by their relation to a situation of crisis (“public order”) or the pursuance of a specific goal (protection of “essential security interests”). If the respondent were to bear the full – rather than the prima facie – burden of proof, the operation of a general exclusion clause would, in practice, be equated with that of specific or general excuses. In other words, the claimant’s burden to establish that the treaty is applicable to its claims would not only be greatly facilitated, it would for most purposes be replaced with a presumption that the treaty applies. At the same time, a claimant cannot reasonably be expected to bear the full burden of proving that there was no crisis or that the measures are not sufficiently linked to the protection of essential security interests. To find an appropriate balance between these considerations, the respondent must establish prima facie that the clause is available, and a margin of appreciation must be granted to its determination of what measures are sufficiently linked to public order or to the protection of essential security interests. Once that prima facie showing is made, the burden shifts to the claimant. The decision in Devas v. India is significant in this regard because it made this point explicit:

The second issue to be noted is the approach to interpretation. Although tribunals routinely refer to the rules of treaty interpretation of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties,Footnote 95 the framing of a non-precluded measures clause may affect the level of stringency applied, technically or practically, in the assessment of the availability of a clause. In Continental Casualty, the tribunal observed that the margin of appreciation accorded to States in determining how to pursue these overriding goals is also relevant for interpretation purposes,Footnote 96 and it excluded the restrictive interpretation proposed by the claimant. Conversely, as will be discussed later in connection with the necessity defence (a generally available excuse), other tribunals have followed, in practice, a much more restrictive approach to interpretation based on a conflation of clauses reserving non-precluded measures and excuses.An arbitral tribunal may not sit in judgment on national security matters as on any other factual dispute arising between an investor and a State. National security issues relate to the existential core of a State. An investor who wishes to challenge a State decision in that respect faces a heavy burden of proof, such as bad faith, absence of authority or application to measures that do not relate to essential security interests.Footnote 94

[Page 30] Illegality of the Investment

33. Illegality of the investment as a defence argument can result from a specific provision in the applicable treaty (e.g. in the definition of “investment” or the delimitation of what investments are “protected”)Footnote 97 or from the implicit understanding that illegal investments do not deserve protection.Footnote 98 The operation of this argument is illustrated in three reported decisions, Bankswitch v. Ghana,Footnote 99 Churchill v. Indonesia,Footnote 100and Cortec v. Kenya,Footnote 101 though from different vantage points. To understand their contribution, it is useful to place them in the broader context of the case law addressing pleas of illegality.Footnote 102

34. As a general matter, pleas of illegality can operate at the jurisdictional, admissibility, liability and quantum stages, although the arguments vary across them. One significant distinction in the case law is that between “initial” and “subsequent” illegality.Footnote 103 Initial illegality concerns investments which were illegally “made”, and it may exclude jurisdictionFootnote 104 or make the claim inadmissible.Footnote 105 Subsequent illegality arises when the violation of domestic law results from the activities of the investment scheme after it was made. Such illegality is relevant for the assessment of the meritsFootnote 106 and possibly also for the reduction of [Page 31] quantum.Footnote 107 Given the implications of this distinction, it is important to determine what exactly may amount to “initial” illegality. This, in turn, raises three questions, namely: (i) the identification of the relevant domestic laws, (ii) the nature of the violation of domestic law, and (iii) the extent to which it can be relied upon for different purposes.

35. Over time, investment tribunals have tended to expand the scope of the laws relevant for the assessment of the illegality. A line can be drawn from some early cases such as Inceysa v. El Salvador, where the initial illegality is defined by some fundamental norms such as the prohibition of corruption,Footnote 108 over cases such as Saba Fakes v. Turkey, which define narrowly the domestic laws relevant for the determination of initial illegality,Footnote 109 to decisions such as Mamidoil v. Albania Footnote 110 or Cortec v. Kenya,Footnote 111 where the relevant laws are broadly understood. Mamidoil and Cortec are also significant for the understanding of other aspects of pleas of illegality.

36. The dispute in Mamidoil concerned allegations of mistreatment of a Greek investor in connection with the construction and operation of an oil container terminal as well as petrol stations in Albania. The respondent argued, among others, that the investment had not been made in accordance with the host States’ domestic laws because the claimant had failed to conduct a due diligence assessment or seek the relevant (construction, environmental and exploitation) permits. The tribunal found that the lack of construction and exploitation permits amounted to a non-trivial illegality, but it nevertheless asserted jurisdiction on the – debatable – grounds that the respondent’s behaviour had cured the initial illegality. Its reasoning can be summarised in four points. First, the tribunal adhered to the well-established distinction between initial and subsequent illegality.Footnote 112 Secondly, and importantly, it noted that illegality can arise out of inconsistency with substantive and/or procedural domestic law, and it understood both bodies of law broadly.Footnote 113 Thirdly, not any violation of domestic law was deemed capable of [Page 32] excluding jurisdiction. Only material breaches of domestic law, not minor irregularities have this effect. Fourthly, the tribunal admitted the possibility that initial illegality may not defeat jurisdiction when the respondent has forgone the possibility to invoke it (e.g. because the deficiency was cured domestically or on the basis of estoppel) or when the State has stood ready to remedy the illegality.Footnote 114

37. In Cortec v. Kenya, the dispute concerned the protection of “a mining license [SML 351] not issued ‘in accord with the laws of Kenya’ because the Claimants failed to satisfy statutory prerequisites such as EIA [environmental impact assessment] approval”.Footnote 115 The tribunal concluded, in essence, that “for an investment such as a license, which is the creature of the laws of the Host State, to qualify for protection, it must be made in accordance with the laws of the Host State”.Footnote 116 The particular type of “investment”, which unlike land, buildings or equipment, had no existence except under and in conformity with domestic law led the tribunal to conclude that there was, indeed, no investment capable of protection, hence that it had no jurisdiction.Footnote 117 But its reasoning with regard to the determination of illegality is relevant for any investment, particularly for the identification of the relevant domestic laws and of the nature of the inconsistency with them. On the first point, the tribunal took into consideration the entire Kenyan legal system to determine the lawfulness of the investment, but particularly three separate but similarly relevant statutes – the Mining Act, the Forests Act, and the Antiquities and Monuments Act – as well as the Environmental (Impact Assessment and Audit) Regulations. It concluded that, as a result of their combined application, the issuance of a mining licence to conduct operations in a protected area (the Mrima Hill nature reserve) was void ab initio. This is an important statement which emphasises that the relevant laws are not a narrow category (e.g. the domestic investment law) but the entire domestic legal system. At the same time, not every inconsistency with this system is capable of making an investment illegal. On this second point, the Cortec tribunal relied on a proportionality criterion borrowed from Kim v. Uzbekistan.Footnote 118 In Kim, the tribunal had retained the following test for a plea of illegality:

The Cortec tribunal reformulated this test as stating that “for an investment to be protected on the international level, it has to be in substantial compliance with the significant legal requirement of the host state”.Footnote 120 It noted, like the tribunal in Mamidoil, that omission of a minor regulatory requirement or inadvertent misstatements cannot have the same effect as “defiance of an important statutory prohibition imposed in the public interest”.Footnote 121 Relying again on Kim, the tribunal followed three steps in its determination of the nature of the violation, focusing tour à tour on: (i) the significance of the obligation violated, (ii) the seriousness of the investor’s conduct, and (iii) whether denial of protection under the BIT is proportionate with the violation, given the extent to which the host State’s interests are compromised.Footnote 122the Tribunal holds that the legality requirement in the BIT denies the protections of the BIT to claims when the investment involved was made in noncompliance with a law of [the [Page 33] host State] where together the act of noncompliance and the content of the legal obligation results in a compromise of a correspondingly significant interest of [the host State].Footnote 119

38. Significantly, it is not a requirement for the violation to be sanctioned with nullity in the domestic legal system, as long as proportionality is maintained. Illegalities that make a legal act voidable (annullable) rather than void (null) could be considered non-trivial, as suggested by the Mamidoil decision. Moreover, even when the degree of inconsistency is deemed not to require a denial of protection (at the jurisdictional or admissibility stages), the illegal conduct of the claimant can still be taken into account at the liability and quantum stages, much like subsequent illegality. Furthermore, it is possible that a subsequent illegality may be relied upon to challenge the admissibility of the claim.Footnote 123 In addition, it is also possible that an initial non-trivial illegality may be subsequently cured, as was the case in Mamidoil, or that the host State may be estopped from relying on such illegality. The latter case can be illustrated by Bankswitch v. Ghana. The dispute concerned the performance of a contract for the provision of an internet portal for Ghana’s customs operations. The arbitration proceedings were brought under the dispute settlement clause of the contract, which was subject to Ghana’s law. As part of its defence, the government argued that the contract was invalid because it had not received the parliamentary approval required by Article 181(5) of Ghana’s Constitution. The tribunal decided that Article 181(5) was indeed applicable, and that the validity of the contract was therefore subject to such approval; yet, it also found that the government, by reason of its conduct, was estopped from now claiming that such approval procedure had not been completed. Subsequently, it reviewed the claim on the merits and found that the respondent had breached the contract. This case will be discussed again in connection with estoppel but, for present purposes, together with Mamidoil v. Albania, it illustrates that even an initial illegality of sufficient importance may be inoperative. This limitation is itself subject to an overriding limitation, namely that illegality reaching a certain threshold of seriousness, such as corruption, wilful blindness and inconsistency [Page 34] with international public policy, cannot be cured or dismissed. This is discussed in the context of each one of these three specific defence arguments.

39. The allocation of the burden of proof for pleas of illegality is, as for other defence arguments, seldom fleshed out in the decisions of investment tribunals. Setting a clear line in this matter is difficult because pleas of illegality can operate at several stages of the proceedings and, depending on the specific context, the allocation may not be the same. Framed through the lenses of jurisdiction, as discussed earlier in this study, it is the tribunal which has to satisfy itself that it has the requisite jurisdiction over the claims submitted to it, but there may be factual questions associated with such a determination (e.g. the significance of the obligation violated, the seriousness of the investors’ conduct, and the impact on the host State’s interest) that require evidence and hence raise the allocation question. In Kim v. Uzbekistan, the tribunal expressly allocated this burden to the respondent:

In Cortec, the claimant requested the tribunal to allocate the burden to the respondentFootnote 125 and, although the tribunal did not take an explicit stance on this question, it endorsed the approach of the tribunal in Kim,Footnote 126 which implicitly endorsed such allocation. This seems justified because, unlike other defence arguments focusing on jurisdiction, illegality claims are based on an allegation of wrongdoing by the investor, which is for the respondent to establish. This is a fortiori the case when illegality is framed from the perspective of admissibility, as the allegation concerns wrongdoing of a magnitude that would require a tribunal not to exercise an adjudicative power that it possesses.Footnote 127Before the Tribunal begins its application of the legality test to the violations alleged in this objection, the Tribunal observes that Respondent has the burden of proof to establish that the investment was not made in compliance with a law of Uzbekistan.Footnote 124

2.1.3. Defence Arguments Concerning the Entitlement to Rely on the Treaty

40. Deprivation of reliance involves some form of inappropriate behaviour from the party bringing the claim or making the argument. Bad faith is not always required,Footnote 128 but there must be some degree of negligence or disingenuous behaviour, which in most cases must be established by the party relying on these defence arguments. Two broad sets of arguments can be identified within this subheading. The first set includes estoppel, acquiescence and extinctive prescription, as they have been argued in the investment arbitration context. When the conditions for these defence arguments are met, the party bringing the claim is prevented from relying on the applicable treaty or on another legal basis (e.g. a constitutional provision). The rationale underpinning these arguments is the lack of due diligence displayed by that party or the display of contradictory behaviour. By contrast, the second set of arguments are based on the existence of intent or wilful behaviour, [Page 35] whether when making the investment, corruption or wilful blindness, or when bringing the claim or exercising a right, abuse of right.

41. Defence arguments based on inconsistency of a claim (or of the underlying transaction) with international public policy (ordre public international) can be placed somewhere between these two sets of arguments. International public policy protects a set of core values presumptively recognised as overriding in all domestic legal orders. This makes the concept a composite one in that tribunals have included as part of international public policy concepts such as estoppel alongside other concepts such as corruption, fraud and wilful blindness. Moreover, depending on the framing of this defence argument, it may affect jurisdiction (there is no transaction) or admissibility (the transaction exists but the claim is inadmissible). Thus, it could also be seen as a form of aggravated illegality. In the next paragraphs, international public policy is first discussed in general, as a broad introductory defence argument which can deprive a claimant from relying on the applicable agreement. Subsequently, I focus on the defence arguments that do not require bad faith and, finally, on those that do require it. This discussion includes concepts linked to international public policy.

International Public PolicyFootnote 129

42. Among the reported decisions, Bankswitch v. Ghana Footnote 130 and Churchill v. Indonesia Footnote 131 touch upon the operation of international public policy (ordre public international), although only on specific issues which will be discussed later. As noted earlier, international public policy generally refers to a narrow core of principles of fundamental importance to a wide number of legal orders – hence presumed to be fundamental to every legal order – which override any inconsistent instrument, agreement or claim.Footnote 132 It is a complex concept because of (i) its origins, i.e. it arises from a constructive generalisation of the core values of domestic legal orders (which at a different epoch were called “civilised” or “advanced”); (ii) its composite content, which includes several other principles which may operate on a stand-alone basis (e.g. corruption,Footnote 133 fraud,Footnote 134 wilful blindness,Footnote 135 and estoppelFootnote 136); (iii) its overriding effects, which may void a [Page 36] transaction of its legal existence (defeating jurisdiction) or make a claim unenforceable (defeating admissibility); and (iv) its logic, which due to the composite content of the concept, varies according with the principle (it may involve deliberate wrongdoing or inconsistency with a higher value, which cannot be overridden transactionally, e.g. protection of human rights).

43. An important precedent clarifying the operation of this concept is World Duty Free v. Kenya,Footnote 137 where the investor sought to enforce a contract obtained by means of a bribe paid to the then Kenyan president. The agreement referred, in its arbitration and choice-of-law clauses, to English and Kenyan law. The tribunal dismissed the claim under both international law (relying on the concept of ordre public international or international public policy) and domestic English and Kenyan law. It noted that bribery was a criminal offence under the applicable Kenyan laws and that contracts obtained by bribery were deemed unenforceable in the common law authorities relevant to the case. Interestingly, the investor sought to mitigate the consequences of its illegal act by highlighting the illegal conduct of the Kenyan president, and it asked the tribunal to achieve a balance between both. However, the tribunal firmly dismissed this argument noting that, even if there had been a rule allowing such exercise of equitable judgement, its use would have been of no help to the claimant. The apparent unfairness of letting Kenya benefit from the illegal act of its president missed the point that the public policy concepts applicable in this case were intended to protect the public as well as to deprive any claimant (including Kenya, had it been the claimant in the case) from relying on a court of law to enforce an act executed against basic public policy principles.Footnote 138

44. A corollary of this conclusion is the impossibility of curing a violation of international public policy, as in Mamidoil v. Albania, or of foregoing reliance on it by reason of estoppel, as in Bankswitch v. Ghana. The latter presents additional complexity because the principle of estoppel has been recognised as part of international public policy.Footnote 139 It may thus be theoretically possible, admittedly in very rare circumstances, for a party to be estopped from invoking estoppel (under the international public policy defence). In the more extreme case of corruption or other grave infringements of the principles protected by international public policy, the reasoning to deny any possibility of curing the wrongdoing would therefore stem from either the inexistence of the transaction, as in Cortec v. Kenya, or the need to ensure “the rule of law, which entails that a court or tribunal cannot grant assistance to a party that has engaged in a corrupt act”.Footnote 140 The second justification has implications that the first does not. Indeed, it does not matter whether the inconsistency with international public policy is “initial” or [Page 37] “subsequent”, as in the context of illegality. It is the very nature of the inconsistency, whenever it occurs, which commands the denial of any protection.

45. The burden of proving an allegation of misconduct serious enough to be inconsistent with international public policy is with the party alleging such misconduct, normally the respondent.Footnote 141 The seriousness of the allegation is also relevant for the standard of proof. Sufficiently persuasive evidence is necessary, although tribunals have formulated this need through two different approaches. Some tribunals have considered that the “standard of proof” was a more demanding one, such as “clear and convincing evidence”.Footnote 142 The issue of the applicable standard of proof is not as clearly regulated in international law as it is in domestic law. The characterisation of the standard is therefore less decisive than the actual, including practical, requirements that a tribunal may expect for a serious allegation to be established. Thus, some other tribunals have focused not on the standard to be applied but on the persuasiveness of the evidence, which they have addressed through the lens of the ordinary standard (balance of probabilities or intime conviction).Footnote 143 The difference between these two approaches is one of form, not of substance. The demands placed on the party who has the burden of proof are similar.Footnote 144

Estoppel

46. Estoppel is addressed in two different contexts in the reported decisions, E energija v. Latvia and Bankswitch v. Ghana. In E energija v. Latvia, the respondent argued that there was no “dispute” under Article 25(1) of the ICSID Convention because the claimant had allegedly induced the respondent to rely on the matter being pursued through negotiations (estoppel) or that, by participating in a meeting allegedly premised on the idea that the investment dispute was “closed”, it had acquiesced to this conclusion or, still, that, by submitting its request for arbitration almost four years after its notice of intent, it had forgone its right of action as a result of extinctive prescription. The tribunal rejected the three arguments because the respondent, who was allocated the burden of proof,Footnote 145 had failed to establish the facts underlying the conditions for the application of these three defence arguments. The tribunal admitted that estoppel, acquiescence and extinctive prescription may deprive a tribunal of its “jurisdiction” due to an absence of “dispute”, a requirement of Article 25(1) of the ICSID Convention.

[Page 38] 47. Despite its brief and somewhat embryonic reasoning, the decision in E energija v. Latvia is a useful reminder of the operation of these defence arguments in an investment context. On estoppel, it recalls, relying on Pope & Talbot v. Canada,Footnote 146 the three requirements for establishing this defence argument:

These requirements are consistent with those identified by the tribunal in Bankswitch v. Ghana,Footnote 148 although in the context of a different allegation, namely that Ghana was estopped from claiming the invalidity of an agreement concluded with the claimant and which Ghana had treated as valid for some time.Footnote 149 The authorities on which the “elements” of estoppel (which in Bankswitch are deemed to be four) are identified also overlap significantly with those in E energija v. Latvia.Footnote 150 This characterisation is also broadly equivalent to that provided by the ICJ in the Land, Island and Maritime Frontier Dispute (El Salvador/Honduras) Footnote 151 and confirmed in Obligation to Negotiate Access to the Pacific Ocean (Bolivia v. Chile).Footnote 152(i) “a statement of fact which is clear and unambiguous”; (ii) a statement that “must be voluntary, unconditional and authorised”; and (iii) that “there must be reliance in good faith upon the statement either to the detriment of the party so relying on the statement or to the advantage of the party making the statement”.Footnote 147

48. The ICJ’s characterisation does not refer explicitly to the second requirement above (voluntary, unconditional and authorised statement). As the ICJ’s views on the state of general international law command authority, either the second condition is not an established requirement under general international law or it is implicit in the ICJ’s characterisation. The latter is suggested by an observation made by the Court in Obligation to Negotiate, by reference to a previous case,Footnote 153 according to which the statement (condition (i)) must be “consistently made” and the message conveyed must be “fully clear”.Footnote 154 A similar conclusion can be reached by reference to the earlier ICJ judgment in the North [Page 39] Sea Continental Shelf case (referring to “past conduct, declarations, etc., which … clearly and consistently evinced acceptance”Footnote 155 of the position protected by estoppel) and the more recent Chagos Island Arbitration, where the arbitral tribunal identified, as a requirement for estoppel, that the relevant representation must be “made through an agent authorized to speak for the State with respect to the matter in question”.Footnote 156

49. The Obligation to Negotiate case confirms that the burden is on the party alleging the estoppel argument to establish the facts underlying its conditions. It illustrates the operation of estoppel on the merits of the case (in casu, whether estoppel provided a basis for Chile to be bound by an obligation to negotiate with Bolivia an access to the Pacific Ocean), and it addresses the operation of acquiescence.

Acquiescence

50. For present purposes, the Obligation to Negotiate case discussed earlier is also a useful reference on acquiescence, given the very concise treatment of this argument in E energija v. Latvia. There, the tribunal found that, despite almost four years between the notice of intent and the request for arbitration, the conduct of the claimant did not amount to acquiescence to the extinction of its claims.Footnote 157 It did not provide a clear characterisation of the requirements of acquiescence, and none can be derived from the decision on which the respondent had based its argument.Footnote 158 By contrast, in Obligation to Negotiate, the ICJ recalled the meaning of acquiescence in general international law as a “tacit recognition manifested by unilateral conduct which the other party may interpret as consent”,Footnote 159 based on the idea that “silence may also speak, but only if the conduct of the other State calls for a response”.Footnote 160

51. As noted in connection with estoppel, the burden of proving that silence must be interpreted as consent is on the party alleging acquiescence.Footnote 161 In Obligation to Negotiate, acquiescence was relied on as a possible basis for the existence of an obligation to negotiate, which the Court rejected. This is a reminder that acquiescence can operate beyond matters of jurisdiction or admissibility, and it has actually played a significant role in territorial disputes.Footnote 162

Extinctive Prescription

52. Extinctive prescription is not clearly disentangled, in the reasoning of the tribunal in E energija v. Latvia, from acquiescence, perhaps due to the facts of the case. The tribunal concluded that, in the absence of a specific provision in the applicable treaty barring claims brought beyond a certain period of time, the claimant was free to choose the moment of filing of its arbitration request. The tribunal added that the period of almost four years between the notice of intent and the request of arbitration was “insufficient to attract the application of the doctrine of prescriptive extinction”,Footnote 163 without explaining this doctrine further.

53. The operation of the doctrine of extinctive prescription (prescription libératoire) in international law has been widely – albeit not unanimouslyFootnote 164 – recognised as a general principle of law in the meaning of Article 38(1)(c) of the ICJ Statute.Footnote 165 It is based on considerations of equity and fairness due to the respondent,Footnote 166 much like the “affirmative defence” found in Anglo-American systems (doctrine of laches) with roots in Roman law.Footnote 167 As a result, in the absence of a treaty-defined period within which an international claim must be brought, the doctrine leaves significant discretion to the adjudicator.Footnote 168 The requirements that must be established are not consistently defined. Three of them are recurrent in discussions of extinctive prescription and can be considered as its core, namely: (i) an unreasonable delayFootnote 169 in the presentationFootnote 170 of the claim without a valid justification;Footnote 171 (ii) the delay must have placed the respondent at a disadvantage in defending itself;Footnote 172 and (iii) the invocation of the extinctive prescription by the [Page 41] respondent.Footnote 173 Other requirements concern the nature of the underlying obligationFootnote 174 or the availability of a sufficient factual record to the respondent,Footnote 175 but they can both be seen as extensions of either the reasonableness of the delay (e.g. a State may withhold an action to assert a territorial claim for over a century) or potential disadvantage of the respondent (which is limited if the latter keeps a factual record).

54. The allocation of the burden of proof for extinctive prescription is less settled than for estoppel and acquiescence. In E energija v. Latvia, the tribunal implied that the burden was on the respondent, but the relevant paragraphFootnote 176 is ambiguous and could also be interpreted as placing the burden on the claimant (with the respondent failing to “rebut” the claimant’s argument). A claimant must establish that its action is timely, i.e. brought within the specified deadline to do so;Footnote 177 yet, the respondent is required to raise this objection or it is forgone. The allocation of the burden of proof thus finds support in two different rationales, which however point in opposite directions.

55. The case relied upon in E energija v. Latvia on this issue, namely Grand River v. United States, is of limited help. It focused on a treaty-defined three-year limitation period (under Articles 1116(2) and 1117(2) of the NAFTA) and, disappointingly, it expressly refused to take a position on the question of the burden of proof.Footnote 178 In practice, it placed it on the respondent.Footnote 179 Similarly, in Mercer v. Canada, the tribunal did not take a clear stance on the allocation of the burden of proof, although it seemed to place it on the respondent for the issue of constructive knowledge.Footnote 180

56. The approach in these two cases is inconsistent with that of other investment tribunals. The tribunal in Philip Morris v. Uruguay noted in relation to the allocation of the burden of proving the exhaustion of local remedies that “this is a condition that has to be satisfied prior to asserting a denial of justice claim. It is for the Claimants to show that this condition has been met or that no remedy was [Page 42] available giving ‘an effective and sufficient means or redress’ or that, if available, it was ‘obviously futile’.”Footnote 181 Although the exhaustion of local remedies is distinct from the timeliness of the action, it provides a useful indication of how the allocation should be made. A more specific indication of the allocation was made by the tribunal in Spence v. Costa Rica in the context of Article 10.18.1 of the CAFTA:

If the Claimants cannot establish, to an objective standard, that they first acquired knowledge of the breaches and losses that they allege in the period after 10 June 2010, they fall at the first hurdle. To surmount this obstacle, each claimant must show, in respect of each property claim, that they have a cause of action, a distinct and legally significant event that is capable of founding a claim in its own right, of which they first became aware in the period after 10 June 2010.Footnote 182

57. A distinction should thus be drawn between actual and constructive knowledge. The burden of proving the former falls with the claimant, whereas the latter may be allocated to the respondent, together with a requirement of diligence from the claimantFootnote 183 and a presumption that information in the public domainFootnote 184 or in the hands of a company belonging to the same economic group as the investor is constructively expected to be known by the claimant.Footnote 185

Abuse of Right

58. In international law, the doctrine of abuse of right (or abus de droit) is an expression of the well-established principle of good faith.Footnote 186 In Orascom v. Algeria, which is reported in this volume, the tribunal made a concise but illuminating application of this doctrine in a context (a multiplicity of legal suits brought against the same State by several vertically connected companies under the same overall control) different from those in which the doctrine has most frequently featured in commercial arbitration, e.g. the allegedly abusive exercise of a contractual right,Footnote 187 and investment arbitration, i.e. a corporate restructuring effected for the sole purpose of benefiting from the protection of a treaty at a time when the dispute is already foreseeable.

59. In the investment context, the objection has been sometimes formulated as an abuse of process in two different ways. The first is to consider that the investment itself is – through the restructuring – made abusively and, due to the absence of good faith, there is no investment. Such is the approach followed in Phoenix v. Czech Republic, where the tribunal concluded that there was no investment to be protected.Footnote 188 Another approach is to consider that, even if there is technically a qualifying investment, it does not “deserve” the protection of the treaty and an action seeking such protection is an inadmissible abuse of the right to bring an [Page 43] action. Such is the approach followed in Philip Morris v. Australia, where the claimant made a restructuring of its corporate structure after the dispute (relating to the adoption of a plain packaging measure by Australia affecting the claimant’s cigarette business) had become foreseeable.Footnote 189 The tribunal set the following test: