Training in the psychiatry of learning disability or in child and adolescent psychiatry is now a requirement for membership of the Royal College of Psychiatrists. As a group of experienced senior house officers embarking on learning disability placements, we had anticipated the need to adapt previously acquired skills in psychiatric practice to this particular patient group. However, there was a realisation, acknowledged during informal peer support meetings, that we were not prepared for uncomfortable feelings regarding our placements - feelings that were common to us all. Specifically, these related not to disillusionment with the practicalities of the job, but rather to sensations within the individual that were difficult to handle: impotence, hopelessness and disempowerment.

There is currently little evidence within this field, although the concept of carer attitude to difficult patients is not new - take, for example, malignant alienation (Reference Watts and MorganWatts & Morgan, 1994). Maltsberger & Buie (Reference Maltsberger and Buie1974) also talked about the narcissistic snares related to caregiving: ‘to know all, to heal all, to love all’.

Ouellette-Kuntz et al (Reference Ouellette-Kuntz, Burge and Hendry2003), in studying the attitudes of psychiatric trainees, commented that, because trainee attitudes towards certain patient groups have been found to influence the choice of specialisation and influence the therapeutic relationship (Benham et al, 1988), it is important to consider trainee psychiatrists attitudes towards learning disability when preparing them to work in this area.

This study aimed to formally examine the attitudes and emotions engendered in a group of senior house officers (SHOs) working in learning disability psychiatry, by means of focus groups held both during and immediately after the placement.

Method

Focus groups have been shown to be an effective technique for exploring the attitudes and needs of staff (Reference Denning and VerscheldenDenning & Verschelden, 1993), and are a way of both debating a particular set of issues and of using the group interaction explicitly as part of the research data.

Four SHOs working in learning disability placements participated in three focus group meetings held over a 6-week period. The groups were facilitated by an independent consultant psychotherapist, who reflected on themes raised during the session and elaborated on these during subsequent sessions. Each session was 90 minutes long, and was recorded on both audio- and video-tape. One session included the use of plasticine model-making, to explore non-verbal elements to emotion. The audiotapes were fully transcribed to provide raw data for further analysis. Analysis of data required categorisation of responses in terms of the feelings expressed, the thoughts identified, and the behaviours described and revealed during the sessions.

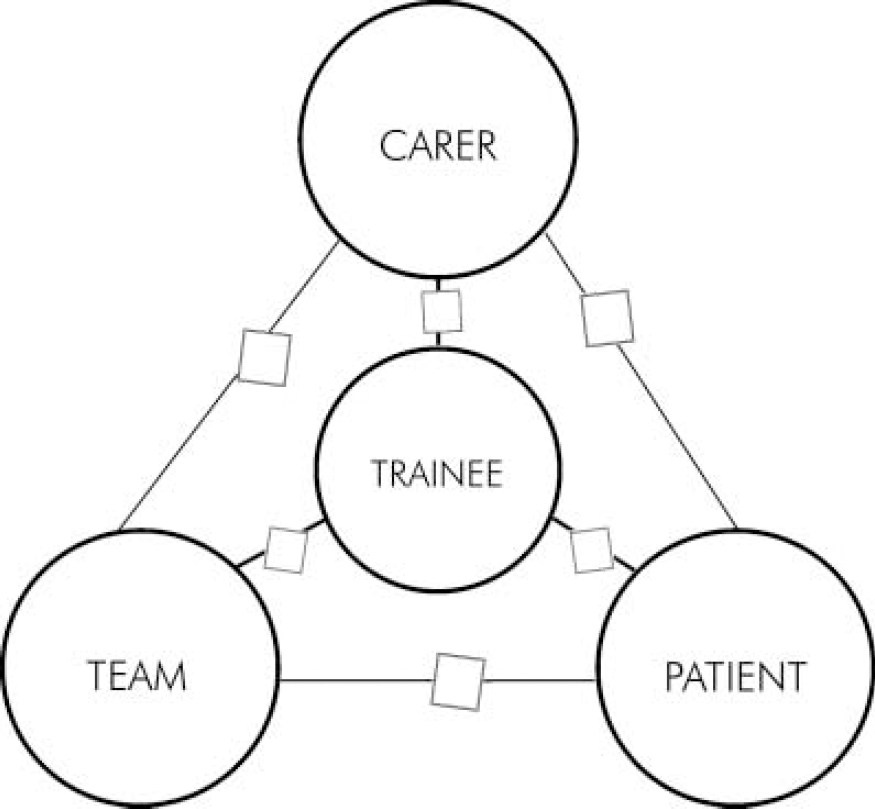

Each participant analysed the transcripts independently, to minimise the chance of one individual unduly influencing the responses of the others. The individual analyses were then summed into a collective model representing the interrelationships among trainees, patients, carers and other members of the multidisciplinary team.

To provide a visual representation of these inter-relationships, a three-dimensional model was built based on the structure illustrated in Fig. 1. Handwritten notes of thoughts, feelings and behaviours (extracted from the transcripts) were attached to threads linking the four different poles - trainees, patients, carers and colleagues.

Fig. 1. Model of the interrelationships between trainees, patients, carers and colleagues.

Results

The results revealed a number of themes - in particular, the preponderance of negative thoughts, feelings and behaviours originating from the trainees and directed towards themselves and patients (Table 1). In addition, negative feelings were expressed directed towards their colleagues, but less so towards the carers of patients. The trainees perceived themselves to be the recipients of positive thoughts, feelings and behaviours infrequently (only twice during the whole process).

Table 1. Quantitative analysis of themes expressed during focus groups

| Thoughts | Feelings | Behaviours | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Origin of thoughts/feelings/behaviours | Directed towards | Positive | Negative | Positive | Negative | Positive | Negative |

| Trainee | Trainee | 0 | 10 | 0 | 31 | 0 | 16 |

| Patient | 0 | 6 | 4 | 11 | 1 | 4 | |

| Carer | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| Colleagues | 0 | 3 | 1 | 7 | 2 | 2 | |

| Patient | Trainee | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| Patient | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 1 | |

| Carer | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Colleagues | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Carer | Trainee | 0 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 3 |

| Patient | 0 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 5 | |

| Carer | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | |

| Colleagues | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Colleagues | Trainee | 0 | 5 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 7 |

| Patient | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 5 | |

| Carer | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Colleagues | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

Examples of negative thoughts, feelings and behaviours directed from the trainees towards themselves included the following:

-

• Being unequal to the job - ‘I didn't feel particularly skilled in knowing what to do’.

-

• Being ill-equipped for the task in hand, and being ill-suited and lacking in personal skills - ‘as if you’re set up to fail’ and ‘ the fear that there's something wrong with you’.

-

• Hopelessness - ‘whatever I do, it's not going to make much difference’.

-

• Deception - ‘I felt I was playing a part’.

-

• Helplessness and inadequacy - ‘I just don't feel qualified or skilled, or able to do it’.

-

• Dislocation - ‘the fear that there's something wrong with you’ and ‘I don't have the same feelings of connectedness to people I’ve been seeing over the past few months, it doesn't feel that there are common aspects in our lives’.

-

• Powerlessness and futility with regard to both the post and patient outcome - ‘I said I’d come back in a month's time, but then I thought I’ll go back and nothing will have changed’.

-

• Escape - ‘it was all so awful, I just wanted to go away and have nothing to do with it, and that made me feel dreadful about myself’.

-

• Avoidance, withdrawal and reduced communication - ‘I was trying my best to communicate’ and ‘no one has taught me to deal with people who can't speak’.

-

• Depression - ‘I was dreary - I stopped talking to people, I stopped talking to other members of the team, I just went in, went to my office, did my job and went home’.

-

• Restriction - ‘this terrible sense of being oppressed by people least likely to be oppressive… who are oppressed themselves’.

Other significant themes to emerge in the analysis of the transcripts included:

-

• Identification - ‘what we were feeling was perhaps what it might be like to have learning disabilities’.

-

• Emotional ‘cost’ of placement - ‘it wasn't necessarily the subject per se that was difficult and unattractive, but it was the feelings that it aroused’.

Discussion

The results of this study confirmed that the initial feelings of impotence, hopelessness, disempowerment and feeling unskilled in this specialty were shared by all members of the study group. In addition, there appeared to be a sense of alienation, both from the patients and from other learning disability professionals. In this sense our experience resonated with the process of malignant alienation as described by Watts & Morgan (Reference Watts and Morgan1994). One of the strategies that Watts & Morgan identified for preventing and managing malignant alienation was to promote a working environment in which any negative feelings in the staff could be acknowledged openly and shared. In our experience there seemed to be no such forum available. Furthermore, it may be that some of the reticence to discuss our difficulties was fuelled by a degree of both professional and political correctness - there seemed to be a professional etiquette that prohibited the expression of negative feelings regarding patients and carers.

The need to care for patients may encourage unrealistic expectations in staff that they can treat all aspects of the individual. Perhaps as a trainee there is even more expectation that a new face may bring with it new ideas and magical cures. In many areas of psychiatry such hopes are likely to be unfulfilled, disappointing the patient, the carer and the professional involved, thus facilitating negative countertransference towards the patient (Reference Maltsberger and BuieMaltsberger & Buie, 1974; Reference Watts and MorganWatts & Morgan, 1994).

In the current climate of increasing consultant vacancies, both generally and specifically in learning disability, it may be that addressing these negative experiences as a potential problem could enrich trainees’ experiences of their learning disability placements and result in improved recruitment to and retention within the specialty. Whatever the wider implications for psychiatry, it must surely be important that it is made easier for staff to express their feelings about patients. By means of a Balint group, for example, they could gain insight into their own vulnerabilities and expectations as professionals in the caring role in a well-supervised and supportive environment (Reference Watts and MorganWatts & Morgan, 1994).

A possible criticism of this study is that the experiences we had were isolated phenomena, not replicated across other training schemes, or indeed by other SHO cohorts within the same scheme. Allied to this is the fact that the study did not take into account the attitudinal disposition of the SHOs participating, which might have influenced the emotions expressed. Further work in this area could incorporate the administration of personality inventories to those involved. This might identify certain types of trainee who would be more suited to this particular specialty.

The work could also be extended to SHO training posts in all psychiatric subspecialties. Generally there is scant literature looking specifically at trainees’ emotional experience of psychiatry, either in isolation, or in comparison with other medical specialties.

Declaration of interest

None.

Acknowledgements

Thanks for their advice and supervision are due to Dr Ray Brown, Consultant Psychotherapist, Barrow Hospital, Mr Graham Parton, Pharmacist, Blackberry Hill Hospital and Dr Shirley Radford, Psychologist, Fromeside Clinic, Blackberry Hill Hospital.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.