Comorbid anxiety is common in depressive disorders, both in middle and in later life. In community samples of younger adults with depression, the point prevalence of comorbid anxiety disorders ranged from 33% (Reference FlintFlint, 1994) to 51% (Reference Kessler, Nelson and McGonagleKessler et al, 1996), with a 46% point prevalence in a clinical sample (Reference Fava, Alpert and CarminFava et al, 2004). In community samples of older adults with late-life depression, the point prevalence of comorbid anxiety disorders ranged from 26% (Reference Ben-Arie, Swartz and DickmanBen-Arie et al, 1987) to 48% (Reference Beekman, de Beurs and van BalkomBeekman et al, 2000). In clinical samples of older patients with late-life depression, comorbid anxiety disorders were diagnosed in 3% to 65% (Reference Parmalee, Katz and LawtonParmalee et al, 1993; Reference Mulsant, Reynolds and ShearMulsant et al, 1996; Reference Lenze, Mulsant and ShearLenze et al, 2000).

Beyond the high rates of coexistence, comorbid anxiety has been often cited as a clinically relevant problem owing to its impact on acute treatment response in late-life depression. Thus, several studies have found that greater severity of anxiety symptoms is associated with an increased risk of withdrawal from treatment (Reference FawcettFawcett, 1997; Reference Flint and RifatFlint & Rifat, 1997a ), a decreased response to acute antidepressant treatment (Reference FawcettFawcett, 1997; Reference Flint and RifatFlint & Rifat, 1997a ; Reference Steffens and McQuoidSteffens & McQuoid, 2005), and a longer time to both response (Reference Mulsant, Reynolds and ShearMulsant et al, 1996; Reference Dew, Reynolds and HouckDew et al, 1997; Reference Lenze, Mulsant and DewLenze et al, 2003) and remission (Reference Clayton, Grove and CoryellClayton et al, 1991; Reference Alexopoulos, Katz and BruceAlexopoulos et al, 2005).

Although the impact of anxiety on response and recurrence of major depression has been previously studied extensively in general adult populations, its relevance to long-term treatment response in late-life depression has received much less attention (Reference Lebowitz, Pearson and SchneiderLebowitz et al, 1997; Reference Charney, Reynolds and LewisCharney et al, 2003) and has not been examined in a controlled maintenance trial. Maintenance outcomes in late-life depression and the factors that moderate those outcomes are critical, given the brittle nature of response in this age group (Reference Reynolds and LebowitzReynolds & Lebowitz, 1999; Reference Reynolds, Dew and PollockReynolds et al, 2006). To our knowledge, the only published data addressing these long-term outcomes were obtained during a 2-year naturalistic follow-up study. In this uncontrolled study, pre-treatment anxiety symptoms were not related to time to recurrence during 2 years of open pharmacotherapy trial with nortriptyline (Reference Flint and RifatFlint & Rifat, 1997b ).

Thus, given the high recurrence rate of late-life depression (Reference Zis, Grof and WebsterZis et al, 1980) and the increased morbidity and mortality risks associated with this disorder (Ganguli et al, Reference Ganguli, Belle and Ratcliff1993, Reference Ganguli, Dodge and Mulsant2002; Reference Reynolds, Frank and PerelReynolds et al, 1994), as well as the lack of controlled data regarding the impact of pre-treatment anxiety on its long-term treatment, further examination of anxiety as a predictor not only of response but of recurrence would greatly benefit clinicians in planning treatment. Accordingly, we conducted an analysis to assess whether pre-treatment comorbid anxiety predicts treatment outcomes during both acute and maintenance treatment of major depression in old age. Our hypothesis was that greater pre-treatment severity of anxiety symptoms would predict poor treatment outcome, including both a longer time to response during acute treatment, and an increased rate of – and shorter time to – recurrence during maintenance treatment.

METHOD

Data for this analysis were provided by the second study of Maintenance Therapies in Late-Life Depression conducted at the University of Pittsburgh Intervention Research Center for the Study of Late-Life Mood Disorders between 1999 and 2004. Details of the study protocol are described elsewhere (Reference Reynolds, Dew and PollockReynolds et al, 2006). In brief, participants were aged 70 years or older, with a diagnosis per Structured Clinical Interview for DSM–IV (SCID; Reference First, Gibbon and WilliamsFirst et al, 1995) of non-psychotic, non-bipolar major depressive disorder (single episode or recurrent), a score on the 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD; Reference HamiltonHamilton, 1960) of 15 or higher, and a Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE; Reference Folstein, Folstein and McHughFolstein et al, 1975) score of 17 or higher.

In the acute phase, patients received open pharmacotherapy and weekly interpersonal psychotherapy (Reference Klerman, Weissman and RounsavilleKlerman et al, 1984) until they achieved response (defined as a HRSD score of 10 or less for three consecutive weeks). Pharmacotherapy consisted of paroxetine started at 10 mg/day and titrated as necessary up to a maximum of 40 mg/day. Adjunctive pharmacotherapy with bupropion, nortriptyline or lithium was used when required to achieve response (n=69). Adjunctive lorazepam (0.5–2 mg/day) was also used in 65 patients.

Patients who responded to acute treatment entered 16 weeks of continuation treatment to stabilise their response; they received the same pharmacotherapy and interpersonal psychotherapy every 2 weeks. Patients who maintained response during continuation treatment were then randomly assigned to one of four maintenance treatments:

-

(a) pharmacotherapy plus monthly clinical management visits;

-

(b) placebo plus monthly clinical management visits;

-

(c) pharmacotherapy plus monthly maintenance interpersonal psychotherapy;

-

(d) placebo plus monthly maintenance interpersonal psychotherapy.

Patients randomised to pharmacotherapy received paroxetine (with adjunctive medication if required) for the remainder of their study participation. Patients randomised to receive placebo had paroxetine (and adjunctive medication) slowly tapered over 6 weeks under double-blind conditions. All patients were allowed to remain on a stable dosage of lorazepam if it had been required during the acute or continuation treatment phases. Patients remained in maintenance therapy for 2 years or until recurrence of a major depressive episode. Recurrence required a HRSD score of 15 or over, meeting DSM–IV criteria (American Psychiatric Association, 1994) for a major depressive episode during a SCID interview, and confirmation of the diagnosis by an independent geriatric psychiatrist. Assessors were unaware of treatment assignment. All patients provided written informed consent. For this data analysis we collapsed the interpersonal psychotherapy and non-psychotherapy groups because this therapy was not shown to prevent recurrence in the primary outcome analysis, whereas paroxetine was (Reference Reynolds, Dew and PollockReynolds et al, 2006).

Symptoms of anxiety were measured using the self-report anxiety scale from the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI; Reference Derogatis and MelisaratosDerogatis & Melisaratos, 1983). The BSI is a validated self-report scale developed from the Symptom Checklist 90 – Revised (SCL–90–R; Reference DerogatisDerogatis, 1983) with strong test–retest and internal consistency reliabilities. Factor analytic studies of the internal structure of the scale have demonstrated its construct validity (Reference DerogatisDerogatis, 1983). The anxiety sub-scale consists of six items: ‘nervousness or shakiness inside’, ‘suddenly scared for no reason’, ‘feeling fearful’, ‘feeling tense or keyed up’, ‘spells of terror or panic’ and ‘feeling so restless you couldn't sit still'. Each item is rated on a five-point scale (0 symptom not present, 4 extremely severe). We used both a categorical and a continuous form of the BSI anxiety measure. We analysed BSI scores (Cronbach's α=0.84 for the present sample) on a continuum and also we also dichotomised those with higher v. lower anxiety by using a median split (median value for the sample 1.0). We present in this paper the results based on the categorical approach because it has more relevance to the categorical decisions clinicians are faced with in their practice.

The analyses included data on 181 persons who participated in the acute treatment phase. Of these, 116 maintained response during continuation treatment and were randomly assigned to maintenance treatment. Pre-treatment BSI scores were available on 170 participants entering the acute phase. Of these, 109 participated in randomly assigned maintenance treatment.

Statistical analysis

We used Kaplan–Meier survival analysis to assess the effect of pre-treatment anxiety symptoms (BSI scores) on time to response. In order to analyse the influence of lorazepam on time to response (Reference Buysse, Reynolds and HouckBuysse et al, 1997), we compared the time to response in the group receiving lorazepam v. the group not receiving lorazepam. Further, we stratified the sample based on presence or absence of lorazepam use. In order to control for other potential confounders, we subsequently fitted Cox proportional hazards models for each outcome, stratifying on severity of depression to estimate the unique effects of anxiety on acute treatment outcomes. We controlled for baseline depression severity as measured by the HRSD scores, with the four anxiety-related items (9, 10, 11 and 15) removed (Reference Dew, Reynolds and HouckDew et al, 1997; Reference Gildengers, Houck and MulsantGildengers al, 2005; Reference Dombrovski, Mulsant and HouckDombrovski et al, 2007).

To assess the effect of comorbid symptomatic anxiety on time to recurrence during maintenance treatment, we stratified the sample based on randomisation to paroxetine or placebo and performed Kaplan–Meier analyses in four groups: pharmacotherapy with lower BSI scores (n=35); pharmacotherapy with higher BSI scores (n=23); placebo with lower BSI scores (n=31); and placebo with higher BSI scores (n=20).

RESULTS

Participants' baseline demographic and clinical characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1 Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients by level of Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) anxiety scores

| Variable | BSI score | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower BSI (n=88) | Higher (n=82) | t or χ2 | d.f. | P | ||

| BSI score: mean (median) | 0.53 (0.58) | 1.91 (1.75) | 17.06 | 124 | <0.0001 | |

| Current age, years: mean (s.d.) | 76.3 (5.3) | 77.1 (5.7) | –0.94 | 168 | 0.35 | |

| Female, % (n) | 58 (51) | 72 (59) | 3.64 | 1 | 0.06 | |

| White, (n) | 93 (82) | 91 (75) | 0.18 | 1 | 0.67 | |

| Education level, years: mean (s.d.) | 12.9 (2.9) | 13.0 (2.9) | –0.18 | 168 | 0.85 | |

| CIRS–G score: mean (s.d.) | 10.2 (3.6) | 9.8 (4.4) | 0.61 | 168 | 0.54 | |

| HRSD score: mean (s.d.) | ||||||

| HRSD–17 1 | 19.2 (3.2) | 22.2 (3.5) | –6.06 | 168 | <0.0001 | |

| HRSD minus anxiety items (Q9, Q10, Q11, Q15) | 14.2 (2.6) | 16.1 (2.9) | –4.42 | 158 | <0.0001 | |

| Age at onset of first episode of depression, years: mean (s.d.) | 63.1 (17.8) | 60.7 (19.4) | 0.85 | 168 | 0.39 | |

| Patients with first episode, % (n) | 61 (54) | 45 (37) | 4.50 | 1 | 0.03 | |

| Duration of current episode, weeks: mean (s.d.) 2 | 128.1 (230.4) | 89.3 (174.7) | 1.13 | 168 | 0.26 | |

| Patients receiving adjunctive lorazepam during acute phase, % (n) | 23 (20) | 52 (43) | 16.06 | 1 | <0.0001 | |

| Lorazepam dosage, mg/day | ||||||

| Mean (s.d.) | 0.92 (0.44) | 1.03 (0.60) | –0.75 | 61 | 0.45 | |

| Median | 0.88 | 1.0 | ||||

| Range | 0.5–2.0 | 0.25–3.0 | ||||

| Patients with a comorbid diagnosis of any anxiety disorder at baseline, % (n) | 23 (20) | 40 (32) | 5.4 | 1 | 0.02 | |

| Paroxetine dosage at the end of acute phase, mg/day | –1.27 | 168 | 0.20 | |||

| Mean (s.d.) | 24.2 (10.4) | 26.3 (10.9) | ||||

| Median | 20 | 30 | ||||

| Range | 10–45 | 5–40 | ||||

CIRS–G, Cumulative Illness Rating Scale for Geriatrics; HRSD, Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression

1. 17-item version of the HRSD

2. Natural log used in the analyses; means and standard deviations reported in their original units

Effect of symptomatic comorbid anxiety on response during acute treatment

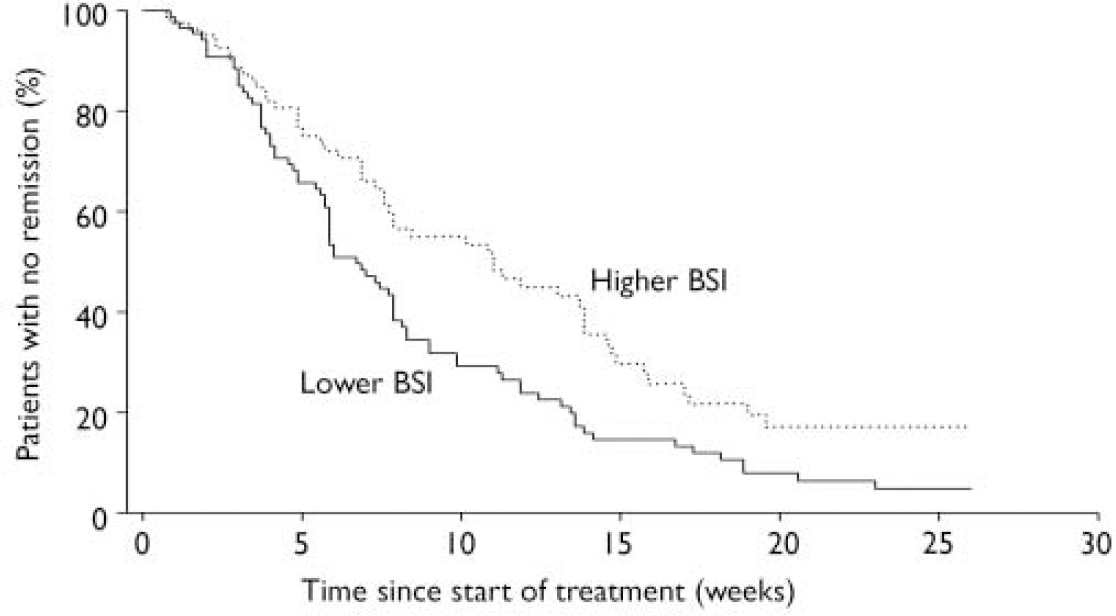

At baseline, 82 patients had higher BSI scores (above the median split) and 88 had lower BSI scores. Among patients with higher BSI scores, 52% (n=43) achieved response and began maintenance treatment; among those with lower BSI scores 75% (n=66) achieved response and began maintenance treatment (χ2=6.09, d.f.=1, P=0.01) (Table 2). Patients with higher BSI scores had a median time to response significantly longer than those with lower scores (Fig. 1): 11.0 (95% CI 7.7–13.9) v. 6.7 (95% CI 5.9–7.9) weeks (Wilcoxon χ2=6.26, d.f.=1, P=0.01).

Fig. 1 Anxiety symptoms and time to response: patients with greater severity of symptoms at baseline averaged 4.3 weeks longer response time (BSI, Brief Symptom Inventory).

Table 2 Participants with higher v. lower Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) score in each outcome group

| Entered maintenance phase (achieved response) | Completed study (no recurrence) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| On medication (n) | On placebo (n) | Total (n) | ||||

| Higher BSI at baseline (n=82) | 43 | 5 | 3 | 8 | ||

| Lower BSI at baseline (n=88) | 66 | 17 | 8 | 25 | ||

Effects of adjunctive lorazepam

Patients who received adjunctive lorazepam (n=65) had a median time to response significantly longer than those who did not (n=120): 12.4 weeks (95% CI 8.4–14.7) v. 6.9 weeks (95% CI 5.6–7.9); Wilcoxon χ2=16.81, d.f.=1, P<0.0001. The mean daily dosage of lorazepam received by patients with higher or lower BSI scores did not differ significantly: 1.03 mg (s.d.=0.60) v. 0.92 mg (s.d.=0.44); t=–0.75, d.f.=61, P=0.45. However, as would be expected, lorazepam use was correlated with higher BSI scores (phi=0.31). Therefore, we analysed post hoc the time to response separately in patients who received and did not receive lorazepam, contrasting those with higher and lower BSI scores. Among patients who received lorazepam, those with higher BSI scores had a median time to response significantly longer than those with lower scores: 13.9 weeks (95% CI 11.0–17.1) v. 7.9 weeks (95% CI 5.9–13.6); Wilcoxon χ2=4.48, d.f.=1, P=0.03. Among patients who did not receive lorazepam, the difference in time to response between patients with higher v. lower BSI scores was not significant (Wilcoxon χ=0.0858, d.f.=1, P=0.77). The mean final daily dosage of paroxetine received by patients with higher or lower BSI scores did not differ: 26.3 mg (s.d.=10.9) v. 24.2 mg (s.d.=10.4) (t=–1.27, d.f. =168, P=0.21). The effect of symptomatic anxiety on time to response remained significant in our Cox model, stratifying on baseline HRSD score (minus anxiety items): hazard ratio 0.65, (95% CI 0.45–0.93), P=0.02.

Effect of symptomatic comorbid anxiety on recurrence during maintenance treatment

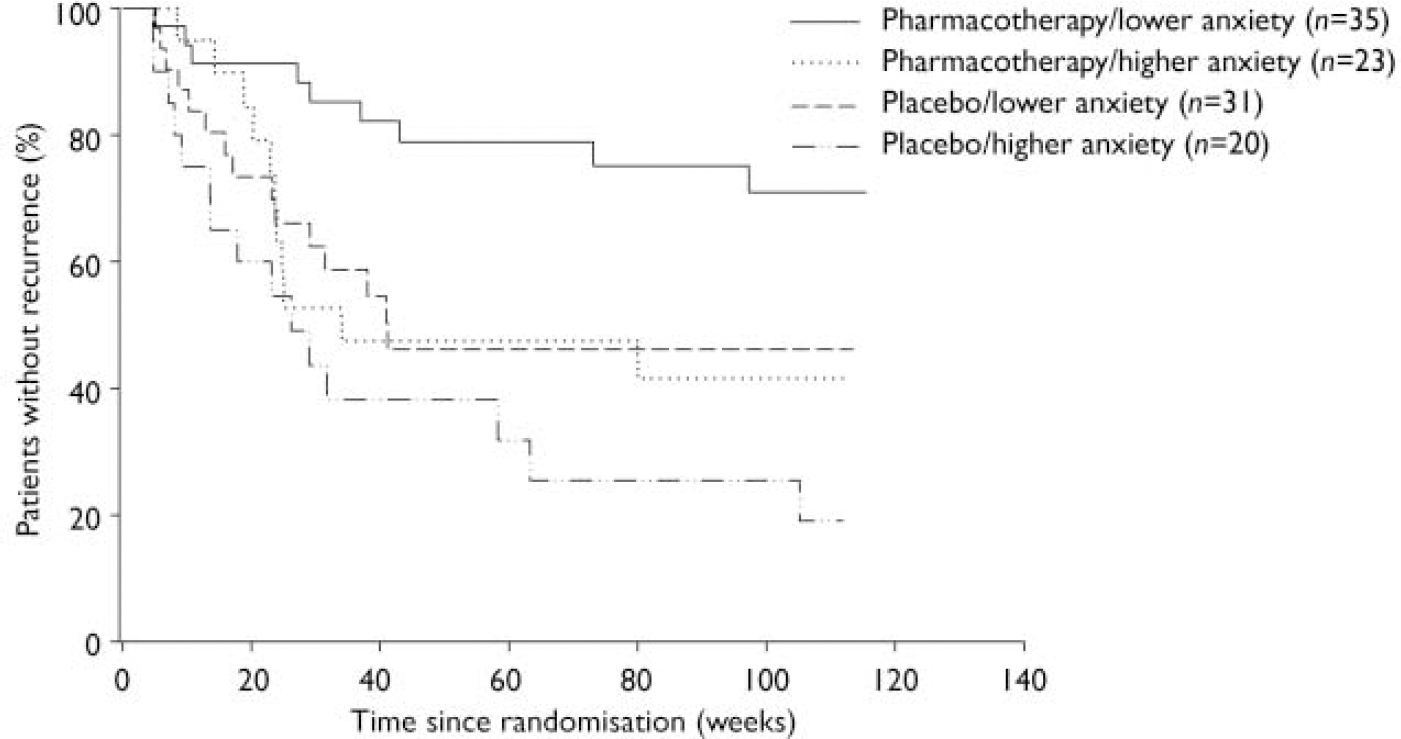

A higher BSI score predicted an increased rate of recurrence (Wald χ2=7.05, d.f.=1, P=0.008; 95% CI hazard ratio 1.22–3.72). Time to recurrence from randomisation (Fig. 2) differed across the four groups, with the higher BSI group having a shorter time to recurrence (log-rank χ2=15.00, d.f.=3, P=0.002). Recurrence rates (adjusting for censoring) were 29% (pharmacotherapy with lower BSI scores), 58% (pharmacotherapy with higher BSI scores), 54% (placebo with lower BSI scores) and 81% (placebo with higher BSI scores). Among patients receiving pharmacotherapy, time to recurrence was significantly shorter for those with higher BSI scores than for those with lower scores (log-rank χ2=5.66, d.f.=1, P=0.02). Among patients given placebo, time to recurrence did not differ significantly between those with higher or lower BSI scores (log-rank χ2=2.54, d.f.=1, P=0.11). Among patients with higher BSI scores, time to recurrence did not differ between those given placebo or paroxetine (log-rank χ2=1.95, d.f.=1, P=0.16). Among patients with lower BSI scores, time to recurrence was significantly shorter for those in the placebo group than for those taking paroxetine (log-rank χ2=5.28, d.f.=1, P=0.02).

Fig. 2 Comorbid anxiety symptoms and time to recurrence.

Because these findings suggested a moderator effect of anxiety, a separate Cox regression examined the possible moderator effect of anxiety (measured by BSI) on maintenance treatment outcomes, by analysing the interaction between BSI scores and pharmacotherapy. The results did not confirm a moderator effect (χ2=0.49, d.f.=1, P=0.48). The power to detect a moderator effect was low (0.22) and the hazard ratio for the interaction was 1.5 (95% CI 0.48–4.68).

We repeated the analysis for both acute and maintenance phases using BSI score as a continuous measure, with similar results (further details available from the authors).

DISCUSSION

Summary of findings

Our study is the first to show that high pretreatment levels of anxiety symptoms increase not only the risk of non-response in acute treatment of late-life depression but also the risk of recurrence of the disorder in the first 2 years after response to treatment. In other words, elderly patients who start treatment with more severe anxiety have both a poorer acute response and a more brittle long-term response to pharmacotherapy. These results demonstrate a strong negative impact of anxiety symptoms on short- and long-term outcomes of depression in old age, even with optimal treatment. These findings for acute treatment effects confirm previous reports (Reference Mulsant, Reynolds and ShearMulsant et al, 1996; Reference Dew, Reynolds and HouckDew et al, 1997; Reference Flint and RifatFlint & Rifat, 1997a ) that greater pre-treatment anxiety is associated with poorer response during acute treatment of late-life depression. We also found that these comorbid anxiety symptoms increase the risk of recurrence. To our knowledge, only one previous uncontrolled follow-up study has examined the impact of comorbid anxiety on long-term outcome of late-life depression: in this naturalistic study, pre-treatment anxiety did not predict time to recurrence (Reference Flint and RifatFlint & Rifat, 1997b ).

We found that patients with higher BSI scores and adjunctive lorazepam treatment had increased time to response. The use of lorazepam per se probably did not prolong time to response, because patients receiving adjunctive lorazepam but having lower BSI scores had similar time to response as patients not receiving adjunctive lorazepam. This observation is consistent with our previous study (Reference Buysse, Reynolds and HouckBuysse et al, 1997), which reported that adjunctive lorazepam did not slow the antidepressant response in elderly patients with depression. However, patients with higher BSI scores not receiving adjunctive lorazepam had a shorter time to response than those with higher scores who received lorazepam. One possible explanation that deserves further exploration is that the patients with higher BSI scores who needed adjunctive lorazepam differed clinically from the patients with higher scores who did not need adjunctive lorazepam. This difference might be related to a higher preponderance of symptoms of general anxiety disorder in the group who needed adjunctive lorazepam, as general anxiety disorder more often than other anxiety disorders is associated with worse outcomes (Reference Beekman, de Beurs and van BalkomBeekman et al, 2000; Reference Lenze, Mulsant and ShearLenze et al, 2000).

Strengths and limitations

Our study was limited in its power to detect a moderator effect – that is, interactions between treatment and coexisting anxiety. We were able to detect main effects of pharmacotherapy and of anxiety on recurrence, but the study lacked sufficient power to detect interaction between pharmacotherapy and anxiety.

This study is the first randomised controlled trial to demonstrate the limited efficacy of standard pharmacotherapy in late-life depression with coexisting anxiety to make and keep patients well. It is important to emphasise that patients treated in this study received intensive management, with clinicians and psychiatrists reviewing cases weekly and refining treatment plans to minimise attrition and maximise response. Also, adjunctive pharmacotherapeutic strategies, which were instrumental in many patients achieving response and which were continued during the maintenance phase, were still not enough to protect most patients with comorbid anxiety from recurrence of depression. Even under these intensive treatment conditions, which go well beyond regular clinical care, comorbid anxiety had a prominent negative effect on acute and long-term outcomes.

Future directions

Overall, our findings suggest limited efficacy of current medications with regard to mitigating the impact of comorbid anxiety on response and recurrence, even though selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (such as paroxetine, used in this study) are indicated for the treatment of both anxiety and depression. It is also worth noting that adding lorazepam to paroxetine in cases of patients with higher anxiety did not improve outcomes. Alternative treatment options should be considered for these patients. Given the detrimental effect of anxiety on long-term course of depression and the limited benefit demonstrated here even with optimal treatment, clinicians are left with the challenge of deciding what they can do to improve outcome in this group of patients (Reference Tyrer, Seivewright and JohnsonTyrer et al, 2004). Expert consensus guidelines (Reference Alexopoulos, Katz and ReynoldsAlexopoulos et al, 2001) recommend maximising the dosage of antidepressant. It is possible that dosages of paroxetine higher than those used in this study would have yielded better outcomes in anxious patients (Reference Baldwin and PolkinghornBaldwin & Polkinghorn, 2005). However, older adults may not tolerate high doses of antidepressants, given the frequent medical comorbidity and sensitivity to medications' side-effects in this population. Further research involving possible pharmacological alternatives such as adjunctive use of second-generation antipsychotic agents (Reference Adson, Kushner and FahnhorstAdson et al, 2005; Reference Wetherell, Lenze and StanleyWetherell et al, 2005a ) as well as learning-based psychotherapies such as problem-solving therapy and cognitive–behavioural therapy (Reference Stanley, Beck and NovyStanley et al, 2003; Reference Wetherell, Sorrell and ThorpWetherell et al, 2005b ) is warranted.

In conclusion, replicating and extending the results of previous studies, our findings indicate a need for active identification and aggressive treatment of anxiety symptoms in late-life depression, as well as the need for further research to identify optimal treatment. In order to improve outcomes in elderly patients with anxious depression, we need to develop and test treatment algorithms that would involve both psychosocial and pharmacological alternative treatments.

Acknowledgements

The study was supported by National Institute of Mental Health grants P30 MH52247, P30 MH071944, R37 MH43832, K24 MH069430 and R01 MH37869 and Project EXPORT at the Center for Minority Health, Graduate School of Public Health, University of Pittsburgh, NIH/NCMHD P60 MD-000-207; GlaxoSmith Kline donated supplies of paroxetine. E.J.L. has received grant support from Forest Laboratories, Pfizer Inc. and Johnson & Johnson Co. B.H.M. has received honoraria and/or research support from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Forest Laboratories, GlaxoSmith Kline, Lundbeck and Pfizer. B.G.P. has received honoraria and/or research support from Janssen Pharmaceutica, Forest Laboratories, GlaxoSmith Kline and Solvay and is on the speakers' bureaux of Forest Pharmaceuticals and Sepracor. M.D.M. is on the speakers' bureaux and also has also has been a consultant for Forest Pharmaceuticals and GlaxoSmith Kline. C.F.R. has received research support from GlaxoSmith Kline, Pfizer izer Inc., Eli Lilly, Bristol-Meyers Squibb and Forest Pharmaceuticals.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.