Overweight and obesity remain a major public health concern, particularly for children and young people. In New Zealand, more than one-third of secondary-school students are overweight or obese; among young people living in the most deprived areas, the prevalence is nearly 50 %(Reference Utter, Denny and Crengle1). Weight-control behaviours are also common among adolescents, especially among those who are overweight(Reference Neumark-Sztainer, Story and Hannan2, Reference Utter, Denny and Percival3). However, little is known about the prevalence of successful weight loss and associated behaviours among adolescents in population-based studies. This type of information has been routinely collected among adults(Reference Wing and Hill4) and informs subsequent weight-loss interventions. One study examining weight loss among adolescents found that those who had lost weight over a year were more likely to be physically active than those who maintained or gained weight, but the study was unable to determine if the weight loss was intentional(Reference Boutelle, Hannan and Neumark-Sztainer5). A smaller study reported that overweight adolescents who had successfully lost weight were more likely to report healthier dietary behaviours and weight-control strategies than those who had not lost weight(Reference Boutelle, Libbey and Neumark-Sztainer6). However, neither of these studies examined the role of the family and home environments in successful weight loss. This is an area of great interest given the important influence families have on healthy adolescent development more generally(Reference Resnick, Bearman and Blum7).

The aim of the current study is to build on the growing body of research by describing the personal characteristics and behaviours of adolescents who have sustained weight loss in a large, nationally representative sample. The current study also examines the family environments of adolescents who have sustained weight loss to understand how families can support young people in successful weight control.

Methods

Data for the current study were collected as part of a representative survey of the health and well-being of New Zealand secondary-school students during 2007 (Youth'07)(8). The Youth'07 survey included a 622-item multimedia questionnaire administered on an Internet tablet, anthropometric measurements and identification of the small residential area of the participant's home address to determine small-area neighbourhood deprivation.

Students (approximate age 13 to 18 years) were randomly selected through a two-stage clustered sampling design. In total, 9107 students from 115 schools participated in the survey. The response rate for schools was 84 % and for students 74 %. Among the most common reasons for students not participating were being absent from school or being unavailable on the day of the survey(8).

School principals consented to the survey being conducted in the school on behalf of the Boards of Trustees. Students and their parents were provided with information sheets about the survey. Students consented themselves to participate in the study on the day of the survey. The University of Auckland Human Subjects Ethics Committee granted ethical approval for the study.

Measures

Sustained weight loss was measured by a series of branching questions assessing weight-control intentions and behaviours. First, students were asked if they had tried to lose weight in the past 12 months (yes/no). If they responded yes, they were asked about the amount of weight lost (none/less than 5 kg/5 kg or more). If students responded that they had lost any weight, they were then asked if they maintained their weight loss for at least 6 months (yes/no). Students who reported that they tried to lose weight, lost some weight and maintained it for at least 6 months were categorized as achieving ‘sustained weight loss’. Students who reported that they tried to lose weight, lost some weight but did not maintain the weight loss for at least 6 months were categorized as achieving ‘temporary or recent weight loss’. Students who reported that they had tried to lose weight but did not lose any weight were categorized as achieving ‘no weight loss’.

Weight-control behaviours were assessed only among students who had tried to lose weight in the past 12 months. Students were asked, ‘During the past year, have you done any of the following things to lose weight or to stop gaining weight? (You can choose as many as you need)’. The options included (yes/no): ‘I exercised’, ‘I ate less fatty foods’, ‘I counted calories’, ‘I ate fewer sweets and less sugar’, ‘I ate fewer carbohydrates’, ‘I ate a high-protein diet’, ‘I made myself vomit’, ‘I took diet pills or other pills’, ‘I smoked cigarettes’, ‘I fasted or did not eat for more than a day’ and ‘I skipped one or more meals a day’.

Teased by family about weight was assessed with the question ‘Have you ever been teased or made fun of by family members because of your weight?’ (yes/no). Mum/Dad encourages healthy eating was assessed with two items asking ‘How much does your mum (dad) or someone who acts as your mum (dad) encourage you to eat healthy food?’ (very much v. some, a little or not at all). Mum/Dad encourages physical activity was assessed with two items asking ‘How much does your mum (dad) or someone who acts as your mum (dad) encourage you to be physically active?’ (very much v. some, a little or not at all). Home availability of junk food and fruit were assessed with two questions asking ‘How often are the following foods available to eat at home: junk food; fruit?’ (usually v. sometimes or never).

Age, gender and ethnicity were determined by self-report. Ethnicity was assessed using the standard measures developed for the New Zealand census(9) where participants can select all of the ethnic groups that they identify with. Discrete ethnic populations were created using a prioritization method in the following order: Māori, Pacific, Asian, Other ethnicity, European.

Small-area deprivation was determined using the 2006 New Zealand Deprivation Index(Reference Salmond, Crampton and Atkinson10). The index measures eight dimensions of deprivation using 2006 census data based on small area geographical (meshblock) units. Index deciles were categorized into three groups reflecting low deprivation (1–3), middle levels of deprivation (4–7) and high deprivation (8–10).

Height was measured using a portable stadiometer (Seca model 214) to the nearest 0·1 cm. Weight was measured using digital scales (Health-o-Meter model 349KLX) to 0·1 kg. BMI (kg/m2) was calculated by dividing weight (in kilograms) by the square of height (in metres). Weight classification (underweight, normal weight, overweight, obese) was defined using the International Obesity Taskforce definitions for overweight, obesity and thinness (grade 1) for children and adolescents(Reference Cole, Bellizzi and Flegal11, Reference Cole, Flegal and Nicholls12).

Analysis

All analyses were conducted using the survey procedures in the SAS statistical software package version 9·2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) to account for the weighted and clustered design of the data. Frequencies and 95 % confidence intervals were generated to describe the weight-loss strategies and family characteristics among students who achieved sustained weight loss, temporary/recent weight loss or no weight loss. Separate logistic regression equations were generated to determine the independent effect of each of the weight-control behaviours and family characteristics on sustained weight loss, while controlling for age, sex, ethnicity and small-area deprivation. The temporary/recent weight loss and no weight loss categories were combined as the referent in the regression models. Differences were considered to be statistically significant at P < 0·05.

Post hoc analyses were conducted to determine if gender or amount of weight lost had a modifying effect on the relationships between sustained weight loss and dietary behaviours and family environments. These analyses were conducted by generating two new sets of regression models which included interaction terms (between the independent variable of interest and sex/amount of weight lost) and the covariates. Given the number of comparisons made, a higher level of significance was set for the post hoc analyses (P < 0·01).

Results

In total, 50·1 % (n 4358) students had attempted weight loss in the past year and were retained for analysis. Females (66 %), Maori (54 %) students and Pacific (60 %) students, students living in the most deprived areas (54 %), and overweight (70 %) and obese (84 %) students were the most likely to have attempted weight loss in the previous year. There were no differences in the prevalence of weight-loss attempts by age (data not shown).

Among students who attempted weight loss in the past year, 51 % achieved sustained weight loss, 34 % made a temporary/recent weight loss and 16 % had no weight loss (Table 1). A higher proportion of males (58 %) than females (46 %) achieved sustained weight loss; few other differences in demographic or personal characteristics were observed. While it appears that a high proportion of underweight students reported sustained weight loss, the actual number of underweight students is quite small and the confidence intervals for these estimates are wide.

Table 1 Participant characteristics by outcome of weight-loss attempts: secondary-school students, New Zealand, 2007

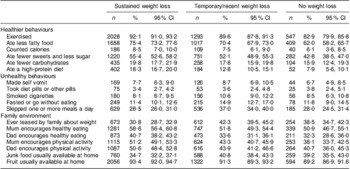

Students achieving sustained weight loss were more likely to report using healthier weight-loss strategies (e.g. exercising, eating less fatty food) than students with temporary/recent weight loss or no weight loss (Tables 2 and 3). There were few differences in the use of unhealthy weight-loss strategies. The prevalence of vomiting, using diet pills and smoking cigarettes for weight loss was similar among students with sustained weight loss and temporary/recent or no weight loss. However, students who reported sustained weight loss were less likely to fast (P = 0·02) or skip meals (P < 0·001) than students who reported temporary/recent or no weight loss. Students achieving sustained weight loss also reported more positive home and family environments than those who reported temporary/recent or no weight loss. Specifically, students with sustained weight loss were more likely to report their mum (P < 0·001) and dad (P < 0·001) encouraged healthy eating, their mum (<0·001) and dad (P < 0·001) encouraged physical activity and that they usually had fruit available to eat at home (P < 0·001) than students with temporary/recent or no weight loss. Furthermore, students reporting sustained weight loss were less likely to have been teased by their family about their weight (P < 0·001) and less likely to usually have junk food available to eat at home (P < 0·001). Given the gender differences in the prevalence of sustained weight loss, post hoc analyses were conducted to determine if the relationships between sustained weight loss and dietary behaviours and the home environment differed between males and females. Our analyses suggested that all of the relationships examined were similar for both males and females (data available on request).

Table 2 Weight-control behaviours and family environments by outcome of weight-loss attempts, unadjusted analyses: secondary-school students, New Zealand, 2007

Table 3 Weight-control behaviours and family environments by outcome of weight-loss attempts, controlling for age, sex, ethnicity and small-area deprivation: secondary-school students, New Zealand, 2007

*Temporary or recent weight loss and no weight loss categories combined as the referent.

Discussion

In New Zealand, approximately 50 % of young people attempting weight loss reported sustained weight loss. This finding is difficult to compare with other populations as the current study is the first national study of weight loss among adolescents intending to lose weight. In the only other national study of adolescent weight loss, Boutelle et al.(Reference Boutelle, Hannan and Neumark-Sztainer5) found that 22 % of young people reported losing weight over the previous year, but the study was not able to assess if the weight loss was intentional. Apart from gender, there were few differences in the demographic characteristics of students who report sustained weight loss in the current study. The study by Boutelle et al.(Reference Boutelle, Hannan and Neumark-Sztainer5) also suggested that weight loss was more common among males than females, but few other ethnic or socio-economic differences were significant. That more males than females reported sustained weight loss in the current study may reflect the different practices that males and females commonly use for weight control. Previous research suggests that males tend to adopt more moderate or healthy weight-control practices, while females engage in both health and unhealthy methods to control their weight(Reference Utter, Denny and Percival3, Reference Field, Haines and Rosner14).

In the current study, young people who reported a sustained weight loss were more likely to have reported using healthier weight-control strategies than those who did not and these findings are consistent with what has been published previously for adults and adolescents(Reference Wing and Hill4–Reference Boutelle, Libbey and Neumark-Sztainer6, Reference Field, Haines and Rosner14). In a large study of female adolescents, the combination of physical activity and healthy dietary changes resulted in the greatest subsequent weight loss compared with physical activity or dietary change alone(Reference Field, Haines and Rosner14). The current study found few differences in the use of unhealthier weight-loss strategies between adolescents who reported sustained weight loss and those who did not. This suggests that these unhealthier weight-loss strategies are ineffective and is in agreement with previous research that also found no differences in the use of unhealthy weight-loss behaviours (e.g. laxative use, vomiting after eating) between overweight young people who had lost weight compared with those who had not(Reference Boutelle, Libbey and Neumark-Sztainer6). However, the proportion of young people using some of the unhealthier weight-control behaviours in the current study was quite small and thus we may not have had enough power in these analyses to detect differences.

Our results describing the healthier and more positive home environments of students who have sustained weight loss are novel findings for population-based studies. Our findings are consistent with previous child weight-loss interventions that found that targeting the parents and/or family is more effective than just targeting the child(Reference Epstein, Valoski and Wing15–Reference Janicke, Sallinen and Perri17). This likely reflects that if adults within the home are engaged in improving eating and activity behaviours of their young people, they may prioritize creating more supportive home environments for healthy eating and physical activity.

The current study examines sustained weight loss among a nationally representative sample of young people who intend to lose weight. The large sample size, objective measures of body size and socio-economic indicators, and inclusion of family environment variables are notable strengths and make a contribution to the emerging literature on adolescent weight loss. The major limitation of the current study is the self-reported nature of the measure of sustained weight loss. However, Field et al.(Reference Field, Aneja and Rosner18) found that self-reported weight change was highly correlated with measured weights in a large cohort of adolescents. Second, our measure of sustained weight loss may include students for whom weight loss would not be indicated. That said, the prevalence of underweight in the national sample was less than 3 %(Reference Utter, Denny and Percival3) and only 6 % of underweight students reported that they made a weight-loss attempt in the past year (data not shown). While this group of young people may represent a unique clinical sub-sample, they are unlikely to affect the major findings of the current research. The categories of actual body weight (underweight, normal weight, etc.) are provided in the current study for descriptive purposes only. Third, our measure of sustained weight loss may not reflect a clinically meaningful loss. However, the American Academy of Pediatrics acknowledges that the primary goal of weight management in childhood is not necessarily weight loss, but may also include weight maintenance during growth(Reference Barlow19). For adolescents, particularly older adolescents or very overweight adolescents, more intensive efforts may be required to achieve good outcomes. We suspect that our study population included a high proportion of adolescents who have yet to reach their adult height and weight (most were aged 15 years or younger), suggesting that small, sustained weight losses may be significant. Lastly, findings from post hoc analyses suggest that the associations between sustained weight loss and the dietary behaviours and family environments were not modified by the amount of weight loss reported (data not shown).

Conclusions

Half of young people who attempted weight loss reported achieving sustained weight loss. Young people who successfully lost weight reported using healthier weight-control behaviours and having more supportive family environments than young people who did not achieve sustained weight loss. This suggests that families may have an important role in young people's weight control.

Acknowledgements

Source of funding: The Youth'07 survey was funded by the Health Research Council of New Zealand (grant 05/216), the Department of Labour, the Families Commission, the Accident Compensation Corporation of New Zealand, Sport and Recreation New Zealand, the Alcohol Advisory Council of New Zealand, and the Ministries of Youth Development, Justice and Health. Additional funding to support the preparation of this manuscript was provided by a grant from the Auckland Medical Research Foundation. Conflicts of interest: All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest. Authors’ contribution: J.U. conceived the study, conducted analyses and drafted the manuscript. S.D., R.D., S.A. and T.T. contributed intellectual input in interpreting findings and critical revisions of the manuscript. S.D., R.D. and S.A. also secured funding for the Youth'07 study.