Introduction

Onthophagus Latreille, 1802 (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae: Scarabaeinae: Onthophagini) is a hyperdiverse genus, comprising about 2200 described species (Rossini et al. Reference Rossini, Vaz-de-Mello and Zunino2018a, Reference Rossini, Vaz-de-Mello and Zunino2018b); it is part of the largest clade of Scarabaeinae dung beetles, the Onthophagini, with over 2500 species (Scholtz et al. Reference Scholtz, Davis and Kryger2009; Philips Reference Philips, Simmons and Tidsdill-Smith2011). This genus is widely distributed, exhibiting its highest diversity in the Afrotropical and Oriental regions. Scholtz et al. (Reference Scholtz, Davis and Kryger2009) consider that part of their evolutionary success resides in having a generally small size, their use of many food sources, as well as having relatively short life cycles and simple nests plus a rapid generation turnover with multiple breeding episodes.

The genus Onthophagus has also emerged as a promising model for undertaking studies in evolutionary developmental biology and ecological development. Specifically, the genus offers promising research avenues for integrating developmental genetics underpinning phenotypic diversity, especially through the analysis of horn expression and other secondary sexual traits (Moczek Reference Moczek, Simmons and Tidsdill-Smith2011). Onthophagus have also become an insect model for studying the evolution of parental care (Hunt and House Reference Hunt, House, Simmons and Tidsdill-Smith2011).

The genus Onthophagus has been the focus of detailed taxonomic group analyses for the Western Hemisphere. Among the recent general studies, we can cite an analysis of the O. hircus Billberg, 1815 species group and its O. oscullatii Guérin-Méneville, 1855 species complex (Rossini et al. Reference Rossini, Vaz-de-Mello and Zunino2018a, Reference Rossini, Vaz-de-Mello and Zunino2018b), as well as an analysis of the O. fuscus Boucomont, 1932 species complex (Joaqui et al. Reference Joaqui, Moctezuma, Sánchez-Huerta and Escobar2019).

The O. landolti Harold, 1880 species group was established by Zunino and Halffter (Reference Zunino and Halffter1997) and redefined by Zunino (Reference Zunino and Morón2003). Recently, Howden and Génier (Reference Howden and Génier2004) and Moctezuma et al. (Reference Moctezuma, Rossini, Zunino and Halffter2016) studied this group. Howden and Génier (Reference Howden and Génier2004) revised the O. lecontei Harold, 1871–O. subopacus Robinson, 1940 species complex, whereas, Moctezuma et al. (Reference Moctezuma, Rossini, Zunino and Halffter2016) established another species complex for O. mariozuninoi Delgado et al., 1993.

In this paper, we establish the O. anthracinus Harold, 1873 species complex, with description of O. etlaensis new species from Oaxaca, Mexico. In addition, Onthophagus mextexus Howden and Cartwright, 1970 is resurrected from previous synonymy and O. knulli Howden and Cartwright, 1963 is considered to be a junior synonym of O. durangoensis Balthasar, 1939.

Materials and methods

Specimens were studied from the collections of the Canadian Museum of Nature (CMNC) in Ottawa, Ontario, Canada; the Instituto de Ecología, Xalapa (IEXA), Xalapa, Mexico; the Universidad del Valle de Guatemala, Guatemala City, Guatemala; and the Museo Nacional, Santo Domingo de Heredia, Costa Rica. The holotype, allotype, and 177 paratypes of O. etlaensis are deposited in the Colección Entomológica (Entomology Collection), Instituto de Ecología, Xalapa, Mexico. Further paratypes are deposited in the following institutes: six paratypes in the Seção de Entomologia da Coleção Zoológica da Universidade Federal de Mato Grosso, Cuiabá, Brazil (CEMT); 17 paratypes in the Canadian Museum of Nature, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada; and six paratypes in the personal collection of Julián Blackaller, Tlalpan, Mexico (JB).

Body measurements were made to the nearest 0.1 mm using an ocular micrometer with a Zeiss Stemi DV4 stereoscope, Jena, Germany. Genital dissections and preparations were done following the techniques described by Zunino (Reference Zunino1978). Genital structures were stored in microvials with glycerin.

Photographs of O. anthracinus, O. durangoensis, and O. etlaensis were taken by Susana Guzmán-Gómez (Instituto de Biología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Mexico City, Mexico) using a Zeiss AXIO Zoom V16 microscope, a Zeiss AxioCam MRc5 camera, and the Zeiss efficient navigation multifocal technology programme (Zeiss, Jena, Germany). The photographs of O. alluvius Howden and Cartwright, 1963, O. knulli, and O. mextexus were taken by François Génier (CMNC) using a Leica Z16 system and Leica Application Suite software for image stacking (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany). Photographs of the aedeagi were taken by François Génier (CMNC) and Fernando Escobar-Hernández (IEXA). Serge Laplante (Canadian National Collection of Insects, Arachnids, and Nematodes, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada) took photographs of the holotypes of O. knulli and O. monticolus Howden and Cartwright, 1963. Jiří Hájek (Národní Muzeum, Prague, Czech Republic) took photographs of the syntypes of O. durangoensis Balthasar, 1939. Sara Rivera-Gasperín and Fernando Escobar-Hernández (IEXA) took photographs of the internal sac lamellae of O. anthracinus and O. etlaensis.

We use the phylogenetic species concept in its diagnosability version according to Zachos (Reference Zachos2016: 125), as proposed by Wheeler and Platnick (Reference Wheeler, Platnick, Wheeler and Meier2000: 58), where a species is defined as “the smallest aggregation of (sexual) populations or (asexual) lineages diagnosable by a unique combination of character states”.

Onthophagus etlaensis Kohlmann, Escobar-Hernández, and Arriaga-Jiménez, new species

http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:act:83069DD6-F365-4A47-B964-52DA349CE5B8.

Figures 1, 2, 5–6, 13, 19, 22.

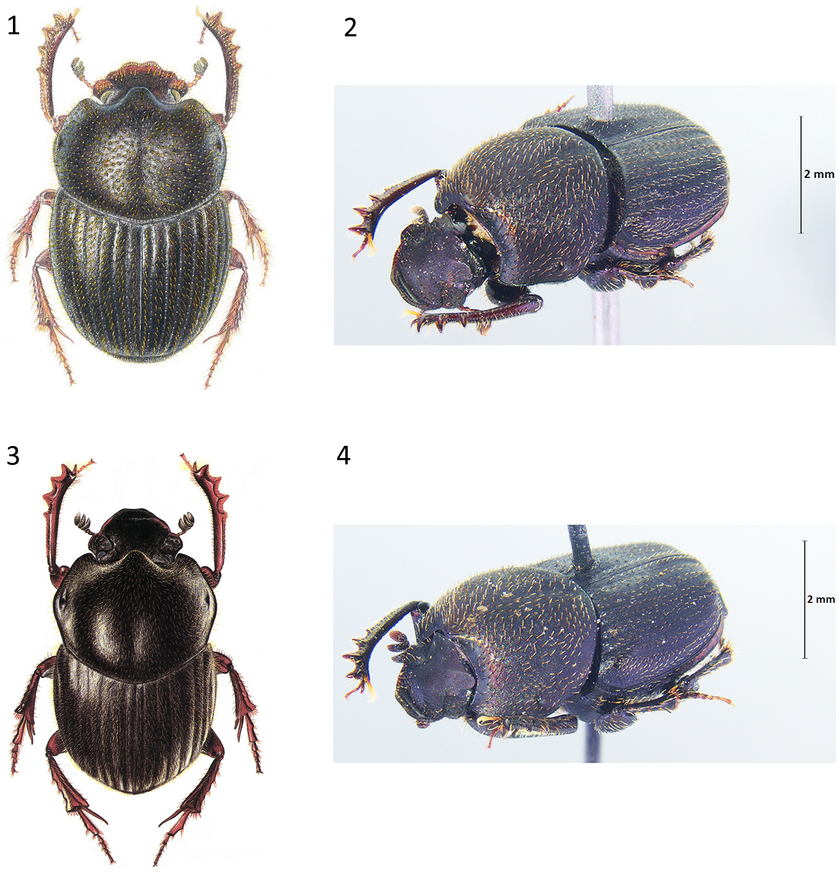

Figs. 1–4. Onthophagus etlaensis and O. anthracinus habitus. 1, Onthophagus etlaensis dorsal view; 2, O. etlaensis anterolateral view; 3, O. anthracinus dorsal view; 4, O. anthracinus anterolateral view.

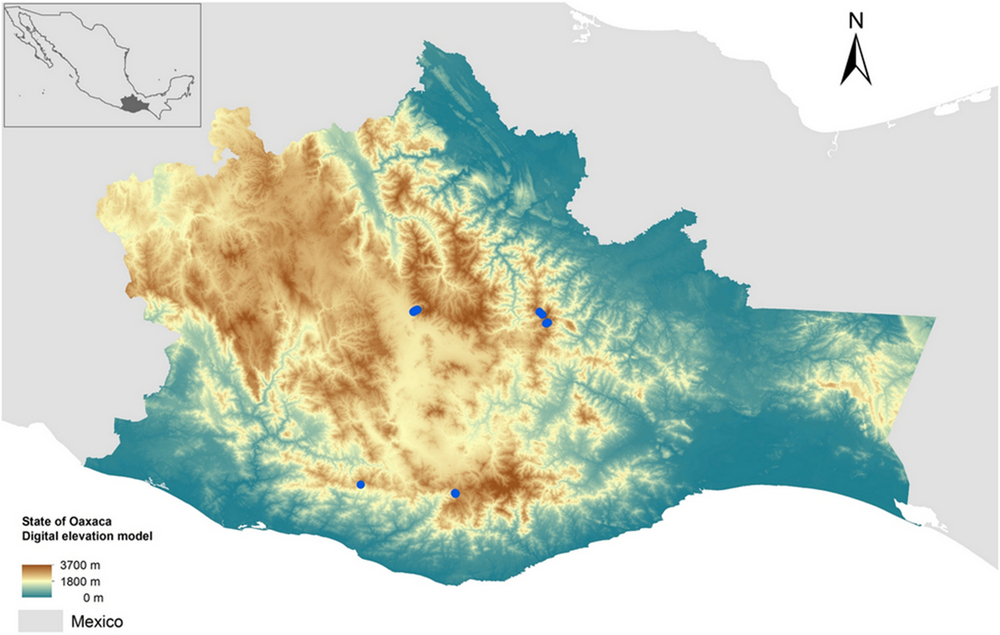

Fig. 5. Map of the known distribution of Onthophagus etlaensis (blue dots). Orography of Oaxaca is shown, based on the digital elevation model downloaded from www.inegi.org.mx. Grey areas show the extent of Mexico, see map in the upper left for the location of the state of Oaxaca within Mexico.

Fig. 6. Typical habitat of Onthophagus etlaensis: San Mateo Río Hondo, Sierra Sur, Pinus-Quercus forest.

Type material. Holotype male pinned. Original label: “Reserva Comunitaria San Pablo, Etla, Oaxaca. 27-IX-16, coprotrampa, x- 96.718644° O, y- 17.17699° N, bosque de encino, 2443 m, Arriaga A. & Arenas A. Col.” and “HOLOTYPE/Onthophagus etlaensis Kohlmann, Escobar-Hernández, Arriaga-Jiménez” (red printed label) deposited in the Colección Entomológica (Entomology Collection), Instituto de Ecología, Xalapa, Mexico. Allotype female: “México. Reserva Comunitaria San Pablo Etla, Oaxaca. 23-VI-17, coprotrampa, x- 96° 43’ 50.34” W, y- 17° 10’ 15.64” N, bosque de encino, 2219 m, Arriaga J.A. Col.” and “ALLOTYPE/Onthophagus etlaensis Kohlmann, Escobar-Hernández, Arriaga-Jiménez” (light blue printed label).

Paratypes (76 males, 130 females): “México. Reserva Comunitaria San Pablo Etla, Oaxaca. 12-VII-17, coprotrampa, x- 96° 43’ 47.02” W, y- 17° 10’ 16.19” N, bosque de encino, 2193 m, Arriaga A. y Arenas A. Col.” (one male, three females) (IEXA); “México. Reserva Comunitaria San Pablo Etla, Oaxaca. 14-VII-17, coprotrampa, bosque de encino, 2193 m, Arriaga A. y Arenas A. Col.” (two females) (IEXA); “México. Reserva Comunitaria San Pablo Etla, Oaxaca. 20-IX-16, coprotrampa, x- -96.685011°, y- 17.167224°, bosque de pino, 2983 m, Arriaga A. y Arenas A. Col.” (two males, 11 females) (IEXA); “México. Reserva Comunitaria San Pablo Etla, Oaxaca. 20-IX-16, coprotrampa, x- -96.733014°, y- 17.170797°, bosque de encino, 2133 m, Arriaga A. y Arenas A. Col.” (nine males, 12 females) (IEXA); “México. Reserva Comunitaria San Pablo Etla, Oaxaca. 23-VI-17, coprotrampa, x- 96° 43’ 51” W, y- 17° 10’ 14” N, bosque de encino, 2205 m, Arriaga J.A. Col.” (three females) (IEXA); “México. Reserva Comunitaria San Pablo Etla, Oaxaca. 14-VII-17, coprotrampa, x- 96° 43’ 47.02” W, y- 17° 10’ 16.19” N, bosque de encino, 2193 m, Arriaga A. y Arenas A. Col.” (two females) (IEXA); “México. Reserva Comunitaria San Pablo Etla, Oaxaca. 20-IX-16, coprotrampa, x- -96.685011°, y- 17.167224°, bosque de pino, 2983 m, Arriaga A. y Arenas A. Col.” (five females) (IEXA); “México. Reserva Comunitaria San Pablo Etla, Oaxaca. 10-VII-17, coprotrampa, x- 96° 43’ 21” W, y- 17° 10’ 29” N, bosque de encino, 2343 m Arriaga A. y Arenas A. Col.” (one female) (IEXA); “México. Reserva Comunitaria San Pablo Etla, Oaxaca. 12-VII-17, coprotrampa, x- 96° 43’ 21” W, y- 17° 10’ 29” N, bosque de encino, 2343 m Arriaga A. y Arenas A. Col.” (one female) (IEXA); “México. Reserva Comunitaria San Pablo Etla, Oaxaca. 23-IX-16, coprotrampa, x- -96.723379°, y- 17.176195°, bosque de encino, 2302 m, Arriaga A. y Arenas A. Col.” (two females) (IEXA); “México. Reserva Comunitaria San Pablo Etla, Oaxaca. x- -96.723379°, y- 17.174158°, bosque de encino, 2271 m, Arriaga A. y Arenas A. Col.” (four males, two females) (IEXA); “México. Reserva Comunitaria San Pablo Etla, Oaxaca. x- -96.725892°, y- 17.173568°, bosque de encino, 2256 m, Arriaga A. y Arenas A. Col.” (three males, five females) (IEXA); “México. San José del Pacífico, Miahuatlán, Oaxaca. 31-VIII-17, coprotrampa, x- -96.50903°, y- 16.16460°, bosque pino/encino, 2325 m, Arriaga J.A. Col.” (one male, two females) (IEXA); “México. San José del Pacífico, Miahuatlán, Oaxaca. x- -96.51173°, y- 16.16972°, bosque mesófilo, 2316 m, Arriaga J.A. Col.” (four males, nine females) (IEXA); “México. Reserva Comunitaria San Pablo Etla, Oaxaca. 20-IX-16, coprotrampa, x- -96.732843°, y- 17.17034°, bosque de encino, 2138 m, Arriaga A. y Arenas A. Col.” (two males, six females) (IEXA); “México. Reserva Comunitaria San Pablo Etla, Oaxaca. 12-VII-17, coprotrampa, x- 96° 43’ 51.37” W, y- 17° 10’ 12.32” N, bosque de encino, 2186 m, Arriaga A. y Arenas A. Col.” (two males, two females) (IEXA). “México. Zempoaltépetl, Santa María Tlahuitoltepec, Oaxaca. 29-V-17, C.D. exc. vaca, x- 96° 0’ 43.28” W, y- 17° 6’5.5” N, pastizal, 2411 m, Arriaga J. A. Col.” (one male, three females); (IEXA) “México. Zempoaltépetl, Santa María Tlahuitoltepec, Oaxaca. 28-V-17, coprotrampa, x- 96° 1’ 57.20” W, y- 17° 8’59.41” N, acahual, 2623 m, Arriaga J. A. Col.” (one male) (IEXA); “México. Zempoaltépetl, Santa María Tlahuitoltepec, Oaxaca. 30-V-17, coprotrampa x- 96° 1'55.23"W, y- 17° 8'59.28"N acahual / maíz, 2626 m. Arriaga- Jiménez, A. Col.” (one male) (IEXA); “México. Zempoaltépetl, Santa María Tlahuitoltepec, Oaxaca. 29-V-17, coprotrampa x- 96°0'43.28'' W, y- 17°6'5.5'' N, pastizal, 2411 m, Arriaga- Jiménez, A. Col.” (three males, two females) (IEXA); “México. Zempoaltépetl, Santa María Yacochi, Oaxaca. 30-VII-17, coprotrampa x- 96° 2’ 52.27” W, y- 17° 9’52.46” N, acahual, 2406 m, Arriaga J. A. Col.” (one male, one female) (IEXA); “México. La Mesita, San Pablo Etla, Oaxaca. 23-IX-16, coprotrampa, x- -96.736763°, y- 17.16688°, bosque de encino, 1995 m, Arriaga A. y Arenas A. Col.” (two males, one female) (IEXA); “México. La Mesita, San Pablo Etla, Oaxaca. x- -96.72376°, y- 17.17591°, bosque de encino, 2309 m, Arriaga A. y Arenas A. Col.” (one male, one female) (IEXA); “México. La Mesita, San Pablo Etla, Oaxaca. x- -96.725454°, y- 17.17433°, bosque de encino, 2276 m, Arriaga A. y Arenas A. Col.” (three males, one female) (IEXA); “México. La Mesita, San Pablo Etla, Oaxaca. 20-IX-16, coprotrampa, x- -96.732348°, y- 17.170968°, bosque de encino, 2155 m, Arriaga J. A. Col.” (two males, three females) (IEXA); “México. La Mesita, San Pablo Etla, Oaxaca. 27-IX-16, coprotrampa, x- -96.718872°, y- 17.177351°, bosque de encino, 2410 m, Arriaga J. A. Col.” (one male, one female) (IEXA); “México. La Mesita, San Pablo Etla, Oaxaca. 20-IX-16, coprotrampa, x- -96.732386°, y- 17.170454°, bosque de encino, 2151 m, Arriaga J. A. Col.” (five males, four females) (IEXA); “México. La Mesita, San Pablo Etla, Oaxaca. 17-VI-17, coprotrampa, x- 96°43’19’’ W, y- 17° 10’ 31.31’’ N, bosque de encino, 2366 m, Arriaga J. A. Col.” (one male, one female) (IEXA); “México. La Mesita, San Pablo Etla, Oaxaca. 12-VII-17, coprotrampa, x- 96°43’52.5’’ O, y- 17° 10’ 13.’’ N, bosque de encino, 2195 m, Arriaga A. & Arenas A. Col.” (one male, two females) (IEXA); “México. La Mesita, San Pablo Etla, Oaxaca. 23-IX-16, coprotrampa, x- -96.72534°, y- 17.173835° N, bosque de encino, 2256 m, Arriaga A. & Arenas A. Col.” (two females) (IEXA); “México. La Mesita, San Pablo Etla, Oaxaca. x- -96.723151°, y- 17.175643°, bosque de encino, 2323 m, Arriaga A. & Arenas A. Col.” (three females) (IEXA); “México. La Mesita, San Pablo Etla, Oaxaca. 10-VII-17, coprotrampa, x- 96°43’23.31’’ W, y- 17° 10’ 30.07’’ N, bosque de encino, 2349 m, Arriaga J. A. Col.” (five males) (IEXA); 20-VIII-17, coprotrampa, “México. La Mesita, San Pablo Etla, Oaxaca. x- 96°44’25’’ W, y- 17° 09’ 50’’ N, bosque de encino, 1935 m, Arriaga J. A. Col.” (five males, 16 females) (IEXA); “México. La Mesita, San Pablo Etla, Oaxaca. 23-IX-16, coprotrampa, x- -96.723551°, y- 17.175472°, bosque de encino, 2325 m, Arriaga A. & Arenas A. Col.” (one male, four females) (IEXA); “México. Zempoaltépetl, Santa María Tlahuitoltepec, Oaxaca. 30-V-17, coprotrampa x- 96° 1’ 55.23” W, y- 17° 8’ 59.28” N, acahual, 2626 m, Arriaga J. A. Col.” (one male) (IEXA); “México. Zempoaltépetl, Santa María Tlahuitoltepec, Oaxaca. 27-VII-17, coprotrampa x- 96° 4’ 31” W, y- 17°6’ 20.40” N, bosque de galería, 2583 m, Arriaga J. A. Col.” (one female) (IEXA). “México. Zempoaltépetl, Santa María Yacochi, Oaxaca. 29-VII-17, coprotrampa x- 96° 0’ 35.36” W, y- 17° 06’ 5.43” N, acahual, 2471 m, Arriaga J. A. Col.” (one female) (IEXA); “México. Zempoaltépetl, Santa Maróa Tlahuitoltepec, Oaxaca. 27-V-17, coprotrampa x- 96° 0’ 33” W, y- 17° 06’ 08” N, lindero ilites, 2445 m, Arriaga J. A. Col.” (one male) (IEXA); “México. Reserva Comunitaria San Pablo Etla, Oaxaca. 27-IX-16, coprotrampa, x- -96.718644°, y- 17.17699°, bosque de encino, 2443 m, Arriaga A. & Arenas A. Col.” (two females) (IEXA); “México. Reserva Comunitaria San Pablo Etla, Oaxaca. 23-IX-16, coprotrampa, x- -96.72534°, y- 17.17699°, bosque de encino, 2443 m, Arriaga A. & Arenas A. Col.” (one male) (IEXA); “México. Reserva Comunitaria San Pablo Etla, Oaxaca. x- -96.723551°, y- 17.175472°, bosque de encino, 2326 m, Arriaga J. A. Col.” (one female) (IEXA); “México. Reserva Comunitaria San Pablo Etla, Oaxaca. x- -96.725987°, y- 17.174158°, bosque de encino, 2271 m, Arriaga A. & Arenas A. Col.” (two males) (IEXA); “México. Reserva Comunitaria San Pablo Etla, Oaxaca. 20-IX-16, coprotrampa, x- -96.732843°, y- 17.17034°, bosque de encino, 2138 m, Arriaga A. & Arenas A. Col.” (one female) (IEXA); “México. Reserva Comunitaria San Pablo Etla, Oaxaca. x- -96.733014° O, y- 17.170797°, bosque de encino, 2133 m (one male) (IEXA); 14-VII-17, coprotrampa, x- 96° 44’ 53.55’’ O, y- 17° 9’ 53.55’’ N, bosque de encino, 1954 m, Arriaga A. & Arenas A. Col.” (one female) (IEXA); “México. Reserva Comunitaria San Pablo Etla, Oaxaca. x- 96°44’20’’ O, y- 17° 9’ 54’’ N, bosque de encino, 1974 m, Arriaga A. & Arenas A. Col.” (one female) (IEXA); “México. Reserva Comunitaria San Pablo Etla, Oaxaca. 23-VI-17, coprotrampa, x- 96° 43’ 50’’ W, y- 17° 10’ 15’’ N, bosque de encino, 2219 m, Arriaga A. & Arenas A. Col.” (one female) (IEXA); “México. Reserva Comunitaria San Pablo Etla, Oaxaca. 20-VIII-17, coprotrampa, x- 96° 44’ 25” W, y- 17° 09’ 50” N, bosque de encino, 1935 m, Arriaga J.A. Col.” (four males, six females) (IEXA); “México. Reserva Comunitaria San Pablo Etla, Oaxaca. 27-IX-16, coprotrampa, x- 96° 71’ 86.44” W, y- 17° 17’ 07” N, bosque de encino, 2443 m, Arriaga, A. & Arenas, A., Col.” (two males) (IEXA); “México. Reserva Comunitaria San Pablo Etla, Oaxaca. x- 96° 72’ 03” W, y- 17° 17’ 05” N, 2309 m, Arriaga, A. & Arenas, A., Col.” (one male) (IEXA); “México. Reserva Comunitaria San Pablo Etla, Oaxaca. x- 96° 71’ 86.14” W, y- 17° 17’ 07” N, 2443 m, Arriaga, A. & Arenas, A., Col.” (one male) (IEXA); “México. Reserva Comunitaria San Pablo Etla, Oaxaca. 23-VI-17, x- 96° 43’ 50.34” W, y- 17° 10’ 06.36” N, 2435 m, Arriaga, J.A., Col.” (one female) (IEXA); “México. Reserva Comunitaria San Pablo Etla, Oaxaca. x- 96° 43’ 07” W, y- 17° 10’ 06.36” N, Arriaga, J.A., Col.” (one female) (IEXA); “México. Reserva Comunitaria San Pablo Etla, Oaxaca. x- 96° 43’ 50.34” W, y- 17° 10’ 15” N, Arriaga, J.A., Col.” (one female) (IEXA); “México. Reserva Comunitaria San Pablo Etla, Oaxaca. 10-VII-17, x- 96° 43’ 22” W, y- 17° 10’ 29” N, 2343 m, Arriaga, J.A., Col.” (one female) (IEXA); “México. San José del Pacífico, Miahuatlán, Oaxaca, 31-VIII-17, coprotrampa, x- -96.51173°, y- 16.16972°, bosque mesófilo, 2316 m, Arriaga, J.A., col.” (two males, one female) (IEXA); “México, San José del Pacífico, Miahuatlán, Oaxaca. 31-VIII-17, coprotrampa. x- -96.51173, y- 16.16972°, bosque mesófilo, 2316 m. Arriaga J.A. Col.” (two females) (JB); “México. Santa María Tlahuitoltepec, Oaxaca, 29-V-17, C.D. exc. vaca. x- 96°0’43.28’’W, y- 17’6’5.55’’N, pastizal, 2411 m. Arriaga J.A. col.” (two males) (JB); “México, Reserva Comunitaria San Pablo Etla, Oaxaca. 23-IX-16, coprotrampa x- -96.725987°, y- 17.174158°, bosque de encino, 2271 m. Arriaga A. & Arenas A. col.” (two males) (JB); “México, San José del Pacífico, Miahuatlán, Oaxaca. 31-VIII-17, coprotrampa. x- -96.51173°, y- 16.16972°, bosque mesófilo, 2316 m. Arriaga J.A. Col.” (two females) (CEMT); “México, Reserva Comunitaria San Pablo Etla, Oaxaca. 20-IX-16, coprotrampa. x- -96.723551°, y- 17.175472°, bosque de encino, 2325 m. Arriaga A. y Arenas A. Col.” (two females) (CEMT); “México, Reserva Comunitaria San Pablo Etla, Oaxaca. 20-IX-16, coprotrampa. x- -96.732386°, y- 17.170454°, bosque de encino, 2151 m. Arriaga A. y Arenas A. Col.” (two males) (CEMT); “México. Oaxaca. 20 miles South Juchatengo, 6000 27-30.v.71 S. Peck” (one male, two females) (CMNC); “México. Oaxaca. 20 miles South Juchatengo, 6000’, 28-30.v.71 S. Peck” (two males) (CMNC); “México. Oaxaca. 20 miles South Juchatengo 6000’, Rt.131,V.27-30, 1971 H.F. Howden” (two males, four females) (CMNC); “México, San José del Pacífico, Miahuatlán, Oaxaca. 31-VIII-17, coprotrampa. x- -96.51173 W, y- 16.16972°N, bosque mesófilo, 2316 m. Arriaga J.A. Col.” (two females) (CMNC); “México, Reserva Comunitaria San Pablo Etla, Oaxaca. 23-IX-16, coprotrampa. x- -96.723551 W, y- 17.175472°N, bosque de encino, 2325 m. Arriaga A. y Arenas A. Col.” (one male, one female) (CMNC); “México, Reserva Comunitaria San Pablo Etla, Oaxaca. 20-IX-16, coprotrampa. x- -96.732386 W, y- 17.170454°N, bosque de encino, 2151 m. Arriaga A. y Arenas A. Col.” (one male, one female) (CMNC).

Type locality. La Mesita, San Pablo Etla (17°9′50.68″N, 96°44′25.92″W, 1935 m), Oaxaca, Mexico.

Diagnosis. Pygidium almost flat; very shallowly, indistinctly punctate; alutaceous basally; apex slightly to moderately shiny. Large pronotal punctures (75 μm) separated about one diameter with distinct margins, not umbilicate, with a shiny ring and small shallow secondary nonsetate punctures sparsely interspersed. Pronotum crossed longitudinally and in the middle by a sulcus in major males, surrounding pronotal area convex.

Description. Holotype. Major male (Figs. 1–2). Length: 6.1 mm. Humeral width: 3.4 mm. Weakly shiny, opaque black. Clypeal margin sharply reflexed anteriorly, feebly so laterally; anterior edge faintly emarginate. Clypeal disc with few coarse punctures distributed across width. Frons with scattered shallow punctures. Clypeal disc and frons almost flat and lacking both clypeal and frontal carinae, the latter being poorly developed behind the eyes; surface between punctures finely alutaceous. Genal margin noticeably arcuate laterally, anteriorly forming a distinct, obtuse indentation with the clypeal margin; gena sharply and obtusely angulate posteriorly opposite the pronotal angles; genal surface slightly concave and with scattered, shallow punctures. Small eyes, five facets wide and emarginate, separated by about 16 eye widths. Occiput with scattered shallow punctures.

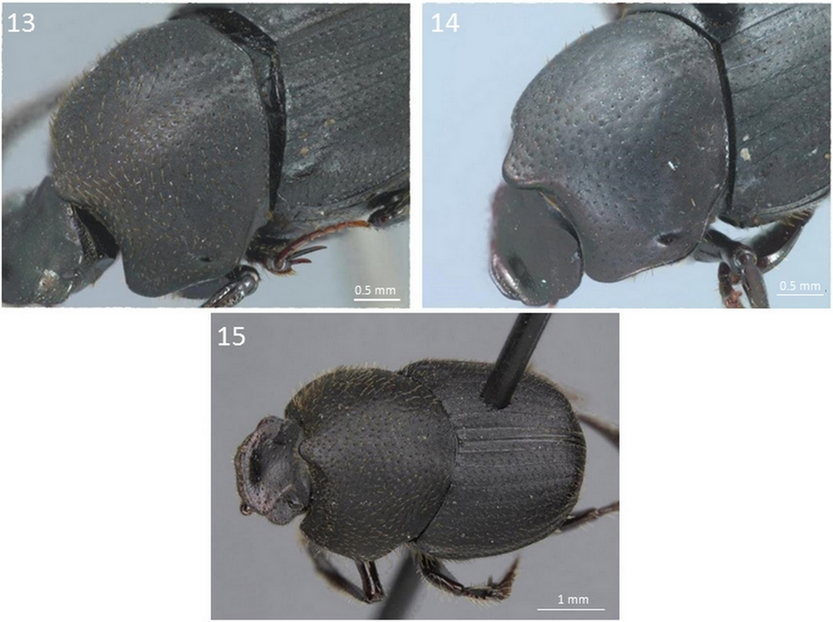

Pronotum (Fig. 13) moderately convex and margined anteriorly and laterally, pronotal protuberance conical broad and evenly arched, weakly projecting over the posterior portion of the head. Pronotal surface distinctly alutaceous and with two sizes of punctures: larger punctures annular with margins sharply defined, centrally with an erect reddish-yellow seta, the large punctures usually separated by approximately one diameter; small secondary punctures half the diameter of large punctures and not as numerous, scattered among large punctures, umbilicate in shape and lacking setae. Elytral striae with feebly shiny and vaguely punctate; intervals opaquely alutaceous with irregular double rows of small shiny tubercles; the base of each tubercle with a fine, reddish-yellow seta. Pygidium slightly longer than broad; opaquely alutaceous, slightly to moderately shiny apex, only slightly convex; covered sparsely with pale yellow setae, interspersed with small shiny punctures. Ventral surfaces, including antennae, black to blackish brown. Metaventrite surface coarsely punctate, more so laterally where the surface between punctures is finely alutaceous; base of metaventrite with large, coarse punctures, each bearing pale yellow setae. Ventrites, except for the first, with a row of setigerous punctures across their basal margin; last segment narrowed medially. Aedeagus like in Figure 19. Lamella copulatrix like in Figure 22. Prothoracic legs greatly elongate, the apices of the profemora extending slightly beyond the pronotal margin; protibiae long, slender, and recurved, with a pronounced apical conical projection and a long yellow pencil of setae protruding above the apical spine; all femora with scattered, coarse punctures, each puncture bears a pale yellow seta.

Variation. Length: 4.5–6.7 mm. Width: 2.5–3.5 mm. The colour of the lateral side and apical border of the elytra can vary from black to reddish brown.

Male pronotal protuberance can vary from evenly rounded to slightly notched in the middle. Male minors with pronotum less convex, protibiae with apical projection shorter, profemur barely extending to the lateral pronotal margin.

Females differ with clypeus slightly reflexed anteriorly, broadly, somewhat angularly emarginate; clypeal disc coarsely, rugousely punctate, punctures often with brownish-yellow setae; clypeal carina distinct (sometimes absent) but only slightly and rather evenly elevated above clypeal-frontal surface. Frons behind carina with a few distinct coarse punctures; frontal carina low but distinct, generally of uniform height; gena scarcely flared, only very obtusely angulate near pronotal angles and with coarse punctures. Area between female clypeal and frontal carina can vary from slightly to heavily and coarsely punctate. Pronotum less convex, pronotal protuberance indicated by a rounded swelling. Pygidium approximately as broad as long. Prothoracic legs stubby and shorter and the apex of the profemur barely reaches the lateral pronotal margin; protibia proportionately shortened; apical projection and pencil of setae lacking; apical spine as long as the three basal tarsomeres. Last ventrite not emarginate, approximately the same width throughout.

Etymology. Etla + ensis. Etla being a Nahuatl word, meaning: “Place where beans are abundant”. Also, this is the name of the locality, San Pablo Etla. The order of authorship for this new species reflects the amount of work contributed to the description.

Distribution and ecology. This species occurs in Oaxaca, Mexico (Fig. 5) at Reserva Comunitaria San Pablo Etla (Sierra Norte), 1900–3000 m; San José del Pacífico, San Mateo Río Hondo and south of Juchatengo (Sierra Sur), 1800–2500 m; Sierra Mixe at Zempoaltépetl, Santa María Tlahuitoltepec, and Santa María Yacochi, from 2400–2600 m. It has been collected in acahual (abandoned agricultural fields undergoing regeneration), grassland, cloud forest, Quercus Linnaeus (Fagaceae) forests, and Pinus-Quercus forest (Pinus Linnaeus, Pinaceae) and seems to be more abundant in Quercus forests. Specimens have been collected using dung-baited and carrion-baited pitfall traps, by hand, and in cattle (Bos taurus Linnaeus, 1758; Artiodactyla: Bovidae) and horse (Equus caballus Linnaeus, 1758; Perissodactyla: Equidae) manure.

Taxonomic placement. Onthophagus etlaensis belongs to the O. anthracinus species complex, part of the O. landolti species group. This species has many similarities to O. anthracinus. Onthophagus etlaensis has larger pronotal punctures (75 μm), separated by at least one diameter, pronotum traverse along its middle longitudinally by an evident sulcus in major males and the pronotal area around it convex; whereas, O. anthracinus has smaller pronotal punctures (50 μm) separated by 1–2 diameters, pronotal midline well marked in major males and the pronotal area around it flattened and forming a rhombus. The pygidium of O. etlaensis is opaquely alutaceous and is slightly to moderately shiny, much less so than in O. alluvius or O. durangoensis.

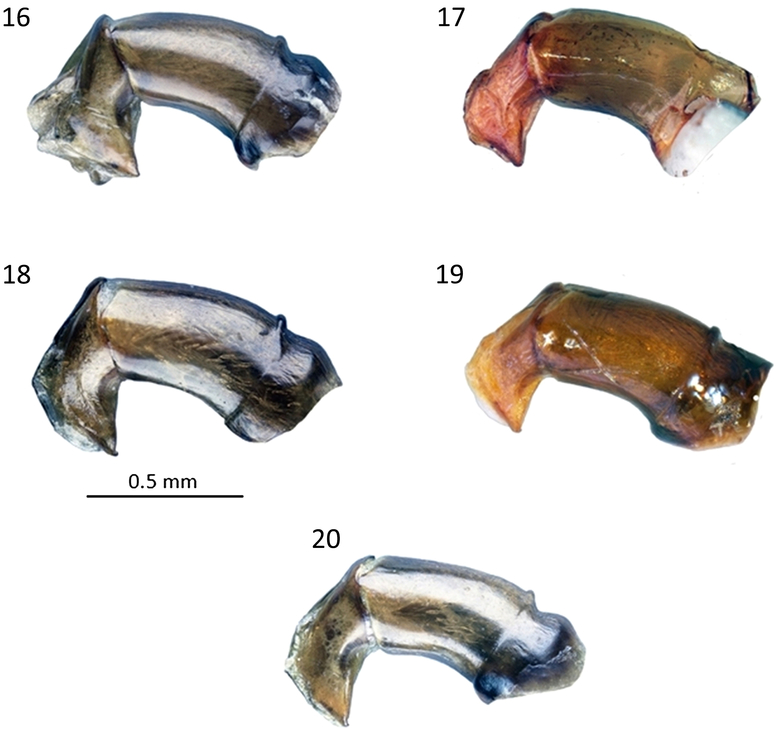

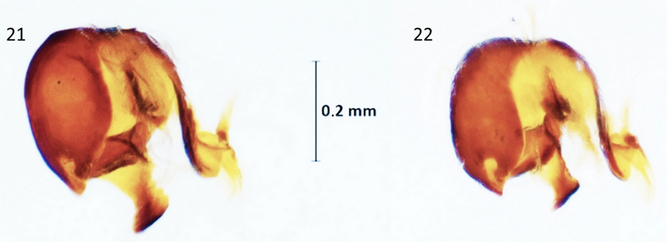

The aedeagus has been studied for this species complex (Figs. 16–20). All species north of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, including O. etlaensis, have an evident ring near the base of the aedeagus. On the contrary, O. anthracinus has a poorly developed and indistinct ring at the phallobase (Fig. 17). There are also fine differences in the structure of the parameres separating O. etlaensis from O. anthracinus; the first species has a straight frontal margin of the parameres as seen in lateral view, whereas the second species has a curved margin (Figs. 17, 19); the first species has a slender apex of the parameres as seen in the lateral view, whereas the second species has a much broader apex (Fig. 1). The lamella copulatrix of the internal sac (Figs. 21–22) is very similar in both species. These characteristics hold true for the populations examined from O. anthracinus originating from Chiapas (Mexico), Guatemala, and Costa Rica. As Howden and Cartwright (Reference Howden and Cartwright1963) observed, the type of punctures is one of the main characters for separating the different species. The Oaxacan specimens are constant in having large punctures (75 μm), whereas the specimens studied from Chiapas to Costa Rica have consistently smaller (50 μm) punctures.

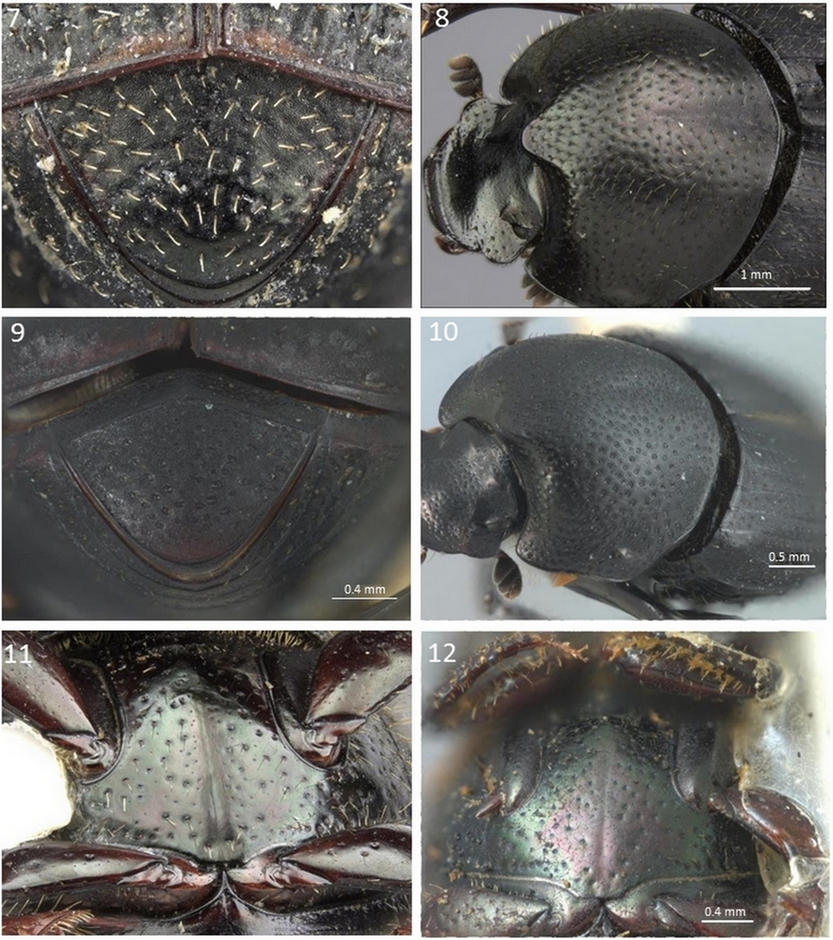

Figs 7–12. Species in the Onthophagus anthracinus species complex. 7, Pygidium of male Onthophagus alluvius; 8, pronotum of a male Onthophagus alluvius; 9, pygidium of male Onthophagus mextexus; 10, pronotum of a male of Onthophagus mextexus; 11, metasternal midline of a male Onthophagus alluvius; 12, metasternal midline of a male Onthophagus durangoensis.

Figs 13–15. Species in the Onthophagus anthracinus species complex. 13, Male pronotum of Onthophagus etlaensis; 14, male pronotum of Onthophagus anthracinus; 15, dorsal view of a male Onthophagus durangoensis.

Figs 16–20. Aedeagi of the Onthophagus anthracinus species complex. 16, Onthopagus alluvius; 17, O. anthracinus; 18, O. durangoensis; 19, O. etlaensis; 20, O. mextexus.

Figs 21–22. Lamella copulatrix and accesory lamellae. 21, Onthophagus anthracinus; 22, O. etlaensis.

It seems likely that Bates (Reference Bates1887: 77) in his redescription of O. anthracinus included specimens of O. etlaensis, as he indicated Oaxaca and Juquila as distribution localities.

Habitat affinities. Onthophagus etlaensis occupies similar ecological niches to O. anthracinus: Quercus, Pinus-Quercus, and Pinus forests in mountainous regions (Fig. 6).

Taxonomic considerations, notes, and new localities

Onthophagus alluvius Howden and Cartwright, 1963

Onthophagus alluvius (Figs. 7–8, 11, 16) is a well-established and much studied species. Elias et al. (Reference Elias, van Devender and De Baca1995) found this species in fossil packrat middens in the Bolsón de Mapimí, in the Chihuahuan Desert (Mexico), for a Late Glacial and Holocene paleoenvironmental reconstruction study. It was found to be present in the 3.0–3.5 thousand of years before present chronosequence at Puerto de Ventanillas, Coahuila (Mexico), where this species has not been recorded through present-day collecting. Another interesting mention of O. alluvius is by Cave (Reference Cave2005) who cites its presence in dog dung in Austin, Texas, United States of America.

This species was formerly known from Texas in the United States of America and from Nuevo León, Coahuila (see comment above), Tamaulipas, Querétaro, San Luis Potosí, and Hidalgo in Mexico. It is here recorded for the first time for Oaxaca, Mexico: Santiago Chazumba, San Sebastián de la Frontera, 8.vii.1999, GPS-52 (two females); San Juan Bautista Cuicatlán, Santiago Dominguillo, 14–16.vii.1999, 1320 m, selva intacta, human dung, A. Díaz (two females); Carretera Oaxaca-Cuicatlán a 50 km de Oaxaca, 14.vii.1999, dead cow, Alfonso Díaz (one female); Yanhuitlán, Oaxaca, 4.vi.1967, G. Halffter, V. Halffter, and P. Reyes (one male). All specimens deposited in the Instituto de Ecología, Xalapa collection.

Onthophagus anthracinus Harold, 1873

Howden and Cartwright (Reference Howden and Cartwright1963: 65) found the name Onthophagus anthracinus Harold, 1873 to be preoccupied by Onthophagus anthracinus Faldermann, 1835, which had been described from Transcaucasia in the Russian Empire. Kolenati (Reference Kolenati1846: 12) later established O. anthracinus Faldermann, 1835 to be a synonym of O. histeroides Ménétriés, 1832 (which was later transferred to the genus Caccobius Thomson, 1859). Consequently, the name Onthophagus anthracinus Harold, 1873 must be considered as a primary junior homonym of O. anthracinus Faldermann, 1835.

The International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature (1999) (Article 23.9.5) states that “When an author discovers that a species-group name in use is a junior primary homonym (Article 53.3) of another species group name also in use, but the names apply to taxa not considered congeneric after 1899, the author must not automatically replace the junior homonym; the case should be referred to the Commission for a ruling under the plenary power and meanwhile prevailing usage of both names is to be maintained [Art. 82].” This Article also indicates that the senior homonym should be in use, which is not the case with Faldermann’s name. O. anthracinus Harold, 1873 is a junior primary homonym that is currently in use and has not been considered congeneric with its senior homonym after 1899. So, although Faldermann’s name is not in use, one can interpret the spirit of the Article as to preserve the usage of junior primary homonyms that have been in use, by not being considered congeneric as its senior homonym for a long time. One can consider that this does not violate the principle that no two taxa should share the same name; therefore, we do here maintain the use of O. anthracinus Harold as a valid name. We have submitted a case to the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature as directed in Article 23.9.5 for the conservation of the specific name Onthophagus anthracinus Harold, 1873 and it is presently under review as case number 3807.

Onthophagus anthracinus (Figs. 3–4, 14, 17, 21) is known to occur from Chiapas, Mexico to Chiriquí, Panama. We cite here localities that were studied for the present analysis. Mexico, Chiapas: 5 km W San Cristóbal de las Casas, 8000’, 13–16.viii.1969, pine-oak forest, S.J. Peck (one male, eight females); 3 miles NW San Cristóbal de las Casas, 29.v.1969, H.F. Howden (two males, nine females); 6 miles E San Cristóbal de las Casas, 2.vi.1969, H.F. Howden (one male, two females); 10 miles E Teopisca, 11–12.v.1969, H.F. Howden (two males, four females); junction of highways 190 and 195, 8.v.1969, H.F. Howden (one male, two females). All of the Chiapas specimens are from the Canadian Museum of Nature. The following specimens represent country records for Guatemala: Baja Verapaz, San Rafael Chilascó, 1700 m, viii.2000, horse manure, A. Higueros (two males); Baja Verapaz, San Rafael Chilascó, 1700 m, 17.iii.2000, H. Morales (one female); Huehuetenango, road between Bulej and junction of San Mateo Ixatán-Nentón, 2700 m, conifer forest, 22.vii.1988, E.B. Cano (three females); Sacatepequez, Florencia, 15.ix.1990, J Martínez (two males, one female); San Marcos, La Fraternidad, 1900 m, viii.1997, cloud forest, J. Monzón (one male); San Marcos, La Fraternidad, 1900 m, ix.1998, A.C. Bailey and J. Monzón (one male, one female); Totonicapán, San Cristóbal Totonicapán, 2300 m, 9.vii.1995, E.B. Cano (one male, one female). All of the Guatemala specimens are from the Universidad del Valle de Guatemala.

Onthophagus durangoensis Balthasar, 1939

In their catalogue of the Onthophagini of the Western Hemisphere, Pulido Herrera and Zunino (Reference Pulido Herrera, Zunino, Zunino and Melic2007) placed O. mextexus Howden and Cartwright, 1970 in synonymy with O. durangoensis Balthasar, 1939. However, O. mextexus is reported to be distributed from Texas, United States of America to Puebla, Mexico, and therefore does not match the toponymy given by Balthasar (Reference Balthasar1939) of Durango. Moreover, the description of O. durangoensis is clear that it has an apically shiny and punctate pygidium with the rest of the surface alutaceus and nearly impunctate (Balthasar Reference Balthasar1939: 45–46). These are one of the main characteristics given by Howden and Cartwright (Reference Howden and Cartwright1963) to differentiate O. knulli Howden and Cartwright, 1963 from O. mextexus. It would seem, therefore, that Pulido Herrera and Zunino (Reference Pulido Herrera, Zunino, Zunino and Melic2007) confused O. knulli with O. mextexus, establishing an incorrect synonymy.

The two specimens (male and female) Balthasar (Reference Balthasar1939) used for his original description carry labels reporting the type locality as Canelas, Durango (Bezděk and Hájek Reference Bezděk and Hájek2013). Balthasar (Reference Balthasar1939) also made the comment that his new species probably pertained to group 8, as established by Boucomont (Reference Boucomont1932).

A photographic comparison of the types of O. durangoensis (Figs. 12, 15, 18) (taken by Jiří Hájek), with O. knulli and O. monticolus (taken by Serge Laplante), confirms without doubt that O. mextexus is a valid species and not a synonym of O. durangoensis, as erroneously established by Pulido Herrera and Zunino (Reference Pulido Herrera, Zunino, Zunino and Melic2007). It also revealed that O. durangoensis and O. knulli are conspecific, based on the pronotal puncture pattern seen in the photographic analysis. Therefore, we correct this error and establish the following new synonymy: O. knulli Howden and Cartwright, 1963 = O. durangoensis Balthasar, 1939.

This species has been reported for Arizona and New Mexico in the United States of America and Durango, Jalisco, Colima, Michoacán, Morelos, Federal District, and Oaxaca in Mexico. It is here reported for the first time for Sinaloa, Mexico based on three female specimens from Copala, 7.vii.1968, Halffter, Martínez, Reyes (Instituto de Ecología, Xalapa collection). The presence of O. durangoensis in Oaxaca merits confirmation, because intensive collecting by A.A.-J. in this state over the last years has not produced any specimens of this taxon. Martínez-Falcón et al. (Reference Martínez-Falcón, Zurita, Ortega-Martínez and Moreno2018) report it (as O. knulli) for the Juniperus Linnaeus (Cupressaceae) forests of the state of Hidalgo, Mexico. This is probably an identification error; O. mextexus and O. alluvius have been reported for this state (Delgado and Márquez Reference Delgado and Márquez2006).

Onthophagus mextexus Howden and Cartwright, 1970

As previously mentioned, Pulido Herrera and Zunino (Reference Pulido Herrera, Zunino, Zunino and Melic2007) erroneously established the following synonymy: O. mextexus Howden and Cartwright, 1970 (replacement name for O. monticolus Howden and Cartwright Reference Howden and Cartwright1963) = O. durangoensis Balthasar. Onthophagus mextexus is here resurrected as a valid species.

This species has received recent attention (Huerta Crespo and Cruz Rosales Reference Huerta Crespo and Cruz Rosales2016; Huerta Crespo et al. Reference Huerta Crespo, Arellano Gámez, Cruz Rosales, Escobar Sarria and Martínez Morales2016; Halffter et al. Reference Halffter, Cruz and Huerta2018) as an important component for sustainable tropical cattle ranching in the State of Veracruz, Mexico. It is found in cloud, Quercus, Pinus-Quercus forests, secondary vegetation, shaded plantations, and paddocks. It can be found in moderately technified ranches that are surrounded by forests.

The species is known to occur in Texas in the United States of America and Nuevo León, Hidalgo, Puebla, Guanajuato, and Veracruz in Mexico. It is here reported for the first time for San Luis Potosí based on one male and seven female specimens from 20 km W Xilitla, 1600 m, 12.vi–6.viii.1983, cloud forest, flight interception trap, S. and J. Peck (Canadian Museum of Nature collection).

The Onthophagus anthracinus species complex

We establish the O. anthracinus species complex as having the following characteristics: anterior edge of pronotal punctures lacking tubercles; pygidial punctures very shallow, at least in basal half, sometimes deep and distinct if apical half of pygidium is shiny; male with pronotal protuberance; female with protuberance usually feebly indicated; pronotal punctures not crowded, separated by at least one diameter, anterior edge of pronotal punctures lacking any small shiny tubercle; surface dull, alutaceous, brown or black; length less than 7.5 mm.

Key to the species in the Onthophagus anthracinus species complex

The Onthophagus landolti species group

Boucomont (Reference Boucomont1932) published a synopsis of the Neotropical Onthophagus. In this work, he established what he called the “8th group” of Onthophagus, encompassing the species of what is now called the O. landolti species group: O. anthracinus Harold, 1873, O. arizonensis Schaeffer, 1909, O. atrosericeus Boucomont, 1932, O. chryses Bates, 1887, O. columbianus Boucomont, 1932, O. cribricollis Horn, 1881, O. igualensis Bates, 1887, O. iodiellus Bates, 1887, O. hoepfneri Harold, 1869, O. landolti Harold, 1880, O. lecontei Harold, 1871, O. longimanus Bates, 1887, and O. rufescens Bates, 1887.

Later, Zunino and Halffter (Reference Zunino and Halffter1997) redefined this group and renamed it the O. landolti species group and added: O. aciculatulus Blatcheley, 1928, O. alluvius Howden and Cartwright, 1963, O. brachypterus Zunino and Halffter, 1997, O. digitifer Boucomont, 1932, O. knausi Brown, 1927, O. knulli Howden and Cartwright, 1963, O. lebasi Boucomont, 1932, O. mariozuninoi Delgado, Navarrte and Blackaller, 1993, O. mextexus Howden and Cartwright, 1970, O. schaefferi Howden and Cartwright, 1963, O. subopacus Robinson, O. tuberculifrons Harold, 1871, and O. zapotecus Zunino and Halffter, 1988. Subsequently, Howden and Génier (Reference Howden and Génier2004) incorporated the following species to the O. landolti species group: O. altivagans Howden and Génier, 2004, O. canelasensis Howden and Génier, 2004, O. dubitabilis Howden and Génier, 2004, O. gibsoni Howden and Génier, 2004, and O. pedester Howden and Génier, 2004 and established the O. lecontei–O. subopacus species complex.

Recently, Moctezuma et al. (Reference Moctezuma, Rossini, Zunino and Halffter2016) described another species for the O. landolti species group, O. martinpierai Moctezuma, Rossini, Zunino, Halffter, 2016. They also established another species complex consisting of O. martinpierai, O. mariozuninoi, and O. dubitabilis.

We present below an updated list of the species belonging to the O. landolti species group, including three species complexes, the O. lecontei–O. subopacus species complex as defined by Howden and Génier (Reference Howden and Génier2004), the O. mariozuninoi species complex as defined by Moctezuma et al. (Reference Moctezuma, Rossini, Zunino and Halffter2016), and the O. anthracinus species complex as defined in this paper. Onthophagus columbianus Boucomont, 1932 drops from this list because it was recently placed in junior synonymy with Onthophagus elegans Klug, 1832, a Madagascan species (Rossini and Vaz-de-Mello Reference Rossini and Vaz-de-Mello2016).

Checklist of the Onthophagus landolti species group

Onthophagus anthracinus species complex

Onthophagus alluvius Howden and Cartwright, 1963

Onthophagus anthracinus Harold, 1873

Onthophagus durangoensis Balthasar, 1939

Onthophagus etlaensis Kohlmann, Escobar-Hernández, and Arriaga-Jiménez, new species

Onthophagus mextexus Howden and Cartwright, 1970

Onthophagus lecontei–Onthophagus subopacus species complex

Onthophagus altivagans Howden and Génier, 2004

Onthophagus canelasensis Howden and Génier, 2004

Onthophagus gibsoni Howden and Génier, 2004

Onthophagus lecontei Harold, 1871

Onthophagus subopacus Robinson, 1940

Onthophagus mariozuninoi species complex

Onthophagus dubitabilis Howden and Génier, 2004

Onthophagus mariozuninoi Delgado, Navarrete, and Blackaller, 1993

Onthophagus martinpierai Moctezuma, Rossini, Zunino, and Halffter, 2016

Species not assigned to species complexes

Onthophagus aciculatulus Blatchley, 1928

Onthophagus atrosericeus Boucomont, 1932

Onthophagus brachypterus Zunino and Halffter, 1997

Onthophagus chryses Bates, 1887

Onthophagus cribricollis Horn, 1881

Onthophagus digitifer Boucomont, 1932

Onthophagus hoepfneri Harold, 1869

Onthophagus igualensis Bates, 1887

Onthophagus iodiellus Bates, 1887

Onthophagus knausi Brown, 1927

Onthophagus landolti Harold, 1880

Onthophagus lebasi Boucomont, 1932

Onthophagus longimanus Bates, 1887

Onthophagus pedester Howden and Génier, 2004

Onthophagus rufescens Bates, 1887

Onthophagus schaefferi Howden and Cartwright, 1963

Onthophagus tuberculifrons Harold, 1871

Onthophagus zapotecus Zunino and Halffter, 1988

Acknowledgements

We thank Jack Schuster and Enio Cano for allowing B.K. to study the insect collection of the Universidad del Valle de Guatemala and to Dr. Santiago Zaragoza for access to the National Insect Collection of Mexico. We also thank Susana Guzmán-Gómez for taking several photographs used in this paper. We are also indebted to François Génier, from the Canadian Museum of Nature, for the loan of material of the O. anthracinus species complex; photographs of O. alluvius, O. knulli, and O. mextexus; and relevant literature and information regarding O. anthracinus. We would also like to thank Michele Rossini and François Génier with their help in the interpretation of the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature. We would like to thank Serge Laplante, Canadian National Collection of Insects, Arachnids, and Nematodes, for taking photographs of the holotypes of O. knulli and O. monticolus; Fernando Vaz-de-Mello for sharing photographs taken by Jiří Hájek from the Národní Muzeum, Prague, Czech Republic, of the syntypes of O. durangoensis; and Sara Rivera-Gasperín from the Institute of Ecology, for taking the photographs of the internal sac lamellae. Last but not least, we would like to thank Jane Segleau for checking the English language. Collections in Oaxaca for the new species were financed by the Rufford Foundation through the RSG grant 20054-1 given to A.A.-J.