Introduction

Cultural vocabulary tends to overstep ethno-linguistic boundaries with relative ease. In the case of the nineteenth-century Indian Ocean, it is thanks mostly to Amitav Ghosh’s best-selling novel Sea of Poppies that this fascinating story of lexical cross-fertilisation “from below” has not yet sunk into the depths of oblivion.Footnote 1 He drew ample inspiration from the wealth of data left by colonial-era lexicographers, such as Lieutenant Thomas Roebuck—a professional linguist with a more than keen eye for sailing matters. Yet the diverse cadre of sailors at the core of such treatises have influenced the linguistic landscape of the Indian Ocean more significantly than any writer, then and now, has given them credit for. To see this demonstrated we need only look eastwards. In his monograph on the jargon of Malay-speaking sailors, Dutch lieutenant-colonel A. H. L. Badings recorded the expression tjoerdej agil boelin jang proewan.Footnote 2 What neither the author nor those using his dictionary appear to have realised is that the entire “Malay” sentence was taken over verbatim from Laskarī, South Asia’s once prevalent nautical slang with a grammatical core from HindustaniFootnote 3 and loanwords from several other languages: chor de āgil būlin yāhom parvān (“let go the head bowlines, square the yards”).

How influential was the language of these “lascars,” that is, European-employed ship crew or militiamen hailing predominantly from Gujarat and Bengal?Footnote 4 What more forgotten connections can be established through a study of lexical borrowing? Loanwords in the languages encircling the Indian Ocean offer a fruitful and faintly trodden way to tie together the fragments left behind by sailors and other neglected agents of the past, many of whom continue to elude scholarship. Indian Ocean historiography disproportionately features kings, merchants, conquerors, religious scholars, money-lenders, European colonial officials, and those with whom they interacted. On the margins, however, unfolded a largely parallel world aboard ships, in harbours, tailor shops, kitchens, brothels, and prisons—often leaving nothing behind except one crucial thing: language. There has been a renewed interest within Indian Ocean studies in the lives of these “subalterns,”Footnote 5 yet little has been written thus far from a language-centric perspective.

The present study, hence, aims to delve deeper into the transmission of “culture words”Footnote 6 between ports around the Indian Ocean and slightly beyond. This demonstrates how an investigation of lexical borrowing can substantiate our historical understanding of cultural contact—that is, long-standing interaction between different communities typically resulting in knowledge exchange—and expand our methodological toolkits to study this phenomenon. The often forgotten connections between different port cities—rather than between ports and their hinterlands—speak to a growing interest within Indian Ocean studies in communities oriented towards the seaFootnote 7 and long-distance contact between non-European societies.Footnote 8 Loanwords can also add substance to ongoing debates on what some authors call the “Indian Ocean world” and the extent to which this imagined space constitutes a unified area. On account of climatological factors, cultural convergence, and economic interdependence, a number of scholars have espoused the idea that the Indian Ocean has become an integrated whole. Others however distinguish several units within the ocean, arguing that the area must be seen as interregional if not global.Footnote 9 The question of whether the Indian Ocean constitutes a “world” is further complicated by the fact that not all its sub-regions enjoy equal quantities of academic attention and available source material. I propose that this imbalance can in part be redressed by expanding the focus to language, which has been notoriously absent in previous debates on the ocean’s presumed unity.Footnote 10 Marginalised communities—such as sailors, artisans, household personnel, and exiles—rarely left easily available written documents, yet their lexical imprint on those with whom they interacted provides valuable insights into processes of cultural contact and, hence, knowledge exchange. It is, of course, impossible to exhaust this topic and I must at this point be content with scraping the surface, in particular since I am most familiar with the linguistic situation of maritime Southeast Asia. Yet, on a methodological level, adding a dimension of lexical borrowing to the study of the Indian Ocean is crucial, for it offers an analytical approach to reconstruct the trajectory of words—and the associated products, trends, and ideas—from one ethno-linguistic community to another and hence assess their historical connectedness.Footnote 11

The present study focuses on the long nineteenth century, but will also pay attention to events leading up to this period. On the one hand, this was a period of decline for Asia’s great empires, including China’s Qing Dynasty, the Ottomans, the Sultanate of Aceh, and the Mughals, although the latter’s elaborate court culture continued to influence neighbouring elites. On the other hand, it saw continued mobility across much of the Indian Ocean, albeit now largely under European control. Steam-powered ships entered the waters of Africa and Asia from the early 1820s, although multiple-masted sailing vessels remained relevant for decades to come. Mercantile groups from Kutch and Gujarat migrated in unprecedented numbers to coastal eastern Africa.Footnote 12 Elsewhere, too, colonial subjects found opportunities to move between a number of nodes connecting the vast expanses of Empire, while the annual hajj to Mecca connected a growing number of Islamic nations. The Persian language was in use by the educated classes from the Ottoman Empire to the Indian subcontinent and—into the nineteenth century—in some port cities of Southeast Asia.Footnote 13 It is within these maritime zones of contact that societies influenced and learned from each other in ways not always fully understood. Only from the nineteenth century onward do we possess sufficient data to examine these connections comparatively, due to a small contingent of European authors interested in previously undocumented nautical and other cultural vocabularies of the communities under colonial rule.Footnote 14 While lexicographic scholarship existed in previous centuries too, it was unconcerned with cultural terms beyond Europe’s direct academic curiosity. The extant versions of Malay and other non-European texts cited in this study—while they are attributed to earlier times—are also very much a product of nineteenth-century knowledge formation, with more archaic versions no longer available. These non-European texts differ from the European-authored vocabularies in that none of the lexical items they contain, on which I partly base my analysis, are explained. Hence, words that have meanwhile become obsolete can at present only be understood through a comparison with other languages, as demonstrated further in this study.

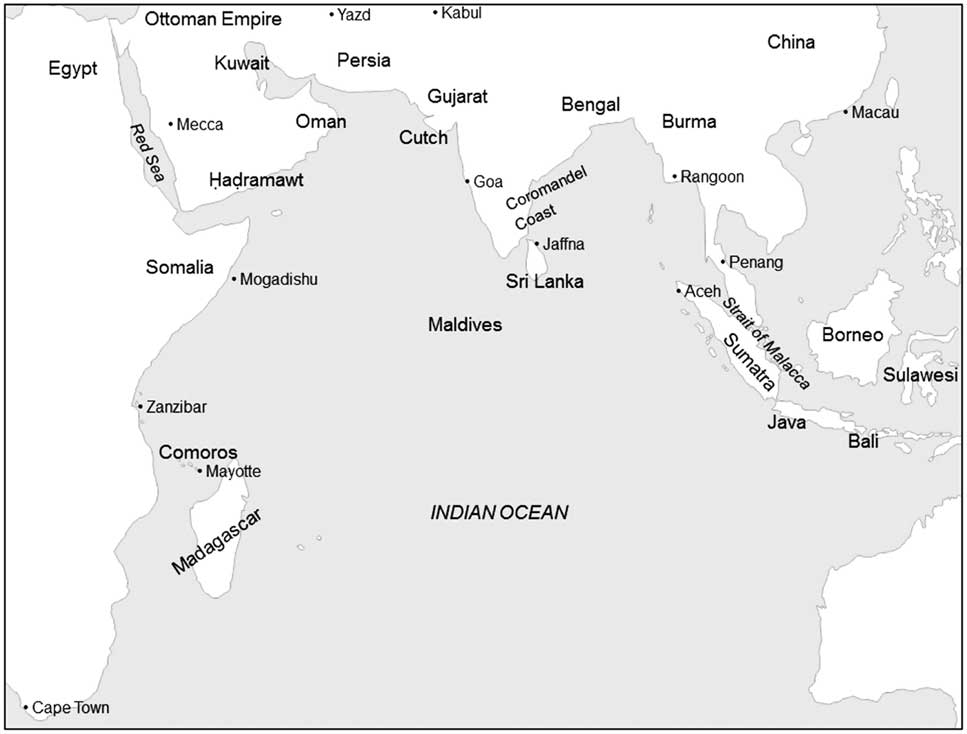

In what follows, four case studies of cultural contact are highlighted along with the loanwords substantiating them. I begin with the very facilitators of maritime mobility and hence of trade and economic growth: sailors. They were, in the words of Amitav Ghosh, “among the first to travel extensively; the first to participate in industrial processes of work; the first to create settlements in Europe; the first to adapt to clock-bound rhythms of work-time; and they were the first to be familiar with emergent new technologies.”Footnote 15 While sailors were the “muscles of Empire,”Footnote 16 they nevertheless constituted “an invisible underclass in historical studies.”Footnote 17 As will be demonstrated, part of their cultural impact lies in the words they used and the associated novel concepts they introduced. The economic growth enabled by sailors also opened the door to further exchanges between non-European societies. Among the cargoes they shipped from port to port was another key constituent of Indian Ocean capitalism and social differentiation: items of dress. As international shipping increasingly connected the port towns of the Indian Ocean,Footnote 18 so too did their inhabitants develop sartorial preferences that set them apart from less extravagantly dressed communities in the hinterlands. Tailored garments, footwear, and sought-after Indian textiles made them part of a visibly distinct class of sophisticated urbanites. In addition to attire, the same people suddenly also had access to a much more variegated diet.Footnote 19 South Asian cooks in particular transformed the foodscapes of the Indian Ocean, introducing a cuisine that was itself a rich blend of subcontinental and Persian influences, and that was able to flourish under wealthy patronage.Footnote 20 Malay cuisine, too, spread far beyond Southeast Asia in a history of forced displacement initiated by the Dutch East India Company. Finally, this study calls attention to those facets of language that even the boldest European lexicographers had scruples about documenting: criminal slang, swearwords, and other epithets deemed offensive. Taking nineteenth-century Penang as an example, we see that urban dialects often became repositories of forgotten contacts between cultural brokers beyond the interests—and hence the archives—of colonial officials. These four case studies complement each other in their predisposition towards non-European encounters in port cities. Their selection for the present article is due to the fact that they can all be approached through the lens of language, and as such offer otherwise unavailable perspectives on the interconnected past of the Indian Ocean (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Geographical names mentioned in this article.

Lascars and Their Vocabularies

Large-scale shipping has from time immemorial relied on multiethnic crews. Thus far, most linguistic attention has gone to the widely used nautical slang of the Mediterranean.Footnote 21 Unfortunately, the philology-obsessed academics of Empire paid little attention to “the barbarous dialect of the ‘lascars.’”Footnote 22 Nevertheless, it may be argued that a number of Indian Ocean ports underwent a comparable stage of lexical convergence in the domain of nautical terminology. Contact between ship crews from Hindustani, Tamil, Malay, and other linguistic backgrounds, who often worked on the same European-owned vessels, resulted in the exchange of specific maritime vocabulary among these communities. Several examples are outlined below in support of this claim. We may also call attention to a passage from the Hikayat Banjar, a Malay chronicle belonging to a royal dynasty from the pepper-rich southeast of Borneo, compiled and enlarged over many centuries. Although the (imprecisely dated) text never directly mentions Europeans, certain passages feature firearms and European-type watercraft, placing it at least partly in an early modern context. Of particular interest to us is a description of a rich merchant (saudagar) and, later in the text, of his armada:

In the beginning there was a merchant of Kaling by the name of Saudagar Mangkubumi. He was extremely rich and possessed innumerable warehouses, ketches (keci), decked ships (kapal), sloops (salup), flat-bottomed one-masters (konting), trading-cruisers (pancalang) and galleons (galiung) … frigates (pargata), cargo-boats (pilang), galleys (gali), galleons (galiung), corvettes (gurap), galliots (galiut), pilaus, Siamese junks (som), Chinese junks (wangkang) and decked ships (kapal), (so many that) it looked as if they were off to invade a country.Footnote 23

Few documents could have demonstrated more vividly how outwardly oriented coastal life had become in early modern Southeast Asia. From the Portuguese, who were quick to employ Asian shipwrights to build their seafaring vessels,Footnote 24 various communities of Southeast Asia and elsewhere in the Indian Ocean world learned how to construct such ship types as the galley (galé), the galleon (galeão), and the frigate (fragata). British nautical influence is also reflected in texts like the Hikayat Banjar—which mentions “galliots,” “ketches,” and “sloops”—but not at the cost of local Indonesian boat types, such as the pencalang, pelang, and konting. Meanwhile, the som and wangkang might reflect southern Chinese influence, whereas the pilau and kapal presumably come from Tamil-speaking South India. The gurap, finally, was a galley-type vessel from the Middle East—reflecting the Arabic word ghurāb, “raven”—commonly found across the Indian Ocean and already mentioned by the fourteenth-century traveller Ibn Baṭṭūṭa.

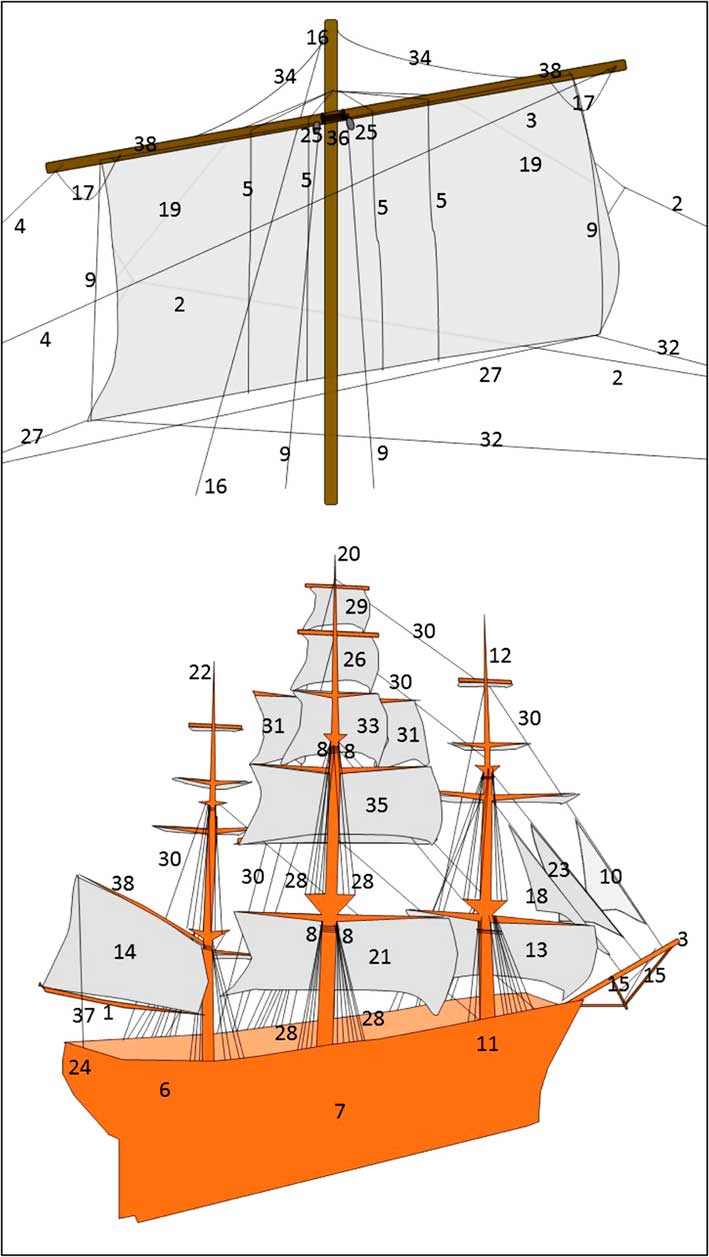

Needless to say, it is difficult to assess whether the rich variety of watercraft juxtaposed in the Hikayat Banjar is to be taken at face value. What can these types of ships tell us beyond the observation that the author of the text was aware of their existence? Did a ruling dynasty from southeast Borneo really possess European-built ships, were the vessels locally manufactured and based on European prototypes, or did the passage merely reflect a fictional desire to elevate the status of a local dynasty? In isolation, such social and economic inferences from literary texts may raise more questions than they answer. In combination with additional lexical data, however, they provide opportunities to examine the significance of otherwise elusive ship crews. In the words of Amitav Ghosh, “what really sets a sail ship apart from other machines is that its functioning is critically dependent on language: underlying the intricate web of its rigging is an unseen net of words without which the articulation of the whole would not be possible.”Footnote 25 What words, then, were used aboard the European-inspired and European-owned schooners, frigates, pinnaces, sloops, and other ships crewed by sailors from South and Southeast Asia? Information on this topic is scarce and often inaccurate, since few lexicographers were accomplished sailors. The missionary Benjamin Keasberry dedicated some pages of his Malay vocabulary to “nautical terms as used in country vessels manned by Malay or Javanese crew.”Footnote 26 It will no longer surprise us to find the vocabularies of the South Asian lascars echoed in those of their Southeast Asian colleagues, although the India-born author did not apparently notice their subcontinental provenance. So, the appropriate Malay command for “bracing around the head-yard” was ferow agel (Laskarī: phirāo āgil). When changing tack (“Ready about!”), the Malay-speaking captain would shout tiyar jaga-jaga (Laskarī: taiyār jagah-jagah). More detailed nautical dictionaries of Malay became available in the late nineteenth century.Footnote 27 These works contain detailed descriptions of the numerous parts of European-type vessels and especially their rigs, many of which contain further Laskarī loanwords originating from the ports of the Indian subcontinent. Nevertheless, it was not until recent times that the Laskarī impact on some of the nautical slangs of maritime Southeast Asia was (re)discovered. Horst Liebner—a professional sailor with a more than keen eye for linguistic matters—touches upon it in his lexical study of Sulawesi’s seafaring communities.Footnote 28 In nineteenth-century Malay, we can find several additional instances of Laskarī influence. Examples include bara for “main” (from baṛā “big”), agil for “fore” (āgil), nice for “lower” (nice), upar for “upper” (ūpar), and dol or dul for “top mast” (dol “mast”). Other words are from English, yet seem to have reached the Malay sailors through India: bulin from būlin “bowline,” paslin from pāslīn “parcelling,” pelanjib from phalāne-jīb “flying jib,” and baksi from bāksī “aback (of the sail),” the latter presumably consisting of “back” and the Hindustani adjectival suffix –sī. Several more Laskarī loanwords once in use among Malay-speaking sailors are listed in Table 1 (and see Figure 2 for an illustration of the parts a nineteenth-century European-type sailing ship).

Figure 2 Ship parts mentioned in this article: 1. Boom, 2. Bowline, 3. Bowsprit, 4. Brace, 5. Buntline, 6. Cabin, 7. Cargo hold, 8. Catharpins, 9. Clewline, 10. Flying jib, 11. Forecastle, 12. Foremast, 13. Foresail, 14. Gaffsail, 15. Guy, 16. Halliard, 17. Horse, 18. Inner jib, 19. Leechline, 20. Main mast, 21. Mainsail, 22. Mizzenmast, 23. Outer jib, 24. Poop-deck, 25. Quarter-block, 26. Royal sail, 27. Sheet, 28. Shrouds, 29. Skysail, 30. Stays, 31. Studding sail, 32. Tack, 33. Topgallant sail, 34. Topping lift, 35. Topsail, 36. Truss, 37. Vang, 38. Yard.

Table 1 Nineteenth-century Malay and Laskarī nautical terms

Beyond the Malay World, the presence—and, hence, lexical imprint—of South Asian lascars was felt in different littoral societies of the Indian subcontinent. Table 2 juxtaposes the shared vocabularies of sailors speaking Laskarī, Malay, Tamil, and Dhivehi.Footnote 29 Some terms were European introductions, such as gāvī “topsail,” istiṅgī “clewline,” kālāpattī “caulking,” kamarā “cabin,” mantīla “topping lift,” phālkā “hatch,” and trikat “foresail” from Portuguese (respectively gávea, estingue “brails,” calafate “a caulker,” cámara, mantilha, falca “bulwark, washboard,” and traquete) and brās “brace,” būm “boom,” ghaī “guy,” and jīb “jib” from English.Footnote 30

Table 2 Laskarī terms in the eastern Indian Ocean

Other shared nautical terms found in multiple Indian Ocean ports betray Middle Eastern origins and are also attested in the Arabian Sea. Swahili, the most widely spoken language of coastal East Africa, features several of the Perso-Arabic nautical terms also found farther east (Table 3).Footnote 33

Table 3 Shared nautical terms in the western Indian Ocean

Terms for ship-related professions also display similarities across the Indian Ocean. In this realm, the Persian language was of key importance from at least medieval times (see Table 4), when nautical vocabulary from that language first found its way into Arabic texts and presumably into the languages of East Africa, South Asia, and the Malay World.Footnote 35 The word for “captain” is a case in point; it comes from the Persian compound nāv-khudā “ship-master” and is now found across the Indian Ocean. Other loanwords can be connected specifically to lascars from the Indian subcontinent. The most widespread Indian Ocean word for “sailor,” known in nineteenth-century Anglo-Indian as classy, acquired its nautical meaning on the Indian subcontinent from the original meaning of “freedom” (Arabic: khalāṣī); in the Arabic variety of Kuwait it was subsequently back-borrowed as khalāsi “sailor.”Footnote 36

Table 4 Ship-related professions in the Indian Ocean

Having underscored the importance of the lascar, as he was known to Europeans, or the khalāṣī, as he called himself, it is now time to delve deeper into his cargo. The next section highlights a vital part of Indian Ocean commerce: items of dress. In doing so, it explores the extent to which sartorial vocabularies mirror nautical ones in their geographical distribution.

Coastal Customs and Costumes

In exploring the vocabularies of tailors, we must recall that South Asian communities played a central role matching the geographic centrality of the subcontinent. It is hardly an exaggeration to state that “India clothed the world”Footnote 37 due to its ancient pedigree in the export of cotton, silk, muslin, linen and wool.Footnote 38 Indian textiles show up by the fifth century CE in the archaeological record of the Red Sea and—roughly around the same time—in the Indonesian archipelago.Footnote 39 The reputation of India’s prestigious cottons remained spotless through the medieval period.Footnote 40 By this time, three regions in particular had come to the fore as suppliers to almost the entire Indian Ocean: Gujarat, Bengal, and the Coromandel Coast—a situation that persisted into colonial times. These high-priced commodities were for long the prerogative of affluent coastal elites. In East Africa, for example, robes, sandals, and jewellery were largely confined to the elites and their enslaved domestics,Footnote 41 which was presumably also common in other locations situated at some distance from the major textile production centres. The cultural orientations of the elites, it seems, were inspired by what came from the ocean rather than the hinterland.

The interconnectedness of Indian Ocean textile traditions has been the topic of prodigious scholarship,Footnote 42 yet more can be done in terms of studying loanwords.Footnote 43 Before moving to a cross-linguistic comparison of sartorial terminology, it is important to first point out that India’s vestimentary imprint on the world went beyond the mere distribution of mass-produced textile goods by mercantile communities. In some regions, the art of tailoring itself may have diffused in the wake of intensified contacts with India. A number of lexical borrowings into Malay and related languages of maritime Southeast Asia point to a subcontinental origin of this practice. The word for “tailor” in the Sejarah Melayu—a mid-sixteenth-century chronicle describing the history of the Malacca Sultanate and its relations to other lands—is derji, i.e., Hindustani darjī and ultimately Persian darzī. This loanword presumably entered Malay in the wake of intensified contacts with South Asian sultanates, with which commercial links had long been established and whose tailors may have set up shop farther east. Even earlier, we find the word for “cotton” travelling from South (Hindustani, Gujarati: kapās) to Southeast Asia (Malay, Javanese: kapas). Words for “spinning wheel,” too, entered maritime Southeast Asia from the Indian subcontinent. Malay jentera goes back to Sanskrit yantra “machine, mechanical contrivance,” which also denotes a “spinning wheel” in a number of modern Indian languages.Footnote 44 The Hindustani word carkhā “hand spinning wheel” (cf. Tamil: carkkā, Persian: charkh) also spread eastwards and was borrowed in the languages of North Sumatra (Acehnese: jeureukha, Gayo: cerka, Toba Batak: sorha, etc.). In the absence of datable textual references, however, the time depth of these transmissions is difficult to reconstruct.

The distribution of garments increased when the Indian Ocean became—as the expression goes—an “Islamic lake.” Islamic law came with specific prescriptions for covering the male and female body, undoubtedly boosting the trade in sartorial items. It would be incorrect, however, to assume that shirts, jackets, and suchlike were absent in pre-Islamic times, or were only distributed within Muslim circles. In maritime Southeast Asia, a type of upper garment known as baju (from Persian and Hindustani bāzū) was used for ritual and military purposes before it eventually became widespread among all classes of men and women.Footnote 45 Trousers also entered the Malay World from South Asia; the widespread Malay names seluar and celana reflect respectively Hindustani shalwār “trousers, drawers” and Kannada or Tulu callaṇa “short breeches.” In Java, this transmission took place in pre-Islamic times, again in connection with developments in military attire.Footnote 46

In terms of footwear, a North Indian word for “sandals” (Hindustani: cappal, Gujarati: campal) was borrowed both east (Malay: capal) and west (Swahili: champal), while Portuguese sapato “shoe” was adopted as Malay sepatu, Sinhala sapattu, Tamil cappāttu, and Ḥaḍramī Arabic sfattū (the latter via Malay). The Portuguese were also apparently responsible for the eastward distribution of a number of other garments. I suspect that Malay kebaya “loose garment worn by women” reflects Creole Portuguese cabaia, cabai (cf. Tamil: kapāy), which itself goes back to Sinhala kabā-ya “coat.”Footnote 47 Along similar lines, Portuguese camisa “shirt” must have given rise to Sinhala kamisa-ya and Malay kemeja. Similar-looking words such as Hindustani qamīz and Tamil kamis reflect Arabic qamīṣ, which is ultimately related to the Portuguese form through a shared etymology from Late Latin camisia “shirt.” Some articles of attire have spread even more widely across the Indian Ocean. Table 5 lists some sartorial terms found from East Africa to Southeast Asia.

Table 5 Textile terms in the Indian Ocean

Other items of dress display more specific patterns of distribution. In Aceh, we find woven cloths known as lunggi, which is evidently Hindustani and/or Bengali luṅgī “a coloured cloth” (from luṅg “a cloth worn round the loins”). It was also borrowed into Burmese as loungji, now regarded as the country’s national costume. Conversely, the Malay sarung, a cloth wrapped around the waist, spread westwards and was adopted in Sinhala as saroma and in Sri Lankan Tamil as cāram, among others.Footnote 50 In the seventeenth century, the then Dutch-controlled trading post of Pulicat became India’s most important centre to produce and export sarongs locally.Footnote 51 In the Ḥaḍramawt region of present-day Yemen, the homeland of most of the Indian Ocean’s Arab diaspora, the cloth is known as ṣārūn in the local dialect. The latter form must have given rise to Swahili saruni in the same meaning.

The presence of Malay items of dress in Sri Lanka is not surprising in the light of the island’s colonial history. Coterminous with the establishment of Dutch rule in seventeenth-century Sri Lanka, large numbers of “Malay” (yet in fact quite diverse) people arrived on the island as political exiles, soldiers, or personnel in service of the colonial regime.Footnote 52 The Dutch East India Company (VOC) created another such colony in Cape Town, which was different in its political organisation but similar in its heterogeneous demography of convicts, military personal, and enslaved workers. In both places, intermarriage between “real” Malays, South Asian Muslims, and other groups was common. Unlike the Sri Lanka Malays, the so-called Cape Muslims eventually lost proficiency in Malay and their other ancestral languages to Afrikaans. Apart from religion, food was to become this group’s most important identity marker.Footnote 53 This brings us to culinary traditions as an additional lens to examine cultural contact and the movement of its neglected brokers in the Indian Ocean.

Spice-Laden Foodscapes

From antiquity onwards, the regional food markets of the Indian Ocean were connected for pragmatic reasons, including the redistribution of food surpluses and the sustenance of diasporic communities.Footnote 54 Beyond basic necessity, imported culinary traditions also fuelled new cultural expressions, with food items brought in from afar enjoying greater prestige. We may therefore assume that cooks and their recipes started to travel between Indian Ocean ports the moment contacts became regular. The resultant mixed culinary landscape is illustrated in a mid-seventeenth-century Malay biography of Iskandar Muda, the sultan of Aceh in North Sumatra, called Hikayat Aceh. In a description of a wedding feast at the royal palace, the text juxtaposes numerous Persian, Arabic, and Hindustani terms for food-related items, many of which have now become obsolete in Sumatra. A literal translation of the relevant passage is provided first, before delving deeper into the actual dishes that were served.

The sufra was unfurled and the dishes were brought in, consisting of various types of food; taʿam kabuli, berenji, syarba, ʿarisya, bughra and kasykia; and various [types] of dampuk and kebab, and various types of halwa berginta, halwa kapuri, halwa sabuni and halwa syakar nabati; and various jugs of crushed syarbat with yazdi rosewater; some syarbat perfumed with eagle-wood and mawardi, and various daksa of paluda drenched with ʿasal masʿudi, and various daksa of beautiful fruits most delicious in flavour.Footnote 55

The use of these and other culinary terms as a frame of analysis brings to the fore specific instances of cultural contact. While the Indian Ocean never processed a unified cuisine, its foodways have emerged from centuries of gastronomic convergence. Loanwords reveal some of the communities involved in this process, as well as the directions of transmission. Let us consider the above citation. The word sufra, judged from the context, denotes a cloth on which meals were served. It is well known that table-cloths were indispensable during Mughal-era feasts,Footnote 56 likewise designated in Hindustani as sufra (ultimately from Arabic sufra “dining table,” cf. the root s-f-r connected with “travelling”). The phrase taʿam kabuli presumably reflects Persian kābulī t̤aʻām “a meal from Kabul.” Elsewhere in the text the more common nasi kabuli “Kabuli rice” is used in the same meaning, reflecting the famous Afghan dish of steamed rice-and-meat (kābulī pīlāv). The second rice dish listed is berenji, going back to Persian birinj “rice.”Footnote 57 Syarba almost certainly refers to a type of soup, reflecting Persian shorbā “salty stew” and found under this name across the Muslim world.Footnote 58 The term ʿarisya presumably reflects harīsa, a Middle Eastern meat porridge with wheat and herbs. The dish known as bughra originally denoted a simple meat dumpling from Central Asia, named after the tenth-century ruler Satūq Bughrā Khān who has been credited with its invention.Footnote 59 Kasykia appears to be a misreading of Persian kashkīna, a dish made of barley or wheat.Footnote 60 I assume that dampuk goes back to Persian dampukht “a kind of pīlāv,”Footnote 61 which remains to this date a popular dish in parts of the Indian subcontinent. Kebab is, of course, the Persian kabāb: roasted meat, typically on skewers.

The Acehnese feast was equally abundant in sweet dishes. Halwa berginta seems to be a Malayisation of Acehnese halua meugeunta,Footnote 62 which is a triangular sweetmeat made of glutinous rice, grease, and sugarcane syrup.Footnote 63 Halwa kapuri presumably reflects (an unattested) Persian or Hindustani ḥalwā kapūrī “camphoraceous pudding,” possibly resembling or containing edible camphor. Halwa sabuni is the obsolete Mughal dish ḥalwā ṣābūnī, literally “saponaceous pudding.”Footnote 64 Halwa syakar nabati must have been a kind of sugary desert, as nabāti sakkar is the Persian word for “sugarcane.” Syarbat reflects Persian sharbat, a fragrant sweet beverage often containing fruits and ice (the English word “sorbet” ultimately goes back to the same etymon). The yazdi rosewater undoubtedly reflects Persian gulāb yazdī “rosewater produced in Yazd,” which was also enjoyed by the Mughals.Footnote 65 Mawardi is the Arabic word māwardī “rosewater.” Judged from the context, the word daksa is a type of vessel in which food is served.Footnote 66 Paluda is the Persian pālūda,Footnote 67 the name of a sweet beverage popular from East Africa to South Asia and already documented in medieval Arabic cookbooks.Footnote 68 The compound ʿasal masʿudi, finally, is the famous Mas‘ūdī honey exported from Mecca, which was also mentioned by the late twelfth-century Arabic geographer Ibn Jubayr.Footnote 69

Stumbling upon a similar dilemma as the array of boat names in the Hikayat Banjar, we may again ask how representative this arrangement of dishes was of culinary flows in Southeast Asia. Had the Acehnese only heard of these dishes from Perso-Indian merchants who had frequented their country since precolonial times, or did they regularly enjoy them personally? In this case, it is important to point out that Islamic dynasties in the Malay World often sought inspiration from Ottoman and Mughal courtly cultures, including in the realm of literature, arts, religion, and scholarship.Footnote 70 Against the backdrop of these royal connections, it seems that sophisticated cookery was a sine qua non in the repertoire of any self-respecting palace. The court of Siam employed an Indian cook specifically to cater to foreign guests, as documented in the seventeenth-century Safīna-i Sulaimānī.Footnote 71 This Persian travelogue also tells us of the fondness of the Acehnese sultan for Persian foods and sweets, which he implored rich merchants to bring him as they could not be prepared properly at his own court.Footnote 72 Among the Mughals, a sumptuous variety of West, Central, and South Asian dishes had reached new heights under the supervision of professional cooks.Footnote 73 Even for seasoned European colonials (pun not intended), it was not unheard of to hire Indian kitchen personnel. Thomas Stamford Raffles, for example, had a Kling (South Indian) cook of whom he was apparently so fond that the latter was granted a considerable piece of land in West Java.Footnote 74 Singapore’s founder was far from unique in his culinary preferences. It is illuminating in this respect to call attention to a popular 1875 cookbook titled What to Tell the Cook; or The Native Cook’s Assistant, which was published half in English and half in Tamil and was also advertised in Netherlands Indies newspapers (figure 3). Outside the European sphere, large ships provided additional employment for the so-called sea cooks, known in Hindustani as bhanḍārī.Footnote 75 Remarkably, a cook at the royal court is known in classical Malay literature as bendahari,Footnote 76 which is evidently the same word. The related Acehnese term muenaroe or beunaroe “cook of a royal kitchen,” too, reflects a tradition of employing prestigious “master-chefs” from South Asia. It is uncertain how widespread this practice was across the Indian Ocean, but we know from the Chronicle of Theophanes that cooks from the Indian subcontinent were present at the Byzantine court as early as the eighth century.Footnote 77

Figure 3 What to Tell the Cook. Photo by author.

One of the highlights of culinary cross-fertilisation in the Indian Ocean was without doubt a savoury flatbread known in Malay as murtabak (cf. Javanese: martabak, Acehnese: meutabak or meureutabak, Thai: mātābā, Hyderabadi Urdu: mutabbaq, Tamil: murtapā). Across South and Southeast Asia, cooks specialising in this dish tend to be of Ḥaḍramī or Muslim South Indian ancestry. This savoury fried flatbread ultimately hails from parts of Saudi Arabia and Yemen, where it is known as muṭabbaq “folded.” In Kuwait this word usually refers to a dish of rice and fish (muṭabbaq) and in other parts of the Arabic World to a sweet pastry (muṭbaq), as is the case in medieval Arabic cookbooks. It was the meat-filled version that quickly conquered the Indonesian archipelago (figure 4). No better ode to this dish can be given than a description by the Eurasian author Tjalie Robinson, who praised the famous murtabak of a Jakarta-based Indian cook as follows:

[T]hey have a crispy fried wrapping on which no single drop of drawn butter (minyak samin) can be detected anymore. I always like to watch the murtabaks being fried. Mr. Ali rolls the dough out so thinly that the pastry strip is almost transparent. In a large mug he then prepares the fillings (egg batter, pieces of fat and mutton, vegetables, onions, etc.) and pours the mash into the middle of the pancake. He then folds it like an envelope, swings it around a couple of times, and tosses it onto the baking sheet. It is a true mystery that those dough envelopes never break. I always watch that jugglery with bated breath, but the envelope truly never bursts open. Anyway, as soon as the thing sits on the round baking sheet, drawn butter is carefully poured around it before a heavy dash of margarine is added. Would they also do it like that in Malabar? With that margarine? Whatever the case, the grease starts to simmer and crackle and 15 minutes later that murtabak will land on your plate (piring), so big it protrudes on all sides, crisply fried and delicate in flavour.Footnote 78

Figure 4 Murtabak (Singapore). Photo by author.

One place where Indian and Malay cuisine merged never to be separated again is, paradoxically, just beyond the horizon of the Indian Ocean: Cape Town.Footnote 79 As mentioned previously, the city—established by the Dutch East India Company as a halfway station on the route to Asia—became home to the so-called Cape Muslims or Cape Malays. The latter ethnonym belies the group’s heterogeneity, with ancestors hailing from Indonesia, India, Sri Lanka, Madagascar, and several parts of Africa.Footnote 80 This hybridity is particularly manifest in their cuisine, which is a rich mixture of Malay, South Asian, European, and African flavours.Footnote 81 One finds in it dishes with recognisable Malay origins, like blatjang “k.o. chili sauce” (Malay: belacan “shrimp paste”), bobotie “curried meatloaf” (bebotok “spicy steamed fish or meat”), denning vleis “k.o. lamb stew” (dendeng “dried jerked meat”), sosatie “meat roasted on a skewer” (sate, sesate), and penang curry “a dry mutton curry” (pindang “dish prepared in salted and spiced sauce”).Footnote 82 Other delicacies, such as curry, roti, and biriyani, reflect South Asian influence,Footnote 83 with lexical influence from a North Indian language (barishap “fennel” from baḍīśep, dhunia “coriander leaves” from dhaniyā, jeera “cumin” from jīrā), but also from Tamil (naartjie “citrus” from nārattai). Yet most Cape Malay dishes are a blend of several of the culinary traditions in contact.Footnote 84 The murtabak mentioned above, for example, developed into muttabah: a meat and spinach pie topped with cheese.Footnote 85 Unsurprisingly, Indian Ocean success stories like falooda (i.e., pālūda), kebab, and kabuli rice also made their way into Capetonian kitchens.

Another colonial-era “melting pot,” also just beyond the limits of the Indian Ocean, is the city of Macau, which belonged to Portugal from 1557 to 1999. Though located off the coast of China, the culinary history of the Indian Ocean is palpable in the Macanese cuisine. Initially, the Chinese formed only a minority in this Portuguese colony, which was predominantly inhabited by Malay, Indian, and African traders, servants, and enslaved people.Footnote 86 Malay-inspired food names such as balichão “k.o. fermented fish sauce” (Malay: belacan “shrimp paste”)Footnote 87 and bebinca “coconut-milk cake” (bebingka) form an integral part of the city’s culinary tradition,Footnote 88 even though their Southeast Asian origins are not necessarily realised by all of its inhabitants. The first two dishes were also introduced by the Portuguese—or, rather, by their Asian cooks—to Goa on India’s west coast (balchão and bebinca), while sambal can be found wherever Malay and/or Javanese diasporas established themselves. Like Cape Town, Macau also features several pan-Indian Ocean dishes. Macanese lacassá is a bowl of noodles in shrimp broth. The Southeast Asian version (laksa) is a spicy soup with rice noodles and seafood, while in Cape Town it refers to vermicelli (laxa) used in sweet desserts. All terms originate from the Persian noodle dish lākhsha.Footnote 89 The triangular-shaped fried snacks known in Macau as chamuças reveal an equally interesting transoceanic journey. They already feature in medieval Arabic cookbooks as sanbūsaj, reflecting Middle-Persian sambōsag.Footnote 90 The fritters also occur as Swahili sambusa, semusa, Somali sambuusa, Hindustani sambūsa, samosa, Sinhala samosā, Tamil camōcā, Malay samosa, sambosa, Burmese sa̱muhsa, and Turkish samsa.

This culinary tale would not be complete without also giving attention to yet another Indian Ocean melting pot: the Swahili coast. The palpable North Indian element in Swahili cooking has not gone unnoticed.Footnote 91 Some dishes, however, turn out to be of a more pan-Indian Ocean distribution. Pickles are a case in point. Known as achari or achali in Swahili and typically made with mangos, lemons, or other sour fruits or vegetables, pickling was—and is—a safe and easy means of food-preservation. We find the word as ācār or acār in North Indian languages, Persian ācār, Sinhalese accāru, Tamil accāṟu, Dhivehi asaara, Malay acar, Creole French achards, Afrikaans atjar, and Yemeni Arabic‘ushshār, among others. Other culinary highlights of transregional allure, such as faluda, kababu (i.e., kabāb), kabuli, pilau and the aforementioned sambusa, have also found their way into Swahili cuisine.

Most of these historically connected words have diverged semantically over time, with dishes in the diaspora often differing significantly from what is known by the same name in the “motherland.” Some inherited recipes have blended with the cooking style of the recipient society, creating a “fusion” cuisine avant la lettre. It is equally possible that more archaic versions of a certain dish have disappeared everywhere but in the diaspora. A case in point is the aforementioned side-dish sambal, a spicy condiment inseparable from Malay or Indonesian meals. Across the archipelago, chili peppers—originally from the New World—constitute the default ingredient of sambal; other ingredients depend on the region and on the specific type of sambal being prepared. Chilies are less prominent or even absent in the earliest exported versions of the dish. Among the Jaffna Tamils in northern Sri Lanka, campāl is similar to South Asian chutney and often contains grated coconut,Footnote 92 whereas the Sinhalese version can be made with coconut (pol sambōl), caramelised onion (sīni sambōl), or dried fish (kaṭṭa sambōl). Macau has its “eggplant sambal” (sambal de bringella), which is a sautéed dish without chili.Footnote 93 In the Ḥaḍramawt region, ṣanbal is the word used for “fried vegetable (with shrimps).” To the Cape Muslims, sambal is “usually a highly seasoned relish of grated raw fruits or vegetables, squeezed dry, mixed with pounded chili, and moistened with vinegar or lemon juice for a sweet-sour taste.”Footnote 94 Back in Indonesia, raw or sautéed vegetables are no longer central to sambal, yet the Balinese “raw sambal” (sambal matah) reflects this earlier tradition.

Besides the names of dishes, it is noteworthy that the dining traditions across the Indian Ocean come with similar names for dishware (Table 6).

Table 6 Dishware across the Indian Ocean

If Asian cooks and the dishes they prepared already fell beyond the scope of most (European) commenters, people belonging to the underclasses of colonial cities effectively inhabited an alternate universe. At the same time, we cannot hope for anything but a rudimentary understanding of interethnic contact without recognising its profane elements. The final section, therefore, calls attention to lexical borrowing in criminal or otherwise undesirable slang. While the relevant words rarely made it into high literature or dictionaries, they speak volumes about the full breadth of interaction between peoples and languages on the margins.

Rogues, Prostitutes, and Undesirables

Vulgar or subversive expressions of language can provide unique insights into the daily politics of urban centres,Footnote 97 yet remain an underexplored topic. Nevertheless, swearing in particular should be seen as crucial to the study of cultural contact; not incidentally it ranks among the first things fresh language learners tend to specialise in. Like sexual and criminal slang, swearwords fall within the realm of expletive language and as such need to be replaced regularly in order to maintain their expressive power. Languages in contact tend therefore to be fruitful sources of inspiration to insult people innovatively, and the ports of the Indian Ocean form no exception to this generalisation.

The remarkable mobility of swearwords explains why, for example, the Malay invective puki “female genitals” found its way into Sinhala, Dhivehi, and Malagasy (Mayotte dial.) as pukkī, fui, and pòky respectively.Footnote 98 Travelling in the opposite direction is nineteenth-century Malay bancut, glossed in a nineteenth-century dictionary as a “whore’s child” (hoerekind),Footnote 99 yet in fact reflecting the Hindustani swearword bahancod “sisterfucker.” This common term of abuse also entered the Anglo-Indian lexicon as banchoot, which—as the compilers of a famous Anglo-Indian dictionary warn us with no shortage of Victorian prudishness—occupies a class of words “we should hesitate to print if their odious meaning were not obscure ‘to the general.’ If it were known to the Englishmen who sometimes use the words, we believe there are few who would not shrink from such brutality.”Footnote 100 In reality, as a nineteenth-century Laskarī dictionary informs us, it was hardly uncommon for sailors “heaving up” the anchor to endure it as part of a broader repertoire of obscenities unleashed by their superiors: Habes sālā! Bahancod habes! Habes ḥarāmzāda! Footnote 101 The infamous swearing habits of the lascars were noted not only by prim and proper British commenters, but also, for example, by the Persian traveller Abū Ṭālib Khān. In his early nineteenth-century autobiographical Masīr-e T̤ālibī, he complained precisely about their abusive language while heaving the anchor.Footnote 102

Predictably, such colourful curses proved prone to imitation in broader circles. The abovementioned Laskarī swearword ḥarāmzāda “bastard”—of Hindustani and ultimately Persian origins—regularly features in classical Malay texts (haramzadah). Equally common in literary Malay are the loan-insults bodoh “stupid,” candal “immoral,” nakal “mischievous,” and bisi “indecent; shameless,” respectively from Hindustani buddhū “idiot,” canḍāl “an outcast,” Tamil nakkal “mockery,” and vēci “courtesan; whore.” A renowned Malay dictionary further lists sur and tahi-uli as terms of abuse.Footnote 103 I suspect the former is from Panjabi sṹr “pig” and the latter from Tamil tāyōḻi “motherfucker,” which also made its way into eighteenth-century Afrikaans—presumably through (Cape) Malay—as tajolie.Footnote 104 Other profanities did not even make it into the dictionaries. From personal knowledge, I can say that the Malay slang of West Malaysia exhibits the insults conek “penis,” pundek “vagina,” and kamjat “lowbred,” respectively from Tamil cuṇṇi, puṇṭai, and Hindustani kamzāt.

In Penang, one of the British Straits Settlements, both Hindustani and Tamil left their imprint on the local Malay dialect. From 1790 to 1873 the island was used as a settlement for transported Indian convicts, many of whom became part of its general population after serving their sentence.Footnote 105 Penang’s origins as a penal destination thus left a distinct imprint on the city’s linguistic landscape, which displayed a decidedly Indian character before Chinese settlers eventually outnumbered them from the late nineteenth century. By that time, a local variety of Hokkien—a southern Chinese language—gradually became the city’s dominant mother tongue, obscuring the prior existence of a heavily Indianised Malay dialect.Footnote 106 Some of its archaic words seem to go back to Hindustani:Footnote 107 lucah “shameless, indecent,” gabar “boastful, arrogant,” gabra “scared, confused,” and kacera “rubbish” come from luccā, gabbar, ghābrā, and kacrā.Footnote 108 These idioms indubitably reflect the historical presence on the island of convicts (Malay: banduan, from Hindustani bandhuvā) from the Indian subcontinent. This is further supported by contemporaneous Straits Malay terms such as argari “hand-cuffs” from Hindustani hath-kaṛī, and kanjus “cell in police station; lock-up,” either from Hindustani kāñjī-hauz or directly from Anglo-Indian “congee-house”—named after the regimen of rice-gruel (Hindustani: kāñjī) fed to those unfortunate enough to end up inside. Of considerably more gastronomic sophistication, it should be added, are the many North and South Indian dishes that flavour Penang’s culinary landscape into the present.Footnote 109

In the arena of prostitution, too, the Penang Malay dialect reveals now-erased influence from the Indian subcontinent. From the late nineteenth century, prostitution in this city was controlled by Chinese and Japanese syndicates,Footnote 110 but South Asians seem to have played a significant role in earlier times. For instance, the word for “brothel” was cakela (Hindustani: caklā), while a “pimp” was known either as barua (Hindustani: bhaṛuā) or kuteni (Hindustani: kuṭnī “procuress”). This marks a significant contrast with the Netherlands Indies, where much of the terminology surrounding prostitution came from Hokkien. In contemporaneous Malay literature published in Java, hence, we find suhian “brothel,” bah-tao “procuress,” and cabo “prostitute,” respectively from su-hian (私軒), bâ-thâu (媌頭), and cha-bó· (查某).Footnote 111

This excursus to Penang is but one example of the trajectories of unrefined or marginalised language across the multiethnic ports encircling the Indian Ocean. I will not attempt here to go beyond the Malay World—for example to Zanzibar, Mogadishu, Jaffna, or Rangoon—for the simple reason that I do not possess the necessary linguistic skills to discuss those locations with an equal degree (or, perhaps, assertion) of authority. Similar examples can surely be found elsewhere by scholars prepared to look for them in and beyond the sources left to us by Europe’s imperial undertakings.

Examining Lexical Connectivities

Hopefully this study has provided some inspiration for a language-centric approach to cultural contact across the Indian Ocean, in particular between non-European societies. Through its focus on lexical borrowing, it has reconstructed connections no longer obvious—or deemed relevant—at present, while corroborating better studied ones. As such, it has highlighted specific settings of cultural contact between Indian Ocean ports, without finding much reason to treat the broader Indian Ocean as a linguistically homogenised area beyond the well-known adoption of Arabic as the language of Islamic practices. Today, only a minority of people in the ports of East Africa or the Malay World would understand Hindustani, Gujarati, or other languages from the subcontinent, yet the echoes of India’s once influential lascars reverberate in obscure nautical dictionaries. Malay, too, has long ceased to be a language of significance in the Indian Ocean, yet the well-seasoned culinary heritage of Sri Lanka, Cape Town, and the Ḥaḍramawt region are testimony to Southeast Asia’s forgotten influences westwards. Maritime, sartorial, and gastronomic traditions—now perhaps replaced by more recent ones, yet preserved in the lexical and literary heritage of the Indian Ocean ports—all contain clues to the historical interdependence of ports, peoples, and products. The transregional flows discussed in this paper were facilitated by maritime communities and accepted by port-dwelling urbanites who looked to the cosmopolitan ocean rather than the rural hinterland for their sense of cultural belonging. In other ways, however, culture is only a secondary part of this story. More than anything the availability of new garments, utensils, food items, and other commodities started off as a matter of harsh capitalism and international trade. The borrowings outlined here, then, are to be considered primarily a consequence of cross-cultural entrepreneurship and forced replacement, rather than uninhibited enthusiasm for other cultures.

Central to this study stand a series of loanwords connecting the coasts of East Africa, South Asia, and Southeast Asia. A considerable number of these lexical items turn out to be of ultimately Persian origin, even though their distribution was often carried out by South or Southeast Asians. To some extent, the connectivities outlined here also stretched beyond the Indian Ocean, marking a departure from scholarship that sees this geographical space as an integrated world. Ports just beyond its horizon—such as Cape Town in the west and Macau in the east—were significantly influenced by developments initiated in the Indian Ocean, as is clearly reflected in the culinary heritage of these cities. On the other hand, certain regions within the Indian Ocean display much less of a shared cultural vocabulary with the ports outlined in this study. This seems to be the case for Madagascar, Somalia, and Myanmar, among others, although more research on their linguistic history may challenge these generalisations; not much work has been done on the marginalised slang of these regions, especially in colonial times. These unresolved issues notwithstanding, this study has added some depth to a long line of scholarship on the importance of maritime connections and international ports for the dispersal of ideas and traditions across the Indian Ocean. Its chief novel contribution is the assertion that lexical borrowing is a powerful and effective tool to approach, quantify, and qualify these contact-induced exchanges.

Acknowledgements

This paper has benefited considerably from discussions with Louis Sicking. I am equally thankful for the input of Marina Martin during the AAS-in-ASIA conference in Kyoto, Japan (24–27 June 2016), where an early version was presented. Another profound debt of gratitude is owed to an anonymous reviewer, whose careful reading, insightful comments, meticulous corrections, and suggestions for further reading have sharpened the arguments put forward in this study significantly.