Global governance began in the mid-nineteenth century and accelerated after the First World War. But it came of age in the post-Second World War era. In response to the lessons learned from the collapse of international order between the wars, and the need to rebuild after the devastation wrought by the Second World War, states, with the USA in the lead, set out to create a new and comprehensive set of international organizations to tackle a growing list of shared global challenges. Led by legendary statesman like Harry Dexter White, John Maynard Keynes, Dean Acheson, and Jean Monnet, states collectively recognized that their joint interests in a reshaped world required new forms of interstate cooperation, coordination, and collaboration. Their lengthy negotiations often resulted in the creation of a big and sometimes powerful international institution, anchored by a comprehensive treaty, and with aspirations to global and even universal membership. These mid-century institutions typically had large secretariats housed in imposing buildings in New York, Washington, or Geneva. States remained very much in control, bureaucracies were expected to use their authority and expertise to carry out the decisions made by states, and their growing size and scale meant that these new international organizations (IOs) had a global reach. States and their IOs created and regulated global governance in this era on a scale and with a scope that had not been seen before.

There remain plenty of examples of this postwar modernism, with states and IOs standing at the center of ambitious efforts to address global challenges. But scholars are increasingly using different language, discourse, and imagery to try and capture what they now see, some seventy-five years later, as a much more complex system of global governance.Footnote 1 Exactly how to describe these developments is a matter of debate – and competition. Westphalian global governance has given way to one that is post-Westphalian.Footnote 2 The modern has succumbed to the post-modern.Footnote 3 Good-bye old multilateralism; hello new multilateralism.Footnote 4 We are now in a Copernican world.Footnote 5 Global governance is now orchestrated.Footnote 6 There has been an increase in delegated authority.Footnote 7 But not all authority is delegated. Because of world-historical processes, authority has become more fragmented and dispersed across the globe, enabling new kinds of actors to have a voice.Footnote 8 We have now entered an era of partnerships and “multistakeholderism.”Footnote 9 Global governance is best seen as “networked.”Footnote 10 Some talk about clubs.Footnote 11 Others discuss the “layering” of global governance.Footnote 12 Maybe global governance is less layered and more multilevel.Footnote 13 Layering and multilevel suggest that there is fixed arrangement, while those who work with regime complexity suggest the existence of a much less stable and predictable order.Footnote 14 An even messier possibility is that the new governance arrangements have all the characteristics, and perhaps even entropy, of a spaghetti bowl.Footnote 15 In short, there is widespread agreement that something fundamental in the form and structure of governance has changed, but there are competing views on exactly what has changed – and how. What is clear is that global governance has become much more diverse and complex. States and IOs are still often the stars of the show, but they increasingly work with an ensemble cast, including non-governmental organizations (NGOs), public–private partnerships, multi-stakeholder arrangements, transnational networks, private organizations, corporations, and foundations. A good example is the Global Alliance on Vaccines, known as Gavi. The primary partners include existing global institutions (World Health Organization, World Bank) as well as foundations (the Gates Foundation), private sector organizations (the International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Association), and governments.

Alongside this change in the kinds of actors there has also been a change in the relationship between them. States and IOs used to be the major players, and sometimes the only players, but increasingly they govern with others. This suggests that there are new patterns of inclusion. But inclusion does not mean equality and inclusion often creates some with more and others with lesser authority and those who still remain excluded altogether. Additionally, these actors conduct their relations in different kinds of spaces. Previous governance arrangements used to be formed by treaties and often overseen by secretariats in buildings. Now they can be quite informal and have the barest sort of physical presence.

Are these changes good or bad for addressing the world’s problems? Each position has its defenders. More actors might mean more kinds of knowledge and the ability to benefit from the wisdom of diverse views; or it may mean more veto players and more opportunities to drive outcomes to the lowest common denominator. Change may reflect a rational, functional adaptation. In this view the old forms of governance, while perhaps appropriate for the twentieth century, are insufficient for the current age; the new forms of governance better reflect the demands of the twenty-first century. In short, because the world is messier, denser, more tightly coupled, and more interconnected it naturally requires a global governance that is subtler, fluid, and pluralistic.Footnote 16 It is becoming “fit for purpose.” But global governance does not necessarily rationally adapt – form does not necessarily follow function, supply does not necessarily follow demand, and efficacy often outweighs efficiency. These less than functional, perhaps dysfunctional, outcomes are often attributed to politics and power; states and other actors are often more interested in defending and advancing their own short-term interests than they are in solving collective problems.

These new governance mechanisms may also reflect and produce much less ambition and vision. The global organizations created after 1945 had far-reaching goals and attempted to establish rules that would regulate an entire issue area. The World Bank took on the challenge of creating development, and later fighting poverty in the Global South. The International Monetary Fund would handle issues related to international financial stability. The United Nations (UN) and its specialized agencies covered an array of large global public goods, from refugees to education, not to mention policing international conflict via the Security Council. The European Coal and Steel Community’s rather dull name betrayed a rather far-reaching agenda that included creating the basis for greater economic openness and regional security in an area decimated by two recent total wars. These were broad and deep agendas.

Global governance in the twenty-first century has become much less ambitious, characterized by provisional and improvisational action, piecemeal incrementalism, more modest goals, and experimentalism. Perhaps these more modest approaches will eventually provide the foundation for a more ambitious undertaking. Yet while these scaled-back ambitions might deliver more identifiable “successes,” they might not sum to a solution. More agreements between municipalities on reducing carbon emissions might be welcome, but would not be enough to meaningfully combat climate change. Amid the 2019–2020 Covid-19 global health pandemic Dr. Michele Barry, director of the Center for Innovation in Global Health at Stanford University, lamented:

But one of the things about epidemics is it’s really important to have what I call shared global governance. And I don’t think in this world it’s great that we don’t have a stronger central governance of our world health. We have a World Health Organization that has a budget that is less than many of our hospitals in the United States.Footnote 17

This volume is an intervention in the debate about the evolving architecture of global governance. The chapters herein reassess what is happening, why it is happening, and what effects ensue. We understand global governance to be the institutional arrangements used to identify problems, facilitate decision-making, and promote rule-based behavior on a global scale. Scholars of global governance agree that it has changed, and usually focus on the number and kinds of actors now involved. By these measures there is no disputing the change. We approach the question of change from a somewhat different vantage point, one that we think offers a superior way of getting to the core issue: how do these new architectures reflect the changing relations between the actors involved in global governance? In order to better understand whether and how relations among the now myriad key actors have changed we use the lens of modes of governance.

We focus our analysis on three ideal-typical modes drawn from economic and sociological institutionalism: hierarchy, network, and market.Footnote 18 While we go on to say more about these modes, the core distinction revolves around how rules are produced, sustained, and enforced. Hierarchical modes are characterized by top-down, centralized, organizational forms that regulate relations between relatively dependent actors and enforce the rules through command and force. The traditional IO is a classic example of a hierarchical mode of global governance. Market modes are organized around non-hierarchical principles that regulate relatively independent actors, often associated with a “hidden hand” or competition among independent actors. Whereas hierarchies are centralized, markets are decentralized. Network modes are characterized by relatively interdependent (and possibly formally) equal actors with a common purpose that voluntarily negotiate their rules through bargaining and persuasion and then maintain and enforce those rules through mechanisms of trust. Although scholars might disagree on what a networked world means, many nevertheless seem to agree that it exists.

In broad terms the existing literature on global governance tends to claim, often implicitly, that hierarchical modes of governance such as traditional IOs are losing their prominence, and networks and market modes are increasingly prevalent and significant.Footnote 19 This is the basic description we began this chapter with. However, we challenge this claim for two reasons.

First, while this view captures an important truth it is not the whole truth. As the chapters illustrate, there are areas of global governance in which this has occurred and is occurring, but there are others where it has not. In short, there is heterogeneity across issue areas. Furthermore, changes between these ideal-typical forms may take a variety of pathways. Some are linear, others not. Some occur quickly, others over decades. Some are permanent transitions, others reverse or follow yet another path. Some paths taken in one period will increase the likelihood of others in the future.

Second, even where there has been a shift from hierarchies to markets and networks the former remain alive and well, even if less visible. We argue that there is a significant “shadow of hierarchy” in many areas of global governance. Just as economic markets cannot operate without legally enforced property rights protections, global networks and market-driven governance typically require rules that have some modicum of support from states. Although we use these three modes to mark change in global governance, this volume emphasizes how they intersect and combine in complex and interesting ways.

This volume also looks to the underlying causes, or drivers, of these shifting modes of global governance. We identify nine major drivers of change that are present to one degree or another, all of which reside at the structural level: (1) geopolitical change, such as the relative decline of US power and rise of China; (2) shifts in the global economy; the sheer “crowding” in the global governance space, both in terms of (3) the number of actors and (4) the pluralization of actors; (5) the increasing complexity of global problems; (6) changes in ideology and trends in governance theory; (7) the global turn to expertise as a way to rationalize governance; (8) technological change; and (9) domestic political change, for example in the form of rising populism and nationalism.

This is a rather lengthy list of drivers, and all along we aspired to reduce it to the fingers on one hand – but the history of global governance would not play along. At this point the chapters provide no grounds for removing any from consideration. Also, these drivers also are not independent but rather interdependent. For instance, technological change has enabled the rise of non-state actors in global governance. Moreover, there also might be other factors, such as legitimacy, as suggested by Jonas Tallberg in Chapter 11 and Michael Zürn in his work, or growing legalization, that also deserve independent status and can alter the path of these drivers.Footnote 20 Lastly, structures can impose but actors choose, even if not necessarily under the conditions of their choosing. The history of global governance illustrates this point over and over again. There are underlying forces that help us sort through some of the important patterns in global governance, but there also are state and non-state actors, and more of them in different kinds of relationships, that create a space for creativity and agency. However convenient it might be to reduce the world to structure, the world rarely abides.

We are interested in the shifting modes of governance not only because they provide a different way of thinking about patterns and trends in global governance but also because of their material and normative consequences. The demand for change in global governance is often driven by the desire to solve major global problems. Accordingly, the major measure of outcome is effectiveness – and many of the chapters understandably make this a major concern, even if they are unable to provide airtight assessments one way or another. But in many instances they note how a mode of governance is judged not only on material gains but also on normative evaluations. At such moments they raise issues of legitimacy, fairness, justice, accountability, and other normative scales. And these normative measures refer not only to distributional outcomes but also to process and whether those who are affected by the decisions have a voice in shaping them.

The remainder of the Introduction is organized as follows. This first section lays out how scholars have tended to mark transformation and presents our alternative. Specifically, our view is that the transformations many have documented are better understood not in terms of changes in actors but rather changes in relations among actors. Consequently, we examine the modes of global governance in terms of hierarchy, markets, and networks, which almost always involves a change in actors. The second section reviews the various forces behind the change, ties these individual arguments to shifts in the modes of governance, insists on looking for multiple and interacting causes, and emphasizes the necessity of examining both structures and preferences. The third section addresses what is at stake in this debate. The fourth section provides an overview of the remaining chapters in this book.

Global Governance Today

Students of global governance have used various markers of transformation, but many if not most note the often dramatic shifts in the number and kinds of actors that are involved in governing the world – at times a kind of Cambrian explosion compared to the initial postwar approach. Because there is no official “census” of “global governors” it is impossible to offer decisive evidence of demographic change.Footnote 21 However, the available data suggest that there has been a major quantitative and qualitative change.

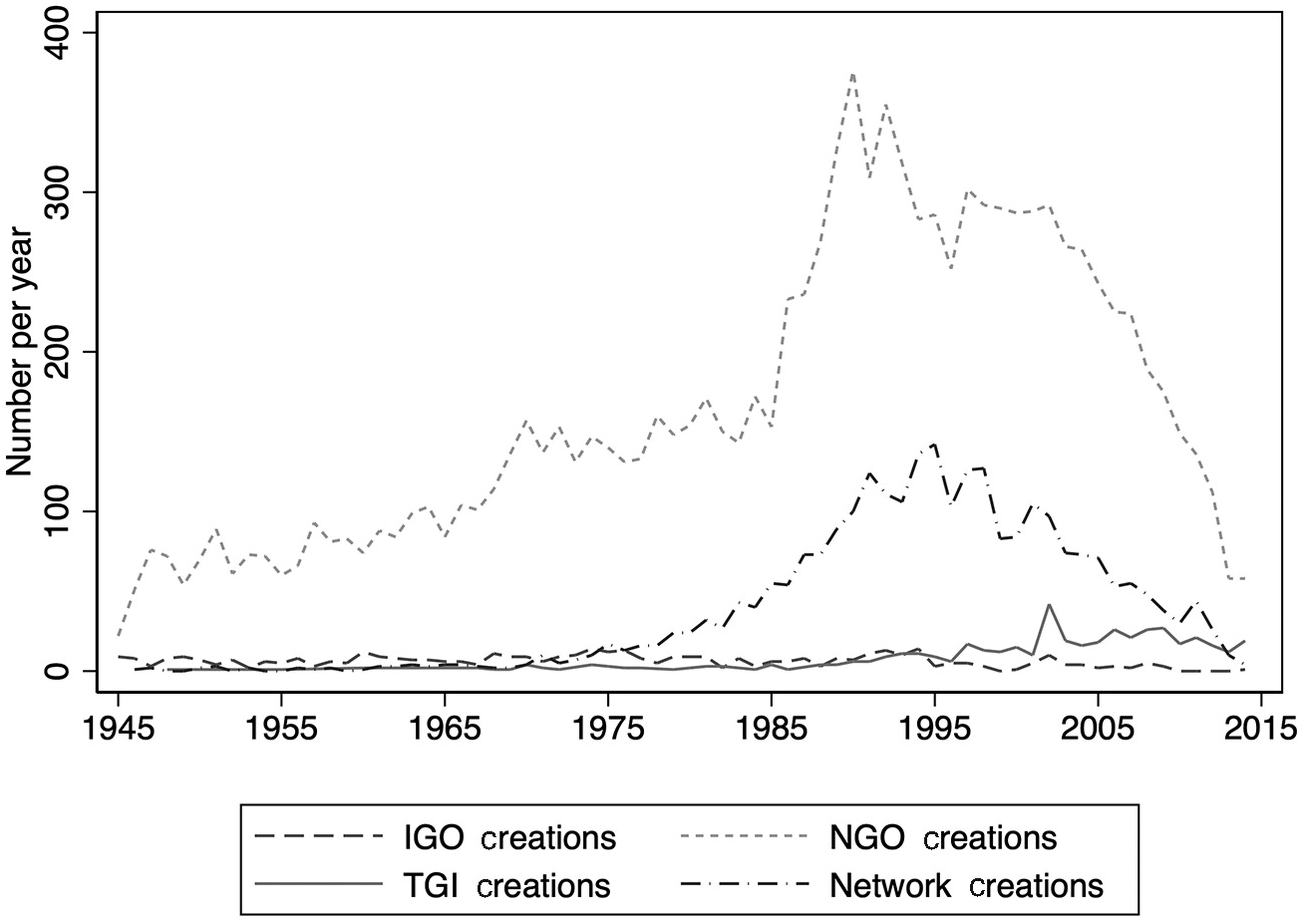

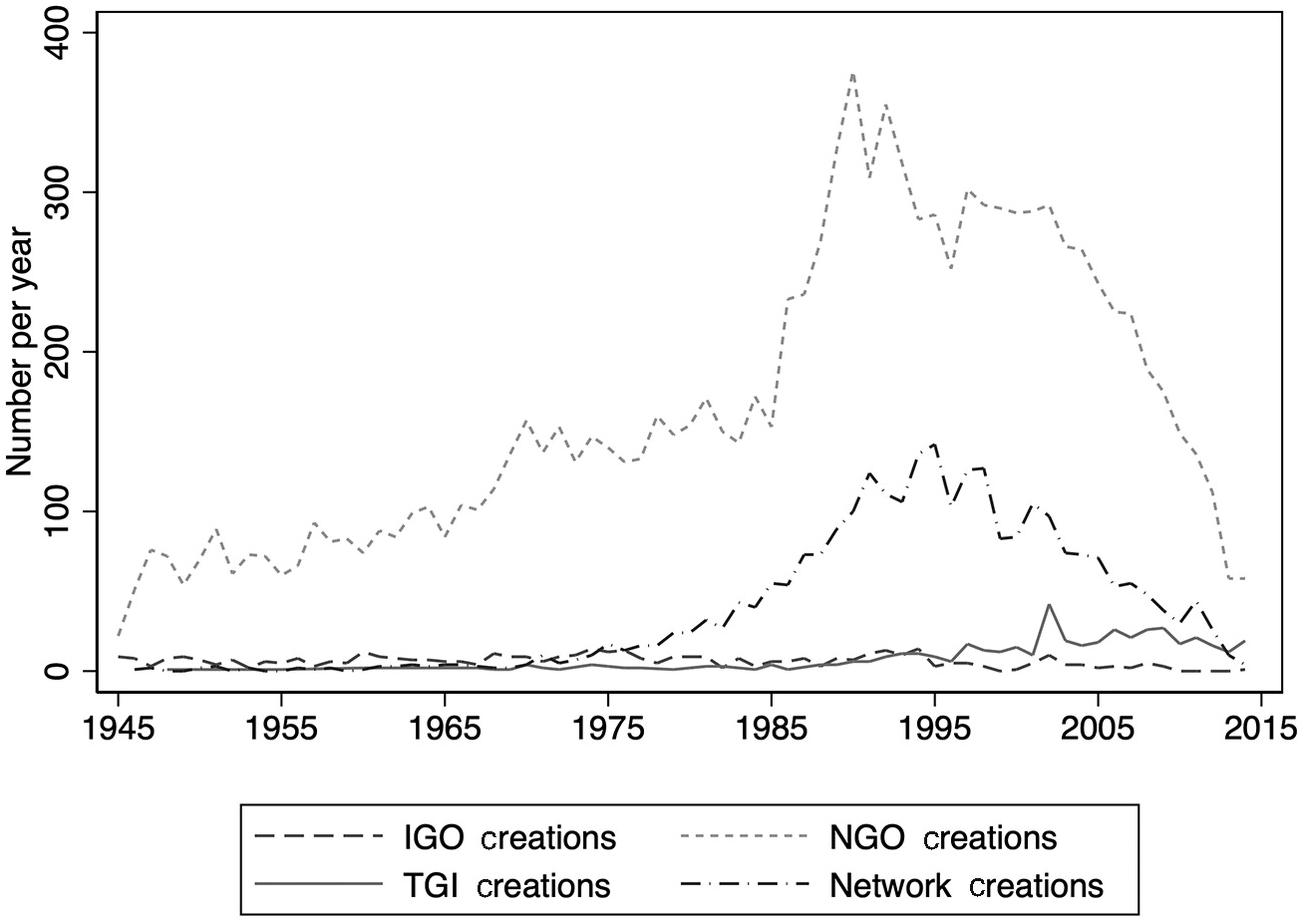

Figure I.1 graphs the changing number of IOs, NGOs, networks, and transgovernmental initiatives over time. The data provide a reasonable approximation of their comparative numbers, but the population figures have to be taken as suggestive rather than definitive.

The overall story is that while states and IOs remain central to most governance relationships, they increasingly share space with other non-state actors.

We have an accurate count of the number of states, and we know that this number has increased several-fold since 1945. We have a reasonable approximation of the relative change in the number of IOs: their numbers grew substantially after the Second World War, and then again after the end of the Cold War, but have plateaued since then. Data on IO creation paints a comparable picture, which tells us that if the population of IOs has plateaued it is due not only to death rates but also birth rates. IOs are going through their own demographic transition.Footnote 22

Although such counts tell us about the numbers of IOs they do not quite capture the variation in IOs in terms of their inclusion of non-state actors. One minimalist definition of an IO is a permanent collaborative arrangement established by three of more states, but the members of an IO can also include other IOs, NGOs, and other private actors. It has become commonplace to note that the participants in global governance have diversified – not only as formal members, but also as informal participants in a range of decision-making and discussion forums. In particular, a wide array of studies has pointed to the varied ways in which NGOs and other non-state actors are participating in global governance.Footnote 23

The data on NGOs support this view.Footnote 24 There are more NGOs than ever before, playing various roles – from shaping the agenda, to negotiating agreements, to monitoring rates of compliance by states with those agreements.Footnote 25 There also are more networks than ever before. There is no best way to tally the number of networks, in part because there is no consensus definition on what is a network. Assuming that self-identification – do actors see themselves as part of a network? – provides at least a reasonable first cut, there are far more networks than ever before. As shown in Figure I.1, self-described networks significantly increased in the mid-1970s, but the rate of increase has leveled off in recent years.Footnote 26 This strikingly large increase can be read as consistent with the argument that traditional forms of global governance are in decline – with the decline of more formal IOs in the issue area, networks rise to fill “global governance” gaps. Alternatively, it can be read as consistent with the claim that traditional hierarchical IOs are stable, but increasingly inclusive and open in their operation. In other words, perhaps traditional IOs and networks are complements, not substitutes. This line of argument, addressed in some of the chapters, suggests a denser and more complex array of institutions and actors.Footnote 27 In addition to networks there are other kinds of groupings, formal and informal, that are increasingly being recognized. Public–private partnerships have grown in significance and number, although as seen in Figure I.1 (where they are measured as transgovernmental initiatives (TGIs)) their numbers do not yet rival that of self-identified networks or NGOs.Footnote 28 Corporations have always had an important impact on global governance, but they too are increasingly visible.Footnote 29 Municipalities and “nation cities” are also more active today, often because they are frustrated by the inaction of states.Footnote 30

Expert communities, originally referred to by social scientists as epistemic communities,Footnote 31 are also not new, but scholars have become more aware of the multiple functions they perform. These and other associations of private actors have many informal roles. But most strikingly they have increasingly received formal roles – as full-blown members of public–private partnerships; as (perhaps nonvoting) participants in more traditional IOs; as advisors to state delegations; and as interlocutors in a range of multilateral bodies, many of which have adopted rules that allow for private actors to participate in a range of discussions and debates.

We can learn a lot from a census of global governance, but it cannot address whether there has been a change in its very organization.Footnote 32 A rise in the number of NGOs in and of itself tells us little unless it is embedded in an understanding of whether and how this has affected the mechanisms of global governance. Our elevation of relations over numbers is consistent with our earlier (and others’) definition of global governance – how institutionalized rule systems coordinate actors. And it provides the justification for the concept we use to capture the different ways that societies can organize social relations: modes of governance.

Modes of governance can be distinguished according to various criteria, but in the interest of parsimony and comparison we highlight the primary mechanism used to coordinate social action. Following sociological and economic institutionalists we identify three modes: hierarchies, in which social action is organized through regulation and law that demand some kinds of action and prohibit others; markets, in which decentralized institutions such as markets provide costs and benefits for different actions; and networks, in which independent, purposive actors negotiate the rules that will regulate their relations.

Because we treat hierarchical, market, and network modes of governance as ideal types, we must recite a few common words regarding the conceptual and methodological advantages and limits of ideal-typical analysis.Footnote 33 To begin with, ideal types are the attributes associated with a social phenomenon in its purity. Observers often disagree about what these attributes are. For instance, Max Weber’s concept of the state has been turned into an ideal type, but his is not the only formulation, for there are rival Marxian and liberal alternatives. Furthermore, types are often decomposed into subtypes, and the justification for doing so is because it provides a more useful, granular concept for comparison within the ideal type. For instance, scholars that draw from Weber’s ideal type of the state often subdivide it into weak and strong variants. These subtypes should have distinctive attributes. For instance, the attributes associated with weak states should not also define strong states. Moreover, these types and subtypes provide the basis for comparison across cases and over time. We can use the ideal types of strong and weak states to provide meaningful comparisons between the USA and Argentina at a moment in time, and also to measure historical changes in state power in the United States. Lastly, there is no assumption that any existing case will map perfectly onto an ideal type; in fact, the assumption is that such ideal types do not exist concretely. Ideal types are purified abstractions and the real world is filled with muddy complications. The USA is a strong state in some ways and a weak state in others.

This outline of ideal-typical analysis guides our use of modes of governance. Modes of governance concern how societies organize social relations.Footnote 34 Although there are various ways in which these three ideal types can be distinguished from each other, we focus on the mechanisms that organize and pattern their actions. Hierarchies are organized around command and control, markets on decentralized institutions that produce incentives for action by independent actors, and networks on negotiated agreements between purposeful actors. These different modes of governance provide the basis for analysis across instances and history. Has there been a change in the social organization of trade, emergency relief, pandemics, carbon emissions, or small arms? We can use these ideal types to make comparisons across these different issue areas, for example to claim that small arms is more networked while trade is largely hierarchical. We also can use these ideal types for historical analysis, for example to claim that the direction of global governance has moved from hierarchical to markets and networks, or that a single issue-area like humanitarianism has become less networked and more hierarchical. The chapters also blaze the warning that actual examples of global governance will not map perfectly onto any of the three modes of governance. Instead there is considerable overlap, blending, and layering between two or more modes. That said, these ideal types provide a common basis for judging whether and how there has been a change in the dominant mode of governance.

Although the concept of modes of governance is intended to be general enough to be applicable to almost any social setting, heretofore much of the literature deploying these modes has focused on domestic governance. International relations scholars will be quick to point out the key difference between domestic and global governance: whereas the former is defined by hierarchy because of the presence of a state, the latter is defined by anarchy because of the absence of a supranational authority. A Waltzian view might add that the absence of hierarchy does not mean that governance is organized around anarchy, but rather that states can be likened to firms and their relations are akin to firms in markets.Footnote 35 The literatures on global governance and hierarchy suggest that the absence of a supranational authority does not mean the absence of hierarchy in governance. In fact, one of the interesting parallels between the literature on domestic and global governance is that each, for different reasons, have observed a change from hierarchies to markets and networks.

In what follows we define the three modes in greater detail. Hierarchical modes are characterized by top-down, centralized, organizational forms. Or, as Herbert Simon put it, “[I]n a hierarchic formal organization, each system consists of a ‘boss’ and a set of subordinate subsystems.”Footnote 36 The state, the bureaucracy, and the military are the prototypical forms of hierarchical organization. The state has the authority, legitimacy, and coercive power to issue commands and laws and expect them to be followed – or else. The bureaucracy is characterized by a head that can issue orders to subordinates with the expectation that they will be implemented. The military operates with a chain of command and can punish for failure to obey.

Two critical wrinkles must be addressed when discussing hierarchical modes of global governance. To retrace our earlier steps, the first is whether it is even warranted to consider hierarchy in a world of sovereign states. Although the concept of the modes of governance has not been widely applied to global governance, there is a substantial literature on EU governance which accepts that hierarchies can exist.Footnote 37 One advantage that EU governance has over global governance more broadly for making claims about the existence of hierarchy is the presence of law and tight linkages between the domestic and the regional. But none of our cases of hierarchy are built around such conditions. Instead they point to two alternative forms of hierarchy. One is hegemonic or imperial arrangements. The other is IOs, which is where many rules are debated, legislated, implemented, and (sometimes) enforced. The objection to considering IOs as a form of hierarchy is that they rely on borrowed authority. Simply put, (a limited number of) states stand behind IOs and keep them on a short leash. But there are four justifications for treating IOs as a form of hierarchy: they operate on delegated state authority; they regulate through norms and soft and hard law that impose rules on states and others; they are organized around the bureaucratic form; and they often have (or work to create) considerable discretion and even the authority to make nearly unilateral decisions that shape social action.Footnote 38

The second and related wrinkle regards the distinction between formal and informal arrangements. IOs are formalized arrangements, which are most of the cases in the volume, but there are two cases in this volume of informal hierarchies. In Chapter 2 Kahler points to the interesting case of cartels, which exist when a small number of actors create an agreement that regulates the actions of others for private and public interests. Cartels are informal (though often quite visible) because they are not typically created through a legal agreement. Consequently they do not regulate in a heavy-handed way but rather, in his case of trade, use softer rules and prices to do so. Barnett uses the concept of a club to capture how a set of states, IOs, and nongovernmental organizations create a set of rules and norms among themselves that are then intended to regulate the broader network of humanitarian governance. And beyond the two cases of informal hierarchy in this volume a growing number of scholars now point to the power of informal organizations, possessing many of the characteristics one would come to expect of traditional hierarchies.Footnote 39

Market modes of governance are organized around non-hierarchical principles, often associated with a “hidden hand” that steers action through incentives. Hierarchies command; markets incentivize. Central to the market is price, which contains information about costs and benefits and creates incentives and disincentives for different actions. There is no need for a regulator to command the merchant to lower the price because the market communicates what to do. One of the distinct advantages of markets, therefore, is that they are efficient; a “hidden hand” is cheaper than law and machinery to enforce the rules. Yet, under some conditions, especially when transaction costs are high, hierarchy can be even more efficient. This is one reason firms exist.Footnote 40 Furthermore, markets require some form of hierarchy – usually in the form of law, property rights, and courts – to function.

Market modes of global governance are quite common. One of the most famous uses of markets for governance is cap and trade in the area of climate governance (as discussed by Green in Chapter 3); in this instance there was no existing market for CO2 emissions – it was created specifically for the purpose of trying to reduce its level. Similarly, in Chapter 10 Andonova outlines efforts by private firms using market mechanisms in the area of clean energy. Various NGOs want to regulate firms through certification measures, such as fair trade or the living wage; in doing so they create incentives for firms to alter their behavior to conform with international norms. Other examples of market modes of governance include benchmarking and rating systems, which can cause actors to change their behavior to maintain or elevate their reputation, thereby altering their stream of benefits.Footnote 41 Some of the most interesting innovations in global governance, such as forest certification, are built on the logic of markets.Footnote 42

Network modes consist of a “set of actors, or nodes, along with a specific set of relations that connect them.”Footnote 43 In this broad definition, markets and hierarchies also can count as networks – the former have enduring ties and the latter are tied formally. We follow those scholars and practitioners that use the concept of network to capture not the fact of ongoing exchange but rather the quality of the exchange and how governance is produced.

Specifically, networks have the following characteristics. The actors that form a network are interdependent, in contrast to hierarchies (defined by dependence) and markets (defined by independence). There is a common purpose or interest among the actors. There is relative and formal equality between the participants. They create agreements that are voluntary or quasi-voluntary, are negotiated with little or no coercion and are freely entered into. Disputes and differences of opinion are arbitrated and resolved through negotiation and persuasion.Footnote 44 Because of the voluntary, interdependent nature of the exchange, and the absence of any enforcement mechanism, trust is central for producing order.Footnote 45

There has been a visible rise of networks in global governance.Footnote 46 There are human rights networks, in which various NGOs and other non-state actors collaborate to create, monitor, and enforce human rights. Networks are credited with helping to put and keep climate change on the global agenda. In Chapter 9 on the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) Bernard and Quintin argue that a coalition of networks, led by the ICRC, working in conjunction with a select number of allied states, shaped the regulation of armed conflict – including banning landmines.Footnote 47

By conceptualizing the transformation of global governance through hierarchies, markets, and networks the volume addresses four central issues. The first is the considerable diversity in global governance arrangements. This is not a novel claim, but the focus on the social relations and organizing principles in this volume offers additional light on this development.Footnote 48

Second, by treating the three modes of governance as ideal types we are able to provide an assessment of change in global governance. As suggested earlier, we do not assume that these ideal types correspond exactly to what exists in empirical reality. The world is always more complicated than our models. Accordingly, our analysis is attuned not only to whether there has been a change in the mode of governance but also the changing relationship between the modes of governance, with the possibility that they might become layered, entangled, and intersecting.Footnote 49 In this way, and following on Rhodes’s observation two decades ago, “it’s the mix that matters.”Footnote 50 And indeed many of our authors, including Avant, Moon, Barnett, and Seabrooke and Sending, find that their issue area is now characterized by hybrids of our ideal types.

Third, the same issue area might exhibit different modes across different functions of governance. Conceptually speaking, effective governance requires several core functions, including: the identification of the problem to be governed; the creation of a forum where parties can negotiate and legitimate the rules; a body (however skeletal) that implements and interprets the rules; the monitoring of compliance with the rules; and enforcement. Theoretically speaking, different modes of governance can coexist in these different functions in a single field. For instance, hierarchies might be important for problem definition and normative legitimation, but networks for monitoring. For example, in Chapter 4 Mueller and Pevehouse argue that hierarchical arrangements still dominate rule-making in trade, but that networks have become more common in compliance monitoring.

The fourth is the “shadow of hierarchy.”Footnote 51 The claim is critical: even when markets and networks appear to dominate there is almost always a hierarchy casting a shadow and doing important work.Footnote 52 Or said otherwise, it is possible to imagine hierarchies without markets and networks, but nearly impossible to imagine networks and markets operating effectively without some form of hierarchy. Even the austere Austrian school of economics, led by Friedrich Hayek, had difficulty conceptualizing a stable, globalizing market without international law (and courts) standing behind it.Footnote 53 Summarizing the literature on economic governance, Robert Jessop similarly observes “meta-governance”:

Political authorities (at national and other levels) are more involved in organizing the self-organization of partnerships, networks, and governance regimes. They provide the ground rules for governance; ensure the compatibility of different governance mechanisms and regimes; deploy a relative monopoly of organizational intelligence and information with which to shape cognitive expectations; act as a “court of appeal” for disputes arising within and other governance; seek to rebalance power differentials by strengthening weaker forces of systems in the interest of system integration and/or social cohesion; try to modify the self-understandings of identities, strategic capacities and interests of individual and collective actors in different strategic contexts and hence alter their implications for governance failure. This emerging meta-governance role … take[s] place “in the shadow of hierarchy.”Footnote 54

But what counts as the shadow of hierarchy? In market and network modes of governance the shadow is often quite latent, such as the existence of property rights and law that allow these modes to function. But it can become much more present and much less shadow-like when there are trends that threaten the continued pattern of regulation.Footnote 55 In situations of domestic governance it is the state that provides that shadow, looming over networks and markets armed with coercive and legal tools of enforcement. In global governance this “backstop” is often the function of powerful states working on their own or through IOs. In this vein, Barnett argues that while the humanitarian sector has network-like attributes, IOs and the states that fund them can use their funding (and the threat of its withdrawal) to bring aid agencies into line.

Explaining the Transformation

We use modes of governance to measure change. For the purposes of simplicity and clarity we consider adaptive change to be slight alterations in a particular mode of governance and transformational change to be a salient shift from one mode to another. Most of the chapters document transformations, but of varying magnitude. Manulak and Snidal, focusing on the supply side of global governance, observe a modest but significant shift from formal hierarchies to informal hierarchies plus networks. Andonova chronicles an energy field that was largely dominated by a few major states to a much more complex and networked system of governance. Moon traces global health governance that seems to move from hierarchy to networks to a modest return to hierarchy. Seabrooke and Sending observe the rise of a transnational expert network on post-conflict reconstruction in the midst of a presumed UN hierarchy. Avant compares two different areas of security: in the area of small arms it remains lightly regulated and has the characteristics of a market, whereas in the realm of private security it has moved from market to hierarchy. Green argues that climate governance has become more reliant on markets and networks.

In other areas, though, change has been muted. Kahler argues that economic governance has been relatively hierarchical over the decades, though the form of hierarchy has changed from cartel to regimes and beyond. Mueller and Pevehouse also note the continuity of hierarchy in trade, though with the important qualifier of a shift from global to regional hierarchies. Bernard and Quintin argue that despite many wars and changes in the international order the ICRC remains at the center of a hybrid form of governance that combines hierarchies and networks. And Barnett argues that emergency relief has evolved from a disorganized and disjointed sector to have hierarchy-like characteristics in a club of Western-based actors, and proven quite adept at fighting off any push to make the club more inclusive.

Our nine drivers described later in this section (geopolitics, global economics, technological change, a rise in the number of actors, a pluralization of the kinds of actors, low-hanging fruit, ideologies of governance, global rationalization, and domestic change) account for many of the changes examined by the authors. Not all nine are equally prominent across the chapters. Instead, many of the chapters identify a primary and secondary factor. In other words, transformation is rarely the result of a master cause, but rather is a product of conjunctural causation. For example, the end of the Cold War was a great disrupter, but it alone would not have produced many of the shifts in modes of governance; instead, the end of the Cold War created space for these other factors that were already quite present.

Again, our drivers are largely structural. How states and other agents respond also plays an important role. All the chapters reference how states and non-state actors engage in strategic choice as they consider the desirability of one mode over another in the context of the structural changes we outline. There is no single environment that shapes equally all areas of global governance. Trade, security, and climate, for instance, are nested in distinct contexts, with the implication that there will be different drivers interacting in different ways. Nor will one kind of driver produce one kind of change. The most that can be said is that certain drivers will create the underlying conditions for the likelihood of change from one mode to another. For instance, new forms of technology are associated with a shift from hierarchies to markets and networks. But, as Manulak and Snidal suggest, these new forms of technology may produce only a shift from formal to informal hierarchies. Technological determinism is tempting, but power and politics usually have a say. Drivers can also shape one another. The complex interaction between drivers is found in several chapters in this volume. Avant identifies how policy gridlock in the area of security led to policy entrepreneurship, which, in turn, created opportunities for policy innovation and multi-stakeholder arrangements. Seabrooke and Sending examine rationalization and transnational expertise in the context of global ideology and geopolitical changes to produce greater reliance on networks. Green identifies shifts in great power interests and rationalizing processes that led states to consider climate change to be a technical issue and to open up new forms of governance. Kahler highlights how postwar economic and political developments led to a growing regulatory state. Andonova points to the growing intersection of different markets and spaces of governance for driving more hybrid forms of global governance.

In what follows, we examine each of the nine drivers we identify in greater detail.

Geopolitics

For many international relations theorists there is no more intuitive explanation for changes in global governance than shifts in the distribution of power. A standard argument is that hegemony or a coalition of powerful states will create a hierarchical global governance, and that a shift in the distribution of power will lead to a shift in the pecking order of the hierarchy and the rules of governance.Footnote 56 This argument informs many discussions of contemporary global governance.

After the Second World War, the USA enjoyed an unprecedented degree of power. The USA used this power to reshape the global order and create a set of institutions that reflected its interests and its belief that multilateral institutions were the best way to promote cooperation and secure its hegemony at the lowest possible cost. Although it encountered turbulence in the 1970s, the existing global governance institutions endured because of American “go it alone” power.Footnote 57 After the end of the Cold War the USA used its relative power to help sponsor a new round of institution building, but arguably for different reasons – to slow its relative decline, spread the costs of cooperation through burden-sharing, and freeze the existing order.Footnote 58 Importantly, the USA and its allies began to turn away from hierarchies and toward both smaller groupings and multistakeholderism in part because they believed each would better preserve their power in a time of change.Footnote 59

At the same time there were rising powers in the post-Cold War world who imagined a different kind of change. The rapid rise of China and other BRICs (Brazil, Russia, and India) created considerable uncertainty regarding the future of global governance.Footnote 60 Would China be a status quo or revisionist state? Would it play by the existing rules or would it want to change the rules? Would it choose to work with the existing institutions or choose to develop its own? Although many Asian states are nervous about China’s growing power, its economic policies, including the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, are attractive at a moment when the existing institutions appear weak or strained.Footnote 61

Several of our authors note the importance of shifts in power. For Tallberg the diffusion of material power after 1945 led to increasing questions about the legitimacy of the existing order. For Green and for Mueller and Pevehouse the growing voice of the developing world brought new demands to climate governance and harder negotiations over the trade regime, respectively. For Avant the relevant geopolitical shift was the end of the Cold War – the move from a bipolar distribution of power – creating new demands for governance. Seabrooke and Sending argue that the end of the Cold War led to calls for governance in heretofore unexplored areas.

A Changing Global Economy

Global economic change is associated with some of the most important shifts in global governance.Footnote 62 Arguments about interdependence often highlight how changing patterns of trade, finance, and capital lead to changing rules of the international economic game. (Labor is rarely included in these discussions, but recent political upheavals around immigration have led to some attention.) The nearly twenty years of failures in the Doha Round of trade talks has encouraged more states to consider minilateral and bilateral trade arrangements. The changing structure of international trade with its complex supply chains and high levels of intrafirm trade have led some to question whether existing governance hierarchies should be fundamentally transformed.Footnote 63 Kahler echoes this argument, as he contends that globalization – with its attendant changes in cross-border flows – brought pressures on governance hierarchies that they were not able to withstand.

Marxist-oriented scholars take a different tack, tracing the relationship between transnational capitalism, global governance, and imperialism.Footnote 64 There are a host of arguments that link various configurations of capitalism to global governance, including how the postwar governance institutions were intended to produce a “compromise” between labor and capital that would unequally benefit the latter. Some argue that the phases of industrialization led to changes in international organization.Footnote 65 The rise of neoliberalism promoted an influential vision of how to encase the market in society.Footnote 66 The Washington Consensus became a central dimension of the policies of international financial institutions, profoundly benefiting foreign and domestic capital at the expense of the poor and marginalized.

Increase in the Number of Actors

It has become part of the conventional wisdom that the rising number of states in the international system will slow down if not clog global governance.Footnote 67 At the signing of the UN Charter in San Francisco in 1945 there were only fifty states present. Today the membership stands at 193, and the degree of difficulty is not additive but logarithmic. Because of this gridlock states often try to form smaller, more manageable groupings (which in theory could possess a hierarchical character).Footnote 68 Increasing numbers may also account for more informal and networked modes of governance.Footnote 69 But it also has led to more obstacles on the way to “yes.” It is no surprise that alongside “multi-stakeholder dialogue” phrases like “conference fatigue” and “treaty congestion” began to be widely invoked in the 1990s. In short, not only were the problems of the post-Cold War era likely harder to tackle, there were many more –and more diverse – actors that were at the table and had to be satisfied in some fashion.

Pluralization of Kinds of Actors

Does the rising diversity of the actors in global governance presage a shift in the modes of governance? While states have traditionally preferred hierarchical arrangements, other actors, such as corporations, are more likely to prefer markets, and NGOs and transnational actors are likely to prefer networks. The creation of hierarchical governance has also carried the seeds of pluralization. As states created (hierarchical) IOs this encouraged the emergence of new actors relating in different modes.Footnote 70 A variation on this theme is that the staff of IOs will create emanations (non-independent organizations) or ally with NGOs to evade their state masters.Footnote 71 Thus, the shift to more networked forms of governance could be driven (ironically) by bureaucracies attempting to reduce the shadow of hierarchy. Private and public authorities now frequently mingle, as emphasized by Andonova’s and Avant’s chapters, creating hybrid forms of governance that defy easy categorization.Footnote 72

Another nascent but profound change is that private actors, as well as substate actors, have increasingly circumvented the traditional negotiating forums and taken the lead in designing their own governance structures. As Moon notes, the Gates Foundation was instrumental in getting Gavi and the Global Fund off the ground. And a new wave of networks, often in the regulatory arena, began engaging globally without going (directly) through their foreign policy apparatus. The International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO) is one of the many transnational regulatory networks that illustrate this process.Footnote 73 IOSCO is largely standard-setting and consensus-based; the participants coordinate domestic actions but importantly coordinate principles and norms and share best practices. Thus, the rise in the number of NGOs, private actors, and public–private networks suggests a potential diffusion of authority away from the top of the hierarchy into networks and market-oriented modes.

Low-Hanging Fruit

Fruit and its height on the tree are often in the eye of the beholder, but a widely accepted observation is that negotiated agreements were easier to achieve in the early postwar years than in the later years because there were clear overlapping interests. But as the difficulties increase, the desire to find alternative governance modes increases. One scenario is that because states do not want to spend time and resources on difficult problems they delegate authority to non-state actors to solve these problems. This could be especially true in issue areas that were traditionally considered “low politics” – why spend scarce resources on issues which are viewed as unimportant or marginal? Note that the logic of these arguments are akin to an adverse selection problem: these newer, or at least later-tackled, problems typically require much more detailed coordination and compromise and agitate new sets of interest groups.

Mueller and Pevehouse note how the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) initially dealt with tariffs and trade in goods, leaving aside far touchier areas such as trade in agriculture, non-tariff barriers, services, and cultural goods. There were plenty of issues to fight over, but also a relatively clear path forward and broad consensus on goals. In short, the low-hanging fruit was there to be picked, and for many decades the harvest was good. In contrast to the first four trade rounds that lasted an average of six months, Doha has run for twenty years – and counting. Among the reasons are disagreements over intellectual property provisions (something no early GATT negotiator paid attention to) and agricultural trade (something GATT negotiators left off the table for political reasons). As Manulak and Snidal note, it is the issues that are nettlesome and not well defined that have forced changes in solution concepts in governance.

Ideologies of Governance

Ideologies of governance can be shaped by cultural expectations regarding what kinds of governance solutions are generally most efficient and appropriate. As we noted at the beginning of this chapter, modes of global governance are often said to have shifted from hierarchies to networks and markets. Changes in ideologies of governance can help explain this transformation. In the early postwar years the assumption was that governance required a strong role for the state.Footnote 74 As Kahler argues, it was this mid-century victory of the “regulatory state” that also gave rise to strong hierarchies in global governance. Beginning in the 1980s, and especially evident with the rise of neoliberalism, there was a growing belief that governance is done best and is most efficient when the state steps back. Moon notes that beliefs about efficacy help account for the shift from hierarchical to market and network modes of governance in global health. To many this represents a positive development that produces a more efficient, democratic, and effective system of governance. There is a greater interest in having business and technological sectors’ solutions applied to longstanding global problems such as poverty. The recent US assault on the existing global governance system also reflects ideologies of governance. A small government, pro-sovereignty worldview is almost necessarily anti-global governance. The Trump White House was championed by nationalists who saw globalism as a threat to the identity and interests of the USA.Footnote 75

Global Rationalization

Among the various explanations for the changes in global governance, global rationalization is the most “cultural.” Rationalization is a multilayered process that broadly refers to the movement of societies from tradition to modernity. For our purposes it underscores some features that help explain the shift toward networks. To begin with, rationalization is bound up with a new kind of authority – a rational-legal authority whose authority claims derive from being constituted by law and following sound, scientific objective reasoning. Rational-legal authority is both rational and legal. The preferred manner of making decisions is through standardized calculations that can produce more efficient and effective responses to environmental demands. Modern governance of all kinds displays this type of reasoning and authority. Additionally, legitimacy is increasingly conferred on bureaucratic principles such as hierarchy, specialization, and routinization. In other words, it is not just hierarchy that matters, but hierarchy that conforms to specific organizing principles. IOs, in this view, are increasingly valorized to the extent that they present modern bureaucratic characteristics.Footnote 76 And law, whether it is hard or soft or something in-between, figures more importantly in global governance than ever before. Indeed, it is often viewed as the gold standard for the legitimation of rules, the paragon of objectivity, and the depoliticizing mechanism that any enduring order needs.Footnote 77

Via rationalization expert knowledge is increasingly valued over lived or learned knowledge. Governance authorities are not only supposed to be staffed by experts with the right training and advanced education, but experts can become something of a class unto themselves and form their own networks that circulate in the environment and influence global governance.Footnote 78 Moreover, expertise, standardization, and specialization has led to the emergence of distinct fields that define rules for regulating activity, standards of legitimacy, and notions of competence and best practices.Footnote 79 Rationalization processes are also associated with standard-setting, benchmarking, and governing through indicators.Footnote 80

Technological Change

While the emergence of new issues and the pluralization of participants has soured many on solutions based on large, bureaucratic multilateral organizations, technological change has created the possibility for more networked, flexible, and innovative governance solutions. As Manulak and Snidal argue, one no longer needs a formal secretariat convening meetings in a headquarters to facilitate governance. The influence of technology goes beyond methods of communication, however. Information that was once hard to get is now easily grabbed with Google, and easily crunched by cheap computing. Social media facilitate communication, lower monitoring costs, and ease the implementation of programs and policies.Footnote 81 Air travel makes it much easier for groups of various sizes to gather. Technological changes have revolutionized communication and coordination, even making it possible to gather in a virtual space: Zoom governance as the new global governance. Governance once limited to vertical links has become increasingly horizontal; and horizontal and vertical links have begun to coalesce into networks. One consequence is that network governance has become the (hyped) solution, touted as more democratic, flexible, and innovative, more capable of learning, and more efficient. All of these developments permit, or encourage, new forms of governance.

And as these technological changes pervade the globe they enable non-state actors to coordinate more easily. Setting aside the question of whether NGOs have wrestled any real power or authority away from states, technology has allowed them to level the playing field in the areas of coordination, information, and even resources. Some of these changes are closely linked to the shift in reigning ideologies of governance discussed earlier in this section. It is hard to say what came first, and perhaps this is a chicken and egg question never to be answered. But it seems clear that as technology has shaped the sense of the possible in governance, so too have ideas about the best models for governance shifted.

Domestic Change

The first eight drivers introduce the role of domestic forces but without necessarily giving it its proper due. There is, however, an established literature in international relations that considers the “second image” and its effects on international order in general and on global governance specifically. Changes in voting patterns, coalitions, regimes, and governments are often attributed to a shift in the state’s strategy toward specific agreements and global governance possibilities. These strategies are molded by domestic actors in power. There also is the “second image reversed” that considers how various global forces – growing interdependence, responses to specific treaties, multilateral arrangements, and international financial institutions – can influence domestic politics and institutions.Footnote 82

Some of this literature hits closer to the subject of this volume, particularly as it considers how domestic coalitions prefer one governance mode over another. There is, for instance, a growing literature on the role of domestic actors in the shift from hierarchies to networks and markets. Illustrative are the groups that have called for an end to hierarchical arrangements altogether (e.g., the International Criminal Court or Trans-Pacific Partnership) or to renegotiate them (e.g., the North American Free Trade Agreement), and the growing role of municipalities and regional governments in transnational networks on climate governance.

The chapters suggest various reasons why domestic actors might become mobilized around governance. For example, Moon argues that the HIV/AIDS crisis and its resulting domestic social pressures led directly to the evolution of governance in global health. Domestic activists might perceive the existing arrangements as inadequate to solve the global problem or want to create arrangements that give them a greater voice. On the other hand, some domestic actors, such as corporations, may wish to preserve hierarchical arrangements because they shut out other non-state actors – a form of regulatory capture. And then there is rising nationalism, which tends to target hierarchical modes of governance because they appear most threatening to sovereignty, because they are the most visible symbols of global governance, or because they are blamed for the perceived degradation of economic welfare and the “purity” of the nation. The two infamous examples are Brexit and the election of Donald Trump, and in both cases a particular form of domestic politics led to a desire to cut the taut ties to global institutions.Footnote 83 However, in contrast to the prevailing wisdom that global institutions are losing their legitimacy and popularity, Tallberg argues that they actually retain considerable support.

One last but critical point is that when accounting for a change in the modes of global governance the chapters rely not only on the drivers we have detailed but also on actors’ preferences, interests, and strategies. Indeed, because these drivers are structural they create underlying conditions of possibility and impossibility, tightening and loosening constraints for particular kinds of action, and recalculating strategies for maintaining and extending power. All the chapters acknowledge how actors are central to the story of change, whether the actors are the USA, the ICRC, professional networks, corporations, NGOs, or UN agencies. Both stasis and change are produced not only by environmental forces, but also by actors that believe that a shift in the mode of global governance must be resisted or engineered. And the reasons for their positions reflect not only a desire to produce more efficient and effective global governance, but also to protect and advance their private interests.

What Is at Stake?

We began this project because we wondered about the state and the trajectory of global governance. Like many before us we were struck by the transformation of global governance, frequently described as “old” and “new.” But the more we dove into the attributes that seemingly marked the change between the past and the present the more convinced we became that, while important, they did not adequately capture the “how” of global governance and the ways it had evolved. Modes of governance provided an alternative way of approaching this critical issue. But what does our focus on modes say about the state of global governance? We reject pat conclusions that might suggest the new is better than the old, or that one mode is necessarily superior to the others. As with everything in life, it depends. For those seeking verdicts we have only hung juries.

But the chapters provide varied ways to unpack the current state of global governance. Each engages, in its own way, two separate but entangled dimensions of the quality of global governance: effectiveness and ethics. Consider effectiveness. Many chapters note that actors sought change because the existing mode was perceived to be ineffective. Did they get what they hoped? The results were mixed. In Andonova’s study of global energy governance, earlier state-dominated governance was unable to produce the kind of collaboration required. Yet it proved difficult for non-state actors to figure out how to slot into a much more decentralized governance framework. Almost all the chapters capture some sort of trade-off that both advances and frustrates the ability to mobilize effective action. Effectiveness is of course a notoriously difficult concept to operationalize, and its evaluation is inherently value-laden: effective for what? Still, the chapters suggest, perhaps unsurprisingly, that clear advances in effectiveness are rare.

Complicating any evaluation of effectiveness, moreover, is that the authors adopt different definitions of effectiveness. Rather than seeing this as a problem, we treat this as an important finding. Effectiveness is an inherently varied concept. For the participants in a given regime effectiveness could mean shaping outcomes, establishing norms or laws, or even changing the mode of governance. Green echoes this sentiment on the issue of climate governance: the change in mode of governance itself is often seen as an effective outcome, yet its long-run influence on the ultimate goal, reversing climate change, is still unknown. Perhaps this is an example of the weary embrace of “good enough governance,” or perhaps it reflects a more meaningful belief that gains in process are critical for gains in substance.

Further complicating any evaluation of effectiveness is that shifts in the modes of governance often led to a change in what was governed. Many of the chapters note how debates about the mode of governance often had the knock-on effect of changing the subject of governance. As Seabrooke and Sending observe, for example, the substance of governance is not independent of the mode. And if the content has changed, then presumably so too does the meaning of effectiveness. Moon notes a similar dynamic in global health: as new modes of governance have led to more effective responses to certain types of crises, other aims have fallen off the table, making net effectiveness difficult to determine. Moreover, some of the push for new modes in global health are as much a reflection of an effort at retaining power (on the part of traditionally powerful actors) as an effort at improving effectiveness.

The second dimension of quality includes ethics: legitimacy, fairness, accountability, transparency, and democracy, among others. Many studies of global governance tend to fall into a depoliticized stance, to treat governance as a technical accomplishment: all means to the neglect of ends. But ethics is always in the background, and often in the foreground, of global governance. The chapters often refer to legitimacy, accountability, and other normative claims. Legitimacy is not incidental to global governance but central, because it focuses on whether global governance and its institutional arrangements are accepted and decisions followed. In this sense legitimacy is both a deontological concern and an aspect of effectiveness: more legitimate systems tend to be more effective and, perhaps, more efficient. Indeed, it is worth remembering that the concept of global governance became the term of choice for describing new forms of cooperation that were presumed to represent a more legitimate form of international order. The question of legitimacy is expansively covered by Tallberg, so we need not say much here.

Legitimacy traditionally has two components. Process legitimacy regards whether decisions go through the right process. In contemporary international society the right process is often assumed to be participatory and democratic. Output legitimacy asks whether decisions are largely consistent with the values of the community. It is possible to have one and not the other but legitimate institutions ideally have both. Hierarchical modes of governance may be effective but they are routinely accused of lacking legitimacy and running a democratic deficit. In response, demands for inclusivity have risen.

But does inclusion necessarily generate more legitimacy? Many of the players newly included claim to speak on behalf of the “public good” or the “people” but this self-presentation seems to be based on a combination of self-assuredness, ideology, and hubris. Kahler reminds us that private modes of governance, once considered normatively acceptable and legitimate at the beginning of the twentieth century, have become more contested in the twenty-first. Manulak and Snidal point to a variant of the inclusion–legitimacy relationship: that transnational actors can themselves be legitimized by their inclusion in informal international organizations. This has implications for effectiveness but from a particular standpoint: the head of government, who can now avoid a potentially complex and stultifying domestic bureaucracy.

Expanding the circle of inclusion is not infinite but rather has clear boundaries – some actors or stakeholders are always left out, and these exclusions shape whose interests are represented and whose voice counts. Moon points out how the inclusion of drug companies as part of multi-stakeholder efforts in global health has the potential to delegitimize governance efforts in the eyes of some. Similarly, Barnett suggests that a combination of hierarchy and networks dominates in the area of humanitarianism, but important actors in the Global South are summarily excluded from what he labels as the Humanitarian Club. This is consonant with those who claim that global governance lacks legitimacy because it fundamentally represents Western interests and values. As Amitav Acharya and others have emphasized, global governance, and its sidekick the liberal international order, were never very legitimate in the eyes of the Global South.Footnote 84

The chapters reinforce the growing sense that global governance will also be judged on other normative standards. A global governance arrangement might be effective but nevertheless rejected if it is seen as unfair or unjust. But the chapters also reinforce the view that it is difficult to harmonize these culturally and historically bound judgments. Trade agreements have to provide economic gains for both sides, but there are instances in which a trade proposal is rejected by one side because it is seen as insulting. The International Criminal Court has run into various situations in which “global justice” is in tension with “local justice.”

Power can also be understood as part of the normative dimension of global governance. Although in many of the chapters forms of power are used to discuss why some actors were able to achieve their preferred mode of governance, considerations of power also figure centrally in the consequences of a change in the mode of governance. There are distributional consequences, which of course link to questions of fairness. There are questions of arbitrary power, which is most apparent in the growing demand for accountability and transparency and the desire to ensure that there are mechanisms in place so that those who are in power can be held to account by those who are affected by their decisions.Footnote 85 And, as just noted, there are matters of representation. Many of the chapters point to the demand for greater inclusion to limit the influence of the powerful. Sometimes this happens within hierarchy, as when a small group of states move to include other states. Sometimes this happens within networks. Several of the chapters question whether these moves toward greater inclusion present a real opportunity for giving voice to the marginalized, or rather are merely ways of giving the appearance of growing equality while maintaining the status quo.

Do effectiveness and normativity reinforce or undercut each other? Avant suggests that a more inclusive global governance will be more effective. Other chapters suggest that while more voices might lead to improved outcomes, they could also lead to the lowest common denominator or simply more veto players. In many of the chapters the search for more effective global governance arrangements went in the direction of markets and networks, which appeared to unleash more activity than ever.

The big question is whether change has actually increased the prospects of solving global problems or instead provides only the illusion of improvement. Some argue that there is no substitute for hierarchies when it comes to solving big global problems, and often point to the golden years of global governance after the Second World War and the end of the Cold War. Mueller and Pevehouse echo this idea when they question the move to regionalism in trade: the classic building blocks versus stumbling blocs debate in trade liberalization. Regional arrangements may have advantages in terms of legitimacy and perhaps effectiveness for participants, but from a global welfare perspective economists would argue that such regional arrangements are suboptimal. The question of effectiveness for what or whom is always present.

Others argue that these hierarchies are part of the problem – lumbering dinosaurs that must yield to nimbler, fluid, and inclusive networks and markets to deliver the goods.Footnote 86 Hierarchies are for planners, while markets and networks are guided by searchers.Footnote 87 Hierarchies are antidemocratic while markets and networks are more inclusive and capture the wisdom of the public. But are the major challenges of today fixable or even manageable via piecemeal, incremental, and disorganized efforts?Footnote 88 Moreover, if the “shadow of hierarchy” is omnipresent this mode of governance can never be replaced in an anarchic world, only managed. In sum, hierarchical modes just might prioritize effectiveness through a concentration of power – a concentration that is increasingly considered illegitimate. Whether this is an insurmountable tension is not clear.

Market modes of governance promise greater efficiency and effectiveness, and (usually) the diffusion of power across units within markets. Yet, except in abstract models, markets are never perfect. Markets require property rights and regulation to remain robust from predation (and the illegitimacy that follows) and competitive. Property rights and regulations are never value neutral and often have their own mechanisms of inclusion and exclusion, creating their own forms of hierarchy. Networks modes of governance are frequently championed as legitimate and effective: offering a voice for many, efficient allocation of expertise, local expertise for legitimacy, and the diffusion of power away from traditional stakeholders. But some of our authors suggest that the sum may not be more than the whole of the parts. Decentralization can lead to a lack of efficiency and worse: to competition and cross-purposes. And where is the accountability point in networks? A boss may be more easily tamed than a hydra-headed monster.

Actors are constantly tweaking and sometimes attempting to transform modes of governance with the hope that they will improve their effectiveness and be more fair, accountable, and just. But the chapters suggest that effectiveness and ethics are something of a balancing act in global governance, and rarely do all good things go together. And what might be prescribed as the best fit for the social situation is often elusive. Studies of global governance have been quite good at spinning prescriptions, but the empirical reality is often quite different because states care about more than just effectiveness and ethics; in fact, an argument can be made that often effectiveness and ethics is the last thing on their minds. Perhaps the world gets the global governance it deserves.

Overview of the Chapters

Global governance is a huge topic and this is an ambitious book. Yet there is much we left out. Although the volume has a fixed set of concerns and questions we decided to avoid the focus-structured comparative method in favor of allowing the contributors to address the foundational questions we raise in this Introduction in the manner that made the most sense to them. Although the obvious disadvantage of this open-ended approach is that we lose something in the ability to draw firmer generalizations, the decisive advantage is that we open the aperture and possibly capture processes that might otherwise be overlooked.

Perhaps the most difficult decision was selecting the featured areas of global governance. This was complicated for a few reasons. First, the standard way of dividing global governance is by issue area, but there are issues areas that have expanded, converged, and layered (which is one reason we have regime complexity), and there are some issue areas that are so large, such as the environment, that it makes greater sense to disaggregate into different subareas, such as climate change, energy, biodiversity, and so on. Second, this is a book that is about the transformation of global governance writ large and not the individual stories of different issue areas. Those stories are important, but we want to keep a focus on the forest as much as the trees. Consequently, while it might make sense to pick the “superstars” of global governance, such as climate change, arms control, financial regulation, peacekeeping, and so on, it is difficult to know a priori whether these issue areas tell us everything we want to know about the transformations that are taking place. For instance, one of the major innovations in global governance occurred decades ago with the establishment of the World Commission on Dams (a coalition of NGOs and international financial institutions), which was not exactly a marquee issue at the time.

Given these very important limits on case selection we decided in favor of something much more practical, inductive, and intuitive: to identify some of the important areas of global governance, with importance defined in terms of what they might say about the evolution of different modes of global governance. The consequence is that we believe the chapters provide a sufficient range of coverage, but there are areas that are not covered that we wish had been, for instance gender, development, cybersecurity, and refugees. Our claim is not to be comprehensive. Rather, we (hope to) demonstrate the importance of the question of transformation in the architecture of global governance and, in the chapters to come, map out the broad contours of that phenomenon. We are demonstrating and beginning to map out a phenomenon, not testing a theory.

In Chapter 1, Deborah Avant compares the architecture of global governance across two security issues: the regulation of private militaries and of small arms. In the former case she argues that a multi-stakeholder arrangement engaging a panoply of actors has replaced a largely hierarchical structure previously dominated by states. In the latter, networks reign in particularly contentious fashion, leading Avant to suggest a governance deficit in this issue area. Avant argues that geopolitical changes and an emergence of new actors lead to an opening in the area of private militaries that was filled by Swiss policy entrepreneurs. For the small arms area, while networks have actively sought solutions, and policy entrepreneurs have attempted to build momentum for cooperation, a continued attempt to create a hierarchical structure has met with less success. Avant concludes that governance strategies that are more open to different actor types are better able to generate governance coordination.