Notions that World War II—particularly the logic of fighting a war against Nazi racism—led to increases in white support for black civil rights are widespread. Civil rights activists, journalists, academics, and others at the time regularly claimed that when shown “the gross discrepancy between our ideals and our practices,” as one contemporaneous observer described it, white Americans would be forced to confront their own racial prejudices and legacies of discrimination, resulting in a major step forward for racial progress.Footnote 1 Indeed, claims about World War II's impact on white racial attitudes can be found in sources ranging from contemporaneous accountsFootnote 2 to present-day historical institutionalist scholarshipFootnote 3 and scattered other sources like constitutional law books.Footnote 4 Sometimes the claim is direct and central (e.g., Gunnar Myrdal's An American Dilemma); at other times, it is taken for granted in the background (e.g., Philip Klinkner and Rogers Smith's The Unsteady March). However, in making varied assumptions about the war's impact on white attitudes, such accounts have generally not analyzed public opinion surveys from the 1940s that might allow for a better empirical assessment of such claims.

This article provides such an assessment. Based on an analysis of the available survey evidence, I argue that the war's impact on white racial attitudes is more limited than is widely assumed.Footnote 5 While there is some evidence white racial prejudice decreased during the war, this is generally not true for attitudes toward racially egalitarian policies. White opposition to federal anti-lynching legislation seems to have actually increased during the war. I also assess whether serving in the war liberalized white veterans, relative to their nonveteran counterparts. I found a much more complex story among veterans. They are not distinguishable on a wide range of racial prejudice measures. However, they are distinctive on two issues: In the late 1940s, they were more likely to support federal anti-lynching legislation; and in the early 1960s, white veterans in the South offered stronger support for black voting rights.

These results have implications for political science in several ways. First, this article serves as a useful corrective to common assumptions about the war's effects on white racial attitudes. The few political science analyses of how the war did impact civil rights have focused entirely on social movements and elite institutions. As such, their background claims about mass attitudes have not been fully substantiated.Footnote 6 Second, this article complements work assessing the individual-level impacts of military service on black Southerners.Footnote 7 While civil rights historians have long believed service in the Second World War had transformative impacts on black veterans—and this has been affirmed with survey analysis by Christopher Parker—there has been much less historical scholarship about white veterans in this regard, and none that I am aware of has utilized survey data. By combining analyses of surveys that identified veteran status in the war's immediate aftermath with the white sample of the 1961 Negro Political Participation Study survey that Parker used to analyze black veterans, this article complements previous scholarship by offering a different vantage point. Along with these specific contributions, this article also makes a more general contribution to the literature on attitudinal change, particularly the question of whether attitudes generally, and white racial attitudes in particular, are event-driven or stem largely from less contingent, more structural sources.Footnote 8

The article proceeds as follows: I begin with historical background, particularly by situating the analysis with reference to contemporaneous discussions of the war and civil rights in the 1940s. I then relate this to present-day academic accounts that have addressed these themes and show what is missing from these scholarly accounts. Second, I develop a framework for assessing the possibility of white racial attitude change in the World War II era by drawing on theoretical accounts of attitude change in the mid-1960s civil rights era and accounts of the effects of World War II era military service on black veterans. This leads to two testable hypotheses regarding the liberalization of white racial attitudes. After framing my inquiry, I discuss the data sets used and methods necessary to adequately work with them. I then present the results of my analysis. I conclude with a discussion of my findings and areas for future research, as well as how this study of white racial attitudes can help build a broader framework for understanding the potentially heterogeneous effects of the Second World War on American racial politics more generally.

BACKGROUND

Historical Context

Many elites in the 1940s saw a connection between the war effort and domestic racial issues. The most famous example is Gunnar Myrdal and his mammoth study, An American Dilemma: The Negro Problem and Modern Democracy. Over the course of nearly 1,500 pages, Myrdal made the contradiction between the aims of the war and Jim Crow clear:

This War is an ideological war fought in defense of democracy. The totalitarian dictatorships in the enemy countries had even made the ideological issue much sharper in this War than it was in the First World War. Moreover, in this War the principle of democracy had to be applied more explicitly to race. Fascism and nazism are based on a racial superiority dogma—not unlike the old hackneyed American caste theory—and they came to power by means of racial persecution and oppression. In fighting fascism and nazism, America had to stand before the whole world in favor of racial tolerance and the inalienable human freedoms.Footnote 9

The book is filled with such claims. “There looms a ‘Negro aspect’ over all post-war problems,” Myrdal proclaimed.Footnote 10 Some 571 pages later, he was more confident in his phrasing: “There is bound to be a redefinition of the Negro's status in America as a result of this War.”Footnote 11 Myrdal's book was, according to Alan Brinkley, a “major factor in drawing white liberal attention to problems of race—precisely because Myrdal himself discussed racial injustice as a rebuke to the nation's increasingly vocal claim to be the defender of democracy and personal freedom in a world menaced by totalitarianism.”Footnote 12 Although it received some scattered criticism, the nature of the book—its social scientific language, nonpartisan sponsorship, massive length, Myrdal's European-ness—led it to seem like a definitive analysis of the American race problem in elite discourse.Footnote 13

This was also perceived, in more negative terms, by certain prominent racial conservatives. Charles Wallace Collins, a Southern attorney whose 1947 book, Whither Solid South?, provided “intellectual guidance” to the Dixiecrat movement, worried that the war “offered the opportunity for the rationalization of the position of the Negro as a citizen of the United States in a time of war.”Footnote 14 He did not view this prospect in a positive light.

Along with the general sense that the war might lead to aggregate changes in white attitudes, there was likewise a more specific belief that serving in the war would make white veterans more racially tolerant:

During the Detroit race riots in 1943 three sailors waded in to a white mob which was beating unmercifully a slender Negro youth. “He isn't doing you guys any harm. Let him alone!” one of the trio shouted as he and his companions rescued the Negro and fought back the mob.

“What's it to you?” one of the rioters snarled.

“Plenty,” replied the sailor. “There was a colored guy in our outfit in the Pacific and he saved the lives of two of my buddies. Besides, you guys are stirring up here at home something we are fighting to stop!”Footnote 15

This suggestive anecdote is drawn from NAACP leader Walter White's 1945 book, A Rising Wind. Although perhaps apocryphal—White had a tendency to capture dialogue in a manner that seems awkwardly folksy to contemporary ears—such tales nevertheless reached a wide audience and were consistent with other accounts at the time suggesting the war had liberalized the previously racist views of white soldiers fighting for democracy.

White shared other interesting stories as well. In England, he visited the black G.I. Liberty Club—despite his taxi driver's insistence that he must mean the white Rainbow Club. Although designed for black soldiers, there were some white G.I.'s present as well—“the Georgia accent of one of them was thick as the mud of the Chattahoochee,” according to White. The white Georgian told him he preferred the Liberty Club to any of the white clubs because he had become friends with some black soldiers who would not be welcome at the all-white alternatives. White inquired about whether these friendships would continue upon his stateside return: “Ruefully, he spread his hands, palms upward, and shrugged his shoulders. ‘I don't know,’ he said sadly.”Footnote 16

Another white soldier recounted his experiences at the Stage Door Canteen in New York City prior to being sent overseas. The first time the soldier went there, he found black hosts and servicemen and he left in anger. But because the canteen was the standard gathering place for soldiers unfamiliar with the city, he went back several times and had a change of heart. “If we can play together, why can't we fight together?” he asked White. When informed of proposals to establish an integrated unit that white and black soldiers could volunteer to join, he replied, “I'd like to be the first to volunteer. Then I wouldn't feel like a Goddamned hypocrite when people over here ask why, in fighting a war for democracy, the United States sends over one white and one Negro army.”Footnote 17

However, not all of White's interviews were so positive. Many white soldiers expressed significant prejudice. Racial rumors abounded, generally started when white Americans told European locals wild tales of supposed black behavior.Footnote 18 Perhaps a more interesting anecdote, however, is White's conversation with General Dwight Eisenhower. Referring to a discussion with an unnamed New York journalist, Eisenhower “almost belligerently” exclaimed to White, “He told me my first duty was to change the social thinking of the soldiers under my command, especially on racial issues. I told him he was a damned fool—that my first duty is to win wars and that any changes in social thinking would be purely incidental. Don't you think I was right?”Footnote 19 Such conversations suggest the link between white military service and civil rights liberalism might not necessarily be so clear.

More academic work also connected military service to potential changes in racial attitudes. In To Stem This Tide: A Survey of Racial Tension Areas in the United States, written in 1943, Charles Johnson and his associates shared an anecdote from Evansville, Indiana, where a train conductor ordered a group of white and black soldiers from the same town to separate, but a white soldier refused the order and threatened to fight the train crew.Footnote 20 In the war's aftermath, University of North Carolina sociologist Howard Odum, writing in 1948, described “a relatively large number of young college students and returning G.I.'s advocating a more liberal practice with reference to race relations” in the white South.Footnote 21 These claims fit with what Walter White was telling the War Department. In an April 1944 memorandum, for instance, White described his tour of the North African and Middle Eastern Theatres of Operation, writing, “As men approach actual combat and the dangers of death, the tendency becomes more manifest to ignore or drop off pettiness such as racial prejudice.... When German shells and bombs are raining about them, they do not worry as much about the race or creed of the man next to them.”Footnote 22

The historiography on the relationship between World War II and black civil rights reflects the possible ambiguities of the relationship. In the 1960s, this era was referred to as the “forgotten years of the Negro revolution.”Footnote 23 In the strongest form of this perspective, one historian declared that “the war in many ways made the civil rights movement possible.”Footnote 24 More recently, historians have increasingly taken a more critical perspective on the war's relationship with civil rights. “If historians search for the roots of the civil rights movement in the wartime struggle, they will doubtlessly find something in the discordant record resembling the evidence they seek,” Kevin Kruse and Stephen Tuck write. While acknowledging “the turmoil and rhetoric and bloodshed of war did indeed provide a far-reaching challenge to Southern, national and global systems of race,” they argue that it “did not push racial systems in a single direction, and certainly not one moving inexorably toward greater equality.”Footnote 25

The War, Racial Attitudes, and Historical Institutionalists

Present-day political science scholarship has similarly made claims about the war's effects on racial attitudes, often in the background of other arguments about political institutions. Klinkner and Smith's The Unsteady March, for example, argues that war is a necessary, albeit not sufficient, condition for racial progress in the United States. In particular, they point to three factors: large-scale war requiring mobilization of black soldiers, enemies of a nature that require the government to justify the war in egalitarian rhetoric, and protest movements able to make the government at least partially live up to its justificatory rhetoric. Daniel Kryder's Divided Arsenal demonstrates how wars in American history coincide with increases in racial crowd violence and examines how the Roosevelt administration managed racial conflict to successfully execute the war. More recently, Robert Saldin's War, the American State, and Politics since 1898 offers a more general and expansive overview of how war has shaped American domestic policy, including the greater inclusion of marginalized groups. These three works all share a focus on political institutions. However, they also make several striking comments about the relationship between the war and white attitudes—without any original analysis of public opinion data.Footnote 26

Klinkner and Smith claim, for example, that it is “hard to escape the conclusion” that the “Nazi menace forced at least some white Americans to begin to reexamine the racial inequalities in their midst.”Footnote 27 Later, they fill in the causal processes. “The ideological demands of fighting an enemy who espoused racial hierarchies made more white Americans sensitive to the presence of racial discrimination in America,” they argue. “The vision of blacks marching to claim their rights contradicted the image of America as the defender of democracy.”Footnote 28 Klinkner and Smith do offer some willingness to concede that white opinion in the South did not liberalize and perhaps even hardened in its white supremacist resolve.Footnote 29 But in general, their claim about a shift in white attitudes is fairly strong. This claim about public opinion affects not only their assessment of the public but also normative assessments of other actors like President Franklin Roosevelt. “Roosevelt's unwillingness to take a stronger stand on racial issues was, in hindsight, regrettable and costly,” they argue. “True, white Southerners were becoming more restive, but it seems clear that in the context of the war, nationally public attitudes on race had shifted enough that he could have been more outspoken for reform.”Footnote 30

While Klinkner and Smith's book contains no analysis of survey data, their account has been cited in discussions of liberalizing white attitudes. Saldin, for example, refers to Klinkner and Smith as an authority in asserting an “undeniable growth of racial liberalism linked to World War II,” including shifts in mass opinion.Footnote 31 Even though Klinkner and Smith's research is not centrally concerned with public opinion, it has had the effect of strengthening the view that World War II liberalized white racial attitudes.Footnote 32

Although this article focuses on the nature of white mass opinion, this tendency extends into other realms like the attitudes of white elite political actors. For instance, it is often taken for granted that the 1944 Smith v. Allwright case outlawing the white primary was motivated, at least in part, by the ideological logic of the Second World War. Yet the evidence for this claim is surprisingly lacking. The legal scholar Michael Klarman is perhaps the clearest example. While Klarman gives some credit to “Roosevelt's virtually complete recomposition of the Court,” he argues this explanation is “missing something more fundamental—the significance of World War II.” His argument, however, is surprisingly vague. “This is necessarily a point of speculation,” he acknowledges, “because nothing in the Smith opinion or the surviving conference notes refers to the significance of the war. Still, the Justices cannot have failed to observe the tension between a purportedly democratic war fought against the Nazis, with their theories of Aryan supremacy, and the pervasive disenfranchisement of Southern blacks.”Footnote 33 Klinkner and Smith make a similar argument. “The Court's decision in Smith reflected its emerging stress on the protection of civil and political rights, an emphasis influenced by the changing global context,” they write. Although they acknowledge that Justice Stanley Reed, who wrote the Smith majority opinion, “made no mention of the war,” they point to two sources: a New York Times correspondent, who declared the “real reason” for the Court's move against the white primary was “that the common sacrifices of wartime have turned public opinion and the Court against previously sustained devices to exclude minorities,” and a 1979 book by the historian Darlene Clark Hine, which calls the white primary “one of the casualties of World War II.”Footnote 34 However, neither source provides direct evidence that the Smith case was affected by the war, yet they are treated as though they do.Footnote 35

Military Service and Racial Attitudes

Scholarship on the attitudinal and behavioral impacts of the war on veterans, by contrast, has used public opinion data. However, it has focused almost entirely on black veterans. Christopher Parker, for example, convincingly argues that military service in the Second World War, as well as the Korean War, had a direct impact on the willingness of black veterans in the South to challenge the white supremacist status quo.Footnote 36 However, there remains an open question of whether the war might have also had significant ramifications for white attitudes and political behavior. Parker argues that “we should expect black Southerners who were exposed to different, more egalitarian cultures to have begun an aggressive interrogation of white supremacy.”Footnote 37 To what extent might this be true for whites who experienced these same “more egalitarian cultures”?

Studies of white veterans have been more local and specific. Jason Sokol's history of white Southern reactions to civil rights quotes individual white Southern men who, as a result of their service in the Second World War, came to learn “that freedom means more than just freedom for the white man,” as one phrased it. However, Sokol suggests that such attitude changes were small, constituting “only a small fraction of white southern servicemen.”Footnote 38 Although Sokol's analysis is enlightening in many respects, it stops short of being generalizable by the standards of political scientists.

Perhaps the best research on white veterans is Jennifer Brooks's analysis of veterans in postwar Georgia. While many Southern black men returned from World War II determined to tear down white supremacy, Brooks suggests that the impact of military service on returning white veterans was more heterogeneous. “A small but vocal minority of southern white veterans also defined the war's meaning and their own participation in it as a mandate to implement a political freedom that applied to all Georgians,” she writes. These white veterans joined returning black soldiers in their efforts. However, this push for racial equality “provoked an immediate backlash from other white veterans determined to sustain all the power and prerogatives of white supremacy.”Footnote 39

What's Missing

This review suggests at least two avenues for research, then. First, is the available survey evidence consistent with the argument that World War II led to an increase in white racial liberalism? Second, in the war's aftermath, were white veterans more racially liberal than their nonveteran counterparts? The next section relates these questions to theoretical frameworks for thinking about attitudinal change on race and sets out testable hypotheses to assess the war's impact on white racial attitudes.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

What does it mean to ask about the effect of something like World War II? To be a useful analytical concept, “the war” must be unpacked into its constitutive elements, each of which can have different logics. There are several distinctive aspects of World War II, two of which are (1) the ideological sense of the war and (2) the massive material undertaking of the war. The former most obviously describes the anti-racist logic of a war against Nazism that so many have linked it to. The latter includes shifts related to wartime industrialization and military buildup, including migration related to the former and personnel needs related to the latter. Industrial and military institutions were faced with new pressures as a result, which opened new possibilities and points of leverage for the civil rights movement, especially on job discrimination issues.

While acknowledging these political-economic changes (which I discuss further in the conclusion), this article considers white racial attitudes as a vantage point from which to assess the war's potential ideological logic: Did a war against Nazism and fascism lead to a rethinking of the racial status quo for white Americans on the home front?Footnote 40 To build a framework for assessing attitude change, I first review theoretical debates about the catalysts for aggregate white racial attitude shifts in the 1960s civil rights era. I then consider Parker's account of changes in the attitudes of black veterans who served in World War II and Korea. This leads me to develop a framework for thinking about the possibility of aggregate white racial attitude shifts in the World War II era, as well as what should be expected regarding the racial attitudes of white veterans. Based on this framework, I set out two testable hypotheses.

White Racial Attitude Shifts in the Civil Rights Era

Scholars have debated whether opinion shifts in the 1960s were elite-driven or more bottom-up.Footnote 41 Others have examined factors like childhood socialization and generational replacement.Footnote 42 However, I focus here on the role of the national media. Many scholars of trends in public opinion point to the role of the media as a catalyst for change in white racial attitudes. Howard Schuman et al., for example, refer to “many Northern whites who witnessed, through television and other media, the brutality of Bull Connor and other white supremacists.” They note that public opinion trends fit with historical accounts that “speak of the rethinking and searching of conscience that were prompted by the events of 1963.”Footnote 43

Benjamin Page and Robert Shapiro also note this “pro-civil rights opinion trend,” and likewise suggest “a good many events of the late 1950s and early 1960s, heavily covered by the mass media, surely played a part.”Footnote 44 Although they acknowledge “the general hostility of Americans to protests and demonstrations,” they argue that “televised images of Southern policemen beating peaceful black demonstrators and setting dogs upon them galvanized the nation. There can be little doubt that the civil rights movement and Southern whites' highly visible ‘massive resistance’ to it had a major impact on public opinion.”Footnote 45 Media coverage—especially of violent white resistance to protesters—is seen as key by both of these major accounts of attitudinal trends.

Paul Kellstedt offers the most systematic study of the relationship between aggregate racial attitude change and the quantity and tenor of media coverage. He shows how the number of stories about race and civil rights in Newsweek spiked beginning in 1963, when there were 152 such stories. This continued for several years during the height of the 1960s civil rights movement. Kellstedt also points to the tenor of the coverage, demonstrating how this era saw media coverage that framed the debate in egalitarian, rather than individualistic, messages.Footnote 46 This, he argues, was a hospitable environment for the growth of racial liberalism in aggregate public opinion. The role of the media is absolutely central for Kellstedt. Fitting with Schuman et al. and Page and Shapiro, he notes, “Most of the key events of the movement, after all—desegregation battles in Little Rock and elsewhere, bus boycotts, freedom rides—took place in communities that few non-southerners would have known about were it not for the national press.”Footnote 47

The 1960s civil rights era is a useful comparison to the World War II era because it highlights important historical differences, one of which is the variable role of the media in covering and framing civil rights protest. Compared to the mid-1960s, the national media in the World War II era largely did not discuss racial inequality.Footnote 48 There were of course some exceptions—discussion of the Fair Employment Practices Committee (FEPC) and the Detroit race riot being two examples—but these were not the norm, nor did they fit into the egalitarian tenor emphasized by Kellstedt. As such, any theoretical tensions between American ideals of egalitarianism and the reality of Jim Crow racism were not primed for most white Americans. Thus, while it is possible that the ideological logic of the war led to a rethinking of racial attitudes, it is also possible this tension was perceived more by elites than the white mass public more generally. Accounts of the war's relationship with civil rights have tended to emphasize the plausibility of the ideological logic argument, rather than thinking through the extent to which the broader public recognized the validity of such an argument or not.

Black Veterans and Civil Rights Attitudes

Veterans are especially likely to be affected by wartime. Most veterans serve during what has been called “the impressionable years” of their late teens and early twenties, when attitudes of all sorts are most likely to crystallize.Footnote 49 Parker analyzes the “radicalizing experience” of military service for Southern black men in particular.Footnote 50 He presents a theoretical framework to explain black veterans' attitudes and behavior. Building on the citizen-soldier tradition in republican political thought, Parker examines how black veterans interpreted the meaning of their military experience, then argues this led to a new belief system he calls “black republicanism.”

In many ways, this framework is specific to the experience of black soldiers. For instance, Parker highlights the tension between how black soldiers were treated and the ideals for which they were fighting. White soldiers were simply not treated with the same sort of second-class status. However, his discussion of the effects of being deployed overseas raises interesting questions about effects on white soldiers. Parker, though, clearly distinguishes between white and black soldiers in this discussion. “For white servicemen, travel overseas resulted in increased self-awareness,” he writes. “For black servicemen, especially from the South, experiencing life overseas went beyond self-awareness. Deployment during the Second World War and the Korean War exposed well over a million black Southerners—who were accustomed to discrimination and oppressive conditions—to a model of race relations in which the indigenous, dominant group often treated them with a measure of respect.” This, he argues, gave them additional motivation “to question the legitimacy of white supremacy.”Footnote 51

Although they were differentially situated, white soldiers were nonetheless similarly exposed to such variation in race relations. As Parker notes in a general sense, “exposing people to new patterns of social relations and cultural norms tends to expand their worldview by enlarging their perceptions of what is possible.” This logic, he argues, leads to an expectation that “black Southerners who were exposed to different, more egalitarian cultures” would “have begun an aggressive interrogation of white supremacy.”Footnote 52 However, the extent to which such exposure might also have shifted white attitudes merits some examination as well.

White soldiers experienced the war differently than whites on the home front. Like black soldiers, white soldiers were also exposed to “more progressive cultures elsewhere,” where “dominant groups often treated [black soldiers] with a measure of respect.” We should not expect “an aggressive interrogation of white supremacy,” as Parker's framework predicts for black veterans. However, insomuch as the experience could have “enlarg[ed] their perceptions of what is possible,” it might have at least led to new questions. It seems plausible, then, that exposure to new possibilities could have led at least some white veterans to be more open to racial liberalism. If any whites were to be liberalized as a result of the war, veterans would seem to have been very plausible candidates. While all whites were in some sense “treated” by the war, those who served in the military were certainly affected more directly.

Assessing White Racial Attitude Change During World War II

This discussion leads to two hypotheses, which I assess in the remainder of this article. Here I briefly describe each hypothesis and discuss the grounding for either a positive or null outcome. I call the first the racial liberalization hypothesis:

Racial liberalization hypothesis: World War II led to liberal shifts in white attitudes toward race and civil rights.

The racial liberalization hypothesis is simply an explicitly stated version of the common view. Not everyone believes this—Kryder's book suggests that it is likely incorrect—but it is intellectually predominant. It is also entirely plausible. If the racial liberalization hypothesis is correct, the most likely mechanism linking the war to white racial attitudes is the ideological logic of a war against Nazi racism undermining elite justifications of Jim Crow. Certainly, civil rights activists—advocating as they did a Double-V campaign for victory at home and abroad—found this logic compelling.Footnote 53 In the aftermath of the 1943 Detroit race riot, an editorial in The Nation declared, “We cannot fight fascism abroad while turning a blind eye to fascism at home. We cannot inscribe our banner ‘For democracy and a caste system’.”Footnote 54 Such statements gave the institutional support of white liberals to similar claims being made by the black civil rights movement.

It is often assumed that many ordinary white Americans saw this connection as well. Along with the previous examples, such accounts can be found in sources as far-flung as constitutional law books. Writing of World War II, Alfred H. Kelly asserts,

The egalitarian ideology of American war propaganda, which presented the United States as a champion of democracy engaged in a death struggle with the German racists, created in the minds and hearts of most white people a new and intense awareness of the shocking contrast between the country's too comfortable image of itself and the cold realities of American racial segregation.Footnote 55

This claim is simply presented as background to a discussion of Brown v. Board; it is indicative of a widespread belief that the racial liberalization hypothesis is accurate in popular understandings of the war.

However, there is also theoretical grounding for a null or even negative result. Southern newspaper columnist John Temple Graves, for example, wrote in 1942, “They have invited their followers to think in terms of a Double V-for-Victory—victory in battle with Hitler and victory in battle at home. Victory, unhappily, doesn't work that way.”Footnote 56 Later in the same article, while detailing improvements in the conditions of black Southerners during the war, he noted the decline of lynchings, but warned, “Unhappily the number may increase now as a result of the agitations of the white man against the black and the black against the white.”Footnote 57 Indeed, it is possible to imagine Southern whites fearing that the Double-V campaign was being persuasive, and thus doubling down on their white supremacist resolve.

Further, the relative dearth of national media coverage related to race and civil rights politics would imply that a framework like that of Kellstedt's would not apply as well to the World War II period. While the ingredients for an egalitarian media framing were there, the national media chose not to put it together. Many whites, therefore, simply might not have connected the dots. As such, a null result would be theoretically consistent with Kellstedt's media-centric model.Footnote 58

The second hypothesis is a variation on the racial liberalization hypothesis focused on distinctions between veterans of the war and those who did not serve directly:

Racial liberalization hypothesis for veterans: World War II liberalized the racial attitudes of white veterans, relative to their nonveteran counterparts.

The racial liberalization hypothesis for veterans shifts the focus from temporal shifts in the aggregate white public to differences between otherwise similar veterans and nonveterans. Of course, nonveterans were still “treated” by the war, but indirectly rather than directly. Compared to whites who experienced the war on the home front, whites who served in the military might have felt more closely connected with the anti-Nazi crusade; they might also have encountered black soldiers and changed their opinions about at least some aspects of race relations. Their exposure to the sorts of relatively more egalitarian cultures in places like France and England that Parker points to as inspiring black resistance might have likewise made white soldiers rethink the norms of their own country.

Theoretical grounding for a null result here can be found in arguments that white soldiers were fighting to defend their way of life—white supremacy and all—rather than something more transformative. Many white veterans simply wanted to return home and resume life exactly as they had left it. “That often meant supporting Jim Crow as staunchly as ever,” Sokol writes. “Many believed they had fought to defend, not overturn, racial customs.”Footnote 59 Parker, similarly, notes that many white soldiers brought their racial views with them, rather than being amenable to new social norms. Indeed, many white soldiers from outside the South were exposed to Southern Jim Crow for the first time in the military, as the military segregated soldiers by race. The extent to which various contradictory outcomes are entirely plausible suggests the merits of carefully assessing the evidence for each variant of the racial liberalization hypothesis.

A quick aside is in order regarding the focus on whites. This article chooses to restrict the analysis to whites for two reasons, one substantive and one methodological. Substantively, the broad question is about whether racist views can be brought into question by an external shock like World War II. Focusing on whites makes sense in this regard. For the veterans analysis, analyzing white veterans complements the analysis of black veterans offered by Parker. Methodologically, the 1940s survey data undersampled black respondents generally, but especially undersampled Southern black respondents. Since three-fourths of all African Americans lived in the South in the 1940s, this is a substantial methodological limitation for any analysis of black public opinion. Given this substantive focus and the methodological deficiencies of quota sampling, I argue that a focus on white attitudes is justified. Pairing the results presented here with other work—especially comparing the white veterans results with Parker's analysis of black veterans—will result in a fuller depiction of racial attitudes more generally.

DATA AND METHODOLOGY

To assess the first hypothesis, I used public opinion surveys from 1937 to 1950.Footnote 60 I examined measures of prejudice and policy preferences that were repeated at multiple time points. This involves six questions about general racial attitudes and policy questions about lynching and the poll tax.Footnote 61 I discuss the question wordings in the relevant sections.

To correct for the known biases of the quota sampling procedure employed at the time, I used the method advocated by Adam Berinsky and Eric Schickler. This effectively involves breaking the sample into demographic subgroups and using census data to weight each subgroup according to their share of the population.Footnote 62 This is discussed along with question wordings throughout. To assess aggregate shifts, I made a series of temporal comparisons using the weighted numbers. If the racial liberalization hypothesis is correct, then the liberal position on each issue should increase over time. However, if there is no change—or if there is actually an increase in the conservative position—then the racial liberalization hypothesis is not supported.Footnote 63

To assess the second hypothesis, I examined public opinion surveys from two distinct time periods: the mid- to late 1940s, to assess the more immediate impact of the war, and the early 1960s, to assess the longer-term impact. The methodological challenge here was finding surveys that ask about race or civil rights and also identify veteran status. The first section used two surveys to analyze the first hypothesis, but in a slightly different way. I used an additional survey that asked about military integration. I then moved ahead in time and used the Negro Political Participation Study, a survey of black and white Southerners—defined as the former Confederate states—conducted in 1961. This study merits further introduction. The Negro Political Participation Study was conducted by principal investigators Donald Matthews and James Prothro at the University of North Carolina.Footnote 64 This survey uses the more modern ANES (American National Election Studies) sample design. Thus, while it is limited by the lack of a non-Southern comparison group, it does not face the limitations of the quota-controlled samples used in the previous surveys. This is the same survey used by Parker, who focused on the black sample. I utilized the white sample to address the questions stated earlier. I discuss the question wordings in the relevant sections.

Methodologically, my goal here was to estimate the relationship between veteran status and racial attitudes, controlling for other factors.Footnote 65 I opted to run regressions on the male sample only. I argue that this makes clear theoretical sense—while some women served in units like the Women's Army Corps, the battles of World War II were fought almost entirely by men—although it does have the methodological shortcoming of lowering the number of observations in the models. I also restricted the sample by age to focus on those who could have plausibly been veterans. To determine what age range to use, I looked at the age and veteran status cross-tabs. For the models using the 1946 data set, I analyzed only those individuals age 40 and below. For the 1948 data sets, I used age 45 as the cutoff. For the 1961 data set, I looked only at those between 38 and 65 to best assess World War II veterans. This, too, lowered the number of observations, but it also reduced the possibility that veteran status is simply capturing an age effect.

Education—necessarily controlled for because of sampling concerns in the 1940s data sets—takes on additional importance when studying veterans, especially in the later time period.Footnote 66 The 1961 cross-tabs are suggestive. In the white sample used here, 26 percent of respondents had some college experience, and 25 percent had served in the military. But among the 25 percent with military service, a much larger 39 percent had some college experience, compared with only 21 percent of nonveterans.Footnote 67 This is likely largely due to the effects of the Servicemen's Readjustment Act of 1944—the G.I. Bill—which substantially aided white veterans in attending college.Footnote 68

RESULTS: RACIAL LIBERALIZATION HYPOTHESIS

This section assesses the first hypothesis, that World War II led to a liberalization of white racial attitudes in the aggregate. If this is correct, we should see a liberal shift in racial attitudes, both prejudice and policy. I also examined subgroup variation related to region and size of place to further assess the aggregate trends.Footnote 69 I found that while there were slight liberal shifts in racial prejudice, this was largely not the case for policy attitudes. White opposition to federal anti-lynching legislation actually seems to have grown during the war, and there was little discernible change on the poll tax.

Racial Prejudice, 1943–1946

In 1944, the National Opinion Research Center (NORC) administered “Survey #1944-0225: Attitudes Toward Negroes,” a national survey of white attitudes.Footnote 70 The sample comprised 2,521 national white adults who were interviewed face to face. While other surveys asked a question here and there about race in the midst of other inquiries, this survey was entirely about race. The results provide a unique look at white attitudes in the middle of World War II. This particular survey made a number of people uncomfortable. In December 1944, a confidential report summarizing the results was sent to seventy-five people asking for comments on how it might be used in a constructive manner and whether it would be advisable to release the numbers into general distribution. Later, the results were in the process of being prepared for publication by the American Council on Race Relations, but the council was concerned about a preliminary release. “The danger of publishing such figures, without due caution and interpretation,” they argued, “lies in the fact that many persons reading the results of the poll would mistake figures published for actual facts.”Footnote 71

Six of the questions from this survey were repeated on a single occasion. While this is not an ideal number of data points from a contemporary perspective, it is a goldmine by the standards of 1940s survey research. This section compares the aggregate and regional numbers between t 1 and t 2 to offer some assessment of change over time. Assessing any potential shift from 1943 to 1944 might be of some inherent interest, but unfortunately it does not allow for a wartime and postwar comparison. The 1944 and 1946 comparison does offer this, and fortunately most of the questions were repeated at this point.

A good-living question (“Do you think Negroes have the same chance as white people to make a good living in this country?”) was previously asked in a November 1943 survey titled “Postwar Problems, Old Age Pension, Public Schools and Free Speech.”Footnote 72 This survey interviewed 2,560 national adults face to face. Five other questions were repeated in a May 1946 survey, titled “Minorities; United Nations.”Footnote 73 This survey interviewed 2,589 national adults face to face. There was a question about fair treatment (“Do you think most Negroes in the United States are being treated fairly or unfairly?”), jobs (“Do you think Negroes should have as good a chance as white people to get any kind of job, or do you think white people should have the first chance at any kind of job?”), blood (“As far as you know, is Negro blood the same as white blood, or is it different in some way?”), intelligence (“In general, do you think Negroes are as intelligent as white people—that is, can they learn just as well if they are given the same education?”), and having a black nurse (“If you were sick in a hospital, would it be all right with you if you had a Negro nurse, or wouldn't you like it?”). The blood question might seem strange at first, but it actually relates quite directly to the war effort: the Red Cross at this time segregated donations—storing black blood separately from white blood—even during total war.Footnote 74 Weights were constructed following Berinsky and Schickler's approach.Footnote 75

These questions provide different vantage points on attitudinal change during the war. The good-living and fair-treatment questions involve respondents making an assessment of conditions. As such, their meaning is more ambiguous. The objective answer is “no,” but increases in the “yes” answer during the war might reflect a perception that things are getting better, if not equitable. As such, these two questions are not ideal for testing the racial liberalization hypothesis, but are still of general historical interest. The jobs question, by contrast, is normative. It does not ask whether the respondent thinks African Americans have the same chance as white people to get a job, but rather whether they should have the same chance or not. As such, only an increase in the “yes” answer should be interpreted as a growth of racial liberalism. The questions about blood, intelligence, and having a black nurse tap more into general prejudice. The blood question, in particular, is an extreme case that taps into forms of biological racism common in the day. Here, too, an increase in affirmative answers should be taken as evidence of growing liberalism. Results should be interpreted with care, however, since it is not possible to look at the average of multiple polls, but simply two data points. As such, these results should be seen as suggestive rather than definitive.

Three prejudice measures are consistent with the racial liberalization hypothesis. Whites became more likely to say African Americans should have the same chance at a job, rising from 38 percent to 45 percent. Northern support for equal opportunity increased from 46 percent to 52 percent; Southern support increased from 15 percent to 25 percent. Whites also became more likely to say black blood was the same, with the number increasing from 31 percent to 40 percent. The number saying it was different was effectively constant, moving from 35 percent to 33 percent. However, “don't know” responses dropped from 34 percent to 28 percent. In the North, whites moved from 34 percent to 42 percent saying it was the same. In the South, whites moved from only 20 percent saying it was the same to 32 percent saying so. Finally, whites became more likely—moving from 45 to 54 percent—to say black people were as intelligent as white people. However, this shift is almost entirely non-Southern. In the South, 30 percent of whites said yes in 1944 compared to 31 percent in 1946. In the North, however, this number increased from 50 percent in 1944 to 61 percent in 1946.

However, one prejudice measure is not consistent with the racial liberalization hypothesis. The question about having a black nurse actually saw a slight decrease in support, from 50 percent of whites saying they would be okay with this in 1944 to 46 percent in 1946. This seems primarily driven by Northern whites, where support dropped from 56 percent to 51 percent, while moving only from 32 percent to 30 percent in the South.

Finally, white opinion seems relatively constant for the two questions asking for an assessment of social conditions. The percentage of whites who said they thought African Americans had the same chance as whites to make a good living was roughly constant from 1943 to 1944, increasing from 52 percent to 54 percent.Footnote 76 White assessments of whether African Americans were being treated fairly likewise remained constant from 1944 to 1946, at 63 percent in both years.

A comparison of rural Southerners and urban residents in the Northeast also illuminates relevant subgroup differences. In many cases, the decreases in racial prejudice seem to reflect rural Southern whites going from “extremely prejudiced” to “slightly less prejudiced.” While only 10 percent of whites in the most rural areas of the South expressed support for equal job opportunities in 1944, by 1946 this number had risen to 25 percent—a sizable increase percentage-wise, albeit still a minority viewpoint. Similarly, notions among this group of white Southerners that black blood is biologically the same as white blood increased from 19 percent in 1944 to 38 percent in 1946. The changes in the urban Northeast were much smaller.

Overall, there is some evidence for the racial liberalization hypothesis with respect to the racial prejudice measures, although there was a conservative shift on the nurse question. There are, however, clear limitations to this analysis. Two data points are less than ideal, especially since there is no clear before and after. Having a prewar comparison case would be preferable. Fortunately, the two policy issues that follow are better in this regard.

Policy I: Federal Anti-Lynching Legislation, 1937–1950

I next turn to two policy areas with more available data points: anti-lynching legislation and abolition of the poll tax. I start with an assessment of changing white attitudes on federal intervention in state lynching cases. Lynching was raised as a national political issue by civil rights organizations like the NAACP. As William Hastie and Thurgood Marshall argued during the war, “the recent outbreaks of mob violence again emphasize the fact that only Federal action will free us from lynchings and the threat of lynching.”Footnote 77 Federal anti-lynching legislation was often proposed, but never successfully passed in the Senate (although it did pass in the House of Representatives). Such legislation was a challenge to Roosevelt's congressional New Deal alliance. Roosevelt and his congressional supporters “tailored New Deal legislation to southern preferences,” according to Ira Katznelson et al., trading maintenance of Southern Jim Crow for Southern support for New Deal economic legislation. This meant that not even “the most heinous aspects of regional repression, such as lynching, [could be] be brought under the rule of law.”Footnote 78 Yet for many politicians outside the South, black migration meant that “black political power was becoming an unavoidable reality.”Footnote 79 Anti-lynching legislation soon became more than the sum of its parts, effectively serving as a symbol for racial conservatives of the meddling of Northern liberals in the white South's affairs.

To assess white attitudes toward federal anti-lynching legislation, I looked at Gallup questions about federal intervention in state lynching cases, which were asked before and after—although, interestingly, not during—the war. While Schickler discarded the “don't know” responses to create dichotomous response categories in his analysis of the prewar lynching questions, I decided to leave the “don't know” responses in to allow for a valid third category of uncertainty. As will be discussed momentarily, this helps to assess prewar and postwar shifts in the opposition category. I divided opinion in each survey into support, opposition, and don't know. I used the best possible survey weight to correct for the biases of the sampling procedure.Footnote 80

A word of caution is in order regarding question wordings. While the analysis presented here is consistent with evidence regarding the poll tax (which provides a useful robustness check, as there is no substantial variation in question wording there), Gallup's questions about lynching are indicative of some of the weaknesses of early survey research. The questions can basically be divided into four groups. The first three questions, all from 1937, asked quite simply whether Congress should pass a law making lynching a federal crime. The next three questions, asked from 1937 to 1940, asked whether the federal government should have the authority to fine and imprison local authorities who do not protect against a lynch mob, which is a much more specific and severe description. In the postwar period, from 1947 to 1950, Gallup returned to a more general question, asking, with only very slight variations, something along the lines of, “At present, state governments deal with most crimes committed in their own state. In the case of a lynching[,] do you think the Federal Government should have the right to step in and deal with the crime—or do you think this should be left entirely to the state government?” There is one outlier in the question wording, however. The 1947 question asks whether the federal government should be able to step in only “if the State Government doesn't deal with it justly.” This concluding qualifier (“justly”) leaves much more room for interpretation, and possibly suggests a less all-encompassing policy. I consider this question a third category, and the remaining 1948–1950 questions without the qualifier as the fourth category.

Because of these differences in question wording, caution is needed in analyzing trends over time. Although the first (1937) and fourth (1948–1950) groups of questions share some similarities (they both ask whether the federal government should have authority over state lynching cases, without making reference to specific penalties), the 1937 questions do not refer directly to state action. And while the 1947 question is similar to the 1948–1950 questions in many ways, the ending to the question is much more ambiguous, perhaps suggesting a weaker policy (in turn opening up the possibility of more expressed support). This sort of limitation, however, is an inherent part of the data, and it reflects the difficulties of working with surveys from this era. To better highlight variation in wording, I used different markers in the figures for different categories of questions.

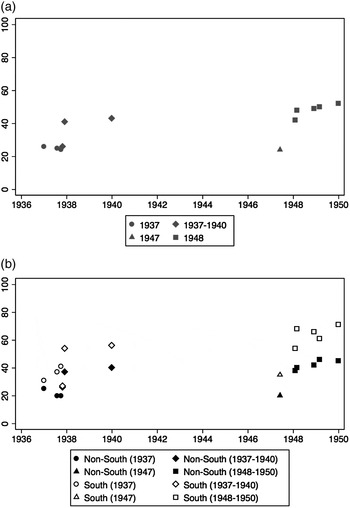

Figure 1 plots trends in support. For the first three data points in 1937, national white support for federal intervention ranges from 59 to 62 percent (the numbers are 59 to 67 percent in the North, compared with 38 to 53 percent in the South). For the next three, when phrasing about punishing local officials is introduced from November 1937 to January 1940, support ranges from 42 to 60 percent (46 to 60 percent in the North, compared with 29 to 58 percent in the South), with the highest figure coinciding with the most minimalist version of this style of question. Postwar, from February 1948 until January 1950 national white support for federal intervention ranges from 38 to 43 percent (42 to 47 percent in the North, compared with 23 to 27 percent in the South).Footnote 81

Fig. 1. Percent Supporting Federal Anti-Lynching Legislation.

Precise causal inference is impossible to draw from such data, but a few general statements seem consistent with the results. The polling evidence certainly provides no support for the idea that the war led to an increase in support for federal intervention in state lynching cases. It is possible that there was simply no effect of the war (the apparent trend could be random fluctuations, question wording effects, etc.). If anything, there seems to have been an increase in racially conservative opposition. Figure 2 plots the percentage of whites that opposed federal intervention from 1937 until 1950. Before the war, opposition never rose above 43 percent overall, 40 percent in the North, and 56 percent in the South, while “don't know” responses were sometimes as high as 17 to 20 percent.Footnote 82 By January 1950, however, opposition to federal intervention was up to 52 percent overall—a majority—and at a new height of 71 percent in the South. This seems to have been primarily the result of white indecision evolving into a hardened states' rights position, although there appears to have been a slight decline in active support for federal intervention as well.

Fig. 2. Percent Opposing Federal Anti-Lynching Legislation.

Comparing Southerners in the most rural areas to northeastern residents in the most urban ones is again revealing, but in a slightly different manner than it was for measures of racial prejudice. In January 1940, 82 percent of whites in the most populous urban areas in the Northeast expressed support for a congressional anti-lynching bill. Between February 1948 and January 1950, support for federal intervention in state lynching cases ranged from 47 to 59 percent across five different surveys. For whites in the most rural Southern areas, support stood at 27 percent in January 1940, then ranged from 14 to 21 percent in the five surveys conducted between February 1948 and January 1950. The decline in support, then, actually seems, if anything, especially concentrated in the urban Northeast, where support dropped from nearly universal to slightly majoritarian (and, in one case, just a plurality). However, there was less room for a decrease in Southern opinion, since it was already much more opposed. This does not mean the urban Northeast was not more supportive of civil rights liberalism—it was. However, it does highlight the extent to which liberalism was “limited” at this time by mass preferences. Rather than being a window where policy attitudes could become more accommodating, the war seems to have solidified the prospect of such measures and increased skepticism. Anti-lynching legislation was never enacted and eventually fell off the agenda.

So, what might be behind the apparent shift in attitudes? Several factors besides the war cannot be ruled out as possibilities. The number of lynchings had declined since the mid-1930s, which might have led more white respondents to think lynching would go away on its own without federal action.Footnote 83 Another possibility is that it might reflect the NAACP's changing policy focus. By the late 1940s, the organization's civil rights agenda included a wide range of issues beyond lynching, which might have decreased the issue's salience.Footnote 84 An alternate interpretation of this shift in the NAACP's agenda might be that the lynching question came to represent something bigger than lynching per se. Respondents could have perceived that the growth of black militancy during the war was increasing the prospect of other policy changes, with anti-lynching legislation serving as a precedent. It is also possible that a genuine, if unmeasurable, wartime liberalization might have been reversed by developments in the latter half of the 1940s such as the Truman civil rights committee (established in December 1946 and report released in October 1947) or the Dixiecrat movement in 1948.Footnote 85 Whatever the interpretation, the trends presented here can still serve as an important reference point for accounts of the war and racial attitudes. At the very least, while acknowledging a potentially more complicated story, the racial liberalization argument does not seem consistent with the lynching data.

Policy II: Abolition of the Poll Tax, 1940–1949

The second policy issue that was especially salient prewar was the poll tax. To assess shifts in white attitudes on the poll tax, I used Gallup questions about whether the tax should be abolished. This question was asked once in 1940, then four more times in the late 1940s. Like the lynching questions, however, it was never asked during the war itself. The question wording, fortunately, was very similar over time. “Some Southern states require every voter to pay a poll tax amounting to about a dollar a year before they can vote,” the question began. The respondent is then asked whether they think “these poll taxes” should be “abolished” or “done away with” (the specific phrase at the end is the only part that varies over time). The prewar survey allowed respondents to distinguish between “YES!” and “Yes” (also “NO!” and “No”), which is how they articulated preference intensity. However, the postwar surveys simply offered “Yes” and “No” responses, so I collapsed the 1940 survey into simple “YES!”/“Yes” and “NO!”/“No” categories to allow for comparison. All surveys also allowed the respondents to declare “no opinion,” which I again chose to keep in my analysis. The 1940 survey weights were constructed by Berinsky and Schickler, and I used their code to reproduce it (again altering their decision to drop respondents who offered no opinion on the poll tax question). For the postwar questions, I constructed my own weights that correspond to Berinsky and Schickler's preferred education weights (“eduWhites”) based on their method.

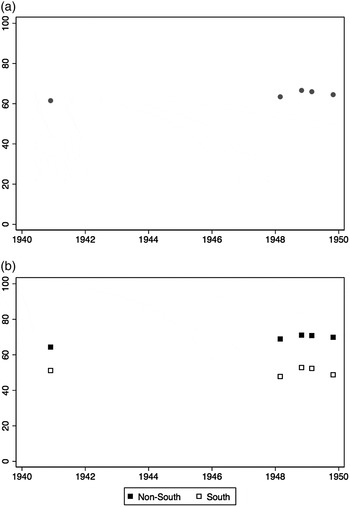

Figure 3 plots white support for abolishing the poll tax. In December 1940—a year before the United States entered the Second World War—national white attitudes stood at 61 percent wanting to overturn poll taxes, 27 percent wanting to keep them, and 12 percent not offering an opinion. In the South, 51 percent of whites supported getting rid of poll taxes, 40 percent wanted to keep them, and 9 percent did not express an opinion. Jumping forward to the postwar questions, national white support ranged from 63 to 66 percent, and among white Southerners, it ranged from 48 to 53 percent. The evidence, then, points to an increase in support of 2 to 5 percentage points in aggregate white opinion. This is a slight shift, although it is difficult to discern the extent to which it represents a small but real change rather than a slight fluctuation within the margin of sampling error.

Fig. 3. Percent Supporting Abolition of the Poll Tax.

There are again some concerns regarding interpretation that merit consideration. The poll tax was a complicated issue in the context of 1940s racial politics. Poll tax opponents in the 1940s tried to frame the issue as a suffrage restriction that hurt poor whites. By focusing on the single issue of the poll tax, they hoped to separate the issue from the broader struggle for black voting rights. Roosevelt himself viewed reforming “Polltaxia” as part of his broader effort in the late 1930s to purge Southern conservatives in his party, which was motivated by a range of issues beyond race. After the United States entered World War II, some advocates used the ideological logic of the war to compare the poll tax's disenfranchisement with elections in fascist Europe. Insomuch as the poll tax was framed by political elites like Roosevelt and national advocacy organizations as a burden on poor whites, using it as a test of racial policy is a bit difficult. That said, it is certainly true that supporters of the poll tax in the South saw it as an important tool in maintaining white supremacy. Some non-Southern liberal Democrats likewise described it in similar terms. Congressman Arthur Mitchell, for example, said abolishing the poll tax would “eventually aid in wiping out the disenfranchisement of Negroes … in the Southern states” (for him, a welcome development).Footnote 86 Overall, it would be ill-advised to look only at the poll tax as a measure of racial policy liberalism. However, in conjunction with an analysis of anti-lynching legislation, which was always more explicitly racialized, looking at the relatively small shifts in attitudes toward the poll tax helps fill in the broader picture. The absence of major attitudinal change on the poll tax is not consistent with the racial liberalization argument, at least in its stronger forms.

Summary: Racial Liberalization Hypothesis

This section demonstrates that, for the most part, white attitudes were not broadly liberalized on race and civil rights as a result of World War II. There is some evidence of a decrease in certain (although not all) measures of white racial prejudice. However, this is counterbalanced by evidence that, if anything, white opposition to federal anti-lynching legislation actually increased. Although the shifts in prejudice should not be totally discounted, the lynching numbers highlight an interesting distinction between measures of prejudice and measures of policy preferences. As such, this section raises doubts about scholarship that has simply assumed, without analyzing the relevant data, that the war had a liberalizing impact on white racial attitudes. This perspective—especially in its more declarative forms—is not supported by the available survey evidence.

It is possible, of course, that some attitudinal changes were not immediate. For example, there might have been a “World War II generation” that experienced the war during their “impressionable years” who came to hold different views on race later in life. This is difficult to identify in the data sets analyzed here, although the veterans section that follows provides one relevant vantage point on individuals whose impressionable years were defined by direct participation in the war. It is also possible that the meaning of “racial liberalism” itself shifted over time, and as such, the proper test of racial liberalization might similarly have shifted. For instance, this article treats attitudes toward federal intervention in state lynching cases as a key measure of racial liberalism. Yet the number of lynchings had fallen significantly by the late 1930s, and the agenda of the NAACP was moving in a different direction.Footnote 87 It is worth considering what trends over time might look like had questions been asked before and after the war about issues like employment discrimination and housing policy, which were less sectional in nature.Footnote 88 Several other issues also cannot be fully resolved, including sheer data limitations and possible variation in survey response during the decade. While acknowledging such limitations, I argue that the best account of the war's impact on white racial attitudes must be consistent with the evidence that does exist.Footnote 89

RESULTS: RACIAL LIBERALIZATION HYPOTHESIS FOR VETERANS

This section assesses the second hypothesis, that white veterans of World War II were more racially liberal in the war's aftermath than their nonveteran counterparts. Using two data sets from the earlier analysis of aggregate white racial prejudice, as well as a new data set asking about military integration, I demonstrate that white veterans were not less racially prejudiced in the war's immediate aftermath. They were not distinguishable on general prejudice measures, and they were likewise not more willing to support an integrated military. They were, however, more likely to support federal anti-lynching legislation. Shifting focus to 1961—and bringing in the white Southern sample of the Negro Political Participation Study—I demonstrate that white veterans in the South were not distinguishable on attitudes toward segregation and the sit-in movement. However, they were more supportive of black voting rights than nonveterans.

Postwar: Late 1940s

The 1946 “Minorities; United Nations” NORC survey used earlier contains a wide range of questions about racial prejudice. Fortunately, it also identifies veteran status. For dependent variables, I used five of the racial prejudice questions from the last section (whether African Americans are being treated fairly, whether they should have the same chance at a job, whether black blood is biologically the same as white blood, whether black people are as innately intelligent as white people, and whether the respondent would tolerate having a black nurse). Each variable was dichotomized so that discriminatory positions are coded as 1 and more egalitarian positions are coded as 0.

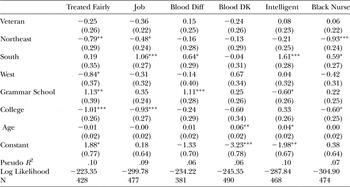

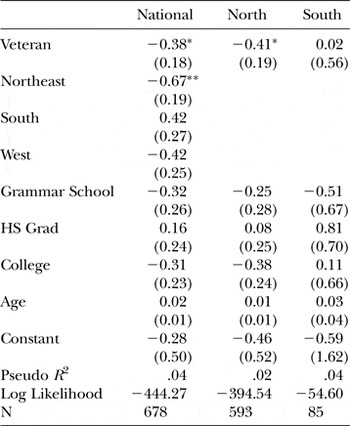

Results of a series of logistic regression models are presented in Table 1. Overall, the results are not consistent with the racial liberalization hypothesis for veterans. Controlling for region, education, and age, World War II veterans were perhaps less likely to say white people should get the first chance at a job, but the marginal effect of 9 percentage points is only significant at the .10 level. This might be reasonable since N = 477, but if the conventional .05 significance level is maintained, the effect does not meet the criteria for statistical significance. Otherwise, there is no distinction between veterans and nonveterans on an array of issues.

Table 1. Anti-Black Prejudice, 1946

Notes: Standard errors in parentheses. ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05.

I also examined attitudes toward an integrated military. In 1948, Gallup used a split form to ask slight variations on a question about military integration. Those receiving Form K of the survey were asked, “Would you favor or oppose having Negro and white troops throughout the U.S. Armed Services live and work together—or should they be separated as they are now?” Those receiving Form T were asked, “It has been suggested that white and colored men serve together throughout the U.S. Armed Services—that is, live and work in the same units. Do you think this is a good idea or a poor idea?” These variables were dichotomized so that opposition is coded as 1 and support for integration is coded as 0.

I again used logistic regression to estimate the relationship between opinion on military integration and World War II veteran status, controlling for region, education, and age. Results are presented in Table 2. There is no statistical relationship between being a veteran and attitudes toward military integration. This result is consistent for both versions of the question. Given the salience of the military integration policy debate in the postwar period—and the ideological tension between a war for democracy waged by a segregated military—this null result is quite striking.

Table 2. Integrating the Military, 1948

Notes: Standard errors in parentheses. ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05.

Finally, some of the postwar lynching questions were part of surveys that asked whether respondents served in World War II. Here, I examine a 1948 question asking respondents, “At present, state governments deal with most crimes committed in their own states. In the case of a lynching, do you think the United States (Federal) Government should have the right to step in and deal with the crime—or do you think this should be left entirely to the state government?” The variable was dichotomized so that leaving lynching cases to the states is coded as 1 and allowing the federal government to intervene is coded as 0.

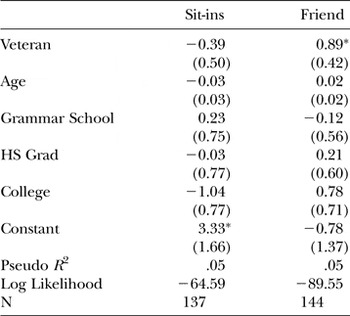

I again used logistic regression to estimate the relationship between opinion on federal intervention in state lynching cases and World War II veteran status, controlling for region, education, and age. Results are presented in Table 3. These results provide the strongest positive evidence supporting the hypothesis that white veterans were liberalized on race. The “National” model column shows that veteran status has a statistically significant relationship with attitudes toward anti-lynching legislation. Calculating marginal effects, white veterans were 9 percentage points less likely to take the states' rights position, relative to the federal intervention choice. The “North” and “South” models show this to be an entirely non-Southern effect. If the model is estimated using only Southern respondents, the veteran variable is not significant. However, if it is estimated using only non-Southern respondents, the effect of military service is slightly larger than in the full model (10 percentage points in this case).

Table 3. Lynching, 1948

Notes: Standard errors in parentheses. **p < 0.001, *p < 0.05.

The Civil Rights Era: Early 1960s

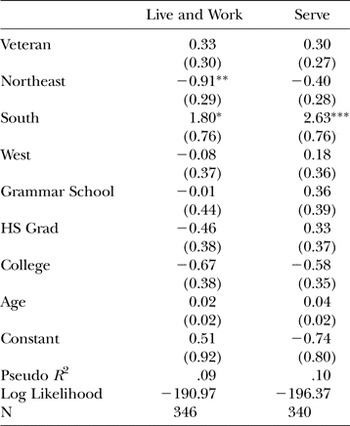

While the immediate impact of military service on racial attitudes is interesting, the longer-term impact of military service on later racial attitudes also merits examination, especially in the era when civil rights politics were most primed. This analysis also allows me to relate this project more directly to Parker's work on the attitudinal and behavioral impact of black veterans' military service. Relying on the white sample of the 1961 Negro Political Participation Study, I used the following questions as dependent variables: the respondent's assessment of how many white people in the South favor racial segregation; whether the respondent themselves favors “integration, strict segregation, or something in between”; their agreement with the statement, “colored people ought to be allowed to vote”; assessment of the sit-in movement (“that is, some of the young colored people going into stores, and sitting down at lunch counters, and refusing to leave until they are served”); their agreement with the statement, “Demonstrations to protest integration of schools are a good idea, even if a few people have to get hurt”; whether they have ever “ever known a colored person well enough that you would talk to him as a friend”; and whether they agree that “colored people are all alike.”

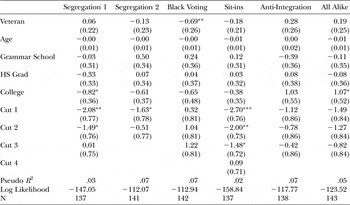

I estimated regression models where opinion is a function of veteran status, as well as age and educational attainment. The sample is restricted to Southern whites by default. As previously noted, I also restricted it to those men between the ages of 38 and 65. For dependent variables with multiple, ordered response categories, I estimated ordered probit models. Variables were coded so that higher values are more racially conservative. For the dichotomous question about friendship—as well as an alternate coding of the sit-ins variable—I used logistic regression. To aid in interpretation, I calculated changes in probabilities for theoretically relevant shifts, as well as the average change, for the veteran variable in the ordered probit models. I also calculated the marginal effect of moving from 0 to 1 on the veteran variable (i.e., moving from not being a veteran to being a veteran) for the logistic regression models.

Results are presented in Tables 4 and 5. The strongest support for the racial liberalization hypothesis for veterans is found in the model assessing attitudes on black voting rights. The coefficient on the veteran variable is statistically significant. When the changes in probabilities are calculated, the evidence largely points to differences in preference intensity, rather than sheer differences of opinion. Southern whites with military backgrounds were 21 percentage points more likely than those without military backgrounds to offer strong support, relative to the weaker support option. However, the other categorical shifts are much smaller. The overall average change associated with military service is 11 percentage points. For this issue, at least, there is support for the racial liberalization hypothesis for veterans.Footnote 90 White veterans were also 19 percentage points more likely than nonveterans to say they had a black friend. Although the “black friend” trope is a cliché one, it lends some support to the idea that white veterans' relative moderation, at least on some issues, was partly fueled by contact.

Table 4. Negro Political Participation Study White Sample, Logit Models, 1961

Notes: Southern sample. Standard errors in parentheses. *p < 0.05.

Table 5. Negro Political Participation Study White Sample, Ordered Probit Models, 1961

Notes: Southern sample. Standard errors in parentheses. ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05.

However, there is no difference whatsoever between veterans and nonveterans on assessments of the sit-in protests or general attitudes toward segregation. This is a clear rebuke of the racial liberalization hypothesis. Segregation was at the core of the Southern racial status quo, and military service seems to have had no moderating effect on how Southern white men felt about the issue. Similarly, the sit-in movement was a critical aspect of the 1960s civil rights movement, and military service likewise seems to have had no impact on white assessments of it.Footnote 91

Summary: Racial Liberalization Hypothesis for Veterans

This section provides evidence that white veterans' military service corresponded with more moderate racial attitudes on some issues, but not others. White veterans overall were less likely to oppose federal intervention in state lynching cases in 1948, although this seems to have been concentrated among non-Southerners. White veterans in the South offered stronger support for black voting rights in 1961. However, they did not evince less racial prejudice than nonveterans in the war's immediate aftermath, and by 1961 Southern white veterans were not distinguishable from white Southerners as a whole on questions of segregation. On the one hand, then, veterans seem to have liberalized on at least some of these more difficult questions of policy, whereas this was not the case for the white mass public as a whole. On the other hand, this moderation did not extend to broader claims about racial integration. The white veterans analyzed in the 1960s were just as supportive of Jim Crow segregation as Southern whites who did not serve, and they were not any more sympathetic to the sit-in movement.

Mechanisms are difficult to tease out. The exposure to more egalitarian cultures argument is a theoretically appealing one, but it is difficult to empirically test given the available data.Footnote 92 Another possibility is the contact hypothesis, as white veterans in the South in 1961 were much more likely to report they had a black friend than nonveterans.Footnote 93 Of course, the war's effects on contact between black men and white men were complex. On the home front, black soldiers stationed in Southern training centers came into contact with both white soldiers and nonmilitary whites. Black men and white men also were more likely to work together in the defense industry than they had been before the war. This increased contact certainly did not lead easily to toleration and integration, as race riots and other incidents of racial violence on the home front make clear.Footnote 94 While the exact mechanism is difficult to fully identify, these results nonetheless contribute to scholarly accounts of the war's effects on American racial politics, and they complement research about the effects of military service on black veterans.

CONCLUSION