Introduction

In March 2023, Coinbase, one of the world’s largest cryptocurrency trading platforms, received notice that they were in trouble. The US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) informed Coinbase that numerous aspects of their products and services were in violation of securities law, setting the stage for enforcement action.Footnote 1 Coinbase was furious. The crypto giant complained that they had been seeking regulatory guidance from the SEC for years, including “dozens of meetings and hundreds of hours of communications…”Footnote 2 From their perspective, the SEC had failed to honor its previous commitments to engage with the cryptocurrency industry and provide clarity on how to comply with its rulebook.Footnote 3 Chief Legal Counsel Paul Grewal, shedding standard conservative approaches to corporate communication, was explicit: “We have repeatedly asked the SEC for its own views on how securities laws might apply to Coinbase and our industry. And to be candid we have mostly gotten silence in response.”Footnote 4

The SEC’s apparent hesitancy to clarify the regulation of cryptocurrencies and other digital assets is puzzling. We normally expect—and have been told by previous literature—that public agencies are eager to regulate, constantly seeking to expand their turf and responsibilities to govern corners of society outside the state’s purview.Footnote 5 The puzzle only deepens when we look at the global landscape, where there are substantial cross-national differences in the level of regulatory clarity surrounding cryptocurrencies.Footnote 6 Some countries have elaborate frameworks of crypto market regulation and governance, while other states have consciously eschewed market recognition, standardization, and control. This is true even across countries with comparable levels of state capacity and financial market development. What explains these differences? And, more broadly, what drives the development of market regulation across time?

To answer these questions, we present a new conceptual framework centered around the sociological concept of legibility. This term, originally put forward by James C. Scott, traditionally refers to the methods by which the state makes segments of society legible as a means of controlling them.Footnote 7 Scott originally had Southeast Asian peoples in mind, but the concept is equally useful, we contend, for understanding political dynamics between regulators and market actors. Political economists normally view such issues through the lens of interest group theory, examining how the private sector and other segments of society influence regulations in their favor.Footnote 8 Legibility involves more fundamental questions about whether the state desires to impose such rules in the first place. Further, it allows us to explore why private actors might seek to make their activity more legible (and thus controllable) to the state or take steps to keep their activity illegible as a means of escaping regulation.

We conceptualize these dynamics as a balance between two variables: market demand for regulation and state supply. The demand side represents the constellation of competing interests amongst market actors over whether to make their activity more or less legible to the state. The supply side refers to the state’s preference to make markets legible through the creation of rules or purposefully allow illegible markets to operate untethered. Together, demand- and supply-side conditions will determine the extent to which markets are legible at any one moment in time. At one extreme, where both demand and supply are low, markets are purely illegible. In the opposite scenario, where both market actors and the state desire regulation, collaborative legibility occurs, which is not necessarily harmonious but involves willing participation by both sides. If supply is high but demand low, markets are in a state of contested legibility in which private actors resist the state’s attempts to render their activity legible through rulemaking. If, in contrast, market actors demand legibility but state supply is low, there is contested illegibility in which the former challenge the latter’s unwillingness to regulate.

This framework is utilized to explain the development of cryptocurrency regulation in the EU, US, and Japan (an additional case study on the UK is contained within an appendix). We examine how changes in supply and demand-side conditions combined to push markets between different stages of legibility, each of which corresponds to varying levels of regulatory clarity. Every market analyzed began in states of pure illegibility, in which small groups of cryptocurrency enthusiasts traded amongst themselves with neither demand for, nor state supply of, legibility. In the US and UK, increasing demand for regulation as a means of legitimizing the industry was met with resistance from the state, leading to prolonged periods of contested illegibility. The UK would eventually succumb to private market pressure for legibility, resulting in the formal recognition of crypto assets as a regulated activity in 2023. US regulators, in contrast, began engaging in what is referred to as “regulation by enforcement,” bringing lawsuits against industry players rather than standardizing market practices. As a result, the US still lacks clarity on the classification of cryptocurrencies and their regulatory status. In stark contrast, authorities in the EU and Japan sought to supply legibility at a relatively early stage. This growth in state supply was matched by increased market demand in Japan, leading quickly to collaborative legibility. In the EU, resistance to state intervention prompted a brief period of contested legibility. But this gave way to a rise in market demand as a means of legitimization, leading to collaborative legibility and, in turn, the world’s most comprehensive regulatory regime for crypto assets. These analyses demonstrate how divergent patterns of change in market demand for, and state supply of, legibility help explain not just cross-national differences in regulation, but also variation in the development of market governance across time.

By performing these tasks, this article improves our understanding of regulation and the political economy of finance. Existing theories tend to assume that states, private actors, and other societal groups are interested in shaping market rules. They assume, in other words, that all actors share a desire to make markets legible but disagree on the details. The framework outlined here relaxes this assumption to capture situations in which private actors and/or states have motivations to avoid legibility altogether. It is only by considering this more complex set of circumstances that we can fully understand the historical progression of market regulation not just in cryptocurrencies but also a wide variety of traditional asset classes.

This article also advances the literature on legibility and provides a novel application of the concept to market governance.Footnote 9 Following Scott’s original focus on the methods by which states make societal groups legible, sociologists have expanded the theory to consider scenarios where states may have strategic incentives to be “standoffish” or keep certain groups illegible to avoid undertaking responsibility for their wellbeing.Footnote 10 Scholars have also noted how societal groups may benefit from, and push states to, make them legible.Footnote 11 The framework outlined here combines these and other insights to provide a comprehensive mapping of (il)legibility preferences and their combined impact on financial markets.

This exercise is highly relevant to pressing regulatory concerns. Prolonged periods of contested legibility may, for example, delay the introduction of regulations that protect consumers or mitigate threats to financial stability. Contested illegibility may have similar effects while also stunting the development of legitimate markets for crypto assets. Such delays can also create pockets of vulnerability in the international financial system, where lack of regulation allows misconduct and financial crime to thrive. By mapping patterns of contestation over legibility, this paper takes a first step toward better understanding these developments. Further, it contributes to our knowledge of how disruptive financial innovations induce continuous patterns of (il)legibility that shape the contours of economic markets.

Existing perspectives on market governance

From the earliest beginnings of bond trading in 12th century Venice, debates have raged over the appropriate level of state involvement in the governance of private markets.Footnote 12 Contemporary views in favor of such involvement are rooted in public interest theory, which contends that government regulation can help correct market failures and mitigate negative externalities.Footnote 13 This perspective implies that state regulation is driven by a desire to protect the public, an assumption challenged by theories of regulatory capture.Footnote 14 The latter school of thought observes that private industry possesses a “demand” for regulations that benefit them commercially, and thus seek to influence their design. Later research has explored how this demand may vary amongst industry groups, providing firms with incentives to influence public regulation as a means of obtaining strategic advantages over their competitors.Footnote 15 One common observation is that higher levels of regulation tend to favor large incumbents at the expense of smaller entrants.Footnote 16 But regulations can also favor entrants by, for example, eliminating barriers to commercially-valuable information or promoting rules that facilitate the creation of new networks.Footnote 17 In other contexts, private industry may seek to self-regulate to pre-empt and limit formal oversight by the state.Footnote 18 Less understood are situations where industry actors seek state regulation as a means of legitimizing their unregulated activities.Footnote 19

Nor do we possess a comprehensive understanding of why the state may refuse to “supply” such legitimatization through rulemaking. From the early 20th century onwards, states increasingly outsourced regulation to delegated independent agencies such as the SEC.Footnote 20 As bureaucracies, these agencies are expected to seek constant expansion of their scope, roles, and powers as a means of guaranteeing their continued survival.Footnote 21 They may in turn outsource aspects of rulemaking and oversight to market self-regulatory organizations (SROs) like FINRA (Financial Industry Regulatory Authority) to, inter alia, save costs and benefit from private industry’s expertise.Footnote 22 But such arrangements nevertheless represent an active decision to (indirectly) oversee private markets, and are usually couched within rule regimes that govern the behavior of SROs and provide regulators with checks on their powers.Footnote 23 They are, in other words, another method of governing (and, in turn, validating and making legible) private markets. What is more extreme—and under-researched—is hesitating to govern unregulated markets by any means.

More generally, we lack a sufficient understanding of how the interaction of these demand and supply factors impact the operation and development of private markets. Theories of interest groups tend to assume the state is a willing regulator. Theories focused on the state’s preferences, in turn, assume that private firms are interested in shaping rules. What the literature overlooks, we contend, is that there are numerous scenarios in which one or both sides possess incentives to avoid the conversation altogether. Phrased differently, there are variations in the demand for and supply of legibility across markets. By analyzing the interaction of these variables, we can better explain differences in market regulation that confound existing theories. Further, this approach produces ideal type states that capture distinct stages of market development, thereby allowing us to map changes in market governance across time. It is to these tasks that we now turn.

Explaining market legibility

Legibility was originally conceived as the methods by which the state seeks to standardize, and, in turn, more effectively control society.Footnote 24 These methods include drawing land borders, mandating official languages, and even recognizing legal surnames.Footnote 25 Later work challenged the notion that legibility is a purely coercive state-driven act, noting that some societal groups may actively seek to be “seen” by the state to, for example, make property claims.Footnote 26 Relatedly, the state may purposefully avoid such recognition to sidestep responsibility or political challenges.Footnote 27 Thus legibility is not a theory of politics or method of governance but rather a characteristic of state-society relations. It describes the extent to which some aspect of society has been made legible to the state through standardization.

We define market legibility as the extent to which the state has standardized the design and operation of a particular market. Standardization refers to the creation of formal market rules that are readable by the state and may be accompanied by regular monitoring and enforcement. States may create these rules themselves or enlist the assistance of intermediaries.Footnote 28 Regardless, these rules increase the legibility of markets and, in so doing, afford them some level of state recognition. Note, however, that legibility is not equivalent to acceptance. Much contemporary financial regulation is dedicated to defining in great detail what the state deems unacceptable.Footnote 29 This too, is an act of legibility, one that recognizes the existence of illicit markets and makes states responsible for their prevention. Illegible markets, in contrast, are formally unrecognized. The state has not, in other words, drawn the administrative boundaries of such markets and taken a view on their acceptability.

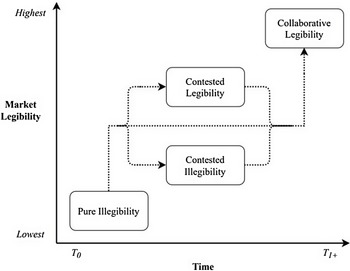

We contend that demand and supply variables will determine ideal type “states” of market legibility (Figure 1). The demand side represents the constellation of competing interests amongst market actors over whether to seek legibility. Markets actors may disagree on this topic for various reasons, including their relative size and market share; dependence on already regulated markets; the stock of available technologies and organizational resources; and exposure to reputational risk.Footnote 30 As has been documented in the literature, the constellation of market demand in the cryptocurrency domain is shaped by evolutions in, and the distribution of power between, the corporate infrastructures and organizational forms (centralized finance (CeFi), decentralized finance (DeFi), hybrid Ce-DeFi, and so forth) that produce cryptocurrencies and the technical differences between them.Footnote 31

Figure 1. Varieties of market legibility.

The supply side captures the state’s preference to make markets legible through standardization or allow illegible markets to operate untethered. There may be situations where different components of the state disagree on the desirability of making a particular market legible. We simplify here by focusing on the state’s aggregate preferences. Numerous factors are expected to impact these preferences, including the risk of negative externalities for which the state might be blamed and the availability of alternative approaches to rulemaking (e.g., non-standardizing enforcement actions). These factors will vary, and measuring their unique causal effects is beyond the scope of one article. Therefore, we simplify by applying a binary measure to capture situations where aggregate demand and supply are low or high.

Where both demand and supply are low, markets are in a state of pure illegibility. In these circumstances, market actors benefit from operating outside the confines of the state and may have commercial and/or ideological incentives to reject standardization.Footnote 32 The state, in turn, has little incentive to supply such standardization against markets actors’ wishes. This may be because the state does not know the market exists. Alternatively, the state may be aware of its existence but resist engaging in standardization to preserve its limited administrative resources and/or avoid the subsequent responsibility to enforce those standards.Footnote 33

The opposite scenario is collaborative legibility, where both market demand for, and state supply of, legibility is high. This describes most regulated markets, where there is general consensus that the benefits of legibility outweigh its costs. Such markets are collaborative in the sense that both the state and market actors are willing participants in the standardization process. This does not necessarily equate to a harmonious relationship, as there may be intense disagreements over what that standardization should entail. But there is consensus that making the market legible via state rulemaking is fundamentally desirable. Both collaborative legibility and pure illegibility are stable equilibriums that may persist for extended periods of time.

Less stable are situations where supply and demand factors diverge. If state supply is high but market demand is low, contested legibility occurs. Here the state desires to supply legibility as a means of pulling the market into its administrative orbit. Market actors, in contrast, have little or no interest in such standardization. The latter may resist participating in this process or engage in purposeful tactics to keep the market illegible, such as developing novel market mechanisms that perplex regulators and are incompatible with existing state legal frameworks. If, in contrast, market actors demand legibility but state supply is low, we observe contested illegibility. Here the state is “standoffish,” refusing or resisting to engage in standardization despite calls from market actors for regulation.Footnote 34 This may also involve the state imposing enforcement actions that penalize firms but do not provide clarity (i.e., “regulation by enforcement”). In this setting, market actors are contesting the illegibility of their activities, seeking state rules and the validation they afford.

Historical patterns of market legibility

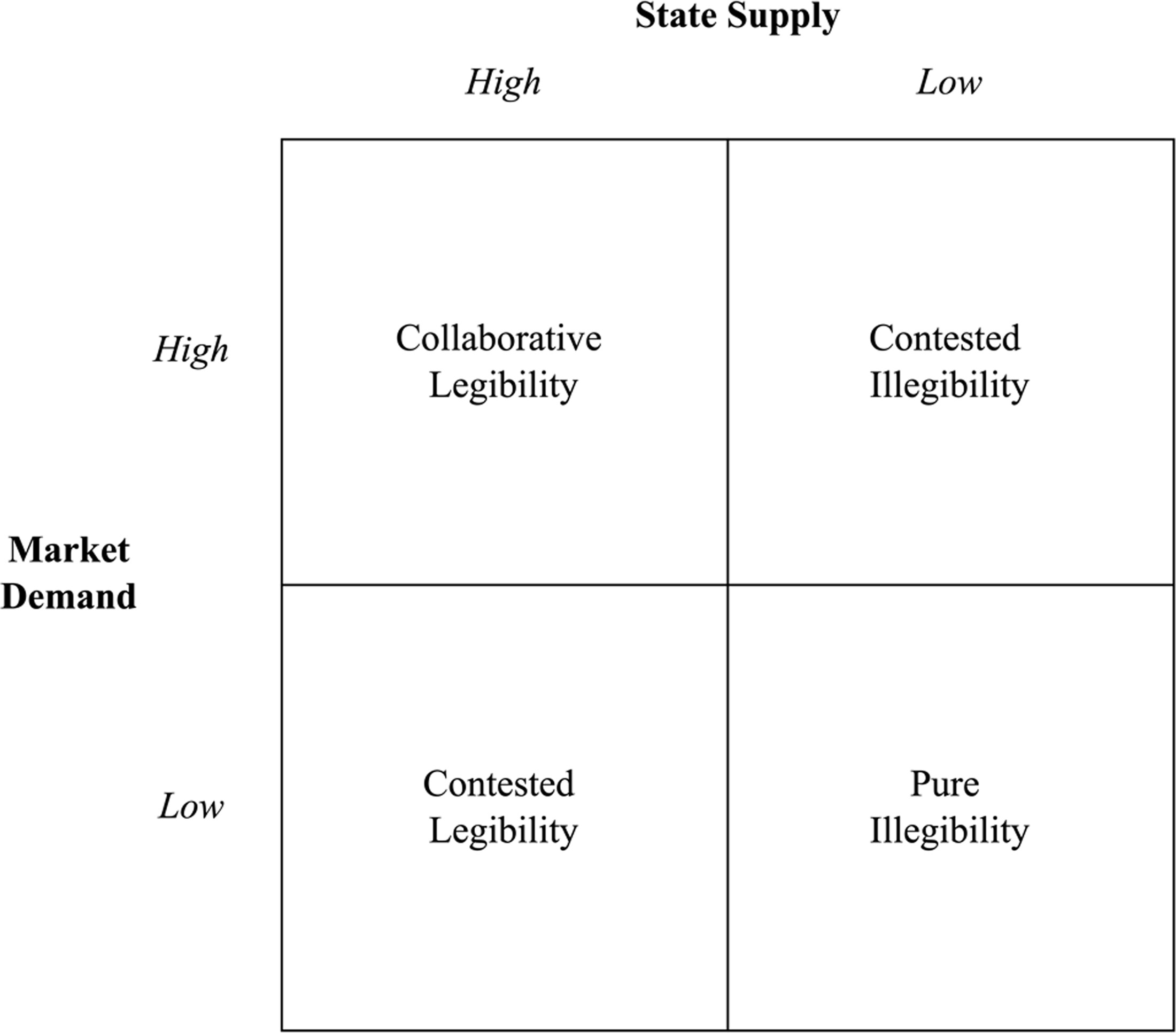

In addition to capturing distinct state-market political dynamics, the categorizations outlined above correspond to historical stages of market development and their associated “levels” of legibility (Figure 2). Most markets originate outside the state and are developed by private actors trading amongst themselves.Footnote 35 Examples include the Tontine Coffee House (predecessor of the New York Stock Exchange) and the creation of exchanges by private brokers to trade commodities.Footnote 36 In these early stages, markets are purely illegible, with neither market actors nor the state seeing a pressing need for state-led standardization. Over time, however, pressures for legibility start to emerge. This may be demand-driven by market actors seeking state regulation as a means of obtaining advantages over their competitors. Alternatively, supply-side factors, such as financial scandals that put pressure on the state to intervene in illegible markets, may be the catalyst. If supply and demand factors diverge, markets will be in a state of contested legibility or illegibility. The latter will, given the state’s hesitance to engage in standardization, feature lower levels of legibility. The former, in contrast, will feature higher levels of legibility given that the state is seeking to standardize despite market actors’ opposition. Where new markets emerge at the behest of states and/or both participants and the state agree on the need for legibility, markets may move directly from pure illegibility to collaborative legibility (depicted as the middle line in Figure 2).Footnote 37

Figure 2. Expected historical paths of market development.

In contested environments, sufficiently low demand or supply could lead markets to move “backwards” toward their original condition. But, in the long run, it is more likely that contested markets trend toward collaborative legibility. Supply and demand pressures for standardization are difficult to reverse. In scenarios of contested legibility, the state, having declared its intensions to make a market legible through standardization, is unlikely to backtrack unless exogenous events lead it to consider alternative approaches. And, in scenarios of contested illegibility, market actors’ demands for standardization are unlikely to be ignored forever.

Once markets reach the “final” stage of collaborative legibility, regression to an earlier stage becomes increasingly unlikely. Rulemaking involving the willing participation of both sides is a self-reinforcing exercise, one that increasingly envelops private markets into the state’s legal and administrative umbrella. Regulators will now view such markets as part of their turf and “core mission,” creating powerful reputational incentives to maintain control.Footnote 38 Market actors, in turn, will develop commercial dependencies on state rules. If, for example, standardization involves requiring firms to obtain licenses to perform certain regulated activities, participants will gradually seek to transact with only licensed firms.Footnote 39 Similarly, lenders and insurance companies may make licensing a precondition of their services to market actors. This is just one example of how legibility, once established, is sticky, creating self-reinforcing regulatory, commercial, and social pressures to keep markets within the visible confines of the state.

The order and pace at which markets progress through these stages has numerous practical implications. Contestation may, for example, delay the introduction of rules that protect consumers or mitigate excessive risk-taking. This could reduce participation in less “mature” markets and lead to a gravitation of capital to markets farther along the legibility path. Contestation may also create vulnerabilities in the international financial system by providing a forum where bad actors can operate unrestricted. Measuring these secondary effects is beyond the scope of this paper. Here we are focused on mapping the underlying dynamics, to which we now turn.

Empirical approach

We utilize the above framework to analyze the historical progression of cryptocurrency regulation in the EU, US, and Japan. An additional case study on the UK can be found in an appendix accompanying this article. We draw on the methods of structured-focused comparison and within-case process tracing, in which cases are structured in a similar manner to allow for a comparison of how inter- and intra-case variables produce divergent effects. Footnote 40

We conceive a case here as the historical development of regulation in a particular national financial market. Therefore, the universe of applicable cases includes any national financial market in any asset class. However, from this population we purposefully select cases on cryptocurrency in global financial centers whose general level of state regulatory capacity and market development is comparable. This approach is informed by the “most similar” case selection method, in which cases are selected that are similar in key respects but differ on the independent variable(s) of theoretical interest (legibility demand and supply).Footnote 41 Here the four cases share many characteristics such as highly developed financial markets and the presence of well-funded regulators with similar processes for developing and enforcing rules. They differ, however, in the relative level of market demand for and/or state supply of legibility. This allows us to observe how differences in the independent variables predicts variation in the outcomes of interest (the degree of market legibility and the order in which markets progress through “stages” of legibility over time). Because these cases were purposefully selected, further research on a wider set of cases is necessary to fully evaluate the theoretical framework’s explanatory power. This would include utilizing alternative case selection techniques, such as investigating extreme or unusual cases or, ideally, random selection to determine the generalizability of the framework and explore whether additional variables interact with supply and demand conditions to impact legibility outcomes.

Our case studies draw on evidence obtained from numerous resources, including records of regulatory consultations, parliamentary debates, and legal proceedings. Evidence is also drawn from online archival records of popular cryptocurrency forums, most notably the Bitcoin Forum, in addition to websites of historical platforms accessed through the Internet Archive. This evidence was also supplemented by 11 in-depth interviews with regulatory and market practitioners conducted via phone and Skype.

Case study 1: European Union

Europe is a key battleground in the global debate over cryptocurrency regulation. The EU currently features the world’s most comprehensive regulatory framework, affording the market unmatched levels of legibility. But it did not start out this way. The European market began in a state of pure illegibility, with neither market demand for, nor state supply of, standardizing rules. The EU would soon pursue regulation despite initial fear and opposition from the cryptocurrency industry. This state of contested legibility, in which supply grew while market demand for legibility remained low, was short-lived. Market participants soon became aware that European regulation was necessary for the market’s survival and began actively engaging in the policymaking process. Thus, Europe moved quickly to a state of collaborative legibility, explaining its substantial lead in the world’s regulatory race. The remainder of this section details this pattern of change, which reflects one of the key historical paths outlined by our framework.

Phase 1: Pure illegibility

Contrary to popular perception, the ideological roots of cryptocurrency can be traced back not to Silicon Valley but rather Amsterdam. In the early 1990s, the Dutch Ministry of Infrastructure and Water Management, or Rijkswaterstaat, sought to automate the collection of road tolls in a manner that preserved drivers’ privacy.Footnote 42 They turned to computer scientist David Chaum and his students, who developed a novel solution: eCash. This new form of payment used cryptographic protocols to anonymize transactions, a concept Chaum would further develop through the creation of a new Dutch company called DigiCash.Footnote 43 Though DigiCash ultimately faltered, many of its employees became “key protagonists in the story of modern-day cryptocurrency.”Footnote 44 This included the inventor of the phrase, “smart contracts,” and the founder of Zcash.Footnote 45

Another contributor to DigiCash was Eric Hughes, who would go on to create the highly influential Cypherpunks Mailing List. This mailing list, which included many early supporters and developers of cryptocurrency technology, exhibited an objective to promote anonymous economic transactions free from regulation.Footnote 46 Bitcoin would capture these principles. As its pseudonymous founder Satoshi Nakamoto remarked in an email chain in 2008, “…we can win a major battle in the arms race [against the state] and gain a new territory for freedom for several years.”Footnote 47 It cannot be determined precisely how many early adopters were based in Europe (and thus would constitute what might be referred to as the European “market”). But it is reasonable to infer that, in the initial phase of cryptocurrency trading, market demand for legibility through state standardization was essentially non-existent. To the contrary, the product on which the market was based was centered around the use of cryptography to escape state surveillance.Footnote 48

European state supply of legibility was equally absent in the first few years of the market’s existence. The first official acknowledgment of cryptocurrency by a European state entity was, to the authors’ knowledge, provided by France’s Financial Intelligence Unit (FIU), which published an analysis of its threats in 2011.Footnote 49 And, indeed, most EU states’ initial response was to warn their citizens of the dangers of engaging with virtual currencies.Footnote 50 This initial round of warnings appears to have been coordinated with those provided by the European Banking Authority (EBA) in 2013, which emphasized the market’s lack of regulation.Footnote 51 By providing no clarity on their regulatory status, this round of warnings denied the standardization necessary for legibility. Thus, the European cryptocurrency market began in a state of pure illegibility, in which both demand for, and state supply of, legibility was low. This equilibrium would not, however, last for long.

Phase 2: Contested legibility

As retail adoption of virtual currencies grew in the early 2010s, new online exchanges emerged to facilitate trading. The first exchange to obtain dominance was Japan-based Mt. Gox, which at its height facilitated 70% of the world’s cryptocurrency trading.Footnote 52 Mt. Gox would eventually suffer an enormous hack leading to its bankruptcy and the criminal prosecution of its CEO.Footnote 53 This event defrauded thousands of EU citizens, creating increased pressures on legislators and regulators to clarify the market’s legal status.Footnote 54 Simultaneously, new European exchanges emerged such as the Slovenian-based Bitstamp, raising questions as to whether cryptocurrency service providers must abide by traditional financial regulation.Footnote 55

The EBA was one of the first EU agencies to suggest solutions, opining in 2014 that virtual currencies—the preferred legal term in Europe—be incorporated into Anti-Money Laundering (AML) rules in the short-term while more comprehensive regulations are developed.Footnote 56 A key forum for this debate was the European Commission’s Expert Group on Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing (EGMLTF), which includes representation of all EU states, EU bodies, and delegations from Liechtenstein, Iceland, and Norway. In June 2014, the EBA presented its proposals to this group, prompting debate on how best to regulate virtual currency markets.Footnote 57 Numerous unnamed member states cautioned that regulation might confer credibility and legitimize the market.Footnote 58 But a consensus quickly developed that regulation was necessary.Footnote 59 Numerous enterprising states such as Malta and Estonia started developing their own rules and registration systems.Footnote 60 And, in contrast to the hesitancy of regulators in the US and UK, the EBA lobbied for the responsibility to promote consumer awareness.Footnote 61 State supply of legibility was, in other words, rapidly increasing.

By the time EU regulators were debating regulatory approaches in 2014, the market itself had grown to encompass a much more varied array of platforms and participants. Opinions among this group naturally varied, but it can be inferred that fear of, and opposition to, invasive regulation was dominant. The co-founder of Bitstamp, for example, told Forbes in 2014 that fear of expensive regulation was one of their top two challenges.Footnote 62 An influential European private equity investor echoed this sentiment, noting in 2013, “A lot of the Bitcoin world so far has been, ‘we don’t want regulation, we don’t want any of that stuff’…but unfortunately in the world of currency in 2013 the world expects traceability.”Footnote 63 And, though it is difficult to make generalizations about the views of cryptocurrency participants, a 2014 study found that attraction to Bitcoin was associated with beliefs about its capacity to free users from state and financial power structures.Footnote 64 Thus aggregate market demand for legibility remained low. Such opposition would, however, be short-lived as it became increasingly apparent that state regulation was not just inevitable, but perhaps beneficial to the continued survival of the market.

Phase 3: Collaborative legibility

Approximately one year after Mt. Gox’s implosion, another event would accelerate EU regulatory efforts: the 2015 terrorist attacks in Paris. While it remains unclear whether the perpetrators used Bitcoin to fund their operations, the case revived concerns about the capacity of virtual currencies to facilitate terrorism.Footnote 65 The European Commission subsequently published an Action Plan which included the application of AML rules to certain virtual currency actors.Footnote 66 A few months later, the Commission released an impact assessment of specific proposals to incorporate virtual currencies into the Fifth AML Directive (5AMLD).Footnote 67 Notably, the Commission recognized a divergence in the market demand for legibility:Footnote 68

…a number of users may be attracted primarily by the anonymity offered by virtual currencies and could therefore be more reluctant to willingly contribute to the sanitization of the market. However, there may be other users primarily interested by the economic dimension of that market…who might be ready to divulge their identity in order to bring more transparency in the market, contributing thereby to improving its reputation and in turn its greater use.

The Commission’s impact assessment included non-public consultations with industry members, including Bitstamp, Circle, the Electronic Money Association, and a working group that included firms such as BitPay, Elliptic, and Chainalysis.Footnote 69 Their views on regulation were clear: “…the VC [Virtual Currency] industry was generally favorable to legislation that would primarily give them more legitimacy and, secondly, would help to differentiate between players that make the most concerted efforts to track criminals from bona-fide users.”Footnote 70 Numerous organizations representing consumers were also consulted and, while expressing some concerns about privacy, agreed that the industry would benefit from the application of gatekeeper obligations.Footnote 71 It is important to note that these groups may not represent the views of all market participants (particularly ideological purists who might object to participating in such consultations). But their responses nevertheless constitute a remarkable turning point in the market demand for legibility in Europe, in which the driving force was now to seek state standardization as a means of legitimizing virtual currencies and promoting their wider adoption.

Ultimately, the 5AMLD would require two types of cryptocurrency firms to establish full AML programs: custodian wallet providers (entities that safeguard cryptographic keys on behalf of customers) and those facilitating the exchange of virtual and fiat currencies.Footnote 72 But this was only the beginning. European regulators would quickly be forced to address a sudden proliferation of Initial Coin Offerings (ICOs), a method of raising funds from users with similar characteristics to initial public offerings.Footnote 73 This was followed by Facebook announcing their creation of Libra, a so-called stablecoin that is pegged to a reference asset (e.g., the US dollar) to maintain a consistent value.Footnote 74 These developments, particularly the prospect of billions of Facebook customers using a virtual currency that may pose risks to financial stability, made it clear to European regulators that more comprehensive rules were necessary.Footnote 75

The EU would subsequently introduce two changes: the Markets in Crypto-Assets (MiCA) Regulation and Transfer of Funds Regulation (TFR). MiCA establishes a framework for issuers of stablecoins, defines regulated crypto services, and applies a wide variety of obligations to entities performing such services.Footnote 76 The European Commission sought comments on MiCA and received 198 responses.Footnote 77 Naturally, there was disagreement on the details, but the majority agreed that a regulatory regime for crypto assets would increase the sustainability of the industry by providing legal certainty and harmonization.Footnote 78 The TFR is an existing regulation whose application to crypto requires the sender and beneficiary of transactions to be identified.Footnote 79 Applying these rules has been criticized as a violation of users’ privacy.Footnote 80 But the industry’s solution was to engage policymakers rather than seek to evade their grasp. This exemplifies collaborative legibility, where both the state and market actors are willing participants in the standardization process.

But, as noted by our framework, collaborative legibility does not necessarily equate to a perfectly harmonious relationship between the state and the market. Following the introduction of plans to apply TFR to virtual currencies, certain (particularly female) Members of Parliament were harassed online by members of the crypto community.Footnote 81 There was no love lost with Andrea Enria, the ECB’s head of financial supervision, who characterized the industry as “animals with whom it is difficult to engage.”Footnote 82 Nevertheless, the history of European legislation exhibits an increasing level of collaboration with the industry over time. Notably, this has included a recent growth of engagement by the decentralized finance (DeFi) community. DeFi broadly refers to systems based on decentralized and permissionless protocols that operate without need for centralized governance mechanisms.Footnote 83 Such systems tend to be favored by those who retain an ideological commitment to cryptocurrencies’ privacy-protecting and democratizing ideals.Footnote 84 DeFi’s decentralized nature has, however, made it difficult for the community to voice its preferences over regulation.Footnote 85 But even here we observe an increase in engagement. In 2022, for example, more than 2,000 members of the German DeFi community signed a letter criticizing various components of MiCA and the EU’s application of TFR to virtual currencies.Footnote 86 One might have expected this to resemble a libertarian manifesto against state intervention. But, to the contrary, the letter is a sober analysis of proposals firmly embedded in a commitment to legibility: “Our industry and techno-social movement needs clear regulations and consumer protection to flourish.”Footnote 87

Case study 2: United States

The United States is the world’s largest cryptocurrency market. It is home to many of the most impactful projects, developer communities, early-stage investors, and users. But, despite long-standing and increasingly broad-based industry demand for legibility, US markets are among the least legible in the world. From the market’s foundations in a state of pure illegibility, state-market relations slipped into a deepening pattern of contested legibility, a pattern that sharpened following the collapse of FTX. This battle between standoffish state regulators and legibility-seeking market participants is being played out in enforcement actions, the juridical system, and the court of public opinion.

Phase 1: Pure illegibility

The US crypto market emerged in a state of pure illegibility. For several years after Bitcoin’s inception in 2008, no US government agency expressed concern about the need to regulate cryptocurrencies. Likewise, the most important market voices remained committed to illegibility. The Bitcoin Foundation, for instance, argued that regulation could do little to strengthen the industry and pushed back against state intervention by threatening to move abroad if regulated.Footnote 88 This mutual neglect between state and market only ended with the first US congressional hearings on the cryptocurrency markets in 2013.Footnote 89

Phase 2: A false dawn of collaboration

Even before the collapse of Mt. Gox in 2014, parts of the market started to solicit state regulation and, initially, there were indications that the state would supply legibility through the standardization of the cryptocurrency market in accordance with existing regulatory frameworks.Footnote 90 However, this period between 2012 and 2016 proved to be a false legibility dawn.

The main private sector entrepreneurs of this legibility demand were newly established cryptocurrency companies like Coinbase, launched in 2012.Footnote 91 Coinbase’s CEO Brian Armstrong promised to build a “safe” and “legitimate” place for mainstream investors to buy and trade Bitcoin.Footnote 92 To do this, Coinbase set out to translate its business to US government agencies, thereby augmenting their capacity to impose oversight and control. “We reached out proactively … to regulators and tried to be an educational resource … to be legitimate,” Armstrong explained.Footnote 93 Without state recognition, he feared, the industry was “always going to be in the shadows [and] someone was always going to try to shut [things] down.” Coinbase was supported in this push by other centralized exchanges such Kraken and Gemini.Footnote 94

Similar private legibility forces strengthened in other market segments seeking to build bridges between cryptocurrencies and traditional financial markets. LedgerX approached the CFTC to seek approval for a registered Bitcoin derivatives and options exchange in 2014.Footnote 95 Regional banks, like Silvergate, and traditional payment companies, such as Paypal, engaging with crypto products and firms, and early investment funds, such as the Bitcoin Investment Trust (BIT) and the Winklevoss twins’ Bitcoin Exchange Traded Fund (ETF), likewise pushed for recognition to guard against the legal risks of moving into the new field.Footnote 96 Further, emergent stablecoin providers were key agents of legibility. Circle CEO Jeremy Allaire, for example, called on US Senators as early as 2013 to provide a bespoke digital assets regime.Footnote 97

The shared goal of state recognition among industry players encouraged the formation of collective lobbying organizations in Washington seeking Federal-level regulations that would pre-empt state licenses. Coin Center and The Chamber of Digital Commerce were launched in 2014 to promote sound public policy and the acceptance and use of digital assets. Together they also founded the Blockchain Alliance as a coalition of market actors and US government agencies focused on enforcement actions against criminality in the market.

In this initial period, there were signs that the state was prepared to provide a degree of legibility. The Treasury Department’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) issued guidance in March 2013 advising that Bitcoin exchanges and other market services providers qualified as money transmitters under the Bank Secrecy Act.Footnote 98 Several state regulators and legislatures, including most notable New York and California, moved to introduce licensing frameworks that were quickly adopted by market participants.Footnote 99 The CFTC and SEC indicated in public comments that they had jurisdiction over Bitcoin and other digital assets.Footnote 100 However, for the most part, US regulators stalled.

The most prominent SEC and CFTC actions were to issue product warnings to investors.Footnote 101 These warnings became increasingly intense and were often perceived as aggressive by market actors.Footnote 102 In contrast, regulatory approvals were so limited in scope that basic industry questions, such as whether they needed to register their services with regulators, went without answers. The industry’s desire for legal certainty was plagued by a mixture of silence, ambiguous or conflicting statements and fundamental disagreements between the SEC and CFTC over essential issues such as whether and how cryptocurrencies should be legally classified, be it as securities, commodities, or something new entirely.Footnote 103 There were worrying signs for the industry that both agencies might prefer to regulate through enforcement and case-by-case settlements with individual companies rather than establish new regulatory frameworks. For example, the CFTC ordered Bitcoin options trading platform operator Coinflip to cease illegally offering Bitcoin options and to cease operating a facility for trading or processing of swaps without offering a clear path to legal registration.Footnote 104

The Federal Reserve adopted a similar holding pattern that denied the industry the recognition it wanted. In a letter to the first US Senate hearings on Bitcoin in November 2013, Ben Bernanke recorded that, while monitoring developments, the Federal Reserve “does not necessarily have authority to directly supervise or regulate these innovations or the entities that provide them to the market.”Footnote 105 Janet Yellen, giving evidence to the House Committee on Financial Services’ Monetary Policy and Trade two years later, suggested that before acting “The costs and benefits of developing new statutes or regulations related to digital currencies should be weighed carefully.”Footnote 106

Despite the hesitancy of US regulators, the mood music in this period was still one of dialogue, leading many to anticipate that the incorporation of cryptocurrencies into the status quo regulatory system was inevitable. In other words, it appeared at first glance that this early period of contested illegibility would give way to collaborative legibility. But a series of high-profile scandals, combined with the development of DeFi innovations, would puncture this emerging trust, leading regulatory agencies to prioritize enforcement over engagement.

Phase 3: Deepening of contested legibility

Market demand for regulatory clarity, voiced by exchanges and other market service providers that increasingly resembled traditional finance, became more public in the aftermath of the ICO boom in 2017–18. But this was not the only corner of the cryptocurrency markets placing pressure on regulators. The task of the state was complicated by the fact that they would soon have to address whether to standardize, and, in turn, afford legibility to, DeFi.

While the term DeFi covers heterogeneous innovations, many early projects prioritized the elimination of centralized control by intermediaries or the state.Footnote 107 To that end, DeFi innovations have sought to replace intermediaries (and human judgment) with peer-to-peer (or peer-to-protocol or P2P) order books and direct trading facilities.Footnote 108 These advancements culminated in the “summer of DeFi” in 2020 in which investment and participation rapidly grew.Footnote 109 While most participants were calling for increased regulation, some DeFi actors maintained a preference for illegibility as a means of escaping state control.

The business model of Uniswap, a leading DeFi exchange founded in 2019, illustrates the nature of this disruption. While a group of developers in the so-called Uniswap Lab maintains and updates the protocol, Uniswap claims that certain existing US laws cannot reasonably apply to its services because there is no responsible administrator to whom outside regulatory obligations might be directed.Footnote 110 Uniswap even denies that it operates as an exchange facilitating the execution or settlement of trades.Footnote 111 Instead, it states that all this happens on the public distributed Ethereum blockchain in a P2P fashion.Footnote 112 This can be read as an example of a strategy to minimize “on-chain” governance and so maximize illegibility.Footnote 113

DeFi innovation created a dilemma for state regulators. US securities and commodity market regulators and statutes were designed to impose standards on centralized market intermediaries. Faced with this gap between the law and emerging market technologies, regulators did little more than speculate on whether or not existing rules would apply in speeches that many market participants viewed as inconsistent.Footnote 114 They also often suggested that they lacked the authority to bring legibility to the DeFi market without new legislation.Footnote 115 Congressional interest in cryptocurrency did grow during this period and again it seemed that recognition might be possible under a new regulatory framework, but this momentum towards legibility would be severely disrupted by the shocking decline of FTX.

In November 2022, FTX, the second-largest cryptocurrency exchange in the world—led by one of the most influential voices of the industry Sam Bankman-Fried or “SBF”—imploded in spectacular fashion. The alleged misallocation of customer funds to an affiliated trading outfit led to almost $9 billion in losses for users and seismic pressures on market prices.Footnote 116 The event increased market demand for regulation but placed arguably greater downward pressure on state supply. US regulators, and the SEC and Federal Reserve in particular, moved with force in the direction of illegibility. The market started to fear that there was an operation in the Federal Reserve to cut crypto off from the banking system.Footnote 117 The SEC meanwhile was threatening de facto to push the market definitively outside the regulated domain through the assertion that existing securities laws applied to the industry with the implication that most of the market operators would not be able to continue with their existing business practices.Footnote 118 By way of example, the SEC asked Coinbase to delist every one of the more than 200 tokens it traded except Bitcoin. Coinbase’s CEO argued that, if it agreed, this interpretation of the law “would have essentially meant the end of the crypto industry in the US.”Footnote 119

The Federal Reserve took similar actions. Silvergate and Signature, two banks that failed in large part due to FTX’s collapse, would not receive the Fed’s support, threatening to thoroughly isolate cryptocurrency markets from the traditional financial system.Footnote 120 The two banks mattered not only because they provided banking services to crypto firms, but also because, through services known as the Silvergate Exchange Network (SEN) and Signet, they allowed participants to instantly transfer US dollars to and from crypto exchanges and trading desks. This provided essential liquidity to the markets. Barney Frank, a former congressman and Signature Bank board member stated that: “I think part of what happened was that regulators wanted to send a very strong anti-crypto message.”Footnote 121 This assertion was not confirmed by regulators. But whatever the motive of the Federal Reserve’s action, the consequence was to set back the integration between traditional and cryptocurrency markets.

Market regulators have been open about the adoption of a forceful illegibility stance. SEC Chairman Gary Gensler, in striking remarks that suggested a turn to illegibility, indicated that the US financial system did not need more cryptocurrencies because the US dollar was already digital.Footnote 122 He also argued that almost all cryptocurrencies apart from Bitcoin were securities, implying that they are operating illegally if not registered.Footnote 123 Moreover, Gensler claimed, in contrast to the market’s collective protest, that “there had been clarity for years” and the SEC had all the authority it needed to take actions against firms under existing securities legislation as in its enforcement action against Ripple Labs.Footnote 124 The SEC followed this up by bringing a Wells Notice Action against Coinbase for acting as an unregistered securities exchange, broker, and clearing house.Footnote 125 Binance, the world’s largest cryptocurrency exchange, similarly came into the crosshairs of the CFTC and SEC.Footnote 126

The industry has accused US regulators of being evasive and acting in bad faith. To force the government to provide the legibility it seeks, Coinbase has taken dramatic steps including issuing a petition for rulemaking and even suing the SEC in an effort to force the production of new rules.Footnote 127 Though actions that see market participants sue the state in an effort to be regulated might seem rare, this is probably best seen as a tactic within a broader move by Coinbase and other firms to get Congress to issue new rules. The hope seems to be that US politicians and legislators will act where regulators have refused to. In line with this agenda, the industry has opened a major public relations and lobbying campaign arguing that cryptocurrency needs new rules.Footnote 128

There is no guarantee however that this strategy will be successful. Coinbase has already accused the SEC of simply ignoring its petition.Footnote 129 Moreover, given the diverse range of opinions that exist on the Hill, it is not clear that the industry will get the regulation that it seeks. If the issue remains in the juridical system, it is unlikely that the industry will get the system wide legitimation it seeks. Thus, for now, the US cryptocurrency market remains in a state of contested illegibility. Despite sustained growth in market demand for standardized rules, state supply has declined in response to a string of high-profile scandals. As a result, the level of clarity surrounding cryptocurrencies in the US continues to trail other regions.

Case study 3: Japan

Embarrassed by the collapse of Mt. Gox in 2014, Japan became the first country to develop a “proper legal system regulating cryptocurrency trading.”Footnote 130 Japan’s regime moved rapidly from pure illegibility to collaborative legibility. In the process, Japanese officials and market members overcame many of the definitional and legal issues that have confounded attempts to introduce legibility in other jurisdictions such as the US and UK. Proving that legibility is possible when demand- and supply-side conditions are satisfied, public and private actors acted as joint entrepreneurs in the creation of two new SROs to govern and oversee core aspects of the crypto markets. The SROs act as conduits of legibility by formalizing inter-institutional relationships and information flows.

The pattern of interaction among states and markets since the establishment of this collaborative legibility regime in 2016 has assumed a familiar pattern. The industry, concerned about the burdens of regulations and a series of departures from the market, has sought to dilute the legal constraints and weaken the capacity of state regulators. In contrast, state officials, dismayed by perceived conflicts of interest in the SROs and stalling actions by the industry, have pushed for tighter disclosure requirements and prudential rules.Footnote 131 However, the regime’s problems and industry concerns notwithstanding, in 2023 Japan’s comparatively legible markets have arguably proved themselves more resilient than their illegible counterparts in the US and UK.

Phase 1: Pure illegibility

As in other jurisdictions, crypto currencies came to Japan without much awareness on the part of state regulatory bodies. In its early years, the industry was an anarchistic affair that attracted some pioneers of the market’s growth such as Cardano’s Founder Charles Hoskinson and Binance CEO Changpeng Zhao or “CZ.”Footnote 132 The industry boomed in a laisses faire milieu. Mt. Gox, a Tokyo-based cryptocurrency exchange that operated between 2010 and 2014, grew to dominate the market. At its peak in 2014, as noted above, Mt. Gox was widely reported to be responsible for more than 70% of Bitcoin transactions worldwide.Footnote 133

In this era of pure illegibility, a spirit of caveat emptor (buyer beware) prevailed among market users. Mt. Gox for instance experienced a series of security breaches and network failings starting as early as June 2011.Footnote 134 Eventually, these failures spawned the first indications of legibility demand. Mt. Gox CEO Mark Karpeles sounded tentative calls for state oversight. He was reported to have said in 2013 that “as the Bitcoin market continues to evolve and expand, [Mt. Gox] must adjust to new regulatory and compliance demands.”Footnote 135 Like other behemoths to come, Karpeles was very likely motivated by a desire to shore-up user confidence and embed Mt. Gox’s dominant position in the market. However, state supply of legibility was not forthcoming.

The dramatic breach of Mt. Gox in 2014 that led to the theft of nearly 500 million USD worth of bitcoin and the bankruptcy of the exchange shattered this situation of mutual neglect between state and market representatives and placed pressure on the Japanese state to intervene.Footnote 136 This pressure was strengthened by public perceptions that cryptocurrency was associated with Japanese organized crime.Footnote 137 Against this background, the Japanese Financial Service Authority (JFSA) established a specialized Working Group on the Mt. Gox collapse and associated regulations. The Working Group’s report, submitted to the JFSA in 2015, recommended that the state bring legibility to the crypto markets. Footnote 138

Phase 2: Establishing collaborative legibility

Running in parallel with the Working Group in 2014, market demand for legibility strengthened with the formation of the Japan Authority of Digital Assets (JADA) (later renamed the Japan Blockchain Association (JBA)) comprising blockchain and cryptocurrency start-ups and entrepreneurs.Footnote 139 In 2015, as pressure for regulation intensified, a further lobbying group called the Japan Crypto Business Association (JBCA) was created to push for regulations in Tokyo and hold study sessions with lawmakers that would increase awareness about the industry.Footnote 140 These connections helped to augment legibility. “We had constant discussions with the FSA, giving technical information and ideas,” explained So Saito, a founding member of JADA and now general counsel of its successor the Japan Blockchain Association (JBA).Footnote 141

The market presented two familiar legibility issues for Japanese regulators: the legal status of cryptocurrencies and whether coin offerings and exchanges would fall under existing securities market regulations. It took more than two years to resolve the legal status of virtual currencies, and several different paths were explored. Eventually, crypto assets were recognized through a 2016 amendment of the Payment Services Act (PSA) and the Act for Prevention of Transfer of Criminal Proceeds (APTCP) which came into force in 2017.Footnote 142 With respect to second question of existing securities markets laws, policymakers decided to build a new framework and establish the concept of Crypto Asset Exchange Service Providers (CAESPs).Footnote 143 Crypto exchanges that wanted to operate in Japan were required to register with the JFSA and the regulator was given the power to conduct on-site inspections and issue business improvement orders.Footnote 144

By the end of 2017, of the exchanges operating in Japan before the authorization requirement, 16 had been approved by the JFSA as CAESPs.Footnote 145 However, before the regime had time to bed down, two huge hacks shook confidence in the emerging regulated market. Coincheck suffered the then biggest hack of all time, losing $500m assets worth of BTC in January 2018.Footnote 146 Later, in September 2018, the Zaif exchange got hacked for 6000 BTC worth around $60m.Footnote 147 While state officials argued the hacks and the new framework were not connected, state regulators and market participants were left searching for a way to restore market confidence.Footnote 148 The prescription was to augment legibility through the existing collaborative regime.

A new Study Group on Virtual Currency Exchange Services convened 11 times in 2018 to discuss regulatory responses to various issues concerning CAESPs.Footnote 149 Coincheck, in consultation with the JFSA, pioneered a new private sector standard setter comprised of sixteen exchanges called the Japanese Virtual Currency Exchange Association (JVCEA) in April 2018. The JVCEA was formerly recognized by the JFSA to engage in rule creation and other oversight tasks giving the industry its first state induced and sanctioned SRO. Cementing the institutional ties between the state and market, JVCEA members were drawn from the JFSA’s list of statutorily licensed CAESPs. At the same time, further Amendments to the PSA and the Financial Instruments and Exchange Act (FIEA) served to bring derivative trading inside the state regulatory perimeter.Footnote 150

The reforms had a measure of success. But continuing issues of fraud around ICOs and security token offerings (STOs) led to demand for a further extension of the scope of the regime.Footnote 151 In 2018, the JFSA established a Study Group on STOs consisting of representatives from traditional financial firms, software development companies, and the government.Footnote 152 The Study Group’s report proposed a framework for coin issuances, which would be implemented by an SRO called the Japan Security Token Offering Association (JSTOA).Footnote 153 The goal of the JSTOA was to augment legibility in the STO and ICO markets. The same period also witnessed a series of Amendments to the PSA, Banking Act, and Trust Business Act to address the regulation of stablecoins.Footnote 154

This sequence of reforms introduced a framework of collaborative legibility that was truly impressive in scope. A regime characterized by broad regulatory coverage capable of capturing a wide variety of tokens, including DeFi assets, was brought into existence and proved itself to be adept at continued expansion. The Japanese framework has achieved a degree of legibility that is variously claimed to be either impossible or undesirable in other jurisdictions. As one observer put it, “On the surface, from purely a regulatory point of view, Japan has got its act together.”Footnote 155 However, as this quote suggests, the practical workings of the regime are more complex. As in the EU case, there have been acute difficulties in the management of collaborative legibility. But, in stark contrast to other countries, the idea that the Japanese crypto market will be regulated by the state has not been an object of contention for a long time.

Conclusion

It is often written that regulators are playing “catch-up” with the private sector, struggling to keep pace with new innovations. This statement implicitly assumes that the state desires to standardize such innovations and undertake responsibility for their oversight. It also assumes that private firms are constantly seeking to escape the state’s regulatory sphere. Neither is given. There are numerous situations in which the state may be incentivized to withhold its supply of what we term market legibility. Similarly, the market’s demand for such legibility is also expected to vary. We contend that the combination of these supply and demand variables produce ideal type states of legibility that correspond to distinct stages of development and the corresponding level of regulatory clarity in any one national financial market.

Case studies on the EU, US, UK, and Japan demonstrate how the concept of market legibility can help us understand these political-economic dynamics. Despite sharing common characteristics such as highly developed financial markets and established processes of regulatory consultation, cryptocurrency markets in these countries exhibit differences in the order and pace at which they proceeded through stages of (il)legibility. Similar struggles over legibility are taking place in other jurisdictions. China, for instance, has left the industry chafing for recognition and legibility under sweeping bans and exclusions. The People’s Bank of China, after several standoffish years, moved decisively in 2021, declaring that “cryptocurrencies do not have the same legal status as currencies” and “all virtual currency-related business activities are illegal and should be strictly prohibited and cracked down upon.”Footnote 156 In contrast, smaller jurisdictions such as Abu Dubai, the Bahamas, and Singapore have moved to promote collaborative legibility. In the words of one interviewee comparing the situation in the Middle East to the US, “we prefer engagement to enforcement.”Footnote 157

And there is reason to believe that this concept can also be applied to a wide variety of other markets and asset classes. Securities markets in the US, for example, emerged in a state of pure illegibility. The state allowed such markets to largely self-regulate for much of their history until the Great Crash of 1929 disrupted this stable equilibrium and placed pressure on the state to formulate the present-day framework of securities laws.Footnote 158 Likewise, standoffish states permitted certain commodity derivative markets to operate without oversight or control, notwithstanding a strong demand for legibility from already regulated commodity futures exchanges, until the 2008 financial crisis prompted intervention.Footnote 159

Exploring the application of this framework to other states and markets would be a natural first step to evaluating its full generalizability. Future work should also evaluate whether the order or pace at which markets progress through stages of legibility are associated with differences in stability, participation, and other market quality factors. Further, there are numerous additional theoretical avenues to explore. Our analysis has focused on legibility dynamics in individual jurisdictions. How might these dynamics cascade or spill over into other jurisdictions? And how might other variables, such as the types of digital assets trading in different jurisdictions and their specific characteristics, interact with supply and demand conditions to impact the development of market regulation? We also observe that legibility, once obtained, tends to be “sticky,” reducing the likelihood of markets reverting to previous states. Are there any exceptions to this trend, and if so, what causes such reversion? Researching these questions would improve our understanding of legibility, and, more broadly, the political economy of financial regulation.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/bap.2023.38.

Acknowledgements

We thank the editorial team and anonymous reviewers of Business and Politics as well as members of the Waseda Institute of Political Economy (WINPEC) for insightful comments on earlier drafts. We also thank Moe Ryo (Meng Liang) for outstanding research assistance. This kind of work would not be possible without the generous support of industry participants and regulators willing to provide insights into market regulation and governance. This research was supported by a Japanese Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (KAKENHI) (Grant no. 00865800).