Like any observant reader of Edmund Burke's Reflections on the Revolution in France, James Gillray quickly realized that many of Burke's most provocative conclusions derived from his interpretation of English political and constitutional history. These latter subjects were accordingly given center stage in Gillray's satirical interpretation of the work, which appeared just a few weeks after the publication of the Reflections and which remains perhaps the best-known visual response to Burke's text (figure 1). Gillray's Smelling out a Rat depicts an outsized Burkean proboscis, surmounted by giant spectacles, discovering the intrigues of the homegrown “Atheistical-Revolutionist” Richard Price, whose 1789 sermon to the Revolution Society in London's Old Jewry was the target of sustained pejorative commentary in the Reflections. Price and his audience had of course been commemorating the anniversary of the “Glorious Revolution” of 1688, which he treated as a precedent for recent events in America and France. In Gillray's print, however, Price sits beneath a depiction of Charles I's execution in 1649, within a gilded frame inscribed “the Glory of Great Britain.” The clear allusion is to Burke's allegation that “these gentlemen of the Old Jewry, in all their reasonings on the Revolution of 1688, have a revolution which happened in England about forty years before, and the late French revolution, so much before their eyes, and in their hearts, that they are constantly confounding all the three together. It is necessary that we should separate what they confound.”Footnote 1

Figure 1 James Gillray, Smelling out a Rat; or The Atheistical Revolutionist Disturbed in his Midnight Calculations (London, 3 December 1790), British Museum (hereafter BM) Sat. 7686.

Burke advances this claim repeatedly in the first part of the Reflections, chiefly through an unflattering comparison of Price with Hugh Peters, the notorious Cromwellian preacher and regicidal apologist. Price's sermon on 1688 responded to his own revolutionary age with a culminating nunc dimittis, “for my eyes have seen thy salvation.”Footnote 2 His inspiration, Burke mischievously insinuated, was in fact Peters's identical scriptural invocation in response to the trial of Charles I.Footnote 3 Price's text “differs only in place and time, but agrees perfectly with the spirit and letter of the rapture of 1648.”Footnote 4

Burke's references in the Reflections to the civil wars and interregnum—the first Stuart revolution, as it may be designated in contradistinction to that of 1688—thus invite explanation in terms of his growing hostility to the radical dissent of Price and his unitarian allies. Burke's alarm at Price's political and religious principles, it has been argued, led him to revive and reapply long-standing anti-Puritan prejudices, exemplified in David Hume's identification of the “fanatical spirit” of the 1640s as a solvent for “every moral and civil obligation.”Footnote 5 But Burke's critique of English dissent in the Reflections can also be understood to have application to contemporary France. And, in this case, the secular revolutionary ideology of the philosophes reveals a paradoxical affinity with the seditious tendency of seventeenth-century religious enthusiasts. The spiritual self-sufficiency of the Protestant zealot, Burke seems to imply, finds its modern correlative in the autarchic faculty of Enlightenment reason and its iconoclastic refashioning of inherited laws and institutions.Footnote 6 As the most authoritative recent overview of Burke's political thought has argued, the “Reflections, faced with a resurgence of the attitudes of the 1640s, was Burke's response to what he saw as the specious illumination of fanatics,” albeit repackaged for the eighteenth century by the “false prophets of enlightenment.”Footnote 7 The modernity of the French experience, its break from previous revolutionary “scripts,” continues to offer a powerful explanatory framework for historians of 1789.Footnote 8 By contrast, Burke's insistent recourse to mid-seventeenth-century precedent appears to ground his understanding of the French Revolution in the atavistic categories of regicidal rebellion and Puritan enthusiasm.

Yet the civil wars and interregnum also possessed a more proximate significance for Burke, which bore directly upon the ideological identity of his own party. This, at least, is the implication of another, less familiar visual satire on the controversy sparked by the Reflections, James Sayers's Mr. Burke's Pair of Spectacles for Short Sighted Politicians, which appeared in May 1791 (figure 2). Sayers's technical deficiencies as a draughtsman have tended to obscure the conceptual sophistication of his work: Mr. Burke's Pair of Spectacles is in fact an ingenious response not just to Burke but also to Gillray's Smelling out a Rat. The spectacles that feature so prominently in the earlier print are now redirected at Burke's opposition colleagues, Charles James Fox and Richard Brinsley Sheridan, revealing a scene of both constitutional subversion and unsettled temporal perspective. In Gillray's work, Charles I's executioner remains firmly within the realm of historical representation; here, however, he is reanimated in the form and posture of Fox, whose axe (inscribed with “Rights of Man”) is directed at the base of a British oak hung with the emblems of crown, church, and nobility. The resultant sense of historical dislocation is further accentuated by the fact that, while Fox wears a French cocked hat, the rest of his dress is suggestively Cromwellian.Footnote 9 At the bottom right of the scene, the skeleton of the recently deceased Price rises from the grave, ironically accompanied by the text of the nunc dimittis, “Lord now lettest thy Servant depart in Peace.” Parodying the conventions of early modern figure painting, Price assumes here a marginal, mediating role: his eyeless sockets, directed out at the viewer, implicitly invite us to view the scene instead through Burke's more luridly prophetic lenses. The dissenting minister's ghastly reanimation thus enforces Sayers's larger implication that, if the spirit of the great rebellion is come again, it is in the form of both radical nonconformity and opposition Whiggism.

Figure 2 James Sayers, Mr. Burke's Pair of Spectacles for Short-Sighted Politicians (London, 12 May 1791), BM Sat. 7858

This was by no means the first occasion on which Fox had been cast as a Cromwellian usurper (and we shall have cause to return to Sayers's work in this respect). Its immediate context, however, was the dramatic break between Burke and Fox. The end of their friendship, “violently and publicly dissolved,” presaged the disintegration of the parliamentary opposition and thereby assumed a central role in the mythology of nineteenth-century Whiggism.Footnote 10 The iconography of Sayers's print might indeed seem to anticipate Lord Acton's later judgment that the Whig party “has a double pedigree, and traces its descent on the one hand through Fox, Sidney, and Milton to the Roundheads, and on the other through Burke, Somers, and Selden to the old English lawyers. Between these two families, there was more matter for civil war than between Cromwell and King Charles.”Footnote 11 As a genealogy of party, this account must now seem at best reductive, but it catches the centrality of the Stuart era to the ideological self-conception of the age.Footnote 12 Whig historians of the nineteenth century were unembarrassed both in tracing their party back (at least) as far as the parliamentary opposition to Charles I and in regarding the breach between Fox and Burke as a great schism in the historical transmission of liberal principles.Footnote 13 The dissensions within the Whig party of the early 1790s were conducted at a comparable pitch of historical awareness. Fox himself had no great sympathy for Cromwell but frequently owned his attachment to seventeenth-century “patriots” such as Russell, Sidney, and those “who had first taken up arms against Charles 1st.”Footnote 14 No doubt Burke had participated, along with Fox, in the Whig Club's standing toast to “The Cause for which Hampden bled in the Field, and Sydney on the Scaffold” (he formally resigned his membership in February 1793).Footnote 15 But his profound commitment to constitutional liberty led him to venerate not the seventeenth-century heroes of patriot myth but the Junto Whigs, including John, Lord Somers, who had secured the settlement of 1688–89 and whose “old Whig” principles Burke quoted at length in response to his critics.Footnote 16 Burke's vindication of the Glorious Revolution, in opposition to events in France, was thus also an implicit disavowal of those varieties of Whiggism more congenial not only to the language of abstract rights but also to a broader and potentially radicalized vision of seventeenth-century history. These “new Whigs,” he warned, risked sacrificing the true revolution principles of 1688 to the metaphysical chimeras of radical dissenters and seditious levelers.

The legacy of the Stuart revolutions clearly played a significant role in the shaping of Whig identities during the later eighteenth century and beyond. Our understanding of Burke's contribution to this process has been considerably advanced by the editorial reconstruction and ongoing scholarly exegesis of his long and various career as a writer and parliamentary orator.Footnote 17 But while a number of previous studies have demonstrated the enduring centrality of the Williamite revolution to Burke's ideological self-conception, we lack a comparably sustained investigation of his attitudes to the civil wars and interregnum.Footnote 18 Such neglect might seem justified. The parliamentary connection to which Burke allied himself in the mid-1760s, and to which he professed loyalty until the end of his life, was self-consciously composed of those “great Whig-Families” who viewed themselves as guardians of the 1688–89 settlement, “that interest which had brought about the revolution.”Footnote 19 And what made this latter revolution “glorious” for establishment Whigs was in large part its differences from the experience of 1640–1660, of civil war, regicide, Puritan zeal, and military usurpation. The Reflections has indeed frequently been understood as a locus classicus of such attitudes to seventeenth-century history. Nevertheless, it is argued here both that the first Stuart revolution played a more complex role in Burke's political consciousness than is often assumed, and that this aspect of his thought can be fully understood only by a sustained consideration of his public career in the decades preceding the 1790s.

These suggestions can claim some initial plausibility from Burke's Irish background, which left him with an enduring and peculiarly heightened sensitivity to the political and religious legacies of the seventeenth century, “those terrible, confiscatory, and exterminatory periods.”Footnote 20 Some such description, as Burke was well aware, could legitimately be applied not only to the history of Cromwellian invasion and “settlement” but also to the Irish Catholic experience of the 1690s.Footnote 21 It is well established that Burke maintained a keen interest in scholarly and polemical representations of seventeenth-century Irish history and what he regarded as its “most important part,” the period surrounding the rebellion of 1641.Footnote 22 His sympathetic attitude to revisionist treatments of the rebellion by Catholic scholars informed his enduring support for reform of the Irish penal laws and his broader disdain for the varieties of Protestant intolerance.Footnote 23 But Burke's historical sensibilities, and his adopted political vocabulary, were also those of an anglicized Whig, at a time when the lessons of the English revolutionary past were acquiring new meaning and application. Burke entered Parliament in the mid-1760s as the defender of a patrician and exclusive parliamentary corps, the self-appointed custodians of “revolution principles.” Yet his defense of that body took place within a larger and rapidly expanding political ecology, in which historical representations of the seventeenth century played a volatile and divisive role.

Those divisions were quickened by the accession of George III in 1760. Despite the new monarch's ambition to bury party divisions, his hostility to the continued hegemony of old-corps Whiggery and perceived receptivity to some form of “Tory” principles contributed to a revival and intensification of partisan rhetoric.Footnote 24 It had always been possible for court and opposition Whigs alike to excoriate the memory of the Stuart dynasty, but until the mid-eighteenth century such language drew much of its strength and legitimacy from a Jacobite threat largely extrinsic to parliamentary political culture. Now, however, opposition argument set itself against the threatened return of “Stuart-tyranny” at the heart of government.Footnote 25 Such language was increasingly familiar in the opposition press of the 1760s, betraying a new sensitivity to the polemical uses of English history within incipient forms of popular political organization and expression. And just as 1688 provided a “dissident legacy” in the hands of radicals and reformers, so the events of the mid-seventeenth century yielded a richly contestable historical resource for the political culture of the later Georgian period, including, in Kathleen Wilson's words, “a sustained effort to reinvent the events of the Civil War and Revolution as part of a legitimate indigenous radical tradition.”Footnote 26

The challenge for Burke, and his fellow Rockinghamite Whigs, was to harness the new forms of historical literacy generated by the popular politics of the 1760s while reasserting his party's proprietary claim to power and the more conservative reading of the seventeenth century that underwrote it. To these ends, his early political writings and speeches were forced to engage, often somewhat uneasily, with a larger historical narrative of resistance to Stuart despotism, stretching back from the Williamite revolution to the more compromised terrain of the civil wars. The difficulties of such an undertaking were only intensified by the looming confrontation with America, which was widely understood, on all sides of the conflict, with reference to seventeenth-century precedent. But the polemical uses of the civil wars and interregnum within English political argument were sustained well beyond the conclusion of the American war, with particularly significant consequences for Burke and his parliamentary colleagues. His invocations of the first Stuart revolution in the Reflections on the Revolution in France are, as a result, more various in their motivation than has often been assumed; nor can they adequately be understood without an appreciation of his party's shifting reputation within the popular political discourse of the preceding years.

I

The most important publication of Burke's early parliamentary career, Thoughts on the Cause of the Present Discontents, appeared in April 1770. This work would eventually achieve canonical status as a principled defense of party, but its immediate purpose was shaped by the dramatic events surrounding the Middlesex elections of 1768–69, in which the convicted libeler and anti-ministerial provocateur John Wilkes was returned to Parliament in three successive contests and repeatedly disqualified by the Commons from taking his seat. Burke wrote against the backdrop of a concerted petitioning campaign by Wilkes's supporters, popular disturbances, and the collapse of the Grafton ministry. The Present Discontents set out to exploit this state of affairs in order to advance the claims of Burke's party to political office. It was, the reviews declared, “a composition visibly framed in the Rockingham School,” a judgment that accurately reflected both the circumstances of its composition and the tendency of its argument.Footnote 27 Burke had worked closely with his colleagues over the previous weeks to produce a document that would give “the Publick in general … a fair state of our Principles,” while providing an unanswerable indictment of the court's secret influence and a bold defense of the Rockinghamites as the natural party of government.Footnote 28

That defense was predicated on a perceived continuity with “the great connexion of Whigs in the reign of Q. Anne,” in which period, not coincidentally, Burke also saw perfected the constitutional settlement of 1688–89.Footnote 29 These claims were quickly seized on by hostile commentators, for whom Burke was little better than an apologist for oligarchy. “A system of corruption began at the very period of the Revolution,” charged Catharine Macaulay, and the storied resistance to James II produced merely “a mode of tyranny more agreeable to the interests of the Aristocratic faction.”Footnote 30 Burke's argument undoubtedly drew on a nostalgic vision of the Whig party in the decades after 1688. But it also turned on the invocation of an earlier and less propitious revolutionary moment: “A sullen gloom, and furious disorder, prevail by fits; the nation loses its relish for peace and prosperity, as it did in that season of fullness which opened our troubles in the time of Charles the First. A species of men to whom a state of order would become a sentence of obscurity, are nourished into a dangerous magnitude by the heat of intestine disturbances; and it is no wonder that, by a sort of sinister piety, they cherish, in their turn, the disorders which are the parents of all their consequence.”Footnote 31 Burke's first readers were certainly alert to the pamphlet's “polished” and “elaborate” style, evident here in his recourse to ominously Miltonic diction (crossed with an ironic glance, in the “sentence of obscurity,” at the village Hampden and guiltless Cromwell of Gray's Elegy).Footnote 32 Yet this passage offers more than local literary color. Throughout the Present Discontents, Burke makes repeated minatory reference to the origins of the English civil wars, “the tumult of public revolutions,” and the “grievances … vindicated on the Stuarts,” as distant parallels for the present state of the nation.Footnote 33 And in this respect, his text also betrays its sensitivity to the role of seventeenth-century history in contemporary popular political argument.

Early Wilkesite polemic had been characterized by vituperative attacks on the “cursed race of Stuart” supposedly embodied in the king's favorite, the Earl of Bute, whose career and possible fate opposition writers frequently compared to those of Strafford and Laud.Footnote 34 By the end of the decade, however, such historical precedents could find application to a more pervasive sense of political corruption, seemingly prompted by “Complaints of such an impression, that for the pattern of them, we must go back beyond the Revolution.”Footnote 35 A series of issues in the later 1760s, with Wilkes and the Middlesex election at their heart, generated a groundswell of popular interest in English constitutional history, increasingly directed at the nation's revolutionary past as at once a precedent and a warning to the nation. The opposition press of the later 1760s was suffused with allusion to “Stuartism in Politicks” and comparisons between Wilkes's treatment and the iniquities of both Charles I and his sons.Footnote 36 The campaign in Wilkes's defense culminated in an incendiary remonstrance to the crown from the City of London, which claimed that Wilkes's exclusion was “a deed, more ruinous in its consequences than the levying of ship-money by Charles the First, or the dispensing power assumed by James the Second.”Footnote 37 The broader motives and attitudes underlying such historical references were, however, neither singular nor straightforward. Wilkes himself was courted by republican Whigs such as the political antiquarian Thomas Hollis, who provided him with prints and editions of seventeenth-century patriot heroes and was reputed, at least, to have awakened Wilkes's genuine enthusiasm for the works of Sidney and Locke.Footnote 38 Yet there is something more than unreflective reverence on display in contemporary prints of Wilkes alongside Hampden and Sidney (figure 3). They suggest a knowing appropriation of Whig symbolism in a determinedly new setting, in which the memory of such historical figures at once counterpoints and corroborates Wilkes's celebrity, their iconography assimilated to less deferential and exclusive forms of political communication.Footnote 39 The Stuart revolutions were thus remade in the image of Hanoverian popular radicalism and its media technologies. As one account of John Hampden's trial concluded, “The portrait and prints of Hambden and liberty appeared everywhere, while new signs of his picture were placed at every tavern and public house.”Footnote 40 This was “vulgar” Whiggism, to be sure, characterized by a jealous reverence for “ancient and indubitable rights and liberties” and a corresponding antipathy to David Hume's more skeptical understanding of the revolutionary past.Footnote 41 But it possessed a sophisticated self-awareness of its own, combining a burgeoning interest in the nation's political and constitutional past with vivid anecdote, the exemplary depiction of character, and a highly developed sense of historical representation as an inherently ideological instrument of extra-parliamentary activism.Footnote 42

Figure 3 English Liberty Established, or a Mirrour for Posterity (1768), BM.

For all their patrician prejudices, the Rockinghamites did not stand aloof from these developments. They contributed to the coordination of a nationwide petitioning campaign, in parallel with the activities of more radical, Wilkesite publicists.Footnote 43 In Parliament, meanwhile, Burke looked back to the reigns of Charles I and James II to exemplify both “popular passion, popular prejudice” but also “the justest causes of publick dissatisfaction.”Footnote 44 In doing so, he sought to exploit the popular opposition account of neo-Stuart corruption—the “rough, vulgar common sense” of the City of London's remonstrance, as Burke described it—while reasserting Rockinghamite claims to both political virtue and the historic legacy of Whig liberty.Footnote 45 The most significant such attempt, prior to the Present Discontents, was the Sentiments of an English Freeholder (1769) by William Dowdeswell, the leader of the party in the Commons. Dowdeswell defended Wilkes by invoking resistance to the practices of arbitrary government, including ship money and the Star Chamber, in “the times of the first Stuarts.”Footnote 46 But like another Rockinghamite pamphleteer, William Meredith, he also stressed the parallels between the exclusion of Wilkes and the Long Parliament's expulsions of members in 1640–1642. The clear implication was that the Commons was treading the same path that had culminated in Pride's Purge and a military despotism. This was a calculatedly equivocal use of seventeenth-century history, designed at once to appeal to anti-Stuart sentiment and to warn against the political “licentiousness” to which such attitudes had led in the 1640s.Footnote 47 The same allusive tendency characterized the speeches of Dowdeswell and Burke in the weeks before the appearance of the Present Discontents, and clearly underlies the claim, in that latter work, that the continued exercise of “arbitrary power” risked “the interposition of the body of the people itself” in the cause of the constitution.Footnote 48

The Wilkesite press was not blind to such warnings. As John Almon's Political Register satirically ventriloquized Burke's argument, “I see no chance of inducing the King to appoint us to be his ministers, but by hinting, that if he does not, the body of the people may interfere and remedy their own grievances: in other words, we may have a civil war, or another revolution.”Footnote 49 It was the self-interest of the Rockinghamites, rather than their alarmism, to which this writer objected. The imminence of popular resistance to the ministry's “tyrannical conduct” was frequently suggested by its opponents, in both Parliament and the press;Footnote 50 Burke himself was widely suspected to be the author of the notorious “Junius” letters, in which the king was explicitly threatened with the fate of delinquent Stuart monarchs.Footnote 51 Nevertheless, even as he raised the specter of “furious disorder” under Charles I, Burke stressed that “the circumstances are in a great measure new. We have hardly any land-marks from the wisdom of our ancestors, to guide us.”Footnote 52 Much as he sought to exploit the anti-Stuart prejudices of the Wilkesite press, Burke also claimed a more profound understanding of the past than that “retrospective wisdom, and historical patriotism”Footnote 53 implicitly identified with the Rockinghamites’ great rival for office, the recently ennobled William Pitt, Earl of Chatham.Footnote 54 And while the Present Discontents is primarily concerned with domestic politics, Burke's carefully equivocal attitude to the mid-seventeenth century cannot be fully appreciated without reference to the divisions between Chatham and the Rockinghamites on the most significant issue of imperial policy in this period: the nation's deepening confrontation with America.

II

With the advent of the Stamp Act crisis in 1765, Britain's deteriorating relations with its North American colonies were increasingly understood, by all sides in the controversy, with reference to the internecine conflicts of the mid-seventeenth century. A similar interpretative impulse has, of course, shaped much modern historiography. The extent and significance of the colonial revolutionaries’ familiarity with a putative canon of “commonwealth” argument, and their ancestral identification with politically dissident forms of sectarian Protestantism, remain important matters of contention.Footnote 55 It seems clear, however, that American publicists were willing to seek common cause with English popular radicalism by invoking a shared historical frame of reference. The Boston Sons of Liberty flattered Wilkes on his “perseverance in the good old cause” (perhaps as much in hope as expectation), while Burke's acquaintance, the Virginian Arthur Lee—writing as “Junius Americanus”—likewise sought to yoke colonial grievances with those of Wilkes's supporters, including repeated comparison between ministerial treatment of the Americans and the policies of the “ill-fated” Charles I.Footnote 56 From the late 1760s, English radicals similarly began to combine their topical reflections on the “most despotic tyrants of the house of Stuart” with reference to the oppressed Americans laboring under a similarly illiberal imperium.Footnote 57 They were answered in kind by their political opponents. “Shall we stay till some Oliver rises up amongst them?” demanded those parliamentarians urging resolution in the face of colonial recalcitrance, while out of doors pamphleteers denounced the Americans as Puritan zealots, possessed by “the same spirit which actuated your ancestors, and kindled the flames of civil war in this country.”Footnote 58 Naturally, such arguments did not accurately reflect the complexities of the situation, not least in respect of the constitutional issues at stake. Apologists for colonial taxation did not tire of pointing out that resistance to Charles I in the 1640s was undertaken in defense of the same parliamentary rights contested by the Americans; nor did they fail to notice the apparent incongruity of colonial appeals to the royal prerogative.Footnote 59 Yet the very force of such observations speaks to the centrality of historical argument and allusion within the escalating crisis and the increasingly antagonistic relationship between rival visions of the 1640s. Recourse to seventeenth-century precedent yielded two radically inconsistent historical narratives—of constitutionally sanctioned resistance and lawless rebellion—which, drawing strength from inherited prejudice, both fed upon and contributed to the growing polarization of opinion.

These circumstances raised considerable challenges for the Rockingham administration of 1765–66 and its “plan of moderation” in American affairs.Footnote 60 Committing itself early in 1766 both to the repeal of the Stamp Act and to Parliament's right to levy taxation on the colonies—as embodied in the Declaratory Act—the ministry was also anxious to conciliate Parliament, the king, and a restive public opinion. The colonial disturbances, it was claimed, had left the public “strongly impressed, with the fears of a rebellion on the continent of America.”Footnote 61 Such anxieties were eagerly stoked by the Grenvillite opposition, who insisted on describing recent events in America as “open rebellion” and associated the colonists’ “doctrine of representation” with “the Parliament which destroyed Charles 1st and the whole constitution.”Footnote 62 The latter suggestion appears, in turn, to have encouraged William Pitt to defend his assertion that “Taxation and representation have gone together” with defiant recourse to the memories of Hampden and Pym.Footnote 63 Burke's Present Discontents would later offer a tacit critique of such arguments in his observation, “When an arbitrary imposition is attempted upon the subject undoubtedly it will not bear on its fore-head the name of Ship-money.”Footnote 64 Certainly ministerial supporters, including Burke, studiously avoided such inflammatory associations during the debates on the Stamp Act. They were, however, increasingly hard to ignore and could indeed be turned to some account. One Rockinghamite pamphleteer urged caution in confronting the colonies on the grounds that “they are Englishmen, and many of them inherit from their Ancestors republican Principles, which they carried thither during the civil Wars.”Footnote 65 “It is not to be expected that the spawn of the old Cromwellians will submit without a blow,” warned another; “they will still find Scripture to justify their Covenant; the sword of the Lord and of Gideon will be once more drawn; and all Israel will take to their Tents to oppose the Egyptian Task-Masters.”Footnote 66 The tonal ambiguity of this remark is revealing. On the one hand, its exaggeratedly archaic scripturalism reads like a humorous attempt to undercut the alarmism with which the coercionist press invoked the “Fanaticism” of “Oliver's Time”; but it also seeks to exploit, for the Rockinghamite ends of conciliation, growing public anxiety at the atavistic zeal widely presumed to have motivated colonial resistance.Footnote 67

The American crisis of the later 1760s thus fostered the revival of an anti-Puritan imaginary, which may have been as much a cause as a consequence of growing sympathy for the colonists on the part of the English dissenting community.Footnote 68 While the radical press defended the seventeenth-century wellsprings of Anglo-American dissent as “the very life and soul of the republican part of our government,” they were increasingly challenged by a caricature of the nonconformist character, at once transhistorical and transoceanic, as the epitome of lawless, leveling sedition.Footnote 69 This tendency was fueled by the subscription debates of the early 1770s, as religious controversy returned to the English political agenda. In February 1772, a group of latitudinarian churchmen petitioned Parliament to remove the requirement for Anglican ordinands to subscribe to the Thirty-Nine Articles. In resisting the proposed reform, Burke found himself “in opposition to the opinions of nearly all my own party”; he betrayed, nevertheless, some ambivalence regarding the grounds on which the measure should be rejected.Footnote 70 A succession of speakers attacked the petition in terms calculated to play on prevailing prejudices, including references to the “anarchy and confusion” of the last century and the specter of “fifth monarchy men, civil war, insurrections.”Footnote 71 The newspaper report of Burke's speech suggests that he used a similar historical analogy in response, albeit given a more Rockinghamite, anti-court inflection: granted the liberty of conscience requested by the petitioners, “Men, for the sake of peace and quiet, would be forced to throw themselves into the hands of some dictator, as they did at the Restoration into those of Charles the Second.”Footnote 72 Yet Burke's subsequent notes on the debate indicate a more anxious circumspection concerning the tendency of contemporary political argument. “I wish,” he declared there, “that the dissensions & animosities, which had slept for a century, had not been just now most unseasonably revived. But if we must be driven, whether we will or not, to recollect these unhappy transactions, let our memory be compleat & equitable.”Footnote 73 It seems likely, as Paul Langford has argued, that these notes were intended for separate publication.Footnote 74 If so, Burke could have expected his readers to give his comments rather broader application. The Feathers Tavern petition coincided both with bills for the relief of Protestant dissent and with the ongoing controversy surrounding Thomas Nowell's recent 30 January sermon before the Commons, in which the preacher had likened the regicides of 1649 to those “men, who have artfully revived those disputes in the church, and clamors in the state, which once terminated in the ruin of these kingdoms.”Footnote 75 Such sentiments were echoed by several contemporary defenders of the ecclesiastical status quo, frequently with reference to America. As Burke himself noted, in the Lords debates on dissenting relief of 1772, the bishop of Bristol complained: “We know very well what an intolerant spirit possessed the Dissenters in the last century, while they had the power in their hands. We know it at this day, by their opposition to the establishment of a Bishop in America.”Footnote 76 Burke's attempts to combine support for religious toleration with a more conservative attachment to the Anglican establishment marked him out from those of his colleagues, such as the Duke of Richmond, who were convinced that the dissenters’ “Religious Principles & our Political ones are so very similar, & most probably will make us generaly act together.”Footnote 77 As Burke seems to have realized, however, by the mid-1770s, such a prospect carried with it a growing danger of association with both the American rebellion and its supposed harbingers among the Puritan revolutionaries of the previous century.Footnote 78

Burke's great speeches on American conciliation of 1774–75 reflect that awareness, as well as his continued desire to combine an insistence on the “proper subordination of America” with his long-standing acknowledgment of the constitutional liberties claimed by the colonists.Footnote 79 Those speeches also suggest an attempt to neutralize the powerful seventeenth-century precedents that threatened to destabilize Rockinghamite policy on America. The latter possibility arose early in the debate on the tea duty of 19 April 1774. This first move for conciliation was immediately supported by Richard Pennant, who advanced the distinctly Chathamite argument that the tax removed from the colonists the “sacred” power of “levying their own money … it was similar to raising the ship money in King Charles's time.”Footnote 80 Burke's own contribution to the debate engaged directly with Pennant's argument: he too invoked “the feelings of Mr. Hampden when called upon for the payment of twenty shillings” in vindication of the “feelings of the Colonies.” Yet even as he did so, Burke tacitly undercut the deeper constitutional arguments about parliamentary representation popularly associated with the ship money case; the “principle” currently at issue, he insisted, in conformity with the Declaratory Act, was the “expediency” of raising a revenue, not the right of doing so.Footnote 81 Burke's climactic assertion that “subordination and liberty may be sufficiently reconciled” evidently required a strategic reframing of Whig historical shibboleths in an attempt to outmaneuver those more “vulgar & unphilosophic” appeals to popular opinion that he continued privately to associate with Chathamite rhetoric.Footnote 82

By the time the Speech on American Taxation was published in early 1775, such circumspect treatments of the nation's revolutionary past were increasingly difficult to sustain. The friends of America were now confirmed in their recognition of a disturbing historical parallel between the present crisis and those of the seventeenth century, exacerbated by the Quebec Act and the apparent recrudescence of neo-Stuart popery and arbitrary government.Footnote 83 Burke's defense of parliamentary right was accordingly savaged by John Cartwright, who compared his arguments to the “impious dogma of Filmer … the champion of illimitable sovereignty.” If the gathering conflict did indeed replay the “long afflicting civil war,” Cartwright promised, it would bring forth its own “Sydneys, Lockes and Miltons.”Footnote 84 Burke and his party emphatically did not number among them, despite their nominal adherence to what Fox termed the “true constitutional Whiggish principle of resistance.”Footnote 85 But the Rockinghamite position was also deeply unpalatable to coercionists, anxious to discipline the colonial “fanatics” whose “blood-thirsty, and rebellious progenitors” were routinely traced back to 1649.Footnote 86

Burke nevertheless remained highly active in attempts to concert popular “support without Doors” and was closely involved with the petitioning campaign against the American war in 1775.Footnote 87 His 22 March speech on conciliation (published three months later) may be regarded as a further, desperate effort to halt the drift toward confrontation by appealing to both parliamentary and popular opinion. In this respect, it is significant that he now realized the necessity to address not just policy but also the degree to which the American crisis had become indissolubly bound up with rival historical perceptions of “the great contests for freedom in this country,” including the seventeenth-century controversies over “the question of Taxing” and the portentous circumstances in which the Puritan colonists had first left England.Footnote 88 These considerations inform Burke's well-known and shrewdly ambivalent observation: “All protestantism, even the most cold and passive, is a sort of dissent. But the religion most prevalent in our Northern Colonies is a refinement on the principle of resistance; it is the dissidence of dissent; and the protestantism of the protestant religion.”Footnote 89 The “dissidence of dissent” plainly suggests Burke's long-standing sensitivity to the more rebarbative aspects of the Protestant temper. A similar concern is evident in his early collaborative work with William Burke, An Account of the European Settlements in America (1757), which stressed both the “high spirit of liberty” and the intolerant, persecutory inclinations of many early seventeenth-century colonists.Footnote 90 But the speech on conciliation also reflects the more urgent, tactical demands of political argument in the mid-1770s. If Burke's references to the Puritan settlement of the northern colonies make a tacit concession to coercionist prejudice, his allusion to the “principle of resistance” also parallels earlier Rockinghamite attempts to reappropriate the historical touchstones of revolution Whiggery.Footnote 91 The colonists left England, Burke wrote elsewhere, in possession of a “republican religion,” the “most unmanageable part of an unmanageable people”; yet they could also be identified with that “Barbarous & Rustick [love] of Liberty” that had been refined and perfected by the Whig heirs of 1688.Footnote 92

The rhetorical subtlety of Burke's performance did not sway the government's course. Indeed, once George III had declared the colonies to be in “open and avowed Rebellion,” the opposition was ever more vulnerable to the simple charge of seditious disloyalty.Footnote 93 The minority were now routinely attacked as false patriots, venal and self-interested hypocrites.Footnote 94 Rockingham was a man of “disappointed ambition … pusillanimity and treachery”; invocations of 1688 and “justified resistance” were mere cant, “very different, surely, from what has caused the present unprovoked rebellion in America.”Footnote 95 The more appropriate historical precedent for Whig opposition to the war was clear enough to many commentators: “To poison the minds and alienate the affections of the people has been their constant care; to propagate the republican doctrines of the last century their daily practice.”Footnote 96 Yet if Burke's party thus found itself increasingly defined by its “blue and buff” support for republican rebels, they could not have foreseen the ways in which their association with colonial revolution, and its historical antecedents, would continue to color their reputation in domestic politics over the years that followed.

III

On 8 June 1780, Edward Gibbon reported the shattering of London's “public tranquillity” in the worst civil disorder of the century: “Forty thousand Puritans such as they might be in the time of Cromwell have started out of their graves, the tumult has been dreadful.”Footnote 97 The outburst of confessional violence that marked the Gordon riots struck many contemporary observers in similar terms, and has indeed been claimed as a remote source for the anti-Puritan rhetoric of Burke's Reflections.Footnote 98 But while the riots undoubtedly provided him with a visceral (and personally hazardous) reminder of the destructive energies of Protestant enthusiasm, the larger political context of this period is also crucially important for our understanding of Burke's subsequent counterrevolutionary stance.Footnote 99 As Nicholas Rogers has shown, the Catholic Relief Act of 1778, which precipitated the riots, was closely bound up with the politics of the American war.Footnote 100 Popular opposition to the government was already conditioned by the Quebec Act to regard the government's measures with suspicion. This may well explain the otherwise paradoxical fact that opposition politicians—including prominent Rockinghamites who had supported Catholic relief—were cheered by rioters as they entered Parliament, a circumstance that was not lost on hostile government pamphleteers.Footnote 101 Contemporaries soon realized that the backlash against the riots might offer “strength to administration, which few other events could at that time have produced.”Footnote 102 They came at the end of a concerted extra-parliamentary campaign for parliamentary reform, which, like the political crisis of the late 1760s, the Rockinghamites had attempted to turn to their own purposes.Footnote 103 Opponents of the reformist Association movement argued that the “republican doctrines, which have been disseminated for some time,” risked a “reiteration of the scenes of Charles the First”; but the parliamentary opposition were also seemingly willing—as they had been in 1770—to magnify the threat of popular resistance for tactical ends.Footnote 104 Thus, while the eccentric figure of George Gordon may have been the most recognizable “modern Puritan” of this period, his activities also provided a focus for that broader preoccupation with the legacy of the civil wars that, as discussed above, had been gathering momentum since the 1760s.Footnote 105 The American conflict had tarnished Burke's party by association with lawless rebellion; it also introduced a dangerously polarizing idiom into domestic politics that, together with the volatile state of Ireland and popular reformist agitation in England, raised widespread fears of civil conflict in the first months of 1780.Footnote 106

Those anxieties quickly receded in the wake of the riots, while military success in America further strengthened the government's hand. Yet within two years, the colonies were as good as lost, and Lord North had finally persuaded the king to accept his resignation. North's departure in March 1782 presaged the short-lived second Rockingham administration, dedicated to the long-meditated task of uprooting the court's corrupt influence. Its achievements in this respect were, however, destined to be overshadowed by a constitutional crisis that would have profoundly detrimental consequences for Burke and his party. The Fox-North coalition, formed after Rockingham's death, quickly attracted hostile commentary for its political opportunism, a criticism compounded by the storm over the East India Bill. The bill's critics charged that it represented an illegitimate aggrandizement of parliamentary power at the expense of the crown; Fox's supporters, in turn, were outraged by the king's seemingly unconstitutional attempts to thwart the passage of the legislation. The consequent disintegration of the coalition led to the disastrous 1784 election and the consolidation of the Pitt administration, which would retain power for the remainder of Burke's life.

These circumstances were accompanied by a further, and highly damaging, exercise in historical parallelism, for the controversy surrounding the East India Bill provided an opportunity to revive and refocus the now familiar association of the Rockingham party with the fomenters of civil war. The Earl of Abingdon opened the Lords debate on the bill in dramatic fashion, with the repeated accusation that Fox and his supporters were moved by “ambition no less violent than that which filled the mind of Cromwell, and brought the head of Charles I. to the block.”Footnote 107 The charge was egregiously hyperbolic, to be sure, but the comparison was immediately adopted by journalists, pamphleteers, and, indeed, the counsel for the East India Company. It was thus ominously significant that Abingdon went on to cite Burke's Present Discontents as the “creed” of the “Oligarchical Junto” behind the legislation.Footnote 108 As the prime movers of the East India Bill within the coalition, the Rockingham-Fox connection was consistently depicted in the months that followed as a band of “Usurpers and Tyrants,” anxious to pull down the throne under speciously libertarian pretenses and betraying motives worryingly redolent of the 1640s.Footnote 109 A large part of the appeal of such language lay in its relation to the popular political discourse of the previous decade. Wilkesite radicalism and the existential struggle for the North Atlantic empire had reactivated and intensified memories of civil war, Puritan rebellion, and Stuart tyranny; now that the Foxites found themselves in power, they appeared intent on replaying the subsequent descent of parliamentarian resistance into Cromwellian despotism.

Of course, the stakes were much lower, as almost all the participants appear to have recognized—including Fox, who warned the Commons rather lamely in December 1783 that a dissolution “must produce every calamity of a civil war, short of blood.”Footnote 110 This, however, did not make the historical analogy any less compelling—or entertaining—for the public. Febrile warnings of revolution and earnest constitutional argument were thus combined with the playfully self-conscious, and often highly ironic, deployment of Cromwellian tropes. James Sayers's print The Mirror of Patriotism, which appeared in January 1784 (figure 4), exemplifies the increasingly satirical treatment of Fox as an incongruous, latter-day Lord Protector. Sayers emphasizes Fox's vanity, hinting at his frequently declared identification with seventeenth-century resistance to Stuart tyranny; but the print remains shrewdly reticent as to whether he should be regarded as the comical victim of self-deluded hubris or as a more sinister, Machiavellian manipulator of his public image. The Mirror of Patriotism was soon joined by further visual and printed satires in the same vein, stimulated by the general election campaign of the spring and Fox's closely fought contest in Westminster.Footnote 111 The borough's electors were treated to a seemingly endless stream of satire and polemic depicting Fox as a “second Cromwell,” a usurping, hypocritical tyrant striving “to set himself up above the laws of his country.”Footnote 112 Even his manifest inadequacy as a model of Puritan moral rectitude provided grist for Fox's enemies: despite their superficial differences, it seemed, “Cromwell's Saints” were guided by the same subversive ends as “F-x's Sinners.”Footnote 113 The preponderance of such attacks in Westminster—a notoriously open constituency—suggests their potential appeal to a wide spectrum of opinion. Supporters of the old war ministry would recall the coercionist disparagement of Rockinghamite “rebels” in league with the revived spirit of Puritan resistance in the colonies. But many radicals and dissenters, too, were ready to see the parallels between Foxite oligarchy and the Cromwellian betrayal of the good old cause.Footnote 114 Not only had Fox, the self-styled “man of the people,” entered office with the detested Lord North, but his reformist credentials were under serious challenge from the younger Pitt. Fox and his supporters were adamant that they were witnessing a revival of Stuart prerogative.Footnote 115 Yet the Whig leader's attempts to seize control of government patronage were also suggestive of the truth, hard learned by the English people in the 1650s, that “in Republican Governments, the people are necessarily betrayed by those in whom they trust.”Footnote 116

Figure 4 James Sayers, The Mirror of Patriotism (London, 20 January 1784), BM Sat. 6380.

The 1784 general election was a shattering experience for Burke, reinforcing both his growing distrust of popular politics and his reservations concerning Fox's more opportunistic appeals to extra-parliamentary sentiment. “The people did not like our work,” he bitterly reflected in its aftermath, “and they joined with the Court to pull it down.”Footnote 117 The Whig opposition was left in a troubling predicament. Opponents of the war with America, including Burke, had previously warned that the North ministry, “having plunged us in all the evils attending a civil war, will endeavour, as a coup de grace, to shelter themselves under the cover of arbitrary power”;Footnote 118 now “the people” had been persuaded to identify the spirit of usurpation with their natural representatives, the party of Rockingham and Fox.Footnote 119 Constitutional liberties, Burke concluded, were in as dire a state as during the Tory reaction “at the End of the reign of Charles the second.”Footnote 120 This made it all the more frustrating that, much like his father, Pitt also seemed intent on wresting the sacred mantle of revolution principles from Burke's party, first in relation to the constitutional conflict of 1783–84, but then again during the Regency Crisis of 1788–89.Footnote 121

This latter episode is usually represented as the nadir of Burke's public reputation, during which he apparently succumbed to an emotional extravagance verging on the pathological. Yet the extremes of his rhetoric in the Regency debates may be explained in part as a calculated response to the dizzying ideological reversals that had accompanied the decline in his party's reputation. With George III in a state of mental incapacity, the Foxites pushed hard for the immediate and unqualified recognition of the Prince of Wales as regent. They did so, however, in a manner that allowed Pitt to present himself, once again, as the guardian of the mixed constitution bequeathed by the revolution of 1688–89. Parliamentary limitations on the regency, Pitt insisted, found their precedent in the Convention of 1688; Fox was cynically reverting to the Toryism of his ancestors by insisting on the indefeasible right of the Prince of Wales.Footnote 122 Burke's response was, firstly, to differentiate 1788 from events of a century before by insisting on the “necessity” of the glorious revolution, “above precedent & above Law”—a position that he would develop at greater length in the Reflections.Footnote 123 He went on, however, to argue that Pitt's proposal to subject the regent's powers to parliamentary limitation threatened to subvert the constitution.Footnote 124 This attack on the principle of hereditary monarchy recalled “all the long train of evils attendant upon the distractions of ill-guided and unprincipled Republicks.” Having discarded their own “Toryism,” the ministers had become “fifth Monarchy-men, and the wildest of Republicans.”Footnote 125 A month later, Burke complained that the Commons would not sit on 30 January, the anniversary of the regicide, which he pointedly described as the “most fit for taking that step, which was to annihilate the constitution, and to change the form of our government.”Footnote 126 When viewed within the larger polemical context traced above, Burke's language on these occasions betrays not simply emotional intemperance but a calculated attempt to appropriate and redirect the rhetoric of his party's opponents: just as the Foxites had been repeatedly identified with Puritan rebellion by their enemies, so Burke attempted to deflect such accusations back upon Pitt. The press responded with the familiar insinuation that the Foxites were in pursuit of the crown, and that Burke—in his own, unfortunate phrase—would welcome the spectacle of George III “hurled … from his Throne.”Footnote 127 Such attacks were, it should by now be clear, continuous with his party's long-standing pejorative identification with the spirit of regicidal usurpation. Those associations would, however, soon find a new and culminating focus in the looming controversy over revolutionary France.

IV

The immediate catalyst for the composition of the Reflections on the Revolution in France, in the form in which we know it, may be dated with some precision to a dinner conversation near the end of January 1790. As Burke later recalled, a dissenting friend took the opportunity to complain that the majority of his coreligionists “never could be reconciled to us, or confide in us, or hear of our being possessed of the Government of the Country, as long as we were led by Fox.” Burke later claimed to have engaged in a strenuous defense of his colleague, “as I thought the Duties of Friendship, and a matter that touched the publick Interest, required.” That night he read Price's Discourse on the Love of our Country for the first time, in which he discovered both “seditious principles” and “personal invective against Mr Fox.”Footnote 128 It seems to have been this experience that persuaded him to undertake a published response to Price, which grew, over the next few months, into the opening section of the Reflections. In fact, Burke's attitude toward Fox was at this point considerably more ambivalent than his retrospective comments suggest, and in the course of 1790 their political differences moved decisively into the open.Footnote 129 As has long been recognized, Burke wrote the Reflections in “the service of party”: it was an attempt at once to detach Fox from more radical influences, to rebuke his party's leadership for their neglect and indifference, and to reaffirm Burke's own vision of true Whig principles in response to the French Revolution and its dissenting supporters.Footnote 130 These motives shaped both the rhetorical strategy of Burke's attack on Price and its relation to the complex political meanings assumed by the nation's revolutionary past over the preceding two decades.

The publication of Price's Discourse at the end of 1789 coincided with a revived campaign for repeal of the Test Acts, in which the principles of the Glorious Revolution were repeatedly invoked by dissenting activists in defense of the “general spirit of toleration.”Footnote 131 A widespread Anglican backlash quickly followed, insistently recalling the public to the memory of an earlier Stuart revolution, that “Grand Rebellion” in which the nation was plunged into the “unrelenting fury” of civil war and “the constitution totally subverted by a daring usurper.”Footnote 132 In March 1790, Burke broke decisively with his party over the issue of dissenting relief, announcing his changed opinions on the basis of “information lately received.”Footnote 133 He had already declared his opposition to the French Revolution, and it was at this point, too, that he undertook a “substantial draft” of his response to Price.Footnote 134 The nature of that response, when published in the Reflections in November, bore a distinct resemblance to the anti-dissenting campaign of early 1790. Burke's identification of Price's sermon with the “rapture of 1648” was clearly anticipated in contemporary Anglican polemic, and there is strong evidence that Burke drew directly upon the pamphlet literature of this period, including A Look to the Last Century, which not only provided a documentary source for Burke's criticisms of Price but also offered a sustained comparison between the ambitions of contemporary dissent and the “anarchy and confusion” of the 1640s, “a period when hypocrisy and pretended reformation overturned the constitution and enslaved the nation.”Footnote 135

Such associations must have contributed a great deal to the sense of outraged betrayal on the part of Burke's dissenting and reformist Whig readers. The Reflections was not, however, as his critics charged, an act of unprincipled apostasy; it is generally agreed that Burke recognized in Price and his allies an ideological extremism far removed from the pragmatic moderation of old dissent.Footnote 136 Nevertheless, the rhetorical character of Burke's attack seems to demand additional explanation. His religious sensibilities—broadly tolerant and “latitudinarian” in character—certainly do not suggest an immediate affinity with the reflex anti-Puritanism of high-flying ecclesiastical controversialists. Burke (like his readers) was also surely aware that the historical prejudices exploited by the anti-dissenting campaign of 1790 owed a great deal to the coercionist arguments of the American war. According to their critics, the dissenters’ support for colonial rebellion vindicated their identification with the “turbulent republicans” of the previous century, in much the same way in which the Rockinghamites’ disloyalty had been condemned after 1776.Footnote 137

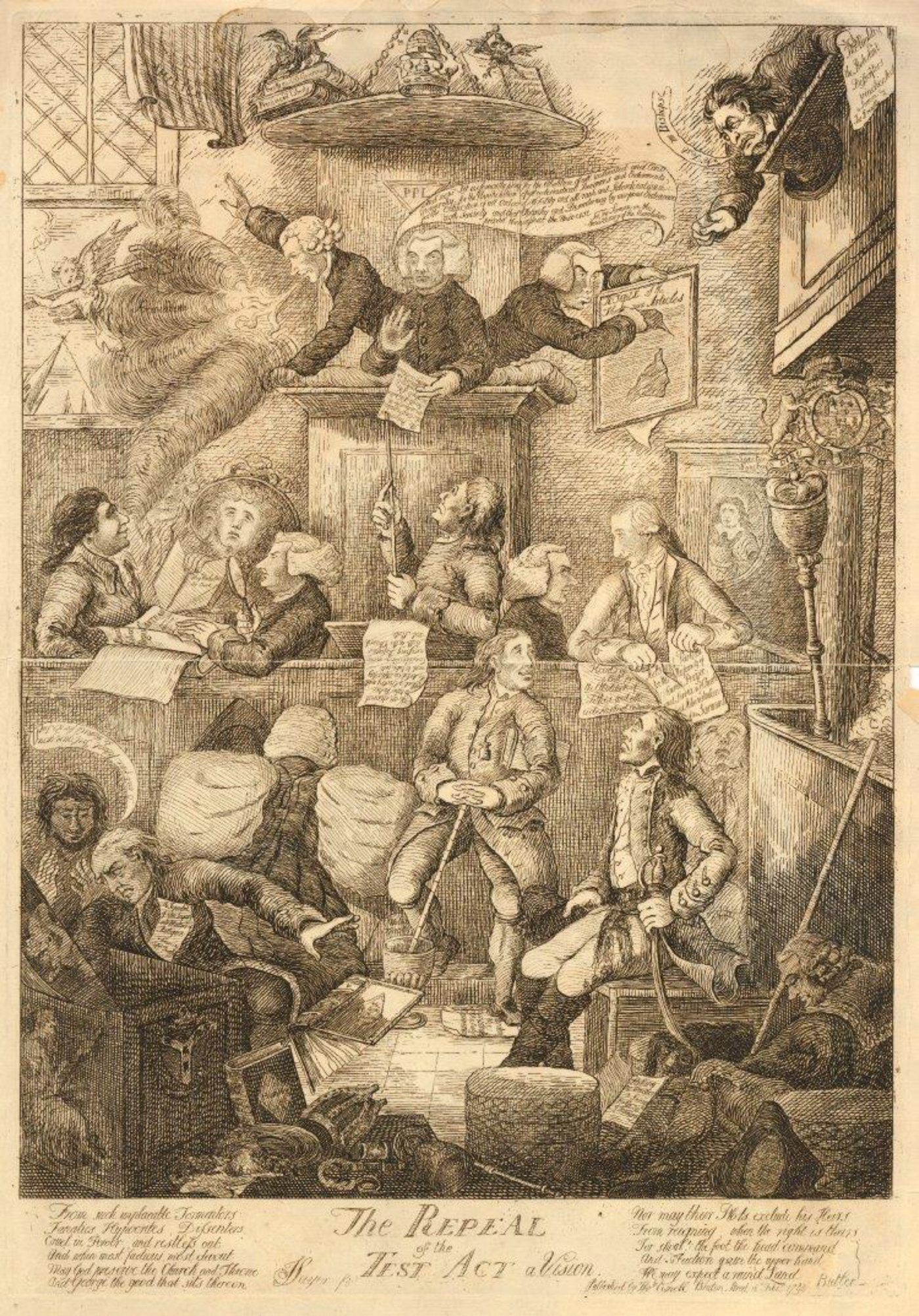

This latter consideration assumed particular significance since the dissenting cause—and Price's “noble sentiments”—were prominently supported in Parliament by Fox and a number of his allies. The Whig leader attended dissenters’ meetings, spoke in favor of the repeal motions of 1787 and 1789, and sponsored that of March 1790.Footnote 138 It was thus entirely predictable that James Sayers's satirical print of February 1790, Repeal of the Test Acts, should have portrayed Fox attending raptly to a dissenting pulpit occupied by Priestley, Price, and Theophilus Lindsey (fig. 5). Nor was it surprising that the details of the print should have included depictions of a puritan soldier, allusions to the Stuart regicide, and a portrait of Oliver Cromwell.Footnote 139 Sayers clearly recognized the potential for reviving the historical associations that had done so much damage to the Foxites’ reputation in recent years. Fox acknowledged as much himself in the parliamentary debate on dissenting relief of 2 March 1790. After confessing his differences from Burke, he went on to note that “the tongue of slander might possibly represent him as another Oliver Cromwell attacking the church; he had been compared to that usurper on a former occasion as attacking the Crown, even by the very men whose cause he was now pleading.”Footnote 140 Burke could at least concur with Fox on this last point, although he drew an opposite lesson. Responding to a request for support from a Bristol dissenter in 1789, Burke reflected reproachfully on the “great Change” that had taken place in 1784, when the dissenters “held me out to publick Odium, as one of a gang of Rebels and Regicides, which had conspired at one blow to subvert the Monarchy … and totally to destroy this Constitution.”Footnote 141 In identifying Price with Hugh Peters, “the mad chaplain of Cromwel” (as Hume had described him), Burke drew knowingly on the kinds of historical prejudice that had swelled the war effort against America and had been repeatedly directed at his own party ever since.Footnote 142 But he did so in order to dissociate that party and its principles from their long-standing and destructive link to the “Rebels and Regicides” of the previous century. By condemning Price as a Puritan fanatic, he signaled alarm at the increasingly radicalized language of natural rights associated with rational dissent; yet he was also using a form of attack that was calculated to make it as uncomfortable as possible for Fox to maintain his support for the French Revolution and its dissenting allies.

Figure 5 James Sayers, The Repeal of the Test Act: A Vision (London, 16 February 1790), BM Sat. 7628: An attack on “Fanatics, Hypocrites, Dissenters.” Fox is seated beneath the pulpit on the far left; a portrait of Cromwell occupies a corresponding position on the right of the scene. At the feet of the seated Cromwellian soldier, grasping his sabre, is a book entitled “Killing no Murder a Sermon for the 30th of January.” The text below is adapted from Samuel Butler (attrib.), “The Character of a Fanatic,” a work of seventeenth-century anti-Puritanism.

In this respect, of course, Burke failed. Fox continued to regard events in France as the first step toward a reformed constitutional monarchy. He was also apparently unembarrassed by the Reflections’ hostile allusions to the civil wars and Stuart regicide and, indeed, tacitly answered them in the debate on the Quebec Bill of May 1791. In respect of “original rights,” Fox insisted in response to Burke's speech, the legitimacy of “the resistance of the parliament to Charles 1st, and the resistance of 1688,” stood or fell together (the king's trial and execution was a different, and rather more delicate, matter).Footnote 143 Fox had some justification for regarding this position as an issue of party orthodoxy, and it is certainly true that Burke never publicly contradicted the conventional Whig approbation of parliamentary resistance in the early 1640s.Footnote 144 Yet Burke's attitude in the Reflections to the religious and political crisis of the mid-seventeenth century was clearly rather more complex than this, and closely informed by the vicissitudes of his party's reputation over the previous decades. At important moments during these years, such as the Middlesex Election and the eve of the American Revolution, Burke had conjured the events of the 1640s in a contrivedly ambivalent manner, in order both to exploit the popular anti-Stuart idiom of opposition politics and to warn of the potent energies of political and religious liberty in extremis. His party's growing identification with American rebellion and anti-monarchical conspiracy made such a position increasingly vulnerable and, I have suggested, provided a crucial impetus to his efforts in the Reflections to dissociate the principles of 1688 from the “revolution which happened in England about forty years before.”Footnote 145

But what part does the memory of the civil wars—and their prominent role within later eighteenth-century politics—play in Burke's analysis of the French Revolution itself? He certainly intimates in the Reflections and elsewhere that both the philosophes and their English admirers are broadly analogous to seventeenth-century enthusiasts in their fanatical “spirit of proselytism.”Footnote 146 Yet when Burke embarks on a more sustained and explicit comparison between the first Stuart revolution and that of 1789, he offers a strikingly different analysis, which nevertheless continues to bear closely on the growing divisions within the Whig party. Having recounted the many “undisguised calamities” afflicting France—the subversion of royal authority, constitutional confusion, and economic crisis— Burke confidently asserts that “the cause of all was plain from the beginning.”Footnote 147 It lies, he suggests, in the social composition of the revolutionary government. The elected deputies of the Third Estate consisted largely of unlearned provincial lawyers of a quarrelsome and litigious character. Along with the “mere country curates”Footnote 148 comprising the clerical estate, such men were bound to fall victim to manipulation by self-interested members of the nobility, who were happy to betray the interest of their class in the pursuit of individual power. It is in the context of this point—on the political virtues of aristocratic solidarity—that Burke makes his famous claim: “To be attached to the subdivision, to love the little platoon we belong to in society, is the first principle (the germ as it were) of public affections.”Footnote 149 And it is here, too, that Burke engages in the Reflections' most complex and extended treatment of the seventeenth-century civil wars.

Burke proceeds to exemplify the betrayal of local attachments, or “the little platoon,” with reference to “the time of our civil troubles in England,” and the behavior of turncoat nobility such as the Earl of Holland, “men who helped to subvert that throne to which they owed, some of them, their existence, others all that power which they employed to ruin their benefactor.”Footnote 150 Like the Reflections' other references to the mid-seventeenth century, this passage also offers a discreet but pointed commentary on Whig party politics. It does so on the basis of Burke's observation, in connection with Holland's reputation, that “Turbulent, discontented men of quality, in proportion as they are puffed up with personal pride and arrogance, generally despise their own order.”Footnote 151 Burke's modern editor is correct to identify in these words a thinly veiled criticism of reformist Whig noblemen such as Richmond, Lauderdale, and Bedford. But the allusion invites sharpest application to Fox, who was well on his way to assuming leadership of this group.Footnote 152 As Bulstrode Whitelocke had observed in his Memorials of the civil war period (in a passage reproduced in Rapin's History of England), Holland, although a “very great friend to the old Puritans,” was nevertheless executed after a vote by the Long Parliament. His fate, Whitelocke concluded, “may be a caution to us against the affectation of popularity.”Footnote 153 Hume's verdict was just as cuttingly apposite to Fox's reputation after the coalition of 1782: “His ingratitude to the King, and his frequent changing of sides, were regarded as great stains on his memory.”Footnote 154 The implication for the Foxites is clear: if they choose to abandon the traditional principles and loyalties of their party, they will not be remembered alongside aristocratic patriots such as Russell and Sidney but will be associated rather with the perfidious and power-hungry opportunists of both 1640s England and contemporary France. Burke's celebrated remarks on the “little platoon” evidently bear a nearer connection than is often realized to that idealized self-image of the old Rockingham party as a “snug chaste corps” of aristocratic virtue.Footnote 155

This context both determines and complicates the next turn taken by Burke's argument, for he goes on to invoke the memory of Oliver Cromwell, the historical figure whose pejorative association with Fox—as the type of a false patriot and usurper—had been firmly established in public consciousness since the early 1780s. Cromwell and his fellow “disturbers,” Burke argues, “were not so much like men usurping power, as asserting their natural place in society. Their rising was to illuminate and beautify the world. Their conquest over their competitors was by outshining them. The hand that, like a destroying angel, smote the country, communicated to it the force and energy under which it suffered. I do not say (God forbid) I do not say, that the virtues of such men were to be taken as a balance to their crimes; but they were some corrective to their effects.”Footnote 156 Much might be said about the suppressed awareness in this passage of the terrible violence visited upon Burke's own homeland by the Cromwellian army, which he would dismiss in 1792 as “the mercenary soldiery of a Regicide Usurper.”Footnote 157 But there is also a deeper irony in the contrast effected here between Cromwell and Holland, Burke's surrogate for apostate radical Whiggery. On the one hand, the ambivalent portrait of the Puritan general negotiates, and seeks partly to defuse, the pejorative Oliverian associations of the Whig opposition since the early 1780s. But conversely, Burke also implies, if the Whig elite betray their own “natural place in society” at the head of an aristocratic party, they will not even deserve the reputation of Cromwell and his fellows, who “aimed at the rule, not at the destruction of their country.”Footnote 158

Burke's treatment of Cromwell culminates in a comparison between his character and that of French statesmen (both Protestant and Catholic) of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Although this was a period of “civil confusions,” France had nevertheless—like England—managed to recover from prolonged internal conflict: “Why? Because, among all their massacres, they had not slain the mind in their country. A conscious dignity, a noble pride, a generous sense of glory and emulation, was not extinguished. On the contrary, it was kindled and inflamed. The organs also of the state, however shattered, existed. All the prizes of honor, all the rewards, all the distinctions, remained.”Footnote 159 This passage clarifies why, for all his reservations, it remained vitally important for Burke to deny the comparability of the 1640s and contemporary France. Cromwell's qualified virtues—which Burke would return to elsewhere—speak to a much larger set of values and institutions.Footnote 160 Honor, distinction, the “sense of glory and emulation”: these are recognizably the fruits of that “mixed system of opinion and sentiment” traced elsewhere in the Reflections back to the spirit of chivalry underlying modern European civilization.Footnote 161 On this basis were grounded the distinction of ranks, and the rights of property. Both were imperiled in France, yet they had apparently retained their force in England through the long struggles against Stuart oppression, in both the 1640s and 1680s. The execration of the Foxite party as “rebels and regicides” may have forced Burke to adopt the rhetorical posture of the party's enemies in an attempt to win his colleagues back from the lure of Jacobinism. Yet he could not, finally, identify the first Stuart revolution with the epochal rupture augured in France. Instead, rather than seeking to justify that earlier revolution in the constitutionalist idiom of resistance, Burke attempted in the Reflections to accommodate it to the more circumspect terms of a conjectural or “philosophical” account of European civilization premised on the history of manners and sentiment.Footnote 162 That account has often been regarded as the intellectual heart of the Burke's counterrevolutionary argument; it remains, however, in subtle tension with a more localized concern to vindicate the principles of his party, and his consequent attempts to exploit the anti-Puritan prejudices that had done so much to shape its reputation.

V

Perhaps predictably, the complexities of Burke's attitude to the civil wars and interregnum were largely ignored by the Reflections’ early readers. The most sophisticated reply to the book from a reformist Whig perspective, James Mackintosh's Vindiciae Gallicae, responded to his treatment of Price by offering a relatively conventional defense of Charles I's trial, qualified with reference to the evils of “fanaticism” and “military usurpation.” Burke was not just assumed to have held opposing sentiments to these; Mackintosh insinuated, through an extended parallel between Burke and Judge Jeffries, that his animus against Price betrayed the same ideological prejudices that had motivated the execution of Algernon Sidney.Footnote 163 According to another hostile reader, Burke simply “knows no distinction between … a Jack Cade and a Hampden, a Peters and a Price.”Footnote 164 Yet Burke himself remained rather more discriminating in his attitudes to the Whig canon of seventeenth-century patriots. As late as 1792, he was prepared to concede the Foxites’ identification with “Hampden, Hyde, and other reformers of those days,” albeit to warn that “the beginners of any … reformation never saw it ended.”Footnote 165 Even as Burke's reference to Clarendon's early opinions offers a knowing subversion of conventional Whig hagiography (and the fickleness of a “reformist” reputation), he also nods here to the conventional distinction between legitimate parliamentary resistance and the licentious rebellion into which it degenerated, now implicitly associated with the threat of Jacobin ideology.

This was some distance from other, less considered manifestations of counterrevolutionary opinion, which were given additional strength by the execution of Louis XVI the following year. The mid-seventeenth century became, for many of Burke's keenest admirers, an unrelievedly “black and horrible period,” wholly unqualified by any lingering Whiggish equivocations.Footnote 166 By September 1793, Burke himself was privately expressing his solidarity with French emigrés with reference to royalist martyrs of the 1640s, while his ambivalent feelings about Pitt would later suggest a comparison with the flawed but heroic character of Charles I.Footnote 167 It is remarkable, however, that such parallels did not become a prominent feature of his post-regicidal publications. Burke continued to stress the novelty of the French Revolution, “this new and unheard of power,” and its fundamental divergence from English historical precedent.Footnote 168 It was, he alleged in 1795, the English Jacobins who “have never failed to run a parallel between our late civil war and this war with the Jacobins of France.”Footnote 169 There was some justification for such a claim: the behavior of European powers during the 1650s was a recognized precedent for making peace with a regicidal regime, while the increasingly repressive inclinations of Pitt's government provoked widespread Foxite and radical invocations of Stuart tyranny and the right of resistance.Footnote 170 Burke would have been justified in concluding that attempts to guard against the French threat by raising the ghost of the civil wars risked domesticating Jacobin philosophy and imparting to the “growing spirit of innovation” a spuriously Whiggish patina.Footnote 171

His caution was increasingly typical of many on the conservative wing of Burke's party. As Francis Jeffrey lamented in 1808, it was for some years “thought as well to say nothing in favor of Hampden, or Russel, or Sydney, for fear it might give spirits to Robespierre, Danton, or Marat.”Footnote 172 The revolution controversy clearly also involved, beyond its more immediate objects, a further recalibration of inherited attitudes to the 1640s and 1650s—a process with which Burke has often been closely identified. Indeed, if in many respects his legacy proved resistant to straightforward ideological appropriation, the anti-Puritanism of the Reflections has continued to suggest a degree of congruity with a renascent early nineteenth-century “Toryism,” an impression no doubt compounded by similar inclinations among his more prominent followers.Footnote 173 Such superficial affinities, it has been suggested here, only obscure the deep roots of Burke's counterrevolutionary rhetoric in the political contests of the previous decades. During the turbulent period stretching from the Wilkes affair to the Regency crisis, the first Stuart revolution acquired a range of controversial new interpretations and applications, in ways that placed growing pressure on the ideological identity of Burke's party and its more exclusive ancestral identification with the principles of 1688. The complex, ambivalent character of his response to that “revolution which happened in England about forty years before” may legitimately be regarded as a testament to the depth and sophistication of Burke's historical imagination. But it was also determined by the contingencies of partisan polemic and his long-standing sensitivity to the more localized and opportunistic uses of the nation's seventeenth-century past within the popular political discourse of a later revolutionary age.