1 Introduction

An experience that may be familiar to visitors of modern art museums is finding oneself before a sprawling arrangement of colour and shape seemingly randomly splattered on a canvas. One may look at such paintings for several moments, puzzled as to what meaning is purportedly captured in the colourful streaks. Eventually, feeling the anxiety of unknowing building inside of oneself, one’s eyes are almost instinctively drawn to the description card that is the permanent companion of many modern art paintings. Finally, as if searching for something tangible and specific to tackle cognitively, the description is read, and the museum goer is satisfied, perhaps even exasperatedly telling themselves “Ah I could see how that would be….”

Previous research on aesthetic preferences demonstrates that people have a general dislike of art that they consider meaningless (Reference DissanayakeDissanayake, 1988; Reference DonaldDonald, 1991; Reference HumphreyHumphrey, 1999; Reference Lewis-WilliamsLewis-Williams, 2002; Reference Ramachandran and HirsteinRamachandran & Hirstein, 1999). Those high in a personal need for structure especially dislike seemingly meaningless modern art (Reference Landau, Greenberg, Solomon, Pyszczynski and MartensLandau, Greenberg, Solomon, Pyszczynski & Martens, 2006). In contrast, openness to experience and a preference for non-conformity has been shown to be positively associated with a liking of modern art (Reference Feist and BradyFeist & Brady, 2004). Despite these individual differences, in general, people find a lack of meaning aversive. For example, when faced with meaninglessness or uncertainty, people go so far as endorsing illusory patterns and forming irrational beliefs in order to avoid this uncomfortable experience (Reference Van Harreveld, Rutjens, Schneider, Nohlen and KeskinisVan Harreveld, Rutjens, Schneider, Nohlen & Keskinis, 2014; Reference Whitson and GalinskyWhitson & Galinsky, 2008). Relatedly, external stimuli that help people make sense of art (e.g., titles) have been found to not only increase peoples’ perception of meaning for abstract modern art (Reference Russell and MilneRussell & Milne, 1997), but also their liking of difficult-to-interpret abstract art images (Reference Landau, Greenberg, Solomon, Pyszczynski and MartensLandau et al., 2006). Overall, it seems that the way people experience abstract art is inseparably tied to the ways in which they deal with meaning, lack of meaning, and their relative comfort with perceived meaninglessness.

1.1 Pseudo-Profound Bullshit

Related to peoples’ perception of meaning is a growing body of research demonstrating peoples’ frequent endorsements of meaningless computer-generated statements as profound (Reference Pennycook, Cheyne, Barr, Koehler and FugelsangPennycook, Cheyne, Barr, Koehler & Fugelsang, 2015). These statements (referred to as pseudo-profound bullshit) while superficially impressive, are generated by a computer program randomly arranging a set of profound-sounding words in a way that retains proper syntactic structure; as such they lack any intent to communicate something true or meaningful (see Dalton, 2016, for a comment, and Reference Pennycook, Cheyne, Barr, Koehler and FugelsangPennycook, Cheyne, Barr, Koehler & Fugelsang, 2016, for a response). Research examining peoples’ susceptibilities to pseudo-profound bullshit have utilized Frankfurt’s (2005) conception of bullshit as an absence of concern for truth or meaning. Thus, pseudo-profound bullshit is characterized not for its falsity but its fakery; bullshit may be true, false, or meaningless, what makes a claim bullshit is an implied yet artificial attention to truth and meaning.

While previous work has mostly focused on the characteristics of individuals who are susceptible to endorsing profundity in meaningless pseudo-profound statements (Reference Pennycook, Cheyne, Barr, Koehler and FugelsangPennycook et al., 2015; Reference Pennycook and RandPennycook & Rand, 2019; Reference Walker, Turpin, Stolz, Fugelsang and KoehlerWalker, Turpin, Stolz, Fugelsang & Koehler, 2019), of potentially greater consequence is how people deploy bullshit to gain social advantages. That is, research dealing with the idiosyncratic tendency to find meaning in randomly generated stimuli, while interesting, largely overlooks the real-world domains in which peoples’ susceptibilities to pseudo-profound bullshit may be exploited to gain prestige, status, and material goods. An aim of the current work is to propose a new theoretical framework which views bullshitting as a low-cost strategy for gaining an advantage in prestige-awarding domains.

1.2 Bullshit as a Low-Cost Strategy

For many domains in which humans compete for prestige, status, or material goods, the criteria for determining who succeeds and fails at least partially rely on impressing others. In these domains, bullshit may be deployed as a low-cost strategy for gaining prestige. An agent working towards being successful in a domain, can engage in the long and arduous process of acquiring expert skills and knowledge that they could then leverage to accomplish certain goals. Alternatively, an agent could engage in a less effortful process that produces similar benefits (i.e., impressing others with bullshit). These two strategies need not be mutually exclusive. A person with impressive skills and competence could potentially use bullshit to enhance their outcomes, and as such, yield more success compared to equally skilled peers who are either unwilling or unable to bullshit well.

The extent to which bullshit can be deployed as an effective low-cost strategy for success may greatly vary by domain. First, bullshit is less likely to be effective in domains in which success is objectively judged, and thus, impressing others is not required. For example, in athletic competitions focused on speed (e.g., 100m race), endurance (e.g., a marathon), or strength (e.g., powerlifting), the ability to impress others with bullshit should be a) difficult and b) of little value, as one’s degree of competence in these competitions can be easily and objectively measured. Nevertheless, in many domains, success can be obtained, or at least enhanced, by impressing others. For example, in artistic endeavors such as music, poetry, or art, technical skills are unlikely to be the sole determiner of success. What is likely to be equally important is the ability to impress others by making one’s artwork appear unique, profound, and meaningful (Reference MillerMiller, 2001). A quick and efficient way to impress others in this manner is with claims that imply, yet do not contain, any specifically interpretable truth or meaning (i.e., with bullshit). Of course, “bullshit” in this context need not carry any negative connotation. If the goal of a piece of art is to inspire the feeling of profoundness in its viewers, whether this feeling originates from the art itself or is created by the viewer is of no consequence. Such situations may be contrasted with circumstances in which truth, rather than pleasure or profoundness, is a primary goal (e.g., science or medicine), where the use of bullshit to gain advantages is antithetical to the primary purpose of the discipline.

1.3 “Bullshit” in Science

While we may wish to believe that bullshit is ineffective in more objectively judged domains (e.g., science), where truth is of primary importance, a growing body of research hints that even here bullshitting may offer a competitive advantage. For example, Eriksson (2012) demonstrated that the inclusion of irrelevant (and nonsensical in context) math formulae in the abstracts of scientific papers caused graduate-degree holders in education, the humanities, and other non-mathematics fields to rate these scientific papers as higher in quality. Similarly, Reference Weisberg, Keil, Goodstein, Rawson and GrayWeisberg, Keil, Goodstein, Rawson, and Gray (2008) found that including irrelevant neuroscience explanations for psychological phenomena caused readers to judge these explanations as more satisfying compared to when the same explanation was given without irrelevant neuroscience information. Notably, this difference was especially pronounced when an initial explanation was of poor quality. In both instances, these empirical findings highlight how the inclusion of seemingly impressive language that was irrelevant to the truth-value of a scientific claim improved readers’ reception of the work. While it can be debated whether these two instances qualify as “bullshit” technically, these cases do highlight how the goal of scientific communication can become less about strictly communicating true knowledge about the universe and more about impressing an audience.

The extent to which a domain attends to and effectively polices the fakery characteristic of bullshit is likely to determine how successfully bullshit can be utilized as a low-cost strategy for achieving success. Consistent with this notion, research on the antecedents of bullshitting has demonstrated that people bullshit more (i.e., make claims less concerned with the truth) when they believe they are communicating with an unknowledgeable person, a like-minded individual, or believe they will not have to justify their claims (Reference PetrocelliPetrocelli, 2018). Thus, people appear to bullshit more when they feel it will either go unnoticed or be tolerated. In such cases, bullshit may not only be prevalent, but effective.

1.4 Bullshit Makes the Art Grow Profounder

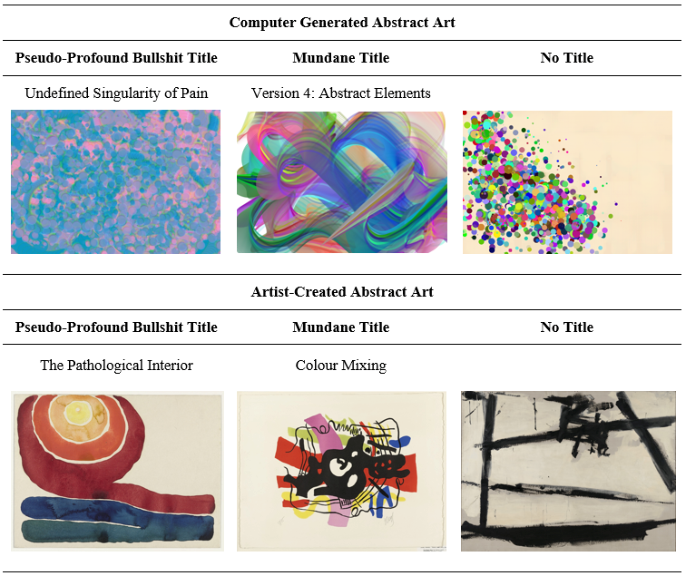

Some abstract artists have embraced a radically subjective view toward art, that is to say there is no possible objective standard for beauty or meaning. These artists maintain a goal to impress a sense of depth or beauty, while going further than merely not being concerned about truth, but instead denying that any objective truth could possibly exist (for discussion of these views of art see: Crowley, 1958; Reference YoungYoung, 1997; similar views have been expressed regarding pseudo-profound bullshit: Dalton, 2016). With the popular view that all experiences of meaning in art are self-generated, and all experiences are equally valid, the domain of abstract art may perfectly exemplify an environment for which bullshit is likely to be rampant and effective. That is, not only is it possible that bullshit enhances the perceived quality of abstract art, but the mutually agreed upon notion among some abstract artists and enthusiasts that no objective truth exists, may serve to disarm anyone who might otherwise be skeptical of the meaning attached to an art piece. In the current study, we test whether the presence of a pseudo-profound bullshit title, consisting of a random arrangement of words commonly used to describe art, can influence peoples’ perceptions of the profoundness of abstract art. We hypothesize that abstract art accompanied by pseudo-profound bullshit titles (e.g., Evolving Model of Dreams) will be judged as more profound compared to abstract art that is untitled (Study 1) or is accompanied by a mundane title (e.g., Objects in Tint; Studies 2 and 3; see Figure 1). The current study tests these hypotheses using computer-generated (Studies 1 and 2) and artist-created abstract art (Study 3).

Figure 1: Example of computer-generated and artist-created abstract art presented to participants in the current study. All abstract art was presented with either a pseudo-profound bullshit, mundane, or no title.

If the world of abstract art does in fact represent an ideal environment for bullshit to be deployed as an effective low-cost strategy for gaining prestige, then one would expect the presence of bullshit to be widespread in this domain. It is a common casual observation that artists, and especially abstract or modern artists, have their own specific and unique way of communicating about art. This is reflected in the choice of titles, descriptions, and modes of speaking that collectively fall under the umbrella of “International Art English” (Reference Rule and LevineRule & Levine 2012). Some of the key linguistic features of International Art English, as described by Rule and Levine, include the morphing of verbs and adjectives into nouns (e.g., potential to potentiality), the pairing of like terms (e.g., internal psychology and external reality), and the favouring of hard-to-picture spatial metaphors (e.g., culmination of many small acts achieves mythic proportions) over clear and concise language. Now consider an example of pseudo-profound bullshit: “the future will be an astral unveiling of inseparability,” and compare it to the characteristics of International Art English. There is a noticeable similarity, such that they both include the morphing of adjectives into nouns (i.e., inseparable to inseparability) and capture the use of impossible-to-picture visual metaphors as the main vehicle in impressing a sense of depth. In this way, both modes manage to be stylistically impressive while not communicating anything specific that could be challenged. Linguistically, it seems that the English artists use to describe and discuss their practice is either the same, or is at least tapping into the same cognitive mechanisms that give pseudo-profound bullshit its effect. That is to say, that the linguistic features that elevate the perceived profoundness of pseudo-profound bullshit above a mundanely stated truth are also present in International Art English, and this may allow for the use of bullshit to transfer a “false” sense of profoundness onto an abstract art piece.

It could be the case that artists have independently stumbled upon the competitively advantageous potential that good bullshitting affords in a prestige-awarding domain. These predictions are not intended to be taken as a value judgment on the quality of modern art, nor a dismissal of the subjectively derived meaning formed when exposed to such pieces. If anything, the production of good and satisfying “bullshit” (i.e., statements meant to be impressive regardless of truth) may simply be part of the artistic process as much as the production of a painting. The prediction that follows from this is that there should be a strong association between peoples’ receptiveness to pseudo-profound bullshit and their endorsement of profoundness in International Art English (Study 4).

2 Study 1

Study 1 explores whether computer-generated pseudo-profound bullshit can be used to increase the profundity of computer-generated abstract art. Specifically, we hypothesize that abstract art accompanied by a pseudo-profound bullshit title will be judged as more profound compared to untitled abstract art images.

2.1 Method

2.1.1 Participants

A sample of 200 University of Waterloo undergraduates volunteered to complete Study 1 in exchange for course credit.

2.1.2 Measures

A full list of items for all measures and materials used in the current study can be found in our supplementary materials (Part A).

Bullshit Receptivity Scale

The Bullshit Receptivity (BSR) scale, taken from Pennycook and colleagues (2015), was administered in Study 1. This scale consists of thirty pseudo-profound bullshit statements originally retrieved from two websites (http://wisdomofchopra.com and http://sebpearce.com/bullshit/), both of which create meaningless statements by randomly arranging a list of profound-sounding words in a way that preserves syntactic structure (e.g., “Wholeness quiets infinite phenomena”). These statements, while perhaps superficially impressive, are not specifically interpretable. That is, due to their method of generation, they do not have a specific intended meaning. Participants rated the profundity of each pseudo-profound bullshit statement on a 5-point scale which ranged from 1 (Not at all profound) to 5 (Very profound). A bullshit receptivity score was calculated for each participant by averaging the profundity ratings provided to each of the thirty pseudo-profound bullshit statements.

Motivational Quotation Scale

To contrast the meaningless pseudo-profound statements featured in the BSR, we included ten motivational quotations, also originating from Pennycook and colleagues (2015). These statements were designed to capture a true attempt at communicating something meaningful and profound (e.g., “A wet man does not fear the rain”). Participants rated the profundity of each motivational statement using the same 5-point scale as the BSR. Similarly, participants’ profundity ratings to all ten motivational quotations were averaged to create a motivational quotation scale score for each participant.

Mundane Statements

Ten mundane statements were included in Study 1 (Reference Pennycook, Cheyne, Barr, Koehler and FugelsangPennycook et al., 2015). These statements, while technically true and specifically interpretable, did not contain truth of a grand or profound nature (e.g., “Newborn babies require constant attention”). Once again, participants rated each of these ten mundane statements using the same 5-point scale as the BSR and motivational quotations. A profundity score for mundane statements was calculated for each participant by averaging the profundity ratings provided to mundane statements.

Bullshit Sensitivity

As done previously by Pennycook and colleagues (2015), we calculate bullshit sensitivity as a measure of a participant’s ability to distinguish pseudo-profound bullshit statements from meaningfully profound motivational quotations. Bullshit sensitivity was computed by subtracting participants’ mean profundity ratings given to pseudo-profound bullshit statements from their mean profundity ratings given to motivational quotations. Higher scores indicate greater sensitivity in detecting bullshit.

2.1.3 Materials

Pseudo-Profound Bullshit Title Generation

Approximating computer-generated pseudo-profound bullshit, we gathered 150 randomly-generated titles using a website (http://noemata.net/pa/titlegen/) which strings together words commonly used in art titles and descriptions. As these titles were generated via a computer program randomly arranging words commonly used to describe art, and therefore lacked any intent to communicate something meaningful, we categorized these randomly-generated titles as bullshit. We removed eight pseudo-profound bullshit titles due to the fact that they referenced specific features (e.g., “Crying Boy in a Corner”). This left us with 142 randomly-generated titles which were included in Study 1.

Abstract Art Image Generation

Abstract art images were generated by a research assistant blind to the studies’ purpose and hypotheses. Images were generated using two websites (http://bomomo.com and http://windowseat.ca/viscosity/create.php), which provided drawing tools that behave in a pseudo-random fashion, only affording the user coarse-grained control over an image’s content (i.e., colour, broad shapes, and pattern types). As such, these websites allowed us to produce 200 pseudo-randomly generated abstract art images which lacked any human-defined intention to communicate meaning. In order to match the number of pseudo-profound bullshit titles, we eliminated 58 abstract art images by randomly sampling 142 out of our 200 images using the random sampling functions provided in the NumPy library for Python (Reference Walt, Colbert and VaroquauxWalt, Colbert & Varoquaux, 2011).

2.1.4 Procedure

Study 1 utilized a within-subjects design in which participants were presented with 142 computer-generated abstract art images in PsychoPy (Reference PeircePeirce, 2007) in a random order, half of which were accompanied by a randomly-generated pseudo-profound bullshit title and half of which were left untitled. For each trial, there was a 50% chance of the presented image being accompanied by a pseudo-profound bullshit title. Following the presentation of each abstract art image, participants were asked to rate the profundity of the image using a 5-point scale which ranged from 1 (Not at all profound) to 5 (Very profound). Consistent with past work (Reference Pennycook, Cheyne, Barr, Koehler and FugelsangPennycook et al., 2015), participants were instructed that the definition of profound was to be taken as “of deep meaning; of great and broadly inclusive significance” prior to the start of the study. Following the evaluation of all 142 art images, participants judged the profundity of each of the 142 pseudo-profound bullshit titles unaccompanied by an art image. Next, participants were asked to rate the profundity of fifty statements (i.e., BSR, motivational quotations, and mundane statements) that were presented in a randomized order. Lastly, to conclude the study, participants completed the Cognitive Reflection Test (CRT), Actively Open-Minded Thinking scale (AOT), and Wordsum task. These individual difference measures were collected for exploratory reasons and thus are reported in the supplementary materials (Part C).

2.2 Results and Discussion

A paired samples t-test comparing participants’ profundity ratings of abstract art when accompanied by a randomly generated pseudo-profound bullshit title versus no title revealed a significant effect of title presence, t(199) = 10.16, p < .001, d = 0.43. That is, as predicted, abstract art images presented with pseudo-profound bullshit titles (M = 2.60, SD = 0.69) were perceived as more profound compared to untitled abstract art (M = 2.31, SD = 0.66), demonstrating the ability of pseudo-profound bullshit to enhance the profundity of abstract art.Footnote 1 To take into account item-level variance, a paired samples t-test was also conducted comparing the same artworks with and without a title (t(141) = 19.15, p < .001), demonstrating that the effect was observed at the item as well as the participant level.

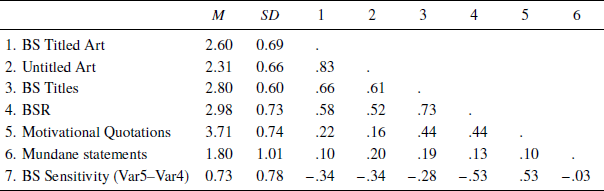

Along with the observed profundity enhancing effect of pseudo-profound bullshit titles, we conducted correlational analyses to explore the relation between some of our key variables (see Table 1). First, a strong positive correlation was found between profundity ratings for pseudo-profound bullshit statements (i.e., bullshit receptivity) and randomly-generated pseudo-profound bullshit titles [r(198) = .73, p < .001], suggesting that our randomly-generated titles were a good approximation of pseudo-profound bullshit. Furthermore, we observed strong positive correlations between participants’ bullshit receptivity and their profoundness ratings given to titled [r(198) = .58, p < .001] and untitled [r(198) = .52, p < .001] abstract art. Similarly, we find that participants’ bullshit sensitivity was negatively correlated with their profoundness ratings given to titled [r(198) = −.34, p < .001] and untitled [r(198) = −.34, p < .001] abstract art, indicating that participants failing to distinguish between pseudo-profound bullshit and motivational quotations were more likely to judge computer-generated abstract art as profound.

Table 1: Study 1 Correlations

Note. Pearson correlations (Study 1; N = 200). “BS Titled Art” refers to participants’ profundity ratings given to abstract art images accompanied by a pseudo-profound bullshit title. “Untitled Art” refers to participants’ profundity ratings given to untitled abstract art images. “BS Titles” refers to participants’ profoundness ratings of pseudo-profound bullshit titles unaccompanied by art. BSR = Bullshit Receptivity scale; BS Sensitivity = Participants’ mean motivational quotation profundity ratings minus their mean BSR profundity ratings. Coefficients of .14 or greater are significant at the p < .05 level, coefficients of .19 or greater are significant at the p < .01, coefficients of .24 or greater are significant at the p < .001 level.

3 Study 2

The results of Study 1 suggest that the addition of pseudo-profound bullshit titles to abstract art images increases the profundity of abstract art. Nevertheless, the possibility remains that the profundity enhancing effect of our pseudo-profound bullshit titles may have simply been a result of participants using any cue to inform their ratings. For example, it is plausible that giving abstract art any title at all signals that it was produced effortfully, and thus may increase its perceived profundity. If this is the case, then the observed profundity enhancing effect of our pseudo-profound bullshit titles would not be an effect of bullshit at all. To test this possibility, Study 2 introduced mundane titles into the title set. If simply providing any title to an abstract art image enhances the perceived profundity of that image, we should expect that both pseudo-profound bullshit and mundane titles will increase the profundity of abstract art. However, if this effect is unique to bullshit, then we should expect that only art paired with pseudo-profound bullshit will be perceived as more profound compared to untitled art. We therefore hypothesized that abstract art accompanied by a pseudo-profound bullshit title would be judged as more profound compared to art accompanied by a mundane title, or no title.

3.1 Method

3.1.1 Participants

A sample of 218 University of Waterloo undergraduates volunteered to complete a study in exchange for course credit.

3.1.2 Measures and Materials

All measures were identical to those used in Study 1 with the exception that in Study 2 the AOT and CRT were no longer administered. Similarly, all materials were identical to those used in Study 1 with the exception of the introduction of mundane titles.

Mundane Titles

One-hundred fifty mundane titles were generated by a research assistant blind to both the purpose and hypotheses of Study 2. These titles were generated by combining various descriptive words commonly used in art contexts. All mundane titles were created such that they pertained to the physical properties of art as opposed to the meaning of an art piece (e.g., shape, colour, arrangement). Using a random sampling procedure, we selected 71 mundane titles to be used in this study. This ensured that half of the titles used in Study 2 were mundane titles, with the other half being pseudo-profound bullshit titles.

3.1.3 Procedure

Study 2 utilized the same general procedure as Study 1, with the primary exception being the introduction of mundane titles during participants’ profundity judgments of computer-generated abstract art images. Specifically, participants were presented with 142 images in a random order, with each image having an equal likelihood of being accompanied by a randomly-generated bullshit title, a mundane title, or no title. Following participants’ profundity judgements of all 142 abstract art images, participants were asked to rate the profundity of all 142 titles (71 pseudo-profound bullshit titles and 71 mundane titles). Other than these noted changes the procedure of Study 2 followed that of Study 1.

3.2 Results and Discussion

A repeated measures ANOVA revealed a main effect of title type (pseudo-profound bullshit title, mundane title, untitled) on profundity ratings of abstract art images F(2, 434) = 81.63, p < .001, ![]() = .273. Follow-up paired samples t-tests revealed significant differences between profoundness ratings for pseudo-profound bullshit titled abstract art and untitled [t(217) = 9.96, p < .001, d = 0.55] and mundane titled [t(217) = 9.92, p < .001, d = 0.50] abstract art images. No difference was detected between profundity ratings given to mundane titled and untitled art [t(217) = 1.24, p = .22, d = 0.05]. Collectively, these results suggest that it is pseudo-profound bullshit titles specifically that enhance the profundity of abstract art, as opposed to any and all titles. Specifically, the addition of mundane titles to abstract art images did not enhance the profundity of these images compared to untitled art. To take into account item-level variance, paired samples t-tests were also conducted comparing the same artworks across title types. A significant difference was detected between pseudo-profound bullshit titled and untitled art: t(141) = 21.33, p < .001, pseudo-profound bullshit titled and mundane titled art: t(141) = 19.41, p < .001, as well as between untitled and mundane titled art: t(141) = 1.99, p = .049. Therefore, the effect of title type on profundity ratings of art was observed at the item as well as the participant level.

= .273. Follow-up paired samples t-tests revealed significant differences between profoundness ratings for pseudo-profound bullshit titled abstract art and untitled [t(217) = 9.96, p < .001, d = 0.55] and mundane titled [t(217) = 9.92, p < .001, d = 0.50] abstract art images. No difference was detected between profundity ratings given to mundane titled and untitled art [t(217) = 1.24, p = .22, d = 0.05]. Collectively, these results suggest that it is pseudo-profound bullshit titles specifically that enhance the profundity of abstract art, as opposed to any and all titles. Specifically, the addition of mundane titles to abstract art images did not enhance the profundity of these images compared to untitled art. To take into account item-level variance, paired samples t-tests were also conducted comparing the same artworks across title types. A significant difference was detected between pseudo-profound bullshit titled and untitled art: t(141) = 21.33, p < .001, pseudo-profound bullshit titled and mundane titled art: t(141) = 19.41, p < .001, as well as between untitled and mundane titled art: t(141) = 1.99, p = .049. Therefore, the effect of title type on profundity ratings of art was observed at the item as well as the participant level.

The results of correlational analyses examining the associations between various key variables can be viewed in Table 2. Consistent with the results of Study 1, we observed a strong positive association between participants’ bullshit receptivity and their profundity judgments of abstract art images across all title types [BS Title: r(216) = .52, p < .001; Mundane Title: r(216) = .45, p < .001; No Title: r(216) = .44, p < .001]. Similarly, we also find that participants’ bullshit sensitivity was negatively correlated with their profoundness judgments of abstract art images [BS Title: r(216) = −.23, p = .001; Mundane Title: r(216) = −.22, p = .001; No Title: r(216) = −.28, p < .001], once again demonstrating that participants failing to distinguish between pseudo-profound bullshit and motivational quotations were more likely to judge abstract art as profound. Taken together, these associations provide further evidence that those finding meaning in pseudo-profound bullshit statements are more likely to perceive profoundness in abstract art.

Table 2: Study 2 Correlations

Note. Pearson correlations (Study 2; N = 218). “BS Titled Art” refers to participants’ profundity ratings given to abstract art images accompanied by a pseudo-profound bullshit title. “Mundane Titled Art” refers to participants’ profundity ratings given to abstract art images accompanied by mundane titles. “Untitled Art” refers to participants’ profundity ratings given to untitled abstract art images. “BS Titles” refers to participants’ profoundness ratings of pseudo-profound bullshit titles unaccompanied by art. “Mundane Titles” refers to participants’ profoundness ratings of mundane titles unaccompanied by art. BSR = Bullshit Receptivity scale. BS Sensitivity = Participants’ mean motivational quotation profundity ratings minus their mean BSR profundity ratings. Coefficients of .14 or greater are significant at the p < .05 level, coefficients of .19 or greater are significant at the p < .01, coefficients of .24 or greater are significant at the p < .001 level.

4 Study 3

While the results of our previous studies suggest that pseudo-profound bullshit can enhance the perception of profoundness in abstract art, a limitation of these studies is that all abstract art images were computer-generated. Therefore, one may wonder whether pairing pseudo-profound bullshit titles with artist-created art, which may be of higher quality compared to our computer-generated images, would have the same profundity enhancing effect. In Study 3 we assess this possibility by including artist-created abstract art images. We hypothesize that for both artist-created and computer-generated abstract art, participants would judge art accompanied by a pseudo-profound bullshit title as more profound compared to art accompanied by a mundane title, or no title. Crucially, we predict no interaction. That is, we expect the effect of pseudo-profound bullshit titles to be the same among both artist-created and computer-generated art.

4.1 Method

4.1.1 Participants

A sample of 200 University of Waterloo undergraduates volunteered to complete a study in exchange for course credit.

4.1.2 Measures and Materials

The measures administered in Study 3 were identical to those administered in Study 2. Similarly, all materials used in Study 3 were identical to those used in Study 2, with the only difference being the addition of artist-created abstract art.

Artist-Created Abstract Art

In order to investigate the influence of randomly-generated bullshit titles on real artist-created art, we gathered 80 artist-created abstract art images from the Museum of Modern Art’s website (https://www.moma.org). All 80 images were collected by a research assistant blind to both the purpose and hypotheses of Study 3. We eliminated nine of these abstract art images from Study 3 due to their likeness to concrete forms (e.g., humans, animals, and household objects). This left us with 71 artist-created abstract art images which were included in Study 3.

4.1.3 Procedure

As in Studies 1 and 2, participants were presented with 142 abstract art images and asked to judge the profundity of each image. In Study 3, the set of 142 abstract art images consisted of 71 computer-generated images (randomly selected from our set of 142 computer-generated images used in Studies 1 and 2) and 71 real-world artist-created images. Each image had an equal chance of being accompanied by a pseudo-profound bullshit title, a mundane title, or no title. The remaining procedure was identical to that of Study 2, with participants judging the profundity of all 142 titles unaccompanied by an abstract art image. Additionally, participants provided profundity ratings for 50 statements consisting of pseudo-profound bullshit statements, motivational quotations, and mundane statements (mixed in a random order), and completed the Wordsum verbal ability task.

4.2 Results and Discussion

A 3 (title type: pseudo-profound bullshit title, mundane title, untitled) X 2 (art type: computer-generated, artist-created) repeated measures factorial ANOVA revealed a main effect of title type on profundity ratings of abstract art images, F(2, 398) = 67.00, p <.001, ![]() = .252. Furthermore, a main effect of art type was also observed, F(1, 199) = 238.69, p <.001,

= .252. Furthermore, a main effect of art type was also observed, F(1, 199) = 238.69, p <.001, ![]() = .545, indicating that artist-created art was judged to be more profound compared to computer-generated art. Notably, no interaction was detected, F(2, 398) = 2.13, p = .12,

= .545, indicating that artist-created art was judged to be more profound compared to computer-generated art. Notably, no interaction was detected, F(2, 398) = 2.13, p = .12, ![]() = .011, suggesting that the effect of title type did not differ between computer-generated and artist-created art. Thus, whether art was computer-generated or artist-created, accompanying the art image with a pseudo-profound bullshit title enhanced the perceived profoundness of the art image all the same compared to when the art image was accompanied by a mundane title or no title.

= .011, suggesting that the effect of title type did not differ between computer-generated and artist-created art. Thus, whether art was computer-generated or artist-created, accompanying the art image with a pseudo-profound bullshit title enhanced the perceived profoundness of the art image all the same compared to when the art image was accompanied by a mundane title or no title.

Follow-up paired samples t-test examining the main effect of title type revealed significant differences between profundity ratings given to pseudo-profound bullshit titled and mundane titled computer-generated art [t(199) = 8.74, p < .001], as well as between pseudo-profound bullshit titled and untitled computer-generated art [t(199) = 8.17, p < .001]. No significant differences were observed between profundity ratings given to computer-generated mundane titled and untitled art [t(199) = 0.25, p = .802]. Importantly, examining the effect of title type for artist-created art produced an identical pattern of results, with pseudo-profound bullshit titled art being judged as more profound compared to both mundane titled art [t(199) = 8.26, p < .001], and untitled art [t(199) = 6.67, p < .001], and mundane titled and untitled art being judged as similarly profound [t(199) = 1.88, p = .061]. Therefore, the results of Study 3 demonstrate how pseudo-profound bullshit can be utilized to enhance the profundity of both computer-generated and artist-created abstract art images. Additionally, this profundity enhancing effect appears to be unique to pseudo-profound bullshit as including mundane titles to either computer-generated or artist-created abstract art did not result in an increase in participants’ perceptions of profundity for these art images.

To take into account item-level variance, paired samples t-tests were also conducted comparing the same artworks across title types for both computer and artist-generated art. For computer-generated art, a significant difference was detected between pseudo-profound bullshit titled and untitled art: t(70) = 10.83, p < .001, as well as between pseudo-profound bullshit titled and mundane titled art: t(70) = 10.63, p < .001. Consistent with participant-level results, no significant difference was detected between untitled and mundane titled art: t(70) < .001, p > .999. For artist-created art, a significant difference was detected between pseudo-profound bullshit titled and untitled art: t(70) = 10.70, p < .001, as well as between pseudo-profound bullshit titled and mundane titled art: t(70) = 12.15, p < .001. Consistent with participant-level results, no significant difference was detected between untitled and mundane titled art: t(70) = 1.83, p = .071. In sum, for both art types the effect of bullshit titles on profundity ratings of art was observed at the item as well as the participant level.

Finally, we report the results of a set of correlational analyses exploring the relation between several key variables of interest (see Table 3). Most notably, we once again observe a positive relation between participants’ profundity ratings of pseudo-profound bullshit statements (i.e., bullshit receptivity) and computer-generated [BS Title: r(198) = .46, p < .001; Mundane Title: r(198) = .39, p < .001; No Title: r(198) = .34, p < .001] and artist-created abstract art across all title types [BS Title: r(198) = .45, p < .001; Mundane Title: r(198) = .41, p < .001; No Title: r(198) = .34, p < .001]. Similarly, we observe negative relations between bullshit sensitivity and profundity ratings of computer-generated [BS Title: r(198) = −.27, p < .001; Mundane Title: r(198) = −.23, p = .001; No Title: r(198) = −.20, p = .005] and artist-created abstract art [BS Title: r(198) = −.18, p = .009; Mundane Title: r(198) = −.20, p = .004] across all title types, with the exception of untitled artist-created abstract art [No Title: r(198) = −.10, p = .149]. On the whole, these associations once again demonstrate that participants who fail to distinguish between pseudo-profound bullshit and motivational quotations are more likely to judge both computer-generated and artist-created abstract art as profound.

Table 3: Study 3 Correlations

Note. Pearson correlations (Study 3; N = 200). AC = Artist-Created. CG = Computer-Generated. “BS Titled Art” refers to participants’ profundity ratings given to abstract art images accompanied by a pseudo-profound bullshit title. “Mundane Titled Art” refers to participants’ profundity ratings given to abstract art images accompanied by mundane titles. “Untitled Art” refers to participants’ profundity ratings given to untitled abstract art images. “BS Titles” refers to participants’ profoundness ratings of pseudo-profound bullshit titles unaccompanied by art. “Mundane Titles” refers to participants’ profoundness ratings of mundane titles unaccompanied by art. BSR = Bullshit Receptivity scale. BS Sensitivity = Participants’ mean motivational quotation profundity ratings minus their mean BSR profundity ratings. Coefficients of .14 or greater are significant at the p < .05 level, coefficients of .19 or greater are significant at the p < .01, coefficients of .24 or greater are significant at the p < .001 level.

5 Study 4

Studies 1 through 3 demonstrate the enhancing effect of pseudo-profound bullshit on abstract art. However, the types of bullshit used in these studies have been generated by computers. So, although we have demonstrated that pseudo-profound bullshit can be employed successfully to enhance the perceived profundity of abstract art in a lab context, it remains to be demonstrated that the type of language actually used by artists is perceived to be distinguishable from bullshit. While both International Art English and pseudo-profound bullshit appear to share various surface features (e.g., the morphing of adjectives into nouns), the degree to which people process both modes of communication similarly has yet to be investigated. In Study 4 we assess the similarity between International Art English and pseudo-profound bullshit by having participants judge the profundity of a variety of International Art English and pseudo-profound bullshit statements. We hypothesize that profundity ratings for pseudo-profound bullshit and International Art English will be strongly associated.

5.1 Method

5.1.1 Participants

A sample of 200 University of Waterloo undergraduates volunteered to complete a study in exchange for course credit.

5.1.2 Measures and Materials

Study 4 no longer included computer-generated or artist-created art. Instead, participants judged the profundity of the same pseudo-profound bullshit, motivational quotations, and mundane statements used in Studies 1-3. Furthermore, Study 4 included the addition of 30 real-world International Art English statements and 7 CRT items.

International Art English

International Art English (IAE) refers to a language used by many artists and artistic scholars to discuss art (Reference Rule and LevineRule & Levine, 2012). Its key features include converting verbs and adjectives into nouns (e.g., potential to potentiality), the pairing of like terms (e.g., internal psychology and external reality), and hard-to-picture spatial metaphors (e.g., culmination of many small acts achieves mythic proportions). For the purpose of this study, we had a hypothesis-blind research assistant gather 30 statements from various sources (e.g., art exhibition descriptions, essays by art historians, etc.) that adhered to at least one of the key features of IAE. Participants rated the profundity of each IAE statement on a 5-point scale which ranged from 1 (Not at all profound) to 5 (Very profound). For each participant, an IAE profundity score detailing how profound an individual found IAE statements was calculated by averaging the profundity ratings provided to each statement.

5.1.3 Procedure

Participants primary task in Study 4 was to judge the profundity of 80 statements (presented in a random order) consisting of 30 pseudo-profound bullshit statements, 10 motivational quotations, 10 mundane statements, and 30 IAE statements. Participants judged each statement using the same 5-point scale described above. Following the profundity judgment task, participants completed the Wordsum and CRT (see supplementary materials to conclude Study 4.

5.2 Results and Discussion

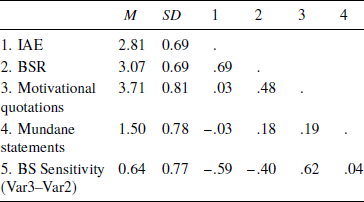

The results of Study 4 can be viewed in Table 4. As predicted, profundity ratings given to International Art English and pseudo-profound bullshit statements shared a strong positive association, r(198) = .69, p < .001, suggesting that International Art English and pseudo-profound bullshit were perceived similarly by participants. In contrast, it was observed that profundity ratings for International Art English were not associated with profundity ratings for either motivational [r(198) = .03, p = .672] or mundane statements [r(198) = −.03, p = .651]. Providing further support for the pseudo-profound bullshit and International Art English overlap, International Art English profundity judgments were strongly correlated with bullshit sensitivity [r(198) = −.59, p < .001], indicating that people who failed to distinguish between pseudo-profound bullshit and motivational quotations were especially likely to endorse International Art English as profound.

Table 4: Study 4 Correlations

Note. Pearson correlations (Study 4; N = 200). BSR = Bullshit Receptivity scale; IAE = International Art English; BS Sensitivity = Participants’ mean motivational quotation profundity ratings minus their mean BSR profundity ratings. Coefficients of .14 or greater are significant at the p < .05 level, coefficients of .19 or greater are significant at the p < .01, coefficients of .24 or greater are significant at the p < .001 level.

6 General Discussion

The current study demonstrates the potential for pseudo-profound bullshit to enhance the perceived profundity of abstract art. Specifically, over the course of three studies, we find that simply including a randomly-generated pseudo-profound bullshit title alongside an abstract art image increases the perceived profundity of the art image. Furthermore, we show that it is pseudo-profound bullshit titles specifically that enhance the profundity of abstract art, as opposed to any and all titles. Additionally, we demonstrate that bullshit titles produce the same profundity enhancing effect for both computer-generated and artist-created abstract art. Finally, in Study 4 we demonstrate that pseudo-profound bullshit and International Art English are perceived to be similar (or the same) rhetorical phenomena by our participants.

6.1 Bullshit as a Low-Cost Strategy: Art and Beyond

In most domains success is determined, at least partially, based on the ability to impress others. In any instance where humans are making decisions about the quality of output of others there is room for subjective impressions to influence outcomes. As a highly social species, it may be the case that instances where performance is entirely objective are rarer than those influenced by the subjective opinions of others. We theorize that bullshit can be used effectively as a low-cost strategy to impress others and gain prestige in every domain except where performance is clearly and strictly objective. Maximizing one’s skills and competence in a domain is typically a long and arduous process. However, being able to produce satisfying bullshit that can impress others by presenting one’s self and one’s work as impressive and meaningful may allow an individual to obtain success in a way that requires much less time and effort. The results of the current study exemplify these claims, as we demonstrate how attaching randomly-generated pseudo-profound bullshit titles to abstract art images improves the perceived profundity of these images. Critically, this is true even though images and titles were paired completely randomly with no effort expended in matching the title to the artistic content. Thus, we demonstrate how pseudo-profound bullshit can be employed in the domain of abstract art to effortlessly and expediently increase the profundity of an individual’s art.

Previous work has demonstrated that people bullshit more (i.e., make claims less concerned with the truth) when they believe they will not have to justify their claims (Reference PetrocelliPetrocelli, 2018). To the extent that some abstract artists embrace the radically subjective view that there is no objective standard for beauty or meaning, the domain of abstract art may be especially likely to be permissive of bullshit. That is, the agreed upon notion that no objective beauty exists and that all experiences are equally valid may serve to protect the individual using bullshit from skeptical claims. Therefore, paired with the fact that the domain of abstract art heavily rewards impressing others, as opposed to objective demonstrations of technical skill, bullshit may not only be effective in this domain (as demonstrated) but also tolerated. On this basis, one may expect the presence of bullshit to be widespread in the abstract art world. In Study 4, we provide some evidence for this claim, as we find that International Art English, above sharing various surface features with meaningless pseudo-profound bullshit, is judged indistinguishably from pseudo-profound bullshit by our participants. Thus, it may be the case that artists have independently stumbled upon the potential for bullshit to increase the profundity of abstract art.

Although here we demonstrate that bullshit may be deployed to enhance the perceived profoundness of abstract art, of greater theoretical interest is the possibility for good bullshitting to afford a competitive advantage in many domains of human production. Any system where individuals are rewarded some level of prestige, attention, or social status for impressing others offers a chance for energetically less expensive strategies to be employed as competitive short cuts. Bullshit, with its emphasis on impressiveness as opposed to meaningfulness and truth, may assist individuals in impressing others, and consequently, in successfully navigating various social systems. This is likely to be especially true for social systems which do not place a high value on detecting and punishing the fakery characteristic of bullshit, as in such cases the potential rewards of bullshitting may far outweigh the potential costs. For example, bullshit may be especially effective as a low-cost strategy for gaining prestige in social systems in which prestige is rewarded by unknowledgeable or like-minded individuals, as such individuals may be less likely to detect and punish the use of bullshit. Overall, the extent to which bullshit can be effectively deployed by individuals looking to gain social advantages is an interesting question for which the current study begins to address.

6.2 Limitations and Future Directions

One limitation of the current study is that it exclusively tests the influence of pseudo-profound bullshit titles in the domain of abstract art. However, the theoretical account that we propose here leads us to predict that bullshit can be applied in a wide-variety domains in which competence is not objectively judged using strict and specific criteria, success is determined by impressing others, and the fakery characteristic of bullshit is not strictly monitored and punished. For example, our proposed account predicts that attaching pseudo-profound bullshit titles to representational art would also increase the profundity of such art images, albeit to a lesser degree, as representational art lends itself to more objective assessments of quality and meaning (e.g., the accuracy of portrayal) compared to abstract art which welcomes more subjective interpretations. Future studies should be undertaken to investigate the domains in which bullshit may be deployed to gain a competitive advantage.

Second, another limitation of the current study is that participants were exclusively judging various artworks for their profoundness. There are many other dimensions on which people can form an impression of a piece of art (e.g., liking, monetary value, significance and overall quality) and these may or may not be enhanced by pseudo-profound bullshit. Future studies should investigate whether pseudo-profound bullshit titles can enhance peoples’ judgments on these other dimensions (e.g., willingness-to-pay for abstract art).

Finally, given the pattern of results observed by Eriksson (2012) whereby experts in mathematics did not judge nonsense-math containing abstracts to be indicative of higher quality science, it remains an open question whether art experts would demonstrate the effects observed here. If it is the case that art experts themselves endorse a radically subjective view of art, then they should behave similarly to non-experts, such that bullshit should also enhance their perception of an artwork’s profoundness. However, it is also possible that, similar to experts in mathematics, the acquired expertise for artists would allow them to distinguish between descriptions of art that are honest and insightful as opposed to those consisting purely of randomly generated pseudo-profound bullshit. If art expertise does allow one to spot the fakery characteristic of bullshit, at least in the domain of art, then one would expect that art experts, unlike non-experts, would not have their judgements of a piece of art affected by the presence of bullshit.

6.3 Conclusion

Across many domains, people compete for status and prestige by attempting to impress others. In these cases, despite its fakery, the impressiveness of pseudo-profound bullshit may offer individuals a low-cost strategy for impressing others and gaining prestige. While past work has demonstrated how people are receptive to pseudo-profound bullshit, the current study demonstrates a way in which peoples’ susceptibilities to bullshit can be taken advantage of in a social domain. Specifically, we demonstrate how randomly-generating various pseudo-profound bullshit titles and indiscriminately attaching them to either computer-generated or artist-created abstract art images increases the perceived profoundness of abstract art. While extending the current theoretical framework to new domains is an exciting future prospect, for now it can be concluded that at the very least, bullshit makes the art grow profounder.