This paperFootnote 1 examines how Athens’ urban heritage was perceived and promoted during the second and third quarters of the twentieth century.Footnote 2 Advances in urban heritage management over this fifty-year timespan had a profound effect on both the shape and the physical limits of the urban heritage space. Changes in perceptions are best exemplified in the management of Vlasarou, Vrysaki and Plaka, three historic neighbourhoods north of the Acropolis. The first two were hastily demolished between 1925 and 1931 for the excavation of the ancient Agora beneath (1931–), resulting in the creation of a vast archaeological site detached from the modern city's functions. The third was the subject of a pioneering preservation study and eventually an action plan during the 1970s and the early 1980s, which in addition to social objectives also aimed at the restoration of the area's post-Independence urban form and image.

How was Athens’ historical landscape painstakingly constructed so as to exemplify the historiographical narrative of cultural continuity? The emphasis of the present article will be on the wider scale rather than on the historical landscape's constituent parts – the monuments themselves – although key processes, people, and practices are discussed. Restored monuments, the result of physical interventions organized by divisions of the Archaeological Service, will be read as heavily signified texts that reach out to broad and diverse audiences. Influential writings of the period contribute to the discussion, as they testify to the cultural assumptions of the time. Statutes, such as laws on antiquities, royal decrees, and ministerial decisions that placed buildings and sites under legal protection, thus elevating them to heritage status, document official perceptions of what was considered of national importance. A brief description of on-site works of selected preservation projects adds to our understanding of the ever-changing preservation and restoration frameworks in theory and practice.

From the narrative of revival to the narrative of continuity: the heritage landscape of Athens in the 1920s

The first royal decree on antiquities, issued in 1834,Footnote 3 placed under state protection works of architecture and sculpture, everyday objects, and weapons from ancient to early Christian times, reflecting the official ideology of the newly formed Greek state and the prevalence of the narrative of revival in Greek historiography, according to which the ancient nation was awakened during the Neohellenic Enlightenment and was at last liberated from foreign rule. Through this law, based on the 1829 draft law ‘Περί προστασίας των αρχαιοτήτων’ submitted to Ioannes Kapodistrias,Footnote 4 all ancient ruins belonged to the state and private initiative was restricted. Half a century later, a new law on antiquities, issued in 1899,Footnote 5 extended the heritage timespan to include medieval Hellenism, consistent with the tripartite narrative framework of cultural continuity, an articulation of national history based on a genealogical succession of Hellenisms.

The transition from the narrative of revival to the narrative of cultural continuity during the second half of the nineteenth century had a profound effect on the understanding, structure, and perception of what has been called ‘national time’.Footnote 6 This shift of historical paradigm served the irredentist vision of the Great Idea and took shape in publications such as Spyridon Zambelios’ collection of folk songsFootnote 7 or Konstantinos Paparrigopoulos’ history.Footnote 8 The narrative of cultural continuity merged the nation's cultural and political history into a single field,Footnote 9 and its dissemination was accelerated by political events such as the competition among Balkan nationalisms and the clash of opposing irredentist visions.Footnote 10 Cultural continuity recognized the value of the Byzantine heritage,Footnote 11 as well as more recent architectural styles and manifestations of folk culture,Footnote 12 whose study and promotion to the broader culture would become the focus of newly established learned societiesFootnote 13 and state institutions.Footnote 14 By the time of the Balkan Wars cultural continuity had prevailed as an indisputable framework of national history, and writings by Pericles Giannopoulos and Ion DragoumisFootnote 15 show its impact on national imagination and public discourse. Change in the historical paradigm, however, could not be more evident than in the amendment to the founding chapter of the Archaeological Society at Athens in 1917 to include Byzantine and Christian monuments in its scope.Footnote 16

Despite new perceptions and attitudes towards early Christian, Byzantine and post-Byzantine architectural heritage, especially during the time of the state's territorial expansion in the early twentieth century, the Greek capital's heritage landscape was still dominated by its ancient past. Restoration of ancient monuments in Greece began as early as 1834Footnote 17 and by the first decades of the twentieth century had produced a network of monuments on and around the Acropolis, in a form that took only their ancient strata into account. By 1922, the Acropolis had already been purged of its post-classical additions, while landmark classical and Roman remains had already been restored in a similar manner and had become urban focal points within the growing city.Footnote 18 Prominent monuments of this network that made up the Greek capital city's initial heritage space, included the choragic monument of Lysicrates (Fig. 1), Hadrian's Library, the Temple of Hephaestus (Theseion), Philopappos Monument, Olympeion, and Hadrian's Gate.Footnote 19 The restoration of the Panathenaic Stadium had already been completed to host the first modern Olympic Games in 1896. Late belle époque Athens aspired to be an elegant European city, where ancient heritage was beautifully framed by neoclassical public and private buildings, while the already restored Soteira Lycodemou church at the heart of the city and Daphni monastery on its outskirts were pleasant curiosities.Footnote 20

Fig. 1. The choragic monument of Lysicrates (335/4 BC) as seen today. During the nineteenth and early twentieth century, monuments such as this were stripped of their post-classical layers and matched beautifully to the neoclassical dwellings built around them. Demolition of unwanted heritage, in this case a Capuchin monastery established in the seventeenth century, gave the necessary breathing space for their aesthetic enjoyment and made them focal points within the growing city. Juxtaposition of the purified ancient past and the neoclassical present provided a powerful image of the narrative of revival. Photograph by the author.

Large-scale public buildings, accommodating the new institutions of the nation-state, and the lavish residences of the incoming Greek and the foreign bourgeoisie made up the new landmarks of the capital city and were designed in elegant neoclassical proportions and built of high-quality materials. For the middle-class dwellings, built mainly in areas around the Acropolis and the new suburbs, neoclassical references were, however, primarily a design feature that would be limited in the front elevation, leaving interior spaces organized in more traditional patterns.Footnote 21 The juxtaposition of this neoclassical presentFootnote 22 and the purified ancient past established a direct visual link and provided a powerful image of the narrative of revival.

A change of attitude towards the Byzantine heritage of the city is indicated by the royal decree of 1921Footnote 23 which placed under statutory protection a number of surviving churches and monasteries, such as the late tenth-century Agioi Apostoloi Solaki, the mid-eleventh-century Agioi Theodoroi, the late twelfth-century Panagia Gorgoepikoos, the eleventh-century Kaisariani monastery, and the early twelfth-century Agios Ioannis Kynigos. Equally important, the royal decree of 1923Footnote 24 listed as many as 91 historic churches and monasteries in suburbs such as Marousi and Chalandri, and satellite towns and settlements such as Paiania, Koropi and Eleusina.

The change of historiographical – and hence representational – paradigm is echoed in the architectural guides. From Τα Μνημεία των Αθηνών in 1884,Footnote 25 for instance, to Μνημεία Αθηνών in 1928,Footnote 26 city guides would evolve from describing exclusively monuments of classical, Hellenistic and Roman antiquity to addressing the heritage of all three phases of Hellenism. The modern period is represented by neoclassical attractions, such as the Zappeion and the Athenian triptych: the National Library, the Academy of Athens, and the University of Athens.

Dominant representations of built heritage insisted on univocal interpretations based primarily on archaeology and national history. This, however, did not exclude different approaches to cultural continuity. In Αι Παλαιαί Αθήναι (1922), description of Athens’ ancient, Byzantine, and Ottoman built heritage is based on the folk imaginary, making the book itself a reference of the lost pre-modern belief system of lay culture. Contrasting archaeological to folklore interpretations, the author noted of the Philopappos Monument, for instance, that:

Let the archaeologists say what they want, that the monument was erected by the prince of Commagene Philopappos, grandson of King Antiochus Epiphanes and resident of Athens, in honour of his ancestors and the emperor Trajan. The Athenian people know that the monument that tops the hill is the tomb of an old matchmaker who was murdered by a friend after a quarrel due to the failure of the matchmaking he was sent to do.Footnote 27

In Αι Παλαιαί Αθήναι, the Byzantine past was confined to and best represented in churches and monasteries, while Ottoman heritage embraced mosques, khanqahs, the town's madrasa, the Voivode's and the Qadi's mansions, and public baths.

Identification, preservation and restoration of monuments during the interwar period

The aftermath of 1922 saw the influx of refugees, deep political and social divisions, the alternation of pro- and anti- royal governments, coups and the establishment of the Fourth of August regime (1936), which collapsed with the German invasion (1941).

Statutes concerning the Greek capital's Byzantine built heritage, starting with the royal decree of 1921, would continue to be issued throughout the interwar period until 1936, hence re-directing the focus from the centre of Athens to Attica's surrounding areas.Footnote 28 Interestingly, during the Metaxas regime no such statutes were published, indicating perhaps the regime's lack of interest in exploring the potential contribution of this field to social conditioning.

The first three volumes of the Ευρετήριον των μνημείων της Ελλάδος, Footnote 29 a series published by the Ministry of Education and Religious Affairs, identified the entirety of the surviving and historically documented Byzantine and Ottoman-era buildings in and around Athens. Printed between 1927 and 1933, they provided ample documentation for each individual monument described, the vast majority of which were churches and monasteries. Over the years, many of these were elevated to heritage status, and several would eventually be repaired and restored, a wish expressed in the series introduction.Footnote 30 These three volumes can be seen in retrospect as the first stage towards the construction of a network of monuments depicting Hellenism's medieval phase.

Between the wars, the Archaeological Service's initiative intensified, assisting the activities of established learned societies and foreign archaeological institutes. At a time when the city centre was being refurbished with new, multi-storey buildings,Footnote 31 its main task of rescue excavations – which undoubtedly added to the knowledge of the city's historic topography – was complemented by a few systematic excavations. Archaeological excavations within the limits of the ancient city provided further glimpses of Hellenism's first phase and included among others the Acropolis Propylaea (1929),Footnote 32 the Roman Forum (1930–1),Footnote 33 Kerameikos (1927–8),Footnote 34 the North and North-East defensive city walls (1927–8),Footnote 35 and the Odeon of Pericles (1914–32).Footnote 36 Further away from the city centre, sites included the temple of Apollo Zoster in Vouliagmeni (1927–8)Footnote 37 and the Eleusinian Telesterion (1930–6).Footnote 38 Undoubtedly, however, the physiognomy of Athens’ heritage space was mostly shaped by the joint initiative of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens and the Archaeological Society at Athens, which aimed at revealing the Ancient Agora by clearance of the inhabited historic neighbourhoods that laid on top of it.Footnote 39 The revelation of the heart of the ancient city had been a rallying-cryFootnote 40 since the times of the first urban plans of the cityFootnote 41 and a major urban intervention in the centre of the contemporary city, albeit at a time of a housing crisis intensified by the influx of refugees from Asia Minor.Footnote 42 By 1931, when excavations began, most of the properties within the boundaries of the future archaeological site had been expropriated and demolished, amounting to a total of 350 age-old dwellings inhabited by over 5000 people in an area of roughly 25 acres.Footnote 43

Advances in the research of Athens’ ancient topography are best illustrated by Walther Judeich's Topographie von Athen (1931), a valuable reference work on the capital's ancient heritage, aiming at both experts and the amateur. Progress in the restoration of the Acropolis’ monuments is recorded in two well-illustrated publications (extremely rare in terms of project completion documentation), which offer at the same time a glimpse into on-site restoration practices at the time – many deemed unacceptable by our standards. Η Αναστήλωσις των Μνημείων της Ακροπόλεως (1940),Footnote 44 described works at the Propylaea (1909–17), the Erechtheum (1902–8), the Parthenon's north (1922–30) and south (1932–3) colonnades, whereas Η νέα αναστήλωσις του Ναού της Αθηνάς Νίκης (1940)Footnote 45 described the dismantling and re-assembly of the Temple of Athena Nike between 1935 and 1939. There, one may see Nikolaos Balanos’ restoration methodology that included, among other things, combination of unrelated architectural fragments, geometrical deformation of architectural members for optimal adaptation, extensive use of iron ties with insufficient protection from rust, and a widespread use of mortars in conjunction with other building materials, which in the long run proved harmful to the monuments.Footnote 46

Apart from the ongoing work on the Acropolis,Footnote 47 smaller-scale projects by the Archaeological Service included the restoration of the eleventh-century Agia Ekaterini's dome in 1927, the conservation of the frescoes of Agios Georgios church in Galatsi in 1935, the repair of the dome of the katholikon of Agios Ioannis Theologos monasteryFootnote 48 in 1937, the structural repair of the sixteenth-century Asteriou monasteryFootnote 49 in 1937, the restoration of the refectory and the dome of the eleventh-century Kaisariani monasteryFootnote 50 in 1937.

At the dawn of the Second World War, Athens’ Byzantine and post-Byzantine Christian heritage had been thoroughly studied and indexed, most of its surviving examples had received heritage status, while a few conservation projects were already underway. Hellenism's medieval phase began to be promoted, hesitantly asserting its place in the heritage space of the city. The increasing concern for the city's Byzantine and post-Byzantine Christian heritage is evident in Αι εκκλησίαι των Παλαιών Αθηνών (1940)Footnote 51, an important publication which brings forward the degree of destruction and physical loss inflicted in this heritage typology as a result of the purification of the city's archaeological heritage during the nineteenth century.Footnote 52 By highlighting the significance of the surviving historical churches, the author argued for their protection and restoration.

The new national law ‘Περί αρχαιοτήτων’ addressed almost all aspects of heritage protection posed by the 1931 Athens Charter – the first international document on heritage protection – and re-affirmed Greek heritage as all works of art and architecture originating from a period spanning from antiquity to the time of medieval Hellenism.Footnote 53 By replacing law 2646 of 1899, it became the main statutory tool for heritage protection.

As for Hellenism's modern phase, represented mostly by post-Independence neoclassical heritage, Kostas Biris’ three volumes of Αθηναϊκαί Μελέται can be seen as the first stage in a long process towards the legal protection and restoration of Athenian neoclassicism. Published between 1938 and 1940,Footnote 54 this work describes in great detail Greek neoclassicism's representative examples, main typologies, and variations, advocating the style's suitability for the nation's capital city. There, the author argued that ‘it was only natural for the architects that came to build their works “under the shadow of the monuments of classical antiquity”, to feel and believe with fervour in this ideology’, believing that neoclassicism fitted Athens more than any other post-classical style of architecture.Footnote 55 What came to be called ‘neoclassical’ in popular discourse embraced all nineteenth and early twentieth-century historicist and eclectic architectural styles and was until the 1940s a living present, amounting for over 70% of the 30,000 new residences built during the interwar within city limits.Footnote 56 Such buildings would be acknowledged as heritage only after the 1950s when a large part of them would be demolished en masse to make room for the multi-storey reinforced-concrete frame apartment buildings.

It is important to note that by the 1930s, new perceptions on heritage started challenging its pre-eminent ideological content. Its relevance to tourism and tourism development, already apparent in the touring guides of the previous decade, was publicly discussed on occasions such as the 1934 yearly general assembly of the Archaeological Society, where its general secretary argued that, if Greece was to become a leading tourist destination, then the Society ought to support the state's archaeological and restoration initiatives.Footnote 57

Resuming action after the Second World War (1946–52)

During the months between the declaration of the Greek-Italian war (October 1940) and the Occupation (April 1941), the Archaeological Service ceased restoration activities and focused on shielding museums against air raids and safeguarding their exhibits from looting.Footnote 58 Throughout the Axis occupation it existed only in a rudimentary form. Surprisingly, the small church of Agios Elissaios and the adjacent Ottoman gate of the Logothetis- Chomatianos residence in Monastiraki,Footnote 59 were placed under statutory protection by the only piece of legislation on the subject issued during this dark period.

After the war, the age-old demand for the full revelation of the ancient city would be imprinted in Kostas Biris’ plan for the reconstruction of Athens (1946), where he proposed the expropriation of extensive urban areas around the Acropolis, Kerameikos, and Plato's Academy. He noted that the full uncovering of ancient sites was a universal demand, an issue of upmost national importance and should go on even if external contribution was needed.Footnote 60 Within this area, ancient streets and urban layouts would be restored to their ancient levels, Byzantine churches would be brought back to their original form ‘after we relieve them from later historical additions and beautifications by contemporaries’Footnote 61 and a limited number of significant nineteenth-century neoclassical public buildings would be kept and repaired. Biris’ plan imprinted the dominant vision of Athens’ heritage space, composing of heritage vessels of all three phases of Hellenism.Footnote 62

During the early years after the war, the Archaeological Service would not resume or initiate a single restoration project due to its meagre funding capability, constraints in its internal organization, and the general political instability. Its main activity involved the adoption of measures and the realization of urgent repairs in war-torn monuments and artefacts,Footnote 63 as several archaeological sites had been turned into military compounds or theatres of military operations during the Second World War and the Civil War.Footnote 64 Political instability also affected the Archaeological Society at Athens, which resumed its archaeological activity as late as 1948 in a mere four locations throughout the whole national territory.Footnote 65 Between 1946 and 1947 foreign schools of archaeology were not allowed to carry out excavations.Footnote 66

Law 1469, issued in 1950,Footnote 67 expanded the protective framework of law 5351 on antiquities (1932) to works of art and architecture from after 1830, covering Greek variations of neoclassicism and Greek vernacular architecture, and thus becoming an additional legal tool for listing monuments, now embracing modern Hellenism's built forms.

Although a ministerial decision in 1945 added the Kleanthis residence to the heritage register,Footnote 68 listing of historic monuments would in essence resume only after 1950, when between 1950 and 1952 another six statutes would elevate seventeen building structures to the status of heritage monument. These were mostly neoclassical buildings and other monuments associated with the early period of the Greek capital, such as the lavish Iliou Melathron,Footnote 69 Georgios Karaiskakis’ tomb in Neo Faliro,Footnote 70 the mansion of the Duchess of Plaisance in Penteli,Footnote 71 and the restored Panathenaic Stadium.Footnote 72 Most notably, ministerial decision 21980/250Footnote 73 elevated to heritage status in 1952 iconic nineteenth-century public buildings, including:Footnote 74 the Old Royal Palace (1843), the National Observatory (1846), the Arsakeion school (1846), the University of Athens (1864), the National Technical University of Athens (1878), the Academy of Athens (1885), the National Library (1888), the Archaeological Museum (1889), and the National Theatre (1891). In a time when the Greek capital city saw its lower and middle-class neoclassical building heritage demolished to make room for modern block of flats,Footnote 75 these additions to the heritage list were exceptions to the rule that saw neoclassicism as an urban anachronism. Still functional although listed,Footnote 76 many of the above heritage buildings were repaired, converted and altered during the following decades in non-reversible ways with building materials and construction methods unfit for architectural preservation purposes, or worse, similar to the original – thus making differentiation between authentic tissue and restoration intervention an impossible task.Footnote 77

In Athens, increasing interest in nationally conditioned vernacular typologies was expressed in the low-level, pre-modern, courtyard-houses once dominant in the urban landscape. Seeing through a romantic lens, Τα παλαιά Αθηναϊκά σπίτια (1950) described this by-now obsolete urban typology through surviving case studies, hailing it as the place where ‘the ethnological riches of Hellenism were kept in safety’.Footnote 78 The author highlighted similarities with ancient Greek, Byzantine and Ottoman-era vernacular architecture and arguing against neoclassicism as intrinsically foreign to the local built environment, he advocated that these pre-modern dwelling types were the only true carriers of ‘a legitimate and truthful memory’.Footnote 79

Identification of monuments during the post-war period (1952–74)

The period between 1952 and 1974 saw the influx of domestic migrants and the rapid urbanization of Athens, the persecution of the defeated of the Civil war, the perseverance of the Left through Eniaia Dēmokratikē Aristera, the consolidation of right wing governments (1952–63), social change brought by the short period of the centrist Enōsis Kentrou in power (1963–5), political instability (1965–7), and the establishment of a military junta (1967–74). New entries in the heritage register embrace monuments from antiquity, Byzantine Christianity, and the history of the modern nation-state, thus solidifying the tripartite periodization of national history into the urban history of the city.

Between 1952 and 1963, a period of conservative rule, a large number of heritage protection statutes listed a still larger number of buildings and sites. Overall, thirty ministerial decisions concerned forty-nine buildings and sites, the majority of which related to the city's ancient past, either by defining new archaeological spaces or by expanding the boundaries of existing sites. For instance, Ministerial Decision 125350,Footnote 80 issued in 1956, designated several new archaeological sites, such as the Roman Stoa in the churchyard of Agia Ekaterini, the Roman villa within the grounds of the Zappeion Hall, the temple of Aphrodite on the south slope of the Ardittos hill, and Dontas cave. The same statute expanded the boundaries of established archaeological sites, such as Kerameikos, Olympieion, or the south and the west slopes of the Acropolis. Similar ministerial decisions identified new archaeological sites around important remnants of the ancient urban topography, such as parts of the defensive wall,Footnote 81 Kolonos hill,Footnote 82 Plato's Academy,Footnote 83 and the Ilissos river bed.Footnote 84

Similar statutes elevated a small number of Christian temples and nineteenth-century public buildings into heritage status. Notable examples included the thirteenth-century temple of Asomatoi Taxiarhes in Petraki monastery,Footnote 85 the nineteenth-century Hellenic-Byzantine Zoodohos Pigi in Akadimias Street, the neo-Byzantine Panagia Chrysospiliotissa in Aiolou Street,Footnote 86 as well as the neo-Byzantine Athens Eye Clinic.Footnote 87

It has been argued that during this time a monument's touristic value came to acquire equal weight to its national value, becoming an additional criterion when considering a heritage building for restoration.Footnote 88 The tourism parameter was stressed by Anastasios Orlandos in his 1954 account of the Archaeological Society's activities, highlighting the educational value of archaeology and its contribution to the national economy. Like his predecessor in 1934, he argued that engagement with monuments should be approached through the double prism of both cultural improvement and tourism.Footnote 89

This boost in repair and restoration projects would not be limited to the already popular ancient heritage but would be expanded across all expressions of the three phases of Hellenism. The five-year tourist plan announced by secretary of state Konstantinos Tsatsos in May 1959, set explicit priorities of which two are relevant here. They concerned the development of established archaeological sites – as their further growth was guaranteed and easier – and the promotion of new tourist destinations, which would showcase Byzantine and modern Greek (neoclassical and vernacular) built heritage.

The third hierarchical aim is the establishment of new tourist sites of international interest, in places where this can be achieved in a quick and least costly manner. At that point every conscious effort will be made so that parallel to the development of the country's classical monuments, which are already internationally renowned, to turn tourist attention to Byzantine monuments and all other manifestations of neohellenic culture.Footnote 90

Mainstream urban historiography echoed the dominant post-war discourse and followed established historiographical models. For instance, victimization of the nation and suffering under its many foreign rulers, a common perspective of national history at the time, set the narrative framework for the tale of late Byzantine and Ottoman Athens in the first part of Παλαιαί και Νέαι Αθήναι.Footnote 91 A small number of publications, however, posed new research questions and sought new interpretations of old themes. Τα Αττικά του Εβλιά Τσελεμπή was a translation of the section of Evliya Çelebi's seventeenth- century Seyahatname on Athens and its neighbouring areas. Ottoman-era Athens is described in the words of an Ottoman eye-witness, documenting the dominant worldview and offering at the same time an insight into the Athenians’ perception of their city and its monuments. Like Kampouroglou's Αι Παλαιαί Αθήναι, this book documented nowadays unfamiliar and rather alien significations of the city's major monuments, which as the author pointed out in his introductory remarks were not due to Evliya Çelebi's rich imagination but stemmed from a long gone socio-political context.Footnote 92 A year later, John Travlos’ highly acclaimedFootnote 93 and well-illustrated Πολεοδομική εξέλιξις των Αθηνών Footnote 94 narrated the development of the city, from the first recorded prehistoric settlement to the nineteenth-century planned neoclassical capital, based on bibliography and archaeological data from excavations, in many cases supervised by him. The book's material was presented in twelve historical periods, following a novel narrative that reflected changes in urban form rather than the nation's three historical phases, each time describing the city's topography and representative monuments. Athens’ transformation from a small Oriental town to a contemporary capital city of a nation state emerging into modernity is the subject of Αι Αθήναι: Από του 19ου εις τον 20ον αιώνα.Footnote 95 Published in 1966, it became an essential reference point for students of the modern city due to the rich variety of architecture and town planning issues it deals with, brilliantly describing the rise and fall of the neoclassical phase of the Greek capital, a paradise lost, which by the 1960s could already be seen with a romantic gaze.

The establishment of the Ephorate of Modern Monuments in 1963,Footnote 96 thirteen years after the publication of law 1469 on the protection of modern monuments, marks the official recognition of the distinctive challenges of the study, protection and preservation of monuments and sites belonging to the modern period of the nation. In its early years, its jurisdiction covered the entire national territory and its focus was centred on the vernacular heritage of the rural mainland and the Cycladic islands. Decades later, it would also cover buildings and sites of the post-revolutionary period, including the neoclassical variations of the capital city.

During the time of the Centre Union in power and the years of political instability, between 1963 and 1967, there were few new additions for Athens in the built heritage register, compared to a great number for surrounding areas.Footnote 97 A mere three ministerial decisions concerned the seventeenth-century Agios Dimitrios Oplon in Patissia, the seventeenth-century Agia Zoni in Treis Gefyres, and the redefinition of the boundaries of the archaeological site of Plato's Academy.

After the suspension of parliament and the establishment of a military dictatorship between 1967 and 1974, sixteen ministerial decisions identified fifty new heritage buildings and sites.Footnote 98 Notable examples included:Footnote 99 the Benizelos mansion (early eighteenth-century),Footnote 100 the administration building of the Greek Army academy at Pedion tou Areos (1904),Footnote 101 the Dekozis-Vouros mansion at Klafthmonos Square (1834),Footnote 102 the Sarogleio building (1932),Footnote 103 and the military hospital of Makrygiannis Street (1836).Footnote 104 However, two ministerial decisions stand out as containing the largest number of entries. The first, Ministerial Decision 2290 (1972),Footnote 105 was concerned with the registration of eighteen churches of the Byzantine and the Ottoman era,Footnote 106 the Ottoman Tzistarakis mosque, and the ruins of the Ottoman madrasa, as well as the Roman-era Tower of the Winds. The second, Ministerial Decision 41004 (1972),Footnote 107 was concerned with the statutory protection of sixteen buildings of the post-Independence period, such as: the Crown Prince's palace (1897), Benaki mansion (1895), St Denis Catholic Cathedral (1865), Agia Eirini on Aiolou Street (1850), the Metropolitan Cathedral of Athens (1862), and the Stathatos mansion (1895).

The trend of registering high-profile nineteenth century architecture began in the early 1950s and continued throughout the examined timespan. By contrast, innumerable humbler neoclassical buildings were demolished during post-war reconstruction, despite a general outcry and the demands for documentation before they were gone for ever.Footnote 108 As for Byzantine and post-Byzantine Christian heritage, the few inner city small churches that were not already registered during 1921 and 1923 received heritage status in 1972, echoing the dictatorship's Ελλάς Ελλήνων Χριστιανών (Greece of Christian Greeks) slogan.

Depicting the narrative of national continuity. Preservation and restoration of ancient and Byzantine heritage (1952–74)

Between 1952 and 1974, the relevant subdivisions of the Archaeological ServiceFootnote 109 organized and supervised projects on monuments in Athens and its outskirts, ranging from structural repair and consolidation of crumbling ruins to stylistic reconstruction of the original form. They also oversaw landscaping and site embellishment projects aiming to enhance visitor access and maximize appeal.

By 1974, the pre-war network of monuments comprising mostly classical and Roman structures had already expanded to include a further eighteen historic buildings, mostly chapels, churches and monasteries of the Byzantine and Ottoman era, which exemplified Hellenism's medieval phase and served post-war ελληνοχριστιανισμός.Footnote 110 The additional monuments included:Footnote 111 Agioi Asomatoi in Thisseion (1959–60), the early twelfth-century Agios Ioannis Kynigos (1960, 1963, 1966), Petraki monastery (1960),Footnote 112 (1967, 1971–3),Footnote 113 Agios Ioannis Prodromos (1961),Footnote 114 the sixteenth-century Agia Dynami (1962, 1965),Footnote 115 the tenth-century Agios Spyridon and Agios Nikolaos in the Davelis cave (1962),Footnote 116 (1971–3),Footnote 117 Agios Kosmas at Helliniko (1963),Footnote 118 the sixteenth-century Agios Ioannis Karea (1963–4, 1968–9, 1973–4), the eleventh-century Metamorphosē tou Sotēros on the Acropolis’ northern slope (1965), the seventeenth-century Panagia Romvi (1965),Footnote 119 the early Christian basilica at Illissos (1965),Footnote 120 the eighteenth-century Agios Georgios on Lycabettus (1965),Footnote 121 the eighteenth-century Agios Athanasios Kourkouris at Thiseio (1966),Footnote 122 the eleventh-century Agioi Theodoroi at Klauthmonos (1966, 1969),Footnote 123 the sixteenth-century Agios Nikolaos Chostos (1966),Footnote 124 Agios Ioannis at Vouliagmenis Avenue (1969),Footnote 125 the seventeenth-century Agioi Anargyroi of the Holy Sepulchre (1972–4),Footnote 126 and the fifteenth-century Agios Ioannis Theologos at Menidi (1972–4).Footnote 127

Work also continued at: Daphni monastery (1955–60),Footnote 128 (1967, 1971–4),Footnote 129 the eleventh-century Kaisariani monastery (1952, 1958–60),Footnote 130 the sixteenth-century Asteriou monastery (1959, 1969, 1970, 1972),Footnote 131 Agios Ioannis Theologos (1963–4),Footnote 132 Taxiarhes church at Marousi (1967),Footnote 133 the early eleventh-century Sotera Lykodemos church (1967–9),Footnote 134 as well as the second-century AD Odeon of Herodes Atticus (1952–3, 1961–2, 1964–7), the first-century BC Roman Agora (1964–5),Footnote 135 the fourth-century BC Theatre of Dionysus (1967)Footnote 136 and the second-century AD Hadrian's Library (1967–9)Footnote 137.

Major landscaping and site embellishment together with archaeological survey and minor restoration work took place on the slopes of the Acropolis, concerning for instance the area between the sanctuary of Dionysus EleuthereusFootnote 138 and the AsclepieionFootnote 139 (1962, 1963–6), and the Acropolis’ northern (1965–6, 1969)Footnote 140 and western slopes (1965–6), which by then had been inscribed as archaeological sites.

The brief description of representative preservation projects that follows helps to portray the particularities of the post-war era. The examples come from the breadth of the geographical scope of the essay and show the extent and the kind of physical interventions which were allowed, many of them unacceptable today.

Restoration of the second-century AD Odeon of Herodes Atticus, for example, was overseen by the Directorate of Restoration and on-site works between 1952–3 and 1961–2Footnote 141 aimed at the completion of the koilon by reconstruction of the missing sections. In the archaeological reports of the works, which received additional funds from the Archaeological Society at Athens during the first stage, one finds that although great effort was made to keep as much original material in place as possible, insufficient knowledge of the theatre's architectural details necessitated the construction of whole new sections in reference to the theatres of Epidaurus, Delos, and Oropos,Footnote 142 a strategy that undoubtedly led to a fantasized ideal form.Footnote 143

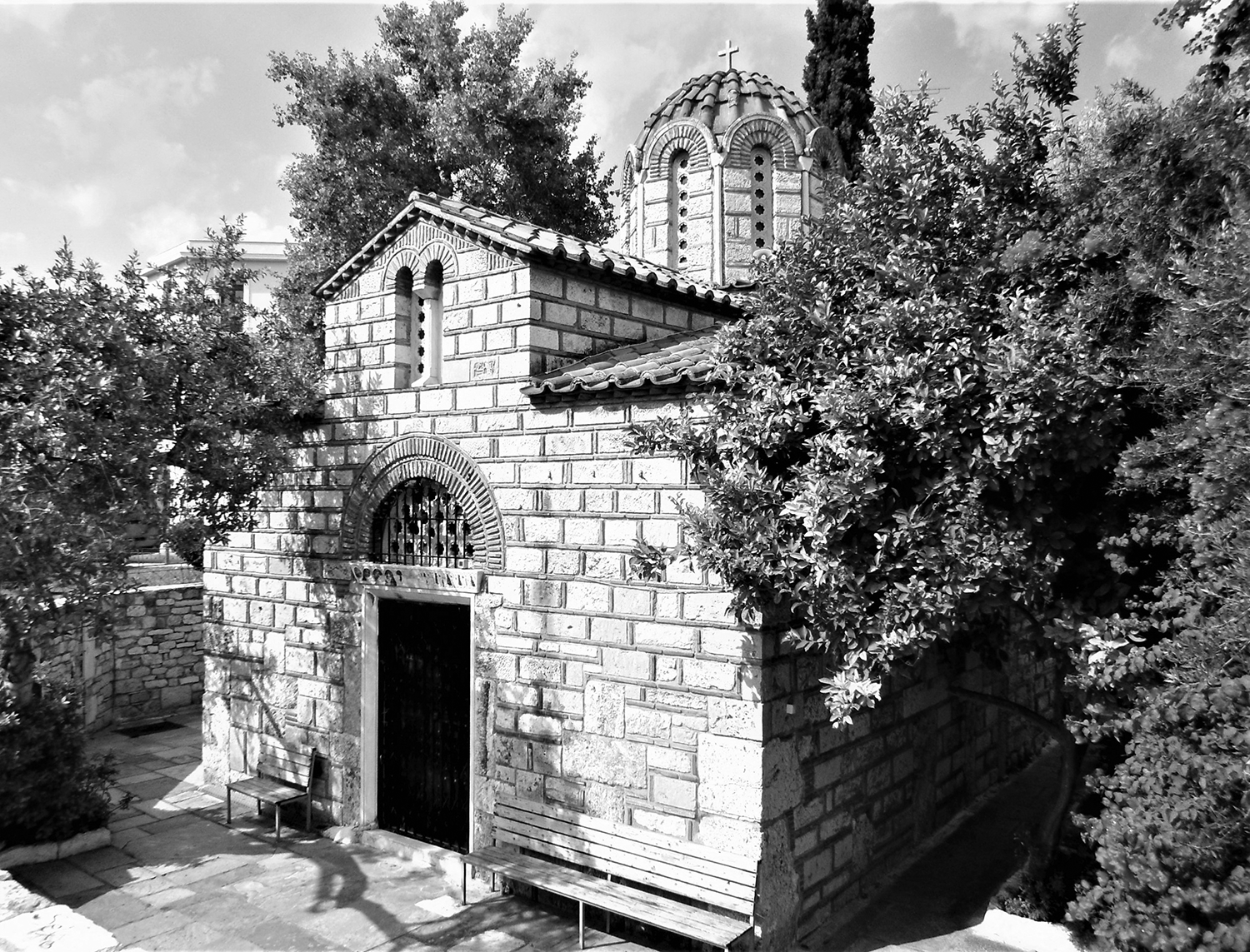

At the north foot of the Acropolis, the restoration of the eleventh-century Metamorphosē tou Sotēros (Fig. 2), a monument described in the Ευρετήριον μνημείων,Footnote 144 took place in 1965 and was jointly overseen by the Ephorate of Byzantine Antiquities and the Directorate of Restoration. Major on-site works included replacement of interior plasterwork, roof re-tiling, strengthening of the masonry and substitution of a reinforced beam from an earlier consolidation intervention, as well as placement of new floor tiles in front of the crypt and conservation of wall paintings.Footnote 145 A new building survey compiled during works generated new data on the building's history and architectural features and helped restorers deliver this small Byzantine church to its original historic form and architectural detailing.

Fig. 2. The eleventh-century Metamorphosē tou Sotēros at the north foot of the Acropolis as seen today. Photograph by the author.

In the city centre, works at Agioi Asomatoi in Thisseion (Fig. 3) between 1959 and 1960 aimed to reconstitute the original form after an 1842 depiction by André Couchaud,Footnote 146 a French architect who lived in Athens for short periods during the late 1830s and early 1840s. The project was funded by the Archaeological Society at Athens and carried out under the guidance of the architect Eustathios Stikas, head of the Directorate of Restoration. After demolishing late nineteenth-century additions, the landscaping of the exterior space that followed included even the relocation of various city functions, so as not to disturb the overall appreciation of the building. The resulting monument was praised as a true jewel,Footnote 147 despite the controversy it raised.

Fig. 3. The eleventh century Agioi Asomatoi at Thiseio as seen today. In the late nineteenth century it was greatly enlarged and an elaborate bell tower was added at its west side. Between 1959 and 1960, restoration projects by the Directorate of Restoration reinstated the monument to its original Byzantine size and form. Photograph by the author.

On Hymettus, work at Agios Ioannis KynigosFootnote 148 resumed during 1960, 1963 and 1966. Demolition of recent building additions revealed the iconic arches of the portico, which were then carefully rebuilt, adding to the monument's picturesque appeal. On-site works included rebuilding of the original window openings and the belfry, removal of exterior plasters, and repointing of the masonry. In the interior, plaster was removed to reveal eighteenth-century wall paintings on top of a thinner layer which was dated between the late thirteenth and early fourteenth century. In the courtyard, recent buildings were demolished and the original floor slabs were revealed and new added where missing.Footnote 149

Likewise, work at the sixteenth-century Agios Ioannis KareaFootnote 150 was initially carried out between 1963 and 1964, based on a building programme submitted in 1961. Recent additions were demolished, while the ruins of the south cells and the arched quarters of the north side were revealed and fully reconstituted. In parallel, the external courtyard was paved, whereas the stone stairway north of the temple and the south defensive wall were carefully reconstructed.Footnote 151 During works between 1968 and 1969 and from 1973 to 1974, interventions concentrated on the perimeter walls and the south and east cells, including structural consolidation, extensive earth removal and reconstitution of the original floor levels, complete reconstruction of the first floor cells and the construction of a uniform single pitched roof.Footnote 152

Restoration practices during this period remained unchanged from before the Second World WarFootnote 153 and were defined by potentially conflicting parameters: vague national laws, strong personal views, the increasing self-confidence of the institutions involved, alongside international charters and guidance.Footnote 154 Careful treatment of and respect for all historic phases of a monument, for instance, was an important resolution of the Venice Charter – then the main international preservation document – and was not unknown to people setting building programmes and restoration aims. Eustathios Stikas, head of the directorate of Restoration, was one of the Charter's key signatories. Yet the demolition of historic building additions was a common practice, which together with frequent full-scale reconstructions, led to idealized ‘original’ forms that can potentially give the impression that restored monuments come to our present in their conditioned form and that later building layers and additions – and thus their whole epoch – never existed.

Restored monuments such as these made up the expanded heritage space of Athens. The city, which up to the early 1950s had sought mostly to display its ancient heritage, was enriched with churches and monasteries of its Byzantine and Ottoman past. Two pivotal projects, however, would have a lasting effect and double Athens’ heritage space: Philoppapou hill and the Ancient Agora.

Work at the Acropolis and Philopappou hill (1951–7) was highly praised.Footnote 155 It was initiated by order of the head of the government, approved by the Archaeological Service and executed by the ministry of Public Works.Footnote 156 Landscaping of the Acropolis’ south slope and Philopappou (1954–7) included also the reconstruction of the sixteenth-century Agios Demetrios Loumbardiaris church from foundations, in which the architect Dimitris Pikionis incorporated elements from Greek traditional architecture.Footnote 157

As for the unearthing of the Ancient Agora by the American School of Classical Studies at Athens, the site's central location, the scale of works and the significance of the monuments in the ancient urban topography, placed it in the forefront of all heritage intervention in the capital city. Individual projects included the site's landscaping (1954–5), the reconstruction of the mid-second-century BC Stoa of Attalos (1953–6) as the Ancient Agora's museum, and the reconstruction of the tenth-century Agioi Apostoloi Solaki (1954–6). Landscaping of the Ancient Agora followed landscape architect Ralph E. Griswold's proposal, aiming at the reconstitution of the ancient scenery through planting species known to have existed there during antiquity. However, it was the complete reconstruction of the Hellenistic Stoa from scratch, a rare example in the history of building restoration practice, which attracted most of the attention, taking on a Cold War symbolism. At the opening ceremony, Ward M. Canaday – president of the American School's Board of Trustees and President Eisenhower's special envoy – stated that the restored Stoa of Attalos was a living monument and a tribute to freedom, one of the shared ideals between Greece and America.Footnote 158 At the same event, minister Konstantinos Tsatsos argued that the archaeological spade was one of the many weapons of the United States in the battle for liberty, adding that the unearthing of democracy's birthplace helped to promote the great ideals of freedom, justice and solidarity.Footnote 159 The director of the Agora excavation Homer Thompson believed in the restored building's educational value, arguing that it would generate a multisensory experience and encourage a deeper understanding of everyday life in ancient times.Footnote 160 In an article to Αρχιτεκτονική, he explained that it would also help visitors comprehend the size and form of this particular Hellenistic civic typology, experience the beauty of the colonnade and the interplay of light and shadow, and imagine the shape and size of the rest of the Agora's buildings.Footnote 161

In some quarters, the restored Stoa raised fierce criticism. Architect Patroklos Karantinos, for instance, described the building as a bleak and empty reproduction, a pointless stage set, a dissonant cry without soul or spirit, and a foreign monument among the ancient ruins, arguing that restoration should never proceed to reconstruction.Footnote 162 Anastasios Orlandos, head of the Directorate of Restoration, was particularly sceptical, and openly expressed his reservations even during the opening ceremony.Footnote 163

Controversy, resentment and change of paradigm

Controversy was not limited to the reconstruction of the ancient Stoa. The general resentment over the scale and speed of interventions to heritage buildings is testified to by articles in literary journals and the daily press. In Αι ψευδαναστηλώσεις των μνημείων μας and in Η «αναστύλωσις» του ναού των Αγίων Ασωματων, for example, Kostas Biris took as an example the recent restoration of the eleventh-century Agioi Asomatoi in Thisseion (Fig.3) and criticized the inadequate building analysis, the lack of sufficient documentation and the uninformed character of the final design, even arguing that on-site works lacked scientific method and in many cases did not follow archaeological protocols.Footnote 164 For him, such restoration projects were harmful to the monuments, shameful to the Archaeological Service, and ultimately worthless to Greek tourism.Footnote 165

Resentment over the drastic interventions in ancient monuments led to a crisis within the Archaeological Service. After the establishment of the military dictatorship in 1967, political persecutions and staff dismissals led to animosity towards the Service's new administration and reluctance for cooperation with the new authorities.Footnote 166 In this, almost idleFootnote 167 period only some ongoing repair and restoration took place.

Change came with the fall of the military regime in 1974. Article 24 of the new Constitution of 1975 guaranteed the protection of the natural and cultural environment as a state responsibility. New channels of communication – especially after joining the European Economic Community in 1981– facilitated the flow of ideas and knowledge on built heritage preservation. In contrast to earlier periods, the field became increasingly scientific, with a growing number of inter-disciplinary studies and documentation preceding on-site works.Footnote 168 Extensive articles in journals such as the Archaeological Service's Αρχαιολογικόν Δελτίον, as well as the establishment of specialized institutions such as the Directorate for archives and publications, show the changing practices. Increasing multi-disciplinarity in heritage preservation and management meant that monuments began to lose their quintessential national connotations and were studied and preserved each for its own historical and cultural merit. Reappraisal of history in the last quarter of the twentieth century brought forward new heritage signifiers, such as the shooting range of Kaisariani – an important site in the history of the Left – or the Gasworks Complex on Peiraios Avenue – a landmark of the city's industrial heritage – listed in 1984 and 1986 respectively.Footnote 169 EEC accession also meant that international documents, such as the Amsterdam declaration in 1975, a major international text in the protection and preservation of urban heritage, were incorporated into national legislation.

This paradigm shift could not be more evident than in Professor Dionysios Zivas' Μελέτη παλαιάς πόλεως Αθηνών, a pioneering study compiled between 1973 and 1975, which provided for the first time a rigorous social and urban analysis of the factors behind Plaka's urban degradation. Plaka, a historic neighbourhood at the foot of the Acropolis, had become one of Athens’ most run-down areas, yet contained a large number of nineteenth-century built typologies that had survived post-war reconstruction due to the area's then impracticability for profitable real estate development. The second part of the study, entitled Μελέτη Αντιμετώπισης Προβλημάτων Πλάκας, was compiled between 1978 and 1981 as a road map for the area's urban and social regeneration, giving high priority to the repair and re-use of its heritage buildings (Fig. 4). Based on a set of strict principles, these proposals treated Plaka as a single entity, retained its existing form and residential character and banned incompatible uses. Measures were also proposed against increasing land values and gentrification, new private and public amenities were prescribed in an attempt to modernize living conditions, and the overall image was buffered by restrictions regarding shop fronts and aerial cables.Footnote 170

Fig. 4. Aspect of Tripodon street in Plaka as seen today. Nearly forty years after the implementation of the Μελέτη Αντιμετώπισης Προβλημάτων Πλάκας the overall image of the area has been tamed, whereas private and public nineteenth and early twentieth-century heritage buildings have been repaired and restored almost in their entirety. Photograph by the author.

Conclusions

At the outset, heritage management in Athens aimed to identify and restore the city's ancient past. During the nineteenth century, the heritage space of Athens was centred on and around the Acropolis and comprised mostly Classical and Roman monuments that had been stripped of later historical layers. Before 1922, Athens’ neoclassical present framed its restored ancient past beautifully, in an evident reciprocity.

In a process accelerated by social and political developments, including the rise of Greek irredentism and the state's territorial expansion, Greek history-writing would adopt by the end of the nineteenth century the narrative of cultural continuity, which equally emphasized each of the three main cultural phases of Hellenism. As a result, newer visions for the capital city's heritage landscape embraced the city's Byzantine and neoclassical heritage. Between the wars, the city's surviving historic churches and monasteries were identified and indexed, many received heritage status, while a few accommodated preservation projects. After the war, most of the Byzantine monuments in the city centre would be preserved and presented in an idealized form, expanding the scope of the heritage space of Athens. The extensive application of standardized, in many cases unscientific, on-site practices eventually led to a uniformity of easily recognizable features, creating stereotypes easily read by all.

At the same time, post-war laws facilitated the legal protection of modern monuments and thus the registration of the city's high-profile post-revolutionary neoclassical typologies. This did not apply, however, to the less impressive middle-class examples of this architectural style, which were demolished and replaced by the apartment buildings of post-war reconstruction. The remaining few would be listed and preserved after 1974, during the cultural regeneration that followed the collapse of the military junta. Conditioning the heritage space of the capital city to showcase the three phases of Hellenism was a cultural project that extended over most of the twentieth century, irrespective of government or political context. Despite becoming ever more entangled in tourism development, built heritage management maintained its nation-building agenda throughout the period, drawing the attention of wider audiences, and inspiring in many cases heated debates over a monument's final form and the on-site practices involved. After the fall of the military regime in 1974, radically new cultural directions led to new preservation principles and practices, in tune with the increasingly scientific character of the field.

Over the twentieth century, the heritage space of Athens was constructed to reflect the narrative of cultural continuity, comprising a collection of staged glimpses of ancient, Byzantine and modern monuments, and thus depicting the established view of the national past, which involved the exclusion or even eradication of dissonant pasts and heritage typologies. What would the heritage landscape have looked like, had the narrative of cultural continuity not prevailed, or even had monument preservation aimed to illustrate the history of the place and its people and not that of the nation? The contingency shaping the historical landscape is not unique to Athens, it is rather innate to heritage management. Examples such as this are case studies in modernity's appropriation of the past and highlight the fact that heritage buildings do not stand independently but are imbued with the significance bestowed by a dominant present.

Georgios Karatzas is a practising architect, registered in Greece and the United Kingdom. He studied at the University of Dundee and the Glasgow School of Art and completed postgraduate programmes in architectural conservation and in town and regional planning. His PhD thesis at the Technical University of Athens investigated aspects of built heritage management in nineteenth and twentieth-century Greece. He has collaborated with architectural practices in Athens and Edinburgh. Since 2013, he has been project architect on various heritage building restoration projects at the Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports.