Introduction

Though numerous studies have suggested religion and spirituality to be associated with mental health benefits for believers (Koenig et al., Reference Koenig, King and Carson2012; Page et al., Reference Page, Peltzer, Burdette and Hill2020), especially in later life (Krause, Reference Krause2008), an increasing number of studies have focused attention on the detrimental effects of certain facets of religion. Scholars have appropriately deemed this the “dark side” of religion (Ellison and Lee, Reference Ellison and Lee2010; Hill and Cobb, Reference Hill, Cobb and Blasi2011), and empirical work in this domain often involves an assessment of religious/spiritual struggles. Spiritual struggles may be characterized by doubt or uncertainty about religious/spiritual beliefs, troubled relationships with God, or negative interactions with members of one’s church (Hunsberger et al., Reference Hunsberger, McKenzie, Pratt and Pancer1993). An expanding body of research finds that greater doubts about faith are associated with increased psychological distress (Ellison and Lee, Reference Ellison and Lee2010; Galek et al., Reference Galek, Krause, Ellison, Kudler and Flannelly2007; Krause, Reference Krause2003; Upenieks, Reference Upenieks2021a).

From a lifespan perspective, religious doubt generally tends to decline in older adulthood (Krause and Ellison, Reference Krause and Ellison2009). Nevertheless, there is evidence that nearly half of American older adults express at least some uncertainty about their faith (Krause and Ellison, Reference Krause and Ellison2009; Upenieks, Reference Upenieks2021b). In the current study, we situate pastoral support from a religious clergy member (e.g. pastor, minister, priest) as an important resource within the church to help older adults overcome their spiritual struggles. Pastoral support can be loosely defined as activities engaged in by a clergy member to care for the needs – spiritual or otherwise – of congregants, serving to foster the spiritual, mental, and physical well-being of co-congregants (Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Ellison, Chatters, Levin and Lincoln2000). Trends toward population aging in the United States are accompanied by a shortage of mental health professionals trained specifically to work with older people (Jeste et al., Reference Jeste, Alexopoulos, Bartels, Cummings, Gallo and Gottlieb1999). Older adults are more likely to seek help from a religious leader than from any other source, including psychiatrists, psychologists, doctors, marriage counselors, and social workers for personal or mental health problems (Pickard et al., Reference Pickard, Inoue, Chadiha and Johnson2011; Pickard and Tang, Reference Pickard and Tang2009). However, noticeably absent from this body of work is a consideration of clergy as resources to combat the pernicious effects of spiritual struggles. This is a surprising oversight, given the extensive theological training of clergy members in matters related to uncertainty of faith.

Drawing from a longitudinal, nationally representative sample of Christian older adults, this study has three research objectives. First, we ask, relative to those with consistently no doubt about their faith and those who manage to resolve their doubt, do older adults with persistent or increasing religious uncertainty fare worse in their mental health? Second, we consider whether informal support from a pastor mitigates the detrimental health effects of increasing or persistent doubt. Finally, we assess whether these associations are contingent on gender, given that men and women have different propensities to engage in religious/spiritual (“R/S” henceforth) practices in later life and may be more or less impacted by religious doubt and the receipt of pastoral support (Damianakis et al., Reference Damianakis, Coyle and Stergiou2020).

Background

Religious/spiritual struggles have been conceptualized as ultimate existential concerns, addressing matters of utmost importance such as the existence of a higher power, accuracy of spiritual truths, and questions concerning individual purpose and meaning (Exline, Reference Exline, Pargament, Exline and Jones2013). Given the seriousness of doubts or uncertainties of faith, nationally representative samples have shown that people who experience greater R/S struggles have higher levels of depression (Galek et al., Reference Galek, Krause, Ellison, Kudler and Flannelly2007; Krause and Ellison, Reference Krause and Ellison2009; Upenieks, Reference Upenieks2021a).

Longitudinal studies of older adults also replicate these findings, using outcomes related to, but conceptually distinct from, depression. In these studies, it is argued that a failure to resolve these doubts might increase death anxiety, especially for older adults nearing the end of life and whose religious beliefs form an important cornerstone of their lives (Upenieks, Reference Upenieks2021b). More generally, religion can act as an important framework to guide one’s life and can aid in coping with life’s challenges in a variety of ways, for instance by preserving a sense of meaning and significance or by maintaining one’s interpersonal religious support system (Pargament, Reference Pargament1997). The older adult years are prone to hold several unique challenges for individuals, such as the death of a spouse or parent, retirement, a change in one’s health, or – as mentioned above – thoughts about the end of one’s own life. As Pargament (Reference Pargament1997, p. 162) remarks, “The religious path is likely to be particularly compelling in boundary conditions when the limits of human resources come to the foreground.” Although religion may not hold the solution to all issues, it may nevertheless help many believers find comfort, support, and meaning, especially when it comes to dealing with the loss and changes that tend to accompany this later stage of life. However, if religious uncertainties are persistent, it may be experienced as a chronic struggle and be accompanied by worse mental health relative to those who have no doubts about their faith (Krause et al., Reference Krause, Ingersoll-Dayton, Ellison and Wulff1999). We propose the following hypotheses for our sample of older adults:

Hypothesis 1a. Consistently high religious doubt or increasing religious doubt will be associated with greater depression relative to those with consistently low doubt.

Hypothesis 1b. Consistently high religious doubt or increasing religious doubt will be associated with greater depression relative to those with decreasing doubt.

Coping with religious doubt: the role of pastoral support

The pastoral relationship might be a potentially attractive source of support in confronting problems of religious uncertainty. The role of the pastor is especially important as the most authoritative and prestigious position in the congregation, as pastors are viewed as an expert of religious knowledge (Stark and Bainbridge, Reference Stark and Bainbridge1987). Beyond their standing in the church community, clergy also tend to have long-term relationships with individuals and their families who regularly attend their church, which enable them to notice changes in demeanor that signal emotional distress (Weaver et al., Reference Weaver, Revilla and Koenig2002). Clergy have also been found to be effective in offering support and encouragement (Neighbors et al., Reference Neighbors, Musick and Williams1998), which may be all that is needed to help a person feel at ease during periods of spiritual uncertainty. Building on this point, one study found that receipt of more informal support from pastors is associated with more frequent use of positive coping responses (Krause et al., Reference Krause, Ellison, Shaw, Marcum and Boardman2001), but data for this study came from a nationwide survey of Presbyterians, limiting its generalizability. Another study found that emotional support from pastors is related to higher self-esteem in later life (Krause, Reference Krause2003), suggesting that this form of social support could enhance feelings of self-worth that underlie good mental health.

Moreover, pastors, more than any other church members, are supposed to embody the core elements of faith. This includes showing concern and empathy for those they serve and a deep commitment to assisting fellow church members (Krause, Reference Krause2008). Social support is typically more effective and healthpromoting when it arises in relationships characterized by a high degree of trust, commitment, and respect. When stressful life events happen to older people, pastors are turned to for emotional support, which in turn produces greater hope (Krause and Hayward, Reference Krause and Hayward2012). More specific to spiritual struggles, the official duties of clerics involve helping the faithful attain key religious goals, which could encompass resolving doubts. If older adults enter this social interaction with their pastor expecting them to be supportive, they may be able to either resolve, or, at the very least, manage the painful feelings of dissonance through spiritual guidance from a theologically trained professional. Therefore, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 2. The association between high religious doubt or increasing religious doubt and greater depression will be attenuated by higher levels of pastoral support.

Gender differences in the role of pastoral support in coping with religious doubt

Gender is one important dimension on which the relationships proposed thus far could vary, as we outlined below. On many indicators of religiosity, such as prayer frequency or religious service attendance, American women tend to be more religious than men (Schnabel, Reference Schnabel2015; Schnabel, Reference Schnabel2018). Women also tend to form a closer personal relationship with God and view God more positively compared to their male counterparts (Kent and Pieper, Reference Kent and Pieper2019; Schnabel, Reference Schnabel2018). These gender differences in religiosity are especially pronounced for older cohorts of Americans (Damianakis et al., Reference Damianakis, Coyle and Stergiou2020), as older women tend to hold their beliefs more strongly and practice their faith more frequently than their male counterparts. While there is no straightforward explanation for these gender differences in religiosity, some religious believers themselves may see women as “naturally” more religious than men due to religion aligning more closely with traditionally feminine-typed values (Ozorak, Reference Ozorak1996). Older women are also more tightly connected to their religious communities, tend to receive and provide more support in these communities, and participate more in Bible study or prayer groups than men (Krause, Reference Krause2008).

Despite a lively literature on gender and religiosity, few existing studies have focused on gender differences in religious doubt. Henrie and Patrick (Reference Henrie and Patrick2014) found that men tended to have greater religious doubt than women in later life, but this study did not examine whether holding such doubt had differential consequences for well-being. Krause and Wulff (Reference Krause and Wulff2004) found no significant moderation pattern between gender and religious doubt in predicting physical health. Altogether, this body of work on gender and religious doubt is relatively nascent, and only a few studies have explored whether there are gendered associations in the effect of religiosity on well-being. The conclusions can be described as equivocal at best: some studies in this vein reveal that women tend to score higher on most religious measures (Bonhag and Upenieks, Reference Bonhag and Upenieks2021; Jang and Johnson, Reference Jang and Johnson2005; Schnabel, Reference Schnabel2018; Sharp et al., Reference Sharp, Carr and Panger2016), but that men, according to some studies, derive greater psychosocial benefits from each “unit” of such religious variables (Krause et al., Reference Krause, Ellison and Marcum2002; Maselko and Kubzansky, Reference Maselko and Kubzansky2006; McFarland, Reference McFarland2010). These studies, however, have focused on the positive aspects of religiosity, such as integration into a religious community. When it comes to religious doubt, one of the “negative” aspects of religion, we might expect the mental health of women to be more impacted by prolonged or increasing religious doubt, given the centrality of religion/spirituality to their identity in later life.

Hypothesis 3. The association between high religious doubt or increasing religious doubt and greater depression will be stronger for women than men.

We also see reason to expect either women or men to benefit more from the pastoral relationship. With respect to the former possibility, women typically utilize the relational nature of religion more than men (Jung, Reference Jung2020), which could involve a supportive relationship with one’s pastor. Women’s greater involvement in spiritual groups, such as Bible study or prayer circles, could provide an avenue for them to share personal problems and get acquainted with their pastors (Wuthnow, Reference Wuthnow1994). Past research has also found women to have a greater likelihood of consulting the clergy for psychological help (Kane and Williams, Reference Kane and Williams2000; Neighbors et al., Reference Neighbors, Musick and Williams1998), suggesting that they may be more prone to seek help from the clergy to deal with spiritual struggles. Perceiving a sense of support from a pastor might be more important for women in the face of religious doubt, the resolution of which might be more important for their mental health.

However, men may more strongly benefit from pastoral support while experiencing religious/spiritual doubt. Although women have made great progress in terms of their access to seminaries and clergy positions since the 1970s (Chaves, Reference Chaves1996), the vast majority of clergy members still are men (Campbell-Reed, Reference Campbell-Reed2016). Within a religious community, though less involved, men tend to occupy more revered roles in the church hierarchy (e.g. usher and parish council) that afford them greater status than women (Heyer-Grey, Reference Heyer-Grey2000) compared to the cooking and cleaning tasks that women typically perform. Moreover, since religiosity has historically been an important marker of feminine moral standing (Baker and Smith, Reference Baker and Smith2015), and since being irreligious may still be seen as more deviant for women (Edgell et al., Reference Edgell, Frost and Stewart2017), women might be more hesitant toward seeking out help from clergy to address spiritual struggles that might expose their own inadequacies of faith.

The religious context has also been identified as a unique avenue that encourages men to ask for help, share feelings and concerns, and potentially also receive assistance in a way that is acceptable to them (Krause et al., Reference Krause, Ellison and Marcum2002). Since older women have extensive networks within and outside of church to which they can turn (Ajrouch et al., Reference Ajrouch, Blandon and Antonucci2005), men may gain more in terms of their mental health from the support received within a religious community. The church could serve a compensatory role for older men in improving mental health that was previously gained through formal employment (McFarland, Reference McFarland2010). If men consult a pastor, with the enhanced likelihood that the pastor will be of the same gender, they may experience less of a detrimental impact of religious doubts on their mental well-being compared to women. Thus, we propose the following two competing hypotheses on the differential effect of pastoral support in the relationship between religious doubt and mental health.

Hypothesis 4a. The association between high religious doubt or increasing religious doubt and greater depression will be attenuated by higher levels of pastoral support for women.

Hypothesis 4b. The association between high religious doubt or increasing religious doubt and greater depression will be attenuated by higher levels of pastoral support for men.

Methods

Sample

We employ the first and second waves of data, hereafter Wave 1 and Wave 2, from the Religion, Aging, and Health Survey, a nationally representative sample of US older adults interviewed in 2001 and 2004. At Wave 1, the study population was designated as noninstitutionalized, English-speaking White or Black household residents who were living in the contiguous United States and who were at least 65 years old. In addition, this study collected data from those who currently practice the Christian faith, those who used to be Christian but no longer practice any religion, and those who have never been associated with any religion during their lifetimes. Thus, the Religion, Aging, and Health Survey sample primarily (though not exclusively) draws from those who have a knowledge of practicing Christianity at any point in their lifetime.

At Wave 1 (2001), a total of 1500 participants completed face-to-face, in-home interviews. The response rate for the baseline interview was 62%. The interview rate for the second wave (2004) was 68.2%, meaning that of the initial 1500 survey participants, 1024 successfully participated in the Wave 2 survey.

Although 1024 respondents participated in both waves of the survey, not all respondents were included in the analyses presented here. Some cases were excluded because people must attend church on a regular basis in order to have an opportunity to interact with the pastor. Based on this, 374 participants did not complete the Wave 1 questions on pastoral support and 343 respondents were not asked questions about pastoral support at Wave 2 and hence were excluded from the analysis. Of the 1024 respondents followed up at Wave 2, 651 (230 men and 431 women) provided valid responses on all study variables. Listwise deletion was used to deal with all missing data, and since this comprised less than 5% of total cases.

Dependent variable: depressive symptoms

At both waves of the survey, an identical 8-Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) item measure of depressive symptoms was created (Radloff, Reference Radloff1977). Sample items were as follows: (1) “I could not shake off the blues even with the help of my family and friends,” (2) “I felt depressed,” and (3) “I felt that everything I did was an effort.” Responses were coded according to the following scheme, where higher scores indicate higher depressive symptoms: 1 = “Rarely or none of the time” to 4 = “Most or all of the time” (α = 0.87 at Wave 1, α = 0.86 at Wave 2).

We examined the potential for skewness on our outcome variable. The skewness of the depressive symptoms index was 1.42 at Wave 1 (Kurtosis = 4.79), and 1.67 at Wave 2 (Kurtosis = 5.61). While depression was positively skewed (toward lower values), we retained this variable in its initial form in keeping with prior research conducted with the Religion, Aging, and Health Survey (e.g. Krause, Reference Krause2009). We note that the results (available upon request) are substantively similar if depression is log-transformed prior to analyses.

Focal independent variables

Changes in religious doubt

An identical index of religious doubt was constructed at Waves 1 and 2 of the study, based on an average of the following five items: (1) “How often do you have doubts about your religious or spiritual beliefs?”, (2) “How often do you have doubts about the things you’ve been taught in church?”, (3) “How often do you doubt whether solutions to your problems can be found in the Bible?”, (4) “How often do you doubt whether your prayers make a difference in your life?”, and (5) “How often do you doubt that God is directly involved in your life?” Response options for each question were coded 1 = “Never,” 2 = “Once in a while,” 3 = “Fairly often,” and 4 = “Very often,” where higher scores indicate greater uncertainty about one’s faith (α = 0.83 at Wave 1; α = 0.81 at Wave 2).

Since the focus in this study centers on changes in religious doubt over time, we created a four-category variable modeling transitions in respondent scores between Waves 1 and 2. To do so, we followed the exact procedure employed by previous research with the Religion, Aging, and Health Survey (Krause and Ellison, Reference Krause and Ellison2009; Upenieks, Reference Upenieks2021b). Individuals with stably low doubt reported no change in their religious doubt scores across the two waves of the study and had scores of 1 (no doubts) at both time points. Individuals with stable high religious doubt did not change in their religious doubt scores over time but had scores greater than 1 on the doubt scale at both time points. The third category are those that increase in religious doubt over time, that is, individuals who had higher doubt scores at Wave 2 than at Wave 1. Finally, the fourth category of change in religious doubt is decreasing doubt, categorizing individuals who had lower scores for religious doubt at Wave 2 compared to Wave 1.

Pastoral support

Seven items were asked of respondents to gauge pastoral support, which was assessed at Wave 2 of the survey. These items have been validated in previous studies (see Krause, Reference Krause2002). Sample items are as follows: (1) “How often does your minister/pastor/priest speak with you privately about your problems and concerns?” and (2) “When talking with your minister/pastor/priest on an individual basis, how often does he/she express interest and concern in your well-being?” Responses were coded as 1 = “Never,” 2 = “Once in a while,” 3 = “Fairly often,” and 4 = “Very often” and averaged into a scale, where higher scores indicate stronger perceptions of pastoral support (α = 0.86).

Covariates

A number of covariates, measured during Wave 1, were included across analytic models to rule out the possibility of confounding. Race is coded as a binary variable (1 = Black, 0 = White). Gender was coded as 1 = women and 0 = men. Age was measured in years. Marital status contrasted married respondents (1) versus all other relationship forms (0). Educational attainment contrasts those with a college degree (1) versus all else (0).

We also adjust for self-reported religious attendance, comparing those who attend weekly (1) with less frequent attendees (0), which may offer a barometer of overall personal religious commitment and holds a strong association with mental health (VanderWeele, Reference VanderWeele, Peteet and Balboni2017). Regular attenders are also more likely to know clergy members on a personal basis (Ellison et al., Reference Ellison, Vaaler, Flannelly and Weaver2006). Finally, we also adjust for respondents’ frequency of daily prayer, contrasting those praying daily (representing 30% of the sample) with all other prayer frequencies.

Plan of analysis

Lagged dependent variable (LDV) models using ordinary least squares regression and robust standard errors were estimated to predict changes in depression by the key independent variable of transitions in religious doubt, pastoral support, and all other study covariates.

We conducted analyses on separate samples of 231 men and 421 women (see Bonhag and Upenieks, Reference Bonhag and Upenieks2021 for a similar approach). Given the discrepancies in sample size between strata, we only draw conclusions on whether the hypothesized associations are present (e.g. statistically significant) for men and/or women.

Results

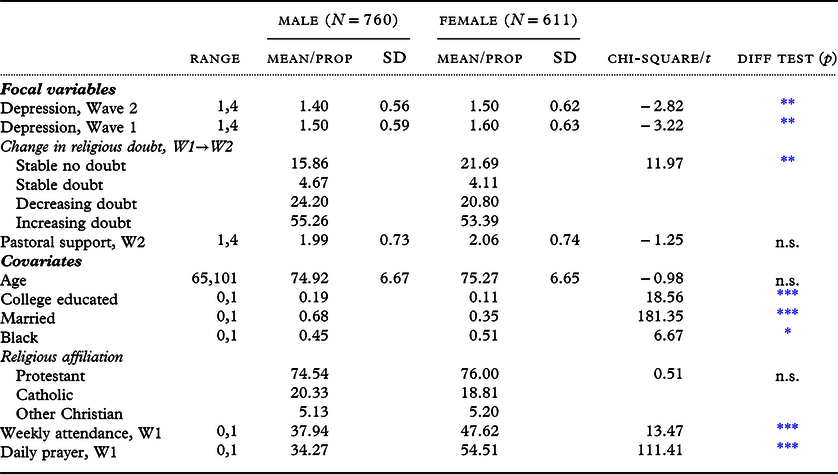

Table 1 shows descriptive statistics for the total sample and stratified by gender. Chi-square/t-statistics are shown which test for differences in proportions or means across the male and female sample. Briefly, we note that women have higher levels of depression at both waves than men but report fewer religious doubts and perceive greater pastoral support.

Table 1. Sample descriptive statistics, Religion, Aging, and Health Survey, stratified by gender

n.s. = Not significant. Standard deviations are omitted for categorical variables.

* p < .05.

** p < .01.

*** p < .001.

Multivariable regression results

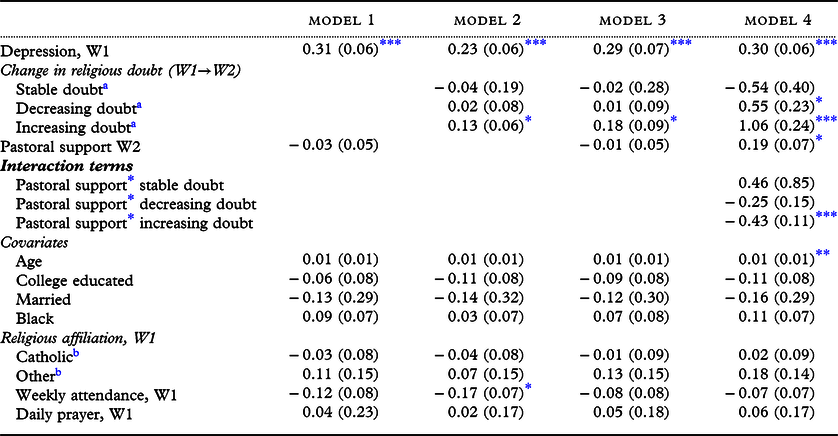

Table 2 shows regression results predicting depression for men, and Table 3 for women.

Table 2. Depression (Wave 2) regressed on changes in religious doubt and pastoral support, LDV models. 2001–2004 Religion, Health, and Aging Survey (male sample, N = 230)

Unstandardized coefficients are shown. Robust standard errors are shown in brackets.

a Compared to stable no doubt.

b Compared to protestants.

* p < 0.05.

** p < 0.01.

*** p < 0.001.

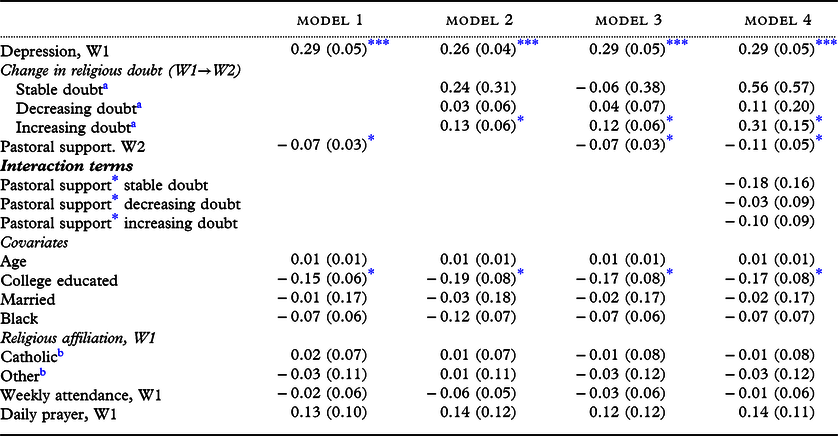

Table 3. Depression (Wave 2) regressed on changes in religious doubt and pastoral support, LDV models. 2001–2004 Religion, Health, and Aging Survey (female sample, N = 421)

Unstandardized coefficients are shown. Robust standard errors are shown in brackets.

a Compared to stable no doubt.

b Compared to protestant.

* p < 0.05.

**p < 0.01.

*** p < 0.001.

Model 1 of Tables 2 and 3 assess the baseline relationship between pastoral support and mental health. Pastoral support at Wave 2 was not significantly associated with depression for men, but it was negatively associated with depression for women (b = −0.07, p < 0.05), such that women reporting higher pastoral support had lower depression, net of all covariates except religious doubt, which is tested separately in Model 2. This represents just over 1/10th of a standard deviation in Wave 2 depression scores.

Model 2 of Tables 2 and 3 similarly assess the relationship between changes in religious doubt and depression, net of all demographic and religious characteristics except for pastoral support. For the male sample, relative to those with consistently no doubt, older men who increased their religious doubt over time reported higher depression (b = 0.13, p < 0.05), representing just under ¼ of a standard deviation in Wave 2 depression scores for men. Men with stable high doubt did not have levels of depression that differed significantly from those with no doubt. Ancillary analyses also revealed that men with increasing doubt have significantly higher depression than men with decreasing doubt. Therefore, we see partial support for Hypotheses 1a and 1b when it comes to the increasing doubt category.

Moving to the female sample in Table 3, a similar pattern emerges. Again, we see that only the increasing doubt group had significantly higher depression than the stable no doubt group (b = 0.13, p < 0.05), corresponding to approximately 1/5th of a standard deviation higher depression scores for this group. Those with increasing doubt also have higher depression than those with decreasing doubt. As for the male sample, we did not see differences in depression emerge for those with stable high doubt compared to no doubt. Therefore, in the female sample, Hypotheses 1a and 1b receive partial support.

Model 3 of Tables 2 and 3 simultaneously consider changes in religious doubt and pastoral support without yet assessing their multiplicative relationship. The results from Models 1 and 2 remain intact; indeed, increasing doubt still remained significantly associated with greater depression in both the male and female sample (b = 0.18, p < 0.05, and b = 0.12, p < 0.05, respectively). We therefore observe no support for Hypothesis 3. For women only, greater pastoral support remains negatively associated with depression (b = −0.07, p < 0.05), again corresponding to about 1/10th of a standard deviation in Wave 2 depression scores.

Finally, Model 4 of Tables 2 and 3 serve as a test of Hypothesis 4, whether pastoral support attenuates the relationship between stable high/increasing religious doubt and depression and whether it does so differently by gender. For the female sample, we find no evidence of a statistically significant interaction term between change in religious doubt and pastoral support. However, we observe a negative and significant interaction coefficient between pastoral support and increasing doubt (b = −0.43, p < 0.001) in the male sample. Since increasing religious doubt has a positive association with depression across models and again in Model 4 (b = 1.06, p < 0.001), this negative interaction coefficient suggests that for men, greater pastoral support weakens the association between increasing religious doubt and depression.

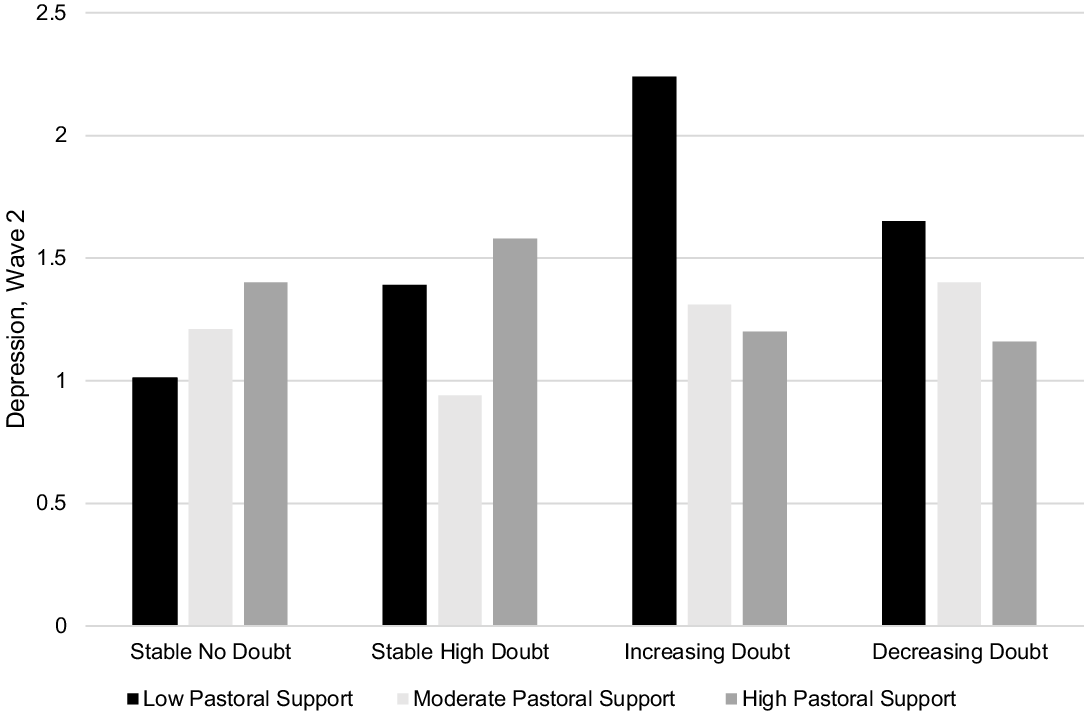

In Figure 1, we plot predicted depression scores for each of the four categories of religious doubt at three levels of pastoral support: low pastoral support (1 standard deviation below the sample mean), moderate pastoral support (at the sample mean), and high pastoral support (1 standard deviation above the sample mean).

Figure 1. Change in religious doubt and depression: the moderating role of pastoral support, male sample.

As shown clearly in Figure 1 in the third set of bars, older men with increasing religious doubt who had high pastoral support reported fairly low depression scores (1.20) compared to their counterparts with increasing doubt who had low pastoral support (average depression score = 2.24). For all other categories of religious doubt, we see that neither low, moderate, or high levels of religious doubt significantly modified the relationship between that level of doubt and depression. Therefore, Hypothesis 4b (but not 4a) is supported: pastoral support mitigated the relationship between increasing religious doubt and depression for men.

Discussion

Drawing on longitudinal data from a sample of older adults, our study revealed several key findings regarding the role of the pastor for older adults holding varying levels of religious doubt. Religious clergy are the most common source sought out by older adults for dealing with emotional problems (Pickard et al., Reference Pickard, Inoue, Chadiha and Johnson2011; Pickard and Tang, Reference Pickard and Tang2009), but no previous study has explored whether pastoral support can be helpful for dealing with struggles in the religious/spiritual domain. Given the shortage of mental health professionals suited to deal with an aging population in the United States, religious clergy are an important (yet understudied) resource for this group to access.

Our first key finding was that increases in doubts about one’s faith over time are associated with greater depression for both men and women. This extends previous research examining the consequences of religious doubt for mental health in later life by examining how doubts change over time. We find it striking that relative to older adults reporting consistently high doubts about their faith, it was only those individuals with increasing doubts that fared worse in their mental well-being. That holding consistently high doubt over time did not portend worse mental health might suggest that older adults have either grown accustomed to this doubt and/or are managing it over time, perhaps reflecting the wisdom gained through years of experience to quell the distress these doubts may cause (Baltes and Staudinger, Reference Baltes and Staudinger2000; Galek et al., Reference Galek, Krause, Ellison, Kudler and Flannelly2007). Indeed, aging and maturation may foster personal strength that allows older adults to better grapple with some degree of uncertainty or ambiguity. Altogether, for both older men and women, it was the more sudden upticks in doubt from a state of relative certainty to uncertainty that seemed to put older adults at a heightened depression risk.

As a second key finding, we observed that for older men the relationship between increasing religious doubt and depression was weaker for those who reported greater levels of pastoral support. This may be reflective of several patterns within broader religious communities: first, pastors are more likely to be men than women, by almost a 4 to 1 ratio in the United States (Campbell-Reed, Reference Campbell-Reed2016). Males might therefore feel more inclined to discuss intimate issues – such as doubts or struggles with one’s faith – with those they share a gender with. Women may feel less comfortable displaying this level of vulnerability and might also fear they will be negatively judged by a pastor for harboring these doubts about faith, especially since their gender may make their doubts be perceived as more deviant (Baker and Smith, Reference Baker and Smith2015; Edgell et al., Reference Edgell, Frost and Stewart2017). Additionally, some more conservative denominations stress the role of men as spiritual leaders within the home (e.g. Gallagher and Smith, Reference Gallagher and Smith1999). For some men, this could increase their likelihood of seeking out pastoral care when they see their faith dwindle so as to maintain their identity in their families and religious communities.

The religious context might also be an important avenue through which men can ask for help and share their feelings and concerns in a way that they deem acceptable (Krause et al., Reference Krause, Ellison and Marcum2002). Since men tend to occupy higher status roles within a religious congregation (Hoffmann and Bartkowski, Reference Hoffmann and Bartkowski2008; McFarland, Reference McFarland2010), they may be more apt to turn to religious communities, and especially their pastor, for support. This is likely to be an important compensatory mechanism for the support deficits they face in the secular world, especially after retirement.

We would be remiss if we failed to note that pastoral support had a significant main effect and was associated with lower depression among women. This is consistent with past research showing that women may benefit more from religious involvement and the resources embedded within religious communities than men (Bonhag and Upenieks, Reference Bonhag and Upenieks2021; Jang and Johnson, Reference Jang and Johnson2005; Sharp et al., Reference Sharp, Carr and Panger2016). Irrespective of religious doubt, women who perceived greater support from their pastors did report better mental health. Thus, even though there was not a moderation pattern for pastoral support for older women facing spiritual struggles, pastoral support did indeed work in the expected direction and correlated with lower depression. This suggests that pastoral support still provides a boost for mental health for older women, whose religiosity is a salient part of their identity (Damianakis et al., Reference Damianakis, Coyle and Stergiou2020). When it comes to spiritual struggles, though a speculative interpretation, it may be that women have other coping methods to deal with these struggles beyond pastoral support, such as larger social networks outside of church or a deeper, more matured faith that may not ache for spiritual expertise.

Limitations and future directions

We acknowledge several limitations of the current study. First, we note that the effect sizes we observed in our focal relationship between changes in religious doubt and depression were small (ranging from 1/10th to ¼ of a standard deviation difference in Wave 2 depression scores) and therefore not likely to be clinically meaningful for diagnosing mental disorders. This is not unexpected: as Cohen (Reference Cohen2013, pp. 11–12) notes, “many relationships pursued in ‘soft’ behavioral science are of this order of magnitude [small].” We do, however, show for the first time that a supportive pastoral relationship mitigates the adverse consequences of increases in religious doubt for men in a sample of community-dwelling, noninstitutionalized older adults, making our findings of potential theoretical interest.

Second, we acknowledge that only one way of coping with religious doubt was assessed in this study: support from a pastor. We also only had a very general measure of pastoral support, not a more fine-grained measure of whether religious/spiritual matters or uncertainty of faith was discussed with pastors.

Third, it would be helpful to have more detailed information on the nature of pastor/congregant interactions, such as whether the person was formally counseled on their spiritual struggles, or whether these were mentioned in more spontaneous and informal encounters before or after church gatherings. We also lacked information on the gender of one’s pastor, so we could not assess whether gender concordant matches between gender and pastoral support might have been more effective in reducing the mental health risks associated with greater doubt.

Fourth, the questions on pastoral support asked in the Religion, Health, and Aging Survey were not administered to those who never attended church, or who only go to worship services a few times a year. Yet, it is possible for older people to have contact with the clergy even if they do not go to church. For example, the clergy often maintain contact with older adults who are too ill to go to church, or who find themselves unable to attend because of conflicting caregiving roles. These individuals, too, may experience religious/spiritual doubt, and it would be interesting to see if our findings replicate when the sample is broadened to include non-frequent attenders. In addition, future studies should examine whether the trends we observe here can also be applied to non-Christian believers and to other cultural contexts. Research has shown that the gender gap in religiosity shows considerable variation across religious groups and cultural backgrounds (e.g. Schnabel, Reference Schnabel2015; Sullins, Reference Sullins2006).

Finally, even though longitudinal data were utilized, older adults with higher depression may encounter less interaction with the clergy due to a diminished presence at worship gatherings. These individuals may also be at a higher risk of perceiving interactions with the clergy as negative, which could undermine reports of how supportive they believe their pastor is. Altogether, more waves of longitudinal data are needed to sort out this causal mechanism.

We hope the findings of our study are extended and applied to other sociodemographic groups beyond gender, such as race. African American clergy are a significant mental health service provider among African Americans given their historic mistrust of the medical system (Chatters et al., Reference Chatters, Mattis, Woodward, Taylor, Neighbors and Grayman2011; Young, et al., Reference Young, Griffith and Williams2003), with clergy often serving as gatekeepers to other mental health resources (VanderWaal et al., Reference VanderWaal, Hernandez and Sandman2012). African Americans have much higher levels of religious involvement than the general population (Chatters et al., Reference Chatters, Taylor, Bullard and Jackson2009), and religious doubt tends to be less strongly associated with their mental health compared to Whites (Krause, Reference Krause2003). It would be informative to know how responses to doubt vary with supportive relationships with a religious clergy member for African Americans, and perhaps whether there are gender differences in how this mental health-protective process unfolds.

Conclusion

Within the context of social relationships in later life, results from the current study suggest the importance of efforts to better understand how clergy provide pastoral care to support elder congregant’s mental health, especially during periods of spiritual struggles. Identifying difficulties in people’s lives that have their basis in religious/spiritual uncertainties could help pastors provide both formal pastoral counseling and informal sources of support that may help to reduce the mental health risks associated with these doubts. Our findings show that clergy support may be particularly useful for older men, who, devoid of strong bases of social support in the secular world, might be prone to seek out pastoral help. This finding also suggests that perhaps greater efforts are needed to encourage women to seek out pastoral help when experiencing doubts about faith, ensuring an inviting, comfortable, and safe environment for them to disclose their issues.

Conflict of interest

None.