Immersion in the particular proved, as usual, essential for the catching of anything general.

[T]he bulk of the literature presently recommended for policy decisions … cannot be used to identify “what works here”. And this is not because it may fail to deliver in some particular cases [; it] is not because its advice fails to deliver what it can be expected to deliver … The failing is rather that it is not designed to deliver the bulk of the key facts required to conclude that it will work here.

5.1 Introduction: In Search of ‘Key Facts’

Over the last two decades, social scientists across the disciplines have worked tirelessly to enhance the precision of claims made about the impact of development projects, seeking to formally verify ‘what works’ as part of a broader campaign for ‘evidence-based policy-making’ conducted on the basis of ‘rigorous evaluations’.Footnote 3 In an age of heightened public scrutiny of aid budgets and policy effectiveness, and of rising calls by development agencies themselves for greater accountability and transparency, it was deemed no longer acceptable to claim success for a project if selected beneficiaries or officials merely expressed satisfaction, if necessary administrative requirements had been upheld, or if large sums had been dispersed without undue controversy. For their part, researchers seeking publication in elite empirical journals, where the primary criteria for acceptance was (and remains) the integrity of one’s ‘identification strategy’ – that is, the methods deployed to verify a causal relationship – faced powerful incentives to actively promote not merely more and better impact evaluations, but methods, such as randomized controlled trials (RCTs) or quasi-experimental designs (QEDs), squarely focused on isolating the singular effects of particular variables. Moreover, by claiming to be adopting (or at least approximating) the ‘gold standard’ methodological procedures of biomedical science, champions of RCTs in particular could impute to themselves the moral and epistemological high ground as ‘the white lab coat guys’ of development research.

The heightened focus on RCTs as the privileged basis on which to impute causal claims in development research and project evaluation has been subjected to increasingly trenchant critique,Footnote 4 but for present purposes my objective is not to rehearse, summarize, or contribute to these debates per se; it is, rather, to assert that these preoccupations have drained attention from an equally important issue, namely our basis for generalizing any claims about impact from different types of interventions across time, contexts, groups, and scales of operation. If identification and causality are debates about ‘internal validity’, then generalization and extrapolation are concerns about ‘external validity’.Footnote 5 It surely matters for the latter that we first have a good handle on the former, but even the cleanest estimation of a given project’s impact does not axiomatically provide warrant for confidently inferring that similar results can be expected if that project is scaled up or replicated elsewhere.Footnote 6 Yet too often this is precisely what happens: having expended enormous effort and resources in procuring a clean estimate of a project’s impact, and having successfully defended the finding under vigorous questioning at professional seminars and review sessions, the standards for inferring that similar results can be expected elsewhere or when ‘scaled up’ suddenly drop away markedly. The ‘rigorous result’, if ‘significantly positive’, slips all too quickly into implicit or explicit claims that ‘we know’ the intervention ‘works’ (even perhaps assuming the status of a veritable ‘best practice’), the very ‘rigor’ of ‘the evidence’ invoked to promote or defend the project’s introduction into a novel (perhaps highly uncertain) context. In short, because an intervention demonstrably worked ‘there’, we all too often and too confidently presume it will also work ‘here’.

Even if concerns about the weak external validity of RCTs/QEDs – or, for that matter, any methodology – of development interventions are acknowledged by most researchers, decision-makers still lack a usable framework by which to engage in the vexing deliberations surrounding whether and when it is at least plausible to infer that a given impact result (positive or negative) ‘there’ is likely to obtain ‘here’. Equally importantly, we lack a coherent system-level imperative requiring decision-makers to take these concerns seriously, not only so that we avoid intractable, nonresolvable debates about the effectiveness of entire portfolios of activity (‘community health’, ‘justice reform’) or abstractions (‘do women’s empowerment programs work?’Footnote 7), but, more positively and constructively, so that we can enter into context-specific discussions about the relative merits of (and priority that should be accorded to) roads, irrigation, cash transfers, immunization, legal reform, etc., with some degree of grounded confidence – that is, on the basis of appropriate metrics, theory, experience, and (as we shall see) trajectories and theories of change.

Though the external validity problem is widespread and vastly consequential for lives, resources, and careers, this chapter’s modest goal is not to provide a “tool kit” for “resolving it” but rather to promote a broader conversation about how external validity concerns might be more adequately addressed in the practice of development. (Given that the bar, at present, is very low, facilitating any such conversations will be a nontrivial achievement.) As such, this chapter presents ideas to think with. Assessing the extent to which empirical claims about a given project’s impact can be generalized is only partly a technical endeavor; it is equally a political, organizational, and philosophical issue, and as such usable and legitimate responses will inherently require extended deliberation in each instance. To this end, the chapter is structured in five sections. Following this introduction, Section 5.2 provides a general summary of selected contributions to the issue of external validity from a range of disciplines and fields. Section 5.3 outlines three domains of inquiry (‘causal density’, ‘implementation capabilities’, ‘reasoned expectations’) that, for present purposes, constitute the key elements of an applied framework for assessing the external validity of development interventions generally, and ‘complex’ projects in particular. Section 5.4 considers the role analytic case studies can play in responding constructively to these concerns. Section 5.5 concludes.

5.2 External Validity Concerns Across the Disciplines: A Short Tour

Development professionals are far from the only social scientists, or philosophers or scientists of any kind, who are confronting the challenges posed by external validity concerns.Footnote 8 Consider first the field of psychology. It is safe to say that many readers of this chapter, in their undergraduate days, participated in various psychology research studies. The general purpose of those studies, of course, was (and continues to be) to test various hypotheses about how and when individuals engage in strategic decision-making, display prejudice toward certain groups, perceive ambiguous stimuli, respond to peer pressure, and the like. But how generalizable are these findings? In a detailed and fascinating paper, Reference Henrich, Heine and NorenzayanHenrich, Heine, and Norenzayan (2010a) reviewed hundreds of such studies, most of which had been conducted on college students in North American and European universities. Despite the limited geographical scope of this sample, most of the studies they reviewed readily inferred (implicitly or explicitly) that their findings were indicative of ‘humanity’ or reflected something fundamental about ‘human nature’. Subjecting these broad claims of generalizability to critical scrutiny (for example, by examining the results from studies where particular ‘games’ and experiments had been applied to populations elsewhere in the world), Henrich et al. concluded that the participants in the original psychological studies were in fact rather WEIRD – western, educated, industrialized, rich and democratic – since few of the findings of the original studies could be replicated in “non-WEIRD” contexts (see also Reference Henrich, Heine and NorenzayanHenrich, Heine, and Norenzayan 2010b).

Consider next the field of biomedicine, whose methods development researchers are so often invoked to adopt. In the early stages of designing a new pharmaceutical drug, it is common to test prototypes on mice, doing so on the presumption that mouse physiology is sufficiently close to human physiology to enable results for the former to be inferred for the latter. Indeed, over the last several decades a particular mouse – known as ‘Black 6’ – has been genetically engineered so that biomedical researchers around the world are able to work on mice that are literally genetically identical. This sounds ideal for inferring causal results: biomedical researchers in Norway and New Zealand know they are effectively working on clones, and thus can accurately compare findings. Except that it turns out that in certain key respects mouse physiology is different enough from human physiology to have compromised “years and billions of dollars” (Reference KolataKolata 2013: A19) of biomedical research on drugs for treating burns, trauma, and sepsis, as reported in a New York Times summary of a major (thirty-nine coauthors) paper published in the prestigious Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (see Reference Seok, Warren and CuencaSeok et al. 2013). In an award-winning science journalism article, Reference EngberEngber (2011) summarized research showing that Black 6 was not even representative of mice – indeed, upon closer inspection, Black 6 turns out to be “a teenaged, alcoholic couch potato with a weakened immune system, and he might be a little hard of hearing.” An earlier study published in The Lancet (Reference RothwellRothwell 2005) reviewed nearly 200 RCTs in biomedical and clinical research in search of answers to the important question “To whom do the results of this trial apply?” and concluded, rather ominously, that the methodological quality of many of the published studies was such that even their internal validity, let alone their external validity, was questionable. Needless to say, it is more than a little disquieting to learn that even the people who do actually wear white lab coats for a living have their own serious struggles with external validity.Footnote 9

Consider next a wonderful simulation paper in health research, which explores the efficacy of two different strategies for identifying the optimal solution to a given clinical problem, a process the authors refer to as “searching the fitness landscape” (Reference Eppstein, Horbar, Buzas and KauffmanEppstein et al. 2012).Footnote 10 Strategy one entails adopting a verified ‘best practice’ solution: you attempt to solve the problem, in effect, by doing what experts elsewhere have determined is the best approach. Strategy two effectively entails making it up as you go along: you work with others and learn from collective experience to iterate your way to a customized ‘best fit’Footnote 11 solution in response to the particular circumstances you encounter. The problem these two strategies confront is then itself varied. Initially the problem is quite straight forward, exhibiting what is called a ‘smooth fitness landscape’ – think of being asked to climb an Egyptian pyramid, with its familiar symmetrical sides. Over time the problem being confronted is made more complex, its fitness landscape becoming increasingly rugged – think of being asked to ascend a steep mountain, with craggy, idiosyncratic features. Which strategy is best for which problem? It turns out the ‘best practice’ approach is best – but only as long as you are climbing a pyramid (i.e., facing a problem with a smooth fitness landscape). As soon as you tweak the fitness landscape just a little, however, making it even slightly ‘rugged’, the efficacy of ‘best practice’ solutions fall away precipitously, and the ‘best fit’ approach surges to the lead. One can over-interpret these results, of course, but given the powerful imperatives in development to identify “best practices” (as verified, preferably, by an RCT/QED) and replicate “what works,” it is worth pondering the implications of the fact that the ‘fitness landscapes’ we face in development are probably far more likely to be rugged than smooth, and that compelling experimental evidence (supporting a long tradition in the history of science) now suggests that promulgating best practice solutions is a demonstrably inferior strategy for resolving them.

Two final studies demonstrate the crucial importance of implementation and context for understanding external validity concerns in development. Reference Bold, Kimenyi, Mwabu, Ng’ang’a and SandefurBold et al. (2013) deploy the novel technique of subjecting RCT results themselves to an RCT test of their generalizability using different types of implementing agencies. Earlier studies from India (e.g., Reference Banerjee, Cole, Duflo and LindenBanerjee et al. 2007, Reference Duflo, Dupas and KremerDuflo, Dupas, and Kremer 2012, Reference Muralidharan and SundararamanMuralidharan and Sundararaman 2010) famously found that, on the basis of an RCT, contract teachers were demonstrably ‘better’ (i.e., both more effective and less costly) than regular teachers in terms of helping children to learn. A similar result had been found in Kenya, but as with the India finding, the implementing agent was an NGO. Bold et al. took essentially an identical project design but deployed an evaluation procedure in which 192 schools in Kenya were randomly allocated either to a control group, an NGO-implemented group, or a Ministry of Education-implemented group. The findings were highly diverse: the NGO-implemented group did quite well relative to the control group (as expected), but the Ministry of Education group actually performed worse than the control group. In short, the impact of “the project” was a function not only of its design but, crucially and inextricably, of its implementation and context. As the authors aptly conclude, “the effects of this intervention appear highly fragile to the involvement of carefully-selected non-governmental organizations. Ongoing initiatives to produce a fixed, evidence-based menu of effective development interventions will be potentially misleading if interventions are defined at the school, clinic, or village level without reference to their institutional context” (Reference Bold, Kimenyi, Mwabu, Ng’ang’a and SandefurBold et al. 2013: 7).Footnote 12

A similar conclusion, this time with implications for the basis on which policy interventions might be ‘scaled up’, emerges from an evaluation of a small business registration program in Brazil (see Reference Bruhn and McKenzieBruhn and McKenzie 2013). Intuition and some previous research suggests that a barrier to growth faced by small unregistered firms is that their very informality denies them access to legal protection and financial resources; if ways could be found to lower the barriers to registration – for example, by reducing fees, expanding information campaigns promoting the virtues of registration, etc. – many otherwise unregistered firms would surely avail themselves of the opportunity to register, with both the firms themselves and the economy more generally enjoying the fruits. This was the basis on which the state of Minas Gerais in Brazil sought to expand a business start-up simplification program into rural areas: a pilot program that had been reasonably successful in urban areas now sought to ‘scale up’ into more rural and remote districts, the initial impacts extrapolated by its promoters to the new levels and places of operation. At face value, this was an entirely sensible expectation, one that could also be justified on intrinsic grounds: one could argue that all small firms, irrespective of location, should as a matter of principle be able to register. Deploying an innovative evaluation strategy centered on the use of existing administrative data, Bruhn and McKenzie found that despite faithful implementation the effects of the expanded program on firm registration were net negative; isolated villagers, it seems, were so deeply wary of the state that heightened information campaigns on the virtues of small business registration only confirmed their suspicions that the government’s real purposes were probably sinister and predatory, and so even those owners that once might have registered their business now did not. If only with the benefit of hindsight, ‘what worked’ in one place and at one scale of operation was clearly inadequate grounds for inferring what could be expected elsewhere at a much larger one.Footnote 13

In this brief tourFootnote 14 of fields ranging from psychology, biomedicine, and clinical health to education, regulation, and criminology we have compelling empirical evidence that inferring external validity to given empirical results – that is, generalizing findings from one group, place, implementation modality, or scale of operation to another – is a highly fraught exercise. As the opening epigraph wisely intones, evidence supporting claims of a significant impact ‘there’, even (or especially) when that evidence is a product of a putatively rigorous research design, does not “deliver the bulk of the key facts required to conclude that it will work here.” What might those missing “key facts” be? Clearly some interventions can be scaled and replicated more readily than others, so how might the content of those “facts” vary between different types of interventions?

In the next section, I propose three categories of issues that can be used to interrogate given development interventions and the basis of the claims made regarding their effectiveness; I argue that these categories can yield potentially useful and usable “key facts” to better inform pragmatic decision-making regarding the likelihood that results obtained ‘there’ can be expected ‘here’. In Section 2.4 I argue that analytic case studies can be a particularly fruitful empirical resource informing the tone and terms of this interrogation, especially for complex development interventions. I posit that this fruitfulness rises in proportion to the ‘complexity’ of the intervention: the higher the complexity, the more salient (even necessary) inputs from analytic case studies become as contributors to the decision-making process.

5.3 Elements of an Applied Framework for Identifying ‘Key Facts’

Heightened sensitivity to external validity concerns does not axiomatically solve the problem of how exactly to make difficult decisions regarding whether, when, and how to replicate and/or scale up (or, for that matter, cancel) interventions on the basis of an initial empirical result, a challenge that becomes incrementally harder as interventions themselves, or constituent elements of them, become more ‘complex’ (defined below). Even if we have eminently reasonable grounds for accepting a claim about a given project’s impact ‘there’ (with ‘that group’, at this ‘size’, implemented by ‘these people’ using ‘this approach’), under what conditions can we confidently infer that the project will generate similar results ‘here’ (or with ‘this group’, or if it is ‘scaled up’, or if implemented by ‘those people’ deploying ‘that approach’)? We surely need firmer analytical foundations on which to engage in these deliberations; in short, we need more and better “key facts,” and a corresponding theoretical framework able to both generate and accurately interpret those facts.

One could plausibly defend a number of domains in which such “key facts” might reside, but for present purposes I focus on three:Footnote 15 ‘causal density’ (the extent to which an intervention or its constituent elements are ‘complex’); ‘implementation capability’ (the extent to which a designated organizational entity in the new context can in fact faithfully implement the type of intervention under consideration); and ‘reasoned expectations’ (the extent to which claims about actual or potential impact are understood within the context of a grounded theory of change specifying what can reasonably be expected to be achieved by when). I address each of these domains in turn.

5.3.1 Causal Density

Conducting even the most routine development intervention is difficult, in the sense that considerable effort needs to be expended at all stages over long periods of time, and that doing so may entail carrying out duties in places that are dangerous (‘fragile states’) or require navigating morally wrenching situations (dealing with overt corruption, watching children die).Footnote 16 If there is no such thing as a ‘simple’ development project, we need at least a framework for distinguishing between different types and degrees of complexity, since this has a major bearing on the likelihood that a project (indeed, a system or intervention of any kind) will function in predictable ways, which in turn shapes the probability that impact claims associated with it can be generalized.

One entry point into analytical discussions of complexity is of course ‘complexity theory’, a field to which social scientists engaging with policy issues have increasingly begun to contribute and learn,Footnote 17 but for present purposes I will create some basic distinctions using the concept of ‘causal density’ (see Reference ManziManzi 2012). An entity with low causal density is one whose constituent elements interact in precisely predictable ways: a wrist watch, for example, may be a marvel of craftsmanship and micro-engineering, but its genius actually lies in its relative ‘simplicity’: in the finest watches, the cogs comprising the internal mechanism are connected with such a degree of precision that they keep near perfect time over many years, but this is possible because every single aspect of the process is perfectly understood. Development interventions (or aspects of interventionsFootnote 18) with low causal density are ideally suited for assessment via techniques such as RCTs because it is reasonable to expect that the impact of a particular element can be isolated and empirically discerned, and the corresponding adjustments or policy decisions made. Indeed, the most celebrated RCTs in the development literature – assessing deworming pills, textbooks, malaria nets, classroom size, cameras in classrooms to reduce teacher absenteeism – have largely been undertaken with interventions (or aspect of interventions) with relatively low causal density. If we are even close to reaching “proof of concept” with interventions such as immunization and iodized salt it is largely because the underlying physiology and biochemistry has come to be perfectly understood, and their implementation (while still challenging logistically) requires relatively basic, routinized behavior on the part of front-line agents (see Reference Pritchett and WoolcockPritchett and Woolcock 2004). In short, attaining “proof of concept” means the proverbial ‘black box’ has essentially been eliminated – everything going on inside the ‘box’ (i.e., the dynamics behind every mechanism connecting inputs and outcomes) is known or knowable.Footnote 19

Entities with high causal density, on the other hand, are characterized by high uncertainty, which is a function of the numerous pathways and feedback loops connecting inputs, actions, and outcomes, the entity’s openness to exogenous influences, and the capacity of constituent elements (most notably people) to exercise discretion (i.e., to act independently of or in accordance with rules, expectations, precedent, passions, professional norms, or self-interest). Parenting is perhaps the most familiar example of a high causal density activity. Humans have literally been raising children forever, but as every parent knows, there are often many factors (known and unknown) intervening between their actions and the behavior of their offspring, who are intensely subject to peer pressure and willfully act in accordance with their own (often fluctuating, seemingly quixotic) wishes. Despite millions of years and billions of ‘trials’, we have not produced anything remotely like “proof of concept” with parenting, even if there are certainly useful rules of thumb. Each generation produces its own bestselling ‘manual’ based on what it regards as the prevailing scientific and collective wisdom, but even if a given parent dutifully internalizes and enacts the latest manual’s every word it is far from certain that his/her child will emerge as a minimally functional and independent young adult; conversely, a parent may know nothing of the book or unwittingly engage in seemingly contrarian practices and yet happily preside over the emergence of a perfectly normal young adult.Footnote 20

Assessing the veracity of development interventions (or aspects of them) with high causal density (e.g., women’s empowerment projects, programs to change adolescent sexual behavior in the face of the HIV/AIDS epidemic) requires evaluation strategies tailored to accommodate this reality. Precisely because the ‘impact’ (wholly or in part) of these interventions often cannot be truly isolated, and is highly contingent on the quality of implementation, any observed impact is very likely to change over time, across contexts, and at different scales of implementation; as such, we need evaluation strategies able to capture these dynamics and provide correspondingly usable recommendations. Crucially, strategies used to assess high causal density interventions are not “less rigorous” than those used to assess their low causal density counterpart; any evaluation strategy, like any tool, is “rigorous” to the extent it deftly and ably responds to the questions being asked of it.Footnote 21

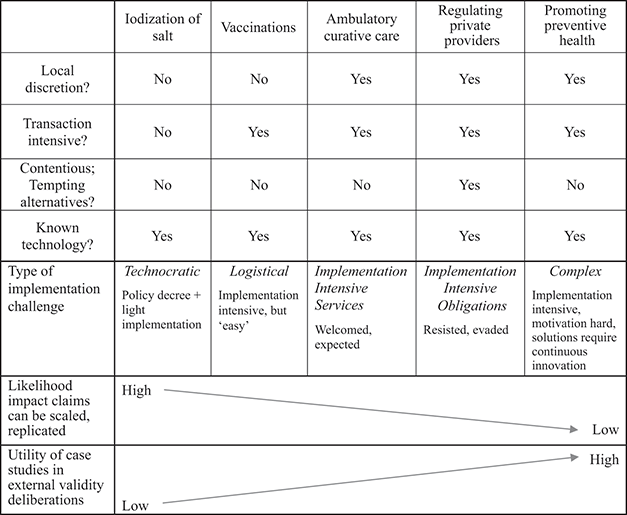

To operationalize causal density we need a basic analytical framework for distinguishing more carefully between these ‘low’ and ‘high’ extremes: we can agree that a lawn mower and a family are qualitatively different ‘systems’, but how can we array the spaces in between?Footnote 22 Four questions can be proposed to distinguish between different types of problems in development.Footnote 23 First, how many person-to-person transactions are required?Footnote 24 Second, how much discretion is required of front-line implementing agents?Footnote 25 Third, how much pressure do implementing agents face to do something other than respond constructively to the problem?Footnote 26 Fourth, to what extent are implementing agents required to deploy solutions from a known menu or to innovate in situ?Footnote 27 These questions are most useful when applied to specific operational challenges; rather than asserting that (or trying to determine whether) one ‘sector’ in development is more or less ‘complex’ than another (e.g., ‘health’ versus ‘infrastructure’), it is more instructive to begin with a locally nominated and prioritized problem (e.g., how can workers in this factory be afforded adequate working conditions and wages?) and asking of it the four questions posed above to interrogate its component elements. An example of an array of such problems within ‘health’ is provided in Table 5.1; by providing categorical yes/no answers to these four questions we can arrive at five discrete kinds of problems in development: technocratic, logistical, implementation intensive services, implementation intensive obligations, and complex.

| Local discretion? | Transaction intensive? | Contentious; Tempting alternatives? | Known technology? | Type of implementation challenge | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iodization of salt | No | No | No | Yes |

|

| Vaccinations | No | Yes | No | Yes |

|

| Ambulatory curative care | Yes | Yes | No(ish) | Yes | Implementation Intensive Services (welcomed, expected) |

| Regulating private providers | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

|

| Promoting preventive health | Yes | Yes | No | No |

|

So understood, problems are truly ‘complex’ that are highly transaction intensive, require considerable discretion by implementing agents, yield powerful pressures for those agents to do something other than implement a solution, and have no known (ex ante) solution.Footnote 28 The eventual solutions to these kinds of problems are likely to be highly idiosyncratic and context specific; as such, and irrespective of the quality of the evaluation strategy used to discern their ‘impact’, the default assumption regarding their external validity should be, I argue, zero. Put differently, in such instances the burden of proof should lie with those claiming that the result is in fact generalizable. (This burden might be slightly eased for ‘implementation intensive’ problems, but some considerable burden remains nonetheless.) I hasten to add, however, that this does not mean others facing similarly ‘complex’ (or ‘implementation intensive’) challenges elsewhere have little to learn from a successful (or failed) intervention’s experiences; on the contrary, it may be highly instructive, but its “lessons” reside less in the content of its final design characteristics than in the processes of exploration and incremental understanding by which a solution was proposed, refined, supported, funded, implemented, refined again, and assessed – that is, in the ideas, principles, and inspiration from which, over time, a solution was crafted and enacted. This is the point at which analytic case studies can demonstrate their true utility, as I discuss in the following sections.

5.3.2 Implementation Capability

Another danger stemming from a single-minded focus on a project’s design characteristics as the causal agent determining observed outcomes is that implementation dynamics are largely overlooked, or at least assumed to be nonproblematic. If, as a result of an RCT (or series of RCTs), a given conditional cash transfer (CCT) program is deemed to have ‘worked’,Footnote 29 we all too quickly presume that it can and should be introduced elsewhere, in effect ascribing to it “proof of concept” status. Again, we can be properly convinced of the veracity of a given evaluation’s empirical findings and yet have grave concerns about its generalizability. If from a ‘causal density’ perspective our four questions would likely reveal that in fact any given CCT comprises numerous elements, some of which are ‘complex’, from an ‘implementation capability’ perspective the concern is more prosaic: how confident can we be that any designated implementing agency in the new country or context (e.g., Ministry of Social Welfare) would in fact have the capability to do so, at the designated scale of operation?

Recent research and everyday experience suggests, again, that the burden of proof should lie with those claiming or presuming that the designated implementing agency in the proposed context is indeed up to the task (Reference Pritchett and SandefurPritchett and Sandefur 2015). Consider the delivery of mail. It is hard to think of a less contentious and ‘less complex’ task: everybody wants their mail to be delivered accurately and punctually, and doing so is almost entirely a logistical exercise.Footnote 30 The procedures to be followed are unambiguous, universally recognized (by international agreement), and entail little discretion on the part of implementing agents (sorters, deliverers). A recent empirical test of the capability of mail delivery systems around the world, however, yielded sobering results. Reference Chong, La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes and ShleiferChong et al. (2014) sent letters to 10 nonexistent addresses in 159 countries, all of which were signatories to an international convention requiring them simply to return such letters to the country of origin (in this case the United States) within 90 days. How many countries were actually able to perform this most routine of tasks? In 25 countries none of the 10 letters came back within the designated timeframe; of countries in the bottom half of the world’s education distribution the average return rate was 21 percent of the letters. Working with a broader cross-country dataset documenting the current levels and trends in state capability for implementation, Reference Andrews, Pritchett and WoolcockAndrews, Pritchett, and Woolcock (2017) ruefully conclude that, by the end of the twenty-first century, only about a dozen of today’s low-income countries will have acquired levels of state capability equal to that of today’s least-rich OECD countries.Footnote 31

The general point is that in many developing countries, especially the poorest, implementation capability is demonstrably low for ‘logistical’ tasks, let alone for ‘complex’ ones. ‘Fragile states’, almost by definition, cannot readily be assumed to be able to undertake complex tasks (such as responding to medical emergencies after natural disasters) even if such tasks are desperately needed there. And even if they are in fact able to undertake some complex projects (such as regulatory or tax reform), which would be admirable, yet again the burden of proof in these instances should reside with those arguing that such capability to implement the designated intervention does indeed exist (or can readily be acquired). For complex interventions as here defined, high-quality implementation is inherently and inseparably a constituent element of any success they may enjoy (see Honig 2018); the presence in novel contexts of implementing organizations with the requisite capability thus should be demonstrated rather than assumed by those seeking to replicate or expand ‘complex’ interventions.

5.3.3 Reasoned Expectations

The final domain of consideration, which I call ‘reasoned expectations’, focuses attention on an intervention’s known or imputed trajectory of change. By this I mean that any empirical claims about a project’s putative impact, independently of the method(s) by which the claims were determined, should be understood in the light of where we should reasonably expect a project to be by when. As I have documented elsewhere (Reference WoolcockWoolcock 2009), the default assumption in the vast majority of impact evaluations is that change over time is monotonically linear: baseline data is collected (perhaps on both a ‘treatment’ and a ‘control’ group) and after a specified time follow-up data is also obtained; following necessary steps to control for the effects of selection and confounding variables, a claim is then made about the net impact of the intervention, and, if presented graphically, is done by connecting a straight line from the baseline scores to the net follow-up scores. The presumption of a straight-line impact trajectory is an enormous one, however, which becomes readily apparent when one alters the shape of the trajectory (to, say, a step-function or a J-curve) and recognizes that the period between the baseline and follow-up data collection is mostly arbitrary (or chosen in accordance with administrative or political imperatives); with variable time frames and nonlinear impact trajectories, however, vastly different accounts can be provided of whether or not a given project is “working.”

Consider Figure 5.1. If one was ignorant of a project impact’s underlying functional form, and the net impact of four projects was evaluated “rigorously” at point C, then remarkably similar stories would be told about these projects’ positive impact, and the conclusion would be that they all unambiguously “worked.” But what if the impact trajectory of these four interventions actually differs markedly, as represented by the four different lines? And what if the evaluation was conducted not at point C but rather at points A or B? At point A one tells four qualitatively different stories about which projects are “working”; indeed, if one had the misfortune to be the team leader on the J-curve project during its evaluation by an RCT at point A, one may well face disciplinary sanction for not merely having “no impact” but for making things worse – as verified by “rigorous evidence”! If one then extrapolates into the future, to point D, it is only the linear trajectory that turns out to yield continued gains; the rest either remain stagnant or decline markedly.

The conclusions reached in an otherwise seminal paper by Reference Casey, Glennerster and MiguelCasey, Glennerster, and Miguel (2012) embody these concerns. Using an innovative RCT design to assess the efficacy of a ‘community driven development’ project in Sierra Leone, the authors sought to jointly determine the impact of the project on participants’ incomes and the quality of their local institutions. They found “positive short-run effects on local public goods and economic outcomes, but no evidence for sustained impacts on collective action, decision-making, or the involvement of marginalized groups, suggesting that the intervention did not durably reshape local institutions” (Reference Casey, Glennerster and Miguel2012: 1755). This may well be true empirically, but such a conclusion presumes that incomes and institutions change at the same pace and along the same trajectory; most of what we know from political and social history would suggest that institutional change in fact follows a trajectory (if it has one at all) more like a step-function or a J-curve than a straight line, and that our ‘reasoned expectations’ against which to assess the effects of an intervention trying to change ‘local institutions’ should thus be guided accordingly.Footnote 32

Recent work deftly exemplifies the importance of such considerations. Reference Baird, McIntosh and ÖzlerBaird, McIntosh, and Özler (2019:182) provide interesting findings from an unconditional cash transfer program in Malawi, in which initially significant declines in teen pregnancy, HIV prevalence, and early marriage turned out, upon a subsequent evaluation conducted two years after the program had concluded, to have dissipated. On the other hand, a conditional cash transfer (CCT) program in the same country offered to girls who were not in school led to “sustained program effects on school attainment, early marriage, and pregnancy for baseline dropouts receiving CCTs. However, these effects did not translate into reductions in HIV, gains in labor market outcomes, or increased empowerment.” Same country, different projects, both with variable nonlinear impact trajectories, and thus different conclusions regarding program effectiveness.Footnote 33 One surely needs to have several, sophisticated, contextually grounded theories of change to anticipate and accurately interpret such diverse findings at a given point in time – and especially to inform considerations about the programs’ likely effectiveness over time in different country contexts. But, alas, this is rarely the case.Footnote 34

Again, the key point here is not that the empirical strategy per se is flawed (it clearly is not – in this instance, in fact, it is exemplary); it is that (a) we rarely have more than two data points on which to base any claims about impact, and, when we do, it can lead to rather different interpretations about impact ‘there’ (and thus its likely variable impact ‘here’); and (b) rigorous (indeed all) results must be interpreted against a theory of change. Perhaps it is entirely within historical experience to see no measurable change on institutions for a decade; perhaps, in fact, one needs to toil in obscurity for two or more decades as the necessary price to pay for any ‘change’ to be subsequently achieved and discerned;Footnote 35 perhaps seeking such change is a highly ‘complex’ endeavor, and as such has no consistent functional form, or has one that is apparent only with the benefit of hindsight, and is an idiosyncratic product of a series of historically contingent moments and processes (see Reference Woolcock, Szreter and RaoWoolcock, Szreter, and Rao 2011). In any event, the interpretation and implications of “the evidence” from any evaluation of any intervention is never self-evident; it must be discerned in the light of theory and benchmarked against reasoned expectations, especially when that intervention exhibits high causal density and necessarily requires robust implementation capability.Footnote 36

In the first instance this has important implications for internal validity, but it also matters for external validity, since one dimension of external validity is extrapolation over time. As Figure 5.1 shows, the trajectory of change between the baseline and follow-up points bears not only on the claims made about ‘impact’ but also on the claims made about the likely impact of this intervention in the future. These extrapolations only become more fraught once we add the dimensions of scale and context, as the Reference Bruhn and McKenzieBraun and McKenzie (2013) and Reference Bold, Kimenyi, Mwabu, Ng’ang’a and SandefurBold et al. (2013) papers reviewed earlier show. The abiding point for external validity concerns is that decision-makers need a coherent theory of change against which to accurately assess claims about a project’s impact ‘to date’ and its likely impact ‘in the future’; crucially, claims made on the basis of a “rigorous methodology” alone do not solve this problem.

5.3.4 Integrating These Domains into a Single Framework

The three domains considered in this analysis – causal density, implementation capability, and reasoned expectations – comprise a basis for pragmatic and informed deliberations regarding the external validity of development interventions in general and ‘complex’ interventions in particular. While data in various forms and from various sources can be vital inputs into these deliberations (see Reference Bamberger, Rao, Woolcock, Tashakkori and TeddlieBamberger, Rao, and Woolcock 2010; Reference Woolcock, Nagatsu and RuzzeneWoolcock 2019), when the three domains are considered as part of a single integrated framework for engaging with ‘complex’ interventions, it is extended deliberations on the basis of analytic case studies, I argue, that have a particular comparative advantage for eliciting the “key facts” necessary for making hard decisions about the generalizability of those interventions (or their constituent elements). Indeed, it is within the domains of causal density, implementation capability, and reasoned expectations, I argue, that the “key facts” themselves reside.

These deliberations move from the analytical and abstract to the decidedly concrete when hard decisions have to be made about the impact and generalizability of claims pertaining to truly complex development interventions, such as those seeking to empower the marginalized, enhance the legitimacy of justice systems, or promote more effective local government. The Sustainable Development Goals have put issues such as these squarely and formally on the global agenda, and in the years leading up to 2030 there will surely be a flurry of brave attempts to ‘measure’ and ‘demonstrate’ that all countries have indeed made ‘progress’ on them. Is fifteen years (2015–2030) a ‘reasonable’ timeframe over which to expect any such change to occur? What ‘proven’ instruments and policy strategies can domestic and international actors wield in response to such challenges? There aren’t any, and there never will be, at least not in the way there are now ‘proven’ ways in which to build durable roads in high rainfall environments, tame high inflation, or immunize babies against polio. But we do have an array of tools in the social science kit that can help us navigate the distinctive challenges posed by truly complex problems – we just need to forge and protect the political space in which they can be ably deployed. Analytic case studies, so understood, are one of those tools.

5.4 Harnessing the Distinctive Contribution of Analytic Case Studies

When carefully compiled and conveyed, case studies can be instructive for policy deliberations across the analytic space set out in Table 5.2. Our focus here is on development problems that are highly complex, require robust implementation capability, and unfold along nonlinear context-specific trajectories, but this is only where the comparative advantage of case studies is strongest (and where, by extension, the comparative advantage of RCTs for engaging with external validity issues is weakest). It is obviously beyond the scope of this chapter to provide a comprehensive summary of the theory and strategies underpinning case study analysis,Footnote 37 but three key points bear some discussion (which I provide below): the distinctiveness of case studies as a method of analysis in social science beyond the familiar qualitative/quantitative divide; the capacity of case studies to elicit causal claims and generate testable hypotheses; and (related) the focus of case studies on exploring and explaining mechanisms (i.e., identifying how, for whom, and under what conditions outcomes are observed – or “getting inside the black box”).

Table 5.2 An integrated framework for assessing external validity claims

The rising quality of the analytic foundations of case study research has been one of the underappreciated (at least in mainstream social science) methodological advances of the last few decades (Reference MahoneyMahoney 2007). Where everyday discourse in development research typically presumes a rigid and binary ‘qualitative’ or ‘quantitative’ divide, this is a distinction many contemporary social scientists (especially historians, historical sociologists, and comparative political scientists) feel does not aptly accommodate their work – if ‘qualitative’ is primarily understood to mean ethnography, participant observation, and interviews. These researchers see themselves as occupying a distinctive epistemological space, using case studies (across varying units of analysis: countries to firms to events) to interrogate instances of phenomena – with an ‘N’ of, say, 30, such as revolutions – that are “too large” for orthodox qualitative approaches and “too small” for orthodox quantitative analysis. (There is no inherent reason, they argue, why the problems of the world should array themselves in accordance with the bimodal methodological distribution social scientists otherwise impose on them.)

More ambitiously, perhaps, case study researchers also claim to be able to draw causal inferences (see Reference MahoneyMahoney 2000; Reference LevyLevy 2008; Cartwright, Chapter 2 this volume). Defending this claim in detail requires engagement with philosophical issues beyond the scope of this chapter,Footnote 38 but a pragmatic application can be seen in the law (Reference HonoréHonoré 2010), where it is the task of investigators to assemble various forms and sources of evidence (inherently of highly variable quality) as part of the process of building a “case” for or against a charge, which must then pass the scrutiny of a judge or jury: whether a threshold of causality is reached in this instance has very real (in the real world) consequences. Good case study research in effect engages in its own internal dialogue with the ‘prosecution’ and ‘defense’, posing alternative hypotheses to account for observed outcomes and seeking to test their veracity on the basis of the best available evidence. As in civil law, a “preponderance of the evidence” standardFootnote 39 is used to determine whether a causal relationship has been established. This is the basis on which causal claims (and, needless to say, highly ‘complex’ causal claims) affecting the fates of individuals, firms, and governments are determined in courts every day; deploying a variant on it is what good case study research entails.

Finally, by exploring ‘cases within cases’ (thereby raising or lowering the instances of phenomena they are exploring), and by overtly tracing the evolution of given cases over time within the context(s) in which they occur, case study researchers seek to document and explain the processes by which, and the conditions under which, certain outcomes are obtained. (This technique is sometimes referred to as process tracing – or, as noted earlier, assessing the ‘causes of effects’ as opposed to the ‘effects of causes’ approach characteristic of most econometric research.) Case study research finds its most prominent place in applied development research and program assessment in the literature on ‘realist evaluation’,Footnote 40 where the abiding focus is exploiting, exploring, and explaining variance (or standard deviations): that is, on identifying what works for whom, when, where, and why.Footnote 41 In their study of service delivery systems across the Middle East and North Africa, Reference Brixi, Lust and WoolcockBrixi, Lust, and Woolcock (2015) use this strategy – deploying existing household survey data to ‘map’ broad national trends in health and education outcomes, complementing it with analytical case studies of specific locations that are positive ‘outliers’ – to explain how, within otherwise similar (and deeply challenging) policy environments, some implementation systems become and remain so much more effective than others (see also McDonnell 2020). This is the signature role that case studies can play for understanding, and sharing the lessons from, ‘complex’ development interventions on their own terms, as has been the central plea of this chapter.

5.5 Conclusion

The energy and exactitude with which development researchers debate the veracity of claims about ‘causality’ and ‘impact’ (internal validity) has yet to inspire corresponding firepower in the domain of concerns about whether and how to ‘replicate’ and ‘scale up’ interventions (external validity). Indeed, as manifest in everyday policy debates in contemporary development, the gulf between these modes of analysis is wide, palpable, and consequential: the fates of billions of dollars, millions of lives, and thousands of careers turn on how external validity concerns are addressed, and yet too often the basis for these deliberations is decidedly shallow.

It does not have to be this way. The social sciences, broadly defined, contain within them an array of theories and methods for addressing both internal and external validity concerns; they are there to be deployed if invited to the table (see Reference Stern, Stame, Mayne, Forss, Davies and BefaniStern et al. 2012). This chapter has sought to show that ‘complex’ development interventions require evaluation strategies tailored to accommodate that reality; such interventions are square pegs which when forced into methodological round holes yield confused, even erroneous, verdicts regarding their effectiveness ‘there’ and likely effectiveness ‘here’. In the early twenty-first century, development professionals routinely engage with issues of increasing ‘complexity’: consolidating democratic transitions, reforming legal systems, promoting social inclusion, enhancing public sector managementFootnote 42 – the list is endless. These types of issues are decidedly (wickedly) ‘complex’, and responses to them need to be prioritized, designed, implemented, and assessed accordingly. Beyond evaluating such interventions on their own terms, however, it is as important to be able to advise front-line staff, senior management, and colleagues working elsewhere about when and how the “lessons” from these diverse experiences can be applied. Deliberations centered on causal density, implementation capability, and reasoned expectations have the potential to usefully elicit, inform, and consolidate this process.