Introduction

Over the past two decades, scholars researching African states have produced nuanced analyses of powerful social actors operating “beside the state,” particularly in peripheral areas (Bellagamba & Klute Reference Bellagamba and Klute2008). Such spaces are regulated by a range of actors, many of whom entertain close relationships with the local state (Boone Reference Boone2003; Meagher Reference Meagher2012; Titeca & Flynn Reference Titeca and Flynn2014).Footnote 1 In general, state actors are aware of non-state regulatory practices, but are either unable or unwilling to impose their authority, due to limited resources or a reluctance to forgo the profit they draw from illegal economic activities (Roitman Reference Roitman, Callaghy, Kassimir and Latham2001). To describe this mix of state and non-state regulatory authorities, some scholars employ the term “hybrid governance” (Meagher Reference Meagher2012; Titeca & Flynn Reference Titeca and Flynn2014). Hybrid governance arrangements can take many forms and have different temporalities. The term “governance figuration” perhaps best highlights the malleable and sometimes ephemeral nature of these arrangements, in which one or other of the parties involved may win the upper hand for a certain period of time before being reversed again (Förster & Koechlin Reference Fofana2011).Footnote 2

Present scholarship is concerned with providing a more nuanced picture of how different regulatory actors and practices operate side by side on a daily basis. As Alice Bellagamba and Georg Klute observe, governance configurations shift through time, and non-state actors operate below, beside, or beyond the state. “Beside” the state refers to configurations in which non-state actors have accumulated regulatory functions in spaces largely neglected by the central state. In some of these cases, non-state actors have acquired considerable powers as a regulatory authority at a sub-national level, in parallel to provincial or local state institutions. In Bellagamba and Klute’s ideal-typical categorization, “below” refers to a more hierarchical relationship, stressing the subordination of non-state actors in local arenas. “Beyond” in their typology refers to powers of non-state actors that challenge state authority in sub-national arenas, often due to transnational connections, such as businessmen, armed groups with a foreign basis, multinational enterprises, or international NGOs (Bellagamba & Klute Reference Bellagamba and Klute2008).

Mande hunters or dozo fraternities are one such non-state actor group that has adopted regulatory functions in West Africa (Bassett Reference Bassett2003; Ferme Reference Ferme2001; Hellweg Reference Hellweg2011; Leach Reference Leach2000). Local governance arrangements between Mande hunter groups and the state show great regional diversity. This article focuses on the prefecture of Ouangolodougou (Ouangolo for short) in northern Côte d’Ivoire in the period immediately after the Ivoirian civil war (2002–2011).Footnote 3 Whereas dozos have been characterized as the weaker party in the dozos/state relationship in northwestern Côte d’Ivoire in the 1990s, in the current post-Ivorian civil war era they have aggrandized their influence. Dozos use performative practices to display their power in order to assert their role as security agents, a capacity accumulated during the recent violent crisis. If dozos once operated below the state (in Odienné in the 1990s, for example), the dozo communities I observed in post-crisis Ouangolo display a more self-conscious and assertive attitude beside the state. In a context of illicit border trade in Ouangolo, dozos operate as security actors and border guards autonomously of the local state, albeit with the caveat that their influence remains strong only in the less profitable rural borderlands zone. These findings show that the dozos may not be as easily contained to either the rural sphere or any anachronistically defined ethno-regional space of origin, as was the case before the civil war.

The following sections briefly introduce Mande hunters and review their relationship with the state in local contexts of West Africa. After a historical summary of hunter/state relations in Côte d’Ivoire, the hunter association of Ouangolo with its national and transnational connections is described, beginning with the security governance system of the dozos in the rural borderland and then shifting to the urban sphere, where dozos try to gain a stronger foothold using performative means. This section is followed by an analysis of hunter/state relations, including examples of mutual cooperation and contestation, and concludes with some final observations about the dozos/state relationship in post-conflict Ouangolo.

Mande hunters in the West African context

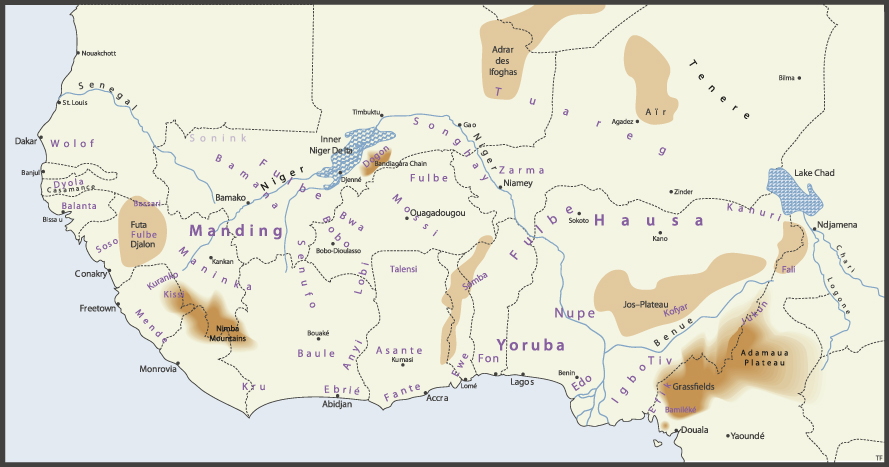

A distinct brotherhood of hunters, generally referred to as dozoton or donzoton, exists throughout the Mande-speaking areas of forested and Sahelian West Africa. The term most often used to refer to the hunters of this brotherhood in Côte d’Ivoire is dozos or donzos. Footnote 4 The foundation of this brotherhood has been dated as early as the Mali Empire, around the thirteenth century (Cissé Reference Cissé1964). Today, local versions of the Mande hunters exist in the geographical area that extends from present day Senegal and Sierra Leone to Guinea, Mali, Burkina Faso, and Côte d’Ivoire (Hellweg Reference Hellweg2006; Ferrarini Reference Ferrarini2014) (see Map 1).Footnote 5

Map 1. West Africa

Mande hunters are known for their healing and protective powers, praise-singing, waging war, and establishing new communities in the form of villages (Bassett Reference Bassett2003:3; Hellweg Reference Hellweg2011). Literature from western Burkina Faso, Mali, and northern Côte d’Ivoire shows that the hunters are generally farmers (Ferrarini Reference Ferrarini2014, Reference Ferrarini2016; Hellweg Reference Hellweg2011; Kedzierska-Manzon 2014). Hunters of the brotherhood often wear a special smock or shirt, which is washed in protective potions and draped with amulets, such as small mirrors and magical objects wrapped in leather (McNaughton Reference McNaughton1982; Hellweg Reference Hellweg2011; Ferme Reference Ferme2001; Ferrarini Reference Ferrarini2014). Other typical accessories in Côte d’Ivoire may include a pipe, a pointed hat, and a rifle—often a 12-gauge shotgun (Hellweg Reference Hellweg2011). According to Joseph Hellweg, hunters vow during the initiation ritual “not to lie, steal, commit adultery or betray other dozos” (Hellweg Reference Hellweg2011:4). Initiates who do not follow these rules can no longer count on the patron spirit’s protection (Hellweg Reference Hellweg2006). This lends the brotherhood an ethical basis on which to operate (Hellweg Reference Hellweg2006, Reference Hellweg2011; Ferrarini Reference Ferrarini2014:48).Footnote 6

Over the last three decades, dozos have expanded their activities, particularly in the field of security. The benkadi movement, for example, is a bureaucratized security union of dozos, which is organized similar to any other association. In practical terms, the master hunter, for instance, is seconded by a president and vice-president, who may chair meetings and communicate with external actors, such as state agents.Footnote 7 In Côte d’Ivoire in the 1990s, some Mande hunters were hired as watchmen for private property, while others guarded neighborhoods at night (Bassett Reference Bassett2003, Hellweg Reference Hellweg2011). Observations about the security sector in Burkina Faso, Mali (Hagberg Reference Hagberg2004; Moseley Reference Moseley2017), Niger (Göpfert Reference Göpfert2016), and elsewhere, such as Togo (van Rouveroy van Nieuwaal Reference van Rouveroy van Nieuwaal2005) and Kenya (Dobson Reference Dobson2019), offer important parallels.Footnote 8 The adoption of such new roles in public life has led dozos into new relationships with the state across West Africa, with particular relevance for understanding the Ivorian situation. This relationship takes various forms in different contexts and transforms according to political events.

According to Melissa Leach, the Guinean state empowered dozo units in the 1990s to guard conservation areas and its forested borders against the incursion of rebel groups from the civil war in Sierra Leone (Leach Reference Leach2000). She argues that the hunter fraternities operated as a supplementary force in collaboration with the state. Hence, hunters supported and complemented the state in a hierarchical relationship; in Klute and Bellagamba’s terms, hunters operated below the state. The same was true for Sierra Leone at the beginning of the civil war, when the army recruited hunters as guides. However, when the national armed forces failed to provide security for the population as the war progressed, Mende kamajors and Kuranko tamaboros (both Mande hunters) developed into a civil defense force (Ferme Reference Ferme2001; Leach Reference Leach2000; Peters Reference Peters2011). Some of these self-defense groups had a closer relationship with the state, while the relationship of other groups was more distant. Those with a more distant relationship clearly adopted a more autonomous stance. However, all of these irregular troops might be seen as working alongside or beside the state. In his analysis of the relationship between African elites and Mande hunters in Mali, Karim Traoré writes critically: “The relationship between the political leaders of a modern state and the hunters is fundamentally the same one that the colonial power used to have with the hunters” (Traoré Reference Traoré2004:104). He deplores the lack of imagination of a French-educated elite to think beyond imported models of culture and governance. For instance, in Malian festivals, the state displays the hunters in a folkloristic manner, as “subsidiary insignia of power” (Traoré Reference Traoré2004:104). Such an attitude also holds true for many state officials in Côte d’Ivoire.

In the context of increased insecurity on Ivorian highways and in urban neighborhoods in the late 1980s, dozo units began to organize nightly patrols (Bassett Reference Bassett2004; Förster Reference Förster2010; Hellweg Reference Hellweg2011:29). The dozos’ success in providing security resulted in a countrywide boom in dozo security patrols (Bassett Reference Bassett2003:10, 2004:36; Hellweg Reference Hellweg2004). At first, the state encouraged dozo security work, but in the second half of the 1990s, in the context of increased political rivalries, the government developed a more hostile attitude.Footnote 9 Dozos were no longer perceived as helpful security agents, but rather as an armed brotherhood with regional loyalties to the Mande-speaking North. Indeed, questionable regional loyalties regularly create distrust and tarnish the hunter/state relationship in different multi-ethnic states (Bassett Reference Bassett2003; Leach Reference Leach2000; Hagberg Reference Hagberg2004). The Ivorian government made efforts to restrict dozo activities to their region of origin in northern Côte d’Ivoire and prohibited their carrying of firearms and their employment as guards in the southern provinces (Bassett Reference Bassett2004:41; Hagberg & Ouattara Reference Hagberg, Ouattara, Kirsch and Grätz2010). Attempts to confine dozos to the north were part of a more general trend in Ivorian politics, in which ethnic belonging and autochthony became more and more accentuated, leading eventually to a violent political crisis (Akindès 2004; Babo Reference Babo, Lawrance and Stevens2016; Banégas Reference Banégas2006; Konaté Reference Konaté2003; McGovern Reference McGovern2011).

In such a tense political environment, it should come as no surprise that Mande hunters failed to obtain national recognition from the state for their security work (Hellweg Reference Hellweg2011:147–52). At a sub-national level, however, security arrangements between hunters and local state officials were possible. In Odienné, for instance, the prefect gave his oral agreement in 1997 for Benkadi to provide security (Hellweg Reference Hellweg2011:167). According to Hellweg, what emerged was a very successful state/non-state cooperation (Hellweg Reference Hellweg2011:219).Footnote 10 The key to successful collaboration was that dozos regularly informed local officials about their work, deferred to local authorities, and avoided openly challenging the state (Hellweg Reference Hellweg2011:136). This form of relationship in which the dozos became an unofficial police force can clearly be termed subordination, a cooperation that sees the place of dozos as below that of the state (Bellagamba & Kulte 2008). Unfortunately, information about local configurations in other parts of Côte d’Ivoire in the 1990s is lacking.

Between 2002 and 2011, during the decade-long conflict in Côte d’Ivoire, the northern half of the country was controlled by a rebel movement, Les Forces Nouvelles. This armed group was dominated by Mande-speakers who had suffered most from the governments’ exclusionary politics (Babo Reference Babo, Lawrance and Stevens2016). Sharing ethno-regional belonging and political grievances with the insurgents, many dozos joined the rebellion, whereas others chose to avoid the war (Förster Reference Förster2010).Footnote 11 In combat, or later in urban security provision, rebels generally recognized dozos as equal partners. One dozo leader, Mamadou Bamba, represented dozos at the top level of the rebellion, in the committee of the General Secretariat. Bamba created the Compagnie des guerriers de la lumière, a hunter unit that worked closely with the Forces Nouvelles. Furthermore, in Korhogo, for instance, a major northern town, the dozo brotherhood succeeded in establishing itself as the city’s main security provider (Förster Reference Förster, Peters, Koechlin, Förster and Zinkernagel2009:339, 2010, 2015). Insurgents and hunters engaged in what has been described as a “segmentary governance figuration” (Förster & Koechlin Reference Förster and Koechlin2011). The term “segmentary” highlights complementarity and equality of rank, which corresponds to “beside” in Bellagamba and Klute’s typology.Footnote 12 Some of the rebels were initiated dozos and often displayed hunter’s accessories in combination with their military wear to aggrandize a mystical aura and power in order to deter their enemies (Hellweg & Médevielle Reference Hellweg and Médevielle2017). During the violent crisis, performative means were frequently used by irregular forces, rebels, and dozos alike, in order to display power and to communicate how they wished to be viewed (Heitz-Tokpa Reference Heitz Tokpa2013). Hence, similarly to Sierra Leone, hunters adopted a more autonomous role in Côte d’Ivoire’s civil war, although on the side of the rebels.

The first post-conflict government under the northern Alassane Ouattara publicly acknowledged the contribution of dozo brotherhoods during the violent crisis.Footnote 13 Whereas his predecessor had refused to step aside after electoral defeat, the new president only managed to take office because of a joint military intervention (Fofana Reference Fofana2011; Straus Reference Straus2011).Footnote 14 This created a kind of indebtedness on the part of the government toward its armed supporters, including many dozo groups. During Ouattara’s first term in office, the government launched initiatives to manage and control the brotherhood. For instance, the government outlawed by decree the involvement of parallel forces and armed non-state actors—including dozos—in security missions. Furthermore, regulations for carrying weapons and munition were tightened. However, neither regulation was suitably enforced at the sub-national level. In the north, hunters maintained a more public role. Research in Ouangolo reveals an intriguing relationship forged between hunters and the returning state. To explain how hunters assert their position beside the state, I draw on the “negotiating statehood” framework developed by Tobias Hagmann and Didier Péclard (2010).Footnote 15 They observe that state and non-state actors mobilize different resources and repertoires to negotiate their respective positions in local arenas. Resources refer to the material bases that actors can draw on, such as physical force or a range of economic resources and technical skills. Symbolic repertoires include ideologies, imageries, and/or cultural or religious identities that are able to legitimize authority for certain social groups (Hagmann & Péclard Reference Hagmann and Péclard2010:547).

The field research for this article was conducted as part of a study of social dynamics in the border region of Ouangolo.Footnote 16 Between 2014 and 2018, I spent a total of four months in the northern border triangle between Côte d’Ivoire, Burkina Faso, and Mali. Dozos attracted my attention due to their controls at informal border crossing points. I stayed in the compound of Domba Ouattara, local chef de terre and chief of the hunters’ association.Footnote 17 This proximity allowed me to observe the dozo leadership and their interactions with state actors and to participate in various activities. I rode regularly behind dozos on their motorbikes to accompany them on forays into the countryside and to border markets. As the chief and some of his younger entourage did not speak French, a research assistant not from the family stayed with me in the compound and translated.Footnote 18 Apart from spontaneous conversions, data for this article were also collected in about forty interviews with dozos of different status, farmers and herders, chiefs, and state representatives from the (sub-)prefects, police, gendarmerie, and the mayor’s office.

The hunter association of Ouangolodougou

The town of Ouangolodougou has around 38,000 inhabitants (INS 2015). The last major town before the Burkina Faso border (30km) and Mali (90km), Ouangolo has a gendarmerie, a police station, a general hospital, and two secondary schools. Its biggest asset, however, is the customs clearance service which governs movements to and from Burkina Faso. Daily, heavily laden trucks from Côte d’Ivoire’s seaport pass through Ouangolo to reach the landlocked northern neighbors (Nassa Reference Nassa2005). Trucks on paved main roads are the most visible part of the cross-border trade. However, in the rural borderlands, too, goods cross unofficial border crossing points and provide additional income for the farmers, traders, and dozos.

Hellweg describes the Mande hunters in northwestern Côte d’Ivoire as “poor, politically marginalized, mostly Muslim West African men” (2011:1). Generally, this is also true for Ouangolo. But the brotherhood’s social capital has attracted politicians (see also Hagberg Reference Hagberg2004). The Ouangolo dozo brotherhood is part of the association of the Tchologo region (comprising the prefectures of Ferkessédougou, Ouangolo, and Kong). The hunters’ association in Tchologo is headed by a man with discernible national political ambitions, Mamadou Coulibaly, the deputy mayor of Ferkessédougou. He used to work for the statutory vehicle inspection service, the Société ivoirienne de contrôles techniques automobiles et industriels (SICTA) but has since retired. He was able to invest in property and today drives a luxury car.

According to a list produced by the Ouangolo brotherhood’s secretary in 2015, their association in the Tchologo district has 5,209 registered members. The district consists of eleven sous-préfectures, five of which belong to the Ouangolo prefecture. At the national level, the association in Ouangolo recognizes Mamadou Bamba as leader.Footnote 19 Furthermore, the Tchologo dozos have a considerable number of members from Burkina Faso who regularly cross the border. In early 2018, a first meeting of the Tchologo group was held in Burkina Faso. This hints at the transnational potential of dozo networks (see also Ferrarini Reference Ferrarini2016). Considering that “beyond” in Bellagamba and Klute’s typology often refers to non-state actors with a foreign foothold, dozos may also draw on their transnational resources to strengthen their local position, if need be.

Around the Ouangolo dozo chief there is an inner circle of about ten young dozos equipped with motorbikes. They regularly patrol the countryside and run errands for the chief, taking them as far as Kong, Korhogo (Côte d’Ivoire), and Banfora (Burkina Faso). The secretary’s income mainly stems from his role and activities in the Benkadi movement, although he has a corn field for his family’s subsistence. He obtains money from checkpoints, gifts from farmers in the countryside as well as from the chief, and last but not least, remuneration from selling medicine and divination. At least two, if not three, of the younger dozos around the chief joined the ranks of the rebels during the recent violence.

In the present post-conflict period, weaponry abounds. Bandits and demobilized combatants who remain without regular income are particularly feared by the local population. Due to the closeness to the border, armed gangs have made this area insecure for decades. Since I began fieldwork in this region in February 2014, there have been regular attacks on people, either in the period before a major religious festival or on market days in the countryside. Often, convoys are made to travel in groups, as roads are considered unsafe at night. Many gendarmes come from elsewhere in Côte d’Ivoire and do not want to risk their lives in the wilderness of Ouangolo.

Unlike most state agents, dozos are generally from local families and consequently have local knowledge of who is who within the local social landscape. As they live in Ouangolo with their families, they have a personal interest in protecting both people and goods in this area. They sit at crossroads and village entrances or patrol the rural borderland. Almost daily, dozos go to the countryside and remote villages by motorbike, armed with rifles and knives. As I observed, people living in the countryside regularly stop dozos when they see them passing on motorbikes, telling them about various problems they have encountered, particularly about cattle theft.

Farmers in Ouangolo and civil servants alike invest in cattle. Cattle theft is a major issue in the Sahelian region (see Bukari, Sow, & Scheffran Reference Bukari, Sow and Scheffran2018). Most cattle owners I talked with said they had lost cattle in the past five years. The nearby border makes it easier to move cattle out of the country. If cattle have disappeared, farmers usually turn to dozos for help. Dozos search for the lost animals in the wilderness, a task which the gendarmerie will not undertake. Local state agents say that they are simply unable to cover the vast territory with the limited means at their disposal. Therefore, some are happy to rely on dozos as a supplementary force.

Dozos also function as an auxiliary customs service to enforce customs regulations as a complementary force in rural areas. Regulations prohibiting the exportation of cashew nuts toward the northern neighbors are difficult to enforce without controlling the rural border crossing points. During the cashew harvest in 2014, dozos handed over some traders to police or took small bribes from farmers, if they caught farmers trying to cross into Burkina Faso in the hope of getting a better price for their product.

A spatial separation of activities is crucial for dozos to be able to work side by side with the state (Heitz-Tokpa Reference Heitz Tokpa, Engel, Boeckler and Müller-Mahn2018). During the insurgency, roadblocks on paved roads in the north were manned by hunters and insurgents alike. With the redeployment of the state’s security apparatus, however, dozos were asked to leave paved main roads to the state via an inter-ministerial circular in June 2012. At the local level in Ouangolo, dozos left the paved roads and continued their security work at rural checkpoints. Since that time, the sphere of the hunters has begun at the edges of the wilderness from the outskirts of towns and is based on a shared understanding among all actors concerned. By operating in different spaces, dozos and the state avoid confrontations, and their activities complement each other. In the contemporary post-conflict phase, dozos tend to confine their operations to rural space or wilderness, while the sphere of the state’s armed forces remains the towns and paved roads. The urban and rural spaces are linked via different material gains. Both state agents and dozos take money from passengers for private use but on very different scales: where state agents demand FCFA1000/EUR1.50, dozos ask for FCFA100/EUR0.15.Footnote 20 Consequently, there is a certain competition between the hunters and the state agents to occupy strategic points.

Hunters on patrol in the rural borderland

A particularly telling example of dozos’ authority and autonomy in rural areas can be found in the border hamlet of Bemavogo Badala, a relatively recent settlement on the land of Broundougou located at the Burkina Faso border (see Map 2). During harvest time, traders from Ouangolo and Burkina Faso come with trucks to buy maize, groundnuts, and other foodstuffs. The prices in this remote area are comparatively low. Neither the Ivorian nor the Burkinabé state has installed border guards at this border crossing point. Despite the fact that the cross-border trade is considerable, it is still not profitable for the state to send security or tax agents (see Dobler Reference Dobler2016).Footnote 21

Map 2. Northern Côte d’Ivoire

When Chief Bema, the founder and present chief of the settlement, initiated the market ten years ago, he asked dozos from nearby hamlets, who were active members of the Mande hunter society, to be responsible for maintaining security. He judged this necessary, as business and drinking quarrels were frequent on market days. Initially, the hunters sat down at the entrance to the hamlet to watch over the market. But soon, the hunters chose a place near the border, where everyone crossing the border stream to Burkina Faso had to pass. There is no bridge over the river, but people, trucks, and cattle can cross the water—at least during dry seasons. In the rainy season, people and motorbikes cross in a small wooden boat.

In the dry season of 2014, I visited Bemavogo for the first time. It happened to be market day. The dozo checkpoint was located at the top of the Ivorian side of the riverbank. A rope with a piece of red cloth attached to it barred the passage. In the shade on the roadside, several dozos sat on a wooden bench, their guns resting against a tree (Figure 1). Every now and then, people passed by, either going to or coming from the market. Some came on motorbikes, others by foot or on bicycles. People on motorbikes whom the hunters did not know were asked to show the papers or the sales receipt for the motorbike. The reason for this is that motorbikes are often stolen in one country and sold on the other side of the border—out of administrative reach. If the laminated receipts shown were considered satisfactory by a dozo, the passenger was allowed to continue his journey over the lowered rope. A hunter who was able to read would take care of such cases, while his illiterate colleagues would attend to other passengers or tasks at the checkpoint. Every passenger was asked where he was going and made to contribute a small sum ostensibly “to buy tea.” The average fee for passing a dozo checkpoint is FCFA100/EUR0.15. However, this dozo group capitalized on the opportunity offered by this shallow ford, a natural bottleneck, and people coming from Burkina Faso with chickens, for example, were made to pay FCFA250. The hunters made cattle herders, a minority in this region, pay particularly high sums (see also Hagberg Reference Hagberg, Hagberg and Tengan2000).

Figure 1. Informal border crossing point of the hunter brotherhood. Photo by Author.

On one occasion I observed three Fulani boys coming from the market on bicycles as they approached the checkpoint. They stopped close to the rope, turning their heads shyly towards the dozos, waiting for a sign to pass. But the dozo dealing with them was adamant that they must pay FCFA100 each. The dozo turned his head away from them and resumed chatting with his colleagues, as if he had forgotten about the boys. Other people passed through. Anyone who was good friends with a particular dozo or who had already paid that day could pass without paying. Women going to the stream to wash the dishes and clothes also went by without any problems. Some passengers did not even wait to be asked to pay something, but handed over 50 or 100 francs on arrival with no hesitation. The boys did not move for a while and waited. No other dozo intervened on their behalf. Eventually, the boys collected FCFA300 among themselves and handed over the money. The dozo threw the coins into a used bag on the ground and covered it with a cloth. When he later lifted the cloth, I saw the bag contained about FCFA5000/EUR7.50, consisting of bank notes and many coins. Later the same day, as the dozos were engaged in a conversation with friends, a Fulani man sidestepped the dozos by taking a shortcut through the bush without their noticing. In the evening, the chief of the group kept the largest sum. In the afternoon, however, when he was not paying attention, a younger dozo managed to slip a few coins into his own pocket.

During informal discussions with the members of the local Bemavogo population, my research assistant and I uncovered significant discontentment with the checkpoint’s dozos. A major complaint was that they took money from the population while doing little or nothing in return. The chief complained about their drunkenness, which made them unable to intervene when the need arose. A year later, in February 2015, the Bemavogo chief had the checkpoint moved back to its initial place at the entrance to the village, and the dozo head removed, after one particularly heated incident too many. According to the village headman and the victim, dozos had tied a man to one of the trees next to their checkpoint in revenge for a conflict with the man’s elder brother. The man was beaten badly and an exorbitant sum demanded. Similar or worse abuses of civilians have been documented since the 1990s (Hellweg Reference Hellweg2011). A UN investigation in Côte d’Ivoire revealed that during the violent conflict, dozos were involved in extrajudicial killings, detention of alleged thieves, and extortion (UN 2013).Footnote 22 As Kate Meagher (Reference Meagher2012) pointed out, non-state actors may not always increase the accountability of security provision.

How the Bemavogo border community dealt with this incident is instructive. When influential members of the victim’s family complained, Bemavogo’s chief intervened and addressed the head dozo in Ouangolo. Chief Bema—himself a hunter—registered himself as a dozo with the dozo brotherhood. Supported by Ouangolo’s chief hunter, he obtained authorization to mount his own checkpoint. Bema produced a document that stated that the checkpoint in Bemavogo had been installed in July 2011.Footnote 23 The document was signed and stamped by the president of the Tchologo district. It is noteworthy that such a document issued by the hunters’ Benkadi movement was considered necessary in this case. It was sufficient to quell all disputes concerning the dozo who had been dismissed. It showed that the dozo association and hierarchy would defend the right of Bema to have a checkpoint in his village. To calm the situation, the dismissed dozo received authorization from the dozo association to install a checkpoint not far from his own hamlet, which is closer to Ouangolo. Since this had been approved by the dozo association, there was little the man could do. Of course, the checkpoint near his hamlet would be much less lucrative. People said that he had stopped farming because the checkpoint at the border had been so profitable for him.

On the market day of February 7, 2015, the rehabilitated checkpoint at the entrance of the village was reopened with the new dozo group, composed of old and new members. A rope was put up to bar passage, but most of the time the rope lay on the ground. Chief Bema put one of his sons in charge. People attending the market and travelers stopped and exchanged greetings. Those whom the dozos did not know were asked where they were going, but no one was asked to pay money on this particular day. Later in the year, however, the checkpoint was moved back, closer to the border, and the new group began collecting road tolls as well. This time though, the money collected was handed over to chief Bema, who invested at least part of it in the primary school run by a volunteer teacher.

An interesting aspect about the border village of Bemavogo is the way the conflict with the dozos was entirely resolved among the dozos and within their hierarchy—implying a parallel structure to the state with its own means of sanction and correction. This case illustrates the authority and autonomy of dozos in rural areas. When rangers from the water and forest police wanted to inspect the area after the end of the armed conflict in 2011, they were accompanied and guided by dozos on their missions. This example further emphasizes the dozos’ power and authority beside the state in rural areas.

Dozo performance of urban power

By patrolling and policing rural borderlands and setting up checkpoints, hunters exercise power and perform, at least to a certain extent, the sovereign functions of the state (Hellweg Reference Hellweg2011). Part of the subtle repertoire of power games between dozos and the state are the display and performance of recognizable markers of power (Hagmann & Péclard Reference Hagmann and Péclard2010). This is necessary because the governance configuration whereby dozos have access to the resources of the rural world is not set in stone, but rather has to be constantly reiterated and renegotiated. To maintain their position beside the state, dozos actively stage their skills and demonstrate their numbers, as they did on November 30, 2014, after a nighttime dozo gathering that brought dozos from the Tchologo together in the town of Ouangolo. Instead of taking the most direct path to the forest, dozos took the longer way through the town center, resulting in over 250 armed dozos parading and demonstrating their strength in front of the police station.Footnote 24

The ceremony announced itself at the moment dozos began preparing gunpowder on the open space in front of our compound. Proudly, some of the dozos I knew posed with their guns and asked me to take their picture. Gradually, more and more dozos arrived by motorbike, and some of them put their guns in the chief hunter’s living room for safekeeping. The event itself was impressive. In the afternoon, the dozos gathered in one of the schoolyards, displayed medicine for sale, and performed magic. At night, griots and other singers praised the dozos and their deeds, and once in a while blank shots were fired into the night.

The next morning, the dozos had a visit from the mayor and the prefect (Figure 2). The mayor, who was supported in his election by the chief of the Ouangolo hunter association, came in a boubou. The prefect arrived in a long-sleeved track suit with a baseball cap and slippers. On this Sunday morning, they did not display any symbols of state. They appeared in casual wear, emphasizing that they had primarily come as friends of the chief of Ouangolo’s hunters and less as representatives of the state. The hunters were happy to see them arrive and offered them seats next to the chiefs. Bards approached and praised all the dignitaries. Many dozos took pictures with their phones, some crouched next to the mayor and the prefect to take a snap for themselves. The two visitors offered money as a gift to the chief. The dozo chief asked one of his own to fire a salute.

Figure 2. The prefect and the mayor greet the dozos after the nightly gathering. Mayor (second from left standing) prefect (third from left standing) and Domba Ouattara, the chief hunter of Ouangolo, (fourth from left standing). Photo by Author.

The prefect, a Senufo man, addressed the dozos in Jula. Even if his outfit was casual, he used this opportunity to share his views on how dozos and the state should collaborate. First, he praised the brotherhood and the chief’s teachings. Then, he emphasized that whereas the dozos’ original home was the wilderness, this had now changed, and dozos were welcome in town. He recounted how during the recent violent crisis the state armed corps abandoned this part of Côte d’Ivoire, and that things were done differently during that time. But now, with the return of the state, it was important that security work be done intelligently and cooperatively. He admitted that the state was unable to provide security for farmers and their produce in the countryside and that there was a need for dozos. But he also stressed that there were certain rules that dozos must respect. For instance, they should not keep prisoners or beat young adults. By way of conclusion, he said that he was satisfied with the way the dozo chief collaborated with them, and he invited dozos from other districts to do the same. At this point, he sent greetings to the Tchologo dozo chief, Mamadou Coulibaly.

During this period, the Ebola hemorrhagic virus was devastating the neighboring countries of Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone. The prefect warned dozos to no longer hunt game.Footnote 25 Instead of subserviently agreeing, the dozo chief jumped up and said that he did not like politics, nor theft, but as a hunter, it was difficult for him not to kill game in the wilderness. Many dozos laughed and agreed with him. The prefect said that he appreciated the sincerity with which the chief expressed his views and that this provided a good basis for their friendship. Nevertheless, he stressed how Ebola was a more dangerous disease than others with which they were familiar and that measures would be taken to isolate any village if the disease should be identified there. Following an exchange of blessings, the mayor and prefect departed. It is perhaps not inconsequential that no cases of Ebola were reported in Côte d’Ivoire.

After this visit, it was time for the dozos’ ritual forest gathering. However, according to the dozos in Ouangolo, before entering the forest, they would always first march through the heart of town and fire salutes at different places in a particular direction. The reason for this was secret, I was told. Instead of taking the direct path into the forest, dozos took a longer route through the town center. Roughly 250 armed dozos paraded in a single line through town (Figures 3 and 4). At the front were dozo bards or griots. Some dozos from Ouangolo fired into the air from time to time. Passers-by stopped to watch, but few of the general population lined the streets. They mostly continued their business as usual, as if this were a common sight. A few young children, however, walked excitedly with the dozos for a while. The hunters’ column turned at the market and marched past the police station (Figure 5). The head of the police, together with some of his corps, stood in front of the station and watched them pass. Their role seemed temporarily reduced to being merely passive stage props. At the major crossroads, the traffic came to a halt. The dozos’ vanguard signaled to cars to slow down so that the column could pass in silence. Drivers waited patiently when they saw the marching men were dozos. A youngster on a motorbike who did not stop immediately was beaten by one of the dozos who had joined the rebellion at the time. Some youngsters watching laughed, others shrugged their shoulders and turned their heads to show they were minding their own business. After the dozos’ procession had gone around full circle, they left the main road and disappeared into the forest (Figure 6).

Figure 3. The head of the dozo procession. Photo by Author.

Figure 4. Dozos during the procession with typical attributes. Photo by Author.

Figure 5. The procession in front of the police station in Ouangolo. Photo by Author.

Figure 6. Dozos firing into the air, as they leave the main road and enter the forest. Photo by Author.

Competition with the state

To facilitate their relationship with the state, the leading figures of the dozo brotherhood cultivate a friendly and respectful (but not subservient) relationship with local state agents, as the previous section illustrates. Some of these relationships are closer, while others are more distant. When I talked to police and gendarmes about dozos’ security work and the border checkpoint in Bemavogo, they were equally aware of dozo activities. In other words, the local state knows about it, but does not see any need to stop dozo activities, at least for the time being. Whereas some agents keep their distance from dozos, others have a closer relationship and frequently consult them for information or involve them in particular security missions. In general, though, this collaboration is more hidden.

It is not easy for state agents to publicly express support for dozo activities. For official events, such as the New Year greeting ceremony at the prefecture, for instance, dozos are not invited, although all other socio-professional groups send their representatives (Heitz-Tokpa & Mori Reference Heitz Tokpa and Mori2017). Via informal conversations, gendarmes and policemen expressed two coexisting but not necessarily opposing views concerning the role of dozos and their collaboration with the state. The first view expressed is rather normative (see also Traoré Reference Traoré2004). For example, one respondent stressed that dozos are hunters, and that what they were doing was illegal and simply a remnant of the violent crisis that would soon be eliminated. This view downplays the role that dozos have played in this part of the country since the 1990s, but also in earlier times as warriors and founders of villages. The second view is more practical and conciliatory. For example, one respondent insisted that whereas the activities of dozos lacked a statutory or judicial basis, at the same time dozos were a useful auxiliary force due to their local knowledge. Dozos, like any other locals, know better who is who, and often provide indispensable information to state agents originating from beyond the region seeking to understand and solve disputes. Between these two perspectives, what the state respondents tended to criticize most is the way dozos sometimes take things into their own hands, judging and punishing according to their own norms. Ideally, members of both camps felt dozos should hand over serious cases to the gendarmerie or police, so that the state can handle them according to standardized national procedures.

New security and control tasks for the dozos often emerge out of the absence or failure of state regulation, but also out of a dozo sense of business opportunity. Since late 2014, hunters in Ouangolo have checked the ownership of cattle at the towns’ slaughterhouse. This practice is linked to the frequent theft of cattle around Ouangolo. Increasingly, stolen cattle have been killed in rural areas and sold in town with the help of corrupt veterinarians who lend butchers their stamp. Every night, Ouangolo’s dozos patrol the outskirts of the town and inspect the brandings of cattle to be slaughtered at the abattoir in the morning. Public authorities are aware of this new practice and have tolerated the initiative so far. But cattle theft remains a big issue in Ouangolo. This again has raised doubts about the effectiveness of dozo security. Two cattle owners I talked to preferred not to lodge a complaint with either the police or dozos. They expressed the view that too many people benefit from the theft and the low price of meat in town, which is due to the collaboration of different actors, including shepherds, butchers, veterinarians, state officials, and even some dozos.

Another example is telling in this regard. For some time in early 2014, dozos had a checkpoint behind the railway station at the entrance to Ouangolo. Every Sunday—market day in Ouangolo—farmers use this road to bring their produce to the market for sale. Dozos, as well as traders, positioned themselves behind the rails to buy produce from the passing farmers. The group of traders stopped farmers arriving on motorbikes and bought beans, game, and other products for a lower price than what they would pay in the market. The traders even had a pair of scales with them. As a result, the mayor’s office was unable to earn taxes on these products or on the exchange. Fifty meters closer to the town, the passing farmers were stopped again, this time by dozos who asked them for money to buy tea. After some months, though, the market disappeared. According to the police, civilians lodged a complaint about the roadblock at the local police station. The chief of police called the chief dozo and prohibited dozos from maintaining a roadblock. This example illustrates the power differential in the relationship between dozos and the state. This could easily lead us to conclude that, to use Bellagamba and Klute’s typology, in this instance the dozos were “below” the state (Bellagamba & Klute Reference Bellagamba and Klute2008).

In the rural borderland, however, the power differential is slightly different. One of the leading dozos, the secretary, heard about a crossroads in the rural area on the way to Burkina Faso where two gendarmes were waiting to stop travelers and check motorbike insurance. A Burkinabé woman, an acquaintance of this dozo, who did not have Ivorian insurance, risked a fine of FCFA10,000/EUR15. To escort his friend, the secretary wore his complete dozo outfit with shirt and gun as usual, to demonstrate his status and power in the rural sphere. In his eyes, the rural world and this dirt road belonged to dozos. At the beginning of the dirt road, there was even a dozo checkpoint. When the dozo secretary reached the gendarmes, he stopped and greeted them, explaining that he had come to accompany some visitors (I was among them). The woman was not checked, and nor were the other two travelers who had joined us. The example shows how dozos perform their power in rural areas in subtle or overt ways. This particular dozo demonstrated (empowered also perhaps by my presence) that he also had authority, beside the state. The dozo brotherhood did not, however, have the power to dissolve the gendarmes’ checkpoint, or at least, they did not wish, this time, to push their mutual competition for security work and access to road tolls too far.

Conclusion

Just as in other violent conflicts in West Africa, the decade-long crisis in Côte d’Ivoire strengthened the position of dozos. Nevertheless, after the civil war’s conclusion, dozos had to cede urban spaces and main roads in Ouangolo back to the returning state administration. As the state was infused with legality and legitimacy, it had a lopsided capacity in this renegotiation (Hagmann & Péclard Reference Hagmann and Péclard2010). Hunters were evicted from the urban sphere—the more profitable strategic points—and asked to restrict their activities to the wilderness, their “original” sphere, so to speak. This is indicative of the power differential between dozos and the state. For some activities, as shown in the example with the prohibition to export cashew nuts, dozos collaborated as an auxiliary force with the state.

It would be insufficient, however, to describe hunters as “below” the state in post-conflict Ouangolo. Dozos operate quite autonomously in large rural areas—thanks to the profitable border trade—where they have their own sources of income, even if they are less profitable than those of the state.Footnote 26 Moreover, dozos and their transnational networks can more easily cross the border and operate in a neighboring state in collaboration with local dozos. Hence, although dozos perform security work beside the state, they also operate beyond the state and thereby have a larger room to maneuver in the local arena than the state, which is constrained by its territorial boundaries (Bellagamba & Klute Reference Bellagamba and Klute2008).

As the example from the border village of Bemavogo shows, rural chiefs—many of them dozos themselves—and dozos from the hunters’ association govern the rural borderlands. In this area which has been more or less abandoned by the state, they seek to secure the population with the help of the brotherhood, resolve conflicts, and improve facilities. Though far from ideal, dozo operations in Ouangolo have managed to create a self-sufficient, autonomous security governance system with its own measures of sanctioning, which is parallel to and apart from the state’s structure. Contrary to the dozo/state relationship in northwestern Côte d’Ivoire in the 1990s, dozos in the post-conflict Ouangolo rural borderlands do not report to the state. They have a much more autonomous and assertive position beside the state.

Confrontations over authority between hunters and the state frequently occur in spaces that are on the threshold between the rural and urban spheres, as demonstrated by the example of the market and the rural checkpoint of the gendarmes. In negotiating access to strategic areas, dozos use repertoires and symbols of the hunter society, displaying their distinct attire and weaponry. In the realm of art and ritual, dozos are able to manifest their claim for power more openly. When parading through the heart of a town, dozo performativity is marked by skill and strength in numbers, subtly encroaching upon the urban space generally attributed to the state. Dozo performances demonstrate that Mande hunters have gained an urban foothold and reveal how hunter fraternities are likely to sustain their regulatory power in northern Côte d’Ivoire for some time to come.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Prof. Dr. Gregor Dobler, Department of Social and Cultural Anthropology, University of Freiburg in Germany, the principal investigator of the project “Constraints and creativity on African State Boundaries in Africa” and our Ivorian partner Dr. Dabié D. A. Nassa, Institut de Géographie Tropicale, Félix-Houphouët-Boigny University of Cocody, Côte d’Ivoire. The project was part of the Priority Program 1448 of the German Research Foundation “Adaptation and Creativity in Africa: technologies and significations in the making of order and disorder” that allowed me to conduct research in northern Côte d’Ivoire. I am particularly grateful to my hosts and research participants in Ouangolo. Many thanks to Prof. Dr. Till Förster for regular inspiring conversations and comments on my article. I also acknowledge the helpful criticism of anonymous reviewers and wish to thank the editors of the journal for their guidance and edits. I would like to thank also the DELTAS Africa Initiative [Afrique One-ASPIRE/DEL-15-008] and the Centre Suisse de Recherches Scientifiques en Côte d’Ivoire for supporting my research career.