Mental disorder and learning disability often occur together (Reference Eaton and MenolascinoEaton & Menolascino, 1982; Reference WrightWright, 1982; Reference Sovner and HurleySovner & Hurley, 1983; Reference Campbell and MaloneCampbell & Malone, 1991). There is contemporary interest in diagnostic classification, for example the Psychiatric Assessment Schedule for Adults with Developmental Disability (PAS—ADD; Reference Moss, Ibbotson and ProsserMoss et al, 1997) and the diagnostic criteria for psychiatric disorders for use with adults with learning disabilities/mental retardation (DC—LD; Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2001), but validated rating scales are unavailable. Adaptations to the Beck Depression Inventory, Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale and Children's Depression Inventory have been reported (Reference Kazdin, Matson and SenatoreKazdin et al, 1983; Reference Benavidez and MatsonBenavidez & Matson, 1993; Reference Lindsay, Michie and BatyLindsay et al, 1994; Reference MeinsMeins, 1995), but reliability data are variable. More fundamentally, this approach to validation has been criticised (Reference Sturmey, Reed and CorbettSturmey et al, 1991) because some symptoms of depression commonly presented by those with learning disabilities may not be expressed by the general population, and other symptoms of depression may be seldom experienced (Reference Cooper and CollacottCooper & Collacott, 1994; Reference MeinsMeins, 1995; Reference Moss, Emerson and KiernanMoss et al, 2000).

METHOD

Our primary aim was to develop a valid and reliable depressive-symptom rating scale for assisted self-completion by individuals with mild to moderate learning disability. The study followed a series of stages. First, an item pool was developed from existing schedules; second, focus groups were consulted to guide the refinement of items into a conceptual and linguistic form accessible to people with learning disabilities; third, a draft scale was developed with a suitable response format; fourth, the draft scale was piloted and improved; and fifth, the scale was subjected to extensive field testing and psychometric analysis. A secondary aim was to develop a supplementary measure, for completion by a carer, and to compare the properties of the two measures.

Development of the item pool

We reviewed the content of existing diagnostic schedules and symptom scales to identify a descriptive pool of items. Our intention was to represent the breadth of depressive symptoms commonly reported, while keeping in mind our goal of developing a brief measure. We took, as our starting point, the depression sub-scale from the recently developed DC—LD (Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2001). The DC—LD has been specifically developed for use in learning disability and contains items not included in diagnostic schedules developed for the general population. Seventeen items were taken from this schedule and an additional four, non-overlapping, items were taken from ICD-10 (World Health Organization, 1994) and DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 1994). Several published depression scales were also reviewed: the Beck Depression Inventory - II (BDI-II; Reference Beck, Steer and BrownBeck et al, 1996), the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (Reference HamiltonHamilton, 1960) and the Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale (Reference ZungZung, 1965). From these, seven further items were added to the pool, making 28 items in total.

Focus groups

Twelve people with mild-to-moderate learning disability (mild, n=8; moderate, n=4) participated in the focus groups. There were six men and six women, aged 26-60 years (mean 42.25 years, s.d. 10.31). Mean age equivalent for receptive verbal comprehension on the British Picture Vocabulary Scale (BPVS; Reference Dunn, Dunn and WhettonDunn et al, 1997) was 8.95 years (s.d. 1.90). Participants were divided into two groups of six.

Our aim was to observe the type of language and expression commonly used to describe affect. Participants were given pictorial presentations of emotional events and facial expressions and were asked to discuss what was happening and how the people involved might be feeling. Facial expressions were taken from the Boardmaker computer program (Mayer-Johnson Inc., Solana Beach, CA, 1997) and pictorial images from the Life Horizons 35-mm slide set (Reference KemptonKempton, 1988). We followed published procedures for running focus groups and analysing resultant data (Reference MorganMorgan, 1993). A facilitator assisted the group to focus on tasks and interact when the situations were discussed. Both groups were audiotape-recorded and the proceedings transcribed. Transcribed material was reviewed and each word used to describe an emotion was logged and its frequency counted. The most frequently occurring words relating to depressive symptoms were subsequently used to compose adapted questions reflecting the content of the pool items. Examples for the emotion ‘sad’ included ‘sad’, ‘crying’, ‘upset’, ‘low’, ‘down’ and ‘miserable’; words for ‘happy’ included ‘happy’, ‘pleased’, ‘smiling’ and ‘in a good mood’. Such information helped us to generate appropriate phrasings for items.

Development of the response format

In constructing the draft scale, several response options were considered. Lindsay & Michie (Reference Lindsay and Michie1988) found a two-choice format (i.e. presence or absence of symptoms) to have higher test—retest reliability than a four-choice format in this population. However, we felt that dichotomies were unlikely to be sensitive to changes in specific symptoms over time, and might lead some people with learning disability to respond perseveratively, or in an acquiescent manner (Reference FlynnFlynn, 1986). A three-point format was therefore selected, in which the responses were ‘never/no’ (0), ‘sometimes’ (1), and ‘a lot/always’ (2) (note that some items were reverse rated). However, we decided to retain the option of presenting items in two stages: the first requiring a ‘yes/no’ answer indicating the presence or absence of the symptom in question, and the second requiring an indication of the severity of the symptom if present (‘sometimes’ or ‘a lot/always’). To combat possible acquiescence and to overcome expressive language problems, symbols were also available to represent each answer (Reference Kazdin, Matson and SenatoreKazdin et al, 1983). Participants were encouraged to point to the symbol that best described how they felt. All symbols were presented on 15 cm × 10 cm card with the word in large print (36 point) and the symbol (from Boardmaker) occupying a sizeable proportion of available space; ‘yes’ was a large white tick on a black background; ‘no’ a large black cross on a white background; ‘sometimes’ a small black ‘puddle’ mark on a white background; and ‘always’ a large black ‘puddle’ mark on a white background. A screening process was also developed to assess understanding of the response terms. This included a series of factual questions, unrelated to the scale, to test the respondent's ability to discriminate reliably between ‘yes’ and ‘no’ (e.g. ‘Do you live in Scotland?’) and between ‘sometimes’ and ‘always’ (e.g. ‘Do you have fish for tea?’) and to understand the symbols (e.g. ‘Which card means “always”?’) (Further details available from the authors upon request.) Finally, it was decided to ensure that the scale reflected ‘present state’ symptoms by presenting each question in terms of how the person had felt in the previous week. This was achieved by establishing an ‘anchoring’ event which had occurred 1 week before.

RESULTS

Piloting the draft measure

Three individuals with learning disabilities and depression (2 males, 1 female) and three with learning disabilities without depression (1 male, 2 females) completed the draft Glasgow Depression Scale for people with a Learning Disability (GDS—LD) to check the clarity of each question and of the response requirements. The instructions were explained and questions read aloud. Three of these six participants did not require symbol aids. However, piloting resulted in eight items being removed from the GDS—LD. Five items were removed because participants required extensive explanation, and even simplified versions remained unclear (‘I feel as if I have failed/not done well’, ‘I have felt guilty/felt that things happen because of me’, ‘I have felt as if I am being punished/as if I deserve to feel sad’, ‘I have felt as if I am worthless/as if I am not worth bothering about’, ‘I ask other people whether I am doing things properly/right’). One item was removed because participants reacted negatively to it (‘I shout at other people or hit other people’); another because all participants responded ‘sometimes’, i.e. it did not discriminate (‘I have had a headache or other aches and pains’); and yet another because it was misunderstood and could not be distinguished from questions concerning sleep difficulties (‘I have felt tired or weak’). The remaining 20 items, therefore, were retained, although some rewording took place to improve understanding (see Appendix 1).

Field testing and psychometric development

Three experimental groups were included in this part of the study: people with learning disabilities and depression, identified consecutively from learning disability psychiatry clinics; people with learning disabilities but no depression, identified as age- and gender-matched controls through local day centres; and people without learning disabilities but with depression, identified through clinical psychology outpatient clinics. The learning-disability non-depression group was required to ascertain discriminant validity of the GDS—LD, and the non-learning-disability depression group was required to permit criterion measurement against which to validate the GDS—LD. Two carers for people with learning disabilities were also required to evaluate interrater reliability of the Carer Supplement to the GDS—LD (GDS—CS).

Participants

Clinicians and day centre staff were provided with guidelines detailing the following inclusion and exclusion criteria. For the learning-disability depression group, participants had to have mild-to-moderate learning disability with reasonable verbal comprehension, an ability to communicate verbally and a current clinical diagnosis of depression. Criteria for the learning-disability non-depression group were similar, although individuals were required not to have a current diagnosis of depression. Individuals were also excluded if they had a diagnosis of autism or dementia. Criteria for inclusion in the non-learning-disability depression group comprised current attendance at adult mental health services and a current clinical diagnosis of depression according to DSM-IV criteria.

Once participants had been identified and had consented to take part, their carers were interviewed, during which the Mini-Psychiatric Assessment Schedule for Adults with a Developmental Disability (Mini-PAS—ADD; Reference Prosser, Moss and CostelloProsser et al, 1996) was completed. This is a standard assessment for evaluation of psychiatric disorder in people with a learning disability, and was used to confirm that individuals with learning disability had been allocated to the correct groups. All participants were so confirmed. Of the 40 people with learning disability who were approached to take part, two of their carers refused involvement and gave no reason for this. This left 19 people in the learning-disability depression group (10 male, 9 female; mean age 40.21 years, (s.d.=12.20) and another 19 in the learning-disability non-depression group (10 male, 9 female; mean age 39.11, s.d.=9.31). British Picture Vocabulary Scale age equivalents were similar across these groups: 15 people with mild and 4 with moderate learning disability, BPVS mean 9.28 years (s.d.=1.80) in the depression group v. 10 people with mild and 9 with moderate learning disability, BPVS mean 9.18 years (s.d.=2.06) in the non-depression group. There was no significant difference between the depression and non-depression learning-disability groups in terms of age, gender, degree of disability or BPVS results. For the non-learning-disability depression group, 27 patients were recruited (12 male, 15 female; mean age 43.89 years, s.d.=13.41). These participants did not differ significantly from the participants with learning disabilities in age or gender distribution.

Validity

Content validity The method so far supports the content validity of the GDS—LD. Furthermore, none of the 20 retained items was assigned a score of 0 (or 2 if reverse rated) by more than half of the learning-disability depression group, suggesting that the content was appropriate to their experience.

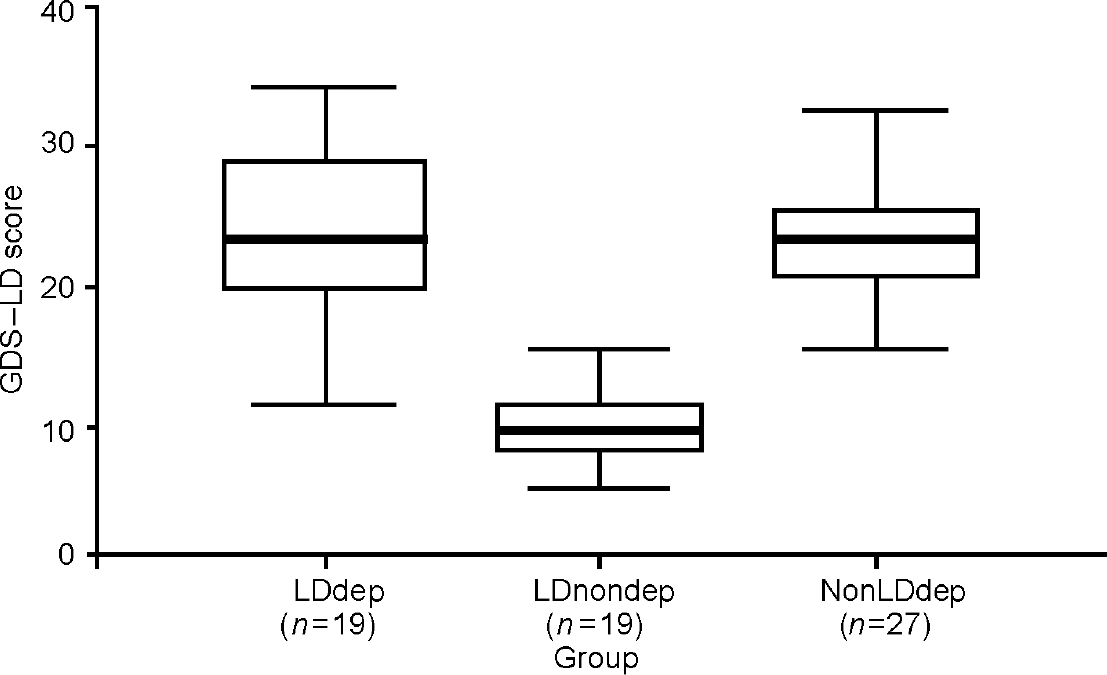

Discriminant validity Preliminary checks of skewness and kurtosis verified that our data were suitable for parametric analysis. The ability of the GDS—LD to discriminate between the three experimental groups is illustrated in Fig. 1. Inspection of these data suggests that the scale discriminates effectively between the depression and non-depression groups in terms of levels of depression reported. This was confirmed by one-way analysis of variance (F=44.45; d.f.=2; P < 0.001) and a Scheffé post hoc test (P < 0.05) demonstrated that there was a significant difference between the depression (mean 23.37, s.d.=6.3) and non-depression (mean 9.26, s.d.=2.94) learning-disability groups. Participants in the non-learning-disability depression group obtained scores similar to counterparts with learning disability and depression (mean 22.48, s.d.=5.77) and significantly higher than those with learning disability who were without depression (Scheffé test, P < 0.05).

Fig. 1 Comparison of the three participant groups in terms of total scores (mean and range) on the Glasgow Depression Scale for people with a Learning Disability (GDS—LD). LDdep, learning-disability depression group; LDnondep, learning-disability non-depression group; NonLDdep, non-learning-disability depression group. Error bars are added.

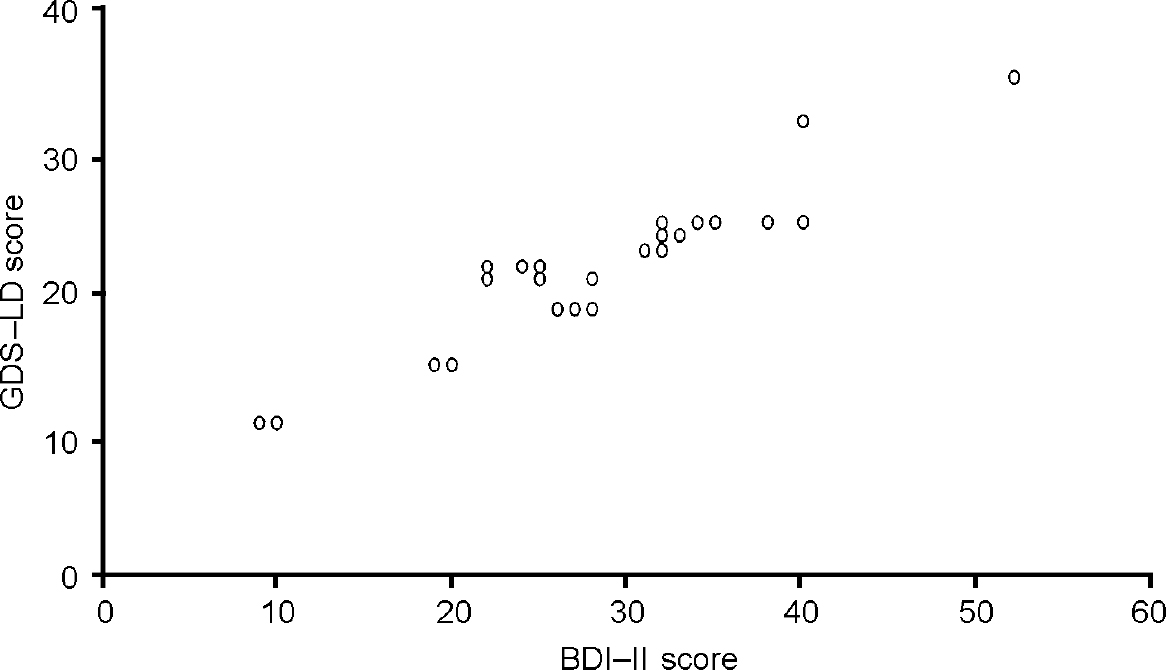

Criterion validity To investigate criterion validity, the 27 participants in the non-learning-disability depression group completed both the GDS—LD and the BDI—II. A scatterplot of the relationship between scores on these measures (Fig. 2) demonstrates a strong linear relationship with no outlier cases. Data were analysed using the product moment correlation, which yielded r=0.94, P < 0.001, signifying excellent criterion validity. Retaining only those items that have no overlap with the BDI—II (items 5, 16-20) this correlation remained strong (r=0.84; P < 0.001).

Fig. 2 Scatterplot of scores on the Glasgow Depression Scale for people with a Learning Disability (GDS—LD) and the Beck Depression Scale Inventory — II (BDI—II) for the group of participants with depression but no learning disability (n=27).

Reliability

Test—retest reliability We measured test—retest reliability by administering the GDS—LD at the beginning and the end of assessment sessions with all the participants with learning disabilities (n=38). In between these presentations of the GDS—LD the BPVS was administered and the participant was engaged in general conversation. Test—retest reliability was found to be high (r=0.97; P < 0.001) and it remained strong when recalculated using only the scores from participants with depression and learning disabilities (r=0.94; P < 0.001, n=19).

Internal consistency Internal consistency was assessed by calculation of Cronbach's α, which revealed highly satisfactory values. A value of α=0.70 or above is considered to be acceptable (Reference NunnallyNunnally, 1978). Alpha was 0.90 for the total scale (n=38), with the range in internal consistency, as measured by α if item deleted, being 0.89 to 0.91 (mean 0.90). When n=19 (the learning-disability depression group only), α remained satisfactory at 0.81, with a range of 0.77 to 0.82 and a mean α if item deleted of 0.80. Mean item—total correlation was calculated at 0.38.

Sensitivity and specificity

Sensitivity and specificity values for several cut-off points on the GDS—LD were also calculated. Sensitivity refers to the ability of the scale to identify correctly all those who belong to a particular group (in this case people with depression) and specificity refers to the likelihood of people outwith the group (those without depression) being wrongly included. We suggest that a score of 15 on the GDS—LD is optimal if the intention is to exclude those who are not depressed (specificity 100%). This score also yielded acceptable sensitivity (90%). However, it might be clinically more important to identify more people with possible depression than to avoid false-positive results. Using a score of 13 as the cut-off point increased the sensitivity to detect individuals with depression to 96%, decreasing specificity to a still-acceptable 90%. We found that a cut-off of 10 would detect 100% of those with depression, but at this point specificity dropped considerably, to 68%. In light of the importance of detecting those with depression, without wrongly identifying those not depressed, 13 might be advisable as the cut-off point for screening purposes.

The Carer Supplement

The principal contribution that carers can make to the assessment of depression is to report their direct observations and concerns. The development of the GDS—CS was an attempt to do this in a systematic way. It was developed by first asking three clinical psychologists working in learning disabilities to indicate independently which items of the GDS—LD they felt were overtly observable. The 16 items unanimously selected were then included in a draft scale (see Appendix 2). Second, the GDS—CS was piloted using six carers (four family members, two paid carers) of people with learning disability (three with depression, three without depression). The carers were asked to give their opinion regarding ease of understanding and completion. No item needed to be altered at this stage. Third, the GDS—CS was administered independently to two carers for each of the participants in our learning-disability groups (76 carers). To avoid situational influences, in each case carers were either both paid carers, or both family members. Items were screened for relevance, but no item was scored 0 by more than half of the carers of participants with depression. No item had to be removed under this criterion, highlighting the content validity of the GDS—CS. Fourth, test—retest reliability after a delay of approximately 2 days was computed using the principal carer of each participant, and was found to be high (r=0.98; P < 0.001, n=38) for the total group, and similarly high for the depression group alone (r=0.94; P < 0.001, n=19). Inter-test reliability between the GDS—LD and the GDS—CS was also high (r=0.93; P < 0.001, n=38): for the learning-disability depression group r=0.87 (P < 0.001, n=19). Interrater reliability between all pairs of carers (38 pairs) was calculated at r=0.98 (P < 0.001), and for carers of people with depression (19 pairs) r=0.93 (P < 0.001). Internal consistency assessed using Cronbach's α was 0.88 for the total scale (n=38); the range in internal consistency, measured by α if item deleted, was 0.86 to 0.90 (mean 0.88).

DISCUSSION

We felt that a measure specifically designed to describe and quantify depressive symptoms in adults with mild-to-moderate learning disabilities was required. We would argue that our methodology and findings provide preliminary support for the validity of the GDS—LD. Items were drawn from a recent diagnostic schedule (the DC—LD), supplemented by items from other standard scales, and were ratified and adapted through qualitative work within focus groups. The draft version of the scale then went through a series of iterations using quantitative scale development methods. The Carer Supplement, designed to assess observable components of depression, was also subjected to considerable field testing. We suggest therefore that the face and content validity of the GDS—LD and the GDS—CS are acceptable. The scales were also able to discriminate effectively between depression and non-depression groups, allocated on the basis of Mini-PAS—ADD results and consultant psychiatrists' clinical judgement, and the GDS—LD correlated highly with the BDI—II scores of people with depression but without learning disabilities, suggesting that the same construct was being measured by the two scales. Our suggested cut-off scores for screening of clinically significant symptom levels require replication, however, and we would point out that our scales are not proffered as diagnostic measures.

Our findings also demonstrate that the GDS—LD and the GDS—CS are internally consistent and have good test—retest reliability. Inter-test reliability between the patient and carer versions was also high, suggesting that the GDS—CS might be used to assess non-verbal or non-compliant individuals. Interrater reliability between carers was also high, although this result is based solely upon care provision within the same setting. It would be interesting, therefore, to administer the GDS—CS independently to family carers and to staff carers and to compare the scores obtained, and to consider ‘inter-administrator reliability’ on the GDS—LD (F.M.C. administered this test to all participants with learning disabilities in our study).

The GDS—LD took 10-15 min to administer, depending on the ability and cooperation of the respondent. It is simple to use and we do not feel that it requires special training. The three-point response format caused no problems; indeed, some participants readily understood the ordinal scale of ‘never/no’, ‘sometimes’ and ‘always/a lot’, suggesting that they were familiar with such concepts. The option of presenting the scale first as a dichotomy of ‘yes/no’, and thereafter following an affirmative response as ‘sometimes’ or ‘always/a lot’, appears to make the GDS—LD accessible to most people with mild-to-moderate learning disability. Test—retest data suggest consistency in responding, although we recommend that this should be repeated over a longer interval. The GDS—CS can be completed in less than 5 min. Finally, it should be noted that the GDS—LD and GDS—CS are ‘present state’ tools that gauge symptom level across a 1-week period. This was our intention, for two reasons. First, we were uncertain of the accuracy of obtaining patient report over longer intervals; and second, it permits use of the scales as measures both of process and outcome. In relation to the latter, a longer-term study using trials methodology is required to investigate change over time on the GDS—LD and GDS—CS.

Clinical Implications and Limitations

CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS

-

▪ The Glasgow Depression Scale for people with a Learning Disability (GDS—LD) and its Carer Supplement (GDS—CS) are quick and easy to use, and might be suitable for administration by a range of professionals working with people with learning disability.

-

▪ The scales might be applicable to population screening, as well as to symptom monitoring and evaluation of change. For example, the GDS—LD and GDS—CS might be used as screening tools to guide staff in making better-informed referral decisions.

-

▪ The GDS—LD provides a means of engaging patients in dialogue about their needs and treatment, and the GDS—CS might serve a similar function for carers.

LIMITATIONS

-

▪ The conceptual basis of the GDS—LD is limited, largely because of the lack of validated models of depression in people with learning disability. Its ability to distinguish symptoms of depression from symptoms of other mental health problems such as anxiety was not evaluated.

-

▪ The study samples were small. It would be valuable to re-evaluate the psychometric properties of the GDS—LD in a larger group, and to compare results for respondents with mild v. moderate learning disability.

-

▪ Test—retest reliability was assessed in a preliminary manner, owing to time constraints. This should be repeated with a longer interval between testing sessions. Similarly, although the GDS—CS has been shown to be a useful adjunct to the GDS—LD, its stability across care settings requires to be demonstrated.

APPENDIX 1

Glasgow Depression Scale for people with a Learning Disability (GDS—LD)

Preparatory instructions

‘Hello. My name is.... I would like to talk to you about how you have been feeling just recently. First, it would help if you could tell me something you did last... [provide day of the week]/about a week ago.’ [Provide prompts as necessary or ask a carer to identify an anchor event.]

| In the last week... | Never/no | Sometimes | Always/a lot | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Have you felt sad? | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Have you felt upset? | ||||

| Have you felt miserable? | ||||

| Have you felt depressed? | ||||

| 2 | Have you felt as if you are in a bad mood? | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Have you felt bad-tempered? | ||||

| Have you felt as if you want to shout at people? | ||||

| 3 | Have you enjoyed the things you have done? | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Have you had fun? | ||||

| Have you enjoyed yourself? | ||||

| 4 | Have you enjoyed talking to people and being with other people? | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Have you liked having people around you? | ||||

| Have you enjoyed other people's company? | ||||

| 5 | Have you made sure you have washed yourself, worn clean clothes, brushed you teeth and combed your hair? | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Have you taken care of the way you look? | ||||

| Have you looked after your appearance? | ||||

| 6 | Have you felt tired during the day? | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Have you gone to sleep during the day? | ||||

| Have you found it hard to stay awake during the day? | ||||

| 7 | Have you cried? | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| 8 | Have you felt you are a horrible person? | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Have you felt others don't like you? | ||||

| 9 | Have you been able to pay attention to things (such as watching TV)? | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Have you been able to concentrate on things (like television programmes)? | ||||

| What is your favourite [television programme]? Are you able to watch it from start to finish? | ||||

| 10 | Have you found it hard to make decisions? | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Have you found it hard to decide what to wear, or what you would like to eat, or do? | ||||

| Have you found it hard to choose between two things? [Give concrete example if required.] | ||||

| 11 | Have you found it hard to sit still? | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Have you fidgeted when you are sitting down? | ||||

| Have you been moving about a lot, like you can't help it? | ||||

| 12 | Have you been eating too little? | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Have you been eating too much? | ||||

| Do people say you should eat more/less? | ||||

| [Positive response for eating too much OR too little is scored.] | ||||

| 13 | Have you found it hard to get a good night's sleep? | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| [Ask questions to clarify information. If a positive response is given to one of the following, score positively.] | ||||

| Have you found it hard to fall asleep at night? | ||||

| Have you woken up in the middle of the night and found it hard to get back to sleep? | ||||

| Have you woken up too early in the morning? [Clarify time.] | ||||

| 14 | Have you felt that life is not worth living? | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Have you wished you could die? | ||||

| Have you felt you do not want to go on living? | ||||

| 15 | Have you felt as if everything is your fault? | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Have you felt as if people blame you for things? | ||||

| Have you felt that things happen because of you? | ||||

| 16 | Have you felt that other people are looking at you, talking about you, or laughing at you? | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Have you worried about what other people think of you? | ||||

| 17 | Have you become very upset if someone says you have done something wrong or you have made a mistake? | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Do you feel sad if someone tells you.../gives you a row? | ||||

| Do you feel like crying if someone tells you.../gives you a row? | ||||

| 18 | Have you felt worried? | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Have you felt nervous? | ||||

| Have you felt tense/wound up/on edge? | ||||

| 19 | Have you thought that bad things keep happening to you? | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Have you felt that nothing nice ever happens to you any more? | ||||

| 20 | Have you felt happy when something good happened? [If nothing good has happened in the past week] | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| If someone gave you a nice present, would that make you happy? |

‘I am going to ask you about how you have been feeling since [state anchor event last week]. Just between... and now, OK. There is no right or wrong answer — I just want to know how you have been feeling. If I don't explain things well enough, just ask me to tell you what I mean. We will be using the pictures we looked at before.’ [Recap on the meanings of these.]

Administrative instructions

Each question should be asked in two parts. First, the participant is asked to choose between a ‘yes’ and ‘no’ answer. Use the symbols, if necessary. If their answer is ‘no’, the score in that column (‘0’ or ‘2’) should be recorded. If their answer is ‘yes’, they should be asked if that is ‘sometimes’ or ‘always’, and the score recorded as appropriate. Some respondents will be able to use the three-point scale from the start, others might learn the ‘rules’ as you proceed.

Supplementary questions (italics) may be used if the primary question is not understood completely. If a response is unclear, ask for specific examples of what the participant means, or talk with them about their answer until you feel able to allocate it to a response category.

APPENDIX 2

Carer Supplement to the Glasgow Depression Scale for people with a Learning Disability (GDS—CS)

What is the name of the person you look after? [UNK]

| In the last week... | Never/no | Sometimes/a little | Always/a lot | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Has X appeared depressed? | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| 2 | Has X been more physically or verbally aggressive than usual? | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| 3 | Has X avoided company or social contact? | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| 4 | Has X looked after his/her appearance? | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| 5 | Has X spoken or communicated as much as he/she used to? | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| 6 | Has X cried? | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| 7 | Has X complained of headaches or other aches and pains? | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| 8 | Has X still taken part in activities which used to interest him/her? | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| 9 | Has X appeared restless or fidgety? | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| 10 | Has X appeared lethargic or sluggish? | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| 11 | Has X eaten too little/too much? | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| If no problem, score 0. (A positive answer to either question means it should be scored. Please tick which response is relevant, beside the question.) | ||||

| 12 | Has X found it hard to get a good night's sleep? Please also tick which one of the following options is relevant. | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Has X had difficulty falling asleep when going to bed at night? □ | ||||

| Has X been waking in the middle of the night and finding it hard to get back to sleep again? □ | ||||

| Has X been waking very early in the morning and finding it hard to get back to sleep? □ | ||||

| 13 | Has X been sleeping during the day? | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| 14 | Has X said that he/she does not want to go on living? | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| 15 | Has X asked you for reassurance? | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| 16 | Have you noticed any change in X recently? Please explain what changes you have noticed, in either mood or behaviour[UNK] | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| [UNK] | ||||

| [UNK] |

[referred to as ‘X’ in the following questions]

What is your relationship to X? [UNK]

The following questions ask about how you think X has been in the last week. There is no right or wrong answer. Please circle the answer you feel best describes X in the last week.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.