Liaison and diversion are concerned with the identification, assessment and screening of offenders with mental health problems, learning disabilities,Footnote a substance misuse and other vulnerabilities and their referral for appropriate treatment or support. The aim of liaison and diversion services is to identify such problems at the individual's very first contact with any part of the judicial process. There have been a number of significant developments in terms of policy, legislation and the development and standardisation of liaison and diversion services across the UK since Advances first published an article on diversion from custody (Reference BirminghamBirmingham 2001). The current article provides an update on developments in this field over the past 15 or so years by examining the impact of changes in policy and legislation and exploring the development and evaluation of diversion initiatives.

Policy context for liaison and diversion

There has been a significant change in the policy context surrounding liaison and diversion services, with an increasing interest from government. In line with this shift, NHS England has a section of its website dedicated to liaison and diversion services, which includes a regular newsletter that can be subscribed to for more updates (aNHS England 2016a).

There have been a number of reviews of the criminal justice system (Box 1). Baroness Corston, for example, considered the treatment of women (Home Office 2007). She found that women were proportionately more likely than men to be detained in custody and had higher rates of mental illness. Her report also identified many deficiencies in the system that left women vulnerable and she advocated for earlier intervention to prevent women from being unnecessarily imprisoned. However, it is Lord Bradley's report, published in 2009, that has been the most important and influential by far. This called for a paradigm shift and it recommended a series of measures to divert mentally disordered people from, or support them within, the criminal justice system (Department of Health 2009a).

BOX 1 Timeline of reviews and government responses

-

1992: the Reed Report, reviewing health and social services for mentally disordered offenders (Department of Health and Home Office)

-

2002: Reducing Re-Offending by Ex-Prisoners (Social Exclusion Unit)

-

2007: The Corston Report, on the situation of vulnerable women in the criminal justice system (Home Office)

-

2009: The Bradley Report, on the situation of people with mental illness or learning disabilities in the criminal justice system (Department of Health)

-

2009: Improving Health, Supporting Justice (Department of Health)

-

2010: Breaking the Cycle: Effective Punishment, Rehabilitation and Sentencing of Offenders (Ministry of Justice)

-

2014: The Bradley Report Five Years On (Durcan, for the Centre for Mental Health)

The Bradley Report

Lord Bradley's report represents a watershed in the development of liaison and diversion services. He was asked to carry out a brief review focusing mainly on diversion from prison and established court services, but he ended up conducting a much more comprehensive review which looked at the whole offender pathway. Such a wide-reaching review was both necessary and timely. He identified that a full 16 years previously the Reed Report (Department of Health 1992) had recommended a nationwide system of court assessment and diversion schemes; however, many of those issues remained unaddressed and implementation had been inconsistent. Bradley did acknowledge that there had been policy developments that had made diversion much more acceptable and therefore likely to succeed. These included the identification of ex-offenders as a socially excluded population (Social Exclusion Unit 2002). The current challenge is to ensure that the momentum created by Bradley is maintained and service development followed up to ensure that his recommendations are actually implemented.

The report's recommendations

Bradley suggested that diversion should be regarded as a journey rather than an isolated event (Box 2). It should begin with the identification of vulnerable young people and the provision of appropriate interventions to identify mental illness earlier, to prevent criminal behaviour. He recommended a population-based approach. This included training a much wider range of individuals, such as teachers and primary healthcare staff, to identify mental illness before offences were committed. This would also link into other opportunities for early intervention, such as youth offending teams. The point of arrest and subsequent police custody was highlighted as a critical and previously underresourced stage for providing mental health input and diversion if necessary. Bradley recommended that all police suites should have access to liaison and diversion services. He said that these services should provide a range of supporting activities, including identifying the need for an appropriate adult, providing information for the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS), police and solicitors, and signposting to mental health services. Although such an approach, based on early intervention, has good face validity, additional evidence is required to prove its cost-effectiveness before further changes can be advocated.

BOX 2 What is ‘diversion’?

Lord Bradley described diversion as ‘A process whereby people are assessed and their needs identified as early as possible in the offender pathway (including prevention and early intervention), thus informing subsequent decisions about where an individual is best placed to receive treatment, taking into account public safety, safety of the individual and punishment of an offence.’

(Department of Health 2009a: p. 16)

Bradley made a number of recommendations about improvements to the way that mental health problems are dealt with by the court system, building on the liaison and diversion teams established by the Reed Report. He emphasised the need for these teams to work closely with the judiciary to ensure that they have adequate information about individual defendants, local services for mental illness and learning disability support. Other suggestions included the need to ensure high-quality, timely psychiatric reports to guide the court process, the increased use of specialist approved premises for bail as an alternative to custody, the use of specialist courts and enhanced training in mental health problems for probation services and the judiciary.

Moving further down the offender pathway to consider sentencing and custodial arrangements, Bradley saw areas for improvement here as well. The report highlighted that mental health treatment requirements (MHTRs) were seriously underused, representing only 725 out of 203 323 requirements issued under community orders (community sentences handed down by the courts) in 2006 (Reference Seymour, Rutherford and KhanomSeymour 2008). It recommended more research into the use of MHTRs as a potential way of avoiding custodial sentences. The report also made recommendations at each stage of the custodial process. These included ensuring that adequate screening for mental illness and learning disability is completed at reception, that any transfers to hospital under the Mental Health Act happen in a timely fashion and that released prisoners have adequate support for resettlement. Bradley also made recommendations about the need for robust primary mental healthcare provision, which could lead to the refocusing of in-reach secondary services on the most unwell prisoners.

Bradley identified a piecemeal approach, with poor interdepartmental working, as a major barrier to the effective implementation of policy on liaison and diversion services. The report called for the establishment of a National Programme Board to oversee the implementation of the recommendations in a coordinated fashion.

Outcomes of the Bradley Report

The Bradley Report was well received and the government accepted all the recommendations. The Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health issued a briefing, strongly endorsing Lord Bradley's recommendations and stating that they ‘would make a substantial difference to thousands of people's lives’ (Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health 2009a). In 2010 the Ministry of Justice published a Green Paper Breaking the Cycle, which addressed many aspects of punishing offenders, protecting the public and reducing offending, but reiterated the need to roll out liaison and diversion services nationally (Ministry of Justice 2010). Although a national approach is clearly needed to move towards consistent outcomes, it will also be important that there is sufficient flexibility at a local level to ensure that services are responsive to individual needs.

In November of 2009, the government published the delivery plan of the newly established Health and Criminal Justice Programme Board for improving the health of people within the criminal justice system. The document stated that the ‘development of liaison and diversion services is central to this plan’ (Department of Health 2009b: p. 7). The board brings together input from a range of government departments, such as the Department of Health, Home Office and Ministry of Justice. It also includes parts of the criminal justice system, such as the Crown Prosecution Service, National Offender Management System and HM Courts and Tribunals Service, and offender health researchers and members of the Bradley review working group. The plan outlined the mechanisms that would be used to deliver its key objectives. These were:

-

• improving the efficiency and effectiveness of systems

-

• working in partnership

-

• improving capacity and capability

-

• creating equity of access to services

-

• improving pathways and continuity of care.

The plan described how commissioning, developing the workforce and providers, improved information management and whole-systems research would be utilised to address the outstanding issues that Bradley and others had identified.

Since the publication of the Bradley Report, progress has been made towards the universal implementation of liaison and diversion services. The Offender Health Collaborative reviewed existing services between 2011 and 2013, identifying a variety of formats for service delivery that had developed in response to local requirements. From this work the national service specifications and operating model were created (for the current versions see NHS England 2016b). In January 2014, the Department of Health announced funding of £25 million to support existing liaison and diversion services and to test the service specifications in police stations and criminal courts in 10 trial sites in England. In April of 2014, responsibility for the liaison and diversion programme moved from the Department of Health to NHS England.

In June 2014, the Centre for Mental Health, in partnership with the Bradley Commission, produced a follow-up entitled The Bradley Report Five Years On (Reference Durcan, Saunders and GadsbyDurcan 2014). This identified areas where progress had been made, such as the establishment of a single operating model for police liaison and diversion services. Also noted were areas where more work is still needed, such as in the full implementation of the 14-day target for prison transfers. Additionally, the report made further recommendations, such as the need to ensure the availability of appropriate adults in police stations, the need to develop an operating model for prison mental healthcare and the importance of delivering mental health awareness training at all levels of the system.

NHS England's initiatives

NHS England has developed a large number of resources for commissioners and providers to help them to design and deliver liaison and diversion services. This includes advice on screening processes, referral pathways and example court report templates (cNHS England 2016c). In the 2 years between April 2014 and March 2016 almost 63 000 adults and over 8500 children have engaged with liaison and diversion services, resulting in over 20 000 referrals for treatment and support. On 12 July 2016, health minister Alistair Burt announced £12 million to fund the commitment for a further roll-out of liaison and diversion services. There was recognition that currently only 53% of the population in England is covered by liaison and diversion services. The ambition is to achieve 75% coverage by April 2018. Subject to an evaluation, a full roll-out is planned for 2020 (dNHS England 2016d). Although it is desirable to provide comprehensive coverage of such services, it is also important that new models can be informed by robust evidence of effectiveness. Even with the evaluation of the pilot sites, the rapid expansion may risk a hasty and haphazard implementation.

Impact of the reform of the Mental Health Act 1983

The 2007 amendments to the Mental Health Act 1983 (which were implemented in November 2008) resulted in a number of changes to the Act (Reference Branton and BrookesBranton 2010). These included, in Part I of the Act, a much broader definition of mental disorder, the removal of the ‘treatability test’ (which has been replaced by the need to demonstrate that ‘appropriate treatment’ is available) and the removal of the exclusion of deviant sexual conduct.

The Code of Practice and DSPD programme

The amendments to the Act were accompanied by a new, much more comprehensive Code of Practice (for the most recent version, see Department of Health (2015)). Although the Code of Practice was founded on a number of guiding principles, the intention of which is to ensure that those subject to the Act are respected, involved in decisions and detained in the least restrictive environment, the resulting changes led to concerns that individuals who were previously unlikely to be detained could and would now be subject to compulsory treatment in hospital. This included the use of the Mental Health Act to detain those characterised as having ‘dangerous severe personality disorder’ (DSPD) (Reference Howells, Krishnan and DaffernHowells 2007). The DSPD programme faced significant opposition from psychiatrists and others concerned about this extension of the public protection agenda (Reference DugganDuggan 2011) and it is a good example of the controversial use of the Mental Health Act to divert an offender from custody to a secure hospital to keep them detained. Subsequent evaluations of the DSPD programme indicate that prison-based DSPD units provide a more appropriate treatment setting than those based in hospitals, which are also more expensive to run (Reference RamsayRamsay 2011). As a result, NHS England has begun a process of disinvestment in DSPD services in hospital settings and it is instead commissioning new services for personality disordered offenders, mainly in prisons (NHS England 2014).

Community treatment orders

As well as the changes to Part I of the 1983 Act outlined above, the 2007 amendments introduced community treatment orders (CTOs), providing the opportunity to treat suitable patients in the community rather than under detention in hospital. The power to recall a patient on a CTO is intended to provide a way of responding to evidence of relapse or high-risk behaviour relating to mental disorder before the situation becomes critical and leads to the patient or others being harmed. This could therefore be seen as a means of reducing the risk of that individual deteriorating to the point where their behaviour results in them being detained by the police and placed in custody.

A detailed discussion of whether or not CTOs are effective is beyond the scope of this article, but in England the OCTET study supports the results of studies in other countries, which have found that CTOs do not appear to confer benefits for patients with psychosis (Reference Burns, Rugkåsa and MolodynskiBurns 2013).Footnote †

Places of safety

Consideration was given to extending the powers of the Mental Health Act to allow for the compulsory treatment of mentally disordered people in prison, but ultimately this was rejected as unsafe and unethical. At an earlier stage in the criminal justice system, changes to the Act provided the police with a new power to transfer people between places of safety. In addition, the new Code of Practice clearly states that the default place of safety for those detained under sections 135 and/or 136 of the Act should be a hospital facility, not a police cell (Department of Health 2015).

Detention under the Mental Health Act

Over the past decade or so there has been significant increase in the number of episodes of detention under the Mental Health Act. In 2014–2015 there were 58399 such detentions, an increase of 5223 (9.8%) compared with 2013–2014 and an increase of 17542 (42.9%) compared with 2003–2004. The increase in the number of detentions on admission between 2010–2011 and 2014–2015 was largely due to a rise in the number of detentions under section 2 over this period. There was little change in the number of detentions on admission under section 3 or in the number of detentions under Part III of the Act (patients concerned with criminal proceedings) during the same period (Health & Social Care Information Centre 2015).

It is important to bear in mind that the changes in mental health legislation and trends in the use of the Mental Health Act outlined above have not taken place in a vacuum; these changes have occurred alongside cuts in community mental health services, a progressive reduction in the number of psychiatric beds and pressures on a mental health system which has been described as ‘running “too hot”’. Difficulties admitting patients to hospital on a voluntary basis have led to reports that in some areas ‘being detained is the ticket to getting a bed’ (quotations from House of Commons Health Committee 2013: paras 26 and 27).

Development and evaluation of diversion initiatives

Working with the police and diversion at the point of arrest

Initiatives which involve joint working between the police and mental health practitioners can produce good results. They include local schemes where the police patrol with mental health practitioners at peak times; these services have reported a reduction in the use of section 136 of the Mental Health Act and an increase in the likelihood that those who are detained under section 136 are more likely to be in need of hospital treatment (Reference Durcan, Saunders and GadsbyDurcan 2014).

The Serenity Integrated Mentoring (SIM) project on the Isle of Wight is another example of a partnership between mental health practitioners and the police which has been used to create a specialist support team for ‘high-intensity’ mental health crises. This has recorded a 92% saving in ambulance deployment, in-patient bed-days, accident and emergency (A & E) department attendance and police incidents over 24 months (Reference JenningsJennings 2016).

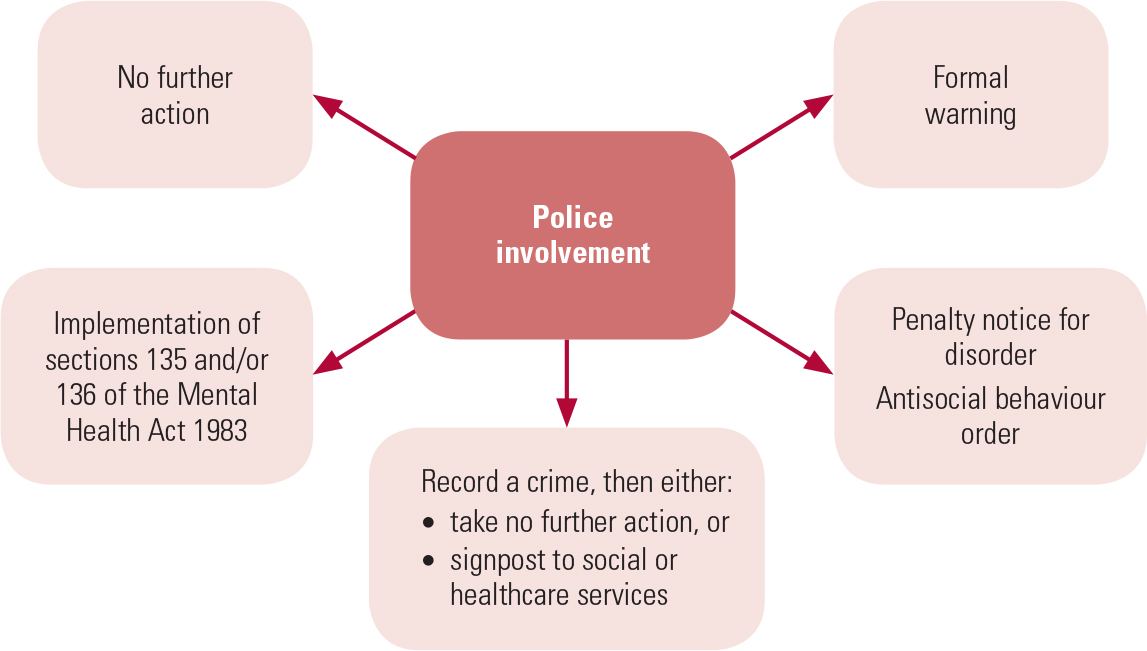

Even when working alone, the police can still play an important role in diverting mentally disordered people before an arrest takes place. The options available to them are outlined in Fig. 1. Uptake of these options is variable and can depend on the ability of the police officer to recognise the presence of mental disorder. In 2015 in England and Wales, there were 3817828 recorded and notifiable crimes. The number of penalty notices for disorder that were issued was 25938, and 135519 cautions were given (Ministry of Justice 2016a). The success of penalty notices for disorder is dependent on the ability of the offender to comply with the conditions. A Home Office review of antisocial behaviour orders found that 60% of individuals issued with this order had mental health problems (Reference CampbellCampbell 2002).

FIG 1 Alternatives available to the police to avoid arresting mentally disordered people.

Sections 135 and 136 of the Mental Health Act provide the powers for the police to take an individual with a suspected or confirmed mental disorder from a private or a public place to a ‘place of safety’, rather than making an arrest. As stated earlier, this place of safety should be a hospital facility, not a police cell. Between 2010–2011 and 2014–2015 the number of detentions by the police under section 136 rose from 14111 to 19403, an increase of 37.5%; but between 2013–2014 and 2014–2015 the number of occasions when people detained under section 136 were placed in police cells as a place of safety fell by nearly 38%, from 6028 to 3996 (Health & Social Care Information Centre 2015).

For some, contact with the police will result detention in custody (arrest). Estimates of the proportion of suspects passing through police stations who are mentally disordered vary between 2% and 20% (Reference Burney and PearsonBurney 1995; Reference Winstone, Pakes, Winstone and PakesWinstone 2005). Even if an individual is arrested, opportunities for diversion still abound, and a suspicion or report of mental illness by the custody officer, solicitor or forensic medical examiner can result in a request for an assessment under the Mental Health Act at the police station and the decision to divert the individual to health and social care services.

Court diversion

The magistrates’ court remains a prime location for diversion interventions. In 2015 the courts passed 1238917 sentences, of which 12992 were dealt with by way of restriction orders, hospital orders, guardianship orders and related disposals. There were an estimated 4571 mentally disordered offenders in hospital in 2014 (Ministry of Justice 2016a).

Evidence for the effectiveness of liaison and diversion services remains limited (Offender Health Research Network 2011), but stakeholders agree that they are likely to lead to an improvement in the overall health of mentally disordered offenders, reduce offending behaviour and improve social integration (Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health 2009b; Reference Durcan, Saunders and GadsbyDurcan 2014; NHS England 2014).

The current focus is on the development of a nationwide standardised approach to liaison and diversion for all age groups, following the successful pilot and implementation of the youth justice liaison and diversion (YJLD) programme (Reference Haines, Goldson and HaycoxHaines 2012). When an offender is identified as having a mental disorder, a liaison and diversion practitioner should screen the individual as soon as possible to identify the difficulty, associated risk and urgency attached to it. A more detailed assessment to inform the referral decision should then follow. Referrals are made to mainstream health and social care services and/or other intervention and support services. Liaison and diversion services should also be able to offer support to individuals attending their first appointment and to record the outcome (bNHS England 2016b).

Transfer of prisoners to and from hospital

Mental disorder in prisons

Although considerable effort has been put into developing diversion initiatives operating at earlier stages of the criminal justice system, plenty of mentally disordered people still find themselves in prison. There have been no further large-scale epidemiological studies of psychiatric morbidity among prisoners in England and Wales since the Office for National Statistics published its report in 1998 (Reference Singleton, Meltzer and GatwardSingleton 1998). However, there is no evidence to suggest that the prevalence of mental disorder in prisons has reduced (HM Inspectorate of Prisons 2007, 2012). Currently, many prisoners and prison staff report feeling more unsafe than they have done in the past, serious physical and sexual assaults in prison have more than doubled over the past 4–5 years, rates of self-harm are at their highest level ever and, of the 290 people who died in prison in the 12 months to March 2016, over a third died by suicide (Prison Reform Trust 2016).

The prison estate has been overcrowded every year since 1994. Since 2001, when this journal published its first article on diversion from custody (Reference BirminghamBirmingham 2001), the prison population in England and Wales has increased by nearly 30%, from 66 300 (Home Office 2003) to 85 152 (Ministry of Justice 2016b). This has largely been due to an increase in the number of prisoners sentenced to immediate custody, but longer sentences, including an increasing ‘lifer’ population and the introduction of indeterminate sentences for public protection in 2005, as well as changes introduced by the Criminal Justice Act 2003 making it easier to recall prisoners, have contributed (Ministry of Justice 2013).

The same period has also seen a considerable change in the way in which healthcare services are provided to those in prison.

Healthcare commissioning and delivery

Primary care trusts became fully responsible for commissioning healthcare in prisons in 2006, and in 2013 a national partnership agreement between NHS England, the National Offender Management Service and Public Health England was agreed. This agreement sets out the shared strategic intent and joint commitment to commission, enable and deliver healthcare services in adult prisons in England (for the latest version see National Offender Management Service et al (2015)).

More attention has been paid to identifying prisoners with mental health problems through better health screening at reception into prison (Offender Health Research Network 2008) and mental health awareness training for prison staff (Reference Musselwhite, Freshwater and JackMusselwhite 2004). In 2003 the first mental health in-reach services were introduced in prisons, with the intention of using the care programme approach to help address the needs of prisoners with severe and enduring mental illness. The remit of in-reach services was soon broadened (Reference Steel, Thornicroft and BirminghamSteel 2007), and in 2007 the Chief Inspector of Prisons commented that ‘when mental-health in-reach teams rode to the rescue of embattled prison staff they found a scale of need which they had neither foreseen nor planned for’ (HM Inspectorate of Prisons 2007: p. 5). This was borne out by a national evaluation of prison mental health in-reach which found that in-reach teams were struggling with low recruitment and ‘mission creep’ associated with growing caseloads of patients with complex needs, 60% of whom had no current serious mental illness. All of the in-reach team leaders who were surveyed as part of this evaluation thought that in-reach was an excellent idea but that it had been poorly resourced and poorly implemented (Offender Health Research Network 2009). Mental health services in prison have continued to develop, but in a piecemeal fashion, with no clear standards and a marked inequity of provision (Reference Kosky and HoyleKosky 2011).

Transfer to hospital for psychiatric treatment

Because no part of a prison is recognised as a hospital for the purposes of the Mental Health Act, prisoners who need to be detained in hospital for treatment of their mental disorder have to be transferred to suitable hospital facilities under Part III of the Act. Difficulties accessing services and long waits for hospital beds have been a problem for many years. For example, Reference Forrester, Henderson and WilsonForrester et al (2009), who studied 149 prisoners transferred to hospitals from two London prisons in 2003–2004, found the average wait for a bed was 102 days; only 20% of these individuals were referred, assessed and transferred within 1 month; 38% were transferred within 3 months, 42% waited longer than 3 months and 10% waited more than 6 months.

A national evaluation of the Department of Health guidelines on the transfer of mentally disordered prisoners to hospital (Reference Shaw, Senior and HayesShaw 2008) reported that transfers were taking anywhere between 0 and 175 days, with a mean wait of 42 days, but most of these prisoners had severe psychiatric illness, there were high rates of adjudications (disciplinary procedures), behavioural disturbance and self-harm among those waiting, and some were having only infrequent contact with healthcare staff in prison.

When the Bradley Report was published the following year (Department of Health 2009a) it was acknowledged that there had been some progress in reducing transfer delays, but there were still many mentally disordered prisoners having to wait for long periods in prison before they were transferred to hospital. Lord Bradley recommended that the Department of Health should develop a new minimum target for the NHS of 14 days to transfer a prisoner with acute, severe mental illness to an appropriate healthcare setting and that this should become a contractual requirement. This was piloted in several regions and when the Department of Health revised procedures for the transfer (and remission) of prisoners to hospital, 14 days was included as the suggested time frame, but only as a good practice guideline and not as a contractual requirement (Reference ManMan 2011).

Remission to prison from hospital: section 117 aftercare

One area in which the Department of Health guidelines (Reference ManMan 2011) have had a significant impact has been in the relation to section 117 aftercare for those being remitted to prison. It used to be the case that if the hospital wanted to remit a prisoner to prison, the responsible medical officer (RMO) simply had to inform the Ministry of Justice that the individual either no longer required treatment in hospital for mental disorder or that there was no effective treatment. In response, the Ministry would issue a warrant for their return under section 50 of the Mental Health Act. Now the Ministry of Justice needs to be satisfied that a section 117 meeting has been convened, to which the receiving prison has been invited, and that a suitable care plan has been agreed for the prisoner's return. Rather than returning the prisoner to the prison they originally transferred from, the Department of Health guidelines recommend that they should ordinarily be returned to the nearest local prison. In theory this should facilitate ongoing contact with the treating hospital, but in practice it can mean that the prisoner is sent to a busy local establishment where the mental health service has little or no prior knowledge of them, the environment and interventions provided do not meet their needs and they are at risk of being transferred to another prison at short notice.

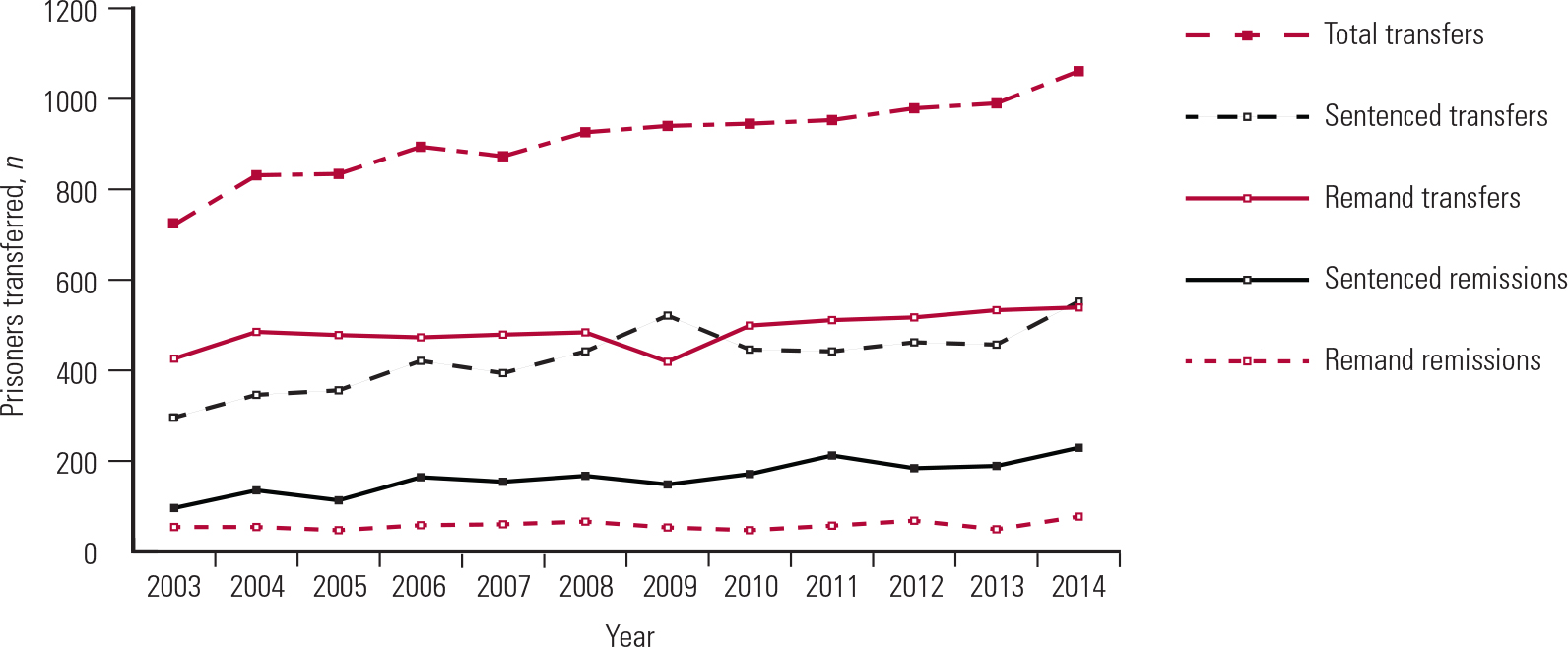

The number of prisoners transferred to hospital under sections 47 and 48 of the Mental Health Act increased steadily between 2003 and 2014, from 722 to 1061 (Fig. 2) (Ministry of Justice, personal communication, 2016), but this trend more or less matched the increase in the prison population over the same period. However, the number of sentenced prisoners remitted to prison more than doubled, from 96 to 229. A national study of discharges to prison from medium secure units in England and Wales in 2010–2011 found that nearly half of those discharged to prison were diagnosed with a serious mental illness and over a third with schizophrenia; these individuals were found to pose a higher risk, be more likely to have a personality disorder, have more severe symptoms and be significantly less likely to show motivation for treatment and positive attitudes towards authority than those discharged to the community (Reference Doyle, Coid and ArcherDoyle 2014).

FIG 2 Transfers of mentally disordered prisoners to hospital for treatment under the Mental Health Act 1983 and remissions from hospital to prison after treatment (Ministry of Justice, personal communication, 2016).

Conclusions

Over the past 15 years or so, liaison and diversion services have been shaped by considerable changes in policy, legislation and resources. This has resulted in some very positive developments, such as the growth of initiatives to divert individuals at the point of arrest and the significant reduction in the use of police cells as a place of safety for those detained under section 136 of the Mental Health Act. The development of mental health services in prisons and the use of the care programme approach in prison settings should also be welcomed.

On the other hand, the ongoing closure of hospital beds, the relentless rise in the prison population and the increasingly unsafe environment inside prisons have been particular causes for concern. On a more disturbing note, changes to the Mental Health Act 1983 and the development of DSPD services have resulted in people with personality disorder being diverted to hospital, where they can be detained indefinitely on the basis of ‘dangerousness’, and this situation has not been met with universal approval.

Much talk, little action

In the main, though, the past decade and a half has been characterised by a lot of talk and a great deal of political rhetoric, which has not actually resulted in much change for the better. This is illustrated by the fact that national liaison and diversion service specifications have only recently been agreed, despite the first court diversion scheme being set up nearly 30 years ago. At present, liaison and diversion services only cover just over half of the population in England, and the proposal to increase coverage to 75% by 2018 seems rather ambitious. At a more basic level, 8 years have passed since Lord Bradley recommended that mentally ill people in prison who require treatment in hospital should be transferred within 14 days, but we have come nowhere near achieving this target and many mentally ill prisoners wait months for a hospital bed. Given this situation, should more attention and further resources be directed towards expanding mental health services in prison and to avoiding the need for ‘diversion’ by extending the Mental Health Act to cover prisons? But should we really be looking to keep and treat seriously mentally unwell people in custodial settings that have become increasingly unstable and unsafe? What would this say about us as a society?

Do we know whether diversion is successful?

Thanks to Lord Bradley, diversion from custody has come to be seen as a journey rather than an event. But what actually happens to those who start this journey after they are diverted from the criminal justice system? We know that increasing numbers of mentally disordered individuals who are transferred from prison to secure hospitals are sent back to prison and that many of these individuals remain symptomatic and continue to pose significant risks. How does that benefit the individual or help to protect the public?

What about those who are diverted at earlier stages in the criminal justice system? The honest answer is that we just don't know, because despite all the changes in policy and funding promised to develop diversion initiatives over the past 15 years, there has been surprisingly little research to evaluate outcomes.

So, in conclusion, we need less talk and more action. We don't need people mulling over what the Reed and Bradley Reports have already told us. We need a national network of diversion initiatives at all stages of the criminal justice system, services (including hospital beds) to divert mentally disordered people in a timely fashion, and interventions which reduce the likelihood of these individuals having further contact with the criminal justice system. This requires commitment and funding and it requires evaluation through a robust programme of research.

MCQs

Select the single best option for each question stem

-

1 With regard to the use of the Mental Health Act 1983 in prisons in England and Wales:

-

a the 2007 amendments to the Act introduced the principle of equivalence, which means that the full scope of the Mental Health Act can now be applied in prison settings

-

b the 2007 amendments to the Act introduced community treatment orders into prisons

-

c no part of a prison is recognised as a hospital under the Act, but prisoners who require treatment in hospital for mental disorder can be transferred to hospital under Part III of the Act

-

d the Act does not apply to prisoners

-

e only prisons with an in-patient healthcare centres are recognised as ‘hospitals’ within the meaning of the Act.

-

-

2 According to the current Mental Health Act Code of Practice, a place of safety to which the police can take someone detained under section 136 of the Act should ideally be:

-

a in a prison

-

b in a local authority approved facility

-

c in a hospital setting

-

d a police cell

-

e c or d above.

-

-

3 The Bradley Report did not recommend:

-

a better education of police officers about mental illness

-

b the increased use of hybrid orders under section 45a of the Mental Health Act

-

c that NHS commissioners should seek to improve the provision of mental health primary care services in prison

-

d that all police stations have access to liaison and diversion support

-

e increased research into the treatment requirements of people with mental illness or or learning disabilities in the criminal justice system.

-

-

4 It is not a function of liaison and diversion services to provide:

-

a treatment

-

b identification

-

c assessment

-

d referral

-

e screening.

-

-

5 In recent times the number of people detained by the police under section 136 of the Mental Health Act (each year):

-

a has declined, but the use of police cells as a place of safety has increased

-

b has declined and the use of police cells as a place of safety has also declined

-

c has risen, but the use of police cells as a place of safety has declined

-

e has risen and the use of police cells as a place of safety has also increased

-

e has remained the same, but the use of police cells as a place of safety has increased.

-

| 1 | c | 2 | c | 3 | b | 4 | a | 5 | c |

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.