INTRODUCTION

Article 3(b) of the 2003 Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage (UNESCO Convention) prescribes that “[n]othing in this Convention may be interpreted as ... affecting the rights and obligations of States Parties deriving from any international instrument relating to intellectual property rights or to the use of biological and ecological resources to which they are parties.” The Convention declares that it intends to respect international agreements relating to intellectual property rights (IPRs).Footnote 1 In this respect, IPRs associated with intangible cultural heritage can contribute to promoting the purposes of the Convention. A good illustration of this is Article 49 of the Act on Preservation and Promotion of Intangible Cultural Property (Act on Intangible Cultural Property) in Korea.Footnote 2 It provides passive and active ways to protect intangible cultural properties in connection with IPRs.

The UNESCO Convention does not address IPRs except in relation to its emblem,Footnote 3 and, therefore, it also does not address domestic norms in relation to them. Those domestic norms on IPRs may contribute to the safeguarding purposes of the UNESCO Convention more effectively when the traditional knowledge, or its derivatives, of the holders of intangible cultural heritage are protected under an IPR regime, and their self-esteem and financial situation are improved. Richard Alba, in Ethnic Identity: The Transformation of White America (1990), writes that “[e]thnic culture embraces the patterned, commonplace actions that distinguish members of one ethnic group from another, including food, language, and holiday ceremony.”Footnote 4 Hence, traditional food, including recipes and foodways, can be the subject matter of protection on the basis of the UNESCO Convention, the Cultural Heritage Protection Act,Footnote 5 and several laws related to intangible properties such as the Patent Act,Footnote 6 Trademark Act,Footnote 7 the Act on Unfair Competition Prevention and Trade Secret Protection,Footnote 8 and the Act on Quality Control of Agricultural and Fishery Products (Act on Quality Control).Footnote 9

This article aims to contribute to the promotion of knowledge necessary for the effective protection of food and foodways as intangible properties on the basis of cultural heritage laws and intellectual property (IP) laws in Korea. This analysis will be carried out while considering the Korean elements related to traditional food and foodways that are already inscribed on the UNESCO lists—namely, kimjang, the making and sharing of kimchi. Kimchi is ‘a traditional fermented Korean side dish made of vegetables (mainly cabbage or radish) with a variety of seasonings. Kimchi’s history in Korea dates back to the seventh century when pickling was first used. In 1983, a multinational company applied for patents for a recipe to make food similar to kimchi in 15 countries including South Korea. This incident definitely drew attention from the Korean government. IP law systems sometimes conflict with the protection afforded based on the Korean Cultural Heritage Office and the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). This article explores how to strike a balance between IP law and cultural law protection regimes in passive and active ways.

This article examines the possibility that traditional food and foodways can be protected on the basis of IP laws because IP covers traditional knowledge, geographical indications, and trade secrets. The Framework Act on Intellectual Property in Korea defines the term “new intellectual property” as “intellectual property that appears in new fields in line with economic, social or cultural changes or the development of science and technology.”Footnote 10 Therefore, the term “intellectual property right” means “any right relating to intellectual property recognized or protected according to Acts and subordinate statutes, treaties, etc.”Footnote 11 In other words, the term “intellectual property” refers to knowledge, information, technology, the expression of thoughts or feelings, the indication of business or goods, the varieties of organism or genetic resources and other intangibles created or discovered by the creative activities, experience, and so on of human beings, and the value of the property that may be realized.Footnote 12 In particular, the paper points out that the development of geographical indications under the Trademark ActFootnote 13 and the Act on Quality ControlFootnote 14 can contribute to the preservation and expansion of traditional knowledge because traditional knowledge has some bearing on human or natural resources related to specific geographical locations. Finally, the article explains how to protect effectively traditional food and foodways as intangible properties in Korea, focusing on the IP protection of traditional knowledge and the preservation and expansion of traditional knowledge as cultural heritage.

DEFINITIONS OF FOOD, TRADITIONAL FOOD, AND TRADITIONAL FOODWAYS

Article 2, subparagraph 1, of the Food Sanitation Act prescribes that the term “food” means all types of things that humans can eat and drink, except for food and beverage taken as medicine.Footnote 15 This Act purports to contribute to the improvement of public health by preventing sanitary risk caused by food, promoting the qualitative improvement of food nutrition, and giving accurate information on food.Footnote 16 Article 3, subparagraph 7(a) and (b) of the Framework Act on Agriculture and Fisheries, Rural Community, and Food Industry (Framework Act on Agriculture and Fisheries) defines the term “food” as any of the following items: (1) agricultural and fishery products that humans can eat or drink directly or (2) all kinds of edible things, the ingredients of which are agricultural and fishery products.Footnote 17 The purpose of the Framework Act on Agriculture and Fisheries is

to provide for basic matters concerning directions to be sought by agriculture, rural communities, and the food industry and directions of national policy in order to pursue the sustainable development of agriculture and rural communities, which are the economic, social and cultural foundations of the citizens, to ensure the stable supply of safe agricultural products and quality food for the citizens, and to enhance the level of income and quality of life of farmers.Footnote 18

According to Article 2, subparagraph 4, of the Food Industry Promotion Act, the term “traditional food” means food with the unique tastes, flavors, and colors of traditional Korean cuisine, which is produced, processed, and cooked according to the methods passed down from old times on the basis of Korean agricultural and fishery products used as their main raw materials or ingredients.Footnote 19 The purpose of the Food Industry Promotion Act is to contribute to improving citizens’ quality of life and developing the national economy by promoting the sound development of the food industry through the reinforcement of the link between the food industry and the agriculture and fishery industries and by providing a variety of quality food in a stable manner by enhancing the competitiveness of the food industry.Footnote 20

In sum, when the purpose of the Framework Act on Agriculture and Fisheries and the Food Industry Promotion Act is seriously taken into account, the definition of “traditional food” is not limited to agricultural or fishery products. Hence, the word, “traditional food” can be defined as the food that is produced, processed, and cooked in accordance with the recipes inherited from ancient times on the basis of Korean products used as their main raw materials or ingredients. Also, the term “traditional foodways” can refer to the recipes inherited from ancient times on the basis of Korean products used as their main raw materials or ingredients.

CONSERVATION OF INTANGIBLE CULTURAL HERITAGE AND NECESSITY FOR ITS PROTECTION UNDER IP AND NON-IP REGIMES

When it comes to intangible cultural heritage, “more than one community makes similar use of the same resources, sometimes even using the same processes.”Footnote 21 Hence, taking into account this lack of originality, novelty, or distinctiveness in character, some common law scholars argue that pre-existing IPR regimes are deficient and generally inappropriate in terms of addressing the claims of Indigenous peoples for greater legal protection of their intangible cultural heritage.Footnote 22 Instead, they propose that traditional concepts of contract, privacy, trade secret, and trademark can afford better protection to their cultural heritage.Footnote 23

From the perspective of civil law scholars, trade secrets and trademarks can be categorized as intellectual properties. Hence, trade secrets, certification marks,Footnote 24 collective marks, geographical indication (GI) certification marks,Footnote 25 and GI collective marks can contribute to the promotion of intangible cultural heritage. In addition, global effort has been made by the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) to complete a couple of treaties that would protect the intangible cultural heritage of Indigenous peoples.Footnote 26 The global campaign has been initiated under the umbrella of “traditional knowledge” rights. They cover cultural expression and Indigenous technologies, know-how, and bio-resources.Footnote 27

Domestically, Article 49 of the Act on Intangible Cultural Property provides us with passive and active ways to protect intangible cultural properties in connection with IPRs.Footnote 28 Traditional knowledge rights can be justified under cultural integrity and economic justice rationales.Footnote 29 However, Korea has yet to enact a law that recognizes traditional knowledge rights, such that the holders of intangible cultural heritage can only rely on preexisting IP and cultural heritage regimes.

ACTIVE WAYS OF PROTECTING TRADITIONAL FOOD AND FOODWAYS

Active Ways of Protecting Traditional Food and Foodways under the IP Regime

Patents of Traditional Food and Foodways

The export of Korean agricultural food has amounted to $5.6 billion as of 2016.Footnote 30 As Korean cuisine (“hansik” in Korean) becomes popular globally, patent applications based on Korean food and recipes have been increasing.Footnote 31 For instance, about 50 Kimchi-related patent applications have been filed annually in the past 10 years. Of these, technology that increases the flavor and taste of kimchi constitutes 39 percent of the total number of the kimchi-related patent applications, and Korean food and recipes with a strengthening functionality, through the addition of specific substances or ingredients for the purpose of preventing or curing diseases, were ranked second at 30 percent.Footnote 32

Article 2(1) of the Korean Patent Act defines “inventions” as “highly advanced creations of technical ideas utilizing the laws of nature.”Footnote 33 For a patent registration, an invention must satisfy the basic criteria of industrial applicability, novelty, and non-obviousness.Footnote 34 Improvements made to traditional food and recipes can be protected under the patent system if they meet the requirements for patentability, especially novelty and non-obviousness. Since September 1990, the inventions of food and table luxuries have become the subject matter of patents.Footnote 35 One might think that the novelty and inventive requirements for patentability of traditional food and foodways could conflict with the transmission of original, traditional food and foodways for generations. Traditional food such as kimchi can be made in accordance with recipes or methods different from traditional foodways and be patented. The issue at hand is whether they can be classified as traditional food and traditional foodways. Article 49 of the Act on Intangible Cultural Property in Korea provides us with passive and active ways to protect intangible cultural properties in connection with IPRs.

Unfair Competition Law

Unfair Competition

Korean traditional food and foodways can be protected pursuant to the Unfair Competition Prevention and Trade Secret Protection Act (Unfair Competition Prevention Act) in Korea.Footnote 36 For instance, the holder of traditional food can enjoin the defendant from selling his or her goods and seek damages against the defendant because the defendant has copied the shape of the goods of the plaintiff(s).Footnote 37

Trade Secrets of Food and Foodways

Traditional food and recipes owned by a specific family can be protected as trade secrets. The term “trade secret” means information, including a production method, sale method, or useful, technical, or business information for business activity, that is not known publicly, is the subject of reasonable effort to maintain its secrecy, and has independent economic value.Footnote 38 Prior to the revision of the Unfair Competition Prevention Act in 2015, the Act defined a trade secret as “information, including a production method, sale method, or useful, and technical or business, information for business activity, that is not known publicly, is the subject of considerable effort to maintain its secrecy, and has independent economic value.” In other words, by virtue of the 2015 revision of the Unfair Competition Prevention Act,Footnote 39 the test to maintain the secrecy of a trade secret was lowered so as to protect small- and medium-sized businesses that do not have an internal system and financial resources sufficient to protect their trade secrets. Moreover, Article 3 of the Unfair Competition Prevention Act refers to the “infringement of trade secrets” as follows:

(a) An act of acquiring trade secrets by theft, deception, coercion or other improper means (hereinafter referred to as “act of improper acquisition”), or subsequently using or disclosing the trade secrets improperly acquired (including informing any specific person of the trade secret while under a duty to maintain its secrecy; hereinafter the same shall apply);

(b) An act of acquiring trade secrets or using or disclosing the trade secrets improperly acquired, with knowledge of the fact that an act of improper acquisition of the trade secrets has occurred or without such knowledge due to gross negligence;

(c) An act of using or disclosing trade secrets after acquiring them, with knowledge of the fact that an act of improper acquisition of the trade secrets has occurred or without such knowledge due to gross negligence;

(d) An act of using or disclosing trade secrets to obtain improper benefits or to damage the owner of the trade secrets while under a contractual or other duty to maintain secrecy of the trade secrets;

(e) An act of acquiring trade secrets, or using or disclosing them with the knowledge of the fact that they have been disclosed in the manner provided in item (d) or that such disclosure has been involved, or without such knowledge due to gross negligence;

(f) An act of using or disclosing trade secrets after acquiring them, with the knowledge of the fact that they have been disclosed in a manner provided in item (d) or that such disclosure has been involved, or without such knowledge due to gross negligence.

Hence, as mentioned above, the recipes of traditional food held by a specific family can be protected as a trade secret. However, traditional food and foodways are not usually protectable as trade secrets because they do not meet the requirement as to whether their holder(s) has(have) made reasonable effort to maintain their secrecy. Nonetheless, new menus and recipes transformed from the original, traditional food and recipes can be protectable as trade secrets. In this regard, the certificate of the original documents of the trade secret can be taken into account.

Article 9 bis (1) of the Unfair Competition Prevention Act prescribes that “in order to have an electronic document certified as to whether it is an original document containing trade secrets, a person who possesses trade secrets may file for registration of the unique identification value extracted from the relevant electronic document (hereinafter referred to as ‘electronic fingerprint’) with an agency that certifies the original documents of trade secrets.” In addition, Article 9 bis (2) of the Unfair Competition Prevention Act states that “where the electronic fingerprint registered under paragraph (1) and the electronic fingerprint extracted from the electronic document kept by a person who possesses trade secrets are the same, an agency that certifies the original documents of trade secrets ... may issue a certificate verifying that the relevant electronic document is the original registered with the electronic fingerprint (hereinafter referred to as ‘certificate of the original document’).”Footnote 40 In this regard, the person to whom a certificate of the original document has been issued is presumed to hold information about the content of the electronic document as at the time of the registration of the electronic fingerprint.Footnote 41 The legal mechanism for the certification of the original document of the trade secret is not to prove the date of the development of the trade secret or the person who developed the trade secret for the first time but, rather, to indicate the person who holds information on the content of the electronic document at the time the electronic fingerprint is registered. This mechanism is applicable to legal entities as well as individuals. Hence, a holder of a recipe may apply for registration of his or her electronic fingerprint to protect his or her recipe in an active way.

Geographical Indications of Traditional Food and Foodways

Geographical Indications and Traditional KnowledgeFootnote 42

Traditional food has drawn special attention from each country in international trade law.Footnote 43 Traditional food has frequently had some bearing on GIs. GI rights do not aim to encourage innovation and individual creativity by granting a monopoly for a certain period. Instead, they represent commonly used geographical names, set up permanent communal rights, and purport to protect “old knowledge.”Footnote 44 In this regard, when it comes to cultural heritage, GIs are considered a mechanism for regional producers to “nurture regional cultural heritage.”Footnote 45 A good example concerns kimchi. Kimjang, which means “making and sharing Kimchi in the Republic of Korea,” was inscribed as an intangible cultural heritage of humanity on the UNESCO list. One GI, Yeosu Dolsan leaf mustard kimchi,Footnote 46 is related to the UNESCO list (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. GI for Agricultural Products no. 68 registered by the Federation of Producers Yeosu Dolsan Leaf Mustard Kimchi on 12 July 2010 in Yeosu City (http://www.naqs.go.kr/contents/relicDetail.do (accessed 15 March 2019).

In this context, Article 10.40(1) of the Korea–European Union Free Trade Agreement (Korea–EU FTA) provides as follows:

ARTICLE 10.40: GENETIC RESOURCES, TRADITIONAL KNOWLEDGE AND FOLKLORE

1. Subject to their legislation, the Parties shall respect, preserve and maintain knowledge, innovations and practices of indigenous and local communities embodying traditional lifestyles relevant for the conservation and sustainable use of biological diversity and promote their wider application with the involvement and approval of the holders of such knowledge, innovations and practices and encourage the equitable sharing of the benefits arising from the utilisation of such knowledge, innovations and practices.

2. The Parties agree to regularly exchange views and information on relevant multilateral discussions:

(a) in WIPO, on the issues dealt with in the framework of the Intergovernmental Committee on Genetic Resources, Traditional Knowledge and Folklore;

(b) in the WTO, on the issues related to the relationship between the TRIPS Agreement and the Convention on Biological Diversity (hereinafter referred to as the “CBD”), and the protection of traditional knowledge and folklore; and

(c) in the CBD, on the issues related to an international regime on access to genetic resources and benefit sharing.

3. Following the conclusion of the relevant multilateral discussions referred to in paragraph 2, the Parties agree, at the request of either Party, to review this Article in the Trade Committee in the light of the results and conclusion of such multilateral discussions. The Trade Committee may adopt any decision necessary to give effect to the results of the review.Footnote 47

Furthermore, Article 37(1) of the Framework Act on Agriculture and Fisheries prescribes, under the title of “protection of intellectual property rights, etc.” that “the State shall set up and enforce the policies necessary to protect intellectual property rights related to the agricultural industry, agricultural community and food industry, inclusive of agricultural genetic resources, farming techniques, traditional farming, methods of producing traditional food, trademarks, geographical indications, new breeding and plant varieties, biotechnology.”Footnote 48

In addition, Article 2, subparagraph 6, of the Act on Conservation and Use of Biological Diversity (Act on Biological Diversity)Footnote 49 defines “traditional knowledge” as the “knowledge, technology and practices of individuals and local communities who have maintained a traditional lifestyle appropriate for conservation of biological diversity and sustainable use of biological resources.” Article 20 of the Act prescribes that the Korean government is obliged to carry out the following national policies to promote conservation and use of traditional knowledge: (1) finding, researching, and protecting the traditional knowledge of individuals and local communities; (2) gathering of traditional knowledge-related information and establishing a system for managing it; and (3) establishing a foundation for using traditional knowledge. In this context, traditional knowledge and culture related to food and foodways can be indirectly protected under the GI system.

Legal Sources and Current Development of GIs in Korea

GIs in Korea are primarily governed by: (1) the Trademark Act; (2) the Act on Quality Control;Footnote 50 and (3) the Unfair Competition Prevention Act.Footnote 51 Under the Korea–EU FTA,Footnote 52 Korea recognizes GIs for agricultural products, foodstuffs, wines, aromatized wines, and sprits.Footnote 53 According to subsection C, footnote 3, of the Korea–EU FTA, the protection of a GI under subsection C is without prejudice to other provisions in this FTA. The FTA’s primary focus on GIs is in relation to agricultural products and foodstuffs pursuant to Annex 10-A for agricultural products and foodstuffs and to Annex 10-B for wines, aromatized wines, and spirits. The GIs listed under the Korea–EU FTA will be protected within the national borders of the other parties. However, the issue as to whether the GIs that become generic, such as champagne for brandy, can be protected under the Korea–EU FTA, needs to be explored. The GIs with a generic nature cannot be protected under the Korean Trademark Act. However, they may be protected pursuant to the Korean Agricultural and Fishery Products Control Act and the Unfair Competition Prevention Act.

Having examined a summary of the specifications of the agricultural products and foodstuffs corresponding to the GIs of Korea listed in Annex 10-A of the FTA, which have been registered by Korea under the Act on Quality Control, the EU has undertaken to protect the GIs of Korea listed in Annex 10-A of the FTA according to the level of protection laid down in the Korea–EU FTA.Footnote 54 The Korea–EU FTA does not cover GIs for fishery products because both the EU regulations and the Korean regulations referred to in the Korea–EU FTA do not specify to do so. The Korea–EU FTA is the most important bilateral agreement that Korea has concluded in terms of the protection of GIs. In this regard, it should be noted that the total number of registered collective marks for GI protection, pursuant to the Korean Trademark Act as of 21 August 2015, amounted to 291, while the number of registered GIs on the basis of the Act on Quality Control as of the same date was 169.Footnote 55 Unfortunately, it does not include GIs for fishery products such as laver (for example, Jangheong Musan laver (gim in Korean).Footnote 56

GI Protection under the Korean Trademark Act

Overview

The purpose of the Korean Trademark Act is “to contribute to the development of industry and to protect the interests of consumers by maintaining the business reputation of those persons using trademarks through the protection of trademarks.”Footnote 57 According to Article 2(1)(4) of the Korean Trademark Act, the term “geographical indication” refers to “an indication used to identify goods produced, manufactured, or processed in a specific area in cases where a certain quality, reputation or other characteristic of those goods has essentially originated from such specific area.” It differs from the GI protection under the Act on Quality Control, which will be explained below. The word “homonymous geographical indication” means “a geographical indication for the same goods which share the same pronunciation with a geographical indication of other goods, but the relevant geographical location is different from that other indication.”Footnote 58 Pursuant to Article 2(1)(6) of the Korean Trademark Act, the term “GI collective mark”Footnote 59 means “a mark intended to be used directly by a corporation incorporated by persons who produce, manufacture, or process goods on which a geographical indication may be used, or is intended to be used by its members.” The term “geographical certification mark” means “a certification mark with a geographical indication used by a person who carries on the business of certifying the quality, origin, mode of production, or other characteristics, of goods in order to certify whether the goods of a person who carries on the business of producing, manufacturing or processing goods satisfies specified geographical characteristics.”Footnote 60 Any corporation (in the case of a collective mark with a geographical indication, limited to a corporation only comprised of persons who produce, manufacture, or process goods upon which such GI may be used) jointly founded by persons who produce, manufacture, process, or sell goods or provide services, may obtain registration of its collective mark.Footnote 61 Any person who may commercially certify and manage the quality, place of origin, methods of production, or other characteristics of goods may obtain a certification mark registration to be used only for the purpose of certifying that the goods of others satisfy the specified quality, place of origin, methods of production, or other characteristics. Where such a person intends to use the certification mark on goods for his or her own business, he or she shall not obtain the certification mark registration.Footnote 62

Article 33 of the Korean Trademark Act stipulates a distinctiveness requirement:

Article 33 (Requirements for Trademark Registration)

(1) A trademark registration may be granted, except for a trademark falling under any of the following subparagraphs:

1. A trademark consisting solely of a mark indicating, in a common way, the ordinary name of the goods;Footnote 63

2. A trademark used customarily on the goods;Footnote 64

3. A trademark consisting solely of a mark indicating in a common way the origin, quality, raw materials, efficacy, use, quantity, shape (including shapes of packages), price, production method, processing method, method of use or time of the goods;Footnote 65

4. A trademark consisting solely of a conspicuous geographical name, the abbreviation thereof or a map;

5. A trademark consisting solely of a mark indicating in a common way a common surname or name;

6. A trademark consisting solely of a simple and ordinary mark;

7. A trademark, other than those as referred to in subparagraphs 1 through 6, which does not enable consumers to recognize whose goods it indicates in connection with a person’s business.

(2) Even if a trademark falls under any of paragraph (1), subparagraphs 3 through 6, where such trademark is recognizable to consumers as a trademark indicating the source of goods of a specific person as a result of use made of the trademark prior to the filing an application for trademark registration, trademark registration may be granted, limited to the goods on which such trademark has been used.

(3) Even if a mark falls under paragraph (1), subparagraphs 3 (limited to place of production) or 4, where such mark is a geographical indication for specific goods, an applicant may obtain registration of a collective mark containing a geographical indication for goods using such geographical indication as designated goods (with reference to the goods designated pursuant to Article 38 (1) and the goods additionally designated pursuant to Article 86 (1); hereinafter the same shall apply).

Article 33(1)(3) and (4) of the Trademark Law includes geographical names as indistinctive trademarks. Hence, a conspicuous geographical term is not distinctive pursuant to Article 33(1)(4) of the Trademark Law. If it acquires distinctiveness by its use, pursuant to Article 33(2) of the Trademark Law, it can be registered. Nonetheless, if Article 34(1) is applied to it, it may not be registered. Also, the place of origin is not distinctive because it is a descriptive mark based on Article 33(1)(3). If it acquires a secondary meaning through its use, it can be registered. However, if Article 34(1) is applied to it, it may not be registered. In addition, even though conspicuous geographical terms or the places of origin are not distinctive, it can be registered as GI collective marks or GI certification marks. If Article 34 (1) is applied to them, they may not be registered.

In sum, Article 34(1) of the Trademark Law provides the requirements for unregistrable trademarks in spite of their distinctiveness.Footnote 66 The protection of GIs under the Trademark Act is not limited to agricultural and fishery products. Also, the duration of the protection of trademarks, including GIs, is 10 years from the date of registration.Footnote 67 However, whether protected geographical indications (PGIs) under the Act on Quality Control have a duration of protection is unclear because the Act remains silent on this subject.

Cases

In the Anhung Steamed Bread case,Footnote 68 the Korean Patent Court, the court of the second instance, ruled that Anhung steamed bread (안흥찐빵 in Korean) for streamed bread constituted a GI collective mark and was valid because it was handmade and was made of red bean produced in the Gangwon-Do province to preserve its quality and characteristics.

GI Protection under the Korean Unfair Competition Prevention Act

Overview

Under Article 2(1)(d) and (e) of the Korean Unfair Competition Act, the following acts constitute an unfair competition act: (1) an act of causing confusion about the place of origin by making false marks of the place of origin on goods and trade documents or in communications by means of advertisements of the goods or in a manner that makes the public aware of the marks or by selling, distributing, importing, or exporting goods bearing such marks and (2) an act of making a mark that would mislead the public into believing that goods are produced, manufactured, or processed at locations other than the actual places of production, manufacture, or processing, on goods, or on trade documents or in communications by means of advertisements of the goods or in a manner that makes the public aware of the mark or by selling, distributing, importing, or exporting goods bearing such mark. In addition, with respect to a geographic mark protected under a FTA that is concluded bilaterally or multilaterally and takes effect between the Republic of Korea and a foreign country, or foreign countries, certain acts are prohibited in line with those international instruments.Footnote 69

Protection of GIs under the Korean Act on Quality Control

Article 2(1)(8) of the Act on Quality Control prescribes that the term “geographical indication” refers to “an indication displaying that agricultural or fishery products or processed agricultural or fishery products, … the reputation, quality and other attributes of which have essentially originated from the geographical characteristics of a specific region, are produced and processed in the specific region.” The requirements for registration of a GI under the Act on Quality Control appear to be much stricter than that for registration of a trademark under the Trademark Act. In addtion, Article 2(1)(9) of the Act on Quality Control prescribes that the term “homonymic geographical indication” is “a geographical indication, the pronunciation of which is identical to that of another person’s geographical indication for the same item but refers to a different region.” The Act on Quality Control affords protection on GI. In this Act, a right to a GI stands for an “intellectual property right to exclusively use geographical indications registered pursuant to the Act.” In this regard, it should be compared to a right granted for a GI under the Trademark Act because the right to a GI pursuant to the Act on Quality Control is clearly prescribed as a kind of IPR.Footnote 70

Whether GIs under the Act on Quality Control have a duration of protection is unclear because the Act remains silent on this subject. Also, despite the fact that the conditions for registration of PGIs under the Act on Quality Control are not explicitly prescribed, they can be inferred from the combined interpretation of the Act and the executive decree for the Act on Quality Control. In addition, the GI examination board under the Act is well qualified for the examination of GI applications.

Some Observations

Traditional knowledge on Korean food and foodways, in particular, can be a good subject matter for GI protection. In other words, traditional knowledge and culture related to food and foodways can be indirectly protected under the GI system. From the perspective of comparativists, the protection of GIs for fishery products has not been fully developed. As such, the Korean negotiators for FTAs with foreign countries need to pay attention to GIs for fishery products. In addition, GIs have some bearing on the diversity of languages used in each country. For example, a potential applicant for the registration of a trademark in China is strongly advised to apply for the registration of a trademark in Chinese as well as in English and in his or her own language because a trademark in Chinese sounds totally different from one in English or in his or her own language. That is, Chinese consists of ideograms, whereas English and Korean are comprised of phonograms. Furthermore, it should be noted that Japanese consists of katakana and hirakana, which are phonograms, and kanji, which is made up of ideogrammatic Chinese characters. For example, BMW is registered as 寶馬 (Bao ma) through the use of Chinese characters.

Also, the territoriality principle applies to trademark law. Even though a GI for a designated goods is conspicuous in Korea and cannot be registered in Korea, it can be registered in relation to the designated goods or other goods in Japan, China, and any other country. To solve the territoriality principle applied to GIs, bilateral international agreements, such as the Korea–EU FTA, can be used. However, those countries that have included GI protection into their legal system, such as Korea and China, have experienced some trouble, resulting in competing, and sometimes conflicting, legal schemes. In this regard, the IP community needs to delve into substantive aspects of GI protection, including the scope and level of protection for GIs, the conditions for the registration of GIs, and the duration of GI protection. In addition, effective enforcement and consistent procedures that deal with disputes pertaining to GI protection need to be taken into account.

Active Ways of Protecting Food and Foodways under the Non-IP Regime

Cultural Heritage Protection Act

The Cultural Heritage Protection ActFootnote 71 can contribute to conserving and using traditional food and foodways on basis of the Korean administrative laws. According to Article 2(1)(2)(c) and (e) of the Cultural Property Protection Act,Footnote 72 intangible cultural property covers traditional knowledge, including oriental medicine, farming and fishing, and traditional customs inclusive of clothing, food, and housing. According to Article 2(1)(2) of the Cultural Heritage Protection Act, the term “intangible cultural heritage” is defined as “intangible cultural works of outstanding historic, artistic, or academic value, such as drama, music, dance, game, ritual, craft skill, etc.” The administrator of the Cultural Heritage Administration may designate more valuable intangible cultural heritage as important intangible cultural heritage, following deliberation by the Cultural Heritage Committee.

Where the administrator of the Cultural Heritage Administration designates any intangible cultural heritage as important intangible cultural heritage, he or she shall also recognize a holder (including a holding organization) of the important intangible culture heritage. On 9 February 2005, Korea became the eleventh signatory to the UNESCO Convention, which was adopted on 17 December 2003. Based on this Convention, 18 items of Korean intangible cultural heritage of humanity were inscribed on the UNESCO list as of 25 May 2016. Kimjang— the making and sharing of kimchi in the Republic of Korea—is one of them, and it was inscribed on the UNESCO list in 2013.

Intangible cultural property needs to be differentiated from intangible cultural heritage. Cultural property protection law refers to “intangible cultural property” on a national level and “intangible cultural heritage” on an international level. As a result, the law has failed to identify the implication of the bifurcated wording.

Act on Biological Diversity

Like the Cultural Heritage Protection Act, the Act on Biological Diversity can also contribute to conserving and using traditional food and foodways on the basis of Korean administrative laws.Footnote 73 Article 2, subparagraph 6, of the Act on Biological Diversity defines “traditional knowledge” as “knowledge, technology and practices of individuals and local communities who have maintained a traditional lifestyle appropriate for conservation of biological diversity and sustainable use of biological resources.” Article 20 of the Act prescribes that the Korean government is obliged to carry out the following national policies to promote conservation and use of traditional knowledge: (1) finding, researching, and protecting the traditional knowledge of individuals and local communities; (2) gathering traditional knowledge-related information and establishing a system for managing it; and (3) establishing a foundation for using traditional knowledge.

Voluntary Escrow of Recipes or Information on Food under the Act on the Promotion of Collaborative Cooperation between Large and Small-Medium Enterprises

The escrow systemFootnote 74 under the Act on the Promotion of Collaborative Cooperation between Large and Small-Medium Enterprises (Act on Cooperation Promotion),Footnote 75 was introduced into the Act on Cooperation Promotion in 2010,Footnote 76 and the total number of escrows exceeded 10,000 as of March 2014.Footnote 77 The Large and Small Business Cooperation Foundation, which was established under the supervision of the Small and Medium Enterprise Administration, has been in charge of the escrow of technical data. According to Article 2, subparagraph 9, of the Act on Cooperation Promotion, the term “technical data” means “the method of manufacturing or producing goods, etc., and other data useful for business activities and that have independent economic value, which is prescribed by the Enforcement Decree on the Cooperation Promotion Act (Presidential Decree).Footnote 78 Article 1 bis of the Enforcement Decree prescribes that the technical data consists of information on IPRs such as patents, utility model rights, design rights, copyrightsFootnote 79 or on useful technical or business information for business activity such as methods for manufacture, production, and sale.Footnote 80 Even though useful technical or business information for business activity is not the subject of considerable effort to maintain its secrecy, it can be voluntarily escrowed under the Act on Cooperation Promotion. Hence, the scope of information pursuant to Article 1 bis (2) of the Act on Cooperation Promotion is broader than that of trade secrets, which requires that their holder(s) make a reasonable effort to maintain its secrecy.

A bailor enterprise may register its technical data: (1) the title, type, and production date of technical data; (2) the outline of technical data; (3) the name and address of the bailor enterprise; and (4) other matters prescribed by the Presidential Decree.Footnote 81

If any dispute occurs between the parties concerned or parties interested in the technology of a bailor enterprise registered in its real name, such technology shall be presumed to have been developed in accordance with the details of the deposited goods.Footnote 82 In this context, recipes and information on food that are believed to have independent economic value can be escrowed and are legally presumed to have been developed by its bailor at the date when they were produced, in accordance with the details of the deposited recipes and the information on food as is. The Act on Cooperation Promotion is applicable only to businesses and excludes individuals.

Some Observations

In terms of the active ways of protecting traditional food and foodways under non-IP regimes, the Cultural Heritage Protection Act and the Act on Biological Diversity can contribute to conserving and using traditional food and foodways on the basis of Korean administrative laws. For traditional food and foodways that do not fall within the definition of traditional knowledge under these laws, they can be protected by classic IP laws and/or as intangible cultural property.

PASSIVE WAYS OF PROTECTING FOOD AND FOODWAYS UNDER THE IP REGIME

Patents on Food and Foodways

Patentability of Food and Foodways

The national Korean Internet portals related to food and foodways play an important role in preventing individuals, legal entities, and foreign governments from patenting Korean traditional food and recipes. This is because the lack of novelty will prohibit them from patenting the original form of the Korean traditional food and recipes.

Nestle’s Kimchi-related Case

In 1983, the Societe d’Assistance Technique pour Produits Nestle S.A. (Nestle) applied for a patent on a process for producing vegetable juice through fermentation, similar to the process used to make kimchi, in 15 countries, including Korea.Footnote 83 Its patent application was denied in Korea because the application was similar to kimchi. However, except for its patent application in Korea, its patent applications for the same process were approved in the other 14 countries. For example, in the United States, the “preparation of a flavored solid vegetable and vegetable juice utilizing hydrolysed protein”Footnote 84 was filed on 4 October 1983, and patented on 25 December 1984, before the US Patent and Trademark Office.Footnote 85

The reason why Nestle obtained patents for the process in the other 14 nations is that, in 1983, no official references were available to prevent Nestle from patenting the process of making vegetable juice through fermentation.Footnote 86 Hence, it was imperative for the Korean government to establish the Internet homepage(s) that would introduce information on traditional Korean food and foodways to the public. Thus, the Korea Traditional Food portal is very pivotal for the Korea Food Research Institute (KFRI) to meet international standards on its promotion of Korean food and foodways.Footnote 87 In 2009, the website was introduced by the KFRI through a year-long collaboration with the Korea Agency of Digital Opportunity and Promotion and the Korea Institute of Science and Technology.Footnote 88 Another significant website is the Korean Traditional Knowledge Portal.Footnote 89 This website has been operated by the Korean Intellectual Property Office since December 2007. It includes information on traditional, as well as local, food. The website for traditional food in the Korean Traditional Knowledge Portal covers information on traditional food, recipes, and foodstuff (see Figures 2, 3 and 4).

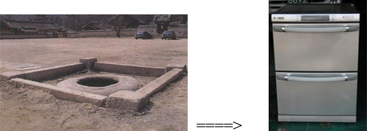

Figure 2. Application of the traditional preservation method of Kimchi in winter, including a traditional stone jar for the preservation of kimchi / a refrigerator for the preservation of kimchi throughout the year (http://shopping.daum.net/search/%EA%B9%80%EC%B9%98%EB%83%89%EC%9E%A5%EA%B3%A0%20%EC%82%AC%EC%A7%84/&docid:M500562738&srchhow:Cexpo [accessed 1 May 2016]).

Figure 3. Patent on Korean Traditional Knowledge in the United States (https://patentimages.storage.googleapis.com/53/36/02/0d44122238e63c/US4464407.pdf (15 March 2019).

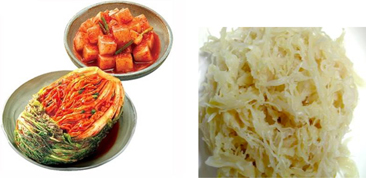

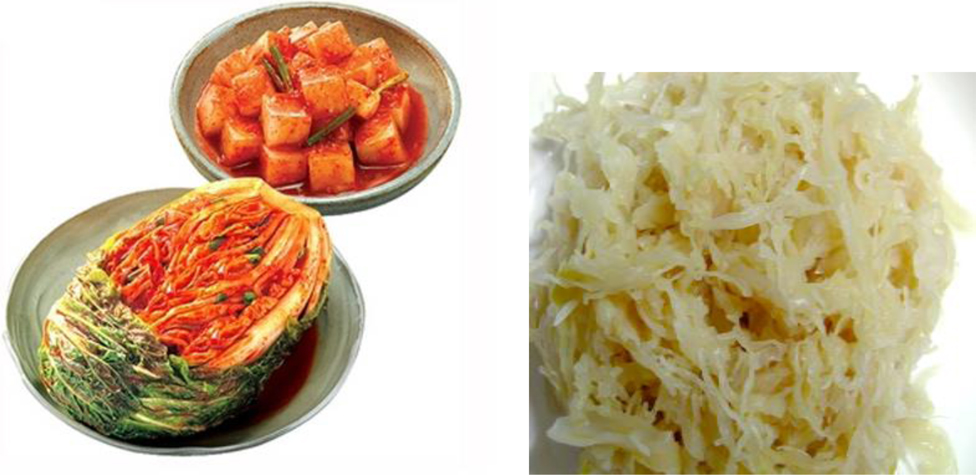

Figure 4. Kimchi sauerkraut (Korean Intellectual Property Office, Introduction of Korean traditional Knowledge Portal (KTKP), March 2011, https://www.wipo.int/edocs/mdocs/tk/en/wipo_tkdl_del_11/wipo_tkdl_del_11_ref_t9_4.pdf (accessed 15 March 2019).

International Trademark Classification of Food (Nice Classification)

Since 1 January 2007, the English designation of kimchi has been listed on the Nice Agreement Concerning the International Classification of Goods and Services for the Purposes of the Registration of Marks (Nice Classification). Hence, the name “kimchi” has gained international prestige as a side dish, and it has assured global businesses and the international legal community that the traditional Korean food made of pickled cabbages originates from Korea and not from other countries.Footnote 90 As such, the Japanese now refer to it as “kimuchi.” The Nice Classification has thus contributed to proving the origin of traditional knowledge in some sense (Table 1).

Table 1. Nice Classification (International Trademark Classification)

The case of kimchi demonstrates that the original and long-standing form of traditional staple foods can be listed on the Nice Classification and prevent foreign governments, legal entities, and individuals from obtaining a trademark in foreign jurisdictions. In this context, despite the fact that the word “kimchi” is a generic term, it signifies from a cultural perspective that the internationally well-known food originally came from Korea.

PROPERTY RULES VERSUS HERITAGE RULES

The Cultural Property Protection Act in Korea defines four different types of cultural properties: tangible cultural properties; intangible cultural properties; monuments; and folklore cultural properties.Footnote 91 According to Article 2(1)(2) of the Cultural Property Protection Act, the term “intangible cultural property” is defined as “among cultural heritage which have been transmitted throughout many generations, referring to those falling under any of the following items: (i) traditional performance and arts; (ii) traditional skills concerning crafts, art, etc.; (iii) traditional knowledge concerning Korean medicine, agriculture, fishery, etc.; (iv) oral tradition and expressions; (v) traditional ways of life concerning food, clothes, shelter, etc.; (vi) social rituals such as folk religion; (vii) traditional games, festivals, and practical and martial arts.” In addition, in accordance with Article 19(2) of the Cultural Property Protection Act, the administrator of the Cultural Heritage Administration (Cultural Property Administration [Munhwajaecheong in Korean]) shall actively endeavor not only to preserve cultural properties of humanity, including “cultural properties” registered with UNESCO as a world heritage site, an intangible cultural heritage of humanity, or a memory of the world but also to enhance the prestige of cultural properties around the world.

When it comes to the English translation of the Cultural Property Protection Act, the definition of intangible cultural properties, and the interchangeable use made of the terms “cultural properties” and “cultural heritage,” indicates the Cultural Property Protection Act’s lack of critical thought in terms of differentiating the term “cultural properties” from “cultural heritage.” To critique the legal terminology used in the Cultural Property Protection Act in terms of intangible cultural properties, the Act on Intangible Cultural Property needs to be scrutinized.Footnote 92

Property rules focus on who owns the intangible cultural property, whereas heritage rules are premised on how the archetype of intangible cultural heritage can be maintained and transmitted throughout several generations. The basic principle for the safeguarding and promotion of intangible cultural property is to maintain the archetype of intangible cultural property, taking into account the cultivation of national identity, the transmission and development of traditional culture, and the realization and enhancement of the value of intangible cultural property.Footnote 93 In this context, the legal term “intangible cultural property” needs to be changed to “intangible cultural heritage.”

HERITAGE RULES VERSUS RULES PROTECTING INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY

Traditional food and foodways can be related to intangible cultural heritage such as (1) traditional knowledge concerning Korean medicine, agriculture, fishery, and so on; (2) traditional ways of life concerning food; (3) social rituals; and/or (4) traditional festivals. The transmission of the archetype of cultural heritage is the key factor in order for the Korean government to approve cultural heritage as intangible cultural heritage. The term “archetype” means intrinsic features constituting the value of specific intangible cultural heritage.Footnote 94 Here, the wording “intrinsic features” means “intrinsic techniques, forms, and knowledge that should be transmitted, maintained, and practiced throughout several generations.”Footnote 95

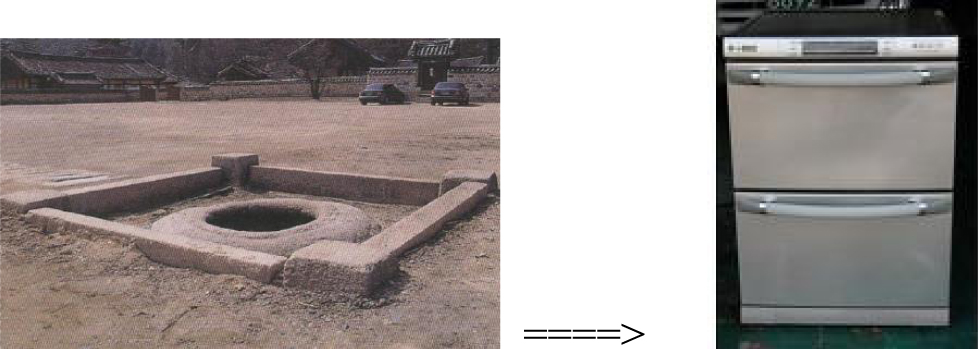

Whether or not intangible cultural heritage maintains and transmits its archetype is dependent upon whether its intrinsic features constituting the value of specific intangible cultural heritage have been identical throughout several generations. In this regard, there might be some discord between the preservation and promotion of intangible cultural heritage and the protection of its holders via the IP regime. At the outset, it appears not to be in line with the IP protection of its holders because the key factor in order to be approved as intangible cultural heritage is whether it can maintain and transmit its archetype. The term “intellectual property” refers to knowledge, information, and technology as the expression of ideas or emotions, the indication of business or goods, the varieties of organism or genetic resources, and other intangibles created or discovered by creative activities, experience, and so on of human beings, the value of property of which may be realized.Footnote 96 However, as long as the creations or creative activities of its holder(s) constitute its extrinsic features, the holder(s) can maintain and transmit its archetype and also be afforded IP protection. For example, when it comes to the royal cuisine of the Chosun Dynasty (No. 38 of National Intangible Cultural Property in Korea), how to make food and what to wear in the course of serving food are extrinsic features of the intangible cultural property. The archetype of royal cuisine of the Chosun Dynasty is to maintain and transmit its foodways and the constitution of its food (see Figure 5).

Figure 5. Royal Cuisine of the Chosun Dynasty (No. 38 of National Intangible Cultural Property), designated on 30 December 1970, Seoul, Korea (http://www.heritage.go.kr/heri/cul/culSelectDetail.do?pageNo=5_2_1_0&ccbaCpno=1271100380000 [accessed 20 September 2018]).

In this context, the Cultural Property Administration is encouraged to create advanced knowledge or craftsmanship from intangible cultural heritage in order to facilitate the transmission of the intangible cultural heritage and to take measures necessary to protect the intellectual property of its successors.Footnote 97 For this purpose, the most important task of the Cultural Property Administration is to clearly define the intrinsic features of each piece of intangible cultural heritage. When this has been carried out, its successors can develop trade secrets, patents, and so on of its extrinsic features and file for the registration of the GI of its intrinsic features as well. The Cultural Property Administration also needs to set up a specific roadmap and action plan to deal with the IP protection of holders and/or successors of intangible cultural heritage in light of different types of intellectual properties.

In this regard, the Cultural Property Administration has yet to show any concrete plan to protect the IPR of its holders and/or successors of intangible cultural heritage, with consideration given to the financial situation of its holder(s) or successor(s). For example, it might be appropriate for a local government to register a GI certification mark for a poor local community that has produced rice wine throughout several generations.

CONCLUSION

As mentioned above, traditional food and foodways can be protected by IP and non-IP regimes in active ways and also by IP regimes in passive ways. In this regard, traditional food and foodways can be preserved by developing national Internet portals that contain information about such traditional food and foodways. The national Internet portals relating to food and foodways play an important role in preventing individuals, legal entities, and foreign governments from patenting Korean traditional food and recipes. The lack of novelty that they will demonstrate will prohibit such entities from patenting the original form of the Korean traditional food and recipes. In addition, as shown in the kimchi case, the original and long-standing form of this traditional staple food can be listed on the Nice Classification, preventing foreign governments, legal entities, and individuals from obtaining a trademark of kimchi in foreign jurisdictions. It signifies that the internationally well-known food originally came from Korea.

The improvement of traditional food and foodways can be protected pursuant to patent law, unfair competition law, and the escrow system under the Act on Cooperation Promotion. In particular, traditional knowledge on Korean food and foodways can be good a subject matter for GI protection. From the perspective of comparativists, the protection of GIs for fishery products has not been fully developed. In this context, the Korean negotiators for FTAs with foreign countries need to pay attention to GIs for fishery products. Also, it should be noted that GIs have some bearing on the diversity of languages used in each country. To solve the problems related to GIs, bilateral international agreements such as the Korea–EU FTA, regional agreements, or multinational instruments may be reached.

However, those countries that have implemented GI protection in their legal systems, such as Korea and China, have experienced some troubles, resulting in the employment of competing, and sometimes conflicting, legal schemes. In this regard, the IP community needs to delve into substantive aspects of GIs protection, including the scope and level of protection for GIs, the conditions for the registration of GIs, and the duration of GI protection. Also, effective enforcement and consistent procedures that deal with disputes pertaining to GI protection need to be taken into account.

In addition, in terms of the active ways of protecting traditional food and foodways under non-IP regimes, the Cultural Heritage Protection Act and the Act on Biological Diversity can contribute to conserving and using traditional food and foodways on the basis of Korean administrative laws. When it comes to traditional food and foodways that do not fall within the definition of traditional knowledge under these laws, they can be protected by classic IP laws and/or as intangible cultural property. Another thing to be taken into account is that the Korean IP regime does not provide us with a clear picture of how to protect traditional knowledge as intellectual property.

In sum, in terms of the protection of traditional food and foodways as intangible properties, IP laws, cultural property protection law, and/or biodiversity protection law will serve to govern it, depending on who owns or holds the right to the traditional food and foodways or who can benefit from them. As far as intangible cultural property is concerned, it needs to be differentiated from intangible cultural heritage. Cultural property protection law refers to intangible cultural property at the national level and to intangible cultural heritage at the international level, which means that the law has failed to identify the implication of the bifurcated wording.

Whether or not intangible cultural heritage maintains and transmits its archetype is dependent upon whether its intrinsic features constituting the value of specific intangible cultural heritage have been identical throughout several generations. In this regard, there might be some discord between the preservation and promotion of intangible cultural heritage and the protection of its holders via the IP regime. However, as long as creations or creative activities of its holder(s) constitute its extrinsic features, its holder(s) can maintain and transmit its archetype and be afforded IP protection as well. For this purpose, the most important task of the Cultural Property Administration is to clearly define the intrinsic features of each piece of intangible cultural heritage. When this has been carried out, its successors can develop trade secrets, patents, and so on over its extrinsic features and file the registration of geographical indications for its intrinsic features as well. The Cultural Property Administration needs to set up a specific roadmap and action plans to deal with the IP protection of the holders and/or successors of intangible cultural heritage in light of the different types of intellectual property.