1. Introduction

This paper is an attempt to interpret what appears to be paradoxical behaviour among members of one speech community during the late stage of a language change in progress. Faced with historical evidence of the progressive decrease in the use of the inflected future in affirmative clauses in Québécois French,Footnote 1 earlier research revealed that many adult speakers in Montreal were in fact increasing its use significantly as they aged, apparently bucking the historical trend toward replacement by the periphrastic future (Wagner and G. Sankoff Reference Wagner and Sankoff2011, henceforward W&S 2011).Footnote 2

Examples of the alternation come from the 1984 interview of Germain T., who expresses his regret at having had to give up his engineering studies to go to work. He says he registers for classes every fall, but never has time to attend because he's too busy. He first expresses his plan to return to his studies with an inflected future in (1).

(1) Mais un jour je retournerai aux études, ça c'est sûr. [Germain T., 88, age 32, 1984, 485]Footnote 3

‘But one day I'll go back to my studies, that's for sure.’

After laughingly stating that maybe he won't be able to do it until he retires, he reiterates this desire a minute later, using a periphrastic future in (2).

(2) Je le sais pas, mais je vais retourner ça c'est sûr. [Germain T., 88, age 32, 1984, 486]

‘I don't know, but I'll go back, that's for sure.’Footnote 4

That aging speakers increased their use of the conservative variant, IF, was a result derived from a panel study that examined the speech of 59 Montrealers across the 13-year period between 1971 and 1984 (W&S 2011). The “use of the present to explain the past” (Labov Reference Labov and Heilmann1975) proposed that the speech of elders provided a window on the state of language at the time they acquired it, relying on the well-established finding that, in the main, mature adults retain their early-acquired linguistic systems fairly intact. Panel studies, re-sampling speakers as they age, can now trace the extent to which this is the case, investigating whether or not speakers have changed, and in what direction. Wagner and Sankoff (Reference Wagner and Sankoff2011) did exactly this for the case of the IF/PF alternation. Whereas the clear historical trend across more than a century has been the steady replacement of inflected future forms (IF) by periphrastic future forms (PF) in affirmative clauses, a substantial number of panelists registered a lifespan change in the opposite direction.

In the late 19th century, inflected futures in affirmative clauses were used at a rate of 36% in Québécois French (Poplack and Dion Reference Poplack and Dion2009: 572, Table 7).Footnote 5 By the late 20th century this rate had been dramatically reduced, with various studies finding rates between 10.5% (Grimm Reference Grimm2010) and 20% (Poplack and Dion Reference Poplack and Dion2009: 572, Table 7). The mean rate of IF use among the panelists we reported on in W&S 2011 went in the opposite direction, rising significantly from 10.0% to 15.5% over the 13-year period from 1971 to 1984. This surprising result demanded an interpretation. Although one possible explanation was that it indicated the beginning of a reversal of the historical trend itself, we argued instead that it represented individual linguistic lability associated with successive life stages. However, tracing speakers’ trajectories as they age reveals nothing about the relationship of these trajectories to the arc of a change occurring in the language. To integrate the two timescales of change and better understand the dialectical relationship between them requires establishing this relationship in real time. To accomplish this, a trend study is also necessary, re-sampling a community in comparable ways at two or more time intervals so that community change can be identified.

Previous combined panel and trend studies have reported a majority of speakers as showing stability as they aged, in some cases with substantial minorities who participated in ongoing change (e.g., Elliott Reference Elliott1999, G. Sankoff and Blondeau Reference Sankoff and Blondeau2007, Gregersen et al. Reference Gregersen, Maegaard and Pharao2009). But since retrograde behaviour on the part of aging speakers has, to our knowledge, only rarely been documented (e.g., Zilles Reference Zilles2005),Footnote 6 we undertook a preliminary trend analysis (G. Sankoff, Wagner and Jensen Reference Sankoff, Wagner and Jensen2012), using comparable samples of speakers recorded in the Montreal French project in 1971 and 1984, to establish the status of the earlier finding. The present paper updates that trend analysis and expands on a recently published summary (G. Sankoff Reference Sankoff2019a) to document community stability as a backdrop to the retrograde change on the part of individual speakers. Both the panel and trend participant samples were drawn from the Montreal French project, which we describe in section 2. In providing a more detailed comparison of the trend and panel findings for future temporal reference, we also situate them within a broader discussion of aging, style and linguistic conservatism.

The substantial reduction of IF in affirmative futures over more than a century establishes that the disappearance of IF is now a slow-moving, late stage change. As such, there is good reason to suppose that it may be more susceptible to social and stylistic constraints. The concept of change involving three stages in the status of variants has been widely used since its introduction by Labov (Reference Labov1972: 314): indicators, incipient linguistic innovations whose distribution is conditioned by speaker-related social variables such as social class and neighborhood (e.g., raising of (ej), the FACE vowel, in Philadelphia English; Labov Reference Labov, Eckert and Rickford2001); mid-stage markers, in which stylistic considerations also come into play (e.g., direct quotation in Puerto Rican Spanish; Cameron Reference Cameron2000); and long-established stereotypes, involving increased speaker awareness and often some conscious manipulation (e.g., non-rhoticity in Eastern New England; Stanford et al. Reference Stanford, Severance and Baclawski2014).

Without taking a position on whether IF is best understood as a marker or a stereotype,Footnote 7 as it slowly disappears, we should expect IF to exhibit both social class and stylistic variation. Social stratification, with highly-educated, upper and upper middle class speakers – speakers more likely to use inflected futures – has been clearly established in the IF/PF alternation (Emirkanian and D. Sankoff Reference Emirkanian, Sankoff, Lemieux and Cedergren1985: 198; W&S 2011: 300–303; Villeneuve and Comeau Reference Villeneuve and Comeau2016). However, previous studies of future temporal reference in French have mostly investigated stylistic variation by coding for T/V address pronouns (tutoiement vs vouvoiement) and/or formal subject pronouns (vous, nous, -autres). Differentiation by topic, such as informal discussion of family life versus formal discussion of language use or politics, has been undertaken only by Grimm (Reference Grimm2010), who does not report it as a significant effect, and Villeneuve and Comeau (Reference Villeneuve and Comeau2016), whose study of Vimeu French in Picardie found no significant stylistic effects.

In the present paper we introduce the Montreal French project and the demographics of the trend and panel participant samples in section 2. We then provide some background on future temporal reference in French (section 3), reviewing the linguistic and social predictors of IF selection. Section 4 describes our data selection, coding, and statistical modeling procedures, and the results are reported in section 5. We find that, in contrast to Grimm (Reference Grimm2010) and Villeneuve and Comeau (Reference Villeneuve and Comeau2016), IF in Montreal French is associated with more formal speech styles. However, the influence of formal style is significant only for older speakers. We discuss the broader ramifications of this finding in section 6, and section 7 provides a brief conclusion.

2. Panel and trend participant samples

All the data for the panel and trend studies of future temporal reference reported here were drawn from two phases of the Montreal French project. The first phase of this sociolinguistic study of Montreal French, undertaken by David Sankoff, Gillian Sankoff and Henrietta Cedergren in 1971, was structured to include native speakers of French across the social spectrum. A stratified sample of 120 speakers was drawn only from census tracts in which Francophones represented at least 64% of the population. Using a random number algorithm to locate addresses in a city directory, one of the five interviewers (native Québécois university students in their twenties) was directed to the chosen address, and continued on at adjacent addresses until a suitable interviewee was found. The collected data is known as the Sankoff-Cedergren corpus; details on its sampling, data collection and interviews can be found in D. Sankoff and G. Sankoff (Reference Sankoff, Sankoff and Darnell1973) and in G. Sankoff (Reference Sankoff, Wagner and Buchstalle2017).

This corpus (the Sankoff-Cedergren corpus of 1971) includes equal numbers of male and female speakers, four age groups (30 speakers each of ages 15–19, 20–34, 35–54, and 55+) and six socioeconomic levels based on census data on mean income by census tract (G. Sankoff and Cedergren Reference Sankoff and Cedergren1972). In subsequent analyses based on this corpus, social stratification was never assessed on the basis of the six-level mean income sampling grid, but on the personal data of the speakers themselves, including education and employment history.

Sixty of the speakers interviewed in 1971 were located, and re-interviewed in 1984 in a project directed by Pierrette Thibault and Diane Vincent, yielding the Montreal 1984 corpus (Thibault and Vincent Reference Thibault and Vincent1990) which includes 12 new speakers between age 15 and 30 in that year, also stratified by sex and socioeconomic background.

2.1 Panel sample

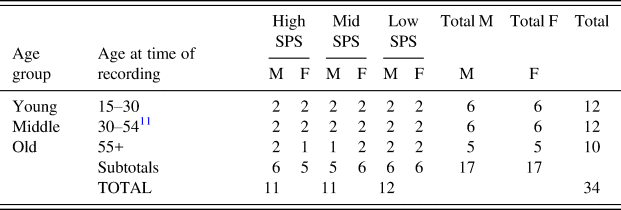

The Panel consists of 59 speakers, since the 1971 interview of one of the 60 re-interviewed speakers (speaker number 104) contained no futurate IF or PF tokens. Tables 1 and 2, reporting on the social dimensions of the speakers in the panel in the two study periods, are organized in terms of speaker Sex, three age Cohorts, and three levels of Socioprofessional Status (SPS) obtained by grouping the six-point occupational scale as fully explained in Thibault and Vincent (Reference Thibault and Vincent1990). High = speakers who were placed in categories 1 and 2 on the Thibault and Vincent (Reference Thibault and Vincent1990) occupational scale; Mid = 3 and 4; Low = 5 and 6. In Table 2, all speakers are (perforce) 13 years older. Social mobility of some speakers in the intervening years accounts for the slightly different numbers in each socioeconomic group between the two tables.Footnote 8

Table 1: Distribution of the 59-speaker Panel sample in 1971 by social characteristics.

Table 2: Distribution of the 59-speaker Panel sample in 1984 by social characteristics.

2.2 Trend sample

To accurately attribute any difference between 1971 and 1984 to community change, it was necessary that the trend comparison of the current paper provide the closest possible match with the Panel sample in terms of age, sex, and socioeconomic background of the speakers. W&S 2011 had identified a significant retrograde change among a subgroup of the panelists. What if this was a result of the entire community undergoing a similar change?

Constructing a trend sample was challenging in two respects. First, to match the Panel sample, it was necessary to use a grid with the same distribution of social characteristics. Second, whereas only one set of individual speakers was required for the Panel sample, a trend comparison meant that a different set of speakers had to be selected for each of the years 1971 and 1984, and matched with each other in social characteristics. To select the Trend sample of 1984, we used speakers’ linguistic marketplace ratingsFootnote 9 in combination with the SPS status ratings used in partitioning the panel sample. We were fortunate that the 1984 corpus contained the 12 new speakers aged 15–30 who were added to the study in that year. Evenly distributed across the three social class divisions, with two male and two female speakers in each, these young people were the obvious choice to constitute the youngest group in the 1984 Trend sample. Creating trend samples for the other two age groups was more difficult, since the 1984 speakers had to be selected from a smaller pool (the 60 speakers who had been re-interviewed in that year) and matched to appropriate social twins (Blondeau Reference Blondeau2001: 69) from the 1971 pool of speakers who had not been re-interviewed. For the middle and older age groups, we were able to match a sample of 22 individuals in each year. Thus the maximum number of speakers we were able to compare was 34 from 1971 and 34 from 1984, a total of 68 different speakers. Tables 3 and 4 indicate how the two Trend samples were structured, yielding equal numbers of men and women and closely comparable numbers in each of the age cohorts and SPS groups.Footnote 10 The mean age of the 12 youngest speakers (20.2 years), was identical in both samples, and quite close also for the oldest group: age 65.1 in 1971, and 63.5 in 1984. The middle groups were somewhat more widely separated: a mean age of 44.5 for the 1971 group and 37.2 for the 1984 group. Appendix A lists the 59 speakers in the Panel study; Appendices B and C list the speakers in the Trend 1971 and Trend 1984 samples respectively.

Table 3: Distribution of the 34-speaker 1971 Trend sample by social characteristics.

Table 4: Distribution of the 34-speaker 1984 Trend sample by social characteristics.

Having selected speakers in both 1971 and 1984 who satisfactorily matched the social characteristics of the Panel study (W&S 2011), these characteristics (speaker sex, SPS, and age group) will be examined along with a final social factor, speech style, in assessing how the trends in the community might or might not be commensurate with the linguistic usage of the panelists.

3. Future temporal reference

An inheritance from Latin, the inflected future (IF) has always been a part of French. However, the periphrastic future – inflected forms of the verb aller ‘to go’ + infinitive (PF) – was documented in the works of French grammarians as early as 1530, where it was said to connote incipient action, referred to as the futur proche ‘near future’ (Poplack and Dion Reference Poplack and Dion2009: 562, Table 4), According to Poplack and Dion, although a great variety of meanings have been attributed to both IF and PF since that time, in the majority of prescriptive grammars PF has been associated with proximate/immediate meanings. Ayres-Bennett (Reference Ayres-Bennett2004: 46) comments that the use of aller and s'en aller + infinitive is well attested in seventeenth-century texts.

Research on 20th century French reveals that the extent to which PF has come into competition with IF appears to be related to the attrition of its association with immediacy or “close” future. In most varieties of Acadian French, the frequency of IF is high, and the association of PF with near future is still strong (Chevalier Reference Chevalier, Dubois and Boudreau1996, King and Nadasdi Reference King and Nadasdi2003, Comeau Reference Comeau2015). King and Nadasdi (Reference King and Nadasdi2003) report a rate of 53% IF use for Acadian French. In two of the Acadian communities discussed in Comeau et al. (Reference Comeau, King and LeBlanc2016), the periphrastic future “has not spread to distal contexts” (Reference Comeau, King and LeBlanc2016: 21), whereas in the third, Les Iles de la Madeleine, they found “some weakening of the temporal distance effect” (Reference Comeau, King and LeBlanc2016: 21). Roberts (Reference Roberts2016: 300) notes that in the French of Martinique, PF is the most frequent form, “selected in 72.3% (N = 371) of all potential occurrences.” He states that “while the periphrastic future acts as the default option in the majority of time contexts, the inflected future functions as the marker of distal time” (Roberts Reference Roberts2016: 286). In Vimeu, Picardie, PF is used somewhat less frequently overall: at a rate of 62.2% (Villeneuve and Comeau Reference Villeneuve and Comeau2016: 327). Yet “with events anticipated to occur within a minute” (Reference Villeneuve and Comeau2016: 329), they observe that the PF is used at an extremely high rate (93.3%). They note that temporal distance was the only linguistic constraint found to be a significant predictor of IF use in their data (Reference Villeneuve and Comeau2016: 314).

Elsewhere in France, Roberts (Reference Roberts2012) found a rate of 41% IF use in a study based on a collection of 1980s recordings from two northern and two southern areas of the country. He reports that the temporal distance factor he used to distinguish proximate events from times farther in the future did not reach significance in his multivariate analysis, a finding that parallels Québécois French.

Yet from all available data, it is apparent that in contemporary French, the decline of IF is considerably more advanced in Quebec and Ontario (Deshaies and LaForge Reference Deshaies and LaForge1981, Emirkanian and D. Sankoff 1985, Blondeau Reference Blondeau2006, Poplack and Dion Reference Poplack and Dion2009, W&S 2011) than in France or Atlantic Canada. For Québécois French, researchers including ourselves have concurred in (a) calculating a rate of IF use far below rates found in France or Atlantic Canada; (b) reporting PF as the unmarked form; and (c) establishing a substantial area of overlap where the selection of form does not reference any meaning difference. As the unmarked neutral future, PF tends to occur in affirmative, informal, and bare (i.e., not adverbially specified) contexts (Poplack and Dion Reference Poplack and Dion2009: 579), and IF is clearly the minority variant.

That the selection of IF vs PF does not in itself convey a meaning difference in contemporary Québécois French is illustrated in examples (1) and (2) above, as well as in (3), with PF, and (4), with IF. In the latter cases, speakers use the verb falloir ‘to have to, to be necessary’ followed by the subjunctive, to refer to something that will ‘have to’ happen in the distant future.

(3) Fait que, il va falloir qu'ils fassent quelque chose. [Gilberte C., 77, age 43, 1971, 545]

‘So, they will have to do something.’

(4) Puisqu’il faudra que toutes nos affaires personnelles soient sur les ordinateurs. [Roland D., 73, age 64, 1984]

‘Since all our personal stuff will have to be on computers.’

3.1 Linguistic predictors of IF use

Given that previous studies of Québécois French have found that the traditional semantic motivation for selecting IF or PF – the association of PF with the futur proche – is not operative in this variety, what structural forces are known to condition the variation? The strongest constraint is negative polarity, since IF is virtually categorical in the negative in this variety.Footnote 12 The polarity constraint in Quebec French is so strong that all quantitative analyses since Emirkanian and D. Sankoff (Reference Emirkanian, Sankoff, Lemieux and Cedergren1985), who first identified it, have accordingly circumscribed the variable context to consist only of affirmative clauses.

With respect to other structural constraints, our 2011 analysis of the panel examined the effect of contingency of the clause, because contingent/uncertain contexts had been found to promote IF use (Poplack and Turpin Reference Poplack and Turpin1999, King and Nadasdi Reference King and Nadasdi2003, Blondeau Reference Blondeau2006). The combined panel data from 1971 and 1984 yielded enough tokens (N = 3658) to differentiate the contingency factor beyond the binary (+/− contingent) categorization employed by Poplack and Turpin (Reference Poplack and Turpin1999) and King and Nadasdi (Reference King and Nadasdi2003). W&S 2011 replicated on a much larger sample the findings of Blondeau (Reference Blondeau2006), whose analysis was based on twelve Montreal speakers and employed a finer-grained differentiation of linguistic contexts for the expression of contingency or uncertainty. Reporting on a logistic regression analysis of the panel data, we observed that, relative to non-contingent clauses, tokens in quand (‘when’) or other temporal adverbial clauses were the most favorable hosts for IF, followed by other kinds of contingent clause (e.g., those containing je sais pas ‘I don't know’, tant que ‘as long as’) and the apodoses of si (‘if’) clauses (W&S 2011: 296, Table 5). However, the effect of contingency on IF selection was not replicated in three other studies that examined it: Poplack and Dion (Reference Poplack and Dion2009) in Canada's National Capital Region of Ottawa-GatineauFootnote 13, Roberts (Reference Roberts2016) in Martinique, and Grimm (Reference Grimm2010) in Hawkesbury, Ontario. Nor has recent scholarship fully addressed the question of why uncertainty, when-clauses, if-clauses, etc. should have come to be associated with IF, although we offer some speculation in W&S 2011:297–298.

Several linguistic constraints examined in previous studies were not tested in W&S 2011, including adverbial specification, imminence and lexical frequency. Adverbial modifiers had not been found to significantly favour the selection of IF (e.g., King and Nadasdi Reference King and Nadasdi2003; Grimm Reference Grimm2010, Reference Grimm2015; Grimm and Nadasdi Reference Grimm and Nadasdi2011; Villeneuve and Comeau Reference Villeneuve and Comeau2016), and so we did not deem them relevant to our investigation. Temporal distance (also operationalized as imminence) was not considered, since as detailed above, it had proven to be significant only in Acadian French (King and Nadasdi Reference King and Nadasdi2003: 333) and in Picardie French (Villeneuve and Comeau Reference Villeneuve and Comeau2016: 329). As for lexical frequency, Poplack included this predictor in a study of future temporal reference in the Ottawa-Hull corpus, but reported that IF was “indifferent to token frequency, lexical identity, lexical strength, conjugation class or any other property relating to the verb” (Poplack Reference Poplack, Bybee and Hopper2001: 418).

Following prior studies, W&S 2011 did consider the effect of subject type on IF/PF variant selection. Poplack and Turpin (Reference Poplack and Turpin1999) and–Poplack and Dion (Reference Poplack and Dion2009) had found that IF occurred more frequently with the polite, singular addressee use of the second person plural form vous than with other grammatical subjects (an effect subsequently replicated only in Hexagonal French by Roberts Reference Roberts2012). Cross-tabulation of the data indicated that in fact, nous ‘we’, vous ‘you (pl./formal sg.)’, and nominal subjects all favored IF, whereas other pronominal subjects did not. This ‘formal subject’ type significantly increased the likelihood of selecting IF in the logistic regression model (W& S 2011: 296).

3.2 Social predictors of IF use

That subject type was found to condition variation in W&S 2011 was a clue to formality as an important factor. Subject nous has been virtually replaced by on ‘one’ in the vernacular (Laberge and G. Sankoff Reference Laberge, Sankoff and Givón1979), and second person singular vous is coded for politeness. Thus the finding that nous, vous, and nominal subjects favored IF was encouraging. That W&S 2011 found a strong effect of high SPS as well was not unexpected, more conservative linguistic behaviour being the norm among highly educated people with greater social capital, including “legitimate language” (Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu1977).

But our panel study also found, surprisingly, that IF use increased with aging over the 13 years between 1971 and 1984. Not only were the older speakers of the highest SPS group the most frequent users of IF in both study periods, but 18 of the 21 high SPS individuals in the panel actually increased their use of IF as they became older (W&S 2011: 303). Nor was increased use limited to the highest SPS group. Almost half of the speakers (17 of the 38) in the middle and lower SPS groups also registered an increase with aging.

Was this result possibly related only incidentally to lifespan change? Formal style would seem to go hand in hand with the increasing markedness of IF as it becomes less and less frequent. We wondered whether it might be that the 1984 interviews themselves elicited a more formal style across the board. Recent research has underscored the importance of untangling confounds between changes to the interview context and longitudinal changes in participant speech (see, e.g., Rickford and Price Reference Rickford and Price2013 on style-shifting versus lifespan linguistic change; Cukor-Avila and Bailey Reference Cukor-Avila, Bailey, Wagner and Buchstaller2017 on the “gap effect” of time lag between interviews; Gregersen and Barner-Rasmussen Reference Gregersen and Barner-Rasmussen2011 on changes in genre/topic; Wagner and Tagliamonte Reference Wagner, Tagliamonte, Wagner and Buchstaller2017 on interviewer familiarity, social media contact, and other considerations). The results of the panel study clearly pointed to the need to explore the effects of stylistic variation in the trend data, and to incorporate a measure of style into a re-analysis of the panel data.

3.3 Style

Stylistic variation was clearly “a promising avenue for future research on the IF/PF alternation” (W&S 2011: 291). Looking for a way to test whether panelists really did employ more formal language as they aged, or whether the 1984 interviews were more formal for topic- or interviewer-related reasons, we undertook to code all of the Panel and Trend data for style.

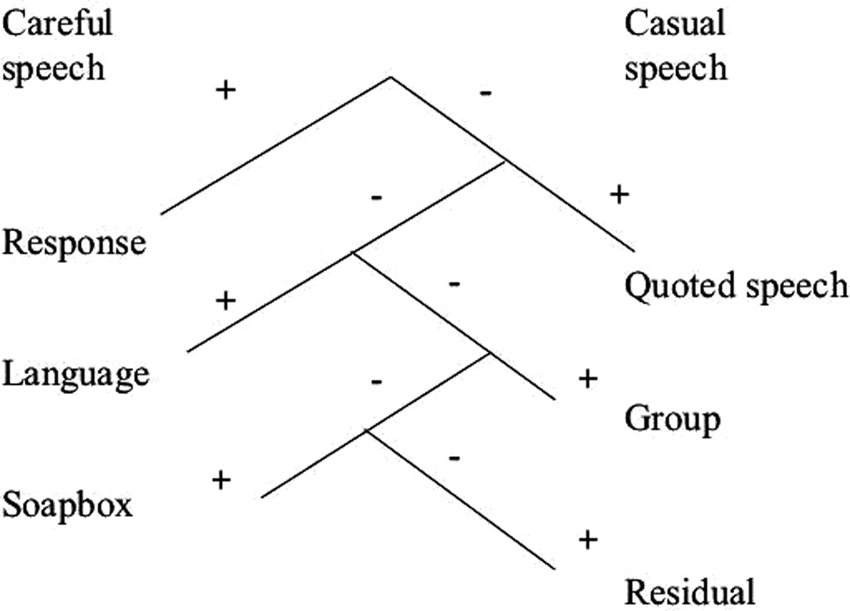

Style has become an increasingly rich site of research into sociolinguistic variation in general, thanks in part to the rise of ‘Third Wave’ approaches in recent years (Eckert and Rickford Reference Eckert and Rickford2001, Eckert Reference Eckert2012). The Third Wave conceptualizes linguistic variants as embedded within fields of inter-related indexical meanings ranging from the supralocal (‘educated’, ‘tough’) to the local (‘Wisconsin dairy farmer’, ‘newly Orthodox Jewish’). As variants are produced and perceived, speakers may project identities and stances, while hearers may interpret them in multiple ways. However, this analytical approach often relies upon the researcher having carried out ethnographic research in the speech community or having a close relationship with individual speakers. Interviewers in the 1971 Montreal study were members of the speech community, and shared knowledge of local events and history, but they were nevertheless interviewing people they had never met before, and could not supplement an interpretation of their speech patterns with additional personal information. For this reason, the present study instead adapts Labov's decision tree (Reference Labov, Eckert and Rickford2001), which codes for eight stylistic values in spontaneous speech in sociolinguistic interviews, as depicted in Figure 1. The style values developed by Labov are tailored specifically to the one-on-one, semi-structured format and topics of the sociolinguistic interview method employed in the Montreal French project (Labov Reference Labov, Baugh and Sherzer1984, Thibault and Vincent Reference Thibault and Vincent1990). Indeed, the 1971 research team had deliberately replicated, to the greatest extent possible, Labov's interview technique from his 1966 New York City study (Labov Reference Labov2006). The ‘decision tree’ coding scheme allows for comparison across speakers within a study, as well as across studies employing the same sociolinguistic interview method. While it might not capture the nuances of individuals’ multidimensional sociolinguistic identity construction or their moment-to-moment stances, it does provide a clear baseline, unidimensional measure of participants’ attention to their own speech (Labov Reference Labov1972), allowing us to test the hypothesis that formality is a predictor of IF use. Grimm (Reference Grimm2010) employed a similar topic-oriented approach to coding for style, using Mougeon et al.'s (Reference Mougeon, Nadasdi, Rehner, Martineau, Mougeon, Nadasdi and Tremblay2009) schema, but did not find it to have a significant effect on IF selection in Hawkesbury, Ontario. In what follows, we briefly outline our coding procedure.

Figure 1: Labov Reference Labov, Eckert and Rickford2001: 94, Figure 5.1).

In examining a particular token, the first decision taken was whether it occurred in the first sentence uttered by the interviewee after an interviewer's question. If yes, it was allocated to Response, on the Careful Speech side of the tree. If the token was not a Response, the next decision taken was whether it occurred in a sequence of reported speech, and if so, it was coded as Quoted Speech, likely to be more Casual. If not Quoted Speech, is the topic Language? Proceeding down the tree, the other stylistic categories were assigned at each junction point.Footnote 14 Ultimately for the statistical analysis (Section 4) we collapsed the categories into a binary variable, with levels Careful (consisting of the most socially marked contexts: Response, Language, Soapbox) and Other (Quoted speech, Group, and the Residual speech).Footnote 15

We decided that stylistic coding, being a matter of more subjective judgment than the other coding operations, would be better done by a single person, in this case the first author, who was most familiar with the speech community, the language, and the content of the interviews. During this new pass over the data, we also gave particular consideration to what we called ‘pseudo-imperative’ cases.

3.4 Pseudo-imperative futures

Following Fleischman (Reference Fleischman1982: 129), W&S 2011 had classified a small group of IF and PF tokens as volitional (W&S 2011: 283–284). Exhibiting the IF/PF alternation as futurates do, these tokens are not formally imperative, yet their pragmatic force is imperative rather than referential. Further, we observed a startlingly high percentage of IF in this sparsely occurring category, a result that led us to focus in on them in characterizing the inflected future as a marked form. After carefully examining all tokens with second person subjects and re-classifying those in which the pragmatic function was imperative, these were dubbed pseudo-imperatives. Of the 91 unique speakers whose speech was analyzed in this paper, 42 made use of pseudo-imperatives, for a total of 135 tokens in which IF occurs at a rate of 55%. This is more than triple the overall rate of 15.7% IF in the entire dataset. Examples include instructions to pets or family members, threats, and polite invitations to strangers. In (5), Édith G. quotes herself as instructing her husband regarding her own burial. Whereas the literal gloss is as a future, the illocutionary force is imperative. As we argue below, the resistance to the incoming tide of periphrastic futures in pseudo-imperatives provides a key to understanding how the disappearance of this vanishing variant has been so protracted.

(5) Mais j'ai dit à mon mari par exemple j'ai dit “Tu feras ouvrir le cercueil pour être sûr que je suis dans la boîte.” [Édith G., 44, age 72, 1984, 997]

‘But I said to my husband for example, I said, “You'll have to get the coffin opened to make sure that I'm in the box.”’

Later on in the interview, Édith cites her husband as having the opposite view regarding his own death:

(6) “Ah” il dit, “Vous ferez ce que vous voudrez quand je serai mort.” [Édith G., 44, age 72, 1984, 1058]

‘Oh, he says, “Do/You'll do whatever you (will) want when I'm dead”’Footnote 16

In (7), Lysiane B. cites the threat often issued to young women in former times, when having a baby out of wedlock could result in being thrown out of the family.

(7) Arrive-moi pas avec un paquet, parce que tu vas prendre la porte. [Lysiane B., 07, age 24, 1971, 1224]

‘Don't come home to me with a package [a baby], because you'll take the door [be thrown out; ‘shown the door’].’

At the end of his 1971 interview, Paul G. cordially invites the interviewer to bring her husband around to chat with him in (8). Paul's politeness here is underscored by his use of formal vous to the interviewer. Despite their being age-mates, in their mid-twenties, and despite his having warmed to the interview and spoken openly and at length, Paul (a bakery worker) clearly feels this deference is due to a young woman of her social status (a well-dressed student) whom he has just met. His use of IF is consonant with formality in (8).

(8) Vous amènerez votre mari je vas lui parler des vieilles affaires. [Paul G., 02, age 25, 1971, 2356]

‘(You will) Bring your husband around and I'll talk to him about the old days.’

Incorporating the 135 new ‘pseudo-imperative’ tokens into the combined Trend and Panel datasets of more than 5700 tokens did not move the needle on the basic results of the other factors shown to be significant in the alternation for the Panel in W&S 2011. Those new results, along with those for the Trend dataset, are provided in section 5. First, in the next section, we describe the data and methods on which our current analysis is based.

4. Data and methods

As briefly reported in G. Sankoff (Reference Sankoff2019a) and discussed at further length above, the present paper required a re-coding and re-analysis of the W&S 2011 dataset (The Panel dataset). Additionally, the G. Sankoff et al. Reference Sankoff, Wagner and Jensen2012 dataset (The Trend dataset) was expanded and coded afresh. As in procedures described in W&S (2011: 279–284), all affirmative futurate clauses were extracted, discarding the large number of habituals and hypotheticals that also exhibit the IF/PF alternation, as well as frozen forms, false starts, and priming by the interviewer. Additionally, all tokens were coded for style. A total of 5715 tokens (3656 for the Panel,Footnote 17 2059 for the Trend) were retained for quantitative analysis. We conducted mixed effects logistic regression in the R statistical environment (R Core Team 2013), using the glmer function in the lme4 package (Bates et al. Reference Bates, Levy, Scheepers and Tily2015).Footnote 18 P-values were obtained using the lmerTest package (Kuznetsova et al. Reference Kuznetsova, Brockhoff and Christensen2017). The alternation between IF and PF, or Tense, was the dependent variable, with realization of IF as the variant of interest, and Speaker was included as a random intercept.

The fixed predictors, with their levels and a reference level for each, are given in rows 1–7 of Table 5. In rows 1–4 are listed Contingency with levels contingent ,quand, and independent; Sex with levels male and female; Year of Recording with levels 1971 and 1981; and Style with levels careful and other. In contrast with the W&S 2011 analysis, we did not include Subject type as a predictor, because the tokens in the Trend dataset (a very small number, only 168) were very unevenly distributed across the other predictor categories. In any case, as discussed earlier, the contrast between ‘formal’ and ‘other’ contexts for this factor is clearly related to speaker style, which is already accounted for by the better-distributed Style predictor.

Table 5: Fixed predictors for multiple logistic regression.

In rows 5 and 6, we use two different age-related labels for the Trend and Panel datasets. In row 5, for the Panel sample, speakers aged 15–30 in 1971 belong to a consistent ‘Cohort’ that is revisited 13 years later in 1984 when the same individuals are all 13 years older. We observed through cross-tabulation that Age/Cohort and Socioprofessional status (SPS) were not independent, and so these were a priori merged into a set of interactive predictors (Older + HighSPS, etc.). In row 6 for the Trend sample, ‘Age group’ indicates that we are comparing speakers aged, say, 15–30 years old in 1971 with their counterparts of the same age in 1984. Pearson correlations of the fixed effects for the Panel dataset in an initial model found that some of these predictors were correlated >0.5. We subsequently collapsed them into three levels, shown in row 5 below: Two polar groups (Younger + LowSPS, Older + HighSPS) and a residual level representing all other tokens. Here, ‘Older’ is all panelists in the ‘Old’ cohort of Tables 1 and 2 above, and ‘Younger’ combines panelists in the ‘Young’ and ‘Middle’ cohorts of Tables 1 and 2.

For the Trend dataset, we employed a similar process of refining the age groupings. In an initial model, Pearson correlation tests showed that the Middle and Old age groups (Tables 3 and 4) were correlated >0.5. We therefore collapsed them into a single Older group. Unlike the Panel dataset, speaker age and socioprofessional status were not found to be highly correlated in our inspection of cross-tabulations, and so they were entered as independent predictors Age group and Socioprofessional status (SPS) in the final regression (rows 6 and 7).

5. Results

We begin by returning to a question we posed in section 3.3. Did the panelists use more IF in their 1984 interviews simply because those interviews were inherently more formal than in 1971? To test this, we compared the distribution of careful vs residual style in the Panel dataset, as well as in the Trend dataset and the combined datasets (i.e., for the 91 unique individuals) for good measure. Chi-square analyses with Yates continuity correction determined that at least for occasions when speakers were referring to the future, the opposite was true. The proportion of careful style tokens was significantly higher in 1971 than in 1984 in both the Panel and Trend datasets. For the Panel data, X2 (1, N = 3656) = 35.072, p < .0001. For the Trend data, X2 (1, N = 2059) = 41.023, p < .0001. For the combined data, X2 (1, N = 4614) = 81.969, p < .0001. We can therefore exclude the possibility that the panelists’ greater use of IF in 1984 was in any way the result of increased formality.

The overall rates of use of IF for the Panel are virtually identical to those reported in W&S 2011. Panelists’ rate of IF use in 1971 was 11.0% (135/1227) and rose to 16.5% (401/2429) by 1984. The increase was statistically significant, X2(1, N = 3656) = 19.76, p < .0001. For the two years of recording in the Trend sample, the rates of IF use were virtually indistinguishable, less than one percentage point apart: 15.5% in 1971 (117/754) and 16.2% (211/1305) in 1984. As a long-term change that has been proceeding very slowly over the past century (Poplack and Dion Reference Poplack and Dion2009), it is not surprising that in the short span of 13 years, we have registered stability. Thirteen years is not, however, such a short time in a person's lifespan, and the increase in rates for the panelists over this same span as established in W&S 2011 was astonishing, as it runs counter to the long-term direction of community change.

Regression analysis of the Panel and Trend speakers can better elucidate the motivations for this apparent mismatch between community- and individual-level linguistic behavior. Turning to the output of the regression on the Panel data, as shown in Table 6, we see a confirmation of the results of W&S 2011. We included all of the fixed predictors, as well as an interaction term between Cohort + SPS and Style, because previous studies have shown that speakers of high social status are more likely to use a formal speech style that favors variants that are on the decline in the spoken language, such as negative ne (G. Sankoff and Vincent Reference Sankoff and Vincent1977, Ashby Reference Ashby2001; G. Sankoff Reference Sankoff, Lightfoot and Havenhill2019b) and IF (Villeneuve and Comeau Reference Villeneuve and Comeau2016).

Table 6: Mixed effects logistic regression on the realization of IF (vs PF) for Panel speakers (n = 59).

*** p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01, * p < 0.05, . < 0.1.

The model output reveals main effects of Year of recording, Cohort + SPS and Contingency, which were in the directions previously observed. IF was employed by the panelists significantly more frequently in 1984 than in 1971. Their use of IF is further stratified by age and social class, with the two polar groups – Younger + LowSPS, Older + HighSPS – using proportionally less and more IF respectively than the residual reference group. Contingent clauses strongly favour IF. We also confirm that speaker sex does not significantly constrain IF use for the Panel. Finally, whereas W&S 2011 found an effect of style via the Subject Type proxy factor, here there is no main effect of style. However, there is an interaction between style and the crossed Cohort + SPS group, whereby IF is significantly more likely to occur in careful style, although only within the Older + HighSPS group.

Having re-established that IF use increased as the panelists aged by 13 years, we turn now to the Trend dataset. Once again, all fixed predictors were entered in the model, along with an interaction term between Age group and Style. Table 7 shows that in contrast to the Panel results, Year of Recording does not significantly affect IF use. That is to say, that overall employment of IF remained stable in the Montreal French speech community over 13 years, and thus the panelists’ increasing use of IF did indeed represent retrograde linguistic behaviour over that period of the panelists’ lives. Otherwise, the results parallel those of Table 6: Older speakers in both 1971 and 1984 were significantly likelier than Younger speakers to use IF, as were speakers (regardless of age) in the High SPS group. IF use is more likely in careful speech style, but only for Older speakers; speaker sex has no significant effect on the IF/PF alternation; contingent clauses (si, quand, etc.) strongly favour IF.

Table 7: Mixed effects logistic regression on the realization of IF (vs PF) for Trend speakers (n = 68).

Having undertaken the Trend study in order to assess whether this retrograde lifespan changes with aging was perhaps a product of retrograde community change, we can assert that this is not the case. We can also dismiss the concern that the increase reported for the 59 panelists might be spurious, since the community rates provided by the matched Trend samples did not show the same effect.

6. Discussion

In the following sections, we discuss various factors that may be determinative of the change seen in the Panel subjects’ use of IF over time.

6.1 Individual retrograde change

In the present paper, the diagnosis of individual retrograde change over the lifespan for IF (W&S 2011) was confirmed by a detailed examination of data from a trend sample that showed community stability over the same period. Individual change was particularly evident among the older, higher social class members of the panel, who increased their use of the outgoing IF variant considerably over the 13 years of the study. Prior work on the same Montreal French data had identified two other types of language change over the life course. As discussed in G. Sankoff (Reference Sankoff2019a), individuals remained stable with respect to their alternation between avoir ‘to have’ and être ‘to be’ auxiliaries in the composé (‘perfect’) tenses. Yet for the community-wide adoption of dorsal /r/, a substantial minority of individuals increased their use of this phonetic variant in line with the direction of change active among younger members of the speech community. The third trajectory, retrograde change, represented by individuals’ increasing use of the inflected future, appears to be quite rare, although at present it is unclear whether this is simply an artifact of the paucity of sociolinguistic panel research. Regardless, several other examples have come to our attention.

In the Portuguese of Porto Alegre, Brazil, Zilles (Reference Zilles2005) tracked the ongoing change involving the replacement of first person plural nos by a gente in a panel study using data from the 1970s to the 1990s. For her 13 panelists, 11 remained stable over time, but two older women significantly increased their use of the outgoing nos. MacKenzie (Reference MacKenzie2017) provides a detailed account of /r/-tapping by the British television presenter and naturist David Attenborough in the 1950s versus the 2000s, showing that Attenborough increases his use of the upper class, conservative tap variant, contra the direction of community change, although only in high-frequency collocations.

Two other studies have each highlighted an individual, pitting salient features associated with local dialects against wider national norms. Buchstaller et al. (Reference Buchstaller, Krause, Auer and Otte2017) also anchored their panel (n = 6) in a trend study, in this case of Tyneside, England. Panelists were re-interviewed after a 42-year interval (1971/2013). In their examination of the FACE vowel, they found that despite the existence in the community of “two ongoing trends toward the use of supra-local variants”, one speaker in his 60s exhibited a retrograde change in 2013 toward the local marked variant. Shapp et al. (Reference Shapp, Lafave and Singler2014) looked at bought-raising (/ɔ/-raising) and rhoticity in the speech of U.S. Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg in the 1970s (when she was a lawyer) and in the 1990s–2010s (after she became a justice). Like the Tyneside individual in Buchstaller et al. (Reference Buchstaller, Krause, Auer and Otte2017), Ginsburg significantly increased her use of these two socially marked New York City features as she aged.

In the absence of longitudinal data for individuals, analysts have occasionally inferred retrograde change by other means. Prichard and Tamminga (Reference Prichard and Tamminga2012: 95), for example, in a study of the vowel systems of eight Philadelphia speakers, found that those with the most ‘outwardly-oriented’ higher education background (e.g., attended a college with a nationwide applicant pool) “correct away from negatively-evaluated features” such as the tense short-a (TRAP, /æ/) pattern. The authors are careful to point out that since they have data from only one point in the speakers’ lifespans, they cannot “discern whether this is a change which occurs only after enrollment, or whether it might begin earlier, in fact being driven by the speaker's aspirations of upward mobility.”

6.2 Acquisition of affirmative IF

We again employ a note of caution here, pointing out that the youngest speakers in our study were 15 years old at the time of recording. Despite its longitudinal depth, the combined 1971 and 1984 corpus sheds no light on participants’ linguistic experiences prior to that age. We can be sure that our panelists acquired IF as children, because of its robust presence in negative clauses. But in affirmative clauses, it seems that on average children would have received, maximally, exposure to only 10–15% IF, plus some additional input from frozen expressions containing IF such as on verra ‘we'll see’; but these, too, are infrequent. Yet by the time individuals are in their mid-teens, they can actively produce affirmative IF clauses, as in (9).

(9) Peut-être, peut-être là je prendrai une année ou deux pour travailler. [Mélanie L., 131, age 15, 1984, 215]

‘Perhaps, perhaps I will take a year or two to work.’

Additionally, the co-occurrence of peut-être (‘perhaps’) with IF in this example is noteworthy. Does this represent Mélanie's acquisition of the contingency constraint? The answer seems to be yes. In the combined Panel and Trend datasets, for speakers aged under 18 at the time of recording, there are only 30 tokens of IF. Of these, the majority (20/30) are in contingent clauses. Somehow, these young speakers had had enough exposure to affirmative IF to employ it actively in their repertoire by adolescence, following the community constraint modeled by their elders: contingent clauses favour its use.

But do most children acquire the stylistic constraints on affirmative IF, especially if they are concentrated among older, high status speakers? As demonstrated by Smith et al. (Reference Smith, Durham and Fortune2007), basic stylistic contrasts are present in child-directed speech and their proportional distribution is matched by children. In affirmative clauses, children might adduce that the frozen expressions they hear adults use, although somewhat rare, are formal in flavor. Higher SPS children might get just enough exposure to adults’ affirmative IF exemplars to infer that their distribution is skewed not only toward contingent events, but toward careful (formal, polite) language.Footnote 19 Thus we speculate that prior to adulthood, most Montreal Francophones have (a) little passive exposure to formal-style IF use and (b) even fewer occasions to produce it. We now turn to the later stages of adulthood and consider the social motivations that might push individuals – especially those in higher status groups – in a direction that is orthogonal to community language change.

6.3 Senior peer influence

Peer linguistic influence is typically associated with the lower end of the age spectrum, as evidenced by the wealth of research on pre-teens and teenagers (see Kirkham and Moore Reference Kirkham, Moore, Chambers and Schilling2013 for an overview). Clearly, peer influence among youth is a major mechanism of language changes in progress: particularly those that are incipient or mid-trajectory (indicators, perhaps also markers), and below the level of social awareness or public discourse. But peer social influence is not confined to the early years (e.g., Degnen Reference Degnen2007, Alwin et al. Reference Alwin, Felmlee and Kreager2018). Despite people's reduced linguistic malleability well past the critical period, we suspect that accession to older life stages may at the very least offer speakers the opportunity to change the way they display different aspects of previously-acquired repertoires. Just as children look to slightly-older peers as (linguistic) role models (Eckert Reference Eckert2011), when people reach mid-to-late adulthood, they are susceptible to peer influence from slightly older adults as they are socialized into new groups: at work, in community organizations, among fellow parents, etc. We refer to this as senior peer influence.

To our knowledge, the sociolinguistic consequences for language change of peer relations in adult life have received little attention. Speakers may join new communities of practice well after the end of the critical period, as demonstrated in Eckert and Wenger's (Reference Eckert and Wenger1994) research on the workplace, and in Rose's (Reference Rose2006) study of card players and volunteers in a Wisconsin senior center, but studies like these are still rare. This is particularly true for older age speakers. As Pichler et al. (Reference Pichler, Wagner and Hesson2018: 6) point out:

We know little about how older adults use sociolinguistic indexicality as a symbolic resource, or how they in turn perceive indexical meanings. Yet this information is essential for understanding generational language change, such as when a variant's indexical meanings shift over the generations, prompting a rise or fall in its frequency over time. There are also implications for the study of language change over the lifespan since the social meanings of a variant may shift for individuals as they age.

The interaction between style, age and social class in the present study would seem to underscore this point. Increasing use of IF was not associated with increasing age, increasing social status, or formal speech style as independent parameters. IF was not likelier to occur in the careful speech of high-status speakers of all ages. Rather, this confluence emerged as high-status speakers aged. It seems that the use of IF for formal stylistic purposes is a skill that speakers, especially high SPS speakers, employ more freely when they have acquired senior status. In our Panel sample, some of the older speakers had experienced a reduction in their social networks, resulting from widowhood, adult children moving away, etc., without making new social contacts. One panelist, Charles P., whose speech in later life was marked by an increase in many formal features, bemoaned the social isolation he had experienced after a substantial promotion had robbed him of the companionship of his former workmates and provided no substitutes among his new peers. In a case like this, senior status on its own (in his case, elevation to the status of a judge) has apparently encouraged Charles to deploy previously little used features of his repertoire with abandon. Discussing his own salary, he has this to say (formal features bolded):

(10) Même si le salaire n'est peut-être pas ce que l'importance de la responsabilité voudrait qu'il soit, c'est un salaire néanmoins qui est un salaire important. [Charles P., 117, age 46, 1995, 87]

‘Even if the salary is not perhaps that which the importance of the responsibility might wish it to be, it is a salary nevertheless which is a substantial salary.

In this passage, Charles uses the extremely rare negative particle ne, as well as the subjunctive soit, and an embedded clause headed by ce que ‘that which’. The entire fluently produced sentence contains four clauses, two of which are embedded. In his first interview at the age of 22, there is no use of ne nor of the complex syntax we find here.

Peer influence and status change among older adults are underexplored mechanisms of language changes at the end of their trajectories: maintaining conservative remnants of the outgoing variant in the community repertoire. This slows down the disappearance of that variant, possibly arresting the completion of the change indefinitely, and resulting in a ‘long tail’.

6.4 The long tail

Studies of lingering late-stage changes can illuminate an important question: Why do some ongoing language changes eventually become stable sociolinguistic variables, instead of disappearing entirely? We suggest that both linguistic and social conditions must be right, for this to occur (see also Van Herk and Childs Reference Van Herk, Childs, Cacoullos, Dion and Lapierre2015; José Reference José2010).

First, the older variant in the community must occur at a frequency level high enough to prevent it from disappearing entirely. Thus, although the inflected future has virtually disappeared in affirmative contexts, it is robustly maintained in the negative, providing continued exposure to the form for future generations. Similarly, although the negative particle ne is rare in spontaneous speech in Montreal, speakers have access to it in writing. It is uniformly present in the standard written French encountered in, for example, daily print and online newspapers. And in Acadian French, the marginal -ons form of the first person plural has seemingly persisted due to its phonological parallelism with another, more robust dialectal form, the -ont suffix in third person plural (King et al. Reference King, Martineau and Mougeon2011, King Reference King, Montgomery and Moore2017: fn 6).

Second, the older variant must take on social meanings that are still valuable in the community: to signal developmental maturity, or to mark social status, formal style, politeness, or a registered local identity. These meanings may be of particular utility to older adults, who may in turn create new additions to the variant's indexical field. Indeed, Rose (Reference Rose2006: 2) emphasizes that older speakers “are producers of social meaning in the present.” This second set of conditions is more tenuous. The older variant may come to sound archaic and precious, and thus be abandoned. But if the cultural conditions are such that ‘acting one's age’ as an adult is valued, such as in high status groups, in the workplace, or in other places where formal behaviour persists, then senior peer influence will create stability rather than the completion of a late-stage change.

Third, we suggest that the change must be sufficiently slow-moving – at least in its late stages – to be indistinguishable from a stable variable, at least from the perspective of a speech community member at that point in time. Diagnosing the lifespan increase in IF use as individual retrograde change implies that speakers who exhibit this behaviour are turning against the tide of community change. But we now reconsider this designation more carefully. While it correctly describes individuals’ lifespan linguistic trajectories with respect to a centuries-long, documented decline in IF use, to the speakers themselves this decline is inaccessible. As Labov (Reference Labov1989: 85) observes, it can be said that children do not know the history of the language they are learning – in this case, they do not know that IF has proportionally decreased over time relative to PF – yet it can also be said that “the child is a perfect historian of the language”. That is, since the human lifespan is shorter than the long decline of IF, individual Montreal French speakers have no access to the kind of ‘age vectors’ that provide direction to adolescents as they advance a community language change in progress (Labov Reference Labov2007, Tagliamonte and D'Arcy Reference Tagliamonte and D'Arcy2009, Stanford et al. Reference Stanford, Severance and Baclawski2014). Nonetheless, speakers of Montreal French are immersed in the variable IF/PF patterns that represent its diachronic evolution (i) from a temporal distance indicator to its association with negative polarity and contingency, and (ii) from default futurate form to social marker of older age, higher status, and increased formality (much like tapped /ɹ/ in England). In this respect, Montreal francophones inherit the remnants of a change in progress as if it were an effectively stable sociolinguistic variable, akin to the (ing) and (t,d) alternations of English (Labov Reference Labov1989). It seems that they then reify these linguistic and social associations. In so doing, we could argue that they are exhibiting age grading – a regular, generationally cyclic relationship between age and a sociolinguistic variable (Wagner Reference Wagner2012) – rather than individual retrograde change. This inspires further questions: Should our nomenclature for the relationship between individual and community language change be expressed from the point of view of the language speaker or of the analyst? How slow must a change be for it to be subject to evaluation by speakers as a stable variable? For example, the decline of post-vocalic /ɹ/ and raised bought /ɔ/ in New York City have been relatively swift – documented over mere decades of recent history, not over centuries (Shapp et al. Reference Shapp, Lafave and Singler2014). Has Ruth Bader Ginsburg been aware, at any level, of that decline, or are those features, to her, stable stylistic options? Alternatively, in a late stage change, perhaps the boundary between slow progress and stability, or between retrograde individual behavior and age grading, is blurry enough to resist neat categorization at all. We leave these questions for future consideration, but note that there is still much work to be done in the investigation of stable (or nearly stable) sociolinguistic variables. As Labov pointed out: “there is something even more challenging and puzzling than change, and that is the absence of change” (Labov Reference Labov1989: 87). Determining how and when language changes stabilize, in the individual and in the community, remains a challenge for future research.

7. Conclusion

An angle of vision that combines the perspective of language change as an historical phenomenon with the changes involved in individual language learning, maturation, and aging faces the challenge of incommensurable time spans. A language change may take centuries to come to completion; individual lifespans are more appropriately measured in decades. Similarly, the forces that influence language change include macro-social events like wars, conquests, and migrations that may not be experienced by individual people. And, people may not be aware that competing variants in their own speech communities represent one phase in a historical arc that began long before they were born.

For longitudinal research on language change, studies combining trend and panel surveys are the gold standard. They can confirm or refute a hypothesis of language change in progress over time; they can determine the rate of change in a speech community; and they can elucidate the multiple ways in which individual linguistic trajectories intersect with community linguistic change. With time, they may advance our understanding of how late-stage language changes are interpreted and re-interpreted by members of the speech community over generations and over individual lifespans. We have been fortunate to have the Montreal French panel and trend corpora at our disposal. Panel studies in particular are challenging to undertake, and the data they yield can be sparse and hard to interpret (Wagner and Buchstaller Reference Wagner and Buchstaller2017, Beaman and Buchstaller to appear). Yet as they grow in number, the conclusions we can collectively draw from combinations of hard-won trend and panel research will continue to solidify.

APPENDIX A

List of 59 speakers selected for the Panel sample, with demographic information for speaker sex, speaker socioprofessional status (SPS), age cohort, and year of recording. Speaker ID numbers refer to those assigned in the Montreal French project (see Thibault and Vincent Reference Thibault and Vincent1990).

APPENDIX B

List of 34 speakers selected for the 1971 Trend sample, with demographic information for speaker sex, speaker socioprofessional status (SPS), and age group. Speaker ID numbers refer to those assigned in the Montreal French project (see Thibault and Vincent Reference Thibault and Vincent1990).

APPENDIX C

List of 34 speakers selected for the 1984 Trend sample, with demographic information for speaker sex, speaker socioprofessional status (SPS), and age group. Speaker ID numbers refer to those assigned in the Montreal French project (see Thibault and Vincent Reference Thibault and Vincent1990).