The beneficial effects of dietary phospholipids (PL) on growth and survival have been demonstrated in the larval and juvenile stages of aquatic livestock species( Reference Coutteau, Geurden and Camara 1 , Reference Tocher, Bendiksen and Campbell 2 ). The beneficial effects of PL were not solely because of enhanced emulsification and digestion of lipids( Reference Koven, Parra and Kolkovski 3 – Reference Kasper and Brown 5 ), but also because of increased efficiency of dietary fatty acids and lipid transport from the gut to the rest of the body, potentially through enhanced lipoprotein synthesis( Reference Hadas, Koven and Sklan 6 – Reference Olsen, Tore Dragnes and Myklebust 8 ). Salmon and white sturgeon weighing more than 10 g were not reported to have a dietary requirement for PL, although this is potentially because of the short duration and limited assessment methods used in these preliminary studies( Reference Hung and Lutes 9 , Reference Poston 10 ). To our knowledge, there have been no further studies investigating PL requirements in adult or individual fish weighing more than 50 g. Dietary PL has been shown to alleviate signs of liver disease in human and animal studies( Reference Ipatova, Prozorovskaia and Torkhovskaia 11 – Reference Lee, Nam and Chung 13 ). Meanwhile, the carbohydrate- and lipid-rich diets widely used in fish farming owing to shortages of protein resources commonly lead to the accumulation of ectopic fat, liver fat, mesenteric fat and also fat in the muscles of larger fish( Reference Du 14 , Reference Weil, Lefèvre and Bugeon 15 ). Therefore, dietary supplementation with PL is potentially beneficial in the larger juvenile and adult fish that are increasingly affected by liver disease and metabolic disorders.

Previous research has commonly used crude mixed preparations of PL, particularly soyabean lecithin and other plant PL or egg-yolk lecithin. As these different sources are enriched in varying types of PL, it has been difficult to clarify which PL classes are responsible for the beneficial effects( Reference Tocher, Bendiksen and Campbell 2 ). Phosphatidylcholine (PC), the most abundant class of PL in the diet, shows the greatest effect on fish larval performance( Reference Coutteau, Camara and Sorgeloos 16 ), with other studies reporting that supplementation with PC contributes to survival and reduces larval deformities( Reference Hadas, Koven and Sklan 6 – Reference Sotoudeh, Kenari and Rezaei 19 ). The expression and regulation of key genes involved in lipid metabolism in response to dietary PC has not previously been studied in fish, particularly in adult fish.

Fish possesses a similar set of enzymes involved in lipid metabolism to mammals, including lipoprotein lipase (LPL), a key enzyme in lipid deposition and metabolism( Reference Albalat, Sánchez-Gurmaches and Gutiérrez 20 ), hormone-sensitive lipase (HSL), an enzyme involved in lipolysis( Reference Lampidonis, Rogdakis and Voutsinas 21 ), fatty acid synthase (FAS), involved in lipogenesis( Reference Wakil 22 ), and phospholipase A2 (PLA2), which catalyses the hydrolysis of membrane glycero PL( Reference Boulanger, Labelle and Khiat 23 ). Previous research in Otsuka Long-Evans Tokushima fatty rats has shown that the effects of dietary PC were attributable to the suppression of FAS activity in the liver( Reference Shirouchi, Nagao and Inoue 24 ). Injection of PC also increases HSL transcription in mouse fat tissue( Reference Won, Nam and Lee 25 ), and has suggested that secreted PLA2 has an important role in hepatic uptake and metabolism of PC( Reference Robichaud, van der Veen and Yao 26 ).

Tilapia is becoming one of the most important and fastest-growing fish species in aquaculture. The Genetically Improved Farmed Tilapia (GIFT) strain is a new nationally certificated strain selected over 14 years and nine generations from the base strain of Nile tilapia( Reference Li, Tang and Cai 27 ). The GIFT strain is among the most successful of the introduced farmed tilapia in China owing to its strong adaptability, rapid growth, high fecundity and broad diet. On the basis of weight gain and feed efficiency, Kasper & Brown( Reference Kasper and Brown 5 ) concluded that PC is a beneficial nutrient for juvenile tilapia with an initial body weight of 12·4 g and recommended that purified diets fed to juveniles include 15 g PC/kg diet.

In the present study, we aimed to investigate the effects of varying levels of dietary PC on growth performance, tissue composition and the fatty acid profile in the tissues of adult GIFT strain Nile tilapia fish. In addition, we determined the effect of dietary PC on the expression of enzymes involved in lipid metabolism. We hypothesised that dietary PC has beneficial physiological effects in adult Nile tilapia, mediated through the altered expression of lipid enzymes.

Methods

Diets

Six semi-purified diets were prepared. Casein, gelatin and soyabean meal, which were the main protein sources, provided 30·6 % dietary protein (the protein requirement for maximum growth performance of large tilapia is approximately 30 %)( Reference Hafedh 28 ). Soyabean oil and PC were used as lipid sources; they provided 7·6 % dietary lipid for large tilapia( Reference Tian, Wu and Yang 29 ). The diets were supplemented with different levels of dietary PC – 0, 2·5, 5·0, 10·0, 20·0 or 40·0 g/kg diet – and the dietary lipid levels were adjusted by the soyabean oil levels. The analysed level of PC in the six diets was 1·7 (the control group), 4·0, 6·5, 11·5, 21·3 and 41·0 g/kg diet. The diet preparation was conducted as previously described( Reference Tian, Wu and Yang 29 ). The ingredients and proximate composition and fatty acid profiles are shown in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1 Composition and proximate analysis of the experimental diets

* Vitamin premix contained (g premix): thiamine hydrochloride, 5 mg; riboflavin, 5 mg; calcium pantothenate,10 mg; nicotic acid, 6·05 mg; l-ascorbyl-2-monophosphate-Mg, 3·95 mg; pyridoxine hydrochloride, 4 mg; folic acid, 1·5 mg; inositol, 200 mg; menadione, 4 mg; α-tocopheryl acetate, 50 mg; retinyl acetate, 60 mg; biotin, 0·6 mg. All ingredients were diluted with α-cellulose to 1 g.

† Mineral premix contained (kg diet): calcium biphosphate, 13·58 g; calcium lactate, 32·7 g; FeSO4.6H2O, 2·97 g; magnesium sulphate, 13·7 g; potassium phosphate dibasic, 23·98 g; sodium biphosphate, 8·72 g; sodium chloride, 4·35 g; AlCl3.6H2O, 0·015 g; KI, 0·015 g; CuCl2, 0·01 g; MnSO4.H2O, 0·08 g; CoCl2.6H2O, 0·1 g; ZnSO4.7H2O, 0·3 g.

Table 2 Fatty acid composition (% of total fatty acids) of the experimental diets

Experimental procedure

The feeding trial was performed in an indoor recirculating aquarium system at the Yangtze River Fisheries Research Institute (Wuhan, Hubei Province, China). GIFT strain fish were obtained from the Guangxi tilapia national breeding farm (Nanning, Guangxi Province, China), and were maintained in a concrete pool (3×3×5 m) at the experimental base. During the acclimatisation period, fish were fed the basal diet to adjust to the experimental diets and environmental conditions for 2 weeks.

During the initial phase, fish were fasted for 24 h and weighed after being anaesthetised with 80 mg/l MS-222. Adult male fish (initial weight: 83·12 (sd 2·84) g) were randomly assigned to eighteen tanks (500 litres) with twenty fish/tank. Three tanks of fish were randomly assigned to each diet. To reduce pellet waste, fish were gradually hand-fed until they appeared satiated by observing their feeding behaviour. The fish were fed three times a day: 08.30, 12.30 and 16.30 hours (natural photoperiod). The feeding trial lasted 68 d. During this period, food consumption and any fish deaths were recorded daily. The water was maintained at 28–34°C, pH of 7·4–7·6, with a dissolved O2 concentration >6 mg/l. During the feeding trial, fish were weighed and counted every 2 weeks after 24 h of fasting for analysis of growth and feeding. All experiments were conducted using a protocol approved by the Yangtze River Fisheries Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Fishery Sciences.

Sample collection

At the end of the experiment, fish were weighed and counted following a 24-h fast. Eight fish were removed from each tank using a dipnet and sedated with 80 mg/l MS-222 and were designated as the sample fish. The body weight of each sample fish was similar to the average fish weight of each tank. Three sample fish from each tank were killed and the bodies, viscera and liver were collected and weighed to determine the viscerosomatic index (VSI) and the hepatosomatic index (HSI). The liver, viscera and dorsal muscle tissues were stored at −80°C until analysis of tissue composition and fatty acid analysis. A further two sample fish from each tank were killed for whole-body composition analyses. The whole body was first cut into small pieces with a knife, and then minced with a meat grinder; the minced meat was mixed thoroughly, and samples of approximately 100 g were taken from each fish and frozen at −80°C. The remaining three sample fish per tank were sedated with 80 mg/l MS-222, disinfected with 75 % alcohol and killed. Approximately 0·2 g of brain, heart, liver, muscle and visceral tissue was placed in 2-ml microcentrifuge tubes, frozen in liquid N2 and stored at −80°C until mRNA expression analyses.

Biochemical analyses

Crude protein, crude fat and ash contents were measured using the Micro-Kjeldahl, Soxhlet and ignition methods, respectively. Moisture content was determined using the freeze-drying method, in which samples were freeze-dried for 48 h in a vacuum freeze dryer (Christ Beta 2–4 LD plus LT; Marin Christ Corporation). Fatty acid content of diets and tissues was determined as previously described by Liu et al.( Reference Liu, Liu and Chen 30 ). Fatty acid methyl esters were separated, and quantified by GC-2010 gas chromatograph (SHIMADZU) with a fused silica capillary column (SP-2560; Supelco; 100 m×0·32 mm i.d., film thickness 0·20 μm) and a flame ionisation detector (FID). The thermal gradient programme was initially 100°C for 3 min, followed by increments of 5°C/min and finally 250°C for 10 min. The injector and FID temperatures were 250°C. PC contents in samples of the diets, muscle and liver were determined at the China National Analytical Center. The quantitative determination of PC in samples was conducted using the HPLC – Refractive Index (RI) method. A Waters Spherisorb S5W column (4·6×250 mm packed with 5-μm silica) and an isocratic mobile phase consisting of n-hexane–2-propanol–water (1:4:1, by vol.) were used. The HPLC conditions were as follows: flow rate 0·8 ml/min, injection aliquot 10 μl, column temperature 35°C and temperature of the RI detector (differential refractive index detector) 35°C. The content of PC in samples was determined by the external standard method, using soyabean PC as the external standard.

The sequences of the primer pairs used for real-time PCR (RT-PCR) analysis of gene expression of secretory phospholipase A2 (sPLA2), cytosolic phospholipase A2 (cPLA2), FAS, LPL, HSL, growth hormone (GH), insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) and β-actin are shown in Table 3. β-actin was selected as the housekeeping gene for the normalisation of gene expression. RT-PCR reactions were conducted as previously described( Reference Tian, Wu and Yang 29 ).

Table 3 Nucleotide sequences of primers and cycling conditions used for PCR amplification

Tm, melting temperature; FAS, fatty acid synthase; LPL, lipoprotein lipase; HSL, hormone-sensitive lipase; GH, growth hormone; IGF-1, insulin-like growth factor-1; sPLA 2 , secretory phospholipase A2; cPLA 2 , cytosolic phospholipase A2.

Statistical analyses

The data were analysed using one-way ANOVA and Duncan’s multiple-range tests using SPSS 17.0 for Windows (SPSS). Data are expressed as means and standard deviations in tables and figures. Differences were considered significant at P<0·05.

Results

Growth performance and physiological parameters

The effects on growth performance and physiological parameters of feeding adult Nile tilapia diets containing increasing amounts of PC are shown in Table 4. Fish fed diets containing 4·0 to 21·3 g/kg of PC showed a higher feed efficiency rate (P<0·05) than those eating the control diet. The feeding rate was not significantly different among diet groups, ranging from 1·75 to 1·81 %. The weight gain and specific growth rate were lower in the G4 group than in the G0.5 group (P<0·05), but no other differences were found in weight gain and specific growth rate between fish fed diets with added PC or the control diet. Fish in group G1 showed the highest VSI and HSI. No fish died during the feeding trial.

Table 4 Growth performance and physiological parameters for Nile tilapia fed diets containing different phosphatidylcholine (PC) levels for 68 d (Mean values and standard deviations; n 3)

a,b,c Mean values in the same row with unlike superscript letters were significantly different (P<0·05).

* Weight gain (WG, %)=100×(final body weight−initial body weight)/initial body weight.

† Specific growth ratio (SGR, %/d)=100×ln(final weight/initial weight)/d.

‡ Feed efficiency rate (FER, %)=100×wet weight gain/dry feed consumed.

§ Feeding rate (FR)=100×dry feed consumed×2/(final body weight+initial body weight)/d.

║ Hepatosomatic index (HSI, %)=100×(hepatosomatic weight/whole body weight).

¶ Viscerosomatic index (VSI, %)=100×(viscera weight/whole body weight).

Whole body and tissue composition

Table 5 shows the effects of varying levels of dietary PC on whole body and tissue composition. As the amount of dietary PC increased, whole body crude fat content decreased from 10·79 to 9·77 % (P<0·05), liver crude fat content decreased from 10·53 to 8·34 % (P<0·05) and visceral crude fat content decreased from 21·95 to 19·26 % (P<0·05). The crude fat content in muscle increased from 1·68 to 2·34 % (P<0·05) as dietary PC levels increased from 1·7 to 11·5 g/kg and then subsequently decreased to 1.67 % when dietary PC increased further from 21·3 to 41 g/kg. Moisture concentrations in liver were significantly higher in the G4 group than in other groups (P<0·05). Moisture concentrations in muscle, viscera and whole body were unchanged with increasing dietary PC levels. The G1 group had the lowest protein content in the whole body. With increasing dietary PC level, crude protein content in muscle in PC-added groups significantly increased compared with fish fed the control diet (P<0·05). Liver protein content was not affected by dietary PC level. Increasing dietary PC levels resulted in crude protein content in viscera decreasing from 8·71 to 7·73 % (P<0·05). No significant differences were found in the ash content of whole body or muscle.

Table 5 Proximate tissues and whole-body compositions of Nile tilapia fed diets containing different levels of phosphatidylcholine (PC) for 68 d (%) (wet mass) (Mean values and standard deviations; n 3)

a,b,c Mean values in the same row with unlike superscript letters were significantly different (P<0·05).

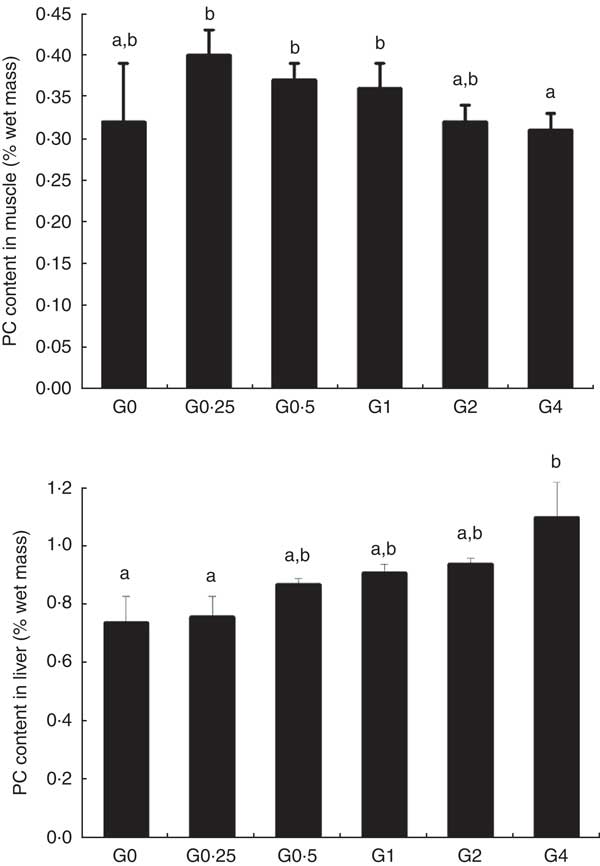

Phosphatidylcholine content of muscle and liver

Fig. 1 shows the PC content of muscle and liver in fish fed different dietary levels of PC. The PC content in the liver increased with greater amounts of PC in the diet, becoming significantly higher in the G4 group than in the control group (P<0·05). As dietary PC levels increased, the muscle content of PC in fish containing diets with added PC was not significantly different compared with that of the control group.

Fig. 1 Phosphatidylcholine (PC) content of muscle and liver in adult Nile tilapia fed diets containing different PC levels for 68 d. Values are means, and standard deviations represented by vertical bars. a,b Mean values with unlike letters were significantly different using Duncan’s multiple-range test (P<0·05).

Muscle and liver tissue fatty acid profile

In muscle, there were differences in total SFA, MUFA and PUFA in response to dietary PC level (Table 6). SFA and MUFA increased, whereas PUFA decreased with increasing dietary PC levels. In particular, C16 : 0 and C18 : 1 increased with increasing dietary PC levels, whereas linoleic acid (C18 : 2n-6, LA) was significantly decreased in muscle from the higher PC groups, with the G4 group containing 57 % less LA than the control group (P<0·05).

Table 6 Fatty acid composition (% of total fatty acids) of the muscle of Nile tilapia fed diets containing different phosphatidylcholine (PC) levels for 68 d (Mean values and standard deviations; n 3)

a,b,c,d,e Mean values in the same row with unlike superscript letters were significantly different (P<0·05).

SFA in the liver decreased from 29·27 to 27·88 % (P<0·05) as dietary PC levels increased from 1·7 to 6·5 g/kg, and then increased to 31·53 % as dietary PC increased to 41 g/kg. No significant differences were obtained in MUFA and PUFA content in fish fed additional PC compared with the control group (Table 7).

Table 7 Fatty acid composition (% of total fatty acids) of the liver of Nile tilapia fed diets containing different phosphatidylcholine (PC) levels for 68 d (%) (Mean values and standard deviations; n 3)

a,b,c,d Mean values in the same row with unlike superscript letters were significantly different (P<0·05).

Relative mRNA expression levels

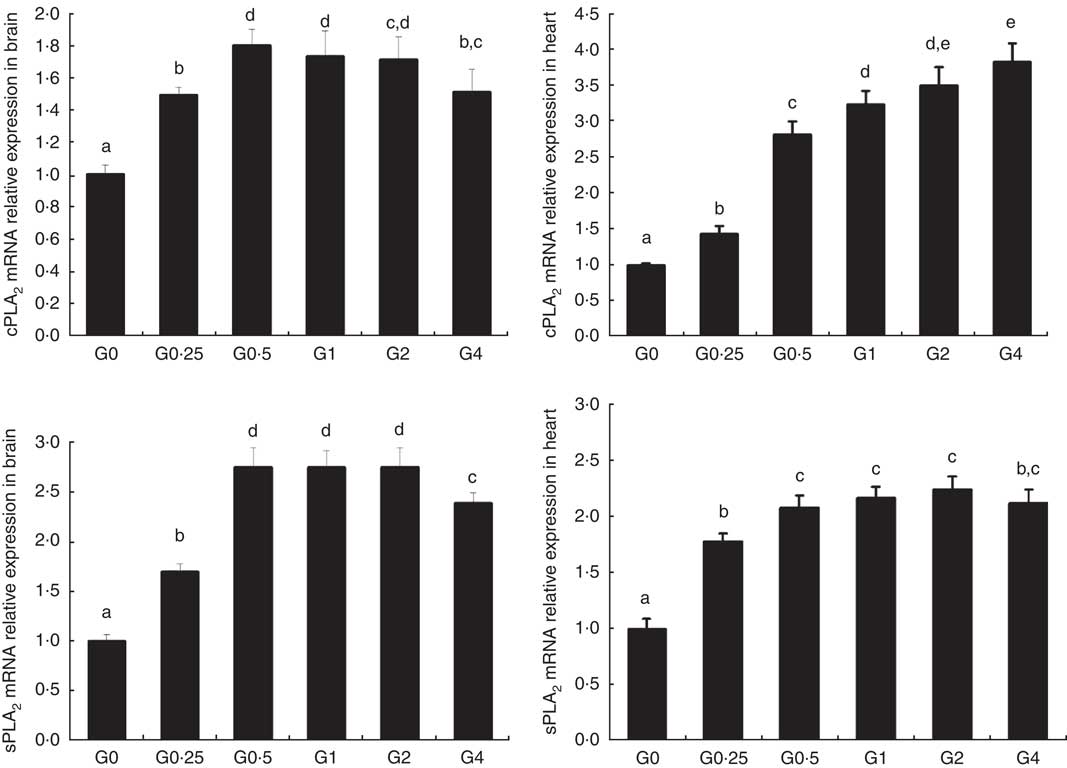

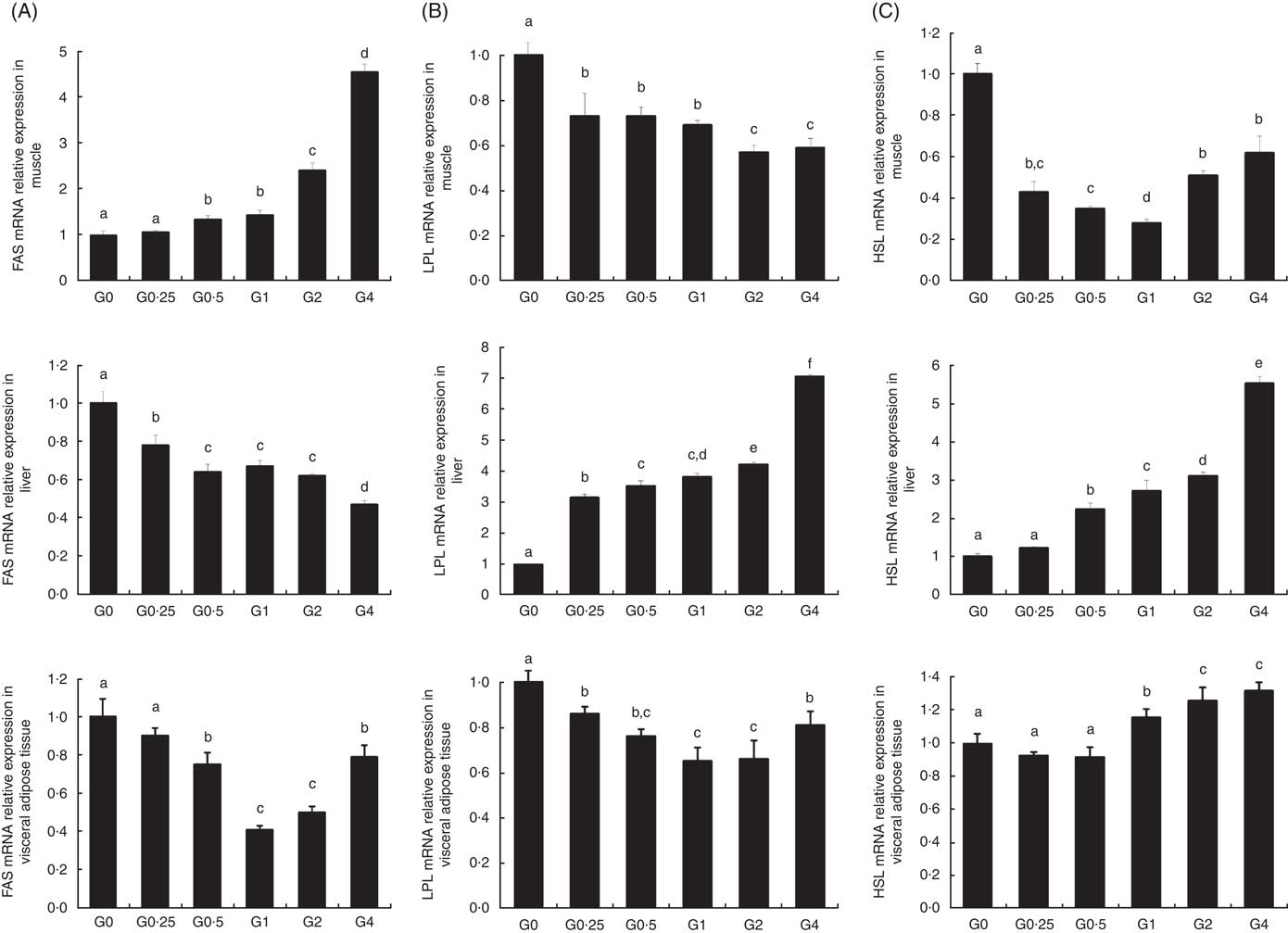

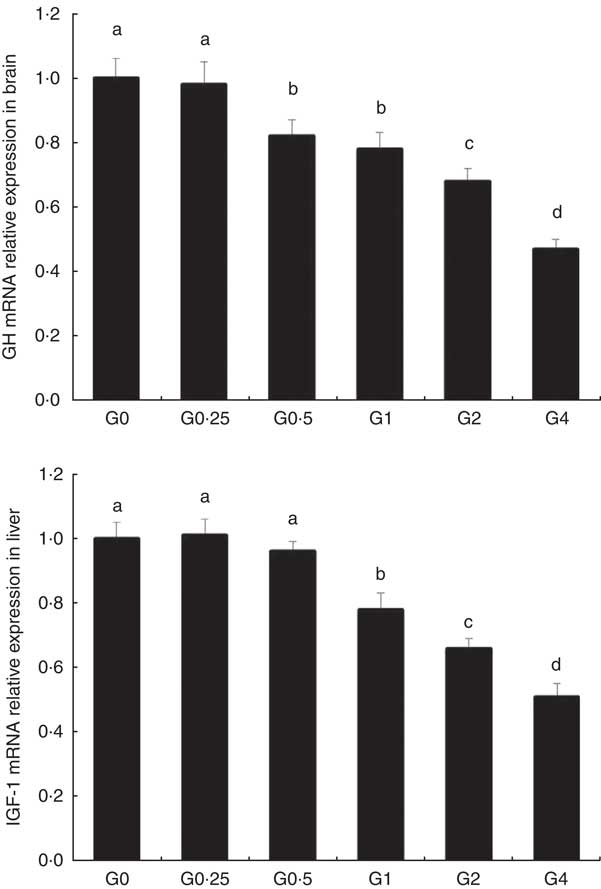

The expression of cPLA 2 and sPLA 2 mRNA was up-regulated in brain and heart with increased dietary PC levels compared with the control diet group without added PC (Fig. 2). Increased dietary PC reduced FAS mRNA expression in the liver and FAS mRNA expression in visceral tissue was reduced from the G0.5 to the G4 group. In contrast, FAS mRNA expression increased in the muscle from the G0.5 to the G4 group (Fig. 3(A)). In the PC-fed groups, there was a significant up-regulation in LPL mRNA expression in liver and visceral tissue (P<0·05), and down-regulation in muscle (P<0·05) (Fig. 3(B)). Compared with the control group, the PC-fed groups showed higher HSL mRNA levels in the liver (from the G0.5 to the G4 group) and visceral tissue (from the G1 to the G4 group). However, HSL mRNA levels in muscle were significantly lower in the PC-fed fish than in the control group (P<0·05) (Fig. 3(C)). GH mRNA in brain was significantly down-regulated with PC levels of 6·5 g/kg or above (P<0·05), whereas IGF-1 mRNA in liver was significantly down-regulated at a PC level above 6·5 g/kg (P<0·05) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 2 The effects of dietary phosphatidylcholine (PC) levels on the mRNA expression levels of phospholipase A2 (PLA 2 ) in brain and heart for adult Nile tilapia. Values are means, and standard deviations represented by vertical bars. cPLA2: cytosolic phospholipase A2; sPLA2, secretory phospholipase A2. a,b,c,d,e Mean values with unlike letters were significantly different using Duncan’s multiple-range test (P<0·05).

Fig. 3 The effects of dietary phosphatidylcholine (PC) levels on the mRNA expression levels of genes involved in lipid metabolism in adult Nile tilapia for 68 d. (A) Fatty acid synthase (FAS) mRNA relative expression in liver, muscle and visceral adipose tissues. (B) Lipoprotein lipase (LPL) mRNA expression in liver, muscle and visceral adipose tissues. (C) Hormone-sensitive lipase (HSL) mRNA expression in liver, muscle and visceral adipose tissues. Values are means, and standard deviations represented by vertical bars. a,b,c,d,e,f Mean values with unlike letters were significantly different using Duncan’s multiple-range test (P<0·05).

Fig. 4 The effects of dietary phosphatidylcholine (PC) levels on the mRNA expression levels of genes involved in growth hormone (GH) and insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) in adult Nile tilapia for 68 d. Values are means, and standard deviations represented by vertical bars. a,b,c,d Mean values with unlike letters were significantly different using Duncan’s multiple-range test (P<0·05).

Discussion

The weight gain and specific growth rate for adult Nile tilapia remained largely unchanged by the addition of PC to the diet. This suggests that adult tilapia do not require additional PC for normal growth performance, which is consistent with previous results in juvenile large yellow croaker( Reference Feng, Cai and Zuo 31 ), Atlantic salmon( Reference Poston 10 ) and white sturgeon( Reference Hung, Berge and Storebakken 4 ). We measured the mRNA expression of GH in the brain and expression of IGF-1 in liver, as the GH/IGF axis senses nutritional status and regulates body growth( Reference Reindl and Sheridan 32 ), and GH and IGF-1 mRNA are abundantly expressed in brain( Reference Ma, Zhang and Huang 33 ) and liver( Reference Schmid, Lutz and Kloas 34 ) in tilapia. The expression of GH mRNA in the brain and IGF-1 mRNA in liver were down-regulated with higher levels of PC in the diet. This indicates that high levels of dietary PC reduce GH and IGF expression, potentially inhibiting the secretion of GH, and resulting in relatively slow growth performance.

As dietary PC levels increased, the crude fat content decreased in the whole body, liver and viscera, whereas PC content increased, indicating that dietary PC can reduce lipid accumulation in adult tilapia by regulating lipid metabolism. This is in agreement with previous results in large yellow croaker( Reference Feng, Cai and Zuo 31 , Reference Zhao, Ai and Mai 35 ) and Dojo loach( Reference Gao, Koshio and Wang 36 ), which suggest that PL may prevent and alleviate signs of liver disease in fish. We hypothesised that for fish fed diets with PC, the expression of genes related to lipogenesis would be lower, and the expression of genes related to lipolysis would be higher, ultimately resulting in lower lipid content. We investigated the effect of increased dietary PC on the expression of lipogenesis-related genes. PC increased the expression of LPL and HSL, enzymes involved in lipolysis, and decreased the expression of FAS, a lipogenic enzyme, in the liver. The level of LPL expression in a given tissue is the rate-limiting process for the uptake of TAG-derived FA( Reference Merkel, Weinstock and Chajek-Shaul 37 ). LPL activity has previously been reported to be higher in the liver of cobia supplemented with PL( Reference Niu, Liu and Tian 38 ), and expression of LPL mRNA in the whole larval body significantly increased and expression of FAS mRNA decreased with the increasing levels of dietary PL in large yellow croaker larvae( Reference Cai, Feng and Xiang 39 ). The expression of hepatic FAS mRNA was also decreased by diets with soyabean PL or EPA (EPA)-enriched PL in mice( Reference Liu, Xue and Liu 12 ). Our results confirm these previous findings, suggesting that PC increases the capacity to mobilise fat stores via regulation of competing lipolysis and lipogenesis enzymes, and these are consistent with the reduced lipid accumulation in the livers of Nile tilapia supplemented with PC. Unexpectedly, the higher dietary PC reduced expression of LPL and HSL in muscle, suggesting increased lipid deposition in muscle.

The fatty acid profiles in muscle and liver were affected by increasing PC levels, with SFA and MUFA increased and PUFA decreased in muscle. This may be related to variations in the fatty acid composition of the diets. Similarly, in Dojo loach, concentrations of total n-3 fatty acids in the whole body significantly decreased with incremental dietary PL levels( Reference Gao, Koshio and Wang 36 ). In contrast, rainbow trout fry fed egg lecithin containing high levels of EPA and DHA showed higher amounts of PUFA than soyabean lecithin and soyabean oil control groups( Reference Azarm, Abedian-Kenari and Hedayati 40 ). Fatty acids are released from membrane PL by the action of PLA2, of which two main types are present. cPLA2 are soluble in the cytosol and must first interact with or penetrate the organised lipid interface. sPLA2 are linked to the cell membrane and, as a consequence, are unlikely to be structured such that penetration of the lipid interface is physiologically relevant( Reference Boulanger, Labelle and Khiat 23 ); sPLA2 is highly expressed in the pancreas, brain, heart and liver tissues( Reference Song, Chang and Bean 41 ). Nalefski et al. ( Reference Nalefski, Sultzman and Martin 42 ) first cloned the complementary DNA sequence of cPLA2 from fish, and the cPLA2 protein from the zebrafish shares a low (65 %) similarity with that from humans. The activity of sPLA2 in Atlantic cod was higher in liver, brain, kidney and gills than in muscle, potentially because of the regulatory roles that PLA2 are thought to play in the brain and heart( Reference Sæle, Nordgreen and Olsvik 43 ). The expression of sPLA 2 mRNA in the whole body was positively correlated with dietary PL content in sea bass larvae( Reference Cahu, Zambonino Infante and Barbosa 44 ), and sPLA2 activity in red drum Sciaenops ocellatus larvae also increased with increasing dietary PL( Reference Buchet, Zambonino Infante and Cahu 45 ). In this study, we noted an up-regulation of cPLA 2 and sPLA 2 mRNA expression with increasing dietary PC levels in the brain and heart, suggesting that PLA2 are potentially regulated via a positive feedback mechanism regulating the use of dietary PL in some fish.

Conclusions

Moderate supplementation of the diet with PC was beneficial for improving feed efficiency and reducing liver fat for adult Nile tilapia, with no effect on weight gain. Excessive dietary PC may alter the expression of LPL, HSL and FAS mRNA in liver. Dietary supplementation with PC represents a potential new dietary approach to reduce feed requirements and improve the health of adult Nile tilapia in commercial aquaculture.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the China Agriculture Research System (grant no. CARS-46) and the Central Public-interest Scientific Institution Basal Research Fund (CAFS) (grant no. 2017JBF0204). These funders had no role in the design and analysis of the study, or in the writing of this article.

H. W. and J. T. designed the research; J. T., L.-J. Y., X. L., W. L., F. W. and C.-G. Y. conducted the experiments and analysed the data; J. T. and M. J. wrote the paper. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.