1 Overview

Gold mines in Kyrgyzstan that are owned and operated by Chinese investors have experienced several problems in recent years, chief among them being labor disputes with local workers. These disputes mark a pattern of dysfunction in one of Kyrgyzstan’s most critical industries. They are further significant for a number of additional reasons. First, they shine a light on the realities of doing business in a controversial sector in a developing country. Second, they demonstrate labor issues from the host state side, specifically the difficulties of finding decent work for Kyrgyz laborers, and how certain industries may thereby engage in predatory practices. Third, they show the ineffectiveness of government intervention. This case study will expose readers to the causes of the problem and encourage them to critically assess the responses of various stakeholders to the disputes. It also will assess the extent to which different fields and concepts of governance are either well-established in corporate practice and across industries, a function of supranational governance, or are Chinese-inspired innovations apply to Kyrgyzstan’s gold mining sector. These range from corporate social responsibility (CSR) and environmental, social and governance (ESG) to the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the “Green Silk Road.”

2 Introduction

2.1 History and Significance

Following independence from the Soviet Union in 1991, Kyrgyzstan’s gold mines were initially seen as an opportunity for foreign investors and local actors to work together to develop the country. Since then, however, the gold mining industry has struggled to fulfill its potential and, in general, the view of foreign investors has soured. This is best illustrated in the well-documented case of the Kumtor gold mine, which was once owned and operated by Canadian firms. Located in the east of the country, Kumtor is Kyrgyzstan’s largest mine. It accounted for 68% of national gold output in 2022 and is arguably the country’s single most significant productive asset.Footnote 1 Although a report on Kumtor’s contribution to economic growth is no longer available on the mine operator’s website, it was reported by commentaries in 2021 and 2022 as accounting for 12% of Kyrgyz GDP and 23% of Kyrgyz industrial output.Footnote 2 However, since the start of its operations in 1997, the Kumtor mine has also become the object of scrutiny and criticism because of its river pollution,Footnote 3 damage to glaciers,Footnote 4 and tax irregularities,Footnote 5 as well as corruption scandals that have implicated former Kyrgyz presidents.Footnote 6 In 2022, the Kyrgyz authorities unilaterally seized control of the Kumtor mine.Footnote 7 This then prompted bankruptcy litigation and international arbitration in the United States, Canada, and Sweden, which culminated in an out-of-court settlement marking the end of Canadian control.Footnote 8 Overall, the scandals have tarnished the image of foreign direct investment in Kyrgyzstan, which is now closely associated with corruption, environmental damage, and socioeconomic inequality.Footnote 9 However, such scandals have not been exclusive to Kumtor and have grown to pervade a swathe of Kyrgyz gold mines – irrespective of the nationality of the foreign investor. A number of such mines are now operated and owned by Chinese firms. In the region covered by this case study, Jalal-Abad, eighteen out of twenty-eight gold mines are owned by either a Chinese individual or an organization.Footnote 10

This case study focuses on labor conflicts between Chinese investors and local Kyrgyz workers in the Ishtamberdy and Kichi-Chaarat gold mines. These are both located in Jalal-Abad, which is a mountainous borderland in the west of Kyrgyzstan. Compared to the Kumtor mine, these mines are smaller in scale and output and, therefore, do not have the same economic significance as Kumtor. But focusing on labor disputes in the context of such mines is important as doing so provides a bottom-up view of the potentially adverse social and environmental impact of Chinese investments in the extractives sector. To date, although such investments have not led to the same public fallout as the Canadian-owned Kumtor mine, they are becoming the subject of scrutiny for two reasons. First, CSR and ESG initiatives and responses related to the UN SDGs are being increasingly applied to and adopted by the extractives industry as a whole. Second, this topic provides a lens through which to consider the role of Chinese businesses as a “responsible player” on the global stage and their mandate to shape their investment activities as a means of promulgating a “Green Silk Road.”Footnote 11

2.2 Case Study Roadmap

This case study focuses on the “lifespan” of a typical labor dispute between local Kyrgyz workers and Chinese companies, using the Ishtamberdy and Kichi-Chaarat gold mines as examples. Attention is paid to the socioeconomic and legal origins of such a dispute, especially to factors arising prior to and during employment. In addition, it addresses how local and national governments as well as Chinese companies respond to labor strikes and the chosen methods of dispute resolution (e.g., formal litigation or informal settlement). In particular, the case study discusses the Chinese company’s mass dismissal of 400 Kyrgyz workers in order to avoid bankruptcy at the Ishtamberdy mine. Laborers there had engaged in long-term disruptive strikes against substandard working conditions and the nontransparent hiring of workers through intermediary organizations. In addition, the case study will also explore the environmental criticisms from local stakeholders that have heightened concerns about worker protests at the Kichi-Chaarat mine, leading management to increase security in and around the facility. Finally, the case study will explain the relevance to the disputes of such factors as corporate culture, labor division, and the promotion and education opportunities for Kyrgyz workers. Hence, this case study will reveal the complexity of local and national conditions encountered by Chinese mine managers and owners in Kyrgyzstan. It will show not just how Chinese investors have responded to these local conditions but also how stakeholders on the Kyrgyz side have reacted, demonstrating how multiple parties contribute to outcomes.

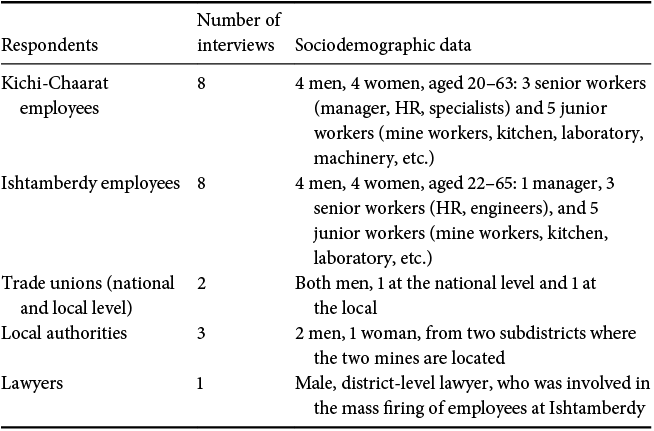

This case study is primarily based on twenty-two in-depth interviews held in November and December 2022 with employees and managers at the Ishtamberdy and Kichi-Chaarat gold mines, as well as with local authorities and representatives of mining trade unions (see Table 4.2.1). The employees of the gold mines were sampled according to age, gender, seniority, management responsibility, and current job status (i.e., whether they are still employed or whether their employment has terminated). Given the general absence of any transparent reporting culture and the sensitivity of critiquing the mining sector, these in-depth interviews were crucial in helping to understand the issue. Some respondents were reluctant to answer and the percentage of refusals to participate in the study was high.

Table 4.2.1 Information on interview respondents

| Respondents | Number of interviews | Sociodemographic data |

|---|---|---|

| Kichi-Chaarat employees | 8 | 4 men, 4 women, aged 20–63: 3 senior workers (manager, HR, specialists) and 5 junior workers (mine workers, kitchen, laboratory, machinery, etc.) |

| Ishtamberdy employees | 8 | 4 men, 4 women, aged 22–65: 1 manager, 3 senior workers (HR, engineers), and 5 junior workers (mine workers, kitchen, laboratory, etc.) |

| Trade unions (national and local level) | 2 | Both men, 1 at the national level and 1 at the local |

| Local authorities | 3 | 2 men, 1 woman, from two subdistricts where the two mines are located |

| Lawyers | 1 | Male, district-level lawyer, who was involved in the mass firing of employees at Ishtamberdy |

3 The Case

3.1 Background

Kyrgyzstan’s economy is dependent on the gold sector, which accounts for 10% of GDP and 39% of exports. In 2021, Kyrgyzstan exported US$908 million in gold, and although this meant that Kyrgyzstan was only the 52nd largest exporter of gold in the world, gold was the primary export from the country.Footnote 12 Against this backdrop, foreign investment in gold mining areas has become a battleground for foreign investors, Kyrgyz authorities, the opposition, and local communities. Yet, because of its importance, the mining sector is identified as one of the priority sectors for the economy in strategic government papers concerning national development programs. These include the “National Development Program of the Kyrgyz Republic,”Footnote 13 which is in effect until 2026, and the “Concept of Green Economy in the Kyrgyz Republic.”Footnote 14

The employment structure in Kyrgyzstan mainly relies on agriculture and farming (18.3%), wholesale and retail trade (15.3%), construction (12.4%), and public services (health, education, etc.). Mining and quarrying employ only 0.7% of the workforce, with 17,900 people working in the industry. Yet this number has doubled since 2016. This increase can be explained by the Kyrgyz president Almazbek Atambaev’s active cooperation with China and the issuing of mining licenses to smaller deposits since the start of his term in 2011.

A number of gold deposits have been discovered in the Middle Tian Shan mountains in Jalal-Abad. This region is southwest of the capital, Bishkek, and is a rural, mountainous area that has been traditionally used as summer pastures for local livestock keepers.Footnote 15 Jalal-Abad incorporates both the Ishtamberdy and Kichi-Chaarat mines, which are described in turn and in fuller detail below.

First, the Ishtamberdy mine was opened in 2011 as Kyrgyzstan’s second foreign-owned mine. However, its operations since then have been intermittent due to license suspensions imposed by the Kyrgyz government in 2013,Footnote 16 2016,Footnote 17 2018,Footnote 18 and 2023.Footnote 19 Such setbacks have nevertheless not yet resulted in the abandonment of the project, primarily because of the commercial opportunities it presents: Exploration studies indicate that the site contains 140 metric tons of gold.Footnote 20 This assessment places the Ishtamberdy mine among the larger of Jalal-Abad mines, whose gold deposits range from 34 tons (in Bozymchak) to 170 tons (in Chaarat). However, when compared to the Kumtor mine in the east, Ishtamberdy’s deposit is considered relatively small,Footnote 21 containing approximately a quarter of Kumtor’s 538-ton deposit.

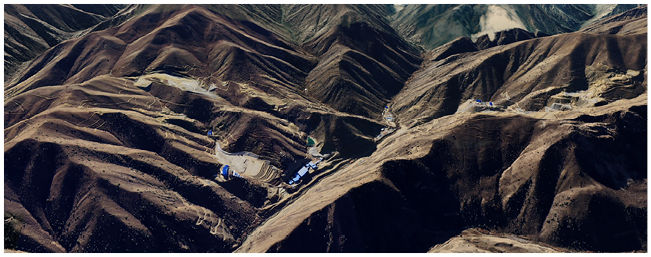

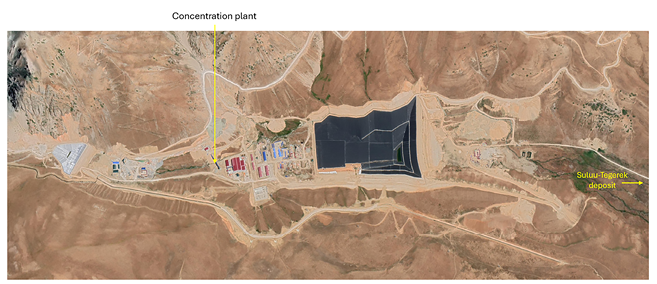

In terms of its operating capability, as Figures 4.2.1 and 4.2.2 show, the Ishtamberdy mine comprises surface mining works and includes a processing facility;Footnote 22 and the stated aim was to mine 300,000 tons of ore per annum and, from that ore, to produce 2 tons of powdered gold concentrate per annum.Footnote 23 However, it is unclear whether this aim has ever been realized because in 2016, when the mine was expected to start operating in full capacity, Ishtamberdy’s chief engineer announced that only 780 kg of gold concentrate would be produced.Footnote 24

Figure 4.2.1 Tilted view of Ishtamberdy mine

Figure 4.2.2 Aerial view of Ishtamberdy mine

In terms of the corporate structure of the Ishtamberdy mine project, the mine asset is owned and operated by Full Gold Mining Limited Liability Company (“Full Gold Mining”). It is a gold mining company and, according to Sayari, has one director and three shareholders. One shareholder is Lingbao Gold Company Limited (靈寶黃金股份有限公司),Footnote 25 a Chinese state-owned and Hong Kong-listed corporation that specializes in “mining, processing, smelting and sales of gold and other metallic products.”Footnote 26 A second shareholder is China Road and Bridge Corporation (中国路桥工程有限责任公司).Footnote 27 This may explain why, despite a primary focus on mining, Full Gold Mining appears to have diverse business interests that also include, for example, road building, which have been used to secure the rights to the Ishtamberdy project.

Although detailed corporate information relating to Full Gold Mining and the Ishtamberdy mine is generally inaccessible, online sources indicate that the Chinese company came into control of and assumed the authority to develop the mine in three complementary ways. First, on 16 January 2008, Full Gold Mining secured a twenty-year license from the Kyrgyz government, a necessary prerequisite for any mine development.Footnote 28 Second, Full Gold Mining’s acquisition was carried out through a multiparty Cooperation Agreement signed by Chinese and Kyrgyz parties from both the government and the private sector. On the Chinese side, signatories included China Development Bank, China Road and Bridge Corporation, and Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region Lin Xi Investment Company, who all appear to have either financed the Ishtamberdy mine or supplied it with goods and services necessary for the mine’s operation.

On the Kyrgyz side, signatories included the Kyrgyz Ministry of Transport and Communications and the Kyrgyz State Agency for Geology and Mineral Resources, who played a role in regulating, licensing, and approving the Ishtamberdy project. Third, Full Gold Mining and the Kyrgyz government reached an agreement on “Resources in Exchange for Investment.”Footnote 29 Under its terms, Full Gold Mining would secure the rights to develop Ishtamberdy on the condition that it improved the local road infrastructure. Consequently, prior to securing Kyrgyz licenses, Full Gold Mining served as the “entity responsible for project implementation” in a project to restore 50 km of the Osh-Sarytash-Irkeshtam Road that was financed by the China Development Bank via a US$38.57 million loan.Footnote 30 A peculiar feature of this transaction is that, although the road project was not connected geographically to the Ishtamberdy mine, the China Development Bank loan was to be repaid out of revenues generated by the mine and not the road project.Footnote 31 Separately, and following an outcry from villagers, Full Gold Mining also paved the road linking local settlements surrounding the Ishtamberdy mine.Footnote 32 These developments suggest a high degree of willingness among prospective Chinese investors (as well as third parties who play a secondary and supportive role, such as banks) to do whatever is necessary to secure the required licenses and agreements with the host country irrespective of the Chinese investor’s core business operation.

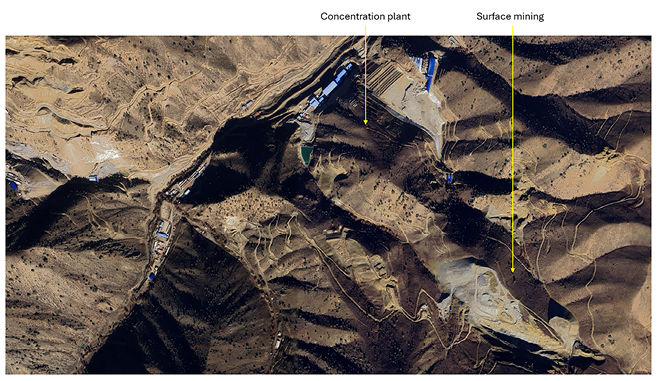

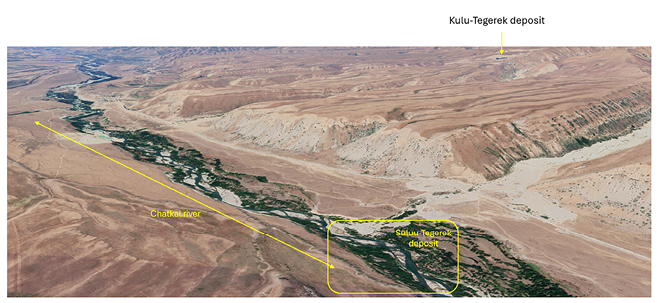

The second gold mine that this case study explores is the Kichi-Chaarat mine, which lies approximately 70 km to the northeast of the Ishtamberdy mine, separated by the Pikgora mountain. The Kichi-Chaarat mine opened in 2019;Footnote 33 and, like Ishtamberdy, operations at the Kichi-Chaarat mine have periodically stalled due to license suspensions. One such suspension occurred in 2022 and applied to Kichi-Chaarat’s Suluu-Tegerek deposit.Footnote 34 However, unlike Ishtamberdy, the Kichi-Chaarat mine falls into two parts (as it has two deposits) and operates different excavation methods.Footnote 35 The mine’s Kulu-Tegerek deposit is located up on a mountainside and incorporates a US$220 million underground mine and concentration plant for converting gold, silver, and copper ore into powdered concentrates (Figures 4.2.3 and 4.2.4).Footnote 36 According to AidData, “Upon completion, the mine was expected to have an annual processing capacity of about 1.8 million tons, including an annual output of 11,000 tons of copper, 600 kg of gold and 4.6 tons of silver. The annual sales from the mine were expected to be $100 million.”Footnote 37 Meanwhile, down the mountainside in the Chatkal valley’s riverbed lies the Suluu-Tegerek deposit, which incorporates a placer mine.Footnote 38 Such mines remove gold deposits from sediment in water, but information on its productive capacity (either projected or actual) is unavailable.

Figure 4.2.3 Aerial view of Kulu-Tegerek deposit at Kichi-Chaarat mine

Figure 4.2.4 Tilted view of Suluu-Tegerek deposit at the Kichi-Chaarat mine

The Kichi-Chaarat mine is owned and operated by Kichi-Chaarat Closed Joint Stock Company (“Kichi-Chaarat”), which is a special purpose organization established by Chinese equity investors to oversee the project. As with Full Gold Mining, little corporate information relating to Kichi-Chaarat is available. However, the available information indicates that it was owned by a succession of Canadian and Chinese companies. Specifically, a press release in 2004 indicates that Kichi-Chaarat was acquired by Eurasian Minerals, Inc., a Canadian firm, through a subsidiary called Altyn Minerals LLC.Footnote 39 Four years later, a United States Securities and Exchange Commission filing suggests that ownership had changed hands and that, in 2008, Kichi-Chaarat was owned by China Shen Zhou Mining & Resources, Inc. (a publicly listed firm whose shares were traded on what was then known as the American Stock Exchange) through a subsidiary called American Federal Mining Group.Footnote 40 Following this, online searches indicate that Kichi-Chaarat in 2013 was 84% owned by the China National Gold Group Corporation and 16% owned by China CAMC Engineering Hong Kong Company Limited. Furthermore, similarly to Full Gold Mining, Kichi-Chaarat also received support from other Chinese economic actors – in this case, loan financing from both the China Export-Import Bank in 2017 and Skyland (a subsidiary of China Gold International Resources Group Corporation Limited) in 2016.Footnote 41 A more recent example of this is illustrated by a company press release by the Shanghai subsidiary of China National Gold, which celebrated its work to quickly provide supplies to Kuru-Tegerek by utilizing a streamlined customs declaration procedure and a combination of trucks and trains:

On March 3, ten 40-foot containers loaded with RMB 4 million worth of mining machinery and equipment as well as production materials were released at Kashgar and Irkeshtam customs upon sealing inspection and transported to Kuru-Tegerek copper and gold mine in Kyrgyzstan through the Irkeshtam port. This indicated that the speed of the “China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan” highway and railway intermodal international freight train has been fully accelerated, in which China Gold Trading (Shanghai) was a major participator.Footnote 42

Overall, when considering the role of Chinese investment in the Kyrgyz gold mining sector, it is worth noting that, first, Chinese investors will seek to work in concert with Kyrgyz and Chinese stakeholders from both the private and public sectors not only to agree to the terms of their investments but also to procure the necessary financing and project supplies. Second, Chinese investors will exercise flexibility to fulfill the needs of Kyrgyz stakeholders, even if doing so requires providing business solutions or negotiation concessions that may be novel or unfamiliar. Third, ownership of Kyrgyz mines seems to be particularly dynamic with owners and investors from various nationalities involved at different stages.

3.2 Causes of Tension

Gold mines have occupied a prominent position in Kyrgyzstan’s national debates and political life. Over the last twenty years, local protests against foreign-owned mines have become more frequent in line with reducing employment opportunities, rising resource nationalism, and dissatisfaction among the local population who feel deprived from the income generated by the mines.Footnote 43 Political unrest has provided an opportunity for local community members to voice their demands to both the companies operating gold mines and state authorities. One example is the unrest that erupted in October 2020 led by local community members against gold mining companies, including those at the Chinese-operated mines at Kichi-Chaarat and Ishtamberdy. The protests caused production to halt for several days as the mines were seized by the local population. The local population’s grievances against the Chinese-operated mines were fueled by “perceived corruption, the lack of transparency, and discrimination against hiring local residents as well as environmental degradation.”Footnote 44

3.3 Opaque Hiring Practices

In late 2022, the Ishtamberdy mine had 585 employees and Kichi-Chaarat employed 129. Typically, Kyrgyz workers occupy various positions, from engineers, geologists and professional positions to regular miners, drivers, repair men, and so on. Women mainly work in the laboratories, kitchens, cleaning departments, and accounting and finance departments. Although our interviews have been unable to ascertain whether these staff numbers comply with Kyrgyz laws decreeing that the foreign labor force in a gold mine may not exceed 10%, recent news reports indicate that Ishtamberdy is compliant: Full Gold Mining, speaking about the Ishtamberdy mine, reported that 91% of workers were local Kyrgyz.Footnote 45

However, in general, Kyrgyz job applicants find it difficult to receive an employment offer from a mining company in Kyrgyzstan. Mining is a well-paid industry so finding positions is intensely competitive. Applicants seeking an edge have paid significant bribes, others have chased job opportunities for years. Seeking employment at Chinese-owned mines is particularly difficult; other foreign companies (i.e., Canadian, British, Turkish, and Kazakh) tend to have a greater degree of accessibility and transparency. They have official websites or social media pages where they announce vacancies. Although the likelihood of Kyrgyz applicants satisfying all the job requirements and being accepted is very low, potential employees at least are informed as to the eligibility criteria and requirements for the position.

3.4 The Human Resources Department as Gatekeeper

Now and then, the Kyrgyz employment websites announce vacancies at the Ishtamberdy and Kichi-Chaarat mines, but most are for positions such as senior specialists or within the mine company’s Human Resources department. These departments consist of Kyrgyz employees and play a major role in shaping the employment policy of the Chinese companies. For example, they can shape Chinese companies’ current practice to allocate a quota for its local hires to local authorities, who then try to send their own associates, including relatives or family members (Chinese companies are not alone in adopting this practice). In some cases, positions are given to vulnerable families who have a low income or more children to co-opt those families who might otherwise have a grievance.

As characterized by a number of interview respondents, the Human Resources departments have over time built up power akin to the “mafia” (мафиянын уюгу) by hiring the “convenient” (кытайдын сөзүн сүйлөгөн) workers and firing the “inconvenient,” ones, that is, “the ones who speak justice, demand better meals, compensation for night shifts and raise other problems” (акыйкатты сүйлөгөн, тамак-ашты жакшыртуу, түнкү сменага төлөш боюнча жана башка көйгөйдү айткан). As a result, the “convenient” laborers have formed an alliance of like minds and fully obey the instructions of Chinese managers.

The Chinese managers themselves don’t participate in the hiring process as this is delegated to local subcontracting companies or locally hired human resources professionals. Due to these informal hiring practices, the process is seen as nontransparent by the local communities. For example, if an agitator is known for initiating demonstrations concerning environmental or other social issues in the villages near the mine, they have a better chance of being accepted for a job as a “silence reward,” meaning that they are hired in exchange for their acquiescence. One interviewee recalled: “[Full Gold Mining Company] told me clearly that in exchange for not being an activist and for not mobilizing people to participate in demonstrations against the mine, I would be offered a job (ачык эле айткан, сиз закондошпойсуз, элди үгүттөбөйсүз, ошондо алабыз деген).” Not only does this practice raise ethical questions; it also may risk alienating applicants who have not caused conflict, which, in turn, may precipitate further grievances later on.

3.5 The Utility of Personal Relationships

The easiest and most effective way of being hired in the mining industry is through Kyrgyz acquaintances who already hold senior positions particularly in the Human Resources departments. Alternately, would-be employees need to have influential contacts with Kyrgyz authorities (e.g., such as law enforcement agencies). Of the twenty-two people interviewed, thirteen were hired because they knew someone influential.

Utilizing ties based on a combination of acquaintances, relatives, village neighbors, patrilineal ties, and clan members (тааныш-билиш) is a similar route to employment. For instance, if the senior HR person (Kyrgyz) is from one clan or certain village, most of the employees will be from the same clan or village. Because of the strong affiliation to clans, it is not uncommon for employees from different clans to develop confrontational relationships, which affects operations.

In general, people living close to the mines have a better chance of being accepted, as they are most likely to be affected by the environmental impact of mining activities – such as shoddy maintenance at the Ishtamberdy mine causing the effluent to enter the river, which serves as a water source for nearby villages.Footnote 46 People from the affected village would be prioritized for employment. Although regulations on the procedure for licensing subsoil use do not mandate hiring employees from the nearby villages,Footnote 47 it is the company’s policy to prioritize hiring local people as “compensation.”

3.6 Difficulties with Employment Contracts

Mining is one of the sectors that has a low percentage of informal employment in Kyrgyzstan, meaning that almost all workers have a contract. However, at the beginning of the projects, while the Ishtamberdy and Kichi-Chaarat mines were being established, there was a window of time during which many workers may not have had formal written contracts. The main issue with labor contracts is their term and how they are used to remove agitators. According to the Labor Code of Kyrgyzstan, contracts are concluded for a specified period not exceeding five years or for an indefinite term if the position is permanent. If the job is temporary in nature, contracts can run for a fixed term.Footnote 48 This mismatch (permanent or temporary) is used by many employers, not only by mining companies, across the sectors. Mining companies tend to offer fixed-term contracts for six months or one year, based on their view that the job is temporary. Interviews revealed that these fixed-term contracts have caused labor violations.

For instance, in Ishtamberdy mine, a one-year contract can be used to remove “inconvenient” workers who openly criticized labor conditions and demand more decent working conditions. Hence, workers could be fired without notice, including without sick leave and mandated holiday pay. Employment contracts have also been terminated for other reasons: After the protests in October 2020, nearly forty people (all men aged fifty-five and higher) were fired in a clear example of age discrimination. Kyrgyz law states that the retirement age for men is sixty-three,Footnote 49 but it includes a caveat stating that men working in mining can retire early if they have twenty-five years’ work experience.Footnote 50 Most of the men fired did not have twenty-five years’ experience and on this basis the mass termination of their contracts did not fulfill the caveat.

3.7 Insufficient Equipment and Unsafe Conditions

The interviews indicated that safety measures adopted by Chinese companies are relatively poor compared to other mines operated by other nationalities. The main reasons are the lack of financing for security measures (e.g., no first aid systems in place) and the incompetence of the responsible employees. The issue of health and safety in the Ishtamberdy and Kichi-Chaarat mines has been further compounded by a lack of cooperation with the Ministry of Emergency Situations in cases of emergencies and accidents. Previously, the companies paid a salary to the officers of the Ministry and, in case of accidents, an official rescue team would help, but this cooperation has stopped.

These issues mean that workers take responsibility for their own safety, for example, by buying special uniforms and equipment themselves when the company’s equipment was broken or worn (e.g., including small items such as flashlights). Doing so, however, has unfortunately failed to avert mine accidents. According to interviewees, five persons died in the Ishtamberdy mine in 2022. This included two employees who died of carbon monoxide gas poisoning (and another ten were injured) as the mine did not provide gas masks and mine tunnels were not sealed properly.Footnote 51

Another problem is that all instructions for the machinery is in Chinese. Most local workers cannot read Chinese and this problem is heightened during times of emergency, which are often time critical. The language gap is particularly pronounced by the fact that the Chinese companies do not provide training in the local language.

3.8 Complying with Salary Laws

The latest information on the average salary by sector shows that the mining sector has among the highest-paying jobs, together with manufacturing, information and communication, and the finance and insurance sectors. On average, employees receive about US$400 per month, whereas the average salary, across the largest sectors (agriculture, construction, trade, and public sector), is about US$150–200 per month.Footnote 52 However, in Ishtamberdy, the salary of workers is around US$230–250, which is significantly lower than the sector norm. In addition, in violation of local law, night shifts and extra hours are not paid.

According to the Labor Code of Kyrgyzstan, the mine workers’ salary should have the following bonuses: high-altitude coefficient (30%), level of danger (30%), and night shifts (50%). Most mines are located above 3,000 m; therefore, mine workers should get at least the high-altitude coefficient. However, such bonuses are rarely granted. The representative of Kyrgyz Geology Trade Union stated:

When we negotiate with Chinese companies, they say that they do not have the concept of high-altitude coefficient for the salary. They have a fixed salary of 30,000 som.Footnote 53 It includes night shift, high-altitude coefficient, and harmfulness. They say they don’t have this in China.

We explain to them that all employers working in Kyrgyzstan, regardless of their form of [company] ownership, are subject to the Labor Code of the Kyrgyz Republic. That is, they comply with labor laws.

We have these problems, at the initial stage of interaction, when preparation work is already being carried out. Chinese investors involve lawyers and the lawyers also explain [the requirements] to them. This stage lasts six months or a year; almost all companies have this tendency. Chinese companies are not immediately ready to comply with local labor laws; they need to be explained, convinced, and proven that this must be done. […]

At the beginning, an employment contract is not concluded, only a salary is paid. When the process begins, trade unions are created and people begin to contact the labor inspectorate, [only then] problems are exposed.

And accordingly, [when] a dispute begins, we have several legal companies, Chinese consulting companies, and they explain their rights. The Chinese company leaders contact them, and it becomes clear that our demands are correct.

In summary, although mining salaries are among Kyrgyzstan’s highest, there is a sense of injustice among workers in Chinese-owned mines who argue they are not receiving their full entitlement. There is also a view that the process of educating and persuading Chinese investors to pay the full entitlement is long and painstaking.

3.9 Working Conditions

According to the workday calendar approved by the Kyrgyz government,Footnote 54 mine workers should work a maximum of thirty-six hours per week. In reality, however, they often work up to fifteen additional hours, which goes unpaid. Sick leave is paid in Kichi-Chaarat, but in Ishtamberdy it depends on the negotiating and persuasive skills of the applicant. If successful, they can receive compensation.

Accommodation and food also need improvement. Accommodation in Ishtamberdy mainly consists of shipping containers, six to eight people in one room, and accommodation conditions for Kyrgyz workers are definitely poorer than those provided for Chinese workers.

3.10 Grievances

Since 2010, when Chinese mining companies first began active mineral exploration in Kyrgyzstan, there have been numerous social and environmental conflicts due to mining operations. Participants from the surrounding villages have blocked roads, attacked mine sites, and engaged in other forms of protest. Because of corruption and instability within the political system in Kyrgyzstan, citizens often cannot resort to official channels for redress. Rather, historically, grassroots movements, including demonstrations, have been a more effective means of expressing civil disobedience and protecting social and economic rights. This is particularly so in the context of the mining sector.Footnote 55

Ishtamberdy and Kichi-Chaarat have both seen a number of conflicts related to environmental problems, as expressions of disagreement by the local people to the mining process. This kind of demonstration serves also as a platform where local communities not only expressed grievances but also, and perhaps demonstrating a peculiarity of the Kyrgyz mining industry, expressed their willingness and ability to resume work in the hope that their protests would result in obtaining employment.

3.11 Mine Protests

Since the opening of the Ishtamberdy mine in 2011, at least three instances of service disruption have been documented. First, in 2012, workers called a strike. This led to a 30% pay rise (but less than the 50% being sought).Footnote 56 Later, in 2018, nearly 400 workers were dismissed for refusing to accept contracts with lower pay (which was driven by Ishtamberdy mine’s poor financial performance). The vice president of Full Gold Mining elaborated:

Our company has been suffering losses since it began to work. We invested US$200 million in the deposit. At least 958 million som have been spent on the payment of wages. Workers are very expensive, so we decided to change the terms of the contract. We ask for help to survive a difficult period together. The funds invested have not yet paid off. In order not to become bankrupt, we are forced to take such steps.Footnote 57

The mass dismissal of workers led to villagers from Kizil-Tokoi and Terek-Sair forming a protest and, in turn, a suspension of operations at Ishtamberdy.Footnote 58

In 2020, protestors alleging electoral fraud in the 4 October presidential elections also stormed the premises of Full Gold Mining.Footnote 59 This occurred during a period of civil unrest across Kyrgyzstan in which the Kyrgyz White House and Supreme Court were also occupied. The precise motivations for storming the premises are unclear and may have been driven by frustrations beyond the mine itself: government corruption, socioeconomic inequalities, and the presence of foreign-controlled companies in Kyrgyzstan.Footnote 60

Although there are fewer documented instances of unrest at the Kichi-Chaarat mine, the mine has not been insulated against similar incidents and in 2020 “tightened security at its mine, anticipating riots by the locals.”Footnote 61

3.12 Inaccessible Justice

Resolving large-scale labor disputes has typically been achieved through negotiations between companies, employees, local and national authorities, and labor unions. Both the government and the companies are interested in not publicizing the disputes and try to resolve conflicts internally.

As for labor disputes initiated by individual workers, litigants officially have recourse to the courts and there are regular court cases. However, most of the local employees have little legal knowledge and thus do not seek recourse in courts. If they are fired or face any labor rights violation, they usually address the local municipality or district level authorities, or simply keep believing the promises of Chinese company representatives.

These issues are further compounded by a number of factors, one of which is that information on court cases is hard to find in the state register,Footnote 62 unless you know the full information on the case. This difficulty renders jurisprudence inaccessible and imposes a constraint on litigants and their legal advisors, thereby placing them on the back foot vis-à-vis businesses such as the Ishtamberdy and Kichi-Chaarat mine owners who have their own in-house counsels.

In the meantime, according to Kyrgyz law, a person should address the court with a complaint regarding unfair termination within two months of being fired. The procedure for addressing the complaint is also quite complicated as employees need to have a conclusion from labor inspection. This requirement creates a significant time delay for filing that in the past has impeded a number of suits. For example, interviewees reported losing their age discrimination case(s) because the case(s) expired due to such time delays.

3.13 The Role of Government Agencies

Government agencies and local authorities tend to have insufficient experience and capacity to deal with enforcement issues. For example, corruption is a deep-seated problem, and while some argue that corrupt practices can actually help address certain issues, in general, corruption exacerbates systemic problems. Specific to Chinese investors, local authorities and high-level authorities (e.g., deputies of the Kyrgyz Parliament) have been known to form affiliated companies that win subcontract tenders from the Chinese. Consequently, they may exhibit a protectionist attitude toward Chinese investors even if those investors are violating local environmental and labor rules. This problem creates resentment among local residents who have groups, including on social media, where they share information on, for example, corrupt actions by local government and the nontransparent practices of Chinese investors. These resentments likely resulted in the 2020 election protests.

Local authorities often do not have sufficient human resources to work effectively with Chinese and other foreign investors. In the Chatkal district where several mines, including the Kichi-Chaarat mine, are located, there is only one official responsible for communicating with all mining companies and who seems not to have any background in mining.

In cases of conflict, local employees and communities are known for mobilizing online social media platforms, as well as using demonstrations, to put pressure on national decision makers. The authorities then form national commissions to address the issues, but little seems to be achieved. The president may also be called upon to intervene directly in the matter – even when it may not be entirely appropriate to do so. The effectiveness of such commissions and presidential interventions is therefore questionable.

Chinese companies, in turn, have poor communication strategies and often fail to keep local communities informed. They seem to struggle to understand the value of such communication. Additionally, they are also dependent on organized crime groups that come to “protect” their business. These crime groups work as security officers to watch over local employees. In times of political unrest or acting on information from local employees inside, there have been cases of robbery and theft of gold from the factory. Understandably, the involvement of crime groups against local workers is perceived negatively and there are attempts of local communities to counter this, by organizing their own groups.

Representatives of local authorities mention that Chinese companies are failing to implement communication strategies effectively and engage with the local population. The companies rarely organize public hearings and, as a result, local communities have little interaction with Chinese companies beyond “stealing gold.” In parallel, the Chinese companies also have no trust in local communities and authorities. They perceive people approaching their companies as those who came to rob, steal, or ask for funding for charitable causes, develop a business proposition, or ask for resources to fix a public utility in the village. The representatives of Chinese companies who are hired to communicate with the local population often do not have enough experience of working with the public. As a result, they fail to represent the companies positively or to highlight the benefits mines can bring to a region. For example, gold mining can contribute up to 50% of a municipality budget and often supports and improves local infrastructure and facilities.

Fourth, access to company reports is also an issue. Non-Chinese companies publish annual Environmental Impact Assessments (EIAs) and regular reports on their socioeconomic contributions to the local communities on their websites. In contrast, Chinese companies do not even have websites. The results of the interviews show that Chinese companies do support local projects and funding, but there is no strategy or process to make this information available; information is mainly distributed during the local budget hearings once a year.

The labor inspection is implemented by the State Inspection of Labor and Trade Union. The Trade Union has two inspections: a legal inspection and an inspection of safety measures. Since January 2022, the Kyrgyz government abolished inspections of business by the state committee for the support and improving of the investment climate. The Trade Union public inspectors have a right to access enterprises whenever they seek access, and they can exercise both planned and non-planned inspections. Currently they conduct one inspection of Chinese companies annually. Usually, non-planned inspections are carried out when employees report on violations of labor rights – but this is rare in any case.

4 Conclusion

China has significant investment not just in gold mining in Kyrgyzstan but in extractives industries throughout Central Asia. Hence, this case study spotlights issues of broad relevance. Our interviews suggest that Chinese mining companies demonstrate an initial unwillingness to follow local labor legislation at the beginning of their investment projects, and only the efforts of local authorities and trade unions ultimately persuade them to comply, at least in part. Hence, there is a learning curve that Chinese companies undergo.

Owing to language and cultural barriers, Chinese companies delegate the recruitment process to local subcontracting companies and the Human Resource departments consisting of mainly local employees and local authorities. However, this approach opens a way for personal connections and clan-based ties to play a role in hiring. As a result, people with no proper experience are recruited. Such trends can endanger operational processes and put technical safety standards at risk.

Violations of labor rights by Chinese mining companies are prevalent throughout Kyrgyzstan and, in particular, wherever informal employment is prevalent and wherever this can be used to remove undesired workers. Fixed-term contracts are common not only in the mining sector but also in other business sectors. Nevertheless, compared to other mines, Chinese companies pay less attention to occupational safety and providing necessary technical equipment.

Owing to their lack of expertise in communication and public relations, Chinese companies often become the targets of social conflict. In those cases where companies do have a communication strategy, it often depends on employees who lack experience. For example, company websites or social media platforms are not widely used so information is hard to come by. The companies also rarely participate in local meetings or explain how they are contributing to the local economy and fail to take the opportunity of highlighting their positive contributions such as improving local infrastructure. In contrast, some non-Chinese foreign companies are adept at using not only their own media sources but also TV channels and news websites to tell their story and emphasize the value they bring to the country. Unfortunately, when Chinese companies do appear in the media, it is usually in the context of social conflict.

5 Discussion Questions and Comments

5.1 For Law School Audiences

1. The Kyrgyz Labor Code is one source of problems for insufficient protection of workers. What legislative changes would you make to the Labor Code? How would you balance protecting workers’ rights with maintaining a competitive commercial environment for foreign investors?

2. Assume the role of a public interest lawyer, instructed by the workers. They have informed you that they wish to pursue a mixture of grassroots actions and alternative dispute resolution methods to secure their rights. Propose what actions (legal and otherwise) the workers should take against (a) the foreign investors; (b) the local government; (c) the national government; and (d) local communities.

3. Assume the role of a general counsel at either the Ishtamberdy or Kichi-Chaarat mine. How might you redraft the company’s policies as pertaining to labor relations and management?

5.2 For Policy School Audiences

1. What kinds of policy interventions could Kyrgyz authorities make at the local or national levels to avoid the types of disputes that have occurred at the Ishtamberdy and Kichi-Chaarat mines from developing in the first place?

2. Given that such disputes have in fact arisen, what options are available to Kyrgyz authorities to mitigate the conflicts? Which factors would the authorities consider in trying to resolve the conflicts?

5.3 For Business School Audiences

1. Imagine you are the general manager at either the Ishtamberdy or Kichi-Chaarat mines. What mine-wide measures would you implement that balance the following priorities: (a) increased compliance with local law; (b) enhanced communication and relations between local and foreign employees; and (c) profitability?

2. Language, culture, and customs are perennial issues that create wedges between Chinese mining companies and local Kyrgyz labor. How should Chinese companies refine their approaches to gaining greater proficiency over these issues and what kinds of intermediaries would be helpful to that effect?